The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) student’s no-nonsense guide to developing your research question (RQ)

Written by Elena Gil-Rodriguez

Planning and designing your interpretative phenomenological analysis (ipa), aka: how do i come up with my interpretative phenomenological analysis (ipa) and/or qualitative research question.

Updated February 2022

I am frequently asked for advice on how to come up with a suitable research question (RQ) for a qualitative study, and more specifically, an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). As a frequently posed question, I thought some (hopefully) helpful guidance might assist you.

Truth bomb: your research question may change as you conduct your research

One point that is important to make here is that while RQs are important as they guide the design and the execution of a qualitative research study, they do tend to evolve, and may change or be updated as you progress through your research . They could therefore be described as provisional .

With this in mind, try not to get too hung up on producing the perfect RQ for your IPA study, and be mindful to hold it lightly as it could alter (or even transform!) before you get to the end of the research process (mine certainly did for my professional doctorate).

How to start formulating your IPA research question

Firstly, it’s a no-brainer, but worth mentioning that your topic area and RQ are obviously going to be intimately connected, with the topic area being much broader than the RQ you develop.

My first suggestion in the process of developing your RQ is therefore to start broad and map out your topic area to the best of your ability. See your free IPA Study Survival Guide with its Road Map and Checklist for handy tips and guidance on how to go about this process.

Once you have an idea of the ‘terrain’ of your topic area and have mapped out what has already been done, what we already know in the field in question, and where any gaps may be, you can start to narrow down . Your goal is to develop some broader aims and objectives for your research project (i.e., what are you looking to achieve with this research study?) From these, you will be able to pin down your RQ itself.

Narrowing down to develop your IPA research question

Asking yourself the following series of questions may help with this:.

Question one:

What do you want to know?

Purpose : to identify your point of interest. For example, women and coaching practices.

Start to narrow down or curtail the scope:

Question two:

Which/what features are you interested in knowing about?

E.g., are you interested in the process of coaching women or what it feels like/the experience of being coached or doing the coaching? The language used in the process of coaching?

TIP : look at the extant literature from your mapping exercise. What is already out there and what has already been done? Where are the gaps? This will inform your approach/aims and objectives and therefore RQ. Check the suggestions for further research in the papers you have reviewed. You are looking to build upon, extend, add to, or challenge what has already been done.

Narrow down further:

Question three:

What do you want to be able to say at the end of your research? Do you want to be able to say something about a single group or phenomenon? Do you want to identify a process in a dyad or another small group such as a family/team? Do you want to identify and/or understand the features of different experiences?

Returning to our coaching example, perhaps you want to say something about the experience of different coaching approaches or contexts (e.g., career coaching or other coaching)? Understanding more about this will help you outline your aims and objectives and from these, pin down your RQ.

Question four:

What do you want to do with the findings? For example, do you want to inform policy, create a model, generate a theory, develop a tool, or simply provide a rich and thick description of something as a starting point if the topic area has little previous investigation? You may want to continue beyond this particular study to start building a corpus of research, in which case, this study may be the first step or building block in that endeavour. What do your stakeholders require? For example, they may want larger-scale findings to support some element of transferability of the knowledge created.

Question five:

How are RQs employing your methodology usually posed? What is the language and tone that is typically utilised? Scour the extant literature for examples from relevant research that employs your chosen methodology to guide you.

TIP : qualitative RQs are exploratory in nature and in IPA they tend to focus on the meaning of experiences/phenomena and how people make meaning of those experiences/phenomena. Thus, qualitative RQs tend to ask HOW (and/or WHAT) rather than WHY and you are likely to find that the term ‘experience’ may well show up in your IPA RQ!

Final thoughts

It can be a struggle to come up with your RQ (it most definitely was for me!) However, don’t give up, and remember that research is basically a series of compromises – there is no such thing as the perfect RQ or perfect research project!

If you work down from your map of the topic area to the broader aims and objectives of your research study, your RQ should emerge from that process.

However , remember to consider feasibility :

Be aware that you are likely to be overambitious at the beginning: usually, students come with too big of a question that could be more than one study or even a PhD. They often have to scale back for the purposes of their project and choose what is really interesting to them and feasible/do-able.

If you suspect that your RQ is too big, ask yourself what you could do now that you are most excited about, and that could provide a stepping stone for the next move forward in answering your big question.

Summary of top tips for coming up with a research question

- Read relevant research in the topic area and check suggestions for further research and how the study’s aims, objectives and RQs have been posed

- Start broad and narrow down using the questions ideas and suggestions in this article

- If you have come up with too big of a question, consult with your supervisor and/or peers to break it down into smaller, more manageable, and do-able project ideas and RQs

- Remember that your RQ (and therefore study itself) does need to ignite and excite you if it is to sustain your interest over what could be quite a lengthy research journey

Recommended literature to read around developing your qualitative and/or IPA RQ:

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Planning and designing qualitative research. In V. Braun & V. Clarke, Successful qualitative research (pp. 42-74). London: Sage.

Kinmond, K. (2012). Coming up with a research question. In C. Sullivan, S. Gibson, & S. Riley (Eds.), Doing your qualitative psychology project (pp. 23-36). London: Sage

NOTE: While this is an undergraduate text, this chapter is freely available on the internet and is a very well-constructed introduction to writing qualitative RQs – just Google Scholar it

Larkin, M. (2015). Choosing your approach. In J.A. Smith (Ed.) Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 249-256). London: Sage

Smith, J.A., Larkin, M., & Flowers, P. (2009). Planning an IPA research study. In J.A. Smith, M. Larkin, & P. Flowers, Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research (pp.40-55). London: Sage

And of course, in the 2022 Second Edition , head immediately to pages 41 to 43 in Chapter Three ‘Planning an IPA Research Study’

Willig, C. (2013). Qualitative research design and data collection. In C. Willig, Introducing qualitative research in psychology , (pp. 23-38). Berks, UK: OU Press

Recommended journal article :

Agee, J. (2009). Developing qualitative research questions: a reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22 (4), 431-447.

NOTE: relevant journal articles were quite thin on the ground (interesting, huh?), but this one is of good quality and presents useful examples, although more from social sciences disciplines than specifically psychology . Plus it is open access from Google Scholar – bonus!

Finishing up – please do reach out!

This topic for this article was bought to you at the request of a mailing list member who is approaching this step of their research journey.

I would love to be as responsive as I can to your real-time research dilemmas, so please do join the mailing list and reply to your welcome email or use the contact form to send me a message to let me know of any specific areas you would like me to cover, and I will do my best to help out!

Until next time!

To your research success, Elena

Copyright © 2020-24 Dr Elena Gil-Rodriguez

These works are protected by copyright laws and treaties around the world. Dr Elena GR grants to you a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, revocable licence to view these works, to copy and store these works and to print pages of these works for your own personal and non-commercial use. You may not reproduce in any format any part of the works without my prior written consent. Distributing this material in any form without permission violates my rights – please respect them.

The information contained in this article or any other content on this website is provided for information and guidance purposes only and is based on Dr Elena GR’s experience in teaching, conducting, and supervising IPA research projects. All such content is intended for information and guidance purposes only and is not meant to replace or supersede your supervisory advice/guidance or institutional and programme requirements, and are not intended to be the sole source of information or guidance upon which you rely for your research study. You must obtain supervisory and institutional advice before taking, or refraining from, any action on the basis of my guidance and/or content and materials. Dr Gil-Rodriguez disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed upon any of the contents of my website or associated content/materials. Finally, please note that the use of my content/materials does not guarantee any particular grade for your work.

You may also like…

Sample size for your Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research study: small is beautiful

Learn more about sample size for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research study

The ultimate guide to planning your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research study

Aka: How on earth will I manage the enormous task of completing my IPA research project? As you have probably...

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_221177275_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

- Basics of Research Process

- Methodology

Phenomenological Research: Full Guide, Design and Questions

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

Phenomenological research is a qualitative research approach that focuses on exploring the subjective experiences and perspectives of individuals. Phenomenology aims to understand how people make meaning of their experiences and how they interpret the world around them.

Phenomenological research typically involves in-depth interviews or focus group discussions with individuals who have experienced a particular phenomenon or event. The data collected through these interviews or discussions are analyzed using thematic analysis.

Today, we will learn how a scholar can successfully conduct a phenomenological study and draw inferences based on individual's experiences. This information would be especially useful for those who conduct qualitative research . Well then, let’s dive into this together!

What Is Phenomenological Research: Definition

Let’s define phenomenological research notion. It is an approach that analyzes common experiences within a selected group. With it, scholars use live evidence provided by actual witnesses. It is a widespread and old approach to collecting data on certain phenomenon. People with first-hand experience provide researchers with necessary data. This way the most up-to-date and, therefore, least distorted information can be received. On the other hand, witnesses can be biased in their opinions. This, together with their lack of understanding about subject, can influence your study. This is why it is important to validate your results. If you aren’t sure how to validate the outcomes, feel free to contact our dissertation writers . They have proven experience in conducting different research studies, including phenomenology.

Phenomenological Research Methodology

You should use phenomenological research methods carefully, when writing an academic paper. Aside from chance of running into bias, you risk misplacing your results if you don't know what you're doing. Luckily, we're here to provide thesis help and explain what steps you should take if you want your work to be flawless!

- Form a target group. It is typically 10 to 20 people who have witnessed a certain event or process. They may have an inside knowledge of it.

- Systematically observe participants of this group. Take necessary notes.

- Conduct interviews, conversation or workshops with them. Ask them questions about the subject like ‘what was your experience with it?’, ‘what did it mean?’, ‘what did you feel about it?’, etc.

- Analyze the results to achieve understanding of the subject’s impact on the group. This should include measures to counter biases and preconceived assumptions about the subject.

Phenomenological Research: Pros and Cons

Phenomenological research has plenty of advantages. After all, when writing a paper, you can benefit from collecting information from live participants. So, here are some of the cons:

- This method brings unique insights and perspectives on a subject. It may help seeing it from an unexpected side.

- It also helps to form deeper understanding about a subject or event in question. Many details can be uncovered, which would not be obvious otherwise.

- It provides undistorted data first-hand.

But, of course, you can't omit some disadvantages of phenomenological research. Bias is obviously one of them, but they don't stop with it. Observe:

- Sometimes participants may find it hard to convey their experience correctly. This happens due to various factors, like language barriers.

- Organizing data and conducting analysis can be very time consuming.

- You can generalize the resulting data easily.

- Preparing a proper presentation of the results may be challenging.

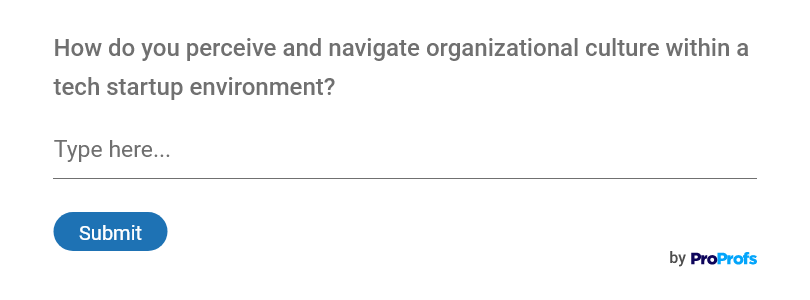

Phenomenological Research: Questions With Examples

It is important to know what phenomenological research questions can be used for certain papers. Remember, that you should use a qualitative approach here. Use open-ended questions each time you talk with a participant. This way the participant could give you much more information than just ‘yes’ or ‘know’. Here are a few real examples of phenomenological research questions that have been used in academic works by term paper writers .

Phenomenological Research Questions: Examples

When you're stuck with your work, you might need some examples of phenomenological research questions. They focus on retrieving as much data as possible about a certain phenomenon. Participants are encouraged to share their experiences, feelings and emotions. This way scholars could get a deeper and more detailed view of a subject.

- What was it like, when the X event occurred?

- What were you thinking about when you first saw X?

- Can you tell me an example of encountering X?

- What could you associate X with?

- What was the X’s impact on your life/your family/your health etc.?

Phenomenological Research Examples

Do you need some real examples of phenomenological research? We'll be glad to provide them here, so you could better understand the information given above. Please note that good research topics should highlight the problem. It must also indicate the way you will collect and process data during analysis.

- Understanding the role of a teacher's personality and ability to lead by example play in the overall progress of their class. A study conducted in 6 private and public high schools of Newtown.

- Perspectives of aromatherapy in treating personality disorders among middle-aged residents of the city. A mixed methods study conducted among 3 independent focus groups in Germany, France and the UK.

- View and understanding of athletic activities' roles by college students. Their impact on overall academic success. Several focus groups have been selected for this study. They underwent both online conduct surveys and offline workshops to voice their opinions on the subject.

Phenomenological Research: Final Thoughts

Phenomenological qualitative research is crucial if you must collect data from live participants. In this article, we have examined the concept of this approach. Moreover, we explained how you can collect your data. Hopefully, this will provide you with a broader perspective about phenomenological research!

Or do tight deadlines give you a headache? Check out our paper writing services ! We’ve got a team of skilled authors with expertise in various academic fields. Our papers are well written, proofread and always delivered on time!

Joe Eckel is an expert on Dissertations writing. He makes sure that each student gets precious insights on composing A-grade academic writing.

You may also like

Frequently Asked Questions About Phenomenological Qualitative Research

1. what are the 4 various types of experiences in phenomenology.

Phenomenology studies the structure of various types of experience. It attempts to view a subject from many different angles. A good phenomenological research requires focusing on different ways the information can be retrieved from respondents. These can be: perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition. With them explained, a scholar can retrieve objective information, impressions, associations and assumptions about the subject.

3. What is the purpose of phenomenological research design?

Main goal of the phenomenological approach is highlighting the specific traits of a subject. This helps to identify phenomena through the perceptions of live participants. Phenomenological research design helps to formulate research statements. Questions must be asked so that the most informative replies could be received.

4. What is phenomenological research study?

A phenomenological research study explores what respondents have actually witnessed. It focuses on their unique experience of a subject in order to retrieve the most valuable and least distorted information about it. The study must include open-ended questions, target focus groups who will provide answers, and the tools to analyze the results.

2. What is hermeneutic phenomenology research?

Hermeneutic phenomenology research is a method often used in qualitative research in Education and other Human Sciences. It inspects deeper layers of respondents’ experiences by analyzing their interpretations and their level of comprehension of actual events, processes or objects. By viewing a person’s reply from different perspectives, researchers try to understand what is hidden beneath that.

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Locating Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks This link opens in a new window

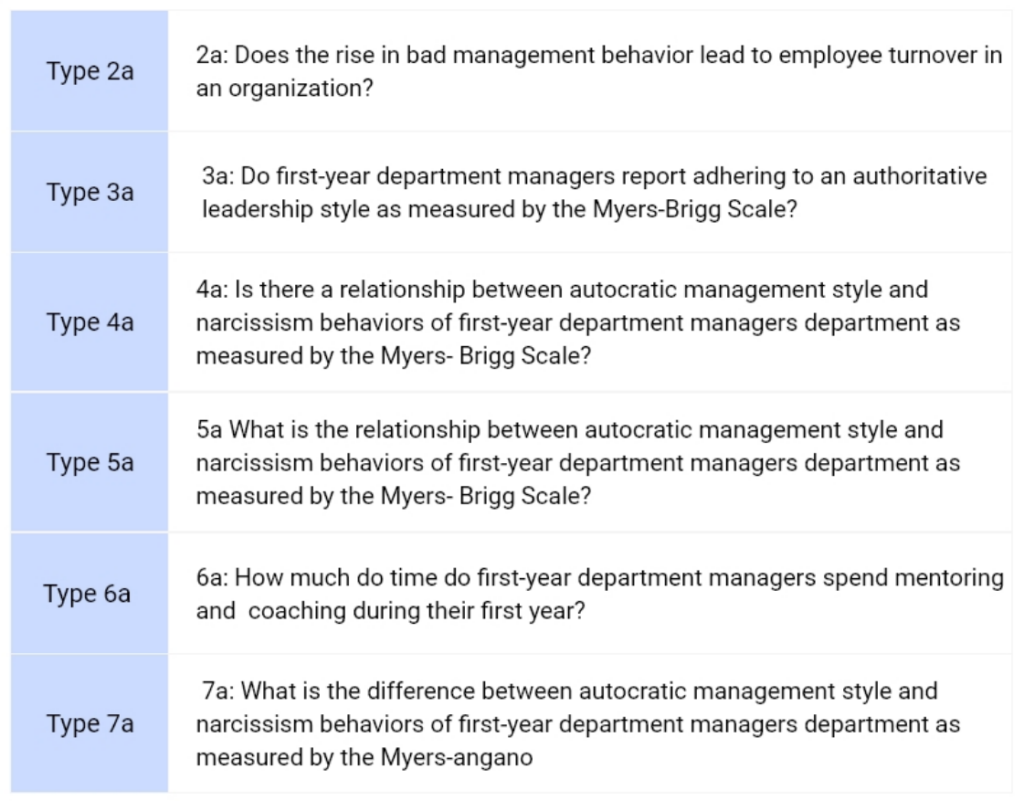

- Quantitative Research Questions

Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

What’s in a Qualitative Research Question?

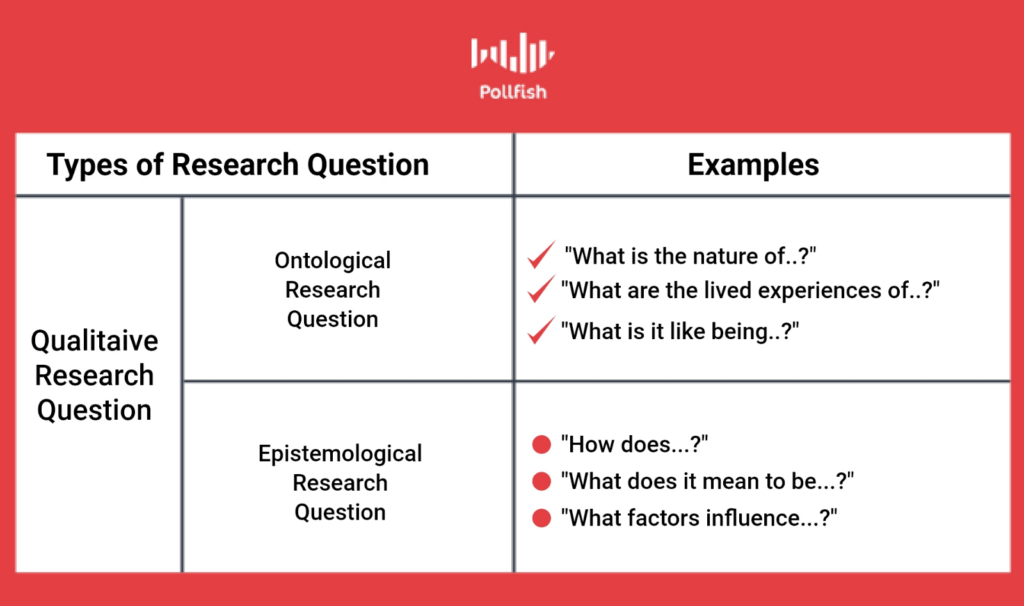

Qualitative research questions are driven by the need for the study. Ideally, research questions are formulated as a result of the problem and purpose, which leads to the identification of the methodology. When a qualitative methodology is chosen, research questions should be exploratory and focused on the actual phenomenon under study.

From the Dissertation Center, Chapter 1: Research Question Overview , there are several considerations when forming a qualitative research question. Qualitative research questions should

Below is an example of a qualitative phenomenological design. Note the use of the term “lived experience” in the central research question. This aligns with phenomenological design.

RQ1: “ What are the lived experiences of followers of mid-level managers in the financial services sector regarding their well-being on the job?”

If the researcher wants to focus on aspects of the theory used to support the study or dive deeper into aspects of the central RQ, sub-questions might be used. The following sub-questions could be formulated to seek further insight:

RQ1a. “How do followers perceive the quality and adequacy of the leader-follower exchanges between themselves and their novice leaders?”

RQ1b. “Under what conditions do leader-member exchanges affect a follower’s own level of well-being?”

Qualitative research questions also display the desire to explore or describe phenomena. Qualitative research seeks the lived experience, the personal experiences, the understandings, the meanings, and the stories associated with the concepts present in our studies.

We want to ensure our research questions are answerable and that we are not making assumptions about our sample. View the questions below:

How do healthcare providers perceive income inequality when providing care to poor patients?

In Example A, we see that there is no specificity of location or geographic areas. This could lead to findings that are varied, and the researcher may not find a clear pattern. Additionally, the question implies the focus is on “income inequality” when the actual focus is on the provision of care. The term “poor patients” can also be offensive, and most providers will not want to seem insensitive and may perceive income inequality as a challenge (of course!).

How do primary care nurses in outreach clinics describe providing quality care to residents of low-income urban neighborhoods?

In Example B, we see that there is greater specificity in the type of care provider. There is also a shift in language so that the focus is on how the individuals describe what they think about, experience, and navigate providing quality care.

Other Qualitative Research Question Examples

Vague : What are the strategies used by healthcare personnel to assist injured patients?

Try this : What is the experience of emergency room personnel in treating patients with a self-inflicted household injury?

The first question is general and vague. While in the same topic area, the second question is more precise and gives the reader a specific target population and a focus on the phenomenon they would have experienced. This question could be in line with a phenomenological study as we are seeking their experience or a case study as the ER personnel are a bounded entity.

Unclear : How do students experience progressing to college?

Try this : How do first-generation community members describe the aspects of their culture that promote aspiration to postsecondary education?

The first question does not have a focus on what progress is or what students are the focus. The second question provides a specific target population and provides the description to be provided by the participants. This question could be in line with a descriptive study.

- << Previous: Quantitative Research Questions

- Next: Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data >>

- Last Updated: Jul 9, 2024 3:24 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

Phenomenology In Qualitative Research

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is phenomenology?

Phenomenology in qualitative research is characterized by a focus on understanding the meaning of lived experience from the perspective of the individual.

Instead of testing hypotheses or seeking to generalize findings to a larger population, phenomenological research aims to illuminate the specific and to challenge structural or normative assumptions by revealing the subjective experiences and perceptions of individuals.

This approach is particularly valuable for gaining insights into people’s motivations and actions, and for cutting through taken-for-granted assumptions and conventional wisdom.

Aim of Phenomenological Research

The aim of phenomenological research is to arrive at phenomenal understandings and insights into the meaning of lived experience.

These insights should be “impressively unique” and “primordially meaningful”, illuminating the specific experience being studied.

Phenomenological research attempts to uncover the meaning in lived experiences that are often overlooked in daily life. In other words, phenomenology asks the basic question: “What is this (primal) experience like?

To do this, phenomenological research examines experience as it appears to consciousness, seeking to avoid any preconceptions or assumptions.

Rather than simply describing what participants say, phenomenological research seeks to go deeper, to uncover implicit meanings and reveal the participant’s lifeworld.

This is not a matter of making generalized statements, but of understanding the experience from the individual’s perspective.

The aim is not to provide causal explanations or to theorize about the experience, but to “restore to each experience the ontological cipher which marks it internally.

Characteristics of Phenomenology

Phenomenology is best understood as a radical, anti-traditional style of philosophising that emphasizes describing phenomena as they appear to consciousness. It is not a set of dogmas or a system, but rather a practice of doing philosophy.

Here are some key characteristics of phenomenology:

- Focus on Experience: Phenomenology is concerned with the “phenomena,” which refers to anything that appears in the way that it appears to consciousness. This includes experiences, perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and meanings.

- First-Person Perspective: Phenomenology emphasizes the importance of the first-person, subjective experience. It seeks to understand the world as it is lived and experienced by individuals.

- Intentionality: A central concept in phenomenology is intentionality, which refers to the directedness of consciousness toward an object. This means that consciousness is always consciousness of something, and this directedness shapes how we experience the world.

- Bracketing (Epoche): Phenomenological research often involves “bracketing” or setting aside preconceived notions and assumptions about the world. This allows researchers to approach phenomena with an open mind and focus on how they appear in experience.

- Descriptive Emphasis: Phenomenology prioritizes description over explanation or interpretation. The aim is to provide a rich and nuanced account of experience as it is lived, without imposing theoretical frameworks or seeking to explain it in terms of external factors.

- Search for Essences: Phenomenology is interested in uncovering the essential structures and meanings of experience. This involves going beyond the particularities of individual experiences to grasp the shared features that make them what they are.

- Holistic Approach: Phenomenology seeks to understand experience in a holistic way , recognizing the interconnectedness of mind, body, and world. It rejects reductionist approaches that attempt to explain experience solely in terms of its parts.

- Use of Examples: Phenomenological researchers often use concrete examples to illustrate and explore the meaning of experience. These examples can be drawn from personal narratives, literature, or other sources that provide rich descriptions of lived experience.

Is phenomenology an epistemology or ontology?

Phenomenology straddles or undermines the traditional distinction between epistemology and ontology. Traditionally, epistemology is understood as the study of how we come to understand and have knowledge of the world, while ontology is the study of the nature of reality itself.

- Phenomenology investigates both how we understand the world and the nature of reality through its focus on phenomena . By examining how things appear to us, phenomenology analyzes our way of experiencing and understanding the world, simultaneously addressing questions about the objects themselves and their modes of appearance.

- Heidegger suggests that ontology is only possible through phenomenology . According to this view, analyzing our being-in-the-world is key to understanding the nature of reality itself.

Instead of separating subject and object, or the knower and the known, phenomenology highlights their interrelation, arguing that the mind is essentially open to the world, and reality is essentially capable of manifesting itself to us.

Exploring Phenomenology: Three Key Perspectives

1. husserl’s transcendental phenomenology.

Edmund Husserl viewed phenomenology as the “science of the essence of consciousness”, emphasizing the intentional structure of conscious acts. Central for phenomenological psychology was phenomenological philosopher Husserl’s understanding of “intentionality,” the idea that whenever we are conscious we are conscious of something, making the job of the researcher to better understand people’s experiences of things “in their appearing” (Langdridge, 2007, p. 13).

- Intentionality: This key concept describes consciousness’s directedness towards objects—our experiences are always about something. This “aboutness” isn’t limited to physical objects and encompasses mental acts like remembering, imagining, or even fearing.

- Essence over Existence: Husserl’s phenomenology focuses on uncovering the invariant structures of consciousness, aiming to reveal the essence of experiences like perception, thought, or emotion. It is not concerned with whether the object of an experience actually exists in the world.

- Transcendental Reduction: To grasp these essences, Husserl introduces the “epoché,” a methodological tool to bracket our natural attitude towards the world. This doesn’t mean denying the world’s existence; it’s about shifting focus from the objects themselves to how they appear in our consciousness.

- Example: When perceiving a table, we experience it through different profiles or perspectives. We can’t see all sides simultaneously, yet we grasp the table as a unified object. Transcendental phenomenology investigates the structures of consciousness that enable this constitution of objects from a multitude of appearances.

2. Heidegger’s Hermeneutical Phenomenology:

Martin Heidegger, while influenced by Husserl, diverged by emphasizing the importance of hermeneutics—the art of interpretation—in phenomenological inquiry.

- Being-in-the-World: Unlike Husserl’s focus on pure consciousness, Heidegger grounds his phenomenology in the concrete existence of Dasein—a term he uses to describe human existence’s inherent being-in-the-world.

- Facticity and Historicity: Heidegger recognizes that our understanding of the world is shaped by our historical and cultural contexts. We don’t encounter the world as a neutral observer, but through a lens of pre-existing interpretations and practices.

- Self-Concealing Nature of Phenomena: Heidegger contends that things don’t always reveal themselves fully. Our understanding is often clouded by biases, assumptions, or simply the inherent ambiguity of existence. Phenomenology, therefore, becomes a process of uncovering hidden meanings and questioning taken-for-granted assumptions.

- Example: Consider the act of using a hammer. For Heidegger, this isn’t just a neutral interaction with an object. It reveals a whole network of meanings related to our practical engagement with the world, our understanding of “for-the-sake-of-which” (building something), and our shared cultural practices.

3. Merleau-Ponty’s Idea of Perception

Maurice Merleau-Ponty further developed phenomenology by emphasizing the centrality of embodiment in our experience of the world.

- The Primacy of Perception: Merleau-Ponty challenges the traditional view of perception as a passive reception of sensory data. He argues that perception is an active and embodied engagement with the world.

- Body-Subject: Merleau-Ponty rejects the Cartesian mind-body dualism. For him, our body is not just an object in the world, but the very medium through which we experience and understand the world. The body is the “vehicle of being-in-the-world”.

- Perception as Foundation: Merleau-Ponty places perception at the heart of his phenomenology. He sees it as the foundation for all other cognitive activities, including thought, language, and intersubjectivity.

- Example: Consider the experience of touching a piece of velvet. It’s not simply that we receive tactile sensations. Our hand actively explores the fabric, and the perceived texture emerges from the dynamic interplay between our moving hand and the resistant surface. This experience can’t be reduced to purely mental representations or objective properties of the velvet; it arises from the embodied engagement between the perceiving subject and the world.

Data Collection in Phenomenological Research

Phenomenological research focuses on understanding lived experience, and therefore relies on qualitative data that can illuminate the subjective experiences of individuals.

Because phenomenology aims to examine experience on its own terms, it is wary of imposing pre-defined categories or structures on the data.

Many phenomenological philosophers and researchers avoid using the term “method” in favor of talking about the phenomenological “approach.”

Interviews are a common method for collecting data in phenomenological research.

Researchers typically use semi-structured or unstructured interviews, which prioritize open-ended questions and allow participants to describe their experiences in their own words.

These interviews aim to elicit detailed, concrete descriptions of specific experiences rather than abstract generalizations.

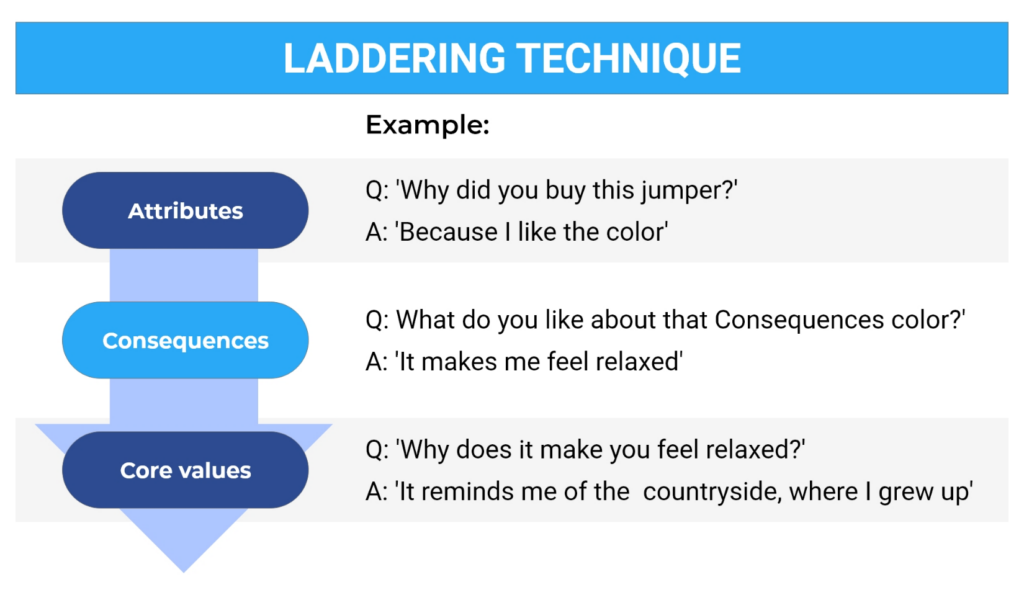

For instance, instead of asking “What does friendship mean to you?”, a researcher might ask: “Can you describe a time you felt particularly connected to a friend?”.

This shift from the abstract to the concrete helps researchers access the pre-reflective, lived experience of the phenomenon, revealing its texture and nuanc

Researchers may also use follow-up questions to clarify or gain a deeper understanding of participants’ responses.

Phenomenological interviews often explore experiences across multiple dimensions:

- Bodily sensations: The interviewer might ask: “What was happening in your body during that experience?” or “How did that situation make you feel physically?” These questions help uncover the embodied aspects of experience often overlooked in more cognitively-focused approaches.

- Thoughts and cognitions: Questions like “What sense did you make of that experience?” or “What thoughts went through your head?” help explore the cognitive interpretations participants make about their experiences.

- Emotional responses: The interviewer may ask: “What feelings were present during that time?” or “How did that situation make you feel emotionally?” Allowing participants to articulate their feelings without judgment or interpretation is crucial.

- Relational dynamics: When exploring interpersonal experiences, interviewers might ask: “What was it like to be with that person during that event?” or “How did your relationship with that person shape your experience?” Recognizing that experiences are not confined to the individual but are shaped by social and relational contexts is central to phenomenological inquiry

Beyond interviews, phenomenological research may draw upon a variety of other methods, including :

- Discussions: Open-ended discussions among participants who share an experience can shed light on commonalities and differences in how the phenomenon is lived.

- Participant observation: This method involves the researcher immersing themselves in a particular setting or community to gain firsthand experience of the phenomenon being studied.

- Analysis of personal texts: Participants’ diaries, letters, or other written accounts of their experiences can provide valuable insights into their subjective lifeworlds.

- Creative media: Researchers may use art, dance, literature, photography, or other creative media to encourage participants to express their experiences in non-verbal ways.

“Examples” are particularly important in phenomenological research. Rather than treating individual experiences as mere illustrations of general concepts, phenomenology understands examples as offering a unique window into the essence of a phenomenon.

Researchers carefully select and analyze examples to uncover and articulate the essential features of a lived experience.

Number of Participants in Phenomenological Studies

There is no prescribed number of participants required for a phenomenological study. Some researchers may choose to include a larger number of participants.

Phenomenological research emphasizes in-depth understanding of lived experiences rather than statistical generalization.

Therefore, sample size is less important than the richness and depth of the data obtained from the participants.

However, phenomenological studies that include more than a handful of participants risk being superficial and may miss the spirit of phenomenology.

Here are some examples of approaches to the number of participants in a phenomenological study:

- Three to six participants are considered to give sufficient variation.

- One participant can be used for a case study.

- Researchers can also use autobiographical reflection .

- Single-case studies can identify issues that illustrate discrepancies and system failures and illuminate or draw attention to “different” situations, but positive inferences are less easy to make without a small sample of participants.

- The strength of inference increases rapidly once factors start to recur with more than one participant .

Analyzing Data in Phenomenological Research

There are a variety of approaches to conducting phenomenological research and analyzing data.

The variety of approaches within phenomenological research can make it challenging for students to navigate, as there are no fixed rules or procedures

The specific analytic strategies used in a phenomenological study depend on the researcher’s chosen approach and the nature of the phenomenon being investigated.

Some researchers advocate for a more orthodox approach to phenomenological research that prioritizes rigorous description and aims to uncover essential structures of experience.

Descriptive Phenomenology

This approach, exemplified by the work of Giorgi and Wertz, emphasizes a rigorous, descriptive approach to capturing the essential structures of experience. It involves bracketing assumptions, focusing on pre-reflective experience, and seeking generalizable insight

For example, Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological method involves a multi-step procedure for analyzing descriptions of lived experience:

- Read the entire description to gain a holistic understanding.

- Divide the description into smaller units of meaning.

- Explicate the psychological significance of each meaning unit.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Other researchers, while still grounding their work in phenomenological philosophy, emphasize the importance of interpretation in understanding the unique, lived experience of individuals.

This approach, embraced by researchers like van Manen, prioritizes interpretation and dialogue in understanding the unique, lived experience of individuals.

For example, van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenology emphasizes the role of interpretation and reflection in uncovering meaning in lived experience.

It acknowledges the researcher’s role in shaping interpretations and emphasizes the transition from pre-reflective experience to conceptual understanding.

Van Manen suggests that researchers should explicate their own assumptions and biases in order to better understand how they might be shaping their interpretations of the data.

His approach also highlights the importance of understanding the transition from pre-reflective experience to conceptual understanding.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

If you are learning phenomenology, struggling with the material is expected.

Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) has become popular because it offers novice researchers a concrete structure, but its set structures may cause researchers to get caught up in method and lose the essence of the phenomenon being studied.

Developed by Jonathan Smith, IPA is a qualitative research method designed to gain an in-depth understanding of how individuals experience and make sense of specific situations.

It focuses on individual experiences and interpretations rather than aiming to uncover universal essences. IPA draws on a broader range of phenomenological thinkers than just Husserl.

It differs from descriptive phenomenology by incorporating an interpretive component, acknowledging that individuals are inherently engaged in meaning-making processes.

Critical Phenomenology

Critical phenomenology expands upon traditional phenomenology by examining the impact of social structures on lived experiences of power and oppression.

Critical phenomenology acknowledges that societal structures like capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy shape our lifeworlds and cannot be fully put aside

A key goal of critical phenomenology is to identify practical strategies for challenging oppressive structures and fostering liberatory ways of being in the world.

In psychology, phenomenology is linked with a critical realist epistemology; here, the real world exists, but it cannot be fully discovered because our experiences of it are always mediated (Shaw, 2019).

Regardless of the specific approach, several key principles should guide data analysis in phenomenological research:

- Focus on description : Phenomenological research aims to describe the lived experience of a phenomenon, rather than explain or theorize about it.

- Attend to pre-reflective experience : Researchers should strive to move beyond participants’ initial, surface-level descriptions to uncover the deeper, often implicit, meanings embedded in their experiences.

- Adopt a holistic perspective : A thorough analysis considers various aspects of experience, including embodiment, intersubjectivity, and the influence of social and cultural factors.

Reflexivity in Phenomenological Research

Phenomenological research acknowledges that researchers are active participants who bring their own perspectives and experiences to the research process.

It’s important for researchers to practice reflexivity by setting aside their own assumptions and previous knowledge in order to see the world anew through the lens of the participants’ lived experiences.

This process, known as bracketing , is an attempt to approach the research with “fresh eyes,” free from contaminating assumptions. It involves:

- Adopting a self-critical, reflexive meta-awareness: This means questioning “common sense” and taken-for-granted assumptions to reveal more about the nature of subjectivity.

- Abstaining from judgments about the truth or reality of objects in the world: For example, if a participant mentions seeing a ghost, the researcher focuses on what the ghost means to the person and how they experienced it subjectively rather than questioning the existence of ghosts.

- Recognizing the impossibility of completely removing subjectivity: Rather than trying to eliminate subjectivity, researchers should actively recognize its impact and engage with their own (inter-)subjectivity to better understand the other.

Bracketing is an ongoing process that requires mindfulness, curiosity, compassion, and a “genuinely unknowing stance” to remain open to new understandings and avoid imposing the researcher’s own biases on the data.

This is essential for rigorous phenomenological research, as subjectivity is central to the investigation.

However, different schools of thought within phenomenology emphasize different aspects of bracketing:

- Descriptive phenomenologists focus on reflexively setting aside previous understandings to prioritize the participant’s perspective.

- Hermeneutic phenomenologists strive for transparency in their interpretations.

- Critical phenomenology acknowledges that societal structures like capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy shape our lifeworlds and cannot be fully put aside.

By acknowledging the researcher’s role and emphasizing reflexivity, phenomenological research aims to ensure that findings remain grounded in the participants’ lived experiences, avoiding the imposition of the researcher’s own assumptions or biases.

Pitfalls of Phenomenology Research

A common pitfall of phenomenology research is failing to fully grasp the nuances of phenomenological philosophy.

For example, some studies that use Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) do not adequately acknowledge their hermeneutic foundations or the need to engage in the Epoché, which helps limit the researcher’s pre-understandings.

Without this philosophical anchoring, the research is merely thematic analysis instead of phenomenology.

Other pitfalls in phenomenology research include:

- Missing the Phenomenon: Researchers should not solely focus on what is observed or said, or merely reproduce participant statements. Instead, they must uncover implicit meanings and insights into the participant’s lifeworld, providing an idiographic or general description of the phenomenon. Focusing too heavily on analysis can obscure the phenomenon, while excessive thematic structures can result in presenting “results” rather than phenomenological description.

- Misunderstanding the Phenomenological Attitude: Husserl’s bracketing is often misinterpreted as striving for objectivity, when in reality it is a profoundly subjective act to perceive the world from a fresh perspective. The focus should not be on judging reality, but on exploring experiential appearances and uncovering taken-for-granted aspects of experience. Reproducing participants’ words without going beyond their taken-for-granted understandings can cause research to get stuck in the “natural attitude”.

- Presenting an Insufficiently Holistic Account: Phenomenological studies should not just explore one aspect of consciousness or experience without considering intersubjectivity. A study that only examines an individual’s thoughts or feelings without considering the body or social context misses the point of phenomenology. Good analysis acknowledges existential being and lifeworldly dimensions like embodiment, relationships, time, and space.

- Seeing Subjectivity as Located Within an Individual: Ascribing cognition or emotion solely within individuals perpetuates the dualisms that phenomenology aims to dismantle, such as individual/social, body/mind, self/other, and internal/external. Phenomenology emphasizes a worldly matrix of meaning formed through relationships, shared language, and cultural history, highlighting the interconnectedness of individuals and the world.

- Killing the Phenomenon in Trying to be Scientifically Rigorous: Phenomenological studies that include a large number of participants in a misguided attempt to generalize findings risk being superficial and missing the essence of phenomenology. Similarly, reports that use overly intellectualized language or a detached “scientific” voice compromise the description of the lived experience.

Convincing phenomenological research should:

- Provide a rich and evocative description of the phenomenon.

- Focus on pre-reflective experience and consciousness rather than reproducing participant statements or researcher assumptions.

- Be grounded in phenomenological philosophy.

- Engage with the layered complexity and ambiguity of embodied, intersubjective, and lifeworldly meanings.

Despite ongoing debates among scholars about the best way to apply phenomenology, they share a commitment to an approach of openness and wonder.

This requires discipline, practice, and patience throughout the research process. Phenomenology has the potential to reveal new insights into the nature of lived experience.

Further Information

- Dorfman, E. (2009). History of the lifeworld: From Husserl to Merleau-Ponty. Philosophy Today , 53 (3), 294–303.

- Hanna, R. (2014). Husserl’s crisis and our crisis. International Journal of Philosophical Studies , 22 (5), 752–770.

- Held, K. Husserl’s Phenomenology of the Life-World. In D. Welton (Ed.), The New Husserl: A Critical Reader (pp. 32–62). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Nenon, T. (2015). Husserl and Heidegger on the Social Dimensions of the Life-World. In L. Učník, I. Chvatík, & A. Williams (Eds.), The Phenomenological Critique of Mathematisation and the Question of Responsibility (pp. 175–184). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Dillon, M. C. (1997). Merleau-Ponty’s Ontology . 2nd edition. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Overgaard, S. (2007). Wittgenstein and Other Minds: Rethinking Subjectivity and Intersubjectivity with Wittgenstein, Levinas, and Husserl . New York and London: Routledge.

- Steinbock, A. (1995). Home and Beyond: Generative Phenomenology after Husserl . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Theunissen, M. (1986). The Other: Studies in the Social Ontology of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Buber , trans. C. Macann. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Ferguson, H. (2006). Phenomenological Sociology: Insight and Experience in Modern Society . London: SAGE Publications.

- Garfinkel, H. (1984). Studies in Ethnomethodology . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Schutz, A. (1972). The Problem of Social Reality: Collected Papers I . The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Broome, M. R., Harland, R., Owen, G. S., & Stringaris, A. (Eds.). (2012). The Maudsley Reader in Phenomenological Psychiatry . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Finlay, L. (2009). Debating phenomenological research methods. Phenomenology & Practice , 3 (1), 6–25.

- Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2012). The Phenomenological Mind . 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- Katz, D. (1989). The World of Touch , trans. L.E. Krueger. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fodor, J. (1987). Psychosemantics . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- From, F. (1953). Om oplevelsen af andres adfærd: Et bidrag til den menneskelige adfærds fænomenologi . Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag.

- Galileo, G. (1957). Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo . New York: Anchor House.

- Gadamer, H. (1991). Truth and method (J. Weinsheimer & D. Marshall, Trans.; 2nd ed.). New York: Crossroads. (Original work published 1975)

- Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery . New York: Basic Books.

- Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? (A. Goldberg & P. Stepansky, Eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Orange, D., Atwood, G., & Stolorow, R. (1997). Working intersubjectively: Contextualism in psychoanalytic practice . Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Stolorow, R., & Atwood, G. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life . Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Connell, R. W. (1985). Teachers’ Work . Sydney, Allen & Unwin.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, Aldine.

- Gorden, R. L. (1969). Interviewing: Strategy, Techniques and Tactics . Homewood Ill, Dorsey Press.

- Husserl, E. (1970) trans D Carr Logical investigations . New York: Humanities Press.

- Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies , 8 , 279–303.

- Measor, L. (1985). Interviewing: A Strategy in Qualitative Research. In R Burgess (Ed.) Strategies of Educational Research: Qualitative Methods . Lewes, Falmer Press.

- Shaw, R. (2019). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In M. Forrester & C. Sullivan (Eds.), Doing qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide (2nd ed., pp. 185–208). SAGE.

- Landridge D. (2007). Phenomenological Psychology . Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Mass Communication Theory

Mass communication theory: from theory to practical application, writing good qualitative research questions.

Got a great handout a while back that I stumbled over today, hopefully it’s as helpful to you as it was to me. Here are the steps for writing good (mass communication of course) qualitative research questions:

Specify the research problem: the practical issue that leads to a need for your study.

Complete these sentences:

- “The topic for this study will be…”

- “This study needs to be conducted because…”

How to write a good qualitative purpose statement: a statement that provides the major objective or intent or roadmap to the study. Fulfill the following criteria:

- Single sentence

- Include the purpose of the study

- Include the central phenomenon

- Use qualitative words e.g. explore, understand, discover

- Note the participants (if any)

- State the research site

A good place to start: The purpose of this ______________ (narrative, phenomenological, grounded theory, ethnographic, case, etc.) study is (was? will be?) will be to ____________ (understand, describe, develop, discover) the _____________ (central phenomenon of the study) for ______________ (the participants) at (the site). At this stage in the research, the ___________ (central phenomenon) will be generally defined as ____________ (a general definition of the central concept).

Research questions serve to narrow the purpose. There are two types: Central

- The most general questions you could ask

Sub-questions

- Subdivides central question into more specific topical questions

- Limited number

Use good qualitative wording for these questions.

- Begin with words such as “how” or “what”

- Tell the reader what you are attempting to “discover,” “generate,” “explore,” “identify,” or “describe”

- Ask “what happened?” to help craft your description

- Ask “what was the meaning to people of what happened?” to understand your results

- Ask “what happened over time?” to explore the process

Avoid words such as: relate, influence, impact, effect, cause

Scripts to help design qualitative central and sub-questions: Central question script (usually use only one):

- “What does it mean to _________________ (central phenomenon)?”

- “How would ______________ (participants) describe (central phenomenon)?”

Sub-question script:

- “What _________ (aspect) does __________ (participant) engage in as a _____________ (central phenomenon)?”

- Cresswell. J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. Principles of qualitative research: Designing a qualitative study. You can download the entire document here .

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

19 thoughts on “ Writing Good Qualitative Research Questions ”

Pingback: 9 Tips to Conducting Accurate Qualitative Research – YUSA'AD

Pingback: Qualitative research methods : Optimal Workshop

Pingback: UX book review: Shane, the lone ethnographer — A beginner’s guide to ethnography : Optimal Workshop

very clear and helpful, thanks!

Pingback: 9 Tips to Conducting Accurate Qualitative Research – Like A Girl

Pingback: 9 Tips to Conducting Accurate Qualitative Research

Thank you helpful

Pingback: UX book review: Shane, the lone ethnographer — A beginner's guide to ethnography - Optimal Workshop

Pingback: Qualitative research methods - Optimal Workshop

Reblogged this on VeryVexed .

This is helpful, thank you.

Pingback: How to Write Survey Questions

This is incredibly helpful. Thank you!

Reblogged this on Writing Across the Curriculum @ Staten Island and commented: Some great ideas from the folks as masscommtheory.com!

You saved my sanity! Thanks so so much! Juli

Thanks for this. It was very simple and clear. A lot of the textbooks I am reading for my EdD aren’t as easy to understand!

Pingback: Beginners Guide to the Research Proposal | Mass Communication Theory

Pingback: claytonravine

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Qualitative study design: Phenomenology

- Qualitative study design

Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Used to describe the lived experience of individuals.

- Now called Descriptive Phenomenology, this study design is one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative research within the social and health sciences.

- Used to describe how human beings experience a certain phenomenon. The researcher asks, “What is this experience like?’, ‘What does this experience mean?’ or ‘How does this ‘lived experience’ present itself to the participant?’

- Attempts to set aside biases and preconceived assumptions about human experiences, feelings, and responses to a particular situation.

- Experience may involve perception, thought, memory, imagination, and emotion or feeling.

- Usually (but not always) involves a small sample of participants (approx. 10-15).

- Analysis includes an attempt to identify themes or, if possible, make generalizations in relation to how a particular phenomenon is perceived or experienced.

Methods used include:

- participant observation

- in-depth interviews with open-ended questions

- conversations and focus workshops.

Researchers may also examine written records of experiences such as diaries, journals, art, poetry and music.

Descriptive phenomenology is a powerful way to understand subjective experience and to gain insights around people’s actions and motivations, cutting through long-held assumptions and challenging conventional wisdom. It may contribute to the development of new theories, changes in policies, or changes in responses.

Limitations

- Does not suit all health research questions. For example, an evaluation of a health service may be better carried out by means of a descriptive qualitative design, where highly structured questions aim to garner participant’s views, rather than their lived experience.

- Participants may not be able to express themselves articulately enough due to language barriers, cognition, age, or other factors.

- Gathering data and data analysis may be time consuming and laborious.

- Results require interpretation without researcher bias.

- Does not produce easily generalisable data.

Example questions

- How do cancer patients cope with a terminal diagnosis?

- What is it like to survive a plane crash?

- What are the experiences of long-term carers of family members with a serious illness or disability?

- What is it like to be trapped in a natural disaster, such as a flood or earthquake?

Example studies

- The patient-body relationship and the "lived experience" of a facial burn injury: a phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment . Individual interviews were carried out for this study.

- The use of group descriptive phenomenology within a mixed methods study to understand the experience of music therapy for women with breast cancer . Example of a study in which focus group interviews were carried out.

- Understanding the experience of midlife women taking part in a work-life balance career coaching programme: An interpretative phenomenological analysis . Example of a study using action research.

- Holloway, I. & Galvin, K. (2017). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (Fourth ed.): John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Rodriguez, A., & Smith, J. (2018). Phenomenology as a healthcare research method . Journal of Evidence Based Nursing , 21(4), 96-98. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102990

- << Previous: Methodologies

- Next: Grounded theory >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 11:46 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19.4 Phenomenology

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with phenomenological design

- Determine when a phenomenological study design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of phenomenology research?

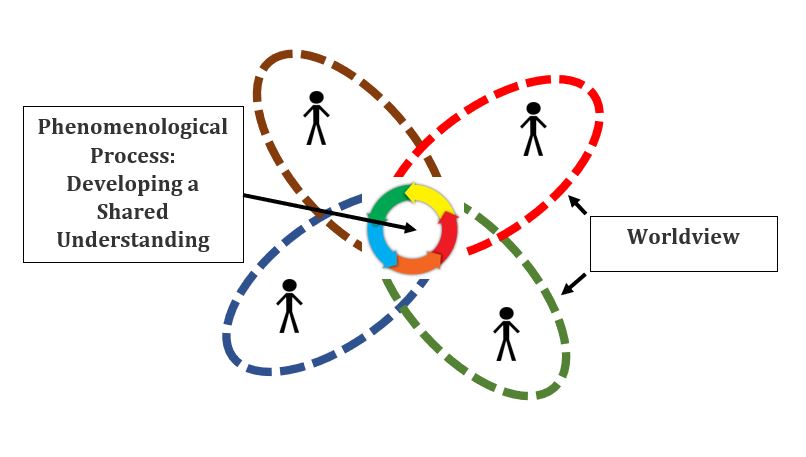

Phenomenology is concerned with capturing and describing the lived experience of some event or “phenomenon” for a group of people. One of the major assumptions in this vein of research is that we all experience and interpret our encounters with the world around us. Furthermore, we interpret these experiences from our own unique worldview, shaped by our beliefs, values and previous encounters. We then go on to attach our own meaning to them. By studying the meaning that people attach to their experiences, phenomenologists hope to understand these experiences in much richer detail. Ideally, this allows them to translate a unidimensional idea that they are studying into a multidimensional understanding that reflects the complex and dynamic ways we experience and interpret our world.

As an example, perhaps we want to study the experience of being a student in a social work research class, something you might have some first-hand knowledge with. Putting yourself into the role of a participant in this study, each of you has a unique perspective coming into the class. Maybe some of you are excited by school and find classes enjoyable; others may find classes boring. Some may find learning challenging, especially with traditional instructional methods; while others find it easy to digest materials and understand new ideas. You may have heard from your friends, who took this class last year, that research is hard and the professor is evil; while the student sitting next to you has a mother who is a researcher and they are looking forward to developing a better understanding of what she does. The lens through which you interpret your experiences in the class will likely shape the meaning you attach to it, and no two students will have the exact same experience, even though you all share in the phenomenon—the class itself. As a phenomenologist, I would want to try to capture how various students experienced the class. I might explore topics like: what did you think about the class, what feelings were associated with the class as a whole or different aspects of the class, what aspects of the class impacted you and how, etc. I would likely find similarities and differences across your accounts and I would seek to bring these together as themes to help more fully understand the phenomenon of being a student in a social work research class. From a more professionally practical standpoint, I would challenge you to think about your current or future clients. Which of their experiences might it be helpful for you to better understand as you are delivering services? Here are some general examples of phenomenological questions that might apply to your work:

- What does it mean to be part of an organization or a movement?

- What is it like to ask for help or seek services?

- What is it like to live with a chronic disease or condition?

- What do people go through when they experience discrimination based on some characteristic or ascribed status?

Just to recap, phenomenology assumes that…

- Each person has a unique worldview, shaped by their life experiences

- This worldview is the lens through which that person interprets and makes meaning of new phenomena or experiences

- By researching the meaning that people attach to a phenomenon and bringing individual perspectives together, we can potentially arrive at a shared understanding of that phenomenon that has more depth, detail and nuance than any one of us could possess individually.

What is involved in phenomenology research?

Again, phenomenological studies are best suited for research questions that center around understanding a number of different peoples’ experiences of particular event or condition, and the understanding that they attach to it. As such, the process of phenomenological research involves gathering, comparing, and synthesizing these subjective experiences into one more comprehensive description of the phenomenon. After reading the results of a phenomenological study, a person should walk away with a broader, more nuanced understanding of what the lived experience of the phenomenon is.

While it isn’t a hard and fast rule, you are most likely to use purposive sampling to recruit your sample for a phenomenological project. The logic behind this sampling method is pretty straightforward since you want to recruit people that have had a specific experience or been exposed to a particular phenomenon, you will intentionally or purposefully be reaching out to people that you know have had this experience. Furthermore, you may want to capture the perspectives of people with different worldviews on your topic to support developing the richest understanding of the phenomenon. Your goal is to target a range of people in your recruitment because of their unique perspectives.

For instance, let’s say that you are interested in studying the subjective experience of having a diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). We might imagine that this experience would be quite different across time periods (e.g. the 1980’s vs. the 2010’s), geographic locations (e.g. New York City vs. the Kingdom of Eswatini in southern Africa), and social group (e.g. Conservative Christian church leaders in the southern US vs. sex workers in Brazil). By using purposive sampling, we are attempting to intentionally generate a varied and diverse group of participants who all have a lived experience of the same phenomenon. Of course, a purposive recruitment approach assumes that we have a working knowledge of who has encountered the phenomenon we are studying. If we don’t have this knowledge, we may need to use other non-probability approaches, like convenience or snowball sampling. Depending on the topic you are studying and the diversity you are attempting to capture, Creswell (2013) suggests that a reasonable sample size may range from 3 -25 participants for a phenomenological study. Regardless of which sample size you choose, you will want a clear rationale that supports why you chose it.

Most often, phenomenological studies rely on interviewing. Again, the logic here is pretty clear—if we are attempting to gather people’s understanding of a certain experience, the most direct way is to ask them. We may start with relatively unstructured questions: “can you tell me about your experience with…..”, “what was it it like to….”, “what does it mean to…”. However, as our interview progresses, we are likely to develop probes and additional questions, leading to a semi-structured feel, as we seek to better understand the emerging dimensions of the topic that we are studying. Phenomenology embodies the iterative process that has been discussed; as we begin to analyze the data and detect new concept or ideas, we will integrate that into our continuing efforts at collecting new data. So let’s say that we have conducted a couple of interviews and begin coding our data. Based on these codes, we decide to add new probes to our interview guide because we want to see if future interviewees also incorporate these ideas into how they understand the phenomenon. Also, let’s say that in our tenth interview a new idea is shared by the participant. As part of this iterative process, we may go back to previous interviewees to get their thoughts about this new idea. It is not uncommon in phenomenological studies to interview participants more than once. Of course, other types of data (e.g. observations, focus groups, artifacts) are not precluded from phenomenological research, but interviewing tends to be the mainstay.

In a general sense, phenomenological data analysis is about bringing together the individual accounts of the phenomenon (most often interview transcripts) and searching for themes across these accounts to capture the essence or description of the phenomenon. This description should be one that reflects a shared understanding as well as the context in which that understanding exists. This essence will be the end result of your analysis.

To arrive at this essence, different phenomenological traditions have emerged to guide data analysis, including approaches advanced by van Manen (2016) [1] , Moustakas (1994) [2] , Polikinghorne (1989) [3] and Giorgi (2009) [4] . One of the main differences between these models is how the researcher accounts for and utilizes their influence during the research process. Just like participants, it is expected in phenomenological traditions that the researcher also possesses their own worldview. The researcher’s worldview influences all aspects of the research process and phenomenology generally encourages the researcher to account for this influence. This may be done through activities like reflexive journaling (discussed in Chapter 20 on qualitative rigor) or through bracketing (discussed in Chapter 19 on qualitative analysis), both tools helping researchers capture their own thoughts and reactions towards the data and its emerging meaning. Some of these phenomenological approaches suggest that we work to integrate the researcher’s perspective into the analysis process, like van Manen; while others suggest that we need to identify our influence so that we can set it aside as best as possible, like Moustakas (Creswell, 2013). [5] For a more detailed understanding of these approaches, please refer to the resources listed for these authors in the box below.

Key Takeaways

- Phenomenology is a qualitative research tradition that seeks to capture the lived experience of some social phenomenon across some group of participants who have direct, first-hand experience with it.

- As a phenomenological researcher, you will need to bring together individual experiences with the topic being studied, including your own, and weave them together into a shared understanding that captures the “essence” of the phenomenon for all participants.

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- As you think about the areas of social work that you are interested in, what life experiences do you need to learn more about to help develop your empathy and humility as a social work practitioner in this field of practice?

To learn more about phenomenological research

Errasti‐Ibarrondo et al. (2018). Conducting phenomenological research: Rationalizing the methods and rigour of the phenomenology of practice .

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach . Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Koopman, O. (2015). Phenomenology as a potential methodology for subjective knowing in science education research .

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Newberry, A. M. (2012). Social work and hermeneutic phenomenology .

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer.

Seymour, T. (2019, January, 30). Phenomenological qualitative research design .

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing . New York: Routledge.

For examples of phenomenological research