What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

We define an argumentative essay as a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. The purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular viewpoint or action. In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a controversial or debatable topic and supports their position with evidence, reasoning, and examples. The essay should also address counterarguments, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic.

Table of Contents

What is an argumentative essay .

- Argumentative essay structure

- Argumentative essay outline

- Types of argument claims

How to write an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay writing tips

- Good argumentative essay example

How to write a good thesis

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents a coherent and logical analysis of a specific topic. 1 The goal is to convince the reader to accept the writer’s point of view or opinion on a particular issue. Here are the key elements of an argumentative essay:

- Thesis Statement : The central claim or argument that the essay aims to prove.

- Introduction : Provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph addresses a specific aspect of the argument, presents evidence, and may include counter arguments. Articulate your thesis statement better with Paperpal. Start writing now!

- Evidence : Supports the main argument with relevant facts, examples, statistics, or expert opinions.

- Counterarguments : Anticipates and addresses opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall argument.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the main points, reinforces the thesis, and may suggest implications or actions.

Argumentative essay structure

Aristotelian, Rogerian, and Toulmin are three distinct approaches to argumentative essay structures, each with its principles and methods. 2 The choice depends on the purpose and nature of the topic. Here’s an overview of each type of argumentative essay format.

| ) | ||

| : Introduce the topic. Provide background information. Present the thesis statement or main argument. | : Introduce the issue. Provide background information. Establish a neutral and respectful tone. | : Introduce the issue. Provide background information. Present the claim or thesis. |

| : Provide context or background information. Set the stage for the argument. | : Describe opposing viewpoints without judgment. Show an understanding of the different perspectives. | : Clearly state the main argument or claim. |

| : Present the main argument with supporting evidence. Use logical reasoning. Address counterarguments and refute them. | : Present your thesis or main argument. Identify areas of common ground between opposing views. | : Provide evidence to support the claim. Include facts, examples, and statistics. |

| : Acknowledge opposing views. Provide counterarguments and evidence against them. | : Present your arguments while acknowledging opposing views. Emphasize shared values or goals. Seek compromise and understanding. | : Explain the reasoning that connects the evidence to the claim. Make the implicit assumptions explicit. |

| : Summarize the main points. Reassert the thesis. End with a strong concluding statement. | : Summarize areas of agreement. Reiterate the importance of finding common ground. End on a positive note. | : Provide additional support for the warrant. Offer further justification for the reasoning. |

| Address potential counterarguments. Provide evidence and reasoning to refute counterclaims. | ||

| Respond to counterarguments and reinforce the original claim. | ||

| Summarize the main points. Reinforce the strength of the argument. |

Have a looming deadline for your argumentative essay? Write 2x faster with Paperpal – Start now!

Argumentative essay outline

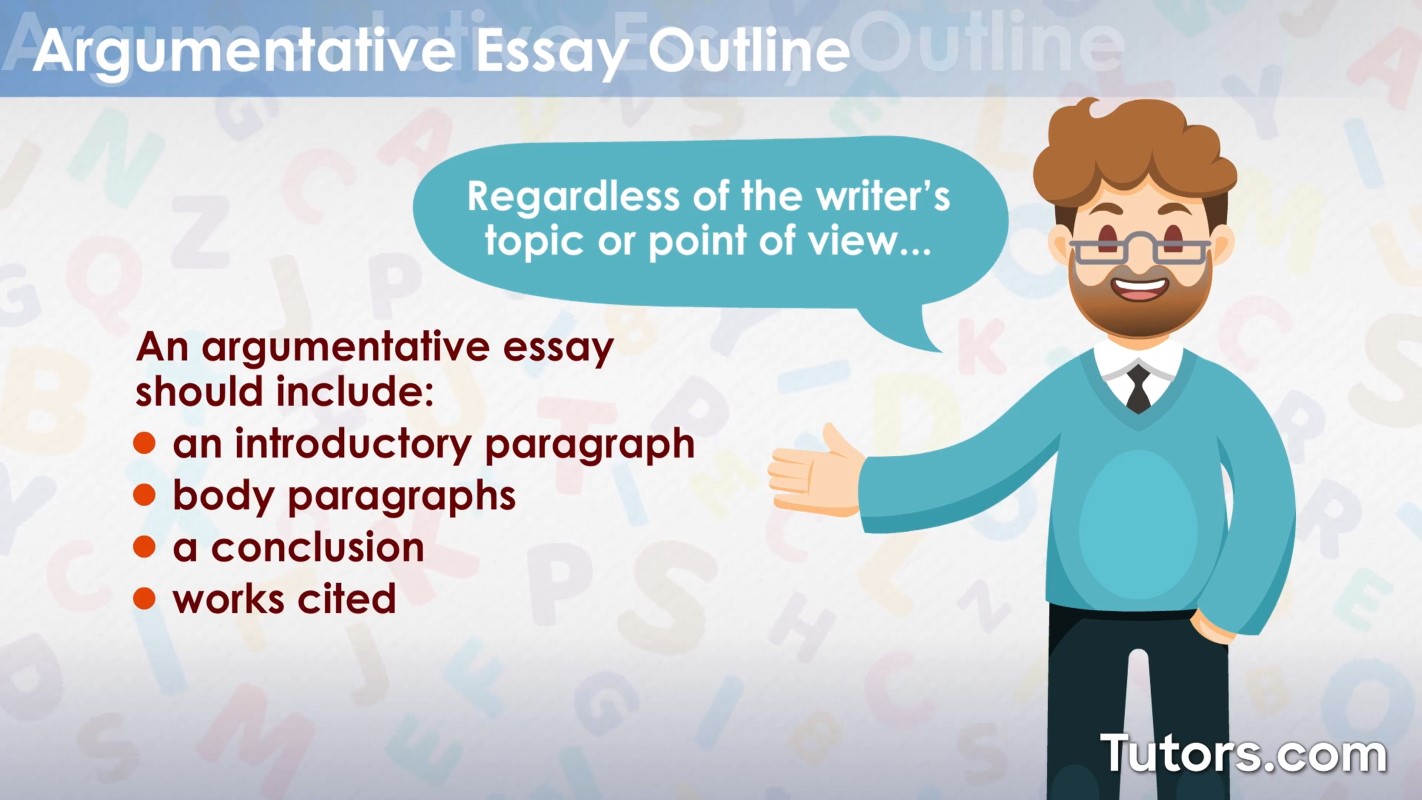

An argumentative essay presents a specific claim or argument and supports it with evidence and reasoning. Here’s an outline for an argumentative essay, along with examples for each section: 3

1. Introduction :

- Hook : Start with a compelling statement, question, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

Example: “Did you know that plastic pollution is threatening marine life at an alarming rate?”

- Background information : Provide brief context about the issue.

Example: “Plastic pollution has become a global environmental concern, with millions of tons of plastic waste entering our oceans yearly.”

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position.

Example: “We must take immediate action to reduce plastic usage and implement more sustainable alternatives to protect our marine ecosystem.”

2. Body Paragraphs :

- Topic sentence : Introduce the main idea of each paragraph.

Example: “The first step towards addressing the plastic pollution crisis is reducing single-use plastic consumption.”

- Evidence/Support : Provide evidence, facts, statistics, or examples that support your argument.

Example: “Research shows that plastic straws alone contribute to millions of tons of plastic waste annually, and many marine animals suffer from ingestion or entanglement.”

- Counterargument/Refutation : Acknowledge and refute opposing viewpoints.

Example: “Some argue that banning plastic straws is inconvenient for consumers, but the long-term environmental benefits far outweigh the temporary inconvenience.”

- Transition : Connect each paragraph to the next.

Example: “Having addressed the issue of single-use plastics, the focus must now shift to promoting sustainable alternatives.”

3. Counterargument Paragraph :

- Acknowledgement of opposing views : Recognize alternative perspectives on the issue.

Example: “While some may argue that individual actions cannot significantly impact global plastic pollution, the cumulative effect of collective efforts must be considered.”

- Counterargument and rebuttal : Present and refute the main counterargument.

Example: “However, individual actions, when multiplied across millions of people, can substantially reduce plastic waste. Small changes in behavior, such as using reusable bags and containers, can have a significant positive impact.”

4. Conclusion :

- Restatement of thesis : Summarize your main argument.

Example: “In conclusion, adopting sustainable practices and reducing single-use plastic is crucial for preserving our oceans and marine life.”

- Call to action : Encourage the reader to take specific steps or consider the argument’s implications.

Example: “It is our responsibility to make environmentally conscious choices and advocate for policies that prioritize the health of our planet. By collectively embracing sustainable alternatives, we can contribute to a cleaner and healthier future.”

Types of argument claims

A claim is a statement or proposition a writer puts forward with evidence to persuade the reader. 4 Here are some common types of argument claims, along with examples:

- Fact Claims : These claims assert that something is true or false and can often be verified through evidence. Example: “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Value Claims : Value claims express judgments about the worth or morality of something, often based on personal beliefs or societal values. Example: “Organic farming is more ethical than conventional farming.”

- Policy Claims : Policy claims propose a course of action or argue for a specific policy, law, or regulation change. Example: “Schools should adopt a year-round education system to improve student learning outcomes.”

- Cause and Effect Claims : These claims argue that one event or condition leads to another, establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Example: “Excessive use of social media is a leading cause of increased feelings of loneliness among young adults.”

- Definition Claims : Definition claims assert the meaning or classification of a concept or term. Example: “Artificial intelligence can be defined as machines exhibiting human-like cognitive functions.”

- Comparative Claims : Comparative claims assert that one thing is better or worse than another in certain respects. Example: “Online education is more cost-effective than traditional classroom learning.”

- Evaluation Claims : Evaluation claims assess the quality, significance, or effectiveness of something based on specific criteria. Example: “The new healthcare policy is more effective in providing affordable healthcare to all citizens.”

Understanding these argument claims can help writers construct more persuasive and well-supported arguments tailored to the specific nature of the claim.

If you’re wondering how to start an argumentative essay, here’s a step-by-step guide to help you with the argumentative essay format and writing process.

- Choose a Topic: Select a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Ensure that the topic is debatable and has two or more sides.

- Define Your Position: Clearly state your stance on the issue. Consider opposing viewpoints and be ready to counter them.

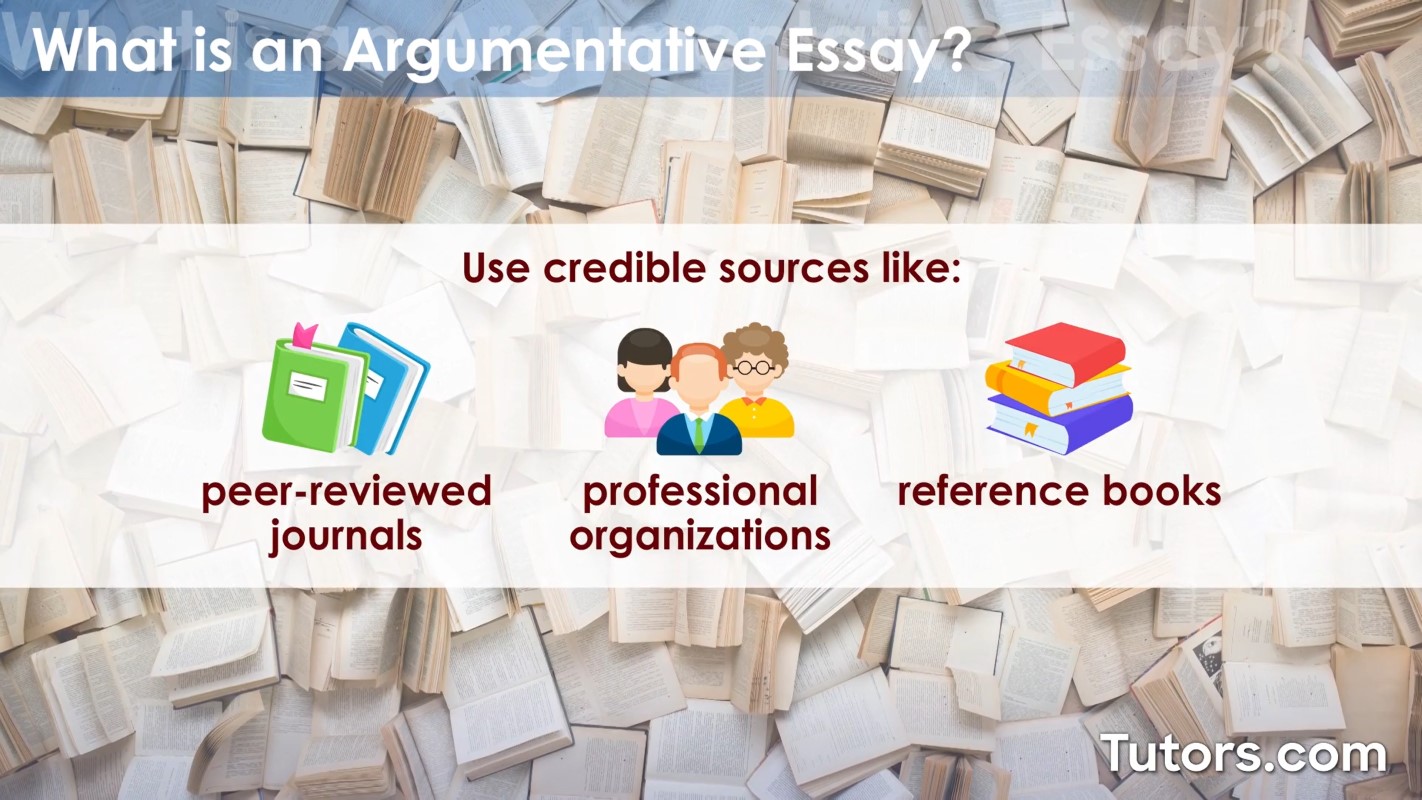

- Conduct Research: Gather relevant information from credible sources, such as books, articles, and academic journals. Take notes on key points and supporting evidence.

- Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a concise and clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument. Convey your position on the issue and provide a roadmap for the essay.

- Outline Your Argumentative Essay: Organize your ideas logically by creating an outline. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis.

- Write the Introduction: Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a surprising fact). Provide background information on the topic. Present your thesis statement at the end of the introduction.

- Develop Body Paragraphs: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis. Support your points with evidence and examples. Address counterarguments and refute them to strengthen your position. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing viewpoints. Anticipate objections and provide evidence to counter them.

- Write the Conclusion: Summarize the main points of your argumentative essay. Reinforce the significance of your argument. End with a call to action, a prediction, or a thought-provoking statement.

- Revise, Edit, and Share: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Share your essay with peers, friends, or instructors for constructive feedback.

- Finalize Your Argumentative Essay: Make final edits based on feedback received. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting and citation style.

Struggling to start your argumentative essay? Paperpal can help – try now!

Argumentative essay writing tips

Here are eight strategies to craft a compelling argumentative essay:

- Choose a Clear and Controversial Topic : Select a topic that sparks debate and has opposing viewpoints. A clear and controversial issue provides a solid foundation for a strong argument.

- Conduct Thorough Research : Gather relevant information from reputable sources to support your argument. Use a variety of sources, such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, to strengthen your position.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement : Clearly articulate your main argument in a concise thesis statement. Your thesis should convey your stance on the issue and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow your argument.

- Develop a Logical Structure : Organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on a specific point of evidence that contributes to your overall argument. Ensure a logical flow from one point to the next.

- Provide Strong Evidence : Support your claims with solid evidence. Use facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Be sure to cite your sources appropriately to maintain credibility.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counterarguments. Addressing and refuting alternative perspectives strengthens your essay and demonstrates a thorough understanding of the issue. Be mindful of maintaining a respectful tone even when discussing opposing views.

- Use Persuasive Language : Employ persuasive language to make your points effectively. Avoid emotional appeals without supporting evidence and strive for a respectful and professional tone.

- Craft a Compelling Conclusion : Summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave a lasting impression in your conclusion. Encourage readers to consider the implications of your argument and potentially take action.

Good argumentative essay example

Let’s consider a sample of argumentative essay on how social media enhances connectivity:

In the digital age, social media has emerged as a powerful tool that transcends geographical boundaries, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and providing a platform for an array of voices to be heard. While critics argue that social media fosters division and amplifies negativity, it is essential to recognize the positive aspects of this digital revolution and how it enhances connectivity by providing a platform for diverse voices to flourish. One of the primary benefits of social media is its ability to facilitate instant communication and connection across the globe. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram break down geographical barriers, enabling people to establish and maintain relationships regardless of physical location and fostering a sense of global community. Furthermore, social media has transformed how people stay connected with friends and family. Whether separated by miles or time zones, social media ensures that relationships remain dynamic and relevant, contributing to a more interconnected world. Moreover, social media has played a pivotal role in giving voice to social justice movements and marginalized communities. Movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #ClimateStrike have gained momentum through social media, allowing individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on a global scale. This digital activism can shape public opinion and hold institutions accountable. Social media platforms provide a dynamic space for open dialogue and discourse. Users can engage in discussions, share information, and challenge each other’s perspectives, fostering a culture of critical thinking. This open exchange of ideas contributes to a more informed and enlightened society where individuals can broaden their horizons and develop a nuanced understanding of complex issues. While criticisms of social media abound, it is crucial to recognize its positive impact on connectivity and the amplification of diverse voices. Social media transcends physical and cultural barriers, connecting people across the globe and providing a platform for marginalized voices to be heard. By fostering open dialogue and facilitating the exchange of ideas, social media contributes to a more interconnected and empowered society. Embracing the positive aspects of social media allows us to harness its potential for positive change and collective growth.

- Clearly Define Your Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the core of your argumentative essay. Clearly articulate your main argument or position on the issue. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Provide Strong Supporting Evidence: Back up your thesis with solid evidence from reliable sources and examples. This can include facts, statistics, expert opinions, anecdotes, or real-life examples. Make sure your evidence is relevant to your argument, as it impacts the overall persuasiveness of your thesis.

- Anticipate Counterarguments and Address Them: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen credibility. This also shows that you engage critically with the topic rather than presenting a one-sided argument.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Writing a winning argumentative essay not only showcases your ability to critically analyze a topic but also demonstrates your skill in persuasively presenting your stance backed by evidence. Achieving this level of writing excellence can be time-consuming. This is where Paperpal, your AI academic writing assistant, steps in to revolutionize the way you approach argumentative essays. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use Paperpal to write your essay:

- Sign Up or Log In: Begin by creating an account or logging into paperpal.com .

- Navigate to Paperpal Copilot: Once logged in, proceed to the Templates section from the side navigation bar.

- Generate an essay outline: Under Templates, click on the ‘Outline’ tab and choose ‘Essay’ from the options and provide your topic to generate an outline.

- Develop your essay: Use this structured outline as a guide to flesh out your essay. If you encounter any roadblocks, click on Brainstorm and get subject-specific assistance, ensuring you stay on track.

- Refine your writing: To elevate the academic tone of your essay, select a paragraph and use the ‘Make Academic’ feature under the ‘Rewrite’ tab, ensuring your argumentative essay resonates with an academic audience.

- Final Touches: Make your argumentative essay submission ready with Paperpal’s language, grammar, consistency and plagiarism checks, and improve your chances of acceptance.

Paperpal not only simplifies the essay writing process but also ensures your argumentative essay is persuasive, well-structured, and academically rigorous. Sign up today and transform how you write argumentative essays.

The length of an argumentative essay can vary, but it typically falls within the range of 1,000 to 2,500 words. However, the specific requirements may depend on the guidelines provided.

You might write an argumentative essay when: 1. You want to convince others of the validity of your position. 2. There is a controversial or debatable issue that requires discussion. 3. You need to present evidence and logical reasoning to support your claims. 4. You want to explore and critically analyze different perspectives on a topic.

Argumentative Essay: Purpose : An argumentative essay aims to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a specific point of view or argument. Structure : It follows a clear structure with an introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, counterarguments and refutations, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is formal and relies on logical reasoning, evidence, and critical analysis. Narrative/Descriptive Essay: Purpose : These aim to tell a story or describe an experience, while a descriptive essay focuses on creating a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. Structure : They may have a more flexible structure. They often include an engaging introduction, a well-developed body that builds the story or description, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is more personal and expressive to evoke emotions or provide sensory details.

- Gladd, J. (2020). Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays. Write What Matters .

- Nimehchisalem, V. (2018). Pyramid of argumentation: Towards an integrated model for teaching and assessing ESL writing. Language & Communication , 5 (2), 185-200.

- Press, B. (2022). Argumentative Essays: A Step-by-Step Guide . Broadview Press.

- Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2005). Argumentation and critical decision making . Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- What is a Narrative Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

Make Your Research Paper Error-Free with Paperpal’s Online Spell Checker

The do’s & don’ts of using generative ai tools ethically in academia, you may also like, how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., apa format: basic guide for researchers, how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to structure an essay.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Argumentative Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is an argumentative essay?

The argumentative essay is a genre of writing that requires the student to investigate a topic; collect, generate, and evaluate evidence; and establish a position on the topic in a concise manner.

Please note : Some confusion may occur between the argumentative essay and the expository essay. These two genres are similar, but the argumentative essay differs from the expository essay in the amount of pre-writing (invention) and research involved. The argumentative essay is commonly assigned as a capstone or final project in first year writing or advanced composition courses and involves lengthy, detailed research. Expository essays involve less research and are shorter in length. Expository essays are often used for in-class writing exercises or tests, such as the GED or GRE.

Argumentative essay assignments generally call for extensive research of literature or previously published material. Argumentative assignments may also require empirical research where the student collects data through interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments. Detailed research allows the student to learn about the topic and to understand different points of view regarding the topic so that she/he may choose a position and support it with the evidence collected during research. Regardless of the amount or type of research involved, argumentative essays must establish a clear thesis and follow sound reasoning.

The structure of the argumentative essay is held together by the following.

- A clear, concise, and defined thesis statement that occurs in the first paragraph of the essay.

In the first paragraph of an argument essay, students should set the context by reviewing the topic in a general way. Next the author should explain why the topic is important ( exigence ) or why readers should care about the issue. Lastly, students should present the thesis statement. It is essential that this thesis statement be appropriately narrowed to follow the guidelines set forth in the assignment. If the student does not master this portion of the essay, it will be quite difficult to compose an effective or persuasive essay.

- Clear and logical transitions between the introduction, body, and conclusion.

Transitions are the mortar that holds the foundation of the essay together. Without logical progression of thought, the reader is unable to follow the essay’s argument, and the structure will collapse. Transitions should wrap up the idea from the previous section and introduce the idea that is to follow in the next section.

- Body paragraphs that include evidential support.

Each paragraph should be limited to the discussion of one general idea. This will allow for clarity and direction throughout the essay. In addition, such conciseness creates an ease of readability for one’s audience. It is important to note that each paragraph in the body of the essay must have some logical connection to the thesis statement in the opening paragraph. Some paragraphs will directly support the thesis statement with evidence collected during research. It is also important to explain how and why the evidence supports the thesis ( warrant ).

However, argumentative essays should also consider and explain differing points of view regarding the topic. Depending on the length of the assignment, students should dedicate one or two paragraphs of an argumentative essay to discussing conflicting opinions on the topic. Rather than explaining how these differing opinions are wrong outright, students should note how opinions that do not align with their thesis might not be well informed or how they might be out of date.

- Evidential support (whether factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal).

The argumentative essay requires well-researched, accurate, detailed, and current information to support the thesis statement and consider other points of view. Some factual, logical, statistical, or anecdotal evidence should support the thesis. However, students must consider multiple points of view when collecting evidence. As noted in the paragraph above, a successful and well-rounded argumentative essay will also discuss opinions not aligning with the thesis. It is unethical to exclude evidence that may not support the thesis. It is not the student’s job to point out how other positions are wrong outright, but rather to explain how other positions may not be well informed or up to date on the topic.

- A conclusion that does not simply restate the thesis, but readdresses it in light of the evidence provided.

It is at this point of the essay that students may begin to struggle. This is the portion of the essay that will leave the most immediate impression on the mind of the reader. Therefore, it must be effective and logical. Do not introduce any new information into the conclusion; rather, synthesize the information presented in the body of the essay. Restate why the topic is important, review the main points, and review your thesis. You may also want to include a short discussion of more research that should be completed in light of your work.

A complete argument

Perhaps it is helpful to think of an essay in terms of a conversation or debate with a classmate. If I were to discuss the cause of World War II and its current effect on those who lived through the tumultuous time, there would be a beginning, middle, and end to the conversation. In fact, if I were to end the argument in the middle of my second point, questions would arise concerning the current effects on those who lived through the conflict. Therefore, the argumentative essay must be complete, and logically so, leaving no doubt as to its intent or argument.

The five-paragraph essay

A common method for writing an argumentative essay is the five-paragraph approach. This is, however, by no means the only formula for writing such essays. If it sounds straightforward, that is because it is; in fact, the method consists of (a) an introductory paragraph (b) three evidentiary body paragraphs that may include discussion of opposing views and (c) a conclusion.

Longer argumentative essays

Complex issues and detailed research call for complex and detailed essays. Argumentative essays discussing a number of research sources or empirical research will most certainly be longer than five paragraphs. Authors may have to discuss the context surrounding the topic, sources of information and their credibility, as well as a number of different opinions on the issue before concluding the essay. Many of these factors will be determined by the assignment.

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

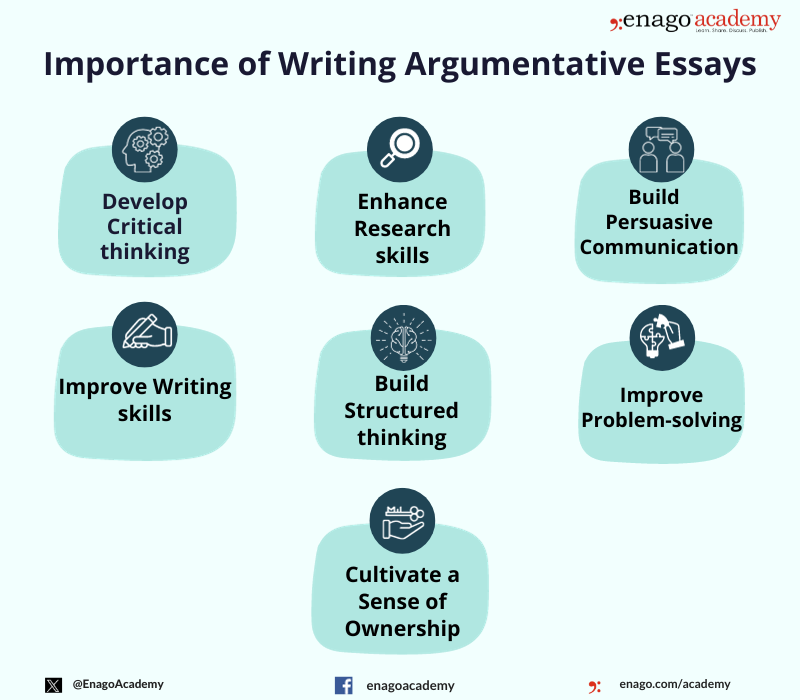

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

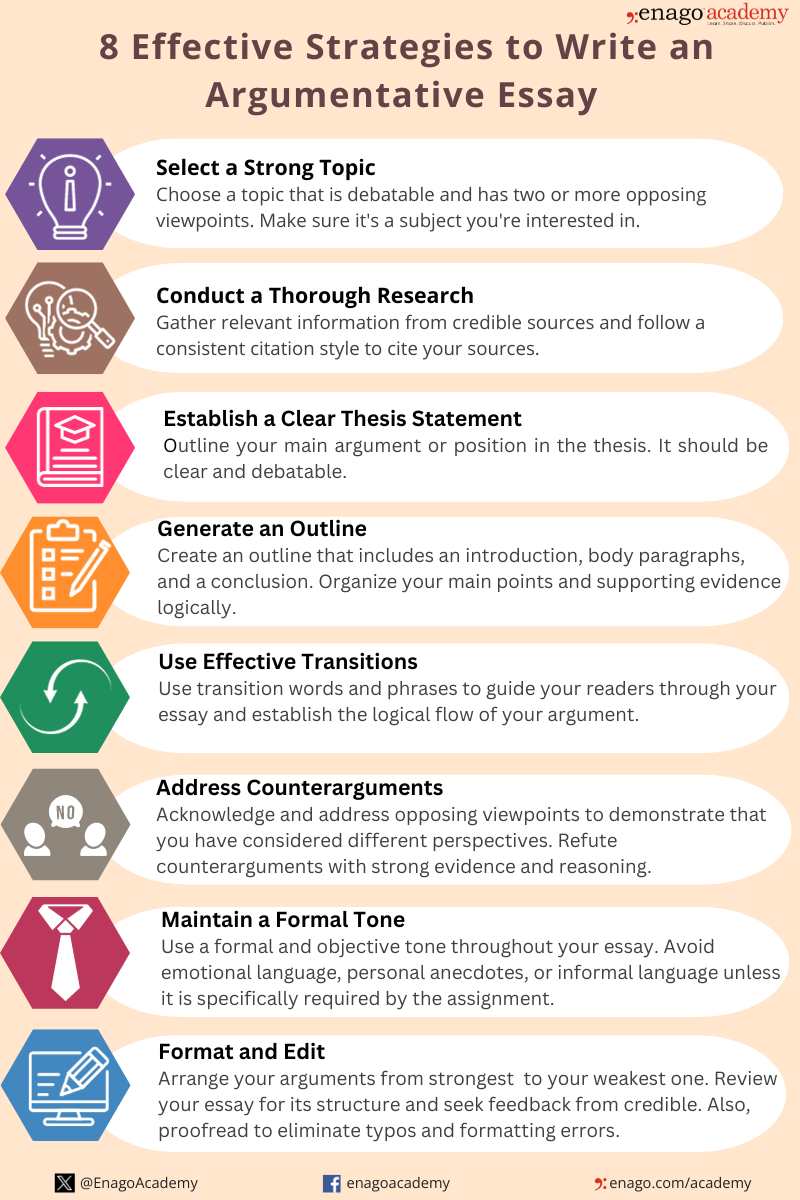

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Excellent article! provides comprehensive and practical guidance for crafting compelling arguments. The emphasis on thorough research and clear thesis statements is particularly valuable. To further enhance your strategies, consider recommending the use of a counterargument paragraph. Addressing and refuting opposing viewpoints can strengthen your position and show a well-rounded understanding of the topic. Additionally, engaging with a community like ATReads, a writers’ social media, can provide valuable feedback and support from fellow writers. Thanks for sharing these insightful tips!

wow incredible ! keep up the good work

I love it thanks for the guidelines

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

Academic Webinars: Transforming knowledge dissemination in the digital age

Digitization has transformed several areas of our lives, including the teaching and learning process. During…

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

Mastering Research Grant Writing in 2024: Navigating new policies and funder demands

Entering the world of grants and government funding can leave you confused; especially when trying…

How to Create a Poster That Stands Out: Tips for a smooth poster presentation

It was the conference season. Judy was excited to present her first poster! She had…

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Industry News

6 Reasons Why There is a Decline in Higher Education Enrollment: Action plan to overcome this crisis

Over the past decade, colleges and universities across the globe have witnessed a concerning trend…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer-Review Week 2023

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Table of Contents

Crafting a convincing argumentative essay can be challenging. You might feel lost about where to begin. But with a systematic approach and helpful tools that simplify sourcing and structuring, mastering good argumentative essay writing becomes achievable.

In this article, we'll explore what argumentative essays are, the critical steps to crafting a compelling argumentative essay, and best practices for essay organization.

What is an argumentative essay?

An argumentative essay asserts a clear position on a controversial or debatable topic and backs it up with evidence and reasoning. They are written to hone critical thinking, structure clear arguments, influence academic and public discourse, underpin reform proposals, and change popular narratives.

The fundamentals of a good argumentative essay

Let's explore the essential components that make argumentative essays compelling.

1 . The foundation: crafting a compelling claim for your argumentative essay

The claim is the cornerstone of your argumentative essay. It represents your main argument or thesis statement , setting the stage for the discussion.

A robust claim is straightforward, debatable, and focused, challenging readers to consider your viewpoint. It's not merely an observation but a stance you're prepared to defend with logic and evidence.

The strength of your essay hinges on the clarity and assertiveness of your claim, guiding readers through your argumentative journey.

2. The structure: Organizing your argument strategically

An effective argumentative essay should follow a logical structure to present your case persuasively. There are three models for structuring your argument essay:

- Classical: Introduce the topic, present the main argument, address counterarguments, and conclude . It is ideal for complex topics and prioritizes logical reasoning.

- Rogerian: Introduce the issue neutrally, acknowledge opposing views, find common ground, and seek compromise. It works well for audiences who dislike confrontational approaches.

- Toulmin: Introduce the issue, state the claim, provide evidence, explain the reasoning, address counterarguments, and reinforce the original claim. It confidently showcases an evidence-backed argument as superior.

Each model provides a framework for methodically supporting your position using evidence and logic. Your chosen structure depends on your argument's complexity, audience, and purpose.

3. The support: Leveraging evidence for your argumentative essay

The key is to select evidence that directly supports your claim, lending weight to your arguments and bolstering your position.

Effective use of evidence strengthens your argument and enhances your credibility, demonstrating thorough research and a deep understanding of the topic at hand.

4. The balance: Acknowledging counterarguments for the argumentative essay

A well-rounded argumentative essay acknowledges that there are two sides to every story. Introducing counterarguments and opposing viewpoints in an argument essay is a strategic move that showcases your awareness of alternative viewpoints.

This element of your argumentative essay demonstrates intellectual honesty and fairness, indicating that you have considered other perspectives before solidifying your position.

5. The counter: Mastering the art of rebuttal

A compelling rebuttal anticipates the counterclaims and methodically counters them, ensuring your position stands unchallenged. By engaging critically with counterarguments in this manner, your essay becomes more resilient and persuasive.

Ultimately, the strength of an argumentative essay is not in avoiding opposing views but in directly confronting them through reasoned debate and evidence-based.

How to write an argumentative essay

The workflow for crafting an effective argumentative essay involves several key steps:

Step 1 — Choosing a topic

Argumentative essay writing starts with selecting a topic with two or more main points so you can argue your position. Avoid topics that are too broad or have a clear right or wrong answer.

Use a semantic search engine to search for papers. Refine by subject area, publication date, citation count, institution, author, journal, and more to narrow down on promising topics. Explore citation interlinkages to ensure you pick a topic with sufficient academic discourse to allow crafting a compelling, evidence-based argument.

Seek an AI research assistant's help to assess a topic's potential and explore various angles quickly. They can generate both generic and custom questions tailored to each research paper. Additionally, look for tools that offer browser extensions . These allow you to interact with papers from sources like ArXiv, PubMed, and Wiley and evaluate potential topics from a broader range of academic databases and repositories.

Step 2 — Develop a thesis statement

Your thesis statement should clearly and concisely state your position on the topic identified. Ensure to develop a clear thesis statement which is a focused, assertive declaration that guides your discussion. Use strong, active language — avoid vague or passive statements. Keep it narrowly focused enough to be adequately supported in your essay.

The SciSpace literature review tool can help you extract thesis statements from existing papers on your chosen topic. Create a custom column called 'thesis statement' to compare multiple perspectives in one place, allowing you to uncover various viewpoints and position your concise thesis statement appropriately.

Ask AI assistants questions or summarize key sections to clarify the positions taken in existing papers. This helps sharpen your thesis statement stance and identify gaps. Locate related papers in similar stances.

Step 3 — Researching and gathering evidence

The evidence you collect lends credibility and weight to your claims, convincing readers of your viewpoint. Effective evidence includes facts, statistics, expert opinions, and real-world examples reinforcing your thesis statement.

Use the SciSpace literature review tool to locate and evaluate high-quality studies. It quickly extracts vital insights, methodologies, findings, and conclusions from papers and presents them in a table format. Build custom tables with your uploaded PDFs or bookmarked papers. These tables can be saved for future reference or exported as CSV for further analysis or sharing.

AI-powered summarization tools can help you quickly grasp the core arguments and positions from lengthy papers. These can condense long sections or entire author viewpoints into concise summaries. Make PDF annotations to add custom notes and highlights to papers for easy reference. Data extraction tools can automatically pull key statistics from PDFs into spreadsheets for detailed quantitative analysis.

Step 4 — Build an outline

The argumentative model you choose will impact your outline's specific structure and progression. If you select the Classical model, your outline will follow a linear structure. On the other hand, if you opt for the Toulmin model, your outline will focus on meticulously mapping out the logical progression of your entire argument. Lastly, if you select the Rogerian model, your outline should explore the opposing viewpoint and seek a middle ground.

While the specific outline structure may vary, always begin the process by stating your central thesis or claim. Identify and organize your argument claims and main supporting points logically, adding 2-3 pieces of evidence under each point. Consider potential counterarguments to your position. Include 1-2 counterarguments for each main point and plan rebuttals to dismantle the opposition's reasoning. This balanced approach strengthens your overall argument.

As you outline, consider saving your notes, highlights, AI-generated summaries, and extracts in a digital notebook. Aggregating all your sources and ideas in one centralized location allows you to quickly refer to them as you draft your outline and essay.

To further enhance your workflow, you can use AI-powered writing or GPT tools to help generate an initial structure based on your crucial essay components, such as your thesis statement, main arguments, supporting evidence, counterarguments, and rebuttals.

Step 5 — Write your essay

Begin the introductory paragraph with a hook — a question, a startling statistic, or a bold statement to draw in your readers. Always logically structure your arguments with smooth transitions between ideas. Ensure the body paragraphs of argumentative essays focus on one central point backed by robust quantitative evidence from credible studies, properly cited.

Refer to the notes, highlights, and evidence you've gathered as you write. Organize these materials so that you can easily access and incorporate them into your draft while maintaining a logical flow. Literature review tables or spreadsheets can be beneficial for keeping track of crucial evidence from multiple sources.

Quote others in a way that blends seamlessly with the narrative flow. For numerical data, contextualize figures with practical examples. Try to pre-empt counterarguments and systematically dismantle them. Maintain an evidence-based, objective tone that avoids absolutism and emotional appeals. If you encounter overly complex sections during the writing process, use a paraphraser tool to rephrase and clarify the language. Finally, neatly tie together the rationale behind your position and directions for further discourse or research.

Step 6 — Edit, revise, and add references

Set the draft aside so that you review it with fresh eyes. Check for clarity, conciseness, logical flow, and grammar. Ensure the body reflects your thesis well. Fill gaps in reasoning. Check that every claim links back to credible evidence. Replace weak arguments. Finally, format your citations and bibliography using your preferred style.

To simplify editing, save the rough draft or entire essay as a PDF and upload it to an AI-based chat-with-PDF tool. Use it to identify gaps in reasoning, weaker arguments requiring ample evidence, structural issues hampering the clarity of ideas, and suggestions for strengthening your essay.

Use a citation tool to generate citations for sources instantly quoted and quickly compile your bibliography or works cited in RIS/BibTex formats. Export the updated literature review tables as handy CSV files to share with co-authors or reviewers in collaborative projects or attach them as supplementary data for journal submissions. You can also refer to this article that provides you with argumentative essay writing tips .

Final thoughts

Remember, the strength of your argumentative essay lies in the clarity of your strong argument, the robustness of supporting evidence, and the consideration with which you treat opposing viewpoints. Refining these core skills will make you a sharper, more convincing writer and communicator.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

59 Introduction to Argumentative Writing

Joel Gladd and Amy Minervini

by Joel Gladd and Amy Minervini

Argumentative writing, also referred to as persuasive writing, is a cornerstone of any first-year writing course. We encounter arguments on daily basis, in both formal and informal contexts. Most of the time, however, we don’t realize how the arguments are actually working. This example developed by Ohio State’s University Library shows how a relatively informal argument may unfold. The dialogue has been annotated to show what kinds of rhetorical elements tend to appear in casual arguments.

As the example above shows, a number of elements typically play a role in most well-developed arguments:

- a question that doesn’t have a straightforward answer

- a claim that responds to the question

- one or more reasons for accepting the claim

- evidence that backs each reason

- objections & response to objections

We often employ many or all of these elements in everyday life, when debating current issues with friends and family. It just unfolds in a messier way than your academic essay will need to structure the conversation. However, even though academic persuasive essays rely on some techniques you’re already familiar with, certain strategies are less well-known, and even certain obvious elements, such as using “evidence” to back a claim, has a certain flavor in more formal environments that some students may not find obvious.

Different models have been proposed for how to best package the elements above. The three models most commonly employed in academic writing are the Aristotelian (classical) , Toulmin , and Rogerian , covered in this chapter. The proposal method is also included though this strategy focuses on solutions rather than problems.

Key Characteristics:

Argumentative writing generally exhibits the following:

- Presents a particular position/side of an issue

- Attempts to persuade the reader to the writer’s side

- Uses elements of rhetoric and strategies that include the integration of logos, pathos, ethos, and kairos in intentional and meaningful ways

- Presents information, data, and research as part of the evidence/support (logos)

- Relies on real-world stories and examples to nurture empathy (pathos)

- Leans on experts in their fields to cultivate credibility (ethos)

- Enlists or elicits a call to action (kairos)

- Presents and acknowledges opposing views

Contents within this Chapter:

- Elements of an Argument Essay

- Aristotelian (Classical) Argument Model

- Rogerian Argument Model

- Toulmin Argument Model

- Proposal Argument Model

- Counterargument and Response

- Generating Antithetical Points in Five Easy Steps

- Tips for Writing Argument Essays

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Argumentative Writing Copyright © 2020 by Joel Gladd and Amy Minervini is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

3 Key Tips for How to Write an Argumentative Essay

General Education

If there’s one writing skill you need to have in your toolkit for standardized tests, AP exams, and college-level writing, it’s the ability to make a persuasive argument. Effectively arguing for a position on a topic or issue isn’t just for the debate team— it’s for anyone who wants to ace the essay portion of an exam or make As in college courses.

To give you everything you need to know about how to write an argumentative essay , we’re going to answer the following questions for you:

- What is an argumentative essay?

- How should an argumentative essay be structured?

- How do I write a strong argument?

- What’s an example of a strong argumentative essay?

- What are the top takeaways for writing argumentative papers?

By the end of this article, you’ll be prepped and ready to write a great argumentative essay yourself!

Now, let’s break this down.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents the writer’s position or stance on a specific topic and uses evidence to support that position. The goal of an argumentative essay is to convince your reader that your position is logical, ethical, and, ultimately, right . In argumentative essays, writers accomplish this by writing:

- A clear, persuasive thesis statement in the introduction paragraph

- Body paragraphs that use evidence and explanations to support the thesis statement

- A paragraph addressing opposing positions on the topic—when appropriate

- A conclusion that gives the audience something meaningful to think about.

Introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion: these are the main sections of an argumentative essay. Those probably sound familiar. Where does arguing come into all of this, though? It’s not like you’re having a shouting match with your little brother across the dinner table. You’re just writing words down on a page!

...or are you? Even though writing papers can feel like a lonely process, one of the most important things you can do to be successful in argumentative writing is to think about your argument as participating in a larger conversation . For one thing, you’re going to be responding to the ideas of others as you write your argument. And when you’re done writing, someone—a teacher, a professor, or exam scorer—is going to be reading and evaluating your argument.

If you want to make a strong argument on any topic, you have to get informed about what’s already been said on that topic . That includes researching the different views and positions, figuring out what evidence has been produced, and learning the history of the topic. That means—you guessed it!—argumentative essays almost always require you to incorporate outside sources into your writing.

What Makes Argumentative Essays Unique?

Argumentative essays are different from other types of essays for one main reason: in an argumentative essay, you decide what the argument will be . Some types of essays, like summaries or syntheses, don’t want you to show your stance on the topic—they want you to remain unbiased and neutral.

In argumentative essays, you’re presenting your point of view as the writer and, sometimes, choosing the topic you’ll be arguing about. You just want to make sure that that point of view comes across as informed, well-reasoned, and persuasive.

Another thing about argumentative essays: they’re often longer than other types of essays. Why, you ask? Because it takes time to develop an effective argument. If your argument is going to be persuasive to readers, you have to address multiple points that support your argument, acknowledge counterpoints, and provide enough evidence and explanations to convince your reader that your points are valid.

Our 3 Best Tips for Picking a Great Argumentative Topic

The first step to writing an argumentative essay deciding what to write about! Choosing a topic for your argumentative essay might seem daunting, though. It can feel like you could make an argument about anything under the sun. For example, you could write an argumentative essay about how cats are way cooler than dogs, right?

It’s not quite that simple . Here are some strategies for choosing a topic that serves as a solid foundation for a strong argument.

Choose a Topic That Can Be Supported With Evidence

First, you want to make sure the topic you choose allows you to make a claim that can be supported by evidence that’s considered credible and appropriate for the subject matter ...and, unfortunately, your personal opinions or that Buzzfeed quiz you took last week don’t quite make the cut.

Some topics—like whether cats or dogs are cooler—can generate heated arguments, but at the end of the day, any argument you make on that topic is just going to be a matter of opinion. You have to pick a topic that allows you to take a position that can be supported by actual, researched evidence.

(Quick note: you could write an argumentative paper over the general idea that dogs are better than cats—or visa versa!—if you’re a) more specific and b) choose an idea that has some scientific research behind it. For example, a strong argumentative topic could be proving that dogs make better assistance animals than cats do.)

You also don’t want to make an argument about a topic that’s already a proven fact, like that drinking water is good for you. While some people might dislike the taste of water, there is an overwhelming body of evidence that proves—beyond the shadow of a doubt—that drinking water is a key part of good health.

To avoid choosing a topic that’s either unprovable or already proven, try brainstorming some issues that have recently been discussed in the news, that you’ve seen people debating on social media, or that affect your local community. If you explore those outlets for potential topics, you’ll likely stumble upon something that piques your audience’s interest as well.

Choose a Topic That You Find Interesting

Topics that have local, national, or global relevance often also resonate with us on a personal level. Consider choosing a topic that holds a connection between something you know or care about and something that is relevant to the rest of society. These don’t have to be super serious issues, but they should be topics that are timely and significant.

For example, if you are a huge football fan, a great argumentative topic for you might be arguing whether football leagues need to do more to prevent concussions . Is this as “important” an issue as climate change? No, but it’s still a timely topic that affects many people. And not only is this a great argumentative topic: you also get to write about one of your passions! Ultimately, if you’re working with a topic you enjoy, you’ll have more to say—and probably write a better essay .

Choose a Topic That Doesn’t Get You Too Heated

Another word of caution on choosing a topic for an argumentative paper: while it can be effective to choose a topic that matters to you personally, you also want to make sure you’re choosing a topic that you can keep your cool over. You’ve got to be able to stay unemotional, interpret the evidence persuasively, and, when appropriate, discuss opposing points of view without getting too salty.

In some situations, choosing a topic for your argumentative paper won’t be an issue at all: the test or exam will choose it for you . In that case, you’ve got to do the best you can with what you’re given.

In the next sections, we’re going to break down how to write any argumentative essay —regardless of whether you get to choose your own topic or have one assigned to you! Our expert tips and tricks will make sure that you’re knocking your paper out of the park.

The Thesis: The Argumentative Essay’s Backbone

You’ve chosen a topic or, more likely, read the exam question telling you to defend, challenge, or qualify a claim on an assigned topic. What do you do now?

You establish your position on the topic by writing a killer thesis statement ! The thesis statement, sometimes just called “the thesis,” is the backbone of your argument, the north star that keeps you oriented as you develop your main points, the—well, you get the idea.

In more concrete terms, a thesis statement conveys your point of view on your topic, usually in one sentence toward the end of your introduction paragraph . It’s very important that you state your point of view in your thesis statement in an argumentative way—in other words, it should state a point of view that is debatable.

And since your thesis statement is going to present your argument on the topic, it’s the thing that you’ll spend the rest of your argumentative paper defending. That’s where persuasion comes in. Your thesis statement tells your reader what your argument is, then the rest of your essay shows and explains why your argument is logical.

Why does an argumentative essay need a thesis, though? Well, the thesis statement—the sentence with your main claim—is actually the entire point of an argumentative essay. If you don’t clearly state an arguable claim at the beginning of your paper, then it’s not an argumentative essay. No thesis statement = no argumentative essay. Got it?

Other types of essays that you’re familiar with might simply use a thesis statement to forecast what the rest of the essay is going to discuss or to communicate what the topic is. That’s not the case here. If your thesis statement doesn’t make a claim or establish your position, you’ll need to go back to the drawing board.

Example Thesis Statements

Here are a couple of examples of thesis statements that aren’t argumentative and thesis statements that are argumentative

The sky is blue.

The thesis statement above conveys a fact, not a claim, so it’s not argumentative.

To keep the sky blue, governments must pass clean air legislation and regulate emissions.

The second example states a position on a topic. What’s the topic in that second sentence? The best way to keep the sky blue. And what position is being conveyed? That the best way to keep the sky blue is by passing clean air legislation and regulating emissions.

Some people would probably respond to that thesis statement with gusto: “No! Governments should not pass clean air legislation and regulate emissions! That infringes on my right to pollute the earth!” And there you have it: a thesis statement that presents a clear, debatable position on a topic.

Here’s one more set of thesis statement examples, just to throw in a little variety:

Spirituality and otherworldliness characterize A$AP Rocky’s portrayals of urban life and the American Dream in his rap songs and music videos.

The statement above is another example that isn’t argumentative, but you could write a really interesting analytical essay with that thesis statement. Long live A$AP! Now here’s another one that is argumentative:

To give students an understanding of the role of the American Dream in contemporary life, teachers should incorporate pop culture, like the music of A$AP Rocky, into their lessons and curriculum.

The argument in this one? Teachers should incorporate more relevant pop culture texts into their curriculum.

This thesis statement also gives a specific reason for making the argument above: To give students an understanding of the role of the American Dream in contemporary life. If you can let your reader know why you’re making your argument in your thesis statement, it will help them understand your argument better.

An actual image of you killing your argumentative essay prompts after reading this article!

Breaking Down the Sections of An Argumentative Essay

Now that you know how to pick a topic for an argumentative essay and how to make a strong claim on your topic in a thesis statement, you’re ready to think about writing the other sections of an argumentative essay. These are the parts that will flesh out your argument and support the claim you made in your thesis statement.

Like other types of essays, argumentative essays typically have three main sections: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. Within those sections, there are some key elements that a reader—and especially an exam scorer or professor—is always going to expect you to include.

Let’s look at a quick outline of those three sections with their essential pieces here:

- Introduction paragraph with a thesis statement (which we just talked about)

- Support Point #1 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary (AKA, the fun part!)

- Support Point #2 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #3 with evidence

- New paragraph addressing opposing viewpoints (more on this later!)

- Concluding paragraph

Now, there are some key concepts in those sections that you’ve got to understand if you’re going to master how to write an argumentative essay. To make the most of the body section, you have to know how to support your claim (your thesis statement), what evidence and explanations are and when you should use them, and how and when to address opposing viewpoints. To finish strong, you’ve got to have a strategy for writing a stellar conclusion.

This probably feels like a big deal! The body and conclusion make up most of the essay, right? Let’s get down to it, then.

How to Write a Strong Argument

Once you have your topic and thesis, you’re ready for the hard part: actually writing your argument. If you make strategic choices—like the ones we’re about to talk about—writing a strong argumentative essay won’t feel so difficult.