Unemployment during the pandemic: How to avoid going for broke

Key takeaways.

- Without significant policy changes, employers will be hit with hefty tax increases to pay for mounting unemployment insurance (UI) claims.

- Thinning tax bases make financing UI more challenging.

- Having state UI trust funds in the red may make it much harder for job markets to recover.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in late February, tens of millions of Americans have lost their jobs. Anxiety among many employers and consumers is still high — suggesting little hope of a rapid recovery.

This leaves state and local governments with gaping budget shortfalls amid falling income and sales tax revenues while demand for public services rises. A particularly fast-growing area of state expenditure is the payment of unemployment insurance (UI) benefits.

There has been extensive discussion among policymakers and the media regarding the trade-offs of more generous or longer-lasting UI benefits, such as the federal government’s provision of an additional $600 per week that expired July 31. But there has been very little talk about the tax hikes they will incur.

Many states have depleted their UI trust funds in the current crisis and have started to borrow from the federal government to pay their residents’ UI benefits. In the absence of additional policy changes, employers will be hit with significant UI tax increases over the next few years. And that will likely prevent some of the jobs that were lost from coming back.

In this policy brief, we explain how state unemployment insurance programs are financed and the threats to their solvency. We also discuss two reforms: one to relieve employers faced with crippling payroll tax increases in the coming years, and another to ensure that state UI trusts have enough money for future payouts.

Understanding unemployment insurance

Unemployment insurance is one of the largest social insurance programs in the United States, with each state running its own UI program to pay benefits to people laid off from their jobs. In most states, UI replaces about half of a worker’s earnings up to a weekly benefit maximum ($443 in the median state) for a maximum of 26 weeks (6 months).

While providing a needed cushion to workers, UI leaves policymakers with a difficult balancing act. As benefits become more generous, many recipients reduce their efforts to find and maintain jobs, reducing total income and burdening other workers (Johnston and Mas 2018). But if benefits become stingier, the cushion provides less support leaving some unemployed vulnerable to fall behind on their bills or lose their housing (Ganong and Noel 2019). [1]

Benefits are generally paid to people with relatively low saving rates, so the money that is distributed is quickly spent, providing short-term stimulus for consumer goods. This leads economists to refer to UI as an “automatic stabilizer.” Without the need for additional legislation, states automatically spend more money on unemployment benefits when economic conditions deteriorate, and spending naturally retracts as the economy recovers.

During the strong labor market leading up to the pandemic, just 220,000 workers filed new UI claims in the typical week. In late February, the unemployment rate was at 3.5 percent — a 60-year low — and about 1.7 million Americans were receiving UI benefits.

But two months later, the pandemic’s sudden and massive shock to the economy vaulted the U.S. unemployment rate to 14.7 percent — an 80-year-high. This April, rates varied substantially across states, from a high of 28.2 percent in Nevada to a low of 8.3 percent in Nebraska.

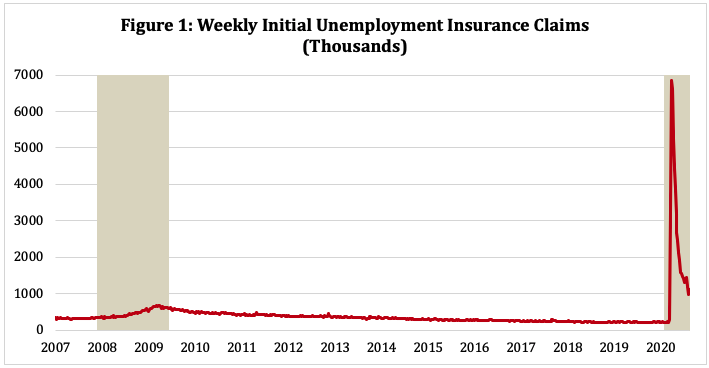

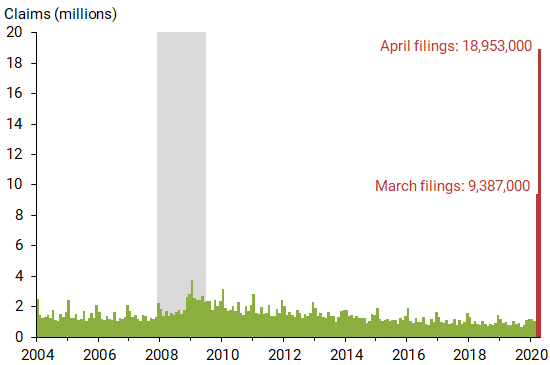

During the last week of March, 6.9 million Americans filed new claims for UI benefits. As demonstrated in Figure 1, this was 10 times higher than the corresponding peak in new UI claims during the depths of the Great Recession more than a decade ago. By early May of this year, more than 25 million Americans were receiving UI payments and in every week since early March, new UI claims have exceeded the Great Recession peak of 660,000.

Figure 1: Weekly Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims (Thousands)

From March through the end of July, the federal CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act increased unemployment benefits for each recipient by $600 per week. That meant the average UI recipient was paid one-third more in unemployment than she earned while working (Ganong et al. 2020).

This raised concerns that workers had little incentive to return to work or find a new job, a condition necessary for labor market restructuring and recovery. [2] This additional UI funding expired at the end of July after lawmakers were unable to agree on another round of federal spending. President Trump attempted to provide a $300-dollar weekly “top-up” by executive order (with states given the option to provide an additional $100). Whether and when that happens is unclear given that states have to apply for the funding. [3]

UI benefits are financed by a payroll tax on employers. Unlike other taxes, UI tax rates are “experience-rated,” which means that an employer’s future tax rate rises if its employees claim UI benefits, and its tax rate falls when the firm avoids layoffs. This gives employers a strong incentive to balance the demand for layoffs with the cost that they impose on the UI system.

One consequence of experience-rating UI taxes is that tax rates increase as the economy begins to recover from recession. This significantly raises the cost of hiring new workers or retaining old ones, likely weighing down recovery of the labor market.

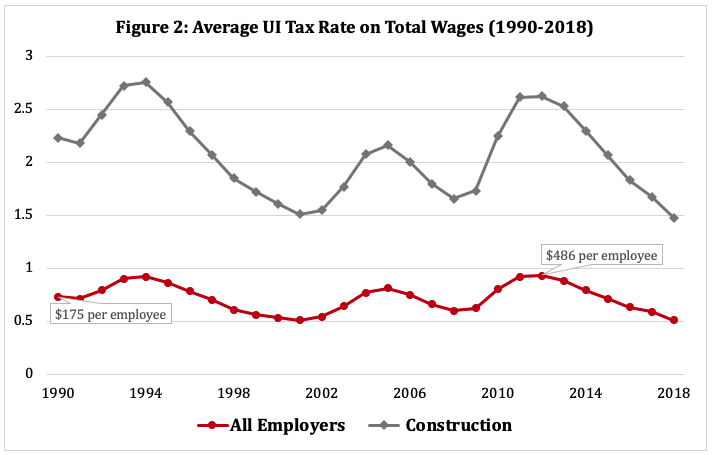

As shown in Figure 2, the average UI tax rate increased by more than 50 percent from 2009 to 2012 as the recovery was haltingly underway. This increase was especially high in middle-class industries — like construction and manufacturing — that were hit hardest during the Great Recession. As this same figure shows, average tax rates were more than 2.5 times as high among employers in construction as among all employers in the years following the three most recent recessions.

Figure 2: Average UI Tax Rate on Total Wages (1990-2018)

Surviving firms have to cover the UI costs generated by the employers that went out of business — causing them to be doubly burdened. Given the much larger increase in UI claims during the current recession relative to previous ones and the likely greater rate of firm exit, the increase in UI taxes could be substantially higher over the next few years than in the years following the Great Recession. This will encourage outsourcing and automation, induce some firms to shut down, and impede employment.

Softening the blow to businesses

Unless employment recovers with impressive speed, each claim will draw an average of $7,000 in payments from state UI trust funds. Those payments will transform into an estimated $270 billion dollars in payroll tax increases on firms over the next few years, reducing the ability of firms to resume normal hiring and employment and further stalling a labor market comeback. [4]

In March and April of this year, 20 states suspended experience rating to shield their employers from an avalanche of additional UI taxes in the upcoming years. These states span the political spectrum as well as geography, including Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Ohio, Texas, and Washington. [5]

While this policy change will — all else equal — hasten the labor market recovery in these states, it may also lead to a substantial increase in layoffs since it removes firms’ financial incentives to retain workers. Consistent with this, a comparison of five states that suspended experience rating with five neighboring states that did not reveals that layoff rates (defined as new UI claims divided by the workforce) were 30 percent higher in the five that shut down experience rating. [6]

States are therefore in a bind. By maintaining experience rating, a wave of future tax increases may hamper the economic recovery and prolong unemployment. But suspending experience rating may induce additional layoffs today, when things are most dire.

To soften the blow over the next few years while maintaining the incentives for employers to retain their workforce, states could adjust each company’s UI costs so that they are temporarily evaluated based on conditions in their industry — reducing the scope for tax increases that were out of the firm’s control.

For the next few years, employers would essentially be graded on a curve, comparing their layoff history with industry peers rather than a non-existent perfect firm. For example, since restaurants have been hit especially hard during the pandemic while the average technology firm has thrived, a restaurant that laid off 10 percent of its workers would face a smaller tax increase than a computer software company that did the same. Employers would have essentially equal incentives to maintain their workforce, but would not face crushing tax increases if they happen to be in an industry that was differentially hit by the COVID pandemic and the resulting lockdowns.

The benefits of such a policy could be substantial. Research suggests that employment is highly sensitive to UI tax increases in part because they hit firms that are already on the proverbial ropes. Anderson and Meyer (1997) find that a 1 percent increase in costs from UI taxes reduces employment by 2 percent. More recent research by Johnston (2020) finds even larger effects.

Shoring up the trust funds

The pandemic has shed light on the vulnerability of UI financing. Better maintenance of UI trust funds is vital to prepare states for the next economic downturn and improve prospects for future recoveries.

There is a large and growing gap in UI tax costs across jurisdictions. States like California and Florida have a low maximum tax rate and an annual tax base of around $7,000 — the lowest allowed by federal law — resulting in maximum potential UI taxes of about $400 per worker. In contrast, states like Washington and Oregon maintain large tax bases ($52,700 and $42,100, respectively) resulting in potential UI taxes of more than $2,000 per worker. [7]

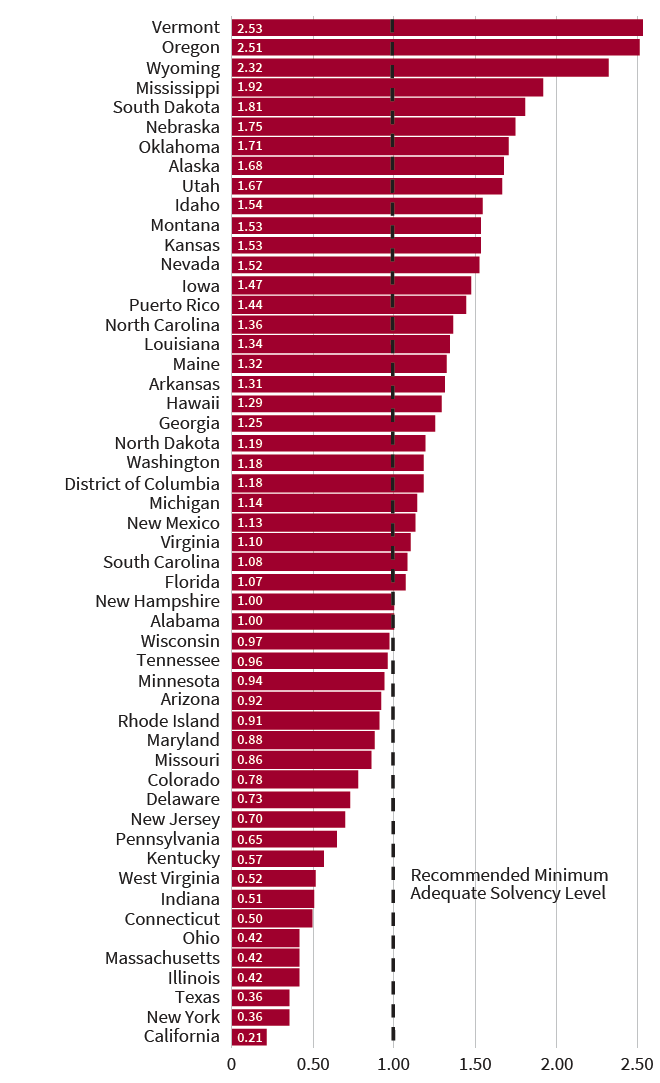

In good times, states store revenues from UI taxes in a trust fund and that fund is drawn down in the depth of recessions. In recent years, however, state trust funds have been low even in good times — a function of benefits that are more generous than their financing (von Wachter 2016). The Department of Labor’s 2020 Solvency Report shows that despite a 10-year economic expansion, 21 state UI trust funds were below the minimum recommended reserve, just prior to the pandemic (U.S. Department of Labor 2020). [8] As of August 2020, 11 states have already depleted their UI trust funds and have started to receive loans from the federal government to pay UI benefits. [9]

These deficits may contribute to lethargic recoveries. When trust funds are low, states must steeply raise rates to recover their costs and pay benefits. The timing of these increases could not be worse. Weak trust funds also undermine experience rating. When a state trust fund is in debt to the federal government, federal UI taxes rise on all firms in that state until the federal loan is repaid, regardless of the firm’s layoffs.

In California, for instance, the large loan balance accrued during the 2008 recession was not repaid in full until 2018, hiking payroll taxes for employers across the board. This weakens the intended incentives of experience rating to encourage employment stability and curb abuse of the UI system. According to the same Labor Department Solvency Report cited above, California’s UI trust fund was in the worst position of all 50 states just prior to the pandemic (Appendix Figure 1). [10]

The thinning tax base is a leading cause of low UI reserves. States choose how much of a worker’s earnings are exposed to UI taxation, but the federal government can “update” the minimum requirement to keep pace with inflation and the rise in average earnings. The current federal requirement of $7,000 has —remarkably — not been updated since 1982, eroding the tax base unless states have legislated increases or proactively linked their taxable UI earnings base to inflation or wage growth.

Another important consequence of a small tax base is that UI taxes become much more regressive. This can reduce the employment opportunities for part-time workers or those with low earnings since firms essentially pay an equal tax for each worker (Guo and Johnston 2020). In a state like California, an employer would pay the same UI tax for a worker who earned $8,000 annually as for one who earned $40,000.

But the latter worker is eligible for a weekly UI benefit that is five times larger ($400 per week versus just $80 per week for the lower-paid worker). Expanding the UI program’s taxable wage base in states like California would reduce the implicit penalty on hiring low-wage earners (principally seasonal and part-time workers as well as students).

To restore the health of UI trust funds, governments should expand their tax bases to be proportional to the level of benefits in their state. A basic reform to shore up trust funds could be to require states to have taxable wage bases at least half as large as their annual insurable earnings.

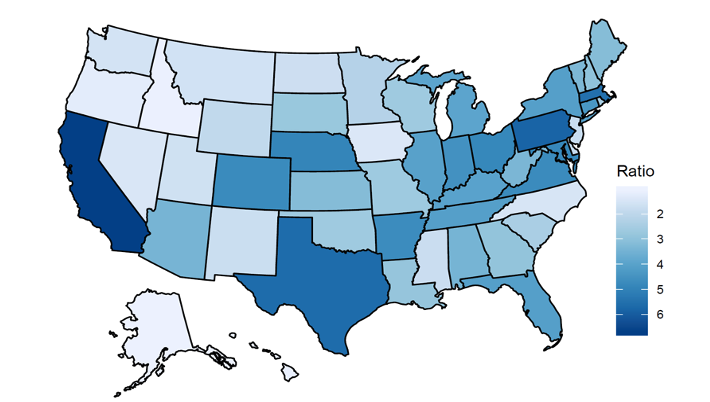

Figure 3 plots the ratio of insured wages to taxable wages across the country, with larger values indicating greater insurance than funding.

Figure 3: Ratio of Annual Insured Wages to Taxable Wages (2015)

In California the UI-insurable income is $47,000, more than six times greater than the tax base of only $7,000. This reform would naturally link revenues to the generosity of the state’s UI system, allow states to lower tax rates, and bring in sufficient revenues to cushion workers the next time there is an economic shock. Harmonizing tax bases across states would also reduce the incentive for multi-state firms to reallocate jobs and operations based on state UI tax differences (Guo 2020).

Time for action

The COVID-19 crisis has put unemployment insurance at center stage of American politics and economic policy. It has provided a lifeline for tens of millions of workers who have lost their jobs since the pandemic’s onset six months ago, while at the same time exposing the system’s vulnerabilities. Given the complexity of UI financing and the scarcity of empirical evidence on which to rely, this is an important area for additional work and exploration.

Unless policymakers take steps to reform how the states’ unemployment insurance trust funds are financed, tax hikes will hurt labor market recoveries across the country — and with them, the American worker.

Mark Duggan is the Trione Director of SIEPR and the Wayne and Jodi Cooperman Professor of Economics at Stanford. Audrey Guo is an assistant professor of economics at Santa Clara University’s Leavey School of Business. Andrew C. Johnston is an assistant professor of economics, as well as applied econometrics at the University of California at Merced.

The authors are grateful to Isaac Sorkin for his helpful feedback.

1 States differ in where they choose to fall on that trade-off. The maximum weekly benefit varies substantially across states, from a low of $235 in Mississippi to a high of $790 in Washington. Some states also have a maximum duration of less than 26 weeks.

2 Recent research suggests that, at least in the short term, the disincentive effects of the increases in UI benefits (caused by the CARES Act) were minimal (Altonji et al. 2020).

3 More than half of states had applied or signaled their intention to apply as of August 21. Only South Dakota announced that it would not be applying (Iacurci 2020). States that are approved are guaranteed just three weeks of federal funding for the enhanced UI benefits, though more federal funding may be available.

4 For this calculation, we extrapolate weekly UI claims through the end of the year and assume that half of those claims become benefit spells. We use data on average weekly benefit amounts and average UI spell durations to calculate the typical cost of a UI benefit spell at a little over $7,000. The product of these two values is an estimate of the UI benefit costs that will factor into UI taxes over the coming years. The actual average value could be substantially higher if the recovery is slow, as this would lead to longer and more costly average UI benefit periods.

5 These 20 states are Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Washington, and the District of Columbia.

6 The matched pairs are — with the states that suspended experience rating listed first — Alabama and Mississippi, Ohio and Indiana, North Dakota and South Dakota, Arizona and New Mexico, and Idaho and Oregon.

7 Appendix Table 1 lists the UI tax base in each state in 2020 along with each state’s maximum per-worker tax and maximum weekly UI benefit.

8 The Department of Labor recommends that states have reserves in their trust funds that are at least as large as the highest recent years of UI benefit payout.

9 As of August 25, 2020, 11 states have borrowed $24.4 billion from the federal unemployment account. California, New York, and Texas account for 82% of that borrowing .

10 As shown in Appendix Figure 1, California’s solvency ratio of 0.21 was lower than the other 49 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Altonji, Joseph, Zara Contractor, Lucas Finamor, Ryan Haygood, Ilse Lindenlaub, Costas Meghir, Cormac O’Dea, Dana Scott, Liana Wang, and Ebonya Washington. “Employment Effects of Unemployment Insurance Generosity during the Pandemic.” Working Paper (2020).

Anderson, Patricia M., and Bruce D. Meyer. "The effects of firm specific taxes and government mandates with an application to the U.S. unemployment insurance program." Journal of Public Economics 65, no. 2 (1997): 119-145.

Ganong, Peter, and Pascal Noel. "Consumer spending during unemployment: Positive and normative implications." American Economic Review 109, no. 7 (2019): 2383-2424.

Ganong, Peter, Pascal Noel, and Joseph S. Vavra. U.S. Unemployment Insurance Replacement Rates During the Pandemic , no. w27216. National Bureau of Economic Research (2020).

Guo, Audrey. "The effects of unemployment insurance taxation on multi-establishment firms." Working Paper (2020).

Guo, Audrey, and Andrew C. Johnston. "The Finance of Unemployment Compensation and its Consequence for the Labor Market." Working Paper (2020).

Iacurci, Greg. “ This Map Shows Where States Stand on the Extra $300 Weekly Unemployment Benefits. ” CNBC, August 21, 2020.

Johnston, Andrew C. “Unemployment Insurance Taxes and Labor Demand: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Administrative Data.” Forthcoming at American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (2020).

Johnston, Andrew C., and Alexandre Mas. "Potential unemployment insurance duration and labor supply: The individual and market-level response to a benefit cut." Journal of Political Economy 126, no. 6 (2018): 2480-2522.

U.S. Department of Labor. State Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Solvency Report 2020. February 2020.

Von Wachter, Till. “ Unemployment Insurance Reform: A Primer. ” Washington Center for Equitable Growth. October 2016.

Appendix Table A

Source: US Dept of Labor Significant Provisions of State Unemployment Insurance Laws 2019

*For single workers. Some states offer additional dependent allowances

Appendix Figure 1 - State UI Trust Fund Solvency (as of 1/1/2020)

Source: U.S. Department of Labor Trust Fund Solvency Report 2020

Related Topics

- Policy Brief

More Publications

Increasing wireless value: technology, spectrum, and incentives, careful what you wish for: the shale gas revolution and natural gas exports, estimating equilibrium in health insurance exchanges: analysis of the californian market under the aca.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Covid-19, unemployment...

Covid-19, unemployment, and health: time for deeper solutions?

Read our latest coverage of the coronavirus outbreak.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Martin Hensher , associate professor of health systems financing and organisation 1 2

- 1 Deakin Health Economics, Deakin University, 221 Burwood Highway, Burwood, VIC 3125, Australia

- 2 Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania

- Correspondence to: martin.hensher{at}deakin.edu.au

As covid-19 drives unemployment rates around the world to levels unseen in generations, once radical economic policy proposals are rapidly gaining a hearing. Martin Hensher examines how job guarantee or universal basic income schemes might support better health and better economics

Covid-19 has been a dramatic global health and economic shock. As SARS-CoV-2 spread across nations, economic activity plummeted, first as individuals changed their behaviour and then as government “lockdowns” took effect. 1 Macroeconomic forecasters foresee a major recession continuing through 2020 and into 2021. 2 Although the governments of many nations have taken novel steps to protect workers, unemployment has risen dramatically in many countries ( box 1 , fig 1 ); poverty and hunger are on the rise in low and middle income countries. 5 Covid-19 has directly caused illness and death at a large scale, and further threatens health through disruption of access to health services for other conditions.

Covid-19 and unemployment

Although unemployment soared in response to covid-19 in some nations, the policy measures undertaken by others have prevented many workers from becoming technically unemployed. In the United Kingdom, the headline rate of unemployment for April-June 2020 was 3.9%—only slightly higher than the 3.89% rate in April-June 2019. Yet in June 2020 9.3 million people were in the coronavirus job retention scheme (“furlough”) and another 2.7 million had claimed a self-employment income support scheme grant; there had been the largest ever decrease in weekly hours worked; 650 000 fewer workers were reported on payrolls in June than in March; and the benefit claimant count had more than doubled from 1.24 million to 2.63 million people. 3 The Australian Bureau of Statistics has produced an adjusted estimate of Australian unemployment that includes all those temporarily stood down or laid off, to allow a closer comparison with US and Canadian statistics ( fig 1 ). As emergency support measures are wound back, concern is growing that the downwards trend from the April peak might not be maintained in coming months.

Unemployment rates in Australia, Canada, and the United States from March to July 2020. 4

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The pandemic continues to spread, and hopes for a rapid “return to normal” look increasingly unfounded. The economic consequences of covid-19 have the potential to further damage human health if not managed effectively—even after the pandemic has faded. Even with the most rose tinted views of recovery, the effects of covid-19 on unemployment are likely to be substantial and long lived. Ambitious responses to the imminent scourge of mass unemployment are being discussed. Two such proposals—a job guarantee and universal basic income—might protect and promote health as well as prosperity. Governments around the world should consider radical plans to safeguard their citizens’ livelihoods and wellbeing.

Unemployment and health in the time of covid-19

Decades of accumulated evidence show a strong and consistent association between unemployment and a range of adverse health outcomes, including all cause mortality, death from cardiovascular disease and suicide, and higher rates of mental distress, substance abuse, depression, and anxiety. 6 7 8 Job insecurity is similarly associated with poorer self-assessed health status, mental distress, depression, and anxiety. 9 Unemployment and economic adversity are intimately related with despair and lack of hope, which have increasingly been linked with mortality and the rise and severity of the US opioid epidemic. 10 11 Whether recessions and mass unemployment increase aggregate mortality is less clear; historical studies indicated improvements in mortality during the Great Depression in the 1930s, 7 but more recent US research found that older workers (aged 45-66) who lose their jobs in a recession have higher mortality than those who lose their jobs in boom times. 12 Insecurity, precariousness, and austerity harmed both unemployed and employed people during the protracted economic crisis in Greece after 2008-09. 13 Meanwhile, differing welfare state institutions and unemployment insurance arrangements directly limit or amplify health inequalities in a society. 7 14

These factors could adversely affect the health of growing numbers of unemployed workers after covid-19. 15 16 Governments, business lobbyists, and civil society advocates around the world are debating how economies might best recover from the covid recession. Although governments currently acknowledge the need to spend freely during the crisis, experience suggests that pressure to pursue misguided austerity policies might grow, threatening subsequent recovery. Options on the table range from “green new deal” programmes to build a post-carbon economy and national industrial strategies to bring globalised manufacturing back onshore through to calls for reducing wages and labour protections to “free up” labour markets. Yet these are all indirect approaches to the effects of unemployment. Proposals for a job guarantee or a universal basic income seek to act more directly to support individual citizens.

The job guarantee

The idea of a right to employment can be traced back to the US New Deal in the 1930s, and to Article 23 of the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. More recently, in the contest for the Democratic Party’s 2020 candidate for US president, senators Bernie Sanders, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Cory Booker all included a job guarantee in their platforms, as did Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s green new deal resolution. More than one detailed proposal for a Federal Job Guarantee has been published in the US 17 18 and in Australia. 19 In one US proposal, 18 a federally funded public service employment programme would provide a standing offer of work at a living wage ($15 (£12; €13) an hour), along with key benefits including healthcare coverage. Employees of this programme would be deployed on a wide range of public works and community development activities, delivered through federal, state, local, and non-profit agencies. The proposal argues that this would effectively eliminate unwanted joblessness and underemployment and would rapidly force the private sector to increase wages to match this “living wage” alternative, lifting millions out of poverty and greatly improving the incomes of working poor people. 18 Proponents argue that the job guarantee is the most efficient “automatic stabiliser” for the economy throughout the business cycle, able to adjust up and down to reflect the changing economic health of the private sector. In economic downturns, it would provide guaranteed employment to stop people falling into poverty and losing “employability,” while also supporting aggregate demand to lift the economy out of recession. In boom times, workers will simply exit the programme for the private sector, as firms offer higher wages to secure the additional labour they need.

In the US, the job guarantee has been proposed as not only a key tool for recovery from covid-19, 20 but also a mechanism to ensure that this recovery breaks down historically entrenched racial inequalities in wealth. 21 Similarly, an emerging job guarantee proposal for Australia could rectify decades of welfare policy failures that have disproportionately affected indigenous Australians. 22 Proponents point to successful past or present international experiences with full or targeted employment guarantee programmes, including Argentina’s Plan Jefes, South Africa’s Expanded Public Works Programme, India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, Belgium’s Youth Job Guarantee, the US Youth Incentive Entitlement Pilot Projects, and the UK’s Future Jobs Fund. 20

Universal basic income

Over the past few years, there has been a global explosion of interest in the concept of universal basic income. 23 24 25 Andrew Yang, another former contender for the 2020 Democrat presidential nomination, made universal basic income a central plank of his platform. Such proposals share key characteristics: they are a transfer of income (from the state to individuals) that is provided universally (to everyone, with no targeting), unconditionally (with no requirements, for example to work), and in cash (with no controls on what the money can be spent on). 25 Proposals also typically specify an income that is sufficiently generous that it can fully cover a basic level of living expenses. 23 Universal basic income is a direct means of reducing poverty, by ensuring that all in society receive enough to live with dignity; it could reduce income inequality; it could radically simplify current social welfare systems and remove poverty traps and disincentives to move from welfare into work; it could improve the ability of workers to refuse poorly paid, insecure, exploitative or unsafe jobs, through a reduced fear of loss of income; and it could be a buffer against technological unemployment, as automation and artificial intelligence replace human labour. 23 25 Universality is the key difference from today’s welfare systems; everyone should receive universal basic income as a right of citizenship, and its receipt by all should build the solidarity and legitimacy that will sustain this right. Universal basic income could improve health and reduce health inequities through direct action on various social determinants of health. 26 27 This variety of aims leads to the concept being simultaneously supported by those on the left as a radical, anti-capitalist policy, often viewed as an essential component of the ecological degrowth agenda, and by libertarian, tech capitalists as an efficient solution to the risk that ever expanding digital automation will destroy more jobs than it creates, and as a vital measure to help capitalism survive mass technological unemployment in the future. 28

In the wake of the covid-19 economic shock, universal basic income has been discussed as a potentially powerful policy solution to unprecedented economic dislocation. It has specifically been suggested as a tool for limiting the economic, social, and psychological trauma of covid-19. 29 The Spanish government has just introduced a nationwide, means tested minimum income programme (not universal) as a direct response to covid related unemployment. 30 The US government has made unconditional, one-off economic impact payments to most (but not all) American households. Near universal and unconditional universal basic income programmes have only operated at nationwide scale in two countries, Mongolia and Iran. The Mongolian programme has since ceased, and the Iranian programme is no longer strictly universal (the richest people are no longer eligible). Partial schemes and regional pilots, however, have been run successfully in a wide range of nations. 25 A recent trial that provided universal basic income to 2000 recipients in Finland found that employment outcomes, health, and wellbeing measures were better in the universal basic income group than in the comparison group, 31 and the Scottish government has been contemplating a three year trial of universal basic income in an experimental group of recipients. 32

Potential health benefits

Given the substantial evidence linking unemployment to poor health, proponents of both job guarantee and universal basic income schemes point to their potential health benefits as major arguments in their favour ( table 1 ). 20 26 These measures could be expected to positively affect health through four main pathways: direct effects for individual beneficiaries; knock-on effects improving labour market conditions for all workers; the macroeconomic and distributive benefits of more widespread prosperity; and more localised community effects unlocked by these programmes.

Health effects of job guarantee (JG) and universal basic income (UBI) programmes

- View inline

Multiple mechanisms would work through these four pathways to deliver potential health benefits, including reduced mortality and improved physical and mental health status. Key mechanisms include reducing poverty, improving economic security, improving the quality of jobs and work, and rebuilding stronger local communities. Unsurprisingly, pathways that link unemployment with poorer health will be more reliably affected by job guarantee programmes than by universal basic income. But universal basic income offers alternative pathways for better health through informal caring and non-market activities. Both types of programme could help resolve one of the problems that the covid-19 pandemic has brought into sharp focus—that low paid, insecure, and casualised workforces cannot afford to self-isolate or stay at home when sick or potentially infected because they lack access to paid sick leave. This problem has proved especially disastrous for those who care for elderly people.

Controversies and choices

Supporters of job guarantee or universal basic income programmes typically have different priorities and view them as two alternative options, not as complementary programmes that could co-exist. Most job guarantee proposals see it as not only a means to fight unemployment, but also an explicit instrument of macroeconomic policy 38 ; universal basic income would not function as an “automatic stabiliser” in the same way. Critics of job guarantee and universal basic income schemes primarily question their affordability and potential macroeconomic consequences ( box 2 ).

Economic controversies

Implementing a job guarantee or universal basic income programme would be a major economic reform in any nation and a decisive break with the economic orthodoxy that has prevailed since the Thatcher-Reagan revolution of the 1980s. It would undoubtedly be controversial. Most obviously, some would question them on cost and affordability grounds. A job guarantee programme would incur a substantial net cost to governments—modelling of proposed programmes indicates a net cost to the federal budget equivalent to 1.5% of annual general domestic product (GDP) in the US 18 and 2.6% in Australia (based on a net budgetary cost of A$51.7bn). 19 By comparison, the Australian government is spending A$70bn, or 3.6% of its GDP, on its emergency JobKeeper employment protection programme this year—budget costs of these magnitudes are not unheard of. The gross costs of a universal basic income programme would be substantially larger: income of $12 000 (close to the 2017 US poverty line) for every US adult would cost the federal budget about $3tn, or nearly 14% of GDP. 23 Yet this gross cost estimate is arguably misleading, 39 not only because universal basic income would be partially offset by large savings from current welfare programmes, but because so many recipients would return much or all of it in the form of tax payments. One estimate of the net cost of such a programme indicates that it could be as low as 2.95% of US GDP. 39 These proposals emerge as a growing number of economists are saying that the governments of countries in possession of their own sovereign currency can never “run out of money” and can always purchase whatever goods and services are for sale in the currency they issue. 38 40 They also suggest that inflation—the other risk often pointed to by critics of job guarantee or universal basic income—is currently highly unlikely, with a general fear that the covid-19 recession will prove to be deflationary rather than inflationary.

For those concerned with health, however, philosophical differences might be of more interest. Social determinants and socioeconomic inequalities are well understood to be powerful forces driving health outcomes at both individual and population levels. Universal basic income seeks to reduce poverty and inequality by putting in place an absolute floor—a minimum income provided to everyone in society. A job guarantee seeks to affect poverty by ensuring that anyone who wants to work can work, for a living wage in a decent job. But in so doing, a job guarantee also explicitly increases the relative power of workers, ensuring that a larger share of national income flows to labour, rather than to the owners of capital—potentially reducing some of the extreme inequalities in income and wealth distribution that have arisen over the past four decades. One criticism of universal basic income is that it might (whether inadvertently or by design) become a “plutocratic, philanthropic” programme 28 —scraps from the table of the ultra wealthy, which might cement dependence and powerlessness in a future of technological unemployment. Equally, a job guarantee might be criticised as being a mid 20th century solution to a 21st century problem, which will reinforce social hierarchies by insisting on participation in paid employment as the solution to poverty.

The unemployment triggered by covid-19 in so many countries is a clear and present danger to individual and population health. Tinkering around the margins of current welfare systems, exhortations for yet more labour market “flexibility,” or an unwillingness to maintain public spending through a potentially long and drawn out downturn all offer a fast track to poor outcomes. The scale of the covid economic shock demands more radical action. The substantial health harms of unemployment might be mitigated by a universal basic income programme, but if unemployment is the problem, then employment seems likely to deliver more effective mitigation along the many and complex pathways by which these harms are transmitted. If so, implementing national job guarantee programmes should be a more urgent priority for governments in the immediate aftermath of covid-19. A successful job guarantee scheme would avert the harms of unemployment, strengthen the position of ordinary working people, and deliver a more broadly distributed prosperity in the short to medium term. This would be a much better position from which to then debate and trial universal basic income, allowing it to be correctly framed as a strategic, long term solution to the changing future of work, rather than simply as a response to the current economic crisis.

Key messages

Covid-19 has triggered economic recession and unprecedented rapid rises in unemployment in many countries

Mass unemployment has the potential to cause grave harm to individual and population health if not effectively mitigated

The scale of the crisis means that radical solutions might need to be considered, such as a job guarantee or universal basic income programmes

These policies have the potential to protect human health and dignity, but would mark a significant break with economic orthodoxy

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation as the traditional owners of the land on which this work was undertaken.

Contributors and sources: MH has worked on health financing, planning, and economics as a senior policy maker and researcher in the UK, South Africa, and Australia and as a consultant for the World Bank, World Health Organization and the European Commission. His research on the ecological and economic sustainability of healthcare systems has included examining a number of emerging heterodox economic approaches, two of which are gaining in significance: ecological economics and modern monetary theory. Members of these schools have promoted universal basic income and a job guarantee, respectively, over many years. This article builds on the existing academic literature to consider very recent policy proposals that are emerging in response to the threat of mass unemployment in the wake of covid-19.

Patient involvement: No patients were involved.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have the following interests to declare: this research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Scholarship.

- ↵ Goolsbee A, Syverson C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w27432

- ↵ International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook update: a crisis like no other, an uncertain recovery. June 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020

- ↵ Office for National Statistics. Labour market overview, UK: August 2020. 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/august2020

- ↵ Australian Bureau Statistics. Understanding unemployment and the loss of work during the covid-19 period: an Australian and international perspective. 13 August 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/understanding-unemployment-and-loss-work-during-covid-19-period-australian-and-international-perspective

- ↵ World Bank. World Bank Group. 100 countries get support in response to covid-19. 19 May 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/05/19/world-bank-group-100-countries-get-support-in-response-to-covid-19-coronavirus

- Stuckler D ,

- von dem Knesebeck O

- Beckfield J

- Beckfield J ,

- Eikemo TA ,

- McNamara C ,

- Kugenthiran N ,

- Collins D ,

- Christensen H ,

- Fullwiler S ,

- Tcherneva P ,

- ↵ Mitchell WF, Watts M. Investing in a job guarantee for Australia. Centre of Full Employment and Equity. July 2020. http://www.fullemployment.net/publications/reports/2020/CofFEE_Research_Report_2000-02.pdf

- Tcherneva P

- Hamilton D ,

- Asanthe-Muhammad D ,

- Collins C ,

- ↵ Pearson N. The case for a government jobs guarantee. The Australian. 4 July 2020. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/the-case-for-a-government-jobs-guarantee/news-story/dee6e9545cd5af967c853e2f0481b02d

- Rothstein J

- Banerjee A ,

- Niehaus P ,

- Gentiline U ,

- Rigolini J ,

- Ruckert A ,

- Fouksman E ,

- Johnson MT ,

- Johnson EA ,

- ↵ Dombey D, Sandbu M. Spain to push through minimum income guarantee to fight poverty. Financial Times, London. 28 May 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/0b6a5d25-e078-4dfc-b314-f659b566317e

- ↵ Kangas O, Jauhiainen S, Simanainen M, Ylikännö M. Evaluation of the Finnish Basic Income Experiment/Suomen perustulokokeilun arviointi Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health/Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö; 2020. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162219/STM_2020_15_rap.pdf

- ↵ Paton C. Coronavirus in Scotland: Nicola Sturgeon eyes plans for universal basic income. The Times, London. 5 May 2020. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/nicola-sturgeon-eyes-plans-for-universal-basic-income-c9rhfwbx7

- Nagelhout GE ,

- de Goeij MCM ,

- de Vries H ,

- Kleinman R ,

- Fischer B ,

- Gardiner C ,

- Geldenhuys G ,

- Olanrewaju O ,

- Lafortune L

- Mitchell W ,

- Widerquist K

- Skidelsky R

An Unemployment Crisis after the Onset of COVID-19

Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau and Robert G. Valletta

Download PDF (115 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2020-12 | May 18, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the U.S. labor market, with massive job losses and a spike in unemployment to its highest level since the Great Depression. How long unemployment will remain at crisis levels is highly uncertain and will depend on the speed and success of coronavirus containment measures. Historical patterns of monthly flows in and out of unemployment, adjusted for unique aspects of the coronavirus economy, can help in assessing potential paths of unemployment. Unless hiring rises to unprecedented levels, unemployment could remain severely elevated well into next year.

The wave of initial job losses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been massive, with more than 20 million jobs swept away between March and April. This is much larger than losses recorded during similar time frames in any other postwar recession. As a result, the April unemployment rate spiked to the highest level recorded since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In this Economic Letter , we assess possible paths for unemployment through 2021. Although the initial scale of the crisis is clear, substantial uncertainty surrounds the future path of unemployment. This uncertainty primarily revolves around the success of virus containment measures and how quickly economic activity can recover. Fundamental measurement challenges are also likely to affect the official unemployment rate: some laid-off workers cannot actively search for new jobs because of shelter-in-place restrictions and hence may be counted as out of the labor force, rather than unemployed.

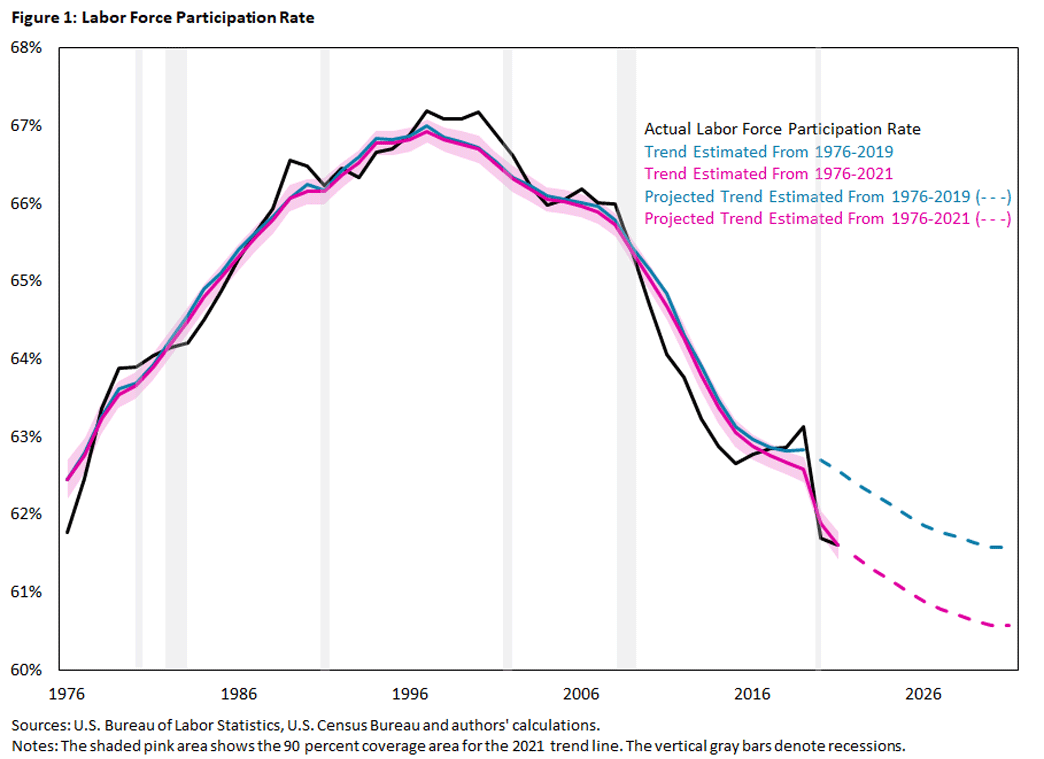

To assess the possible path of the measured unemployment rate through next year, we focus on the underlying monthly flows in and out of unemployment, accounting for historical patterns and unique aspects of the coronavirus economy; our approach and results are described in detail in Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta (2020). Our analysis suggests that returning to pre-outbreak unemployment levels by sometime in 2021 would require a significantly more rapid pace of hiring than during any past economic recovery.

Initial wave of job losses and unemployment

Even before the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released April employment and unemployment numbers on May 8, the unprecedented scale of job losses due to coronavirus containment measures was clear. About 25 million new unemployment insurance (UI) claims were filed between mid-March, when U.S. containment measures started to spread widely and the BLS monthly survey was conducted, and mid-April when the next month’s BLS survey was conducted. During periods of intensive job loss, weekly reports on new UI claims provide a good measure of job losses because most laid-off workers are eligible for UI benefits. However, the current massive scale of new claims has swamped state UI agencies and likely delayed processing of many claims. As such, the recent surge should be interpreted as a loose lower-bound estimate of initial job losses.

A comparison with the Great Recession of 2007-09 starkly illustrates the severity of the current situation (Figure 1). Initial UI claims during the first month of the COVID-19 crisis were about 10 times larger than claims during the worst periods of the Great Recession.

Figure 1 Monthly initial unemployment insurance claims

Note: Data from the U.S. Department of Labor, not seasonally adjusted (last two data points rounded to nearest thousand; April data through May 2). Gray bar indicates NBER recession dates.

These initial job losses, combined with a likely pronounced reduction in hiring activity, imply a sharp increase in the unemployment rate. Before the April BLS report was released, we projected that the unemployment rate was likely to rise nearly 15 percentage points, from 4.4% in March to 19.0% in April.

Other recent projections of the April unemployment rate span a very wide range (Faria-e-Castro 2020, Wolfers 2020, Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber 2020, and Bick and Blandin 2020). The wide range partly reflects the challenge of measuring unemployment when shelter-in-place restrictions prevent active job search in much of the country. This is evident in the estimates by Coibion et al. (2020) and Bick and Blandin (2020), which differed substantially despite their reliance on careful surveys designed to approximate the official BLS approach.

The official April employment report released on May 8 showed that unemployment rose to 14.7%, a huge increase but below our projection. However, the report also noted a large increase in the number of workers on unpaid absences, likely reflecting virus-related business closures. Counting these workers as unemployed would push the unemployment rate much closer to our 19% projection. We therefore have not modified our prior projections.

Unemployment projections based on labor market flows

Our approach to projecting the unemployment rate relies on the monthly flows between unemployment, employment, and out of the labor force (nonparticipation), similar to Şahin and Patterson (2012). In particular, the monthly change in the unemployment rate reflects the difference between the number who enter unemployment (inflows) and the number who exit unemployment (outflows), with employment and nonparticipation as possible initial or subsequent status. This framework accounts for the key determinants of pandemic-related unemployment, with initial UI claims (inflows through job loss) and depressed hiring (outflows) determining the initial spike in unemployment. Using this approach, we explore different scenarios for unemployment through the end of 2021. For all scenarios, we assume that job losses are most severe in April (about 25 million), then ease substantially in May (7.8 million) and June (2.6 million), before returning to their historical trend in July (1.4 million).

The path of the unemployment rate afterward depends on unemployment outflows, primarily reflected in the pace of hiring among the pool of unemployed individuals. Tremendous uncertainty surrounds the timing and strength of the hiring surge as the economy recovers. If the virus is contained quickly and the economic recovery is vigorous, hiring could rapidly resume, particularly if many businesses and workers have maintained their connections. However, hiring could be slow if virus outbreaks or continued containment measures make employers hesitant based on low demand for their products. We therefore explore a range of hiring scenarios over the coming months.

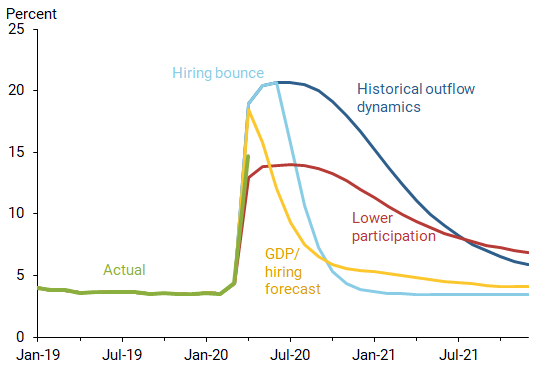

The first scenario, “historical outflow dynamics,” assumes that the pace of hiring corresponds statistically to the typical recovery from past recessions. Because hiring tends to bounce back slowly following recessions, and given the severity of the current downturn, this scenario is relatively adverse.

Our second scenario, “hiring bounce,” incorporates very strong hiring activity following an assumed end of COVID-19 restrictions in July 2020. This scenario provides a baseline for assessing the pace of hiring required to reverse the initial labor market shock. It assumes a return to pre-outbreak hiring rates by the end of the third quarter of 2020. However, the pace of hiring implied by this scenario is extremely high by historical standards given the vast pool of unemployed individuals. In particular, this scenario requires around 9 million hires from unemployment per month during the third quarter, nearly four times faster than the most robust hiring rate during the recovery from the Great Recession.

Our third scenario, “GDP/hiring forecast,” bases hiring projections on the historical relationship between GDP growth and overall exit rates from unemployment to employment or nonparticipation. This requires a GDP forecast. We rely on a recent San Francisco Fed forecast of GDP growth for 2020-21, specifically the more favorable of two alternatives discussed in qualitative terms in Leduc (2020). It assumes that growth bounces back in the second half of this year and continues at a strong pace next year.

Figure 2 shows the unemployment paths for these scenarios. In the historical outflow dynamics scenario (dark blue line), unemployment quickly peaks around 20% and then stays in double digits through early 2021. By contrast, the hiring bounce scenario (light blue line) reflects a stronger recovery in hiring activity, so the unemployment rate drops much more rapidly. At the end of 2020 most of the job losses have been reversed, and unemployment approaches pre-outbreak levels. For the GDP/hiring forecast scenario (yellow line), unemployment peaks above 18% in the second quarter of 2020, followed by a rapid decline in the third quarter due to underlying limited changes in the hiring rate implied by its historical relationship with GDP growth.

Figure 2 Unemployment rate paths under different scenarios

Incorporating unemployment and nonparticipation ambiguities

As noted earlier, widespread shelter-in-place restrictions may preclude active job searches among laid-off workers, causing them to report themselves as out of the labor force rather than unemployed. Consistent with this, the official labor force participation rate fell 2.5 percentage points to 60.2% in April. We explore the potential impact of these measurement challenges through alternative assumptions about flow rates between different labor market states.

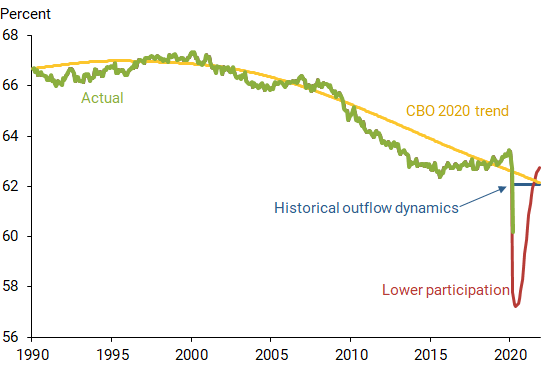

In particular, historical patterns of worker flows from employment to nonparticipation then back into employment during recoveries suggest that nearly half of those workers laid off during the pandemic could leave the labor force upon suffering a job loss. This moderates the initial rise in unemployment, shown as the lower participation scenario (red line) in Figure 2. As individuals return to the labor market during the recovery, lifting the labor force participation rate back toward its previous trend, the pace of return to a pre-outbreak unemployment rate is also muted. In fact, the historical outflow dynamics and lower participation scenarios converge at 8% unemployment in mid-2021. However, these two scenarios imply vastly different trajectories for the labor force participation rate. Figure 3 shows the paths for these scenarios over an extended time frame relative to the trend projected by the Congressional Budget Office (2020).

Figure 3 Labor force participation rate under different scenarios

Conclusions: An uncertain road to recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has created tremendous labor market disruptions and profound hardship throughout the United States and the world. This is partly reflected in the sudden unprecedented increase in the U.S. unemployment rate in April, the first month for which the full effects of coronavirus containment measures are evident. To get a handle on the severity of the labor market disruption, we assess possible paths for unemployment through the end of 2021. Tremendous uncertainty surrounds unemployment projections over the next few years, so we do not claim that any specific scenario qualifies as “likely.” On the pessimistic side, absent a historically unprecedented burst of hiring, the unemployment rate could remain in double digits through 2021. From a more optimistic perspective, if shutdowns are lifted quickly and employers capitalize on the large pool of available workers by ramping up hiring, the unemployment rate could be back down near its pre-outbreak level by mid-2021.

Uncertainty about the path of the unemployment rate also reflects measurement challenges arising from the ambiguous labor force status of laid-off workers whose active job search is limited by shelter-in-place measures. This may temper the official unemployment rate, but at the expense of a lower labor force participation rate, which is an alternative indicator of labor market dislocation and hardship. Given the implied uncertainty about the measurement of future labor market conditions, it is imperative to closely monitor a wide range of indicators to assess how the U.S. labor market is evolving in response to the COVID-19 shock.

Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau is a vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Robert G. Valletta is a senior vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Bick, Alexander, and Adam Blandin. 2020. “Real Time Labor Market Estimates during the 2020 Coronavirus Outbreak.” Manuscript, Arizona State University, April 15.

Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber. 2020. “Labor Markets During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View.” BFI Working Paper, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, University of Chicago, April 13.

Congressional Budget Office. 2020. “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030.” Report 56020, January 28.

Faria-e-Castro, Miguel. 2020. “Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates of Next Quarter’s Unemployment Rate.” On the Economy, FRB St. Louis blog, March 24.

Leduc, Sylvain. 2020. “FedViews.” FRB San Francisco, April 6.

Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas, and Robert G. Valletta. 2020. “Unemployment Paths in a Pandemic Economy.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2020-18, May.

Şahin, Ayşegül, and Christina Patterson. 2012. “The Bathtub Model of Unemployment: The Importance of Labor Market Flow Dynamics.” Liberty Street Economics, FRB New York blog, March 28.

Wolfers, Justin. 2020. “The Unemployment Rate Is Probably Around 13%.” New York Times (The Upshot), April 16.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What’s Going On in This Graph? | Unemployment During the Pandemic

Who wants a job, but doesn’t have one? How has the composition of the unemployed in the United States changed during the pandemic?

By The Learning Network

This graph shows the composition of the unemployed in the United States from January – September 2020. The graph appeared elsewhere on NYTimes.com.

By Friday morning, Nov. 6, we will reveal the graph’s free online link, additional background and questions, shout-outs for great student headlines, and Stat Nuggets.

After looking closely at the graph above (or at this full-size image ), answer these four questions:

What do you notice?

What do you wonder?

What impact does this have on you and your community?

What’s going on in this graph? Write a catchy headline that captures the graph’s main idea.

The questions are intended to build on one another, so try to answer them in order.

2. Next, join the conversation online by clicking on the comment button and posting in the box. (Teachers of students younger than 13 are welcome to post their students’ responses.)

3. Below the response box, there is an option for students to click on “Email me when my comment is published.” This sends the link to their response which they can share with their teacher.

4. After you have posted, read what others have said, then respond to someone else by posting a comment. Use the “Reply” button to address that student directly.

On Wednesday, Nov. 4, teachers from our collaborator, the American Statistical Association , will facilitate this discussion from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. Eastern time.

5. By Friday morning, Nov. 6, we will reveal more information about the graph, including a free link to the article that included this graph, at the bottom of this post. We encourage you to post additional comments based on the article, possibly using statistical terms defined in the Stat Nuggets.

• See all graphs in this series or a slide show of 60 of our favorite graphs .

• View our archives that link to all past releases, organized by topic , graph type and Stat Nugget .

• Learn more about the “ Notice and Wonder ” teaching strategy and how and why other teachers are using this feature from our on-demand webinar .

• Sign up for our free weekly Learning Network newsletter so you never miss a graph. Graphs are always released by the Friday before the Wednesday live-moderation to give teachers time to plan ahead.

• Go to the American Statistical Association K-12 website , which includes teacher statistics resources, professional development opportunities, and more.

Students 13 and older in the United States and the United Kingdom, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

UPDATED: Nov. 5, 2020

“Covid-19 tore a hole through the U.S. economy,” says The New York Times’ October 3, 2020 article “Job Gains Lose Momentum As Promising Recovery Stalls.” As of October, the national economy had 11 million fewer jobs than before the pandemic. The total number of unemployed workers both in and out of the workforce, which is calculated from different sources than the jobs data, went from 12 million in January 2020, then exploded to 32 million in April 2020 (167 percent increase) before subsiding to 19 million by September 2020. (This was an 58 percent increase over January 2020). It is not surprising that in an October 5-11, 2020 online survey conducted by SurveyMonkey for The New York Times, 30 percent of respondents said that they were financially worse off.

This “vase” graph appeared in the October 12, 2020 New York Times article “ The Shape(s) of a Crisis .” It shows the composition of the “total unemployed”, those who have been temporarily laid off, have been out of work for less than four weeks, or are in the “other” category. The “other” category of unemployed workers includes those who had temporary jobs or who chose to leave their jobs because of transportation issues, needing to care for their family, susceptibility to the virus, and other issues. The graph also shows the number of workers who are not in the labor force (including those who have been unemployed for more than four weeks), but want a job.

How many workers have returned to work? Based on the shapes of the subgroups in the vase graph, which workers may have shifted between from one subgroup to another?

Here are some of the student headlines that capture the stories of these graphs: “Unemployment: The Silent Killer” by Sadie of Dallas; “As Covid-19 Spreads, So Does Unemployment” by Katie of Andover, Massachusetts; “Increasing Pandemic, Lowering Paychecks” by Aboubakary and “A Job Pandemic” by Victor, both of the Bronx, New York; and “Is Corona Firing People?” by Zamir and “Unemployment: A Covid Conundrum” by Aidan, both of New York.

You may want to think critically about these questions:

The number of temporarily laid off workers has diminished since April. Based on evidence in the graph, what employment status could these people now have? Some options may be within the graph; others may be outside the graph.

Some workers are unemployed because of family or transportation issues. What are some of the specifics of these issues? Where would these people be shown in the graph in April? In August?

Workers have been affected differently based on the business sector in which they worked. After studying the graphs in the October 3, 2020 New York Times article “ Jobs Gains Lose Momentum as Promising Recovery Stalls ,” answer these questions:

Which business sectors have seen an increase in jobs?

Which business sectors are seeing the greatest adverse effect due to the pandemic and have reduced their workforce?

Overall, what has been the net effect (increases in the number of employees minus the decreases in the number of employees)? What surprises do you see in job gains and losses?

This graph could be called a vase graph because of its shape. Why do you think the graphic designers used a vase graph rather than the typical time series graph with stacked areas for each of the subgroups with Jan. 2020 – Sept. 2020 on the x -axis and number of unemployed on the y -axis?

Because of the Veteran’s Day holiday on Wednesday, November 11, there will be no graph release for next week. The next release will be by Friday, Nov. 13 with live-moderation on Wednesday, Nov. 18. The topic: Thanksgiving favorite foods. So you don’t miss any releases, you can receive the 2020-2021 “What’s Going On In This Graph?” schedule by subscribing here to the Learning Network Friday newsletter. Keep noticing and wondering.

Stat Nuggets for “ The Shape(s) of a Crisis ”

To see the archives of all Stat Nuggets with links to their graphs, go to this index .

STACKED AREA GRAPH

Stacked area graphs show trends over time and compare the relative sizes of subgroups of a whole. The comparison may be in terms of absolute numbers or percentages.

In the pandemic unemployment graph, the time period is January 2020 to September 2020. The whole is the total number of unemployed plus people who are not in the labor force but want a job. The category of unemployed is divided into the subgroups of temporarily laid off, permanently laid off, and other. The other category includes workers who chose to leave their jobs or who had temporary jobs. What is usual about this graph is that time is on the vertical axis and the number of workers is on the horizontal axis. The variable, number of workers, is represented by the total distance from both sides of the center vertical line.

The graphs for “What’s Going On in This Graph?” are selected in partnership with Sharon Hessney. Ms. Hessney wrote the “reveal” and Stat Nuggets with Erica Chauvet, mathematics professor at Waynesburg University in Pennsylvania, and moderates online with Dashiell Young-Saver, a high school statistics teacher in San Antonio and data science graduate student at Harvard. He is the founder of Skew The Script, which provides relevant math and statistics curriculum to teachers.

How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected the U.S. Labor Market?

Social distancing and the partial economic shutdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound impact on the U.S. economy, including on people’s jobs and livelihoods.

The overall immediate effects on the labor market have been easy to see: The unemployment rate shot up in the early months of the COVID-19 crisis in the U.S., and payroll employment numbers show that more than 20 million jobs were lost in April—a record amount for one month. (Employment has increased every month since then, and unemployment declined to 7.9% in September after a 14.7% April peak.)

But these aggregate numbers don’t tell the whole story. There are many ways to dissect data to get a more complete sense of how the pandemic has affected the U.S. labor market, including which workers have felt the most impact.

This post provides a roundup of some recent St. Louis Fed analyses that examined different aspects of unemployment and employment during the pandemic. Some takeaways:

- When other measures of unemployment started declining, the share of those unemployed for at least 15 weeks continued to rise.

- The youngest workers saw the biggest decline in employment.

- The leisure and hospitality sector lost the most jobs in the early months of the pandemic.

- The lowest-earning occupations were hit the hardest by the pandemic.

What are various measures of unemployment showing us?

An Oct. 5 FRED Blog post discussed how six measures of labor underutilization from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) changed with the pandemic.

Among the measures included in the above graph from the blog post are the official unemployment rate; a measure of those unemployed 15 weeks or longer; and measures that take into account discouraged workers and others who are marginally attached to the labor force, and those who want full-time work but can only get part-time work.

As noted in the post and seen in the graph, all of the measures increased dramatically, but they didn’t all move in parallel—in other words, the distance between the lines didn’t stay constant.

“The lines fanned out, showing that it wasn’t one particular type of unemployment that was responsible for the overall surge,” said the post, which was suggested by Christian Zimmermann , assistant vice president of research information services.

Of particular note, the share of workers unemployed for at least 15 weeks was still increasing in August while the other unemployment measures were decreasing, the post pointed out. These workers made up 5.1% of the labor force in August, although the share ticked down to 4.6% in September.

(For more information, check out this June 2018 Open Vault blog post on the different measures of unemployment and this August 2020 post on labor force participation.)

What do we learn from looking at employment levels by age group?

An Oct. 8 FRED Blog post , also suggested by Zimmermann, breaks down employment levels by age group using data from the BLS.

As shown in the graph above, the youngest groups were hit the hardest during the COVID-19 related recession. The blog post noted that, from February to April:

- 35% of workers 16-19 years old lost their jobs.

- 30% of those 20-24 years old lost their jobs.

- Job losses for the other age groups ranged from 11% to 16%.

The declines in employment for the older age groups were still sizeable, but much smaller than those of the two youngest groups, the post noted.

“Are the young taking one for the team just for this recession?” the post asked. “Or have they always been first to be let go?”

The youngest group saw the largest decline in employment in each of the three previous recessions, as discussed in the post. In some previous cases, those 55 years and older and/or those 45 to 54 years old even saw employment gains. (See graphs for the 2007-09 recession , the 2001 recession and the 1990-91 recession .)

“All in all, it appears ‘normal’ that the 16- to 19-year-old age group is hit hardest by recessions and that the oldest workers are largely unaffected, at least in terms of employment,” the post said. “The current recession is a little different in that the older groups have also been affected, just not as much as the younger groups.”

Which industries have been most affected?

In a Regional Economist article published in August, Senior Economist Maximiliano Dvorkin noted that safety measures have impacted businesses that involve direct contact with customers or clients in particular. He examined which industries were the most affected by labor market disruptions during the early months of the pandemic. (He also analyzed which occupations were most affected, but this post focuses on industries.)

Dvorkin looked at several goods-producing industries and service-providing industries. The industries Dvorkin looked at are mining and logging; construction; durable goods manufacturing; nondurable goods manufacturing; trade, transportation and utilities; information; financial activities; professional and business services; education and health services; leisure and hospitality; other services; and government. He found that the leisure and hospitality services sector saw the largest decline from February to April, with nearly half of these jobs being lost. This was followed by the “other services” sector—which includes businesses such as repair and maintenance and beauty shops—where about one in five jobs was lost.

In contrast, the financial activities sector and the government sector saw relatively small declines in employment over this period, he found.

February to April Payroll Employment Declines by Industry

Leisure and Hospitality: -48.3%

Other Services: -22.0%

Financial Activities: -3.0%

Government: -4.4%

SOURCES: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and Maximiliano Dvorkin’s calculations. Adapted from Table 1 in “ Which Jobs Have Been Hit Hardest by COVID-19? ,” a Regional Economist article by Dvorkin published Aug. 17, 2020.

Which wage earners have been hit the hardest?

In an Economic Synopses essay published in July , Economist Serdar Birinci and Research Associate Aaron Amburgey looked at how the pandemic has impacted various occupations across the earnings distribution.

Overall, they found that workers in occupations with lower average earnings were disproportionally displaced by the pandemic, whereas workers in occupations with higher average earnings were impacted to a lesser extent.

For their analysis, Birinci and Amburgey broke occupations into five equal groups (quintiles) based on the average earnings of someone in that particular line of work. The table below, which is recreated from their essay, shows some examples that are included in each group.

The authors noted that the majority of the jobs that were furloughed or lost between January and April were in the lower-earnings occupations. In particular, they found that occupations in the lowest and second-lowest earnings groups accounted for 34% and 25%, respectively, of the increase in unemployment over that period.

They also found that the unemployment rates for the lower-earnings groups increased by much more than for the higher-earnings groups. For example, workers in occupations in the lowest-earnings group saw their unemployment rate increase by 20.4 percentage points from January to April. In comparison, workers in occupations in the highest-earnings group experienced only a 3.2 percentage point increase in their unemployment rate over that period.

“These results provide further evidence that the COVID-19 crisis has had an unbalanced effect on different earnings groups in the labor market,” they wrote.

1 The industries Dvorkin looked at are mining and logging; construction; durable goods manufacturing; nondurable goods manufacturing; trade, transportation and utilities; information; financial activities; professional and business services; education and health services; leisure and hospitality; other services; and government.

Kristie Engemann is a senior coordinator in the St. Louis Fed External Engagement and Corporate Communications Division.

Related Topics

This blog explains everyday economics, consumer topics and the Fed. It also spotlights the people and programs that make the St. Louis Fed central to America’s economy. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

COVID-19 job and income loss leading to more hunger and financial hardship

Subscribe to global connection, mathieu despard , mathieu despard faculty director - social policy institute at washington university in st. louis michal grinstein-weiss , michal grinstein-weiss nonresident senior fellow - economic studies @michalgw yung chun , and yung chun data analyst iii - social policy institute at washington university in st. louis stephen roll stephen roll research assistant professor, social policy institute, brown school - washington university in st. louis.

July 13, 2020

A startling indicator of the economic impact of COVID-19 is that unemployment rates reached the highest level since the Great Depression in April. As a result, claims for unemployment benefits have risen dramatically, though millions of people who have lost their jobs have been unable to apply or have had trouble applying for this benefit. Yet these figures do not reveal the extent to which households are struggling financially as a result of a COVID-19 related job loss.

To report findings about COVID-19 job and income losses and financial hardships, the Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis administered a unique nationally representative survey to 5,500 respondents from April 27 to May 12 . A job loss is one of the worst financial shocks most families will face, making it extremely difficult to make ends meet and avoid devastating downstream effects like foreclosures or evictions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment reached historic heights with more than 40 million unemployment benefit claims filed —even exceeding the unemployment levels during the Great Depression

Impacts of COVID-19 on job loss

The survey found that 24 percent of respondents lost a job or income due to COVID-19. Most of these job or income losses were due to being furloughed or experiencing reduced work hours.

However, these job and income losses were not experienced equally. Hispanic, low-income, and young individuals (between the ages of 18 and 24) had the highest rates of job and income loss compared to other racial/ethnic, income, and age groups, as reflected in the charts below.

While job and income loss rates were very similar among moderate-, middle-, and high-income respondents, low-income and Hispanic respondents—those least able to cope with economic shocks—had a distinctly higher rate of job and income loss. That job and income losses were highest among Hispanic respondents is likely related to their disproportionate representation in industries hard hit by COVID-19 related layoffs such as hospitality and construction. Conversely, black workers are disproportionately represented in industries such as health care and transportation that have been less affected.

Differences in COVID-19 related job and income losses were most pronounced by age. Young adults between the ages of 18 to 24 experienced job or income losses nearly twice as much as older age groups.

Yet are COVID-19 related job and income losses affecting the ability of U.S. households to make ends meet? One way to know is to look at different types of economic hardship, such as difficulty paying for housing and other bills, putting off medical care and filling prescriptions, and experiencing food insecurity. As the graph below indicates, COVID-19 related job and income losses are clearly related to increased hardship such as difficulty making housing payments—even after controlling for income, age, gender, and household size (Figure 4).