Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

213 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Growth mindset and social comparison effects in a peer virtual learning environment

- Pamela Sheffler

- Cecilia S. Cheung

Social Psychology of Education (2024)

Nursing students’ learning flow, self-efficacy and satisfaction in virtual clinical simulation and clinical case seminar

- Sunghee H. Tak

BMC Nursing (2023)

Online learning for WHO priority diseases with pandemic potential: evidence from existing courses and preparing for Disease X

- Heini Utunen

- Corentin Piroux

Archives of Public Health (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018

Affiliation.

- 1 Educational Leadership, University of North Carolina Charlotte, 9201 University City Blvd, Charlotte, NC, 28223, USA.

- PMID: 32921895

- PMCID: PMC7480742

- DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104009

Systematic reviews were conducted in the nineties and early 2000's on online learning research. However, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. This systematic review addresses this gap by examining 619 research articles on online learning published in twelve journals in the last decade. These studies were examined for publication trends and patterns, research themes, research methods, and research settings and compared with the research themes from the previous decades. While there has been a slight decrease in the number of studies on online learning in 2015 and 2016, it has then continued to increase in 2017 and 2018. The majority of the studies were quantitative in nature and were examined in higher education. Online learning research was categorized into twelve themes and a framework across learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was developed. Online learner characteristics and online engagement were examined in a high number of studies and were consistent with three of the prior systematic reviews. However, there is still a need for more research on organization level topics such as leadership, policy, and management and access, culture, equity, inclusion, and ethics and also on online instructor characteristics.

Keywords: Distance education; Online Learning Research; Research Themes; Systematic Review; online teaching and learning.

© 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Advertisement

A Survey on the Effectiveness of Online Teaching–Learning Methods for University and College Students

- Article of professional interests

- Published: 05 April 2021

- Volume 102 , pages 1325–1334, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Preethi Sheba Hepsiba Darius ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0882-6213 1 ,

- Edison Gundabattini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4217-2321 2 &

- Darius Gnanaraj Solomon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5321-5775 2

132k Accesses

33 Citations

Explore all metrics

Online teaching–learning methods have been followed by world-class universities for more than a decade to cater to the needs of students who stay far away from universities/colleges. But during the COVID-19 pandemic period, online teaching–learning helped almost all universities, colleges, and affiliated students. An attempt is made to find the effectiveness of online teaching–learning methods for university and college students by conducting an online survey. A questionnaire has been specially designed and deployed among university and college students. About 450 students from various universities, engineering colleges, medical colleges in South India have taken part in the survey and submitted responses. It was found that the following methods promote effective online learning: animations, digital collaborations with peers, video lectures delivered by faculty handling the subject, online quiz having multiple-choice questions, availability of student version software, a conducive environment at home, interactions by the faculty during lectures and online materials provided by the faculty. Moreover, online classes are more effective because they provide PPTs in front of every student, lectures are heard by all students at the sound level of their choice, and walking/travel to reach classes is eliminated.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Critical thinking and creativity of students increase with innovative educational methods according to the world declaration on higher education in the twenty-first century [ 1 ]. Innovative educational strategies and educational innovations are required to make the students learn. There are three vertices in the teaching–learning process viz., teaching, communication technology through digital tools, and innovative practices in teaching. In the first vertex, the teacher is a facilitator and provides resources and tools to students and helps them to develop new knowledge and skills. Project-based learning helps teachers and students to promote collaborative learning by discussing specific topics. Cognitive independence is developed among students. To promote global learning, teachers are required to innovate permanently. It is possible when university professors and researchers are given space to new educational forms in different areas of specializations. Virtual classrooms, unlike traditional classrooms, give unlimited scope for introducing teaching innovation strategies. The second vertex refers to the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools for promoting innovative education. Learning management systems (LMS) help in teaching, learning, educational administration, testing, and evaluation. The use of ICT tools promotes technological innovations and advances in learning and knowledge management. The third vertex deals with innovations in teaching/learning to solve problems faced by teachers and students. Creative use of new elements related to curriculum, production of something new, and transformations emerge in classrooms resulting in educational innovations. Evaluations are necessary to improve the innovations so that successful methods can be implemented in all teaching and learning community in an institution [ 2 ]. The pandemic has forced digital learning and job portal Naukri.com reports a fourfold growth for teaching professionals in the e-learning medium [ 3 ]. The initiatives are taken by the government also focus on online mode as an option in a post-covid world [ 4 ]. A notable learning experience design consultant pointed out that, educators are entrusted to lead the way as the world changes and are actively involved in the transformation [ 5 ]. Weiss notes that an educator needs to make the lectures more interesting [ 6 ].

This paper presents the online teaching–learning tools, methods, and a survey on the innovative practices in teaching and learning. Advantages and obstacles in online teaching, various components on the effective use of online tools, team-based collaborative learning, simulation, and animation-based learning are discussed in detail. The outcome of a survey on the effectiveness of online teaching and learning is included. The following sections present the online teaching–learning tools, the details of the questionnaire used for the survey, and the outcome of the survey.

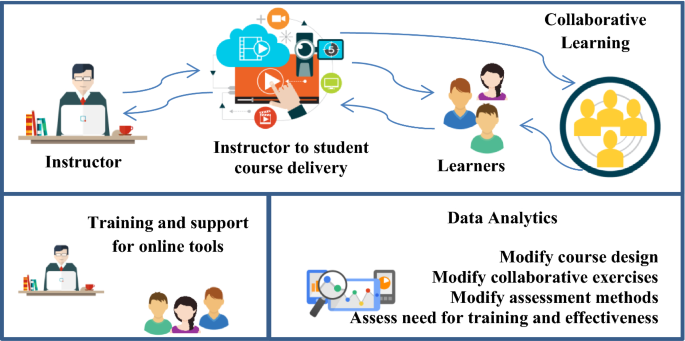

Online Teaching and Learning Tools

The four essential parts of online teaching [ 7 ] are virtual classrooms, individual activities, assessments in real-time, and collaborative group work. Online teaching tools are used to facilitate faculty-student interaction as well as student–student collaborations [ 8 ]. The ease of use, the satisfaction level, the usefulness, and the confidence level of the instructor is crucial [ 9 ] in motivating the instructor to use online teaching tools. Higher education institutes recognize the need to accommodate wide diverse learners and Hilliard [ 10 ] points out that technical support and awareness to both faculty and student is essential in the age of blended learning. Data analytics tool coupled with the LMS is essential to enhance [ 11 ] the quality of teaching and improve the course design. The effective usage of online tools is depicted in Fig. 1 comprising of an instructor to student delivery, collaboration among students, training for the tools, and data analytics for constant improvement of course and assessment methods.

The various components of effective usage of online tools

Online Teaching Tools

A plethora of online teaching tools are available and this poses a challenge for decision-makers to choose the tools that best suits the needs of the course. The need for the tools, the cost, usability, and features determine which tools are adopted by various learners and institutions. Many universities have offered online classes for students. These are taken up by students opting for part-time courses. This offers them flexibility in timing and eliminates the need for travel to campus. The pandemic situation in 2019 has forced many if not all institutions to completely shift classes online. LMS tools are packaged as Software as a Service (SaaS) and the pricing generally falls into 4 categories: (i) per learner, per month (ii) per learner, per use (iii) per course (iv) licensing fee for on-premise installation [ 12 ].

Online Learning Tools

Online teaching/learning as part of the ongoing semester is typically part of a classroom management tool. GSuite for education [ 13 ] and Microsoft Teams [ 14 ] are both widely adopted by schools and colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic to effectively shift regular classes online. Other popular learning management systems that have been adopted as part of blended learning are Edmodo [ 15 ], Blackboard [ 16 ], and MoodleCloud [ 17 ]. Davis et al. [ 18 ] point out advantages and obstacles for both students and instructors about online teaching shown in Table 1 .

The effectiveness of course delivery depends on using the appropriate tools in the course design. This involves engaging the learners and modifying the course design to cater to various learning styles.

A Survey on Innovative Practices in Teaching and Learning

The questionnaire aims to identify the effectiveness of various online tools and technologies, the preferred learning methods of students, and other factors that might influence the teaching–learning process. The parameters were based on different types of learners, advantages, and obstacles to online learning [ 10 , 18 ]. Questions 1–4 are used to comprehend the learning style of the student. Questions 5–7 are posed to find out the effectiveness of the medium used for teaching and evaluation. Questions 8–12 are framed to identify the various barriers to online learning faced by students.

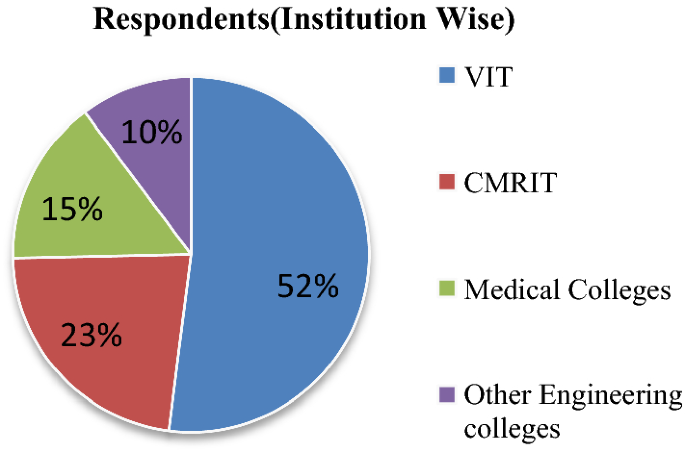

This methodology is adopted as most of the students are attending online courses from home and polls of this kind will go well with the students from various universities. Students participated in the survey and answered most of the questionnaire enthusiastically. The only challenge was a suitable environment and free time for them to answer the questionnaire, as they are already loaded with lots of online work. Students from various universities pursuing professional courses like engineering and medicine took part in this survey. They are from various branches of sciences and technologies. Students are from private universities, colleges, and government institutions. Figure 2 shows the institution-wise respondents. Microsoft Teams and Google meet platforms were used for this survey among university, medical college, and engineering college students. About 450 students responded to this survey. 52% of the respondents are from VIT University Vellore, Tamil Nadu, 23% of the respondents are from CMR Institute of Technology (CMRIT), Bangalore, 15% of the respondents are from medical colleges and 10% are from other engineering colleges. During this pandemic period, VIT students are staying with parents who are living in different states of India like Andhra, Telangana, Kerala, Karnataka, MP, Haryana, Punjab, Maharashtra, Andaman, and so on. Only a few students are living in Tamil Nadu. Some of the students are staying with parents in other countries like Dubai, Oman, South Africa, and so on. Some of the students of CMRIT Bangalore are living in Bangalore and others in towns and villages of Karnataka state. Students of medical colleges are living in different parts of Tamil Nadu and students of engineering colleges are living in different parts of Andhra Pradesh. Hence, the survey is done in a wider geographical region.

Institution-wise respondents

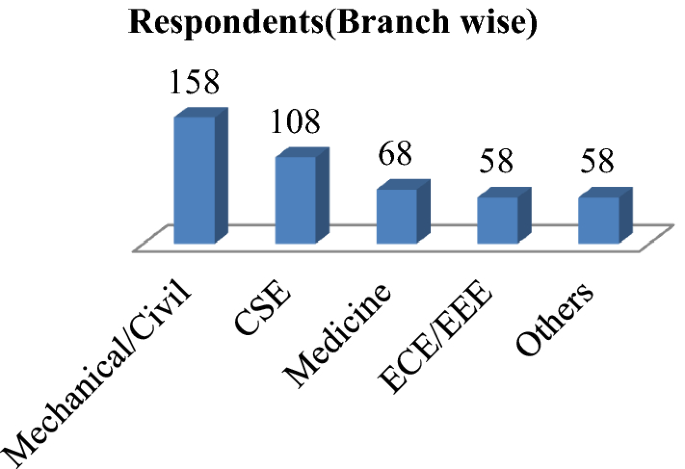

Figure 3 shows the branch-wise respondents. It is shown that 158 students belong to mechanical/civil engineering. 108 respondents belong to computer science and engineering, 68 students belong to medicine, 58 students belong to electrical & electronics engineering, and electronics & communication engineering. 58 students belong to other disciplines.

Branch-wise respondents

Questionnaire Used

Students were assured of their confidentiality and were promised that their names would not appear in the document. A list of the questions asked as part of the survey is given below.

Questionnaire:

Sample group: B Tech students from different branches of sciences across various engineering institutions and MBBS medical students.

Which of the methods engage you personally to learn digitally ?

Individual assignment

Small group (No. 5 students) work

Large group (No. 10 students and more) work

Project-based learning

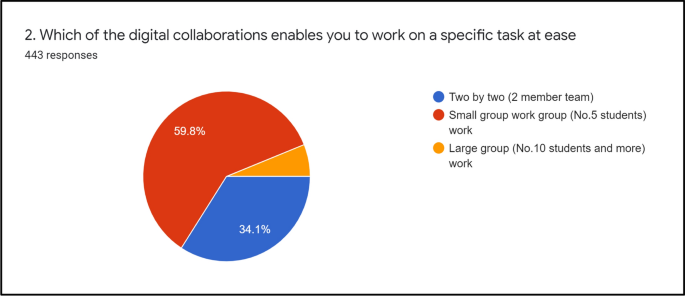

Which of the digital collaborations enables you to work on a specific task at ease

Two by two (2 member team)

Small group workgroup (No. 5 students) work

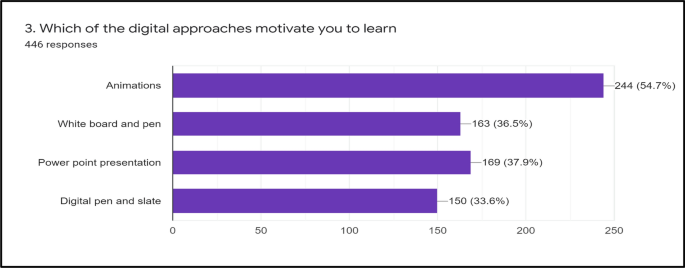

Which of the digital approaches motivate you to learn

Whiteboard and pen

PowerPoint presentation

Digital pen and slate

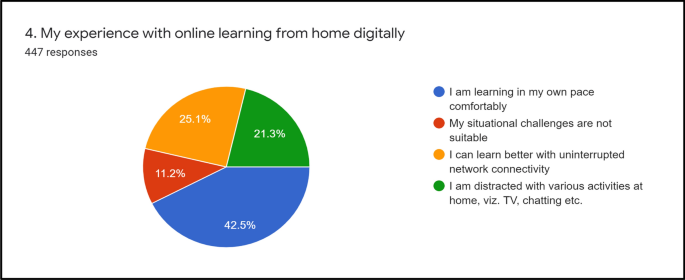

My experience with online learning from home digitally

I am learning at my own pace comfortably

My situational challenges are not suitable

I can learn better with uninterrupted network connectivity

I am distracted with various activities at home, viz. TV, chatting, etc.

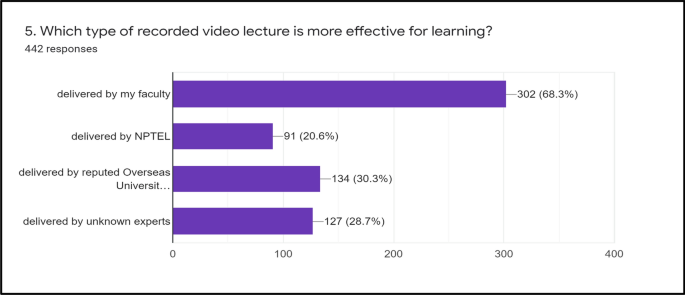

Which type of recorded video lecture is more effective for learning ?

delivered by my faculty

delivered by NPTEL

delivered by reputed Overseas Universities

delivered by unknown experts

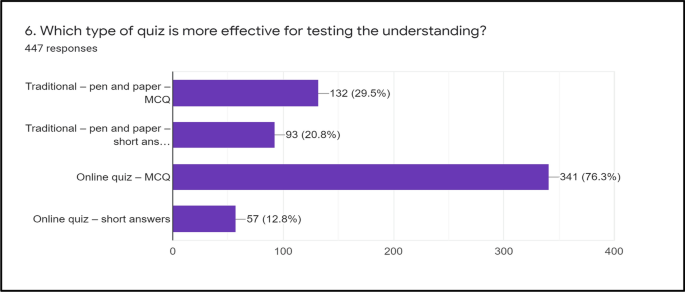

Which type of quiz is more effective for testing the understanding?

Traditional—pen and paper—MCQ

Traditional—pen and paper—short answers

Online quiz—MCQ

Online quiz—short answers

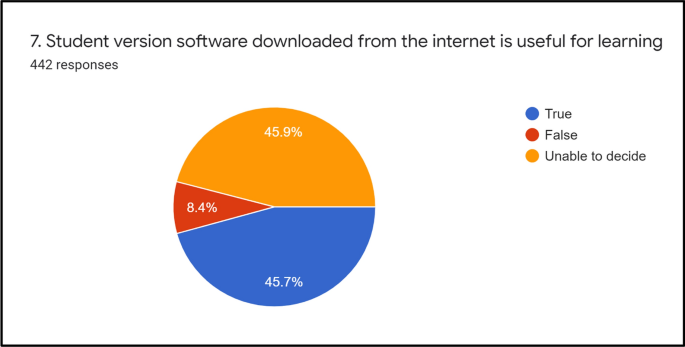

Student version software downloaded from the internet is useful for learning

Unable to decide

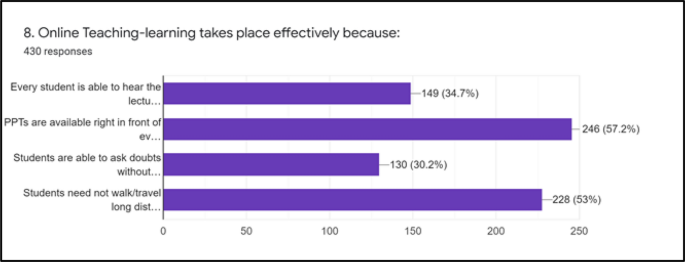

Online teaching – learning takes place effectively because:

Every student can hear the lecture clearly

PPTs are available right in front of every student

Students can ask doubts without much reservation

Students need not walk long distances before reaching the class

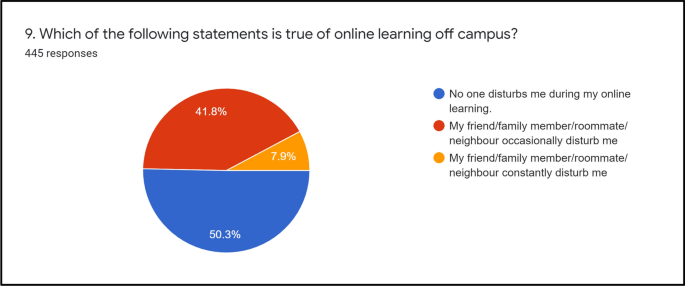

Which of the following statements is true of online learning off-campus ?

No one disturbs me during my online learning.

My friend/family member/roommate/neighbor occasionally disturb me

My friend/family member/roommate/neighbor constantly disturb me

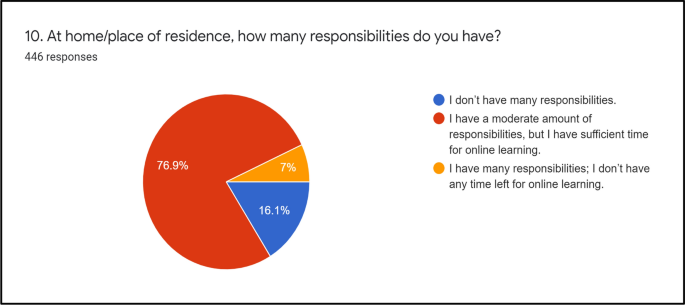

At home/place of residence, how many responsibilities do you have?

I don’t have many responsibilities.

I have a moderate amount of responsibilities, but I have sufficient time for online learning.

I have many responsibilities; I don’t have any time left for online learning.

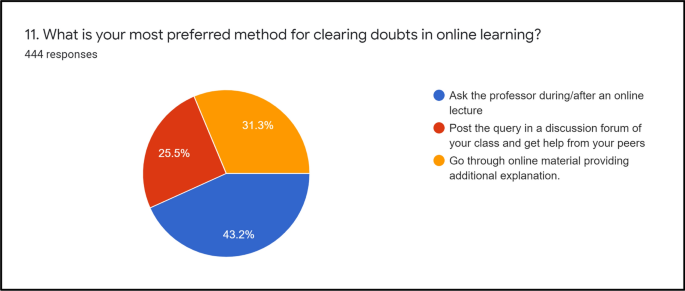

What is your most preferred method for clearing doubts in online learning?

Ask the professor during/after an online lecture

Post the query in a discussion forum of your class and get help from your peers

Go through online material providing an additional explanation.

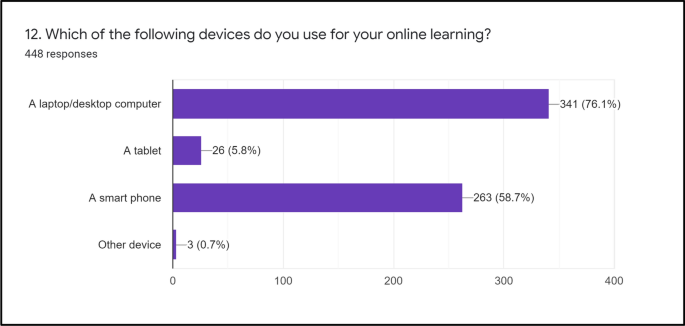

Which of the following devices do you use for your online learning?

A laptop/desktop computer

A smartphone

Other devices

Outcome of the survey

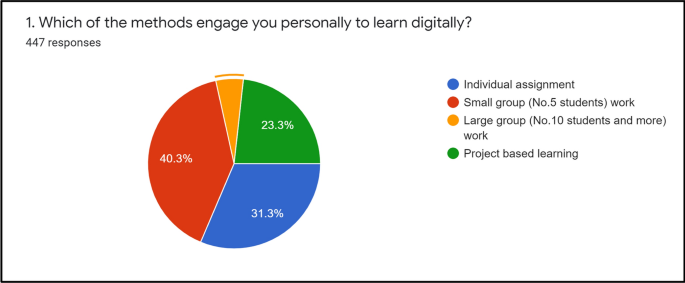

Students would prefer to work in a group of 5 students to engage personally in digital learning as seen from Fig. 4 .

Personal engagement in digital learning

Digital collaboration to enable students to work at ease on a specific task is to allow them to work in small groups of 5 students as seen in Fig. 5 .

Digital collaboration to enable students to work at ease

Animations are found to be the best digital approach motivating many students to learn as seen in Fig. 6 .

Digital approaches that motivate students to learn

The online learning experience of students is shown in Fig. 7 . The majority of students have said that they can learn at their own pace comfortably through online learning.

The online learning experience of students

The effectiveness of the recorded video lecture is shown in Fig. 8 . The majority of students agree that the video lectures delivered by his/her faculty teaching the subject help students to learn effectively.

More effective recorded video lecture

Online quiz having multiple-choice questions (MCQ) is preferred by most of the students for testing their understanding of the subject as seen in Fig. 9 .

More effective quiz for testing the understanding

The usefulness of the student version of the software downloaded from the internet is shown in Fig. 10 . 45.7% of the students agree that it is useful for learning whereas 45.2% of them are unable to decide. The rest of the students feel that the student version of the software is not useful.

The usefulness of the student version of the software

The reasons for the effectiveness of online teaching–learning are shown in Fig. 11 . The majority of the students, feel that the PPTs are available right in front of every student so that following the lecture makes the learning effective. In universities where a fully flexible credit system (FFCS) is followed, students need to walk long distances for reaching their classrooms. Day Scholars in universities as well as engineering colleges are required to travel a considerable distance before reaching the first-hour class. According to many students, online learning is more effective since walking/traveling is completed eliminated. If the voice of the faculty member is feeble, students sitting in the last few rows of the class would not hear the lecture completely. Some students feel that online learning is more effective since the lecture is reaching every student irrespective of the number of students in a virtual classroom.

Reasons for the effectiveness of online teaching–learning

50.3% of students agree that they do not have any disturbance during online learning and it is more effective. Many of them feel that occasionally their friends or relatives disturb students during their online learning as shown in Fig. 12 .

Disturbances during online learning

Figure 13 shows the environment at home for online learning. 76.9% of the respondents stated that they have a moderate amount of responsibilities at home but they have sufficient time for online learning. 16.1% of them have said that they do not have many responsibilities whereas 7% of them claimed that they have many responsibilities at home and they do not have any time left for online learning.

The environment at home for online learning

Figure 14 shows the methods adopted for clearing doubts in online learning. 43.2% of the respondents ask the Professor and get their doubts clarified during online lectures. 25.5% of them post queries in the discussion forum and help from peers. 31.3% of them go through the online materials providing additional explanation and get their doubts clarified.

Methods adopted for clearing doubts in online learning

Figure 15 shows the devices used by students for online learning. Most of the students use laptop/desktop computers, many of them use smartphones and very few students use tablets.

Devices used for online learning

The association between responses 1 and 2 is tested using the chi-square test. The results are presented in Table 2 which shows the observed cell totals, expected cell values, and chi-square statistic for each cell. It is seen that association exists between several responses between questions.

The observed cell values indicate that the highest association is found between responses 1b and 2b since both these responses are related to a small working group having 5 members. The lowest association is found between the responses of 1c and 2a having the lowest observed cell value and expected cell value. The reason for this is response 1c shows the work done by a 10 member team and the response 2a shows a two-member team. The chi-square statistic is 65.6025. The p value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

The outcome of a survey on the effectiveness of innovations in online teaching–learning methods for university and college students is presented. About 450 students belonging to VIT Vellore, CMRIT Bangalore, Medical College, Pudukkottai, and engineering colleges have responded to the survey. A questionnaire designed for taking is survey is presented. The chi-square statistic is 65.6025. The p value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05. Associations between several responses of questions exist. The survey undertaken provides an estimate of the effectiveness and pitfalls of online teaching during the online teaching that has been taking place during the pandemic. The study done paves the way for educators to understand the effectiveness of online teaching. It is important to redesign the course delivery in an online mode to make students engaged and the outcome of the survey supports these aforementioned observations.

The outcome of the survey is given below:

A small group of 5 students would help students to have digital collaboration and engage personally in digital learning.

Animations are found to be the best digital approach for effective learning.

Online learning helps students to learn at their own pace comfortably.

Students prefer to learn from video lectures delivered by his/her faculty handling the subject.

Online quiz having multiple-choice questions (MCQ) preferred by students.

Student version software is useful for learning.

Online classes are more effective because they provide PPTs in front of every student, lectures are heard by all students at the sound level of their choice, and walking/travel to reach classes is eliminated.

Students do not have any disturbances or distractions which make learning more effective.

But for a few students, most of the students have no or limited responsibilities at home which provides a good ambiance and a nice environment for effective online learning.

Students can get their doubts clarified during lectures, by posting queries in discussion forums and by referring to online materials provided by the faculty.

World Declaration on Higher Education for the Twenty-first Century: Vision and Action (1998) https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141952 . Accessed on 10 December 2020.

S. Cadena-Vela, J.O. Herrera, G. Torres, G. Mejía-Madrid, Innovation in the university, in: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality-TEEM’18 (2018), pp. 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1145/3284179.3284308

Demand for online tutors soars, pay increases 28%. Times of India (2020) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/demand-for-online-tutors-soars-pay-increases-28/articleshow/77939414.cms . Accessed on 7 December 2020

Can 100 top universities expand e-learning opportunities for 3.7 crore students. Times of India (2020) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/news/can-100-top-universities-expand-e-learning-opportunities-for-3-7-crore-students/articleshow/76032068.cms . Accessed on 9 December 2020.

C. Malemed, Retooling instructional design (2019). https://theelearningcoach.com/elearning2-0/retooling-instructional-design/ accessed on 8 December 2020

C. Wiess, COVID-19 and its impact on learning (2020). https://elearninfo247.com/2020/03/16/covid-19-and-its-impact-on-learning/ . Accessed on 10 December 2020

E. Alqurashi, Technology tools for teaching and learning in real-time, in Educational Technology and Resources for Synchronous Learning in Higher Education (IGI Global, 2019), pp. 255–278

J.M. Mbuva, Examining the effectiveness of online educational technological tools for teaching and learning and the challenges ahead. J. Higher Educ. Theory Pract. 15 (2), 113 (2015)

Google Scholar

S.N.M. Mohamad, M.A.M. Salleh, S. Salam, Factors affecting lecturer’s motivation in using online teaching tools. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 195 , 1778–1784 (2015)

Article Google Scholar

A.T. Hilliard, Global blended learning practices for teaching and learning, leadership and professional development. J. Int. Educ. Res. 11 (3), 179–188 (2015)

M. Moussavi, Y. Amannejad, M. Moshirpour, E. Marasco, L. Behjat, Importance of data analytics for improving teaching and learning methods, in Data Management and Analysis (Springer, Cham, 2020), pp. 91–101

P. Berking, S. Gallagher, Choosing a learning management system, in Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL) Co-Laboratories (2013), pp 40–62

R.J.M. Ventayen, K.L.A. Estira, M.J. De Guzman, C.M. Cabaluna, N.N. Espinosa, Usability evaluation of google classroom: basis for the adaptation of gsuite e-learning platform. Asia Pac. J. Educ. Arts Sci. 5 (1), 47–51 (2018)

B.N. Ilag, Introduction: microsoft teams, in Introducing Microsoft Teams (Apress, Berkeley, CA, 2018), pp. 1–42

A.S. Alqahtani, The use of Edmodo: its impact on learning and students’ attitudes towards it. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. 18 , 319–330 (2019)

J. Uziak, M.T. Oladiran, E. Lorencowicz, K. Becker, Students’ and instructor’s perspectives on the use of Blackboard Platform for delivering an engineering course. Electron. J. E-Learn. 16 (1), 1 (2018)

T. Makarchuk, V. Trofimov, S. Demchenko, Modeling the life cycle of the e-learning course using Moodle Cloud LMS, in Conferences of the Department Informatics , No. 1 (Publishing house Science and Economics Varna, 2019), pp. 62–71

N.L. Davis, M. Gough, L.L. Taylor, Online teaching: advantages, obstacles, and tools for getting it right. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 19 (3), 256–263 (2019)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, CMR Institute of Technology, Bangalore, 560037, India

Preethi Sheba Hepsiba Darius

School of Mechanical Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, 632014, India

Edison Gundabattini & Darius Gnanaraj Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Darius Gnanaraj Solomon .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Darius, P.S.H., Gundabattini, E. & Solomon, D.G. A Survey on the Effectiveness of Online Teaching–Learning Methods for University and College Students. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 102 , 1325–1334 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40031-021-00581-x

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2020

Accepted : 18 March 2021

Published : 05 April 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40031-021-00581-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Learning management

- Learning environment

- Teaching and learning

- Digital learning

- Collaborative learning

- Online learning

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

COVID-19’s impacts on the scope, effectiveness, and interaction characteristics of online learning: A social network analysis

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ JZ and YD are contributed equally to this work as first authors.

Affiliation School of Educational Information Technology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliations School of Educational Information Technology, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, Hangzhou Zhongce Vocational School Qiantang, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Roles Data curation, Writing – original draft

Roles Data curation

Roles Writing – original draft

Affiliation Faculty of Education, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] (JH); [email protected] (YZ)

- Junyi Zhang,

- Yigang Ding,

- Xinru Yang,

- Jinping Zhong,

- XinXin Qiu,

- Zhishan Zou,

- Yujie Xu,

- Xiunan Jin,

- Xiaomin Wu,

- Published: August 23, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016

- Reader Comments

The COVID-19 outbreak brought online learning to the forefront of education. Scholars have conducted many studies on online learning during the pandemic, but only a few have performed quantitative comparative analyses of students’ online learning behavior before and after the outbreak. We collected review data from China’s massive open online course platform called icourse.163 and performed social network analysis on 15 courses to explore courses’ interaction characteristics before, during, and after the COVID-19 pan-demic. Specifically, we focused on the following aspects: (1) variations in the scale of online learning amid COVID-19; (2a) the characteristics of online learning interaction during the pandemic; (2b) the characteristics of online learning interaction after the pandemic; and (3) differences in the interaction characteristics of social science courses and natural science courses. Results revealed that only a small number of courses witnessed an uptick in online interaction, suggesting that the pandemic’s role in promoting the scale of courses was not significant. During the pandemic, online learning interaction became more frequent among course network members whose interaction scale increased. After the pandemic, although the scale of interaction declined, online learning interaction became more effective. The scale and level of interaction in Electrodynamics (a natural science course) and Economics (a social science course) both rose during the pan-demic. However, long after the pandemic, the Economics course sustained online interaction whereas interaction in the Electrodynamics course steadily declined. This discrepancy could be due to the unique characteristics of natural science courses and social science courses.

Citation: Zhang J, Ding Y, Yang X, Zhong J, Qiu X, Zou Z, et al. (2022) COVID-19’s impacts on the scope, effectiveness, and interaction characteristics of online learning: A social network analysis. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0273016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016

Editor: Heng Luo, Central China Normal University, CHINA

Received: April 20, 2022; Accepted: July 29, 2022; Published: August 23, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Zhang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study were downloaded from https://www.icourse163.org/ and are now shared fully on Github ( https://github.com/zjyzhangjunyi/dataset-from-icourse163-for-SNA ). These data have no private information and can be used for academic research free of charge.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

The development of the mobile internet has spurred rapid advances in online learning, offering novel prospects for teaching and learning and a learning experience completely different from traditional instruction. Online learning harnesses the advantages of network technology and multimedia technology to transcend the boundaries of conventional education [ 1 ]. Online courses have become a popular learning mode owing to their flexibility and openness. During online learning, teachers and students are in different physical locations but interact in multiple ways (e.g., via online forum discussions and asynchronous group discussions). An analysis of online learning therefore calls for attention to students’ participation. Alqurashi [ 2 ] defined interaction in online learning as the process of constructing meaningful information and thought exchanges between more than two people; such interaction typically occurs between teachers and learners, learners and learners, and the course content and learners.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs), a 21st-century teaching mode, have greatly influenced global education. Data released by China’s Ministry of Education in 2020 show that the country ranks first globally in the number and scale of higher education MOOCs. The COVID-19 outbreak has further propelled this learning mode, with universities being urged to leverage MOOCs and other online resource platforms to respond to government’s “School’s Out, But Class’s On” policy [ 3 ]. Besides MOOCs, to reduce in-person gatherings and curb the spread of COVID-19, various online learning methods have since become ubiquitous [ 4 ]. Though Lederman asserted that the COVID-19 outbreak has positioned online learning technologies as the best way for teachers and students to obtain satisfactory learning experiences [ 5 ], it remains unclear whether the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged interaction in online learning, as interactions between students and others play key roles in academic performance and largely determine the quality of learning experiences [ 6 ]. Similarly, it is also unclear what impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the scale of online learning.

Social constructivism paints learning as a social phenomenon. As such, analyzing the social structures or patterns that emerge during the learning process can shed light on learning-based interaction [ 7 ]. Social network analysis helps to explain how a social network, rooted in interactions between learners and their peers, guides individuals’ behavior, emotions, and outcomes. This analytical approach is especially useful for evaluating interactive relationships between network members [ 8 ]. Mohammed cited social network analysis (SNA) as a method that can provide timely information about students, learning communities and interactive networks. SNA has been applied in numerous fields, including education, to identify the number and characteristics of interelement relationships. For example, Lee et al. also used SNA to explore the effects of blogs on peer relationships [ 7 ]. Therefore, adopting SNA to examine interactions in online learning communities during the COVID-19 pandemic can uncover potential issues with this online learning model.

Taking China’s icourse.163 MOOC platform as an example, we chose 15 courses with a large number of participants for SNA, focusing on learners’ interaction characteristics before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak. We visually assessed changes in the scale of network interaction before, during, and after the outbreak along with the characteristics of interaction in Gephi. Examining students’ interactions in different courses revealed distinct interactive network characteristics, the pandemic’s impact on online courses, and relevant suggestions. Findings are expected to promote effective interaction and deep learning among students in addition to serving as a reference for the development of other online learning communities.

2. Literature review and research questions

Interaction is deemed as central to the educational experience and is a major focus of research on online learning. Moore began to study the problem of interaction in distance education as early as 1989. He defined three core types of interaction: student–teacher, student–content, and student–student [ 9 ]. Lear et al. [ 10 ] described an interactivity/ community-process model of distance education: they specifically discussed the relationships between interactivity, community awareness, and engaging learners and found interactivity and community awareness to be correlated with learner engagement. Zulfikar et al. [ 11 ] suggested that discussions initiated by the students encourage more students’ engagement than discussions initiated by the instructors. It is most important to afford learners opportunities to interact purposefully with teachers, and improving the quality of learner interaction is crucial to fostering profound learning [ 12 ]. Interaction is an important way for learners to communicate and share information, and a key factor in the quality of online learning [ 13 ].

Timely feedback is the main component of online learning interaction. Woo and Reeves discovered that students often become frustrated when they fail to receive prompt feedback [ 14 ]. Shelley et al. conducted a three-year study of graduate and undergraduate students’ satisfaction with online learning at universities and found that interaction with educators and students is the main factor affecting satisfaction [ 15 ]. Teachers therefore need to provide students with scoring justification, support, and constructive criticism during online learning. Some researchers examined online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that most students preferred face-to-face learning rather than online learning due to obstacles faced online, such as a lack of motivation, limited teacher-student interaction, and a sense of isolation when learning in different times and spaces [ 16 , 17 ]. However, it can be reduced by enhancing the online interaction between teachers and students [ 18 ].

Research showed that interactions contributed to maintaining students’ motivation to continue learning [ 19 ]. Baber argued that interaction played a key role in students’ academic performance and influenced the quality of the online learning experience [ 20 ]. Hodges et al. maintained that well-designed online instruction can lead to unique teaching experiences [ 21 ]. Banna et al. mentioned that using discussion boards, chat sessions, blogs, wikis, and other tools could promote student interaction and improve participation in online courses [ 22 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Mahmood proposed a series of teaching strategies suitable for distance learning to improve its effectiveness [ 23 ]. Lapitan et al. devised an online strategy to ease the transition from traditional face-to-face instruction to online learning [ 24 ]. The preceding discussion suggests that online learning goes beyond simply providing learning resources; teachers should ideally design real-life activities to give learners more opportunities to participate.

As mentioned, COVID-19 has driven many scholars to explore the online learning environment. However, most have ignored the uniqueness of online learning during this time and have rarely compared pre- and post-pandemic online learning interaction. Taking China’s icourse.163 MOOC platform as an example, we chose 15 courses with a large number of participants for SNA, centering on student interaction before and after the pandemic. Gephi was used to visually analyze changes in the scale and characteristics of network interaction. The following questions were of particular interest:

- (1) Can the COVID-19 pandemic promote the expansion of online learning?

- (2a) What are the characteristics of online learning interaction during the pandemic?

- (2b) What are the characteristics of online learning interaction after the pandemic?

- (3) How do interaction characteristics differ between social science courses and natural science courses?

3. Methodology

3.1 research context.

We selected several courses with a large number of participants and extensive online interaction among hundreds of courses on the icourse.163 MOOC platform. These courses had been offered on the platform for at least three semesters, covering three periods (i.e., before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak). To eliminate the effects of shifts in irrelevant variables (e.g., course teaching activities), we chose several courses with similar teaching activities and compared them on multiple dimensions. All course content was taught online. The teachers of each course posted discussion threads related to learning topics; students were expected to reply via comments. Learners could exchange ideas freely in their responses in addition to asking questions and sharing their learning experiences. Teachers could answer students’ questions as well. Conversations in the comment area could partly compensate for a relative absence of online classroom interaction. Teacher–student interaction is conducive to the formation of a social network structure and enabled us to examine teachers’ and students’ learning behavior through SNA. The comment areas in these courses were intended for learners to construct knowledge via reciprocal communication. Meanwhile, by answering students’ questions, teachers could encourage them to reflect on their learning progress. These courses’ successive terms also spanned several phases of COVID-19, allowing us to ascertain the pandemic’s impact on online learning.

3.2 Data collection and preprocessing

To avoid interference from invalid or unclear data, the following criteria were applied to select representative courses: (1) generality (i.e., public courses and professional courses were chosen from different schools across China); (2) time validity (i.e., courses were held before during, and after the pandemic); and (3) notability (i.e., each course had at least 2,000 participants). We ultimately chose 15 courses across the social sciences and natural sciences (see Table 1 ). The coding is used to represent the course name.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t001

To discern courses’ evolution during the pandemic, we gathered data on three terms before, during, and after the COVID-19 outbreak in addition to obtaining data from two terms completed well before the pandemic and long after. Our final dataset comprised five sets of interactive data. Finally, we collected about 120,000 comments for SNA. Because each course had a different start time—in line with fluctuations in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in China and the opening dates of most colleges and universities—we divided our sample into five phases: well before the pandemic (Phase I); before the pandemic (Phase Ⅱ); during the pandemic (Phase Ⅲ); after the pandemic (Phase Ⅳ); and long after the pandemic (Phase Ⅴ). We sought to preserve consistent time spans to balance the amount of data in each period ( Fig 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g001

3.3 Instrumentation

Participants’ comments and “thumbs-up” behavior data were converted into a network structure and compared using social network analysis (SNA). Network analysis, according to M’Chirgui, is an effective tool for clarifying network relationships by employing sophisticated techniques [ 25 ]. Specifically, SNA can help explain the underlying relationships among team members and provide a better understanding of their internal processes. Yang and Tang used SNA to discuss the relationship between team structure and team performance [ 26 ]. Golbeck argued that SNA could improve the understanding of students’ learning processes and reveal learners’ and teachers’ role dynamics [ 27 ].

To analyze Question (1), the number of nodes and diameter in the generated network were deemed as indicators of changes in network size. Social networks are typically represented as graphs with nodes and degrees, and node count indicates the sample size [ 15 ]. Wellman et al. proposed that the larger the network scale, the greater the number of network members providing emotional support, goods, services, and companionship [ 28 ]. Jan’s study measured the network size by counting the nodes which represented students, lecturers, and tutors [ 29 ]. Similarly, network nodes in the present study indicated how many learners and teachers participated in the course, with more nodes indicating more participants. Furthermore, we investigated the network diameter, a structural feature of social networks, which is a common metric for measuring network size in SNA [ 30 ]. The network diameter refers to the longest path between any two nodes in the network. There has been evidence that a larger network diameter leads to greater spread of behavior [ 31 ]. Likewise, Gašević et al. found that larger networks were more likely to spread innovative ideas about educational technology when analyzing MOOC-related research citations [ 32 ]. Therefore, we employed node count and network diameter to measure the network’s spatial size and further explore the expansion characteristic of online courses. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t002

To address Question (2), a list of interactive analysis metrics in SNA were introduced to scrutinize learners’ interaction characteristics in online learning during and after the pandemic, as shown below:

- (1) The average degree reflects the density of the network by calculating the average number of connections for each node. As Rong and Xu suggested, the average degree of a network indicates how active its participants are [ 33 ]. According to Hu, a higher average degree implies that more students are interacting directly with each other in a learning context [ 34 ]. The present study inherited the concept of the average degree from these previous studies: the higher the average degree, the more frequent the interaction between individuals in the network.

- (2) Essentially, a weighted average degree in a network is calculated by multiplying each degree by its respective weight, and then taking the average. Bydžovská took the strength of the relationship into account when determining the weighted average degree [ 35 ]. By calculating friendship’s weighted value, Maroulis assessed peer achievement within a small-school reform [ 36 ]. Accordingly, we considered the number of interactions as the weight of the degree, with a higher average degree indicating more active interaction among learners.

- (3) Network density is the ratio between actual connections and potential connections in a network. The more connections group members have with each other, the higher the network density. In SNA, network density is similar to group cohesion, i.e., a network of more strong relationships is more cohesive [ 37 ]. Network density also reflects how much all members are connected together [ 38 ]. Therefore, we adopted network density to indicate the closeness among network members. Higher network density indicates more frequent interaction and closer communication among students.

- (4) Clustering coefficient describes local network attributes and indicates that two nodes in the network could be connected through adjacent nodes. The clustering coefficient measures users’ tendency to gather (cluster) with others in the network: the higher the clustering coefficient, the more frequently users communicate with other group members. We regarded this indicator as a reflection of the cohesiveness of the group [ 39 ].

- (5) In a network, the average path length is the average number of steps along the shortest paths between any two nodes. Oliveres has observed that when an average path length is small, the route from one node to another is shorter when graphed [ 40 ]. This is especially true in educational settings where students tend to become closer friends. So we consider that the smaller the average path length, the greater the possibility of interaction between individuals in the network.

- (6) A network with a large number of nodes, but whose average path length is surprisingly small, is known as the small-world effect [ 41 ]. A higher clustering coefficient and shorter average path length are important indicators of a small-world network: a shorter average path length enables the network to spread information faster and more accurately; a higher clustering coefficient can promote frequent knowledge exchange within the group while boosting the timeliness and accuracy of knowledge dissemination [ 42 ]. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t003

To analyze Question 3, we used the concept of closeness centrality, which determines how close a vertex is to others in the network. As Opsahl et al. explained, closeness centrality reveals how closely actors are coupled with their entire social network [ 43 ]. In order to analyze social network-based engineering education, Putnik et al. examined closeness centrality and found that it was significantly correlated with grades [ 38 ]. We used closeness centrality to measure the position of an individual in the network. Brief introduction of these indicators can be summarized in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t004

3.4 Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Academic Committee Office (ACO) of South China Normal University ( http://fzghb.scnu.edu.cn/ ), Guangzhou, China. Research data were collected from the open platform and analyzed anonymously. There are thus no privacy issues involved in this study.

4.1 COVID-19’s role in promoting the scale of online courses was not as important as expected

As shown in Fig 2 , the number of course participants and nodes are closely correlated with the pandemic’s trajectory. Because the number of participants in each course varied widely, we normalized the number of participants and nodes to more conveniently visualize course trends. Fig 2 depicts changes in the chosen courses’ number of participants and nodes before the pandemic (Phase II), during the pandemic (Phase III), and after the pandemic (Phase IV). The number of participants in most courses during the pandemic exceeded those before and after the pandemic. But the number of people who participate in interaction in some courses did not increase.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g002

In order to better analyze the trend of interaction scale in online courses before, during, and after the pandemic, the selected courses were categorized according to their scale change. When the number of participants increased (decreased) beyond 20% (statistical experience) and the diameter also increased (decreased), the course scale was determined to have increased (decreased); otherwise, no significant change was identified in the course’s interaction scale. Courses were subsequently divided into three categories: increased interaction scale, decreased interaction scale, and no significant change. Results appear in Table 5 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t005

From before the pandemic until it broke out, the interaction scale of five courses increased, accounting for 33.3% of the full sample; one course’s interaction scale declined, accounting for 6.7%. The interaction scale of nine courses decreased, accounting for 60%. The pandemic’s role in promoting online courses thus was not as important as anticipated, and most courses’ interaction scale did not change significantly throughout.

No courses displayed growing interaction scale after the pandemic: the interaction scale of nine courses fell, accounting for 60%; and the interaction scale of six courses did not shift significantly, accounting for 40%. Courses with an increased scale of interaction during the pandemic did not maintain an upward trend. On the contrary, the improvement in the pandemic caused learners’ enthusiasm for online learning to wane. We next analyzed several interaction metrics to further explore course interaction during different pandemic periods.

4.2 Characteristics of online learning interaction amid COVID-19

4.2.1 during the covid-19 pandemic, online learning interaction in some courses became more active..

Changes in course indicators with the growing interaction scale during the pandemic are presented in Fig 3 , including SS5, SS6, NS1, NS3, and NS8. The horizontal ordinate indicates the number of courses, with red color representing the rise of the indicator value on the vertical ordinate and blue representing the decline.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g003

Specifically: (1) The average degree and weighted average degree of the five course networks demonstrated an upward trend. The emergence of the pandemic promoted students’ enthusiasm; learners were more active in the interactive network. (2) Fig 3 shows that 3 courses had increased network density and 2 courses had decreased. The higher the network density, the more communication within the team. Even though the pandemic accelerated the interaction scale and frequency, the tightness between learners in some courses did not improve. (3) The clustering coefficient of social science courses rose whereas the clustering coefficient and small-world property of natural science courses fell. The higher the clustering coefficient and the small-world property, the better the relationship between adjacent nodes and the higher the cohesion [ 39 ]. (4) Most courses’ average path length increased as the interaction scale increased. However, when the average path length grew, adverse effects could manifest: communication between learners might be limited to a small group without multi-directional interaction.

When the pandemic emerged, the only declining network scale belonged to a natural science course (NS2). The change in each course index is pictured in Fig 4 . The abscissa indicates the size of the value, with larger values to the right. The red dot indicates the index value before the pandemic; the blue dot indicates its value during the pandemic. If the blue dot is to the right of the red dot, then the value of the index increased; otherwise, the index value declined. Only the weighted average degree of the course network increased. The average degree, network density decreased, indicating that network members were not active and that learners’ interaction degree and communication frequency lessened. Despite reduced learner interaction, the average path length was small and the connectivity between learners was adequate.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g004

4.2.2 After the COVID-19 pandemic, the scale decreased rapidly, but most course interaction was more effective.

Fig 5 shows the changes in various courses’ interaction indicators after the pandemic, including SS1, SS2, SS3, SS6, SS7, NS2, NS3, NS7, and NS8.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g005

Specifically: (1) The average degree and weighted average degree of most course networks decreased. The scope and intensity of interaction among network members declined rapidly, as did learners’ enthusiasm for communication. (2) The network density of seven courses also fell, indicating weaker connections between learners in most courses. (3) In addition, the clustering coefficient and small-world property of most course networks decreased, suggesting little possibility of small groups in the network. The scope of interaction between learners was not limited to a specific space, and the interaction objects had no significant tendencies. (4) Although the scale of course interaction became smaller in this phase, the average path length of members’ social networks shortened in nine courses. Its shorter average path length would expedite the spread of information within the network as well as communication and sharing among network members.

Fig 6 displays the evolution of course interaction indicators without significant changes in interaction scale after the pandemic, including SS4, SS5, NS1, NS4, NS5, and NS6.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g006

Specifically: (1) Some course members’ social networks exhibited an increase in the average and weighted average. In these cases, even though the course network’s scale did not continue to increase, communication among network members rose and interaction became more frequent and deeper than before. (2) Network density and average path length are indicators of social network density. The greater the network density, the denser the social network; the shorter the average path length, the more concentrated the communication among network members. However, at this phase, the average path length and network density in most courses had increased. Yet the network density remained small despite having risen ( Table 6 ). Even with more frequent learner interaction, connections remained distant and the social network was comparatively sparse.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t006

In summary, the scale of interaction did not change significantly overall. Nonetheless, some course members’ frequency and extent of interaction increased, and the relationships between network members became closer as well. In the study, we found it interesting that the interaction scale of Economics (a social science course) course and Electrodynamics (a natural science course) course expanded rapidly during the pandemic and retained their interaction scale thereafter. We next assessed these two courses to determine whether their level of interaction persisted after the pandemic.

4.3 Analyses of natural science courses and social science courses

4.3.1 analyses of the interaction characteristics of economics and electrodynamics..

Economics and Electrodynamics are social science courses and natural science courses, respectively. Members’ interaction within these courses was similar: the interaction scale increased significantly when COVID-19 broke out (Phase Ⅲ), and no significant changes emerged after the pandemic (Phase Ⅴ). We hence focused on course interaction long after the outbreak (Phase V) and compared changes across multiple indicators, as listed in Table 7 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.t007

As the pandemic continued to improve, the number of participants and the diameter long after the outbreak (Phase V) each declined for Economics compared with after the pandemic (Phase IV). The interaction scale decreased, but the interaction between learners was much deeper. Specifically: (1) The weighted average degree, network density, clustering coefficient, and small-world property each reflected upward trends. The pandemic therefore exerted a strong impact on this course. Interaction was well maintained even after the pandemic. The smaller network scale promoted members’ interaction and communication. (2) Compared with after the pandemic (Phase IV), members’ network density increased significantly, showing that relationships between learners were closer and that cohesion was improving. (3) At the same time, as the clustering coefficient and small-world property grew, network members demonstrated strong small-group characteristics: the communication between them was deepening and their enthusiasm for interaction was higher. (4) Long after the COVID-19 outbreak (Phase V), the average path length was reduced compared with previous terms, knowledge flowed more quickly among network members, and the degree of interaction gradually deepened.

The average degree, weighted average degree, network density, clustering coefficient, and small-world property of Electrodynamics all decreased long after the COVID-19 outbreak (Phase V) and were lower than during the outbreak (Phase Ⅲ). The level of learner interaction therefore gradually declined long after the outbreak (Phase V), and connections between learners were no longer active. Although the pandemic increased course members’ extent of interaction, this rise was merely temporary: students’ enthusiasm for learning waned rapidly and their interaction decreased after the pandemic (Phase IV). To further analyze the interaction characteristics of course members in Economics and Electrodynamics, we evaluated the closeness centrality of their social networks, as shown in section 4.3.2.

4.3.2 Analysis of the closeness centrality of Economics and Electrodynamics.

The change in the closeness centrality of social networks in Economics was small, and no sharp upward trend appeared during the pandemic outbreak, as shown in Fig 7 . The emergence of COVID-19 apparently fostered learners’ interaction in Economics albeit without a significant impact. The closeness centrality changed in Electrodynamics varied from that of Economics: upon the COVID-19 outbreak, closeness centrality was significantly different from other semesters. Communication between learners was closer and interaction was more effective. Electrodynamics course members’ social network proximity decreased rapidly after the pandemic. Learners’ communication lessened. In general, Economics course showed better interaction before the outbreak and was less affected by the pandemic; Electrodynamics course was more affected by the pandemic and showed different interaction characteristics at different periods of the pandemic.

(Note: "****" indicates the significant distinction in closeness centrality between the two periods, otherwise no significant distinction).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273016.g007

5. Discussion

We referred to discussion forums from several courses on the icourse.163 MOOC platform to compare online learning before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic via SNA and to delineate the pandemic’s effects on online courses. Only 33.3% of courses in our sample increased in terms of interaction during the pandemic; the scale of interaction did not rise in any courses thereafter. When the courses scale rose, the scope and frequency of interaction showed upward trends during the pandemic; and the clustering coefficient of natural science courses and social science courses differed: the coefficient for social science courses tended to rise whereas that for natural science courses generally declined. When the pandemic broke out, the interaction scale of a single natural science course decreased along with its interaction scope and frequency. The amount of interaction in most courses shrank rapidly during the pandemic and network members were not as active as they had been before. However, after the pandemic, some courses saw declining interaction but greater communication between members; interaction also became more frequent and deeper than before.

5.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the scale of interaction increased in only a few courses

The pandemic outbreak led to a rapid increase in the number of participants in most courses; however, the change in network scale was not significant. The scale of online interaction expanded swiftly in only a few courses; in others, the scale either did not change significantly or displayed a downward trend. After the pandemic, the interaction scale in most courses decreased quickly; the same pattern applied to communication between network members. Learners’ enthusiasm for online interaction reduced as the circumstances of the pandemic improved—potentially because, during the pandemic, China’s Ministry of Education declared “School’s Out, But Class’s On” policy. Major colleges and universities were encouraged to use the Internet and informational resources to provide learning support, hence the sudden increase in the number of participants and interaction in online courses [ 46 ]. After the pandemic, students’ enthusiasm for online learning gradually weakened, presumably due to easing of the pandemic [ 47 ]. More activities also transitioned from online to offline, which tempered learners’ online discussion. Research has shown that long-term online learning can even bore students [ 48 ].