Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![research abstract model “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![research abstract model “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![research abstract model “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

What this handout is about

This handout provides definitions and examples of the two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. It also provides guidelines for constructing an abstract and general tips for you to keep in mind when drafting. Finally, it includes a few examples of abstracts broken down into their component parts.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a self-contained, short, and powerful statement that describes a larger work. Components vary according to discipline. An abstract of a social science or scientific work may contain the scope, purpose, results, and contents of the work. An abstract of a humanities work may contain the thesis, background, and conclusion of the larger work. An abstract is not a review, nor does it evaluate the work being abstracted. While it contains key words found in the larger work, the abstract is an original document rather than an excerpted passage.

Why write an abstract?

You may write an abstract for various reasons. The two most important are selection and indexing. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in a longer work to quickly decide whether it is worth their time to read it. Also, many online databases use abstracts to index larger works. Therefore, abstracts should contain keywords and phrases that allow for easy searching.

Say you are beginning a research project on how Brazilian newspapers helped Brazil’s ultra-liberal president Luiz Ignácio da Silva wrest power from the traditional, conservative power base. A good first place to start your research is to search Dissertation Abstracts International for all dissertations that deal with the interaction between newspapers and politics. “Newspapers and politics” returned 569 hits. A more selective search of “newspapers and Brazil” returned 22 hits. That is still a fair number of dissertations. Titles can sometimes help winnow the field, but many titles are not very descriptive. For example, one dissertation is titled “Rhetoric and Riot in Rio de Janeiro.” It is unclear from the title what this dissertation has to do with newspapers in Brazil. One option would be to download or order the entire dissertation on the chance that it might speak specifically to the topic. A better option is to read the abstract. In this case, the abstract reveals the main focus of the dissertation:

This dissertation examines the role of newspaper editors in the political turmoil and strife that characterized late First Empire Rio de Janeiro (1827-1831). Newspaper editors and their journals helped change the political culture of late First Empire Rio de Janeiro by involving the people in the discussion of state. This change in political culture is apparent in Emperor Pedro I’s gradual loss of control over the mechanisms of power. As the newspapers became more numerous and powerful, the Emperor lost his legitimacy in the eyes of the people. To explore the role of the newspapers in the political events of the late First Empire, this dissertation analyzes all available newspapers published in Rio de Janeiro from 1827 to 1831. Newspapers and their editors were leading forces in the effort to remove power from the hands of the ruling elite and place it under the control of the people. In the process, newspapers helped change how politics operated in the constitutional monarchy of Brazil.

From this abstract you now know that although the dissertation has nothing to do with modern Brazilian politics, it does cover the role of newspapers in changing traditional mechanisms of power. After reading the abstract, you can make an informed judgment about whether the dissertation would be worthwhile to read.

Besides selection, the other main purpose of the abstract is for indexing. Most article databases in the online catalog of the library enable you to search abstracts. This allows for quick retrieval by users and limits the extraneous items recalled by a “full-text” search. However, for an abstract to be useful in an online retrieval system, it must incorporate the key terms that a potential researcher would use to search. For example, if you search Dissertation Abstracts International using the keywords “France” “revolution” and “politics,” the search engine would search through all the abstracts in the database that included those three words. Without an abstract, the search engine would be forced to search titles, which, as we have seen, may not be fruitful, or else search the full text. It’s likely that a lot more than 60 dissertations have been written with those three words somewhere in the body of the entire work. By incorporating keywords into the abstract, the author emphasizes the central topics of the work and gives prospective readers enough information to make an informed judgment about the applicability of the work.

When do people write abstracts?

- when submitting articles to journals, especially online journals

- when applying for research grants

- when writing a book proposal

- when completing the Ph.D. dissertation or M.A. thesis

- when writing a proposal for a conference paper

- when writing a proposal for a book chapter

Most often, the author of the entire work (or prospective work) writes the abstract. However, there are professional abstracting services that hire writers to draft abstracts of other people’s work. In a work with multiple authors, the first author usually writes the abstract. Undergraduates are sometimes asked to draft abstracts of books/articles for classmates who have not read the larger work.

Types of abstracts

There are two types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. They have different aims, so as a consequence they have different components and styles. There is also a third type called critical, but it is rarely used. If you want to find out more about writing a critique or a review of a work, see the UNC Writing Center handout on writing a literature review . If you are unsure which type of abstract you should write, ask your instructor (if the abstract is for a class) or read other abstracts in your field or in the journal where you are submitting your article.

Descriptive abstracts

A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract describes the work being abstracted. Some people consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short—100 words or less.

Informative abstracts

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the writer presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the complete article/paper/book. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract (purpose, methods, scope) but also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is rarely more than 10% of the length of the entire work. In the case of a longer work, it may be much less.

Here are examples of a descriptive and an informative abstract of this handout on abstracts . Descriptive abstract:

The two most common abstract types—descriptive and informative—are described and examples of each are provided.

Informative abstract:

Abstracts present the essential elements of a longer work in a short and powerful statement. The purpose of an abstract is to provide prospective readers the opportunity to judge the relevance of the longer work to their projects. Abstracts also include the key terms found in the longer work and the purpose and methods of the research. Authors abstract various longer works, including book proposals, dissertations, and online journal articles. There are two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. A descriptive abstract briefly describes the longer work, while an informative abstract presents all the main arguments and important results. This handout provides examples of various types of abstracts and instructions on how to construct one.

Which type should I use?

Your best bet in this case is to ask your instructor or refer to the instructions provided by the publisher. You can also make a guess based on the length allowed; i.e., 100-120 words = descriptive; 250+ words = informative.

How do I write an abstract?

The format of your abstract will depend on the work being abstracted. An abstract of a scientific research paper will contain elements not found in an abstract of a literature article, and vice versa. However, all abstracts share several mandatory components, and there are also some optional parts that you can decide to include or not. When preparing to draft your abstract, keep the following key process elements in mind:

- Reason for writing: What is the importance of the research? Why would a reader be interested in the larger work?

- Problem: What problem does this work attempt to solve? What is the scope of the project? What is the main argument/thesis/claim?

- Methodology: An abstract of a scientific work may include specific models or approaches used in the larger study. Other abstracts may describe the types of evidence used in the research.

- Results: Again, an abstract of a scientific work may include specific data that indicates the results of the project. Other abstracts may discuss the findings in a more general way.

- Implications: What changes should be implemented as a result of the findings of the work? How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic?

(This list of elements is adapted with permission from Philip Koopman, “How to Write an Abstract.” )

All abstracts include:

- A full citation of the source, preceding the abstract.

- The most important information first.

- The same type and style of language found in the original, including technical language.

- Key words and phrases that quickly identify the content and focus of the work.

- Clear, concise, and powerful language.

Abstracts may include:

- The thesis of the work, usually in the first sentence.

- Background information that places the work in the larger body of literature.

- The same chronological structure as the original work.

How not to write an abstract:

- Do not refer extensively to other works.

- Do not add information not contained in the original work.

- Do not define terms.

If you are abstracting your own writing

When abstracting your own work, it may be difficult to condense a piece of writing that you have agonized over for weeks (or months, or even years) into a 250-word statement. There are some tricks that you could use to make it easier, however.

Reverse outlining:

This technique is commonly used when you are having trouble organizing your own writing. The process involves writing down the main idea of each paragraph on a separate piece of paper– see our short video . For the purposes of writing an abstract, try grouping the main ideas of each section of the paper into a single sentence. Practice grouping ideas using webbing or color coding .

For a scientific paper, you may have sections titled Purpose, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each one of these sections will be longer than one paragraph, but each is grouped around a central idea. Use reverse outlining to discover the central idea in each section and then distill these ideas into one statement.

Cut and paste:

To create a first draft of an abstract of your own work, you can read through the entire paper and cut and paste sentences that capture key passages. This technique is useful for social science research with findings that cannot be encapsulated by neat numbers or concrete results. A well-written humanities draft will have a clear and direct thesis statement and informative topic sentences for paragraphs or sections. Isolate these sentences in a separate document and work on revising them into a unified paragraph.

If you are abstracting someone else’s writing

When abstracting something you have not written, you cannot summarize key ideas just by cutting and pasting. Instead, you must determine what a prospective reader would want to know about the work. There are a few techniques that will help you in this process:

Identify key terms:

Search through the entire document for key terms that identify the purpose, scope, and methods of the work. Pay close attention to the Introduction (or Purpose) and the Conclusion (or Discussion). These sections should contain all the main ideas and key terms in the paper. When writing the abstract, be sure to incorporate the key terms.

Highlight key phrases and sentences:

Instead of cutting and pasting the actual words, try highlighting sentences or phrases that appear to be central to the work. Then, in a separate document, rewrite the sentences and phrases in your own words.

Don’t look back:

After reading the entire work, put it aside and write a paragraph about the work without referring to it. In the first draft, you may not remember all the key terms or the results, but you will remember what the main point of the work was. Remember not to include any information you did not get from the work being abstracted.

Revise, revise, revise

No matter what type of abstract you are writing, or whether you are abstracting your own work or someone else’s, the most important step in writing an abstract is to revise early and often. When revising, delete all extraneous words and incorporate meaningful and powerful words. The idea is to be as clear and complete as possible in the shortest possible amount of space. The Word Count feature of Microsoft Word can help you keep track of how long your abstract is and help you hit your target length.

Example 1: Humanities abstract

Kenneth Tait Andrews, “‘Freedom is a constant struggle’: The dynamics and consequences of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1984” Ph.D. State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1997 DAI-A 59/02, p. 620, Aug 1998

This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so. The time period studied includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies. Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports. This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Now let’s break down this abstract into its component parts to see how the author has distilled his entire dissertation into a ~200 word abstract.

What the dissertation does This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so.

How the dissertation does it The time period studied in this dissertation includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies.

What materials are used Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports.

Conclusion This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to movement demands and the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Keywords social movements Civil Rights Movement Mississippi voting rights desegregation

Example 2: Science Abstract

Luis Lehner, “Gravitational radiation from black hole spacetimes” Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 1998 DAI-B 59/06, p. 2797, Dec 1998

The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search for and analysis of detected signals. The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm. This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

This science abstract covers much of the same ground as the humanities one, but it asks slightly different questions.

Why do this study The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search and analysis of the detected signals.

What the study does The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm.

Results This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

Keywords gravitational radiation (GR) spacetimes black holes

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2009. Writing Your Journal Article in Twelve Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

Koopman, Philip. 1997. “How to Write an Abstract.” Carnegie Mellon University. October 1997. http://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html .

Lancaster, F.W. 2003. Indexing And Abstracting in Theory and Practice , 3rd ed. London: Facet Publishing.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

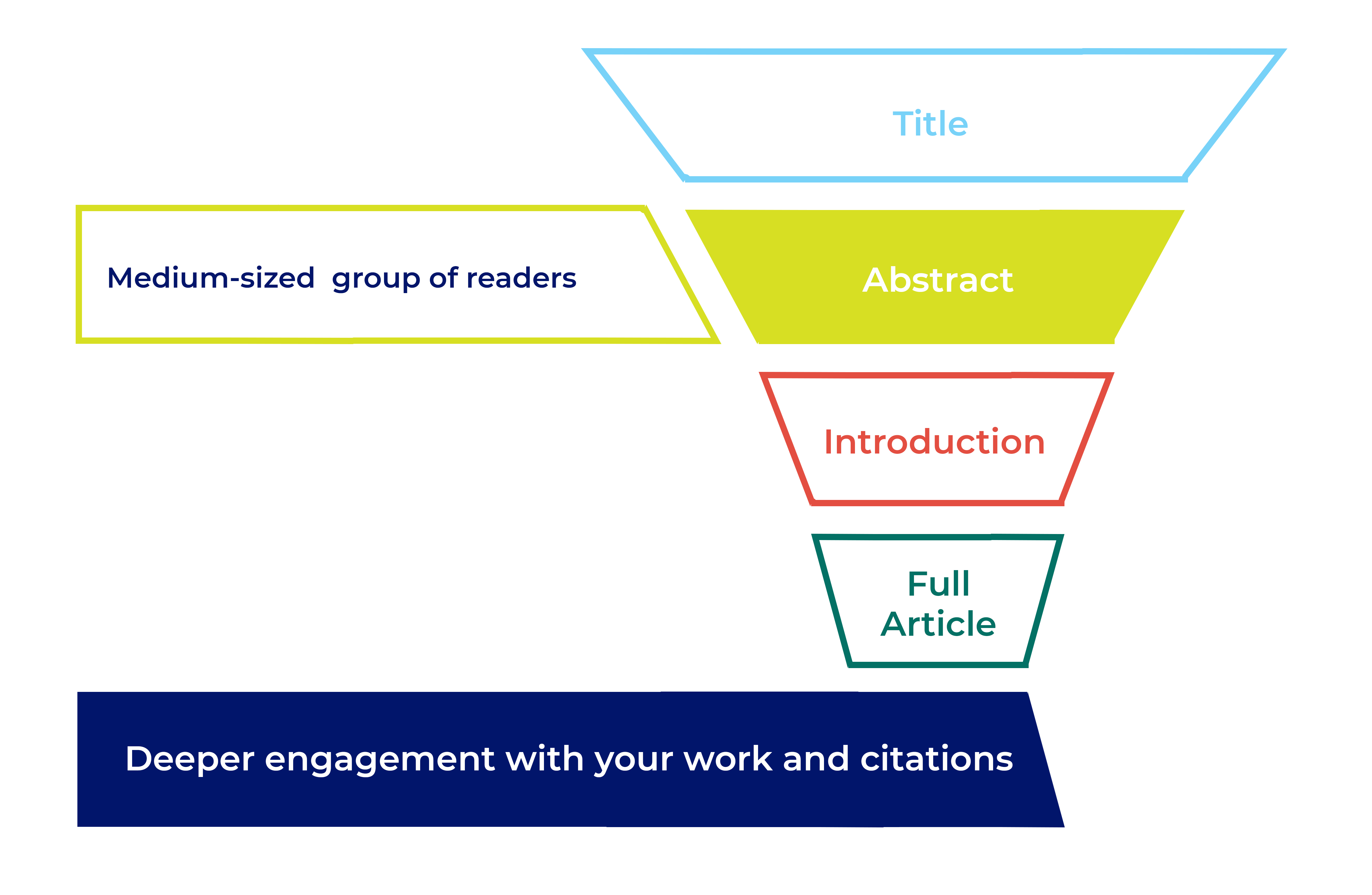

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Abstract

Research Paper Abstract is a brief summary of a research pape r that describes the study’s purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions . It is often the first section of the paper that readers encounter, and its purpose is to provide a concise and accurate overview of the paper’s content. The typical length of an abstract is usually around 150-250 words, and it should be written in a concise and clear manner.

Research Paper Abstract Structure

The structure of a research paper abstract usually includes the following elements:

- Background or Introduction: Briefly describe the problem or research question that the study addresses.

- Methods : Explain the methodology used to conduct the study, including the participants, materials, and procedures.

- Results : Summarize the main findings of the study, including statistical analyses and key outcomes.

- Conclusions : Discuss the implications of the study’s findings and their significance for the field, as well as any limitations or future directions for research.

- Keywords : List a few keywords that describe the main topics or themes of the research.

How to Write Research Paper Abstract

Here are the steps to follow when writing a research paper abstract:

- Start by reading your paper: Before you write an abstract, you should have a complete understanding of your paper. Read through the paper carefully, making sure you understand the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the key components : Identify the key components of your paper, such as the research question, methods used, results obtained, and conclusion reached.

- Write a draft: Write a draft of your abstract, using concise and clear language. Make sure to include all the important information, but keep it short and to the point. A good rule of thumb is to keep your abstract between 150-250 words.

- Use clear and concise language : Use clear and concise language to explain the purpose of your study, the methods used, the results obtained, and the conclusions drawn.

- Emphasize your findings: Emphasize your findings in the abstract, highlighting the key results and the significance of your study.

- Revise and edit: Once you have a draft, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free from errors.

- Check the formatting: Finally, check the formatting of your abstract to make sure it meets the requirements of the journal or conference where you plan to submit it.

Research Paper Abstract Examples

Research Paper Abstract Examples could be following:

Title : “The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Treating Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in treating anxiety disorders. Through the analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials, we found that CBT is a highly effective treatment for anxiety disorders, with large effect sizes across a range of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Our findings support the use of CBT as a first-line treatment for anxiety disorders and highlight the importance of further research to identify the mechanisms underlying its effectiveness.

Title : “Exploring the Role of Parental Involvement in Children’s Education: A Qualitative Study”

Abstract : This qualitative study explores the role of parental involvement in children’s education. Through in-depth interviews with 20 parents of children in elementary school, we found that parental involvement takes many forms, including volunteering in the classroom, helping with homework, and communicating with teachers. We also found that parental involvement is influenced by a range of factors, including parent and child characteristics, school culture, and socio-economic status. Our findings suggest that schools and educators should prioritize building strong partnerships with parents to support children’s academic success.

Title : “The Impact of Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This paper presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature on the impact of exercise on cognitive function in older adults. Through the analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials, we found that exercise is associated with significant improvements in cognitive function, particularly in the domains of executive function and attention. Our findings highlight the potential of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention to support cognitive health in older adults.

When to Write Research Paper Abstract

The abstract of a research paper should typically be written after you have completed the main body of the paper. This is because the abstract is intended to provide a brief summary of the key points and findings of the research, and you can’t do that until you have completed the research and written about it in detail.

Once you have completed your research paper, you can begin writing your abstract. It is important to remember that the abstract should be a concise summary of your research paper, and should be written in a way that is easy to understand for readers who may not have expertise in your specific area of research.

Purpose of Research Paper Abstract

The purpose of a research paper abstract is to provide a concise summary of the key points and findings of a research paper. It is typically a brief paragraph or two that appears at the beginning of the paper, before the introduction, and is intended to give readers a quick overview of the paper’s content.

The abstract should include a brief statement of the research problem, the methods used to investigate the problem, the key results and findings, and the main conclusions and implications of the research. It should be written in a clear and concise manner, avoiding jargon and technical language, and should be understandable to a broad audience.

The abstract serves as a way to quickly and easily communicate the main points of a research paper to potential readers, such as academics, researchers, and students, who may be looking for information on a particular topic. It can also help researchers determine whether a paper is relevant to their own research interests and whether they should read the full paper.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Magnum Proofreading Services

- Jake Magnum

- Jan 2, 2021

Writing an Abstract for a Research Paper: Guidelines, Examples, and Templates

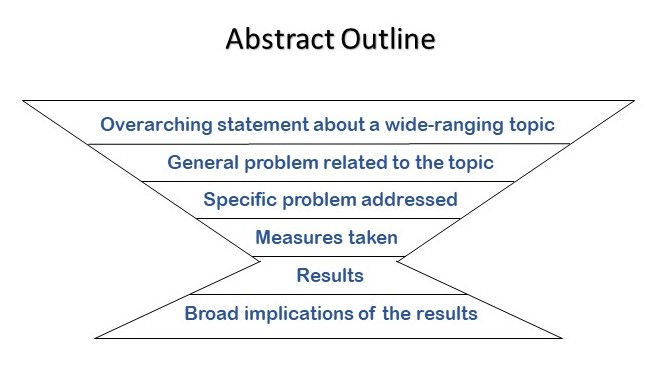

There are six steps to writing a standard abstract. (1) Begin with a broad statement about your topic. Then, (2) state the problem or knowledge gap related to this topic that your study explores. After that, (3) describe what specific aspect of this problem you investigated, and (4) briefly explain how you went about doing this. After that, (5) describe the most meaningful outcome(s) of your study. Finally, (6) close your abstract by explaining the broad implication(s) of your findings.

In this article, I present step-by-step guidelines for writing an abstract for an academic paper. These guidelines are fo llowed by an example of a full abstract that follows these guidelines and a few fill-in-the-blank templates that you can use to write your own abstract.

Guidelines for Writing an Abstract

The basic structure of an abstract is illustrated below.

A standard abstract starts with a very general statement and becomes more specific with each sentence that follows until once again making a broad statement about the study’s implications at the end. Altogether, a standard abstract has six functions, which are described in detail below.

Start by making a broad statement about your topic.

The first sentence of your abstract should briefly describe a problem that is of interest to your readers. When writing this first sentence, you should think about who comprises your target audience and use terms that will appeal to this audience. If your opening sentence is too broad, it might lose the attention of potential readers because they will not know if your study is relevant to them.

Too broad : Maintaining an ideal workplace environment has a positive effect on employees.

The sentence above is so broad that it will not grab the reader’s attention. While it gives the reader some idea of the area of study, it doesn’t provide any details about the author’s topic within their research area. This can be fixed by inserting some keywords related to the topic (these are underlined in the revised example below).

Improved : Keeping the workplace environment at an ideal temperature positively affects the overall health of employees.

The revised sentence is much better, as it expresses two points about the research topic—namely, (i) what aspect of workplace environment was studied, (ii) what aspect of employees was observed. The mention of these aspects of the research will draw the attention of readers who are interested in them.

Describe the general problem that your paper addresses.

After describing your topic in the first sentence, you can then explain what aspect of this topic has motivated your research. Often, authors use this part of the abstract to describe the research gap that they identified and aimed to fill. These types of sentences are often characterized by the use of words such as “however,” “although,” “despite,” and so on.

However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking.

The above example is typical of a sentence describing the problem that a study intends to tackle. The author has noticed that there is a gap in the research, and they briefly explain this gap here.

Although it has been established that quantity and quality of sleep can affect different types of task performance and personal health, the interactions between sleep habits and workplace behaviors have received very little attention.

The example above illustrates a case in which the author has accomplished two tasks with one sentence. The first part of the sentence (up until the comma) mentions the general topic that the research fits into, while the second part (after the comma) describes the general problem that the research addresses.

Express the specific problem investigated in your paper.

After describing the general problem that motivated your research, the next sentence should express the specific aspect of the problem that you investigated. Sentences of this type are often indicated by the use of phrases like “the purpose of this research is to,” “this paper is intended to,” or “this work aims to.”

Uninformative : However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking. The present article aimed to provide new insights into the relationship between workplace bullying and absenteeism .

The second sentence in the above example is a mere rewording of the first sentence. As such, it adds nothing to the abstract. The second sentence should be more specific than the preceding one.

Improved : However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking. The present article aimed to define various subtypes of workplace bullying and determine which subtypes tend to lead to absenteeism .

The second sentence of this passage is much more informative than in the previous example. This sentence lets the reader know exactly what they can expect from the full research article.

Explain how you attempted to resolve your study’s specific problem.

In this part of your abstract, you should attempt to describe your study’s methodology in one or two sentences. As such, you must be sure to include only the most important information about your method. At the same time, you must also be careful not to be too vague.

Too vague : We conducted multiple tests to examine changes in various factors related to well-being.

This description of the methodology is too vague. Instead of merely mentioning “tests” and “factors,” the author should note which specific tests were run and which factors were assessed.

Improved : Using data from BHIP completers, we conducted multiple one-way multivariate analyses of variance and follow-up univariate t-tests to examine changes in physical and mental health, stress, energy levels, social satisfaction, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

This sentence is very well-written. It packs a lot of specific information about the method into a single sentence. Also, it does not describe more details than are needed for an abstract.

Briefly tell the reader what you found by carrying out your study.

This is the most important part of the abstract—the other sentences in the abstract are there to explain why this one is relevant. When writing this sentence, imagine that someone has asked you, “What did you find in your research?” and that you need to answer them in one or two sentences.

Too vague : Consistently poor sleepers had more health risks and medical conditions than consistently optimal sleepers.

This sentence is okay, but it would be helpful to let the reader know which health risks and medical conditions were related to poor sleeping habits.

Improved : Consistently poor sleepers were more likely than consistently optimal sleepers to suffer from chronic abdominal pain, and they were at a higher risk for diabetes and heart disease.

This sentence is better, as the specific health conditions are named.

Finally, describe the major implication(s) of your study.

Most abstracts end with a short sentence that explains the main takeaway(s) that you want your audience to gain from reading your paper. Often, this sentence is addressed to people in power (e.g., employers, policymakers), and it recommends a course of action that such people should take based on the results.

Too broad : Employers may wish to make use of strategies that increase employee health.

This sentence is too broad to be useful. It does not give employers a starting point to implement a change.

Improved : Employers may wish to incorporate sleep education initiatives as part of their overall health and wellness strategies.

This sentence is better than the original, as it provides employers with a starting point—specifically, it invites employers to look up information on sleep education programs.

Abstract Example

The abstract produced here is from a paper published in Electronic Commerce Research and Applications . I have made slight alterations to the abstract so that this example fits the guidelines given in this article.

(1) Gamification can strengthen enjoyment and productivity in the workplace. (2) Despite this, research on gamification in the work context is still limited. (3) In this study, we investigated the effect of gamification on the workplace enjoyment and productivity of employees by comparing employees with leadership responsibilities to those without leadership responsibilities. (4) Work-related tasks were gamified using the habit-tracking game Habitica, and data from 114 employees were gathered using an online survey. (5) The results illustrated that employees without leadership responsibilities used work gamification as a trigger for self-motivation, whereas employees with leadership responsibilities used it to improve their health. (6) Work gamification positively affected work enjoyment for both types of employees and positively affected productivity for employees with leadership responsibilities. (7) Our results underline the importance of taking work-related variables into account when researching work gamification.

In Sentence (1), the author makes a broad statement about their topic. Notice how the nouns used (“gamification,” “enjoyment,” “productivity”) are quite general while still indicating the focus of the paper. The author uses Sentence (2) to very briefly state the problem that the research will address.

In Sentence (3), the author explains what specific aspects of the problem mentioned in Sentence (2) will be explored in the present work. Notice that the mention of leadership responsibilities makes Sentence (3) more specific than Sentence (2). Sentence (4) gets even more specific, naming the specific tools used to gather data and the number of participants.

Sentences (5) and (6) are similar, with each sentence describing one of the study’s main findings. Then, suddenly, the scope of the abstract becomes quite broad again in Sentence (7), which mentions “work-related variables” instead of a specific variable and “researching” instead of a specific kind of research.

Abstract Templates

Copy and paste any of the paragraphs below into a word processor. Then insert the appropriate information to produce an abstract for your research paper.

Template #1

Researchers have established that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . However, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The goal of this paper is to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . The achieve this goal, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . We found that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

Template #2

It is well-understood that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . Despite this, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The current research aims to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . To accomplish this, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . It was discovered that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

Template #3

Extensive research indicates that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . Nevertheless, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The present work is intended to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . To this end, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . The results revealed that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

- How to Write an Abstract

Related Posts

How to Write a Research Paper in English: A Guide for Non-native Speakers

How to Write an Abstract Quickly

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

Well explained! I have given you a credit

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.53(2); Apr-Jun 2011

How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation

Chittaranjan andrade.

Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Abstracts of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of this paper is the young researcher; however, authors with all levels of experience may find useful ideas in the paper.

INTRODUCTION

This paper is the third in a series on manuscript writing skills, published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry . Earlier articles offered suggestions on how to write a good case report,[ 1 ] and how to read, write, or review a paper on randomized controlled trials.[ 2 , 3 ] The present paper examines how authors may write a good abstract when preparing their manuscript for a scientific journal or conference presentation. Although the primary target of this paper is the young researcher, it is likely that authors with all levels of experience will find at least a few ideas that may be useful in their future efforts.

The abstract of a paper is the only part of the paper that is published in conference proceedings. The abstract is the only part of the paper that a potential referee sees when he is invited by an editor to review a manuscript. The abstract is the only part of the paper that readers see when they search through electronic databases such as PubMed. Finally, most readers will acknowledge, with a chuckle, that when they leaf through the hard copy of a journal, they look at only the titles of the contained papers. If a title interests them, they glance through the abstract of that paper. Only a dedicated reader will peruse the contents of the paper, and then, most often only the introduction and discussion sections. Only a reader with a very specific interest in the subject of the paper, and a need to understand it thoroughly, will read the entire paper.

Thus, for the vast majority of readers, the paper does not exist beyond its abstract. For the referees, and the few readers who wish to read beyond the abstract, the abstract sets the tone for the rest of the paper. It is therefore the duty of the author to ensure that the abstract is properly representative of the entire paper. For this, the abstract must have some general qualities. These are listed in Table 1 .

General qualities of a good abstract

SECTIONS OF AN ABSTRACT

Although some journals still publish abstracts that are written as free-flowing paragraphs, most journals require abstracts to conform to a formal structure within a word count of, usually, 200–250 words. The usual sections defined in a structured abstract are the Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions; other headings with similar meanings may be used (eg, Introduction in place of Background or Findings in place of Results). Some journals include additional sections, such as Objectives (between Background and Methods) and Limitations (at the end of the abstract). In the rest of this paper, issues related to the contents of each section will be examined in turn.

This section should be the shortest part of the abstract and should very briefly outline the following information:

- What is already known about the subject, related to the paper in question

- What is not known about the subject and hence what the study intended to examine (or what the paper seeks to present)

In most cases, the background can be framed in just 2–3 sentences, with each sentence describing a different aspect of the information referred to above; sometimes, even a single sentence may suffice. The purpose of the background, as the word itself indicates, is to provide the reader with a background to the study, and hence to smoothly lead into a description of the methods employed in the investigation.

Some authors publish papers the abstracts of which contain a lengthy background section. There are some situations, perhaps, where this may be justified. In most cases, however, a longer background section means that less space remains for the presentation of the results. This is unfortunate because the reader is interested in the paper because of its findings, and not because of its background.

A wide variety of acceptably composed backgrounds is provided in Table 2 ; most of these have been adapted from actual papers.[ 4 – 9 ] Readers may wish to compare the content in Table 2 with the original abstracts to see how the adaptations possibly improve on the originals. Note that, in the interest of brevity, unnecessary content is avoided. For instance, in Example 1 there is no need to state “The antidepressant efficacy of desvenlafaxine (DV), a dual-acting antidepressant drug , has been established…” (the unnecessary content is italicized).

Examples of the background section of an abstract

The methods section is usually the second-longest section in the abstract. It should contain enough information to enable the reader to understand what was done, and how. Table 3 lists important questions to which the methods section should provide brief answers.

Questions regarding which information should ideally be available in the methods section of an abstract

Carelessly written methods sections lack information about important issues such as sample size, numbers of patients in different groups, doses of medications, and duration of the study. Readers have only to flip through the pages of a randomly selected journal to realize how common such carelessness is.

Table 4 presents examples of the contents of accept-ably written methods sections, modified from actual publications.[ 10 , 11 ] Readers are invited to take special note of the first sentence of each example in Table 4 ; each is packed with detail, illustrating how to convey the maximum quantity of information with maximum economy of word count.

Examples of the methods section of an abstract

The results section is the most important part of the abstract and nothing should compromise its range and quality. This is because readers who peruse an abstract do so to learn about the findings of the study. The results section should therefore be the longest part of the abstract and should contain as much detail about the findings as the journal word count permits. For example, it is bad writing to state “Response rates differed significantly between diabetic and nondiabetic patients.” A better sentence is “The response rate was higher in nondiabetic than in diabetic patients (49% vs 30%, respectively; P <0.01).”

Important information that the results should present is indicated in Table 5 . Examples of acceptably written abstracts are presented in Table 6 ; one of these has been modified from an actual publication.[ 11 ] Note that the first example is rather narrative in style, whereas the second example is packed with data.

Information that the results section of the abstract should ideally present

Examples of the results section of an abstract

CONCLUSIONS

This section should contain the most important take-home message of the study, expressed in a few precisely worded sentences. Usually, the finding highlighted here relates to the primary outcome measure; however, other important or unexpected findings should also be mentioned. It is also customary, but not essential, for the authors to express an opinion about the theoretical or practical implications of the findings, or the importance of their findings for the field. Thus, the conclusions may contain three elements:

- The primary take-home message

- The additional findings of importance

- The perspective

Despite its necessary brevity, this section has the most impact on the average reader because readers generally trust authors and take their assertions at face value. For this reason, the conclusions should also be scrupulously honest; and authors should not claim more than their data demonstrate. Hypothetical examples of the conclusions section of an abstract are presented in Table 7 .

Examples of the conclusions section of an abstract

MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS

Citation of references anywhere within an abstract is almost invariably inappropriate. Other examples of unnecessary content in an abstract are listed in Table 8 .

Examples of unnecessary content in a abstract

It goes without saying that whatever is present in the abstract must also be present in the text. Likewise, whatever errors should not be made in the text should not appear in the abstract (eg, mistaking association for causality).

As already mentioned, the abstract is the only part of the paper that the vast majority of readers see. Therefore, it is critically important for authors to ensure that their enthusiasm or bias does not deceive the reader; unjustified speculations could be even more harmful. Misleading readers could harm the cause of science and have an adverse impact on patient care.[ 12 ] A recent study,[ 13 ] for example, concluded that venlafaxine use during the second trimester of pregnancy may increase the risk of neonates born small for gestational age. However, nowhere in the abstract did the authors mention that these conclusions were based on just 5 cases and 12 controls out of the total sample of 126 cases and 806 controls. There were several other serious limitations that rendered the authors’ conclusions tentative, at best; yet, nowhere in the abstract were these other limitations expressed.

As a parting note: Most journals provide clear instructions to authors on the formatting and contents of different parts of the manuscript. These instructions often include details on what the sections of an abstract should contain. Authors should tailor their abstracts to the specific requirements of the journal to which they plan to submit their manuscript. It could also be an excellent idea to model the abstract of the paper, sentence for sentence, on the abstract of an important paper on a similar subject and with similar methodology, published in the same journal for which the manuscript is slated.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

- Ask a Librarian

Abstracts - A Guide to Writing

What is an abstract.

Abstracts act as concise surrogates or representations of research projects. Abstracts precede papers in research journals and appear in programs of scholarly conferences. They should be brief, concise, and use clear language. A researcher reading an abstract should have a clear idea of what the research project is about after reading an abstract.

Abstracts allow readers to grasp the purpose and major ideas of a paper, poster, or presentation. A great abstract will be packed with information on the research project and will let other researchers know whether reading the entire paper or attending a presentation is worthwhile.

Why write an abstract?

Abstracts often serve as the advertisement of a research project. They allow readers to quickly scan a small amount of text and to make a decision as to whether the work will satisfy their information needs. If a researcher is interested, he or she will continue on to read the entire document or attend the session.

Many online databases use abstracts to index larger research projects. Using keywords from your research project in your abstract will ensure your project is easily searched.

Types of abstracts

Different academic disciplines have different research methods and requirements. For example, social sciences or hard science abstracts will typically include the parts of a research experiment; whereas abstracts in the humanities will often discuss the hypothesis being investigated and the conclusion. Conferences and journals may have specific requirements for abstract submissions, so be sure to review the requirements prior to writing an abstract for your project.

Informative abstracts

Informative abstracts are generally used for documents pertaining to experimental investigations, inquiries, or surveys. The original document is condensed reflecting its form and content and provides quantitative and qualitative information.

Informative Example

Daidzic, N. E. (2015). Efficient general computational method for estimation of standard atmosphere parameters. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace, 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2015.1053