- Write to Us

- Syndication

Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy: A Role Model, from Past to Present

Dr. Mehmood Ul Hassan Khan has specialties in management, marketing, economics and governance. He has also master degree in Development with specialization in Diplomacy and Public Relations. He has also a rich experience in research, peace and conflict resolution and defence issues. His research and comprehensive articles have already been published in China, Uzbekistan, Iran, Turkey, Azerbaijan, USA, South Korea, UAE and Kuwait too.

He has great experience in the socio-economic, geo-politics and geo-strategic issues of Central Asia, Caucasus and Middle East. He is a famous expert on CIS and Caucasus in Pakistan. Member Board of Experts: CGSS, Islamabad. Ambassador at large at IHRFW.

The “Geneva of Asia”, Republic of Kazakhstan has a pragmatic, forward looking and progressive foreign policy which emphasizes to foster strong, sustainable alliances, meaningful partnerships, and trustworthy friendships based on mutual respect. Due to its visionary leadership it has many foreign policies and diplomatic accomplishments during the last thirty years.

Kazakhstan seems a kind of positive/soft state having rich natural resources, the world’s ninth largest country by area, and located in the very geographical center of Eurasia.

It does not have favourable geopolitical conditions and moreover its own position at the junction of the interests of global players, yet it confidently maintains domestic political stability, sustainable economic growth and constructive relations with all the main actors of the global power politics.

Kazakhstan, shares one of the longest land borders with two world powers, Russia and China, manages to successfully maneuver in the dark waters of world politics.

According to Kazakhstan’s official statistics (2019-2020) China second-largest trading partner of it. In this connection, bilateral trade reached $11 billion in 2018. China is also a major investor in Kazakhstan through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Kazakhstan’s Khorgos Gateway, the biggest dry port in the world, was constructed by Chinese companies.

Kazakhstan has also maintained cordial bilateral relations with Russia since its inception. According to Kazakhstan’s official statistics (2019-2020) Russia is its largest trading partner, with an estimated $18 billion in 2018. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has very trustworthy relations with President Vladimir Putin.

In this context, security agreements provide a stable base for the Russian-Kazakh relationship as well as Kazakhstan’s membership to the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union. In January 2019, the two governments ratified a deal under which Kazakhstan will assemble Russian military helicopters. That same year, Kazakh troops participated in the Russian-led multinational exercise center 2019. But it has rejected Moscow’s offer to build a nuclear power plant in its territory which showed its independent foreign policy.

Since its independence, Kazakhstan has been a successful model of political stability, consistence democratization, social cohesion, and people’s friendly legislation and structural reforms which is based on the foreign policy strategy of H.E. Nursultan Nazarbayev, the First President of the country.

Nazarbayev, like Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, is the real de facto architect of modern Kazakhstan. H.E. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Nazarbayev’s successor and the former Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations, succeeded in the presidential elections of 2019, and continued and consolidated uniqueness of its foreign policy and followed the line of his predecessor.

Kazakhstan’s foreign policy does not envision itself as a pawn on some Eurasian chessboard, but rather as an independent power with its own objectives and ambitions. Moreover, Kazakhstan is looking to increase its image and influence, in Central Asia and beyond.

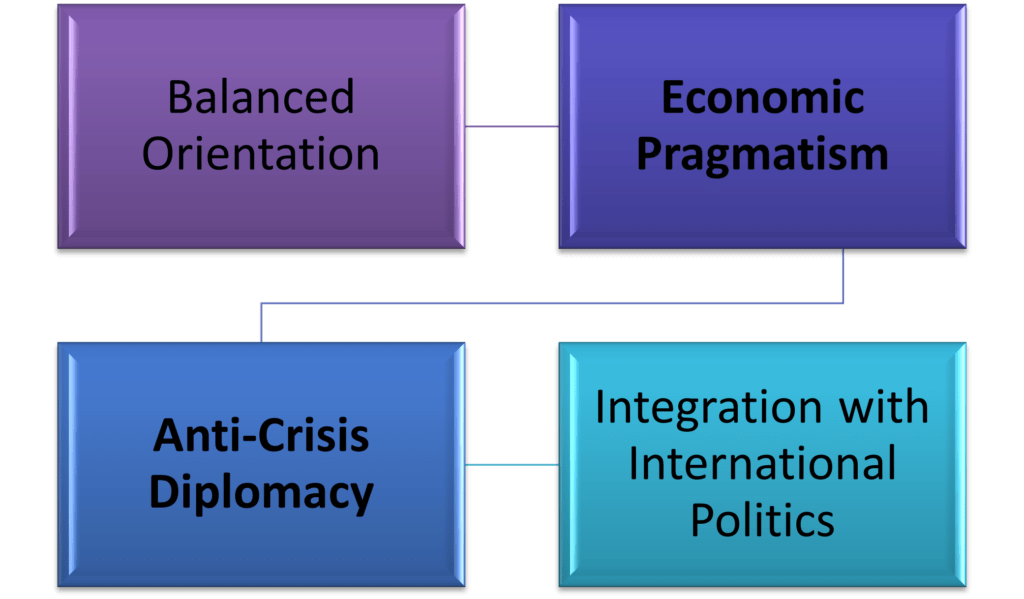

The Republic of Kazakhstan managed risks of foreign policy through the balanced development orientations of external relations in all strategic areas. It followed a “multi-vector” principle, which remained doctrinal significance for Kazakhstani diplomacy.

It distinguishes Kazakhstan from other Central Asian Countries which has an ideal combination of consistency and flexibility in the implementation of this principle and it remained strong, stable and sustainable in all its important parameters of national sovereignty, territorial integrity, politicization and democratization, socio-economic prosperity, effective good governance and last but not least, human survival and productive channels.

It has been a reasonable pragmatism and the rational decision making “not to put all eggs in one basket” which created strategic cushion to move forward in a peaceful manners. In this context, Kazakhstan has been applying the “multi-vector” model to almost all spheres of its international cooperation, engagements and dialogues since its inception.

Kazakhstan protected all its vested interest of security through innovative diplomatic maneuvering and economic manipulation since 1991 and successfully surpassed all regional as well as international crises. Formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was a deliberate strategic move to achieve element of diplomatic diversity and further sustainability among the regional main stakeholders. It has actually enhanced its regional connectivity and Out-Reach Policy (ORP) of South Asian Region.

Kazakhstan also followed Balancing Act Doctrine and has been an active participant in the NATO Partnership for Peace program, and maintains close cooperation with the United States, which, despite some kind of displeasure and discomfort in Moscow and Beijing, plays an important stabilizing role in the region from the point of view of Kazakhstan’s vested interests.

Kazakhstan has also friendly ties with USA. The U.S. former President Donald Trump and former Kazakhstan President Nazarbayev met in January 2018, a high-level meeting which was followed by another in September 2019 in New York between Presidents Trump and Tokayev. Regular official contacts with senior U.S. officials also occur through the C5+1 group comprised of the five Central Asian states and the U.S.

According to Kazakhstan’s official statistics (2019-2020) bilateral trade between Washington and Nur-Sultan reached $2.1 billion in 2018. This marked a new milestone in bilateral trade, which has generally increased in recent years; traffic of goods and services reached $1.3 billion in 2017.

Right from the beginning, Kazakhstan sought to expand the orbit of its interests, intentionally associating itself with a broader international agenda. In this connection, Kazakhstan initiated the idea of Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building measures in Asia (CICA) the only international platform providing a stable dialogue on security issues in Asia as a whole. It enabled to identify its presence in European Union (EU) through the chairmanship of the OSCE in 2010 which further enhanced its pivotal role in the European security architecture especially energy security.

Kazakhstan and the European Union (EU) have signed a new trade agreement, the Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA), which entered into force on March 1, 2020. According to the European Commission (2020) the EU is Kazakhstan’s biggest trade partner as a bloc, with almost 40 percent share in its total external trade. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has invested in Kazakhstan’s energy industry by building solar power facilities.

Kazakhstan consistently adopted and implemented the principle of economic pragmatism, which remained the main criteria for all strategic decisions for the last thirty years. Economy first, then politics”, remained dominating factor during former president Nazarbayev and is still the role model of incumbent government. This approach was development oriented which promoted economic stability and ultimately achieved its sustainability.

It blocked political radicalism within the country, but also in the external arena, in relations with strategic partners. Nevertheless gradual political reforms have been initiated which also created befitting business equity and political tranquility in the country.

Kazakhstan’s engagement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), invariably emphasizes the purely economic nature of this organization. Thus Nazarbayev’s principled position in favor of economic pragmatism blocked all attempts to politicize the union.

Kazakhstan’s inclusion in the Turkic Council is another prime example of its economic and commercial diplomacy which has actually further diversified its regional as well as international relations.

Kazakhstan has been performing status of facilitator and mediator for the last thirty years. It hosted a round of the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program back in 2013, and has hosted over a dozen rounds of talks intended to find a solution for the conflict in Syria under the flagship of the “Astana Peace Process (APP)”.

Moreover, its successful diplomatic efforts to reconcile Putin with Erdogan in 2016 became possible in particular because of special relations with Turkey which successfully averted an imminent diplomatic tussle and maintained peace in the region and beyond. Nazarbayev’s personal trusting relationship with both leaders played a special role which defused widening political and diplomatic rift between two countries. In this regard, Kazakhstan’s spirit of classical old diplomacy played a decisive role.

Interestingly, Kazakhstan followed anti-crisis diplomacy due to which Kazakhstan was able to avoid the risk of being drawn into contradictions between world powers.

In this connection, the Russian-Georgian conflict of August 2008 somehow created a difficult situation for the multi-vector policy of the country. Refusing to openly accuse the Kremlin at the start of the conflict, Nazarbayev, at the same time, was able to withstand the pressure from Moscow to recognize South Ossetia’s independence was a “master stroke” of its foreign policy. Afterward, Kazakhstan actively supported the resolution calling “for preserving the territorial integrity of states.” at the SCO summit.

Kazakhstan’s peaceful persuasion of diversification energy policy in terms of supplies and production should be treated as a significant “balancing” step to begin exporting oil to the West through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline which was aimed at partially reducing the dependence on the transport and communication systems of Russia.

Right from the beginning, Kazakhstani has been staunch supporter of conflict resolution and always seeks to independently create favorable external conditions.

Kazakhstan striving hard spirits developed spirits of rational decision making which secured its strategic interest and developed economic self-reliance and financial stability during the intensification in relations between the West and Russia, as well as deepening contradictions between the US and China, and resultantly it has created the Astana International Financial Center (AIFC). The establishment of AIFC has actually further enhanced inflows of FDIs, FPIs and joint ventures in the country and moreover, enabled it to enter in the Russian and Chinese financial markets.

Formation of the AIFC vividly reflects Kazakhstan’s ability to skillfully integrate itself into the dynamics of relations between different poles of power, effectively capitalizing its competitive advantages as a transit zone.

Kazakhstan has been following systematic efforts to integrate its foreign policy initiatives into the very center of international politics. Furthermore, this policy pursues a number of specific tasks, such as preventing a marginalization of Kazakhstan, as well as the inclusion of Central Asian region in the international arena.

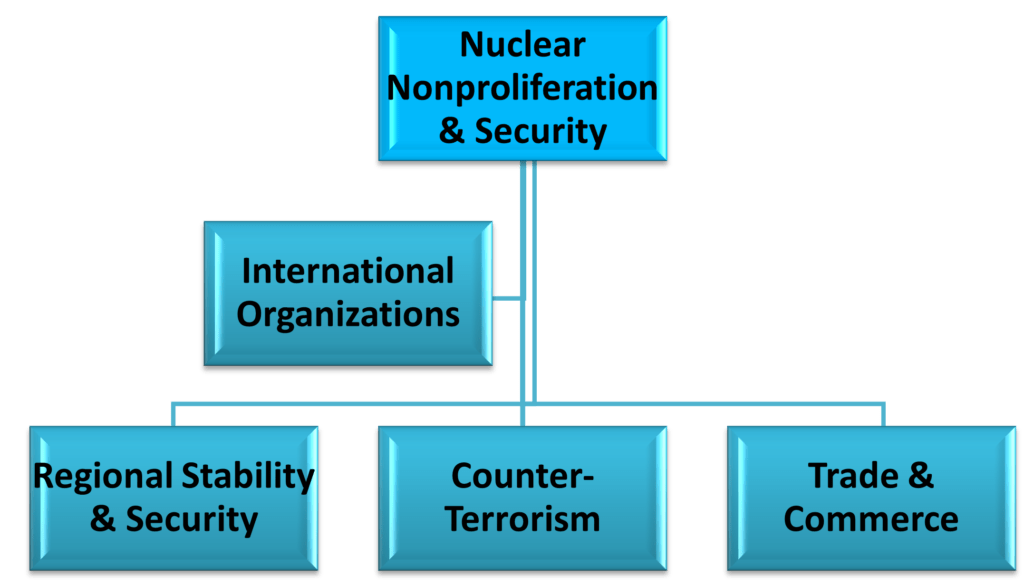

Since its inception, Kazakhstan unilaterally rejected nuclear weapons arsenal. It is pertinent to mention that Kazakhstan possessed the 4th largest nuclear capability in the world, which was more than what China, the UK, and France had combined.

In this connection, its zero nuclear arsenal policy won the hearts and souls of all the regional as well as international power brokers. Voluntary rejection of Weapon of Mass Destruction (WMD) was the innovative move which has certain socio-economic, geopolitical and geostrategic dividends. It fostered its credibility in the West and among the international community in general.

Its rational thinking to abandon of nuclear potential has also secured numerous tangible dividends. Since 1991, Kazakhstan has attracted more than $300 billion of foreign direct investment, accounting for 75 percent of all investments in Central Asia as a whole.

Its visionary leadership created “Greater Eurasia” which was based on the unification of the Eurasian Economic Union, the Silk Road Economic Belt, and the European Union into a single mega-project. It was announced at the 70th session of the UN General Assembly in 2015.

The idea of Greater Eurasia (GE) triggered its regional connectivity and further consolidated its economic potential. It opened a new window of opportunity for all the regional players to form befitting propositions in terms of economy, trade and commerce, investments, and commercial diplomacy. Finally it promoted the principle of “inseparable of security”.

Kazakhstan has been following proactive politics is now the best way to stay afloat, which makes it possible not to become a passive hostage of a steadily escalating rivalry between major powers. It tried to promote spirits of harmony, peace and stability.

Its Astana club created a new format for meetings of political and business elites. It is a unique forum where the most influential representatives of the USA, Russia, China, Iran, Turkey, and 30 other, mainly Eurasian, countries gather at the same table to resolve issues.

According to its Foreign Ministry (2019) Kazakhstan has established relations with Barbados and with all Latin American and Caribbean nations which vividly reflected its diversified, dynamic and constructive foreign policy.

It hopes that in the near future, the “Asian Vienna (Kazakhstan) might be of considerable interest, because of its ability to resolve contradictions along the USA-Russia, USA-China, USA-Iran lines. The visionary leadership of Kazakhstan and its rich and diversified diplomatic and mediating experience may turn out to be very valuable assets.

Kazakhstan is a member of many influential international organizations. It is active member of the United Nations (UN), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and last but not least, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

Since 2003, it has been arranging the Congresses of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions in its country, aiming to unit at one table the leaders of all leading world religious confessions.

Kazakhstan also chaired the Group of Landlocked Developing Countries, a 32 member state initiative under the umbrella of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Furthermore, Kazakhstan remains the only Central Asian nation to have held a non-permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), for 2017-2018.

Kazakhstan took its participation in the UN to a new level when it deployed for the first time a company of 120 peacekeepers to the UN mission in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in October 2018 and a new contingent was sent in November 2019. No other Central Asian country has sent this amount of military personnel to UN peace missions.

Now President Tokayev has carried on the multi-vectored doctrine that First President Nursultan Nazarbayev implemented during his presidency. Both leaders believe that by enacting strong political and economic reforms, the country will be in a better position to build its relationships with other nations.

Kazakhstan is a neutral nation, which has worked hard to reform its military, political and economic policies as it advances toward a full democracy. The new concept of Kazakhstan’s foreign policy openly declares its intentions to secure the status of a “leading state” in the region.

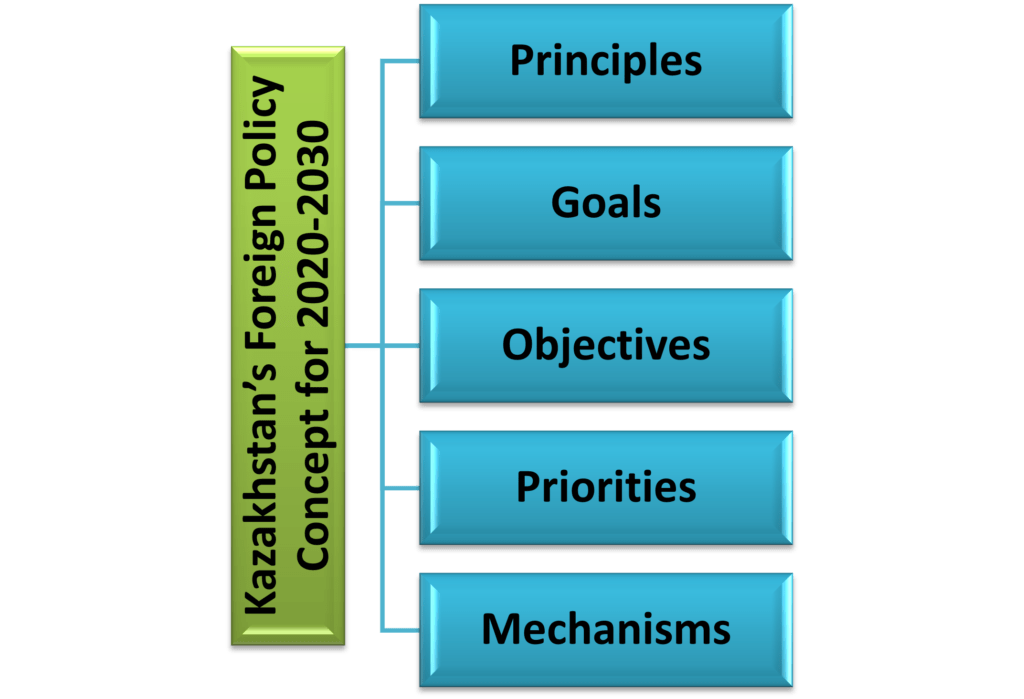

On March 6, 2020, a presidential decree has approved the Republic of Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy Concept for 2020-2030.

It highlights salient features of its system of fundamental views, i.e. the principles, goals, objectives, priorities, and mechanisms of the country’s foreign policy during the reference period.

In this context, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Zhomart Tokayev from the very beginning clearly emphasized the need to continue exercising the country’s endorsed political course, the foundations of which were laid by country’s first president Nursultan Nazarbayev.

It seems that the adoption of a new Foreign Policy Concept aimed at pursuing a multi-vector and well-balanced foreign policy . It is blue print for the new era. It is road map of further strengthening of bilateral relations and achieving of objectives of commercial diplomacy. It facilitates the associated main stakeholders to jointly work for the further development of the positive developments of Kazakhstan.

The new concept of foreign policy has some certain additions, variations and supplements which jointly shape its future recourse, formation of national narrative, development plans and above all specific priorities in diverse filed of economy, trade & commerce, investments, structural reforms, politicization and democratization, new social norms and devising of new comprehensive grand strategy to combat with all emerging state and non-state threats and crises.

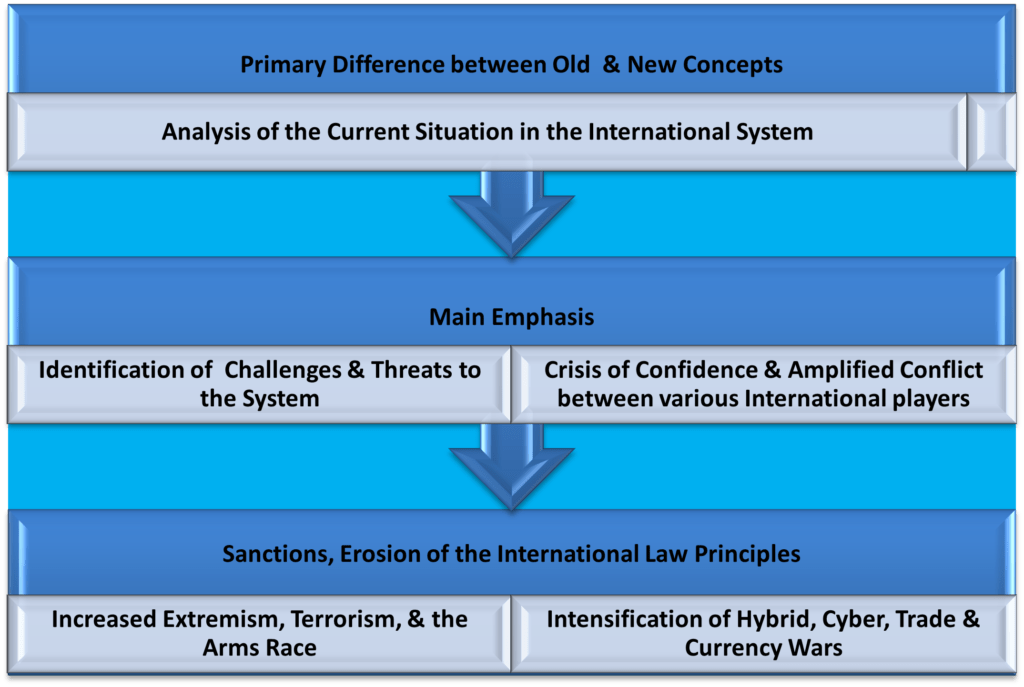

It pinpoint strategic therapy to merging threats like climate change, conflict between various international actors, including sanctions, erosion of the international law principles, increased extremism, terrorism, and the arms race, the intensification of hybrid, cyber, trade and currency wars, among others.

It affirms Kazakhstan imperative and advantageous position of an active and responsible international community participant and contributor to ensuring international and regional stability and security. It emphasizes to maintain friendly, predictable and mutually beneficial relations with foreign partners.

It seems that Kazakhstan is interested to remain distant and neutral in contradictions and conflicts of world power brokers. Therefore, a multi-vector and pragmatic foreign policy permits Kazakhstan to build relations with other countries and international organizations as per its vested interests and on an equal and constructive basis.

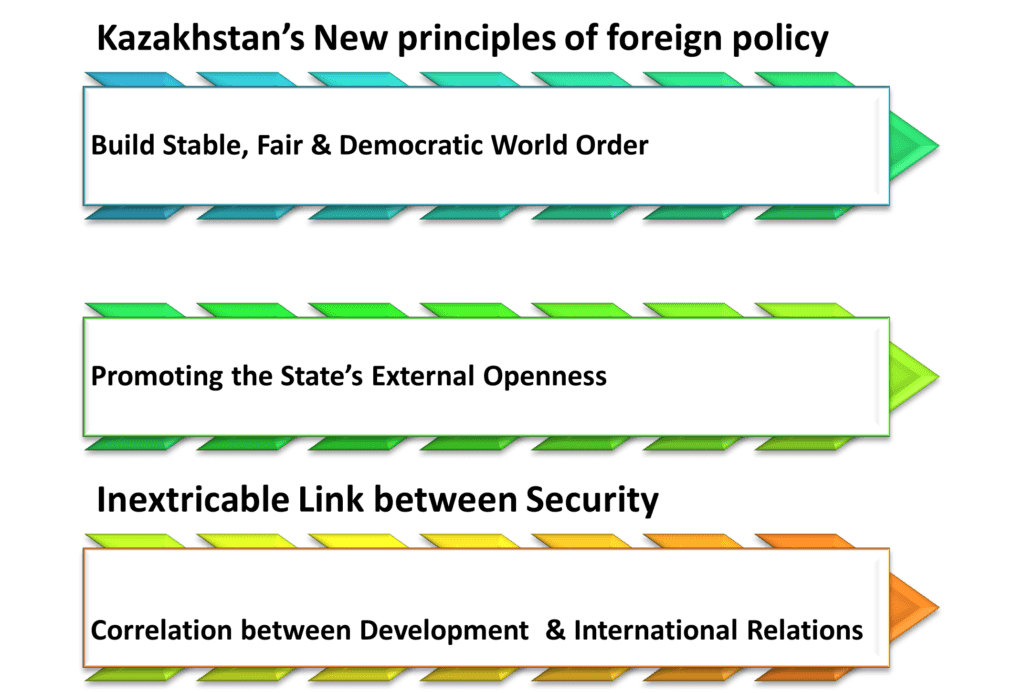

It chalks out new principles including helping build stable, fair and democratic world order, promoting the state’s external openness and the inextricable link between security and development in international relations. It urges an equitable integrative world to take care of global political, economic and humanitarian issues.

The new concept highlights the strategic importance of multiculturalism and aiming at establishing a collective vision and effective approaches for the international community to address a wide range of global and regional issues based on multilateral advisory and agreements.

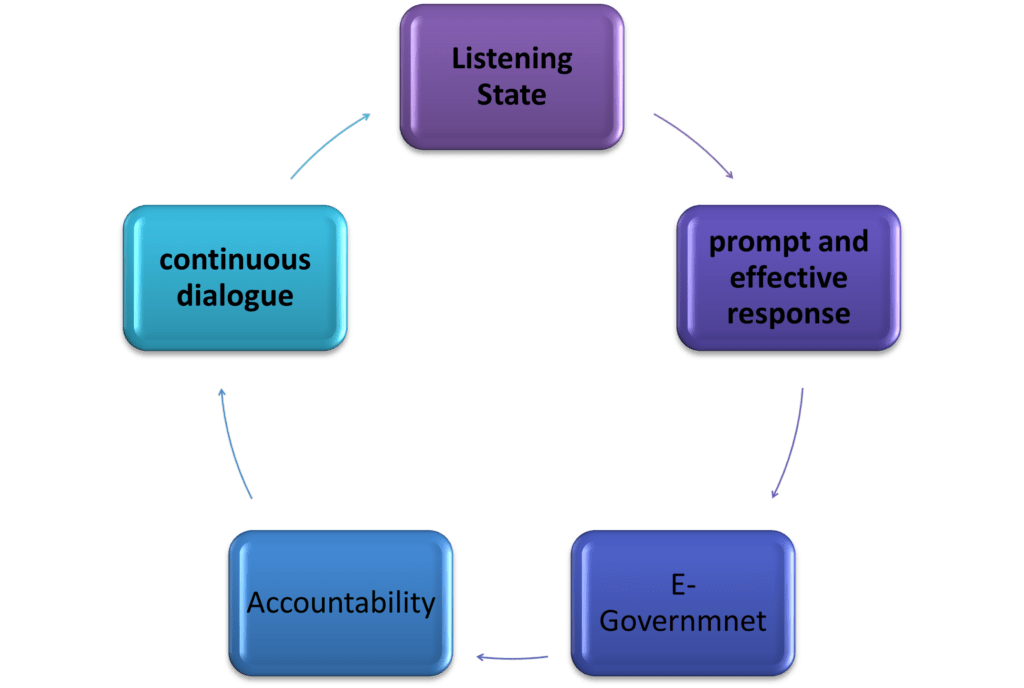

It further consolidates the concept of the “Listening State” proposed by President Kassym-Zhomart Tokayev in his first Message to the people of Kazakhstan. It refers to creating a qualitatively new mechanism for ensuring a continuous dialogue between state and society, whereas the former gives a prompt and effective response to the needs of citizens.

It has certain economic dimensions which are development oriented and dynamic in its composition. It has further increase its constituent priorities, compared to the previous concept, from 9 to 14.

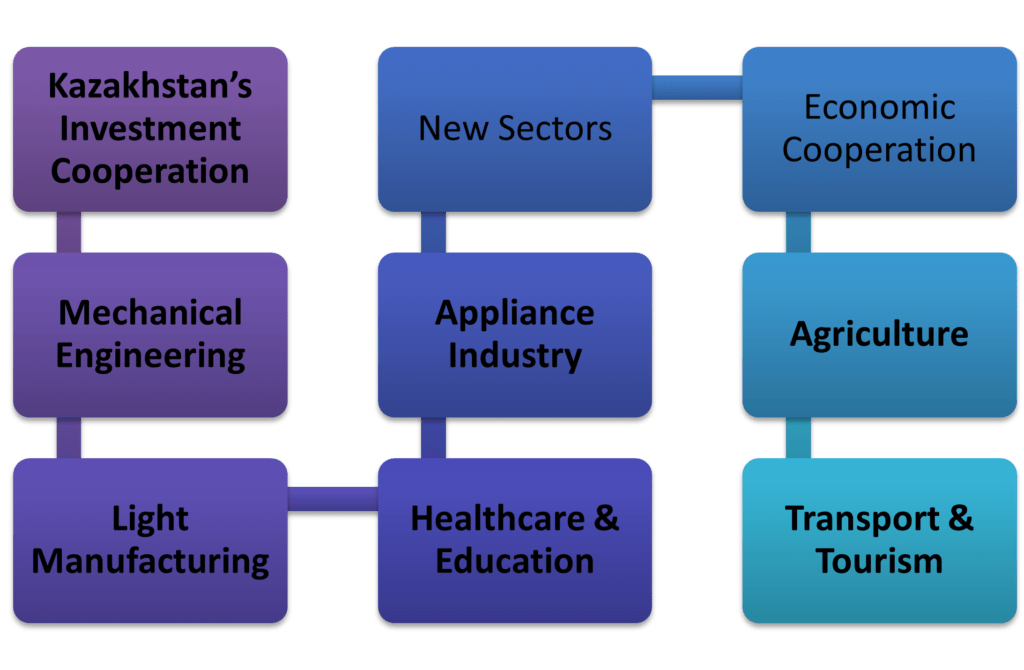

Previously Kazakhstan extended its investment cooperation with foreign partners through listing the economy sectors requiring foreign investment. These are mechanical engineering, appliance industry, agriculture, light manufacturing, healthcare, education, transport, tourism, etc. Thus, the activities of Kazakhstani diplomats are focused on promoting the non-raw-materials sectors of the country’s economy.

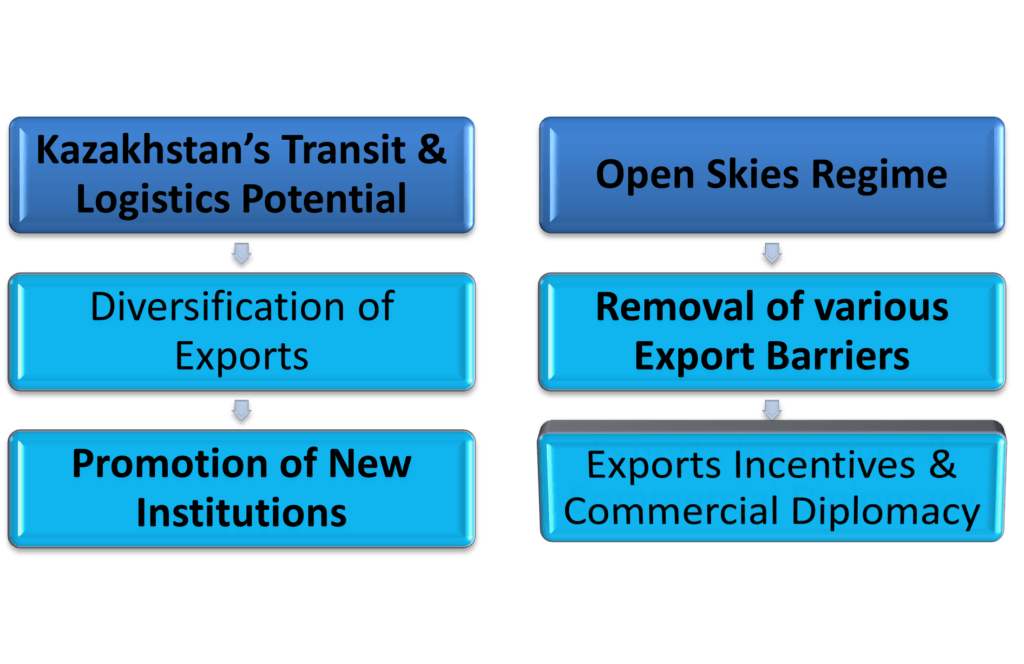

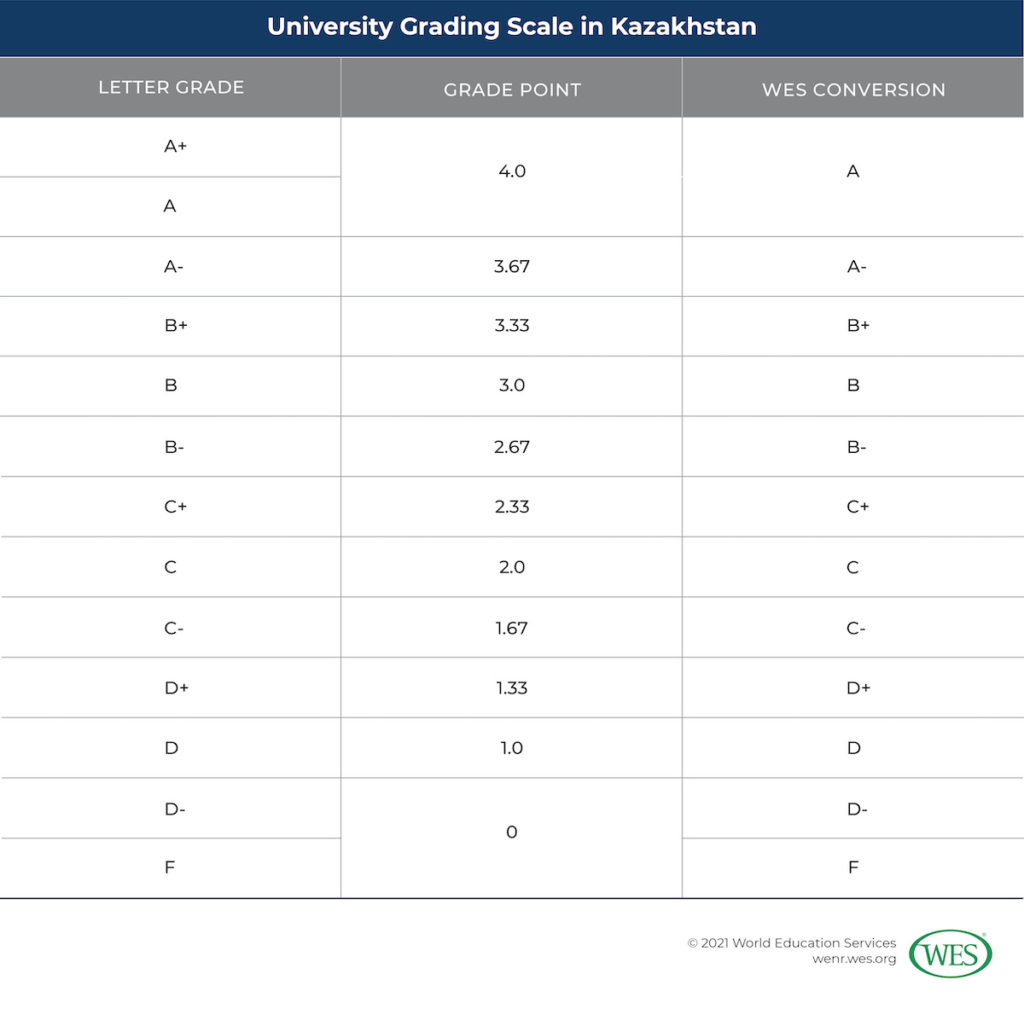

Figure-VIII

It is designed to promote the development of Kazakhstan’s transit and logistics potential, including the introduction of an “open skies” regime, the expansion of the range, volume and geographical destinations of national exports, dismantling various export barriers in foreign markets, as well as the promotion of institutions like the Astana International Financial Center, The Khorgos International Center for Cross-Border Cooperation and created jointly with Uzbekistan the “Central Asia” Center for Trade and Economic Cooperation.

It indicates a major change in Kazakhstan’s foreign policy priorities. Its perspective applies particularly to the country’s positioning in a regional context. In the previous concept, Kazakhstan presented itself as a country that recognizes its role and responsibility and strives for the development of intra-regional integration in Central Asia, now it openly declares its intentions to consolidate its status as a “leading state in the region which is indeed a paradigm shift in its outlook.

According to new concept relations with other countries in the region have a strategic nature and relations with China, Russia, the United States and the European Union. It supports the expansion of multilateral dialogue and cooperation in Central Asia. Now it appears that Kazakhstan stands ready to help strengthen the existing interaction formats between the Central Asian countries and foreign partners.

Interestingly, Kazakhstan’s foreign policy priorities are now shifted from individual countries to regional and multilateral cooperation. In Asia, for instance, the emphasis is placed both on active participation in the work of the SCO, the Council of Interior Ministers, the OIC, the Cooperation Council of Turkic-speaking states, and on expanding ties with ASEAN, the League of the Arab States and other international organizations, where Kazakhstan is involved.

It fosters enhanced cooperation in the Caspian region in the field of energy, transport, environmental protection and security following adopted in the 2018 Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea. It also expresses an intention to continue close cooperation with the EAEU member state and to optimize negotiation approaches within the framework of the Union. It supports further strengthening of bilateral relations with Great Britain, which completed its exit from the European Union (Brexit) last year.

Being prominent regional expert of Kazakhstan & CIS I support salient features of new concept of foreign policy. It combines policy formulation with actuality of its implementation thus jump from cosmetic orientations to systematic approach to achieve the goals of further socio-economic prosperity, economic sustainability, continuation of structural reforms, further initiation of political, democratic, social, civil, administrative and judicial reforms under the gambit of pragmatic and progressive foreign policy.

Over the past 30 years Kazakhstan has established diplomatic relations with 186 countries and transformed into one of the dynamically economies of the region and world alike. It successfully nurtured its macro-economy with immaculate vision, policies, programs and integrative mechanism of balanced foreign policy since its inception.

Successive leadership of Kazakhstan followed a holistic foreign policy to make bridges of political consultation, social concession, geopolitical and geostrategic alignment which enabled it to sail through the regional triangle of China, Russia and Turkey to global super orbits of the USA and the EU to protect its vested interest.

Its inbuilt quality of crisis management under the umbrella of foreign policy has averted numerous crises of basic identity, sovereignty, territorial disintegration, economic meltdown, financial crunch, political instability and above all crises of alliance and conveniences. Its participation in the SCO, OIC, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and Turkic Council has further diversified its foreign policy.

Its superior, supportive and stimulating skills of “Conflict Resolution” have been role model for all the regional as well as international power brokers due to which it lessened escalations and promoted normalizations between the conflicting parties, prime examples may be nuclear negotiations about Iran, Syrian crisis and many others important political and diplomatic rifts in the near past between Turkey and Russia, Iran and the West and last but not least, disorder between Central Asian Countries.

Interestingly its multi-vector foreign policy stimulates people’s friendly policies. Its listening state policy is the outcome of its historic civilization, traditions and norms further enhances and institutionalizes spirits of e-government, accountability, good governance, social responsibility and last but not least political activation in the country.

Its new concept of foreign policy for 2020-2030 has now introduced new ways and means to foster socio-economic prosperity, political stability, democratic norms and social cohesion in the country. It has outlined new codes of glory and gratification. It has new priorities of economic growth, regional connectivity, global engagement and of course persuasion of leading role of Kazakhstan.

Its new concept of foreign policy for 2020-2030 showcases its investment potential and prospects of joint ventures through befitting regional as well as international partnerships.

To conclude the Republic of Kazakhstan has been pursuing its foreign policy on the basis, continuity of the former president policies, striving for building a stable, fair and democratic world order; equal integration into the global political, economic and humanitarian space; effective protection of the rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of Kazakh citizens and compatriots living abroad.

Moreover, Kazakhstan has been trying to promote the external openness of the state, the creation of favourable external conditions for increasing the welfare of Kazakh citizens, the development of the political, economic and spiritual potential of the country.

Kazakhstan’s multi-vector, pragmatic, progressive and proactive foreign policy stands for the development of friendly, equal and mutually beneficial relations with all countries, interstate associations and international organisations of practical interest to Kazakhstan.

Its foreign policy sustains multilateralism to create a collective vision and effective approaches of the international community to solving a wide range of global and regional problems on the basis of multilateral consultations and agreements.

Its foreign policy is the ideal combination of development and security which cares both at the national, regional and global levels. It involves the development of integrated approaches of the international community to respond to cross-border security challenges and threats, conflict resolution, peace building in post-conflict countries.

Kazakhstan’s foreign policy strategy has strategic goals which include strengthening the independence, state sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country, maintaining the independence of its foreign policy. It cultivates consolidation of leading positions and promotion of long-term interests of Kazakhstan in the Central Asian region. It asserts its active and responsible role in the international community, making a significant contribution to ensuring international and regional stability and security.

It secures its friendly, predictable and mutually beneficial relations with foreign states in both bilateral and multilateral formats, the development of integrated cooperation with interstate associations and international organisations.

It supports its foreign policy potential in order to increase the competitiveness of the national economy, the level and quality of life of Kazakh citizens.

It assists in preserving and strengthening the unity of the multiethnic people of Kazakhstan through foreign policy methods and raising the practical interests of citizens of Kazakhstan and national business to the forefront of the state’s foreign policy.

Its new concept of foreign policy 2020-2030 guides the parameters to achieve its strategic goals through increasing efforts to form a politically stable, economically sustainable and secure space around Kazakhstan, continuation of the course on strengthening international peace and cooperation, increasing the effectiveness of global and regional security and interaction systems; the development and implementation of new approaches to key foreign policy issues at the bilateral and multilateral levels, taking into account the promotion and protection of the long-term strategic interests of the state; ensuring a new level of “economisation” of the foreign policy, further strengthening the position of Kazakhstan in the system of the global economic relations; realisation of “humanitarian diplomacy”, popularisation of a positive image of the country in the world community; establishing an effective system of communication with the public of Kazakhstan on foreign policy issues; improvement of work to ensure the protection of personal and family rights of citizens, the legitimate interests of individuals and legal entities of the Republic of Kazakhstan abroad.

The New Uzbekistan is Becoming a Country of Democratic Transformations, Big Opportunities and Practical Deeds

Taliban to be judged by ‘actions not words,’ says uk premier, related posts, cabinet chairman endorses conclusion to agreement on deepening and enhancing..., kazakhstan showcases digital family card as key innovation at asia-pacific..., kazakh capital to host astana think tank forum in october,....

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Official website of the

President of the Republic of Kazakhstan

- State of the nation address

The Head of State sent a congratulatory message to the President of Indonesia

August 17, 2024

June 9, 2021

On further measures of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the field of human rights

The President of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Future Prospects Of Kazakhstan: An On-the-Ground Report From Astana

July 12, 2023 Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 , Central Asia

Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 32 Issue 6 Authors: Silvia Boltuc

Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union, for most Europeans, Kazakhstan remains an unknown and unexplored land. It has a complex identity halfway between Asia and Europe. A past in the steppes, but with cities such as Astana projected towards the future.

Kazakhstan’s Soviet past is well known; ironically, the country remained the last piece of the Soviet Union for four days when even the area today known as the Russian Federation had left it on December 12 th , 1991.

Today, the winds of change are pushing towards a new direction that aims to challenge traditional elements of the past, such as the oligarchic system . 25% of Kazakhstan’s population is from a new generation, not inheriting the Soviet legacy, but making its own demands .

The government addressed these requests through a referendum in June 2022 and the parliamentary elections in March 2023. This event boosted the modernisation and democratisation process, creating the “just and fair Kazakhstan” sponsored by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.

The atmosphere in Astana was one of strong expectation regarding a long-awaited change. The referendum led to a constitutional reform which created a new model of Majilis (lower house of Parliament) and maslikhats (local legislative body) to guarantee voters’ national and regional interests and a variety of perspectives in representative power bodies.

The reforms, according to the Government, curbed the President’s authority, bolstered Parliament and human rights, and encouraged citizen involvement in politics.

Decolonisation and Adaption for the Future: Language Politics in Kazakhstan

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Driving down any street in Astana, Kazakhstan’s new, hyper-futuristic capital city, you may be surprised to note the total absence of any Russian-language signage. In fact, insofar as whoever is in charge of Kazakh road marking is concerned, English takes precedence over Russian, with Latin script transliterations of placenames sitting under the Kazakh Cyrillic. This comes in spite of the fact that, statistically, Russian is a ‘majority’ language of the country, with 95% of the population having proficiency as of 2009. On the contrary, Kazakh is spoken by approximately 83.1% of the nation , a lesser, but significant, majority. Having arrived in Astana just over a month ago, I was struck by the bifurcated nature of many of the conversations I was overhearing, with taxi drivers, shop workers, and people on the street shifting seamlessly between Kazakh and Russian. In the process of writing this piece, I interviewed around ten Kazakh speakers, across a wide range of age groups, to gain insight into their lived experience of the language.

The generational gulf in attitudes toward the Kazakh language in Kazakhstan was striking: older people tended to be more engaged with the significance of the language and its implications for the Kazakh identity, whereas younger people, born after the fall of the USSR, were more ambivalent – taking the prevalence of Kazakh as an accepted, intrinsic part of the only linguistic culture they have known. Furthermore, every Kazakh speaker interviewed unanimously positioned themselves against Russia, and spoke in almost exclusively negative terms concerning “Russianness”, the Russo-Ukrainian war, and perceived Russian colonial legacies in Kazakhstan. Whilst this small sample cannot accurately reflect the popular opinion of the whole Kazakh population, these interviews nevertheless suggest a “decolonial” trend in Kazakh society since the outbreak of war in Ukraine

Historical Context:

Prior to the Russian conquest of Central Asia between 1835 and 1895, the Kazakh language was by and large oral, emerging from the Kipchak branch of Turkic languages, with the first Kazakh texts being written in Arabic script. Both Tsardom and the Soviet Union in turn systematically eroded the Kazakh language, with Stalinist collectivisation resulting in the starvation of approximately one third of the ethnic Kazakh population , alongside a campaign of Russification. Russian, in the Kazakh SSR, became a prestige language – the language of government, and a means of achieving social mobility and a steady career. In 1970, 42% of Kazakhs were fluent in Russian, already a dramatic increase on Russian’s total insignificance through the 1920s and 30s. But by the time of independence, 63% of ethnic Kazakhs spoke Russian , with 30% of this figure having Russian as their sole language. It is pertinent to note that Kazakh-Russian bilingualism was almost entirely unreciprocated on the part of Kazakhstan’s ethnically Russian population throughout the Soviet era.

With this in mind, it is unsurprising to observe some of the Kazakh government’s post-independence policy concerning language. In September 1989, two years prior to independence, Kazakh gained state language status. In the years following, various pieces of legislation have made inroads toward increasing its uptake. For example, as recently as October, a bill has been drafted to increase Kazakh language output in state media from 50% to 70%.

The Kazakh Language as Decolonisation:

As such, the use of the Kazakh language has a fundamentally decolonial function. The war in Ukraine and the Kazakh state’s subsequent commitment to sanctions against the Russian Federation has renewed the importance of these language policies. The current drafted plans to entirely do away with Cyrillic script for Kazakh by 2025 is a definitive slight against the Russians, a rally against an alphabet imposed upon them by an imperial power for little more than political convenience. The primacy of Russian arguably serves as a legacy of Russian and Soviet imperialism and therefore enables the Russian state to exercise soft power over its former territories. Speakers of Kazakh, particularly the older generation, are keen to emphasise this, with one interviewee declaring that “the Russians humiliate us through language”, accenting a culture of embarrassment about the notion that the Kazakh state has essentially sleepwalked into a situation whereby their native language has been replaced by a colonial one in the space of one hundred years. The same interviewee, who grew up in Shymkent and spoke Kazakh at home, discussed the importance of ensuring her children’s competence in the language – “it connects us with our heritage, which, in our culture, is incredibly significant”.

Speaking with younger Kazakhs, it was somewhat predictable to observe their ambivalence on the issue. Many of whom take the speaking of Kazakh as a given, having only known an independent Kazakh Republic; one interviewee, Munira, declared “I don’t think about it at all”.

What was particularly notable across nearly all of the people interviewed for the purposes of this article, was a keenness to practice and speak English. Nursultan Nazarbayev, the founding father of the independent Kazakh Republic, declared Kazakhstan a ‘trilingual nation’, with the English language comprising the third point of the triangle. English, in the Kazakh consciousness, particularly among the younger generation is, for want of a better word, cool. American television, western pop music, and imported designer clothes are very much in vogue. While many interviewees struggled to articulate the reasons for this, one statement to the effect that, “English is a road to better careers for us, and with that comes English lifestyles” provides an astute explanation. From a linguistic standpoint, it was fascinating to observe in my own conversations the ease with which Kazakh youths switched codes from Russian to Kazakh to English.

Kazakhstan is a relatively young nation and one whose consolidation of identity is fundamentally intertwined with its language. While Russian, in the words of Nursultan Nazarbayev, “ enabled Kazakhs to access the great literature ”, it simultaneously eroded indigenous Kazakh. Ironically, the Putin regime has been the biggest, albeit inadvertent, catalyst for the use of Kazakh, with the Russo-Ukrainian war triggering a resurgent interest, and pushing the need for derussification to the fore. Nevertheless, a political cognitive dissonance between Kazakh state language policy and economic policy pertaining to the Russian Federation persists: as recently as the start of October 2023 the Kazakh government signed a strategic cooperation deal with Gazprom . Ultimately, the continued growth of the Kazakh language and its consolidation among the younger generation must be fostered and encouraged, for the sake of a future beyond imperial hangovers.

- Accreditation and Quality

- Mobility Trends

- Enrollment & Recruiting

- Skilled Immigration

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East

- Country Resources

- iGPA Calculator

- Degree Equivalency

- Research Reports

Sample Documents

- Scholarship Finder

- World Education Services

Education System Profiles

Education in kazakhstan.

Sidiqa AllahMorad, Knowledge Analysis Manager, WES, Chris Mackie, Editor, WENR

Kazakhstan is a country in transition. Since 1991, when it became the last of the former Soviet republics to declare independence, its leaders have sought to transform the country’s economy, release it from the grip of central planners, and open it to market forces. Kazakhstan’s leaders have also sought to similar transformations elsewhere, at least nominally. Government officials have proclaimed a desire to decentralize political power, to reverse decades of international isolation, and to unify an independent, autonomous nation that for more than half a century had been tightly integrated into the Soviet Union.

But, as the length of that still-incomplete transition suggests, their success has been mixed. At times, continuity has held the upper hand over change, and lasting imprints of the country’s Soviet past still mark the land and its people. Despite ambitious restoration efforts , the Aral Sea , once the world’s fourth-largest lake, has shrunk to a 10 th of its previous size after decades of Soviet riverine diversions for irrigation and hydropower projects. Russian, the language of politics, commerce, and education in the Soviet Union, also remains the most widely spoken language in Kazakhstan, although reform efforts aimed at promoting the Kazakh language have achieved considerable success.

This transition has not spared Kazakhstan’s education system. Since independence, the government has embraced educational reforms aimed at opening education provision to the free market, decentralizing administrative oversight and accountability, integrating the education system more closely with the international community, and leveraging education to unify the nation. In recent years, given the country’s economic and political ambitions, the rush to transform the education system has only intensified.

But, as in other sectors, progress has been far from steady. In a syncopated series of advances and retreats, government officials have announced ambitious reforms, only to quickly walk them back. The basis for these reforms, as well as that of so much else in contemporary Kazakhstan, can ultimately be found in the turmoil of the country’s immediate post-independence social, political, and economic experience.

Post-Independence: A Decade of Change and Continuity

The dissolution of the Soviet Union sent shockwaves through every corner of Kazakhstani society, triggering outbreaks of long-forgotten diseases , fears of violent political unrest, and a mass exodus of ethnic minorities. The country’s economy was hit particularly hard. A constituent republic of the Soviet Union since 1920, the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh SSR), as it was known from 1936 to 1991, was of all the former Soviet republics one of the most closely tied to the metropole . Its economy had long depended on the seamless transportation of natural resources pulled from its rich soils and taken to other Soviet republics for processing.

As these now post-Soviet states introduced new tariffs and customs, disrupting the country’s long-established supply chains, Kazakhstan’s economy crashed. Between 1990 and 1995 the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 31 percent . 1 Hyperinflation ran rampant, reaching nearly 3,000 percent in 1992, as the government lifted price controls and expanded the money supply to cover large budget deficits. Growth remained sluggish until 1999, hindered as it was by low oil prices and a severe economic decline in Russia, still Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner , culminating in the 1998 Russian financial crisis.

The dissolution also caused immense social dislocation. Over 1.7 million ethnic Russians and more than half a million, or nearly two-thirds, of ethnic Germans left the country between 1989 and 1999. At the same time, the birthrate of those remaining plummeted, causing the size of the population to contract by more than 9 percent between 1991 and 2001, when it reached 14.9 million. These losses compounded the country’s economic troubles. The loss of large numbers of Russians and Germans, a disproportionate number of whom had previously held skilled positions in the Kazakh SSR’s government and largest industries, left a gaping hole in the country’s labor supply.

These early social and economic troubles were influential in shaping the earliest phase of the nation’s independence. Combined with a loss of subsidies from Moscow and disruptions to tax collection mechanisms, the faltering economy sharply reduced government revenue, leading to a rapid deterioration in the quality of public services. The collapse also forced the government to consider drastic economic reforms, which it laid out explicitly in the Kazakhstan 2030 Strategy . Adopted in 1997, this strategy prioritized reducing government interference in domestic and foreign trade, improving tax and tariff administration, revising corporate governance structures, encouraging foreign investment and international ties, and privatizing state-owned enterprises.

The push to privatize public enterprises had a particularly consequential impact on the future of the country and its education system. In the 1990s, it prompted a fire sale of state assets. Foreign investors, hoping to capitalize on bargain prices for a stake in Kazakhstan’s rich oil fields, descended on the country. By 1999, nearly half of all medium-size and two-thirds of all large state enterprises had been sold off, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD’s) 1999 Transition Report .

Although nowhere near as thorough as it was in other sectors of the economy, this privatization drive extended to education as well. The 1990s witnessed a rapid expansion of private academic institutions, many of which, as time proved, were of very poor quality. Although most public schools and universities remained under tight government control, legislation issued shortly after independence introduced tuition fees at public universities.

While international financial institutions praised Kazakhstan’s leaders for their enthusiastic embrace of privatization, other observers were more skeptical. In 1999, Transparency International ranked Kazakhstan in the bottom quintile of its Corruption Perceptions Index . In the years that followed, news reports exposed the dark underbelly of Kazakhstan’s free market reforms, revealing a world of backroom deals and widespread kickbacks extending to the highest levels of government. In 2003, two businessmen from the United States , one a former Mobil Oil Corporation executive, were charged in connection with $78 million in bribes to secure oil contracts. The bribes were paid to two high-level Kazakhstani officials : the former prime minister, Nurlan Balgimbaev, and Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

While Kazakhstan’s post-independence economic transformation was rapid and disruptive, its political system was characterized by far more continuity. Nazarbayev, who had for years served as the prime minister of the Kazakh SSR and chairman of its Communist Party, transitioned smoothly into the newly independent country’s top post as president. Although ostensibly running the country as a democracy, once in power Nazarbayev quickly cracked down on any political opposition, winning multiple elections with more than 95 percent of the vote. Surprisingly, international election monitors have criticized every election since independence as unfree and coerced. Nazarbayev also quickly moved to centralize power in the Office of the President, keeping a tight grip on all levels of government. It remains to be seen what impact Nazarbayev’s resignation in 2019 will have on democratic processes. Despite resigning, Nazarbayev remains the chairman of the country’s most powerful military institution and the leader of its dominant political party.

These events had a formative influence on the course of Kazakhstan’s later history, and on its education system in particular. Although conditions in the new millennium changed dramatically, the turmoil of these early years continue to shape the country to this day.

The New Millennium: Kazakhstan’s Uncertain Future

Kazakhstan’s experience in the twenty-first century differs markedly from that of the last decade of the twentieth. In 1999, Kazakhstan’s economy entered a new phase of rapid expansion, spurred by the devaluation of the tenge , Kazakhstan’s currency, and the start of a nearly decadelong period in which the global price of crude oil increased more than 10-fold. In 2006, after more than half a decade during which annual GDP growth rates hovered at around 10 percent, Kazakhstan’s economy—which had only recently seemed on the verge of collapse—earned it a spot among the world’s upper-middle income countries . With some notable exceptions, growth has remained solid since.

These improvements have padded government coffers and sparked ambitious development plans. In late 2012, President Nazarbayev unveiled the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy , an ambitious state plan aimed at making Kazakhstan one of the world’s 30 most developed countries by the middle of this century.

The booming oil economy also drove up demand for professionals with the education and skills to work in the new enterprises. Even today, despite rapid growth in education participation rates, companies still report widespread skills shortages. In 2017, Kazakhstani executives listed an “inadequately educated workforce” as one of the top three obstacles to doing business in the country, after access to financing and corruption. Low unemployment rates back up these concerns. In 2019, unemployment among youths between the ages of 15 and 24 stood at just 3.7 percent, well below the average (12.4 percent) among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states. 2 It was even lower for highly educated workers. Unemployment among those with at least a bachelor’s degree or a short-cycle tertiary education was just 3.5 percent in 2017 , compared with 5.3 percent among those with an upper secondary education and 6.7 percent of those with an elementary or lower secondary education.

Despite the country’s dramatic economic turnaround, troubles remain. For one, the benefits of growth have not always been evenly distributed. Situated almost entirely in Central Asia, although a Western sliver of land extends past the Ural River into Europe, Kazakhstan is the largest landlocked country and, by land mass, the ninth-largest country in the world. Compared with its size, the country’s population is small, just 18.8 million in 2020 , giving it a population density of just 17 people per square mile , among the lowest in the world. Kazakhstan’s population is also very unevenly distributed, with a fifth of the population tightly packed into just three cities. Public services and employment opportunities are similarly concentrated in urban areas, resulting in large economic and social disparities between urban and rural communities.

The nature of Kazakhstan’s economic growth—which has largely been driven by its natural wealth—also presents challenges. With oil and related products accounting for nearly three-quarters of the value of Kazakhstan’s exports, rapid and disruptive swings have long plagued the country’s economy, as periodic demand shocks upend the global price of oil. For example, just a few years after the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy was announced, global overproduction of oil and falling demand caused global oil prices —and Kazakhstan’s economic output—to plummet. Annual GDP growth fell from 4.2 percent in 2014 to just a little more than 1 percent in 2015 and 2016.

The dangers of overdependence on petroleum exports have given new urgency to the government’s ongoing economic diversification efforts. Already in the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy, the government had pledged to make its economy more diversified and knowledge based . Much of that will be driven by education reforms. The strategy prioritizes “ supporting youth, education, and innovative research ,” and calls for the creation of “an education system that promotes the growth of the nation.”

These reforms will build on those of the past. Since the start of the twenty-first century, growing revenues have allowed the government to devise ambitious reforms aimed at improving education and teaching quality, expanding access to poorer students, and aligning the system with international norms. But to fully transform and diversify its economy, the country will need to provide more support to its education system. In its latest report on the progress of Kazakhstan’s transition to a market economy, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) identifies the need to “improve inclusion across regions and for vulnerable population groups” as one of the country’s key priorities in 2021. In elaborating on how those improvements can be achieved, the report is unequivocal: “Reforms in education and vocational education need to accelerate.”

International Student Mobility

Recent developments in Kazakhstan have placed a premium on global awareness and engagement. In response, the government has attempted to cultivate international educational connections by promoting international student mobility, both into and out of Kazakhstan, and encouraging the internationalization of its higher education system.

In its Academic Mobility Strategy in Kazakhstan 2012-2020 , the primary policy document governing the country’s internationalization strategy over the past decade, the government laid out a series of bold internationalization goals. These included having one in five Kazakhstani students engage in some form of study abroad by 2020, and increasing the number of international students studying at Kazakhstani universities by 20 percent each year. Improving the English language skills of students and faculty, expanding the number of programs offered in foreign languages, and promoting links with foreign universities and international organizations were also identified as objectives in the strategy.

The government has backed these plans with concrete actions. It has funded generous international scholarship programs, issued directives requiring institutions to establish international academic partnerships, and joined intergovernmental higher education initiatives, most notably, those associated with the Bologna Process.

The Bologna Process

Kazakhstan’s gradual implementation of the principles underlining the Bologna Accord, which Kazakhstan joined as a full member in 2010 , has had a significant impact on international student mobility. The government has moved to harmonize its education system with those of other members of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), introducing a three-cycle (bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral) qualifications structure and encouraging universities to adopt the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), both of which are discussed in more detail below. These changes have increased intraregional credential recognition and portability, promoting student mobility between Kazakhstan and other EHEA member states.

Kazakhstan’s joining of the Bologna Process has also helped spur the proliferation of international academic and institutional partnerships, an explicit goal of the government, which now requires all universities to establish international partnerships. By the 2020/21 academic year , Kazakhstani universities had signed nearly 6,800 agreements with international partners in 85 countries. The vast majority of these agreements were signed with institutions in other EHEA member states.

Aside from increasing student and scholar mobility, the government hopes that these collaborations will help improve the knowledge and skills of domestic faculty and modernize academic courses and programs. Also helping to further these goals are a growing number of transnational education (TNE) programs, most notably joint and dual degree programs, which allow students to complete part of their studies at a Kazakhstani university and part at an international partner institution. In 2020/21, Kazakhstani universities offered 108 double degree or joint education programs with international partner institutions.

The Bolashak International Scholarship

The government of Kazakhstan also relies on publicly funded scholarships to help further its internationalization goals. Since 1993, the most important has been the Bolashak International Scholarship , which the British Council described as the “ best scholarship program in the world ” at its 2014 Going Global Conference.

The government’s goal for the program is partially revealed by its name, “Bolashak,” which translates into English as “future.” The presidential decree establishing the scholarship states that “Kazakhstan’s transition towards market economy and expansion of international contacts requires personnel with the advanced western education, and it is now necessary to send the most talented youth to study at the top-ranking universities abroad.”

The Bolashak scholarship aims at developing specialists in fields of public importance by funding the education of top students at prestigious overseas universities on the condition that they return to Kazakhstan and work for a minimum of five years after graduation. In exchange, the government pays for the full cost of their overseas studies, covering everything from tuition and books to travel, housing, and other living expenses. The scholarship also funds pre-degree English language training, professional internships, and non-degree training programs in critical fields. Between 1993 and 2017, the government awarded nearly 13,000 Bolashak scholarships .

The scholarship is administered by the JSC Center for International Programs , part of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MESRK). Eligibility criteria have varied widely over the course of the scholarship’s existence. Since 2011 , the scholarship has only funded post-graduate degree programs. In 2014, the center further restricted eligibility by increasing the minimum qualifying International English Language Testing System (IELTS) score and limiting the scholarship to students accepted at universities ranked in the top 200 on the QS World University Rankings , the Times Higher Education World University Rankings , or the Academic Ranking of World Universities .

In collaboration with student representatives, universities, and employers, the JSC Center also determines the specialties that are eligible for scholarship funding. Published data suggest that most Bolashak recipients pursue programs in fields important to the government’s social, economic, and political goals, such as information technology, oil and gas development, pedagogy, petrochemicals, political science, and public administration.

Outbound Mobility

But government funding alone is not solely responsible for the large number of Kazakhstani students studying overseas each year. In 2014, experts estimated that government scholarships funded the studies of only 30 percent of all Kazakhstani students enrolled abroad. The remainder were likely paying out of pocket, a possibility open to growing numbers of Kazakhstani students and their families as the country’s economy and middle class expand.

Those able to afford an international education are likely further pushed to study abroad by a lack of seats at high-quality domestic institutions and by the reports of corruption that have plagued Kazakhstan’s higher education system for decades. The promise of a higher quality education overseas likely attracts a significant proportion of Kazakhstani students who would have otherwise remained at home. In fact, few Kazakhstani international students remain overseas after graduation. Education agents working in Kazakhstan estimate that around seven in ten Kazakhstani students return home immediately after completing their studies.

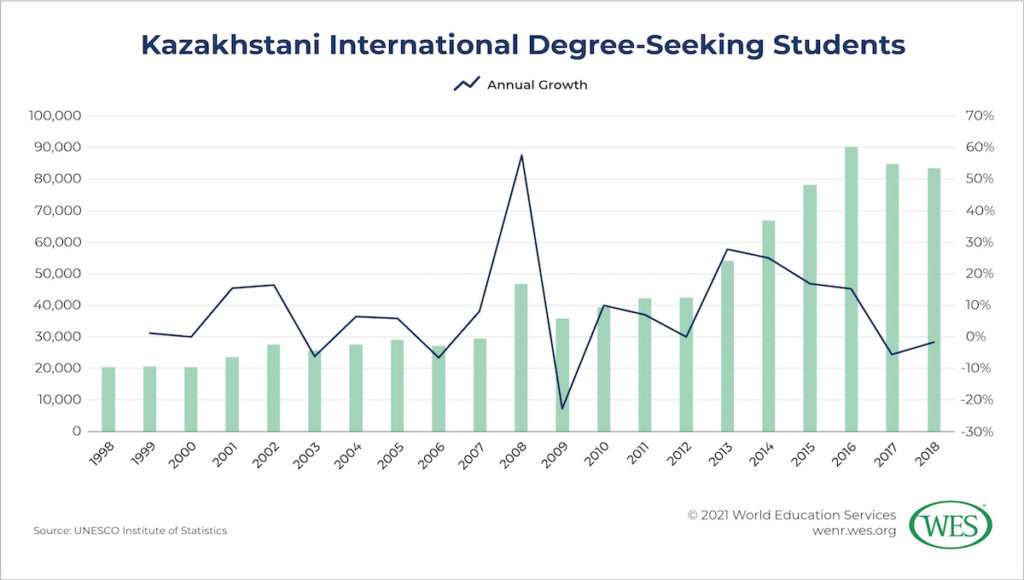

This combination of factors has made Kazakhstan a major source of international students worldwide. In 2018, Kazakhstan was the eighth-largest source of international degree-seeking students globally, according to data compiled by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS). 3 That year, 83,503 Kazakhstani students were studying outside the country. Growth over the past decade has also been particularly impressive. Since 2009, outbound mobility has more than doubled, peaking at 90,213 in 2016 before declining slightly over the past two years.

Still, although many Kazakhstani students are willing to cross the country’s borders to study, most stop immediately on the other side. The vast majority of outbound Kazakhstani students are enrolled in countries directly bordering Kazakhstan, most notably Russia and China. Combining UIS data with the latest numbers provided by China’s Ministry of Education suggests that more than eight in ten international Kazakhstani students were enrolled in one of those two countries. 4

Russia and China

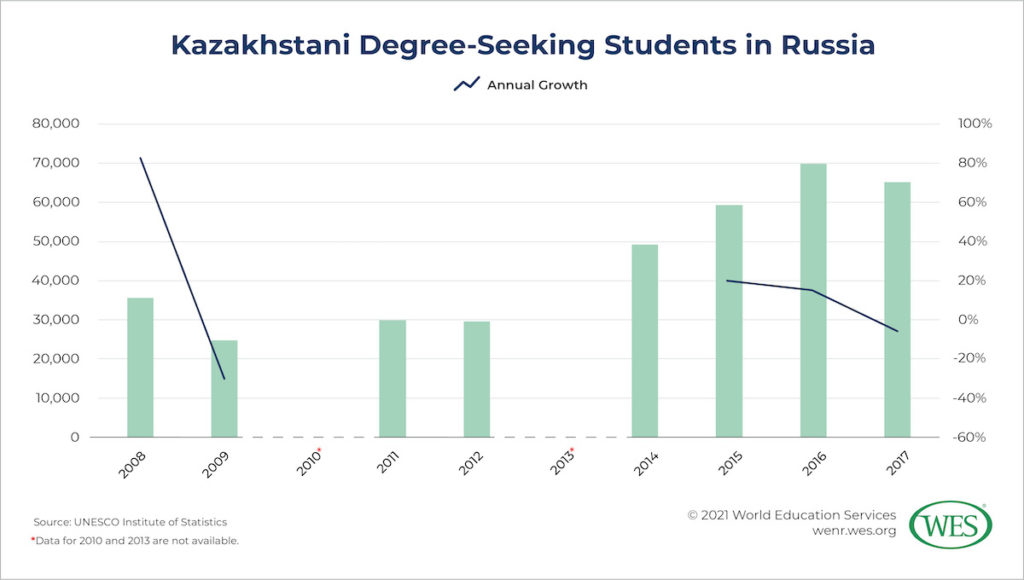

Kazakhstan has long been the leading source of international students in Russia. In 2017, the latest year for which the relevant UIS data is available, Russia hosted 65,237 Kazakhstani students, more than triple the number of Uzbek students (20,862), who make up the next largest contingent of international students in Russia.

Unsurprisingly, the educational connection between Kazakhstan and Russia has a long history. For decades, the government of the Soviet Union supported a unique system of international education and exchange, providing full funding to certain students from constituent republics to study at academic institutions in other Soviet republics, most often in the Russian Federation. After its dissolution, the connection between former Soviet republics continued. In 1998 , Kazakhstan signed a joint agreement with Belarus, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Russia (Tajikistan joined in 2002 ) that aimed at deepening “multilateral cooperation in the fields of education, sciences and cultures” and “setting standards of mutual recognition of education documents, academic degrees and ranks.”

Kazakhstan also cooperates closely with Russia politically, militarily , and economically. Kazakhstan, alongside Belarus and Russia, was a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), an integrative alliance that seeks to promote the free movement of goods and services between a number of East European, Western Asian, and Central Asian countries. The Russian government has also made attracting international students a linchpin of its “soft power” offensive in former Soviet republics, offering scholarships to talented Kazakhstani students , waiving student visa requirements , and allowing applicants to substitute a “ tailor-made ” university entrance examination for Russia’s national university admissions examination, the Unified State Exam. In late 2020, Russia also eased rules regulating international students’ eligibility to work in the country while studying.

Russian institutions also play a prominent part in transnational education (TNE) in Kazakhstan. In the 2020/21 academic year, Russian universities accounted for a third of all international agreements signed by Kazakhstani universities, the highest of any country by far. Although data are unavailable, these collaborative programs likely funnel Kazakhstani students to colleges and universities located in Russia. Other factors, including geographic proximity, cultural and linguistic similarity (more Kazakhstani citizens speak Russian than Kazakh), and the ready availability of affordable and high-quality institutions, likely also attract Kazakhstani students to Russia.

China is also an increasingly prominent destination for Kazakhstani students, although available numbers are not strictly comparable. According to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE’s) Project Atlas , the number of Kazakhstani students studying in China more than doubled in the decade prior to the 2015/16 academic year, growing from 5,666 in 2006/07 to 13,996 in 2015/16, before declining to 11,784 in 2017/18.

China’s continued growth as an international student destination has been bolstered by quality improvements at the nation’s universities and by ambitious government-funded projects, including the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an abbreviation of the project’s official name: the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21 st -Century Maritime Silk Road. Given Kazakhstan’s prominent location on the ancient Silk Road, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Chinese government has directed some of its outreach toward the country, funding the establishment of Confucius Institutes in Kazakhstan and financing scholarships for Kazakhstani students to study in China.

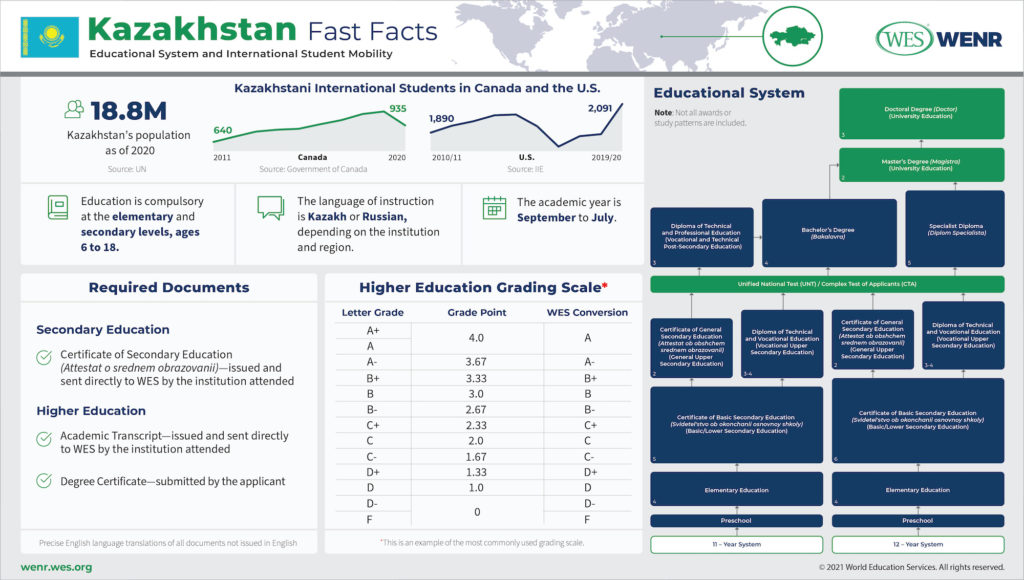

The United States and Canada

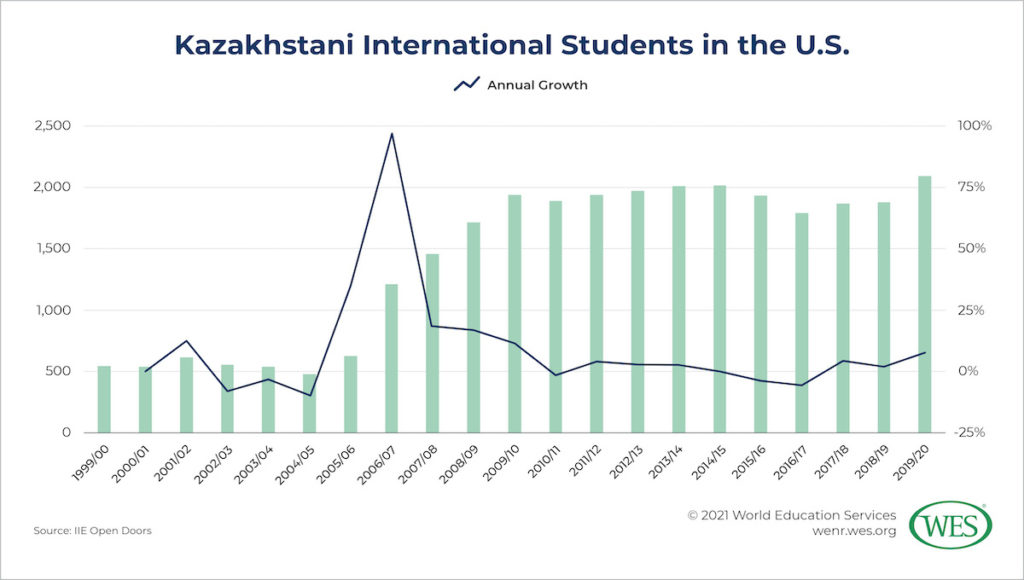

Kazakhstani enrollments in the Western Hemisphere lag sharply behind those in the East. In the United States, they also show few signs of growth. After more than tripling between 2004/05 and 2009/10, when it reached 1,936, enrollment has barely budged since. Just 2,091 Kazakhstani students were enrolled in U.S. higher education institutions in the 2019/20 academic year, according to IIE’s Open Doors report . A plurality (44 percent) of these students are currently enrolled at the undergraduate level , with 35 percent registered in graduate programs, 8 percent in non-degree programs, and 13 percent in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program.

Several reasons likely account for these low numbers, including an abundance of high-quality universities located closer to home, the high cost of colleges and universities in the U.S., and the generally low levels of English proficiency among Kazakhstani students. Despite a strenuous government effort to promote English language competence, introduced by President Nazarbayev in the 2007 Trinity of Languages program, overall English language proficiency in Kazakhstan remains low. The EF English Proficiency Index (EPI) has ranked Kazakhstan in the lowest English proficiency band every year since 2011. Education agents working in Kazakhstan confirm these assessments, reporting that most Kazakhstani students have weak English language skills and usually require preparatory English training before beginning their full-time studies.

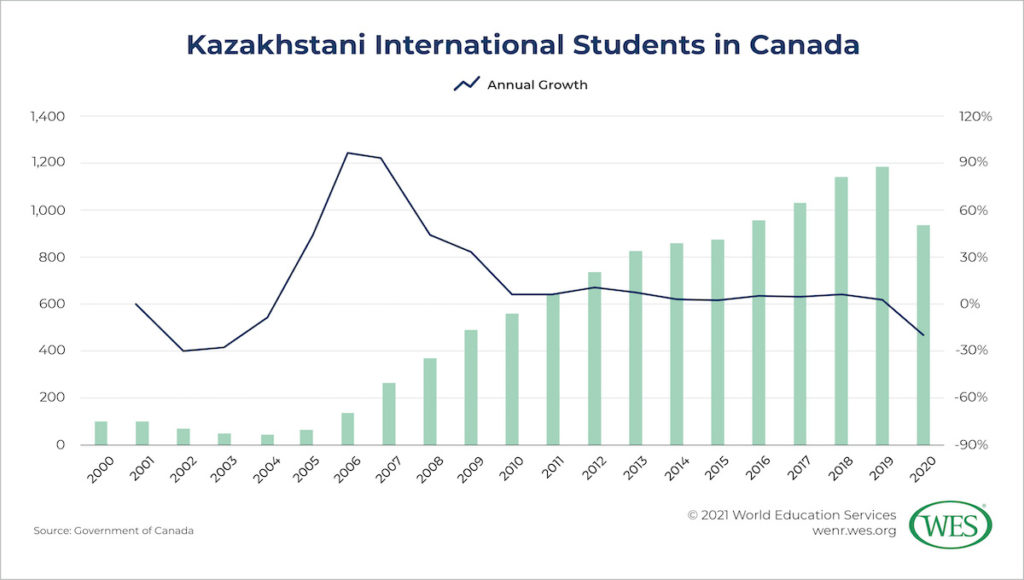

Despite the two countries’ sharing many of the same challenges, Canada’s experience differs sharply from that of the U.S. While still low compared with Kazakhstani enrollments in Russia and China, enrollment in Canada has grown steadily after reaching a nadir of just 45 Kazakhstani students in 2004. According to statistics from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) , enrollment growth has averaged more than 9 percent a year over the past decade, reaching 1,195 in 2019. This trend is hardly unique to Kazakhstani enrollments: Canada’s high-quality and relatively low-cost institutions as well as the country’s more welcoming policies toward both international students and internationally educated immigrants have been attracting growing numbers of students from around the world for years.

Inbound Mobility

For decades, Kazakhstan attracted relatively few international students. Developing its native-born workforce was long the government’s primary reason for promoting internationalization, so it naturally placed far less emphasis on increasing inbound student mobility than it did on boosting outbound flows.

The poor reputation of Kazakhstan’s higher education system also did little to attract international students. A 2017 review by the OECD of Kazakhstan’s higher education system identified a handful of factors discouraging international students from studying in the country, including the generally poor condition of Kazakhstan’s university facilities and services, widespread corruption, and a lack of programs offered in English. 5 The OECD report concludes that, “While it may be possible to increase inbound student numbers by working more closely with aid agencies, until the quality and integrity of higher education are demonstrably improved, substantial increases are unlikely.” As a result, Kazakhstan’s average inbound mobility ratio between 2010 and 2018 stood at just 1.6 percent, well below the world average (2.2 percent), according to UIS data .

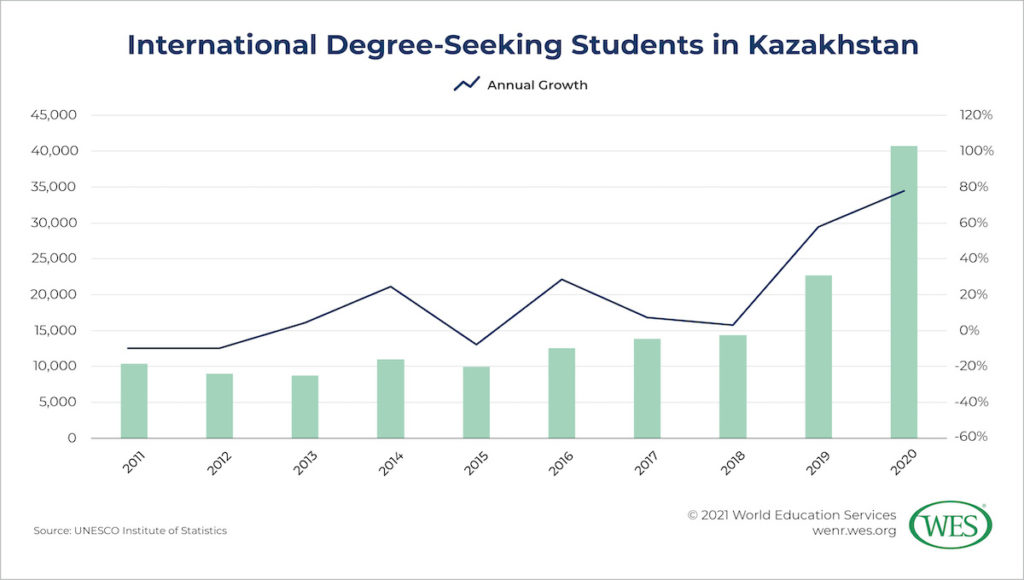

But over the past two years, this picture has changed dramatically. Between 2018 and 2020, the number of international students enrolled in Kazakhstan expanded sharply, growing 184 percent, from 14,332 in 2018 to 40,742 in 2020 . In 2019, its inbound mobility ratio rose to 3.32 percent, an all-time high.

This transformation coincided with a renewed push by the government to attract international students. In early 2018, MESRK announced its plans to transform the country into a “Central Asian educational hub,” setting an ambitious goal of attracting 50,000 international students by 2022.

Data suggest that MESRK’s focus on Central Asia has paid off. Kazakhstan attracts more international students from around the world than any other country in Central Asia. Students from other Central Asian countries also make up the majority of all international students in Kazakhstan. In fact, most of the recent uptick in international students studying in Kazakhstan was driven by an increase in enrollments from Uzbekistan. Between 2018 and 2020 alone, the number of Uzbek students in Kazakhstan grew nearly sevenfold, rising from 3,768 in 2018 to 26,130 in 2020 .

But there are signs that that rapid expansion could prove short-lived. Recently, Uzbekistan has introduced important reforms to its own higher education system, significantly expanding the number of seats and public grants available at the country’s long overcrowded universities. More controversially, government officials have publicly encouraged Uzbek students enrolled abroad to return home , even going so far as to exempt returning students from national university entrance examinations. While it remains to be seen exactly what impact these changes will have on Kazakhstan’s inbound student numbers, early reports suggest that it could be severe.

Outside of Central Asia, India is a significant source of international students in Kazakhstan. Over the past five years, Indian student enrollment has grown by 159 percent, rising from 1,716 in 2016 to 4,453 in 2020. Much of that growth is driven by the demand of Indian students for a medical education, which in India is expensive and hard to access. Even if India’s recent medical reforms manage to increase the country’s ability to train its own medical students, growing political, economic, and cultural cooperation between Kazakhstan and India bode well for the future.

Kazakhstan’s growing popularity lends credence to some of the more optimistic projections of the country’s future role in international student mobility. In a 2012 paper , Geoffrey David Wilmoth, director of the education consulting firm Learning Cities International , argues that Kazakhstan is well poised to transform itself into an international education hub if it can successfully reform its higher education system.

In Brief: The Education System of Kazakhstan

Like the country as a whole, education in Kazakhstan is in transition. Despite decades of government efforts aimed at modernizing and internationalizing the education system, the imprint of its Soviet past remains prominent.

Much of that inheritance is positive. During the Soviet era, the state invested heavily in education, establishing a solid network of kindergarten, elementary, and secondary schools. As a result, literacy and enrollment rates skyrocketed—in 1990, one year before independence, the Kazakh SSR’s elementary gross enrollment ratio stood at 116 percent. The Soviet state also did much to develop higher education in the republic, leaving Kazakhstan 55 universities upon independence.

Still, Soviet-era education had significant shortcomings. Although overall enrollment rates expanded rapidly, access for many rural Kazakhstanis, especially to secondary and post-secondary education, remained limited. At the country’s universities, rigid teaching practices, a narrow focus on developing technical skills, and limited research capacity hampered quality. Strong centralized control over all levels of the education system also made it difficult for educators and administrators to adapt their practices to local conditions or changing circumstances. Finally, upon independence, Kazakhstan’s Soviet past left its education system isolated internationally, as the unique structure of Soviet qualifications diverged sharply from international, or at least Western, standards.

The turmoil of Kazakhstan’s first decade of independence added significantly to the challenges its education system faced. With the economy and public revenues collapsing, the government moved quickly to shift the responsibility for education funding from the public purse to private pockets, rushing through measures to privatize the ownership and financing of education. As a result, low-quality private institutions proliferated. Between 1995, the first year for which data are available, and 2004, government funding for education as a percentage of GDP collapsed, falling from 4.03 percent to 2.26 percent.

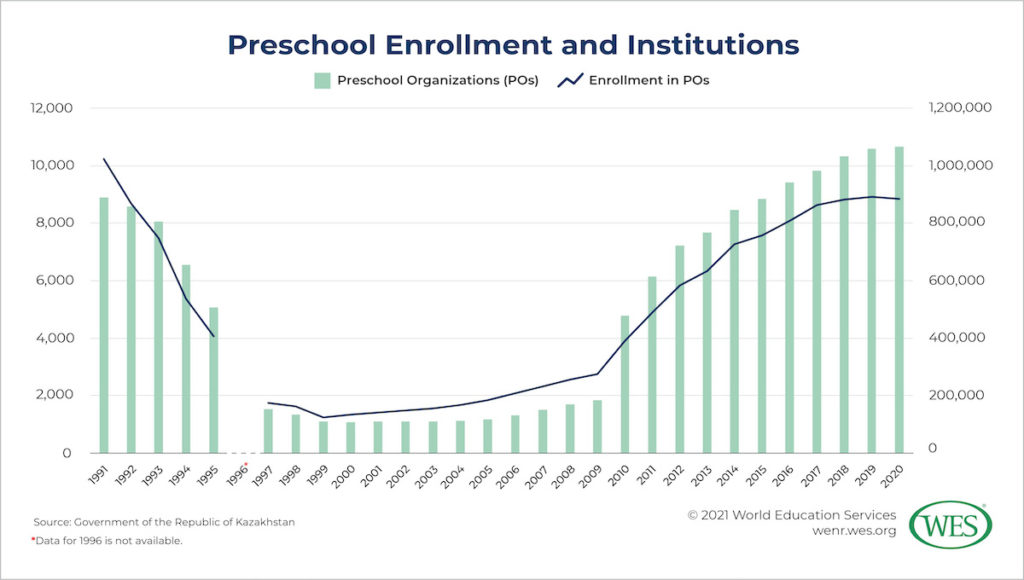

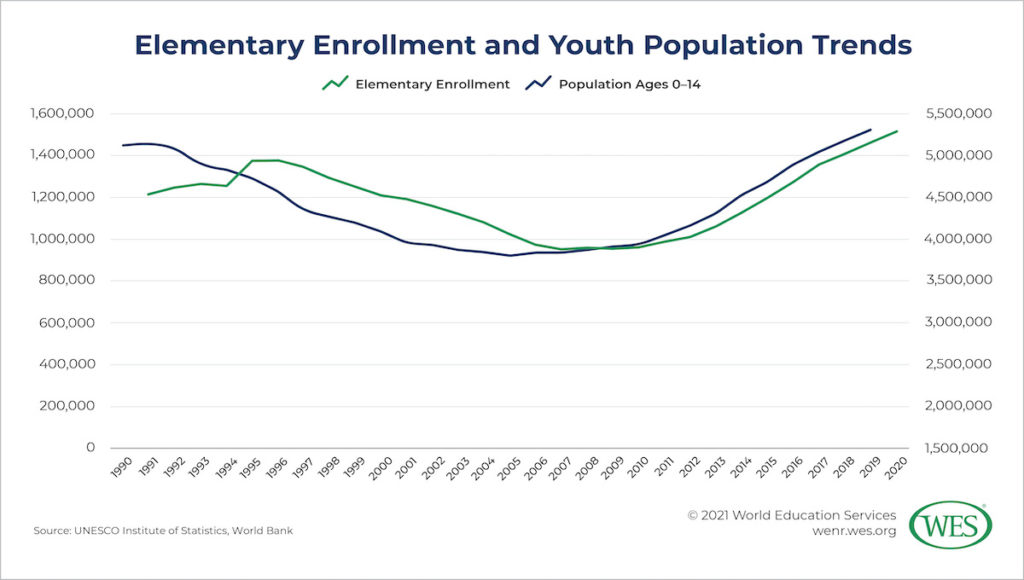

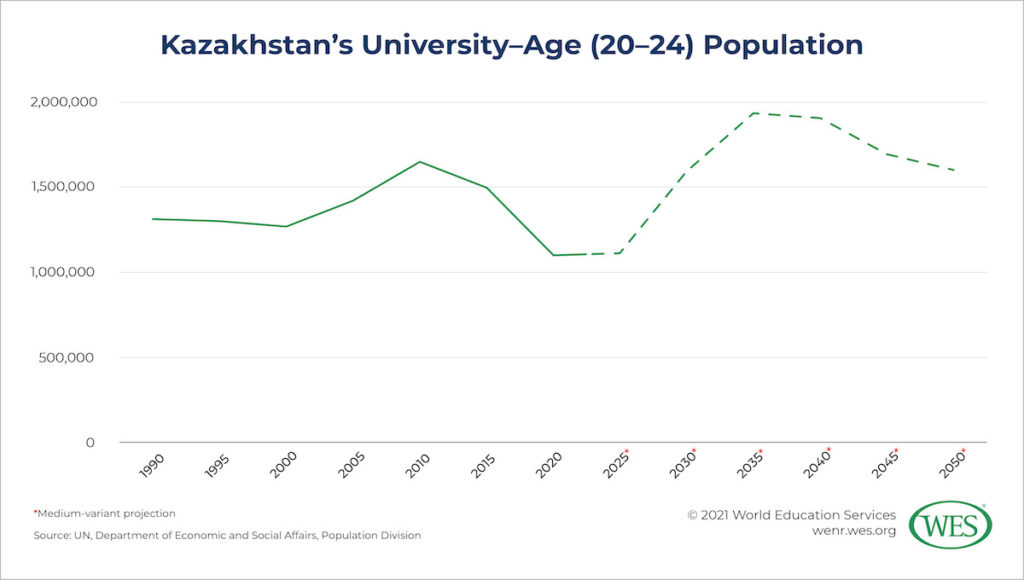

These initial disruptions had varying effects on different levels of the education system. Some, such as pre-elementary and technical and vocational education, were hit hard—institutions rapidly shuttered and enrollment dropped sharply. Other levels were impacted far less, at least in the short term. Starting in the early 2000s, the effects of the demographic contraction of Kazakhstan’s first decade of independence led to declining enrollments across the board.

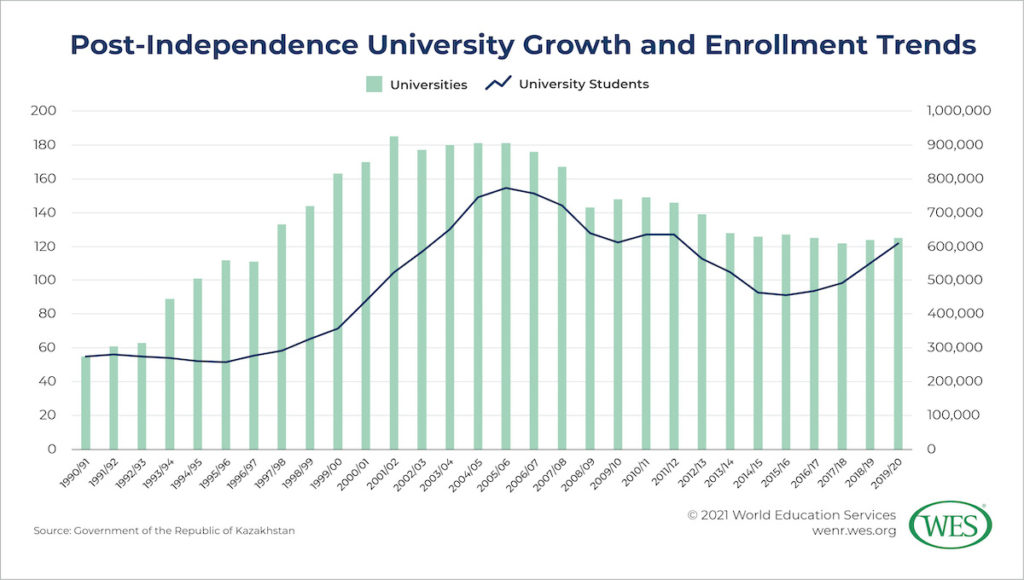

The early 2000s also brought with them a dramatic change in the fortunes of Kazakhstan’s education system. Growing oil wealth expanded the government’s reform capacity, allowing it to embark on a series of sweeping education reforms. With varying levels of success, the government introduced measures aimed at aligning the country’s qualifications framework with EHEA standards and extending the elementary and secondary school cycle to 12 years. With respect to higher education, government officials adopted an “optimization policy” geared toward eliminating the low-quality institutions established since independence.

The results have been impressive. In 2011, Kazakhstan was ranked first worldwide on UNESCO’s Education for All Development Index (EDI), which measures elementary enrollment and completion rates, adult literacy levels, and gender parity in education and literacy. Today, enrollment in elementary and secondary education is nearly universal, with negligible differences in access and achievement by gender. International organizations, such as the OECD , have also praised the Kazakhstani education system for its low repetition rates. Most Kazakhstani students progress smoothly from one grade to the next, with few held back.

But education in the republic still faces significant challenges. Kazakhstani students perform poorly on international standardized assessments, and the country’s high EDI ranking belies large regional and socioeconomic disparities in educational access and achievement. These challenges are exacerbated by low levels of government support for education. Despite the economy’s rapid growth, education funding remains low, reaching just 2.6 percent of GDP in 2018, well below the OECD average (around 5 percent), leaving school infrastructure in much of the country inadequate and underdeveloped. And despite recent changes, the country’s highly centralized system of administration and governance has long challenged Kazakhstan’s educators and reformers.

Administration of the Education System

Kazakhstan is a unitary republic comprising 18 principal administrative divisions: 14 regions ( oblyslar in Kazakh and oblasts in Russian) and four special status cities 6 which possess the same degree of administrative and political autonomy as the oblyslar that surround them. Oblyslar are divided into more than 170 districts, or rayons , which are further subdivided into thousands of villages and rural communities. Despite the recent introduction of decentralization reforms , Kazakhstan’s central government retains tight control over regional and local authorities, with the president appointing regional governors (akims) , the highest regional executive officers, to lead oblyslar and special status cities.

Governance of the education system is similarly centralized. Presidential orders, acts of parliament, and ministerial decrees issued from the nation’s capital tightly regulate all levels of the country’s education system. The 2007 law On Education , plus its 2011 and 2015 amendments, defines the current legal framework governing education in Kazakhstan. Education delivered throughout the country must conform to the law’s decrees.

Since independence, the Executive Office of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MESRK) have assumed primary responsibility for education administration. The Office of the President develops high-level education objectives and manages major projects, spearheading special initiatives like the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS) and Nazarbayev University, discussed in more detail below. The president also plays an important role in developing the nation’s education policies, which are laid out in comprehensive state programs. Over the past decade, two state programs have been particularly decisive: the State Programme of Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2011-2020 (SPED 2011-2020) and the State Programme of Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2016-2019 (SPED 2016-2019).

MESRK’s responsibilities are more wide-ranging, including funding and management of the entire education system as well as its strategic planning. As the nation’s central education authority, MESRK also assumes primary responsibility for ensuring that the education laws and state education programs are implemented throughout the country.

In addition, MESRK regulates course content and program design. At all levels of education, from preschool to higher education, both public and private institutions are required to follow the standards and curriculum guidelines outlined in State Compulsory Standards 7 (SCS). Developed by the National Academy of Education (NAE), an agency of MESRK, SCS prescribe compulsory subjects , teaching methods, and educational programs. The latest SCS— updated in 2017 —seeks to address criticism leveled by, among others, the OECD in its 2018 Education Policy Outlook , that previous curricula focused too much on rote memorization, by instead emphasizing competencies, such as “critical thinking and creativity.”