When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Your Methods

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

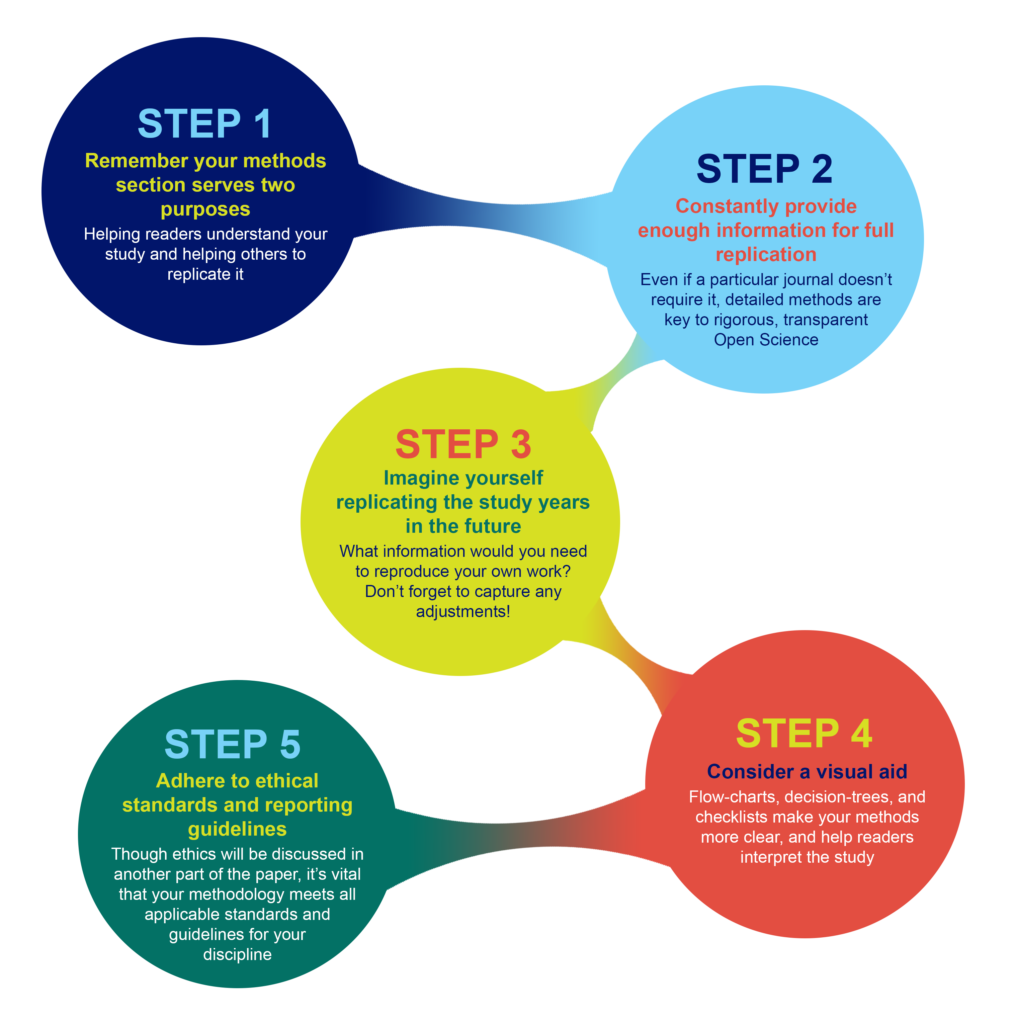

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

PublishingState.com

How to Write the Methodology for Your Journal Article Effectively

Table of contents, a sneak peek, differentiating between methodology and methods, the role of methodology in adding research credibility, how a well-written methodology facilitates peer review, examples of research philosophies and approaches, data collection methods, the significance of discussing your data analysis process, examples of commonly used data analysis techniques, acknowledge potential ethical issues, explain your approach to ethics, discuss data protection, consider cultural sensitivity, step 1: revisit your research questions and objectives, step 2: explain your overall approach and rationale, step 3: describe your research design, step 4: provide details on data collection and instruments, step 5: explain your sampling method, step 6: describe your data analysis procedures, step 7: address ethical considerations, step 8: write in a clear, concise manner, step 9: maintain logical flow and organization, step 10: proofread extensively, being too vague, neglecting to justify choices, inappropriate level of detail, inconsistent structure, ignoring limitations, using jargon, introduction.

This article guides you on how to write the methodology for your journal article effectively and efficiently. In academic publishing , the methodology section is one of the most critical parts of drafting an academic journal article.

You will learn about methodology, why it is vital for your research, and how to craft one that adequately conveys the rationale behind your study design, data collection, and analysis techniques. We will also discuss common pitfalls to avoid when drafting your methodology.

By the end, you will have a solid understanding of how to structure your methodology section perfectly. You can justify your chosen research philosophy, outline your data collection procedures, explain your analysis methods, and address relevant ethical concerns. The tips and examples will help you write a methodology that adds credibility to your work and facilitates future replication studies.

In the coming sections, we will start by clearly defining a methodology and explaining why it is crucial for your academic article. We’ll then provide guidance on identifying your research philosophy and approach, detailing your study design and data collection techniques, discussing your analysis methods, and addressing ethical considerations.

The post will also include a step-by-step walkthrough of how to structure and write your methodology section. You’ll get tips to maintain clarity, precision, and flow in your writing. We’ll end by highlighting common mistakes to avoid when drafting this crucial part of your journal article.

Understanding What a Methodology Is

The methodology section is one of the most important parts of a research paper or journal publishing . It details the procedures and techniques the researcher uses to structure the study and collect and analyze data. But what exactly is a methodology?

In simple terms, the methodology explains the methods used in the research. It provides a description of the approaches, tools, materials, and procedures employed by the researcher to carry out the study. The methodology section allows readers to evaluate a study’s validity and reliability critically.

Some key elements covered in a methodology include:

- Research philosophy ( positivism , interpretivism , etc.)

- Research approach (deductive, inductive, etc.)

- Research design (experimental, survey, case study, etc.)

- Sampling techniques

- Data collection methods (interviews, surveys, observations)

- Data analysis methods (statistical analysis, coding, etc.)

The methodology refers to the overall strategy and rationale for the research process. The methods are specific procedures and techniques for collecting and analyzing data. The methodology provides the reasons for using specific methods and not others in a study. It justifies the research methods.

While the methodology outlines the broad principles and reasoning, the methods section provides meticulous details and a step-by-step account of the techniques applied to gather and make sense of the data. The methods explain how the study was conducted, while the methodology explains why particular methods were used.

To summarize, the methodology describes the overall approach and underpinning research framework, while the methods section offers a detailed account of the practical steps and processes followed in the study.

Why is Methodology Crucial for Your Journal Article?

A sound methodology is the foundation of credible and impactful research. The methodology section demonstrates the validity of your study by detailing how you systematically conducted the research. Here are some key reasons why methodology holds great significance for your journal article:

The methodology provides a window into the research process, allowing readers to evaluate your work critically. A robust methodology indicates that you have carefully considered the research design, data collection, and analysis techniques.

This adds to the overall credibility of the study findings and conclusions. Detailing a logical and scientifically sound methodology reassures readers that you have undertaken a rigorous and unbiased investigation.

During peer review , reviewers scrutinize the methodology to determine the research’s validity, reliability, and reproducibility. A clear, comprehensive, and coherent methodology enables reviewers to assess the technical quality of your work effectively.

Sound methodology allows other researchers to replicate your study and verify the results independently. Replication bolsters the authenticity of your findings. A concise methodology section makes your academic work more amenable to critical peer evaluation and replication – two pillars of the scientific process.

In short, an articulate, well-structured methodology enhances your journal article’s overall cogency and scientific merit. Investing efforts into crafting this crucial section can go a long way in getting your research published and positively received by the academic community. The methodology demonstrates methodological rigor and allows readers to judge the soundness of your work.

Identifying your Research Philosophy and Approach

Defining your research philosophy and approach is crucial when drafting a journal article’s methodology section. Your research philosophy refers to your beliefs about the nature of knowledge and reality, guiding your research. On the other hand, your research approach deals with the overall strategy and plan of action underpinning your study.

Clarifying your philosophical assumptions and approach from the outset is vital for several reasons:

- It helps establish your research’s intent, angle, and perspective from the start.

- It allows readers to understand your worldview and theoretical positioning as a researcher.

- A clear philosophy provides justification for your chosen methods and study design.

- It demonstrates methodological rigor and self-awareness as a researcher.

Some common research philosophies include positivism, interpretivism, pragmatism, constructivism, and post-positivism. Your choice depends on factors like your field of study, research aims, data collection methods, and preferred analysis techniques. When describing your philosophy, explain why it aligns with your research problem and goals.

Similarly, you need to identify and justify your overall research approach. There are three main approaches:

- Quantitative research – objective measures and statistical analysis, focusing on hypothesis testing

- Qualitative research – exploratory, focusing on meanings and experiences

- Mixed methods – combines quantitative and qualitative techniques as needed

Your research approach should logically follow your philosophical assumptions. For instance, a positivist philosophy typically lends itself to a quantitative approach. However, qualitative or mixed methods can also be suitable depending on the context.

The key is to state your chosen philosophy and approach upfront transparently. This provides a conceptual framework for readers to understand your methodology. Any deviations or mixed approaches should adequately justify and align with your research aims.

Here are some examples to illustrate how different research philosophies and approaches are typically described:

- A positivist philosophy with quantitative methods: “This study adopts a positivist philosophy and quantitative approach to test the hypothesis that…”

- An interpretivist philosophy with qualitative methods: “Aligned with an interpretivist philosophy, this study uses qualitative interviews to explore the subjective experiences of…”

- A pragmatist philosophy with mixed methods : “Guided by a pragmatist philosophy, this research employs a mixed methods approach, integrating quantitative surveys and qualitative case studies to…”

The author clearly states their philosophical stance and research approach in each example. This level of transparency is key in the methodology section. Readers can immediately grasp how the researcher’s worldview shapes their inquiry strategy.

In short, articulating your research philosophy and approach provides a conceptual anchor for your methodology. It also demonstrates methodological rigor and alignment between your research aims and techniques. Make sure to provide justification for your chosen philosophy and approach as well.

Detailing Your Research Design and Data Collection Methods

A clear and detailed description of your research design is crucial for a robust methodology section. Your research design refers to the overall strategy you chose to integrate the different components of the study in a coherent way to address your research problem effectively. It provides the blueprint for data collection, measurement, and analysis.

A well-articulated research design shows the logical sequence that connects the empirical data to the initial research questions and, ultimately, the conclusions drawn from the study.

When describing your research design, you need to provide sufficient information for readers to evaluate the appropriateness of your methods and the reliability and validity of your results. Key elements to mention are:

- Research design type (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, observational).

- Study setting.

- Population and sample.

- Variables, constructs, or phenomena under study.

- Any control or comparison groups, if applicable.

You should also justify why your chosen design aligns with your research aims and questions. For example, highlight why an experimental design may be preferred over an observational study to establish causality for your research problem.

In addition to the research design, you must elaborate on the techniques and procedures for collecting the required data. Data collection methods are broadly divided into:

- Primary methods: These involve first-hand data collection by the researcher using methods like interviews, surveys, observations, case studies, focus groups, etc.

- Secondary methods: These rely on already available data from sources like journals, census, organizational records, etc. Examples are literature/desk review, content/document analysis, etc.

For both primary and secondary data collection methods, discuss details like:

- Specific techniques (e.g., online survey, semi-structured interviews, etc.).

- Development and testing of data collection instruments (e.g., survey questionnaires).

- Study sample and sampling technique.

- Procedure adopted for data collection.

- Timeframe for data collection.

Providing this level of detail enables readers to judge the appropriateness of your data collection methods for the research problem and assess potential biases.

A detailed account of your research design and data collection techniques is vital for evaluating your research methodology’s overall rigor and quality.

Explaining Your Data Analysis Technique

The data analysis section is a crucial component of your methodology, demonstrating how you made sense of the data you collected. This section should provide a detailed account of your techniques to analyze your data and arrive at your findings.

Explaining your data analysis process allows readers to evaluate the appropriateness of your techniques. It also enables them to assess the reliability and validity of your results. Some key reasons for detailing your data analysis approach are:

- It demonstrates the logic behind your choice of analysis methods.

- It allows readers to judge the suitability of your analysis techniques for your specific research questions and data types.

- It gives credibility to your findings by providing a transparent account of how you analyzed the data.

- It enables other researchers to replicate your analysis process potentially.

Some commonly used qualitative and quantitative data analysis methods include:

- Thematic analysis – Identifying patterns and themes in qualitative data like interview transcripts.

- Content analysis – Systematically categorizing and analyzing qualitative data like documents or images.

- Discourse analysis – Studying language use and linguistic patterns in textual data.

- Statistical analysis – Techniques like regression, ANOVA, and t-tests for quantitative data.

- Data mining – Finding patterns and relationships in large quantitative datasets.

You should provide details like the tests performed, statistical software or tools used, variables examined, steps followed, etc., to allow readers to understand your analysis approach clearly.

Addressing Ethical Considerations

Ethically conducting research is a crucial component of developing a sound methodology. Here are some tips for effectively addressing ethical considerations in your methodology section:

Briefly acknowledge any potential ethical issues that may arise from your research, such as:

- Obtaining informed consent from participants.

- Protecting anonymity and confidentiality.

- Avoiding deception or distress to participants.

- Handling sensitive topics or vulnerable groups appropriately.

After identifying potential issues, explain how you addressed them ethically. For example:

- Note that participation was voluntary and that participants could withdraw at any time.

- Explain that anonymity was protected by using pseudonyms or codes instead of real names.

- Mention that approval was obtained from an ethics review board.

Discuss steps taken to protect data, such as:

- Storing data securely with password protection and encryption.

- Limiting access to identifiable data.

- Anonymizing data for analysis.

- Securely destroying data after a specified period.

If applicable, explain how you approached your research in a culturally sensitive manner, such as:

- Collaborating with local communities or leaders.

- Adapting methodology to cultural norms and values.

- Using culturally appropriate language and methods.

Addressing ethics builds trust with readers that you conducted your research responsibly. A brief but thoughtful discussion shows you are committed to integrity in your work.

Writing the Methodology: Step-by-Step Guide

Writing the methodology for your journal article is more manageable by breaking it down into clear steps. Here is a step-by-step guide on how to structure and write an effective methodology section:

The first step is to revisit the research questions and objectives you outlined at the start of your paper. Your methodology should clearly describe your specific methods to address these questions and meet the stated objectives.

Provide an overview of the approach you took in conducting your research. For example, did you use a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approach? Explain why you selected this approach and how it aligns with your research questions.

Outline the specific type of research design you utilized, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, qualitative case study, ethnography, etc. Discuss critical details like the study population, variables, data collection timeline, etc.

Thoroughly describe how you collected data for your study. Mention specific instruments, like surveys, interview questions, observation checklists, etc. Include details on their validity and reliability if applicable.

Discuss how you selected participants for your study. Describe the sampling method used (e.g., random, stratified, purposive) and your sample size. Provide key details on the study participants, like demographics.

Outline the specific qualitative or statistical methods you used to analyze the data. Mention any software used and provide details on the specific types of analyses performed in line with your research design.

Discuss how you addressed confidentiality, informed consent, and any other ethical issues that arose during data collection and analysis. Provide information on how you obtained IRB approval, if applicable.

Use straightforward, formal language when writing your methodology section. Avoid unnecessary jargon and clarify discipline-specific terminology. Be concise yet provide sufficient detail and explanation.

Structure your writing in a logical order that flows well. Group related ideas and methods together into paragraphs. Use transitions between paragraphs to guide the reader through the discussion.

Carefully proofread your methodology section several times once completed. Check for typos, grammar errors, inconsistencies, omitted details, and lack of clarity. Refine and revise as needed.

These steps can help you draft a clear, comprehensive, and convincing methodology section for your academic paper. Maintaining precision and coherence in your writing is key to effectively conveying the rigor of your research process.

Common Mistakes to Avoid While Writing Your Methodology

When drafting the methodology section for a journal article, it’s easy to make mistakes that can undermine the credibility of your research. Here are some of the most common pitfalls authors should avoid:

One major mistake is insufficient details about the research methods and procedures. Using vague language like “participants completed surveys” or “data was analyzed” leaves the reader guessing. Be specific when describing sampling techniques, data collection tools, analysis methods, etc.

Simply stating the methods you used is not enough – you need to justify why those particular choices were made. For example, explain why a certain sample size was deemed suitable or why a specific analysis technique was selected. Justifying methodological choices demonstrates thoughtful research design.

Some authors provide excessive trivial detail while skimming over more important aspects. Prioritize key information readers need to evaluate your methodology. For specialized details, you can direct readers to citations or supplementary materials.

The methodology section should follow a logical structure, starting with the research design, sampling strategy, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. Jumping around between topics makes the methods confusing to follow.

No research is perfect, so failing to acknowledge limitations comes across as biased. Briefly discuss any methodological weaknesses, biases, or assumptions made to show readers you have critically assessed your research.

Technical terms and acronyms should be defined since not all readers know them. Strike a balance between using appropriate methodology terminology and ensuring your writing is accessible.

Following these tips will help you avoid common pitfalls when drafting the methodology for your journal article. Remember to be detailed yet concise, justify all choices, use consistent structure, acknowledge limitations, and avoid excessive jargon.

We have concluded this comprehensive guide on writing the perfect methodology section for your academic journal article. Let’s do a quick recap of the key points we covered:

We started by understanding the methodology section – the part of your paper where you explain the logic and rationale behind your research design and methods. A good methodology provides credibility to your findings and allows others to replicate your study.

We then examined the importance of early identification of your research philosophy and approach. Defining your worldview and perspective lays the foundation for your choice of methods. Some common philosophies are positivism, interpretivism, critical research, etc.

Next, we discussed the significance of clearly detailing your research design and data collection techniques. Remember to mention primary research methods like surveys, interviews, experiments, and secondary desk research methods.

You must also explain your qualitative, quantitative, or mixed data analysis methods to show how you made sense of the collected data. The use of appropriate data analysis software should be highlighted.

We also touched upon the ethical dimensions of research. Do acknowledge any ethical considerations and how you addressed them.

The step-by-step guide focused on the best practices for structuring your methodology section. Maintain logical flow, use transitions, and ensure coherence in your writing.

Finally, we explored some common mistakes to avoid – like not justifying methods, unclear writing, and lack of ethical considerations.

As you draft the methodology for your next journal article submission, implement the steps and tips suggested in this guide. Pay attention to the logical flow and articulate your methods clearly. This will go a long way in getting your paper accepted.

Here are a few ways you can continue the conversation:

- Share your top tips for writing a clear, comprehensive methodology section. What strategies have worked for you? What common pitfalls have you encountered, and how did you avoid them?

- Let us know if you have any lingering questions about writing methodologies that weren’t fully addressed in this post. We’re happy to provide more clarity and recommendations.

- Tell us about when you received particularly helpful feedback on a journal article methodology you wrote, either from editors, reviewers, or colleagues. What did you learn from that experience?

- Have you ever had a paper rejected due to a poorly written methodology section? What could you have done differently?

- For seasoned academic writers: share your advice for novice scholars writing their first journal article methodology. What do you wish you had known when you started?

Thank you for reading this guide on how to write the methodology for your journal article. We hope you feel equipped with the knowledge and tools to write a clear, comprehensive, compelling methodology section that will set your academic work apart.

5 thoughts on “How to Write the Methodology for Your Journal Article Effectively”

- Pingback: Handling Author Disputes in Journal Publishing

- Pingback: The Vibrant History of Academic Publishing

- Pingback: Mastering Author Guidelines in Journal Publishing

- Pingback: Handling Manuscript Rejection by Academic Journals | PublishingState.com

- Pingback: How to Write a Research Article | PublishingState.com

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE : Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE : If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE : If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 9:06 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Here's What You Need to Understand About Research Methodology

Table of Contents

Research methodology involves a systematic and well-structured approach to conducting scholarly or scientific inquiries. Knowing the significance of research methodology and its different components is crucial as it serves as the basis for any study.

Typically, your research topic will start as a broad idea you want to investigate more thoroughly. Once you’ve identified a research problem and created research questions , you must choose the appropriate methodology and frameworks to address those questions effectively.

What is the definition of a research methodology?

Research methodology is the process or the way you intend to execute your study. The methodology section of a research paper outlines how you plan to conduct your study. It covers various steps such as collecting data, statistical analysis, observing participants, and other procedures involved in the research process

The methods section should give a description of the process that will convert your idea into a study. Additionally, the outcomes of your process must provide valid and reliable results resonant with the aims and objectives of your research. This thumb rule holds complete validity, no matter whether your paper has inclinations for qualitative or quantitative usage.

Studying research methods used in related studies can provide helpful insights and direction for your own research. Now easily discover papers related to your topic on SciSpace and utilize our AI research assistant, Copilot , to quickly review the methodologies applied in different papers.

The need for a good research methodology

While deciding on your approach towards your research, the reason or factors you weighed in choosing a particular problem and formulating a research topic need to be validated and explained. A research methodology helps you do exactly that. Moreover, a good research methodology lets you build your argument to validate your research work performed through various data collection methods, analytical methods, and other essential points.

Just imagine it as a strategy documented to provide an overview of what you intend to do.

While undertaking any research writing or performing the research itself, you may get drifted in not something of much importance. In such a case, a research methodology helps you to get back to your outlined work methodology.

A research methodology helps in keeping you accountable for your work. Additionally, it can help you evaluate whether your work is in sync with your original aims and objectives or not. Besides, a good research methodology enables you to navigate your research process smoothly and swiftly while providing effective planning to achieve your desired results.

What is the basic structure of a research methodology?

Usually, you must ensure to include the following stated aspects while deciding over the basic structure of your research methodology:

1. Your research procedure

Explain what research methods you’re going to use. Whether you intend to proceed with quantitative or qualitative, or a composite of both approaches, you need to state that explicitly. The option among the three depends on your research’s aim, objectives, and scope.

2. Provide the rationality behind your chosen approach

Based on logic and reason, let your readers know why you have chosen said research methodologies. Additionally, you have to build strong arguments supporting why your chosen research method is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Explain your mechanism

The mechanism encompasses the research methods or instruments you will use to develop your research methodology. It usually refers to your data collection methods. You can use interviews, surveys, physical questionnaires, etc., of the many available mechanisms as research methodology instruments. The data collection method is determined by the type of research and whether the data is quantitative data(includes numerical data) or qualitative data (perception, morale, etc.) Moreover, you need to put logical reasoning behind choosing a particular instrument.

4. Significance of outcomes

The results will be available once you have finished experimenting. However, you should also explain how you plan to use the data to interpret the findings. This section also aids in understanding the problem from within, breaking it down into pieces, and viewing the research problem from various perspectives.

5. Reader’s advice

Anything that you feel must be explained to spread more awareness among readers and focus groups must be included and described in detail. You should not just specify your research methodology on the assumption that a reader is aware of the topic.

All the relevant information that explains and simplifies your research paper must be included in the methodology section. If you are conducting your research in a non-traditional manner, give a logical justification and list its benefits.

6. Explain your sample space

Include information about the sample and sample space in the methodology section. The term "sample" refers to a smaller set of data that a researcher selects or chooses from a larger group of people or focus groups using a predetermined selection method. Let your readers know how you are going to distinguish between relevant and non-relevant samples. How you figured out those exact numbers to back your research methodology, i.e. the sample spacing of instruments, must be discussed thoroughly.

For example, if you are going to conduct a survey or interview, then by what procedure will you select the interviewees (or sample size in case of surveys), and how exactly will the interview or survey be conducted.

7. Challenges and limitations

This part, which is frequently assumed to be unnecessary, is actually very important. The challenges and limitations that your chosen strategy inherently possesses must be specified while you are conducting different types of research.

The importance of a good research methodology

You must have observed that all research papers, dissertations, or theses carry a chapter entirely dedicated to research methodology. This section helps maintain your credibility as a better interpreter of results rather than a manipulator.

A good research methodology always explains the procedure, data collection methods and techniques, aim, and scope of the research. In a research study, it leads to a well-organized, rationality-based approach, while the paper lacking it is often observed as messy or disorganized.

You should pay special attention to validating your chosen way towards the research methodology. This becomes extremely important in case you select an unconventional or a distinct method of execution.

Curating and developing a strong, effective research methodology can assist you in addressing a variety of situations, such as:

- When someone tries to duplicate or expand upon your research after few years.

- If a contradiction or conflict of facts occurs at a later time. This gives you the security you need to deal with these contradictions while still being able to defend your approach.

- Gaining a tactical approach in getting your research completed in time. Just ensure you are using the right approach while drafting your research methodology, and it can help you achieve your desired outcomes. Additionally, it provides a better explanation and understanding of the research question itself.

- Documenting the results so that the final outcome of the research stays as you intended it to be while starting.

Instruments you could use while writing a good research methodology

As a researcher, you must choose which tools or data collection methods that fit best in terms of the relevance of your research. This decision has to be wise.

There exists many research equipments or tools that you can use to carry out your research process. These are classified as:

a. Interviews (One-on-One or a Group)

An interview aimed to get your desired research outcomes can be undertaken in many different ways. For example, you can design your interview as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. What sets them apart is the degree of formality in the questions. On the other hand, in a group interview, your aim should be to collect more opinions and group perceptions from the focus groups on a certain topic rather than looking out for some formal answers.

In surveys, you are in better control if you specifically draft the questions you seek the response for. For example, you may choose to include free-style questions that can be answered descriptively, or you may provide a multiple-choice type response for questions. Besides, you can also opt to choose both ways, deciding what suits your research process and purpose better.

c. Sample Groups

Similar to the group interviews, here, you can select a group of individuals and assign them a topic to discuss or freely express their opinions over that. You can simultaneously note down the answers and later draft them appropriately, deciding on the relevance of every response.

d. Observations

If your research domain is humanities or sociology, observations are the best-proven method to draw your research methodology. Of course, you can always include studying the spontaneous response of the participants towards a situation or conducting the same but in a more structured manner. A structured observation means putting the participants in a situation at a previously decided time and then studying their responses.

Of all the tools described above, it is you who should wisely choose the instruments and decide what’s the best fit for your research. You must not restrict yourself from multiple methods or a combination of a few instruments if appropriate in drafting a good research methodology.

Types of research methodology

A research methodology exists in various forms. Depending upon their approach, whether centered around words, numbers, or both, methodologies are distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, or an amalgamation of both.

1. Qualitative research methodology

When a research methodology primarily focuses on words and textual data, then it is generally referred to as qualitative research methodology. This type is usually preferred among researchers when the aim and scope of the research are mainly theoretical and explanatory.

The instruments used are observations, interviews, and sample groups. You can use this methodology if you are trying to study human behavior or response in some situations. Generally, qualitative research methodology is widely used in sociology, psychology, and other related domains.

2. Quantitative research methodology

If your research is majorly centered on data, figures, and stats, then analyzing these numerical data is often referred to as quantitative research methodology. You can use quantitative research methodology if your research requires you to validate or justify the obtained results.

In quantitative methods, surveys, tests, experiments, and evaluations of current databases can be advantageously used as instruments If your research involves testing some hypothesis, then use this methodology.

3. Amalgam methodology

As the name suggests, the amalgam methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This methodology is used when a part of the research requires you to verify the facts and figures, whereas the other part demands you to discover the theoretical and explanatory nature of the research question.

The instruments for the amalgam methodology require you to conduct interviews and surveys, including tests and experiments. The outcome of this methodology can be insightful and valuable as it provides precise test results in line with theoretical explanations and reasoning.

The amalgam method, makes your work both factual and rational at the same time.

Final words: How to decide which is the best research methodology?

If you have kept your sincerity and awareness intact with the aims and scope of research well enough, you must have got an idea of which research methodology suits your work best.

Before deciding which research methodology answers your research question, you must invest significant time in reading and doing your homework for that. Taking references that yield relevant results should be your first approach to establishing a research methodology.

Moreover, you should never refrain from exploring other options. Before setting your work in stone, you must try all the available options as it explains why the choice of research methodology that you finally make is more appropriate than the other available options.

You should always go for a quantitative research methodology if your research requires gathering large amounts of data, figures, and statistics. This research methodology will provide you with results if your research paper involves the validation of some hypothesis.

Whereas, if you are looking for more explanations, reasons, opinions, and public perceptions around a theory, you must use qualitative research methodology.The choice of an appropriate research methodology ultimately depends on what you want to achieve through your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Research Methodology

1. how to write a research methodology.

You can always provide a separate section for research methodology where you should specify details about the methods and instruments used during the research, discussions on result analysis, including insights into the background information, and conveying the research limitations.

2. What are the types of research methodology?

There generally exists four types of research methodology i.e.

- Observation

- Experimental

- Derivational

3. What is the true meaning of research methodology?

The set of techniques or procedures followed to discover and analyze the information gathered to validate or justify a research outcome is generally called Research Methodology.

4. Where lies the importance of research methodology?

Your research methodology directly reflects the validity of your research outcomes and how well-informed your research work is. Moreover, it can help future researchers cite or refer to your research if they plan to use a similar research methodology.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Using AI for research: A beginner’s guide

Journal Article: Methods

Criteria for success.

A successful Methods section:

- provides the reasons for choosing your methodology

- allows readers to confirm your findings through replication

Compare Authentic Annotated Examples for Methods and Results . Note the correspondence of subheadings between the two sections.

Identify Your Purpose

The purpose of a Methods section is to describe how the questions/knowledge gap posed in the Introduction were answered in the Results section. Not all readers will be interested in this information. For those who are, the Methods section has two purposes:

1. Allow readers to judge whether the results and conclusions of the study are valid.

The interpretation of your results depends on the methods you used to obtain them. A reader who is skeptical of your results will read your Methods section to see if they can be trusted. They’ll want to know that you chose the most appropriate methods and performed the necessary controls. Without this content, skeptical readers might think your data and any conclusions drawn from them are unreliable.

2. Allow readers to repeat the study.

For readers interested in replicating your study, the Methods section should provide enough information for them to obtain the same or similar results.

Analyze your audience

Typically, only readers in your field will want to replicate your study or have the knowledge to assess your methodology. More general audiences will read the Introduction and then proceed straight to the Results. You can therefore assume that people reading your Methods understand methodologies that are frequently used in your field. To gauge the level of detail necessary for a given method, you can look at articles previously published in your target journal.

If your paper is designed to appeal to experts in more than one field, you still need to write your Methods for a single set of experts. For example, say you applied a novel computational approach to gain new insight into a well-characterized biological system. Is your goal to get to show biologists the value of your computational tool or to show computational scientists how they can help study biology? In the former case, assume less computational expertise: provide more extensive explanations for how methods work and why they were chosen.

State the reasons for choosing your methodology

A reader looking to assess your methodology will read your Methods section to judge your experimental design. When describing your approach, place more emphasis on how you applied a method rather than on how you performed the method. For example, you don’t need to explain how to perform a western blot, but you might want to describe why a western blot is an appropriate approach for the task at hand (and, potentially, why you didn’t use another method).

Use subheadings to organize content

As recommended for your Results section , use subheadings within your Methods to group related experiments and establish a logical flow. Write your Results section first, and then follow the order of Results subheadings when writing your Methods. The parallel structure will make it easy for readers to locate corresponding information in the two sections.

Subheadings for Methods and Results may not exactly correspond. Sometimes you may need multiple Methods subheadings to explain one Results subheading. Other times, one Method subheading is enough to explain multiple Result subheadings.

Provide minimal essential detail

Provide only those details necessary for a reader to replicate the experiments presented in your study; anything more is extraneous. Remember that readers use Methods to help them assess the validity of your conclusions, so specify any methodological details that might cause someone to reach a different conclusion.

You can cite papers for standard methods, but any modifications or alterations should be clearly stated. When citing methods, cite the original paper in which a method was described instead of a paper that used the method. This helps avoid chains of citations that your reader must follow to find information about the method.

Avoid “we did…” or “the authors did…”

The Methods section should focus on the experiments, not the authors. Avoid phrasing your experiments as “We/The authors did ___”, even if it requires you to write in the passive voice.

“Samples were processed with standard DNA extraction protocols.”

“We processed the samples with standard DNA extraction protocols.”

This content was adapted from from an article originally created by the MIT Biological Engineering Communication Lab .

Resources and Annotated Examples

Annotated example 1.

Zetsche et al. , "Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease...", Cell 2015. Compare to the annotated examples in the Results section. 2 MB

- Interlibrary Loan and Scan & Deliver

- Course Reserves

- Purchase Request

- Collection Development & Maintenance

- Current Negotiations

- Ask a Librarian

- Instructor Support

- Library How-To

- Research Guides

- Research Support

- Study Rooms

- Research Rooms

- Partner Spaces

- Loanable Equipment

- Print, Scan, Copy

- 3D Printers

- Poster Printing

- OSULP Leadership

- Strategic Plan

Scholarly Articles: How can I tell?

- Journal Information

- Literature Review

- Author and affiliation

- Introduction

- Specialized Vocabulary

Methodology

- Research sponsors

- Peer-review

The methodology section or methods section tells you how the author(s) went about doing their research. It should let you know a) what method they used to gather data (survey, interviews, experiments, etc.), why they chose this method, and what the limitations are to this method.

The methodology section should be detailed enough that another researcher could replicate the study described. When you read the methodology or methods section:

- What kind of research method did the authors use? Is it an appropriate method for the type of study they are conducting?

- How did the authors get their tests subjects? What criteria did they use?

- What are the contexts of the study that may have affected the results (e.g. environmental conditions, lab conditions, timing questions, etc.)

- Is the sample size representative of the larger population (i.e., was it big enough?)

- Are the data collection instruments and procedures likely to have measured all the important characteristics with reasonable accuracy?

- Does the data analysis appear to have been done with care, and were appropriate analytical techniques used?

A good researcher will always let you know about the limitations of his or her research.

- << Previous: Specialized Vocabulary

- Next: Results >>

- Last Updated: Apr 15, 2024 3:26 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.oregonstate.edu/ScholarlyArticle

Contact Info

121 The Valley Library Corvallis OR 97331–4501

Phone: 541-737-3331

Services for Persons with Disabilities

In the Valley Library

- Oregon State University Press

- Special Collections and Archives Research Center

- Undergrad Research & Writing Studio

- Graduate Student Commons

- Tutoring Services

- Northwest Art Collection

Digital Projects

- Oregon Explorer

- Oregon Digital

- ScholarsArchive@OSU

- Digital Publishing Initiatives

- Atlas of the Pacific Northwest

- Marilyn Potts Guin Library

- Cascades Campus Library

- McDowell Library of Vet Medicine

Holman Library

Research Guide: Scholarly Journals

Methodology.

- Why Use Scholarly Journals?

- What does "Peer-Reviewed" mean?

- What is *NOT* a Scholarly Journal Article?

- Interlibrary Loan for Journal Articles

- Introduction: Hypothesis/Thesis

- Reading the Citation

- Authors' Credentials

- Literature Review

- Results/Data

- Discussion/Conclusions

- APA Citations for Scholarly Journal Articles

- MLA Citations for Scholarly Journal Articles

Reviewing the methodology section

The image below show the Methods section of the article, where the authors are outlining how they carried out their study.

(click on image to enlarge)

- The Methodology section of the article describes the procedures, or methods, that were used to carry out the research study.

- The methodology the authors follow will vary according to the discipline, or field of study, the research relates to.

- Types of methodology include case studies, scientific experiments, field studies, focus groups, and surveys.

- You may not need to spend much time focusing on the details of this section unless you want to replicate the experiment yourself.

- << Previous: Literature Review

- Next: Results/Data >>

- Last Updated: May 4, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.greenriver.edu/scholarlyjournals

How To Write The Methodology Chapter

The what, why & how explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021 (Updated April 2023)