Online Dating: A Critical Analysis From the Perspective of Psychological Science

Read the Full Text

Although the authors find that online dating sites offer a distinctly different experience than conventional dating, the superiority of these sites is not as evident. Dating sites provide access to more potential partners than do traditional dating methods, but the act of browsing and comparing large numbers of profiles can lead individuals to commoditize potential partners and can reduce their willingness to commit to any one person. Communicating online can foster intimacy and affection between strangers, but it can also lead to unrealistic expectations and disappointment when potential partners meet in real life. Although many dating sites tout the superiority of partner matching through the use of “scientific algorithms,” the authors find that there is little evidence that these algorithms can predict whether people are good matches or will have chemistry with one another.

The authors’ overarching assessment of online dating sites is that scientifically, they just don’t measure up. As online dating matures, however, it is likely that more and more people will avail themselves of these services, and if development — and use — of these sites is guided by rigorous psychological science, they may become a more promising way for people to meet their perfect partners.

Hear author Eli J. Finkel discuss the science behind online dating at the 24th APS Annual Convention .

About the Authors

Editorial: Online Dating: The Current Status —and Beyond

By Arthur Aron

I agree wholeheartedly that so-called scientific dating sites are totally off-base. They make worse matches than just using a random site. That’s because their matching criteria are hardly scientific, as far as romance goes. They also have a very small pool of educated, older men, and lots more women. Therefore they often come up with no matches at all, despite the fact that women with many different personality types in that age group have joined. They are an expensive rip-off for many women over 45.

Speaking as someone who was recently “commoditized” by who I thought was a wonderful man I met on a dating site, I find that the types of people who use these services are looking at the wrong metrics when they seek out a prospective love interest. My mother and father had very few hobbies and interests in common, but because they shared the same core values, their love endured a lifetime. When I got dumped because I didn’t share my S.O.’s interests exactly down the line, I realized how dangerous this line of thinking truly is, how it marginalizes people who really want to give and receive love for more important reasons.

I met a few potential love interests online and I never paid for any matching service! I did my own research on people and chatted online within a site to see if we had things in common. If we had a few things in common, we exchanged numbers, texted for a while, eventually spoke on the phone and if things felt right, we’d meet in a public place to talk. If that went well, we would have another date. I am currently with a man I met online and we have been together for two years! We have plans to marry in the future. But there is always the thought that if this doesn’t work out, how long will it take either of us to jump right back online to find the next possible love connection? I myself would probably start looking right away since looking for love online is a lengthy process!

I knew this man 40 years ago as we worked in the same agency for two years but never dated. Last November 2013 I saw his profile on a dating site. My husband had died four years ago and his wife died 11 years ago. We dated for five months. I questioned him about his continued online search as I had access to his username. Five months into the friendship he told me he “Was looking for his dream women in cyberspace”. I think he has been on these dating sites for over 5 years. Needless to say I will not tolerate this and it was over. I am sad, frustrated and angry how this ended as underneath all of his insecurities, unresolved issues with his wife’s death he is a good guy. I had been on these dating sties for 2 and 1/2 years and now I am looking at Matchmaking services as a better choice in finding a “Better good guy”.

I refer to these sites as “Designer Dating” sites. I liken the search process to ‘Window Shopping’. No-one seems very interested in making an actual purchase or commitment. I notice that all the previous comments are from women only. I agree with the article that says essentially, there are too many profiles and photos. Having fallen under this spell myself…”Oh, he’s nice but I’m sure there’s something better on the next page…” Click. Next. And on it goes. The term Chemistry gets thrown around a lot. I don’t know folks. I sure ain’t feelin’ it. Think I’ll go hang out with some friends now.

Stumbling upon this article during research for my Master thesis and I am curious: Would you use an app, that introduces a new way of dating, solely based on your voice and who you are, rather than how you look like? To me, we don’t fall in love with someone because of their looks (or their body mass index for that matter) or because of an algorithm, but because of the way somebody makes you feel and the way s.o. makes you laugh. At the end of the day, it really doesn’t matter if someone has blue or brown eyes and my experience is, that most people place fake, manipulated or outdated pictures online to sell someone we don’t really are. And we are definitely more than our looks. I found my partner online and we had no picture of each other for three months – but we talked every night for hours…. fell in love and still are after 10 years… We met on a different level and got aligned long before we met. So, the question is, would you give this way of meeting someone a chance… an app where you can listen in to answers people give to questions other user asked before and where you can get a feeling for somebody before you even see them?

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

New Report Finds “Gaps and Variation” in Behavioral Science at NIH

A new NIH report emphasizes the importance of behavioral science in improving health, observes that support for these sciences at NIH is unevenly distributed, and makes recommendations for how to improve their support at the agency.

APS Advocates for Psychological Science in New Pandemic Preparedness Bill

APS has written to the U.S. Senate to encourage the integration of psychological science into a new draft bill focused on U.S. pandemic preparedness and response.

APS Urges Psychological Science Expertise in New U.S. Pandemic Task Force

APS has responded to urge that psychological science expertise be included in the group’s personnel and activities.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

Essay on Positive & Negative Effects of Online Dating

January 12, 2018 by Study Mentor Leave a Comment

Online dating is a very common occurrence among the youth of today and almost every other person is constantly resorting to this option for various reasons.

Like every other consequence of the internet era, online dating has both its advantages and disadvantages and we must not be clouded by any preconceived notions while we are evaluating its effects.

Some people are extremely apprehensive of the anonymity which is allowed to one by the procedure of online dating as such, but this cannot be denied that many a perfect match had been also made by dating sites and several social networks, but one can never completely deny the obvious risk that online dating brings along with it.

Table of Contents

Ways in which online dating occurs

Online dating started to spread itself mostly through social media and social networking and all such sites which permit the same- starting from the times of Orkut to the modern age of Facebook , Twitter , and Instagram . There are also various virtual chat rooms which might facilitate online dating as well.

Moreover, there are several mobile applications specifically designed to help people find suitable partners for online dating, etc. The most prominent example of such an application will be Tinder, which is now very popular among the Indian youth too, especially the college goers.

There are other similar apps too but they do not concentrate solely on the prospect of online dating. However, there are many software’s and applications dedicated to online dating, chatting, and for other such purposes.

However, online dating is not an entirely new phenomenon, as it had started in the medieval times in the form of sending letters to carry out more or less a similar function. It has merely redecorated and rejuvenated itself in various newer forms over the ages and is now highly digitalised.

Negative effects of Online Dating

The biggest problem of online dating is when two people get acquainted, and then attracted to practically someone who is a complete stranger to them. This can cause many risks and eventually be very harmful to the individual, who is entering in any such relations without being completely aware of the other person’s actual identity. Many people create different fake profiles on social media sites to entrap such vulnerable individuals.

In such a way, they can easily make such vulnerable people trust them and not perceive their malicious intentions. Many cases have been reported that through this way, people have been blackmailed, robbed, and exploited in many other ways- all of them being equally harmful to one’s resources and reputation.

Another effect can be misunderstandings between the people involved in any such relations. Any such relationship which is built merely on a virtual premise can never possibly inform both the involved parties about each other’s identities completely, thus there is an inevitable tendency of misconceptions to creep in, which might result in both underestimating or overestimating someone and their abilities.

This can be the root cause behind such misunderstandings, as texting and virtual messaging are two most important and effective ways to misrepresent the actual message one is trying to convey in plenty of situations. Many a times, it is also seen that males have formed accounts with the fake name and images of females, and vice versa, to further trick people for reasons which are certainly not very humble or altruistic.

The different MMS scams which surface every now and then can also be seen as an adverse effect of online dating, as on sites such as Facebook, etc. it is quite easy to download one’s pictures and use them for evil purposes or to blackmail someone as such.

However, that particular website had recently taken some measures to try and prevent such acts through some safety measures, but the problem has not been yet curbed in its entirety. Therefore, further safety measures are still required.

Positive effects of online dating

However, at times, online dating can also link two people aptly based on their likes and interests, and it can turn out to be a very good match indeed which might turn out to be fruitful in the future. Needless to say, all relationships need certain qualities to prosper and progress, but how they are acquainted to each other can also play a big role in advancing their relationship as such.

For example, social media is often used by people to convey their feelings and opinions on different issues, and this is how we find like-minded people or people we can engage in a healthy debate and discussion with. This can go a long way in establishing a proper relationship between them, and thus leading to online dating.

Also, online dating might also keep aside one’s prejudices before they delve into any relationship as in this case, one likes a person only on the basis of their identity and not on other grounds such as their family identity, their financial status, etc. which can otherwise attract people in other forms of dating, besides the virtual form being discussed in this essay.

Therefore, in a certain way, online dating might eliminate relationships based on false premises and a pretentious sense of attraction between people.

It cannot be really said that online dating is completely a bad thing; likewise, it cannot be referred to be something entirely positive. It is obviously a blend of both its diverse pros and cons, but we need to realize that either of these over weigh the other at certain situations, and therefore, the social and geographical setting and context of online dating also highly influences how the system fairs out to be eventually.

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

The Impact of Dating Apps on Young Adults: Evidence From Tinder

MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 6833-22

71 Pages Posted: 17 Oct 2022 Last revised: 26 May 2024

Berkeren Buyukeren

Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF); Libera Universita Internazionale degli Studi Sociali - LUISS Guido Carli

Alexey Makarin

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) - Sloan School of Management; Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF); Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR)

Case Western Reserve University

Date Written: October 6, 2022

Online dating apps have become a central part of the dating market over the past decade, yet their broader effects remain unclear. We analyze the impact of Tinder, the pioneer and market leader in the dating app space, on a segment of the population that was among the earliest adopters of this technology: college students. For identification, we rely on the fact that Tinder's initial marketing strategy centered on Greek organizations (fraternities and sororities) within college campuses. Using a comprehensive survey containing more than 1.1 million responses, we estimate a difference-in-differences model comparing student outcomes before and after Tinder's full-scale launch and across students' membership in Greek organizations. We show that Tinder's introduction led to a sharp, persistent increase in the frequency of sexual activity, but with no corresponding impact on the likelihood of relationship formation. Inequality in dating outcomes increased among male students but not among female students. Further, we observe a rise in the incidences of sexual assaults and sexually transmitted diseases. However, despite these changes, Tinder's introduction did not worsen students' mental health and may have even led to improvements for female students. These results suggest that the transformation of dating due to dating apps has far-reaching and nuanced effects on young adults.

Keywords: Online platforms, dating market, Tinder, health, mobile technology

JEL Classification: D91, I12, I23, J10, L82, L86

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF) ( email )

Via Due Macelli, 73 Rome, 00187 Italy

HOME PAGE: http://https://berkerenbuyukeren.github.io/

Libera Universita Internazionale degli Studi Sociali - LUISS Guido Carli ( email )

United States

Alexey Makarin (Contact Author)

Massachusetts institute of technology (mit) - sloan school of management ( email ).

100 Main Street E62-416 Cambridge, MA 02142 United States

HOME PAGE: http://https://alexeymakarin.github.io/

Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF)

Via Sallustiana, 62 Rome, Lazio 00187 Italy

Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) ( email )

London United Kingdom

Case Western Reserve University ( email )

10900 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, OH 44106 United States

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, mit sloan school of management working paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Behavioral & Experimental Economics eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Psychology Research Methods eJournal

Developmental psychology ejournal, health psychology ejournal.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Dating Apps and Their Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates: A Systematic Review

The emergence and popularization of dating apps have changed the way people meet and interact with potential romantic and sexual partners. In parallel with the increased use of these applications, a remarkable scientific literature has developed. However, due to the recency of the phenomenon, some gaps in the existing research can be expected. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of the psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. A search was conducted in different databases, and we identified 502 articles in our initial search. After screening titles and abstracts and examining articles in detail, 70 studies were included in the review. The most relevant data (author/s and year, sample size and characteristics, methodology) and their findings were extracted from each study and grouped into four blocks: user dating apps characteristics, usage characteristics, motives for use, and benefits and risks of use. The limitations of the literature consulted are discussed, as well as the practical implications of the results obtained, highlighting the relevance of dating apps, which have become a tool widely used by millions of people around the world.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, the popularization of the Internet and the use of the smartphone and the emergence of real-time location-based dating apps (e.g., Tinder, Grindr) have transformed traditional pathways of socialization and promoted new ways of meeting and relating to potential romantic and/or sexual partners [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

It is difficult to know reliably how many users currently make use of dating apps, due to the secrecy of the developer companies. However, thanks to the information provided by different reports and studies, the magnitude of the phenomenon can be seen online. For example, the Statista Market Forecast [ 5 ] portal estimated that by the end of 2019, there were more than 200 million active users of dating apps worldwide. It has been noted that more than ten million people use Tinder daily, which has been downloaded more than a hundred million times worldwide [ 6 , 7 ]. In addition, studies conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts have shown that around 40% of single adults are looking for an online partner [ 8 ], or that around 25% of new couples met through this means [ 9 ].

Some theoretical reviews related to users and uses of dating apps have been published, although they have focused on specific groups, such as men who have sex with men (MSM [ 10 , 11 ]) or on certain risks, such as aggression and abuse through apps [ 12 ].

Anzani et al. [ 1 ] conducted a review of the literature on the use of apps to find a sexual partner, in which they focused on users’ sociodemographic characteristics, usage patterns, and the transition from online to offline contact. However, this is not a systematic review of the results of studies published up to that point and it leaves out some relevant aspects that have received considerable research attention, such as the reasons for use of dating apps, or their associated advantages and risks.

Thus, we find a recent and changing object of study, which has achieved great social relevance in recent years and whose impact on research has not been adequately studied and evaluated so far. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. By doing so, we intend to assess the state of the literature in terms of several relevant aspects (i.e., users’ profile, uses and motives for use, advantages, and associated risks), pointing out some limitations and posing possible future lines of research. Practical implications will be highlighted.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 13 , 14 ], and following the recommendations of Gough et al. [ 15 ]. However, it should be noted that, as the objective of this study was to provide a state of the art view of the published literature on dating apps in the last five years and without statistical data processing, there are several principles included in the PRISMA that could not be met (e.g., summary measures, planned methods of analysis, additional analysis, risk of bias within studies). However, following the advice of the developers of these guidelines concerning the specific nature of systematic reviews, the procedure followed has been described in a clear, precise, and replicable manner [ 13 ].

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We examined the databases of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Medline, as well as PsycInfo and Psycarticle and Google Scholar, between 1 March and 6 April 2020. In all the databases consulted, we limited the search to documents from the last five years (2016–2020) and used general search terms, such as “dating apps” and “online dating” (linking the latter with “apps”), in addition to the names of some of the most popular and frequently used dating apps worldwide, such as “tinder”, “grindr”, and “momo”, to identify articles that met the inclusion criteria (see below).

The selection criteria in this systematic review were established and agreed on by the two authors of this study. The database search was carried out by one researcher. In case of doubt about whether or not a study should be included in the review, consultation occurred and the decision was agreed upon by the two researchers.

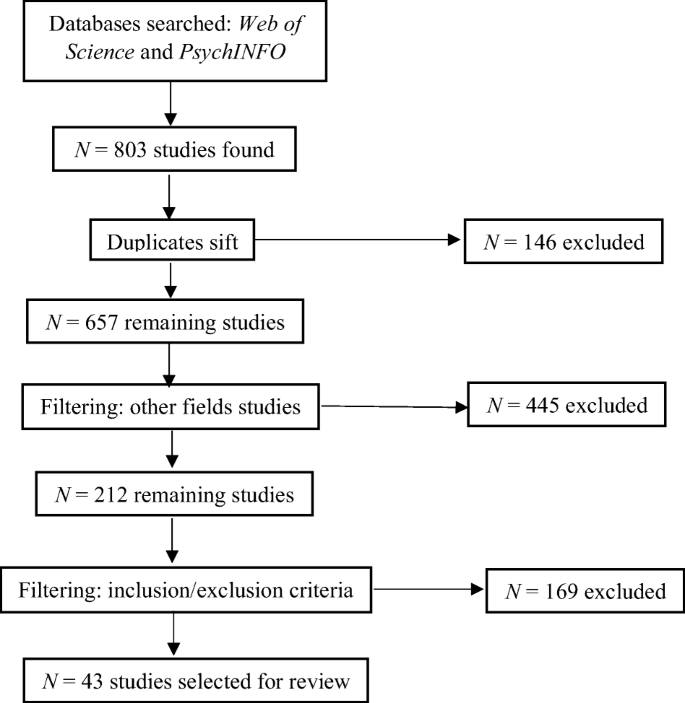

Four-hundred and ninety-three results were located, to which were added 15 documents that were found through other resources (e.g., social networks, e-mail alerts, newspapers, the web). After these documents were reviewed and the duplicates removed, a total of 502 records remained, as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1 . At that time, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) empirical, quantitative or qualitative articles; (2) published on paper or in electronic format (including “online first”) between 2016 and 2020 (we decided to include articles published since 2016 after finding that the previous empirical literature in databases on dating apps from a psychosocial point of view was not very large; in fact, the earliest studies of Tinder included in Scopus dated back to 2016; (3) to be written in English or Spanish; and (4) with psychosocial content. No theoretical reviews, case studies/ethnography, user profile content analyses, institutional reports, conference presentations, proceeding papers, etc., were taken into account.

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

Thus, the process of refining the results, which can be viewed graphically in Figure 1 , was as follows. Of the initial 502 results, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) pre-2016 documents (96 records excluded); (2) documents that either did not refer to dating apps or did so from a technological approach (identified through title and abstract; 239 records excluded); (3) published in a language other than English or Spanish (10 records excluded); (4) institutional reports, or analysis of the results of such reports (six records excluded); (5) proceeding papers (six records excluded); (6) systematic reviews and theoretical reflections (26 records excluded); (7) case studies/ethnography (nine records excluded); (8) non-empirical studies of a sociological nature (20 records excluded); (9) analysis of user profile content and campaigns on dating apps and other social networks (e.g., Instagram; nine records excluded); and (10) studies with confusing methodology, which did not explain the methodology followed, the instruments used, and/or the characteristics of the participants (11 records excluded). This process led to a final sample of 70 empirical studies (55 quantitative studies, 11 qualitative studies, and 4 mixed studies), as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1 .

2.2. Data Collection Process and Data Items

One review author extracted the data from the included studies, and the second author checked the extracted data. Information was extracted from each included study of: (1) author/s and year; (2) sample size and characteristics; (3) methodology used; (4) main findings.

Table 1 shows the information extracted from each of the articles included in this systematic review. The main findings drawn from these studies are also presented below, distributed in different sections.

Characteristics of reviewed studies.

| Author/s (Year) | Sample ( , Characteristics) | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albury & Byron (2016) [ ] | Same-sex attracted Australian men and women, aged between 18 and 29 | Focus groups interviews | Mobile and apps contributed to participants’ perceptions of safety and risk when flirting or meeting with new sexual partners. Users strategically engaged with the security features of apps to block unwanted approaches and to manage privacy concerns when interacting with others. |

| Alexopoulos et al. (2020) [ ] | 395 participants, recruited through a U.S.-based university and Amazon Mechanical Turk, both sexes ( 26.7, = 8.32) | Online survey | People´s perceived success on a dating app was positively associated with their intention to commit infidelity through perceived amount of available partners. |

| Badal et al. (2018) [ ] | 3105 males identified as gay or bisexual, aged 18–64 ( = 32.35, = 9.58), residents in the United States or Puerto Rico | Web-based survey | More than half (55.7%) of participants were frequent users of dating websites and apps. Two third (66.7%) of users had casual partner only in the prior 12 months and reported a high average number of casual sex partners in the previous 12 months compared to never users. The most frequently used dating apps was Grindr (60.2%). |

| Boonchutima & Kongchan (2017) [ ] | 350 Thai men who have sex with men | Online survey | 73% of participants were dating app users, to find potential partners as well as for inviting others into illicit drug practice. Persuasion through dating apps influenced people toward accepting the substance use invitation, with a 77% invitation success rate. Substance use was linked with unprotected sex. |

| Boonchutima et al. (2016) [ ] | 286 gay dating app users in Thailand | Online survey | There are positive associations between the degree of app usage and the amount of information being disclosed. Moreover, the frequency of usage and the disclosure of personal information were associated with a higher rate of unprotected sex. |

| Botnen et al. (2018) [ ] | 641 Norwegian university students, both sexes, aged between 19 and 29 ( = 21.4, = 1.6) | Offline questionnaire | Nearly half of the participants reported former or current dating app use. 20% was current users. Dating app users tend to report being less restricted in their sociosexuality than participants who have never used apps. This effect was equally strong for men and women. |

| Breslow et al. (2020) [ ] | 230 sexual minority men, U.S.-located | Online survey | The number of apps used was positively related with objectification, internalization, and body surveillance, and negatively related with body satisfaction and self-esteem. |

| Castro et al. (2020) [ ] | 1705 students from a Spanish university, both sexes, aged between 18 and 26 ( = 20.60, = 2.09) | Online survey | Men, older youths, members of sexual minorities, and people without partner were more likely to be dating app users. In addition, some traits of the Big Five (openness to experience) allowed prediction of the current use of dating apps. The dark personality showed no predictive ability. |

| Chan (2017) [ ] | 401 men who have sex with men, U.S.-located, ages ranged from 18 to 44 years ( = 23.45, = 4.09) | Online survey | There was a significant relationship between sex-seeking and the number of casual sex partners, mediated by the intensity of apps use. Furthermore, gay identity confusion and outness to the world moderated these indirect effects. |

| Chan (2017) [ ] | 257 U.S. citizens, both sexes, aged between 18 and 34 ( = 27.1, = 4.35), heterosexuals. | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | Regarding using dating apps to seek romance, people´s attitude and perceived norms were predictive of such intent. Sensation-seeking and smartphone use had a direct relationship with intent. Regarding using dating apps for seeking sex, people´s attitude and self-efficacy were predictive of such intent. |

| Chan (2018) [ ] | (1) 7 Asian-American users of gay male dating apps, aged between 26 and 30; (2) 245 U.S. male dating app users, aged between 19 and 68. | (1) semi-structured interviews; (2) online survey | Users reported ambivalence in establishing relationships, which brought forth the ambiguity of relationships, dominance of profiles, and over-abundance of connections on these apps. |

| Chan (2018) [ ] | 19 female dating app users in China, aged between 21 and 38 | Semi-structured interviews | Female dating app users offered multiple interpretations of why they use dating apps (e.g., sexual experience, looking for a relationship, entertainment). They also face several challenges in using dating apps (e.g., resisting social stigma, assessing men´s purposes, undesirable sexual solicitations). |

| Chan (2019) [ ] | 125 male heterosexual active users of dating apps (Momo) in urban cities in China, aged between 18 and 47 ( = 28.94, = 5.96) | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | The endorsement of masculinity had an indirect positive relationship with the number of sex partners mediated by the sex motive. At the same time, this had a direct but negative association with the number of sex partners. These paradoxical associations were explained by different patterns across the individual dimension of masculinity ideology (e.g., importance of sex, avoidance of femininity). |

| Chin et al. (2019) [ ] | 183 North-American adults, both sexes, aged between 18 and 65 ( = 29.97, = 8,50). Recruited via Amazon´s Mechanical Turk. | Online survey | People with a more anxious attachment orientation were more likely to report using dating apps than people lower in anxiety attachment. People with a more avoidance attachment orientation were less like to report using dating apps than people lower in avoidant attachment. The most common reason people reported for using apps was to meet others, and the most common reason people reported for not using apps was difficulty trusting people online. |

| Choi et al. (2016) [ ] | 666 university students from Hong Kong, both sexes ( = 20.03, = 1.52) | Self-administered survey (not online) | Users of dating apps were more likely to have unprotected sex with a casual sex partner the last time they engaged in sexual intercourse. Using dating apps for more than 12 months was associated with having a casual sex partner in the last episode of sexual intercourse, as well as having unprotected sex with that casual partner. |

| Choi et al. (2016) [ ] | 666 university students from Hong Kong, both sexes ( = 20.03, = 1.52) | Self-administered survey (not online) | Users of dating apps and current drinkers were less likely to have consistent condom use. Users of dating apps, bisexual/homosexual subjects, and female subjects were more likely not to have used condoms the last time they had sexual intercourse. |

| Choi et al. (2017) [ ] | 666 university students from Hong Kong, both sexes ( = 20.03, = 1.52) | Self-administered survey (not online) | The use of dating apps for more than one year was found to be associated with recreational drug use in conjunction with sexual activities. Other risk factors of recreational drug use in conjunction with sexual activities included being bisexual/homosexual, male, a smoker, and having one´s first sexual intercourse before 16 years. The use of dating apps was not a risk factor for alcohol consumption in conjunction with social activities. |

| Choi et al. (2017) [ ] | 666 university students from Hong Kong, both sexes ( = 20.03, = 1.52) | Self-administered survey (not online) | Users of dating apps were more likely to have been sexually abused in the previous year than non-users. Using dating apps was also a risk factor for lifetime sexual abuse. |

| Coduto et al. (2020) [ ] | 269 undergraduate students, both sexes, aged between 18 and 24 ( = 20.85, = 2.45) | Online survey | The data provided support for moderated serial mediation. This type of mediation predicted by the social skills model was significant only among those high in loneliness, with positive association between preference for online social interaction and compulsive use being significant among those with high in loneliness. |

| Duncan & March (2019) [ ] | 587 Tinder users, both sexes ( = 23.75, = 6.05) | Online survey | They created and validated the Antisocial Uses of Tinder Scale. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses revealed three forms of antisocial behavior (general, esteem, and sexual). Regression analyses showed the predictive utility of gender and the dark traits across antisocial behaviors. |

| Ferris & Duguay (2020) [ ] | 27 women seeking women (WSW) from Australia, Canada, and the UK, aged between 19 and 35. | Semi-structured interviews | Participants perceived that they were entering a space conducive to finding women seeking women. However, men, couples, and heterosexual women permeated this space, heightening the need for participants to signal non-heterosexual identity. |

| Filice et al. (2019) [ ] | 13 men who have sex with men, aged between 18 and 65 ( = 29). | Semi-structured interviews | Grindr affects user body image through three primary mechanisms: weight stigma, sexual objectification and social comparison. Moreover, participants identified several protective factors and coping strategies. |

| Gatter & Hodkinson (2016) [ ] | 75 participants, both sexes, aged between 20 and 69, divided in three groups (Tinder users, online dating agency users, and non-users). | Online survey | No differences were found in motivations, suggesting that people may use both online dating agencies and Tinder for similar reasons. Tinder users were younger than online dating agency users, which accounted for observed group differences in sexual permissiveness. There were no differences in self-esteem or sociability between the groups. Men were more likely than women to use both types of dating and scored higher in sexual permissiveness. |

| Goedel et al. (2017) [ ] | 92 men who have sex with men, Grindr users, aged between 18 and 70. | Online survey | Obese participants scored significantly higher on measures of body dissatisfaction and lower on measures of sexual sensation seeking. Decreased propensities to seek sexual-sensation were associated with fewer sexual partners. |

| Green et al. (2018) [ ] | 953 university students, both sexes, aged between 18 and 24 ( = 20.76, = 1.81) | Online survey | Tinder users may: (1) perceive partners with whom they share “common connections” as familiar or “safe”, which may give users a false sense of security about the sexual health risks; or (2) be hesitant to discuss sexual health matters with partners who are within their sexual network due to fear of potential gossip. Both lines of thought may reduce safer sex behaviors. |

| Griffin et al. (2018) [ ] | 409 U.S. university students, heterosexuals, both sexes ( = 19.7, = 7.2) | Online survey | 39% of participants had used a dating app, and 60% of them were regular users. Tinder was the most popular dating app. Top reasons for app use were fun and to meet people. Very few users (4%) reported using apps for casual sex encounters, although many users (72% of men and 22% of women) were open to meeting a sexual partner with a dating app. Top concerns included safety and privacy. |

| Hahn et al. (2018) [ ] | Study 1: 64 men who have sex with men dating app users, aged between 18 and 24 ( = 22.66, = 1.38). Study 2: 217 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 21 ( = 20.23, = 0.85). Recruited by Amazon Mechanical Turk (both studies). | Online survey (both studies) | Study 1: those who talked less before meeting in person engaged in more sexual risk behaviors than those who spent more time talking before meeting in person. Study 2: there were no differences in sexual risk behaviors between dating app users and non-users. However, when examining app users by time before meeting, those with a shorter time before meeting were more impulsive and more likely to report sexual risk behaviors. |

| Hart et al. (2016) [ ] | 539 heterosexual attenders of two genito-urinary medicine clinics, both sexes ( = 21–30 years). | Self-administered survey | A quarter of participants use apps to find partners online. This study identified high rates of sexually transmitted infections, condomless use and recreational drug use among app users. |

| Kesten et al. (2019) [ ] | 25 men who have sex with men residents in England aged between 26 and 57 years ( = 30–39). | Semi-structured interviews | Sexual health information delivery through social media and dating apps was considered acceptable. Concerns were expressed that sharing or commenting on social media sexual health information may lead to judgments and discrimination. Dating apps can easily target men who have sex with men. |

| Lauckner et al. (2019) [ ] | 20 sexual minority males living in U.S. non-metropolitan areas, aged between 18 and 60. | Survey and semi-structured interviews | Many participants reported negative experiences while using dating apps. Specifically, they discussed instances of deception or “catfishing”, discrimination, racism, harassment, and sexual coercion. |

| LeFebvre (2018) [ ] | 395 participants recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk, both sexes, aged between 18 and 34 ( = 26.41, = 4.17) | Online survey | The prevalent view that Tinder is a sex or hookup app remains salient among users; although, many users utilize Tinder for creating other interpersonal communication connections and relationships, both romantic and platonic. Initially, Tinder users gather information to identify their preferences. |

| Licoppe (2020) [ ] | Grindr study: 23 male users of Grindr in Paris. Tinder study: 40 male and female users of Tinder in France. | In-depth interviews | Grindr and Tinder users take almost opposite conversational stances regarding the organization of casual hookups as sexual, one-off encounters with strangers. While many gay Grindr users have to chat to organize quick sexual connections, many heterosexual Tinder users are looking to achieve topically-rich chat conversations. |

| Luo et al. (2019) [ ] | 9280 men who have sex with men dating app users in China ( = 31–40 years). | Online survey | Results indicated that frequent app use was associated with lower odds of condomless anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in China. |

| Lutz & Ranzini (2017) [ ] | 497 U.S.-based participants, both sexes ( = 30.9, = 8.2), recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk. | Online survey | Tinder users were more concerned about institutional privacy than social privacy. Moreover, different motivations for using Tinder (hooking up, relationship, friendship, travel, self-validation, entertainment) affect social privacy concerns more strongly than institutional concerns. Finally, loneliness significantly increases users´ social and institutional privacy concerns. |

| Lyons et al. (2020) [ ] | 216 current or former Tinder users, from UK, USA and Canada, both sexes, aged between 18 and 56 ( = 22.87, = 7.09). | Online survey | Using Tinder for acquiring sexual experience was related to being male and being high in psychopathy. Psychopathy was positively correlated with using Tinder to distract oneself from other tasks. Higher Machiavellianism and being female were related to peer pressure as a Tinder use motivation. Using Tinder for acquiring social or flirting skills had a negative relationship with narcissism, and a positive relationship with Machiavellianism. Finally, Machiavellianism was also a significant, positive predictor of Tinder use for social approval and to pass the time. |

| Macapagal et al. (2019) [ ] | 219 adolescent members of sexual and gender minorities assigned male at birth, U.S.-located, aged between 15 and 17 ( = 16.30, = 0.74). | Online survey | Most participants (70.3%) used apps for sexual minority men, 14.6% used social media/other apps to meet partners, and 15.1% used neither. Nearly 60% of adolescents who used any type of app reported having met people from the apps in person. Dating apps and social media users were more like to report condomless receptive anal sex. |

| Macapagal et al. (2018) [ ] | 200 adolescent men who have sex with men, aged between 14 and 17 ( = 16.64, = 0.86). | Online survey | 52.5% of participants reported using gay-specific apps to meet partner for sex. Of these, most participants reported having oral (75.7%) and anal sex (62.1%) with those partners. Of those who reported having anal sex, only 25% always used condoms. |

| March et al. (2017) [ ] | 357 Australian adults, both sexes, aged between 18 and 60 ( = 22.50, = 6.55). | Online survey | Traits of psychopathy, sadism, and dysfunctional impulsivity were significantly associated with trolling behaviors. Subsequent moderation analyses revealed that dysfunctional impulsivity predicts perpetration of trolling, but only if the individual has medium or high levels of psychopathy. |

| Miller (2019) [ ] | 322 North-American men who have sex with men apps users, aged between 18 and 71 ( = 30.6). | Online survey | Results indicated that the majority of men presented their face in their profile photo and that nearly one in five presented their unclothed torso. Face-disclosure was connected to higher levels of app usage, longer-term app usage, and levels of outness. The use of shirtless photos was related to age, a higher drive for muscularity, and more self-perceived masculinity. |

| Miller & Behm-Morawitz (2016) [ ] | 143 men who have sex with men app users, aged between 18 and 50 ( = 27.41, = 7.60). | Online experiment | Results indicated that the use of femmephobic language in dating profiles affects a potential partner´s perceived intelligence, sexual confidence, and dateability, as well as one´s desire to meet potential partners offline for friendship or romantic purposes. |

| Numer et al. (2019) [ ] | 16 gay/bisexual Canada-located males, Grindr users, aged between 20 and 50. | Semi-structured interviews | Three threads of disclosure emerged: language and images, filtering, and trust. These threads of disclosure provide insights into how the sexual beliefs, values, and practices of gay and bisexual men who have sex with men are shaped on dating apps. |

| Orosz et al. (2018) [ ] | Study 1: 414 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 43 ( = 22.71, = 3.56). Study 2: 346 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 51 ( = 22.02, = 3.41). Study 3: 298 participants, both sexes, aged between 19 and 65 ( = 25.09, = 5.82) | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | Study 1: a 16-item first-order factor structure was identified with four motivational factors (sex, love, self-esteem enhancement, boredom). Study 2: problematic Tinder use was mainly related to using Tinder for self-esteem enhancement. The Big Five personality factors were only weakly related to the four motivations and to problematic Tinder use. Study 3: showed that instead of global self-esteem, relatedness-need frustration was the strongest predictor of self-esteem enhancement Tinder use motivation that, in turn, was the strongest predictor of problematic Tinder use. |

| Orosz et al. (2016) [ ] | 430 Hungarian participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 51 ( = 22.53, = 3.74). | Online survey | They created and validated the Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS). Both the 12- and the 6-item versions were tested. The 6-item unidimensional structure has appropriate reliability and factor structure. No salient demographic-related differences were found. |

| Parisi & Comunello (2020) [ ] | 20 Italian dating app users, both sexes, aged between 22 and 65 ( = 38). | Focus groups | Participants appreciated the role of mobile dating apps in reinforcing their relational homophile (their tendency to like people that are “similar” to them) whilst, at the same time, mainly using these apps for increasing the diversity of their intimate interactions in terms of extending their networks. |

| Queiroz et al. (2019) [ ] | 412 men who have sex with men dating app users, located in Brazil, with ages over 50 years. | Online survey | Factors associated with a higher chance of having HIV were: sexual relations with an HIV-infected partner, chemsex and, above all, having an HIV-infected partner. The belief that apps increase protection against STI, and not being familiar with post-exposure prophylaxis, were associated with decreased chances of having HIV. |

| Ranzini & Lutz (2017) [ ] | 497 U.S.-based participants, both sexes ( = 30.9, = 8.2), recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | Self-esteem was the most important psychological predictor, fostering real self-presentation but decreasing deceptive self-presentation. The motives of use (hooking up/sex, friendship, relationship, traveling, self-validation, entertainment) also affect self-presentation, and were related to demographic characteristics and psychological antecedents. |

| Rochat et al. (2019) [ ] | 1159 heterosexual Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 74 ( = 30.02, = 9.19). | Online survey | Four reliable clusters were identified: two with low levels of problematic use (“regulated” and “regulated with low sexual desire”), one with and intermediate level of problematic use (“unregulated-avoidant”), and one with a high-level of problematic use (“unregulated-avoidant”). The clusters differed on gender, marital status, depressive mood, and use patterns. |

| Rodgers et al. (2019) [ ] | 170 college students, both sexes, aged between 18 and 32 ( = 22.2) | Online survey | Among males, frequent checking of dating apps was positively correlated with body shame and negatively with beliefs regarding weight/shape controllability. Media internalization was negatively correlated with experiencing negative feelings when using dating apps, and positively with positive feelings. Few associations emerged among females. |

| Sawyer et al. (2018) [ ] | 509 students from an U.S. university, both sexes, aged between 18 and 25 ( = 20.07, = 1.37). | Online survey | 39.5% of the participants reported using dating apps. Individuals who used dating apps had higher rates of sexual risk behavior in the last three months, including sex after using drugs or alcohol, unprotected sex (anal or vaginal), and more lifetime sexual partners. |

| Schreus et al. (2020) [ ] | 286 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 30 ( = 24.60, = 3.41). | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | More frequent dating app use was positively related to norms and beliefs about peers´ sexting behaviors with unknown dating app matches (descriptive norms), norms beliefs about peers´ approval of sexting with matches (subjective norms), and negatively related to perceptions of danger sexting with matches (risk attitudes). |

| Sevi et al. (2018) [ ] | 163 U.S.-located Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 53 ( = 27.9, = 6.5), recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk. | Online survey | Sexual disgust sensitivity and sociosexuality were predictors of motivation to use Tinder for casual sex. The participants with higher sexual disgust sensitivity reported a lower motivation while the participants with higher sociosexuality reported a higher motivation for casual sex in their Tinder usage. While this model explained the motivation for men, a different model explained women´s motivation. Sociosexuality mediated the relationship between sexual disgust sensitivity and the motivation to use Tinder for casual sex for women Tinder users. |

| Shapiro et al. (2017) [ ] | 415 students from a Canadian university, both sexes, aged between 18 and 26 ( = 20.73, = 1.73). | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | Greater likelihood of using Tinder was associated with a higher level of education and greater reported need for sex, while decreased likelihood of using Tinder was associated with a higher level of academic achievement, lower sexual permissiveness, living with parents or relatives, and being in a serious relationship. Higher odds of reporting nonconsexual sex and having five or more previous sexual partners users were found in Tinder users. Tinder use was not associated with condom use. |

| Solis & Wong (2019) [ ] | 433 Chinese dating app users, both sexes, aged between 11 and 50 ( = 30). | Online survey | Sexuality was the only predictor of the reasons that people use dating apps to meet people offline for dates and casual sex. Among the perceived risks of mobile dating, only the fear of self-exposure to friends, professional networks, and the community significantly explained why users would not meet people offline for casual sex. |

| Srivastava et al. (2019) [ ] | 253 homeless youth located in Los Angeles, both sexes, aged between 14 and 24 ( = 21.9, = 2.16). | Computer-administered survey | Sexual minority (43.6%) and gender minority (12.1%) youth reported elevated rates of exchange sex compared to cisgender heterosexual youth. 23% of youth who engaged in survival or exchange sex used dating apps or websites to find partners. Exchange sex and survival sex were associated with having recent HIV-positive sex partners. |

| Strubel & Petrie (2017) [ ] | 1,147 U.S.-located single participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 34. | Online survey | Tinder users, regardless of gender, reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction with face and body and higher levels of internalization, appearance comparisons, and body shame and surveillance than non-users. For self-esteem, male Tinder users scored significantly lower than the other groups. |

| Strugo & Muise (2019) [ ] | Study 1: 334 Tinder users, both sexes. Study 2: 441 single Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 59 ( = 27.7, = 6.6), recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk. | Online survey | Study 1: higher approach goals for using Tinder, such as to develop intimate relationships, were associated with more positive beliefs about people on Tinder, and, in turn, associated with reporting greater perceived dating success. In contrast, people with higher avoidance goals, reported feeling more anxious when using Tinder. Study 2: previous results were not accounted for by attractiveness of the user and were consistent between men and women, but differed based on the age of user. |

| Sumter & Vandenbosch (2019) [ ] | 541 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 30 ( = 23.71, = 3.29). | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | Nearly half of the sample used dating apps regularly, with Tinder being the most popular. Non-users were more likely to be heterosexual, high in dating anxiety, and low in sexual permissiveness than dating app users. Among app users, dating app motivations (relational, interpersonal, entertainment), were meaningfully related to identity features. |

| Sumter et al. (2017) [ ] | 266 Dutch young, both sexes, aged between 18 and 30 ( = 23.74, = 2.56). | Online survey (via Qualtrics) | They found six motivations to use Tinder (love, casual sex, ease of communication, self-worth validation, thrill of excitement, trendiness). The Love motivation appeared to be a stronger motivation to use Tinder than the Casual sex motivation. Men were more likely to report a Casual sex motivation for using Tinder than women. With regard to age, the motivations Love, Casual Sex, and Ease of communication were positively related to age. |

| Tang (2017) [ ] | 12 Chinese lesbian and bisexual women, aged 35 and above. | In-depth interviews | Although social media presents ample opportunities for love and intimacy, the prevailing conservative values and cultural norms surrounding dating and relationships in Hong Kong are often reinforced and played out in their choice of romantic engagement. |

| Timmermans & Courtois (2018) [ ] | 1038 Belgian Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 29 ( = 21.80, = 2.35). | Online survey | User´s swiping quantity does not guarantee a higher number of Tinder matches. Women have generally more matches than men and men usually have to start a conversation on Tinder. Less than half of the participants reported having had an offline meeting with another Tinder user. More than one third of these offline encounters led to casual sex, and more than a quarter resulted in a committed relationship. |

| Timmermans & De Caluwé (2017) [ ] | Study 1: 18 students from an U.S. university, between 18 and 24 years. Study 2: 1728 Belgian Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 67 ( = 22.66, = 4.28). Study 3: 485 Belgian Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 19 and 49 ( = 26.71, = 5.32). Study 4: 1031 Belgian Tinder users, both sexes, aged between 18 and 69 ( = 26.93, = 7.93). | Study 1: semi-structured interviews. Studies 2–4: online survey | The Tinder Motives Scale (TMS) consists of 58 items and showed a replicable factor structure with 13 reliable motives (social approval, relationship seeking, sexual experience, flirting/social skills, travelling, ex, belongingness, peer pressure, socializing, sexual orientation, pass time/entertainment, distraction, curiosity). The TMS is a valid and reliable scale to assess Tinder use motivations. |

| Timmermans & De Caluwé (2017) [ ] | 502 single Belgian participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 29 ( = 23.11, = 2.83). | Online survey | Single Tinder users were more extraverted and open to new experiences than single non-users, whereas single non-users tended to be more conscientious than single users. Additionally, the findings provide insights into how individual differences (sociodemographic and personality variables) in singles can account for Tinder motives. |

| Timmermans et al. (2018) [ ] | Sample 1: 1616 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 74 ( = 28.90, = 10.32). Sample 2: 1795 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 58 ( = 22.89, = 4.57). | Online survey | Non-single Tinder users differed significantly on nine Tinder motives from single Tinder users. Non-single users generally reported a higher number of romantic relationships and casual sex relationships with other Tinder users compared to single Tinder users. Non-single Tinder users scored significantly lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness, and significantly higher on neuroticism and psychopathy compared to non-users in a committed relationship. |

| Tran et al. (2019) [ ] | 1726 U.S.-located participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 65, recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk | Online survey | Dating app users had substantially elevated odds of unhealthy weight control behaviors compared with non-users. These findings were supported by results of additional gender-stratified multivariate logistic regression analyses among women and men. |

| Ward (2017) [ ] | 21 Dutch participants, recruited in Tinder, both sexes, aged between 19 and 52 years. | Semi-structured interviews | Users´ motivations for using Tinder ranged from entertainment to ego-boost to relationship seeking, and these motivations sometimes change over time. Profile photos are selected in an attempt to present an ideal yet authentic self. Tinder users “swipe” not only in search of people they like, but also for clues as to how to present themselves in order to attract others like them. |

| Weiser et al. (2018) [ ] | 550 students from an U.S.- university, both sexes, aged between 18 and 33 ( = 20.86, = 1.82). | Online survey | Participants indicated that most knew somebody who had used Tinder to meet extradyadic partners, and several participants reported that their own infidelity had been facilitated by Tinder. Sociosexuality and intentions to engage in infidelity were associated with having used Tinder to engage in infidelity. |

| Wu (2019) [ ] | 262 participants, both sexes, aged between 18 and 30 ( = 23.14, = 2.11). | Online survey | Tinder users reported higher scores for sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity than non-users. No differences were found regarding risky sexual behavior, except that Tinder users use condoms more frequently than non-users. |

| Wu & Ward (2019) [ ] | 21 Chinese urban dating app users, aged between 20 and 31 ( = 25.3). | Semi-structured interviews | Casual sex is perceived as a form of social connection with the potential to foster a relationship. |

| Yeo & Fung (2018) [ ] | 74 gay mobile dating app users, aged between 18 and 26 years | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | The accelerated tempo of interactions facilitated by perpetual connectivity, mutual proximity awareness, and instant messaging was seen to entail instantaneous and ephemeral relationships. The interface design, which foregrounds profile photos and backgrounds textual self-descriptions, was perceived to structure the sequence of browsing and screening in favor of physical appearance and users seeking casual hook-ups. |

| Zervoulis et al. (2019) [ ] | 191 men who have sex with men living in the United Kingdom aged between 18 and 72 ( = 36.51, = 10.17). | Online survey | High users of dating apps reported a lower sense of community, higher levels of loneliness, and lower levels of satisfaction with life. There was some evidence that those men who have sex with men who use dating apps mainly for sexual encounters reported higher levels of self-esteem and of satisfaction with life compared to those who used dating apps mainly for other reasons. |

3.1. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

First, the characteristics of the 70 articles included in the systematic review were analyzed. An annual increase in production can be seen, with 2019 being the most productive year, with 31.4% ( n = 22) of included articles. More articles (11) were published in the first three months of 2020 than in 2016. It is curious to note, on the other hand, how, in the titles of the articles, some similar formulas were repeated, even the same articles (e.g., Love me Tinder), playing with the swipe characteristic of this type of application (e.g., Swiping more, Swiping right, Swiping me).

As for the methodology used, the first aspect to note is that all the localized studies were cross-sectional and there were no longitudinal ones. As mentioned above, 80% ( n = 55) of the studies were quantitative, especially through online survey ( n = 49; 70%). 15.7% ( n = 11) used a qualitative methodology, either through semi-structured interviews or focus groups. And 5.7% ( n = 4) used a mixed methodology, both through surveys and interviews. It is worth noting the increasing use of tools such as Amazon Mechanical Turk ( n = 9, 12.9%) or Qualtrics ( n = 8, 11.4%) for the selection of participants and data collection.

The studies included in the review were conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts. More than one in five investigations was conducted in the United States (22.8%, n = 16), to which the two studies carried out in Canada can be added. Concerning other contexts, 20% ( n = 14) of the included studies was carried out in different European countries (e.g., Belgium, The Netherlands, UK, Spain), whereas 15.7% ( n = 11) was carried out in China, and 8.6% ( n = 6) in other countries (e.g., Thailand, Australia). However, 21.4% ( n = 15) of the investigations did not specify the context they were studying.

Finally, 57.1% ( n = 40) of the studies included in the systematic review asked about dating apps use, without specifying which one. The results of these studies showed that Tinder was the most used dating app among heterosexual people and Grindr among sexual minorities. Furthermore, 35% ( n = 25) of the studies included in the review focused on the use of Tinder, while 5.7% ( n = 4) focused on Grindr.

3.2. Characteristics of Dating App Users

It is difficult to find studies that offer an overall user profile of dating apps, as many of them have focused on specific populations or groups. However, based on the information collected in the studies included in this review, some features of the users of these applications may be highlighted.

Gender. Traditionally, it has been claimed that men use dating apps more than women and that they engage in more casual sex relationships through apps [ 3 ]. In fact, some authors, such as Weiser et al. [ 75 ], collected data that indicated that 60% of the users of these applications were male and 40% were female. Some current studies endorse that being male predicts the use of dating apps [ 23 ], but research has also been published in recent years that has shown no differences in the proportion of male and female users [ 59 , 68 ].

To explain these similar prevalence rates, some authors, such as Chan [ 27 ], have proposed a feminist perspective, stating that women use dating apps to gain greater control over their relationships and sexuality, thus countering structural gender inequality. On the other hand, other authors have referred to the perpetuation of traditional masculinity and femmephobic language in these applications [ 28 , 53 ].

Age. Specific studies have been conducted on people of different ages: adolescents [ 49 ], young people (e.g., [ 21 , 23 , 71 ]), and middle-aged and older people [ 58 ]. The most studied group has been young people between 18 and 30 years old, mainly university students, and some authors have concluded that the age subgroup with a higher prevalence of use of dating apps is between 24 and 30 years of age [ 44 , 59 ].

Sexual orientation. This is a fundamental variable in research on dating apps. In recent years, especially after the success of Tinder, the use of these applications by heterosexuals, both men and women, has increased, which has affected the increase of research on this group [ 3 , 59 ]. However, the most studied group with the highest prevalence rates of dating apps use is that of men from sexual minorities [ 18 , 40 ]. There is considerable literature on this collective, both among adolescents [ 49 ], young people [ 18 ], and older people [ 58 ], in different geographical contexts and both in urban and rural areas [ 24 , 36 , 43 , 79 ]. Moreover, being a member of a sexual minority, especially among men, seems to be a good predictor of the use of dating apps [ 23 ].

For these people, being able to communicate online can be particularly valuable, especially for those who may have trouble expressing their sexual orientation and/or finding a partner [ 3 , 80 ]. There is much less research on non-heterosexual women and this focuses precisely on their need to reaffirm their own identity and discourse, against the traditional values of hetero-patriate societies [ 35 , 69 ].

Relationship status. It has traditionally been argued that the prevalence of the use of dating apps was much higher among singles than among those with a partner [ 72 ]. This remains the case, as some studies have shown that being single was the most powerful sociodemographic predictor of using these applications [ 23 ]. However, several investigations have concluded that there is a remarkable percentage of users, between 10 and 29%, who have a partner [ 4 , 17 , 72 ]. From what has been studied, usually aimed at evaluating infidelity [ 17 , 75 ], the reasons for using Tinder are very different depending on the relational state, and the users of this app who had a partner had had more sexual and romantic partners than the singles who used it [ 72 ].

Other sociodemographic variables. Some studies, such as the one of Shapiro et al. [ 64 ], have found a direct relationship between the level of education and the use of dating apps. However, most studies that contemplated this variable have focused on university students (see, for example [ 21 , 23 , 31 , 38 ]), so there may be a bias in the interpretation of their results. The findings of Shapiro et al. [ 64 ] presented a paradox: while they found a direct link between Tinder use and educational level, they also found that those who did not use any app achieved better grades. Another striking result about the educational level is that of the study of Neyt et al. [ 9 ] about their users’ characteristics and those that are sought in potential partners through the apps. These authors found a heterogeneous effect of educational level by gender: whereas women preferred a potential male partner with a high educational level, this hypothesis was not refuted in men, who preferred female partners with lower educational levels.

Other variables evaluated in the literature on dating apps are place of residence or income level. As for the former, app users tend to live in urban contexts, so studies are usually performed in large cities (e.g., [ 11 , 28 , 45 ]), although it is true that in recent years studies are beginning to be seen in rural contexts to know the reality of the people who live there [ 43 ]. It has also been shown that dating app users have a higher income level than non-users, although this can be understood as a feature associated with young people with high educational levels. However, it seems that the use of these applications is present in all social layers, as it has been documented even among homeless youth in the United States [ 66 ].

Personality and other psychosocial variables. The literature that relates the use of dating apps to different psychosocial variables is increasingly extensive and diverse. The most evaluated variable concerning the use of these applications is self-esteem, although the results are inconclusive. It seems established that self-esteem is the most important psychological predictor of using dating apps [ 6 , 8 , 59 ]. But some authors, such as Orosz et al. [ 55 ], warn that the meaning of that relationship is unclear: apps can function both as a resource for and a booster of self-esteem (e.g., having a lot of matches) or to decrease it (e.g., lack of matches, ignorance of usage patterns).

The relationship between dating app use and attachment has also been studied. Chin et al. [ 29 ] concluded that people with a more anxious attachment orientation and those with a less avoidant orientation were more likely to use these apps.

Sociosexuality is another important variable concerning the use of dating apps. It has been found that users of these applications tended to have a less restrictive sociosexuality, especially those who used them to have casual sex [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 21 ].

Finally, the most studied approach in this field is the one that relates the use of dating apps with certain personality traits, both from the Big Five and from the dark personality model. As for the Big Five model, Castro et al. [ 23 ] found that the only trait that allowed the prediction of the current use of these applications was open-mindedness. Other studies looked at the use of apps, these personality traits, and relational status. Thus, Timmermans and De Caluwé [ 71 ] found that single users of Tinder were more outgoing and open to new experiences than non-user singles, who scored higher in conscientiousness. For their part, Timmermans et al. [ 72 ] concluded that Tinder users who had a partner scored lower in agreeableness and conscientiousness and higher in neuroticism than people with partners who did not use Tinder.

The dark personality, on the other hand, has been used to predict the different reasons for using dating apps [ 48 ], as well as certain antisocial behaviors in Tinder [ 6 , 51 ]. As for the differences in dark personality traits between users and non-users of dating apps, the results are inconclusive. A study was localized that highlighted the relevance of psychopathy [ 3 ] whereas another study found no predictive power as a global indicator of dark personality [ 23 ].

3.3. Characteristics of Dating App Use

It is very difficult to know not only the actual number of users of dating apps in any country in the world but also the prevalence of use. This varies depending on the collectives studied and the sampling techniques used. Given this caveat, the results of some studies do allow an idea of the proportion of people using these apps. It has been found to vary between the 12.7% found by Castro et al. [ 23 ] and the 60% found by LeFebvre [ 44 ]. Most common, however, is to find a participant prevalence of between 40–50% [ 3 , 4 , 39 , 62 , 64 ], being slightly higher among men from sexual minorities [ 18 , 50 ].

The study of Botnen et al. [ 21 ] among Norwegian university students concluded that about half of the participants appeared to be a user of dating apps, past or present. But only one-fifth were current users, a result similar to those found by Castro et al. [ 23 ] among Spanish university students. The most widely used, and therefore the most examined, apps in the studies are Tinder and Grindr. The first is the most popular among heterosexuals, and the second among men of sexual minorities [ 3 , 18 , 36 , 70 ].

Findings from existing research on the characteristics of the use of dating apps can be divided among those referring to before (e.g., profiling), during (e.g., use), and after (e.g., offline behavior with other app users). Regarding before , the studies focus on users’ profile-building and self-presentation more among men of sexual minorities [ 52 , 77 ]. Ward [ 74 ] highlighted the importance of the process of choosing the profile picture in applications that are based on physical appearance. Like Ranzini and Lutz [ 59 ], Ward [ 74 ] mentions the differences between the “real self” and the “ideal self” created in dating apps, where one should try to maintain a balance between one and the other. Self-esteem plays a fundamental role in this process, as it has been shown that higher self-esteem encourages real self-presentation [ 59 ].

Most of the studies that analyze the use of dating apps focus on during , i.e. on how applications are used. As for the frequency of use and the connection time, Chin et al. [ 29 ] found that Tinder users opened the app up to 11 times a day, investing up to 90 minutes per day. Strubel and Petrie [ 67 ] found that 23% of Tinder users opened the app two to three times a day, and 14% did so once a day. Meanwhile, Sumter and Vandenbosch [ 3 ] concluded that 23% of the users opened Tinder daily.

It seems that the frequency and intensity of use, in addition to the way users behave on dating apps, vary depending on sexual orientation and sex. Members of sexual minorities, especially men, use these applications more times per day and for longer times [ 18 ]. As for sex, different patterns of behavior have been observed both in men and women, as the study of Timmermans and Courtois [ 4 ] shows. Men use apps more often and more intensely, but women use them more selectively and effectively. They accumulate more matches than men and do so much faster, allowing them to choose and have a greater sense of control. Therefore, it is concluded that the number of swipes and likes of app users does not guarantee a high number of matches in Tinder [ 4 ].