The Underground Railroad

Colson whitehead, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Colson Whitehead's The Underground Railroad . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

The Underground Railroad: Introduction

The underground railroad: plot summary, the underground railroad: detailed summary & analysis, the underground railroad: themes, the underground railroad: quotes, the underground railroad: characters, the underground railroad: symbols, the underground railroad: theme wheel, brief biography of colson whitehead.

Historical Context of The Underground Railroad

Other books related to the underground railroad.

- Full Title: The Underground Railroad

- When Written: 2011-2016

- Where Written: New York, USA

- When Published: 2016

- Literary Period: 21st century African-American historical fiction

- Genre: Neo-slave narrative

- Setting: Several states in America in the year 1850, including Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Indiana

- Climax: When Elijah Lander delivers his speech and it is interrupted by a white gang who destroy Valentine farm

- Antagonist: Arnold Ridgeway

- Point of View: Third-person narrator

Extra Credit for The Underground Railroad

Coming to the small screen. In March 2017 Amazon announced the production of a mini-series based on The Underground Railroad , directed by Oscar-winning director Barry Jenkins.

Real pieces of history. The first four runaway slave ads featured in the novel are taken word-for-word from real 19th century newspapers. The only one that Whitehead wrote himself is the last one, Cora’s.

Home — Essay Samples — History — Abolitionism — The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad

- Categories: Abolitionism African American

About this sample

Words: 487 |

Published: Jan 15, 2019

Words: 487 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1592 words

3 pages / 1286 words

2 pages / 961 words

2 pages / 779 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Abolitionism

The abolitionist movement, which emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries, stands as a testament to the power of collective action, moral conviction, and the unwavering pursuit of justice. This transformative social and political [...]

Frederick Douglass, a prominent African American abolitionist and social reformer, is known for his powerful speeches and writings that challenged the institution of slavery in the United States. In his works, Douglass [...]

Introduction to Sojourner Truth's speech "Ain't I a Woman" Mention of its historical context and significance Statement of the essay's purpose: analyzing the effectiveness of rhetorical strategies in the [...]

William Cowper, William Blake, and Anna Barbauld, in their poetry on race and abolitionism, wrote about both the humanity of racialized peoples and the greed and evil of slavery. In post-colonialism, it is important to confront [...]

“If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down, these women together ought to be able to turn it right again.” Sojourner Truth is remembered as perhaps the most influential figure in the [...]

People appear to be scared of things they don’t have knowledge of. Knowledge is what contributes to liberation. So once people understand their fears, they're going to set them free in life. Freedom is the life slaves would like [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Underground Railroad

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 29, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

The Underground Railroad was a network of people, African American as well as white, offering shelter and aid to escaped enslaved people from the South. It developed as a convergence of several different clandestine efforts. The exact dates of its existence are not known, but it operated from the late 18th century to the Civil War, at which point its efforts continued to undermine the Confederacy in a less-secretive fashion.

Quaker Abolitionists

The Quakers are considered the first organized group to actively help escaped enslaved people. George Washington complained in 1786 that Quakers had attempted to “liberate” one of his enslaved workers.

In the early 1800s, Quaker abolitionist Isaac T. Hopper set up a network in Philadelphia that helped enslaved people on the run. At the same time, Quakers in North Carolina established abolitionist groups that laid the groundwork for routes and shelters for escapees.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, established in 1816, was another proactive religious group helping fugitive enslaved people.

What Was the Underground Railroad?

The earliest mention of the Underground Railroad came in 1831 when enslaved man Tice Davids escaped from Kentucky into Ohio and his owner blamed an “underground railroad” for helping Davids to freedom.

In 1839, a Washington newspaper reported an escaped enslaved man named Jim had revealed, under torture, his plan to go north following an “underground railroad to Boston.”

Vigilance Committees—created to protect escaped enslaved people from bounty hunters in New York in 1835 and Philadelphia in 1838—soon expanded their activities to guide enslaved people on the run. By the 1840s, the term Underground Railroad was part of the American vernacular.

How the Underground Railroad Worked

Most of the enslaved people helped by the Underground Railroad escaped border states such as Kentucky, Virginia and Maryland.

In the deep South, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 made capturing escaped enslaved people a lucrative business, and there were fewer hiding places for them. Fugitive enslaved people were typically on their own until they got to certain points farther north.

People known as “conductors” guided the fugitive enslaved people. Hiding places included private homes, churches and schoolhouses. These were called “stations,” “safe houses,” and “depots.” The people operating them were called “stationmasters.”

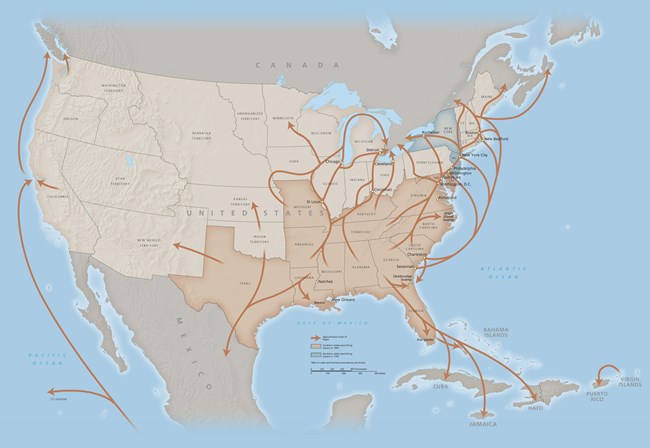

There were many well-used routes stretching west through Ohio to Indiana and Iowa. Others headed north through Pennsylvania and into New England or through Detroit on their way to Canada.

Fugitive Slave Acts

The reason many escapees headed for Canada was the Fugitive Slave Acts . The first act, passed in 1793, allowed local governments to apprehend and extradite escaped enslaved people from within the borders of free states back to their point of origin, and to punish anyone helping the fugitives. Some Northern states tried to combat this with Personal Liberty Laws, which were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1842.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was designed to strengthen the previous law, which was felt by southern states to be inadequately enforced. This update created harsher penalties and set up a system of commissioners that promoted favoritism towards owners of enslaved people and led to some formerly enslaved people being recaptured. For an escaped person, the northern states were still considered a risk.

Meanwhile, Canada offered Black people the freedom to live where they wanted, sit on juries, run for public office and more, and efforts at extradition had largely failed. Some Underground Railroad operators based themselves in Canada and worked to help the arriving fugitives settle in.

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman was the most famous conductor for the Underground Railroad.

Born an enslaved woman named Araminta Ross, she took the name Harriet (Tubman was her married name) when, in 1849, she escaped a plantation in Maryland with two of her brothers. They returned a couple of weeks later, but Tubman left again on her own shortly after, making her way to Pennsylvania.

Tubman later returned to the plantation on several occasions to rescue family members and others. On her third trip, she tried to rescue her husband, but he had remarried and refused to leave.

Distraught, Tubman reported a vision of God, after which she joined the Underground Railroad and began guiding other escaped slaves to Maryland. Tubman regularly took groups of escapees to Canada, distrusting the United States to treat them well.

Frederick Douglass

Formerly enslaved person and famed writer Frederick Douglass hid fugitives in his home in Rochester, New York, helping 400 escapees make their way to Canada. Former fugitive Reverend Jermain Loguen, who lived in neighboring Syracuse, helped 1,500 escapees go north.

Robert Purvis, an escaped enslaved person turned Philadelphia merchant, formed the Vigilance Committee there in 1838. Former enslaved person and railroad operator Josiah Henson created the Dawn Institute in 1842 in Ontario to help escapees who made their way to Canada learn needed work skills.

New York City-based escapee Louis Napoleon’s occupation as listed on his death certificate was “Underground R.R. Agent.” He was a key figure guiding fugitives he found at the docks and train stations.

John Parker was a free Black man in Ohio, a foundry owner who took a rowboat across the Ohio River to help fugitives cross. He was also known to make his way into Kentucky and enter plantations to help enslaved people escape.

William Still was a prominent Philadelphia citizen who had been born to fugitive enslaved parents in New Jersey. An associate of Tubman’s, Still also kept a record of his activities in the Underground Railroad and was able to keep it safely hidden until after the Civil War, when he published them, offering one of the clearest accounts of Underground Railroad activity at the time.

Who Ran the Underground Railroad?

Most Underground Railroad operators were ordinary people, farmers and business owners, as well as ministers. Some wealthy people were involved, such as Gerrit Smith, a millionaire who twice ran for president. In 1841, Smith purchased an entire family of enslaved people from Kentucky and set them free.

One of the earliest known people to help fugitive enslaved people was Levi Coffin, a Quaker from North Carolina. He started around 1813 when he was 15 years old.

Coffin said that he learned their hiding places and sought them out to help them move along. Eventually, they began to find their way to him. Coffin later moved to Indiana and then Ohio, and continued to help escaped enslaved people wherever he lived.

Abolitionist John Brown was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, during which time he established the League of Gileadites, devoted to helping fugitive enslaved people get to Canada.

Brown would play many roles in the abolition movement, most famously leading a raid on Harper’s Ferry to create an armed force to make its way into the deep south and free enslaved people by gunpoint. Brown’s men were defeated, and Brown hanged for treason in 1859.

By 1837 Reverend Calvin Fairbank was helping enslaved people escape from Kentucky into Ohio. In 1844 he partnered with Vermont schoolteacher Delia Webster and was arrested for helping an escaped enslaved woman and her child. He was pardoned in 1849, but was arrested again and spent another 12 years in jail.

Charles Torrey was sent to prison for six years in Maryland for helping an enslaved family escape through Virginia. He operated out of Washington, D.C. , and had previously worked as an abolitionist newspaper editor in Albany, New York.

Massachusetts sea captain Jonathan Walker was arrested in 1844 after he was caught with a boatload of escaped enslaved people that he was trying to help get north. Walker was fined and jailed for a year, and branded on his right hand the letters “SS” for Slave Stealer.

John Fairfield of Virginia rejected his slave-holding family to help rescue the left-behind families of enslaved people who made it north. Fairfield’s method was to travel in the south posing as a slave trader. He broke out of jail twice. He died in 1860 in Tennessee during a rebellion .

End of the Line

The Underground Railroad ceased operations about 1863, during the Civil War. In reality, its work moved aboveground as part of the Union effort against the Confederacy.

Harriet Tubman once again played a significant part by leading intelligence operations and fulfilling a command role in Union Army operations to rescue the emancipated enslaved people.

Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad. Fergus Bordewich . Harriet Tubman: The Road To Freedom. Catherine Clinton . Who Really Ran the Underground Railroad? Henry Louis Gates . The Little Known History of the Underground Railroad in New York. Smithsonian Magazine . The Perilous Lure of the Underground Railroad. The New Yorker .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Underground Railroad Colson Whitehead

The Underground Railroad essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

The Underground Railroad Material

- Study Guide

- Lesson Plan

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2362 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11008 literature essays, 2769 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

The Underground Railroad Essays

Underground railroad: the railroad to the north as a metaphor for freedom anonymous 11th grade, the underground railroad.

In the Underground Railroad, author Colson Whitehead uses the metaphorical instrument of the railroad to the North to portray the deep, systematic roots of the struggles that many still face today. While Cora’s story shows us how far we have come...

Rewriting the Past Saayeh Siahmakoun College

In Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, one of her character’s notes that “we believe the one who has the power... So when you study history, you must always ask yourself, ‘Whose story am I missing?’” (Gyasi 239). With this in mind, novels of historical...

Delusion and Reality in The Underground Railroad Tyler Rodgers College

The realms of delusion and reality are typically intrinsically separated, existing as opposites in the spectrum between myth and actuality. In The Underground Railroad however, Colson Whitehead merges fantastical and mythical elements with...

Past and Future Blues: A Comparison of Historical Themes in 'Sonny's Blues' and 'The Underground Railroad' Anonymous 11th Grade

The past is anything but mere history; it sheathes, surrounds, and encompasses us, as humans, as we forge on through life. Similarly, in two eminent American works of fiction - The Underground Railroad, The Cafeteria, and Sonny’s Blues - the past...

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Perilous Lure of the Underground Railroad

By Kathryn Schulz

The crate arrived, via overland express, one spring evening in 1849. Three feet long, two feet wide, and two and a half feet deep, it had been packed the previous morning in Richmond, Virginia, then carried by horse cart to the local office of the Adams Express Company. From there, it was taken to the railroad depot, loaded onto a train, and, on reaching the Potomac, transferred to a steamer, where, despite its label— THIS SIDE UP WITH CARE —it was placed upside down until a tired passenger tipped it over and used it as a seat. After arriving in the nation’s capital, it was loaded onto a wagon, dumped out at the train station, loaded onto a luggage car, sent on to Philadelphia, unloaded onto another wagon, and, finally, delivered to 31 North Fifth Street. The person to whom the box had been shipped, James Miller McKim, was waiting there to receive it. When he opened it, out scrambled a man named Henry Brown: five feet eight inches tall, two hundred pounds, and, as far as anyone knows, the first person in United States history to liberate himself from slavery by, as he later wrote, “getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state.”

McKim, a white abolitionist with the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, had by then been working for the Underground Railroad for more than a decade, and he was awed by the courage and drama of Brown’s escape, and of others like it. In an article he wrote some years later, he predicted that future generations of Americans would come to share his emotions:

Now deemed unworthy of the notice of any, save fanatical abolitionists, these acts of sublime heroism, of lofty self-sacrifice, of patient martyrdom, these beautiful Providences, these hair-breadth escapes and terrible dangers, will yet become the themes of the popular literature of this nation, and will excite the admiration, the reverence and the indignation of the generations yet to come.

It did not take long for McKim’s prediction to come true. The Underground Railroad entered our collective imagination in the eighteen-forties, and it has since been a mainstay of both national history and local lore. But in the past decade or so it has surged into “the popular literature of this nation”—and the popular everything else, too. This year alone has seen the publication of two major Railroad novels, including Oprah’s first book-club selection in more than a year, Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad” (Doubleday). On TV, the WGN America network aired the first season of “Underground,” which follows the fates of a group of slaves, known as the Macon Seven, who flee a Georgia plantation.

Nonfiction writers, too, have lately returned to the subject. In 2004, the Yale historian David Blight edited “Passages to Freedom,” an anthology of essays on the Underground Railroad. The following year, Fergus Bordewich published “Bound for Canaan,” the first national history of the Railroad in more than a century. And last year, Eric Foner, a historian at Columbia, published “Gateway to Freedom,” about the Railroad’s operations in New York City. Between 1869 and 2002, there were two adult biographies of Harriet Tubman, the Railroad’s most famous “conductor”; more than four times as many have been published since then, together with a growing number of books about her for children and young adults—five in the nineteen-seventies, six in the nineteen-eighties, twenty-one in the nineteen-nineties, and more than thirty since the turn of this century. An HBO bio-pic about Tubman is in development, and earlier this year the U.S. Treasury announced that, beginning in the next decade, she will appear on the twenty-dollar bill.

Other public and private entities have likewise taken up the cause. Since 1998, the National Park Service has been working to create a Network to Freedom, a system of federally designated, locally managed Underground Railroad sites around the country. The first national museum dedicated to the subject, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, opened in Cincinnati in 2004, and next March the Park Service will inaugurate its first Railroad-related national monument: the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park, in Cambridge, Maryland, near Tubman’s birthplace.

This outpouring of interest suggests that we have collectively caught on to what McKim long ago understood: that the stories of those who fled slavery and those who helped them to freedom are among the most moving in our nation’s history. It was McKim’s hope that these stories would excite our admiration, reverence, and indignation, and they do. But, as more recent work has made clear, they should also incite our curiosity and skepticism: about how the Underground Railroad really worked, why stories about it so consistently work on us, and what they teach us—or spare us from learning—about ourselves and our nation.

No one knows who coined the term. Some ascribe it to a thwarted slave owner, others to a runaway slave. It first appeared in print in an abolitionist newspaper in 1839, at the end of a decade when railways had come to symbolize prosperity and progress, and three thousand miles of actual track had been laid across the nation. Frederick Douglass used the term in his 1845 autobiography—where he laments that indiscreet abolitionists are turning it into “an upperground railroad”—and Harriet Beecher Stowe used it in 1852, in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” when one slave-catcher cautions another against delaying pursuit of a fugitive “till the gal’s been carried on the underground line.” By the following year, the Times was reporting that the term had “come into very general use to designate the organized arrangements made in various sections of the country, to aid fugitives from slavery.”

Seldom has our national lexicon acquired a phrase so appealing to the imagination, or so open to misinterpretation. In his new novel, Colson Whitehead exploits both those qualities by doing knowingly what nearly every young child first learning our history does naïvely: taking the term “Underground Railroad” literally. His protagonist, a teen-age girl named Cora, flees the Georgia plantation where she was born into slavery and heads north on a series of rickety subterranean trains—one- or two-car numbers, driven by actual conductors and reached via caves or through trapdoors in buildings owned by sympathetic whites.

Whitehead has a taste for fantastical infrastructure, first revealed via the psychically active elevators in his brilliant début novel, “The Intuitionist.” Those elevators were the perfect device—mingling symbolic resonance with Marvel Comics glee, absolved of improbability by the particularity and force of Whitehead’s imagination. In “The Underground Railroad,” he more or less reverses his earlier trick. Rather than imbue a manufactured box with mystery, he turns our most evocative national metaphor into a mechanical contraption. It is a clever choice, reminding us that a metaphor never got anyone to freedom. Among his other concerns in this book, Whitehead wants to know what does: how the Underground Railroad really worked, and at what cost, and for whom.

Those questions were first asked in an extensive and systematic way by an Ohio State University historian named Wilbur Siebert. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, when many parents of the Civil War dead were still alive to grieve for their children and former slaves still outnumbered freeborn African-Americans, Siebert began contacting surviving abolitionists or their kin and asking them to describe their efforts to aid fugitives from slavery. The resulting history, published in 1898 and entitled “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom,” depicted a network of more than three thousand anti-slavery activists, most of them white, who helped ferry largely anonymous runaways to freedom. That history has been diffusing through the culture ever since, gathering additional details along the way and profoundly shaping our image of the Underground Railroad. In that image, a clandestine organization of abolitionists—many of them Quaker or otherwise motivated by religious ideals—used covert methods (tunnels, trapdoors, concealed passageways) and secret signals (lanterns set in windows, quilts hung on laundry lines) to help convey enslaved African-Americans to freedom.

That story, like so many that we tell about our nation’s past, has a tricky relationship to the truth: not quite wrong, but simplified; not quite a myth, but mythologized. For one thing, far from being centrally organized, the Underground Railroad was what we might today call an emergent system: it arose through the largely unrelated actions of individuals and small groups, many of whom were oblivious of one another’s existence. What’s more, even the most active abolitionists spent only a tiny fraction of their time on surreptitious adventures with packing crates and the like; typically, they carried out crucial but banal tasks like fund-raising, education, and legal assistance. And while fugitives did often need to conceal themselves en route to freedom, most of their hiding places were mundane and catch-as-catch-can—haylofts and spare bedrooms and swamps and caves, not bespoke hidey-holes built by underground engineers. As for the notion that passengers on the Underground Railroad communicated with one another by means of quilts: that idea originated, without any evident basis, in the eighties (the nineteen -eighties).

The putative role of textiles and architecture in antebellum activism doesn’t matter that much, but other distortions in Siebert’s story do. No one disputes that white abolitionists were active in the Underground Railroad, but later scholars argued that Siebert had exaggerated both their numbers and their importance, while downplaying or ignoring the role played by African-Americans. Among religious sects, for example, the Quakers generally receive the most credit for resisting slavery, with secondary acknowledgment going to the wave of evangelical Christianity that spread across the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, in the movement known as the Second Great Awakening. Yet scant mainstream attention goes to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was established in 1816, in direct response to American racism and the institution of slavery, and played at least as crucial a role in raising money, aiding fugitives, and helping former slaves who had found their way to freedom make a new life.

This lopsided awareness holds not only for institutions but for individuals. Many people know of William Lloyd Garrison, one of the country’s leading white anti-slavery activists, while almost no one knows about the black abolitionist William Still—one of the most effective operators and most important historians of the Underground Railroad, whose book about it, published a quarter of a century before Siebert’s, was based on detailed notes he kept while helping six hundred and forty-nine fugitives onward toward freedom. Likewise, more people know the name of Levi Coffin, a white Midwestern Quaker, than that of Louis Napoleon, a freeborn black abolitionist, even though both risked their lives to help thousands of fugitives to safety.

Link copied

This allocation of credit is inversely proportional to the risk that white and black anti-slavery activists faced. It took courage almost everywhere in antebellum America to actively oppose slavery, and some white abolitionists paid a price. A few were killed; some died in prison; others, facing arrest or worse, fled to Canada. But these were the exceptions. Most whites faced only fines and the opprobrium of some in their community, while those who lived in anti-slavery strongholds, as many did, went about their business with near-impunity.

Black abolitionists, by contrast, always put life and liberty on the line. If caught, free blacks faced the possibility of being illegally sold into slavery, while fugitives turned agents faced potential reënslavement, torture, and murder. Harriet Tubman is rightly famous for how boldly she faced those risks: first when she fled slavery herself; then during the roughly twenty return trips she made to the South to help bring others to freedom; and, finally, during the war, when she accompanied Union forces into the Carolinas, where they disrupted supply lines and, under her direction, liberated some seven hundred and fifty slaves. By then, slaveholders in her home state of Maryland were clamoring for her capture, dead or alive, and, in the words of her first biographer, publicly debating “the different cruel devices by which she would be tortured and put to death.”

Tubman, of course, is the one black conductor on the Underground Railroad whose fame is commensurate with her work. She is also the only black conductor most people know—though William Still’s reputation may be on the rise, courtesy of his small but compelling role in the uneven but often excellent TV series “Underground.” Still, while white abolitionists remain statistically overrepresented in stories about the Underground Railroad, the recent set suggests that, more than a century after Siebert, the balance may finally be shifting. “Who built it?” one of Whitehead’s fugitives asks, on first reaching a station on the Underground Railroad and peering down a tunnel where iron tracks disappear into darkness. “Who builds anything in this country?” the agent answers.

The fugitive-slave narrative presents a curious paradox. In terms of content, it describes one of the darkest eras of American history; in terms of form, it is, in a way, the perfect American story. Its plot is the central one of Western literature: a hero goes on a journey. Its protagonist obeys the dictates of her conscience instead of the dictates of the state, thereby satisfying our national appetite for righteous outlaws. And its narrative arc bends in our preferred direction: from Tubman to Katniss Everdeen, from “The Shawshank Redemption” to Cheryl Strayed, we adore stories of individuals who fight their way to actual or psychological freedom.

Although such heroes make their journeys under duress, fugitive-slave stories are also a form of travel narrative. And, while in real life fugitives ran in every imaginable direction and were often caught or forced to turn back or died en route, in our stories the direction of travel is more nearly uniform. On the Underground Railroad, geography is plot: the South represents iniquity and bondage, the North enlightenment and freedom.

Whitehead, a canny storyteller, makes use of this narrative tradition in “The Underground Railroad,” while also considerably complicating it. Freedom is illusory in his novel, and iniquity unbound by latitude, but he knows that the story of slavery is fundamentally the story of America, and he uses Cora’s journey to observe our nation, from an upper-crust mixed-race family in Boston to a farming community in Indiana. Some of the finest parts of the novel involve the effort to make sense of a new place—whether through the tiny attic window from which Cora studies the cultural, political, and natural landscape of a North Carolina town or on the long, strange wagon ride she takes through a Tennessee landscape devastated by wildfire. As in “Lolita,” the moral crisis is so consuming that it’s easy to miss the journey—but the journey is the essence of this novel.

Indeed, the most effective liberties that Whitehead takes are not with Cora’s mode of transport but with the terrain through which she travels. Station by station, he builds a physical landscape out of the chronology of African-American history. Cora’s northward journey first lands her in South Carolina, where what initially seems to be a policy of paternalistic benevolence toward blacks turns out to mask a series of disturbing medical interventions: a kind of early, statewide Tuskegee experiment. From there, she moves on to North Carolina, which has implemented, to genocidal ends, the ideals of the American Colonization Society—a real organization and social movement, evoked but unmentioned by Whitehead, that sought to end slavery and return all blacks to Africa, not least to make real the enduring fantasy of a white America. In Whitehead’s fictional version, new race laws forbid blacks to enter the state, and those caught within its borders are tortured, murdered, and left hanging on trees as a warning to others. North Carolina, one character observes, has succeeded in abolishing slavery. “On the contrary,” another corrects him. “We abolished niggers.”

As all this suggests, Cora is trying to escape from much more than a plantation. In the temporally elastic landscape through which she flees, it is slavery, as much as the slave-catcher, that is pursuing her, and anyone alive in today’s America knows that she will never entirely outrun it. Indeed, at times Cora seems to be already traversing a future bereft of full freedom—the landscape blighted by proto-Jim Crow, her journey a private Great Migration. Behind the slave-catcher we can almost glimpse the police officer misusing lethal force; behind the manacles on the walls of a train depot, the bars of mass incarceration.

Still, for all the liberties that “The Underground Railroad” takes with the past, they have nothing on those in “Underground Airlines” (Mulholland Books), by the novelist and playwright Ben Winters, best known for his 2009 parody, “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters.” (As it happens, Colson Whitehead’s previous book was about zombies.) Winters posits an alternate history in which the Civil War was averted and slavery, never abolished on the national level, persists into our own era, in what are called the Hard Four: Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the Carolinas, which together hold three million people in bondage. The protagonist, known mostly as Victor, is a fugitive slave who, after being apprehended, makes a Faustian bargain: in exchange for keeping his freedom, he agrees to work for the U.S. Marshals Service to catch other runaways.

When “Underground Airlines” opens, Victor is working his two-hundred-and-tenth case, trying to track down a mysterious fugitive, nicknamed Jackdaw, who has run away from an Alabama textile plantation. To find him, Victor must infiltrate the national anti-slavery network known as the Underground Airlines—not a literal entity here but “the root of a grand, extended metaphor,” now updated: airport security, gate agents, connecting flights, baggage handlers. “The Airlines flies on the ground, in package trucks and unmarked vans and stolen tractor-trailers,” Winters writes. “It flies in the illicit adjustment of numbers on packing slips, in the suborning of plantation guards and the bribing of border security agents, in the small arts of persuasion: by threat or cashier’s check or blow job.”

Winters, also the author of several mysteries, is working partly in the genre of the hardboiled detective novel; Victor is a classic noir antihero, whose self-interested amorality cloaks a troubled heart. But “Underground Airlines” also belongs to the tradition of counterfactual secession stories, à la Harry Turtledove’s “The Guns of the South” and MacKinlay Kantor’s “If the South Had Won the Civil War.” Such alternate histories run the risk of piling on textbooky details in the interest of proving the credibility of events that never happened, but Winters gets the balance right. He is careful to set up a plausible case for how history shifted off-kilter (Lincoln is assassinated before an armed conflict can break out; Congress, in grief and chaos, jams through a compromise that preserves both the Union and slavery), and he paints a convincing picture of what fugitive life would look like in our own era. (Homeland Security has a division called Internal Border and Regulation, the slave-catchers’ most fearsome tools are technological, and plantation overseers are supplied by private contractors.) But he is ultimately far more interested in the political, intellectual, and moral compromises that people make in order to live in the presence of, and sustain the existence of, legal bondage. Like Whitehead, though in a strikingly different way, he wants to get us to see the past in the present—the innumerable ways that we still live in a world made by slavery.

The first train ride that Cora takes in “The Underground Railroad” begins just below a farmhouse in rural Georgia and ends underneath a tavern in South Carolina. Whitehead, who knows his history, sneaks a little asterisk into the escape. “It was commonly held,” he writes, “that the underground railroad did not operate this far south.”

It did not. Contrary to a claim made by Siebert and subsequently reflected in myriad popular representations, the Underground Railroad didn’t lead “from the Southern states to Canada.” In fact, with very rare exceptions, it didn’t operate below the Mason-Dixon Line at all. Aside from a few outposts in border states, the Railroad was a Northern institution. As a result, for the roughly sixty per cent of America’s slaves who lived in the Deep South in 1860, it was largely unknown and entirely useless.

These are inconvenient facts for those who like to locate America’s antebellum conscience in the North. Had that region really been so principled, it wouldn’t have needed a clandestine system to convey fugitives beyond its borders to a foreign nation. Instead, while slavery itself was against the law in the North, upholding the institution of slavery was the law. As a nation, the United States regarded it as a legitimate practice, respected the right of white Southerners to own other human beings, and expressed that respect in laws that governed not half but all of the land.

This was a moral disaster for our country, and a terror for fugitive slaves. The obligation to return them to their owners was enshrined in the Constitution, then further codified in 1793, and in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850—which, as Foner notes, was among the most draconian laws ever enacted in this nation. It rendered impotent any Northern ordinances designed to protect fugitives; compelled citizens to assist in capturing them; set harsh civil and criminal punishments for failing to do so; created a legal document ordering a specific fugitive to be returned to his or her master that could not be challenged in any court of law; and established a fee system whereby officials adjudicating fugitive-slave cases earned ten dollars if they decided in favor of the owner and five if they decided for the slave.

“We could see no spot, this side of the ocean, where we could be free,” Frederick Douglass wrote in his autobiography: fugitives themselves knew that they were only marginally better off in the ostensibly free state of Ohio than across the border in Kentucky, only marginally safer in Maine or Michigan or Wisconsin than in Maryland and North Carolina and Washington, D.C. Outside of scattered pockets in upstate New York, Massachusetts, and the Midwest, moral opposition to slavery was not the norm above the Mason-Dixon Line, and fugitives were not exactly welcomed with open arms. In 1858, an editorial in a Vermont newspaper demanded that “a log must be laid across the track of the underground railroad,” and went on to argue, in terms that echo today’s debates over refugees, for the immediate cessation of “the illegal introduction of colored persons in the free states” to “prevent a large yearly increase of that class of population which is hanging like a millstone around the neck of our industrial progress.” Several ostensibly free states, including Illinois and Indiana, did just that, passing laws that prohibited free blacks from settling inside their borders. On the eve of the Civil War, the mayor of New York proposed that the city secede from the Union to protect its economic relationship with the South.

We should not be surprised, then, that most people who slipped the bonds of slavery did not look north. In fact, despite its popularity today, the Underground Railroad was perhaps the least popular way for slaves to seek their freedom. Instead, those who fled generally headed toward Spanish Florida, Mexico, the Caribbean, Native American communities in the Southeast, free-black neighborhoods in the upper South, or Maroon communities—clandestine societies of former slaves, some fifty of which existed in the South from 1672 until the end of the Civil War. Together, such runaways likely outnumbered those who, aided by Northern abolitionists, made their way to free states or to Canada.

Moreover, most slaves who sought to be free didn’t run at all. Instead, they chose to pursue liberty through other means. Some saved up money and purchased their freedom. Others managed to earn a legal judgment in their favor—for instance, by having or claiming to have a white mother (beginning in Colonial times, slave status, like Judaism, passed down through the maternal line), or by claiming to have been manumitted. In “Slaves Without Masters,” the historian Ira Berlin quotes an irate man addressing a neighbor who had freed his slaves. “I will venture to assert,” he complained, “that a vastly greater number of slave people have passed and are passing now as your free men than you ever owned.”

The more you try to put the Underground Railroad in context, in other words, the tinier it seems. Most runaways did not head north, and most slaves who sought their liberty did not run away. And then there is the largest and most important context, the one we least like to acknowledge: from the vast, vicious, legally permitted, fiercely defended enterprise that was American slavery, almost no one ever escaped at all.

No one knows for sure how many enslaved Americans escaped with the help of the Underground Railroad. Foner estimates that, between 1830 and 1860, some thirty thousand fugitives passed through its networks to freedom. Other calculations suggest that the total number is closer to fifty thousand—or, at the highest end, twice that many.

What we do know for sure is this: in 1860, the number of people in bondage in the United States was nearly four million. By then, slavery in this country was more than two hundred years old, and although estimates are hard to come by, perhaps twice that many million African-Americans had lived their lives in chains. Most accounts of fugitive slaves do not invoke those numbers, and most Americans do not know them. The Underground Railroad is a numerator without a denominator.

The problem, then, is not the stories we tell; it’s the stories we don’t tell. In 1988, after her own story about a runaway slave, “Beloved,” won the Pulitzer Prize, Toni Morrison described the scope of this silence. “There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of or recollect the absences of slaves,” Morrison said. “There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby. There’s no three-hundred-foot tower. There’s no small bench by the road. There is not even a tree scored, an initial that I can visit or you can visit in Charleston or Savannah or New York or Providence, or, better still, on the banks of the Mississippi.”

In the decades since Morrison spoke, all of that has only barely begun to change. We have told a few more stories, organized a few more exhibits, planned a few new museums, including one devoted to all of African-American history, opening next month on the National Mall, in Washington, D.C., and the privately funded Whitney Plantation, in Louisiana, the first to be wholly dedicated to slavery. Yet, more than a hundred and fifty years after the Emancipation Proclamation, you still will not find, anywhere in our country, a federal monument to the millions of people whom we, as a nation, kept in bondage. To put that omission in perspective, there are more than eighty national parks and monuments and countless other federal memorials commemorating the Civil War. That war lasted four years. Slavery lasted two and a half centuries.

Until the very end of that time, most white Americans, North and South, either actively fought to maintain the institution of slavery or passively sustained and benefitted from it. Only a small fraction had the moral clarity to recognize its evils without caveat or compromise, and, before the war broke out, very few did anything to directly challenge it. Fewer still took the kind of action that later made agents of the Underground Railroad such widely admired figures. Exactly how few is hard to know, but most historians now dismiss Siebert’s original tally of three thousand as considerably exaggerated, compiled as it was from post-hoc accounts. Eric Foner, making the best of difficult data, suggests that, across the country and throughout the duration of slavery, the number of white Americans who regularly aided fugitives was in the hundreds.

Only after the fact—when it no longer required vision or courage or personal sacrifice; when the Civil War was over and the effort to distance ourselves from the moral stain of slavery had begun—did large numbers of white Americans grow interested in being part of the story of African-American liberation. That interest led to the first major renovation and expansion of our favorite piece of mythic infrastructure, a project that began with the work of Wilbur Siebert. A similar expansion is under way in our own times. Much of it is welcome: over all, the recent crop of underground stories feature more black agency, fewer white saviors, greater attentiveness not only to runaways but to what they were running from. The boom in public exhibitions and institutions honoring Railroad sites, however, in part reflects the fact that it has now become not only morally but also economically advantageous to be associated with the Underground Railroad; in contrast to even twenty years ago, significant numbers of people will pay to visit such places. A similar trend is appearing in private real estate. As the historian David Blight wondered, “Is there a realtor in the Northern or border states selling old or historic homes, largely to white people, who has not contemplated the market value of space that might have been used in the nineteenth century to hide black people who were fugitives from slavery?”

That desire to literally own part of the story of the Underground Railroad is extremely widespread and is much of what makes it so popular in the first place. In the entire history of slavery, the Railroad offers one of the few narratives in which white Americans can plausibly appear as heroes. It is also one of the few slavery narratives that feature black Americans as heroes—which is to say, one of the few that emphasize the courage, intelligence, and humanity of enslaved African-Americans rather than their subjugation and misery. By rights, the shame of oppression should fall exclusively on the oppressor, yet one of the most insidious effects of tyranny is to shift some of that emotional burden onto the oppressed. The Underground Railroad relieves black and white Americans alike, although in very different ways, of the burden of feeling ashamed.

White Americans also feature as villains in Underground Railroad stories, of course, but often in ways that minimize over-all white responsibility. Because the stories focus on the fugitive, much of the viciousness of slavery is displaced onto the slave-catcher—an odious figure, to be sure, but ultimately an epiphenomenon of an odious system. Some recent Underground Railroad stories manage to resist that figure’s allure. Victor, the slave-catcher in “Underground Airlines,” is interesting not only because he is a former fugitive but because he is an essentially bureaucratic figure—one of many such people employed by the federal government to navigate and enforce the byzantine system by which slavery endures. But Arnold Ridgeway, the slave-catcher in Colson Whitehead’s novel, and August Pullman, in “Underground,” are Ahab-like characters, privately and demonically obsessed with tracking down specific fugitives. They both come off as irrationally committed to the hunt (and, like all supervillains, irrationally unkillable), and both risk locating the atrocities of slavery in individual pathology.

In reality, and notwithstanding the viciousness of its many enforcers, slavery was institutional. The Underground Railroad, by contrast, was personal: a scattering of private citizens, acting on conscience, and connected for the most part only as the constellations are—from a great distance, by their light. They have earned our admiration and reverence, as McKim knew they would, and we have made much of their few stories, in part for suspect reasons: because they assuage our conscience, distract us from tragedy with thrilling adventures, give us a comparatively comfortable place to rest in a profoundly uncomfortable past.

Yet there are also deep and honorable reasons that we are drawn to these stories: they show us the best parts of ourselves and articulate our finest vision of our nation. When Congress approved funding for the Network to Freedom, it noted, correctly, that “the Underground Railroad bridged the divides of race, religion, sectional differences, and nationality; spanned state lines and international borders; and joined the American ideals of liberty and freedom expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the extraordinary actions of ordinary men and women working in common purpose to free a people.”

It is to our credit if these are the Americans to whom we want to trace our moral genealogy. But we should not confuse the fact that they took extraordinary actions with the notion that they lived in extraordinary times. One of the biases of retrospection is to believe that the moral crises of the past were clearer than our own—that, had we been alive at the time, we would have recognized them, known what to do about them, and known when the time had come to do so. That is a fantasy. Iniquity is always coercive and insidious and intimidating, and lived reality is always a muddle, and the kind of clarity that leads to action comes not from without but from within. The great virtue of a figurative railroad is that, when someone needs it—and someone always needs it—we don’t have to build it. We are it, if we choose. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Annette Gordon-Reed

By Hilton Als

By Eyal Press

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

The underground railroad.

During the era of slavery, the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North.

Social Studies, U.S. History

Home of Levi Coffin

Historic image of the home of American Quaker and abolitionist Levi Coffin located in Cincinnati, Ohio, with a group of African Americans out front.

Photography by Cincinnati Museum Center

During the era of slavery , the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North. The name “ Underground Railroad ” was used metaphorically, not literally. It was not an actual railroad, but it served the same purpose—it transported people long distances. It also did not run underground, but through homes, barns, churches, and businesses. The people who worked for the Underground Railroad had a passion for justice and drive to end the practice of slavery —a drive so strong that they risked their lives and jeopardized their own freedom to help enslaved people escape from bondage and keep them safe along the route.

According to some estimates, between 1810 and 1850, the Underground Railroad helped to guide one hundred thousand enslaved people to freedom. As the network grew, the railroad metaphor stuck. “Conductors” guided runaway enslaved people from place to place along the routes. The places that sheltered the runaways were referred to as “stations,” and the people who hid the enslaved people were called “station masters.” The fugitives traveling along the routes were called “passengers,” and those who had arrived at the safe houses were called “cargo.”

Contemporary scholarship has shown that most of those who participated in the Underground Railroad largely worked alone, rather than as part of an organized group. There were people from many occupations and income levels, including former enslaved persons . According to historical accounts of the Railroad, conductors often posed as enslaved people and snuck the runaways out of plantations. Due to the danger associated with capture, they conducted much of their activity at night. The conductors and passengers traveled from safe-house to safe-house, often with 16-19 kilometers (10–20 miles) between each stop. Lanterns in the windows welcomed them and promised safety. Patrols seeking to catch enslaved people were frequently hot on their heels.

These images of the Underground Railroad stuck in the minds of the nation, and they captured the hearts of writers, who told suspenseful stories of dark, dangerous passages and dramatic enslaved person escapes . However, historians who study the Railroad struggle to separate truth from myth . A number of prominent historians who have devoted their life’s work to uncover the truths of the Underground Railroad claim that much of the activity was not in fact hidden, but rather, conducted openly and in broad daylight. Eric Foner is one of these historians. He dug deep into the history of the Railroad and found that though a large network did exist that kept its activities secret, the network became so powerful that it extended the limits of its myth . Even so, the Underground Railroad was at the heart of the abolitionist movement. The Railroad heightened divisions between the North and South, which set the stage for the Civil War .

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Underground Railroad

145 pages • 4 hours read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Before You Read

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

What is the symbolic significance of depicting the Underground Railroad as an actual rail line? Use specific quotes to support your analysis.

Choose one of the book’s major settings (the Randall plantation in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, the Valentine farm in Indiana). Use and cite primary and secondary historical sources to compare the book’s depictions with historical record.

What is the book’s central message about the character and origins of the American nation? Use direct quotes and analysis to support your position.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Colson Whitehead

Apex Hides the Hurt

Colson Whitehead

Crook Manifesto

Harlem Shuffle

John Henry Days

The Intuitionist

The Nickel Boys

Featured Collections

Black History Month Reads

View Collection

#CommonReads 2020

Historical Fiction

Popular Book Club Picks

Pulitzer Prize Fiction Awardees &...

Essay Service Examples Government Underground Railroad

Essay about Underground Railroad

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

- American History

- Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network which was established and used by the enslaved...

Slavery affected 12.5 million slaves in the United States, due to such a large number of slaves...

- Book Review

- Harriet Tubman

Slave Narratives of the Underground Railroad by Christine Rudisel is a detailed book about the...

- African American History

- Slavery in the World

Slavery is a topic in history that has been taught throughout the years. Slavery has been around...

- Human Behavior

- Intelligence

Operation Anaconda was supposed to be a decisive 3-day assault by U.S. military and Afghan forces...

Over the past few years it has been said countless times that suicide rate in the military is...

- Conflict Management

Conflict is a fact of life and occurs for a variety of reasons, such as differing perspectives,...

In aviation people tend to obey the principle of ethics and morals. Ethics is more in some...

- Lord of The Flies

Democracy is a system of government where the leading part is chosen by the people to govern...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

What is the underground railroad.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger .

-harriet tubman, 1896.

The Underground Railroad —the resistance to enslavement through escape and flight, through the end of the Civil War—refers to the efforts of enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom by escaping bondage. Wherever slavery existed, there were efforts to escape. At first to maroon communities in remote or rugged terrain on the edge of settled areas and eventually across state and international borders. These acts of self-emancipation labeled slaves as "fugitives," "escapees," or "runaways," but in retrospect " freedom seeker " is a more accurate description. Many freedom seekers began their journey unaided and many completed their self-emancipation without assistance, but each subsequent decade in which slavery was legal in the United States, there was an increase in active efforts to assist escape. The decision to assist a freedom seeker may have been spontaneous. However, in some places, especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 , the Underground Railroad was deliberate and organized. Despite the illegality of their actions, people of all races, class and genders participated in this widespread form of civil disobedience. Freedom seekers went in many directions – Canada, Mexico, Spanish Florida, Indian territory, the West, Caribbean islands and Europe.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/ H.L. STEPHENS.

Wherever there were enslaved African Americans, there were people eager to escape. There was slavery in all original thirteen colonies, in Spanish California, Louisiana, and Florida; Central and South America; and on all of the Caribbean islands until the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and British abolition of slavery (1834). The Underground Railroad started at the place of enslavement. The routes followed natural and man-made modes of transportation - rivers, canals, bays, the Atlantic Coast, ferries and river crossings, road and trails. Locations close to ports, free territories and international boundaries prompted many escapes. As research continues, new routes are discovered and will be represented on the map. Using ingenuity, freedom seekers drew on courage and intelligence to concoct disguises, forgeries and other strategies. Slave catchers and enslavers watched for runaways on the expected routes of escape and used the stimulus of advertised rewards to encourage public complicity in apprehension. Help came from diverse groups: enslaved and free blacks, American Indians, and people of different religious and ethnic groups.

Maritime industry was an important source for spreading information, in addition to offering employment and transportation. The Pacific West Coast and possibly Alaska became destinations because of ties to the whaling industry. Military service was an additional option; thousands of African Americans joined from the Colonial Era to the Civil War to gain their freedom. During the Civil War, many freedom seekers sought protection and liberty by escaping to the lines of the Union army.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/ CAROL M. HIGHSMITH

Last updated: July 22, 2022

The Underground Railroad History

This essay will provide an overview of the history of the Underground Railroad, its significance in the abolitionist movement, and the heroes who risked their lives to help slaves escape to freedom. At PapersOwl, you’ll also come across free essay samples that pertain to Harriet Tubman.

How it works

The Underground Railroad was very important in history by helping many slaves to escape. The Underground Railroad holds a fascinating history, many plots and plans to escape, as well as people that helped slaves to escape, but escaping was often dangerous due to multiple reasons. The Underground Railroad helped tremendously with slave escapes by means of all of the routes and safehouses set up along the country. Due to roughly 100,000 escaped slaves, there was a lack of workers which made it harder for slavery to continue.

Later, the Emancipation Proclamation along with the Thirteenth Amendment were passed making slavery illegal. All three events led to the end of slavery.

The Underground Railroad goes back a couple of centuries in time. The Underground Railroad was formed in the early 19th century. (Harriet Tubman) The first record of this system was on May 12, 1786. Most of the information we have about the Underground Railroad comes from accounts that happened after the Civil War, but we may never know the exact number of slaves that were able to escape or become free by using this system. (Harriet Tubman) The system was a network of Northerners who helped runaway slaves. The Underground Railroad came to an end in 1865 after the Thirteenth Amendment was passed getting rid of all slavery in the United States. (Harriet Tubman)

There were many working parts involved in the Underground Railroad one of them was escape trails. Slave escape routes were called lines. It is believed that about 3,000 miles of Underground Railroad trails were in Ohio. (Ohio History Central) Escape routes were often indirect to confuse the slave catchers. There was never an exact route to escape but many different ones to choose from. (Harriet Tubman) Slaves often traveled on foot and they had very little to no food while on their journey. After 1850, routes led fugitive slaves to either Canada, Mexico, or the Caribbean. (Eiu.Edu) Canada was known by slaves as the promised land because once the slaves reached there they were officially away from the slave catchers.

Safe houses were another major part of the Underground Railroad. The safe houses were called depots or stations. As many as 1,000 houses in the north were used as stations. (Harriet Tubman) Stations were recognized by lit lanterns hanging outside. Slaves often made their escapes at night and hid in barns, basements, train cars, churches, or cupboards. (Harriet Tubman) Ashtabula, Painesville, Cleveland, Sandusky, Toledo, Huron, Lorain, and Conneaut were cities along Lake Erie that were the starting points of slave transport from Ohio to Canada. (Ohio History Central)

Special codes played a huge part in the Underground Railroad as well. People that worked with the Underground Railroad had special codes and knocks to get into the safe houses that the station keepers knew. (Sawyer 38-39) One of the common passwords was “William Penn”. (Sawyer 38-39) Slaves used railroad code and songs called spirituals to communicate with each other. (Harriet Tubman) The Underground Railroad organization was not very tight due to the fact that it was illegal. About 100,000 slaves escaped through the Underground Railroad from 1810 – 1860. Most slaves came from Kentucky, Virginia, and Maryland but few slaves escaped from the south.

There are famous people and organizations in history that played a major point in slave escapes. Harriet Tubman escaped slavery and helped start the Underground Railroad. (Taylor 3) She was nicknamed Moses because she was the person in history who led the most slaves to freedom. She also successfully freed all of her slaves and never lost one. Almost all slaves were helped by whites during their escape, Slaves rarely escaped without help. (Sawyer 7) Quakers started helping slaves escape all the way back to the 1780’s. (Ohio History Central)

Levi Coffin helped over 3,000 slaves escape their masters and he was nicknamed the president of the underground railroad by abolitionists. (Ohio History Central) There was a 100 stair staircase known as the freedom stairway that went from the bottom of the Ohio River to the top of the hill. John Rankin lived here and he put out a light in the window that signified when it was safe for the slaves to pass the river and come to the house. William Wells Brown helped many slaves by taking them across Lake Erie to Buffalo or Detroit. (Sawyer 5) Some slaves that escaped through the Underground Railroad came back to slavery to be conductors and help others escape. John Parker is a former slave who conducted one of the busiest sections of the Underground Railroad and transported slaves across the Ohio River. (Eiu.Edu) Organizations in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia raised money to set up temporary jobs and houses for the slaves.

The Underground Railroad was a very dangerous organization due to all of the aspects that took place. If slaves were captured they were branded, put in jail, sold back into slavery, sometimes killed, or flogged which is another word for whipped. (Eiu.Edu) Traveling slaves had to fight against animals and severe temperatures as well. In 1850 the fugitive slave law put whites who helped slaves in jail or made them pay a high fine. If they got caught they were either put in jail for 6 months or they had to pay a 1,000 dollar fine. (Harriet Tubman) Free Africans could still be caught and sent back to slavery though. (Harriet Tubman) This happened when slave catchers destroyed their free papers which took away their ticket out of slavery.

Slavery was a huge problem for a period of time in the 19th century. Many people thought it was wrong and tried to stop it but it didn’t end for many more years. Since slavery wasn’t stopped right away people tried to find ways to help slaves escape. The Underground Railroad was one of the most well known and important systems that carried out this task. Many people and places were involved in this system and in the end it turned out to be successful based off of the fact that around 100,000 slaves in total escaped using the Underground Railroad.”

Cite this page

The Underground Railroad History. (2021, Apr 10). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/

"The Underground Railroad History." PapersOwl.com , 10 Apr 2021, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/

PapersOwl.com. (2021). The Underground Railroad History . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/ [Accessed: 10 Jun. 2024]

"The Underground Railroad History." PapersOwl.com, Apr 10, 2021. Accessed June 10, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/

"The Underground Railroad History," PapersOwl.com , 10-Apr-2021. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/. [Accessed: 10-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2021). The Underground Railroad History . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-underground-railroad-history/ [Accessed: 10-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home / Essay Samples / Government / Underground / The Underground Railroad – An Act Of Resistance

The Underground Railroad – An Act Of Resistance

- Category: History , Government

- Topic: Slavery in The World , Underground

Pages: 2 (998 words)

Views: 1164

- Downloads: -->

Works Cited

- “Fugitive Slave Act 1850.” Avalon Project - Fugitive Slave Act 1850, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/ 19th_century/fugitive.asp.

- National Endowment for the Humanities. “The Nashville Daily Union. [Volume] (Nashville, Tenn.) 1862-1866, February 17, 1863, Image 3.” News about Chronicling America RSS, Published by an Association of Printers, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/ sn83025718/1863-02-17/ed-1/seq-3/.

- Still, William. “Preserving American Freedom.” Journal C of Station No. 2 of the Underground Railroad, Agent William Still (Excerpt), June 2-29, 1855 | Exhibits.hsp.org, http://we b.archive.org/web/20160102082306/http://digitalhistory.hsp.org/pafrm/doc/journalc.

- Tate, Gayle T. “Free Black Resistance in the Antebellum Era, 1830 to 1860.” Journal of Black Studies, Rutgers University, vol. 28, no. No. 6, July 1998, pp. 764–782.

- UNDERGROUND RAILROAD, http://crab.rutgers.edu/~glasker/UNDERGRAIL.htm.

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Reign of Terror Essays

Constitution Essays

Social Security Essays

Republic Essays

War on Drugs Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->