Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

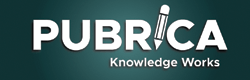

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

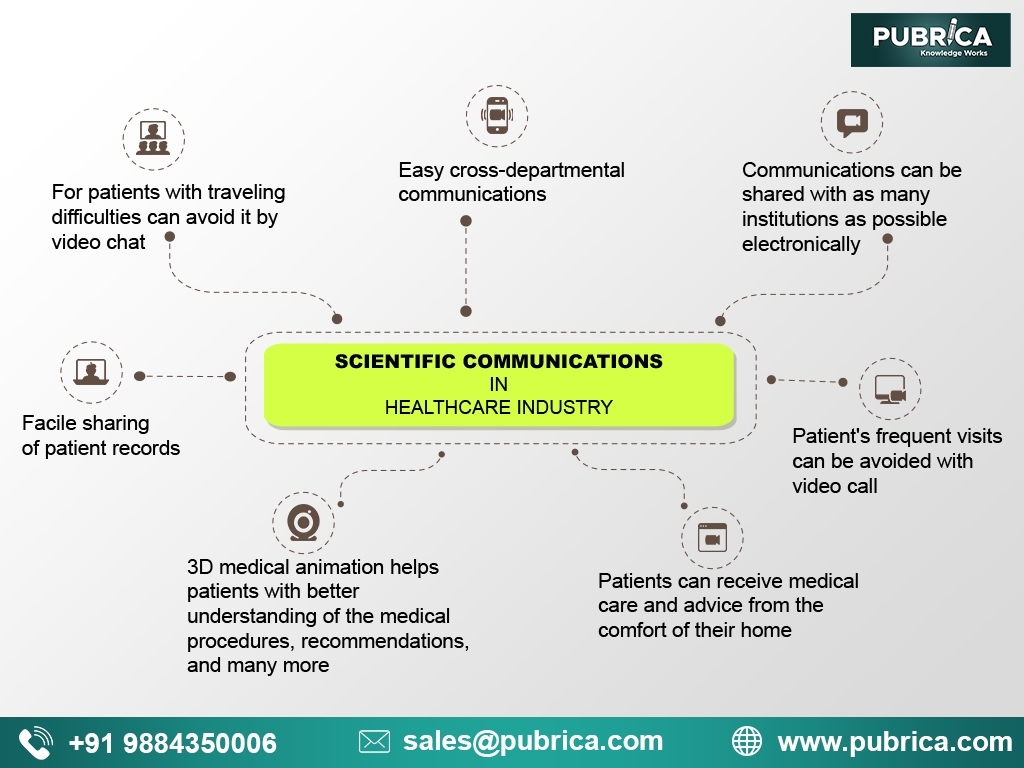

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

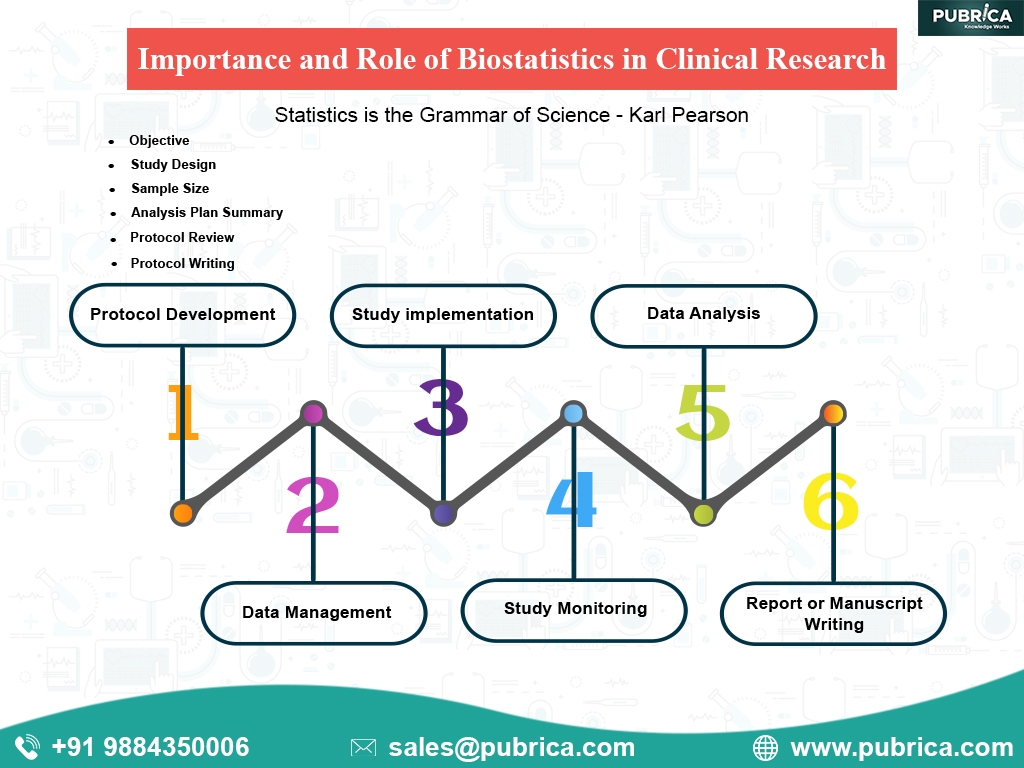

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

College of Arts and Sciences

History and American Studies

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- History Resources

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Student Research Grants

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Phi Alpha Theta

Alumni Intros

- Internships

Literature Review Guidelines

Literature review (historiographic essay): making sense of what has been written on your topic., goals of a literature review:.

Before doing work in primary sources, historians must know what has been written on their topic. They must be familiar with theories and arguments–as well as facts–that appear in secondary sources.

Before you proceed with your research project, you too must be familiar with the literature: you do not want to waste time on theories that others have disproved and you want to take full advantage of what others have argued. You want to be able to discuss and analyze your topic.

Your literature review will demonstrate your familiarity with your topic’s secondary literature.

GUIDELINES FOR A LITERATURE REVIEW:

1) LENGTH: 8-10 pages of text for Senior Theses (485) (consult with your professor for other classes), with either footnotes or endnotes and with a works-consulted bibliography. [See also the citation guide on this site.]

2) NUMBER OF WORKS REVIEWED: Depends on the assignment, but for Senior Theses (485), at least ten is typical.

3) CHOOSING WORKS:

Your literature review must include enough works to provide evidence of both the breadth and the depth of the research on your topic or, at least, one important angle of it. The number of works necessary to do this will depend on your topic. For most topics, AT LEAST TEN works (mostly books but also significant scholarly articles) are necessary, although you will not necessarily give all of them equal treatment in your paper (e.g., some might appear in notes rather than the essay). 4) ORGANIZING/ARRANGING THE LITERATURE:

As you uncover the literature (i.e., secondary writing) on your topic, you should determine how the various pieces relate to each other. Your ability to do so will demonstrate your understanding of the evolution of literature.

You might determine that the literature makes sense when divided by time period, by methodology, by sources, by discipline, by thematic focus, by race, ethnicity, and/or gender of author, or by political ideology. This list is not exhaustive. You might also decide to subdivide categories based on other criteria. There is no “rule” on divisions—historians wrote the literature without consulting each other and without regard to the goal of fitting into a neat, obvious organization useful to students.

The key step is to FIGURE OUT the most logical, clarifying angle. Do not arbitrarily choose a categorization; use the one that the literature seems to fall into. How do you do that? For every source, you should note its thesis, date, author background, methodology, and sources. Does a pattern appear when you consider such information from each of your sources? If so, you have a possible thesis about the literature. If not, you might still have a thesis.

Consider: Are there missing elements in the literature? For example, no works published during a particular (usually fairly lengthy) time period? Or do studies appear after long neglect of a topic? Do interpretations change at some point? Does the major methodology being used change? Do interpretations vary based on sources used?

Follow these links for more help on analyzing historiography and historical perspective .

5) CONTENTS OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

The literature review is a research paper with three ingredients:

a) A brief discussion of the issue (the person, event, idea). [While this section should be brief, it needs to set up the thesis and literature that follow.] b) Your thesis about the literature c) A clear argument, using the works on topic as evidence, i.e., you discuss the sources in relation to your thesis, not as a separate topic.

These ingredients must be presented in an essay with an introduction, body, and conclusion.

6) ARGUING YOUR THESIS:

The thesis of a literature review should not only describe how the literature has evolved, but also provide a clear evaluation of that literature. You should assess the literature in terms of the quality of either individual works or categories of works. For instance, you might argue that a certain approach (e.g. social history, cultural history, or another) is better because it deals with a more complex view of the issue or because they use a wider array of source materials more effectively. You should also ensure that you integrate that evaluation throughout your argument. Doing so might include negative assessments of some works in order to reinforce your argument regarding the positive qualities of other works and approaches to the topic.

Within each group, you should provide essential information about each work: the author’s thesis, the work’s title and date, the author’s supporting arguments and major evidence.

In most cases, arranging the sources chronologically by publication date within each section makes the most sense because earlier works influenced later ones in one way or another. Reference to publication date also indicates that you are aware of this significant historiographical element.

As you discuss each work, DO NOT FORGET WHY YOU ARE DISCUSSING IT. YOU ARE PRESENTING AND SUPPORTING A THESIS ABOUT THE LITERATURE.

When discussing a particular work for the first time, you should refer to it by the author’s full name, the work’s title, and year of publication (either in parentheses after the title or worked into the sentence).

For example, “The field of slavery studies has recently been transformed by Ben Johnson’s The New Slave (2001)” and “Joe Doe argues in his 1997 study, Slavery in America, that . . . .”

Your paper should always note secondary sources’ relationship to each other, particularly in terms of your thesis about the literature (e.g., “Unlike Smith’s work, Mary Brown’s analysis reaches the conclusion that . . . .” and “Because of Anderson’s reliance on the president’s personal papers, his interpretation differs from Barry’s”). The various pieces of the literature are “related” to each other, so you need to indicate to the reader some of that relationship. (It helps the reader follow your thesis, and it convinces the reader that you know what you are talking about.)

7) DOCUMENTATION:

Each source you discuss in your paper must be documented using footnotes/endnotes and a bibliography. Providing author and title and date in the paper is not sufficient. Use correct Turabian/Chicago Manual of Style form. [See Bibliography and Footnotes/Endnotes pages.]

In addition, further supporting, but less significant, sources should be included in content foot or endnotes . (e.g., “For a similar argument to Ben Johnson’s, see John Terry, The Slave Who Was New (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 3-45.”)

8 ) CONCLUSION OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

Your conclusion should not only reiterate your argument (thesis), but also discuss questions that remain unanswered by the literature. What has the literature accomplished? What has not been studied? What debates need to be settled?

Additional writing guidelines

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 26, 2024

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

HIST495 Introduction to Historical Interpretation (History Honors)

- Getting Started

- Consulting Reference Materials for Overview/Background Information

- Finding Primary Sources

- Finding Secondary Sources (Books and Articles)

- Locating Book Reviews

Guidelines and Examples

3 simple steps to get your literature review done (nus libraries).

- Creating an Annotated Bibliography

- Strategies for Building Your Bibliography

- Special Collections and Archives Outside of the US

- Rose Library, Emory University and Other Archives Within Georgia

- Writing & Citing

- Library Assignments

- Introduction to Literature Reviews (UNC)

- Literature Review Guidelines (Univ. of Mary Washington)

- Organizing Research for Arts and Humanities Papers and Theses: Writing A Literature Review

- Write a Literature Review (JHU)

- Example from the University of Mary Washington

- << Previous: Locating Book Reviews

- Next: Creating an Annotated Bibliography >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 11:50 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.emory.edu/main/histhonors

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Historical Research

Definition:

Historical research is the process of investigating and studying past events, people, and societies using a variety of sources and methods. This type of research aims to reconstruct and interpret the past based on the available evidence.

Types of Historical Research

There are several types of historical research, including:

Descriptive Research

This type of historical research focuses on describing events, people, or cultures in detail. It can involve examining artifacts, documents, or other sources of information to create a detailed account of what happened or existed.

Analytical Research

This type of historical research aims to explain why events, people, or cultures occurred in a certain way. It involves analyzing data to identify patterns, causes, and effects, and making interpretations based on this analysis.

Comparative Research

This type of historical research involves comparing two or more events, people, or cultures to identify similarities and differences. This can help researchers understand the unique characteristics of each and how they interacted with each other.

Interpretive Research

This type of historical research focuses on interpreting the meaning of past events, people, or cultures. It can involve analyzing cultural symbols, beliefs, and practices to understand their significance in a particular historical context.

Quantitative Research

This type of historical research involves using statistical methods to analyze historical data. It can involve examining demographic information, economic indicators, or other quantitative data to identify patterns and trends.

Qualitative Research

This type of historical research involves examining non-numerical data such as personal accounts, letters, or diaries. It can provide insights into the experiences and perspectives of individuals during a particular historical period.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Archival research : This involves analyzing documents and records that have been preserved over time, such as government records, diaries, letters, newspapers, and photographs. Archival research is often conducted in libraries, archives, and museums.

- Oral history : This involves conducting interviews with individuals who have lived through a particular historical period or event. Oral history can provide a unique perspective on past events and can help to fill gaps in the historical record.

- Artifact analysis: This involves examining physical objects from the past, such as tools, clothing, and artwork, to gain insights into past cultures and practices.

- Secondary sources: This involves analyzing published works, such as books, articles, and academic papers, that discuss past events and cultures. Secondary sources can provide context and insights into the historical period being studied.

- Statistical analysis : This involves analyzing numerical data from the past, such as census records or economic data, to identify patterns and trends.

- Fieldwork : This involves conducting on-site research in a particular location, such as visiting a historical site or conducting ethnographic research in a particular community. Fieldwork can provide a firsthand understanding of the culture and environment being studied.

- Content analysis: This involves analyzing the content of media from the past, such as films, television programs, and advertisements, to gain insights into cultural attitudes and beliefs.

Data Analysis Methods

- Content analysis : This involves analyzing the content of written or visual material, such as books, newspapers, or photographs, to identify patterns and themes. Content analysis can be used to identify changes in cultural values and beliefs over time.

- Textual analysis : This involves analyzing written texts, such as letters or diaries, to understand the experiences and perspectives of individuals during a particular historical period. Textual analysis can provide insights into how people lived and thought in the past.

- Discourse analysis : This involves analyzing how language is used to construct meaning and power relations in a particular historical period. Discourse analysis can help to identify how social and political ideologies were constructed and maintained over time.

- Statistical analysis: This involves using statistical methods to analyze numerical data, such as census records or economic data, to identify patterns and trends. Statistical analysis can help to identify changes in population demographics, economic conditions, and other factors over time.

- Comparative analysis : This involves comparing data from two or more historical periods or events to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help to identify patterns and trends that may not be apparent from analyzing data from a single historical period.

- Qualitative analysis: This involves analyzing non-numerical data, such as oral history interviews or ethnographic field notes, to identify themes and patterns. Qualitative analysis can provide a rich understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals in the past.

Historical Research Methodology

Here are the general steps involved in historical research methodology:

- Define the research question: Start by identifying a research question that you want to answer through your historical research. This question should be focused, specific, and relevant to your research goals.

- Review the literature: Conduct a review of the existing literature on the topic of your research question. This can involve reading books, articles, and academic papers to gain a thorough understanding of the existing research.

- Develop a research design : Develop a research design that outlines the methods you will use to collect and analyze data. This design should be based on the research question and should be feasible given the resources and time available.

- Collect data: Use the methods outlined in your research design to collect data on past events, people, and cultures. This can involve archival research, oral history interviews, artifact analysis, and other data collection methods.

- Analyze data : Analyze the data you have collected using the methods outlined in your research design. This can involve content analysis, textual analysis, statistical analysis, and other data analysis methods.

- Interpret findings : Use the results of your data analysis to draw meaningful insights and conclusions related to your research question. These insights should be grounded in the data and should be relevant to the research goals.

- Communicate results: Communicate your findings through a research report, academic paper, or other means. This should be done in a clear, concise, and well-organized manner, with appropriate citations and references to the literature.

Applications of Historical Research

Historical research has a wide range of applications in various fields, including:

- Education : Historical research can be used to develop curriculum materials that reflect a more accurate and inclusive representation of history. It can also be used to provide students with a deeper understanding of past events and cultures.

- Museums : Historical research is used to develop exhibits, programs, and other materials for museums. It can provide a more accurate and engaging presentation of historical events and artifacts.

- Public policy : Historical research is used to inform public policy decisions by providing insights into the historical context of current issues. It can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of past policies and programs.

- Business : Historical research can be used by businesses to understand the evolution of their industry and to identify trends that may affect their future success. It can also be used to develop marketing strategies that resonate with customers’ historical interests and values.

- Law : Historical research is used in legal proceedings to provide evidence and context for cases involving historical events or practices. It can also be used to inform the development of new laws and policies.

- Genealogy : Historical research can be used by individuals to trace their family history and to understand their ancestral roots.

- Cultural preservation : Historical research is used to preserve cultural heritage by documenting and interpreting past events, practices, and traditions. It can also be used to identify and preserve historical landmarks and artifacts.

Examples of Historical Research

Examples of Historical Research are as follows:

- Examining the history of race relations in the United States: Historical research could be used to explore the historical roots of racial inequality and injustice in the United States. This could help inform current efforts to address systemic racism and promote social justice.

- Tracing the evolution of political ideologies: Historical research could be used to study the development of political ideologies over time. This could help to contextualize current political debates and provide insights into the origins and evolution of political beliefs and values.

- Analyzing the impact of technology on society : Historical research could be used to explore the impact of technology on society over time. This could include examining the impact of previous technological revolutions (such as the industrial revolution) on society, as well as studying the current impact of emerging technologies on society and the environment.

- Documenting the history of marginalized communities : Historical research could be used to document the history of marginalized communities (such as LGBTQ+ communities or indigenous communities). This could help to preserve cultural heritage, promote social justice, and promote a more inclusive understanding of history.

Purpose of Historical Research

The purpose of historical research is to study the past in order to gain a better understanding of the present and to inform future decision-making. Some specific purposes of historical research include:

- To understand the origins of current events, practices, and institutions : Historical research can be used to explore the historical roots of current events, practices, and institutions. By understanding how things developed over time, we can gain a better understanding of the present.

- To develop a more accurate and inclusive understanding of history : Historical research can be used to correct inaccuracies and biases in historical narratives. By exploring different perspectives and sources of information, we can develop a more complete and nuanced understanding of history.

- To inform decision-making: Historical research can be used to inform decision-making in various fields, including education, public policy, business, and law. By understanding the historical context of current issues, we can make more informed decisions about how to address them.

- To preserve cultural heritage : Historical research can be used to document and preserve cultural heritage, including traditions, practices, and artifacts. By understanding the historical significance of these cultural elements, we can work to preserve them for future generations.

- To stimulate curiosity and critical thinking: Historical research can be used to stimulate curiosity and critical thinking about the past. By exploring different historical perspectives and interpretations, we can develop a more critical and reflective approach to understanding history and its relevance to the present.

When to use Historical Research

Historical research can be useful in a variety of contexts. Here are some examples of when historical research might be particularly appropriate:

- When examining the historical roots of current events: Historical research can be used to explore the historical roots of current events, practices, and institutions. By understanding how things developed over time, we can gain a better understanding of the present.

- When examining the historical context of a particular topic : Historical research can be used to explore the historical context of a particular topic, such as a social issue, political debate, or scientific development. By understanding the historical context, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the topic and its significance.

- When exploring the evolution of a particular field or discipline : Historical research can be used to explore the evolution of a particular field or discipline, such as medicine, law, or art. By understanding the historical development of the field, we can gain a better understanding of its current state and future directions.

- When examining the impact of past events on current society : Historical research can be used to examine the impact of past events (such as wars, revolutions, or social movements) on current society. By understanding the historical context and impact of these events, we can gain insights into current social and political issues.

- When studying the cultural heritage of a particular community or group : Historical research can be used to document and preserve the cultural heritage of a particular community or group. By understanding the historical significance of cultural practices, traditions, and artifacts, we can work to preserve them for future generations.

Characteristics of Historical Research

The following are some characteristics of historical research:

- Focus on the past : Historical research focuses on events, people, and phenomena of the past. It seeks to understand how things developed over time and how they relate to current events.

- Reliance on primary sources: Historical research relies on primary sources such as letters, diaries, newspapers, government documents, and other artifacts from the period being studied. These sources provide firsthand accounts of events and can help researchers gain a more accurate understanding of the past.

- Interpretation of data : Historical research involves interpretation of data from primary sources. Researchers analyze and interpret data to draw conclusions about the past.

- Use of multiple sources: Historical research often involves using multiple sources of data to gain a more complete understanding of the past. By examining a range of sources, researchers can cross-reference information and validate their findings.

- Importance of context: Historical research emphasizes the importance of context. Researchers analyze the historical context in which events occurred and consider how that context influenced people’s actions and decisions.

- Subjectivity : Historical research is inherently subjective, as researchers interpret data and draw conclusions based on their own perspectives and biases. Researchers must be aware of their own biases and strive for objectivity in their analysis.

- Importance of historical significance: Historical research emphasizes the importance of historical significance. Researchers consider the historical significance of events, people, and phenomena and their impact on the present and future.

- Use of qualitative methods : Historical research often uses qualitative methods such as content analysis, discourse analysis, and narrative analysis to analyze data and draw conclusions about the past.

Advantages of Historical Research

There are several advantages to historical research:

- Provides a deeper understanding of the past : Historical research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of past events and how they have shaped current social, political, and economic conditions. This can help individuals and organizations make informed decisions about the future.

- Helps preserve cultural heritage: Historical research can be used to document and preserve cultural heritage. By studying the history of a particular culture, researchers can gain insights into the cultural practices and beliefs that have shaped that culture over time.

- Provides insights into long-term trends : Historical research can provide insights into long-term trends and patterns. By studying historical data over time, researchers can identify patterns and trends that may be difficult to discern from short-term data.

- Facilitates the development of hypotheses: Historical research can facilitate the development of hypotheses about how past events have influenced current conditions. These hypotheses can be tested using other research methods, such as experiments or surveys.

- Helps identify root causes of social problems : Historical research can help identify the root causes of social problems. By studying the historical context in which these problems developed, researchers can gain a better understanding of how they emerged and what factors may have contributed to their development.

- Provides a source of inspiration: Historical research can provide a source of inspiration for individuals and organizations seeking to address current social, political, and economic challenges. By studying the accomplishments and struggles of past generations, researchers can gain insights into how to address current challenges.

Limitations of Historical Research

Some Limitations of Historical Research are as follows:

- Reliance on incomplete or biased data: Historical research is often limited by the availability and quality of data. Many primary sources have been lost, destroyed, or are inaccessible, making it difficult to get a complete picture of historical events. Additionally, some primary sources may be biased or represent only one perspective on an event.

- Difficulty in generalizing findings: Historical research is often specific to a particular time and place and may not be easily generalized to other contexts. This makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions about human behavior or social phenomena.

- Lack of control over variables : Historical research often lacks control over variables. Researchers cannot manipulate or control historical events, making it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Subjectivity of interpretation : Historical research is often subjective because researchers must interpret data and draw conclusions based on their own biases and perspectives. Different researchers may interpret the same data differently, leading to different conclusions.

- Limited ability to test hypotheses: Historical research is often limited in its ability to test hypotheses. Because the events being studied have already occurred, researchers cannot manipulate variables or conduct experiments to test their hypotheses.

- Lack of objectivity: Historical research is often subjective, and researchers must be aware of their own biases and strive for objectivity in their analysis. However, it can be difficult to maintain objectivity when studying events that are emotionally charged or controversial.

- Limited generalizability: Historical research is often limited in its generalizability, as the events and conditions being studied may be specific to a particular time and place. This makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions that apply to other contexts or time periods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 9:12 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes: