This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-Around Health Services Research

This video presentation by Alison B. Hamilton for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) focuses on qualitative study design, data collection, and fundamentals of data analysis. The presentation uses examples from a VA women's health services project in order to demonstrate how the rapid collection of data can be used generate findings that could be used immediately.

The video presentation includes a downloadable handout of the slides which can be accessed here: PDF Handout

Hamilton, A. B. (2013). Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-Around Health Services Research, VA Women's Health Research Network. Retrieved from: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780

Related links

- http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

Practical Applications of Rapid Qualitative Analysis for Operations, Quality Improvement, and Research in Dynamically Changing Hospital Environments

- PMID: 36585315

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2022.11.003

Background: Health care systems are in a constant state of change. As such, methods to quickly acquire and analyze data are essential to effectively evaluate current processes and improvement projects. Rapid qualitative analysis offers an expeditious approach to evaluate complex, dynamic, and time-sensitive issues.

Methods: We used rapid data acquisition and qualitative methods to assess six real-world problems the hospitalist field faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. We iteratively modified and applied a six-step framework for conducting rapid qualitative analysis, including determining if rapid methods are appropriate, creating a team, selecting a data collection approach, data analysis, and synthesis and dissemination. Virtual platforms were used for focus groups and interviews; templated summaries and matrix analyses were then applied to allow for rapid qualitative analyses.

Results: We conducted six projects using rapid data acquisition and rapid qualitative analysis from December 4, 2020, to January 14, 2022, each of which included 23 to 33 participants. One project involved participants from a single institution; the remainder included participants from 15 to 24 institutions. These projects led to the refinement of an adapted rapid qualitative method for evaluation of hospitalist-driven operational, research, and quality improvement efforts. We describe how we used these methods and disseminated our results. We also discuss situations for which rapid qualitative methods are well-suited and strengths and weaknesses of the methods.

Conclusion: Rapid qualitative methods paired with rapid data acquisition can be employed for prompt turnaround assessments of quality, operational, and research projects in complex health care environments. Although rapid qualitative analysis is not meant to replace more traditional qualitative methods, it may be appropriate in certain situations. Application of a framework to guide projects using a rapid qualitative approach can help provide structure to the analysis and instill confidence in the findings.

Copyright © 2022 The Joint Commission. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- Focus Groups

- Qualitative Research

- Quality Improvement

Adaptability on Shifting Ground: a Rapid Qualitative Assessment of Multi-institutional Inpatient Surge Planning and Workforce Deployment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Original Research: Qualitative Research

- Published: 22 March 2022

- Volume 37 , pages 3956–3964, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Angela Keniston MSPH ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1399-2881 1 ,

- Matthew Sakumoto MD 2 ,

- Gopi J. Astik MD/MS 3 ,

- Andrew Auerbach MD, MPH 4 ,

- Shaker M. Eid MD/MBA 5 ,

- Kirsten N. Kangelaris MD/MAS 6 ,

- Shradha A. Kulkarni MD 6 ,

- Tiffany Lee MA 7 ,

- Luci K. Leykum MD/MBA/MSc 8 ,

- Anne S. Linker MD 9 ,

- Devin T. Worster MD MPH 10 &

- Marisha Burden MD 11

1543 Accesses

9 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

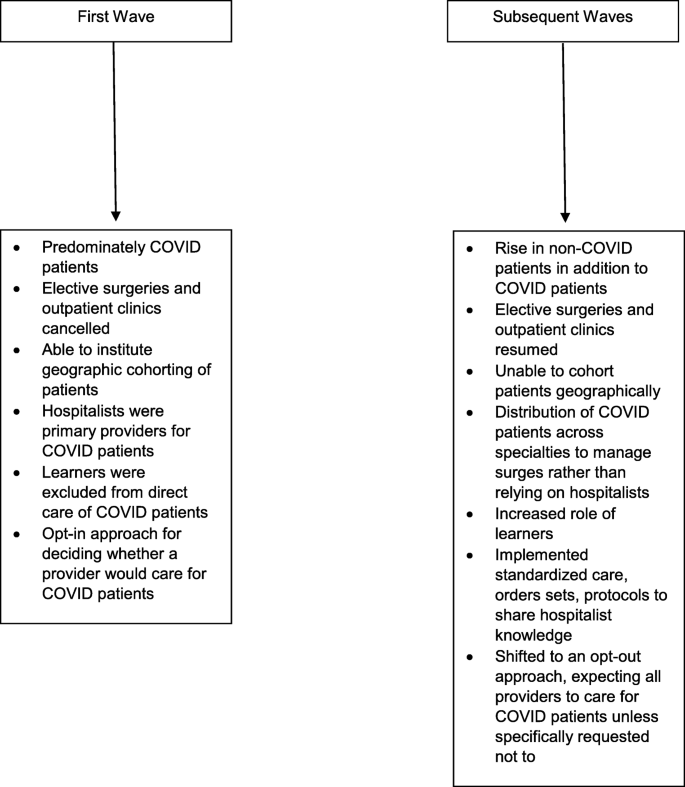

During the initial wave of COVID-19 hospitalizations, care delivery and workforce adaptations were rapidly implemented. In response to subsequent surges of patients, institutions have deployed, modified, and/or discontinued their workforce plans.

Using rapid qualitative methods, we sought to explore hospitalists’ experiences with workforce deployment, types of clinicians deployed, and challenges encountered with subsequent iterations of surge planning during the COVID-19 pandemic across a collaborative of hospital medicine groups.

Using rapid qualitative methods, focus groups were conducted in partnership with the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN). We interviewed physicians, advanced practice providers (APP), and physician researchers about (1) ongoing adaptations to the workforce as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) current struggles with workforce planning, and (3) evolution of workforce planning.

Key Results

We conducted five focus groups with 33 individuals from 24 institutions, representing 52% of HOMERuN sites. A variety of adaptations was described by participants, some common across institutions and others specific to the institution’s location and context. Adaptations implemented shifted from the first waves of COVID patients to subsequent waves. Three global themes also emerged: (1) adaptability and comfort with dynamic change, (2) the importance of the unique hospitalist skillset for effective surge planning and redeployment, and (3) the lack of universal solutions.

Conclusions

Hospital workforce adaptations to the COVID pandemic continued to evolve. While few approaches were universally effective in managing surges of patients, and successful adaptations were highly context dependent, the ability to navigate a complex system, adaptability, and comfort in a chaotic, dynamic environment were themes considered most critical to successful surge management. However, resource constraints and sustained high workload levels raised issues of burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of surge adaptations on hospitalist care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic utilizing a rapid qualitative analysis approach

Description of a Multi-faceted COVID-19 Pandemic Physician Workforce Plan at a Multi-site Academic Health System

The Impact of Hospital Capacity Strain: a Qualitative Analysis of Experience and Solutions at 13 Academic Medical Centers

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalists have been at the forefront of the pandemic, serving as clinicians and operational leaders. 1 , 2 The COVID-19 pandemic required addressing the influx of patients to not only emergency departments, but also to medical wards and intensive care units. As a result, existing disaster plans had to be rapidly modified and deployed to address surges in inpatient volume, often by hospitalists in collaboration with other stakeholders across healthcare organizations. 1 A variety of organization-, team-, and individual-level adaptations were rapidly implemented in response to surges of patients during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in March and April 2020. 3 , 4 Initial strategies included reduction of non-essential services, geographic cohorting of patients in respiratory isolation units (RIUs), implementing technology for communicating with and evaluating patients to reduce clinical staff exposure, allowing healthcare workers to opt out of direct care of COVID-19 patients, and deployment of healthcare workers from other specialties. 3 , 4 , 5 However, many of these strategies may not be sustainable practices.

In preparation for surge events, logistical planning for diagnostic testing, ensuring the availability of PPE, developing strategies for patient triage and cohorting, developing clinical protocols, addressing the physical and mental wellness of healthcare workers, developing communication plans, and surge planning specifically around key resources—physical space and beds, clinical and operational staff, equipment, and system coordination—should be addressed. 6 , 7 , 8 However, plans addressing these domains must be both systematic and highly adaptable. 6

In the subsequent months, most areas of the USA experienced a second, and sometimes third, wave of patients requiring hospitalization for COVID-19. 9 In response to these additional surges and continual significant challenges with the testing and treatment of COVID patients while also maintaining a safe work environment, institutions have updated, modified, and/or discontinued adaptations made earlier in the pandemic. 4 , 10 , 11 Our work provides novel insights regarding the ongoing challenges of sustained surges, the types of adaptations that have not been sustainable, and the new ways that the hospitalist skillset has been applied as the pandemic continues.

While a growing literature describes initial adaptations employed by hospitals and hospitalists, 1 , 3 , 12 , 13 , 14 further updates to workforce deployment and care processes with subsequent COVID-19 surges have not been described. This rapid qualitative evaluation of the inpatient surge planning and workforce deployment across multiple hospital medicine groups provides insight into the direct experience of hospital medicine clinicians and leaders who were responsible for both the development of surge plans and the delivery of care to patients in the setting of the implementation of surge plans. These focus groups were conducted as a part of efforts by the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) collaborative to rapidly collect and disseminate information needed by hospitalists to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. 15 Rapid qualitative methods are uniquely suited for quick assessment and evaluation while ensuring the same rigor of more traditional qualitative methods in time-sensitive situations. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

The constraints and demand on hospital medicine clinicians are different from those felt by intensivists and emergency department staff. The participants of these focus groups describe adaptations of different groups, insight into the challenges of an evolving pandemic and continual surges of patients, and insight into their experience, as both surge planners and frontline clinicians, with the solutions implemented.

Human Subjects

The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study as exempt from IRB review (COMIRB #: 21-4873).

Study Design

On December 4, 2020, we conducted five semi-structured focus groups with hospitalist physicians, advanced practice providers (APP), and hospitalist physician researchers participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), 20 a collaborative of hospitals, hospitalists, and multidisciplinary care teams founded in 2011. HOMERuN is a consortium of academic medical centers, primarily in urban settings, though geographically diverse with participating sites from the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, West, and Northwest, as previously described by Auerbach et al. 20 This group mobilized to create workgroups that collated and shared best practices for the COVID-19 pandemic. These focus groups explored the changes in each participating hospital’s approach to workforce deployment and organization of care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and identified the types of workforce and surge planning issues with which hospitalists are currently grappling.

Setting and Participants

Participants of the monthly HOMERuN collaborative call were electronically notified in advance that focus groups would be conducted during the next regularly scheduled Zoom call (December 4, 2020). Hospitalist physicians, APPs, hospitalist physician researchers, residents, and patient representatives participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) and present for the monthly collaborative call were included in the focus groups. The only exclusion criterion was refusal to participate. Individuals present for the call were not offered any incentive to participate.

At the start of the meeting, individuals who elected to call in were informed again of the plan to conduct focus groups, which would be recorded, and offered the chance to ask questions of moderators. If the attendees agreed to proceed, they were placed in a separate virtual breakout room for focus group participation, with a moderator assigned to each room. Each focus group was approximately 30 min in duration and had approximately six participants.

Interview Guide

The focus group guide was developed by the members of the HOMERuN workforce planning workgroup, convened in March 2020 to assess workforce and organizational adaptations undertaken in response to COVID-19. We asked participants to consider the following questions: (1) What adaptations have proved most useful to you? (2) What are you struggling with right now? (3) What are you changing now? (4) What important changes occurred between your first surge and later waves? Moderator Guide shown in the Appendix .

Data Collection

Prior to beginning each focus group, participants granted permission to record the conversation. During the focus groups, the moderators (MB, DW, GA, SK, AL, MS, AK) made field notes and observations to supplement the audio recordings. The audio recordings and field notes were used for the analysis rather than transcriptions of the focus groups.

Our analysis was conducted in a two-step process using a rapid qualitative analytic approach. 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 First, a team member who did not participate in the specific focus group used a standard template to create a summary of each group’s session, incorporating both the audio recording and the moderator’s field notes (MB, GA, SK, AL, MS, AK, LL). Second, all workgroup team members participated in creating an analysis matrix 21 of the summaries of each focus group. Each row was a focus group and each column referred to a unique question we asked each focus group. One workgroup member completed the matrix by logging key points summarized for each focus groups’ discussion of each question into the matrix (AK). Individually, workgroup members then identified themes and subthemes across all focus group discussions of each question (MB, GA, SK, AL, MS, AK, LL). As a group, workgroup team members then met to discuss and reach consensus regarding themes identified (MB, DW, GA, SK, AL, MS, AK, LL). As the focus groups were conducted simultaneously, all data were used in the analysis rather than in considering data saturation. Member checking, a technique for confirming the credibility of results, was conducted. 26 Two members of the workgroup who participated in a focus group but who did not moderate a focus group, create a summary, or participate in the analysis reviewed the findings to confirm the themes reflected their experience as a focus group participant (SE, KK).

Physicians, APPs, and physician researchers from 24 hospitals participated, representing 52% of HOMERuN sites, with 29 (88%) hospitalist physicians, three (9%) in another category (an APP, a resident, and a patient representative), and one (3%) unidentified participant. All but one of the hospitals represented were academic hospitals. One participant reported working at a VA hospital. Four hospitals had two participant representatives, one hospital had six participants, and 19 had one participant representative in attendance.

Participants described a variety of adaptations, some common across institutions and others specific to the institution’s location and context. Adaptations implemented shifted from the first waves of COVID patients to subsequent waves. Table 1 summarizes these adaptations and Figure 1 illustrates changes from initial to subsequent waves of patients. Table 2 highlights exemplar quotes for themes identified across the domains explored during the focus groups.

Changes over time.

Adaptations That Have Proved Most Useful

Managing high-capacity situations.

All groups discussed how they approached the decision to add capacity to care for a rapid increase in patients. Overall occupancy across the system or department census was often used to make decisions about adding providers to a particular site or deploying providers to other hospitals in the system. Often a decision to add capacity was dependent on how stretched providers felt, as opposed to specific triggers based on provider-to-patient ratios (which was felt to be challenging to define). Tiered surge plans were a commonly used adaptation for adding capacity, developed with guidance from institutional stakeholders, although participants described significant variability in such plans, with a range in the number of tiers from three to 36 levels. One participant described using triagists to direct patient flow and manage capacity, and this was noted to be helpful.

Recruitment and Staffing Strategies

Goodwill and volunteerism were insufficient to maintain adequate staffing over time. Some participants noted additional payments or compensation for working additional shifts. A number of participants described shifting from an opt-in approach for caring for COVID patients to an opt-out approach. Participants also described a shift from trying to cohort COVID patients on a small number of teams to distributing COVID patients to specialty teams depending on the patient’s primary complaint. This shift was intended to more uniformly distribute work across a broader group of clinicians. From initial to subsequent waves, geographic cohorting was reported as less operationally feasible because numbers of non-COVID patients were rising concomitantly with COVID numbers, and hospitals were typically at or beyond 100% utilization. Both APPs and non-hospitalists were deployed to extend admitting capacity, with varied models including direct care for COVID patients under the supervision of hospitalists or working remotely to write notes for the primary team. Several innovative staffing models were described. Examples included a virtualist model, 27 in which attending physicians rounded from home using iPads and called families to provide updates, or hiring “COVID-ists.” A flexible APP deployment model was also described where assignments were made based on both clinical expertise and patient census. When patient volumes were high, APPs were used for independent clinical care of patients, while at other times APPs were redeployed to care coordination tasks.

At first, hospitals sought to protect resident education, using physician attendings or APPs to care for COVID patients. Some participants described residents being asked to flex up to meet demand, but this request was felt to be at the expense of education. One participant described distributing housestaff across all teams rather than maintaining teaching and non-teaching teams. Other participants reported that housestaff were only in the ICUs. Most participants described excluding learners from COVID care, at least at first, because using residents required ACGME emergency authorization, though many reported wanting to include learners in the care of COVID patients particularly during subsequent waves. Participants recognized the value of residents or high-functioning interns who know how to manage inpatient logistics to support the care team.

Delivery Settings Outside of Hospital

One participant described setting up a field hospital but only for certain patients who were mobile and did not have any behavioral health issues. Another participant described converting a long-term acute-care (LTAC) hospital to a COVID hospital, which was considered very successful. A number of participants reported redistributing both patients and providers across a system of hospitals to manage surges in volume.

Communication Strategies

Participants described the importance of robust communication, including checking in with hospitalist and ICU colleagues and communication about current COVID-19 evidence and treatment guidelines. However, participants reported struggling to decide what the right frequency of communication might be, titrated to surge level, anxiety level, and knowledge level. Clinical pathways, order sets, and protocols were used to communicate current treatment guidelines as new clinical staff were deployed.

Persistent Struggles

Resource constraints.

These included insufficient negative pressure rooms, limited ICU capacity, and shortages in nursing and respiratory therapy staff. The most common concerns noted were nursing and respiratory therapy turnover. Organizations described significant attention paid to maintaining nursing ratios. Participants were concerned that even if there were sufficient beds or provider workforce, other disciplines within the hospital, such as nursing or respiratory therapy, were short-staffed and unable to adequately handle surges in volume. From the first wave to subsequent waves, participants described struggling with a surge in non-COVID patients and a concomitant resumption of elective surgeries and outpatient clinics, which decreased available beds, staff, and other resources for COVID patients. Space limitation was an issue not only for patient care, but also for providers attempting to distance from each other. Clinicians were in need of space to practice social distancing, especially given institutional rules about where staff were allowed to eat or take breaks. Finally, there was concern that a lack of redundancy in staffing plans made it difficult to flex up to cover shifts when hospitalists were unable to work.

Ongoing Struggle to Determine the Best Workforce Deployment Strategies

This was particularly true regarding the role of residents and balancing resident service and educational activities. Some found over time that trainees were more eager to care for COVID patients than originally thought, that leaving residents out of the workforce had unforeseen consequences, and that they could be included in the workforce safely. Participants reported having to continue to work on methods to determine the best workforce redeployment strategies and how to most effectively reorient new or returning workforce members. The higher non-COVID patient volume (including surgical/procedural and non-COVID medical patients) after the first wave complicated decision-making. Ultimately, there was a fixed workforce with limited ability to flex upwards without major structural changes (i.e., the workforce that was originally available from canceling clinics, canceling surgeries, etc. became less available and were now also facing increased volumes).

Important Changes that Occurred Between the First Surge and Later Waves

Changes in attitudes/moral issues/burnout.

Participants described heavy reliance on goodwill and volunteerism with the first wave, but that with later waves, providers were fatigued and goodwill had faded. Local factors that influenced decisions about team size, number of teams, and which providers staffed teams included the use of care protocols, order sets, and guidelines to support redeployed clinicians and hospitalist supervision of redeployed clinicians as well as burnout among providers. There were differing opinions on running workloads higher than normal versus trying to find/add in additional providers to manage the high numbers of patients. Participants reported that deploying subspecialists with historically less inpatient experience was challenging because subspecialists often lacked the hospital systems knowledge required to deliver inpatient care (i.e., working knowledge of how to navigate the electronic health record and other operational factors). To support specialists caring for COVID patients, participants described creating a COVID consult service to answer any COVID-specific questions and provide COVID-specific medical management as opposed to admitting patients to a COVID-specific team.

Burnout Increasingly Constrained the Ability to Adapt

Participants discussed the challenge of continued changes on a workforce experiencing burnout. Participants also described a normalization of caring for COVID patients that allowed a larger group of clinicians to be involved in COVID care. However, there was concern that these continual higher volumes are contributing to reduced morale, fatigue, and burnout, though it is unclear whether COVID or non-COVID volumes are the bigger issue.

Global Themes

Three global themes emerged across discussions of all questions: (1) adaptability and comfort with dynamic change, (2) the importance of the hospitalist skillset to effective surge planning and workforce deployment, and (3) the lack of universal solutions, in which there is no easy way to surge.

The healthcare workforce was redeployed in a variety of ways as the situation evolved. Iterative improvements were made with each fluctuation in COVID-19 patient volumes, and participants reported that their hospitalist groups become more comfortable with dynamic change over time. Factors affecting level of comfort with change included communication, degree of burnout, and the number and types of innovations. Adaptations both fostered and reinforced more functional collaborations and partnerships with clinical colleagues, and participants reported being able to continue to leverage improved collaborations in the future. Systems knowledge and systems process improvement have always been central to hospitalist work. 28 , 29 , 30 Participants felt that this skillset was critical to successful adaptations and augmented the hospitalist clinical skillset. The importance of tacit, implicit contextual knowledge in a time of rapid change was also apparent, and was felt to be a key reason why some clinicians were highly valued. However, there were no universal solutions described—the success of any one tactic for surge planning was highly dependent on the context in which it was applied. Challenges resulted from insufficient staffing and resources, often requiring clinical staff to flex up to meet demand, or flex into new roles that are not familiar or comfortable.

In this rapid qualitative evaluation of continued institutional adaptations in response to second and third waves of COVID-19, participants described a variety of useful adaptations but also described continued ongoing struggles. Despite multiple iterations of surge practices across multiple institutions, there were limited universal solutions to manage the surges beyond ensuring sufficient staffing as the ultimate crisis was a lack of resources (providers and other ancillary staff and sometimes critical other resources) to match the magnitude of the surge.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals associated with academic medical centers commonly struggled with hospital capacity strain, or patient volume in excess of the available beds, clinical staff, and equipment. 31 Previous work has noted that hospital capacity strain is complex and difficult to predict and the interventions that were perceived to have worked the best when facing strain were to ensure appropriate resources; however, less costly solutions were often deployed. 31 These decisions unfortunately negatively impact the workforce, and some studies have suggested that they may lead to negative patient outcomes as well as operational outcomes. COVID-19 has further stressed an already strained system. Work by Aiken et al. as well as Elliot et al. has highlighted that when workloads exceed certain thresholds, quality and operational outcomes decline. 32 , 33 , 34 Kamalahmadi et al. noted that it may actually be in the institution’s financial interest to lower census thresholds to optimize patient flow. 35

Despite continual innovation and a comfort with dynamic change, hospitals and hospitalists struggled to figure out how to best maximize the workforce for current and future surges in the setting of insufficient workforce, primarily because there is no perfect approach to navigating surges in patient volume without having a sufficient workforce supply. Predicting when the surge occurs is also challenging especially when complicated by a baseline increase in patients needing hospital care. Additionally, communicating surge needs was complicated as thresholds varied and were challenging to define in the setting of a continually evolving situation.

It was starkly apparent that agile systems that are capable of rapid adaptation were vital for meeting the demands of the dynamic US healthcare environment during the first and subsequent waves of COVID-19 hospitalizations and the hospitals in this study clearly adapted rapidly. Participants described the importance of creativity in designing approaches for local problems and comfort with a dynamic atmosphere in which consistent change was accepted as the new normal. Although there were a number of commonalities, such as using volunteers, APP staff, or the use of field hospitals, no single adaptation emerged across focus groups as a universal approach. High-level recommendations exist in the literature for managing an influx of patients due to a disaster or pandemic 36 , 37 ; however, a one-size approach fitting all situations does not exist. Hospitals can learn from one another, but will have to adapt in response to the contextual factors at their hospital.

The hospitalist skillset, beyond the clinical knowledge required for delivering high-quality inpatient care to medically complex patients, includes operational expertise and an ability to navigate complex systems. 28 , 38 In rapidly evolving, high-uncertainty situations like the pandemic, relationships provide the basis for effective communication, sense-making, and learning. 28 , 38 Hospitalists uniquely hold the relational and operational knowledge to be most effective under such conditions since they constantly navigate healthcare systems issues and are involved in managing process improvements for the inpatient setting.

As identified by participants in our focus groups, system constraints like staffing shortages and insufficient or irregular communication inhibited the ability of the workforce to innovate. As COVID-19 unfortunately becomes the norm of hospital care with likely intermittent upticks in patient numbers, hospital systems and hospitalists groups must begin to evolve their surge strategies to ensure proper staffing with sufficient flexibility to manage these surges in less disruptive ways.

Adaptations considered useful across participants include creating tiered surge plans, redeploying non-hospitalist physicians, APPs, and subspecialists to care for COVID-19 patients, redistributing COVID patients to specialist consult teams based on patients’ primary disease complaint, frequently collating and disseminating updated COVID-related evidence and guidelines, and creating and sharing COVID care pathways and order sets to standardize treatment. While most participants described excluding learners from COVID care, participants recognized the value of residents or high-functioning interns and many reported seeking to include learners in the care of COVID patients during subsequent waves. Finally, some participants described developing plans to care for COVID patients outside of the traditional hospital setting, including field hospitals and long-term acute-care hospitals converted to COVID patient care.

Our work has several strengths. This study employed rapid qualitative methods, useful in dynamic, real-world situations where the insights gathered are vital for immediate real-time application. 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 While the methods we used were not designed to quantify the strategies described by participants, qualitative analysis allows a deeper understanding of the context in which various strategies were implemented, the perspectives of frontline physicians and APPs as well as those developing operational plans, and the role of hospital medicine in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We interviewed a diverse cross section of hospitalists including physicians involved not only in frontline clinical care but also in COVID-related adaptations, APPs, and physician researchers. At the time the focus groups were conducted, each participant had been involved in one or more surges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because our participants were limited to members of the HOMERuN, our results may not be completely applicable to non-academic settings. In addition, there was a potential for participation bias if hospitalists who attended the meeting and participated in the focus groups were different in some way from those who did not attend and/or participate in the focus groups. The focus groups included physicians, APPs, and physician researchers working in the field of hospital medicine, so we did not capture the voice of the providers from other specialties. While participants represented hospitals from across the USA, individuals who elected to call in were assured during the focus groups that we would protect their confidentiality so we did not collect and analyze the qualitative data in such a way that we can assign specific institutions to specific solutions described.

Finally, while these focus groups were conducted more than a year ago, continual surges of patients and diminishing resources including space and clinical staff have necessitated adapting and evolving surge plans. Disseminating the findings from these focus groups would provide additional information, ideas, and potentially useful adaptations as hospitals and hospitalists across the country are faced with the ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospitals continued to evolve in the ways they have adapted to the challenges of the COVID pandemic. Few approaches were universally effective in managing surges of COVID-19 patients, and successful adaptations were highly context dependent. Hospitalists’ local systems knowledge has uniquely positioned them to manage ongoing adaptations in response to COVID-19, but resource constraints and sustained high workload levels raised issues of burnout. The findings of this rapid qualitative evaluation bring to light the challenge of creating single solutions that will be applicable across hospitals that operate in different ways, and underscore the need for further research to identify particular workflows that are associated with improved patient-relevant outcomes.

Bowden K, Burnham EL, Keniston A, et al. Harnessing the Power of Hospitalists in Operational Disaster Planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2732-2737.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Persoff J, Ornoff D, Little C. The Role of Hospital Medicine in Emergency Preparedness: A Framework for Hospitalist Leadership in Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):713-718.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Auerbach A, O'Leary KJ, Greysen SR, et al. Hospital Ward Adaptation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):483-488.

Linker AS, Kulkarni SA, Astik GJ, Keniston A, Sakumoto M, Eid SM, Burden M, Leykum LK; HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Working Group. Bracing for the Wave: a Multi-Institutional Survey Analysis of Inpatient Workforce Adaptations in the First Phase of COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med . 2021;36(11):3456-3461.

Kumar SI, Borok Z. Filling the Bench: Faculty Surge Deployment in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic. NEJM Catalyst. Published 10/29/2020. Accessed 1/20/2022.

Anesi GL, Lynch Y, Evans L. A Conceptual and Adaptable Approach to Hospital Preparedness for Acute Surge Events Due to Emerging Infectious Diseases. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(4):e0110-e0110.

Vranas KC, Golden SE, Mathews KS, et al. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on ICU Organization, Care Processes, and Frontline Clinician Experiences: A Qualitative Study. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Coates A, Fuad AO, Hodgson A, Bourgeault IL. Health workforce strategies in response to major health events: a rapid scoping review with lessons learned for the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):154.

Roser Max RH, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus . Published 2020. Accessed 2/28/2021.

Washington DC: Office of the Inspector General; April 3, 2020. Report no. OEI-06-20-00300.

Mhango M, Dzobo M, Chitungo I, Dzinamarira T. COVID-19 Risk Factors Among Health Workers: A Rapid Review. Safety Health Work. 2020;11(3):262-265.

Article Google Scholar

Garg M, Wray CM. Hospital Medicine Management in the Time of COVID-19: Preparing for a Sprint and a Marathon. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):305-307.

Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: Pediatric Residents Caring for Adults During COVID-19's First Wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(12):763-764.

Bloom-Feshbach K, Berger RE, Dubroff RP, McNairy ML, Kim A, Evans AT. The Virtual Hospitalist: a Critical Innovation During the COVID-19 Crisis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021:1-4.

HOMERuN. http://hospitalinnovate.org Accessed July 23, 2017.

Beebe J. Rapid qualitative inquiry : a field guide to team-based assessment / James Beebe . 2nd ed. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield; 2014.

Google Scholar

Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):11.

Lewinski AA, Crowley MJ, Miller C, et al. Applied Rapid Qualitative Analysis to Develop a Contextually Appropriate Intervention and Increase the Likelihood of Uptake. Med Care. 2021;59.

Hamilton A. Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. Paper presented at: Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research & Development Cyberseminar; 12/11/2013, 2013.

Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420.

Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866.

Brown DR, Hernández A, Saint-Jean G, et al. A participatory action research pilot study of urban health disparities using rapid assessment response and evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):28-38.

Burks DJ, Robbins R, Durtschi JP. American Indian gay, bisexual and two-spirit men: a rapid assessment of HIV/AIDS risk factors, barriers to prevention and culturally-sensitive intervention. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(3):283-298.

Vindrola-Padros C, Chisnall G, Cooper S, et al. Carrying Out Rapid Qualitative Research During a Pandemic: Emerging Lessons From COVID-19. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(14):2192-2204.

Zuchowski JL, Chrystal JG, Hamilton AB, et al. Coordinating Care Across Health Care Systems for Veterans With Gynecologic Malignancies: A Qualitative Analysis. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1:S53-s60.

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802-1811.

Bloom-Feshbach K, Berger RE, Dubroff RP, McNairy ML, Kim A, Evans AT. The Virtual Hospitalist: a Critical Innovation During the COVID-19 Crisis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1771-1774.

Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of "hospitalists" in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011.

The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:2-95.

Arogyaswamy S VN, Keniston A, Apgar S, Bowden K, Diaz M, Kantor M, McBeth L, Burden M. Hospital-capacity strain: A qualitative analysis of solutions utilized by academic medical centers. J Gen Intern Med.

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993.

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM. Hospital staffing, organization, and quality of care: cross-national findings. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(1):5-13.

Elliott DJ, Young RS, Brice J, Aguiar R, Kolm P. Effect of hospitalist workload on the quality and efficiency of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):786-793.

Kamalahmadi M, Bretthauer K, Helm J, et al. Mixing It Up: Operational Impact of Hospitalist Caseload and Case-mix. Baruch College Zicklin School of Business Research Paper No 2019-10-02. 2019.

Hick JL, Einav S, Hanfling D, et al. Surge capacity principles: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e1S-e16S.

Einav S, Hick JL, Hanfling D, et al. Surge capacity logistics: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e17S-43S.

O'Leary KJ, Williams MV. The evolution and future of hospital medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):418-423.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Thanks to members of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Group: Brigham and Women’s Hospital—Stephanie Mueller, MD MPH and Jeffrey Schnipper, MD MPH; Elsevier Publishing—Jennifer Goldstein, MD MSc; Emory University School of Medicine—Khaalisha Ajala, MD MBA; Obsinet Tadesse Merid, MD; and TaRessa Wills, MD; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine—Shaker M. Eid, MD MBA; Ifedayo Kuye, MD MBA; and Amit Pahwa, MD; Mount Sinai Hospital—Krishna Chokshi, MD; Horatio Holzer, MD; Chris Kellner, MD; Anne S. Linker, MD; and Vinh Nguyen, MD; Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine—Gopi Astik, MD MSc; Oregon Health and Science University—James Anstey, MD; James Clements, MD; and Anya Solotskaya, MD; Penn State University College of Medicine—Omrana Pasha, MD; Stanford University—Samantha Wang, MD; The Ohio State University College of Medicine—Jennifer Allen, MD and Kristen Lewis, MD; Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and Mayo Clinic—Alan A. Kubey, MD FACP; University of California, San Francisco—Andrew Auerbach, MD MPH; Amy Berger, MD PhD; Sneha Daya, MD; Archna Eniasivam, MD; Armond Esmaili, MD; Margaret Fang, MD MPH; Shubhra Gupta, MD; James Harrison, PhD; Emily Insetta, MD; Kirsten Kangelaris, MD; Kristen Kipps, MD; Zhenya Krapivinsky, MD; Shradha Kulkarni, MD; Rashmi Manjunath, MD; Sirisha Narayana, MD; Nishita Nigam, MD; Anna Parks, MD; Sumant Ranji, MD; Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, MAEd; Yalda Shahram, MD; Noa Simchoni, MD PhD; Matthew Sakumoto, MD; and Charlie M. Wray, DO; University of Chicago—Elizabeth Murphy, MD SFHM; Greg Ruhnke, MD; and Andrew Schram, MD MBA; University of Colorado School of Medicine—Marisha Burden, MD; Amira del Pino-Jones, MD; Angela Keniston, MSPH; Chris King, MD; and Katie E. Raffel, MD; University of Florida College of Medicine—Nila Radhakrishnan, MD and Nick Kattan, MD; University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine—Ethan Kuperman, MD MSc; University of Kentucky—John Romond, MD; Joe Sweigart, MD FHM FACP; and Sarah Vick, MD; University of Miami Health System—Chadwick Flowers, MD; Efren Manjarrez, MD; and Magdalena Murman, MD MAEd; University of New Mexico School of Medicine—Charles Pizanis and Kendall Rogers, MD CPE FACP SFHM; University of Pennsylvania—Ryan Greysen, MD MPH; Matthew Mitchell, PhD; and Todd Hecht, MD; University of Pittsburgh—Gena M. Walker, MD FHM; University of Texas, Austin Dell Medical School—W. Michael Brode, MD; Luci K. Leykum, MD MBA MSc; Kirsten Nieto, MD; and Sherine Salib, MD FACP; University of Virginia School of Medicine—Rachel Weiss, MD; University of Washington—Dan Cabrera, MD MPH and Naomi Shike, MD MSc; University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health—Blair P. Golden, MD MS; Sean O’Neill, MD; and David Sterken, MD; Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine—Sarah Hartigan, MD; Weill Cornell Medicine—Devin T. Worster, MD MPH; Yale School of Medicine—Rebecca Slotkin, MD; HOMERuN PFAC—Martie Carnie Catherine Hanson and Georgiann Ziegler.

The views expressed do not represent the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or other organizations affiliated with the authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 12401 E. 17th Avenue, Mail Stop F782, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA

Angela Keniston MSPH

Division of General Internal Medicine, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA

Matthew Sakumoto MD

Division of Hospital Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA

Gopi J. Astik MD/MS

University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA

Andrew Auerbach MD, MPH

Division of Hospital Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

Shaker M. Eid MD/MBA

Division of Hospital Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

Kirsten N. Kangelaris MD/MAS & Shradha A. Kulkarni MD

Tiffany Lee MA

The University of Texas at Austin, Dell Medical School, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX, USA

Luci K. Leykum MD/MBA/MSc

Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital/Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Anne S. Linker MD

Section of Hospital Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA

Devin T. Worster MD MPH

Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

Marisha Burden MD

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angela Keniston MSPH .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 83 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Keniston, A., Sakumoto, M., Astik, G.J. et al. Adaptability on Shifting Ground: a Rapid Qualitative Assessment of Multi-institutional Inpatient Surge Planning and Workforce Deployment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J GEN INTERN MED 37 , 3956–3964 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07480-x

Download citation

Received : 13 October 2021

Accepted : 03 March 2022

Published : 22 March 2022

Issue Date : November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07480-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- hospital medicine

- workforce planning

- surge planning

- focus groups

- qualitative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 02 July 2021

Rapid versus traditional qualitative analysis using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

- Andrea L. Nevedal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3859-8493 1 na1 ,

- Caitlin M. Reardon 2 na1 ,

- Marilla A. Opra Widerquist 2 ,

- George L. Jackson 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ,

- Sarah L. Cutrona 7 , 8 , 9 ,

- Brandolyn S. White 3 &

- Laura J. Damschroder 2

Implementation Science volume 16 , Article number: 67 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

140 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative approaches, alone or in mixed methods, are prominent within implementation science. However, traditional qualitative approaches are resource intensive, which has led to the development of rapid qualitative approaches. Published rapid approaches are often inductive in nature and rely on transcripts of interviews. We describe a deductive rapid analysis approach using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) that uses notes and audio recordings. This paper compares our rapid versus traditional deductive CFIR approach.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted for two cohorts of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Diffusion of Excellence (DoE). The CFIR guided data collection and analysis. In cohort A, we used our traditional CFIR-based deductive analysis approach (directed content analysis), where two analysts completed independent in-depth manual coding of interview transcripts using qualitative software. In cohort B, we used our new rapid CFIR-based deductive analysis approach (directed content analysis), where the primary analyst wrote detailed notes during interviews and immediately “coded” notes into a MS Excel CFIR construct by facility matrix; a secondary analyst then listened to audio recordings and edited the matrix. We tracked time for our traditional and rapid deductive CFIR approaches using a spreadsheet and captured transcription costs from invoices. We retrospectively compared our approaches in terms of effectiveness and rigor.

Cohorts A and B were similar in terms of the amount of data collected. However, our rapid deductive CFIR approach required 409.5 analyst hours compared to 683 h during the traditional deductive CFIR approach. The rapid deductive approach eliminated $7250 in transcription costs. The facility-level analysis phase provided the greatest savings: 14 h/facility for the traditional analysis versus 3.92 h/facility for the rapid analysis. Data interpretation required the same number of hours for both approaches.

Our rapid deductive CFIR approach was less time intensive and eliminated transcription costs, yet effective in meeting evaluation objectives and establishing rigor. Researchers should consider the following when employing our approach: (1) team expertise in the CFIR and qualitative methods, (2) level of detail needed to meet project aims, (3) mode of data to analyze, and (4) advantages and disadvantages of using the CFIR.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Published rapid qualitative analysis approaches often use transcripts; our approach shows how notes and verification with audio recordings can be used to ensure rigor while saving time and eliminating transcription costs.

Published rapid qualitative analysis approaches often utilize inductive approaches; our approach shows how to conduct deductive rapid analysis using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which allows researchers to compare results more easily across studies.

CFIR users have expressed difficulty using the framework because our traditional analysis approach is resource intensive; the rapid analysis approach described here may facilitate the use of the CFIR for experienced users.

Qualitative methods are invaluable for gathering in-depth information about “how and why efforts” to implement Evidence-Based Innovations (EBIs) succeed or fail [ 1 ]. As a result, qualitative approaches (alone or within mixed methods) are foundational for implementation scientists seeking to identify and understand factors that help or hinder the implementation and use of EBIs in real-world settings [ 2 , 3 ]. Traditional qualitative approaches, however, are resource intensive, which challenges constrained study timelines and budgets. This is especially problematic in studies where scientists need real-time data to inform the process of implementation [ 4 ].

Consequently, qualitative researchers are working to develop methods that balance rigor and efficiency. The need for this balance is particularly salient in healthcare, where treatments and interventions are rapidly evolving, and evaluations of such interventions are constrained by limited timelines, funding, and staffing [ 5 ]. As a result, rapid assessment, which often involves streamlined processes for qualitative data collection and analysis, is gaining increased attention as a way to support quicker implementation and dissemination of EBIs to reduce delays in translating clinical research into practice [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

An important element of rapid assessment is rapid qualitative analysis, which is the focus of this paper. Traditionally, qualitative analysis approaches have been resource intensive and occur over a longer timeframe; they include, but are not limited to, constant comparison, content, discourse, or thematic analysis [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Many traditional qualitative analysis approaches include in-depth manual coding of transcripts using software programs. In contrast, rapid qualitative analysis is deliberately streamlined and designed to be less resource intensive in order to meet a shorter timeframe [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Rapid qualitative analysis may involve eliminating transcription altogether or speeding up transcription processes [ 19 ] and then summarizing data into post-interview notes, templates based on the interview guide, and/or matrix summaries rather than in-depth manual coding of transcripts [ 9 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Though rapid analysis is not wedded to a particular approach (e.g., content or thematic), some traditional qualitative analysis approaches may be more difficult to streamline. Rapid qualitative analysis is crucial when results are needed to quickly develop or modify implementation strategies and/or inform stakeholders or operational partners [ 5 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 19 ]. Rapid qualitative analysis is also useful during longitudinal implementation research since data points can become unwieldy, and results may be needed to inform future waves of data collection [ 22 ].

Hamilton developed a rapid qualitative analysis approach that summarizes transcript data into templates using domains aligned with interview questions; summary points are then distilled into a matrix organized by domain and participant for analysis and interpretation [ 18 ]. Gale et al. adapted this rapid approach in a process evaluation of academic detailing and compared it with a traditional analysis approach [ 23 ]. Their rapid approach involved summarizing transcripts into a template and then mapping themes onto the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a determinant framework that defines constructs across five domains of potential influences on implementation [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Gale et al. demonstrated consistency between results from rapid qualitative analysis versus traditional qualitative analysis. The traditional approach, however, “took considerably (69 days) longer than the rapid analysis to complete” [ 23 ]. Similarly, Holdsworth et al. noted that their modified version of rapid qualitative analysis “produced contextually-rich information” and can be used to save “days and weeks of costly transcription and analysis time” [ 27 ]. Except for Taylor et al.’s [ 20 ] comparison of rapid and thematic analysis, most rapid analysis literature focuses on daily duration and does not quantify reductions in analyst hours and costs at the activity level versus the project overall.

The rapid approaches described by Hamilton and Gale et al. rely on verbatim transcripts, which means teams must wait for transcription to be completed to proceed with rapid or traditional analyses. In contrast, Neal et al. [ 28 ] developed an approach to rapidly identify themes directly from audio recordings. However, Gale et al. [ 23 ] noted that because this approach relies on general domains, rather than framework informed codes, it “limits one’s ability to compare findings across projects unless findings are [subsequently] mapped to a framework.” As implementation scientists using the CFIR to guide our evaluations, we sought to build on prior rapid analysis approaches by developing a CFIR informed deductive rapid analysis process using notes and audio recordings. The objective of this article is to compare two different qualitative analysis processes using the CFIR: a traditional deductive approach using transcripts and a rapid deductive approach using notes and audio recordings.

Evaluation background

We conducted a mixed-methods evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Diffusion of Excellence (DoE), which seeks to identify and diffuse EBIs. These EBIs include innovations supported by evidence from research studies and administrative or clinical experience [ 29 , 30 ] and strive to address patient, staff, and/or facility needs. The DoE hosts an annual “Shark Tank” competition, in which VHA leaders compete to implement an EBI with 6 months of external implementation support; for additional detail, see previous publications [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. As part of a national evaluation of the DoE, we identified barriers and facilitators to the implementation of these EBIs in VHA facilities using semi-structured interviews [ 31 ]. The qualitative interview and analysis team included CR (MPH, a senior qualitative analyst and CFIR expert user) and AN (PhD, a senior qualitative methodologist and CFIR intermediate user). Per regulations outlined in VHA Program Guide 1200.21, this evaluation has been designated a non-research quality improvement activity.

Methods for the traditional and rapid approaches

Data collection: semi-structured interviews.

Data collection methods were the same across both approaches; in effect, they will not be discussed in detail in this paper. In brief, we conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with DoE participants involved with implementing an EBI; for additional detail, see previous publications [ 31 , 35 ]. Interview guides were informed by the CFIR (see Additional File 1 ). Cohort A included 57 interviews across 17 facilities (1–4 interviews/facility) from June 2017 to September 2017; because one facility only had one interview, the need to aggregate data for that facility was eliminated. Cohort B included 72 interviews across 16 facilities (3–6 interviews/facility) from May 2019 to September 2019. Although cohort B included more interviews, the interviews were on average shorter (approximately 30 min), so both cohorts had approximately 50 audio hours total.

Data analysis: traditional and rapid approaches

The steps in our CFIR-based deductive traditional and deductive rapid qualitative analysis approaches are described in Table 1 . The traditional CFIR approach is described in detail on www.cfirguide.org and in several publications [ 31 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Our traditional CFIR approach is a form of directed content analysis [ 11 ] using transcripts and consisted of the following steps:

The analysts independently coded verbatim transcripts using Dedoose [ 39 ], a collaborative qualitative software program. The codebook included deductive CFIR constructs as well as inductive codes not captured in the CFIR that were relevant to the evaluation. Analysts used comments within coding software to flag sections of text for discussion or add additional notes.

The analysts met weekly to adjudicate differences in coding.

The primary analyst exported and aggregated coded data in MS Word CFIR facility memos (one for each facility). See Table 2 and Additional File 2 .

The primary analyst summarized and rated coded data and wrote high-level facility summaries in each facility memo. The secondary analyst reviewed the primary analyst’s drafts of the facility memos and edited the summaries, ratings, and high-level facility summaries. Ratings were based on two factors: (1) valence (positive or negative influence on implementation) and (2) strength (weak or strong influence on implementation). Analysts used comments and highlighting in the facility memo to flag sections of text for discussion. Completed facility memos ranged from 68 to 148 pages with an average of 108 pages.

The analysts met weekly to adjudicate differences and refine the codebook.

The primary analyst copied the summaries, ratings, and high-level facility summaries from each facility memo into the MS Excel CFIR construct by facility matrix for interpretation; the matrix included all codes from the codebook (both deductive and inductive codes) as well as a row for high-level facility summaries. See Table 3 and Additional File 3 .

In contrast, our rapid CFIR approach is a form of directed content analysis [ 11 ] using interview notes and verification with audio recordings, which consisted of the following steps:

The primary analyst took notes and captured quotations during interviews. Immediately after the interviews, the primary analyst “coded” the notes into the MS Excel CFIR construct by facility matrix and noted when additional detail or a timestamp was needed. The secondary analyst then reviewed the matrix, listened to the audio recordings, and edited and built upon the primary analyst’s notes. Analysts coded based on a codebook with deductive CFIR constructs as well as inductive codes not captured in the CFIR that were relevant to the evaluation. Analysts used comments and highlighting in the matrix to flag sections of text for discussion.

Analysts met weekly to adjudicate differences and refine the codebook.

The primary analyst reviewed notes, rated CFIR constructs, and wrote a high-level facility summary for each facility in the matrix; the secondary analyst reviewed the matrix and edited ratings and high-level facility summaries. Ratings were determined based on two factors: (1) valence (positive or negative influence on implementation) and (2) strength (weak or strong influence on implementation). See Table 3 and Additional File 3 .

Analysts met weekly to adjudicate differences.

Data interpretation: facility and construct analyses

Data interpretation methods were the same across both approaches and are discussed in detail on www.cfirguide.org . In brief, the analysts completed the following steps: (1) facility (case) analyses, to identify constructs that influenced implementation outcomes in each facility, and (2) construct analyses, to identify CFIR constructs that manifested positively or negatively across facilities or distinguished between facilities with high and low implementation success.

Methods for comparing traditional and rapid approaches

Comparing time and transcription costs.

The team tracked time for data management, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation for both approaches using MS Excel spreadsheets. Staff time for these tasks is based on hours. We also combined both analyst’s funded effort to determine the total available analyst hours for our evaluation. Transcription costs were obtained from invoices from a centralized VHA qualitative interview transcription service.

Comparing effectiveness and rigor

The team did not plan to compare the effectiveness or rigor of our traditional versus rapid approach (see the “Limitations” section). As a result, we defined and assessed these aspects retrospectively. Effectiveness was measured by whether we met our evaluation objective in each approach. Rigor was measured primarily by assessing the credibility of each approach, i.e., if evaluation processes established confidence that the results were accurate [ 40 , 41 ].

Comparing traditional and rapid approaches

Time and transcription costs.

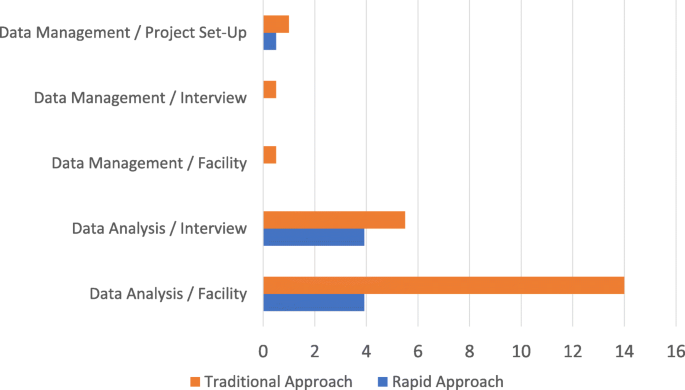

The traditional approach required more time than the rapid approach and included transcription costs. Cohort A, using the traditional deductive CFIR approach, required 683 total hours and $7250 in transcription costs. Cohort B, using the rapid deductive CFIR approach, required 409.5 total hours with no transcription costs. In effect, the rapid approach required 273.5 fewer total hours and saved $7250 in transcription costs. The evaluation funded two analysts with a combined total of 1305 h available for each year. Cohort A required 52.3% (683/1305 h) of the available hours while cohort B required 31.4% (409.5/1305 h) of the available hours, representing a significant reduction in time within the broader context of the evaluation. However, time savings during rapid analysis varied by phase, with the largest savings during the facility-level analysis. The following sections provide a summary of analyst hours and transcription costs for both approaches. See Table 1 , Table 4 , and Fig. 1 for additional description.

Comparison of analysis hours for the Traditional CFIR Approach (Cohort A) versus the Rapid CFIR Approach (Cohort B). This graph does not include data collection or data interpretation because both were equal across Cohort A and B

Data management

Data management in the traditional approach required 1 h to set-up the project and .5 h/interview plus .5 h/facility. In contrast, data management in the rapid approach required only .5 h to set-up the project with no other time needed. As shown in Table 1 , the rapid approach eliminated data management steps except for creating the MS Excel CFIR construct by facility template. As a result, the rapid approach reduced analys time by 33.5 h. Though not directly impacting analyst hours, transcripts were not received for 2–6 weeks following interviews, significantly delaying analysis for the traditional approach. See Table 1 , Table 4 , and Fig. 1 .

Data collection methods were the same across both approaches and the total number of audio hours was roughly equivalent between cohorts A and B; in effect, there were no significant differences in analyst hours between approaches. However, the rapid approach required blocking approximately 3 h for each interview: approximately 1 h for the interview plus 1–2 h to process the notes and “code” them into the CFIR construct by facility matrix immediately following the interview. The analyst’s immediate recall of the interview helped bolster the accuracy of the notes but intensified effort and cognitive load on interview days.

Data analysis

Data analysis in the traditional approach required 5.5 h/interview plus 14 h/facility versus 3.92 h/interview plus 3.92 h/facility in the rapid approach. In effect, the rapid approach reduced analys time by 79 h (275 versus 196 for traditional and rapid, respectively). The largest contributor to this reduction in analyst hours was in the facility-level analysis phase; where the rapid approach required 63 h, the traditional approach required 224 h. This difference was a result of how and when data were condensed and aggregated. In the traditional deductive CFIR approach, all coded data were aggregated in facility memos that were approximately 108 pages long; due to the relationships that often exist between constructs, the memos often included the same segments of text under multiple constructs. As a result, the same pieces of data were reviewed multiple times in full by each analyst independently before the data were condensed in the matrix. In contrast, the rapid deductive CFIR approach condensed data prior to aggregating by facility and was completed first by the primary analyst. Relationships between constructs were described once in the matrix, and notes in other cells referred back to this description, thus eliminating multiple references to the same data. The secondary analyst then built upon and confirmed the data in the matrix by listening to the audio recording. See Table 1 , Table 4 , and Fig. 1 .

Data interpretation

Data interpretation methods were the same across both approaches, which consisted of reviewing the CFIR construct by facility matrix. Both approaches took approximately 100 h for data interpretation. See Table 1 , Table 4 , and Fig. 1 .

Effectiveness and rigor

There were substantial differences in the number of hours and transcription costs between the traditional and rapid approaches; however, both approaches were systematic and there was concordance among many of the evaluation phases. Even when the analysis steps were different, both approaches followed the same general approach from data collection through data interpretation (see Table 1 ). Although data werecondensed earlier in the rapid approach than the traditional approach, i.e., following the interview versus following the facility memo, the depth of the data in the final matrices was similar for both approaches. For example, both matrices included brief direct quotes from participants. As a result, both approaches were effective in meeting our overall goal for the evaluation; we were able to identify and describe the factors influencing implementation in a high level of detail. However, the rapid approach also allowed us to share formal results more quickly with our operational partners (see Table 5 ).

In addition, both approaches included processes to enhance methodological rigor [ 40 , 41 ]. Credibility of results, a form of rigor, was most relevant when assessing tradeoffs between our rapid and traditional approaches [ 41 ]. We enhanced the credibility of results by having analysts with expertise in qualitative methods and the CFIR. To ensure participant responses were accurately captured in our summaries, we used two analysts per interview as a quality check and verified summaries with raw data (transcripts or audio recordings). Overall, the final summaries from both approaches were quite similar. See Table 5 for an additional description of the effectiveness and concordance of rigor between both approaches.

Our rapid deductive CFIR approach has much potential value, given the urgent need for nearly real-time results, to guide the implementation and dissemination of EBIs. The goal of this paper was to compare two qualitative approaches using deductively derived codes based on the CFIR: a traditional deductive CFIR approach using verbatim transcripts versus a rapid deductive CFIR approach using notes and audio recordings. Although we used the CFIR, this approach can be used with other frameworks. Our paper enhances the literature by describing exactly how rapid deductive CFIR analysis versus traditional deductive CFIR analysis leads to less resource use without compromising rigor.

Although our rapid deductive CFIR approach was beneficial for our evaluation team, researchers should review four considerations before using this method: (1) team expertise in CFIR and qualitative methods, (2) level of detail needed to meet project aims, (3) mode of data to analyze, and (4) advantages and disadvantages of using the CFIR.

First, the team’s expertise in the CFIR and qualitative methods should be considered before deciding to employ a rapid approach. Prior literature suggests that traditional qualitative analysis requires more intense training than rapid analysis [ 23 , 28 ]. In-depth qualitative methods should indeed be conducted by a skilled research team. However, we argue that our rapid deductive CFIR approach may be more suited to researchers who already have a strong foundation in qualitative methods and the CFIR. Qualitative researchers familiar with the CFIR are more equipped to rapidly “code” qualitative data into CFIR constructs in real time than a novice. However, even for skilled researchers, we found that rapid analysis intensified effort and cognitive load during the initial coding phase, e.g., requiring a 3-h calendar block. Although a more experienced team may cost more in terms of salaries, the experienced team works more efficiently and likely saves money overall by reducing time spent training and overseeing project staff. For less experienced teams, we suggest linking CFIR constructs and brief definitions directly to interview questions within a notes template; this will help guide the researcher when summarizing the interview and/or listening to the audio recording. However, it is important to note that participant responses to questions will not always address the intended construct. Furthermore, while we identified a high level of fidelity between the primary analyst’s notes and the audio recordings, the secondary analyst may serve as an essential quality check for less experienced teams.

Second, researchers should consider what level of detail is needed for data analysis and the presentation of results in order to meet the project’s aims [ 28 ]. As articulated in prior research, rapid approaches using notes and audio recordings may provide a “big picture” view, yielding a lower level of detail than transcript-based approaches [ 28 ]. A project that requires a high level of detail and/or long quotations may therefore not be appropriate for our rapid approach. Our rapid CFIR approach provided less detail, but in so doing, may have allowed us to see both the overall patterns and the important details in our data more efficiently, i.e., seeing both the forest and the trees.

Third, the mode of data (transcripts or audio recordings) should be considered since it is not necessarily associated with a traditional or rapid approach. For example, audio recordings can be used for traditional analysis, i.e., many types of qualitative software allow minute-by-minute coding of audio recordings, and transcripts can be used for rapid analysis, i.e., summaries can be developed based on transcripts instead of audio recordings. For our rapid approach, we chose to use post-interview notes and audio recordings instead of transcripts to help streamline our deductive CFIR analysis process, i.e., it eliminated transcription costs and delays, and provided a point of comparison with other existing rapid approaches that use transcripts. However, if a team desires a more rapid approach while also maintaining access to the data in written form, including transcripts may be an option.

Fourth, there are advantages and disadvantages to consider when opting to use the CFIR (or another framework) regardless of the rapid or traditional qualitative analysis approach. Using the CFIR is helpful because it is a comprehensive determinant framework that includes constructs from 19 other models, including work by Greenhalgh et al. [ 42 ] that reviewed 500 published sources across 13 scientific disciplines. In effect, the CFIR helps researchers identify determinants that may be overlooked in a purely inductive approach. In addition, the use of the CFIR assists researchers with sharing and comparing results across studies, which advances implementation science. However, if researchers overly rely on the CFIR (or another framework), they may overlook constructs or miss important insights not included in the framework. To address this concern, we included questions in our interview guide beyond the scope of the CFIR, e.g., anticipated sustainment, and added codes, as needed, to capture inductively derived determinants and outcomes. Overall, even when using a more deductive approach, it is important for researchers to be open to inductive topics or domains that may arise in the data. Ultimately, researchers should consider their goals when deciding whether to adopt a deductive rapid approach (i.e., more confirmatory to compare with existing constructs or knowledge) versus an inductive approach (i.e., more exploratory to generate new constructs or knowledge).

It is important to note that our rapid deductive CFIR approach was still time intensive; it took 409.5 h to complete the analysis, including the rating process, for cohort B. However, because the analysts completed interview notes and coding in the matrix immediately after each interview, we were able to share preliminary results during regularly scheduled meetings with our operational partners on an ongoing basis. Regardless, some researchers may need additional ways to streamline our rapid CFIR analysis process. As long as a team considers both strengths and limitations, the following strategies may provide ways to streamline our rapid CFIR approach:

The team could eliminate the second analyst entirely or only use a second analyst on a subset of interviews, e.g., on the first 10 interviews or a random sample.

The team could include only the CFIR constructs expected to be most relevant to the research question in the matrix.

The team could seek to obtain project artifacts, e.g., meeting minutes, to analyze in the place of interviews.

The team could omit the rating process following coding.

Although rapid approaches are becoming more alluring to many implementation science researchers, they should not be considered a quick and easy replacement for traditional approaches or a substitute for having a skilled research team. Teams must carefully consider the best approach for their project while also exploring how to maintain scientific rigor. Qualitative expert oversight and/or training, analyst familiarity with the framework, review by a secondary analyst, and interview data quality are some important aspects of methodological rigor.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, both analysts on this project were intermediate to expert CFIR users. Our approach may be more difficult for new CFIR users, i.e., it may be difficult to translate interview notes into “coded” data in the matrix or to “code” while listening to an audio recording, unless the researchers are very familiar with the constructs. Second, the same analysts were involved in analyzing both cohorts. It is possible the analysts were more familiar with the broader findings from the study based on the traditional analysis of cohort A, which may have allowed them to progress more quickly in the rapid analysis of cohort B. However, using the same analysts improves comparability of coding between the two different cohorts of data and streamlined the process because additional analysts did not need to be trained in using the CFIR. Future research is needed to assess the extent and the conditions under which our approach works for other CFIR users. Third, we focused on differences in time and transcription costs rather than specifically testing the effectiveness or rigor of our rapid versus traditional approach, which has been discussed in prior literature [ 23 , 28 ]. While the rigor of the results was the same with both approaches, future researchers should likewise assess the rigor of this deductive rapid approach within their circumstances.

Conclusions