Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

In the Media

Prof. Christopher Magee and his colleagues have developed a new method that could help provide insights into how quickly different innovations are improving, reports Christopher Mims for The Wall Street Journal . Magee and former MIT fellow Anuraag Singh have developed a search engine that allows users to “answer in a fraction of a second the question of how quickly any given technology is advancing,” writes Mims.

Related Topics

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E)

- Computer science and technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- External Advisory Board

- Visiting Committee

- Jobs & Grants

- Senior Research Staff

- Research Staff

- Graduate Students

- Administrative Staff

- Our Approach

- Collaborations

- Research Domains

- Labs and Centers

- PhD Program in Social & Engineering Systems

- Technology and Policy Program

- Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in Statistics

- Minor in Statistics and Data Science

- IDSSx: Data Science Online

- MicroMasters Program in Statistics and Data Science (SDS)

- IDSS Classes

- IDSS Student Council

- Newsletters

- Podcast: Data Nation

- Past Events

- IDSS Alliance

- IDSS Strategic Partnerships

- Invest in IDSS

News & Events

New Research Busts Popular Myths About Innovation

MIT Institute for Data, Systems, and Society Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 617-253-1764

- Accessibility

- Initiative on Combatting Systemic Racism

- IDSS COVID-19 Collaboration (Isolat)

- Energy Systems

- Health Care

- Social Networks

- Urban Systems

- SES Admissions

- SES Program and Resources

- SES Funding

- SES + Statistics

- SES Graduates

- Data Science and Machine Learning: Making Data-Driven Decisions

- Online Programs and Short Courses

- Conferences and Workshops

- IDSS Distinguished Seminar Series

- IDSS Special Seminars

- Stochastics and Statistics Seminar Series

- Research to Policy Engagement

- IDS.190 – Topics in Bayesian Modeling and Computation

- Online Events

- Other Events

- Great Learning

- Partnerships in Education

- Partnerships in Research

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

The 5 Myths of Innovation

Nowadays, goes the theory, innovation is supposed to be done constantly, by everyone in the company, improving everything the company is about — and new Web-based tools are here to help it happen. Is the theory right? Or do the experiences of companies reveal something different?

- Innovation Strategy

Image courtesy of Flickr user rishibando.

Historically, most managers equated innovation primarily with the development of new products and new technologies. But increasingly, innovation is seen as applying to the development of new service offerings, business models, pricing plans and routes to market, as well as new management practices. There is now a greater recognition that novel ideas can transform any part of the value chain — and that products and services represent just the tip of the innovation iceberg. 1

This shift of focus has implications for who “owns” innovation. It used to be the preserve of a select band of employees — be they designers, engineers or scientists — whose responsibility it was to generate and pursue new ideas, often in a separate location. But increasingly, innovation has come to be seen as the responsibility of the entire organization. For many large companies, in fact, the new imperative is to view innovation as an “all the time, everywhere” capability that harnesses the skills and imagination of employees at all levels. 2

Making innovation everyone’s job is intuitively appealing but very hard to achieve. Many companies have put in place suggestions, schemes, ideation programs, venturing units and online forums. (See “A Glossary of Established Drivers of Innovation.”) However, the success rate of such approaches is mixed. Employees face capacity, time and motivation issues around their participation. There is often a lack of follow-through in well-intentioned schemes. And there is typically some level of disconnect between the priorities of those at the top and the efforts of those lower down in the organization.

The Leading Question

What conventional wisdom about innovation no longer applies?

- Online forums are not a panacea for innovation.

- Innovation shouldn’t always be “open.” Internal and external experts should be used for very different problems.

- Innovation must be bottom-up and top-down — in an approach that’s balanced.

Moreover, Web-based tools for capturing and developing ideas have not yet delivered on their promise: A recent McKinsey survey revealed that the number of respondents who are satisfied overall with the Web 2.0 tools (21%) is slightly outweighed by the number who voice clear dissatisfaction (22%). 3

To understand these challenges, and to identify the innovation practices that work, we spent three years studying the process of innovation in 13 global companies. (See “About the Research.”) All of these companies embarked on often-lengthy journeys aimed at making themselves more consistently and sustainably innovative. All sought to engage their employees in the process, and all made use of online tools to facilitate and improve the quality and quantity of ideas. Our research allowed us to confirm many of the standard arguments for how to encourage innovation in large organizations, but we also uncovered some surprising findings. (See “Questions That Work — and Don’t — in Online Innovation Forums” for a summary.) In this article we focus on the key insights that emerged from our research, organized around five persistent “myths” that continue to haunt the innovation efforts of many companies.

Myth # 1. The Eureka Moment

For many people, it is still the sudden flash of insight — think Archimedes in his bath or Newton below the apple tree — that defines the process of innovation. According to this view, companies need to hire a bunch of insightful and contrarian thinkers, and provide them with a fertile environment, and lots of time and space, to come up with bright ideas.

A Glossary of Established Drivers of Innovation >>

A Glossary of Established Drivers of Innovation

There is a growing body of work on the leading-edge practices in innovation management. Consultants and scholars concur on a number of proven conditions that contribute to sustained innovation. i These include:

Shared understanding: Sustained innovation is a collective endeavor built on a shared sense of what the company is becoming — and what it is not becoming. It is also about creating a culture to support innovation — for example, by destigmatizing failure and celebrating successes.

Alignment: Besides promoting values that support innovation, organizations also have to address structural impediments (such as silos) and realign contradictory systems and processes. As the group head of innovation in one company told us, “We needed to create an environment where it was ‘safe to experiment’; where it was possible to ‘pilot’ and ‘test’ ideas before they were subjected to our stringent performance metrics.”

Tools: Employees need the training, concepts and techniques to innovate. In the memorable words of a decision support manager at 3M, “It doesn’t work to urge people to think outside the box without giving them the tools to climb out.” ii

Diversity: Innovation requires a degree of friction. Bringing in outsiders — new hires, experts, suppliers or customers — and mixing people across business units, functions and geographies helps spark new ideas.

Interaction: Organizations need to establish forums, platforms and events to help employees build networks and to provide opportunities for exchange and serendipity to happen.

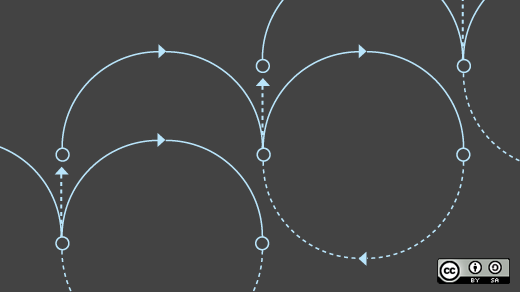

Alas, the truth is far more prosaic. It is often said that innovation is 5% inspiration and 95% perspiration, and our research bears this out. If you think of innovation as a chain of linked activities — from generating new ideas through to commercializing them successfully — it is the latter stages of the process where ideas are being worked up and developed in detail that are the most time consuming. 4 Moreover, it is also the latter stages where problems occur. We recently conducted a survey in 123 companies, asking managers to evaluate how effective they were at each stage in the innovation value chain. On average, they indicated that they were relatively good at generating new ideas (either from inside or outside the boundaries of the company), but their performance dropped for every successive stage of the chain. (See “Which Parts of the Innovation Value Chain Are Companies Good At?”) We are not suggesting that generating ideas is unimportant. But that is not where most companies struggle. Most companies are sufficiently good at generating ideas; the “bottleneck” in the innovation process actually occurs a lot further down the pipeline.

The eureka myth helps explains why so many companies are drawn to big brainstorming events, with names such as ideation workshops and innovation jams. 5 In the course of our research we saw many different types of brainstorming events, and indeed we helped several of the sample companies to put them on. Such events are always valuable: They help to focus the efforts of a large number of people, they generate excitement and interest and they generate some useful ideas.

About the Research >>

About the Research

Our research was conducted over a three-year period in cooperation with a group of leading companies. The participants came from various sectors: consumer products (Mars, Sara Lee, Best Buy, Whirlpool), pharmaceuticals (Roche Diagnostics, GSK), broadcasting (BBC), energy (BP), information and communication technology (BT, IBM), business information (ThomsonReuters) — as well as two banks that were at the center of the recent financial crisis (UBS and RBS). We could have excluded them from the study, but they faced distinctive challenges that significantly enriched the study. We interviewed a total of 54 people, some of them several times, in these companies, and we wrote up detailed case studies about six of the companies (Mars, Roche, GSK, IBM, BT and UBS).

Apart from tracking and reporting on their innovation efforts, some of the participant companies also came together for a roundtable conference at London Business School in December 2008. This provided a fascinating window on the challenges of implementing an innovation strategy in large organizations, and it allowed us to test out some of our provisional ideas.

But even with all these benefits, it’s not clear that ideation workshops are the right way to build companywide innovation capability. As an analogy, think of the role that big musical festivals like Live Aid play in the alleviation of poverty. These big events are terrific for raising awareness and money on a one-time basis, but the process of poverty alleviation takes years of hard effort on the part of aid organizations, and the outcomes are achieved long after the memory of the big event has faded. The involvement of the general public in aid work usually ends with the check we write to Live Aid; but for the aid organization receiving the money, that is where the real work starts.

Our research showed that most companies fail to think through the consequences of putting on ideation workshops. The first problem is that they underestimate the amount of work that is needed after the workshop is completed. IBM’s 2006 online Innovation Jam, described in more detail below, required a team of 60 researchers to sort through the 30,000 posts received over a 72-hour period. UBS Investment Bank’s Idea Exchange, while conducted on a smaller scale, also involved a great deal of post-event work. As one UBS manager observed: “Preliminary sorting, then scoring and giving feedback on such a large number of ideas took a huge amount of time and effort by category owners and subject matter experts. The ideas coming through were good, but if we are to do it again we need a repeatable, dashboard-style reporting system for quantifying results and keeping the momentum going.”

Questions That Work — and Don’t — in Online Innovation Forums >>

Questions That Work — and Don’t — in Online Innovation Forums

- Which of the following sources of information do you use most frequently in the workplace? (print media, digital media, experts, colleagues)

- How would you rate our speed of customer responsiveness on a one-10 scale?

- Can anyone tell me what to do when I am faced with this error code? Syntax Loop unspecified Ref 56663.

What doesn’t

- We are looking for radical new approaches to customer service in our retail bank — any ideas?

Advice: Provide some unusual stimuli to encourage people to think differently, for example: How could we make the retail bank more like your favorite restaurant?

- Let’s start a discussion thread about new approaches to working more closely with our customers.

Advice: Use a mix of online and in-person brainstorming sessions; or actively manage the thread to create some coherence.

The second, and more insidious, problem with ideation workshops is that they can actually be disempowering if the organization lacks the capacity to act on the ideas generated. We heard quite a few grumbles during the research from individuals who had put forward their bright ideas through a workshop or online forum, but received no response — not even an acknowledgment. If the “funnel” is constricted further down, at the point where ideas get assessed and developed, stuffing new ideas at the top is simply going to exacerbate the problem.

So what should you do? First, be very clear what problem you are trying to solve, and put on an ideation workshop only if you believe that it is a lack of ideas that is holding you back. Second, if you believe that an ideation workshop is the right approach, be prepared to invest a lot of time and effort into the follow-up work. It is sobering to note that successful innovation programs typically take many years to bear fruit: Procter & Gamble’s Connect + Develop initiative was piloted and developed over a 10-year period, while Royal Dutch Shell’s Gamechanger initiative took more than five years to yield benefits. Alas, many companies lack the continuity in leadership needed to make this type of long-term commitment.

Takeaway: Most innovation efforts fail not because of a lack of bright ideas, but because of a lack of careful and thoughtful follow-up. Smart companies know where the weakest links in their entire innovation value chain are, and they invest time in correcting those weaknesses rather than further reinforcing their strengths.

Myth # 2. Build It and They Will Come

The emergence of second-generation Internet technologies (“Web 2.0”) has had a dramatic impact on how we share, aggregate and interpret information. The proliferation and growth of online communities such as Facebook and LinkedIn seduce us into assuming that these new means of social interaction will also transform the way we get things done at work.

But for every online community that succeeds, many others fail. Some make a good start but then enthusiasm wanes. For example, MyFootballClub is a U.K.-based website whose 30,000 members bought a soccer club, Ebbsfleet United, in 2007. However, by 2010 its paying membership had dwindled to just 800 people, leading to severe financial difficulties for Ebbsfleet United. Other online community initiatives fail to live up to their founders’ hopes. For example, during the transition period before he came into office, President Obama endorsed the idea of an online “Citizen’s Briefing Book” for people to submit ideas to him. Some 44,000 proposals and 1.4 million votes were received, but as the International Herald Tribune reported, “the results were quietly published, but they were embarrassing.” 6 The most popular ideas — in the middle of an economic meltdown — included legalizing marijuana and online poker, and revoking the Church of Scientology’s tax-exempt status.

How does this affect the process of innovation? Unsurprisingly, all the companies we studied had figured out that the tools of Web 2.0 could potentially be very valuable in helping large numbers of people get involved in an innovation process. Most had built some sort of online forum in which employees could post their ideas, comment and build on the ideas of others and evaluate proposals. For example, IBM used space on its corporate Intranet to launch a 72-hour Innovation Jam in 2006, the purpose being to get IBM employees, clients and partners involved in an online debate about new business opportunities. The Innovation Jam attracted 57,000 visitors and 30,000 posts. A rather different example is Royal Bank of Scotland’s development of a virtual innovation center in Second Life, which allowed the bank to prototype potential new banking environments and get direct and rapid feedback from employees around the world.

In these and other cases, the implicit logic was: Build it, and they will come. Both IBM and RBS had considerable success in attracting interest, but the overall story was much more mixed. Some online forums really helped to galvanize their company’s innovation efforts. Others ended up underused and unloved.

What are the biggest problems with developing online innovation forums? The first is that the forum doesn’t take off. It’s usually quite straightforward to get people to check out a new site once or twice, but they need a reason to keep coming back. As MyFootballClub found, the risk is that the novelty of an innovation forum will wear out pretty quickly and participation will dwindle. A manager at Roche Diagnostics observed: “Our hope that our internal technology-oriented people would gravitate to using this type of tool was completely unfounded. We really had to push people (via an electronic marketing campaign) to involve them in suggesting solutions to the six problems we identified.” Equally, managers at Mars and UBS found their innovation efforts stalling after promising starts. One said: “We probably underestimated the communications needed. We were good up-front, but learned that continuous communications is vital. We had to counter some skepticism, to create the belief that something would happen.”

The second risk is that, like Obama’s Citizen’s Briefing Book, the ideas that get posted are off-topic, half-baked or irrelevant. All the managers we spoke to acknowledged that they had to work hard to “separate the wheat from the chaff.” Many of the ideas put forward were parochial or ill-informed, and few people took the trouble to build on the ideas of others. The notion that the good ideas would be picked up by others and rise to the top rarely worked out.

So what should you do to avoid these problems? The most important point is to understand the types of interaction that occur in online forums, so that you use them in the right way. If you are looking for creative, never-heard-before ideas, and if you want people to take responsibility for building on one another’s ideas, then a face-to-face workshop is your best bet. But if you are looking for a specific answer to a question, or if you want to generate a wide variety of views about some existing ideas, then an online forum can be highly efficient. (See “Questions That Work — and Don’t — in Online Innovation Forums” for examples.)

Takeaway: Online forums are not a panacea for distributed innovation. Online forums are good for capturing and filtering large numbers of existing ideas; in-person forums are good for generating and building on new ideas. Smart companies are selective in their use of online forums for innovation.

Myth # 3. Open Innovation Is the Future

Any discussion of innovation in large companies sooner or later turns to the issue of “open” innovation — the idea that companies should look for ways of tapping into and harnessing the ideas that lie beyond their formal boundaries. Many companies are now embracing open innovation in its many guises. For example, the Danish toymaker LEGO has been leveraging customer ideas as a source of innovation for years, and some new products are even labeled “created by LEGO fans.” 7 And one of P&G’s first experiments with online advertising invited people to make spoof movies of P&G’s “Talking Stain” TV ad and post them on YouTube — resulting in over 200 submissions, some of which proved good enough to air on TV. 8

Our research confirmed that most large companies believe a more open approach to innovation is necessary, but it also underlined that there is no free lunch on offer. The benefits of open innovation, in terms of providing a company with access to a vastly greater pool of ideas, are obvious. But the costs are also considerable, including practical challenges in resolving intellectual property ownership issues, lack of trust on both sides of the fence and the operational costs involved in building an open innovation capability. Open innovation is not the future, but it is certainly part of the future, and the smart approach is to use the tools of open innovation selectively.

Roche Diagnostics was a company that got a lot of value out of open innovation. In 2009 it put in place an experimental initiative to overcome specific technological problems that were preventing certain R&D programs from moving forward. The company identified six technology challenges that needed solving, and it opened the challenges up to the internal R&D community and to the external technology community through Innocentive and UTEK (now Innovaro), two well-known technology marketplaces. The manager in charge of the initiative described the outcome thus:

Internally, the number of responses to these six challenges was very low. But one very thoughtful response to one of the challenges was brilliant, and paid for the entire experiment. Externally, we used Innocentive and UTEK, and both had a far higher response rate than our internal experiment — more than 10 times the volume of responses, in fact. We offered a $1,500 reward, so this could have been an influencing factor. We received one novel solution, which really made the entire experiment worthwhile, but more than that was our very positive experience of involving external collaborators.

Roche’s experience was the closest thing we saw to a proper experiment that compared the merits of tapping into internal and external communities — and it really highlighted the value of tapping into the external group. But note that the potential respondents were being asked a very narrow, technology-specific question. Clearly, the external community would have been far less useful for tackling company-specific or situation-specific problems.

What are the downsides or limitations of open innovation? One set of concerns relates to how you handle intellectual property issues. At the time of writing, Roche Diagnostics was still working through the details of the licensing agreement with the person who solved its technological problem, and the transaction and licensing costs were far from trivial. A related issue is that without the strong IP protection that a market-maker like Innocentive provides, external parties are careful with what they will share. IBM discovered this in its Innovation Jam. As one manager recalled, “This Jam was established as an open forum, so anyone can take these ideas and use them. So we felt we were taking a few risks doing this, and perhaps it meant that our clients were quieter in the discussions than we would have liked. But it was important to make this open in every sense of the word.”

A second set of concerns was around how the companies we studied actually used the insights provided by external sources. One European telecom company had a “scouting” unit in Silicon Valley to keep an eye on exciting new startups and emerging technologies, but the scouting team discovered that the only technologies the folks back in Europe were interested in were those that would help them accelerate their current development road map. The really radical ideas, the ones that the scouting unit was putatively looking for, were simply too dissonant for the European development teams to get their heads around.

Which Parts of the Innovation Value Chain Are Companies Good At?

View Exhibit

A final concern is simply the time it takes to do open innovation properly. Companies such as Procter & Gamble, Intel and LEGO have put an enormous amount of investment into building their own external networks, and they are beginning to see a return, but you shouldn’t underestimate the time and effort involved.

Takeaway: External innovation forums have access to a broad range of expertise that makes them effective for solving narrow technological problems; internal innovation forums have less breadth but more understanding of context. Smart companies use their external and internal experts for very different types of problems.

Myth # 4. Pay Is Paramount

A dominant concern when organizations set out to grow their innovation capabilities is how to structure rewards for ideas. A common refrain is that innovation involves discretionary effort on top of existing responsibilities, so we have to offer incentives so people to put in that extra effort. The example of the venture capital industry was mentioned as a setting in which people coming up with ideas, and those backing them, all have the opportunity to become rich.

But both academic theory and our discussions with chief innovation officers indicate that this is a red herring.

Let’s briefly look at the theory. People are motivated by many factors, but extrinsic rewards such as money are usually secondary, hygiene-type factors. The more powerful motivators are typically “social” factors, such as the recognition and status that is conferred on those who do well, and “personal” factors, such as the intrinsic pleasure that some work affords. More specifically, there is evidence from psychology research that individuals view the offer of reward for an enjoyable task as an attempt to control their behavior, which hence undermines their intrinsic task interest and creative performance. 9 Parallel research in behavioral economics suggests that intrinsic motivation is especially likely to suffer when the incentives are large. 10

All of which suggests that you don’t need monetary rewards for innovation. Innovation is intrinsically enjoyable, and it’s easy to recognize and confer status on those who put their discretionary effort into it. Our research interviews provided plentiful evidence that this is the case.

Take the experience of UBS. With considerable upheaval at senior levels of the bank, the innovation movement was very much a grassroots effort — built around “UBS Idea Exchange,” an online tool. The executive in charge of that effort commented: “We found that employees having an opportunity to put forward their ideas brought huge personal rewards. We learned very clearly (through our experiments) that financial rewards would not have made any difference. People reported that recognition of their ideas was a reward in itself. They wanted to be engaged and to participate. We therefore involved people in presenting their ideas to senior management.”

The sentiment was echoed by the head of innovation at Mars Central Europe: “We try to recognize people rather than offer material rewards. We hold a corporate event, biannually, called Make The Difference, where ideas and success stories are celebrated. The Central Europe team is very proud of the fact that we won more awards at this event last year than any other region.”

Takeaway: Rewarding people for their innovation efforts misses the point. The process of innovating — of taking the initiative to come up with new solutions — is its own reward. Smart companies emphasize the social and personal drivers of discretionary effort, rather than the material drivers. 11

Myth # 5. Bottom-Up Innovation Is Best

There is a lot of enthusiasm among those writing about innovation, and among those working in R&D settings, for bottom-up activism or “intrapreneurship.” The reasoning here is straightforward: Top executives are not close enough to the action to be able to come up with or implement new ideas, so they need to push responsibility for innovation down into the organization. “Let 1,000 flowers bloom” has long been the mantra of big successful innovators like 3M, Google and W.L. Gore.

We wanted to believe this, and we sought out companies that had allowed, or even encouraged, bottom-up processes. We wanted to find cases where dramatic changes had emerged through bottom-up initiatives. But we came back emptyhanded.

Don’t misunderstand. There are plenty of examples of successful innovations that started out as below-the-radar initiatives, or as proposals that got rejected by top executives several times. Examples that spring to mind include Ericsson’s mobile handset business, Sony’s PlayStation and HP’s printer business. But, the point is, at some point all these innovation were picked up and then prioritized by top management. Successful innovations, in other words, need both bottom-up and top-down effort, and very often the link is not made.

During the research, we followed several cases of bottom-up innovation in considerable detail: UBS’s Idea Exchange, Best Buy’s resilience initiative and GlaxoSmithKline’s Spark program. These initiatives were neither great successes nor outright failures. They were able to demonstrate all sorts of modest successes, but they didn’t have the impact that their proponents would have liked either.

We discussed this issue in a workshop in late 2008, and the story that emerged was interesting. An executive working for RBS described the tension he had experienced between a top-down and a bottom-up approach. The company had put in place a range of tools: “Some of these are top-down tools that are owned by senior executives; others are bottom-up tools that we put in place to get involvement from large numbers of people. Top-down we have a group innovation board with senior decision makers and then 12 innovation boards. On a bottom-up basis, each division has its own pipeline, and makes the initial seed investment. Then as costs increase, the idea goes to the innovation board, and if it is approved the board will fund a pilot project, which in turn helps the development of the business plan.”

The underlying point, he observed, is that successful innovation requires close attention to both facets: “We’ve learned that you only get the top-down working if you get the bottom-up right too.”

This interplay between direction and empowerment is evident even in a declared bottom-up innovator like Best Buy. The success of the U.S. retailer is strongly tied to the cumulative effect of continuous experimentation and small bets at the level of individual stores. 12 Yet top management plays a significant role in channeling the collective creative energy toward desired areas by framing the innovation challenge in terms of finding new and better ways to service customers (dubbed the “customer centric-cycle”) — hence removing the risks of random or ill-focused innovation.

One final aspect of the bottom-up process is how to deal with those whose ideas are turned down. Broad-based innovation actually implies saying no to a lot of people, sometimes repeatedly. How their contributions are acknowledged, the transparency of the decision-making process and how the news is communicated are crucial factors in keeping the ideas coming. Even when their own ideas are rejected, employees also note what happens to the successful ideas of colleagues — and companies should not underestimate the stimulus of seeing front-line innovators sometimes given the opportunity to implement the ideas they generated. Indeed, Whirlpool, an exemplar in democratic innovation, goes one step further: It has established an Innovation E-Space that allows all employees to keep abreast of innovation activities and even to volunteer to work one another’s projects. 13 Once again, the interaction between bottom-up and top-down initiatives proves decisive.

Takeaway: Bottom-up innovation efforts benefit from high levels of employee engagement; top-down innovation efforts benefit from direct alignment with the company’s goals. Smart companies use both approaches, and are adept at helping bottom-up innovation projects get the sponsorship they need to survive.

Innovation is the lifeblood of any large organization, and many invest enormous amounts of time and effort in fostering distributed innovation programs. Web 2.0 technologies have made it possible to democratize the process even further, and offer ways of consolidating and evaluating radically new ideas.

But there are no quick fixes, panaceas or one-size-fits-all solutions — not surprisingly, since by definition not everyone can be a successful leader in innovation.

In this article we have taken an experience-led approach. Forget what the theory says: What are the experiences of companies putting these new tools for distributed innovation into practice? And the truth proves sobering. Online tools, open innovation communities and big collaborative forums all have their limitations. None is always right or always wrong. The best approach involves careful judgment and a deep understanding of the particular challenges a company is facing. By thinking through the pros and cons of each element, companies can manage their processes better.

About the Authors

Julian Birkinshaw is a professor of strategic and international management at London Business School. Cyril Bouquet is a professor of strategy at IMD in Lausanne, Switzerland. Jean-Louis Barsoux is a senior research fellow at IMD.

1. For a taxonomy of different types of innovation, see S. Conway and F. Steward, “Managing and Shaping Innovation” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 13-14.

2. See P. Skarzynski and R. Gibson, “Innovation to the Core: A Blueprint for Transforming the Way Your Company Innovates” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2008).

3. See “Building the Web 2.0 Enterprise: McKinsey Global Survey Results,” July 2008, https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Business_Technology/BT_Strategy/Building_ the_Web_20_Enterprise_McKinsey_Global_Survey_2174.

4. See M. Hansen and J. Birkinshaw, “The Innovation Value Chain,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 6 (June 2007): 121-130; and A. Hargadon, “How Breakthroughs Happen: The Surprising Truth About How Companies Innovate” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2003).

5. See, for example, J.H. Dyer, H.B. Gregersen and C.M. Christensen, “The Innovator’s DNA,” Harvard Business Review 87, no. 12 (December 2009): 60-67; and Skarzinski, “Innovation to the Core.”

6. A. Giridharadas, “Democracy 2.0 Awaits an Upgrade,” International Herald Tribune, Saturday-Sunday, Sept. 12-13, 2009, Currents, sec. A, p. 1.

7. M. Witzel, “Managers Who Use a Little Imagination for Big Rewards,” Financial Times, May 6, 2008, 18.

8. E. Byron, “A New Odd Couple: Google, P&G Swap Workers to Spur Innovation,” Wall Street Journal, Nov. 19, 2008, sec. A, p. 1.

9. See, for example, E.L. Deci, R. Koestner and R.M. Ryan. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation,” Psychological Bulletin 125, no. 6 (1999): 627–668.

10. H.S. James “Why Did You Do That? An Economic Examination of the Effect of Extrinsic Compensation on Intrinsic Motivation and Performance,” Journal of Economic Psychology 26, no. 4 (August 2005): 549-566.

11. K.J. Boudreau and K.R. Lakhani, “How to Manage Outside Innovation,” MIT Sloan Management Review 50, no. 4 (summer 2009): 69-76.

12. E. Kahn, citing Eric Mankin, “Innovate or Perish: Managing the Enduring Technology Company in the Global Market” (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 19.

13. J.W. Rivkin, D. Leonard and G. Hamel, “Change at Whirlpool Corporation (B),” Harvard Business School case no. 9-705-463 (Boston: Harvard Business Publishing, 2006).

i. For more details see Skarzynski, “Innovation to the Core”; and T. Davila, M.J. Epstein and R. Shelton, “Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit From It” (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing, 2006).

ii. L. Dunnavant, cited by A. Muoio, “They Have a Better Idea ... Do You?” Fast Company, (August 31, 1997), 2. i.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (7)

Bert shlensky, kevin mcfarthing (@innovationfixer), laurent blondeau (evidencesx), michael a. dalton.

- About InnoLead

- How to Use InnoLead

- What's Free on InnoLead (and What's Not)

- What’s Top-of-Mind for You?

- Sponsorship

- Contributing to InnoLead

- Assessments

- Data & Templates

- Directory of Firms

- Inquiry Hours

- Vendor Matchmaking

Innovation Assessments to Benchmark Your Program

What are Inquiry Hours?

Innovation Templates, Tools, Slides, Checklists, and Resources to Use

- Articles & Content by Topic

- Artificial Intelligence

- Employee Engagement

- Generative AI

- Ideation, Prototyping & Pilots

- Innovation Labs & Spaces

- Innovation Methodologies

- Innovation Metrics

- Open Innovation / Co-Creation

- Politics & Business Unit Engagement

- Recruiting & Training

- Remaking R&D

- Scouting Trends & Tech

- Strategy & Governance

- Working With Startups

- Special Features

- Innovation Software 2024

- How AI is Driving Competitive Advantage

- Innovation on Purpose

- Venture Studios & Venture Builders

- Innovating to Meet Sustainability Goals

- Innovation in Sports

- CEOs on Innovation

- Getting an Innovation Program Started

- Design as a Competitive Advantage

- Top 15 Global Hotspots for Corporate Innovation

- Top 25 Most Influential Innovators

- Aerospace & Defense

- Agriculture

- Construction

- Consumer Packaged Goods

- Energy & Utilities

- Engineering

- Entertainment & Media

- Financial Services

- Food & Beverage

- Hospitality

- Manufacturing

- Professional Services

- Telecommunications

- Transportation

- Template & Document Library

- Data Visualizations

- Data Insights Videos

The AI Vision Map

Generative AI Tournament Overview

Comparing Different Approaches to Driving Growth & Innovation

Generative AI Tools and Resources

- All Reports

- Building a Productive Portfolio

- 2023 Benchmarking Data

- 2023 Compensation Data

Innovation Software: The Start of the Gen AI Era

How AI is Influencing Corporate Innovation Priorities in 2024

Driving Growth Through New Ventures and Corporate VC

Smarter Scouting: Best Practices

- Upcoming Webcast Calendar

- Building Bridges Startup Series

June 28th: Startups Transforming Cybersecurity

August 16th: Startups Transforming Business Automation

- About IL Events

- Upcoming Events

- Members-Only Web Meetings

- Event Photo Galleries

- Speaking at an IL Event

Impact 2024 - Join InnoLead for the Year's Most Useful Corporate Innovation Conference

- Getting Our Advisory Support

- Job Listings

- Assessment Tests

- Podcast: Innovation Answered

- Innovation Illustrated

- Innovation Q&A

- Print Magazine

- Members-Only Slack Channel: Network & Get Advice

- Data Insights

- Skill Building Workshops

- Video Interviews

- Directory of Innovation Firms

- Expert Advice from Our Partners

- Thought Leadership

- List of Sole Proprietor/Small Firms

- Exclusive Discounts for InnoLead Members

- Email Newsletter

Try Out InnoLeadGPT, Our AI Chatbot

How to Use Myth Busting to Unlock Innovation and Growth

We all know we need to learn new things to fuel innovation and growth. But what if I said it could be just as powerful to un-learn the “myths” that confine our thinking?

Erik Falck, Director of Innovation & Growth Platforms, Johnsonville LLC

One of my favorite hobbies is playing the guitar, but that wasn’t always the case. When I first started, I believed several unspoken myths — all of which were keeping me from getting better. The worst of these was assuming that learning the guitar was primarily an “artistic” endeavor. The truth is, at first, learning to play an instrument is mostly about developing muscle memory. That’s because music must happen in rhythm, in real time. It’s more like learning a sport than learning to paint or write. When I tested this myth by changing up my practice routine to focus on muscle memory drills, the myth was busted, and I finally started making progress.

In a similar way, the growth of our businesses also depends on busting myths. I lead Innovation at Johnsonville LLC , based in Sheboygan Falls, Wisconsin. Today we are the US leader in sausage and sell in over forty global markets. But the company, which is privately owned, might still be only a regional Midwest brand if it hadn’t decided a couple decades ago to challenge two key myths:

- There’s no practical way to sell fresh sausage coast to coast

- We can get everyone to love bratwurst as much as we do here in the Midwest.

In the process of busting these myths, Johnsonville adopted new supply chain technologies (including low temperature storage) and learned how to make great sausage that satisfies local tastes (such as Chorizo and Parmesan). Over time, these innovations helped make Johnsonville the national brand and global enterprise it is today.

Many longstanding myths like these might naturally get retired, given enough time and employee turnover. But “time and turnover” isn’t a proactive leadership strategy. Since growth and innovation is partly a matter of speed, we set out to develop a way to accelerate this process.

We identified four key steps to Myth Busting:

1. State the myth in a testable way

This is critical, because in everyday conversation, we often phrase our myths in ways that make them impossible to prove or disprove. “We should market to people who already love sausage,” is not testable. But a statement such as, “Loyal category buyers are a larger growth opportunity than non-loyal buyers,” can be investigated.

2. State the potential business benefits

What’s it worth to bust this myth? A little motivation helps get people engaged and thinking. Besides the bottom line, don’t forget to consider benefits to quality, culture, complexity, and career opportunities.

3. Complete one or more “tests” of the myth

The amount of testing you’ll need to do depends on many factors, such as the consequences of being wrong and the level of skepticism in the organization. Tests can come in at least three different levels, ranging from quick and easy, to more complex and robust:

- Level 1 – What can be readily observed today? Are there examples in the marketplace now, existing data we can mine, or an expert to consult?

- Level 2 – What can we learn via research? Is there a concept, survey, or A/B test we could field?

- Level 3 – What would it take to validate this with in-market testing?

It helps to identify a ‘skeptic’ — someone who is willing to both defend the myth, and indicate what level of evidence they would accept to consider it definitively busted.

4. Secure broad agreement that the myth is busted or confirmed .

Since myths are often embedded in the culture, this step is key. Before you do any tests, it helps to identify a “skeptic” — someone (often a senior leader) who is willing to both defend the myth, and indicate what level of evidence they would accept to consider it definitively busted.

Having a process is one thing, but how did we actually generate a list of our current myths to test? This turned out to be the easy part. Once we showed how busting old myths was part of what made our company what it is today, and gave our people permission (and resources) to challenge accepted beliefs, the myth ideas started to flow. We piloted the Myth Busting approach with our marketing department, where small teams easily generated more than thirty testable myths in a few brainstorming sessions, including:

- Without customer X, a product launch cannot be sustainable and scalable ( busted )

- Consumers will never pay for a premium-quality frozen meat product ( busted )

- Investing in e-commerce ads is just shifting sales from one channel to another ( busted )

- Consumers are more brand loyal in e-commerce than they are in store ( confirmed )

- Most consumers know the difference between fresh and fully-cooked sausage ( mixed ).

After each myth was busted or confirmed, the teams began leveraging each nugget of learning to drive new or optimized growth initiatives.

Word about what was happening in marketing spread quickly. Next, our executive team asked me to roll out Myth Busting across the organization with all functional leaders. These leaders’ enthusiasm and the boldness of their myths exceeded even my high expectations, including:

- Drilling down to the lowest possible level of detail gets the best business results (Finance)

- A manufacturing facility cannot get to zero unplanned downtime (Operations)

- We always need forecasts to run our business (Continuous Improvement).

After functional leaders shared their Myth Busting results and action plans with our executive team, CEO Nick Meriggioli remarked, “This has jump-started our culture to hopefully never stop questioning the status quo, and to continue to push beyond our boundaries to find new and better ways to do things in all areas.”

It’s now common in meetings to hear someone ask, ‘Is that true, or is it a myth?’

Myth Busting spread at Johnsonville even better than I imagined it would. It’s now common in meetings to hear someone ask, “Is that true, or is it a myth?” We just started our second cycle of formal Myth Busting with the marketing department, and we’re even challenging parts of the growth strategies that we developed after the first round! New thinking and innovation are flowing more easily and naturally from our teams.

As corporate innovators, our role is to think differently and question the status quo. It’s in our nature, it can be exciting, but it also has its challenges. One of the most enjoyable results of introducing Myth Busting was being able to step back and see so many other colleagues play the “disruptor” role, and to play it so effectively. A few have even nominated me to be their myth skeptic!

Introducing Myth Busting in your organization can be an effective way to unlock more growth, and improve your company’s overall culture of innovation.

E rik M. Falck is Director of Innovation & Growth Platforms at Johnsonville LLC. Falck’s views are his own, and do not necessarily represent those of Johnsonville. InnoLead welcomes contributed pieces from current corporate professionals; our guidelines are here .

New Research Busts Popular Myths About Innovation

Should the U.S. invest in a generation of new intercontinental ballistic missiles? What has really propelled decades of consistently rising computer performance? Is research into new forms of nuclear power a dead end? And should we credit Elon Musk with revolutionizing the automobile industry, or is he just riding the coattails of history?

These are the sorts of questions that researchers who study the history of innovation and what it says about the future say we can now answer—thanks, of course, to innovation. Using both previously untapped pools of data and new analytical methods, along with the usual tools of modern-day forecasting—namely, the predictive algorithms often described as “artificial intelligence” —they are taking a quantitative approach to examining how quickly technologies improve.

Brought to you by:

The 5 Myths of Innovation

By: Julian Birkinshaw, Cyril Bouquet, Jean-Louis Barsoux

This is an MIT Sloan Management Review article. Historically, most managers equated innovation primarily with the development of new products and new technologies. But increasingly, innovation is…

- Length: 10 page(s)

- Publication Date: Jan 1, 2011

- Discipline: Strategy

- Product #: SMR376-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Educator Copy

$4.50 per student

degree granting course

$7.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This is an MIT Sloan Management Review article. Historically, most managers equated innovation primarily with the development of new products and new technologies. But increasingly, innovation is seen as applying to the development of new service offerings, business models, pricing plans and routes to market, as well as new management practices. There is now a greater recognition that novel ideas can transform any part of the value chain -and that products and services represent just the tip of the innovation iceberg. This shift of focus has implications for who "owns"innovation. It used to be the preserve of a select band of employees -be they designers, engineers or scientists -whose responsibility it was to generate and pursue new ideas, often in a separate location. But increasingly, innovation has come to be seen as the responsibility of the entire organization. For many large companies, in fact, the new imperative is to view innovation as an "all the time, everywhere"capability that harnesses the skills and imagination of employees at all levels. Making innovation everyone's job is intuitively appealing but very hard to achieve, but many companies have tried -and nearly all believe that's it's critical to continue trying. To understand these challenges, and to identify the innovation practices that work, the authors spent three years studying the process of innovation in 13 global companies. Many of the standard arguments for how to encourage innovation in large organizations were confirmed, but some surprises were uncovered as well. In this article the authors focus on the key insights that emerged from their research, organized around five persistent "myths"that continue to haunt the innovation efforts of many companies. The five myths are: (1) The Eureka Moment; (2) Built It and They Will Come; (3) Open Innovation Is the Future; (4) Pay Is Paramount; and, (5) Bottom Up Innovation Is Best.

Jan 1, 2011

Discipline:

MIT Sloan Management Review

SMR376-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

The Innovation Myth: Why It’s Insights, Not Ideas, That Truly Drive Innovation

The Innovation Myth: Why It’s Insights, Not Ideas. That Truly Drive Innovation

There are many myths of innovation. One age-old myth when it comes to the notion of innovation is: that of the lone inventor sitting in his lab, hit by a bolt of lightning and a moment of explosive inspiration, and BOOM…out pops the big idea. At least, that’s how the story is typically told. But that telling is a bit of an illusion, often aligning with how people envision innovation: a flash of brilliance, an inspired idea, and Eureka! A new, life-changing thing is born that transforms the modern world for the better. The truth is — as we all know — a lot messier than that.

It’s time to put away some of the old myths of innovation, starting with the illusion that ideas drive innovation.

But aren’t ideas the basis of innovation?

From Shark Tank to TED talks, popular culture has sold us the thought that an idea, packaged and presented, exists as the ultimate solution to a problem. It’s one of the myths of innovation that this never-ending glorification of ideas that have led us to put our attention in the wrong place. Contrary to what many believe, the idea is only part of the process — and it’s not the beginning. Innovation starts a lot earlier than when you assemble your team in a room to brainstorm; it begins with learning about your customer and getting to know them deeply — the kind of closeness that goes way beyond just asking them what they want next. Ideas, in fact, have a high failure rate when generated in a vacuum without first considering how to serve customer needs and desires.

So, instead of ideas, we need to direct our focus elsewhere: on insights.

Why are insights so important?

To quote Bob Dylan “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The make-up of the buying public has evolved in the past two decades, and we are experiencing a fundamental shift from an era of mass consumption to a new era of context and personalization. Consumer expectations are changing and value is now very personal; it’s generated less through the selling and buying of goods and more through an ecosystem of information, services, experiences, and solutions. The result: It’s never been more critical for organizations to establish and maintain an intense focus on an understanding of their customers’ lives. Customer knowledge informed by an empathetic mindset is critical for creating relevant new offerings that are both pertinent and distinct, and this brings us to insights. Insights are the cornerstone of the innovation process and a catalyst for creating new value for your customers. They must be the first stage of your innovation process for that reason — not ideas .

What is an insight?

Insight is a horribly misused word, much in the same vein as “brand,” “strategy” and “innovation.” So, let us first restore some meaning to the word by considering what insight is not :

INSIGHT IS NOT DATA

Data can take many forms, but we have to remember it is just that — data. Alone, data is not an insight, and it does not do your thinking for you. With masses of data at hand, the fundamental problem is a lot more essential: How do we mine and analyze the data to reveal insight we can act on? Look at your data holistically and be cautioned against becoming attached to that singular inspiring data point that can drive a swift conclusion. Think holistically. Analyze intensely. Insight definition requires you to take a multi-dimensional view.

AN OBSERVATION IS NOT AN INSIGHT

Observations are an incredibly important part of creating insight but are still only one data point to consider (and should never stand alone). They are facts that lack the “why” and the “motivation” behind a consumer’s behavior. Never stop short of the hard work involved during the process of insight definition; of converting an astute observation into something more meaningful and actionable. Always get to the “why.”

A CUSTOMER WISH OR STATEMENT OF NEED IS NOT AN INSIGHT

An Insight is not an articulated statement of need. Insights are less apparent, intangible, latent. A hidden truth that is the result of obsessive digging. Anytime you hear “I want” or “I need” in a statement, step back and pause, as you probably need to dig deeper and understand the motivation, and the why behind “the want.” Articulated needs are ideal for defining features and benefits, but do not lead to insights that have the gravity to topple existing categories and create new ones. Obsess about the outcome people want; don’t merely record their statements of need and assume you have insights because you likely do not.

What’s the best way to find insights?

We advocate the use of ethnography, a vital tool in the innovation toolbox that gives you a real-world understanding of people’s preferences, motivations and needs by examining the environments buyers inhabit and the cultural and societal forces that influence their behavior. In a sense, it’s deliberate, systematized empathy. Humans are wildly complex, a swirl of influences, shared beliefs and experiences that form us separately as individuals. Ethnography provides a peek behind the consumer curtain that can be incredibly valuable, unlocking innovation and strategic business opportunities, and boosting competitive advantage and customer loyalty.

We recommend you direct your empathy toward four areas: understanding what influences consumer behavior from a cultural, social, personal and psychological perspective.

1. CULTURAL FORCES

Cultural forces — friends, families, the environment in which a person grew up — profoundly affect humans, and all heavily influence the values they hold, and the behaviors they feel are socially acceptable. The more we understand how the world around people forms their behavior, the more we can empathize, create offerings that reflect that empathy and are therefore more meaningful and relevant.

2. SOCIAL AFFILIATION

Social groups profoundly influence people’s consumption behaviors and reflect the mindsets, values, and lifestyles they collectively share with others like them. Tap into the human need to both self-express and connect with others, and you’ll find ways to leverage that belonging to your brand’s benefit.

3. PERSONAL LIFESTYLE

Lifestyle — the way we live and what artifacts we attach meaning to — is a consistent pattern in a consumer’s life, something that’s influenced by a person’s personality, values, attitudes, and beliefs. Understand the personality traits that make someone unique, and you can understand what will appeal to them, their outlook on life, and what will fit with their consumption habits.

4. PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

People’s life experience to date uniquely form their perception of the world, and how they selectively view, process, organize and interpret it. Cracking the perceptive code of a given audience is absolutely key. As innovators, we have to battle our way through that stimuli soup into the minds of consumers, and the best way to do this is by hitting them where it matters: by understanding their aspirations, motivations, desires, and most importantly what they perceive to be meaningful and why. Take the time and dig into their gray matter and you’ll be surer that the message you’re sending is the right one.

How do you turn knowledge into insight?

Casual observation and merely knowing are not enough. Insight definition takes work; it’s a skill that requires creativity, persistence and deep thinking to craft. The most powerful insights come from rigor and serious analysis to translate large amounts of data into concise and compelling findings. Use written insight statements to turn research data into actionable insight to inspire new ideas for product and service development.

How to Write an Insight Statement

Writing consumer insight statements is a bit of a black art — a little creativity, a little analysis. It hinges on a 3-sentence structure designed to balance details of analysis with a rallying cry for action.

SENTENCE #1: THE SITUATION

Set the context for your consumer insight statement by describing the current situation and the incumbent consumer behavior. This part should capture both the environment and a simple observation of a given situation going on within it.

SENTENCE #2: THE FRUSTRATION

Describe the dilemma the consumer faces and articulate why this is a frustration in their life. Crafting this part comes from understanding the barriers that stand in the way of achieving the subject’s needs or desires, and it should have an emotional element that elicits a “we need to fix this” response.

SENTENCE #3: THE FUTURE DESIRE

Envision the consumer’s desired end-state and ideal situation, and describe the tangible business result they’ll get from using your product or service (remembering that consumers don’t necessarily care what a product or service is, but what it does for them).

Here is an example: “We enjoy using our outdoor pool but are often bothered by mosquitos. I am hesitant about using insect repellents on my children’s skin because I am unsure how safe they are. I wish there were a repellant that had the strength to improve protection around pools, so I did not have to apply repellants to my children’s skin.”

Don’t Forget About the Big Picture

The biggest takeaway here is that insight is fuel for ideation — insights reduce irrelevance and help you focus on what is meaningful, setting the foundation for successful product and service development. Once you’ve got them, you can rephrase them to be actionable for the creative process, turning them into “How might we?” statements. In the above example: How might we improve protection from mosquitos without having to apply repellent to the skin?

Think of the insight statement as the question, the idea as the answer, and the resulting product or service as the solution.

Get beyond the myths of innovation, increase your grasp of insight to understand your customers, and you’ll know what you’re really solving for, which simply makes for smarter business.

This article was originally published in INNOVATION Spring 2018 , the Industrial Design Society of America’s (IDSA) quarterly and one of the best places to learn about the practice of industrial design. Every issue of INNOVATION reaches IDSA’s membership, universities, associations, design consultancies and subscribers around the world.

INNOVATION is a benefit of membership. Join today .

Join Our Newsletter

Receive updates on all things THRIVE

- Email * Enter email below to sign up for the Thrive newsletter

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Related Posts

Related services, related resources, why design thinking is critical for the prosperity of your business., how to leverage user memory structures in design, mobile ethnography. new methods demand new approaches., design research.

Growth Strategy

Brand strategy, what is insight the 5 principles of effective insight definition, unlocking new value through quantified experience mapping, customer journey mapping: 10 sure-fire steps to success.

- Pre-Markets

- U.S. Markets

- Cryptocurrency

- Futures & Commodities

- Funds & ETFs

- Health & Science

- Real Estate

- Transportation

- Industrials

Small Business

Personal Finance

- Financial Advisors

- Options Action

- Buffett Archive

- Trader Talk

- Cybersecurity

- Social Media

- CNBC Disruptor 50

- White House

- Equity and Opportunity

- Business Day Shows

- Entertainment Shows

- Full Episodes

- Latest Video

- CEO Interviews

- CNBC Documentaries

- CNBC Podcasts

- Digital Originals

- Live TV Schedule

- Trust Portfolio

- Trade Alerts

- Meeting Videos

- Homestretch

- Jim's Columns

- Stock Screener

- Market Forecast

- Options Investing

- Chart Investing

Credit Cards

Credit Monitoring

Help for Low Credit Scores

All Credit Cards

Find the Credit Card for You

Best Credit Cards

Best Rewards Credit Cards

Best Travel Credit Cards

Best 0% APR Credit Cards

Best Balance Transfer Credit Cards

Best Cash Back Credit Cards

Best Credit Card Welcome Bonuses

Best Credit Cards to Build Credit

Find the Best Personal Loan for You

Best Personal Loans

Best Debt Consolidation Loans

Best Loans to Refinance Credit Card Debt

Best Loans with Fast Funding

Best Small Personal Loans

Best Large Personal Loans

Best Personal Loans to Apply Online

Best Student Loan Refinance

All Banking

Find the Savings Account for You

Best High Yield Savings Accounts

Best Big Bank Savings Accounts

Best Big Bank Checking Accounts

Best No Fee Checking Accounts

No Overdraft Fee Checking Accounts

Best Checking Account Bonuses

Best Money Market Accounts

Best Credit Unions

All Mortgages

Best Mortgages

Best Mortgages for Small Down Payment

Best Mortgages for No Down Payment

Best Mortgages with No Origination Fee

Best Mortgages for Average Credit Score

Adjustable Rate Mortgages

Affording a Mortgage

All Insurance

Best Life Insurance

Best Homeowners Insurance

Best Renters Insurance

Best Car Insurance

Travel Insurance

All Credit Monitoring

Best Credit Monitoring Services

Best Identity Theft Protection

How to Boost Your Credit Score

Credit Repair Services

All Personal Finance

Best Budgeting Apps

Best Expense Tracker Apps

Best Money Transfer Apps

Best Resale Apps and Sites

Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) Apps

Best Debt Relief

All Small Business

Best Small Business Savings Accounts

Best Small Business Checking Accounts

Best Credit Cards for Small Business

Best Small Business Loans

Best Tax Software for Small Business

Filing For Free

Best Tax Software

Best Tax Software for Small Businesses

Tax Refunds

Tax Brackets

Tax By State

Tax Payment Plans

All Help for Low Credit Scores

Best Credit Cards for Bad Credit

Best Personal Loans for Bad Credit

Best Debt Consolidation Loans for Bad Credit

Personal Loans if You Don't Have Credit

Best Credit Cards for Building Credit

Personal Loans for 580 Credit Score or Lower

Personal Loans for 670 Credit Score or Lower

Best Mortgages for Bad Credit

Best Hardship Loans

All Investing

Best IRA Accounts

Best Roth IRA Accounts

Best Investing Apps

Best Free Stock Trading Platforms

Best Robo-Advisors

Index Funds

Mutual Funds

var mps=mps||{}; mps._queue=mps._queue||{}; mps._queue.gptloaded=mps._queue.gptloaded||[]; mps._queue.gptloaded.push(function() { (mps && mps.insertAd && mps.insertAd('#dart_wrapper_badgec', 'badgec')); }); The Future of Innovation: a CNBC.com Special Report

Myths — and realities — about innovation.

Innovation – a common answer to business challenges. How can my company gain market share? How can I succeed as an entrepreneur to steal market share from established competitors?

Yet, despite agreement on innovation’s importance, few get it right. Just take a look at the Fortune 500 list from 1955. Of the 500 companies listed, only 71 hold a place today. Over time, the majority fell behind, often because of an inability to adapt and innovate in shifting and emerging markets.

Innovation is difficult. Part of this difficulty starts with many would-be innovators sharing several misconceptions about the process of innovation itself. Let’s review some common myths of innovation and separate fiction from fact.

Myth 1: Innovation comes from isolated geniuses

When we visualize innovation, we often picture the lone inventor as someone much like “Doc” Brown from Back to the Future . This isolated genius is narrowly focused on his or her own work, devoid of social interaction or collaboration. Yet, researchers have found repeatedly that successful innovation depends on social networks, and breakthrough innovation is more likely when innovators maintain vast, diverse social connections.

Take, for example, IDEO , the design firm celebrated for innovations such as Apple’s first mouse and the Palm V personal digital assistant. UC Davis’ Andrew Hargadon and Stanford’s Robert Sutton discovered that core to IDEO’s creativity was its ability to draw on knowledge learned from past clients across different industries. By leveraging social connections and past interactions, IDEO could successfully pull from solutions in one domain to solve problems in another.

While there’s a time and place for closing the lab door and getting to work, innovators are likely to be much more creative if they actively maintain large and diverse social networks that help them “borrow” solutions from related domains.

Myth 2: Innovation is about a “eureka” moment

Often accompanying the image of the lone inventor is the belief that innovation strikes in a sudden “eureka” moment. In reality, innovation tends to arise from a lot of trial and error, with the most successful innovators taking risks to discover either flaws or new opportunities with their ideas. Even the greatest “eureka” moments must be put to the test.

For example, when founder Reed Hastings conceived of Netflixin 1997, he planned to focus the business on DVD rentals by mail, charging customers per rental and late fees for overdue disks. But as Netflix got underway, Hastings discovered a critical flaw in the original business model: Netflix was paying $100 to $200 to acquire customers who were only spending $4 on a single rental. Hastings’ original “eureka” moment had created a dysfunctional business model.

To address this problem, Hastings moved to a pre-paid subscription model, allowing customers up to four rentals per month. While initially perceived as a way to screen out low-value customers, this shift led to a surprising revelation – customers loved always having movies in their house! Building on this insight, Netflix shifted to unlimited rental plans, a business model that would ultimately turn the movie rental industry on its head.

As Netflix illustrates, the original “eureka” moment rarely provides the final solution. Instead, individuals and firms should recognize even the best ideas need a test drive.

Myth 3: Great innovations will be easily recognized by others

A third myth is that great innovations will be obvious to others – that a product or technology represents such a breakthrough that investors, partners and other supporters will clamor for a stake. The unfortunate reality is many audiences have a hard time assessing the potential of new products and ideas.

In my research with Stanford’s Kathleen Eisenhardt, we found that experienced venture capitalists held off investing in a promising start-up until the innovators could demonstrate “proof points.” These proof points are substantial signals of accomplishment validated by relevant third parties. Entrepreneurs were far more likely to be successful at quickly raising investment funds if they timed their raising around a recent proof point.

"Innovators are likely to be much more creative if they actively maintain large and diverse social networks that help them 'borrow' solutions from related domains." -Assistant Professor, London Business School, Benjamin L. Hallen

As one example, Mark Zuckerberg and his co-founders didn’t try to raise money to fund their innovation purely based on the idea of Facebook . They waited to raise their first outside investment round until they could show some powerful proof points: that the social networking service had already launched and quickly expanded.

For those seeking to bring innovations to market, it’s important to keep in mind that many audiences will have trouble recognizing the potential of an innovation when it’s just an idea, even if it’s a very good one associated with smart people. Innovators need to carefully demonstrate their idea’s viability and potential in a quick, low-cost manner, showing proof points sooner rather than later.

The pursuit of innovation is a challenge. All too often, we’re inhibited by our own misconceptions about how innovations occur. Yet by recognizing that innovation depends on maintaining a diverse set of social connections, viewing initial “eureka” moments as the start of a learning process, and proactively prioritizing early steps so as to best showcase an innovation’s viability and potential, innovators may improve their chances of having a great impact.

Benjamin L. Hallen is an assistant professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School .

Related Securities

Must-read: Scott Berkun Spells Out The Myths of Innovation

Podcast (english): Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:06 — 6.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Blubrry | Email | RSS

The myths of innovation are ubiquitous. Everyone thinks they know what innovation is and means yet in fact innovation is probably one of the most overrated business concepts. ‘Poor is the substance, alas! and yet I’ve read all the books,’ the warning sent by French poet Stéphane Mallarmé would be perfectly valid for most of the literature devoted to innovation . There are books on that subject; however, which are worth reading such as the inevitable myths of innovation by Scott Berkun. We published this piece for the first time in 2010. We are republishing it because of its relevance in the current context of 2022.

The Myths of Innovation is a must-read for would-be innovators

Berkun is a full-time writer and speaker and former program manager at Microsoft, the man behind the success of Internet Explorer at a time when the Web was dominated by Netscape.

He also delivers lectures such as this amazing Carnegie Mellon presentation (per below) on the book I am describing here.

His book is not based on dubious principles but spells out clearly the dos and don’ts of innovation. It’s a lot more powerful than most books because of that because it’s easier to learn from mistakes than mimic other people’s behaviour.

Here are Scott Berkun’s ten myths of innovation summed up in a few words, and I hope this will convince you to buy a copy of his book too.

All ten myths described by Scott Berkun in his book

If many innovations are described as magical moments, the truth is often more complex: hard work is required, the Eureka moment is often coming at the end of that process (not the beginning).

Most Eureka legends aren’t real; they are myths aimed at giving a romantic view of innovation,

We understand nothing about the history of innovation

Myth number 2: we understand the history of innovation. Well, so we think, but most of the time we don’t.

Most of the stories we read about innovation aren’t real either.

Google wasn’t a search engine to start with, nor was Flickr a photo-sharing platform, etc.

In fact, most innovations are the results of errors, changes, and corrections, but we like history to smooth things out and make them sound perfect and simple.

Myth number 3: there is a method for innovation.

How does one deliver innovation? Despite our attraction to recipes, innovation is, in essence, a ‘charge into the unknown’ and therefore, a method for innovation is a bit of an oxymoron,

Myth number 4: people love new ideas, so we like to think, but most of the time it’s not true.

Changing one’s habits is always a challenge, and that is true of customers too (remember Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the chasm?)

There is no end to the list of rejections that innovators have to face. Change management is an innovator’s best friend,

The lone inventor

Myth number 5: the lone inventor. We like stories in which a genius single-handedly changed the world: Edison invented the electric light; Ford invented the automobile; Apple invented the first graphical user interface, etc.

All wrong! And most of these stories are wrong.

Often, innovations happen simultaneously, too (in different countries at approximately the same time).

Lastly, successful companies are often started by a group of people, not the obligatory lone inventor.

Myth number 6: good ideas are hard to find.

Ideas are everywhere, and not just found as a result of a brainstorm session (a tool which most of the time is badly used and implemented).

Ideas come in more than many ways, mostly through trial and error.