MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

How the Internet is Transforming our Lives

- TR Staff archive page

Keep Reading

Most popular, how to opt out of meta’s ai training.

Your posts are a gold mine, especially as companies start to run out of AI training data.

- Melissa Heikkilä archive page

Why does AI hallucinate?

The tendency to make things up is holding chatbots back. But that’s just what they do.

- Will Douglas Heaven archive page

The return of pneumatic tubes

Pneumatic tubes were supposed to revolutionize the world but have fallen by the wayside. Except in hospitals.

- Vanessa Armstrong archive page

Supershoes are reshaping distance running

Kenyan runners, like many others, are grappling with the impact of expensive, high-performance shoes.

- Jonathan W. Rosen archive page

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

A Brave New World: How the Internet Affects Societies

Meeting summary (11 may 2017).

Professor Dr Erik Huizer

Chief Technology Officer, SURFnet; Research Associate, University of Utrecht; Internet Hall of Fame Inductee

Syed Ismail Shah

Chairman, Pakistan Telecommunications Authority

James Arroyo OBE

The Ditchley Foundation

Dr Unoma Ndii Okorafor

Founder & CEO, WAAW Foundation; Co-Founder & CEO, Radicube Technologies

Rebecca MacKinnon

Director, Ranking Digital Rights, New America

Introduction

With the rise of the Internet in recent decades, its impact on society has been transformative at multiple levels – including in communication, access to knowledge and social interaction.

While early adopters saw possibilities in using the Internet as a vehicle through which the many challenges facing the world might be addressed, more recently questions have arisen about how Internet technology can be used to spread false and misleading information, and to radicalize and recruit potential terrorists. There are also concerns as to whether the Internet serves to reduce or exacerbate social divisions; and whether it contributes to the dilution of social norms or, conversely, serves as a channel to perpetuate them.

In this context, the technical community has initiated a conversation about the role that the Internet is – and should be – playing in societies. Notably, for some within the technical community, there is growing unease that the very technologies that supported Internet growth are also enabling behaviours that are socially unacceptable, putting pressure on the way people use and experience the online environment.

On 11 May 2017 the Internet Society and Chatham House convened a roundtable discussion, held under the Chatham House Rule, [1] at which a culturally and geographically diverse set of participants examined questions relating to how the Internet affects social norms and societies as a whole, as well as its impact on people’s daily lives.

Access, capacity and the developing world

The Internet is for everyone, according to the Internet Society’s vision, but it has not quite happened for all. Access to the Internet is essential for empowerment of certain groups, especially women, connecting them with global markets and communities. Yet, women in Africa are 50 per cent less likely to be online than men; and there are digital divides also affecting people with disabilities, and people lacking digital skills.

The Internet in the developing world

An Internet Society survey of 2,100 people across the world has found that people in developing markets remain optimistic that the benefits of connecting far outweigh the perceived risks. On the contrary, in the Western hemisphere, conversations about the Internet risk losing the sense of genuine excitement and urgency that many in developing countries feel about getting online.

The mobile Internet has been a game changer in developing countries. In Pakistan there were 3.79 million broadband connections through 3G in 2013. In just three years, however, the advent of 4G has increased the number of mobile broadband connections to 43 million. For regulators in developing countries, the first step is to bring people online, and after that to focus on new services. For example, graduates in Pakistan increasingly want to be entrepreneurs rather than be employed by others. Entrepreneurial activity, in turn, increases financial inclusion: Pakistan’s vision is now that by 2020 50 per cent will have their own bank account.

Digital divides

Connectivity is growing fast, but some places are not doing as well as others. ‘Access’ is not as simple as giving people connection to the Internet. There are multiple, multi-dimensional factors contributing to digital divides, chief among them gender, access to education and skills, lack of locally relevant content, lack of human capacity, and weak local supply chains. All these issues need to be addressed if the vision of the ‘Internet for everyone’ is to be achieved.

In particular, a lack of localized content risks turning Internet users from developing countries into consumers rather than creators. An estimated 90 per cent of jobs that will be created over the next decade will require technical skills, and Africa will be, in demographic terms, the youngest continent. There is an urgent need to develop relevant skills to both preserve and expand opportunities for all.

At the same time, technological innovations are further deepening divides. There is a risk that greater digital inequality will spread within countries – between those who are connected and those who are not. This inequality will affect jobs and the economic performance of countries and communities. In a scenario in which there is likely to be a threshold for innovation to see gains in the economy, without proper access and education many people will be left behind.

On the more positive side, the spread of Internet uptake can also work to address divides within societies. In Pakistan, for example, some 70 per cent of medical students are women, but for cultural reasons only 20–30 per cent of practising doctors are women – even though many female patients prefer to be seen by a female doctor. There are successful examples of using technology to bring women and girls into the workforce, for example by enabling women to access female doctors via remote consultations. As another example of the interplay between local and global, Pakistan is home to one of the world’s largest ‘virtual’ universities, established in 2002.

Trust and fear in the online environment: the ‘silent majority’ is vanishing

A case can be made that, in the ‘real’ world, the Chatham House Rule is comparable with the Internet Society’s vision of the ‘Internet for everyone’. The Rule is intended to ensure that people can speak openly and freely, but also securely. It provides a channel for an issue to be thoroughly debated, and this lends legitimacy. Members of the technical community may view confidentiality as secrecy, but on difficult issues people of good faith need some room to talk and interact freely.

Online debate

The confidentiality offered by the Chatham House Rule encourages people to speak freely, but its efficacy depends on physical meetings in the real world, at which the presence of a silent majority plays an important role in curbing extreme behaviour. No equivalent mechanism exists in the online environment: the silent majority is not only silent, but invisible. As a result, debate can spin out of control.

One speaker remarked that ‘fear is trumping trust’ online. It is important that people are able to speak freely online, but there is no shared moral and/or cultural code influencing how people behave. The risk, therefore, is that online debate is reduced to the lowest common denominator: ‘Civil debate according to the Chatham House Rule is hardly possible online. This leads to a sort of extreme behaviour in debates, which in turn leads to self-censorship.’

Real-world implications

A case can be made that in some instances hate speech may provoke actions in the real world that threaten the personal safety of many. In Rwanda, for example, where ‘hate media’ had a role in fuelling the genocide in 1994, the government is now attempting to restrict what is published online. In early 2017 the government of Cameroon blocked Internet access for the English-speaking part of the country for 93 days. The government said that it reserved the right to stop the Internet being used as a tool to stoke internal division and hatred. However, Internet filtering and shutdowns create extensive collateral damage, and have, in the case of Cameroon, for example, been condemned by the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression as an ‘appalling violation’ of the right of freedom of expression.

Globalization and the Internet as an engine for economic growth

Governments around the world recognize that the Internet is an engine of growth. States are committed to connecting more people (1.5 billion by 2020, in line with the ITU target) to advance the gains that can be made from the Internet economy.

The evolution of the Internet, particularly from the 1990s, has coincided with the end of the post-war East–West order (the so-called ‘end of history’), and the advance of globalization. Whereas diplomacy has traditionally depended on adapting behaviour to local culture in order to reduce friction, what is new is that the Internet effectively ‘collapses’ concepts of place, and, with that, the ability to hold separate value systems in different places.

The role of the state

Workshop participants discussed the appropriate role of the state in an increasingly globalized – but simultaneously fragmented – world. Explicitly Western values have driven the agenda to date, and states that do not buy into those values will view the Internet’s advance as a direct threat. Internet policy dialogue tends to lump non-Western countries or governments together, as though they are all alike. However, there are certain ‘rule-of-law’ states that place more value on social responsibility and cohesion than on individual personal expression. The challenge for states is thus to figure out how to work together without necessarily quite agreeing on such values.

In the opinion of one speaker, quick change will be resisted and conflict is likely to occur. Another disagreed, contending that the Internet’s values are aligned with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

There are conflicts between the principles of state sovereignty and globalization. Internet regulation is mostly confined within state borders, but both regulation and technical decisions can have global impacts. One participant asked if it remains accurate to view the Internet as a global network. Other participants noted that the Internet is not just creating challenges for regulation between states because of diminishing borders, but also within the national state bureaucracy. As regards the latter, the Internet has forced a change in the jurisdiction of certain agencies – for example, branches concerned with communication are now asking about their role in the privacy debate – and there is increasing strain placed on governments as these agency jurisdictions continue to blur.

The evolving security challenge

The growth of the Internet has been hugely disruptive to intelligence services. Disruption and encryption have bitten into traditional intelligence models. Agencies are now learning to embrace the Internet to deal with the evolving threats of terrorism and non-state actors. While acknowledging that bulk powers have their critics, one speaker expressed the view that the UK Investigatory Powers Act (2016) is modernizing how intelligence agencies collect evidence.

In the past, when government organizations thought about Internet security, they focused on the top 5 per cent of high-risk events, such as attacks on critical infrastructure. While potentially devastating, such attacks are rare compared with the constant barrage of cyber incidents affecting the population at large. As a result, governments are increasingly concerned with the Internet as it relates to civilian usage. Moreover, the evolution of the modern Internet has led to non-state actors, such as terrorists and hackers, posing security threats to states. Governments are still learning how to respect the privacy of individuals’ communications in the context of criminal investigations.

One participant noted that there has been a ‘market failure’ in security, and that citizens are not managing risks sufficiently. The UK government, for example, has responded at the national level by creating the National Cyber Security Centre.

The Internet of things

The Internet of things (IoT) also poses a big challenge to security. In the next 10 years an estimated 30 billion connected devices will come online. The growth in IoT marketing and innovation has outpaced security, and there are no good economic incentives in place to promote security. Many traditional companies that had nothing to do with information technology are now in effect becoming IT companies, but do not understand how their products can create vulnerability in the network. In this context, how do we continue to connect more devices and gadgets to the network without creating further vulnerability and insecurity? The second challenge around IoT and security pertains to data collection. Most of the focus for regulation is on visible – or physical – things, such as actual devices and gadgets. One participant suggested that as IoT exists in the cloud, that is where security and privacy solutions may be effective.

State regulation in a global world

One speaker described the present situation as a ‘Magna Carta moment’ – a general realization that ‘we don’t have the right structures to address the problems we’re facing’. ‘The nation state system of governance … for national and international and corporate governance are not fit for purpose to deal with the issues we’re facing.’ There is a need to bring together the right stakeholders to address the problems.

Other participants noted that regulation by the state can resolve many of the current problems, such as market failure around security.

When governments make local laws, they need to recognize that they are part of a broader, global system. Therefore, in one speaker’s view, governments need to be accountable not only to their own people, but to everyone on the network.

Others advocated less regulation, making the case instead for raising awareness of the opportunities the Internet brings. One participant asked if governments should be more visible in Internet regulation. Should there be a ‘complaints department’ for consumers at a national level, for example? Or should companies be forced to be more open by allowing algorithms to be reviewed by regulators to help prevent bias? Another noted that the media and the public sphere have become less transparent, and if the state does not play a part in regulating private companies, the data they collect, and the algorithms they operate, then there will be an imbalance.

Democracy and corporate power

Events in 2016 brought surprises in terms of democratic outcomes. Notably, following the Brexit referendum in the UK and the outcome of the US elections, many people are worried about the role of social media in creating filter bubbles and echo chambers, and in spreading fake news.

Extreme behaviour

One speaker raised the point that the vast majority of extreme behaviour is played out on two platforms with the largest user bases. There have been numerous attempts to develop norms of behaviour, or create technical solutions that could filter extreme material. It was only when advertisers started to abandon the platforms because they saw their brands being damaged by association that the platforms did anything about it.

The role of companies

While there has been increased transparency about how companies are responding to requests from governments for user data, there is little publicly available information about firms’ internal processes to moderate content on their platforms. Companies have done a good job in removing images of child abuse, for example, but a poor job in relation to images of breast feeding, or nudity in art. There is also a concern that, where governments are putting pressure on social media companies to take down allegedly extremist material, this may unjustifiably also target the work of human rights activists and journalists.

As recently as 2011, the discussion about the relationship between social media and democracy would have been very different. One participant noted that social networks were initially viewed as a democratizing force, but now the world is seeing the negative impacts that social media can have on society. One participant framed this as a transition from an ‘algorithm-less’ world to one that is ‘algorithm-full’. Another participant noted that, previously, the algorithms used to provide consumers of social media with information were often viewed as neutral. However, events in 2016 have changed people’s perspectives on how social media algorithms can create bias and perpetuate false information. Although the Internet feels like a public space, it is built on private infrastructure; and the companies that control these algorithms hold a great deal of unaccountable power.

Encoding values into the online environment

Just as the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) had to adapt to the internationalization of its membership by adopting a code of conduct, there is an urgent need to find an equivalent set of norms to enable ‘civilized’ debate online and reduce extreme behaviour.

While technical solutions seem attractive, it is important to be aware of both the opportunities and risks of encoding social values into algorithms, or into machines themselves. This process will reach its zenith with autonomy, but machine learning biases are already apparent. How can there be a distributed system that is secure, when security itself is a value judgment?

Legitimacy in the multi-stakeholder process

Internet governance began as a technical project but ended up in the world of policy. The technical community has often been very open and transparent, whereas government decisions are often made under conditions of confidentiality. In this context, questions were asked as to how we get these two very different communities to work together and within the confines of traditional institutions; and who should be responsible for convening this consultative space.

A new status quo

Intelligence services used to assume that the status quo would remain of the Internet as a global commons. This view was challenged in 2010, in light of a raft of proposals for new international laws, protocols and technologies designed to benefit authoritarian states. Since then, engagement through the Internet Governance Forum has been stronger; but a liberal, multi-stakeholder perspective is not guaranteed, and will need to be fought for.

Multi-stakeholder policies

Internet policy has become divorced from public-sector spending rounds in many countries, for example in the UK. In this context, multi-stakeholder policy can be undertaken, but only if it does not have a financial impact. One participant noted that discussions on Internet governance and enhanced cooperation tend to go round in circles. In other countries, such as in Malaysia or Kenya, progress on multi-stakeholder models has been reversed when governments have changed or instability has increased. It is unclear who the convenor of the open, consultative space is.

One speaker asserted that while the multi-stakeholder model is liberal, it is not democratic, and there is a danger that in certain environments only the ‘right sort’ of stakeholders are wanted. One participant argued that there is little legitimate input by civil society, whose voice has been crowded out. Another disagreed, noting that those who exert most influence are people who have gone beyond the normal range of effort to extend their expertise.

There is therefore a complex ‘ecosystem’, and different types of decision-making are needed for different problems online. One participant noted that the Internet community has reinforced how the multi-stakeholder model can work. But the role of the public and of civil society is important in demanding systematic change in how governments make decisions that affect the Internet.

What are the solutions to current and foreseeable challenges?

As one speaker remarked, there is not a ‘grand, top-down plan that we will suddenly innovate. It will evolve organically in a very “Internet-y” way.’

Possible solutions

International norms for behaviour and security.

Several speakers highlighted the need for norms of online behaviour and security. This challenge should not be underestimated. The collapse of place is something new, and this challenges the ability to hold separate value systems in different places – something that has previously been essential for successful international diplomacy.

Technical solutions to make visible the silent majority

Technology cannot solve problems of human behaviour, but the problems cannot be solved without technology. The knee-jerk reaction has been to call for unwanted material to be blocked, but the minute this starts, filter bubbles are created. An alternative approach may be to adopt public broadcast values – whereby all views are presented and consumers are necessarily confronted with a range of viewpoints. One speaker suggested that technology could be harnessed to track who reads discussions.

Accountability for corporate impact on human rights

One solution may be to develop benchmarks for companies to make commitments; for others to be able to assess whether those are the right sort of commitments; and to provide data that will enable policymakers, civil society, companies and investors to have a conversation about what sort of Internet is collectively wanted.

Hate speech and fake news

Several speakers agreed that organizations like the Internet Society could help by starting to have essential conversations around fake news, hate speech and extremist content.

Security and the Internet of things

Regulators need to consider who holds IoT data, and focus on the cloud rather than attempting to regulate every object that comes onto the market.

Progress is possible, but the risks are real

One speaker noted that many of the problems that are hotly debated in the context of Internet policy have affected humanity for generations. These problems arise from success not failure. Traditional institutions such as the judiciary have shown themselves to be able to deal with many issues. Previous leaps forward in human connectivity have also led to unprecedented human destruction. Nevertheless, progress has been made, and ‘humanity has evolved’. In the long run, things are improving, and there are great possibilities for innovation, development and human growth.

The developing world is hopeful

Speakers from the developing world emphasized that for many developing countries the Internet continues to be seen overwhelmingly as a medium of opportunity and empowerment. Although countries in the developing world understand that the Internet can impose challenges on society, they still feel that the Internet is the only existing medium that can efficiently provide effective solutions to issues such as poverty, marginalization and education. Some participants also noted that the acceleration of technology could lead to a deepening of existing inequalities, but asserted that this risk could be overcome through truly inclusive and participatory processes.

[1] When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.

The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017.

Related articles

Connectivity in the middle east and north africa.

This report investigates the developments of broadband infrastructure and Internet connectivity in the Middle East and North Africa until...

2024 West Africa Submarine Cable Outage Report

Learn about the West Africa submarine cable outage, and its impact on Internet connectivity in 13 countries.

How the Chippewas of Nawash are Bridging the Digital Divide

Sparrow McLeod, a Youth Worker Assistant in Neyaashiinigmiing, dropped out of high school because the lack of Internet connectivity...

- Corpus ID: 204375267

Change: 19 Key Essays on How Internet Is Changing our Lives

- M. Castells , D. Gelernter , +1 author E. Morozov

- Published 30 April 2014

- Computer Science, Sociology

16 Citations

Social and cultural sphere and the development of the digital economy, the european court of human rights: internet access as a means of receiving and imparting information and ideas, interpersonal communication in the information age: opportunities and disruptions.

- Highly Influenced

GLOBAL AND REMOTE COMMUNICATION

Minds online: the interface between web science, cognitive science and the philosophy of mind, messy or not: the role of education institutions in leading successful applications of digital technology in teaching and learning, explaining sociotechnical change: an unstable equilibrium perspective, issues in information systems, the governance of smart mobility, mothers knowledge and perception of toddler growth monitoring using iposyandu application, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Essay on Impact Of Internet On Our Life

Students are often asked to write an essay on Impact Of Internet On Our Life in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Impact Of Internet On Our Life

The introduction.

Internet, a global network, has significantly changed our lives. It has transformed how we learn, work, and interact with each other. It’s like a magic tool that has made our lives much easier and faster.

Learning and Education

The internet has changed the way we learn. With online classes and resources, students can learn from anywhere. They can access information on any topic, making learning more interesting and fun.

Communication

The internet has made communication easier and faster. We can talk to anyone, anywhere, anytime through emails, social media, or video calls. This has brought people closer and made the world a smaller place.

Work and Business

The internet has also affected how we work. Many people now work from home, thanks to the internet. It has also opened new opportunities for businesses to reach customers around the globe.

Entertainment

In conclusion, the internet has had a huge impact on our lives. It has made learning, communication, work, and entertainment easier and more accessible. It has truly transformed our lives.

250 Words Essay on Impact Of Internet On Our Life

Introduction.

The internet has changed our lives in many ways. It has become a big part of our daily routine. We use it for work, school, and fun. It’s hard to imagine life without the internet.

The internet has changed how we learn and get an education. Students can now study from home using online classes. They can also find information on any topic with just a few clicks. This has made learning more fun and easy.

Before the internet, talking to someone far away was difficult. Now, we can chat with friends and family from all over the world. We can also make new friends online. This has brought people closer together.

The internet is full of fun things to do. We can watch movies, listen to music, and play games. We can also share our own videos and pictures. This has given us new ways to have fun and be creative.

The internet has had a big impact on our lives. It has changed how we learn, communicate, have fun, and shop. Life without the internet would be very different. The internet has made our lives better in many ways. It’s a tool that we use every day to make our lives easier and more fun.

500 Words Essay on Impact Of Internet On Our Life

The internet has become an essential part of our lives. Just like food and water, we need it every day. It helps us in many ways and has changed our lives completely. Let’s talk about how the internet has impacted our lives.

The internet has made it easy to talk to people far away. We can send messages, make video calls, and even work together on projects online. This has brought us closer to our friends and family who live in different places. It has also made it easier for us to make new friends from all over the world.

The internet is a great place for fun and games. We can watch movies, listen to music, play games, and even read books online. It has also made it easy to share our own fun moments with others. For example, we can post photos and videos of our vacations or special events.

In conclusion, the internet has had a big impact on our lives. It has changed how we learn, communicate, have fun, and shop. It has made our lives easier and more exciting. But it is also important to use the internet wisely. We should be careful about what we share online and make sure we are safe. The internet is a powerful tool, and we should use it to make our lives better.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Arts & Photography

- History & Criticism

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Change: 19 Key Essays on How Internet Is Changing our Lives Paperback – April 30, 2014

- Print length 478 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Turner

- Publication date April 30, 2014

- Dimensions 7.5 x 1.3 x 9.8 inches

- ISBN-10 8415832451

- ISBN-13 978-8415832454

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Turner (April 30, 2014)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 478 pages

- ISBN-10 : 8415832451

- ISBN-13 : 978-8415832454

- Item Weight : 2.63 pounds

- Dimensions : 7.5 x 1.3 x 9.8 inches

- #11,272 in Internet & Telecommunications

- #18,926 in Popular Culture in Social Sciences

- #23,910 in Arts & Photography Criticism

Customer reviews

| 5 star | 0% | |

| 4 star | 0% | |

| 3 star | 0% | |

| 2 star | 0% | |

| 1 star | 0% |

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The internet: History, evolution and how it works

The Internet is a massive computer network that has revolutionized communication and changed the world forever.

What is the internet?

- Internet invention

- How it works

How do websites work?

- Speed and bandwidth

Additional resources

Bibliography.

The internet is a vast network that connects computers across the world via more than 750,000 miles (1,200,000 kilometres) of cable running under land and sea, according to the University of Colorado Boulder.

It is the world's fastest method of communication, making it possible to send data from London, U.K. to Sydney, Australia in just 250 milliseconds, for example. Constructing and maintaining the internet has been a monumental feat of ingenuity.

The internet is a giant computer network, linking billions of machines together by underground and underwater fibre-optic cables.These cables run connect continents and islands , everywhere except Antarctica

Each cable contains strands of glass that transmit data as pulses of light, according to the journal Science . Those strands are wrapped in layers of insulation and buried beneath the sea floor by ships carrying specialist ploughs. This helps to protect them from everything from corrosion to shark bites.

When you use it, your computer or device sends messages via these cables asking to access data stored on other machines. When accessing the internet, most people will be using the world wide web.

When was the internet invented?

It was originally created by the U.S. government during the Cold War . In 1958, President Eisenhower founded the Advanced Research Projects Agency ( ARPA ) to give a boost to the country’s military technology, according to the Journal of Cyber Policy . Scientists and engineers developed a network of linked computers called ARPANET.

- The Internet of Things: A seamless network of everyday objects

- What is cyberwarfare?

- Internet history timeline: ARPANET to the World Wide Web

ARPANET's original aim was to link two computers in different places, enabling them to share data. That dream became a reality in 1969, according to Historian Jeremy Norman . In the years that followed, the team linked dozens of computers together and, by the end of the 1980s, the network contained more than 30,000 machines, according to the U.K.'s Science and Media Museum .

How the onternet works

Most computers connect to the internet without the use of wires, using Wi-Fi , via a physical modem. It connects via a wire to a socket in the wall, which links to a box outside. That box connects via still more wires to a network of cables under the ground. Together, they convert radio waves to electrical signals to fibre optic pulses, and back again.

At every connection point in the underground network, there are junction boxes called routers. Their job is to work out the best way to pass data from your computer to the computer with which you’re trying to connect. According to the IEEE International Conference on Communications , they use your IP addresses to work out where the data should go. Latency is the technical word that describes how long it takes data to get from one place to another, according to Frontier .

Each router is only connected to its local network. If a message arrives for a computer that the router doesn’t recognizse, it passes it on to a router higher up in the local network. They each maintain an address book called a routing table . According to the Internet Protocol Journal , it shows the paths through the network to all the local IP addresses.

The internet sends data around the world, across land and sea, as displayed on the Submarine Cable Map . The data passes between networks until it reaches the one closest to its destination. Then, it passes through local routers until it arrives at the computer with the matching IP address.

The internet relies upon the two connecting computers speaking the same digital language. To achieve this, there is a set of rules called the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP), according to the web infrastructure and website security company Cloudflare .

TCP/IP makes the internet work a bit like a postal system. There is an address book that contains the identity of every device on the network, and a set of standard envelopes for packaging up data. The envelopes must carry the address of the sender, the address of the recipient, and details about the information packed inside. The IP, explains how the address system works, whileTCP, how to package and send the data.

Click the numbers on the following interactive image to find out what happens when you type www.livescience.com into your browser:

Internet speed and bandwidth

When it comes to internet speed how much data you can download in one second: bandwidth. According to Tom’s Guide , to surf the web, check your email, and update your social media, 25 megabits per second is enough. But, if you want to watch 4K movies, live stream video, or play online multiplayer games, you might need speeds of up to 100-200 megabits per second.

Your download speed depends on one main factor: the quality of the underground cables that link you to the rest of the world. Fibre optic cables send data much faster than their copper counterparts, according to the cable testing company BASEC , and your home internet is limited by the infrastructure available in your area.

Jersey has the highest average bandwidth in the world, according to Cable.co.uk . The little British island off the coast of France boasts average download speeds of over 274 megabits per second. Turkmenistan has the lowest, with download speeds barely reaching 0.5 megabits per second.

You can read more about the history of the internet at the Internet Society website . To discover how the Internet has changed our daily lives, read this article by Computing Australia .

- " Getting to the bottom of the internet’s carbon footprint ". University of Colorado Boulder, College of Media, Communication and Information (2021).

- " The evolution of the Internet: from military experiment to General Purpose Technology ". Journal of Cyber Policy (2016).

- " The Internet: Past, Present, and Future ". Educational Technology (1997).

- " Three-Way Handshake ". CISSP Study Guide (Second Edition) (2012).

- " Content Routers: Fetching Data on Network Path ". IEEE International Conference on Communications (2011).

- " Analyzing the Internet's BGP Routing Table ". The Internet Protocol Journal (2001).

- " The Internet of Tomorrow ". Science (1999).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura Mears is a biologist who left the confines of the lab for the rigours of an office desk as a keen science writer and a full-time software engineer. Laura has previously written for the magazines How It Works and T3 . Laura's main interests include science, technology and video games.

Follow Live Science on social media

Live Science daily newsletter: Get amazing science every day

This robot could leap higher than the Statue of Liberty — if we ever build it properly

Most Popular

- 2 'Space potato' spotted by NASA Mars satellite is actually something much cooler

- 3 Earth's rotating inner core is starting to slow down — and it could alter the length of our days

- 4 'Exceptional' discovery reveals more than 30 ancient Egyptian tombs built into hillside

- 5 What defines a species? Inside the fierce debate that's rocking biology to its core

- 2 2,000-year-old Roman military sandal with nails for traction found in Germany

- 3 James Webb Space Telescope spies strange shapes above Jupiter's Great Red Spot

- 4 Shattered Russian satellite forces ISS astronauts to take shelter in stricken Starliner capsule

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The Internet and the Pandemic

- 1. How the internet and technology shaped Americans’ personal experiences amid COVID-19

Table of Contents

- 2. Parents, their children and school during the pandemic

- 3. Navigating technological challenges

- 4. The role of technology in COVID-19 vaccine registration

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

As the pandemic unfolded in spring 2020, many Americans saw their lives swiftly reshaped by stay-at-home orders , school closures and the onset of remote work . From video calls with isolating or sick family members to holiday celebrations by video call amid canceled travel plans , social distancing recommendations altered major life events and elements of daily life alike.

Technology bridged physical distance as restrictions continued. Religious services , doctor appointments and essential errands moved online. At the same time, organizations implementing remote work and Americans spending more time online worried about “ Zoom fatigue ” and tech burnout.

Relationships also evolved during this uprooting of typical routines. Pandemic “pods” helped some Americans maintain connection , but they complicated relationships and family dynamics at the same time. In some cases, friendships relied on technology to stay afloat. And others needed to find new ways to connect amid growing isolation .

With this broader societal context in mind, this chapter explores the ways in which Americans’ lives changed in the pandemic – and the ways that technology was a part of several transitions. Results from the April 2021 Pew Research Center survey show that even as a majority of Americans considered the internet essential to them personally during the pandemic and four-in-ten used tech in new ways, some feel worn out or fatigued from video calls and a quarter feel less close to close family members than before the coronavirus outbreak. The following sections explore these findings.

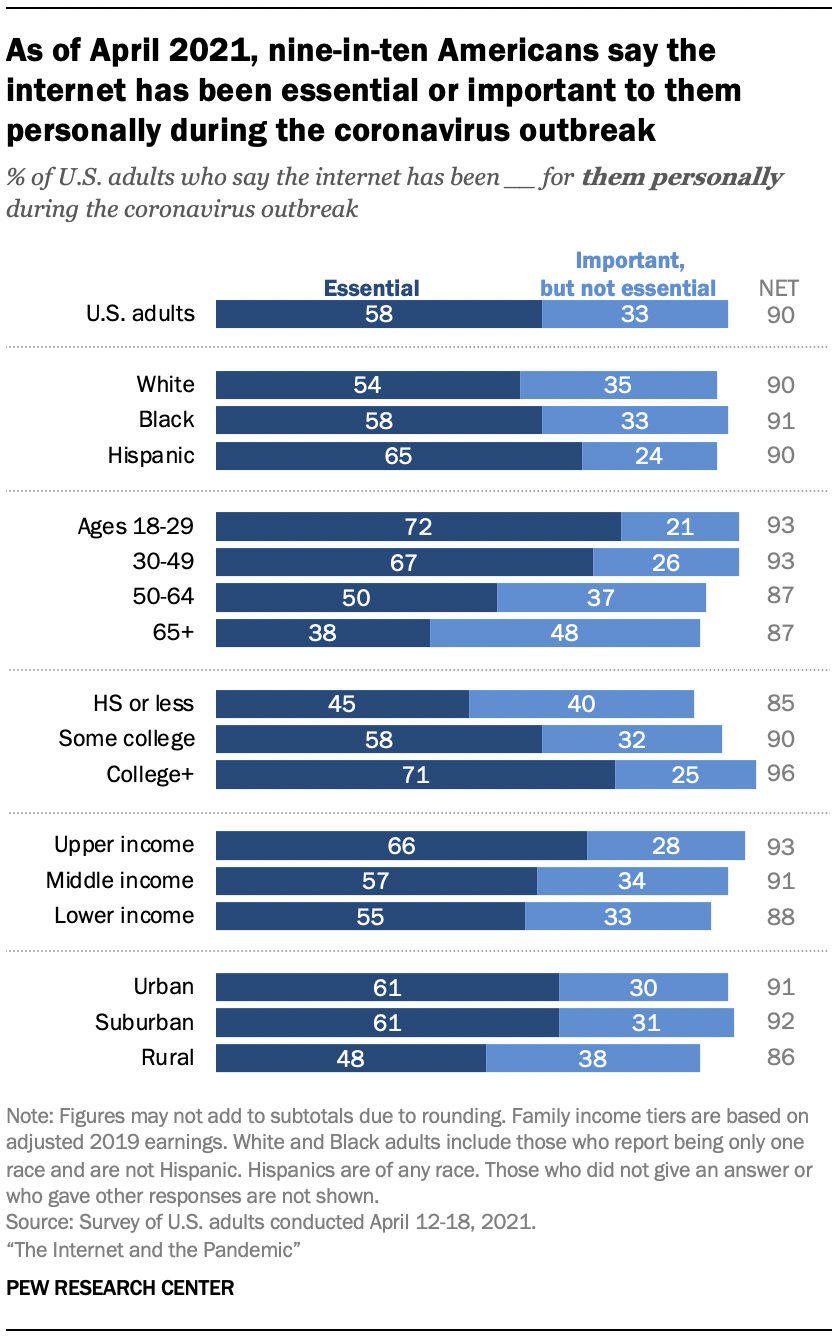

58% of adults say the internet has been essential during the pandemic, and for some groups, its importance grew over the past year

The share of Americans who describe the internet as essential for them during the pandemic has risen slightly over the past year. As of April 2021, 58% of U.S. adults say this, compared with 53% in an April 2020 Center survey.

Americans varied in their reliance on the internet and some of the key differences relate to age, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, income and community type. For example, roughly seven-in-ten adults ages 18 to 49 (69%) say the internet has been essential to them personally, compared with half of those ages 50 to 64 and about four-in-ten Americans 65 and older.

Additionally, about six-in-ten of those living in urban or suburban areas (61% each) say the internet has been essential to them, compared with a smaller share of those living in rural locales (48%) who say the same. While at least half of adults across major racial and ethnic groups say this connectivity has been essential, Hispanic adults (65%) are more likely to say so than White adults (54%). Some 58% of Black Americans say the internet has been essential in this way.

Several of the groups that are less likely to say the internet has been essential also have lower rates of home broadband adoption and smartphone access, according to other Center research . For example, digital divides have persisted in recent years even as Americans with lower incomes have made gains in tech adoption. And as of 2021, a quarter of U.S. adults 65 and older say they do not use the internet .

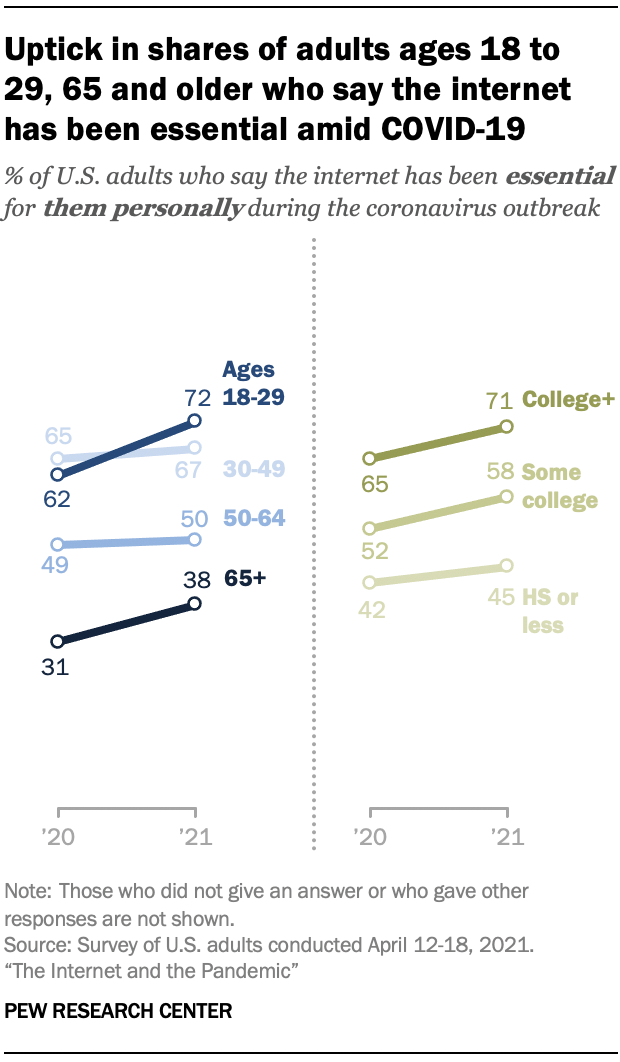

For some groups, the importance of the internet has grown over the past year – especially when it comes to age and educational attainment. The share of adults ages 18 to 29 who say it has been essential during the pandemic rose 10 percentage points between April 2020 and April 2021. Similarly, roughly four-in-ten adults 65 and older (38%) now say the internet has been essential to them, compared with about three-in-ten who said so in April 2020.

Americans with higher levels of educational attainment are more likely today than a year ago to say the internet has been essential to them during the pandemic. For example, 71% of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree say this, up from 65% in 2020. This uptick also appears for those with some college experience, while sentiments among those with a high school education or less have remained stable.

Looking at older Americans specifically, adults ages 65 and older with a bachelor’s degree or more education are more likely now to say the internet has been essential to them personally (50% say so) compared with a year ago (39%) – an 11 percentage point increase. By contrast, among those 65 and older who have less education, the shares saying it has been essential are similar between the two time points (27% in 2020 and 32% in 2021).

Adults ages 50 to 64 with a bachelor’s or advanced degree are also more likely now to say the internet has been personally essential (a 7-point increase since 2020), while there has been no change for those in that age group with less formal education.

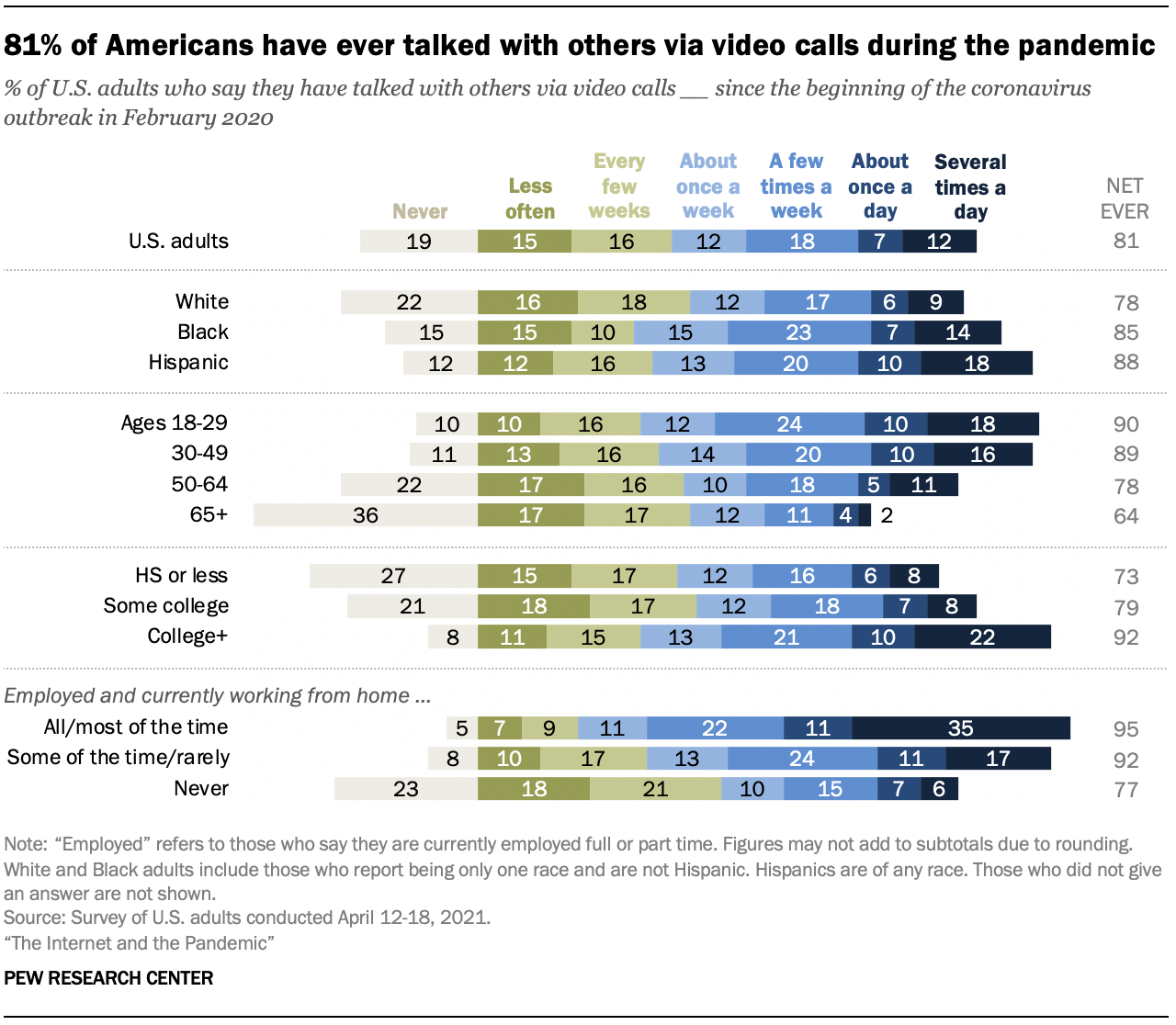

81% of Americans have used video calling and conferencing during the pandemic

As Americans increasingly lived their lives from home, video calling and conferencing platforms became a venue for everything from celebrating holidays with family and friends to conducting remote meetings or visiting doctors .

Roughly eight-in-ten Americans (81%) say they have talked with others via video calls since the beginning of the pandemic. One-in-five have done so about once a day or more often, including 12% who say they are on video calls several times a day. Another three-in-ten have done this about once a week (12%) or a few times a week (18%), and a similar share use video calls every few weeks (16%) or less often (15%).

While there are many ways people can spend their time on video calls, the survey finds that working from home is particularly associated with this type of screen time.

In this survey, 17% of Americans say they were employed full or part time and working from home all or most of the time as of April. 7 Among them, 46% say they have used video calling about daily or several times a day during the pandemic. Another 12% of the full adult population was employed full or part time and working from home some of the time or rarely at the time of the survey. Among that group, 28% say they have used video calling about daily or more. And among the 28% of U.S. adults who were working but never from home, 13% say they are on daily or more frequent video calls.

Aside from work-from-home status, how often people use video calls varies by several other demographics. Black and Hispanic adults are more likely to have used video calling than White adults. Hispanic adults are more likely than White Americans to have done so several times a day or about daily. Meanwhile, while about two-thirds of adults 65 and older have made video calls in the pandemic, daily use is more common among younger adults. About a quarter of those 18 to 29 (28%) and 30 to 49 (26%) say they have done this about daily or more often, compared with 16% of those 50 to 64 and 7% of adults 65 and older.

Frequency of video calling varies by education as well. About a third of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree say they have done this at least once a day, compared with smaller shares of those with less formal education.

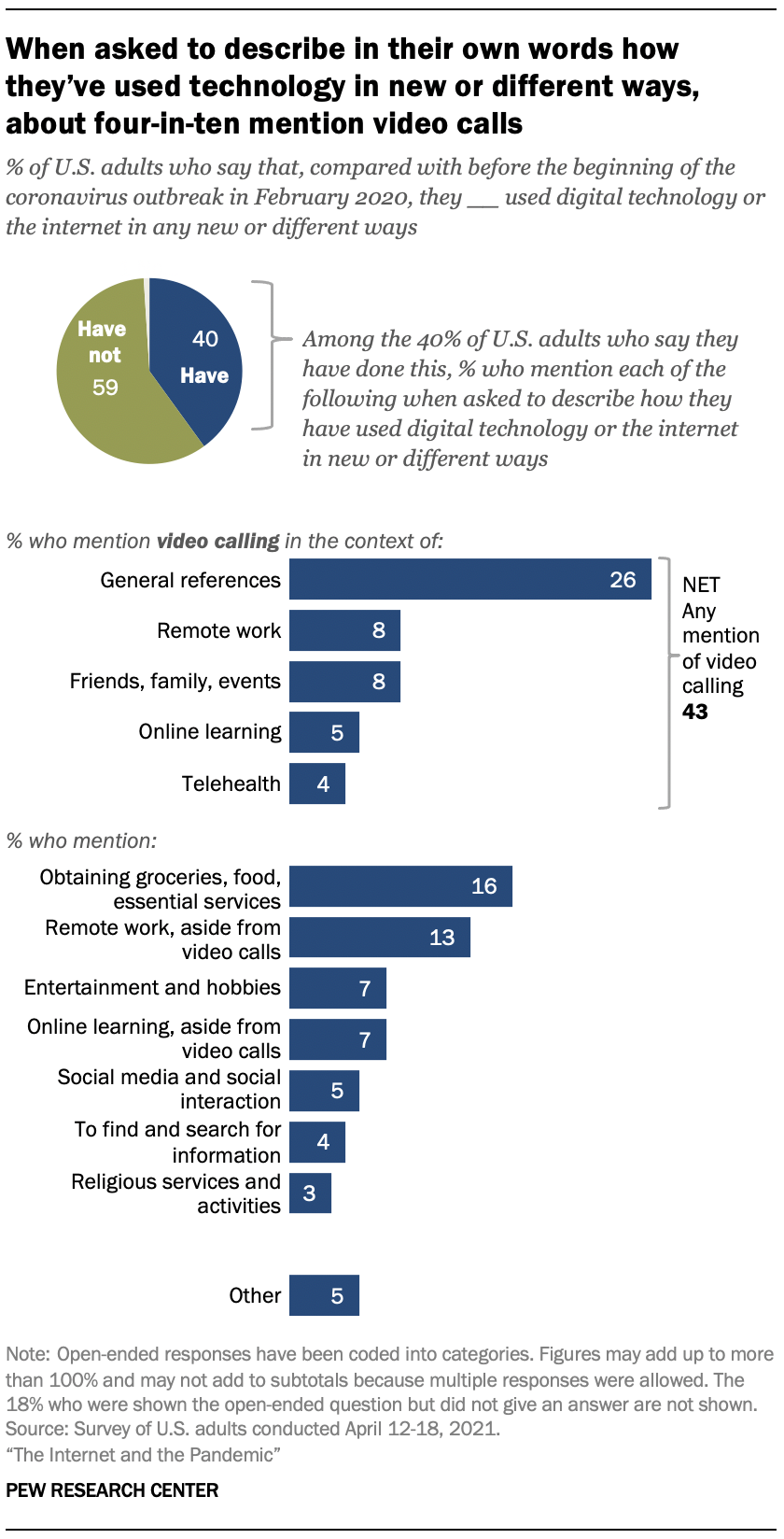

In their own words, Americans describe how they have used technology or the internet in new or different ways during the pandemic

As the severity of the pandemic grew, some Americans were faced with performing everything from their social interactions to their work or schooling online. Four-in-ten Americans say they used digital technology or the internet in new or different ways compared with before the outbreak began. Still, an even larger share – 59% – say their tech use has not changed in this way.

As is the case with digital divides in internet use and tech adoption in general, those with more formal education and higher incomes are more likely to have had new or different experiences with tech in the pandemic. For example, 56% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree say they have used technology in ways new or different to them, compared with 37% of those with some college experience and 29% of those with a high school diploma or less. Similarly, 46% of those with higher household incomes say so, compared with a smaller share of those with lower (38%) or middle incomes (40%).

Women are also more likely than men to say they have used digital technology or the internet in new and different ways (43% vs. 36%), as are adults under 50 (46%) compared with those who are 50 and older (33%).

When asked to describe what these new and different ways are, 43% mention encountering at least one form of video calls or conferences new to them in the pandemic. From weddings to funerals, church meetings to calls with family, some of these adults report their lives moved largely onto video platforms:

“We now hold bi-weekly family meetings on Zoom to make sure we are all doing okay. Before we just had individual phone calls with family members. We used Vimeo for my mother’s funeral so people could watch her funeral mass. She died of COVID-19. I used Zoom for work meetings.” – Woman, 57

“[I have had] Zoom meetings [and] Microsoft Teams meetings. [I’ve had] increased FaceTime family meetings. [I had] job interviews via the internet.” – Man, 46

“[I have been] teaching writing classes over Zoom [and I] dated someone over FaceTime for 3 months. [I] attended various online events.” – Woman, 24

While about a quarter of Americans who have used tech in new ways mention video calls generally, roughly one-in-ten (8%) referenced the remote work aspect of video conferencing specifically:

“Most of my work-related meetings are no longer in-person, but on Zoom or Teams. Instead of attending professional conferences in person, all of them are now virtual meetings. It took a bit to get comfortable with such drastic change.” – Man, 63

A similar share (8%) talk about using video calling to connect with family and friends, or attend social events or “video holidays”:

“It has opened me up to using video chat to connect with physically distanced friends. I have people that I used to only see on Facebook or in person two times a year but now we do a group video chat once a month and I am closer to them than ever.” – Woman, 39

Smaller shares discuss the move to online learning and the use of video platforms (5%) or using video calls for telehealth (4%):

“[I] had to learn how to use Google Classroom to help my son with his hybrid learning. I also did my first tele-visit with my GP doctor and I am disabled so it turns out I’ll be able to continue to use that technology once the pandemic is over to make it easier! … Not to mention, I’ve attended various social gatherings that, due to my disability, I wouldn’t have been able to attend under normal circumstances!” – Man, 28

Aside from video calls, 16% of Americans said they have used technology or the internet to obtain groceries, food or other essentials, or to perform services like banking or document signing:

“Shopping (especially groceries and home supplies) online through various different places, permanently eliminating the need to physically go to the grocery store for most shopping activities.” – Man, 42

“Ordering groceries, ordering tags for my car, doctor’s appointments, paying insurance premiums, paying bills and keeping in touch with family and friends.” – Woman, 78

In addition to those who mention remote work and online learning in the context of video calls, another 13% mention using technology in new ways for remote work and another 7% for online learning:

“Before the outbreak, I was the typical pen and paper type of middle school math teacher. After the outbreak, I have become a much more proficient virtual math teacher who has embraced many new platforms [that] have made my job easier. I have recently become fully vaccinated and returned to the brick and mortar school environment, but will maintain many of the new skills which I learned virtually.” – Man, 62

“We needed to get the internet for our granddaughter to be able to get her education while she’s home during the pandemic.” – Woman, 53

Others specifically note how they are now relying on the strength or quality of their connection in a new way:

“I upgraded my internet (was just using a hotspot previously) and for my work, I am connected all day through the workday. If the internet goes down, my ability to work at home decreases significantly. Before the work from home started, if I lost the ability to connect to the internet, it only affected me in terms of annoyance at not being able to surf the net.” – Woman, 50

Finally, other Americans have used social media and other technology for entertainment (7%), to keep up social interaction, especially on social media (5%), to find and search for information (4%), or attend online religious services or activities (3%). And their use of these digital technologies has sometimes changed over the course of the pandemic.

“I never really used Twitter before. Now I follow some important public health figures and medical doctors who are working for the CDC, etc., so I can be informed on what is going on with COVID-19 and treatment options.” – Woman, 53

“Pre-COVID-19 and even well into the pandemic, I was using the internet/my smartphone to spend countless hours on social media. Somewhere in there I deleted most of the social media apps from my phone and have been using it to read e-books and plan creative projects, mostly home improvements.” – Woman, 34

“I now attend church services online rather than in person, which I had not done before the outbreak.” – Man, 36

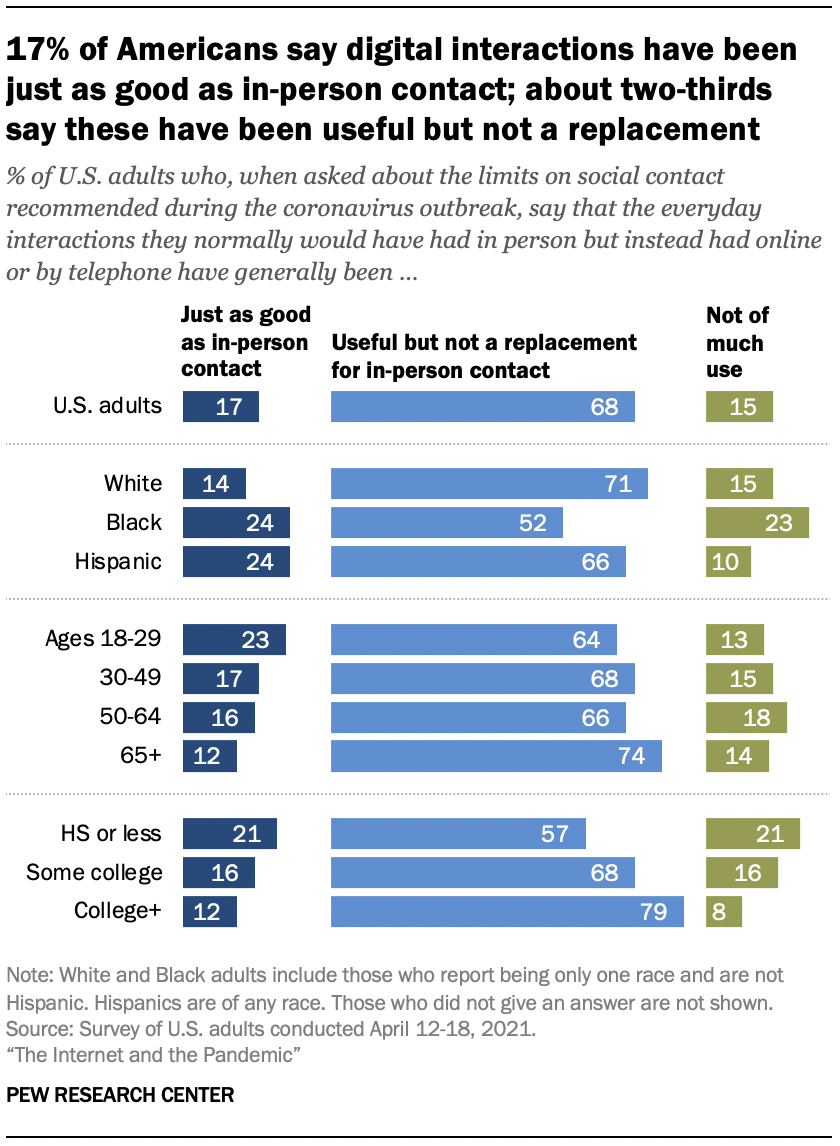

68% of Americans say digital interactions have been useful – but not a replacement for in-person connection

In late March 2020, as stay-at home orders upended American life, a Center survey asked U.S. adults to speculate on whether digital interactions – that is, everyday interactions that might have to be done online or by telephone because of recommended limits on social contact during the coronavirus outbreak – would be suitable replacement for in-person contact. At the time, about a quarter of Americans said digital encounters would be just as good (27%), and 8% believed that they wouldn’t be of much help. Some 64% said they would be useful, but not a replacement.

In this new survey, Americans were asked to assess how digital encounters used to replace social contact have actually gone. When asked to think about everyday interactions that happened online or by telephone rather than in person, 17% say that these have been just as good as in-person contact. In line with Americans’ own expectations a year ago, the majority of Americans – 68% – say that interactions that have moved online or to the phone have been useful, but not a replacement for in-person. Some 15% say these interactions haven’t been of much use.

Considering the more recent findings about people’s experiences, relatively small shares across demographic groups say these types of digital interactions have been just as good as in-person contact. Still, there are some small differences by race and ethnicity, age and formal educational attainment in this respect. Adults ages 18 to 29 were more skeptical than older adults in March 2020 – 21% said these interactions would be just as good as in-person contact, compared with a somewhat larger share (29%) of Americans 65 and older. In the new survey, some 23% of adults ages 18 to 29 say these interactions have been just as good as in-person contact, while a smaller share (12%) of those 65 and older who feel this way about the utility of their digital interactions.

In March 2020, Black adults were more likely than White adults to think digital interactions would be just as good as in-person contact. Black and Hispanic adults are also more likely than White adults to say these interactions have been just as good in the new survey. At the same time, about another quarter of Black adults say that these digital interactions have not been of much use. Smaller shares of White and Hispanic adults say the same.

Both then and now, how useful Americans say these interactions have been also varies by educational attainment.

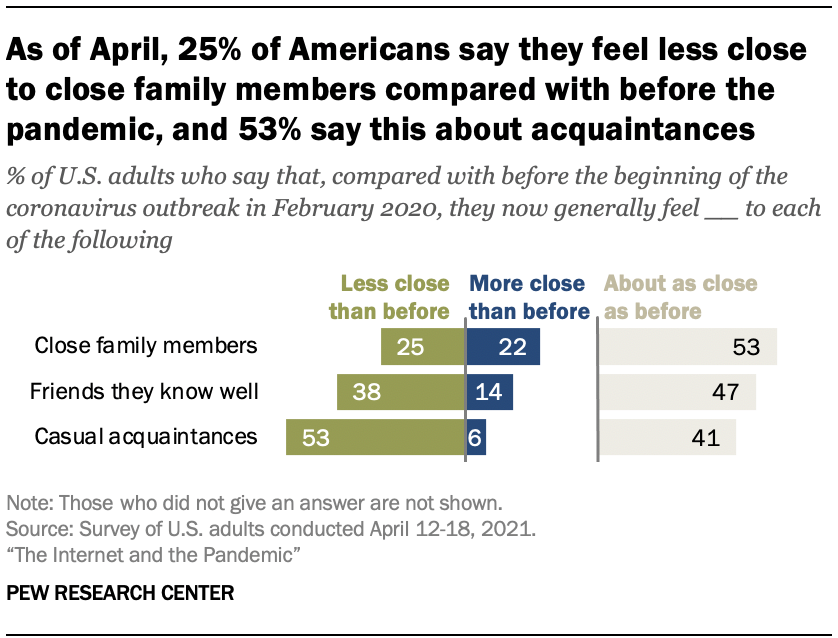

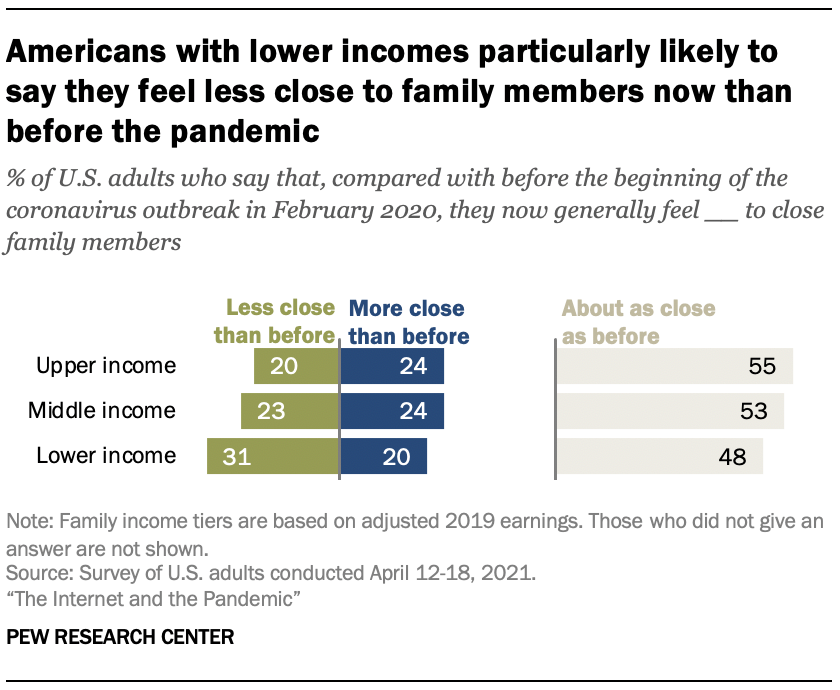

A quarter of Americans feel less close to close family members than before pandemic; about four-in-ten say the same about friends they know well

Some accounts of the pandemic have lamented the potential loss of casual friendships and acquaintances as COVID-19 narrowed people’s social circles and family structures into smaller bubbles . At the same time, some living with friends or family members may have faced increased time spent together as stay-at-home orders were imposed to combat COVID-19. Others living alone faced possible challenges of staying in touch with those close to them.

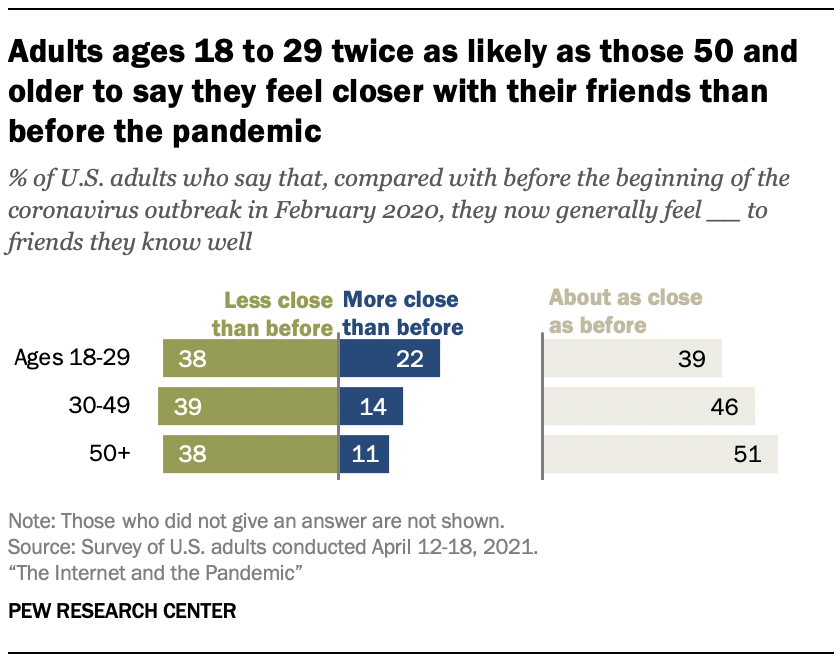

The new survey reveals that some people feel their social relationships and their connections to those in their personal networks have been in flux during the pandemic. About half of Americans (53%) say they feel less close to casual acquaintances compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak in February 2020. Some 38% say the same about friends they know well. And a quarter of Americans say they now feel less close to close family members.

At the same time, about one fifth of adults (22%) say they feel more close to close family members than they did before the pandemic. Smaller shares say this about friends they know well and casual acquaintances.

And despite the pandemic upheaval, about half say their relationships with close family members (53%) and friends they know well (47%) have stayed about as close as before, while roughly four-in-ten (41%) say this about casual acquaintances.

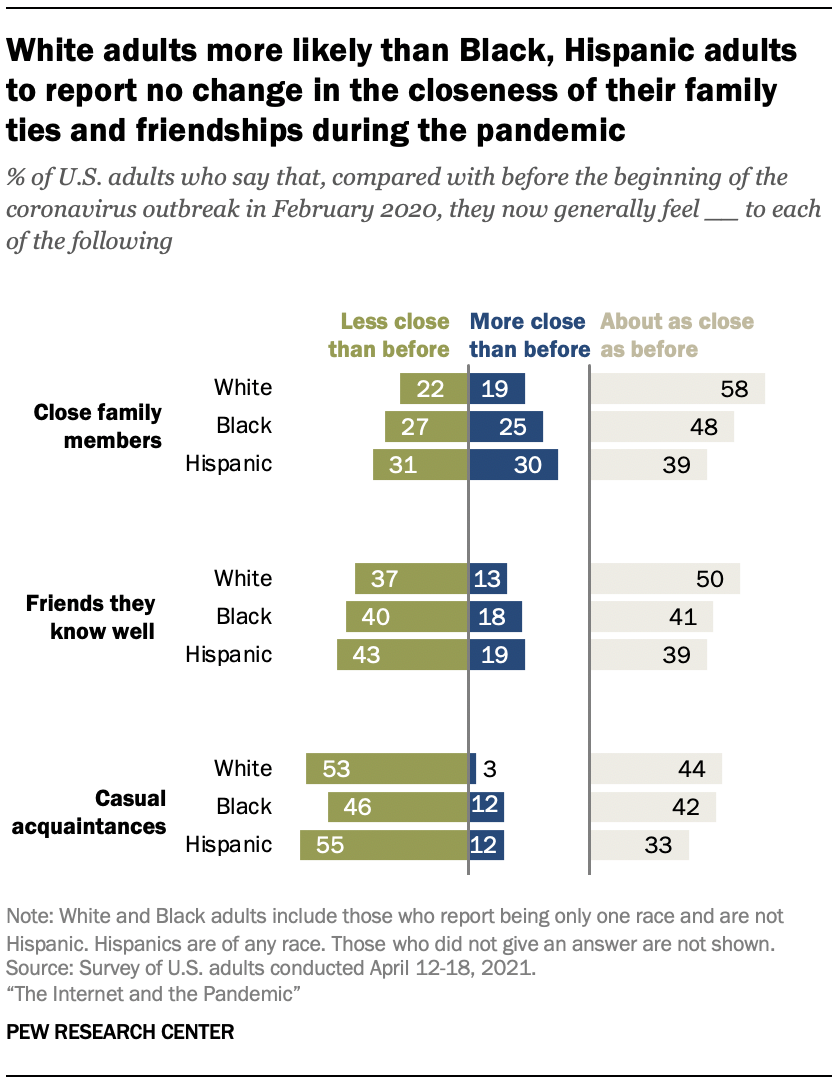

Some groups are more likely to report change in the closeness of their relationships than others. Hispanic and Black adults are less likely than White adults to say the closeness of their relationships with close family and friends has stayed about the same compared with before the beginning of the pandemic.

When it comes to close family members, similar shares of Hispanic adults say these relationships feel closer than before (30%) and less close than before (31%). Compared with White adults, they are also more likely to say they feel closer to close family, and friends they know well.

Americans with lower incomes are also more likely than others to say they feel less close to close family members compared with before the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak. About three-in-ten of those with lower incomes say so. At the same time, a fifth of Americans with lower incomes say they feel more close to close family, and 48% say they feel about as close to these family members as before the pandemic.

There is little difference in how Americans in various age groups describe the pandemic’s impact on closeness of their family relationships. But when it comes to friends they know well, young adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely to say they now feel closer to these friends than those in any other age group. Still, only about a fifth (22%) of young adults say so.

Finally, small shares of adults across gender, racial and ethnic, age and income groups say they feel closer to casual acquaintances than they did before – no more than about one-in-ten across any of these groups. In each case, far larger shares say they feel less close now.

Women are slightly more likely than men to say they feel less close to acquaintances, as are Americans with lower incomes compared with those in the upper-income tier. Those who live in urban (57%) or suburban (54%) areas are more likely to say their relationships with casual acquaintances are less close now, compared with those who live in rural areas (46%).

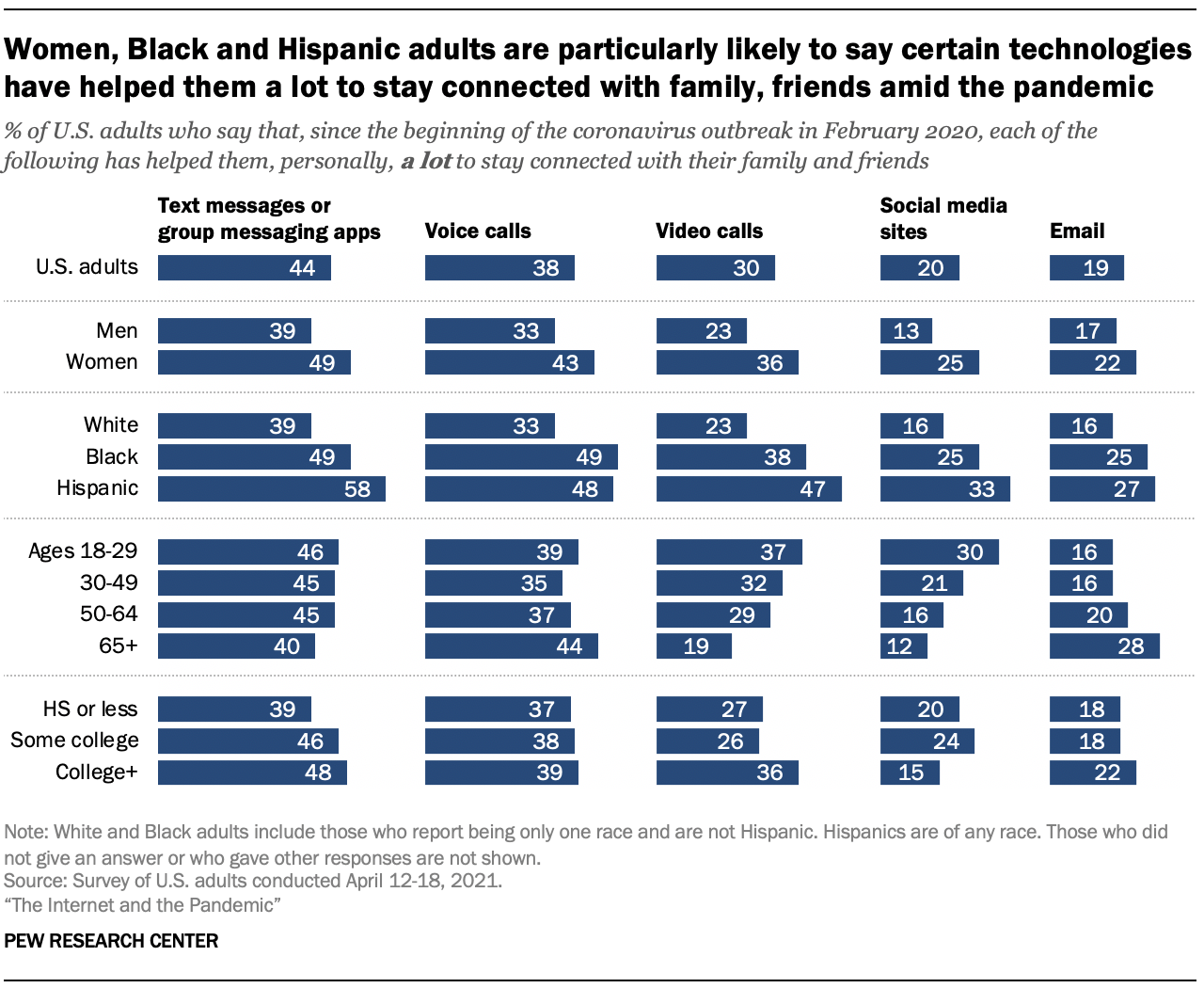

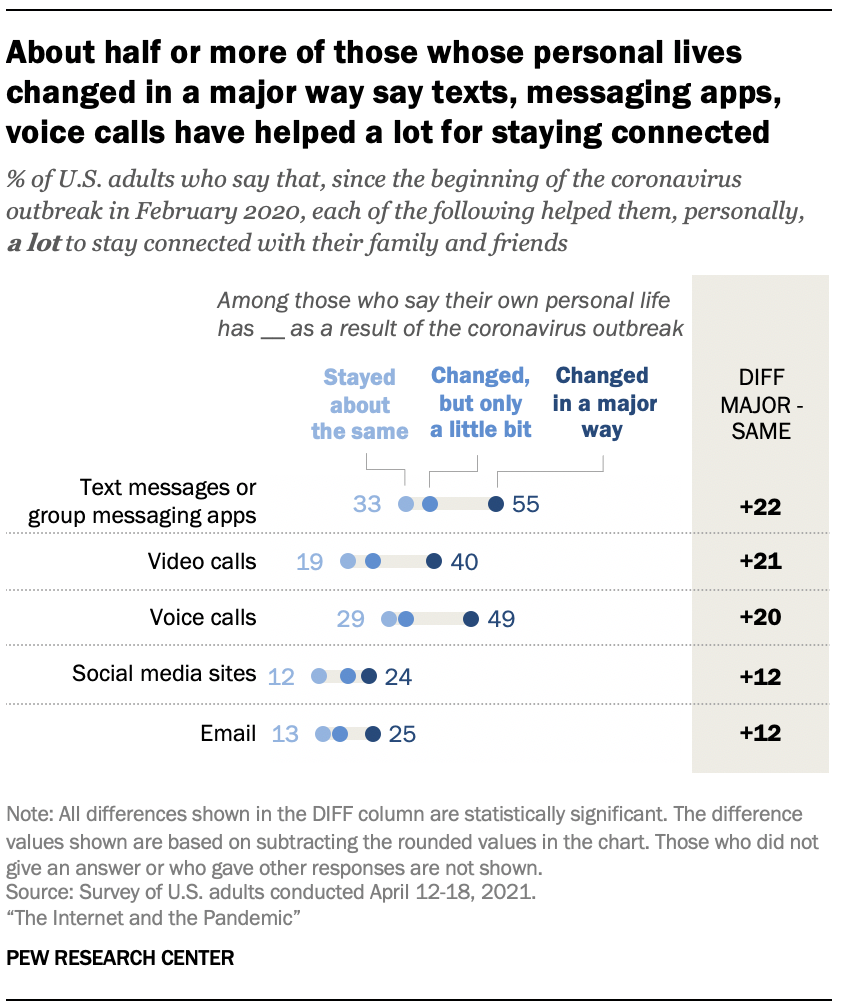

Majorities say texts or group messaging apps, voice and video calls have helped them at least a little to stay connected to family and friends

For some, technology became a way to stay in touch with others whom they could not visit in person since the pandemic began. About seven-in-ten Americans say text messages or group messaging apps have helped them personally to stay connected with their family and friends at least a little. Roughly six-in-ten or more say the same about voice (65%) and video calls (59%). Smaller shares say this about social media sites or email.

Americans’ reliance on technology early in the pandemic was apparent in several ways, from using technology to communicate with others to hosting virtual gatherings . Over a year into the pandemic, results from the new survey show that key communications platforms have been more likely to be helpful for some groups than others.

For each of the five technologies asked about in the survey, Black and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say these technologies have helped them a lot to stay connected. For example, 58% of Hispanic adults say that text messages or group messaging apps have helped them a lot, personally, to stay connected with their family and friends. Some 49% of Black adults and a smaller share (39%) of White adults say the same. Voice calls have helped about half of Black and Hispanic adults a lot to stay in touch, compared with a third of White adults. Similar patterns hold for video calls, social media sites and email.

There are also differences by gender, with women being more likely than men to say that each of these technologies have helped them a lot to stay connected to friends and family.

Adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those 65 and older to say video calls and social media sites have helped a lot in staying connected with family and friends.

The reverse is true for email: Some 28% of Americans 65 and older say that this has helped them a lot to stay in touch, compared with smaller shares of younger Americans. Those 65 and older are also more likely than those 30 to 64 to say voice calls have helped a lot.

Other technologies – for example, text messages or group messaging apps – have been similarly helpful for Americans across age groups. Across age groups, four-in-ten or more Americans say these have helped a lot with staying in touch.

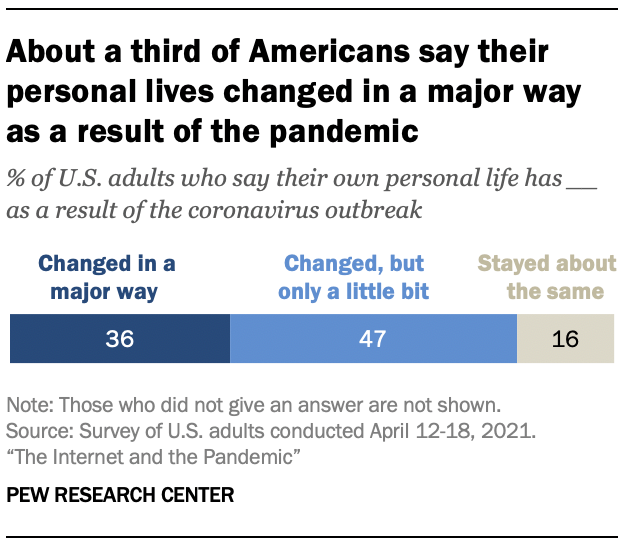

36% of Americans say their personal lives changed in a major way

As context for this exploration of how people’s technology use and experiences were affected by the pandemic, the survey also asked Americans about the overall impact of the pandemic on their personal lives.

Some 36% of Americans say their own personal life has changed in a major way as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Another 47% say their personal life has changed, but only a little bit. And 16% say that it has stayed about the same as it was before the outbreak.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to say life has changed in a major way (39% vs. 33%), as are those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree (40%) compared with those with some college (35%) or a high school diploma or less formal education (34%). And Americans living in urban (41%) and suburban areas (37%) are more likely to say this than those living in rural areas (30%).

About half of those who say their personal lives have changed in a major way (52%) say they have used technology in new ways during the pandemic, compared with 38% of those who say their personal lives have changed a little bit and 19% of those who say life stayed about the same. At the same time, roughly seven-in-ten Americans reporting major changes in life (73%) or with more modest levels of change (69%) say digital interactions have been useful, but not a replacement for in-person interactions, compared with a smaller share among those who say their personal lives stayed about the same (52%).

Those who say their lives stayed about the same are also more likely than others to say interactions they have had online or by phone instead of in person haven’t been of much use: 26% of these adults think these virtual interactions haven’t been useful, compared with smaller shares of those who say their personal lives changed a little bit (14%) or in a major way (11%).

At the same time, those who say their lives have changed in a major way are more likely to say each of the five technologies asked about in the survey helped a lot to keep them connected, compared with those who say their lives have changed a little or stayed about the same.

Among those who said their personal lives have changed in a major way, the shares who say text messages or group messaging apps, video calls or voice calls have helped a lot are roughly 20 points higher compared with those who say their lives stayed about the same. About half or more of those who say their personal lives have changed in a major way say text messages or group messaging apps (55%) or voice calls (49%) helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends, and 40% say the same about video calls.

Those who say their lives have changed in a major way are also more likely to say they now feel less close to close family members (35%) than those whose lives changed only a little (22%) or stayed about the same (9%). And about half (53%) of those with major change in this aspect of their life say their relationships with friends they know well are now less close.

The diminishing closeness of casual relationships is especially prominent for those whose personal lives COVID-19 changed profoundly – roughly seven-in-ten (69%) of adults with major change say that they now generally feel less close to casual acquaintances. By comparison, about a quarter (26%) of those whose personal lives stayed about the same say they feel less close to these acquaintances now.

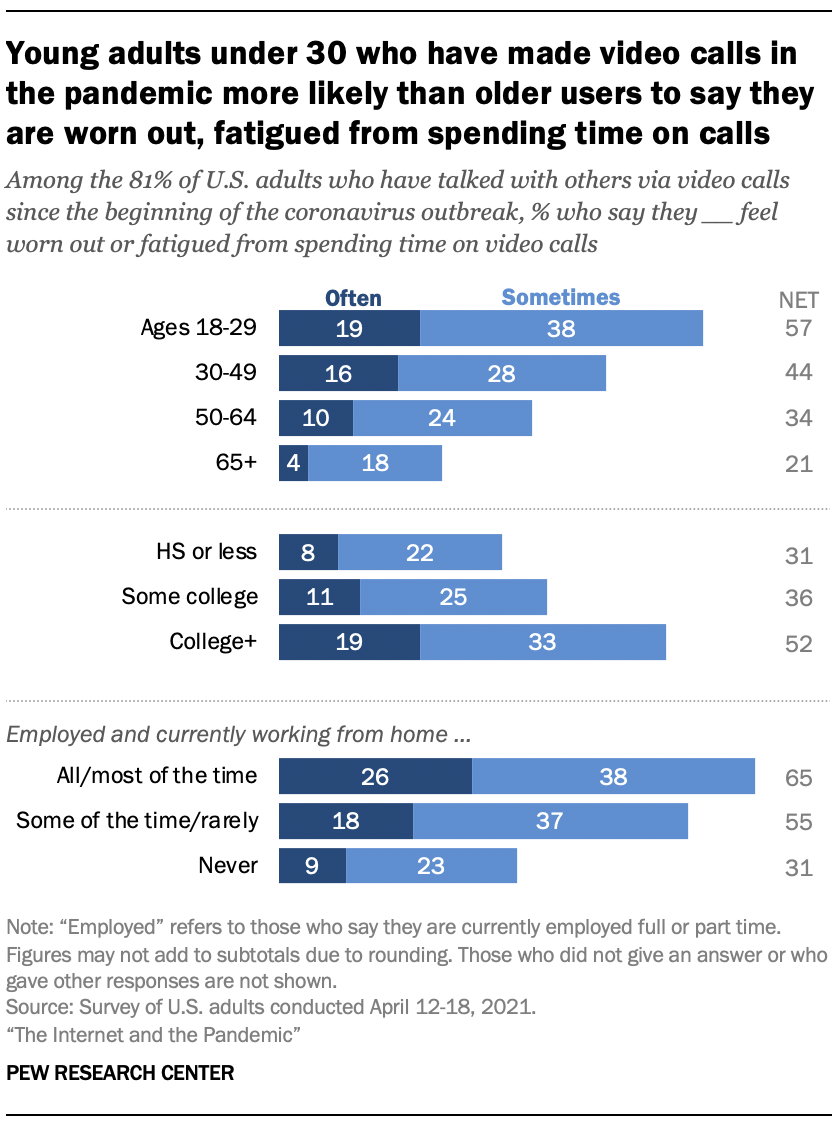

40% of those who have used video calling during the pandemic feel worn out from such calls at least sometimes

As some Americans intensified their tech use and tried new online activities, there was a possibility that some might become “worn out” by this screen time – leading to a phenomenon commonly known as “Zoom fatigue” in the context of personal and work-related video calls. Some accounts of the pandemic also raised the question of whether Americans would try to purposefully “unplug” or otherwise manage their screen time, as many children and adults alike spent more time on their devices.

Overall, among those who have used video calling during the pandemic, four-in-ten say they have often (13%) or sometimes (27%) felt worn out or fatigued from spending time on these calls. Looking at the population overall, one-third of all adults say that they feel worn out or fatigued from video calls often (11%) or sometimes (22%).

Reported fatigue increases with greater time spent on video calls. Fully 74% of those who have used video calling several times a day during the pandemic say this is the case at least sometimes, including 36% who say they feel worn out or fatigued often. About half or more of those who are on calls less often than this, but at least a few times a week, say the same.

But even a portion of those who rarely use video calling report fatigue. About a quarter of those who have talked with others via video calls only every few weeks during the pandemic say they feel worn out at least sometimes.

The new survey shows that among those who’ve made video calls in the pandemic, there are differences in reported video call fatigue by age, formal educational attainment, and work-from-home status.

Among those who have made video calls, about six-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say they feel worn out or fatigued from these calls at least sometimes. By comparison, 21% of those 65 and older say so. And about half of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree report feeling this way at least sometimes, compared with 31% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Among pandemic video call users who work from home all or most of the time, some 65% say they feel worn out or fatigued at least sometimes from the time they spend on video calls. (A separate Center study conducted in October 2020 that used a different definition of remote work and call fatigue found that about four-in-ten teleworkers who used video conferencing often were worn out by the time spent on them, compared with 63% of that group who said they were generally fine with the amount of time spent on video calls.)

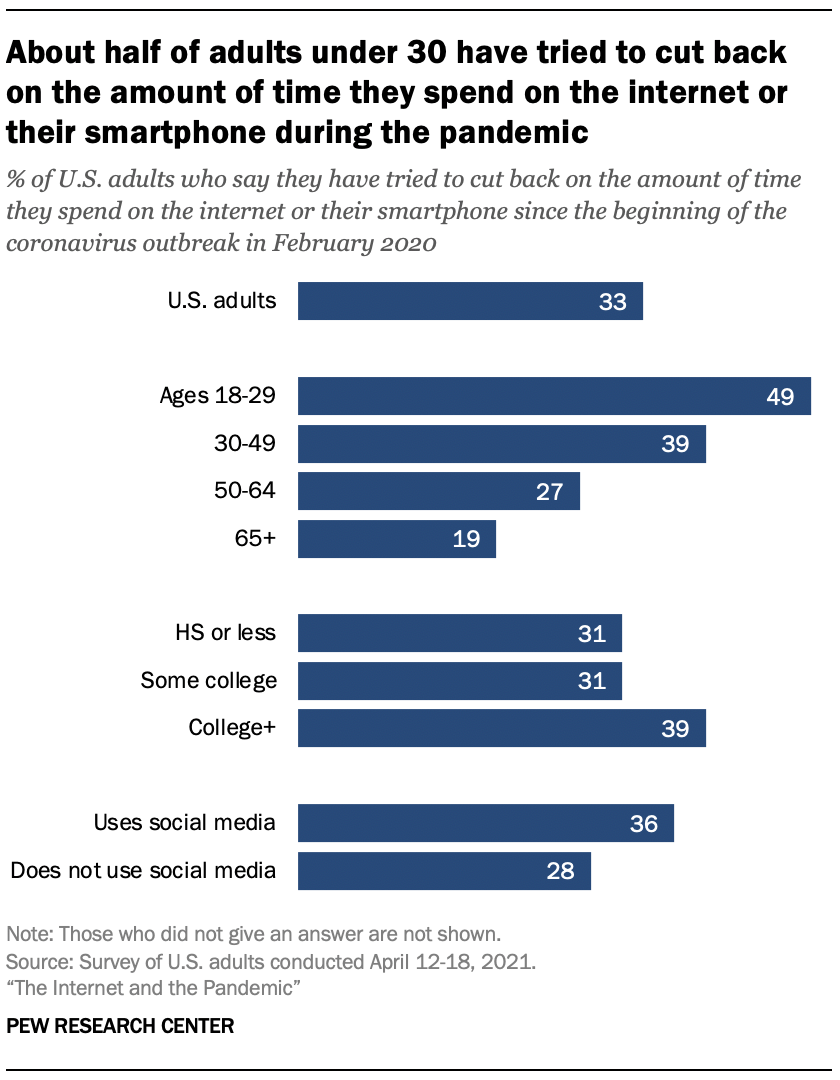

As many daily activities moved online, Americans’ reactions to increased screen time were not just limited to issues related to video calling. A third of adults also say in this survey that they have tried to cut back on the amount of time they were spending with screens – specifically on the internet or their smartphone – since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak.

Fully 49% of adults ages 18 to 29 have tried to cut back on their screen time, compared with roughly four-in-ten of those ages 30 to 49. Smaller but notable shares of those 50 to 64 (27%) and 65 and older (19%) say they’ve tried cutting down.

And Americans who use social media are more likely to say they’ve tried to cut back on screen time than those who don’t – an 8 percentage point gap.

Screen time issues also became paramount for families and children during the pandemic. The next chapter of this report discusses parents’ views on their children’s screen time, alongside other findings on the experiences of parents and children during the pandemic.

- In October 2020, a separate Center study also asked about work and video calling. The estimates in this report should not be interpreted as changing over time due to the different sets of individuals asked the question in the two surveys and because the questions in each survey had different wording. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Business & Workplace

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Technology

- Digital Divide

- Education & Learning Online

Is College Worth It?

Half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains, a majority of latinas feel pressure to support their families or to succeed at work, a look at small businesses in the u.s., majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the u.s. and working people, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 88

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Home / Essay Samples / Information Science and Technology / Internet / Internet Changed Our Lives

Internet Changed Our Lives

- Category: Information Science and Technology

- Topic: Internet

Pages: 1 (339 words)

- Downloads: -->

Enhanced Communication and Connectivity

Revolutionizing commerce and business.

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Information Technology Essays

Negative Impact of Technology Essays

Virtual Reality Essays

Artificial Intelligence Essays

Cyber Security Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->