How to Write a Dedication

#scribendiinc

And the dedication goes to…

When you have finally completed the gruelling yet wonderful process of writing a book, short story , dissertation, etc., you are then faced with the difficult decision of dedicating this source of all your hard work to someone special. Here are some helpful tips to ease your anxiety and assist you in writing a dedication page.

Picking a person

The most difficult part of writing this piece of front matter is choosing who you would like to dedicate your work to. Some writers may find it to be the most difficult part of the whole process. When choosing who to write your dedication for, think about the process you just went through and who helped you get through it. This could include a variety of people, including a parent, sibling, or other family member, a spouse or partner, a friend, a supervisor, a colleague, or even a pet. This is a very personal choice and there is no wrong decision.

Naming names

After you have decided who you will write your dedication for, you must decide how you are going to identify them. This will be based on your own personal preference and what is appropriate, according to your relationship with that person. The identification could vary from formal to informal.

On the formal end of the spectrum, your dedication could be addressed to Dr. So and So, Mr. X, or even Mother and Father. In between formal and informal, there are options like Mom, Dad, My sister, My friend, a person’s first and last name (no title), etc. On the informal side, you could use the first name or nickname of someone you know.

Reason for the dedication

The next component in writing your dedication is explaining why you chose this person. Many authors provide a reason for their dedication selections. As with the whole dedication process, this is an extremely personal and subjective decision. The dedication could simply be: "For my mom"; others may choose to explain their decision: "For my mom; without her I would not be here." You may want to write a funny anecdote about the person, an experience you shared, or even a private joke shared only by the two of you. As seen in our example dedication page, there are many types of dedications, each with it's own style. Your reason is completely dependent on your personality and your relationship with the person to whom you are dedicating your work.

Addressing the dedication

There are many ways you can address your dedication. You could write, "I dedicate this book to …", "This is dedicated to …", "To: …", "For: …", or simply just start writing your dedication without any formal address. It should be on its own page so everyone will get the hint that it is a dedication page, even if there isn't any formal address. Take into consideration the person you have chosen to dedicate your work to, your personality, and the formality of your relationship and the address will follow suit.

Alternative dedications

It has been extremely popular over the years to write a dedication page using alternative formats. Authors have used poems or funny anecdotes to express their gratitude. In the past, many dedications were often written in the style of a formal letter.

The most important things to remember when writing a dedication are to keep it simple, concise, and ensure that it truly reflects your personality and your relationship with the person the dedication is for. Remember to get your finished dedication edited by one of our book editors . You don't want to overlook calling your spouse the pettiest person in the world when you really meant the prettiest person in the world!

Image source: Mike Giles/Unsplash.com

Get Constructive Feedback to Improve Your Book

Hire a professional editor , or get a free sample.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

Examples of Dedications

Front Matter: What it is and Why it is Important

How to Write a Prologue

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

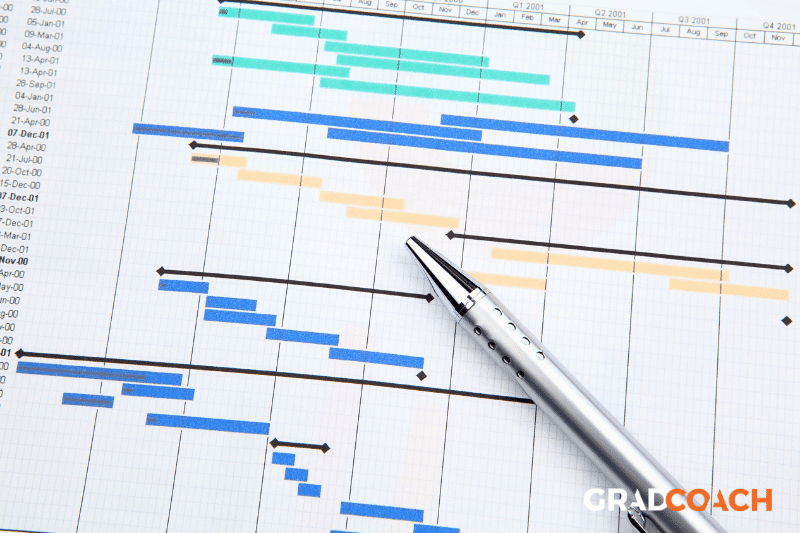

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Thank you very much, this is very insightful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 1:46 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

How to Write a Dedication for a Thesis or Dissertation?

Writing a dedication page for your thesis or dissertation is a great way to honor the people who have supported you throughout the journey of your research and writing. In this guide, we’ll show you everything you need to know about writing a dedication page for your thesis or dissertation. From formatting it to what you can include, we’ll run through all of the details to help you write your dedication page with confidence and gratitude.

What is a dedication page?

In academic writing (as well as book writing), the dedication page is where you can honor the people who have inspired or emotionally support you throughout your research and writing in a personal manner.

The dedication page is an optional section in a thesis or dissertation when it comes to academic writing.

Why should I include a dedication page in my writing?

The dedication page is not mandatory in most academic writing.

However, by paying tributes to the individuals or even the higher power who meant the most to you, you attach meaning to your work beyond the academic level.

A song is merely a song with lyrics, and that’s that. But if the same song is dedicated to someone, it will certainly entail special meanings to those who are dedicated and the dedicator (yourself). In other words, dedication serves to connect your work with the people who mean the most to you.

The same goes for your work. Do you agree?

Where does the dedication page appear in a paper?

The dedication page should appear before the main body of a thesis or dissertation. But every institution has its own requirements. You should always check the formatting guidelines provided by your school, faculty or department.

For this matter, we took a quick tour of the formatting guidelines for the top three universities in the US. And we’ve already found 3 variations.

How long is a dedication page?

A dedication page can be as short as one sentence, if not in a few short paragraphs.

Who should I include on the dedication page?

In academic writings, the dedication page is where you can show your gratitude to the individuals (and even the higher power) who have inspired you or emotionally support you on a personal level throughout your work.

They may or may not involve in your research work. You may include:

- God or the higher power

What is the formatting of a dedication page?

Always check the formatting guidelines provided by your school, faculty, or department.

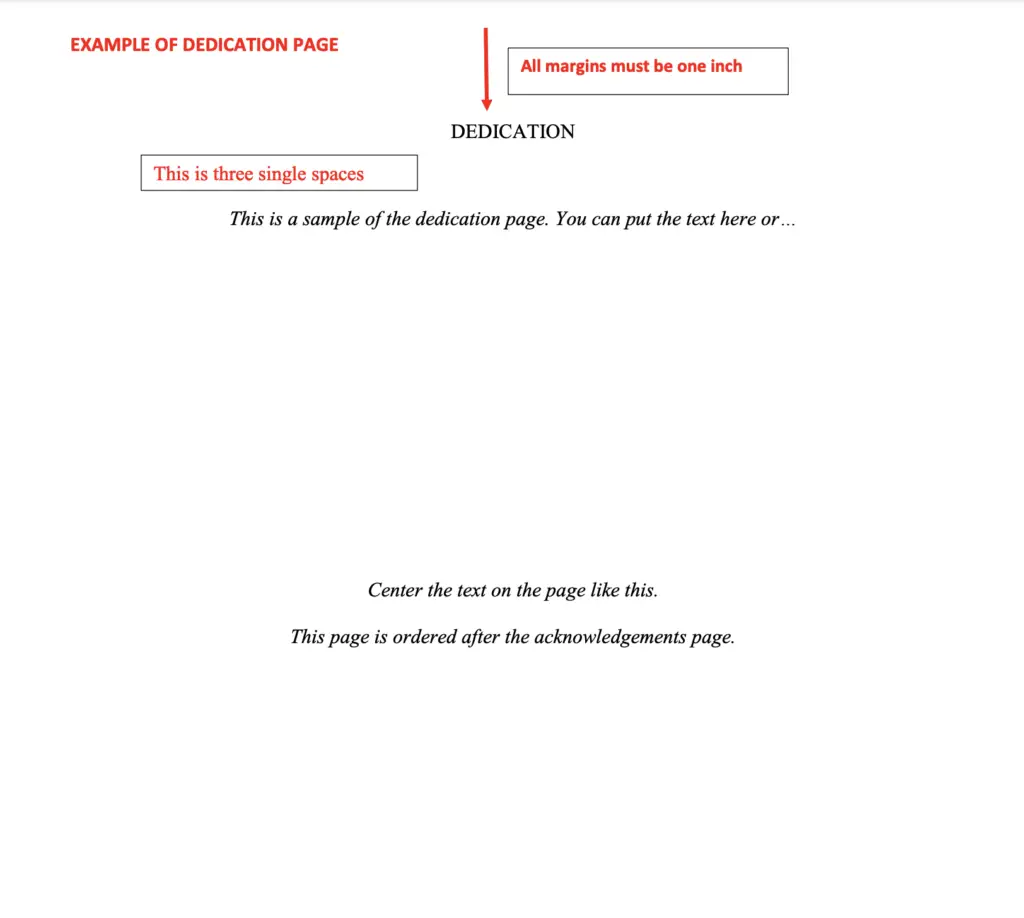

As a general rule, the title, as well as the text, should be aligned in the center of the page like this:

What is the tone and style of a dedication page?

The tone of the dedication page can be formal or informal. It can be personal, sometimes even emotional and spiritual.

Formal phases to begin a dedication:

*Work: thesis/dissertation/report/research

This [work] is dedicated to…

Example: This project is dedicated to Mr. Smith, our teacher who helped and guided us to successfully complete this work.

I dedicate this [work] to…

Example: I dedicate this thesis to my father and my mother, who with love and effort have accompanied me in this process, without hesitating at any moment of seeing my dreams come true, which are also their dreams

I am dedicating this [work] to…

Example: I am dedicating this thesis to my late grandfather who taught me all about perseverance. His memories continue to keep me going in every single day of my life

Informal phases to begin a dedication:

Example: For my Almighty God, the reason for my existence.

Example: To Bruno, who has been my support in the difficulties.

Example: To my dearest wife Jenny, to my lovely little girl Jin, to my parents, to my brothers William, John and Paul, and to all those who made this thesis possible.

The dedication page vs the acknowledgement page, what’s the difference?

While both the dedication page and acknowledgement page let you show appreciation for the help and support in your research and writing, there are some major similarities and differences between the two.

Dedication in academic writing

On a dedication page, you honor a particular group of people or an individual for inspiring or motivating you for completing the project or paper. It can be personal, emotional, or even spiritual and does not necessarily have anything to do with the academic aspects.

You dedicate your research work to the people who mean the most to you, such as the higher power, your core family members, a particular individual, friends, or someone who has a special role in your life.

Acknowledgment in academic writing

In acknowledgments, you recognize resources (e.g. grants or funding), institutions as well as individuals that are involved or have support in the course of your research and writing. These parties directly play a role in your academic career. Here, you disclose as much academic-related information as possible.

The Similarities

These sections, usually optional, should be no longer than one page.

Depending on the requirements of school or academic department, they can appear before or after the table of contents in your paper.

The Differences

The key difference between acknowledgement and dedication is that the former is more formal and the latter is more personal.

Acknowledgement usually recognizes the contributions of those who were directly involved in the research, whereas dedications are a way for the writer to pay tribute to individuals who have had a significant personal or emotional impact on their life or work.

It is common for people to dedicate their writing to God or another higher power who they believe provided them with spiritual support during the writing process.”

Here’s a brief comparison table showing the main differences between the two:

If you want to check out examples of dedication for projects, reports, theses, dissertations, and books, also read: Examples of Well-Written Dedication Section

Acknowledgement Examples for School/College Projects

Most popular Acknowledgement For School/College Projects [7 Examples] Acknowledgement for English Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Project Class 11 and 12 Acknowledgement for Project of Class 8, 9 and 10 By subjects Acknowledgement for Accounting Project [3 Examples] Acknowledgement for Business Studies Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Chemistry Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Computer Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Economics Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for English Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Geography Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for History Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Maths Project for Students [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Physics Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Social Science Project [5 Examples] Others Acknowledgement for Group Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Graduation Project [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Disaster Management Project [3 Examples] Acknowledgement for Yoga Project [3 Samples]

Other Popular Acknowledgement Examples

For work or business Acknowledgement Receipt of Payment [4 Examples] Acknowledging Receipt of Documents: A Quick Guide with Examples Acknowledgement for Presentation [9 Examples] Acknowledgement for Job Offer [3 Examples] Acknowledgement for Business Plan [4 Examples] Acknowledgement for Work Immersion [5 Examples] Acknowledgement of Receipt of Appraisal [3 Examples] Acknowledegment of Debt [5 Examples] Resignation Acknowledgement for Employers [5 Examples]

Academic Acknowledgement for Research Paper [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Internship Report [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Thesis and Dissertation [15 Examples] Acknowledgement for Portfolio [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for Case Study [4 Examples] Acknowledgement for Academic Research Paper [5 Examples] Acknowledgement for College/School Assignment [5 Examples] Acknowledgemet to God in Reports [5 Examples]

Others Acknowledgement to Funeral Attendees [5 Examples] Funeral Acknowledgement Templates (for Newspapers and Websites) Common Website Disclaimers to Protect Your Online Business Notary Acknowledgement [5 Examples]

How-to Guides on Academic Writing and Others

Most popular How to Write an Acknowledgement: The Complete Guide for Students How to Write an Acknowledgement for College Project? How to Write a Dedication Page for a Thesis or Dissertation? More on acknowledgements How to Write Acknowledgment for a Dissertation or a Thesis? Is Acknowledgement and Dedication the Same? Thesis or Dissertation How to Write a Master’s Thesis: The Ultimate Guide How to Write a Thesis Proposal? How to Write an Abstract for a Thesis? How to Write a Preface for a Thesis? Others How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper? 7 Real Research Paper Examples to Get You Started How to Write Cover Letter for an Internship Program? How to Write an Internship Acceptance Letter? How to Write a Leave Application? For Schools and the Workplace How to Write a Resignation Letter?

Introduction to Academic Writing

By O.P. Jindal Global University Duration: 16-hour Cost: FREE Gain an in-depth understanding of reading and writing as essential skills to conduct robust and critical research for your writing.

Writing in English at University

By Lund University Duration: 24-hour Cost: FREE Learn how to structure your text and arguments, quote sources, and incorporate editing and proofreading in your academic writing.

Academic English: Writing Specialization

By the University of California, Irvine Duration: 6 months Cost: Free 7-day trial, USD39 per month The skills taught in this Specialization will empower you to succeed in any college-level course or professional field. You’ll learn to conduct rigorous academic research and to express your ideas clearly in an academic format. Share your Course Certificates in your LinkedIn profile, on printed resumes, CVs, or other documents.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Thesis / dissertation formatting manual (2024).

- Filing Fees and Student Status

- Submission Process Overview

- Electronic Thesis Submission

- Paper Thesis Submission

- Formatting Overview

- Fonts/Typeface

- Pagination, Margins, Spacing

- Paper Thesis Formatting

- Preliminary Pages Overview

- Copyright Page

Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures (etc.)

- Acknowledgements

- Text and References Overview

- Figures and Illustrations

- Using Your Own Previously Published Materials

- Using Copyrighted Materials by Another Author

- Open Access and Embargoes

- Copyright and Creative Commons

- Ordering Print (Bound) Copies

- Tutorials and Assistance

- FAQ This link opens in a new window

The Dedication Page is optional. If you choose to include a Dedication Page, please ensure that:

- You are using the same font as in the rest of your manuscript.

- No images are included.

- Page number ii appears centered at the bottom of the page.

Please note that the Dedication Page is different from the Acknowledgements Page.

Dedication Page Example

Here is an example of a dedication page from the template:

- << Previous: Copyright Page

- Next: Table of Contents >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/gradmanual

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

How to write a good research proposal (in 9 steps)

A good research proposal is one of the keys to academic success. For bachelor’s and master’s students, the quality of a research proposal often determines whether the master’s program= can be completed or not. For PhD students, a research proposal is often the first step to securing a university position. This step-by-step manual guides you through the main stages of proposal writing.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

1. Find a topic for your research proposal

2. develop your research idea, 3. conduct a literature review for your research proposal, 4. define a research gap and research question, 5. establish a theoretical framework for your research proposal, 6. specify an empirical focus for your research proposal, 7. emphasise the scientific and societal relevance of your research proposal, 8. develop a methodology in your research proposal, 9. illustrate your research timeline in your research proposal.

Finding a topic for your research is a crucial first step. This decision should not be treated lightly.

Writing a master’s thesis takes a minimum of several weeks. In the case of PhD dissertations, it takes years. That is a long time! You don’t want to be stuck with a topic that you don’t care about.

How to find a research topic? Start broadly: Which courses did you enjoy? What issues discussed during seminars or lectures did you like? What inspired you during your education? And which readings did you appreciate?

Take a blank piece of paper. Write down everything that comes to your mind. It will help you to reflect on your interests.

Then, think more strategically. Maybe you have a rough idea of where you would like to work after graduation. Maybe a specific sector. Or even a particular company. If so, you could strategically alight your thesis topic with an issue that matters to your dream employer. Or even ask for a thesis internship.

Once you pinpoint your general topic of interest, you need to develop your idea.

Your idea should be simultaneously original, make a scientific contribution, prepare you for the (academic) job market, and be academically sound.

Freaking out yet?! Take a deep breath.

First, keep in mind that your idea should be very focused. Master and PhD students are often too ambitious. Your time is limited. So you need to be pragmatic. It is better to make a valuable contribution to a very specific question than to aim high and fail to meet your objectives.

Second, writing a research proposal is not a linear process. Start slowly by reading literature about your topic of interest. You have an interest. You read. You rethink your idea. You look for a theoretical framework. You go back to your idea and refine it. It is a process.

Remember that a good research proposal is not written in a day.

And third, don’t forget: a good proposal aims to establish a convincing framework that will guide your future research. Not to provide all the answers already. You need to show that you have a feasible idea.

If you are looking to elevate your writing and editing skills, I highly recommend enrolling in the course “ Good with Words: Writing and Editing Specialization “, which is a 4 course series offered by the University of Michigan. This comprehensive program is conveniently available as an online course on Coursera, allowing you to learn at your own pace. Plus, upon successful completion, you’ll have the opportunity to earn a valuable certificate to showcase your newfound expertise!

Academic publications (journal articles and books) are the foundation of any research. Thus, academic literature is a good place to start. Especially when you still feel kind of lost regarding a focused research topic.

Type keywords reflecting your interests, or your preliminary research idea, into an academic search engine. It can be your university’s library, Google Scholar , Web of Science , or Scopus . etcetera.

Look at what has been published in the last 5 years, not before. You don’t want to be outdated.

Download interesting-sounding articles and read them. Repeat but be cautious: You will never be able to read EVERYTHING. So set yourself a limit, in hours, days or number of articles (20 articles, for instance).

Now, write down your findings. What is known about your topic of interest? What do scholars focus on? Start early by writing down your findings and impressions.

Once you read academic publications on your topic of interest, ask yourself questions such as:

- Is there one specific aspect of your topic of interest that is neglected in the existing literature?

- What do scholars write about the existing gaps on the topic? What are their suggestions for future research?

- Is there anything that YOU believe warrants more attention?

- Do scholars maybe analyze a phenomenon only in a specific type of setting?

Asking yourself these questions helps you to formulate your research question. In your research question, be as specific as possible.

And keep in mind that you need to research something that already exists. You cannot research how something develops 20 years into the future.

A theoretical framework is different from a literature review. You need to establish a framework of theories as a lens to look at your research topic, and answer your research question.

A theory is a general principle to explain certain phenomena. No need to reinvent the wheel here.

It is not only accepted but often encouraged to make use of existing theories. Or maybe you can combine two different theories to establish your framework.

It also helps to go back to the literature. Which theories did the authors of your favourite publications use?

There are only very few master’s and PhD theses that are entirely theoretical. Most theses, similar to most academic journal publications, have an empirical section.

You need to think about your empirical focus. Where can you find answers to your research question in real life? This could be, for instance, an experiment, a case study, or repeated observations of certain interactions.

Maybe your empirical investigation will have geographic boundaries (like focusing on one city, or one country). Or maybe it focuses on one group of people (such as the elderly, CEOs, doctors, you name it).

It is also possible to start the whole research proposal idea with empirical observation. Maybe you’ve come across something in your environment that you would like to investigate further.

Pinpoint what fascinates you about your observation. Write down keywords reflecting your interest. And then conduct a literature review to understand how others have approached this topic academically.

Both master’s and PhD students are expected to make a scientific contribution. A concrete gap or shortcoming in the existing literature on your topic is the easiest way to justify the scientific relevance of your proposed research.

Societal relevance is increasingly important in academia, too.

Do the grandparent test: Explain what you want to do to your grandparents (or any other person for that matter). Explain why it matters. Do your grandparents understand what you say? If so, well done. If not, try again.

Always remember. There is no need for fancy jargon. The best proposals are the ones that use clear, straightforward language.

The methodology is a system of methods that you will use to implement your research. A methodology explains how you plan to answer your research question.

A methodology involves for example methods of data collection. For example, interviews and questionnaires to gather ‘raw’ data.

Methods of data analysis are used to make sense of this data. This can be done, for instance, by coding, discourse analysis, mapping or statistical analysis.

Don’t underestimate the value of a good timeline. Inevitably throughout your thesis process, you will feel lost at some point. A good timeline will bring you back on track.

Make sure to include a timeline in your research proposal. If possible, not only describe your timeline but add a visual illustration, for instance in the form of a Gantt chart.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

PhD thesis types: Monograph and collection of articles

Ten reasons not to pursue an academic career, related articles.

The 11 best AI tools for academic writing

How to harness theoretical and conceptual frameworks for groundbreaking research

Theoretical vs. conceptual frameworks: Simple definitions and an overview of key differences

A guide to industry-funded research: Types, examples & getting started

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine