- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Feature stories /

Social media & COVID-19: A global study of digital crisis interaction among Gen Z and Millennials

Who, wunderman thompson, the university of melbourne and pollfish share the outcomes of a global study investigating how gen z and millennials get information on the covid pandemic.

The full report available now

The unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how the spread of misinformation, amplified on social media and other digital platforms, is proving to be as much a threat to global public health as the virus itself. Technology advancements and social media create opportunities to keep people safe, informed and connected. However, the same tools also enable and amplify the current infodemic that continues to undermine the global response and jeopardizes measures to control the pandemic.

Although young people are less at risk of severe disease from COVID-19, they are a key group in the context of this pandemic and share in the collective responsibility to help us stop transmission. They are also the most active online, interacting with an average number of 5 digital platforms (such as, Twitter, TikTok, WeChat and Instagram) daily.

To better understand how young adults are engaging with technology during this global communication crisis, an international study was conducted, covering approximately 23,500 respondents, aged 18-40 years, in 24 countries across five continents. This project was a collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO), Wunderman Thompson, the University of Melbourne and Pollfish. With data collected from late October 2020 to early January 2021, the outcomes provide key insights on where Gen Z and Millennials seek COVID-19 information, who they trust as credible sources, their awareness and actions around false news, and what their concerns are. Some key insights uncovered include:

Science content is seen as shareworthy

When asked what COVID-19 information (if any) they would likely post on social media, 43.9% of respondents, both male and female, reported they would likely share “scientific” content on their social media. This finding appears to buck the general trend on social media where funny, entertaining and emotional content spread fastest.

Awareness of false news is high but so is apathy

More than half (59.1%) of Gen Z and Millennials surveyed are “very aware” of “fake news” surrounding COVID-19 and can often spot it. However, the challenge is in recruiting them to actively counter it, rather than letting it slide, with many (35.1%) just ignoring.

Gen Z and Millennials have multiple worries beyond getting sick

While it is often suggested that young adults are ‘too relaxed' and do not care about the crisis, this notion is not reflected in the data, with over 90% of respondents were very concerned or somewhat concerned about the risk of infection. Beyond getting sick themselves, the top concerns of respondents (55.5%) was the risk of friends and family members contracting COVID-19, closely followed by the economy crashing (53.8%).

WHO wants young people to be informed about COVID-19 information, navigate their digital world safely, and make choices to not only protect their health but also the health of their families and communities. These insights can help health organizations, governments, media, businesses, educational institutions and others sharpen their health communication strategies. Ensuring policy and recommendations are relevant to young people in a climate of misinformation, skepticism and fear.

WHO hosted a webinar on the 31st March with guests from Wunderman Thompson, University of Melbourne and Pollfish to discuss methodology, key insights and implications. To watch the video, click here .

Sarah Hess Technical Officer, Health Emergencies Programme World Health Organization [email protected]

Ellie Brocklehurst Head of Marketing & PR, APAC Wunderman Thompson [email protected]

Thomas Brauch Chief Data Officer, APAC Wunderman Thompson [email protected]

Professor Ingrid Volkmer Digital Communication and Globalization Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne [email protected]

EPI-WIN: WHO Information Network for Epidemics

Epi-win webinars, youth engagement, key insights document, watch the video recording.

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

- Get the app

- Media Choice

- Digital Equity

- Digital Literacy and Citizenship

- Tech Accountability

- Healthy Childhood

- 20 Years of Impact

London School of Economics Evaluation of Our Digital Citizenship Curriculum

AI Ratings and Reviews

- Our Current Research

- Past Research

- Archived Datasets

Getting Help Online: How Young People Find, Evaluate and Use Online Mental Health Tools and Information

Teen and Young Adult Perspectives on Generative AI: Patterns of Use, Excitements, and Concerns

- Press Releases

- Our Experts

- Our Perspectives

- Public Filings and Letters

Common Sense Media Announces Framework for First-of-Its-Kind AI Ratings System

Protecting Kids' Digital Privacy Is Now Easier Than Ever

- How We Work

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Meet Our Team

- Board of Directors

- Board of Advisors

- Our Partners

- How We Rate and Review Media

- How We Rate and Review for Learning

- Our Offices

- Join as a Parent

- Join as an Educator

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Request a Speaker

- We're Hiring

- Coping with COVID-19: How Young People Use Digital Media to Manage Their Mental Health

March 15, 2021

March 2021 marks the one-year anniversary of the start of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. After a year of lockdowns and remote schooling and the disruption of social norms, teens and young adults are reporting growing levels of depression, stress, and anxiety.

Common Sense partnered with Hopelab and the California Health Care Foundation to better understand how young people have been using social media and digital health tools to take care of their mental health during the pandemic. Our new report, Coping with COVID-19: How Young People Use Digital Media to Manage Their Mental Health (ISSN: 2767-0163), reveals that depression rates have increased significantly since 2018, especially among teens and young adults who have had coronavirus infections in their homes. Exposure to hate speech on social media also is on the rise.

The good news is that young people are proactive in supporting their own mental health. Despite the negative content they see, digital media has been a lifeline for many of them to access critical health information, stay connected to their peers, find inspiration, and receive comfort in a difficult time.

In addition to quantitative data, the report brings the experiences of young people into focus through their own words, and provides insight into how we can best support them in their mental health journeys.

This pre-pandemic snapshot of young kids' media use presents a unique opportunity to understand the impact of the pandemic when combined with future research. But the results of this report are vitally important to finding solutions that provide all children with access to media that supports learning, health, and opportunity.

Fact sheets:

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: COVID-19, depression, and social media use

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: COVID-19, depression, and social media use (en español)

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Black youth

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Hispanic/Latinx youth

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Hispanic/Latinx youth (en español)

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: LGBTQ+ youth

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Female youth

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Problematic substance use

- Coping with COVID-19 Fact Sheet: Telehealth

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2022

Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults: a meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies

- Youngrong Lee 1 ,

- Ye Jin Jeon 2 ,

- Sunghyuk Kang 2 , 3 ,

- Jae Il Shin 4 ,

- Young-Chul Jung 3 &

- Sun Jae Jung 1 , 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 995 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

29k Accesses

47 Citations

65 Altmetric

Metrics details

Public isolated due to the early quarantine regarding coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increasingly used more social media platforms. Contradictory claims regarding the effect of social media use on mental health needs to be resolved. The purpose of the study was to summarise the association between the time spent on social media platform during the COVID-19 quarantine and mental health outcomes (i.e., anxiety and depression).

Studies were screened from the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. Regarding eligibility criteria, studies conducted after the declaration of the pandemic, studies that measured mental health symptoms with validated tools, and studies that presented quantitative results were eligible. The studies after retrieval evaluated the association between time spent on social media platform and mental health outcomes (i.e. anxiety and depression). The pooled estimates of retrieved studies were summarised in odds ratios (ORs). Data analyses included a random-effect model and an assessment of inter-study heterogeneity. Quality assessment was conducted by two independent researchers using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS). This meta-analysis review was registered in PROSPERO ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ , registration No CRD42021260223, 15 June 2021).

Fourteen studies were included. The increase in the time spent using social media platforms were associated with anxiety symptoms in overall studies (pooled OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.30–1.85), and the heterogeneity between studies was mild (I 2 = 26.77%). Similarly, the increase in social media use time was also associated with depressive symptoms (pooled OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.30–1.85), and the heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I 2 = 67.16%). For sensitivity analysis, the results of analysis including only the “High quality” studies after quality assessment were similar to those of the overall study with low heterogeneity (anxiety: pooled OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.21–1.96, I 2 = 0.00%; depression: pooled OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 0.69–2.90, I 2 = 0.00%).

Conclusions

The analysis demonstrated that the excessive time spent on social media platform was associated with a greater likelihood of having symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Despite the tremendous worldwide efforts including the introduction of vaccines, developing therapeutics and social distancing, the coronavirus outbreak is not expected to dampen due to the continuous emergence of new viral strains and difficulty in effective quarantine interventions. As a result of strong quarantine measures, private meetings, gatherings, and physical contact with intimate relatives have been reduced [ 1 ]. Prolonged social distancing and loss of intimate interpersonal contact increase feelings of frustration, boredom, anxiety, and potentially depression [ 2 ].

Studies have found that young, socially active populations or workers at high risk of infection, especially college students and frontline healthcare workers, bear a disproportionate burden of mental health problems worldwide (e.g., high levels of anxiety and depression), highlighting the need for appropriate intervention in these populations [ 3 , 4 ].

Social media in digital platforms is reportedly considered as a new channel of communication that could relieve aforementioned negative aspects of isolation through helping people escape negative emotions [ 5 ], projecting their personality as they desire, and evoking the impression of gaining back some control [ 6 ]. Social media may be helpful for relieving anxiety and depression by providing information regarding the pandemic [ 7 , 8 ].

However, prolonged use of social media by the isolated could be a double-edged sword that can adversely affect mental health due to sustained exposure to excessive information and misinformation [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. While social media in digital platforms does help to promote social inclusion among adolescents and young adults, the risk associated with their excessive or problematic use cannot be overlooked [ 12 ]. Due to conflicting evidence and views regarding the effect of social media platform on the mental health, the recommendation for the use of social media in pandemic has been questioned.

Therefore, a meta-analysis was conducted to solve the contradictory effects of social media platform on anxiety and depression based on studies reporting an association between the use of social media and mental health outcomes (i.e., anxiety and depression) on the pandemic setting.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included which met the following criteria: (1) use of the English language; (2) conducted after March 11, 2020 (date the WHO declared a pandemic) and published by December 20, 2020; (3) collected data using a validated tool of mental health symptoms (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire: PHQ9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 items: GAD-7); (4) full texts available; (5) measured time spent on social media platform in either continuous or categorical variable; (5) provided their results in OR, β, and/or Pearson’s r, and (6) studies measured mental health symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

Studies with the following characteristics were excluded: (1) Studies examined traditional social media (e.g., television and radio); (2) case reports, letters, comments, and narrative reviews without quantitative results, and (3) studies using a language other than English.

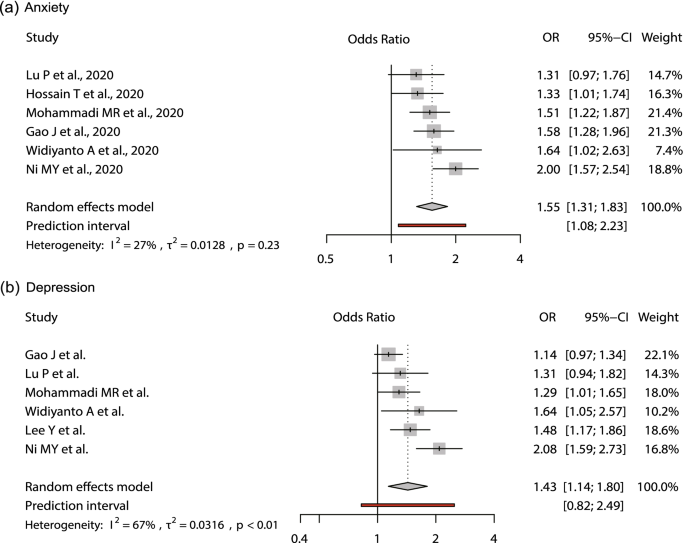

Studies investigating the association between time spent on social media and mental health outcomes (e.g., anxiety and depression) were summarised in Supplementary Material 1 . The pooled effect size of this meta-analysis was mainly presented in an odds ratio (Fig. 2 ).

Study selection

The search strategy principles were as follows: (1) “Social media” or individual names of social media in the title, keyword and abstract results; (2) Terms referring to mental health with COVID-19 specified in the title (e.g. depression, anxiety or blue).

A systematic literature search of the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases was performed to identify studies. Publication date restrictions are from March 2020 to December 20, 2020. The search terms for a systematic search were as following: (1) (“COVID-19“ OR “corona“) AND (“mental health” OR depress* OR anxiety) AND (“social media” OR “Instagram” OR “Facebook” OR “twitter”) for PubMed, (2) (“coronavirus disease 2019’/exp/mj) AND (“mental health“/exp/mj OR “depression“/exp OR “anxiety“/exp) AND (“social media”/exp./mj OR “Facebook”/exp. OR “twitter”/exp. OR “Instagram“/exp) for Embase; (3) (“COVID-19″ OR “corona”) AND (“mental health“ OR depress* OR “anxiety”) AND (“social media“ OR ‘Instagram” OR “Facebook” OR “twitter”) for Cochrane Library.

Articles were first screened by reviewing titles, followed by a full-text review. Every selection stage involved three independent researchers (two medical doctors [SJJ and YRL] and one graduate student from the Epidemiology Department [YJJ]). Every article was independently evaluated by two researchers (YJJ and YRL) in first hand, and a third researcher (SJJ) mediated the final selection in case of differences in opinion.

Data extraction

Study data were extracted by two independent researchers (YRL and YJJ). A single author first extracted the information and a second author checked for accuracy. The extracted information is as follows: country of study, participant group sampled, age group of sample, date of data collection, mental health measures, effect size information, social media use time, and whether the adjustment was made for each analysis (see Supplementary Material 1 ). Studies were subdivided into categories according to the summary estimate of effect sizes (odds ratio [OR], beta estimate from multiple linear regression [β], and correlation coefficient [Pearson’s r]).

Exposure variables

The final studies after retrieval measured the amount of time spent on social media, which was either categorical or continuous variables (see Supplementary Material 1 ). It was measured based on the response to an item in the questionnaire: “How often were you exposed to social media? [categorical]” and “How long (in hours) were you exposed to social media? [continuous].” The measurement of exposure was expressed in different wordings as follows: “Less” vs. “Frequently,” “Less” vs. “Often”, “less than 1 hour” vs. “2 hours or more,” or “less than 3 hours” vs. “3 hours or more.” To calculate the overall effect, these individually measured exposure levels were operationally redefined (e.g., “Less” and “Few” were considered the same as “less than 2 hours;” “less than 1 hour,” “Frequently,” and “Often” were treated the same as “2 hours or more” and “3 hours or more”).

Outcome variables

The outcomes of included studies were “anxiety”, and “depression”. Anxiety was ascertained by using GAD-7 (cut-off: 10+), DASS-21, and PHQ-9, while depression was measured using PHQ-9 (cut-off: 10+), WHO-5 (cut-off: 13+), and GHQ-28 (cut-off: 24+). Anxiety and depression measured by using screening tools with cut-offs presented results in odds ratios (see Supplementary Material 1 ).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and visualisations were performed with the “meta,” “metaphor,” and “dmeter” package of R version 3.6.3 ( https://cran.r-project.org/ ), using a random-effect model [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. The effect measures were odds ratio, regression coefficient, and Pearson’s r, which calculated the association between the increase in social media use time and anxiety and depressive symptoms. In each study, the association with the mental health level of the social media frequent use group (compared to the low frequency group) was calculated as the odds ratio, and the association with the increase in the mental health level per hour increase was calculated as the regression coefficient (β) and Pearson’s r. Statistics used for calculating pooled effects (e.g., odds ratio, regression coefficient, and Pearson’s r) were utilized as its adjusted value with covariates from each study, not the unadjusted crude values.

The pooled effect sizes, Cochrane’s Q, and I 2 to assess heterogeneity were calculated. The pooled effect sizes, CIs, and prediction intervals were calculated by estimating the pooled effect and CIs using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method, which is known as the one of the most conservative methods [ 16 ]. The degree of heterogeneity was categorised as low, moderate, or high with threshold values of 25, 50, and 75%, respectively [ 17 ]. Possible causes of heterogeneity among study results were explored by statistical methods such as influential analysis, the Baujat plot, leave-one-out analysis, and Graphic Display of Heterogeneity analysis [ 18 ]. In addition, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, Egger’s tests, and the trim-and-fill method [ 19 ].

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted by two independent researchers, a psychiatrist (SHK) and an epidemiologist (YRL), using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS), which can assess cross-sectional studies [ 20 ]. RoBANS has been validated with moderate reliability and good validity. RoBANS applies to cross-sectional studies and comprises six items: participant selection, confounding, exposure measurement, blinding of outcome assessments, missing outcomes, and selective reporting of outcomes. Each item is measured as having a “high risk of bias,” “low risk of bias,” or “uncertain.” For example, based on “participant selection,” each researcher marked an article as having a “high risk of bias” if, for example, the patient definitions of depression were generated by self-reported data. In cross-sectional studies, misclassification cases due to an unreliable self-contained questionnaire for categorizing depressive patients were rated as “high risk.” For the qualitative assessment, studies with two or more “high risk of bias” grades were then classified as “low quality”. The study was rated as “high quality” only if the evaluation of both raters was congruent. For sensitivity analysis, additional analysis including only “high quality” studies was conducted and it compared with the pooled estimates of overall results (see Table 1 ).

Ethical approval

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 2020 were followed for this study. No ethical approval and patient consent are required since this study data is based on published literature. This meta-analysis review was registered with PROSPERO ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ , registration No CRD42021260223, 15 June 2021).

Included and excluded studies

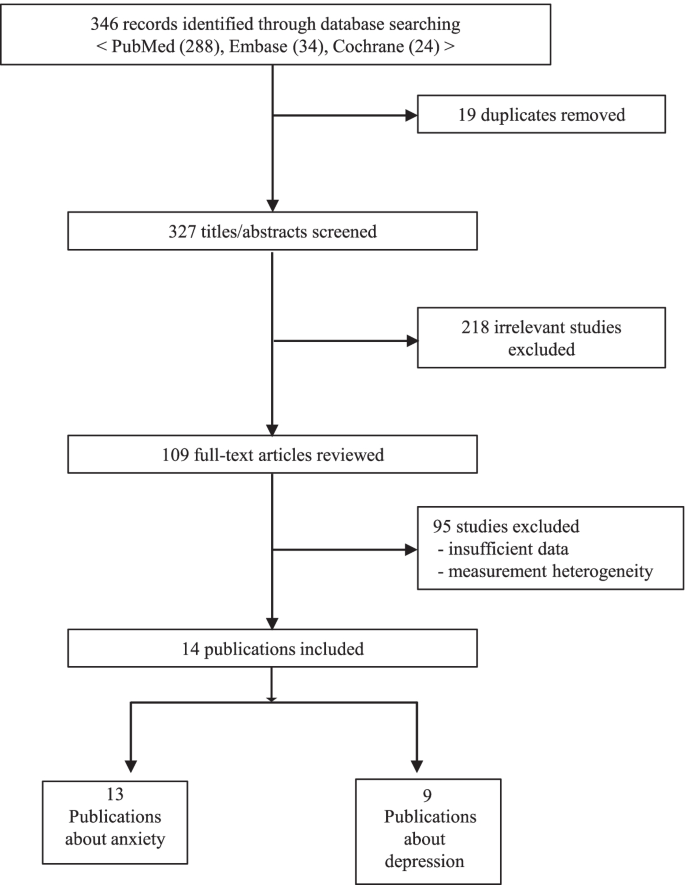

Total of 346 studies were selected from the database search (288 from PubMed, 34 from Embase, and 24 from the Cochrane Library). After removing 19 duplicate publications, 327 studies were included for the title and full-text review (see Fig. 1 ). Non-original studies and those conducted with irrelevant subjects ( n = 218) were excluded. Another 95 studies were excluded finally due to inconsistent study estimates. As summarised in Supplementary material 1 and 8 , 13 papers studied anxiety as an outcome (6 studies in odds ratio, 3 in regression coefficient, 4 in Pearson’s r), and a total of 9 papers studied depression as an outcome (6 studies in odds ratio, 3 in regression coefficient). Each of the final distinct 14 studies (after excluding duplicate studies) measured multiple mental health outcome variables (i.e., anxiety and depression), and pooled effect sizes were calculated for each outcome. Six studies that dealt with anxiety symptoms and six with depression (Supplementary Material 1 –1-1, 1–2-1) reported ORs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) ( n = 9579 and n = 13,241 for anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively). Three studies each on anxiety and depression (Supplementary Material 1 –1-2, 1–2-2) reported their findings in β ( n = 2376 and n = 2574 for anxiety and depression, respectively). All included studies were cross-sectional studies. The pooled effect size was presented in odds ratio.

Flowchart of literature search and selection of the publications

Time spent on social media and mental health outcomes

Table 1 shows the result of the meta-analysis about the relationship between time spent on social media and mental health outcomes (i.e., anxiety and depression) of the selected cross-sectional studies. The increase in the time spent using social media platforms were associated with anxiety symptoms in overall studies (pooled OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.30–1.85, prediction intervals: [1.08–2.23]), and the heterogeneity between studies was mild (I 2 = 26.77%) (see Fig. 2 ). The three cross-sectional studies (presented in β) were insignificant (β = 0.05, 95% CI: − 0.32–0.15; a unit increment of each screening tool score per hour) with relatively high inter-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 76.07%). The overall estimate of the four cross-sectional studies (Pearson’s r) was 0.18 (95% CI: 0.10–0.27) with high inter-study heterogeneity (I 2 = 73.04%). The increase in social media use time was also associated with depressive symptoms (pooled OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.30–1.85, prediction intervals: [0.82–2.49]), and the heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I 2 = 67.16%) (see Fig. 2 ).

Forest plot for social media exposure and symptoms of mental health (i.e. anxiety & depression) in cross-sectional studies. Estimates presented in odds ratios (OR)

As result of quality assessment analysis, pooled effect size of studies classified as “high quality” was presented in Table 1 . The results were similar to the overall outcome (anxiety: OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.21–1.96; depression: OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 0.69–2.90). High-quality studies had low inter-study heterogeneity (anxiety: I 2 = 0.00%; depression: I 2 = 0.00%). The kappa statistic (inter-rater agreement) was 33.3%, indicating fair agreement.

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test (Supplementary Material 4 –1). Funnel-plot analyses revealed symmetrical results (Supplementary Material 4 –2). In addition, all results of the Egger test were statistically insignificant, indicating improbable publication bias. After applying the trim-and-fill method, the funnel plot revealed no asymmetry (Supplementary Material 5 ), indicating no significant publication bias.

The study aimed to present a comprehensive direction of relevance by analysing studies investigating the association between time spent on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health symptoms (i.e., anxiety and depressive) among the public. The increase in the time spent on social media in digital platforms was associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The pooled results are in line with previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis performed before the pandemic. A systematic literature review before the COVID-19 outbreak (2019) found that the time spent by adolescents on social media was associated with depression, anxiety, and psychological distress [ 21 ]. A meta-analysis of 11 studies (2017) also reported a weak association between social media use and depressive symptoms in children [ 22 ]. A meta-analysis of 23 studies (2018) reported significant correlation between social media use and psychological distress [ 23 ]. Likewise, this study also observed a similar trend of a negative effect of social media on mental health outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the estimates of inter-study heterogeneity of these meta-analysis were relatively high (meta-analysis of 11 studies: I 2 = 92.4%; meta-analysis of 23 studies: I 2 = 62.00% for anxiety, I 2 = 80.58% for depression) compared to the analysis, which implies relatively higher homogeneity of the study population and reliable results.

Unverified information and opinions can be easily disseminated on social media platform and perceived as facts without verification. There has been a stream of news regarding the pandemic, creating a sense of urgency and anxiety. Repeated exposure to the news may affect the construct of external reality and may lead to a delusion-like experience, which has been linked to anxiety and social media overuse [ 24 , 25 ].

Additionally, discrimination and stigma related to COVID-19 on social media can make people fearful of being infected and exacerbate depression and anxiety [ 26 ]. Fear of COVID-19 may be compounded by coexisting depression and anxiety disorders [ 27 ]. Due to the high accessibility of social media platform and the ease of socialisation in a controlled setting, individuals with underlying depression may be more drawn to social media interactions rather than face-to-face ones, more so in the pandemic era [ 28 ].

Also, implementation of social distancing mandates new norms limiting physical conducts in almost all sectors of life, including educational institutes and vocational venue. Rapid transition to the new remote educational environment and telecommuting may trigger mental health issues [ 29 ].

In interpreting the findings of this study, several limitations should be considered. First, all the studies included were cross-sectional design. The possibility of a reverse causal relationship cannot be ruled out. Further studies with longitudinal data are warranted. Second, the results do not represent the general population since most of the studies recruited participants through a web-based survey, which may have had a selection bias. Lastly, some of the analysis showed a relatively high inter-study heterogeneity (range: I 2 = 0.00–80.53%). The results of the statistical approaches to identify the cause of heterogeneity (i.e. influential analysis, Baujat plot, leave-one-out analysis, and GOSH analysis) were summarised in Supplementary Material 6 and 7 .

Despite these limitations, this study exhibits a number of strengths; to the best of our knowledge, the study is the first meta-analysis to examine the relationship between use of social media and mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, to validate the results by various verification methods such as trim-and-fill methods, influential analysis, and heterogeneity analysis. In addition, sensitivity analysis was also conducted with unbiased “high quality” studies through quality assessment.

The analysis demonstrates that excessive time spent on social media platform is associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms in the pandemic. While social media may be considered as an alternative channel for people to connect with their peers in the pandemic, the findings suggest that excessive use of social media can be detrimental for mental health. Further observation studies with longitudinal design to determine the true effect of social media platform are required.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Coronavirus disease 2019

Confidence interval

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

Shortened version of PHQ

General Health Questionnaire-28

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales

World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

Shortened version of GAD

Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies

Clemens V, Deschamps P, Fegert JM, Anagnostopoulos D, Bailey S, Doyle M, et al. Potential effects of “social” distancing measures and school lockdown on child and adolescent mental health. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Batra K, Sharma M, Batra R, Singh TP, Schvaneveldt N. Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 among college students: An evidence of 15 countries. Healthcare. 2021;9(2):222.

Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, Batra R, Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9096.

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, i Spada, M. A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;83(1):262–77.

Article Google Scholar

Ryan T, Chester A, Reece J, Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(3):133–48.

Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang Y, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e17–8.

Liu BF, Kim S. How organizations framed the 2009 H1N1 pandemic via social and traditional media: implications for US health communicators. Public Relat Rev. 2011;37(3):233–44.

Fung IC-H, Tse ZTH, Cheung C-N, Miu AS, Fu K-W. Ebola and the social media; 2014.

Book Google Scholar

Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder-Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa031.

Kramer AD, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(24):8788–90.

Daniels M, Sharma M, Batra K. Social media, stress and sleep deprivation: a triple “S” among adolescents. J Health Soc Sci. 2021;6(2):159-66.

Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Ebert DD. Doing meta-analysis with R: a hands-on guide. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2021.

Schwarzer G. meta: an R package for meta-analysis. R news. 2007;7(3):40–5.

Google Scholar

Viechtbauer W, Viechtbauer MW. Package ‘metafor’. The Comprehensive R Archive Network Package ‘metafor’. 2015. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metafor/metafor.pdf .

IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):1–12.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Olkin I, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA. GOSH–a graphical display of study heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(3):214–23.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63.

Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo H-J, Sheen S-S, Hahn S, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–14.

Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020;25(1):79–93.

McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Adolescent Res Rev. 2017;2(4):315–30.

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274–81.

Saha S, Scott J, Varghese D, McGrath J. Anxiety and depressive disorders are associated with delusional-like experiences: a replication study based on a National Survey of mental health and wellbeing. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):e001001.

Faden J, Levin J, Mistry R, Wang J. Delusional disorder, erotomanic type, exacerbated by social media use. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2017;2017:8652524.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Person B, Sy F, Holton K, Govert B, Liang A. Fear and stigma: the epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):358.

Soraci P, Ferrari A, Abbiati FA, Del Fante E, De Pace R, Urso A, et al. Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Italian Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020.

Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Loneliness and social uses of the internet. Comput Hum Behav. 2003;19(6):659–71.

Kaurani P, Batra K, Hooja HR, Banerjee R, Jayasinghe RM, Bandara DL, et al. Perceptions of dental undergraduates towards online education during COVID-19: assessment from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Advanc Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:1199.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Editage ( www.editage.co.kr ) for English language editing.

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2020R1C1C1003502), awarded to SJJ.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 50-1 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, 03722, South Korea

Youngrong Lee & Sun Jae Jung

Department of Public Health, Yonsei University Graduate School, Seoul, South Korea

Ye Jin Jeon, Sunghyuk Kang & Sun Jae Jung

Department of Psychiatry, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea

Sunghyuk Kang & Young-Chul Jung

Department of Paediatrics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea

Jae Il Shin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: YRL, SJJ. Data curation: SJJ, JIS, YCJ, YRL. Formal analysis: YRL, SJJ. Funding acquisition: SJJ. Methodology: JIS, YCJ, YRL, SJJ. Project administration: SJJ. Visualization: YRL. Writing – original draft: YRL, YJJ, SHK, SJJ. Writing – review & editing: YRL, YJJ, SHK, JIS, YCJ, SJJ. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sun Jae Jung .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

No ethical approval and patient consent are required since this study data is based on published literature. This meta-analysis review was registered with PROSPERO ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ , registration No CRD42021260223, 15 June 2021).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, Y., Jeon, Y.J., Kang, S. et al. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults: a meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health 22 , 995 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13409-0

Download citation

Received : 18 January 2022

Accepted : 05 May 2022

Published : 17 May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13409-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social distance

- Mental health

- Systemic reviews

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

12th August 2024: digital purchasing is currently unavailable on Cambridge Core. We apologise for the inconvenience.

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness

- > Volume 15 Issue 4

- > The Important Role of Social Media During the COVID-19...

Article contents

Promote reliable information and combat misinformation, promote the healthy development of social media, conflict of interest statement, the important role of social media during the covid-19 epidemic.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 September 2020

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic has received close attention from governments, researchers, and the public in various countries. 1 , Reference Han, Wang, Zhang and Tang 2 In this case, billions of people are eager to get information about COVID-19 through social media. The rapid dissemination of topics and information related to COVID-19 has affected the behavior of the public during the epidemic. Today, more than 2.9 billion people use social media regularly. Reference Merchant and Lurie 3 These social media have an amazing spread speed, coverage, and penetration rate. During the COVID-19 epidemic, the social media platforms play an important role in dissemination information. Reference Merchant and Lurie 3

The World Health Organization (WHO) has found that the outbreak of COVID-19 and the response measures are accompanied by abundant information, and it is difficult to find reliable sources and reliable guidance. For rumors and false information spread on social media, it is necessary to coordinate the search for sources, identify, and reduce their spread. Reference Merchant 4 A study evaluating the number of times people watch COVID-19 medical videos on YouTube found that independent users were more likely to post misleading videos than useful ones (60.0% vs 21.5%, P = 0.009). Reference D’Souza, D’Souza and Strand 5 The actions of government agencies and social media giants have shown that public-private cooperation to identify, fact-check, and even delete false or outdated information may be an effective way to prevent these online information from hindering or even worsening public health efforts. Reference Limaye, Sauer and Ali 6 Social media operators can monitor high-traffic information and combine artificial intelligence to remove misleading information in a timely manner.

As clinicians in China, we often hear patients say that they have wanted to see a doctor for a long time. When they saw some reports in the media, they did not dare to go out or even come to the hospital. Some patients have said: “COVID-19 is a terrible infectious disease, most patients will die after infection,” or “the virus is still in the air, I dare not open the window.” Although the Health Committee of the People’s Republic of China recommends that people do not need to wear masks when there is no crowd outdoors, 7 some people are afraid to take off the masks because they are worried about being infected with airborne viruses. In fact, social media play a vital role in the dissemination of public health knowledge. However, during the epidemic, it is sometimes abused to spread unrealistic news, which may cause mental health problems. Reference Depoux, Martin and Karafillakis 8 Therefore, social media need to publish and update information about the epidemic in a timely manner, and popularize knowledge through the government and medical professionals to help guide the public correctly and stabilize public sentiment.

The WHO, academic institutions, and other official health institutions should consider using influential social media to disseminate accurate medical information to the general public. The information quality of social media should also be monitored. Ideally, established health care experts should ensure that potential misinformation is not disseminated. For global institutions, such as the WHO, the dissemination of correct information in different languages could be considered, especially in developing countries.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 15, Issue 4

- Qilin Tang (a1) , Kai Zhang (a2) and Yan Li (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.330

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.8(12); 2022 Dec

The impact of media on children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review ☆

a Sapienza, University of Rome, Department of Dynamic Clinical and Health Psychology, Via degli Apuli, 1, 00186, Rome, Italy

L. Cerniglia

b International Telematic University Uninettuno, Faculty of Psychology, Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 39, 00186, Rome, Italy

Associated Data

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Although mobile technologies are a fundamental part of daily life, several studies have shown increased use of electronic devices, TV, and gaming during childhood in conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus affected almost every country, causing uncertainty about the future, social isolation, and distress. This narrative review has searched the scientific literature in the field focusing on children. A non-systematic literature review was conducted in May 2022. Various databases were employed to conduct the document research for this paper, such as “Google Scholar”, “PubMed”, “Web of Science”. Keywords for the search included “screen time”, “media”, “digital use”, “social media”, “COVID-19”, “pandemic”, “lockdown”, “children”, “effect of media on children during COVID”. It was found that both children and adolescents seem to have used technologies to confront struggles provoked by COVID-19, such as the onset or exacerbation of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, moreover, other studies have suggested that increased media use can have positive effects on children depending on usage and monitoring by the parents.

Media; Children; COVID-19; Narrative review.

1. Introduction

1.1. background: children and media.

Earlier literature has pointed out that media, particularly the Internet, affect individuals' health, interpersonal relationships, concerns and opinions, and sleep ( Do et al., 2020 ; Tran et al., 2017 , 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ). Particularly for children, media contribute to daily life throughout development ( Calvert and Valkenburg, 2013 ): today's children are born and grow involved in media, as brilliantly described by the expression "digital natives" ( Prensky, 2001 ). Mobile technologies are a gateway to a wide range of information: their continued modernization, such as electronic tablets and smartphones, allows children and adolescents to be connected to media and move between them 24/7: youths can use their mobile phones to text or call one another, watch online television programs or movies, play online games, or use mobile apps ( Calvert, 2015 ).

Digital progress has supplied more innovative educational opportunities and easier access to information and communication ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ). Therefore, the digital age has fundamentally changed the lives of children, affecting their learning, social relationships, play, and overall development. At the same time, there are concerns about the possible harm caused by the excessive use of digital technology ( Huber et al., 2018 ; Przybylski et al., 2020 ) that could even result in a full-blown Internet addiction ( Mak et al., 2014 ).

There is significant literature highlighting the various problems that may result from excessive exposure to digital media, and the concerns are specific to each age group, from infants to adolescents ( Chonchaiya et al., 2011 ; Heffler et al., 2020 ; Srisinghasongkram et al., 2021 ).

Previous studies suggest that children's cognitive, behavioral, and emotional development might be impaired by exposure to digital media early in life, as it narrows their interests and limits areas of exploration and learning. This makes it difficult for kids to involve themselves in non-electronic tasks, decreases play time with other children, and thus impairs the development of imaginative skills, creativity, and social skills. Digital media also impairs children's maturation of language, attention, reading, and reasoning ( Chonchaiya et al., 2011 ; Heffler et al., 2020 ), the latter of which is also hindered by the many behavioral problems that can develop, like hyperactivity and inattention, aggression and conduct problems ( Srisinghasongkram et al., 2021 ). All of this has a huge negative effect and involves several areas of the individual: cognitive (intellectual) disorders, lack of attention, poor school performance, impulsivity, and poorer logical reasoning ( Srisinghasongkram et al., 2021 ).

A recent publication ( Stiglic and Viner, 2019 ) showed moderately convincing support for a correlation betwixt display time and depressive symptomatology and weak evidence for an association betwixt screen time and behavior problems, anxiety, hyperactivity, inattention, decreased self-esteem, and decreased psychosocial well-being in young children.

Another serious consequence is cyberbullying: children may be bullied and exposed to traumatic and pornographic/sexually explicit images. All of these may develop further adverse psychological implications ( American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016 ).

1.2. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

At the end of 2019, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in China; it is a severe infectious disease with high contagiousness and rapid transmission rate, affecting the entire world population and causing various inconveniences in daily life ( Phelan et al., 2020 ). Several studies have shown that the policy of social isolation to control the circulation of COVID-19 did carry a complex influence on psychological well-being ( Chen et al., 2020 ; Duan et al., 2020 ; Lee et al., 2021 ; Xie et al., 2020 ).

COVID-19 took place when digitization was now global, in a society where anyone can be connected in any part of the globe ( Serra et al., 2021 ). Millions of children have been adversely affected by it: due to school closures, many youths have been forced to continue their education online and rely on digital media to stay connected with their peers ( Gupta and Jawanda, 2020 ). Consequently, social network use has increased: children spent more time with smartphones, tablets, and computers (e.g., Chen et al., 2021 ; Dong et al., 2020 ; Eales et al., 2021 ; Kamaşak et al., 2022 ; Serra et al., 2021 ; Susilowati et al., 2021 ; Teng et al., 2021 ).

Internet and social media provided kids and teenagers to remain connected with peers and relatives but also an avenue to confront unavailability of human interactions during COVID-19 and thus adverse emotions ( Cauberghe et al., 2021 ; Götz et al., 2020 ; Marciano et al., 2021 ). In compliance with these studies, the Compensatory Internet Use Theory ( Kardefelt-Winther, 2014 ) argues that adverse life events and stressors can provide motivation for anyone to turn to the Internet to mitigate adverse feelings related to these factors.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to consider that during the pandemic internet access was justified by online classes and peer communication, causing possible misuse ( Li et al., 2021a ) .

Because chronic stress during the pandemic can result in adverse emotional disorders, such as depression and anxiety (e.g., Pfefferbaum and North, 2020 ; Qiu et al., 2020 ), it has been observed that during the COVID-19 emergency, some people relied on dangerous coping strategies, such as using smartphones more frequently to consult the Internet and social media in order to alleviate pandemic-related anxiety and follow the news ( Király et al., 2020 ).

Indeed, using the Internet as entertainment can be a regular way for infants to discharge emotions and stress and cope with reality ( Kwon, 2011 ); however, excessive media use can lead users, especially children, to be less interested in real life and focus only on what is happening on the Internet ( King and Delfabbro, 2014 ). The World Health Organization (WHO) indicates a limit of 1 h of display time for 5-year-olds as a guideline ( WHO, 2019 ). Nevertheless, parents experienced many pressures related to screens and technologies since before the onset of the pandemic ( Radesky et al., 2016 ). Considering COVID-19, the inability of the majority of families to comply with the instructions on screens has been recognized.

During the pandemic, the news trended mostly negatively ( Ogbodo et al., 2020 ; Robertson et al., 2021 ; Priest, Sehgal, & Cook, 2020). Exposure to this kind of news, such as increased infections and deaths or the resulting economic crisis, causes stress and anxiety, and even panic attacks, especially among susceptible groups ( Scheufele, 1999 ). In fact, cross-cultural research centered on the moment of isolation found almost 50 percent of the world's infants were frightened by reports of COVID-19 ( Götz et al., 2020 ). Since pandemic-related news on social media channels was frequently misinformative, getting exposed to this could have adverse emotional implications ( Gabarron et al., 2021 ).

In addition, children can be exposed to inappropriate content and cyberbullying: according to a study conducted by Hunduja and Patchin (2020), even in the pre-COVID-19 period, the Internet was seen to expose children to increased cyberbullying, which can result in low self-esteem and even suicide attempts.

Indeed, the increase in media use is one of the most insidious threats of our time, as it has lowered the age of Internet use and awareness, consequently increasing the related risks and dangers. Therefore, the pandemic fueling this condition has left its mark on further development ( Kamaşak et al., 2021 ).

Earlier literature has focused mainly on adulthood (e.g., Wang et al., 2021a ; Wang et al., 2021b ) or adolescents ( Ren et al., 2021 ), paying less attention to the impact that media has on children, particularly during COVID-19. Therefore, this paper is designed to recapitulate the impact of media on infancy during COVID-19 and its implication on welfare.

The methodological approach of the present paper consists of a narrative review ( Green et al., 2006 ; Pan, 2008 ) and it is a type of interpretive-qualitative publication that does not answer a specific question but aims to discuss the state of the literature on a given issue and increase the scientific community's debate on it ( Grant and Booth, 2009 ).

A non-systematic literature review was conducted in May 2022. Since this was a narrative review, we did not use a risk of bias instrument, as some authors believe that this type of review may or may not include a quality assessment ( Grant & Booth, 2009 ; Pautasso, 2013 ).

Various databases were consulted in the search for papers, such as “Google Scholar”, “PubMed”, “Web of Science”. Keywords for the search included “screen time”, “media”, “digital use”, “social media”, “COVID-19”, “pandemic”, “lockdown”, “children”, “effect of media on children during COVID”. These keywords were combined with Boolean operators to restrict the results. The studies were filtered by two of the authors (A.R. and M.M.) and the relevant ones were included in this review, while the unrelevant ones were excluded, as shown in Figure 1 . Consequent information is summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1

Search strategy.

| Database | Keywords | Population |

|---|---|---|

| | Screen time, media, digital use, social media, COVID-19, pandemic, lockdown, children, child, effect of media on children during COVID. | Children between 2-13 years |

As for the eligibility criteria, we considered the age group 2–13 years, and papers that did not treat the main theme of the age group were discarded. Only studies published between 2020 and 2022 were considered. Since limiting the inclusion of studies by the language of publication is a widespread practice in reviews ( Stern and Kleijnen, 2020 ), we chose to follow this line: articles published not in English were not considered in the present paper. Also, some thesis dissertations (n = 2) were included. We examined each publication's title and abstract using our focus as a guide.

This manuscript aimed to summarize the evidence on the influence of media on children during COVID-19 and its impact on well-being. Table 2 provides a brief description of the selected studies.

Table 2

List of selected publications: Author/Year; Title; Main Issues and Measures.

| Author/Year | Title | Highlighted issues | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal association between smartphone ownership and depression among schoolchildren under COVID-19 pandemic | Smartphone, COVID-19, Depression, Schoolchildren, Screen time | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A; ). | |

| Camerini, A. L., Albanese, E., Marciano, L., & Corona Immunitas Research Group. (2022) | The impact of screen time and green time on mental health in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic | Screen time, green time, mental health, child, COVID-19 | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Corona Immunitas Ticino (CIT; ). |

| . | Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during the COVID-19 school hiatus. | COVID-19; problematic gaming; problematic social media use; problematic smartphone use; psychological distress; school hiatus | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF9; ); Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS; Ibidem); Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS; Ibidem); Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; ). |

| The Relationship Between Children's Problematic Internet-related Behaviors and Psychological Distress During the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study | addictive behaviors, COVID-19, Internet, pandemic, psychological distress, social media, video games | Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; ); Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS; ); Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS9-SF; Ibidem). | |

| Children's Digital Play during the COVID-19 Pandemic: insights from the Play Observatory | Digital Play, COVID-19, Childhood, Digital Media | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study for both parents and children. | |

| Children's screen and problematic media use in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic | Screen media use; problematic media use, COVID-19, children | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; adapted versions of the Common Sense Census (CSC; ); Measure of Problematic Media Use - Short Form ( ). | |

| The Association of Maternal Emotional Status With Child Over-Use of Electronic Devices During the COVID-19 Pandemic | COVID-19 pandemic, maternal depression, maternal anxiety, child electronic devices over-use, media, family environment | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS; ); Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS; ); Family Environment Scale (FES-CV; ). | |

| Screen time use and Children's Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic | Parent stress, parenting styles, screen time, behavioral outcomes, education, COVID-19 | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; ); Parent Stress Index -Fourth Edition Short Form (PSI-4; ); Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; ). | |

| Kamaleddine, A. N., Antar, H. A., Abou Ali, B. T., Hammoudi, S. F., Lee, J., Lee, T., ... & Salameh, P. (2022) | Effect of Screen Time on Physical and Mental Health and Eating Habits During COVID-19 Lockdown in Lebanon | COVID-19; Screen time; Eating; Sleep; Depression. | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Children Sleep Habit Questionnaire-Abbreviated (CSHQ-A; ); Preschool Feelings Checklist (PFC; ). |

| Parental Mental Health and Children's Behaviors and Media Usage during COVID-19-Related School Closures | COVID-19; School Closure; Parental Mental Health, Children's Behaviors; Media Usage | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ; ); Behavior Problem Index (BPI; ); Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; ). | |

| Digital technology use during the covid-19 pandemic and its relations to sleep quality and life satisfaction in children and parents | digital technology, life satisfaction, lockdown, sleep quality | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study. | |

| Li, X., Vanderloo, L. M., Keown-Stoneman, C. D., Cost, K. T., Charach, A., Maguire, J. L., ... & Birken, C. S. (2021b) | Screen Use and Mental Health Symptoms in Canadian Children and Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic | specific forms of screen use, depression, anxiety, conduct problems, irritability, hyperactivity, and inattention in children and youth during COVID-19. | Multiple ad hoc questionnaires were developed for the present study. |

| Psychological and Emotional Effects of Digital Technology on Children in COVID-19 Pandemic | digital technology; brain condition; neuropsychological effects; COVID-19 | ||

| Exploring the Influences of Prolonged Screen Time on the Behavior of Children aging 3–6 years During COVID-19 Crisis | Prolonged screen time; Pandemic; COVID-19; Child's behavior; Digital device | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; ); Socioeconomic Status Questionnaire (SES). | |

| Sciberras, E., Patel, P., Stokes, M. A., Coghill, D., Middeldorp, C. M., Bellgrove, M. A., ... & West | Physical Health, Media Use, and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents With ADHD During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia | ADHD, COVID-19, psychological well-being | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS; ); An adapted version of the COVID-19 Pandemic Adjustment Survey (CPAS; ). |

| Smartphone use and addiction during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: cohort study on 184 Italian children and adolescents | Smartphone, Addiction, COVID-19, School-age children | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; Italian Smartphone Addiction Scale Short Version (SAS-SV; ). | |

| Shuai, L., He, S., Zheng, H., Wang, Z., Qiu, M., Xia, W., ... & Zhang, J. (2021). | Influences of digital media use on children and adolescents with ADHD during COVID-19 pandemic | ADHD, COVID-19, Digital media, Mental health | Self-rating Questionnaire for Problematic Mobile Phone Use (SQPMPU; ); Internet Addiction Test (IAT; ). Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale (SNAP; ); Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF; ); Adolescent Self-rating Life Events Checklist (ASLEC; ); the Chinese version of the Family Environment Scale (FES-CV; ); Students learning motivation scale (SLMS; ); Depression self-rating scale for children (DSRSC; ); Screening child anxiety-related emotional disorders (SCARED; ); the study also designed the Home Quarantine Investigation of the Pandemic (HQIP). |

| Werling, A. M., Walitza, S., Grünblatt, E., & Drechsler, R. (2021a) | Media use before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown according to parents in a clinically referred sample in child and adolescent psychiatry: Results of an online survey in Switzerland | Screen media use, problematic use of the internet, COVID-19 pandemic, Lockdown, Child and adolescent psychiatry | An ad hoc questionnaire was developed for the present study; PUI-Screening Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (PUI-SQ; ). |

Several papers selected in this review proved that the pandemic influenced children's habits toward electronic media, such as gaming and time spent on social media or smartphones ( Adachi et al., 2022 ; Camerini & Albanese, 2021; Chen et al., 2021 ; Chen et al., 2022 ; Hmidan, 2022 ; Kim et al., 2021 ; Marfua, 2021 ; Sciberras et al., 2022 ; Serra et al., 2021 ; Werling et al., 2021a , Werling et al., 2021b ).

It is possible to summarize the various contributions in this article by following a few main themes: the psychological and physical outcomes of using and owning technological gadgets during COVID-19 ( Adachi et al., 2022 ; Camerini et al., 2022 ; Chen et al., 2021 ; Chen et al., 2022 ; Cowan et al., 2021 ; Guo et al., 2021 ; Hmidan, 2022 ; Limone and Toto, 2021 ; Werling et al., 2021a ; Serra et al., 2021 ); behavioral problems related to overuse of media during COVID-19 ( Li et al., 2021b ; Marfua, 2021 ); the relationship between eating and sleeping disorders and the use of media during the pandemic ( Kamaleddine et al., 2022 ; Kim et al., 2022 ; Kotrla Topić et al., 2021 ); the effect of media in groups of clinical and ADHD children ( Sciberras et al., 2022 ; Shuai et al., 2021 ).

First, several focused on the outcomes of media on psychological and physical well-being, showing that some aversive outcomes due to the use of smartphones were noticed significantly more often in the study population during COVID-19, compared to the pre-pandemic time. In particular, the study by Serra et al. (2021) revealed a considerable risk of smartphone addiction in the pandemic (31.5 % before vs during the emergency 46.7% were outlined and 27.2% were high risk). Moreover, a study ( Adachi et al., 2022 ) instead focused on smartphone ownership and revealed a dissimilar result on depressive symptoms depending on whether children owned a smartphone or not: those who owned a cell phone had significantly higher and lower rates at the cutoff than expected. Consistent with these results on the effects of media overuse in children during COVID-19, the work of Chen et al. (2021) showed that IGDS, BSMAS, SABAS, depression, anxiety, and stress scores were positively and significantly related. In this study, mediation analyses indicated that social media and smartphone activities were mediators in the association between depression, anxiety, and stress, and increased playtime during school hiatus. In a longitudinal study ( Chen et al., 2022 ) repeated-measures analyses of variance noted a significant difference in mean psychological distress, problematic smartphone use, and problematic gaming. Moreover, other researchers not only gave attention to the emotional state of children but also of mothers, showing that maternal anxiety/depression was related to an overuse of handheld Internet devices, especially smartphones, among infants and children ( Guo et al., 2021 ).

In line with these results, very interesting is Hmidan's (2022) study that explored and demonstrated a significant association between screen time and internalizing behaviors: time spent on the screen was a positive predictor of internalizing behaviors (p < .05). In contrast, no association was noted between screen time and externalizing behaviors.

In the second place, on behavioral problems, two studies ( Li et al., 2021b ; Marfua, 2021 ) found a worsening in children's conduct during COVID-19 concerning media usage. The study by Li and colleagues (2021) showed that in younger children, higher time spent using TV or digital media was associated with higher levels of behavior problems and hyperactivity/disattention ( Li et al., 2021b ). In the same paper ( Li et al., 2021b ), was found that in older children (M = 11.3 +/- 3.3 years) more time spent using digital media or watching TV was connected with higher levels of depression, irritability, inattention, and hyperactivity; more time spent in online learning was linked with higher levels of depression and anxiety; higher levels of video-chatting time were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms ( Li et al., 2021b ). Marfua (2021) noted that 55% of mothers reported a change in their children's behavior because of the long time spent on screens during the spread of COVID-19: children shower overactivity, attention problems, reduced interest in learning, showed aggressive attitude, were unable to control emotion and began to hide information (ibidem). In addition, a significant correlation was also found: the prosocial behavior of children decreases in relation to higher screen time (ibidem). The correlation between conduct, hyperactivity, peer relationship, and screen time was non-statistically significant.

Other studies have given importance to the adverse effects of screen time on physical health during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as eating habits, physical activities, and sleep. In particular, some studies focused on unhealthy eating habits. One study ( Kamaleddine et al., 2022 ) conducted a logistic regression analysis using food consumption while using media devices as a dependent variable. The significant independent variables that predicted children's habit of eating foods while using electronic devices were total time spent on screen ≥2 h, time spent on smartphone screen ≥2 h, sleep problems, the ownership of technological device, and not eating unhealthy foods (ibidem). Another study (Kim et al., 2022) that seems to confirm this result states that during the closure of school children gained weight, have done less sport, and have suffered increased exposure to screens. This study also observed that children's sleep problems were associated with time spent on tablets and smartphones, but not their frequency. In line with these results the study of Camerini et al. (2022) emphasized a reduction in the time that children have spent outdoors (green time) and an increase in media time with an overall reduction in children's health.

The work of Kotrla Topić et al. (2021) concerns sleep. In this study, sleep quality was investigated independently for three age groups of children (attending kindergarten, lower, or upper elementary school grades); in all three age groups, parents reported that their children had a good or very good sleep quality. The findings showed a significant negative association between sleep quality and age (partial r = -0.213, p < 0.001). For children, partial correlations were calculated between parents' ratings of sleep quality and digital technology usage, and the effect of age was controlled for. Researchers found a significant negative correlation between sleep quality and smartphone use in leisure time, implying that those who most frequently used smartphones for leisure time had poorer sleep quality.

An interesting study by Werling et al. (2021a) focused on a clinically referred sample and conducted a repeated-measures analysis of gaming time, finding that the primary outcome of gaming over time and the game interaction divided by gender were significant. A pairwise comparison showed that after the lockdown, female patients reported a play time similar to the pre-pandemic, but this did not occur in male patients. Planned contrasts disclosed significant differences in time spent on social media from T1 to T2 and T1 to T3. The pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between time spent on social media from T1 to T3 in girls but not in boys. According to the results of this study, during the lockdown, the negative effects of using devices on family quality of life have intensified. In the last two weeks, these negative outcomes seem to have returned to normal levels for most parents. Taken together, however, according to parents' perceptions, the lockdown appears to have had very little effect on problem behaviors and specific risks related to the media usage. Parents were requested to indicate if the intensity of the main psychopathological problem had varied since January 2020 and during the lockdown. Most replied that there had been no significant change, meanwhile an increase in problems was referred by an average percentage of parents (37.7%) and a worsening by 21.2%. Statistical comparison between groups concerning estimated screen time in patients with worsened, unaltered, and improved symptoms during the lockdown found noticeable and significant effects. In children between 10 and 13 years with worsening symptomatology, the total time expended on media was significantly higher compared to other groups with no change or improvement in symptoms of the psychopathological disorder. It was also explored if overall time spent on media was correlated with the number of psychopathological disorders reported by parents, the frequency of online school during the lockdown and the frequency of allowed activities outside the home during the lockdown. Neither of these factors had a significant effect on the total time dedicated to media.

Finally, two studies have considered children with ADHD. In the first one ( Sciberras et al., 2022 ), children's stress about COVID-19 was significantly associated with a higher use of social media; the hypothesis of an association between COVID-19 worries and increased gaming has not been confirmed by statistical analysis. Shuai et al. (2021) also focused on children with ADHD: subjects were distinct in ADHD with and without PDMU (problematic digital media use). The ADHD group with PDMU had significantly worse symptoms in attention scores, in oppositional defiant scores, behavioral problems, and emotional difficulties when compared with the ADHD group without PDMU. The children with problematic digital media use presented significantly more impaired executive function on shift, emotional control, initiation, working memory, plan, and behavior regulation index, metacognition than the group without this condition. The total score on the depression self-rating scale for children and the screening child anxiety-related emotional disorders was significantly worse in ADHD with problematic digital media use group compared the other group. The ADHD children in the PDMU group spent more time on screens independently for playing video games than for using social media.

4. Discussion