Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

January 29, 2024

No matter the discipline, college success requires mastering several academic basics, including the body paragraph. This article will provide tips on drafting and editing a strong body paragraph before examining several body paragraph examples. Before we look at how to start a body paragraph and how to write a body paragraph for a college essay (or other writing assignment), let’s define what exactly a body paragraph is.

What is a Body Paragraph?

Simply put, a body paragraph consists of everything in an academic essay that does not constitute the introduction and conclusion. It makes up everything in between. In a five-paragraph, thesis-style essay (which most high schoolers encounter before heading off to college), there are three body paragraphs. Longer essays with more complex arguments will include many more body paragraphs.

We might correlate body paragraphs with bodily appendages—say, a leg. Both operate in a somewhat isolated way to perform specific operations, yet are integral to creating a cohesive, functioning whole. A leg helps the body sit, walk, and run. Like legs, body paragraphs work to move an essay along, by leading the reader through several convincing ideas. Together, these ideas, sometimes called topics, or points, work to prove an overall argument, called the essay’s thesis.

If you compared an essay on Kant’s theory of beauty to an essay on migratory birds, you’d notice that the body paragraphs differ drastically. However, on closer inspection, you’d probably find that they included many of the same key components. Most body paragraphs will include specific, detailed evidence, an analysis of the evidence, a conclusion drawn by the author, and several tie-ins to the larger ideas at play. They’ll also include transitions and citations leading the reader to source material. We’ll go into more detail on these components soon. First, let’s see if you’ve organized your essay so that you’ll know how to start a body paragraph.

How to Start a Body Paragraph

It can be tempting to start writing your college essay as soon as you sit down at your desk. The sooner begun, the sooner done, right? I’d recommend resisting that itch. Instead, pull up a blank document on your screen and make an outline. There are numerous reasons to make an outline, and most involve helping you stay on track. This is especially true of longer college papers, like the 60+ page dissertation some seniors are required to write. Even with regular writing assignments with a page count between 4-10, an outline will help you visualize your argumentation strategy. Moreover, it will help you order your key points and their relevant evidence from most to least convincing. This in turn will determine the order of your body paragraphs.

The most convincing sequence of body paragraphs will depend entirely on your paper’s subject. Let’s say you’re writing about Penelope’s success in outwitting male counterparts in The Odyssey . You may want to begin with Penelope’s weaving, the most obvious way in which Penelope dupes her suitors. You can end with Penelope’s ingenious way of outsmarting her own husband. Because this evidence is more ambiguous it will require a more nuanced analysis. Thus, it’ll work best as your final body paragraph, after readers have already been convinced of more digestible evidence. If in doubt, keep your body paragraph order chronological.

It can be worthwhile to consider your topic from multiple perspectives. You may decide to include a body paragraph that sets out to consider and refute an opposing point to your thesis. This type of body paragraph will often appear near the end of the essay. It works to erase any lingering doubts readers may have had, and requires strong rhetorical techniques.

How to Start a Body Paragraph, Continued

Once you’ve determined which key points will best support your argument and in what order, draft an introduction. This is a crucial step towards writing a body paragraph. First, it will set the tone for the rest of your paper. Second, it will require you to articulate your thesis statement in specific, concise wording. Highlight or bold your thesis statement, so you can refer back to it quickly. You should be looking at your thesis throughout the drafting of your body paragraphs.

Finally, make sure that your introduction indicates which key points you’ll be covering in your body paragraphs, and in what order. While this level of organization might seem like overkill, it will indicate to the reader that your entire paper is minutely thought-out. It will boost your reader’s confidence going in. They’ll feel reassured and open to your thought process if they can see that it follows a clear path.

Now that you have an essay outline and introduction, you’re ready to draft your body paragraphs.

How to Draft a Body Paragraph

At this point, you know your body paragraph topic, the key point you’re trying to make, and you’ve gathered your evidence. The next thing to do is write! The words highlighted in bold below comprise the main components that will make up your body paragraph. (You’ll notice in the body paragraph examples below that the order of these components is flexible.)

Start with a topic sentence . This will indicate the main point you plan to make that will work to support your overall thesis. Your topic sentence also alerts the reader to the change in topic from the last paragraph to the current one. In making this new topic known, you’ll want to create a transition from the last topic to this one.

Transitions appear in nearly every paragraph of a college essay, apart from the introduction. They create a link between disparate ideas. (For example, if your transition comes at the end of paragraph 4, you won’t need a second transition at the beginning of paragraph 5.) The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Writing Center has a page devoted to Developing Strategic Transitions . Likewise, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center offers help on paragraph transitions .

How to Draft a Body Paragraph for a College Essay ( Continued)

With the topic sentence written, you’ll need to prove your point through tangible evidence. This requires several sentences with various components. You’ll want to provide more context , going into greater detail to situate the reader within the topic. Next, you’ll provide evidence , often in the form of a quote, facts, or data, and supply a source citation . Citing your source is paramount. Sources indicate that your evidence is empirical and objective. It implies that your evidence is knowledge shared by others in the academic community. Sometimes you’ll want to provide multiple pieces of evidence, if the evidence is similar and can be grouped together.

After providing evidence, you must provide an interpretation and analysis of this evidence. In other words, use rhetorical techniques to paraphrase what your evidence seems to suggest. Break down the evidence further and explain and summarize it in new words. Don’t simply skip to your conclusion. Your evidence should never stand for itself. Why? Because your interpretation and analysis allow you to exhibit original, analytical, and critical thinking skills.

Depending on what evidence you’re using, you may repeat some of these components in the same body paragraph. This might look like: more context + further evidence + increased interpretation and analysis . All this will add up to proving and reaffirming your body paragraph’s main point . To do so, conclude your body paragraph by reformulating your thesis statement in light of the information you’ve given. I recommend comparing your original thesis statement to your paragraph’s concluding statement. Do they align? Does your body paragraph create a sound connection to the overall academic argument? If not, you’ll need to fix this issue when you edit your body paragraph.

How to Edit a Body Paragraph

As you go over each body paragraph of your college essay, keep this short checklist in mind.

- Consistency in your argument: If your key points don’t add up to a cogent argument, you’ll need to identify where the inconsistency lies. Often it lies in interpretation and analysis. You may need to improve the way you articulate this component. Try to think like a lawyer: how can you use this evidence to your advantage? If that doesn’t work, you may need to find new evidence. As a last resort, amend your thesis statement.

- Language-level persuasion. Use a broad vocabulary. Vary your sentence structure. Don’t repeat the same words too often, which can induce mental fatigue in the reader. I suggest keeping an online dictionary open on your browser. I find Merriam-Webster user-friendly, since it allows you to toggle between definitions and synonyms. It also includes up-to-date example sentences. Also, don’t forget the power of rhetorical devices .

- Does your writing flow naturally from one idea to the next, or are there jarring breaks? The editing stage is a great place to polish transitions and reinforce the structure as a whole.

Our first body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay .” Here’s the prompt: Write an essay that argues your position on the value of striving for perfection.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Striving for perfection can only lead us to shortchange ourselves. Instead, we should value learning, growth, and creativity and not worry whether we are first or fifth best.” Now let’s see how this writer builds an argument against perfection through one main point across two body paragraphs. (While this writer has split this idea into two paragraphs, one to address a problem and one to provide an alternative resolution, it could easily be combined into one paragraph.)

“Students often feel the need to be perfect in their classes, and this can cause students to struggle or stop making an effort in class. In elementary and middle school, for example, I was very nervous about public speaking. When I had to give a speech, my voice would shake, and I would turn very red. My teachers always told me “relax!” and I got Bs on Cs on my speeches. As a result, I put more pressure on myself to do well, spending extra time making my speeches perfect and rehearsing late at night at home. But this pressure only made me more nervous, and I started getting stomach aches before speaking in public.

“Once I got to high school, however, I started doing YouTube make-up tutorials with a friend. We made videos just for fun, and laughed when we made mistakes or said something silly. Only then, when I wasn’t striving to be perfect, did I get more comfortable with public speaking.”

Body Paragraph Example 1 Dissected

In this body paragraph example, the writer uses their personal experience as evidence against the value of striving for perfection. The writer sets up this example with a topic sentence that acts as a transition from the introduction. They also situate the reader in the classroom. The evidence takes the form of emotion and physical reactions to the pressure of public speaking (nervousness, shaking voice, blushing). Evidence also takes the form of poor results (mediocre grades). Rather than interpret the evidence from an analytical perspective, the writer produces more evidence to underline their point. (This method works fine for a narrative-style essay.) It’s clear that working harder to be perfect further increased the student’s nausea.

The writer proves their point in the second paragraph, through a counter-example. The main point is that improvement comes more naturally when the pressure is lifted; when amusement is possible and mistakes aren’t something to fear. This point ties back in with the thesis, that “we should value learning, growth, and creativity” over perfection.

This second body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay .” Here’s an abridged version of the prompt: Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.” Now read the body paragraph example, below.

“To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.”

Body Paragraph Example 2 Dissected

The first sentence in this body paragraph example indicates that the topic is transitioning into biblical references as a means of motivating ordinary citizens. The evidence comes as quotes taken from Obama’s speech. One is a reference to God, and the other an allusion to a story from the bible. The subsequent interpretation and analysis demonstrate that Obama’s biblical references imply a deeper, moral and spiritual significance. The concluding sentence draws together the morality inherent in equal rights with Rosa Parks’ power to spark change. Through the words “no political power or fortune,” and “moral balance,” the writer ties the point proven in this body paragraph back to the thesis statement. Obama promises that “All of us” (no matter how small our influence) “are capable of achieving greater good”—a greater moral good.

What’s Next?

Before you body paragraphs come the start and, after your body paragraphs, the conclusion, of course! If you’ve found this article helpful, be sure to read up on how to start a college essay and how to end a college essay .

You may also find the following blogs to be of interest:

- 6 Best Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- How to Write the Community Essay

- How to Write the Why this Major? Essay

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

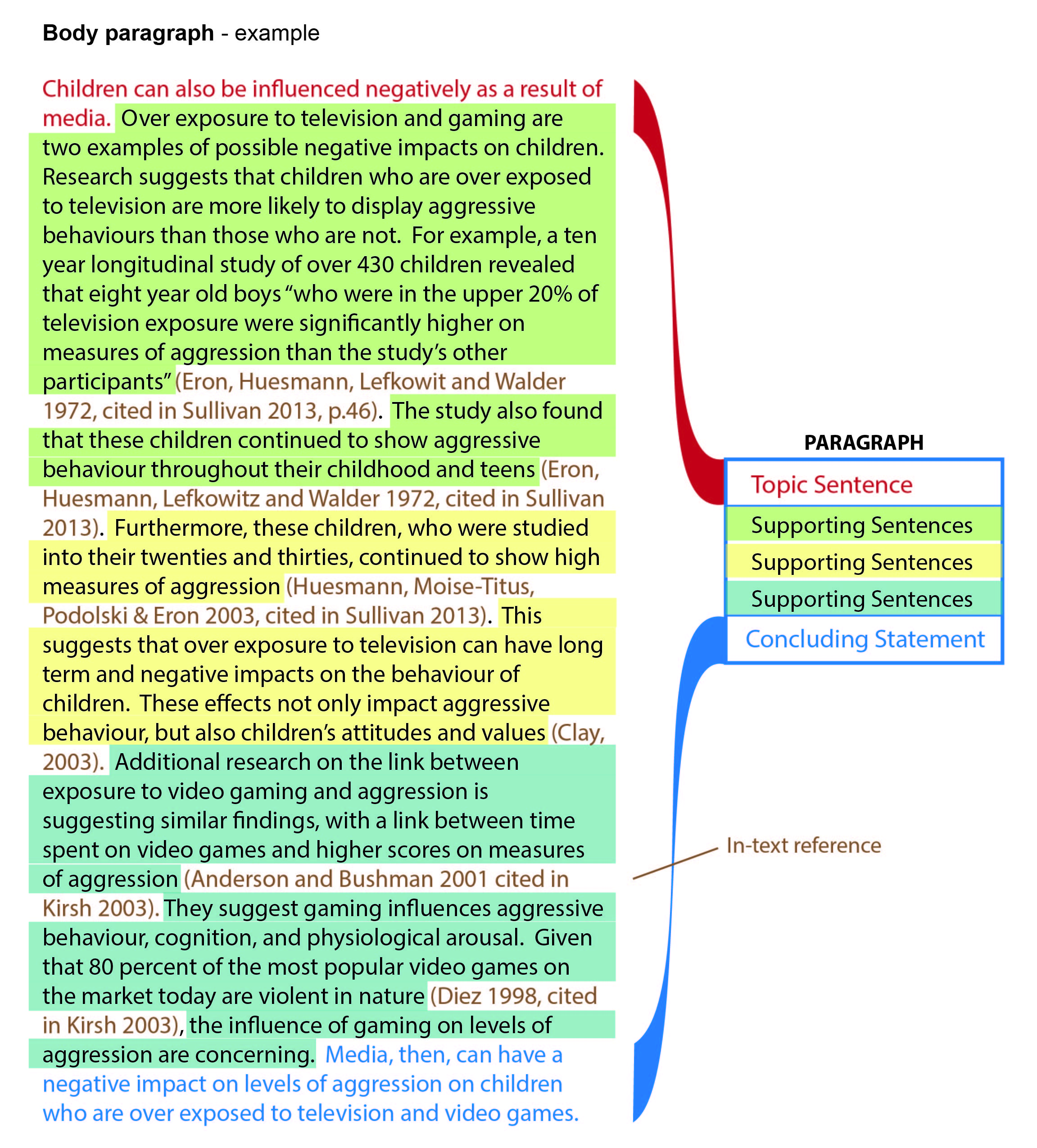

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

The Beginner's Guide to Writing an Essay | Steps & Examples

An academic essay is a focused piece of writing that develops an idea or argument using evidence, analysis, and interpretation.

There are many types of essays you might write as a student. The content and length of an essay depends on your level, subject of study, and course requirements. However, most essays at university level are argumentative — they aim to persuade the reader of a particular position or perspective on a topic.

The essay writing process consists of three main stages:

- Preparation: Decide on your topic, do your research, and create an essay outline.

- Writing : Set out your argument in the introduction, develop it with evidence in the main body, and wrap it up with a conclusion.

- Revision: Check your essay on the content, organization, grammar, spelling, and formatting of your essay.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Essay writing process, preparation for writing an essay, writing the introduction, writing the main body, writing the conclusion, essay checklist, lecture slides, frequently asked questions about writing an essay.

The writing process of preparation, writing, and revisions applies to every essay or paper, but the time and effort spent on each stage depends on the type of essay .

For example, if you’ve been assigned a five-paragraph expository essay for a high school class, you’ll probably spend the most time on the writing stage; for a college-level argumentative essay , on the other hand, you’ll need to spend more time researching your topic and developing an original argument before you start writing.

| 1. Preparation | 2. Writing | 3. Revision |

|---|---|---|

| , organized into Write the | or use a for language errors |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Before you start writing, you should make sure you have a clear idea of what you want to say and how you’re going to say it. There are a few key steps you can follow to make sure you’re prepared:

- Understand your assignment: What is the goal of this essay? What is the length and deadline of the assignment? Is there anything you need to clarify with your teacher or professor?

- Define a topic: If you’re allowed to choose your own topic , try to pick something that you already know a bit about and that will hold your interest.

- Do your research: Read primary and secondary sources and take notes to help you work out your position and angle on the topic. You’ll use these as evidence for your points.

- Come up with a thesis: The thesis is the central point or argument that you want to make. A clear thesis is essential for a focused essay—you should keep referring back to it as you write.

- Create an outline: Map out the rough structure of your essay in an outline . This makes it easier to start writing and keeps you on track as you go.

Once you’ve got a clear idea of what you want to discuss, in what order, and what evidence you’ll use, you’re ready to start writing.

The introduction sets the tone for your essay. It should grab the reader’s interest and inform them of what to expect. The introduction generally comprises 10–20% of the text.

1. Hook your reader

The first sentence of the introduction should pique your reader’s interest and curiosity. This sentence is sometimes called the hook. It might be an intriguing question, a surprising fact, or a bold statement emphasizing the relevance of the topic.

Let’s say we’re writing an essay about the development of Braille (the raised-dot reading and writing system used by visually impaired people). Our hook can make a strong statement about the topic:

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

2. Provide background on your topic

Next, it’s important to give context that will help your reader understand your argument. This might involve providing background information, giving an overview of important academic work or debates on the topic, and explaining difficult terms. Don’t provide too much detail in the introduction—you can elaborate in the body of your essay.

3. Present the thesis statement

Next, you should formulate your thesis statement— the central argument you’re going to make. The thesis statement provides focus and signals your position on the topic. It is usually one or two sentences long. The thesis statement for our essay on Braille could look like this:

As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness.

4. Map the structure

In longer essays, you can end the introduction by briefly describing what will be covered in each part of the essay. This guides the reader through your structure and gives a preview of how your argument will develop.

The invention of Braille marked a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by blind and visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Write your essay introduction

The body of your essay is where you make arguments supporting your thesis, provide evidence, and develop your ideas. Its purpose is to present, interpret, and analyze the information and sources you have gathered to support your argument.

Length of the body text

The length of the body depends on the type of essay. On average, the body comprises 60–80% of your essay. For a high school essay, this could be just three paragraphs, but for a graduate school essay of 6,000 words, the body could take up 8–10 pages.

Paragraph structure

To give your essay a clear structure , it is important to organize it into paragraphs . Each paragraph should be centered around one main point or idea.

That idea is introduced in a topic sentence . The topic sentence should generally lead on from the previous paragraph and introduce the point to be made in this paragraph. Transition words can be used to create clear connections between sentences.

After the topic sentence, present evidence such as data, examples, or quotes from relevant sources. Be sure to interpret and explain the evidence, and show how it helps develop your overall argument.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

See the full essay example

The conclusion is the final paragraph of an essay. It should generally take up no more than 10–15% of the text . A strong essay conclusion :

- Returns to your thesis

- Ties together your main points

- Shows why your argument matters

A great conclusion should finish with a memorable or impactful sentence that leaves the reader with a strong final impression.

What not to include in a conclusion

To make your essay’s conclusion as strong as possible, there are a few things you should avoid. The most common mistakes are:

- Including new arguments or evidence

- Undermining your arguments (e.g. “This is just one approach of many”)

- Using concluding phrases like “To sum up…” or “In conclusion…”

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Write your essay conclusion

Checklist: Essay

My essay follows the requirements of the assignment (topic and length ).

My introduction sparks the reader’s interest and provides any necessary background information on the topic.

My introduction contains a thesis statement that states the focus and position of the essay.

I use paragraphs to structure the essay.

I use topic sentences to introduce each paragraph.

Each paragraph has a single focus and a clear connection to the thesis statement.

I make clear transitions between paragraphs and ideas.

My conclusion doesn’t just repeat my points, but draws connections between arguments.

I don’t introduce new arguments or evidence in the conclusion.

I have given an in-text citation for every quote or piece of information I got from another source.

I have included a reference page at the end of my essay, listing full details of all my sources.

My citations and references are correctly formatted according to the required citation style .

My essay has an interesting and informative title.

I have followed all formatting guidelines (e.g. font, page numbers, line spacing).

Your essay meets all the most important requirements. Our editors can give it a final check to help you submit with confidence.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- How long is an essay? Guidelines for different types of essay

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

More interesting articles

- Checklist for academic essays | Is your essay ready to submit?

- Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

- Generate topic ideas for an essay or paper | Tips & techniques

- How to revise an essay in 3 simple steps

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

- How to write a descriptive essay | Example & tips

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

- How to write an essay outline | Guidelines & examples

- How to write an expository essay

- How to write the body of an essay | Drafting & redrafting

- Kinds of argumentative academic essays and their purposes

- Organizational tips for academic essays

- The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples

- Transition sentences | Tips & examples for clear writing

What is your plagiarism score?

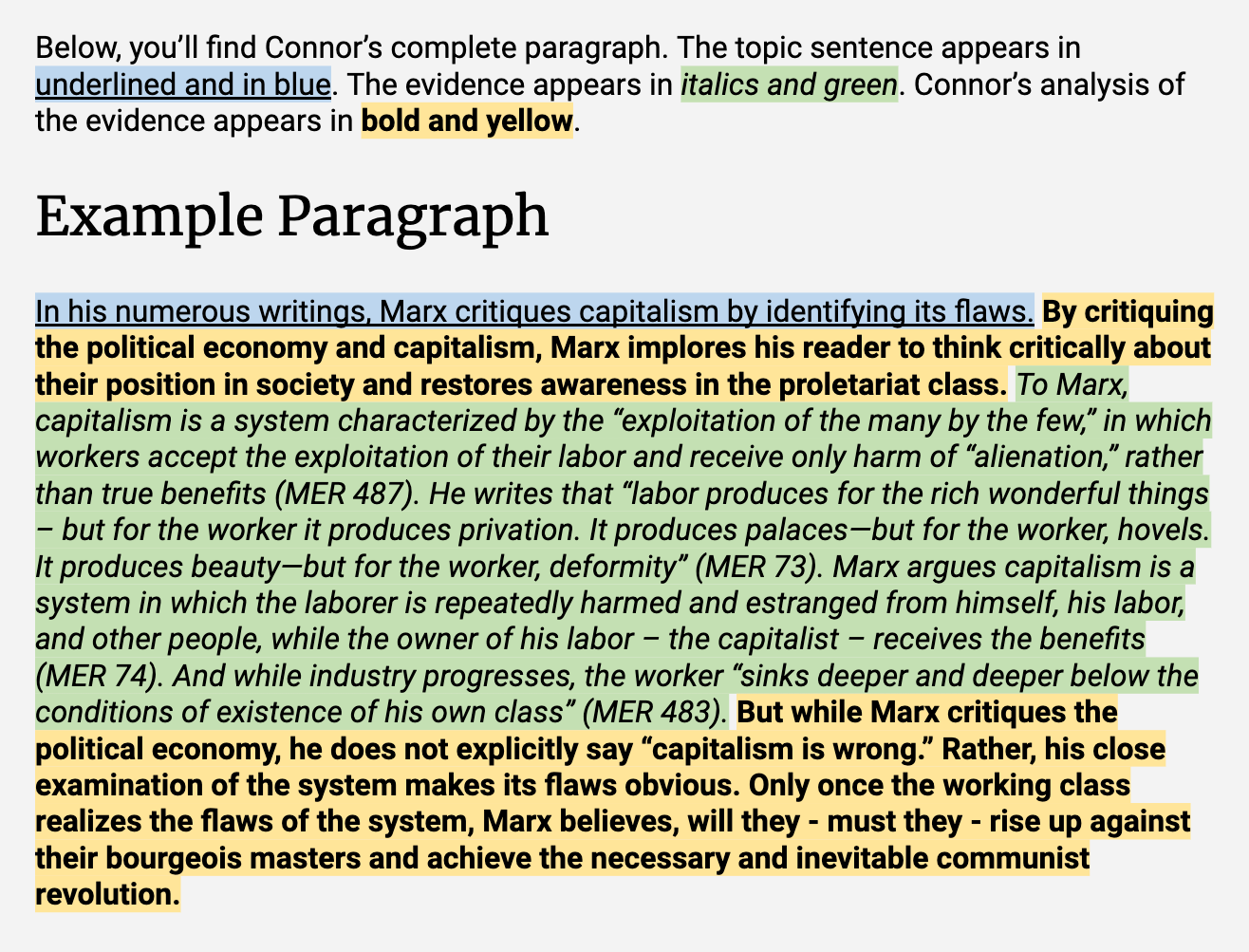

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

10 min read

How to write strong essay body paragraphs (with examples)

In this blog post, we'll discuss how to write clear, convincing essay body paragraphs using many examples. We'll also be writing paragraphs together. By the end, you'll have a good understanding of how to write a strong essay body for any topic.

Table of Contents

Introduction, how to structure a body paragraph, creating an outline for our essay body, 1. a strong thesis statment takes a stand, 2. a strong thesis statement allows for debate, 3. a strong thesis statement is specific, writing the first essay body paragraph, how not to write a body paragraph, writing the second essay body paragraph.

After writing a great introduction to our essay, let's make our case in the body paragraphs. These are where we will present our arguments, back them up with evidence, and, in most cases, refute counterarguments. Introductions are very similar across the various types of essays. For example, an argumentative essay's introduction will be near identical to an introduction written for an expository essay. In contrast, the body paragraphs are structured differently depending on the type of essay.

In an expository essay, we are investigating an idea or analyzing the circumstances of a case. In contrast, we want to make compelling points with an argumentative essay to convince readers to agree with us.

The most straightforward technique to make an argument is to provide context first, then make a general point, and lastly back that point up in the following sentences. Not starting with your idea directly but giving context first is crucial in constructing a clear and easy-to-follow paragraph.

How to ideally structure a body paragraph:

- Provide context

- Make your thesis statement

- Support that argument

Now that we have the ideal structure for an argumentative essay, the best step to proceed is to outline the subsequent paragraphs. For the outline, we'll be writing one sentence that is simple in wording and describes the argument that we'll make in that paragraph concisely. Why are we doing that? An outline does more than give you a structure to work off of in the following essay body, thereby saving you time. It also helps you not to repeat yourself or, even worse, to accidentally contradict yourself later on.

While working on the outline, remember that revising your initial topic sentences is completely normal. They do not need to be flawless. Starting the outline with those thoughts can help accelerate writing the entire essay and can be very beneficial in avoiding writer's block.

For the essay body, we'll be proceeding with the topic we've written an introduction for in the previous article - the dangers of social media on society.

These are the main points I would like to make in the essay body regarding the dangers of social media:

Amplification of one's existing beliefs

Skewed comparisons

What makes a polished thesis statement?

Now that we've got our main points, let's create our outline for the body by writing one clear and straightforward topic sentence (which is the same as a thesis statement) for each idea. How do we write a great topic sentence? First, take a look at the three characteristics of a strong thesis statement.

Consider this thesis statement:

'While social media can have some negative effects, it can also be used positively.'

What stand does it take? Which negative and positive aspects does the author mean? While this one:

'Because social media is linked to a rise in mental health problems, it poses a danger to users.'

takes a clear stand and is very precise about the object of discussion.

If your thesis statement is not arguable, then your paper will not likely be enjoyable to read. Consider this thesis statement:

'Lots of people around the globe use social media.'

It does not allow for much discussion at all. Even if you were to argue that more or fewer people are using it on this planet, that wouldn't make for a very compelling argument.

'Although social media has numerous benefits, its various risks, including cyberbullying and possible addiction, mostly outweigh its benefits.'

Whether or not you consider this statement true, it allows for much more discussion than the previous one. It provides a basis for an engaging, thought-provoking paper by taking a position that you can discuss.

A thesis statement is one sentence that clearly states what you will discuss in that paragraph. It should give an overview of the main points you will discuss and show how these relate to your topic. For example, if you were to examine the rapid growth of social media, consider this thesis statement:

'There are many reasons for the rise in social media usage.'

That thesis statement is weak for two reasons. First, depending on the length of your essay, you might need to narrow your focus because the "rise in social media usage" can be a large and broad topic you cannot address adequately in a few pages. Secondly, the term "many reasons" is vague and does not give the reader an idea of what you will discuss in your paper.

In contrast, consider this thesis statement:

'The rise in social media usage is due to the increasing popularity of platforms like Facebook and Twitter, allowing users to connect with friends and share information effortlessly.'

Why is this better? Not only does it abide by the first two rules by allowing for debate and taking a stand, but this statement also narrows the subject down and identifies significant reasons for the increasing popularity of social media.

In conclusion : A strong thesis statement takes a clear stand, allows for discussion, and is specific.

Let's make use of how to write a good thopic sentence and put it into practise for our two main points from before. This is what good topic sentences could look like:

Echo chambers facilitated by social media promote political segregation in society.

Applied to the second argument:

Viewing other people's lives online through a distorted lens can lead to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as unrealistic expectations about one's life.

These topic sentences will be a very convenient structure for the whole body of our essay. Let's build out the first body paragraph, then closely examine how we did it so you can apply it to your essay.

Example: First body paragraph

If social media users mostly see content that reaffirms their existing beliefs, it can create an "echo chamber" effect. The echo chamber effect describes the user's limited exposure to diverse perspectives, making it challenging to examine those beliefs critically, thereby contributing to society's political polarization. This polarization emerges from social media becoming increasingly based on algorithms, which cater content to users based on their past interactions on the site. Further contributing to this shared narrative is the very nature of social media, allowing politically like-minded individuals to connect (Sunstein, 2018). Consequently, exposure to only one side of the argument can make it very difficult to see the other side's perspective, marginalizing opposing viewpoints. The entrenchment of one's beliefs by constant reaffirmation and amplification of political ideas results in segregation along partisan lines.

Sunstein, C. R (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

In the first sentence, we provide context for the argument that we are about to make. Then, in the second sentence, we clearly state the topic we are addressing (social media contributing to political polarization).

Our topic sentence tells readers that a detailed discussion of the echo chamber effect and its consequences is coming next. All the following sentences, which make up most of the paragraph, either a) explain or b) support this point.

Finally, we answer the questions about how social media facilitates the echo chamber effect and the consequences. Try implementing the same structure in your essay body paragraph to allow for a logical and cohesive argument.

These paragraphs should be focused, so don't incorporate multiple arguments into one. Squeezing ideas into a single paragraph makes it challenging for readers to follow your reasoning. Instead, reserve each body paragraph for a single statement to be discussed and only switch to the next section once you feel that you thoroughly explained and supported your topic sentence.

Let's look at an example that might seem appropriate initially but should be modified.

Negative example: Try identifying the main argument

Over the past decade, social media platforms have become increasingly popular methods of communication and networking. However, these platforms' algorithmic nature fosters echo chambers or online spaces where users only encounter information that reinforces their existing beliefs. This echo chamber effect can lead to a lack of understanding or empathy for those with different perspectives and can even amplify the effects of confirmation bias. The same principle of one-sided exposure to opinions can be abstracted and applied to the biased subjection to lifestyles we see on social media. The constant exposure to these highly-curated and often unrealistic portrayals of other people's lives can lead us to believe that our own lives are inadequate in comparison. These feelings of inadequacy can be especially harmful to young people, who are still developing their sense of self.

Let's analyze this essay paragraph. Introducing the topic sentence by stating the social functions of social media is very useful because it provides context for the following argument. Naming those functions in the first sentence also allows for a smooth transition by contrasting the initial sentence ("However, ...") with the topic sentence. Also, the topic sentence abides by our three rules for creating a strong thesis statement:

- Taking a clear stand: algorithms are substantial contributors to the echo chamber effect

- Allowing for debate: there is literature rejecting this claim

- Being specific: analyzing a specific cause of the effect (algorithms).

So, where's the problem with this body paragraph?

It begins with what seems like a single argument (social media algorithms contributing to the echo chamber effect). Yet after addressing the consequences of the echo-chamber effect right after the thesis sentence, the author applies the same principle to a whole different topic. At the end of the paragraph, the reader is probably feeling confused. What was the paragraph trying to achieve in the first place?

We should place the second idea of being exposed to curated lifestyles in a separate section instead of shoehorning it into the end of the first one. All sentences following the thesis statement should either explain it or provide evidence (refuting counterarguments falls into this category, too).

With our first body paragraph done and having seen an example of what to avoid, let's take the topic of being exposed to curated lifestyles through social media and construct a separate body paragraph for it. We have already provided sufficient context for the reader to follow our argument, so it is unnecessary for this particular paragraph.

Body paragraph 2

Another cause for social media's destructiveness is the users' inclination to only share the highlights of their lives on social media, consequently distorting our perceptions of reality. A highly filtered view of their life leads to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as a distorted understanding of what is considered ordinary (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, frequent social media use is linked to decreased self-esteem and body satisfaction (Perloff, 2014). One way social media can provide a curated view of people's lives is through filters, making photos look more radiant, shadier, more or less saturated, and similar. Further, editing tools allow people to fundamentally change how their photos and videos look before sharing them, allowing for inserting or removing certain parts of the image. Editing tools give people considerable control over how their photos and videos look before sharing them, thereby facilitating the curation of one's online persona.

Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women's Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 71, 363–377 (2014).

Liu, Hongbo & Wu, Laurie & Li, Xiang. (2018). Social Media Envy: How Experience Sharing on Social Networking Sites Drives Millennials' Aspirational Tourism Consumption. Journal of Travel Research. 58. 10.1177/0047287518761615.

Dr. Jacob Neumann put it this way in his book A professors guide to writing essays: 'If you've written strong and clear topic sentences, you're well on your way to creating focused paragraphs.'

They provide the basis for each paragraph's development and content, allowing you not to get caught up in the details and lose sight of the overall objective. It's crucial not to neglect that step. Apply these principles to your essay body, whatever the topic, and you'll set yourself up for the best possible results.

Sources used for creating this article

- Writing a solid thesis statement : https://www.vwu.edu/academics/academic-support/learning-center/pdfs/Thesis-Statement.pdf

- Neumann, Jacob. A professor's guide to writing essays. 2016.

Follow the Journey

Hello! I'm Josh, the founder of Wordful. We aim to make a product that makes writing amazing content easy and fun. Sign up to gain access first when Wordful goes public!

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Traditional Academic Essays In Three Parts

Part i: the introduction.

An introduction is usually the first paragraph of your academic essay. If you’re writing a long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to introduce your topic to your reader. A good introduction does 2 things:

- Gets the reader’s attention. You can get a reader’s attention by telling a story, providing a statistic, pointing out something strange or interesting, providing and discussing an interesting quote, etc. Be interesting and find some original angle via which to engage others in your topic.

- Provides a specific and debatable thesis statement. The thesis statement is usually just one sentence long, but it might be longer—even a whole paragraph—if the essay you’re writing is long. A good thesis statement makes a debatable point, meaning a point someone might disagree with and argue against. It also serves as a roadmap for what you argue in your paper.

Part II: The Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you prove your thesis and move you along a compelling trajectory from your introduction to your conclusion. If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay:

Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph. All of the sentences in the paragraph connect to it. Keep in mind that main ideas are…

- like labels. They appear in the first sentence of the paragraph and tell your reader what’s inside the paragraph.

- arguable. They’re not statements of fact; they’re debatable points that you prove with evidence.

- focused. Make a specific point in each paragraph and then prove that point.

Evidence. The parts of a paragraph that prove the main idea. You might include different types of evidence in different sentences. Keep in mind that different disciplines have different ideas about what counts as evidence and they adhere to different citation styles. Examples of evidence include…

- quotations and/or paraphrases from sources.

- facts , e.g. statistics or findings from studies you’ve conducted.

- narratives and/or descriptions , e.g. of your own experiences.

Analysis. The parts of a paragraph that explain the evidence. Make sure you tie the evidence you provide back to the paragraph’s main idea. In other words, discuss the evidence.

Transition. The part of a paragraph that helps you move fluidly from the last paragraph. Transitions appear in topic sentences along with main ideas, and they look both backward and forward in order to help you connect your ideas for your reader. Don’t end paragraphs with transitions; start with them.

Keep in mind that MEAT does not occur in that order. The “ T ransition” and the “ M ain Idea” often combine to form the first sentence—the topic sentence—and then paragraphs contain multiple sentences of evidence and analysis. For example, a paragraph might look like this: TM. E. E. A. E. E. A. A.

Part III: The Conclusion

A conclusion is the last paragraph of your essay, or, if you’re writing a really long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to conclude. A conclusion typically does one of two things—or, of course, it can do both:

- Summarizes the argument. Some instructors expect you not to say anything new in your conclusion. They just want you to restate your main points. Especially if you’ve made a long and complicated argument, it’s useful to restate your main points for your reader by the time you’ve gotten to your conclusion. If you opt to do so, keep in mind that you should use different language than you used in your introduction and your body paragraphs. The introduction and conclusion shouldn’t be the same.

- For example, your argument might be significant to studies of a certain time period .

- Alternately, it might be significant to a certain geographical region .

- Alternately still, it might influence how your readers think about the future . You might even opt to speculate about the future and/or call your readers to action in your conclusion.

Handout by Dr. Liliana Naydan. Do not reproduce without permission.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

- The Writing Process

- Addressing the Prompt

- Writing Skill: Development

- Originality

- Timed Writing (Expectations)

- Integrated Writing (Writing Process)

- Introduction to Academic Essays

- Organization

- Introduction Paragraphs

Body Paragraphs

- Conclusion Paragraphs

- Example Essay 1

- Example Essay 2

- Timed Writing (The Prompt)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 1)

- Process Essays

- Process Essay Example 1

- Process Essay Example 2

- Writing Skill: Unity

- Revise A Process Essay

- Timed Writing (Choose a Position)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 2)

- Comparison Essays

- Comparison Essay Example 1

- Comparison Essay Example 2

- Writing Skill: Cohesion

- Revise A Comparison Essay

- Timed Writing (Plans & Problems)

- Integrated Writing (Word Choice)

- Problem/Solution Essays

- Problem/Solution Essay Example 1

- Problem/Solution Example Essay 2

- Writing Skill: Summary

- Revise A Problem/Solution Essay

- Timed Writing (Revising)

- Integrated Writing (Summary)

- More Writing Skills

- Punctuation

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences Part 1

- Complex Sentences Part 2

- Using Academic Vocabulary

- Translations

Choose a Sign-in Option

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Body paragraphs should all work to support your thesis by explaining why or how your thesis is true. There are three types of sentences in each body paragraph: topic sentences, supporting sentences, and concluding sentences.

Topic sentences

A topic sentence states the focus of the paragraph. The rest of the body paragraph will give evidence and explanations that show why or how your topic sentence is true. A topic sentence is very similar to a thesis. The thesis is the main idea of the essay; a topic sentence is the main idea of a body paragraph. Many of the same characteristics apply to topic sentences that apply to theses. The biggest differences will be the location of the sentence and the scope of the ideas.

An effective topic sentence—

- clearly supports the thesis statement.

- is usually at the beginning of a body paragraph.

- controls the content of all of the supporting sentences in its paragraph.

- is a complete sentence.

- does not announce the topic (e.g., “I’m going to talk about exercise.”).

- should not be t oo general (e.g., “Exercise is good.”).

- should not be too specific (e.g., “Exercise decreases the chance of developing diabetes, heart disease, asthma, osteoporosis, depression, and anxiety.”).

Supporting sentences

Your body paragraph needs to explain why or how your topic sentence is true. The sentences that support your topic sentence are called supporting sentences. You can have many types of supporting sentences. Supporting sentences can give examples, explanations, details, descriptions, facts, reasons, etc.

| Topic Sentence | Exercise improves you mental health. |

| Supporting Sentences | Exercise is the healthiest way to deal with stress. Exercise can influence the balance of chemicals in our bodies. Exercise also helps us think more clearly. |

Concluding sentences

Your final statement should conclude your paragraph logically. Concluding sentences can restate the main idea of your paragraph, state an opinion, make a prediction, give advice, etc. New ideas should not be presented in your concluding sentence.

Restatement of topic sentence | Because it makes your body healthier, exercise is extremely important. |

| Opinion | These health benefits show that exercise is not a waste of time. |

| Prediction | When people see these health benefits, they will want to exercise more. |

| Advice | Everyone should exercise regularly to obtain these amazing health benefits. |

Exercise 1: Analyze a topic sentence.

Read the example body paragraph below to complete this exercise on a piece of paper.

Prompt: Why is exercise important?

Thesis: Exercise is essential because it improves overall physical and mental health.

Because it makes your body healthier, exercise is extremely important. One of the physical benefits of exercise is having stronger muscles. The only way to make your muscles stronger is to use them, and exercises like crunches, squats, lunges, push-ups, and weight-lifting are good examples of exercises that strengthen your muscles. Another benefit of exercise is that it lowers your heart rate. A slow heart rate can show that our hearts are working more efficiently and they don’t have to pump as many times in a minute to get blood to our organs. Related to our heart beating more efficiently, our blood pressure decreases. These are just some of the incredible health benefits of exercise.

Find the topic sentence. Use the following criteria to evaluate the topic sentence.

- Does the topic sentence clearly support the thesis statement?

- Is the topic sentence at the beginning of the body paragraph?

- Does the topic sentence control the content of all the supporting sentences?

- Is the topic sentence a complete sentence?

- Does the topic sentence announce the topic?

- Is the topic sentence too general? Is it too specific?

Exercise 2: Identify topic sentences.

Each group of sentences has three supporting sentences and one topic sentence. The topic sentence must be broad enough to include all of the supporting sentences. In each group of sentences, choose which sentence is the topic sentence. Write the letter of the topic sentence on the line given.

Group 1: Topic sentence: _________

- In southern Utah, hikers enjoy the scenic trails in Zion National Park.

- Many cities in Utah have created hiking trails in city parks for people to use.

- There are hiking paths in Utah’s Rocky Mountains that provide beautiful views.

- Hikers all over Utah can access hiking trails and enjoy nature.

Group 2: Topic sentence: _________

- People in New York speak many different languages.

- New York is a culturally diverse city.

- People in New York belong to many different religions.

- Restaurants in New York have food from all over the world.

Group 3: Topic sentence: _________

- Websites like YouTube have video tutorials that teach many different skills.

- Computer programs like PowerPoint are used in classrooms to teach new concepts.

- Technology helps people learn things in today’s world.

- Many educational apps have been created to help children in school.

Group 4: Topic sentence: _________

- Museums at BYU host events on the weekends for students.

- There are many fun activities for students at BYU on the weekends.

- There are incredible student concerts at BYU on Friday and Saturday nights.

- BYU clubs plan exciting activities for students to do on the weekends.

Group 5: Topic sentence: _________

- Some places have a scent that people remember when they think of that place.

- The smell of someone’s cologne can trigger a memory of that person.

- Smelling certain foods can bring back memories of eating that food.

- Many different memories can be connected to specific smells.

Exercise 3: Write topic sentences

Read each paragraph. On a piece of paper, write a topic sentence on the line at the beginning of the paragraph.

1._______ The first difference is that you have more privacy in a private room than in a shared room. You can go to your room to have a private phone call or Skype with your family and you are not bothered by other people. When you share your room, it can be hard to find private time when you can do things alone. Another difference is that it is lonelier in a private room than in a shared room. When you share your room with a roommate, you have someone that you can talk to. Frequently when you have a private room, you are alone more often. These two housing options are very different.

2. _______ People like to eat chocolate because it has many delicious flavors. For example, there are mint chocolates, milk chocolates, dark chocolates, white chocolates, chocolates with honey, and chocolates with nuts. Another reason people like to eat chocolate is because it reduces stress, which can help people to relax and feel better. The last reason people like to eat chocolate is because it can be cooked in many different ways. You can eat chocolate candies, mix chocolate with warm milk to drink, or prepare a chocolate dessert. These reasons are some of the reasons that people like to eat chocolate.

3. _______ A respectful roommate does not leave the main areas of the apartment messy after they use them. For example, they wash their dishes instead of leaving dirty pots and pans on the stove. They also don’t borrow things from other roommates without asking to use them first. In addition to respecting everyone’s need for space and their possessions, the ideal roommate is respectful of his or her roommate’s schedule. For example, if one roommate is asleep and the other roommates needs to study, the ideal roommate goes to the kitchen or living room instead of waking up the sleeping roommate. These simple gestures of respect make a roommate an excellent person to share an apartment with.

Exercise 4: Identify good supporting sentences.

Read the topic sentence. Then circle which sentences would be good supporting sentences.

Topic Sentence: Eating pancakes for breakfast saves time and money.

- Pancakes can be prepared in large quantities and then frozen, so the time it takes to cook breakfast is only a few minutes.

- Pancakes are very inexpensive to make because you only need a few ingredients.

- Pancakes are delicious and can be prepared in a variety of flavors.

- Pancakes save money because you can buy a big box of mix and only make what you need; you don’t waste money because you can save the extra mix for another time.

- Fresh fruit is a really quick breakfast because you only need to wash it and eat it.

Exercise 5: Identify good concluding sentences.

Read the topic sentence. Then circle which sentences would be good concluding sentences.

Topic Sentence: A shared room offers students a more social experience.

- Students who want more social interaction should have a shared room.

- A shared room is not good for students who work late.

- Everyone loves having a shared room.

- These examples illustrate how much more social a shared room can be.

- Really social students will enjoy having a shared room.

Exercise 6: Write concluding sentences.

On a piece of paper, write a concluding sentence at the end of each paragraph.

1. New York is a culturally diverse city. This culture is continually broadened because people immigrate from all over the world bringing different religions, food, and languages with them. This city has people that speak over 30 languages, including Arabic, Mandarin, Untu, Russian, and Polish. There are also more than 20 major religions represented by citizens of New York. These citizens brought more than their language and religion with them, however. They also brought traditional foods from their countries. _______

2. Technology helps people learn things in today’s world. This educational technology includes various websites, apps, programs, and many more things. Popular websites that are used for education include YouTube, TED, Canvas, and CrashCourse. Similarly, there are a variety of educational apps. These apps help users learn languages, history, math, and other practical skills. Computer programs are yet another way to use technology as a way to help people learn. Programs like PowerPoint are frequently used in classrooms as a means to deliver visual support to a lecture or presentation. This visual support aids learning and retention. _______

This content is provided to you freely by BYU Open Learning Network.

Access it online or download it at https://open.byu.edu/academic_a_writing/body_paragraphs .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Body Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap-up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: T ransition, T opic sentence, specific E vidence and analysis, and a B rief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant ) –TTEB!

- A T ransition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

- A T opic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific E vidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A B rief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument :

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage , clear purpose , and great ), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E. Lee.

The following is a clear example of deduction gone awry:

- Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

- Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

- Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will make a good pet is invalid.

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme. Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. Therefore, the unstated premise is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic structure:

- Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

- Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

- Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid argument, you may want to look at the United States Declaration of Independence. The first section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together in a compelling conclusion.

Essay Papers Writing Online

Mastering the art of essay writing – a comprehensive guide.

Essay writing is a fundamental skill that every student needs to master. Whether you’re in high school, college, or beyond, the ability to write a strong, coherent essay is essential for academic success. However, many students find the process of writing an essay daunting and overwhelming.

This comprehensive guide is here to help you navigate the intricate world of essay writing. From understanding the basics of essay structure to mastering the art of crafting a compelling thesis statement, we’ve got you covered. By the end of this guide, you’ll have the tools and knowledge you need to write an outstanding essay that will impress your teachers and classmates alike.

So, grab your pen and paper (or fire up your laptop) and let’s dive into the ultimate guide to writing an essay. Follow our tips and tricks, and you’ll be well on your way to becoming a skilled and confident essay writer!

The Art of Essay Writing: A Comprehensive Guide

Essay writing is a skill that requires practice, patience, and attention to detail. Whether you’re a student working on an assignment or a professional writing for publication, mastering the art of essay writing can help you communicate your ideas effectively and persuasively.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the key elements of a successful essay, including how to choose a topic, structure your essay, and craft a compelling thesis statement. We’ll also discuss the importance of research, editing, and proofreading, and provide tips for improving your writing style and grammar.

By following the advice in this guide, you can become a more confident and skilled essay writer, capable of producing high-quality, engaging essays that will impress your readers and achieve your goals.

Understanding the Essay Structure

When it comes to writing an essay, understanding the structure is key to producing a cohesive and well-organized piece of writing. An essay typically consists of three main parts: an introduction, the body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Introduction: The introduction is where you introduce your topic and provide some background information. It should also include your thesis statement, which is the main idea or argument that you will be discussing in the essay.

Body paragraphs: The body of the essay is where you present your supporting evidence and arguments. Each paragraph should focus on a separate point and include evidence to back up your claims. Remember to use transition words to link your ideas together cohesively.

Conclusion: The conclusion is where you wrap up your essay by summarizing your main points and restating your thesis. It is also a good place to make any final thoughts or reflections on the topic.

Understanding the structure of an essay will help you write more effectively and communicate your ideas clearly to your readers.

Choosing the Right Topic for Your Essay

One of the most crucial steps in writing a successful essay is selecting the right topic. The topic you choose will determine the direction and focus of your writing, so it’s important to choose wisely. Here are some tips to help you select the perfect topic for your essay:

| Choose a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Writing about something you enjoy will make the process more enjoyable and your enthusiasm will come through in your writing. | |

| Do some preliminary research to see what topics are available and what resources are out there. This will help you narrow down your choices and find a topic that is both interesting and manageable. | |

| Think about who will be reading your essay and choose a topic that will resonate with them. Consider their interests, knowledge level, and any biases they may have when selecting a topic. | |

| Take some time to brainstorm different topic ideas. Write down all the potential topics that come to mind, and then evaluate each one based on relevance, interest, and feasibility. | |

| Try to choose a topic that offers a unique perspective or angle. Avoid overly broad topics that have been extensively covered unless you have a fresh take to offer. |

By following these tips and considering your interests, audience, and research, you can choose a topic that will inspire you to write an engaging and compelling essay.

Research and Gathering Information

When writing an essay, conducting thorough research and gathering relevant information is crucial. Here are some tips to help you with your research:

| Make sure to use reliable sources such as academic journals, books, and reputable websites. Avoid using sources that are not credible or biased. | |