Case study: Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data breach scandal

Cambridge Analytica is a federal data analytics, marketing, and consulting firm based in London, UK, that is accused of illegally obtaining Facebook data and using it to determine a variety of federal crusades. These crusades include those of American Senator Ted Cruz and, to an extent, Donald Trump and the Leave-EU Brexit campaign, which resulted in the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. In 2018, the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal was a major disgrace, with Cambridge Analytica collecting the private data of millions of people’s Facebook profiles without their permission and using it for Political Advertising. It was defined as a watershed flash in the country’s understanding of private data, prompting a seventeen (17) per cent drop in Facebook’s cut-rate and summons for stricter laws governing tech companies’ usage of private data.

Background Information

Fotis International Law Firm aims to provide our readers with a brief overview of the Facebook Data Breach that happened. A lot of people took a survey in 2014 that looked similar and included not only the user’s personally identifiable information or data but also the data of the user’s Facebook friends with the Company that worked for President Trump’s 2016 campaign. This is where Cambridge Analytica (CA) entered the picture, partnering with Aleksandr Kogan, a UK research academic who was using Facebook for research purposes. Kogan’s survey, which appeared innocuous and included over 100 personality traits with which surveyees could agree or disagree, was sent to 3L Americans.

But there’s a catch: to take the survey, surveyee’s must log in or sign up for Facebook, giving Kogan access to the user’s profile, birth date, and location. Kogan created a psychometric model, which is similar to a personality profile, by combining the survey results with the user’s Facebook data. The data was then combined with voter records and sent to CA by Kogan. CA claimed that the results of this survey, combined with the personal traits of various users and models, were crucial in determining how they profiled a user’s psychoneurosis and other susceptible traits.

In only a few months, two lakh twenty thousand people took part in the survey of Kogan, and data from up to 87 million Facebook user profiles were harvested, accounting for nearly a quarter of all Facebook users in the United States. The goal was to use the data to target users/surveyees with political messaging that would aid Trump’s campaign strategy, but the campaign objected. Even though Kogan’s work was for academic research, he shared the formulated data with CA, which is against Facebook’s policy. In response to the violation, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg stated that it was not a data breach because no passwords were stolen or any systems were infiltrated, but it was a violation of the terms of service. In response to the breach, the CEO of Facebook who is Mark Zuckerberg stated that it was not a data breach because no passwords were stolen or any systems were infiltrated, but rather a breach of contravention between Facebook and its users. The Federal Trade Commission of the US took up the investigation after that.

Facebook Data Breach

CA’s illegitimate procurement of personally identifiable data was first revealed in December 2015 by Harry Davies, a Guardian journalist. CA was working for US Senator Ted Cruz, according to Harry, and had obtained data from millions of Facebook accounts without their permission. Facebook declined to comment on the story other than to say that it was looking into it. The scandal finally blew up in March 2018 when a conspirator, Christopher Wylie, an ex-CA employee, was exposed. Christopher was an unidentified source for Cadwalladr’s article “The Great British Brexit Robbery” in 2017. This report was well-received, but it was met with scepticism in some quarters, prompting sceptical responses in publications such as The New York Times. In March 2018, the news organizations released their stories concurrently, causing a massive public outcry that resulted in more than $100 billion being deducted from Facebook’s retail funding in a matter of days. Senators from the US and the UK have demanded answers from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Following the scandal, Mark Zuckerberg agreed to testify in front of the US Congress.

Summary of the Case

CA’s parent company, Strategic Communication Laboratories Group, was a private British behavioural and strategic research communication corporation. In the US and other countries, SCL sparked public outrage by obtaining data through data mining and data analysis on its users with the help of a university researcher named Aleksandr Kogan, who was tasked with developing an app called “This is your digital life” and along with that, he was told to create a survey on the behavioural patterns of users that he had obtained from Facebook’s social media users, to use the data for electoral/political purposes without the approval of Facebook or the users of Facebook, since the data was detailed enough to create a profile that implied which type of advertisement would be most effective in influencing them. Based on the findings, the data would be carefully targeted to key audience associations to change behaviour in line with SCL’s client’s objective, resulting in a breach of trust between Facebook and its users.

Legal Implications

As a result, the Facebook CEO was questioned, and the stock price dropped by seventeen (17) per cent. He was also requested to enforce strict regulations on the protection of users’ data. Users were afterwards told that the access they had provided for various applications had been withdrawn and reviewed in the settings, as well as there being audit trials on breach investigation. Meanwhile, Facebook has vowed to create an app that would require users to delete all of their Facebook web search data. CA has been the subject of multiple baseless allegations in past years, and despite the firm’s efforts to improve the record, it has been chastised for actions that are not only legal but also generally acknowledged as a routine component of internet promotion in both the federal and industrial sectors.

Julian Malins, a third-party auditor, was appointed by CA to look into the allegations of wrongdoing. According to the firm, the inquiry determined that the charges were not supported by the facts. Despite CA’s constant belief that its employees have acted ethically and lawfully, a belief that is now completely supported by Mr Malin’s declaration, the Company’s clients and suppliers have been driven away implicitly as a result of the media coverage. As a result, in May 2018, it was decided that continuing to manage the firm was no longer practicable, leaving CA with no practical alternative for bringing the firm into government.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which had come into effect in May 2018, establishes logical data security laws across Europe. It applies to all companies that prepare private data about EU citizens, regardless of where they are situated. Processing is a comprehensive term that refers to everything linked to private data, such as how a company handles and uses data, such as settling, saving, using, and destroying it.

While many of the GDPR’s requirements are based on EU data protection regulations, the GDPR has a greater reach, more precise standards, and ample penalties. For example, it necessitates a higher level of consent for the use of certain types of data and enhances people’s rights to request and shifting their data. Failure to comply with the GDPR can result in significant penalties, including fines of up to 4% of worldwide annual income for multiple violations or infringements. In terms of policy changes, data may only be accessed by others, including developers. If permissions are granted, data settings are stricter, and a research tool is used to scrutinize the search.

Regardless matter how many changes or updates are made to specific applications, the user of that platform should be aware of the types of personal data and apps to which rights should be granted. In addition, maintaining a check, such as evaluating account activity, revoking access to illegal applications, and monitoring its settings at regular intervals, is critical to keeping their data safe and being aware of the repercussions of a breach. The case of CA is the precedent. Countries should create a legal framework that will severely restrict the operations of firms like CA and prevent the globally uncontrolled exploitation of personal data on social media. No one can guarantee that a government would resist the temptation to utilize technology for its ends. It’s quite probable that it’s going on right now.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far

Revelations that digital consultants to the Trump campaign misused the data of millions of Facebook users set off a furor on both sides of the Atlantic. This is how The Times covered it.

By Nicholas Confessore

In March, The New York Times, working with The Observer of London and The Guardian, obtained a cache of documents from inside Cambridge Analytica, the data firm principally owned by the right-wing donor Robert Mercer . The documents proved that the firm , where the former Trump aide Stephen K. Bannon was a board member, used data improperly obtained from Facebook to build voter profiles. The news put Cambridge under investigation and thrust Facebook into its biggest crisis ever. Here’s a guide to our coverage.

Harvesting data and testing election law

The Times reported that in 2014 contractors and employees of Cambridge Analytica, eager to sell psychological profiles of American voters to political campaigns, acquired the private Facebook data of tens of millions of users — the largest known leak in Facebook history.

There was more. Our article first showed how Cambridge received warnings from its own lawyer, Laurence Levy, as it employed European and Canadian citizens on campaigns, potentially violating American election law. The Times also found that tranches of raw data still existed beyond Facebook’s control.

Read how researchers may have used your Facebook “likes” to predict your political views.

What was the Russia link?

In a companion piece , The Times reported that people at Cambridge Analytica and its British affiliate, the SCL Group, were in contact with executives from Lukoil, the Kremlin-linked oil giant, as Cambridge built its Facebook-derived profiles. Lukoil was interested in the ways data was used to target American voters, according to two former company insiders. SCL and Lukoil denied that the talks were political in nature and said the oil giant never became a client.

Anger on both sides of the Atlantic

The articles drew an instant response in Washington, where lawmakers demanded that Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, testify before Congress . Democrats looking into Russian interference in the 2016 election — already interested in Cambridge’s role in providing analytics to the Trump campaign — said they would seek an investigation into the leak. They were echoed by lawmakers in Britain investigating Cambridge Analytica’s role in disinformation and the country’s referendum to leave the European Union.

Bribes, entrapment and a suspension

The Times reported that Cambridge suspended its chief executive, Alexander Nix, after a British television channel released an undercover video in which he suggested that the company had used seduction and bribery to entrap politicians and influence foreign elections. In Washington, the Federal Trade Commission moved to investigate whether Facebook had violated an early agreement to safeguard user data.

Facebook faces a reckoning

The Times reported on a growing number of Facebook users, including the singer Cher, deleting their accounts — and broke news of the departure of Facebook’s top security official , who had clashed with other executives on how to handling discontent over the platform’s role in spreading disinformation. The hashtag #DeleteFacebook began trending on Twitter.

After remaining silent for days — spurring another social media hashtag, #WheresZuck? — Mr. Zuckerberg spoke with The Times about steps Facebook was taking to address users’ anger.

Our columnist Brian X. Chen explains how to protect your Facebook data .

New Trump adviser, old Cambridge connection

As Facebook reeled, The Times delved into the relationship between Cambridge Analytica and John Bolton , the conservative hawk named national security adviser by President Trump . The Times broke the news that in 2014, Cambridge provided Mr. Bolton’s “super PAC” with early versions of its Facebook-derived profiles — the technology’s first large-scale use in an American election.

What about 2016? We examined the skepticism and evidence around the role Cambridge claimed it played in Mr. Trump’s win.

Cambridge Analytica helped develop ads for candidates supported by John Bolton's “super PAC.”

Another look at ‘Brexit’

The Times and The Observer reported allegations that the 2016 “Brexit” campaign used a Cambridge Analytica contractor to help skirt election spending limits. The story implicated two senior advisers to Prime Minister Theresa May. Testifying to Parliament a few days later , a former Cambridge employee, Christopher Wylie, contended that the company helped swing the results in favor of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union.

The Silicon Valley spy contractor

In another report, The Times showed how an employee at Palantir Technologies — an intelligence contractor founded by the Trump backer and tech investor Peter Thiel — helped Cambridge harvest Facebook data . The article reported that Palantir and Cambridge executives briefly considered a formal partnership to work on political campaigns. Though the deal fell through, a Palantir employee continued working with Cambridge to figure out how to obtain data for psychographic profiles. Palantir officials said the employee did so in a strictly personal capacity.

How many were affected?

The Times originally reported that Cambridge harvested data from over 50 million Facebook users. But at the bottom of a company announcement about new privacy features, Facebook’s chief technology officer, Mike Schroepfer, issued a new estimate for the number of users who were affected: as many as 87 million , most of them in the United States.

Facebook is responding to users’ distrust. Read how the company introduced a central privacy page .

‘You are the product’

Amid the crisis, one set of voices remained notably absent: Facebook users whose data was harvested. So The Times found some , and their reactions ranged from anger to resigned annoyance at how tech giants use personal information. As one of the affected Facebook users put it, “You are the product on the internet.”

The Times also reported new details on the app used to collect data for Cambridge Analytica. It was no simple Facebook quiz, as many had assumed. Rather, it was attached to a lengthy psychology questionnaire hosted by Qualtrics, a company that manages online surveys. The first step for those filling out the questionnaire was to grant access to their Facebook profiles. Once they did, an app then harvested their data and that of their friends.

Zuckerberg speaks to lawmakers

Congress vs. mark zuckerberg: the key moments, in a hearing held in response to revelations of data harvesting by cambridge analytica, mark zuckerberg, the facebook chief executive, faced questions from senators on a variety of issues, from privacy to the company’s business model..

“Mr. Zuckerberg, would you be comfortable sharing with us the name of the hotel you stayed in last night?” “Um — no.” “If you’ve messaged anybody this week, would you share with us the names of the people you’ve messaged?” “Senator, no, I would probably not choose to do that publicly here.” “I think that may be what this is all about.” “In 2015, we heard the report that this developer Aleksandr Kogan had sold data to Cambridge Analytica.” “Did you or senior leadership do an inquiry to find out who at Facebook had this information and did they not have a discussion about whether or not the users should be informed back in December of 2015?” “Senator, in retrospect, I think we clearly view it as a mistake that we didn’t inform people. And we did that based on false information that we thought that the case was closed, and that the data had been deleted.” “So there was a decision made on that basis not to inform the users. Is that correct?” “That’s my understanding, yes.” “I assume Facebook’s been served with subpoenas from the special counsel Mueller’s office. Is that correct?” “Yes. Actually, let me clarify that. I actually am not aware of a subpoena. I believe that there may be. But I know we’re working with them.” “Thank you.” “If I buy a Ford and it doesn’t work well and I don’t like it, I can buy a Chevy. If I’m upset with Facebook, what’s the equivalent product that I can go sign up for?” “The average American uses eight different apps —” “O.K.” “— to communicate with their friends and stay in touch with people —” “O.K.” “— ranging from text apps —” “— which is —” — to email.” “Which is the same service you provide.” “Well, we provide a number of different services.” “Is Twitter the same as what you do?” “It overlaps with a portion of what we do.” “You don’t think you have a monopoly?” “It certainly doesn’t feel like that to me.” “O.K.” [audience laughs] “Do you need to look behind shell corporations in order to find out who is really behind the content that’s being posted? And if you may need to look behind a shell corporation, how will you go about doing that? How will you get back to the true, what lawyers would call ‘beneficial owner’ of the site that is putting out the political material?” “So what we’re going to do is require a valid government identity and we’re going to verify the location. So we’re going to do that, so that way someone sitting in Russia, for example, couldn’t say that they’re in America and therefore able to run an election ad.” “But if they were running through a corporation domiciled in Delaware, you wouldn’t know that they were actually a Russian owner.” “Senator, that’s— that’s correct.”

Mr. Zuckerberg made his first appearance before Congress , testifying to Senate and House committees. First up was the Senate, where he faced tough questions about the company’s mishandling of data, and said Facebook was investigating “tens of thousands of apps” to see what information they harvested.

The next day, he faced an even tougher crowd in the House. There, the consensus was that social media technology — and its potential for abuse — had far outpaced Washington, and that Congress may have to step in to close the gap. Even Mr. Zuckerberg seemed to suggest he could be open to some regulation, but neither he nor lawmakers seemed sure about how exactly to regulate the new breed of companies.

A setback for the Mercers

On the same day as the Senate hearing, The Times reported how the Cambridge furor had impacted the Mercers , particularly Mr. Mercer’s daughter Rebekah, who leads the family’s political network. Shortly after the scandal broke, a friend of hers visited Facebook headquarters to plead the case for Cambridge. Though the Mercers were once Mr. Trump’s leading patrons in conservative politics, their standing in the president’s circle has suffered.

Who audits the auditors?

The Times reported on a series of assessments of Facebook’s privacy programs, conducted by the consulting firm PwC on behalf of federal regulators. In the assessments, mandated by a 2011 consent decree, PwC deemed Facebook’s internal controls effective at protecting users’ privacy — even after the social media giant lost control of a huge trove of user data that was improperly obtained by Cambridge Analytica.

Matthew Rosenberg contributed reporting.

Nicholas Confessore is a New York-based political and investigative reporter at The Times and a writer-at-large at The Times Magazine, covering the intersection of wealth, power and influence in Washington and beyond. He joined The Times in 2004. More about Nicholas Confessore

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Lily Hay Newman

What Really Caused Facebook's 500M-User Data Leak?

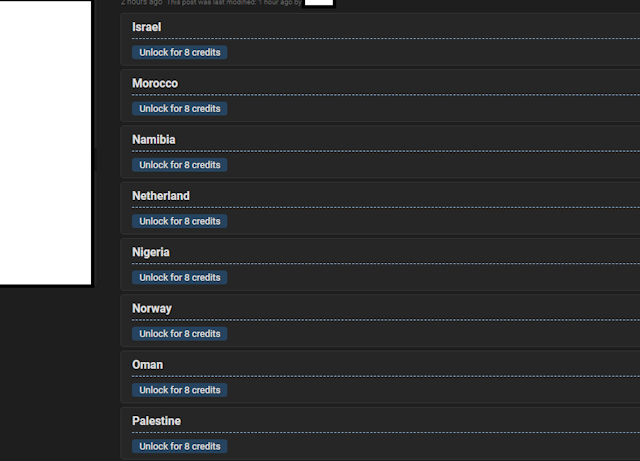

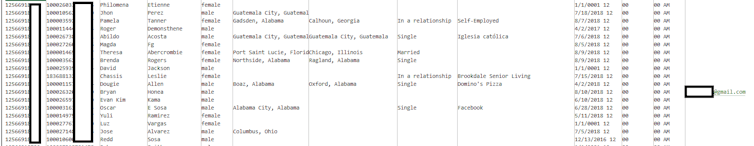

Since Saturday, a massive trove of Facebook data has circulated publicly , splashing information from roughly 533 million Facebook users across the internet. The data includes things like profile names, Facebook ID numbers, email addresses, and phone numbers. It's all the kind of information that may already have been leaked or scraped from some other source, but it's yet another resource that links all that data together—and ties it to each victim—presenting tidy profiles to scammers, phishers, and spammers on a silver platter.

Facebook's initial response was simply that the data was previously reported on in 2019 and that the company patched the underlying vulnerability in August of that year. Old news. But a closer look at where, exactly, this data comes from produces a much murkier picture. In fact, the data, which first appeared on the criminal dark web in 2019, came from a breach that Facebook did not disclose in any significant detail at the time and only fully acknowledged Tuesday evening in a blog post attributed to product management director Mike Clark.

One source of the confusion was that Facebook has had any number of breaches and exposures from which this data could have originated. Was it the 540 million records—including Facebook IDs, comments, likes, and reaction data—exposed by a third party and disclosed by the security firm UpGuard in April 2019? Or was it the 419 million Facebook user records, including hundreds of millions of phone numbers, names, and Facebook IDs, scraped from the social network by bad actors before a 2018 Facebook policy change, that were exposed publicly and reported by TechCrunch in September 2019? Did it have something to do with the Cambridge Analytica third-party data sharing scandal of 2018? Or was this somehow related to the massive 2018 Facebook data breach that compromised access tokens and virtually all personal data from about 30 million users?

In fact, the answer appears to be none of the above. As Facebook eventually explained in background comments to WIRED and in its Tuesday blog, the recently public trove of 533 million records is an entirely different data set that attackers created by abusing a flaw in a Facebook address book contacts import feature. Facebook says it patched the vulnerability in August 2019, but it's unclear how many times the bug was exploited before then. The information from more than 500 million Facebook users in more than 106 countries contains Facebook IDs, phone numbers, and other information about early Facebook users like Mark Zuckerburg and US secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, as well as the European Union commissioner for data protection, Didier Reynders. Other victims include 61 people who list the "Federal Trade Commission" and 651 people who list "Attorney General" in their details on Facebook.

You can check whether your phone number or email address were exposed in the leak by checking the breach tracking site HaveIBeenPwned . For the service, founder Troy Hunt reconciled and ingested two different versions of the data set that have been floating around.

“When there’s a vacuum of information from the organization that’s implicated, everyone speculates, and there's confusion,” Hunt says.

The closest Facebook came to acknowledging the source of this breach previously was a comment in a fall 2019 news article. That September, Forbes reported on a related vulnerability in Instagram's mechanism to import contacts. The Instagram bug exposed users’ names, phone numbers, Instagram handles, and account ID numbers. At the time, Facebook told the researcher who disclosed the flaw that the Facebook security team was “already aware of the issue due to an internal finding.” A spokesperson told Forbes at the time, “We have changed the contact importer on Instagram to help prevent potential abuse. We are grateful to the researcher who raised this issue." Forbes noted in the September 2019 story that there was no evidence the vulnerability had been exploited, but also no evidence that it had not been.

In its blog post today, Facebook links to a September 2019 article from CNET as evidence that the company publicly acknowledged the 2019 data exposure. But the CNET story refers to findings from a researcher who also contacted WIRED in May 2019 about a trove of Facebook data, including names and phone numbers. The leak the researcher had learned about was the same one TechCrunch reported on in September 2019. And according to the September 2019 CNET story, it is the same one CNET was describing. Facebook told TechCrunch at the time, “This data set is old and appears to have information obtained before we made changes last year [2018] to remove people’s ability to find others using their phone numbers.” Those changes were aimed at reducing the risk that Facebook's search and account-recovery tools could be exploited for mass scraping.

Andy Greenberg

Steven Levy

Matt Reynolds

Jeremy White

Data sets circulating in criminal forums are often mashed together, adapted, recombined, and sold off in different chunks, which can account for variations in their exact size and scope. But based on Facebook's comment in 2019 that the data TechCrunch reported on was from mid-2018 or earlier, it seems not to be the currently circulating data set. The two troves also have different attributes and numbers of users impacted in each region. Facebook declined to comment for the September 2019 CNET story.

If all of this feels exhausting to sort through, it's because Facebook went days without giving a substantive answer and has left open some degree of confusion.

“At what point did Facebook say, ‘We had a bug in our system, and we added a fix, and therefore users might be affected’?" says former Federal Trade Commission chief technologist Ashkan Soltani. “I don't remember ever seeing Facebook say that. And they’re kind of stuck now, because they apparently didn’t do any disclosure or notification."

Before its blog acknowledging the breach, Facebook pointed to the Forbes story as evidence that it publicly acknowledged the 2019 Facebook contact importer breach. But the Forbes story is about a similar yet seemingly unrelated finding in Instagram versus main Facebook, which is where the 533-million-user leak comes from. And Facebook admits that it did not notify users that their data had been compromised individually or through an official company security bulletin.

The Irish Data Protection Commission said in a statement on Tuesday that it “received no proactive communication from Facebook" regarding the breach.

“Previous data sets were published in 2019 and 2018 relating to a large-scale scraping of the Facebook website, which at the time Facebook advised occurred between June 2017 and April 2018 when Facebook closed off a vulnerability in its phone look-up functionality," according to the timeline the commission put together. "Because the scraping took place prior to GDPR, Facebook chose not to notify this as a personal data breach under GDPR. The newly published data set seems to comprise the original 2018 (pre GDPR) data set and combined with additional records, which may be from a later period.”

By Lily Hay Newman

Facebook says it did not notify users about the 2019 contact importer exploitation precisely because there are so many troves of semipublic user data—taken from Facebook itself and other companies—out in the world. Additionally, attackers needed to supply phone numbers and manipulate the feature to spit out the corresponding name and other data associated with it for the exploit to work, which Facebook argues means that it did not expose the phone numbers itself. “It is important to understand that malicious actors obtained this data not through hacking our systems but by scraping it from our platform prior to September 2019,” Clark wrote Tuesday. The company aims to draw a distinction between exploiting a weakness in a legitimate feature for mass scraping and finding a flaw in its systems to grab data from its backend. Still, the former is a vulnerability exploitation.

But for those affected, this is a distinction without a difference. Attackers could simply run through every possible international phone number and collect data on hits. The Facebook bug provided bad actors with the missing connection between phone numbers and public information like names.

Phone numbers used to be public in phone books and often still are, but as they've evolved to be ubiquitous identifiers , linking you to different parts of your digital life, they've taken on new significance and potential value to attackers. They even play a role in sensitive authentication, by being the path through which you might receive two-factor authentication codes over SMS or a phone call in which you provide information to confirm your identity. The idea that phone numbers are now critical to your digital security is not at all new .

“It's a fallacy to think that a breach isn't serious just because it doesn't have passwords in it or other maximally sensitive data,” says Zack Allen, director of threat intelligence at the security firm ZeroFox. “It's also a fallacy to say that a situation isn't that bad just because it's old data. And furthermore, phone numbers scare the crap out of me as a form of authentication, which unfortunately is how they're often used these days.”

For its part, Facebook has repeatedly mishandled user phone numbers. They used to be easily collectible on a large scale through the company's Graph Search API tool. At the time, the company didn't view that as a security vulnerability, because Graph Search surfaced only phone numbers and other data that users set to be public on their profiles. Over the years, though, Facebook started to recognize that it was a problem to make such data so easy to scrape, even if individual users chose to make their data public. In aggregate, the information could still enable scamming and phishing on a scale that individuals presumably did not intend.

In 2018, Facebook acknowledged that it targeted ads based on users' two-factor authentication phone number. That same year, the company also disabled a feature that allowed users to search for other people on Facebook using their phone number or email address—a mechanism that was again being abused by scrapers. According to Facebook, this is the tool cybercriminals used to collect the data TechCrunch reported on in 2019.

Yet somehow, in spite of these and other gestures toward locking user phone numbers down, Facebook still did not fully disclose the 2019 data breach. The contact import feature is somewhat beleaguered, and the company also fixed vulnerabilities in it in 2013 and 2017 .

Meanwhile, Facebook reached a landmark settlement with the FTC in July 2019 over what can only be described as a massive number of deeply concerning data privacy failures. In exchange for paying a $5 billion fine and agreeing to certain terms, like discontinuing its aforementioned alternate uses of security-authentication related phone numbers, Facebook was indemnified for all activity before June 12, 2019.

Whether any of the contact import exploitation occurred after that date—and therefore should have been reported to the FTC—remains an open question. The one thing that's certain in all this is that more than 500 million Facebook users are less safe online than they otherwise would be—and potentially vulnerable to a new wave of scams and phishing that Facebook could have alerted them to nearly two years ago.

- 📩 The latest on tech, science, and more: Get our newsletters !

- A genetic curse, a scared mom, and the quest to “fix” embryos

- Larry Brilliant has a plan to speed up the pandemic’s end

- Facebook's “Red Team X” hunts bugs beyond its walls

- How to choose the right laptop: A step-by-step guide

- Why retro-looking games get so much love

- 👁️ Explore AI like never before with our new database

- 🎮 WIRED Games: Get the latest tips, reviews, and more

- 🎧 Things not sounding right? Check out our favorite wireless headphones , soundbars , and Bluetooth speakers

Reece Rogers

Matt Burgess

Dhruv Mehrotra

Vittoria Elliott

Morgan Meaker

Amanda Hoover

Facebook data breach: what happened and why it’s hard to know if your data was leaked

Associate Dean (Computing and Security), Edith Cowan University

Disclosure statement

Paul Haskell-Dowland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Edith Cowan University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Over the long weekend reports emerged of an alleged data breach, impacting half a billion Facebook users from 106 countries.

And while this figure is staggering, there’s more to the story than 533 million sets of data. This breach once again highlights how many of the systems we use aren’t designed to adequately protect our information from cyber criminals.

Nor is it always straightforward to figure out whether your data have been compromised in a breach or not.

What happened?

More than 500 million Facebook users’ details were published online on an underground website used by cyber criminals.

It quickly became clear this was not a new data breach, but an older one which had come back to haunt Facebook and the millions of users whose data are now available to purchase online.

The data breach is believed to relate to a vulnerability which Facebook reportedly fixed in August of 2019 . While the exact source of the data can’t be verified, it was likely acquired through the misuse of legitimate functions in the Facebook systems .

Such misuses can occur when a seemingly innocent feature of a website is used for an unexpected purpose by attackers, as was the case with a PayID attack in 2019.

Read more: PayID data breaches show Australia's banks need to be more vigilant to hacking

In the case of Facebook, criminals can mine Facebook’s systems for users’ personal information by using techniques which automate the process of harvesting data.

This may sound familiar. In 2018 Facebook was reeling from the Cambridge Analytica scandal . This too was not a hacking incident , but a misuse of a perfectly legitimate function of the Facebook platform.

While the data were initially obtained legitimately — as least, as far as Facebook’s rules were concerned — it was then passed on to a third party without the appropriate consent from users.

Read more: We need to talk about the data we give freely of ourselves online and why it's useful

Were you targeted?

There’s no easy way to determine if your details were breached in the recent leak. If the website concerned is acting in your best interest, you should at least receive a notification. But this isn’t guaranteed .

Even a tech-savvy user would be limited to hunting for the leaked data themselves on underground websites.

The data being sold online contain plenty of key information. According to haveibeenpwned.com, most of the records include names and genders, with many also including dates of birth, location, relationship status and employer.

Although, it has been reported only a small proportion of the stolen data contained a valid email address (about 2.5 million records).

This is important since a user’s data are less valuable without the corresponding email address. It’s the combination of date of birth, name, phone number and email which provides a useful starting point for identity theft and exploitation .

If you’re not sure why these details would be valuable to a criminal, think about how you confirm your identity over the phone with your bank, or how you last reset a password on a website.

Haveibeenpwned.com creator and web security expert Troy Hunt has said a secondary use for the data could be to enhance phishing and SMS-based spam attacks.

How to protect yourself

Given the nature of the leak, there is very little Facebook users could have done proactively to protect themselves from this breach. As the attack targeted Facebook’s systems, the responsibility for securing the data lies entirely with Facebook.

On an individual level, while you can opt to withdraw from the platform, for many this isn’t a simple option. That said, there are certain changes you can make to your social media behaviours to help reduce your risk from data breaches.

1) Ask yourself if you need to share all your information with Facebook

There are some bits of information we inevitably have to forfeit in exchange for using Facebook, including mobile numbers for new accounts (as a security measure, ironically). But there are plenty of details you can withhold to retain a modicum of control over your data.

2) Think about what you share

Apart from the leak being reported, there are plenty of other ways to harvest user data from Facebook. If you use a fake birth date on your account, you should also avoid posting birthday party photos on the real day. Even our seemingly innocent photos can reveal sensitive information.

3) Avoid using Facebook to sign in to other websites

Although the “sign-in with Facebook” feature is potentially time-saving (and reduces the number of accounts you have to maintain), it also increases potential risk to you — especially if the site you’re signing into isn’t a trusted one. If your Facebook account is compromised, the attacker will have automatic access to all the linked websites.

4) Use unique passwords

Always use a different password for each online account, even if it is a pain. Installing a password manager will help with this (and this is how I have more than 400 different passwords). While it won’t stop your data from ever being stolen, if your password for a site is leaked it will only work for that one site.

If you really want a scare, you can always download a copy of all the data Facebook has on you . This is useful if you’re considering leaving the platform and want a copy of your data before closing your account.

Read more: New evidence shows half of Australians have ditched social media at some point, but millennials lag behind

- Social media

- Online security

- Cybersecurity

- Data breaches

- Online data

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Partner, Senior Talent Acquisition

Deputy Editor - Technology

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

The Ethical Implications of the 2018 Facebook-Cambridge Analytica Data Scandal

Access full-text files, journal title, journal issn, volume title, description, lcsh subject headings, collections.

Facebook and Data Privacy in the Age of Cambridge Analytica

April 30, 2018

Iga Kozlowska

In recent weeks, the world has been intently following the Cambridge Analytica revelations: millions of Facebook users’ personal data was used, without their knowledge, to aide the political campaigns of conservative candidates in the 2016 election, including Donald Trump. While not exactly a data breach, from the public response to this incident, it is clear that the vast majority of Facebook users did not knowingly consent to have their personal information used in this way.

What is certain is that Facebook, the world’s largest social network platform, serving over two billion customers globally, is facing public scrutiny like never before. With data breaches, ransomware attacks, and identity theft a regular occurrence in this digitally driven economy, this event is different. For the first time, we see the mishandling of social data for political purposes on a mass scale. [1] It remains to be seen whether this will be a watershed moment for rethinking how we use personal data in the modern age. It is also unclear whether this experience will change companies’ and consumers’ privacy practices forever. For now, however, Facebook users and investors, American and foreign governments, and numerous regulatory bodies are paying attention.

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook

In 2013, University of Cambridge psychology professor Dr. Aleksandr Kogan created an application called “thisisyourdigitallife.” This app, offered on Facebook, provided users with a personality quiz. After a Facebook user downloads the app, it would start collecting that person’s personal information such as profile information and Facebook activity (e.g., what content was “liked”). Around 300,000 people downloaded the app. But the data collection didn’t stop there. Because the app also collected information about those users’ friends, who had their privacy settings set to allow it, the app collected data from about 87 million people. [2]

Next, Dr. Kogan passed this data on to Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL), which owns Cambridge Analytica (CA), a political consulting firm that uses data to determine voter personality traits and behavior. [3] It then uses this data to help conservative campaigns target online advertisements and messaging. It is precisely at this point of data transfer from Dr. Kogan to other third parties like CA that Dr. Kogan violated Facebook’s terms of service, which prohibit the transfer or sale of data “to any ad network, data broker or other advertising or monetization-related service.” [4]

When Facebook learned about this in 2015, it removed Kogan’s app and demanded certifications from Kogan, and CA that they had deleted the data. Kogan and CA all certified to Facebook that they destroyed the data. However, copies of the data remained beyond Facebook’s control. While Alexander Nix, the CEO of CA, has told lawmakers that the company does not have Facebook data, “a former employee said that he had recently seen hundreds of gigabytes on CA servers, and that the files were not encrypted” reports the New York Times. [5]

In 2015, Facebook did not make any public statements regarding the incident, nor did it inform those users whose data was shared with CA. [6] Neither did Facebook report the incident to Federal Trade Commission, the US agency that oversees privacy-related issues. As Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook CEO, said during his two-day Congressional hearing on April 9 and April 10, 2018, once they received CA’s attestation that the data has been deleted and is no longer being used, Facebook considered the “case closed.” [7]

With the breaking of the story on March 17, 2018 in The Guardian [8] and the New York Times [9] , Facebook was made aware that the data in fact have not been purged to this day. The fallout from this incident has been unprecedented. Facebook is facing numerous lawsuits, US, UK, and EU governmental inquiries, a #DeleteFacebook boycott campaign, and a sharp drop in share price that’s erased nearly $50 billion of the company’s market capitalization in a mere three days of the news breaking [10] .

This is not the first time, however, that Facebook, has faced issues related to its data collection and processing. [11] And, it is not the first time that it has faced regulatory scrutiny. For example, in 2011, the FTC settled a 20-year consent decree with Facebook, having found that Facebook routinely deceived its users by sharing personal data with third parties that users thought was private. [12] It is only now that Facebook’s irresponsible behavior is receiving widespread public scrutiny. Whereas warnings from privacy and security professionals to date have been large falling on deaf ears; why has this event capturing the attention of consumers, companies, and governments the world over?

We have seen international data breach cases at this scale before. Indeed, data breaches, identify theft, ransomware, and other cybersecurity attacks have become ubiquitous in a digital global economy that runs on data. [13] In the last five years, we have witnessed the 2013 Snowden revelations of mass global government surveillance and the 2014 North Korean attack on Sony, a US corporation. [14] The average consumer has been hit hard as well. The 2013 Target data breach resulted in 40 million compromised payment cards. [15] The 2016 Yahoo attack compromised 500 million accounts [16] and the 2017 Equifax hack compromised 143 million. [17] It doesn’t help that, at the same time as the Cambridge Analytica incident, Facebook discovered a vulnerability in its search and account recovery features that may have allowed bad actors to harvest the public profile information of most of its two billion users . [18] It seems that the public feels that enough is enough.

Beyond the scale of the event, the Cambridge Analytica incident involves arguably the most serious misuse and mishandling of consumer data we’ve yet seen. The purpose for which the data was illegally harvested is new and it hits a nerve with an American society that is already politically divided and where political emotions run high. Funded by Robert Mercer, a prominent Republican donor, and Stephen Bannon, Trump’s former political adviser, CA was using the data for explicit political purposes – to help conservative campaigns in the 2016 election, including Donald Trump’s campaign. [19] Neither the 3000,000 Facebook users who downloaded the app nor their 87 million friends anticipated that their personal data could be used for these political purposes. It’s one thing if customer data is used to serve bothersome ads, or a hacker steals credit card information for economic gain, but it’s another if the world’s largest social network was taken advantage of to help elect the president of the United States. So what exactly is Facebook’s accountability in all this?

From Data Breach to Breach of Trust

Was this incident a data breach? Facebook first responded on March 17, 2018 in a Facebook post by Paul Grewal, VP & Deputy General Counsel, who wrote that, “The claim that this is a data breach is completely false. Aleksandr Kogan requested and gained access to information from users who chose to sign up to his app, and everyone involved gave their consent. People knowingly provided their information, no systems were infiltrated, and no passwords or sensitive pieces of information were stolen or hacked.” [20] That same day, Alex Stamos, Facebook’s Chief Security Officer, tweeted (and later deleted the tweet) that, “Kogan did not break into any systems, bypass any technical controls, our use a flaw in our software to gather more data than allowed. He did, however, misuse that data after he gathered it, but that does not retroactively make it a ‘breach.'” [21]

This is true. According to the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission – two bodies that govern global security best practices – the definition of data breach is as follows: “a compromise of security that leads to the accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorized disclosure of, or access to protected data transmitted, stored or otherwise processed.” [22] Because Facebook’s systems were not penetrated and the data was mishandled by a third-party in explicit violation of Facebook’s terms of service, the incident does not qualify as a data breach as understood by the global cybersecurity community. But what about everyone else?

Facebook quickly understood, however, that to millions of users whose data was mishandled, this incident felt like a data breach. [23] Despite the fact that technically all 87 million Facebook users consented to Kogan’s app collecting their personal data by not changing their privacy settings accordingly, the public outcry reveals that they do not feel that they authorized the app to access their data, let alone share it with a third party like CA. Facebook’s defense that it does provide users with controls to determine what types of data they want to share with which apps and what can be shared with apps that their friends use felt empty to customers who are largely unaware of these controls because Facebook does not make it easy to access them. Moreover, Facebook’s privacy settings are by default not set for privacy. This is, at least in part, because, as was made clear in the Congressional hearings this month, Facebook’s business model relies on app developers’ access to their users’ data for targeted advertising, which makes up over 90% of Facebook’s revenue. In other words, Facebook’s business model conflicts with privacy-friendly policies. [24]

Quickly recognizing this, Facebook pivoted, took some responsibility, and rather than argue the fine points of data breach definitions, apologized for what was experienced by customers as a breach of trust. Only five days after the story broke, Zuckerberg wrote in a Facebook post, “This was a breach of trust between Kogan, Cambridge Analytica and Facebook. But it was also a breach of trust between Facebook and the people who share their data with us and expect us to protect it. We need to fix that.” [25] That week Facebook took out full-page ads in nine major US and international newspapers with the message: “This was a breach of trust and I’m sorry we didn’t do more at the time. I promise to do better for you.” [26] Recognizing the complex digital ecosystem Zuckerberg said in his opening remarks at the Congressional hearing that, “We didn’t take a broad enough view of what our responsibility is. That was a huge mistake, and it was my mistake.” [27]

This “apology tour,” as Senator Blumenthal dubbed it, will be meaningless without concrete policy changes. [28] Facebook has already instituted some changes. For example, they have tightened some of the APIs that allow apps to harvest data like information about which events a user hosts or attends, the groups to which they belong, and page posts and comments. Apps that have not been used in more than three months will no longer be able to collect user data. [29] In addition, Facebook will now be authorizing those who want to place political or issues ads on Facebook’s platform by validating their identity and location. [30] These ads will be marked as ads and will show who has paid for them. In addition, in June, Facebook plans to launch a public and searchable political ads archive. [31] Finally, Facebook has started a partnership with scholars who will work out a new model for academics to gain access to social media data for research purposes. The plan is to “form a commission which, as a trusted third party, receives access to all relevant firm information and systems, and then recruits independent academics to do research in specific areas following standard peer review protocols organized and funded by nonprofit foundations.” [32] This should not only allow scholars greater access to social data but also safeguard against its misuse, as in the case of Dr. Kogan, by clearly distinguishing between data use for scholarly research and data use for advertising and other secondary purposes.

It remains to be seen just how extensive and impactful Facebook’s policy changes will be. Zuckerberg’s performance at the Congressional hearings was reported positively by the media and Facebook’s stock price regained much of the value it lost since the Cambridge Analytica story broke. However, this is in part because the Senators did not ask specific and pointed questions on what compliance policies Facebook will actually implement. [33] For example, the conversation around the balance between short privacy notices that are reader-friendly and longer and more comprehensive notices written in “legalese” resulted in Zuckerberg signaling that he knows that this debate among privacy professionals exists but did not lead to a commitment by Facebook to make their privacy policies more transparent. [34]

When Zuckerberg did mention specific policy changes, not all of them were new changes responding to this incident. For example, Zuckerberg announced Facebook’s application of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to all Facebook customers, not just Europeans, as a heroic move of self-regulation. [35] However, it should not have taken Facebook this long to announce this position. Limiting the GDPR to EU citizens only, is not only shortsighted as the GDPR becomes de facto global privacy standard, but also unfair to non-EU citizens who would enjoy less privacy protections. In other words, while the Congressional hearing and Facebook’s initial policy changes are a good start, this should only be the beginning of Facebook’s journey toward improved transparency and data protection.

Lessons Learned

What are the lessons learned from the Cambridge Analytica incident for consumers, for companies, and for governments?

Consumers must recognize that their data has value. Consumers should educate themselves on how companies, especially ones that offer free service like Facebook and Google, use their personal data to drive their businesses. Consumers should read privacy notices and take advantage of the in-product user controls that most tech companies offer. Consumers should take advantage of their rights to request that a company let them view, edit, and delete their personal data because after all, consumers own their data, not companies. When companies engage in fraudulent or deceitful data handling practices, consumers should file complaints with the FTC or other appropriate regulatory bodies. Finally, consumers should advocate for more transparency and controls from companies and demand that their elected officials do more to protect privacy.

Companies that electronically process personal data – which is now practically every company in the world – must learn to better balance privacy risks with privacy controls. The riskier the data use, the more user controls are required. The more sensitive the data, the more protections should be put in place. Controls can include explicit consent, reader-friendly and prominent privacy notices, and privacy-friendly default settings. Company leaders should do more than just follow the letter of the law by putting themselves in their customers’ shoes. How do customers expect their data to be used when they hand it over? Is consent given? And is it truly freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous? Moreover, as Facebook learned the hard way, there will always be bad actors. When sharing data with third parties, companies would do well to go the extra mile and ensure that those companies are meeting the company’s privacy requirements by investing in independent audits. When receiving data from third parties, companies should confirm that that data was collected in compliant manner, not by taking their vendors’ word for it, but again, by conducting period audits.

And finally, governments, in this digitally connected global marketplace, must reform outdated legislation so that it addresses the modern complexities of international data usage and transfers. The European Union, for example, is setting a global example, through the General Data Protection Regulation that comes into effect May 25, 2018. Seven years in the making, this is a comprehensive piece of legislation that (1) expands data subjects’ rights (2) enforces 72-hour data breach notifications (3) expands accountability measures and (4) improves enforcement capabilities through levying fines of up to 4% of global revenue. Although applicable only to European residents and citizens, most multi-national tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft are implementing these standards for all of their customers. However, it is high-time, that the US Congress find the political will to pass similar privacy protections for US consumers so that everyone can take advantage of the opportunities that come with the 21 st century digital economy.

[1] For an account of Facebook’s role in undermining democracy see: Vaidhyanathan, Siva. 2018. Antisocial Media : How Facebook Disconnects Us And Undermines Democracy . Oxford University Press. See also Heilbing, Dirk et al . 2017. “Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence?” Scientific American . https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-democracy-survive-big-data-and-artificial-intelligence/ Accessed 4/22/2018.

[2] Kang, Cecilia and Sheera Frenkel. “Facebook Says Cambridge Analytica Harvested Data of Up to 87 Million Users.” The New York Times . April 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/technology/mark-zuckerberg-testify-congress.html Accessed 4/26/18.

[3] Rosenberg, Matthew et al . “How Trump Consultants Exploited the Facebook Data of Millions.” The New York Times . March 17, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/17/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-trump-campaign.html Accessed 4/26/18.

[4] Granville, Kevin. “Facebook and Cambridge Analytica: What You Need to Know as Fallout Widens.” The New York Times . March 19, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/19/technology/facebook-cambridge-analytica-explained.html Accessed 4/15/18.

[5] Rosenberg, 2018.

[6] Rosenberg, 2018.

[7] “Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg Hearing on Data Privacy and Protection.” C-SPAN. April 10, 2018. https://www.c-span.org/video/?443543-1/facebook-ceo-mark-zuckerberg-testifies-data-protection%20Accessed%204/15/18 Accessed 4/26/18.

[8] Cadwalladr, Carole and Emma Graham-Harrison. “Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach.” The Guardian . March 17, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election Accessed 4/26/18.

[9] Rosenberg, 2018.

[10] Mola, Rani. “Facebook has lost nearly $50 billion in market cap since the data scandal.” Recode. March 20, 2018. https://www.recode.net/2018/3/20/17144130/facebook-stock-wall-street-billion-market-cap Accessed 4/26/18

[11] For one of the earliest analyses of Facebook’s privacy policies see Jones, Harvey and Jose Hiram Soltren. 2005. Facebook: Threats to Privacy . http://groups.csail.mit.edu/mac/classes/6.805/student-papers/fall05-papers/facebook.pdf Accessed 4/22/18. See also Fuchs, Christian. 2014. “Facebook: A Surveillance Threat to Privacy?” in Social Media: A Critical Introduction . London: Sage.

[12] “FTC Approves Final Settlement With Facebook.” Federal Trade Commission. August, 10, 2012. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2012/08/ftc-approves-final-settlement-facebook Accessed 4/15/18.

[13] For more on security and privacy see Schneier, Bruce. 2016. Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World . New York. W. W. Norton & Company.

[14] “The Interview: A guide to the cyber attack on Hollywood.” BBC. December 29, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-30512032 Accessed 4/27/18.

[15] “Target cyberattack by overseas hackers may have compromised up to 40 million cards.” The Washington Post . December 20, 2013. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/target-cyberattack-by-overseas-hackers-may-have-compromised-up-to-40-million-cards/2013/12/20/2c2943cc-69b5-11e3-a0b9-249bbb34602c_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.2d3d9c763c06 Accessed 4/27/18.

[16] Fiegerman, Seth. “Yahoo says 500 million accounts stolen.” CNN. September 23, 2016. http://money.cnn.com/2016/09/22/technology/yahoo-data-breach/index.html Accessed 4/27/18.

[17] Siegel Bernard, Tara et al . “Equifax Says Cyberattack May Have Affected 143 Million Users in the U.S.” The New York Times. September 7, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/business/equifax-cyberattack.html Accessed 4/27/18.

[18] Kang and Frenkel, 2018.

[19] Rosenberg, 2018.

[20] Grewal, Paul. “Suspending Cambridge Analytica and SCL Group from Facebook.” March 16, 2018. Facebook Newsroom. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/03/suspending-cambridge-analytica/ Accessed 4/15/18.

[21] Wagner, Kurt. “How Did Facebook Let Cambridge Analytica Get 50M Users’ Data?” Newsfactor. March 21, 2018. https://newsfactor.com/story.xhtml?story_id=113000078MBA Accessed 4/15/18.

[22] ISO/IEC 27040: 2015. International Organization for Standardization. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:27040:ed-1:v1:en Accessed 4/12/18.

[23] On the ethics of social media data collection see Richterich, Annika. 2018. The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies (Critical Digital and Social Media Studies Series). University of Westminster Press.

[24] “Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg Hearing on Data Privacy and Protection.” C-SPAN. April 10, 2018. https://www.c-span.org/video/?443543-1/facebook-ceo-mark-zuckerberg-testifies-data-protection%20Accessed%204/15/18 Accessed 4/26/18.

[25] Zuckerberg, Mark. Facebook Post. March 21, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104712037900071 Accessed 4/15/18.

[26] “Facebook Apologizes for Cambridge Analytica Scandal in Newspaper Ads.” March 25, 2018. TIME . time.com/5214935/facebook-cambridge-analytica-apology-ads/ Accessed 4/15/18.

[27] “Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg Hearing on Data Privacy and Protection.” C-SPAN. April 10, 2018. https://www.c-span.org/video/?443543-1/facebook-ceo-mark-zuckerberg-testifies-data-protection Accessed 4/15/18 .

[28] Dennis, Steven T. and Sarah Frier. “Zuckerberg Defends Facebook’s Value While Senators Question Apology.” Bloomberg. April 10, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-10/facebook-s-zuckerberg-warned-by-senators-of-privacy-nightmare Accessed 4/27/18 .

[29] Schroepfer, Mike. “An Update on Our Plans to Restrict Data Access on Facebook.” Facebook Newsroom. April 4, 2018. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/04/restricting-data-access/ Accessed 4/22/2018.

[30] For a broader discussion of social media and political advertising see Napoli, Philip M. and Caplan, Robyn. 2016. “When Media Companies Insist They’re Not Media Companies and Why It Matters for Communications Policy” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2750148 Accessed 4/22/18.

[31] Goldman, Rob and Alex Himel. “Making Ads and Pages More Transparent.” Facebook Newsroom. April 6, 2018. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2018/04/transparent-ads-and-pages/ Accessed 4/22/2018.

[32] King, Gary and Nathaniel Persily. Working Paper. “A New Model for Industry-Academic Partnerships.” April 9, 2018. https://gking.harvard.edu/partnerships Accessed 4/22/2018.

[33] Member of the House of Representatives took a more aggressive line of questioning with Mark Zuckerberg. For example, Representative Joe Kennedy III poked holes in Facebook’s persistent claim that Facebook users “own” their data by pointing to the massive amount of metadata that Facebook generates (beyond what the user directly generates) and then sells to advertisers. See Madrigal, Alexis C. “The Most Important Exchange of the Zuckerberg Hearing.” The Atlantic . April 11, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/04/the-most-important-exchange-of-the-zuckerberg-hearing/557795/ Accessed 4/27/18.

[34] For the evolution of Facebook’s privacy policy see Shore, Jennifer and Jill Steinman. 2015. “Did You Really Agree to That? The Evolution of Facebook’s Privacy Policy” Technology Science. https://techscience.org/a/2015081102/ Accessed 4/22/18. For a broader conversation around privacy and human behavior see Acquisti, Alessandro. 2015. “Privacy and Human Behavior in the Age of Information” Science . Vol. 347. Pp. 509-514.

[35] For more on European privacy law see Voss, W. Gregory. 2017. “European Union Data Privacy Law Reform: General Data Protection Regulation, Privacy Shield, and the Right to Delisting” Business Lawyer , Vol. 72. Pp. 221-233.

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

About the Author

Dr. Iga Kozlowska is a sociologist and a privacy professional currently working in the technology industry. Iga's expertise in international technology issues is grounded in the unique perspective of a scholar and practitioner. Fascinated by the global digital economy and information governance, Iga is also interested in cybersecurity and is an Associate of the International Information System Security Certification Consortium, the world's leading cybersecurity and IT security professional organization. Iga completed her PhD in sociology at Northwestern University in 2017. Her dissertation research focused on the transnational diffusion of historical memories as it has impacted European integration since 2000. Iga received the US Fulbright Award (Poland 2015-2016) in recognition of the contributions of her research to the burgeoning field of transnationalism studies and to policymakers interested in fostering international cooperation and mutual understanding. Her prior research at the intersections of public policy and nationalism has been published in Nations and Nationalism.

- Center for Global Studies

- Cybersecurity

- Disinformation

- International Policy Institute

- Social media

- North America

- Research Themes

- Technology, Security, and Diplomacy

Related Articles

JSIS Cybersecurity Report: How Should the Tech Industry Address Terrorist Use of Its Products?

Contextualizing the iPhone Encryption Debate

Countering Disinformation: Russia’s Infowar in Ukraine

Latest news.

- Spring Course: Media And Information Technology In Global Conflict

- War in the Middle East Lecture Series

- Sasha Senderovich receives prestigious AATSEEL 2023 Best First Book Award

Related Centers

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach

Whistleblower describes how firm linked to former Trump adviser Steve Bannon compiled user data to target American voters

- ‘I made Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare tool’: meet the data war whistleblower

- Mark Zuckerberg breaks silence on Cambridge Analytica

The data analytics firm that worked with Donald Trump’s election team and the winning Brexit campaign harvested millions of Facebook profiles of US voters, in one of the tech giant’s biggest ever data breaches, and used them to build a powerful software program to predict and influence choices at the ballot box.

A whistleblower has revealed to the Observer how Cambridge Analytica – a company owned by the hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer, and headed at the time by Trump’s key adviser Steve Bannon – used personal information taken without authorisation in early 2014 to build a system that could profile individual US voters, in order to target them with personalised political advertisements.

Christopher Wylie, who worked with a Cambridge University academic to obtain the data, told the Observer : “We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons. That was the basis the entire company was built on.”

Documents seen by the Observer , and confirmed by a Facebook statement, show that by late 2015 the company had found out that information had been harvested on an unprecedented scale. However, at the time it failed to alert users and took only limited steps to recover and secure the private information of more than 50 million individuals.

Cambridge Analytica: the key players

Alexander Nix, CEO

An Old Etonian with a degree from Manchester University, Nix, 42, worked as a financial analyst in Mexico and the UK before joining SCL, a strategic communications firm, in 2003. From 2007 he took over the company’s elections division, and claims to have worked on 260 campaigns globally. He set up Cambridge Analytica to work in America, with investment from Robert Mercer.

Aleksandr Kogan, data miner

Aleksandr Kogan was born in Moldova and lived in Moscow until the age of seven, then moved with his family to the US, where he became a naturalised citizen. He studied at the University of California, Berkeley, and got his PhD at the University of Hong Kong before joining Cambridge as a lecturer in psychology and expert in social media psychometrics. He set up Global Science Research (GSR) to carry out CA’s data research. While at Cambridge he accepted a position at St Petersburg State University, and also took Russian government grants for research. He changed his name to Spectre when he married, but later reverted to Kogan.

Steve Bannon, former board member

A former investment banker turned “alt-right” media svengali, Steve Bannon was boss at website Breitbart when he met Christopher Wylie and Nix and advised Robert Mercer to invest in political data research by setting up CA. In August 2016 he became Donald Trump’s campaign CEO. Bannon encouraged the reality TV star to embrace the “populist, economic nationalist” agenda that would carry him into the White House. That earned Bannon the post of chief strategist to the president and for a while he was arguably the second most powerful man in America. By August 2017 his relationship with Trump had soured and he was out.

Robert Mercer, investor

Robert Mercer, 71, is a computer scientist and hedge fund billionaire, who used his fortune to become one of the most influential men in US politics as a top Republican donor. An AI expert, he made a fortune with quantitative trading pioneers Renaissance Technologies, then built a $60m war chest to back conservative causes by using an offshore investment vehicle to avoid US tax.

Rebekah Mercer, investor

Rebekah Mercer has a maths degree from Stanford, and worked as a trader, but her influence comes primarily from her father’s billions. The fortysomething, the second of Mercer’s three daughters, heads up the family foundation which channels money to rightwing groups. The conservative mega‑donors backed Breitbart, Bannon and, most influentially, poured millions into Trump’s presidential campaign.

The New York Times is reporting that copies of the data harvested for Cambridge Analytica could still be found online; its reporting team had viewed some of the raw data.

The data was collected through an app called thisisyourdigitallife, built by academic Aleksandr Kogan, separately from his work at Cambridge University. Through his company Global Science Research (GSR), in collaboration with Cambridge Analytica , hundreds of thousands of users were paid to take a personality test and agreed to have their data collected for academic use.

However, the app also collected the information of the test-takers’ Facebook friends, leading to the accumulation of a data pool tens of millions-strong. Facebook’s “platform policy” allowed only collection of friends’ data to improve user experience in the app and barred it being sold on or used for advertising. The discovery of the unprecedented data harvesting, and the use to which it was put, raises urgent new questions about Facebook’s role in targeting voters in the US presidential election. It comes only weeks after indictments of 13 Russians by the special counsel Robert Mueller which stated they had used the platform to perpetrate “information warfare” against the US.

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook are one focus of an inquiry into data and politics by the British Information Commissioner’s Office. Separately, the Electoral Commission is also investigating what role Cambridge Analytica played in the EU referendum.

“We are investigating the circumstances in which Facebook data may have been illegally acquired and used,” said the information commissioner Elizabeth Denham. “It’s part of our ongoing investigation into the use of data analytics for political purposes which was launched to consider how political parties and campaigns, data analytics companies and social media platforms in the UK are using and analysing people’s personal information to micro-target voters.”

On Friday, four days after the Observer sought comment for this story, but more than two years after the data breach was first reported, Facebook announced that it was suspending Cambridge Analytica and Kogan from the platform, pending further information over misuse of data. Separately, Facebook’s external lawyers warned the Observer it was making “false and defamatory” allegations, and reserved Facebook’s legal position.

The revelations provoked widespread outrage. The Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey announced that the state would be launching an investigation. “Residents deserve answers immediately from Facebook and Cambridge Analytica,” she said on Twitter.

The Democratic senator Mark Warner said the harvesting of data on such a vast scale for political targeting underlined the need for Congress to improve controls. He has proposed an Honest Ads Act to regulate online political advertising the same way as television, radio and print. “This story is more evidence that the online political advertising market is essentially the Wild West. Whether it’s allowing Russians to purchase political ads, or extensive micro-targeting based on ill-gotten user data, it’s clear that, left unregulated, this market will continue to be prone to deception and lacking in transparency,” he said.

Last month both Facebook and the CEO of Cambridge Analytica, Alexander Nix, told a parliamentary inquiry on fake news: that the company did not have or use private Facebook data.

Simon Milner, Facebook’s UK policy director, when asked if Cambridge Analytica had Facebook data, told MPs: “They may have lots of data but it will not be Facebook user data. It may be data about people who are on Facebook that they have gathered themselves, but it is not data that we have provided.”

Cambridge Analytica’s chief executive, Alexander Nix, told the inquiry: “We do not work with Facebook data and we do not have Facebook data.”

Wylie, a Canadian data analytics expert who worked with Cambridge Analytica and Kogan to devise and implement the scheme, showed a dossier of evidence about the data misuse to the Observer which appears to raise questions about their testimony. He has passed it to the National Crime Agency’s cybercrime unit and the Information Commissioner’s Office. It includes emails, invoices, contracts and bank transfers that reveal more than 50 million profiles – mostly belonging to registered US voters – were harvested from the site in one of the largest-ever breaches of Facebook data. Facebook on Friday said that it was also suspending Wylie from accessing the platform while it carried out its investigation, despite his role as a whistleblower.

At the time of the data breach, Wylie was a Cambridge Analytica employee, but Facebook described him as working for Eunoia Technologies, a firm he set up on his own after leaving his former employer in late 2014.

The evidence Wylie supplied to UK and US authorities includes a letter from Facebook’s own lawyers sent to him in August 2016, asking him to destroy any data he held that had been collected by GSR, the company set up by Kogan to harvest the profiles.

That legal letter was sent several months after the Guardian first reported the breach and days before it was officially announced that Bannon was taking over as campaign manager for Trump and bringing Cambridge Analytica with him.

“Because this data was obtained and used without permission, and because GSR was not authorised to share or sell it to you, it cannot be used legitimately in the future and must be deleted immediately,” the letter said.

Facebook did not pursue a response when the letter initially went unanswered for weeks because Wylie was travelling, nor did it follow up with forensic checks on his computers or storage, he said.

“That to me was the most astonishing thing. They waited two years and did absolutely nothing to check that the data was deleted. All they asked me to do was tick a box on a form and post it back.”

Paul-Olivier Dehaye, a data protection specialist, who spearheaded the investigative efforts into the tech giant, said: “Facebook has denied and denied and denied this. It has misled MPs and congressional investigators and it’s failed in its duties to respect the law.

“It has a legal obligation to inform regulators and individuals about this data breach, and it hasn’t. It’s failed time and time again to be open and transparent.”

A majority of American states have laws requiring notification in some cases of data breach, including California, where Facebook is based.

Facebook denies that the harvesting of tens of millions of profiles by GSR and Cambridge Analytica was a data breach. It said in a statement that Kogan “gained access to this information in a legitimate way and through the proper channels” but “did not subsequently abide by our rules” because he passed the information on to third parties.

Facebook said it removed the app in 2015 and required certification from everyone with copies that the data had been destroyed, although the letter to Wylie did not arrive until the second half of 2016. “We are committed to vigorously enforcing our policies to protect people’s information. We will take whatever steps are required to see that this happens,” Paul Grewal, Facebook’s vice-president, said in a statement. The company is now investigating reports that not all data had been deleted.

Kogan, who has previously unreported links to a Russian university and took Russian grants for research, had a licence from Facebook to collect profile data, but it was for research purposes only. So when he hoovered up information for the commercial venture, he was violating the company’s terms. Kogan maintains everything he did was legal, and says he had a “close working relationship” with Facebook, which had granted him permission for his apps.

How the Cambridge Analytica story unfolded