- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples History American Democracy

What Does America Mean to Me: A Personal Reflection

Table of contents, freedom and democracy, diversity and cultural tapestry, innovation and entrepreneurship, the pursuit of dreams.

- Kazin, M., Edwards, R., & Rothman, A. (2017). The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton University Press.

- Wood, G. S. (2011). The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States. Penguin.

- Ellis, J. J. (2013). American Dialogue: The Founders and Us. Vintage.

- Smith, R. (2012). American Democracy in Peril: Eight Challenges to America's Future. CQ Press.

- Foner, E. (2017). Give Me Liberty!: An American History (Vol. 1). WW Norton & Company.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- 19Th Century

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Abigail Adams

- Salem Witch Trials

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

America’s Field Trip

The Contest

What Does America Mean to You?

In 2026, the United States will mark our Semiquincentennial: the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Today’s young people are the leaders, innovators, and thinkers who will shape the next 250 years — and it’s important their voices are heard as we commemorate this historic milestone.

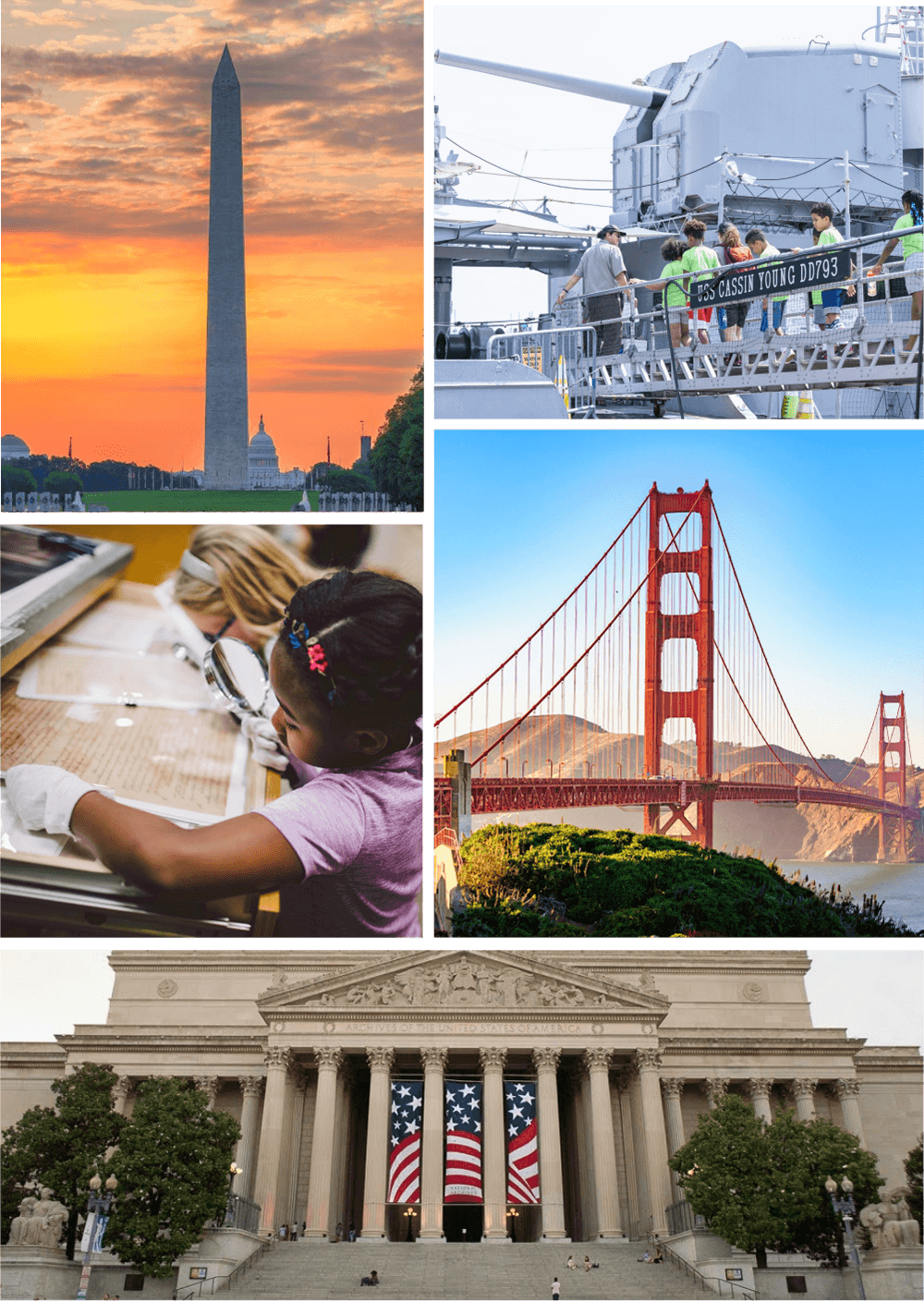

America’s Field Trip is a new contest that invites students across the country in grades 3–12 to be part of America’s 250th anniversary by sharing their perspectives on what America means to them — and earning the opportunity to participate in unforgettable field trip experiences at some of the nation’s most iconic historic and cultural landmarks.

Students may submit artwork, videos, or essays in response to the contest’s prompt: “What does America mean to you?”

The Field Trips

Extraordinary Visits to Iconic National Landmarks

Twenty-five first-place awardees from each grade level category will receive free travel and lodging for a 3-day, 2-night trip to a select historical or cultural site where they will experience one of the following:

- Tour of the Statue of Liberty in New York

- Tour and hike at Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Montana

- Weekend at Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado

- Unique tours at the National Archives or the Library of Congress in Washington, DC

- Special tours at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, National Museum of African American History and Culture, or the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC

- Explore America’s iconic financial capital, New York City, with private tours of Federal Reserve Bank of New York Museum and Learning Center and The Bank of New York Mellon , the country’s oldest bank

- Experience National Parks of Boston with a special visit to the USS Constitution and a sunset cruise to Spectacle Island

- Candlelight tour at Fort Point at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge

- Costumed roleplaying experience at American Village in Alabama

Second-place awardees will receive a $500 cash award. The teacher associated with the top scoring student submissions in each grade level category will receive a $1,000 cash award.

See full list of field trips

Submission Guidelines

- Elementary School (3rd to 5th Grade): Students may submit artwork, including physical or digital artwork through a high-res photo or a short essay (up to 100 words).

- Middle School (6th to 8th Grade): Students may submit artwork or a video (up to two minutes).

- High School (9th to 12th Grade): Students may submit an essay (up to 1,000 words) or a video (up to two minutes).

Judging Criteria

A diverse panel of judges consisting of current and former teachers will consider the submissions based on the following weighted criteria:

- CLARITY OF IDEA [25%]: How well does the Entrant use both their personal and academic experiences to clearly address the Question? Does the Entry effectively convey ideas, emotion, or a story visually or with words by acknowledging the past or celebrating America’s achievements and possibilities for the future? Does the response offer fresh insight and innovative thinking?

- STUDENT VOICE [50%]: Is there passion in the Entry or a point-of-view that showcases a unique perspective on the diverse range of different experiences that make America unique in an original/authentic way?

- PRESENTATION [25%]: What makes the submission content more compelling, fresh, or interesting than other Entrants’ content in their grade level category?

Want to stand out? Create something that feels special to you and has a personal touch. And remember, you don’t have to focus on our country’s past — you can talk about America’s future too. Finally, be creative and think outside the box!

Resources for Teachers

Teachers and school administrators will play an important role in engaging students and school communities in this contest and commemorating America’s 250th anniversary.

Students participating in the America’s Field Trip contest will be challenged to think critically about the nation’s journey to becoming a more perfect union, reflecting on the pivotal events and historical figures that have shaped the country.

In partnership with Discovery Education, America250 has developed standards-aligned lesson plans to assist educators in bringing the America’s Field Trip contest to their classrooms. Educator resources can be downloaded here.

In partnership with

Funding provided by The Bank of New York Mellon Foundation

What is America250?

America250 is a nonpartisan initiative working to engage every American in commemorating and celebrating the 250th anniversary of our country. It is spearheaded by the congressionally-appointed U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission and its nonprofit supporting organization, America250.org, Inc.

How can I bring America’s Field Trip into my classroom?

America250 partnered with Discovery Education, the worldwide edtech leader, to develop custom educational programming that helps students deepen their understanding of America’s 250th anniversary and encourages participation in the America’s Field Trip contest with ready-to-use resources and activities for teachers.

What should I submit?

Submission requirements differ by age group.

Elementary School ( 3rd to 5th Grade): Students are asked to submit artwork in response to the prompt or a short essay (up to 100 words). Artwork can include physical artwork like sculptures, painting, photography, etc. submitted through a high-res photo or a digital drawing.

Middle School (6th to 8th Grade): Students are asked to submit artwork or a video (up to two minutes).

High School (9th to 12th Grade): Students are asked to submit a written essay (up to 1,000 words) or a video (up to two minutes).

How will field trips be selected, and who will be chaperoning the trips?

Trips will be organized by America250 and chaperoned by the recipient’s parent or legal guardian along with other field trip recipients. First-place awardees will get to express their preference for trips, and final locations will be determined based on age group, availability, and recipient preference.

Can students bring their families on their Field Trips?

Students are required to have one chaperone, which must be a parent or legal guardian.

Will America’s Field Trip programming continue after 2024?

Yes, this year is a pilot program that America250 hopes to grow and expand, including with more field trips and award recipients in 2025 and 2026.

Have more questions? See the FAQs . Read the official contest rules here .

Ready to Share What America Means to You?

Once you finish responding to the prompt, you must have a teacher, parent, or legal guardian upload your submission for consideration.

Field Trip Hosts

Engaging students nationwide to celebrate America’s 250th anniversary!

A new contest inviting students in grades 3–12 to share their perspectives on what America means to them — and earn the opportunity to participate in field trip experiences at some of the nation’s most iconic historic and cultural landmarks.

Continue to the site

Stanford University

What Does It Mean to Be an American?: Reflections from Students (Part 5)

The following is Part 5 of a multiple-part series. To read previous installments in this series, please visit the following articles: Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 .

On December 8, 2020, January 19, 2021, March 16, 2021, and May 18, 2021, SPICE posted four articles that highlight reflections from 33 students on the question, “What does it mean to be an American?” Part 5 features eight additional reflections.

The free educational website “ What Does It Mean to Be an American? ” offers six lessons on immigration, civic engagement, leadership, civil liberties & equity, justice & reconciliation, and U.S.–Japan relations. The lessons encourage critical thinking through class activities and discussions. On March 24, 2021, SPICE’s Rylan Sekiguchi was honored by the Association for Asian Studies for his authorship of the lessons that are featured on the website, which was developed by the Mineta Legacy Project in partnership with SPICE.

Since the website launched in September 2020, SPICE has invited students to review and share their reflections on the lessons. Below are the reflections of eight students. The reflections below do not necessarily reflect those of the SPICE staff.

Giyonna Bowens, Texas Growing up as a military brat, with my father being a retired sergeant major (SGM) of 30 years, I realized that there is so much to explore in the world, and behind every face, there is a story. It has taught me to be an open-minded individual and to look past racial/socio-economic stereotypes and to truly get to know people for who they are. While being an African American female has inspired me to speak up against racial and social injustice, it has ingrained in me that anyone can do anything they set their minds to, so long as they have a strong work ethic and a positive attitude. What it means to be an American to me is to be educated on other cultures and ethnicities, to fight against gender inequality, and to accept people, no matter their sexuality/gender identity, to progress forward in America.

Austin Akira Fujimori, California My family loves to travel, so I have been able to experience and observe different types of people and cultures across the world. Because of my Chinese and Japanese heritage, I have frequently visited Japan and China, where it seems that traditional culture has had a very strong effect on people. Based in part on how their citizens dressed and acted, I could easily tell that there was a distinct difference between Chinese and Japanese people. In the U.S., there doesn’t seem to be a dominant culture that influences people. Because America is so diverse, many cultures are brought to the table, allowing people born in the U.S. to live without the influence of one dominant culture. For me, to be American is to be unique, to be born with the freedom to be whoever you want to be.

Eddie Shin Fujimori, California Being born in a family that comes from China and Japan, I have often considered other countries’ views of Americans. Confidence especially has always stood out as an essential part of what it means to be American. In my experience, this confidence is usually interpreted by people in other countries to be haughty and arrogant. However, I don’t see this “overconfidence” as negative. The trait is directly correlated to Americans strongly believing that working towards what they believe in—as evidenced in the Black Lives Matter movement in response to the murder of George Floyd and the anti-Asian hate protests following the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans—can lead to considerable amounts of change. Being American means having the confidence to aspire towards a better society, knowing that we can have an enormous influence on the rules and laws passed.

Nāliʻipōʻaimoku Harman, Hawaii He Hawaiʻ i au. I identify as a Native Hawaiian, but I am of mixed race. The word American has little to no cultural relevance to me. The truth is, I do live in the United States but the American ways don’t match up with my life, how I think and what our traditions and values are. Every day, I wake up and speak Hawaiian, not English, with my family. When I watch the television and see people refusing to wear masks citing individual rights as justification, I feel angry. I am in the habit of wearing a mask in public and even when meeting with family because I know that others’ safety is more important than my personal discomfort. My choices affect others, and my successes are not mine alone.

Lanakila Jones, Hawaii Being American to me is about having freedom in doing what I love. It’s being able to express myself in the ways I want to. As a Hawaiian, I am truly aware of the history of our nation. Our Queen, Liliʻuokalani, fought her hardest for her people and her beloved nation until the end. As a Hawaiian living in America, I value her integrity and feel the need to pursue it. We need to implement change to stop the ongoing challenges of today. We can’t change the past, we can only build a better present. Being American to me not only means grasping the thought of change, but actually engaging in it to primarily stop ongoing hatred amongst the citizens of our country. To be American means to fulfill equity amongst us to be greater.

Violet Lahde, California For me being American means assurance; a positive declaration intended to give confidence; a promise. As many of us have learned through our years living in America, we bear many privileges that others don’t, whether inside or outside of our borders. While we may still be fighting for those who can’t, I can still say America has offered me many opportunities, along with a feeling of freedom. This America isn’t and may never be perfect, but holds promise for the future. It allows me to have confidence in anything I want to achieve or change. So regardless of the injustice and prejudice that has become so apparent, I can say I am grateful for the safety and optimism America allows me to have.

Kristine Pashin, California If I asked you to draw an American, who would you draw? At its core, America is a country nurtured by unique individuals who foster ethnic and cultural diversity. As the daughter of two Bulgarian immigrants, I’ve oscillated between being “too American” and “not American enough.” To avoid confusion, I got used to separating my Bulgarian American identity into two personas. When I wore my nosia (a traditional folk outfit), I considered myself Bulgarian; in Western clothes, I was American. However, I realized that my outfits were a guise—covering up insecurities about my identity. An “American” isn’t someone who can simply be identified by their appearance, as we cannot typify America with one identity. Thus, there is no way to draw an American, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Ernesto Saenz Peña, California To me, “being an American” means being open-minded to new ideas and change. My teachers would always stress the importance of these qualities. Embracing these qualities has allowed me to learn about the diverse cultures in America. I learned Spanish from a young age, and it has allowed me to not only communicate with my parents and family in Mexico, but also has allowed me to see different points of view from others outside of and within America. Seeing other points of view has helped us to bring about changes throughout our history. For example, we abolished slavery, created more rights for farmworkers, and we continue to push against systemic racism. Being American means that we can speak up against what we think is wrong without fear of being punished.

What Does It Mean to Be an American?: Reflections from Students (Part 4)

Spice’s rylan sekiguchi is the 2021 franklin r. buchanan prize recipient, what does it mean to be an american: a webinar for educators, february 20, 2021, 10am pst.

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Native American — What it Means to Be an American

What It Means to Be an American

- Categories: American Identity Native American

About this sample

Words: 678 |

Published: Sep 5, 2023

Words: 678 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, what patriotism means for american identity, the american dream's place in history.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 863 words

3 pages / 1328 words

3 pages / 1386 words

1 pages / 1139 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Native American

Philip Deloria’s book “Playing Indian” provides a thought-provoking analysis of the phenomenon of non-Native Americans adopting Native American cultural practices and identities. Deloria argues that this practice is not simply a [...]

The Sioux, also known as the Dakota or Lakota, are a Native American tribe with a rich and complex history. Their culture, traditions, and way of life have been shaped by centuries of resilience and adaptation to the changing [...]

“My Father’s Song” is a poem by Simon J. Ortiz that delves into the relationship between the speaker and his father, as well as the speaker’s connection to his Native American heritage. The poem explores themes of tradition, [...]

In Chapter 4 of the book "Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States," the author Manuel G. Gonzales presents a comprehensive overview of the Mexican-American experience during the 20th century. This chapter focuses [...]

The understanding of the readers is dependent on the manner in which they interpret the symbols used in literary works. Symbolism is a literary device which entails the conveying of specific themes and messages through symbols. [...]

Smoke Signals is a film that beautifully captures the complexities of Native American identity and the universal themes of forgiveness and healing. Directed by Chris Eyre and written by Sherman Alexie, the film tells the story [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

- School and College News

- Arts & Culture

- Community Impact

- Entrepreneurship

- Health & Well-Being

- Research & Discovery

- UConn Health

- University Life

- UConn Voices

- University News

May 11, 2022 | Kimberly Phillips

In Defining ‘America,’ Students Critique, Criticize, and Warn of What Is and Could Be

'If people value democracy, trust each other and the democratic process, they will build a better nation'

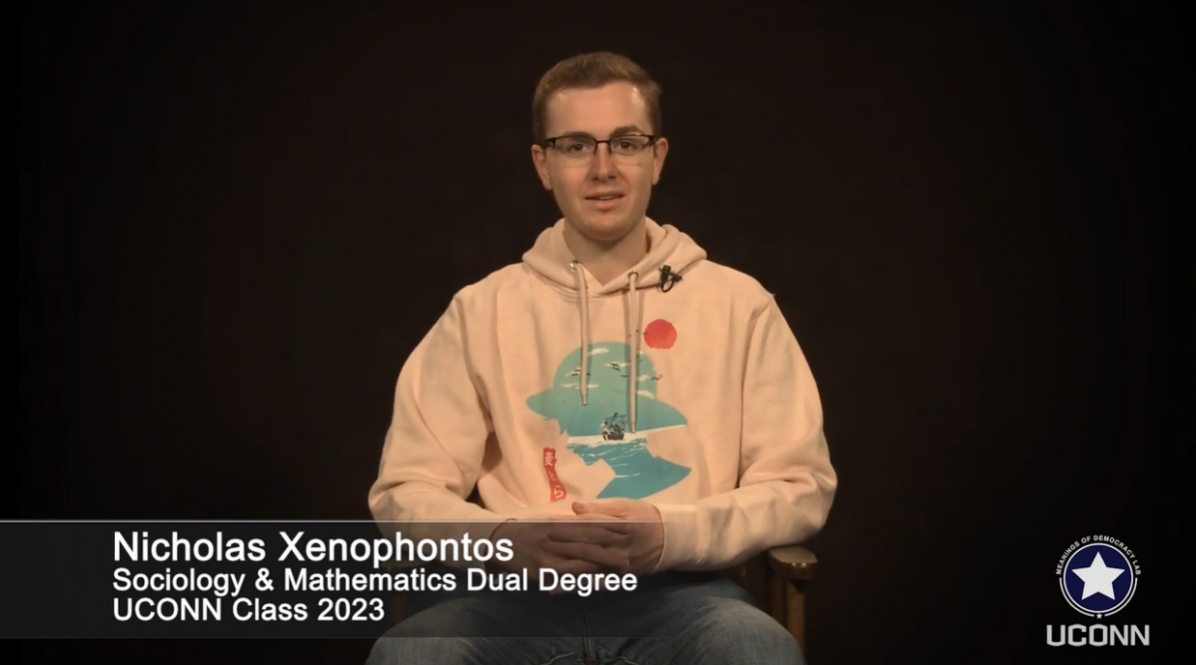

Nicholas Xenophontos ’23 (CLAS) reads his prize-winning essay on the meaning of America (contributed photo).

For today’s thinkers and doers and the generations that come after, Ruth Braunstein has one question: What does America mean to you?

“The public is always thinking about it whether they know it or not,” she says. “Our assumptions about what it means to be American are embedded in so many of our conversations about public policy. Who deserves access to public institutions and resources, whether we should allow certain religious groups to display their religious symbols in public, do you need to be a taxpayer to be a good American? There are so many ways this plays out in the background of our policy debates.”

Most of the time, though, the general public doesn’t get to answer, says Braunstein, an associate professor of sociology who runs UConn’s Meanings of Democracy Lab . Politicians and elected officials, institutional and corporate top brass typically make decisions that end up defining “America” for those who comprise it – like what holidays are observed on the public school calendar.

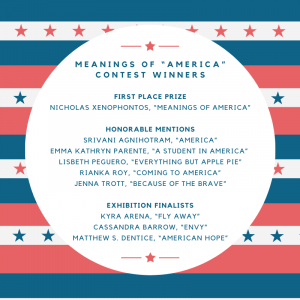

Last fall, she sought to change that with the help of political science professor and President Emeritus Susan Herbst, who came across a 1937 contest in Harper’s Magazine soliciting written submissions that attempted to define America in that time.

“We can’t see all the answers submitted in the 1930s, but from what we can tell, they are the standard ones: that democracy is fragile, citizens are not always informed and are open to manipulation, and there are indeed problematic leaders with poor intentions,” Herbst says. “Like many intellectuals in the 1930s, there was tremendous concern that the United States could see the rise of authoritarian movements right here on our own soil.

“We were watching the rise of Adolph Hitler and other dictatorial leaders and many American journalists thought the topic of our own future was a vital one,” she continues. “While our contemporary situation is different, we do have the same fears as we watch demagoguery at home and abroad. The parallels to the 1930s, and shared concerns, are stunning, in fact.”

Rianka Roy, a graduate student in sociology who received an honorable mention and one of five $100 prizes in the Democracy Lab’s “Meanings of ‘America’ Project,” offered the acrostic poem “Coming to America” that describes her immigration to America and questions whether the “alien” designation on her passport – despite legal status – will thwart a sense of belonging.

“Millions of immigrants have come and settled in this country. They love the country, work for it, and cherish the opportunities they find here,” she says of the poem. “But often their views are ignored. They are stereotyped as outsiders who threaten national security and jeopardize the economy. On the one hand, we want to embrace our adopted home, on the other hand, we are made to feel unwelcome.”

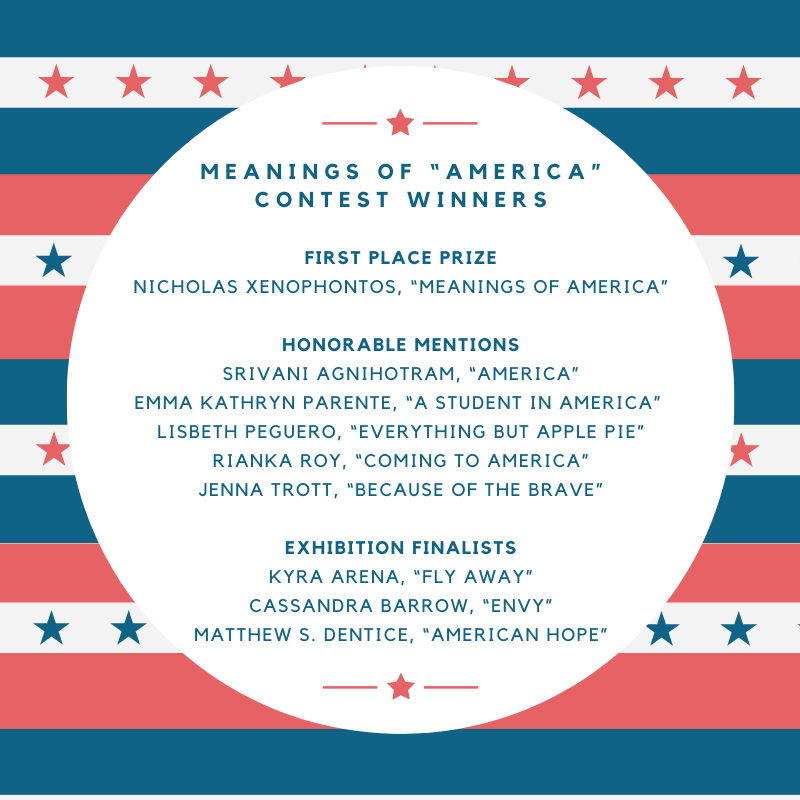

Braunstein says she received between 50 and 100 entries for $1,000 in prize money funded by UConn’s Humanities Institute and the Department of Sociology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences . There was one first-place winner, five honorable mentions, and three finalists . Submissions came from students throughout UConn who were told to go beyond the usual patriotic rhetoric in their submissions, be creative in their ways of looking at the country, and ultimately “rally enthusiasm” as the Harper’s contest also called for.

“There were a lot of students expressing concern about a more exclusionary vision of the country and they were very critical of that,” Braunstein says. “There were many who talked about racial injustice and the movements that have emerged to resist racial injustice, including Black Lives Matter. I was impressed with the thoughtfulness of the responses – some very critical, some holding this tension between critique and patriotism and hope.”

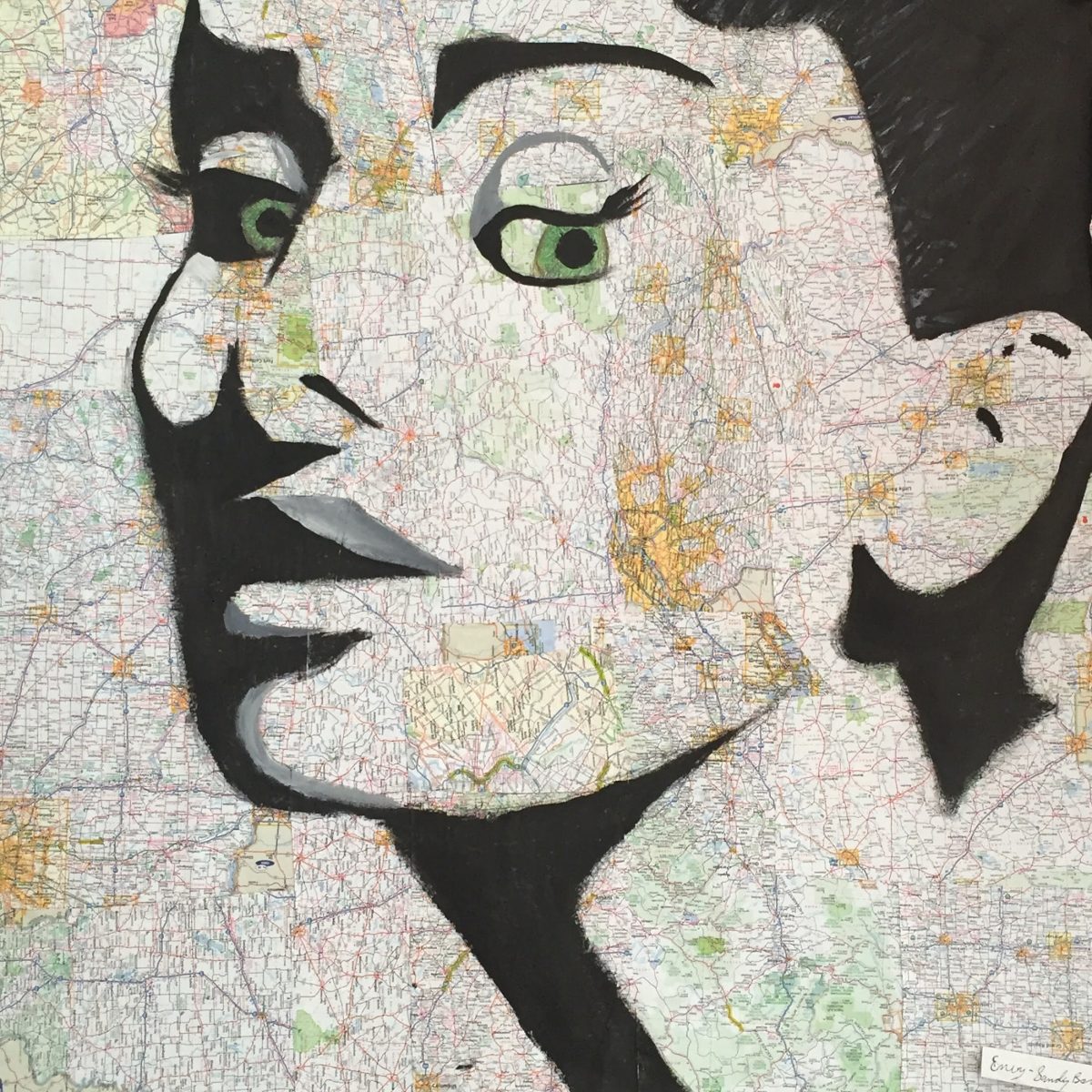

Sandy Barrow ’19 (CLAS) ’22 MPH submitted her painting “Envy,” a silhouette portrait of Audrey Hepburn done on a background of old United States maps, to illustrate the American drive to be better and do more, oftentimes at the cost of lost identities from going the wrong way.

“Look out for her because she’s sly,” Barrow says of the painting done in black acrylic. “Envy and those feelings of competitiveness they aren’t always overt. They’re a little bit throughout the day or a little bit throughout the month or the year. They’re sneaky and they can have bigger impacts on your mental health and wellbeing than you realize. When you formulate your goals and your journey, you’re bombarded with other people’s expectations and oftentimes you’re not able to forge your own path or be happy with the path you chose. When you see her, you get captivated.”

It’s a cycle that’s unique to America, Barrow, who was a contest finalist, says: “We work harder and have longer workweeks and less care for our workers than many other comparable and developed countries.”

For contest winner Nicholas Xenophontos ’23 (CLAS) the fact that “America” doesn’t have a definition is perhaps its greatest strength. In his essay, “Meanings of America,” he notes the country is free, brave, and just – but that allows landlords the freedom to raise rent, advisors to recommend stifled tears to manifest courage, and siblings to support opposing sides of laws and differing views of good and evil.

“Try any core pillar of American identity and you will find hypocrisy, redundancy, and irony,” Xenophontos says in the essay that won the $500 top prize. “Our entire history is one of betrayal to any of our intrinsic merits, starting with the colonial destruction of the Native society, land, culture.”

Because of this tension, America is meaningless, he says, allowing people to define it for themselves.

“My inspiration came from a deeper cynicism and slight nihilism that permeates the mood of my generation,” he says. “If we don’t discuss the personal meanings we hold to our nations or institutions, then those tainted values that cement themselves in our lives will remain unquestioned. We must talk about what America means to us, for the hope is that our voices lift each other up and we hear each other. After all, talking does us very little good if we don’t open our ears and minds to what is actually being said.”

Braunstein says she wasn’t surprised the contest drew students from majors outside the expected political science, sociology, and public policy realms. In the Democracy Lab, her students come from a range of majors, including philosophy, business, and computer science, and they are “excited by the opportunity to stretch their legs a little bit and think about topics they don’t get to think about as much in their coursework but are personal interests of theirs.”

They’ve helped with the lab’s website design, spread word of the contest, served as contest judges, and promoted the full project on Twitter and Instagram . Staff at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning videoed the winners talking about their submissions.

Now the students and Braunstein are looking ahead to what’s next – a documentary-style podcast, “The Battle for the American Story.”

Recording of the first episode happened in late April.

“In the podcast, we reflect on where we are exposed to these different versions of the American story, starting in childhood, at church, through rituals, and during holidays,” Braunstein says. “What are the moments when people begin to question some of those ideas they have been exposed to – like the myth that America is a sacred ‘Christian nation’ – and who are the voices today who are critiquing that version or promoting alternate versions of the story? Who is promoting a story of the country as a racially and religiously diverse country that has a flawed past but is working toward the vision of a more perfect union in the future?”

Talking about America’s past is important for its future, as Xenophontos says, and Herbst agrees.

“As a social scientist, you always want to ask ‘So what and who cares?’ when you are studying a phenomenon like American public opinion. I do think it is important to get inside the heads of average citizens, as best we can. If people value democracy, trust each other and the democratic process, they will build a better nation,” she says. “They will work together and make sacrifices for the greater good.”

Recent Articles

April 22, 2024

A Dual Mission: Growing Green, UConn Professor Earns Income Licensing Plants that Fight Climate Change

Read the article

Meet University Scholar Christian Chlebowski

UConn Health Continues Commitment to Sustainability

(2000 Words) What Does It Mean to Be an American Essay Samples

The concept of American identity is a subject of great depth and complexity. It encompasses diverse perspectives, experiences, and values that shape the fabric of the nation. In this essay, we embark on a journey to understand “ what does it mean to be an American essay .” Delving into the cultural, historical, and ideological aspects, we explore the essence of American identity, values, and the profound sense of belonging that unites a diverse population.

Related: Should Marijuana Be Legalized Essay +Example

Key Takeaways

- Ideological Identity: Being American isn’t just where you’re from, but the commitment to ideals like freedom and equality.

- Cultural Diversity: America’s a melting pot of cultures and religions, not defined by one race or background.

- Freedom and Liberty: Being American means speaking freely, valuing diverse paths, and defending rights earned through history.

What Does It Mean to Be an American Essay: Unraveling the Layers

The american dream: aspirations and opportunities.

The American Dream is a cornerstone of the nation’s identity. It symbolizes the belief that anyone can achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and perseverance. This dream has been a driving force for individuals seeking opportunities on American soil, contributing to the nation’s unique identity.

Cultural Melting Pot: Embracing Diversity

America’s strength lies in its cultural diversity. With a rich tapestry of ethnicities, languages, and traditions, the nation is a melting pot where people from around the world come together. The idea of unity in diversity is at the heart of what it means to be an American.

Shared Values: Freedom, Democracy, and Equality

Freedom, democracy, and equality are the pillars upon which America was built. The Constitution guarantees individual rights, and the democratic process empowers citizens to shape the nation’s future. The continuous pursuit of these values defines the American identity.

Patriotism and Civic Responsibility

Being an American entails a sense of patriotism and civic duty. Citizens actively participate in their communities, exercise their right to vote, and uphold the principles that the nation stands for. This active engagement is a reflection of a genuine commitment to the country.

Land of Opportunities: Pursuit of Success

Opportunity is abundant in America, where innovation and entrepreneurship are celebrated. Immigrants often view the country as a land of possibilities, where they can carve out a better life for themselves and their families.

Inclusivity and Acceptance: Embracing Differences

Being an American means embracing the values of inclusivity and acceptance. The nation’s history has been shaped by waves of immigrants, each contributing their unique talents and perspectives to the mosaic of American culture.

Cultural Impact: Music, Art, and Literature

American culture has a global influence, with its music, art, and literature resonating across borders. From jazz to Hollywood films, the nation’s creative output has left an indelible mark on the world stage.

Resilience in Adversity: Overcoming Challenges

The American spirit is characterized by resilience in the face of challenges. Whether it’s recovering from natural disasters or navigating economic downturns, Americans exhibit a remarkable ability to bounce back and rebuild.

Education and Innovation: Pushing Boundaries

Education and innovation are highly regarded in American society. The nation’s universities and research institutions drive advancements in science, technology, and various fields, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge.

The Pursuit of Happiness: Personal Fulfillment

The pursuit of happiness is an inherent right enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Americans are encouraged to pursue their passions, interests, and dreams, contributing to a society that values individual fulfillment.

Equality of Opportunity: Breaking Barriers

The American narrative champions the idea of equal opportunity for all. While challenges related to inequality persist, the ongoing efforts to dismantle barriers and achieve social justice continue to define the American journey.

Historical Legacy: Learning from the Past

America’s history, though complex, is a testament to growth and progress. From the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement to lessons learned from past mistakes, the nation continually evolves in pursuit of a more just society.

National Pride: Celebrating Achievements

From space exploration to medical breakthroughs, Americans take pride in their nation’s achievements. These milestones underscore the nation’s capacity for innovation and its commitment to advancing human knowledge.

Related: Do Video Games Cause Violence Essay: Separating Fact from Fiction

What Does it Mean to Be an American Example Essay?

Defining what it truly means to be American is like trying to capture a gust of wind in your hands. Historian Philip Gleason once pondered, “Is it about where you’re from or who you are deep down?” His take was refreshingly simple: “Being American isn’t about where your roots lie, what words you speak, or which gods you pray to.

It’s about locking arms with the ideals of freedom, equality, and democracy.” In a nutshell, he implied that wearing the American badge involves adopting the way of life that’s stitched together with these ideals.

Yet, let’s pause for a moment and ask ourselves, does this catch the whole spirit of being American? This journey will navigate through the heart of American identity, questioning whether just riding the cultural wave is enough, or if there’s more to it, by delving into the vibrant tapestry of American culture.

Imagine stepping into the shoes of being American and you’re immediately handed a microphone for free speech. Now, that’s a badge that American souls wear with pride. Beyond the nation’s borders, you might hear whispers that Americans are, well, a tad louder or maybe just refreshingly upfront.

Why? It’s all tied to this cornerstone of freedom of expression deeply embedded in the culture. Here, it’s like each citizen’s inner thoughts are given a stage to dance on. It’s like being able to say what you really mean without navigating through a maze of pleasantries.

While this kind of unfiltered openness might be a bit of a culture shock elsewhere, it isn’t meant to be brash; it’s just about making your point with conviction. Gandhi summed it up perfectly: “A resounding ‘no’ that echoes your beliefs is mightier than a weak ‘yes’ that’s only meant to please or avoid a ruckus.”

This freedom is enshrined in the First Amendment, although sure, there are some boundaries – hate speech doesn’t get a pass. And remember, part of being American is embracing the rainbow of cultures and faiths that sprinkle the landscape.

Here’s where the plot thickens – being American paints you into the most colorful cultural mosaic on Earth. Forget about tracing your lineage back to one spot on the map; this is a land where the mixtape of cultures, languages, and beliefs blasts from every corner.

They say that almost everyone here carries a bit of Europe or Africa in their veins, thanks to ancestors who took the journey across oceans. Some even say that unless your roots stretch back to Native American soil, you’re not fully home.

But, and here’s the twist, it’s not about the color of your skin or the melody of your prayers. It’s about embracing a set of values that are as American as apple pie, values that shape politics, economics, and the very soul of the nation.

When you close your eyes and think of America, the words freedom and liberty rush in like old friends. We’ve already dipped our toes into the freedom of speech stream, but let’s wade a bit deeper. This nation’s veins pulse with the drive to live life by your own rules, liberty that past generations paid for with blood, sweat, and tears.

So, when the final curtain falls, what’s the grand conclusion? Being American isn’t just a birthright; it’s a journey of embracing a culture, a way of life, and a set of values. It’s about basking in the sun of freedom of expression and being a thread in the vivid tapestry of diversity.

It’s cherishing liberty like a treasure and owning the responsibility that comes with it. In the end, being American isn’t just where you start; it’s where you stand and how you stand for it, no matter where you began.

FAQs About American Identity and Belonging

What values are integral to the american identity.

The American identity is rooted in values such as freedom, democracy, equality, and individual rights. These principles shape the nation’s history, culture, and way of life for its citizens.

How does cultural diversity contribute to being American?

Cultural diversity enriches the American experience by bringing together various perspectives, traditions, and languages. It fosters a sense of unity while celebrating the unique contributions of different communities.

Is the American Dream still attainable?

The attainability of the American Dream is a subject of debate. While challenges exist, many individuals continue to achieve success through hard work and determination, illustrating the enduring spirit of the dream.

How does the concept of patriotism manifest in American society?

Patriotism in America is often expressed through gestures like displaying the flag, participating in civic activities, and honoring veterans. It reflects a deep love and commitment to the nation.

What role does education play in American identity?

Education is highly valued in American society. It empowers individuals to pursue their aspirations, contribute to society, and drive innovation in various fields.

How does America’s history shape its present identity?

America’s history, including its triumphs and struggles, informs its present identity. Lessons from the past guide ongoing efforts to create a more inclusive and equitable society.

Conclusion: Embracing the American Spirit

In conclusion, the question “What does it mean to be an American essay” encapsulates a complex and multifaceted inquiry. American identity is shaped by history, values, diversity, and shared aspirations. It embodies a spirit of unity, progress, and resilience that continues to evolve and define the nation.

As we celebrate the unique tapestry of cultures and experiences that constitute being American, let us recognize the common threads that bind us together.

NB : Unlock your time and potential by entrusting us with your essays. Our expert writers are ready to bring your ideas to life, ensuring top-quality, original content tailored to your needs. Let us handle the heavy lifting while you focus on what truly matters. Say goodbye to stress and hello to success – get your essays written with us today. Order Now

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

What does America Mean to Me? a Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values

How it works

In 2016, Donald Trump used the slogan ‘Make America Great Again’ as a platform for his presidential race. The slogan implied that the United States of America was no longer great and needed major repairs. Although I acknowledge that America is facing many critical issues, I feel that it is still a great country. This is probably best exemplified by the fact that many people facing oppression, poverty, and warfare in their own country choose America as a refuge. So, what makes America special above other countries? Some of the things I love about this country include the Constitution, opportunity, National Parks, and people who give.

- 1.1 References

What America Means to Me: A Sanctuary of Freedoms and Opportunities

I believe our founding fathers were inspired when they wrote the Constitution. They looked at other governments, primarily England, and considered issues that could arise between governing bodies. Our Constitution sets rules for government structure, voting, the relationship between Federal government and State governments, and a variety of freedoms, including freedom of speech and freedom of religion.

The government structure and voting rules provide a system of checks and balances so that no one entity can usurp power. The freedoms guaranteed that people can express ideas and practice religion as they choose without being suppressed by the government. The original Constitution set a model that other countries have partially followed. It is a unique document and one worth preserving.

Many people have immigrated to America because they saw it as a place to start over, realize dreams, or build a life free from tyranny. People have come here with almost nothing in their pockets and have managed to build a life for themselves and their descendants. Other people come from war-torn countries and find peace and a new life. Granted, building a new life is more difficult for some than for others, but the opportunities are still better here than in many countries.

The model for creating a national park system started here in America. It is so important to protect wilderness areas for everyone to enjoy, or else many of them will be destroyed. I love the outdoors and visiting some of the beautiful areas in our country. I think it is important to preserve areas so that people of all types can learn about ecology, nature, and environmental impacts. I think it is also important that all have an opportunity to take a break from the urban scene and enjoy the serenity of wild areas.

I don’t know how America compares to other countries for people helping others, but it seems that we have a lot of individuals and groups who take the time to help others for all kinds of reasons. A giving spirit creates good relations between all parties involved. Good relations can lead to more constructive solutions to issues as opposed to being only concerned about one’s own desires.

America has a lot to offer its citizens, from an inspired constitution to people that are willing to help others. Granted, it has its challenges, and many of its good ideals are being challenged. We as a people need to realize what a great country this is and always work to preserve our privileges and freedoms.

- Johnson, M. (2019). The Making of the Constitution. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Smith, L. (2020). “Checks and Balances in the U.S. Government”. Journal of Political Studies, 45(2), 300-318.

- Anderson, P. & Williams, J. (2017). “Immigration and the American Dream: A Century Review”. Sociological Review, 62(4), 629-652.

- Davis, R. (2021). “Challenges and Ideals: The State of Modern America”. American Sociological Review, 86(3), 482-510.

- Washington Post. (2016, May 15). “The Story Behind ‘Make America Great Again'”. The Washington Post.

Cite this page

What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values. (2023, Aug 17). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/

"What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values." PapersOwl.com , 17 Aug 2023, https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/

PapersOwl.com. (2023). What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/ [Accessed: 22 Apr. 2024]

"What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values." PapersOwl.com, Aug 17, 2023. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/

"What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values," PapersOwl.com , 17-Aug-2023. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/. [Accessed: 22-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2023). What Does America Mean to Me? A Personal Reflection on Identity, Opportunity, and Values . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-does-america-mean-to-me-a-personal-reflection-on-identity-opportunity-and-values/ [Accessed: 22-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Your cart is empty

You have no recently viewed items..

- (800) 388-4512

- Free Civics Resources

- Civics Curriculum Supplements

- Submit Purchase Order

- About our Seminar Program

- How to Host a Seminar

- Watch our Recorded Seminar

- Declaration of Independence

- United States Constitution

- Bill of Rights

- Amendments 11-27

- Principles of Liberty

- Proclaim Liberty (study Course)

- The Weekly Constitution

- Our Ageless Constitution

- The Urgent Need for a Comprehensive Monetary Reform

- Freedom Stories

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

- Shipping & Delivery

- Terms of Service

What Does America Mean to You?

Some of you may remember hearing the story of Peter Fetcher, an 18-year-old young man trapped behind the Berlin Wall in East Germany. Peter and his close friend, Helmut Kulbeik, yearned to be free from communist oppression. They dreamed of America – the land of freedom and opportunity. Their desire for freedom was so strong that they finally determined there was no cost too great to obtain it.

On August 17, 1962 the two young men left their bricklaying job for a lunch break and hurried to a little-used factory near Checkpoint Charlie that gave an easy view of the Berlin Wall just a few hundred yards away. Their intent was to wait until dusk to make their break, but around 2pm they heard voices close by and decided to make a break for it. They squeezed through a small window, hurtled over a barbed wire fence, and darted across the death strip toward freedom, Peter in the lead.

Sprinting past Peter, Helmut reached the wall first and scaled the 6-foot barrier crowned with barb wire as bullets peppered the ground and cement around them. Just as Peter reached the wall, he felt a piercing pain in his back, then another in his leg. He stumbled and then fell next to the wall.

Watching the horrific scene West Berliners, just feet away, were unable to help the dying young man who cried out in pain. Peter Fetcher's journey had ended just feet from freedom. Around the world the eyes and hearts of millions of people watched in stunned stillness as newspapers and television stations reported in fifty languages the incredible story of Peter and his desperate journey toward freedom. Millions listened to the recorded words of his friend who had escaped.

"We wanted to go to America! It was worth it to us! We would do anything! We wanted to go to America!"

What does America mean to you?

For billions of people around the world America has been, and still is, a beacon of hope – a dream that burns within their hearts. This generation has been blessed to largely inherit the freedoms we enjoy, but freedom demands a price and every generation must pay it.

Ronald Zahn

Carolyn Worssam, you mean well, and I wish you well, but Article V provides for two ways of amending the Constitution, which the Founders knew would be necessary from time to time. First, Congress may itself propose amendments. Secondly, since Congress itself would likely be the cause of the need for amendments, the states were empowered to take action. It would have been folly for the Founders to provide for two ways for Congress to enact amendments while leaving the states helpless in the matter. All the commas and periods support this view, that either Congress OR the states can take action. No, Congress cannot block the will of the states in this matter, the very states which authorized the existence of Congress in the first place.

Carolyn Worssam

To those who want a Convention of States and Term Limits:

Please read Article V of the Federalist papers with all its commas and periods. You are being fooled!! Once a Convention is called by Congress the States have no authority and given We The People have huge numbers of Communists in our Congress, both Republican and Democrats they will destroy our Constitution and take away all of our RIGHTS. You Sir, are advocating for the destruction of our Constitution. As for Term Limits: We The People have the ability to exercise instill term limits without Congress passing another law (if they will) that they will not obey. OUR VOTES ARE TERM LIMITS. We have allowed all the evil to come about. We do not vett those running for office period and we have turned our backs on GOD.

Charlie Chapman

Bob Walker , you need to go back to second grade and learn to spell. Get off your high horse and get on the ground with We The People. Trump can’t save us by himself, we will have to stand up and fight with him.

Susan Buelow

As a former educated, I continue to be appalled at what is happening in the public schools and colleges. We must not erase our history! “Who we are is who we were.” -John Quincy Adams

Seth Bradford Wagenman

Please join the Convention of States movement to put the federal government back in its proper place:

http://conventionofstates.com/?ref=38526

Leave a comment

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

Quick links

Getting started.

Learn about the greatest political success story in the world. As a citizens of the United States, you are part of that story. Click here to begin.

Follow us on

© 2024, National Center for Constitutional Studies Powered by Shopify

Let customers speak for us

I give it to people everyday...

Thanks for getting the Pocket Constitutions out very quickly.

I ordered this after reading the the book. I do a lot of driving and like to listen to these ty[es of books. This is a high quality audio in an easy to use format. transferred easily over to my phone. and the file structure is also easy to access. HIGHLY RECOMENDED

We hand these out at all of our presentations and mail them to new contacts

The Veterans organizations have been handing these out to the community when we have events. Everyone is amazed to have received one!

What Does It Mean To Be an American Essay, with Outline

Published by gudwriter on January 4, 2021 January 4, 2021

Do you have a paper due tomorrow and don’t understand all the requirements given? Our world history homework help is here to ensure you receive a quality paper within the deadline given and at an affordable price. Below is; what does it mean to be an American essay with an outline.

Elevate Your Writing with Our Free Writing Tools!

Did you know that we provide a free essay and speech generator, plagiarism checker, summarizer, paraphraser, and other writing tools for free?

What does it Mean to be an American Essay Outline

Introduction

Being an American means enjoying the right to freedom of speech, embracing diversity, embracing the American way of life, and having equal rights of determining the country’s leadership.

Paragraph 1:

An American is free to speak their mind because of the right to freedom of speech.

- This freedom makes it easy for American citizens to serve their country.

- The stand up for what is just and right.

- Free speech is based on the country’s creed which encompasses peace, freedom, and security.

Paragraph 2:

Being an American means one is part of one of the most diverse cultures in the world.

- In the U.S., nationality may not possibly be defined by religion, ancestry, or race.

- The country has many different religions and cultures.

- Rather than religion, race, or ancestry, Americans are defined by their unique social, economic, and political values.

Paragraph 3:

Being an American means leading the American way of life .

- This way of life emanated from the system of the limited government and personal liberty.

- It is rooted in the traditions of equal justice to all, respect for the rule of law, merit-based achievement, freedom of contract, private property, entrepreneurism, personal responsibility, and self-reliance.

Paragraph 4:

Americans have equal rights of determining the political leadership of the country.

- Citizens elect leaders from state legislators, Congress members, to the president.

- Even the president is just a representative of the people.

- Bills passed by state legislators and Congressmen and women should be ones geared towards bettering the life of the common American.

Paragraph 5:

Some people may argue that a true American should profess the Christian faith.

- This is an argument that is majorly fronted by members of Native American communities who are largely Christian.

- America should be open to everyone who believes in the American spirit of hard work and lives by American ideals.

- An American knows that they are free to speak freely and that they live in a diverse-cultured country with a certain way of life.

- It means being in a position to determine who leads in whatever position in the country.

- An American is entitled to economic and social rights.

- Americans should resist at all costs anyone who might try to interfere with their freedoms and rights.

Insights on what makes you unique essay with examples.

What is an American Essay

What it means to be an American goes beyond the legal definition of an American citizen. According to Philip Gleason , a renowned historian, a person did not have to be of any particular ethnic background, religion, language, or nationality in order to become or be an American. All one had to do was to live by the political ideology pegged on the abstract ideals of republicanism, equality, and liberty. American nationality was based on a Universalist ideological character which meant that anyone who willed to become an American was free to do so. One must act as an American to be an American by for instance paying taxes, voting in elections, and serving their country at home or abroad. Thus, being an American means enjoying the right to freedom of speech, embracing diversity, embracing the American way of life, and having equal rights of determining the country’s leadership.

As an American, one is free to speak their mind because of the right to freedom of speech. This freedom makes it easy for American citizens to serve their country by standing up for what is just and right. In this spirit, it would be better and greater for an American to say a “no” from their inner conviction than say a “yes” to please anyone or worse off, to avoid getting into trouble. Free speech in America is based on the country’s creed which encompasses peace, freedom, and security. It also means that Americans have the opportunity to come together and overcome their challenges by finding befitting solutions, a possibility that might not be achievable in other countries. That is why as pointed out by Grant (2012), the freedom to worship God in different religions and communities is a great source of pride and does not undermine the oneness of Americans.

Order Now We will write a custom essay on what it means to be an American written according to your requirements. From only $16 $12/page

Being an American also means one is part of one of the most diverse, if not the most diverse, cultures in the world. The United States is one of the very few world countries where nationality may not possibly be defined by religion, ancestry, or race. It is a melting pot of many different religions and cultures and it is near impossible to come across anyone whose ancestral roots are not tied to immigrant bloodlines from Africa and Europe (Grant, 2012). Rather than religion, race, or ancestry, Americans are defined by their unique social, economic, and political values. The Great Seal of the United States which reads “E pluribus unum” further drives home the fact that Americans are from all manners of backgrounds. In English, this translates to “From many, one” implying that one may even become and American without being born in the country as long as they embrace what the country stands for.

Third, being an American means leading the American way of life. This way of life emanated from the system of the limited government and personal liberty enshrined in the Constitution as well as the ideals proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. It is also rooted in the traditions of equal justice to all, respect for the rule of law, merit-based achievement, freedom of contract, private property, entrepreneurism, personal responsibility, and self-reliance (Raymond, 2014). However, with these freedoms also comes the need for deliberation whereby people must listen to and understand one another. In addition, they need to have the will to moderate their claims with a view to achieving a common ground especially when it comes to making political decisions. With a sense of solidarity, Americans can show one another mutual respect and sympathy which in turn cultivates common good for all.

Further, Americans have equal rights of determining the political leaders in whose hands the governance of the country rests. Every citizen has one vote and has the responsibility of casting it every four years in order to choose their leaders (Grant, 2008). This involves the election of leaders from state legislators, Congress members, to the president. As such, even the president is just a representative of the great people of the United States and any decisions he makes pertaining the presidency should be for the good of all. Similarly, bills passed by state legislators and Congressmen and women should be ones geared towards bettering the life of the common American. This is because they represent the interests of the electorate from whom they get the power to legislate.

Some people may bring in the issue of religion into being an American and argue that a true American should profess the Christian faith. In a certain survey, one quarter of the respondents indicated that one factor essential to being an American is being Christian (Elfenbein & Hanson, 2019). However, this is an argument that is majorly fronted by members of Native American communities who are largely Christian. What they forget is that they too were not U.S. citizens until in 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act was adopted (Elfenbein & Hanson, 2019). America should be open to everyone who believes in the American spirit of hard work, lives by American ideals as provided for in the Constitution, and vehemently fights for the country’s flag, regardless of their religious affiliation.

To be an American is to be someone who knows that they are free to speak freely and that they live in a diverse-cultured country with a certain way of life. It means being in a position to determine who leads in whatever position in the country. An American has the opportunity to achieve upward economic mobility and cherishes freedom from slavery, freedom to fight for America, and freedom of speech. These ideals were established by the country’s Constitution and are rooted in its Declaration of Independence. No one can take them away from Americans or replace them with oppressive ones because they are the very pillars that distinguish America from other countries. It implies that Americans should resist at all costs anyone who might try to interfere with their freedoms and rights.

Elfenbein, C., & Hanson, P. (2019). “What does it mean to be a ‘real’ American?”. The Washington Post . Retrieved June 16, 2020 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/01/03/what-does-it-mean-be-real-american/

Grant, J. A. (2008). The new American social compact: rights and responsibilities in the twenty-first century . Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Grant, S. (2012). A concise history of the United States of America . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, T. (2014). Rights and responsibilities of citizens: first grade social science lesson, activities, discussion questions and quizzes. HomeSchool Brew Press .

Get a free quote from our professional essay writing service and an idea of how much the paper will cost before it even begins. If the price is satisfactory, accept the bid and watch your concerns slowly fade away! Try our automatic essay generator to get quality and plagiarism free essays fast.

Special offer! Get 20% discount on your first order. Promo code: SAVE20

Related Posts

Free essays and research papers, artificial intelligence argumentative essay – with outline.

Artificial Intelligence Argumentative Essay Outline In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become one of the rapidly developing fields and as its capabilities continue to expand, its potential impact on society has become a topic Read more…

Synthesis Essay Example – With Outline

The goal of a synthesis paper is to show that you can handle in-depth research, dissect complex ideas, and present the arguments. Most college or university students have a hard time writing a synthesis essay, Read more…

Examples of Spatial Order – With Outline

A spatial order is an organizational style that helps in the presentation of ideas or things as is in their locations. Most students struggle to understand the meaning of spatial order in writing and have Read more…

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

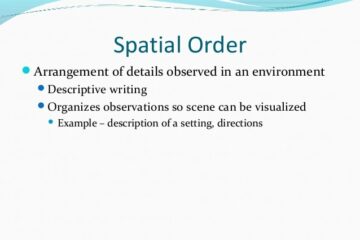

What Makes a Great American Essay?

Talking to phillip lopate about thwarted expectations, emerson, and the 21st-century essay boom.

Phillip Lopate spoke to Literary Hub about the new anthology he has edited, The Glorious American Essay . He recounts his own development from an “unpatriotic” young man to someone, later in life, who would embrace such writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who personified the simultaneous darkness and optimism underlying the history of the United States. Lopate looks back to the Puritans and forward to writers like Wesley Yang and Jia Tolentino. What is the next face of the essay form?

Literary Hub: We’re at a point, politically speaking, when disagreements about the meaning of the word “American” are particularly vehement. What does the term mean to you in 2020? How has your understanding of the word evolved?

Phillip Lopate : First of all, I am fully aware that even using the word “American” to refer only to the United States is something of an insult to Latin American countries, and if I had said “North American” to signify the US, that might have offended Canadians. Still, I went ahead and put “American” in the title as a synonym for the United States, because I wanted to invoke that powerful positive myth of America as an idea, a democratic aspiration for the world, as well as an imperialist juggernaut replete with many unresolved social inequities, in negative terms.

I will admit that when I was younger, I tended to be very unpatriotic and critical of my country, although once I started to travel abroad and witness authoritarian regimes like Spain under Franco, I could never sign on to the fear that a fascist US was just around the corner. I came to the conclusion that we have our faults, but our virtues as well.

The more I’ve become interested in American history, the more I’ve seen how today’s problems and possible solutions are nothing new, but keep returning in cycles: economic booms and recessions, anti-immigrant sentiment, regional competition, racist Jim Crow policies followed by human rights advances, vigorous federal regulations and pendulum swings away from governmental intervention.

Part of the thrill in putting together this anthology was to see it operating simultaneously on two tracks: first, it would record the development of a literary form that I loved, the essay, as it evolved over 400 years in this country. At the same time, it would be a running account of the history of the United States, in the hands of these essayists who were contending, directly or indirectly, with the pressing problems of their day. The promise of America was always being weighed against its failure to live up to that standard.

For instance, we have the educator John Dewey arguing for a more democratic schoolhouse, the founder of the settlement house movement Jane Addams analyzing the alienation of young people in big cities, the progressive writer Randolph Bourne describing his own harsh experiences as a disabled person, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton advocating for women’s rights, and W. E. B. Dubois and James Weldon Johnson eloquently addressing racial injustice.

Issues of identity, gender and intersectionality were explored by writers such as Richard Rodriguez, Audre Lorde, Leonard Michaels and N. Scott Momaday, sometimes with touches of irony and self-scrutiny, which have always been assets of the essay form.

LH : If a publisher had asked us to compile an anthology of 100 representative American essays, we wouldn’t know where to start. How did you? What were your criteria?

PL : I thought I knew the field fairly well to begin with, having edited the best-selling Art of the Personal Essay in 1994, taught the form for decades, served on book award juries and so on. But once I started researching and collecting material, I discovered that I had lots of gaps, partly because the mandate I had set for myself was so sweeping.

This time I would not restrict myself to personal essays but would include critical essays, impersonal essays, speeches that were in essence essays (such as George Washington’s Farewell Address or Martin Luther King, Jr’s sermon on Vietnam), letters that functioned as essays (Frederick Douglass’s Letter to His Master).

I wanted to expand the notion of what is an essay, to include, for instance, polemics such as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense , or one of the Federalist Papers; newspaper columnists (Fanny Fern, Christopher Morley); humorists (James Thurber, Finley Peter Dunne, Dorothy Parker).

But it also occurred to me that fine essayists must exist in every discipline, not only literature, which sent me on a hunt that took me to cultural criticism (Clement Greenberg, Kenneth Burke), theology (Paul Tillich), food writing (M.F. K. Fisher), geography (John Brinkerhoff Jackson), nature writing (John Muir, John Burroughs, Edward Abbey), science writing (Loren Eiseley, Lewis Thomas), philosophy (George Santayana). My one consistent criterion was that the essay be lively, engaging and intelligently written. In short, I had to like it myself.

Of course I would need to include the best-known practitioners of the American essay—Emerson, Thoreau, Mencken, Baldwin, Sontag, etc.—and was happy to do so. As it turned out, most of the masters of American fiction and poetry also tried their hand successfully at essay-writing, which meant including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison. . .

But I was also eager to uncover powerful if almost forgotten voices such as John Jay Chapman, Agnes Repplier, Randolph Bourne, Mary Austin, or buried treasures such as William Dean Howells’ memoir essay of his days working in his father’s printing shop.

Finally, I wanted to show a wide variety of formal approaches, since the essay is by its very nature and nomenclature an experiment, which brought me to Gertrude Stein and Wayne Koestenbaum. Equally important, I was aided in all these searches by colleagues and friends who kept suggesting other names. For every fertile lead, probably four resulted in dead ends. Meanwhile, I was having a real learning adventure.

LH: Do you have a personal favorite among American essayists? If so, what appeals to you the most about them?

PL : I do. It’s Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was the one who cleared the ground for US essayists, in his famous piece, “The American Scholar,” which called on us to free ourselves from slavish imitation of European models and to think for ourselves. So much American thought grows out of Emerson, or is in contention with Emerson, even if that debt is sometimes unacknowledged or unconscious.

What I love about Emerson is his density of thought, and the surprising twists and turns that result from it. I can read an essay of his like “Experience” (the one I included in this anthology) a hundred times and never know where it’s going next. If it was said of Emily Dickenson that her poems made you feel like the top of your head was spinning, that’s what I feel in reading Emerson. He has a playful skepticism, a knack for thinking against himself. Each sentence starts a new rabbit of thought scampering off. He’s difficult but worth the trouble.

I once asked Susan Sontag who her favorite American essayist was, and she replied “Emerson, of course.” It’s no surprise that Nietzsche revered Emerson, as did Carlyle, and in our own time, Harold Bloom, Stanley Cavell, Richard Poirier. But here’s a confession: it took me awhile to come around to him.

I found his preacher’s manner and abstractions initially off-putting, I wasn’t sure about the character of the man who was speaking to me. Then I read his Notebooks and the mystery was cracked: suddenly I was able to follow essays such as “Circles” with pure pleasure, seeing as I could the darkness and complexity underneath the optimism.

LH: You make the interesting decision to open the anthology with an essay written in 1726, 50 years before the founding of the republic. Why?

PL : I wanted to start the anthology with the first fully-formed essayistic voices in this land, which turned out to belong to the Puritans. Regardless of the negative associations of zealous prudishness that have come to attach to the adjective “puritanical,” those American colonies founded as religious settlements were spearheaded by some remarkably learned and articulate spokespersons, whose robust prose enriched the American literary canon.

Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards were highly cultivated readers, familiar with the traditions of essay-writing, Montaigne and the English, and with the latest science, even as they inveighed against witchcraft. I will admit that it also amused me to open the book with Cotton Mather, a prescriptive, strait-is-the-gate character, and end it with Zadie Smith, who is not only bi-racial but bi-national, dividing her year between London and New York, and whose openness to self-doubt is signaled by her essay collection title, Changing My Mind .

The next group of writers I focused on were the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, and a foundational feminist, Judith Sargent Murray, who wrote the 1790 essay “On the Equality of the Sexes.” These authors, whose essays preceded, occurred during or immediately followed the founding of the republic, were in some ways the opposite of the Puritans, being for the most part Deists or secular followers of the Enlightenment.

Their attraction to reasoned argument and willingness to entertain possible objections to their points of view inspired a vigorous strand of American essay-writing. So, while we may fix the founding of the United States to a specific year, the actual culture and literature of the country book-ended that date.

LH: You end with Zadie Smith’s “Speaking in Tongues,” published in 2008. Which essay in the last 12 years would be your 101st selection?

PL : Funny you should ask. As it happens, I am currently putting the finishing touches on another anthology, this one entirely devoted to the Contemporary (i.e., 21st century) American Essay. I have been immersed in reading younger, up-and-coming writers, established mid-career writers, and some oldsters who are still going strong (Janet Malcolm, Vivian Gornick, Barry Lopez, John McPhee, for example).

It would be impossible for me to single out any one contemporary essayist, as they are all in different ways contributing to the stew, but just to name some I’ve been tracking recently: Meghan Daum, Maggie Nelson, Sloane Crosley, Eula Biss, Charles D’Ambrosio, Teju Cole, Lia Purpura, John D’Agata, Samantha Irby, Anne Carson, Alexander Chee, Aleksander Hemon, Hilton Als, Mary Cappello, Bernard Cooper, Leslie Jamison, Laura Kipnis, Rivka Galchen, Emily Fox Gordon, Darryl Pinckney, Yiyun Li, David Lazar, Lynn Freed, Ander Monson, David Shields, Rebecca Solnit, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Eileen Myles, Amy Tan, Jonathan Lethem, Chelsea Hodson, Ross Gay, Jia Tolentino, Jenny Boully, Durga Chew-Bose, Brian Blanchfield, Thomas Beller, Terry Castle, Wesley Yang, Floyd Skloot, David Sedaris. . .

Such a banquet of names speaks to the intergenerational appeal of the form. We’re going through a particularly rich time for American essays: especially compared to, 20 years ago, when editors wouldn’t even dare put the word “essays” on the cover, but kept trying to package these variegated assortments as single-theme discourses, we’ve seen many collections that have been commercially successful and attracted considerable critical attention.

It has something to do with the current moment, which has everyone more than a little confused and therefore trusting more than ever those strong individual voices that are willing to cop to their subjective fears, anxieties, doubts and ecstasies.

__________________________________

The Glorious American Essay , edited by Phillip Lopate, is available now.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Phillip Lopate

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Recent History: Lessons From Obama, Both Cautionary and Hopeful

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Department of Sociology

Meanings of Democracy Lab