- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

Should I Use “I”?

What this handout is about.

This handout is about determining when to use first person pronouns (“I”, “we,” “me,” “us,” “my,” and “our”) and personal experience in academic writing. “First person” and “personal experience” might sound like two ways of saying the same thing, but first person and personal experience can work in very different ways in your writing. You might choose to use “I” but not make any reference to your individual experiences in a particular paper. Or you might include a brief description of an experience that could help illustrate a point you’re making without ever using the word “I.” So whether or not you should use first person and personal experience are really two separate questions, both of which this handout addresses. It also offers some alternatives if you decide that either “I” or personal experience isn’t appropriate for your project. If you’ve decided that you do want to use one of them, this handout offers some ideas about how to do so effectively, because in many cases using one or the other might strengthen your writing.

Expectations about academic writing

Students often arrive at college with strict lists of writing rules in mind. Often these are rather strict lists of absolutes, including rules both stated and unstated:

- Each essay should have exactly five paragraphs.

- Don’t begin a sentence with “and” or “because.”

- Never include personal opinion.

- Never use “I” in essays.

We get these ideas primarily from teachers and other students. Often these ideas are derived from good advice but have been turned into unnecessarily strict rules in our minds. The problem is that overly strict rules about writing can prevent us, as writers, from being flexible enough to learn to adapt to the writing styles of different fields, ranging from the sciences to the humanities, and different kinds of writing projects, ranging from reviews to research.

So when it suits your purpose as a scholar, you will probably need to break some of the old rules, particularly the rules that prohibit first person pronouns and personal experience. Although there are certainly some instructors who think that these rules should be followed (so it is a good idea to ask directly), many instructors in all kinds of fields are finding reason to depart from these rules. Avoiding “I” can lead to awkwardness and vagueness, whereas using it in your writing can improve style and clarity. Using personal experience, when relevant, can add concreteness and even authority to writing that might otherwise be vague and impersonal. Because college writing situations vary widely in terms of stylistic conventions, tone, audience, and purpose, the trick is deciphering the conventions of your writing context and determining how your purpose and audience affect the way you write. The rest of this handout is devoted to strategies for figuring out when to use “I” and personal experience.

Effective uses of “I”:

In many cases, using the first person pronoun can improve your writing, by offering the following benefits:

- Assertiveness: In some cases you might wish to emphasize agency (who is doing what), as for instance if you need to point out how valuable your particular project is to an academic discipline or to claim your unique perspective or argument.

- Clarity: Because trying to avoid the first person can lead to awkward constructions and vagueness, using the first person can improve your writing style.

- Positioning yourself in the essay: In some projects, you need to explain how your research or ideas build on or depart from the work of others, in which case you’ll need to say “I,” “we,” “my,” or “our”; if you wish to claim some kind of authority on the topic, first person may help you do so.

Deciding whether “I” will help your style

Here is an example of how using the first person can make the writing clearer and more assertive:

Original example:

In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.

Better example using first person:

In our study of American popular culture of the 1980s, we explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.

The original example sounds less emphatic and direct than the revised version; using “I” allows the writers to avoid the convoluted construction of the original and clarifies who did what.

Here is an example in which alternatives to the first person would be more appropriate:

As I observed the communication styles of first-year Carolina women, I noticed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

Better example:

A study of the communication styles of first-year Carolina women revealed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

In the original example, using the first person grounds the experience heavily in the writer’s subjective, individual perspective, but the writer’s purpose is to describe a phenomenon that is in fact objective or independent of that perspective. Avoiding the first person here creates the desired impression of an observed phenomenon that could be reproduced and also creates a stronger, clearer statement.

Here’s another example in which an alternative to first person works better:

As I was reading this study of medieval village life, I noticed that social class tended to be clearly defined.

This study of medieval village life reveals that social class tended to be clearly defined.

Although you may run across instructors who find the casual style of the original example refreshing, they are probably rare. The revised version sounds more academic and renders the statement more assertive and direct.

Here’s a final example:

I think that Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.

Better example

Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.

In this example, there is no real need to announce that that statement about Aristotle is your thought; this is your paper, so readers will assume that the ideas in it are yours.

Determining whether to use “I” according to the conventions of the academic field

Which fields allow “I”?

The rules for this are changing, so it’s always best to ask your instructor if you’re not sure about using first person. But here are some general guidelines.

Sciences: In the past, scientific writers avoided the use of “I” because scientists often view the first person as interfering with the impression of objectivity and impersonality they are seeking to create. But conventions seem to be changing in some cases—for instance, when a scientific writer is describing a project she is working on or positioning that project within the existing research on the topic. Check with your science instructor to find out whether it’s o.k. to use “I” in their class.

Social Sciences: Some social scientists try to avoid “I” for the same reasons that other scientists do. But first person is becoming more commonly accepted, especially when the writer is describing their project or perspective.

Humanities: Ask your instructor whether you should use “I.” The purpose of writing in the humanities is generally to offer your own analysis of language, ideas, or a work of art. Writers in these fields tend to value assertiveness and to emphasize agency (who’s doing what), so the first person is often—but not always—appropriate. Sometimes writers use the first person in a less effective way, preceding an assertion with “I think,” “I feel,” or “I believe” as if such a phrase could replace a real defense of an argument. While your audience is generally interested in your perspective in the humanities fields, readers do expect you to fully argue, support, and illustrate your assertions. Personal belief or opinion is generally not sufficient in itself; you will need evidence of some kind to convince your reader.

Other writing situations: If you’re writing a speech, use of the first and even the second person (“you”) is generally encouraged because these personal pronouns can create a desirable sense of connection between speaker and listener and can contribute to the sense that the speaker is sincere and involved in the issue. If you’re writing a resume, though, avoid the first person; describe your experience, education, and skills without using a personal pronoun (for example, under “Experience” you might write “Volunteered as a peer counselor”).

A note on the second person “you”:

In situations where your intention is to sound conversational and friendly because it suits your purpose, as it does in this handout intended to offer helpful advice, or in a letter or speech, “you” might help to create just the sense of familiarity you’re after. But in most academic writing situations, “you” sounds overly conversational, as for instance in a claim like “when you read the poem ‘The Wasteland,’ you feel a sense of emptiness.” In this case, the “you” sounds overly conversational. The statement would read better as “The poem ‘The Wasteland’ creates a sense of emptiness.” Academic writers almost always use alternatives to the second person pronoun, such as “one,” “the reader,” or “people.”

Personal experience in academic writing

The question of whether personal experience has a place in academic writing depends on context and purpose. In papers that seek to analyze an objective principle or data as in science papers, or in papers for a field that explicitly tries to minimize the effect of the researcher’s presence such as anthropology, personal experience would probably distract from your purpose. But sometimes you might need to explicitly situate your position as researcher in relation to your subject of study. Or if your purpose is to present your individual response to a work of art, to offer examples of how an idea or theory might apply to life, or to use experience as evidence or a demonstration of an abstract principle, personal experience might have a legitimate role to play in your academic writing. Using personal experience effectively usually means keeping it in the service of your argument, as opposed to letting it become an end in itself or take over the paper.

It’s also usually best to keep your real or hypothetical stories brief, but they can strengthen arguments in need of concrete illustrations or even just a little more vitality.

Here are some examples of effective ways to incorporate personal experience in academic writing:

- Anecdotes: In some cases, brief examples of experiences you’ve had or witnessed may serve as useful illustrations of a point you’re arguing or a theory you’re evaluating. For instance, in philosophical arguments, writers often use a real or hypothetical situation to illustrate abstract ideas and principles.

- References to your own experience can explain your interest in an issue or even help to establish your authority on a topic.

- Some specific writing situations, such as application essays, explicitly call for discussion of personal experience.

Here are some suggestions about including personal experience in writing for specific fields:

Philosophy: In philosophical writing, your purpose is generally to reconstruct or evaluate an existing argument, and/or to generate your own. Sometimes, doing this effectively may involve offering a hypothetical example or an illustration. In these cases, you might find that inventing or recounting a scenario that you’ve experienced or witnessed could help demonstrate your point. Personal experience can play a very useful role in your philosophy papers, as long as you always explain to the reader how the experience is related to your argument. (See our handout on writing in philosophy for more information.)

Religion: Religion courses might seem like a place where personal experience would be welcomed. But most religion courses take a cultural, historical, or textual approach, and these generally require objectivity and impersonality. So although you probably have very strong beliefs or powerful experiences in this area that might motivate your interest in the field, they shouldn’t supplant scholarly analysis. But ask your instructor, as it is possible that they are interested in your personal experiences with religion, especially in less formal assignments such as response papers. (See our handout on writing in religious studies for more information.)

Literature, Music, Fine Arts, and Film: Writing projects in these fields can sometimes benefit from the inclusion of personal experience, as long as it isn’t tangential. For instance, your annoyance over your roommate’s habits might not add much to an analysis of “Citizen Kane.” However, if you’re writing about Ridley Scott’s treatment of relationships between women in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” some reference your own observations about these relationships might be relevant if it adds to your analysis of the film. Personal experience can be especially appropriate in a response paper, or in any kind of assignment that asks about your experience of the work as a reader or viewer. Some film and literature scholars are interested in how a film or literary text is received by different audiences, so a discussion of how a particular viewer or reader experiences or identifies with the piece would probably be appropriate. (See our handouts on writing about fiction , art history , and drama for more information.)

Women’s Studies: Women’s Studies classes tend to be taught from a feminist perspective, a perspective which is generally interested in the ways in which individuals experience gender roles. So personal experience can often serve as evidence for your analytical and argumentative papers in this field. This field is also one in which you might be asked to keep a journal, a kind of writing that requires you to apply theoretical concepts to your experiences.

History: If you’re analyzing a historical period or issue, personal experience is less likely to advance your purpose of objectivity. However, some kinds of historical scholarship do involve the exploration of personal histories. So although you might not be referencing your own experience, you might very well be discussing other people’s experiences as illustrations of their historical contexts. (See our handout on writing in history for more information.)

Sciences: Because the primary purpose is to study data and fixed principles in an objective way, personal experience is less likely to have a place in this kind of writing. Often, as in a lab report, your goal is to describe observations in such a way that a reader could duplicate the experiment, so the less extra information, the better. Of course, if you’re working in the social sciences, case studies—accounts of the personal experiences of other people—are a crucial part of your scholarship. (See our handout on writing in the sciences for more information.)

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

“I” & “We” in Academic Writing: Examples from 9,830 Studies

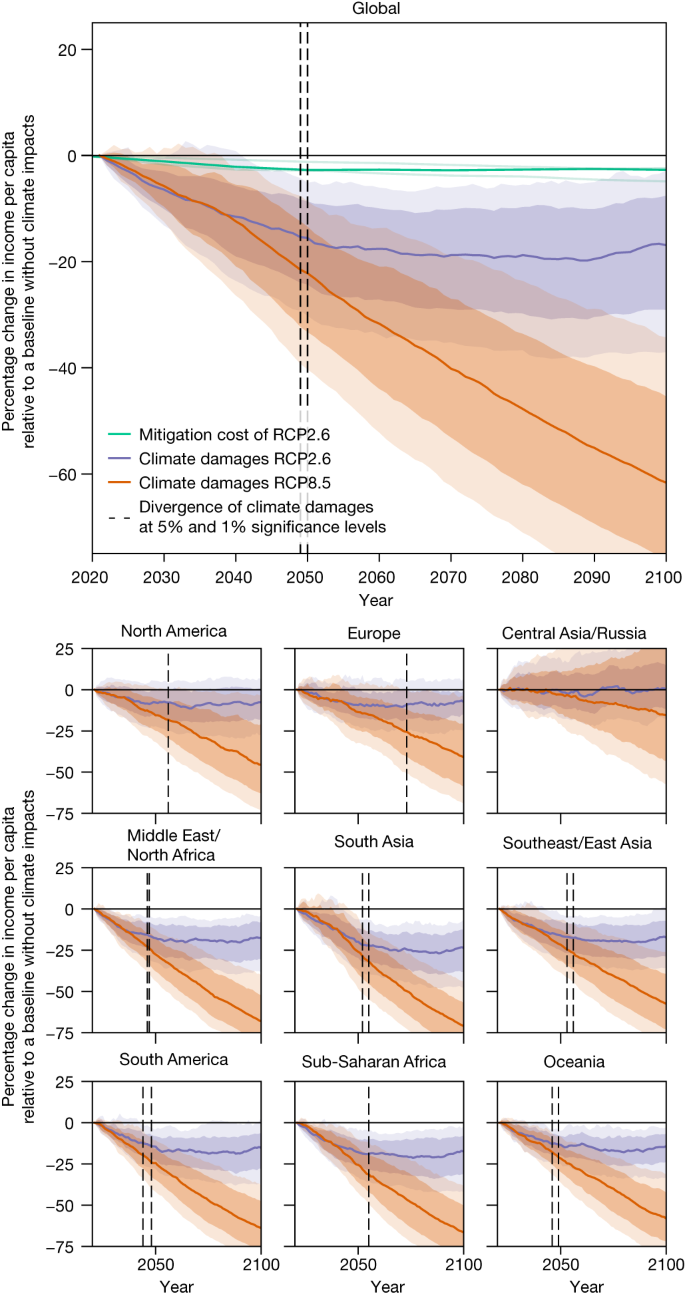

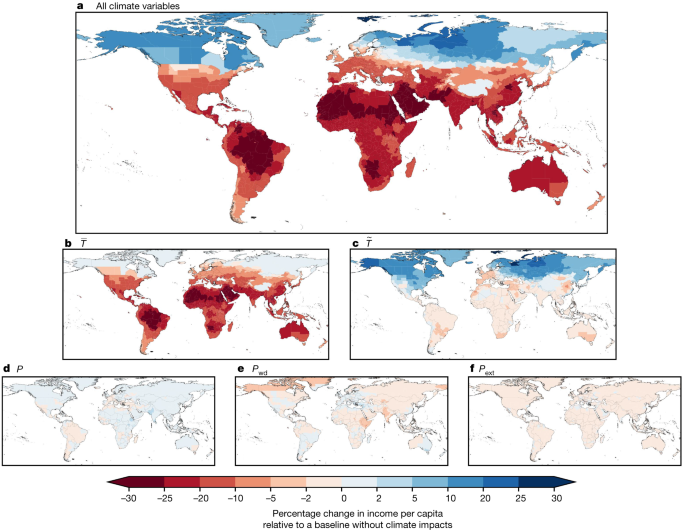

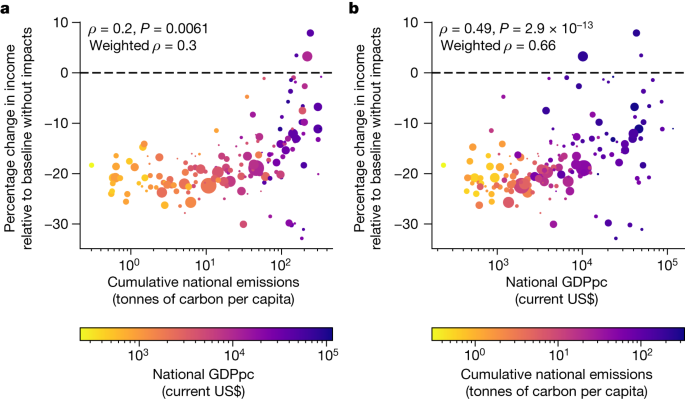

I analyzed a random sample of 9,830 full-text research papers, uploaded to PubMed Central between the years 2016 and 2021, in order to explore whether first-person pronouns are used in the scientific literature, and how?

I used the BioC API to download the data (see the References section below).

Popularity of first-person pronouns in the scientific literature

In our sample of 9,830 articles, 93.8% used the first-person pronouns “I” or “We”. The use of the pronoun “We” was a lot more prevalent than “I” (93.1% versus 13.9%, respectively).

In fact, even articles written by single authors were more likely to use “We” instead of “I”. Out of 9,830 articles, 39 were written by single authors: 8 of them used “I” and 19 used “We”.

The following table describes the use of first-person pronouns in each section of the research article:

Use of the pronoun “I”

The pronoun “I” was mostly used in the Methods section (present in 7.29% of all methods sections in our sample).

For example:

“In general, I assumed a steady-state and a closed-population.” Link to the article on PubMed

“I” was also prevalent in the Results section (6.28%). But here, all of its uses were to quote participants’ answers, such as:

The respondents stated, “ I am scared to get infected and infect my family when I go home” Link to the article on PubMed

“I” was scarcely used in the Discussion section, for example:

“Based on this observation, I suggest that future research on this population seek to increase the participation of Indigenous communities.” Link to the article on PubMed

And only 1 article of 9,830 used the pronoun “I” in the abstract:

“By using the largest publicly available cancer incidence statistics (20 million cases), I show that incidence of 20 most prevalent cancer types in relation to patients’ age closely follows the Erlang probability distribution (R 2 = 0.9734-0.9999).” Link to the article on PubMed

Use of the pronoun “We”

The pronoun “We” was primarily used in the Discussion section (in 85.65% of the cases). For example:

“Although we cannot rule out this potential bias, we expect that missing data in our analysis did not depend on our dependent variable.” Link to the article on PubMed

Followed by the Methods section (68.29%). For example:

“Depending on the severity and chronicity of disease, we applied three different time frames” Link to the article on PubMed

Then followed by the Introduction (64.31%). For example:

“Instead of using time series analysis, we conducted a manipulative field experiment.” Link to the article on PubMed

“We” is used to a lesser extent in the Results section (52.36%). For example:

“In contrast, we did not find differences in survival when mutants where challenged with acute oxidative stress (Figure S5)” Link to the article on PubMed

And a lot less in the Abstract. For example:

“In this study, we analyzed and summarized seven RCTs and four meta-analyses.” Link to the article on PubMed

Article quality and the use first-person pronouns

The following table compares articles that used first-person pronouns with those that did not use first-person pronouns regarding:

- The number of citations per year received by these articles

- The impact factor of the journals in which these articles were published

The data show that higher-quality articles (those that bring more citations and those published in high-impact journals) tend to use first-person pronouns.

In other words, high article quality is correlated with the use of first-person pronouns.

- Comeau DC, Wei CH, Islamaj Doğan R, and Lu Z. PMC text mining subset in BioC: about 3 million full text articles and growing, Bioinformatics , btz070, 2019.

Further reading

- Paragraph Length: Data from 9,830 Research Papers

- Can a Research Title Be a Question? Real-World Examples

- How Long Should a Research Paper Be? Data from 61,519 Examples

- How Many References to Cite? Based on 96,685 Research Papers

- How Old Should References Be? Based on 3,823,919 Examples

Using “I” in Academic Writing

Traditionally, some fields have frowned on the use of the first-person singular in an academic essay and others have encouraged that use, and both the frowning and the encouraging persist today—and there are good reasons for both positions (see “Should I”).

I recommend that you not look on the question of using “I” in an academic paper as a matter of a rule to follow, as part of a political agenda (see webb), or even as the need to create a strategy to avoid falling into Scylla-or-Charybdis error. Let the first-person singular be, instead, a tool that you take out when you think it’s needed and that you leave in the toolbox when you think it’s not.

Examples of When “I” May Be Needed

- You are narrating how you made a discovery, and the process of your discovering is important or at the very least entertaining.

- You are describing how you teach something and how your students have responded or respond.

- You disagree with another scholar and want to stress that you are not waving the banner of absolute truth.

- You need “I” for rhetorical effect, to be clear, simple, or direct.

Examples of When “I” Should Be Given a Rest

- It’s off-putting to readers, generally, when “I” appears too often. You may not feel one bit modest, but remember the advice of Benjamin Franklin, still excellent, on the wisdom of preserving the semblance of modesty when your purpose is to convince others.

- You are the author of your paper, so if an opinion is expressed in it, it is usually clear that this opinion is yours. You don’t have to add a phrase like, “I believe” or “it seems to me.”

Works Cited

Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin . Project Gutenberg , 28 Dec. 2006, www.gutenberg.org/app/uploads/sites/3/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm#I.

“Should I Use “I”?” The Writing Center at UNC—Chapel Hill , writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/should-i-use-i/.

webb, Christine. “The Use of the First Person in Academic Writing: Objectivity, Language, and Gatekeeping.” ResearchGate , July 1992, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01974.x.

J.S.Beniwal 05 August 2017 AT 09:08 AM

I have borrowed MLA only yesterday, did my MAEnglish in May 2017.MLA is of immense help for scholars.An overview of the book really enlightened me.I should have read it at bachelor's degree level.

Your e-mail address will not be published

Dr. Raymond Harter 25 September 2017 AT 02:09 PM

I discourage the use of "I" in essays for undergraduates to reinforce a conversational tone and to "self-recognize" the writer as an authority or at least a thorough researcher. Writing a play is different than an essay with a purpose.

Osayimwense Osa 22 March 2023 AT 05:03 PM

When a student or writer is strongly and passionately interested in his or her stance and argument to persuade his or her audience, the use of personal pronoun srenghtens his or her passion for the subject. This passion should be clear in his/her expression. However, I encourage the use of the first-person, I, sparingly -- only when and where absolutely necessary.

Eleanor 25 March 2023 AT 04:03 PM

I once had a student use the word "eye" when writing about how to use pronouns. Her peers did not catch it. I made comments, but I think she never understood what eye was saying!

Join the Conversation

We invite you to comment on this post and exchange ideas with other site visitors. Comments are moderated and subject to terms of service.

If you have a question for the MLA's editors, submit it to Ask the MLA!

Monday, April 22, 2024

- Are first-person pronouns acceptable in scientific writing?

February 23, 2011 Filed under Blog , Featured , Popular , Writing

Interestingly, this rule seems to have originated with Francis Bacon to give scientific writing more objectivity.

In Eloquent Science (pp. 76-77), I advocate that first-person pronouns are acceptable in limited contexts. Avoid their use in rote descriptions of your methodology (“We performed the assay…”). Instead, use them to communicate that an action or a decision that you performed affects the outcome of the research.

NO FIRST-PERSON PRONOUN: Given option A and option B, the authors chose option B to more accurately depict the location of the front. FIRST-PERSON PRONOUN: Given option A and option B, we chose option B to more accurately depict the location of the front.

So, what do other authors think? I have over 30 books on scientific writing and have read numerous articles on this point. Here are some quotes from those who expressed their opinion on this matter and I was able to find from the index of the book or through a quick scan of the book.

“Because of this [avoiding first-person pronouns], the scientist commonly uses verbose (and imprecise) statements such as “It was found that” in preference to the short, unambiguous “I found.” Young scientists should renounce the false modesty of their predecessors. Do not be afraid to name the agent of the action in a sentence, even when it is “I” or “we.”” — How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper by Day and Gastel, pp. 193-194 “Who is the universal ‘it’, the one who hides so bashfully, but does much thinking and assuming? “ It is thought that … is a meaningless phrase and unnecessary exercise in modesty. The reader wants to know who did the thinking or assuming, the author, or some other expert.” — The Science Editor’s Soapbox by Lipton, p. 43 “I pulled 40 journals at random from one of my university’s technical library’s shelves…. To my surprise, in 32 out of the 40 journals, the authors indeed made liberal use of “I” and “we.” — Style for Students by Joe Schall, p. 63 “Einstein occasionally used the first person. He was not only a great scientist, but a great scientific writer. Feynman also used the first person on occasion, as did Curie, Darwin, Lyell, and Freud. As long as the emphasis remains on your work and not you, there is nothing wrong with judicious use of the first person.” — The Craft of Scientific Writing by Michael Alley, p. 107 “One of the most epochal papers in all of 20th-century science, Watson and Crick’s article defies nearly every major rule you are likely to find in manuals on scientific writing…. There is the frequent use of “we”…. This provides an immediate human presence, allowing for constant use of active voice. It also gives the impression that the authors are telling us their actual thought processes.” — The Chicago Guide to Communicating Science by Scott L. Montgomery, p. 18 “We believe in the value of a long tradition (which some deplore) arguing that it is inappropriate for the author of a scientific document to refer to himself or herself directly, in the first person…. There is no place for the subjectivity implicit in personal intrusion on the part of the one who conducted the research—especially since the section is explicitly labeled “Results”…. If first-person pronouns are appropriate anywhere in a dissertation, it would be in the Discussion section…because different people might indeed draw different inferences from a given set of facts.” — The Art of Scientific Writing by Ebel et al., p. 79. [After arguing for two pages on clearly explaining why the first person should not be used…] “The first person singular is appropriate when the personal element is strong, for example, when taking a position in a controversy. But this tends to weaken the writer’s credibility. The writer usually wants to make clear that anyone considering the same evidence would take the same position. Using the third person helps to express the logical impersonal character and generality of an author’s position, whereas the first person makes it seem more like personal opinion.” — The Scientist’s Handbook for Writing Papers and Dissertations by Antoinette Wilkinson, p. 76.

So, I can find only one source on my bookshelf advocating against use of the first-person pronouns in all situations (Wilkinson). Even the Ebel et al. quote I largely agree with.

Thus, first-person pronouns in scientific writing are acceptable if used in a limited fashion and to enhance clarity.

Isn’t it telling that Ebel et al begin their argument against usage of the first person with the phrase ““We believe …”?

That is a reall good point, Kirk. Thanks for pointing that out!

This argument is approximately correct, but in my opinion off point. The use of first person should always be minimized in scientific writing, but not because it is unacceptable or even uncommon. It should be minimized because it is ineffective, and it is usually badly so. Specifically, the purpose of scientific writing is to create a convincing argument based on data collected during the evaluation of a hypothesis. This is basic scientific method. The strength of this argument depends on the data, not on the person who collected it. Using first person deemphasises the data, which weakens the argument and opens the door for subjective criticism to be used to rebut what should be objective data. For example, suppose I hypothesized that the sun always rises in the east, and I make daily observations over the course of a year to support that hypothesis. I could say, “I have shown that the sun always rises in the east”. A critic might respond by simply saying that I am crazy, and that I got it wrong. In other words, it can easily become an argument about “me”. However, if I said “Daily observations over the course of a year showed that the sun always rises in the east”, then any subsequent argument must rebut the data and not rebut “me”. Actually, I would never say this using either of those formulations. I would say, “Daily observations over the course of a year were consistent with the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east.” This is basic scientific expository writing.

Finally, if one of my students EVER wrote “it was found that …”, I would hit him or her over the head with a very large stick. That is just as bad as “I found that …”, and importantly, those are NOT the only two options. The correct way to say this in scientific writing is, “the data showed that …”.

In general, I agree with you. We should omit ourselves from our science to emphasize what the data demonstrate.

My only qualification is that, as scientists, the collection, observation, and interpretation of data is difficult to disconnect from its human aspects. Being a human endeavor, science is necessarily affected by the humans themselves who do the work.

Thanks for your comment!

i could not understand why 1st person I is used with plural verb

Not sure that I completely understand your question, but grammatically “I” should only be used with a singular verb. If you use “I” in scientific writing, only do so with single-authored papers.

Does that answer your question?

why do we use ‘have’ with ‘i’ pronoun?

I wouldn’t view it as “I” goes with the plural verb “have”, but that “have” can be used with a number of different persons, regardless of whether it is singular or plural.

First person singular: “I have” Second person singular: “You have” Third person singular: “He/She/It has”

First person plural: “We have” Second person plural: “All of you have” Third person plural: “They have”

I know it perhaps doesn’t make sense, but that is the way English works.

I hope that helps.

I think there are a few cases where personal pronouns would be acceptable. If you are introducing a new section in a thesis or even an article, you might want to say “we begin with a description of the data in section 2” etc, rather than the cumbersome “this paper will begin with …”. Also in discussions of future work, it would make sense to say “we intend to explore X, Y and Z”.

I loved reading this, my Prof. and I were debating about this. He wants me to say “I analyzed” and I want to say “problem notification database analysed revealed that…”

I’m writing a paper for a conference. I wonder if I can defy a Professor in Korea:)

I disagree that writing in the 3rd person makes writing more objective. I also disagree that it “opens the door for subjective criticism to be used to rebut what should be objective data”. In fact, using the 3rd person obstructs reality. There are people behind the research who both make mistakes and do great things. It is no less true for science than it is for other subjects that 3rd person obstructs the author of an action and makes the idea being conveyed less clear. I find it odd that scientific writing guides instruct authors to BOTH use active voice AND use only the 3rd person. It is impossible to do both. Active voice means that there is a subject, a strong verb (not a version of the verb “to be”) and an object. When I say “The solution was mixed”, it is BOTH 3rd person and passive voice. The only way to construct that sentence without passive voice is to say “We mixed the solution”. Honestly, after spending most of the first part of my life in English classes and then transitioning to science, I find most scientific writing an abomonination.

Hi Kathleen,

I think it is great that you have had your feet in both English and science. For many of us who have struggled as writers, those people are great role models to aspire to.

An anecdote: my wife’s research student turned in a brief report on his work to date. She was showing me how well written his work was, really pretty advanced for an undergrad physics student. Later, she found out that he was trying to decide between majoring in physics and majoring in English.

Hi David. Thanks very much for your tips. Very interesting article. Did you just tweet that you should keep “I” and “We” out of the abstract? I am translating a psychology article from Spanish into English, and I’ve come up against an unwieldly sentence (the very last one in the abstract) that basically wants to say “We propose a number of strategies for improving the impact of the psychological treatments[…]” Would you say it’s a no-no? I tend to avoid personal pronouns in academic articles as much as poss, but it just sounds like the most natural option in this case. Perhaps I could put, “This article proposes a number of treatments…”? Strictly speaking it’s not the article that’s doing the proposing, obviously. I’d be very grateful to have your opinion. Thanks a lot. Best regards. Louisa

Yes, it’s difficult. How about going passive? “A number of treatments are proposed….”?

The comments against using first person, which are rampant in science education, are silly. Go read Nature or Science. I believe Kathleen makes a fantastic point.

Just happened across this blog while searching for something else, and procrastination rules, ok?

My pet hate is lecturers who uncritically criticise students for using the third person. Close behind is institutional guidance/insistence on third person ‘scientific writing’. Both are hugely ironic, the first because it is typically uncritical and purely traditional (we are employed to teach others to be critical and challenge tradition), the second because there is so little empirical evidence to suggest that the scientific method is third person.

I very much appreciated Bill Lott’s response because a) it was critical and b) it discussed the issue of good and bad writing as opposed to first and third person. However I would still suggest that the way he would report his exemplar data is all but first person:

“Daily observations over the course of a year were consistent with the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east.”

Who did the observations if not the first person? All that is missing is My or Our at the beginning of the sentence and hey presto

Another facet of writing is that it disappears if not frequently watered and tended to.

Even though this is an old article, I’d like to add my 2c to the thread.

I think the use of the 3rd person is pompous, verbose and obtuse – it uses many words to say the same thing in a flowery way.

“It is the opinion of the author that” as opposed to “I think that”

Anybody reading the article knows that it’s written by a person / persons who did the research on the topic, who are either presenting their findings or opinion. The whole 3rd person thing seems to be a game, and I for one, HATE writing about myself in the 3rd person.

That being said, it seems to be the convention that the 3rd person is used, and I probably will write my paper in the 3rd person anyway, just to not rock the boat.

But I wish that the pomposity would stop and we would get more advocates for writing in plain English.

Hi, i was wondering… can “We” be said in a scientific school report?

Depends on the context, I guess. I would follow the same advice as above.

Thanks for all the tips. Don’t forget that in the future historians are going to want to know who did what and when. Scientists may not think it important, but historians will (especially if it is a significant contribution). Furthermore, by not revealing particulars regarding individual contributions opens the door for many scientists to falsify the historical record in their favor (I have experienced this first hand in a recent publication).

i think it is soo weird to use first person in reports…….third persons will be more effective when used and that will give a clear explanations to the audience

Even Nature journals are encouraging “we” in the manuscript.

“Nature journals prefer authors to write in the active voice (“we performed the experiment…”) as experience has shown that readers find concepts and results to be conveyed more clearly if written directly.”

https://www.nature.com/authors/author_resources/how_write.html

[…] Is trouwens iets dat blijkbaar al lang voor discussies zorgt, als je deze links bekijkt: Are first-person pronouns acceptable in scientific writing? : eloquentscience.com Use of the word "I" in scientific papers Zelfs wikipedia heeft er een artikel over: […]

[…] There was some discussion on Twitter about whether or not to write in the 1st person. The Lab & Field pointed out that Francis Bacon may have been responsible for the movement to avoid it in scientific writing… […]

[…] ¿Son aceptables los pronombres en primera persona en publicaciones científicas? [ENG] […]

[…] do discuss this among themselves. For example, see Yateendra Joshi and Professor David M. Schultz. Professor Schultz notes that the use of the first person in science appears to be as common among […]

[…] http://eloquentscience.com/2011/02/are-first-person-pronouns-acceptable-in-scientific-writing/ […]

[…] There’s no rule about the passive voice in science. People seem to think that it’s “scientific” writing, but it isn’t. It’s just bad writing. There’s actually no rule against first person pronouns either! Read this for more on the use of the first-person in scientific writing. […]

To order, visit:

The American Meteorological Society (preferred)

The University of Chicago Press

eNews & Updates

Sign up to receive breaking news as well as receive other site updates!

David M. Schultz is a Professor of Synoptic Meteorology at the Centre for Atmospheric Science, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, and the Centre for Crisis Studies and Mitigation, The University of Manchester. He served as Chief Editor for Monthly Weather Review from 2008 to 2022. In 2014 and 2017, he received the University of Manchester Teaching Excellence Award, the only academic to have twice done so. He has published over 190 peer-reviewed journal articles. [Read more]

- Search for:

Latest Tweets

currently unavailable

Recent Posts

- Free Writing and Publishing Online Workshop: 19–20 June 2024

- Editorial: How to Be a More Effective Author

- How to be a more effective reviewer

- The Five Most Common Problems with Introductions

- Eliminate excessive and unnecessary acronyms from your scientific writing

- Chinese translation of Eloquent Science now available

- How Bill Paxton Helped Us Understand Tornadoes in Europe

- Publishing Academic Papers Workshop

- Past or Present Tense?

- Rejected for publication: What now?

- Thermodynamic diagrams for free

- Do you end with a ‘thank you’ or ‘questions?’ slide?

- Presentations

Copyright © 2024 EloquentScience.com · All Rights Reserved · StudioPress theme customized by Insojourn Design · Log in

Pronoun Usage in Academic Writing: ‘I,’ ‘We,’ and ‘They’

- By Zain Ul Abadin

- No Comments

Introduction:

Welcome to a comprehensive exploration of pronoun usage in academic writing. This article serves as your indispensable guide to understanding the judicious use of ‘I,’ ‘We,’ and ‘They’ in research papers. Whether you are a novice researcher seeking guidance or an experienced scholar aiming to refine your skills, this guide empowers you to articulate your ideas with scholarly finesse. By the time you’ve journeyed through these pages, you will have the tools to strike a harmonious balance between academic rigor and engaging prose.

1. The Significance of Pronouns in Academic Writing

Pronouns are the unsung heroes of academic writing. They link concepts, reinforce clarity, and create a cohesive narrative in your research. The strategic deployment of pronouns plays a pivotal role in shaping your text, influencing the reader’s understanding, and maintaining the language of research. As we delve deeper, you’ll discover the profound impact pronouns have on readability, coherence, and the overall quality of your academic work.

2. Pronoun Usage in Academic Writing:

Here we arrive at the heart of the matter: understanding when and how to utilize ‘I,’ ‘We,’ and ‘They’ within the context of research papers. Each of these pronouns has its unique strengths, and a thorough understanding of their application is key to scholarly success.

3. Language of Research: Formality and Precision:

In the world of academic writing, precision and formality are non-negotiable. The language of research demands utmost clarity, and even the smallest nuances in expression matter. In this section, we explore the significance of maintaining a formal tone, ensuring that your academic work radiates professionalism.

4. When to Use ‘I’ in Research Papers

Expressing personal experience:.

The ‘I’ pronoun can be a powerful tool for infusing your research paper with your own experiences, insights, and observations. Personalizing your work not only connects you with your readers but also adds authenticity to your writing. We encourage you to provide specific examples from your journey, as well as your interpretations of research findings. When used effectively, ‘I’ offers a human touch to the language of research.

Presenting Research Findings:

When presenting your research findings, ‘I’ allows you to assert your authorship and authority. By choosing ‘I,’ you emphasize that you are the architect of your research, the analyst of your data, and the interpreter of your findings. This section helps you balance the use of ‘I’ to maintain a professional tone in presenting your research.

5. ‘We’ in Research Papers: Dos and Don’ts

Collaborative research:.

Collaborative research projects often call for the use of ‘We’ to denote shared responsibility and contributions. Clearly defining roles, acknowledging teamwork, and underlining collective efforts can help you leverage the power of ‘We’ to enhance credibility and trustworthiness in your academic work.

Overuse and Its Consequences:

However, overusing ‘We’ can detract from your paper’s formality and professionalism. To avoid this, you can balance ‘We’ with passive voice or opt for a rephrasing when it feels excessive. Evaluating the necessity of ‘We’ in specific contexts is also key to maintaining a formal tone.

6. The Inclusive ‘They’

In the modern academic landscape, inclusivity is of utmost importance. ‘They’ serves as a gender-neutral pronoun, promoting diversity and accommodating those who identify beyond the gender binary. This section unpacks the significance of ‘They’ and offers strategies for using it effectively to create an inclusive academic environment .

7. Can You Use ‘We’ in a Research Paper?

Is it Okay to Use ‘We’?

This section addresses the age-old question of whether it is permissible to use ‘We’ in research papers. We explore the nuances of its acceptability, shedding light on when and how it can be appropriately incorporated.

Collaborative Research and ‘We’:

For collaborative research, ‘We’ is often indispensable. We delve into the dynamics of collaborative work and provide guidance on using ‘We’ effectively in such contexts.

8. Can You Use ‘I’ in Research Papers?

Personal perspective in research:.

Unleash the power of ‘I’ to express your personal viewpoints, experiences, and insights in a scholarly and professional manner. This section offers a balanced approach to using ‘I’ effectively without veering into informality.

Striking a Balance:

Striking a balance is the key to maintaining a professional tone. This section helps you navigate the fine line between personal engagement and scholarly authority.

9. Is It Okay to Use ‘They’ in Research Papers?

Embracing gender neutrality:.

Explore the significance of using ‘They’ as a gender-neutral pronoun to foster inclusivity and create a scholarly environment that respects diverse identities.

Practical Application:

This section provides practical guidance on how to incorporate ‘They’ effectively while avoiding potential pitfalls and misconceptions in your research.

10. Language of Research: A Summary

A concise summary of the key takeaways on maintaining a formal, precise, and professional language in academic writing.

11. Conclusion

In this comprehensive guide, we have journeyed through the labyrinth of pronoun usage in academic writing, whether it’s ‘I,’ ‘We,’ or ‘They.’ Armed with the knowledge and strategies presented here, you are equipped to navigate this intricate terrain with confidence and precision. Precision and professionalism remain the watchwords of the language of research, and your mastery of pronouns is a vital step toward achieving excellence in academic writing.

12. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: can ‘i’ be used in a research paper .

A: Yes, ‘I’ can be used, but its usage should be measured and context-appropriate.

Q: Is it acceptable to use ‘We’ in a research paper?

A: Yes, ‘We’ can be used, particularly in collaborative research, but transparency about author contributions is crucial.

Q: When should ‘They’ be used in research papers?

A: ‘They’ is apt for referring to individuals or groups in a general sense or when gender-neutral language is required.

Q: how can common pronoun usage mistakes in academic writing be avoided.

A: Avoiding mistakes involves clear contextual use, maintaining objectivity, and providing transparency about authorship.

Q: What role do pronouns play in research papers?

A: Pronouns are linguistic tools that enhance the clarity, cohesiveness, and engagement of academic writing by replacing nouns, thus avoiding repetition.

Let Blainy be your trusted research assistant, guiding you to get quality research paper with latest trends and updates also to discover a wealth of resources, expert insights, and personalized assistance tailored to your research needs

Related Post

The art of crafting a concise research paper, crafting a wining research proposal: 10 key compon, how to use ai research paper generator.

- Tips & Guides

How To Avoid Using “We,” “You,” And “I” in an Essay

- Posted on October 27, 2022 October 27, 2022

Maintaining a formal voice while writing academic essays and papers is essential to sound objective.

One of the main rules of academic or formal writing is to avoid first-person pronouns like “we,” “you,” and “I.” These words pull focus away from the topic and shift it to the speaker – the opposite of your goal.

While it may seem difficult at first, some tricks can help you avoid personal language and keep a professional tone.

Let’s learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

What Is a Personal Pronoun?

Pronouns are words used to refer to a noun indirectly. Examples include “he,” “his,” “her,” and “hers.” Any time you refer to a noun – whether a person, object, or animal – without using its name, you use a pronoun.

Personal pronouns are a type of pronoun. A personal pronoun is a pronoun you use whenever you directly refer to the subject of the sentence.

Take the following short paragraph as an example:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. Mr. Smith also said that Mr. Smith lost Mr. Smith’s laptop in the lunchroom.”

The above sentence contains no pronouns at all. There are three places where you would insert a pronoun, but only two where you would put a personal pronoun. See the revised sentence below:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. He also said that he lost his laptop in the lunchroom.”

“He” is a personal pronoun because we are talking directly about Mr. Smith. “His” is not a personal pronoun (it’s a possessive pronoun) because we are not speaking directly about Mr. Smith. Rather, we are talking about Mr. Smith’s laptop.

If later on you talk about Mr. Smith’s laptop, you may say:

“Mr. Smith found it in his car, not the lunchroom!”

In this case, “it” is a personal pronoun because in this point of view we are making a reference to the laptop directly and not as something owned by Mr. Smith.

Why Avoid Personal Pronouns in Essay Writing

We’re teaching you how to avoid using “I” in writing, but why is this necessary? Academic writing aims to focus on a clear topic, sound objective, and paint the writer as a source of authority. Word choice can significantly impact your success in achieving these goals.

Writing that uses personal pronouns can unintentionally shift the reader’s focus onto the writer, pulling their focus away from the topic at hand.

Personal pronouns may also make your work seem less objective.

One of the most challenging parts of essay writing is learning which words to avoid and how to avoid them. Fortunately, following a few simple tricks, you can master the English Language and write like a pro in no time.

Alternatives To Using Personal Pronouns

How to not use “I” in a paper? What are the alternatives? There are many ways to avoid the use of personal pronouns in academic writing. By shifting your word choice and sentence structure, you can keep the overall meaning of your sentences while re-shaping your tone.

Utilize Passive Voice

In conventional writing, students are taught to avoid the passive voice as much as possible, but it can be an excellent way to avoid first-person pronouns in academic writing.

You can use the passive voice to avoid using pronouns. Take this sentence, for example:

“ We used 150 ml of HCl for the experiment.”

Instead of using “we” and the active voice, you can use a passive voice without a pronoun. The sentence above becomes:

“150 ml of HCl were used for the experiment.”

Using the passive voice removes your team from the experiment and makes your work sound more objective.

Take a Third-Person Perspective

Another answer to “how to avoid using ‘we’ in an essay?” is the use of a third-person perspective. Changing the perspective is a good way to take first-person pronouns out of a sentence. A third-person point of view will not use any first-person pronouns because the information is not given from the speaker’s perspective.

A third-person sentence is spoken entirely about the subject where the speaker is outside of the sentence.

Take a look at the sentence below:

“In this article you will learn about formal writing.”

The perspective in that sentence is second person, and it uses the personal pronoun “you.” You can change this sentence to sound more objective by using third-person pronouns:

“In this article the reader will learn about formal writing.”

The use of a third-person point of view makes the second sentence sound more academic and confident. Second-person pronouns, like those used in the first sentence, sound less formal and objective.

Be Specific With Word Choice

You can avoid first-personal pronouns by choosing your words carefully. Often, you may find that you are inserting unnecessary nouns into your work.

Take the following sentence as an example:

“ My research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

In this case, the first-person pronoun ‘my’ can be entirely cut out from the sentence. It then becomes:

“Research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

The second sentence is more succinct and sounds more authoritative without changing the sentence structure.

You should also make sure to watch out for the improper use of adverbs and nouns. Being careful with your word choice regarding nouns, adverbs, verbs, and adjectives can help mitigate your use of personal pronouns.

“They bravely started the French revolution in 1789.”

While this sentence might be fine in a story about the revolution, an essay or academic piece should only focus on the facts. The world ‘bravely’ is a good indicator that you are inserting unnecessary personal pronouns into your work.

We can revise this sentence into:

“The French revolution started in 1789.”

Avoid adverbs (adjectives that describe verbs), and you will find that you avoid personal pronouns by default.

Closing Thoughts

In academic writing, It is crucial to sound objective and focus on the topic. Using personal pronouns pulls the focus away from the subject and makes writing sound subjective.

Hopefully, this article has helped you learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

When working on any formal writing assignment, avoid personal pronouns and informal language as much as possible.

While getting the hang of academic writing, you will likely make some mistakes, so revising is vital. Always double-check for personal pronouns, plagiarism , spelling mistakes, and correctly cited pieces.

You can prevent and correct mistakes using a plagiarism checker at any time, completely for free.

Quetext is a platform that helps you with all those tasks. Check out all resources that are available to you today.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

Mastering Tone in Email Communication: A Guide to Professional Correspondence

- Posted on April 17, 2024

Mastering End-of-Sentence Punctuation: Periods, Question Marks, Exclamation Points, and More

- Posted on April 12, 2024

Mastering the Basics: Understanding the 4 Types of Sentences

- Posted on April 5, 2024

Can You Go to Jail for Plagiarism?

- Posted on March 22, 2024 March 22, 2024

Empowering Educators: How AI Detection Enhances Teachers’ Workload

- Posted on March 14, 2024

The Ethical Dimension | Navigating the Challenges of AI Detection in Education

- Posted on March 8, 2024

How to Write a Thesis Statement & Essay Outline

- Posted on February 29, 2024 February 29, 2024

The Crucial Role of Grammar and Spell Check in Student Assignments

- Posted on February 23, 2024 February 23, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

We Vs. They: Using the First & Third Person in Research Papers

Writing in the first , second , or third person is referred to as the author’s point of view . When we write, our tendency is to personalize the text by writing in the first person . That is, we use pronouns such as “I” and “we”. This is acceptable when writing personal information, a journal, or a book. However, it is not common in academic writing.

Some writers find the use of first , second , or third person point of view a bit confusing while writing research papers. Since second person is avoided while writing in academic or scientific papers, the main confusion remains within first or third person.

In the following sections, we will discuss the usage and examples of the first , second , and third person point of view.

First Person Pronouns

The first person point of view simply means that we use the pronouns that refer to ourselves in the text. These are as follows:

Can we use I or We In the Scientific Paper?

Using these, we present the information based on what “we” found. In science and mathematics, this point of view is rarely used. It is often considered to be somewhat self-serving and arrogant . It is important to remember that when writing your research results, the focus of the communication is the research and not the persons who conducted the research. When you want to persuade the reader, it is best to avoid personal pronouns in academic writing even when it is personal opinion from the authors of the study. In addition to sounding somewhat arrogant, the strength of your findings might be underestimated.

For example:

Based on my results, I concluded that A and B did not equal to C.

In this example, the entire meaning of the research could be misconstrued. The results discussed are not those of the author ; they are generated from the experiment. To refer to the results in this context is incorrect and should be avoided. To make it more appropriate, the above sentence can be revised as follows:

Based on the results of the assay, A and B did not equal to C.

Second Person Pronouns

The second person point of view uses pronouns that refer to the reader. These are as follows:

This point of view is usually used in the context of providing instructions or advice , such as in “how to” manuals or recipe books. The reason behind using the second person is to engage the reader.

You will want to buy a turkey that is large enough to feed your extended family. Before cooking it, you must wash it first thoroughly with cold water.

Although this is a good technique for giving instructions, it is not appropriate in academic or scientific writing.

Third Person Pronouns

The third person point of view uses both proper nouns, such as a person’s name, and pronouns that refer to individuals or groups (e.g., doctors, researchers) but not directly to the reader. The ones that refer to individuals are as follows:

- Hers (possessive form)

- His (possessive form)

- Its (possessive form)

- One’s (possessive form)

The third person point of view that refers to groups include the following:

- Their (possessive form)

- Theirs (plural possessive form)

Everyone at the convention was interested in what Dr. Johnson presented. The instructors decided that the students should help pay for lab supplies. The researchers determined that there was not enough sample material to conduct the assay.

The third person point of view is generally used in scientific papers but, at times, the format can be difficult. We use indefinite pronouns to refer back to the subject but must avoid using masculine or feminine terminology. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he has enough material for his experiment. The nurse must ensure that she has a large enough blood sample for her assay.

Many authors attempt to resolve this issue by using “he or she” or “him or her,” but this gets cumbersome and too many of these can distract the reader. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he or she has enough material for his or her experiment. The nurse must ensure that he or she has a large enough blood sample for his or her assay.

These issues can easily be resolved by making the subjects plural as follows:

Researchers must ensure that they have enough material for their experiment. Nurses must ensure that they have large enough blood samples for their assay.

Exceptions to the Rules

As mentioned earlier, the third person is generally used in scientific writing, but the rules are not quite as stringent anymore. It is now acceptable to use both the first and third person pronouns in some contexts, but this is still under controversy.

In a February 2011 blog on Eloquent Science , Professor David M. Schultz presented several opinions on whether the author viewpoints differed. However, there appeared to be no consensus. Some believed that the old rules should stand to avoid subjectivity, while others believed that if the facts were valid, it didn’t matter which point of view was used.

First or Third Person: What Do The Journals Say

In general, it is acceptable in to use the first person point of view in abstracts, introductions, discussions, and conclusions, in some journals. Even then, avoid using “I” in these sections. Instead, use “we” to refer to the group of researchers that were part of the study. The third person point of view is used for writing methods and results sections. Consistency is the key and switching from one point of view to another within sections of a manuscript can be distracting and is discouraged. It is best to always check your author guidelines for that particular journal. Once that is done, make sure your manuscript is free from the above-mentioned or any other grammatical error.

You are the only researcher involved in your thesis project. You want to avoid using the first person point of view throughout, but there are no other researchers on the project so the pronoun “we” would not be appropriate. What do you do and why? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

I am writing the history of an engineering company for which I worked. How do I relate a significant incident that involved me?

Hi Roger, Thank you for your question. If you are narrating the history for the company that you worked at, you would have to refer to it from an employee’s perspective (third person). If you are writing the history as an account of your experiences with the company (including the significant incident), you could refer to yourself as ”I” or ”My.” (first person) You could go through other articles related to language and grammar on Enago Academy’s website https://enago.com/academy/ to help you with your document drafting. Did you get a chance to install our free Mobile App? https://www.enago.com/academy/mobile-app/ . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter: https://www.enago.com/academy/subscribe-now/ .

Good day , i am writing a research paper and m y setting is a company . is it ethical to put the name of the company in the research paper . i the management has allowed me to conduct my research in thir company .

thanks docarlene diaz

Generally authors do not mention the names of the organization separately within the research paper. The name of the educational institution the researcher or the PhD student is working in needs to be mentioned along with the name in the list of authors. However, if the research has been carried out in a company, it might not be mandatory to mention the name after the name in the list of authors. You can check with the author guidelines of your target journal and if needed confirm with the editor of the journal. Also check with the mangement of the company whether they want the name of the company to be mentioned in the research paper.

Finishing up my dissertation the information is clear and concise.

How to write the right first person pronoun if there is a single researcher? Thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to content

- Home – AI for Research

Can you use I in a research paper