- Spring Break Sale starts now with code: Break25

History of Sign Language – Deaf History

- February 15, 2021

- by Michelle Jay

- 19 Comments

The events that occurred in the history of sign language are actually pretty shocking.

How deaf people experience life today is directly related to how they were treated in the past. It wasn’t long ago when the deaf were harshly oppressed and denied even their fundamental rights.

The are many famous deaf people who have made a name for the deaf throughout the history of sign language and proved that deaf people can, in fact, make history.

Aristotle was the first to have a claim recorded about the deaf. His theory was that people can only learn through hearing spoken language. Deaf people were therefore seen as being unable to learn or be educated at all.

Therefore, they were denied even their fundamental rights. In some places, they weren’t permitted to buy property or marry. Some were even forced to have guardians. The law had them labeled as “non-persons”.

Aristotle’s claim was disputed in Europe during the Renaissance. Scholars were attempting to educate deaf persons for the first time and prove the 2,000 year old beliefs wrong. This mark in the history of sign language is what started the creation of a signed language.

Starting to Educate the Deaf

Geronimo Cardano , an Italian mathematician and physician, was probably the first scholar to identify that learning does not require hearing. He discovered, in the 1500s, that the deaf were able to be educated by using written words. He used his methods to educate his deaf son.

Pedro Ponce de Leon , a Spanish monk, was very successful with his teaching methods while teaching deaf children in Spain. This was around the same time that Cardano was educating his deaf son.

Juan Pablo de Bonet , a Spanish priest, studied Leon’s successful methods and was inspired to teach deaf people using his own methods. Bonet used the methods of writing, reading, and speechreading as well as his manual alphabet to educate the deaf. His manual alphabet system was the first recognized in Deaf history. The handshapes in this alphabet corresponded to different sounds of speech.

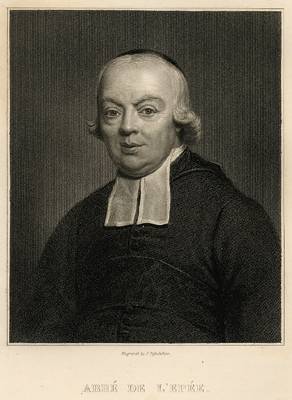

Organized deaf education was non-existent until around 1750. This was when the first social and religious association for deaf people was founded by Abbe de L’Epee , a French Catholic priest, in Paris. Abbe Charles Michel de L’Epee is one of the most important people in the history of sign language.

Abbe Charles Michel de L’Epee established the National Institute for Deaf-Mutes in 1771. This was the first public free deaf school. Deaf children came from all across France to attend the school and brought the signs they learned from signing at home with them to the school. L’Epee learned all of these different signs and utilized the signs he learned from his students to teach his students French.

The signs they used soon became a standard signed language L’Epee taught to the students. More schools were founded and the students brought this language back to their neighborhoods. The standard language L’Epee used in the history of sign language is known as Old French Sign Language. This language spread across Europe as more students were educated.

Many people say that Abbe de L’Epee invented sign language–which is not true. If you want to know who invented sign language, read our “ Who Invented Sign Language ” article.

Although Abbe de L’Epee claimed sign language is the native language for the deaf, Samuel Heinicke believed in Oralism. Oralism was brought about as people used speechreading and speech to teach deaf students instead of manual language.

Even though this positive advancement in sign language history took place, oralism was the bump in the road.

In relation to the deaf-blind, the first deaf-blind person to be educated was Laura Bridgman . She was born 50 years before Helen Keller, but is usually not credited with being the first deaf-blind person to learn language.

Helen Keller is the most well-known deaf-blind person (she has taken the credit before Laura Bridgman). Her teacher was Anne Sullivan and while Helen Keller wasn’t the first deaf-blind person to be educated, she was the first one to graduate from college, and she did it with honors.

Another common topic in the Deaf Community is deaf people and sports. A favorite deaf athlete is William “Dummy” Hoy . Dummy Hoy was the first deaf major league baseball player. He hit the first grand-slam home run in the American league, and created the hand signals that are still used in baseball today. It is so amazing that one deaf athlete can have so much impact and break so many records in baseball, yet many people don’t know about him. Truly amazing.

There are many famous deaf people in the history of America as well. Deaf Smith , for example, is famous for the important role he played in the Texas Revolution. Deaf Smith County, Texas is named after him.

American Sign Language

The history of American Sign Language has earned its own page. Please don’t forget to read about this important part of the history of sign language in the United States.

Speech versus Sign

Sign language is now seen as the native communication and education method for deaf people. However, it wasn’t always this way.

Even though sign language became commonly used, supporters of the oralism method believed the deaf must learn spoken language to fully function in hearing society.

Two of the largest deaf schools in America began educating the deaf in 1867 using only oral methods and encouraged all deaf schools to do the same. These methods did not use any sign language and began to spread to schools for the deaf across the U.S.

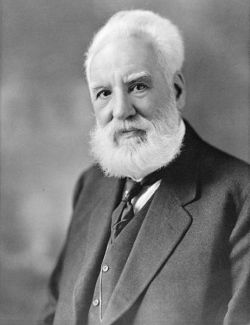

Probably the most devoted supporter of the oralism method was Alexander Graham Bell (yes, the man who is credited with inventing the telephone). Bell started an institution in Boston in 1872 to train teachers of deaf people to use oral education. He was one person in the history of sign language who really tried to damage the lives of deaf people.

In 1890, he founded an organization that is now known as the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf .

The dispute of sign language versus spoken language continued for the next century in sign language history. The International Congress on the Education of the Deaf met in Milan, Italy in 1880 to discuss the issue. This meeting is now known as the Milan Conference.

The supporters of the oralism method won the vote. Congress declared “that the oral method should be preferred to that of signs in the education and instruction of deaf-mutes”.

The outcome of the conference were devastating. Over the next ten years, sign language use in educating the deaf drastically declined. This milestone in the history of sign language almost brought the Deaf back to ground zero after all of their progress. Almost all deaf education programs used the oralism method by 1920.

Even though oralism won the battle, they did not win the war. American Sign Language still was primarily used out of the classroom environment. The National Association of the Deaf was founded in the United States and fought for the use of sign language. They gained a lot of support and maintained the use of sign language as they argued that oralism isn’t the right educational choice for all deaf people.

In 1960, something big happened. William Stokoe , a scholar and hearing professor at Gallaudet University, published a dissertation that proved ASL is a genuine language with a unique syntax and grammar.

ASL was henceforth recognized as a national language and this was one of the biggest events in sign language history.

In 1964, the Babbidge Report was issued by Congress on the oral education of the deaf. It stated that oralism is a “dismal failure” which finally discharged the decision made at the Milan Conference.

In 1970, a teaching method was born that did not fully support either sign language or oralism. Instead, the movement attempted to bring together several educational methods to form Total Communication . This method became a new philosophy for deaf education.

Allowing the deaf access to information by any means, Total Communication can include fingerspelling, sign language, speech, pantomime, lipreading, pictures, computers, writing, gestures, reading, facial expressions, and hearing aids.

Another huge event in the history of sign language was the Deaf President Now (DPN) movement at Gallaudet University in 1988. The DPN movement unified deaf people of every age and background in a collective fight to be heard. Their triumph was a testament to the fact that they don’t have to accept society’s limitation on their culture.

Andrew Foster was the first African American Deaf person to earn a Bachelor’s Degree from Gallaudet University in 1954 and is known as the “Father of the Deaf” of Africa.

In 1995, a woman named Heather Whitestone became the first deaf woman to be named Miss America in the Miss America pageant. She showed the world that a deaf person can do anything a hearing person can do, and that all things are possible with God’s help.

The Best Deaf History Books

We highly recommend all of the books in this list. They will give you a greater insight into the history that the Deaf had to endure than you have ever known.

Please note that when you choose to purchase through the external links on this website (in many but not all cases) we will receive a referral commission. However, this commission does not influence the information we provide in this site. We always give honest opinions and reviews to share our findings, beliefs, and/or experiences. You can view our full disclosure on this page .

Forbidden Signs: American Culture and the Campaign against Sign Language This book focuses on the history of the oppression of American Sign Language. We highly recommend this book because it is not only easy to read, it goes into detail about how sign language was forbidden in schools and the fact that many attempts have been made by hearing society to prevent deaf people from using sign language. Highly, highly recommended!

Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New Scholarship This book is a little difficult to read at times, but it offers great information. The book compiles 16 essays that range in topics from new themes in Deaf history and Deaf culture experiences compared to the experiences of African American culture to societal paternalism toward the Deaf and the determination of Deaf people to establish employment, education, and social structures. This book is a deep read, but well worth it!

A Place of Their Own: Creating the Deaf Community in America Some books just talk about Deaf culture and how it is today. This book actually goes in depth and back into Deaf history to explain the trends and the changes that have taken place in the Deaf community. We highly recommend this book for anyone learning ASL and becoming involved in the Deaf community.

Deaf President Now!: The 1988 Revolution at Gallaudet University Understanding the Deaf President Now movement is critical to understanding Deaf Culture. To read more about DPN and gain a more in-depth understanding about what happened that year, we highly recommend this book.

Baltimore’s Deaf Heritage (Images of America) A great book for comparative cultural studies on the Deaf cultures in different areas, Baltimore’s Deaf Heritage illustrates the evolution of Baltimore’s Deaf community and its prominent leaders.

Detroit’s Deaf Heritage (Images of America) A great book for comparative cultural studies on the Deaf cultures in different areas, Detroit’s Deaf Heritage illustrates the evolution of the deaf community in Detroit and its prominent leaders.

- Deaf Culture

Deaf history greatly affects how deaf people live their lives today. And not only do deaf people have a history, they have a culture… Deaf Culture.

Deaf culture is culture like any other. Deaf people share a language, rules for behavior, values, and traditions. The way the Deaf culture is living today is a direct result of the Deaf history that preceded it.

Articles Submitted by Students

Who is your favorite person from deaf history?

My own views on deaf history

by Nicki (Canada) | July 17, 2013

After reading this article, as well as the other available ones on this site and a few from another ASL book I am reading I have come to the conclusion that I can’t choose one person in deaf history as my favourite. I have to say that they all have their goods and bads just like any other person.

I will say that Aristotle was entirely wrong in his views that people are only able to learn through spoken language or oralism. I can say that even hearing people don’t all only learn through spoken language, I am mostly hearing a visual learner and found that my teachers talking, in later grades, only made it more difficult to learn. Although perhaps he meant well with his statements, I suppose we will never know.

I certainly applaud the efforts of early deaf educators and say that without them deaf people would quite possibly not be as advanced in society as they are today and as they deserve to be. Juan Pablo de Bonet was very well meaning in his attempts and absolutely did good by deaf people of the time in educating them. This said, I am sure his version of deaf education was still far below that of hearing education and, although, the students could read and write and understand some speechreading, this probably still left them with a very low level education but something is better than nothing at all.

Abbe de L’Epee was absolutely one of the most important people in deaf history and without him deaf education would not have become as well known. He helped teach a generalized sign language so that deaf people could communicate with one another and with their hearing friends and family if those people were interested in learning.

Samuel Heinicke is another one of those people I would like to, try to, give the benefit of the doubt. He believed in oralism, I am sure he meant well with his ideas. He probably just wanted to make deaf people more like, or more understandable to hearing people. This however, would never work based on things we know today. Not all deaf people can be totally oral and those people deserve a language of their own to communicate their needs and wants.

Helen Keller and Laura Bridgman are both very important people in deaf history as well, showing that all deaf people can learn even if they are unable to see. I would go as far as to say that they are important to all educational history in the sense that this shows that all people are able to learn, not matter their challenges. I would like to give a hand to these ladies’ teachers as well as they had to deal with a lot of stress and difficulties while education these two people.

Alexander Graham Bell is another interesting person to deaf history. He made the choice to support oralism and I assume it was for the same reasons as all the other oralism only people but at least he eventually came around and realized that oralism is not the only way, just one way, for deaf people to learn.

William Stokoe was another very important figure and he is absolutely correct in saying that ASL is a genuine language with a unique syntax and grammar. His publication changed deaf learning forever in making ASL a national language.

The decision to use total education was also a great one in my opinion, deaf people should have the right to learn just as well as hearing people and, perhaps it is just because I was educated in a hearing school and am mostly hearing, I feel they should be taught the way that works for them, be it all sign or a mix of sign and oralism.

I also applaud the efforts of the Gallaudet University student and staff in the Deaf President Now protest and say that these people also changed deaf history for the better.

The final person mentioned in this article is Heather Whitestone, yes she may have been named Miss America and proven that deaf people can do what hearing people can but she is a bad representation of deaf people as a whole. It is well known that she refused to use ASL and looked down on those who did use it. Great for her but not a good show of who deaf people truly are.

As you can see, I couldn’t choose a favourite. All of these people, good and bad had an impact on deaf history and education, perhaps without the setbacks deaf people would be further advanced but I believe that these challenges made them work harder and so maybe makes them more determined than others. Either way all of these people, except Heather Whitestone are all important people.

Influences in Deaf History

by Steph Grizzard | February 24, 2017

I don’t know if I can pick a favorite person to influence deaf history. It is such a rich history and the culture is what it is today because of all of them together. Abbe de L’Epee founded the first public deaf school and used all of the signs that the students were using at home to create a whole language. Thomas Gallaudet was inspired by his neighbors daughter which influenced him to travel overseas and meet the people that developed a language and schools for the deaf. He was inspired even more by Abbe Sicard, Jean Massieu, and Laurent Clerc. He even convinced Laurent Clerc to come back to America with him to open the first public deaf school in America. Thomas Gallaudet inspired his son, Edward, to start the first deaf college in the U.S. which is now named Gallaudet University. Even Alexander Graham Bell, who was inspired to invent the telephone in hopes that it would help his mother and wife hear, was a big influence in the deaf world. He tutored Helen Keller and, although not a popular method in the deaf community, was a huge supporter of oralism. The entire history of the deaf community and deaf world is too fascinating for me to be able to pick just one favorite influential person. The fact that every person had a hand in making the deaf Culture the beautiful world that it is today, is enough for me to love them all.

There are several

by Sue | December 21, 2017

I’ve been losing my hearing for many many years now and it’s becoming more and more profound as I get older and the tinnitus gets louder and louder. I’ve know since a very young age that my hearing would go and now that day is fast approaching. Reading the Deaf History is fascinating to me.

I think that early on I am intrigued with Thomas Gallaudet. It seems he began this adventure to help out his neighbor which I find very inspirational. And then he became even more interested in helping the deaf to learn to communicate and traveled to Europe to study the techniques of others and even convinced some to travel to America to help set up schools here. It’s really something that his son kept on with this legacy and that school still exists today.

I’ve always been inspired by Helen Keller and how she overcame incredible obstacles. She was an amazing woman.

One thing I must point out – I really hate the term Deaf and Dumb and I even bristle at the term Deaf-Mutes. Deaf people most assuredly aren’t dumb and they can make sounds. These are both false terms and I’m glad to see that they aren’t used much if at all anymore.

Great People of the Deaf Community

by Lexi (Las Vegas) | March 8, 2013

There are so many inspirations in this world, but deaf people inspire me the most. I see deaf people as equals, but much more courageous. The things they overcome just amazes me.

Helen Keller surprises me. I can’t imagine being neither deaf nor blind and she was both. And graduating college! She was an amazing woman and she is such an inspiration. Seeing people overcome these challenges, makes me want to overcome mine. After reading this, I feel like I could do much more than I do now. Challenge myself to do more difficult things, just as Helen did. She couldn’t have been anymore courageous.

Another person that is my favorite is William “Dummy” Hoy. My dad is a huge baseball fan and I can imagine him and a lot of his baseball friends have no idea who this is. Baseball is a tough sport, just like any other, and this man truly amazes me for being such a big part of it. He changed the sport.

It makes me a little frustrated that Alexander Graham Bell would do the things he did. He didn’t have a right to change the way that the deaf community communicates. It disgusts me that many hearing people didn’t have the respect that they should have for deaf people. It’s just awful.

Learning sign language is one of the best things I think I could do. I’m so happy that I am doing it, and after this article, I will be more and more motivated to work my best.

So Much History To Cover

by Carol (White Cloud, Michigan) | March 8, 2013

I am not sure I could pick one person that is a favorite at this time. I have already learned so many interesting things from deaf history that are not only educational, but shocking. As a full hearing person, I was taught that Helen Keller was the first deaf person ever taught, and now I learned that is false. I now have to gain more knowledge about deaf history that was either wrong to begin with or just never taught at all.

As I was growing up, the only thing I ever learned about the deaf culture was Helen Keller and that was from a movie. I was clueless about information like Alexander Graham Bell being involved with the deaf community. I am not too sure if Bell was a good thing or bad thing for the deaf community. After opening schools for the deaf to help them communicate, supporting oralism as Bell did, was later found to be a setback to the deaf society. I have a lot of reading to do before I could ever pick a favorite from deaf history.

It seems to me that the deaf community has been cut off from the hearing culture, unless you go looking for it.

by Karen Arnold (Hamilton, Indiana) | March 8, 2013

The persons that I feel contributed most to the advancement of communication with and for the Deaf is GOD because he gave the Deaf, their desire to express themselves and to be understood. As a hearing person, I learned to express myself through hearing others talk. For most people (hearing) language is acquired by means of hearing and is expressed by speaking. When formulating concepts and ideas, most people who can hear spontaneously rehearse spoken words and phrases in their mind prior to speaking them. However, when a child is born deaf, can the mind formulate thoughts in another way? YES. There is a language that can transfer ideas, abstract and concrete, from one mind to another without a sound ever being made.

One of the wonders of the human mind is our capacity for language and our ability to adapt it. However without hearing, learning a language usually becomes a function of the eyes, not the ears. Happily, God gave us the desire to communicate and it burns deep within the human soul, enabling us to overcome any apparent obstacle. This need has led Deaf people to develop many signed languages worldwide. As they have come in contact with one another, having been born into Deaf families or brought together at specialized schools and in the community, the result has been the development of a sophisticated language that is custom-made for the eyes—a signed language that is truly beautiful to watch and learn.

The best parent wants to communicate with their child and if that child is Deaf or the parent is the best thing that could show their love is to learn (or teach) sign language to their child. They would see that Deaf people can formulate thoughts, abstract and concrete without needing to think in a spoken tongue just as each of us hearing, formulates thoughts in our own language. They think in their signed language.

Learning sign as a child is a benefit for the child born Deaf and the hearing child of Deaf parents. The future of a child born Deaf is better because they can learn to support themselves and communicate their needs. Being hearing doesn’t mean you are smart just like being deaf doesn’t mean you are dumb. Hearing is using your ears while signing is using your eyes.

I am impressed by the subtle complexities and the richness of expression of ASL. Most topics, thought or ideas can be expressed by sign language. I hope the trend continues to be that Deaf are taught in sign language and that more people will take the initiative to learn ASL to communicate with our fellow citizens.

Deaf people. Deaf History.

by Jenna (Washington) | March 8, 2013

Honestly, I don’t think I could choose one person to be my favorite of all Deaf people. I mean, after all, the reason we have Deaf History is because of the people.

Before studying up on Deaf History, I never knew how many people were subject to the great changes made by these wonderful teachers. (Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, and Abbe Charles Michel… etc.) And the teachers who were so inspired (as I am), by all the Deaf people who wanted to be taught.

Deaf people have their History because of what they’ve done together, and what they’ve accomplished as a whole. Each great person who did their part should get credit, and I think it’s amazing that so many great individuals played a role in the History of the Deaf.

To me, the thing that draws my attention the most, is how strong and how connected they are to one another. Deaf history is so cool, and I wish I could be a part of it, but I think it’s simply amazing that God could connect a peoples by this beautiful language, and for creating everyone who played a part in it.

I think the best part of Deaf history is the way all these people were able to accomplish something together, and were able to show the world what they really can do!

Touched By A Touch

by Janeel Hew (Hawaii) | June 6, 2010

Hands that speak all I needed to hear. In history, time spans endlessly. I, on the other hand, need go back only 40 years to find my favorite person of Deaf Culture in my life.

I wish that I could tell you his name, but I never knew it. I did know his smile, his eyes, and his touch–he could make my world go away. His hands are the most precious gift that God has given to him to share with others for I believe they hold his heart. Perhaps he might one day read this and realize how much of an impact he made on me?

In the 1970’s I grew up on Greenberry Dr. in Southern Ca. We had a true melting pot when it came to the children there. Different races, religions, illnesses and abilities. It was a great place for learning how to love your neighbor. We moved away when I was still in elementary school. And the one person that I’ll always remember is the boy that never spoke a word. I would wait for him to get off of his small yellow bus, that I always wished that I could ride on with him. I wanted to talk with him…I wanted to play with him…he was my very first crush, and I couldn’t even tell him my name. He was older than me and I probably made a fool of myself too. But, I would still wait…he would look at me with such understanding eyes as I would try to greet him. Eyes that could look deeper than any others. And smile at me…with a smile that seemed to say…”Silly little girl,” and “Sorry, our worlds are different.”

Yet at the same time be so understanding of my frustration in not being able to talk with him. And then he would make both my waiting and frustration all worth it…with a single touch…my heart would beat so fast as I watch his hand raise up and rub the top of my head. Then again he would smile, and walk away…go into his house, and I would have to wait another day for the small yellow bus before I would see him again.

My father is a jazz musician, and I would hide under the baby grand piano, so that I could feel the music…Oh, I can hear, but for me feeling life is just as important as life itself. It was far greater than seeing the ugliness of the drunken drug addict whose music has such beauty. The touch of a raging father and the weakness of my mother’s constant kidney health…would all go away…even if it was just for a moment…by the touch of a boy, who never spoke a word…yet said exactly what I needed to hear!!! Where ever you are… Thank You.

by Peggy: I know just where you are coming from. I too have come across that kind of situation and felt the warmness of that person. Their silent voice that seemed to speak, although you could hear nothing. It’s those type of people that keep your spirits up and give you a reason for living. Bravo for the silent voices that have so much to offer.

by Brenda: Your writing, “Touched by a Touch” was so beautifully written. I am sure the boy could read your own heart in your eyes and smile. And in this age of technology, anything is possible. Please let us know if you ever complete the circle and see him again. God Bless.

Off the beaten path…

by Rick Whited (Grand Terrace, CA) | November 7, 2014

I’m with others in noting that all of these individuals played a significant role in the history of sign language – some from a positive perspective, others from a negative. What more can be said of L’Epee and the Gallaudet’s? Even Bell thought he was progressing the education and quality of life of the deaf with what he was doing and it really did contribute to a better understanding of what was necessary for the deaf to maximize their potential.

That said, I’ll approach this from a more personal level. When I was 11, a family moved in across the street and one of the kids was a quiet, timid boy who eventually became my best friend growing up. Dave was deaf and he and his family were under the impression that if he could simply vocalize and read lips, then he would function in hearing society without hitch. I knew that was nonsense, but I also knew that Dave was smart and a tremendously talented artist. Unfortunately, everyone he came into contact with thought he was retarded and because he was trying to read lips and vocalize his confidence took a beating while people pushed him away and rejected him.

It wasn’t until his mother enrolled him at California School for the Deaf at Riverside and he learned sign language that he came out of his shell. Our ability to communicate with each other and his ability to express himself through his signing and my translating grew tremendously. It was an eye-opening experience for a 12 year old kid and even though Dave moved away when I was 16, the importance of his ability to communicate with his signing never left me. I stopped using my signing (and I had a young teenager vocabulary when I stopped!), but recently was reminded that there is a need to keep those lines of communication open with the deaf community, so I’m learning it all over again! So, first, thank you CSDR for changing lives.

The second significant person was the person responsible for the movie “Mr. Holland’s Opus” and other movies like it. Despite its leftist message at times, the movie did a good job of showing the fear, the confusion, the anger, the frustration, the difficulty that exists on both sides of the fence when it comes to deaf people existing in a hearing world – or vice versa! It also did a good job of showing the amazing talent that exists in the deaf. Sadly, I think there is still a natural tendency in the hearing to think that there is something “broken” in the deaf and movies like this help dispel that notion and maybe, just maybe, it might encourage those from both sides to step up and say hello.

When that happens, we all benefit!

Who is Your Favorite Person from Deaf History? Share Your Thoughts!

There are so many people who played a significant role in the history of sign language. So, naturally, everyone is bound to have a favorite!

Who is YOUR favorite historical figure? Is it Abbe de L’Epee? Thomas H. Gallaudet? Alexander Graham Bell? Share your thoughts!

For Start ASL Assignment Submissions: Don’t forget to tell us why this person is your favorite as well–make it a good well thought-out answer of at least 500 words. Try to also think outside the box and perhaps choose someone who hasn’t been mentioned yet. It will be fun to see why everyone chose who they did!

19 Responses

The first educated deafblind person was not Laura or Helen. It was Victorine Morriseau – France (1789-1832) – who was the first to learn and use a formal language.

I just recently started ASL, and I am not deaf, but I already find ASL extremely interesting. I have always wanted to learn ASL, and now that I’ve learned some of its history, it has become immensely challenging to choose a favorite figure in history. If I had to choose one, it would have to be Abbe de L’Epee. He pretty much invented sign language, and without him, deaf people would have probably not had any organization for a very long time. It is amazing how, instead of trying to teach deaf people the way other people are taught, Abbe de L’Epee took the time to find a style of learning that works for deaf people. Abbe de L’Epee was a truly amazing figure in deaf history. He definitively earned his name, “Father of the Deaf.”

when was this written

As someone who is just starting to learn about deaf History and culture, I don’t feel like I can choose just one favorite. Based off of this article alone, I really believe that Louis Laurent Clerc was a huge influence and a great educator for the deaf community. He seemed to have a real passion to educate the deaf and spent the better part of his life doing just that. His legacy still lives on in deaf schools across the world. I also found it fascinating to learn about William Hoy. My daughter plays softball and it was very interesting to read how he influenced the umpire signals used today and made a lasting impact on the game even though he isn’t widely known outside the deaf community. In further reading about deaf historical figures, I was surprised to discover that Thomas Edison was also deaf, something I may have learned years ago in school, but had not thought about or realized again until now. I wish schools would teach more of these kinds of stories and facts and incorporate these people into their history lessons instead of only teaching Helen Keller for deaf history. Thank you for this article and for enlightening me on deaf people who made an impact.

It’s hard to choose, but Hellen Keller has to be my favorite person in sign language history. I have watched documentaries and read biographies about her because her story is inspirational. She is my favorite because she broke down so many barriers and proved to the world that the deaf and blind can be successful.

From reading this article I can not possibly choose one favourite person but to me Juan Pablo de Bonet is amazing as he was one of the first to try and teach a deaf student other than his child. I admire those who created ways to teach their own children but to me Bonet stepped outside of the comfort zone. He chose to do something that was very uncommon at the time . When those that were deaf were typically pushed aside and disregarded he decided to create a manual language and use his own methods to teach. To me that takes courage, to go against what other people are saying and just try any way. That is something that I think each person in sign language history did, the went against the norm (well except Alexander Graham Bell, but lets not get into that). I couldn’t imagine having to deal with people like that saying that I was unable to learn or communicate effectively (I’m hearing) I’m thankful for those who paved the way and the ability to learn sign today.

Helle can I please have a name for the author of this article? Thanks I need it for a project

Hi Reilly, You can use the name Michelle Jay. :)

Is that the actual author?

Yes, it is.

When was this article published?

This article was published in 2008. :)

What day,month and year this article was published?

Hello Harlie! Send us an email here and we will assist you with that: https://www.startasl.com/contact-us/

Hello! When is the exact date? I need it for a project

I am inspired by Dr. Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. I am amazed at the passion he had for teaching the deaf. For a man to leave his home country, his family and friends, and his ministry, and travel half way across the world simply to learn how to teach the deaf is mind boggling. And why did he do it? Because he had a young deaf girl as a neighbor; not a family member, but just a neighbor. What love and care he must have had for that young lady and her family to go to such lengths to help her. Also he took it a step farther and started a public school for the deaf, inviting the deaf to come from all over the country. He not only did all of the above, but he made teaching the deaf his life long ministry. I find such a commitment extremely intriguing. Oh that people in today’s day and age would have such compassion for others! I, myself have had a strong, burning desire to learn sign language and to work with the deaf for as long as I can remember, but I’m not sure that even I could say that I have that kind of a commitment to it.

Anne Sullivan is most interesting to me, because, even though she did not have hearing loss herself, she overcame her own visual impairment to prove that Deaf/Blind individuals can learn to read, write, and speak fluently. She overcame innumerable obstacles in her fight to educate Helen Keller whose family and herself did not make it easy for this first-time teacher. Sullivan dedicated her entire life and health to educating, interpreting for, and supporting Helen Keller. She was so successful that Keller learned multiple languages, gave speeches around the world, and wrote articles and a memoir without assistance. After graduating from university, Helen Keller became an enormous advocate of education for the Deaf, Deaf/Blind, and individuals with other disabilities. Without Anne Sullivan, none of that would have been possible, and Helen would have languished without language or direct interaction, probably ending up in an asylum.

At the risk of coming across as a cliche, I have to say that Abbe de L’Eppe is my favorite person from the history of American Sign Language. Reading about how much he did for the Deaf community brought tears to my eyes and inspiration to my heart. The fact that he decided to learn how to communicate properly with the Deaf instead of forcing his usual ways of communication onto them was an extremely honorable rarity for that time period. Though everyone should have that mind-set, it was uncommon and amazing that he was able to stray from what others thought and aid the Deaf in showing their true potential. I definitely understand the reasoning behind his being named “Father of the Deaf.”

I first learned about Sue Thomas through the T.V. show named after her. It was this show, I think, that sparked my long lasting interest in learning ASL. The lead role is played by Deanne Bray who portrays Sue Thomas so well. Sue has such great faith in God that has held her through so many trials in her life. After her mom passed away she started a program called Silent Night to help homeless people. There is also The Levi Foundation, a dog training centre named in honour of her first hearing dog, Levi. She has written a book, learned piano, and worked for the F.B.I. Thomas has accomplished so many things in her life. Along with Sue Thomas F.B.Eye, I recently found another movie called No Ordinary Hero. It shows a little bit of what life for Deaf people is like. You can see how some people can be so rude and others can be more understanding. If I had to choose someone else in Deaf history who lived a little longer ago, I would probably choose William Stokoe. He proved that ASL is a language in and of itself, and without him, I don’t know if this website, StartASL.com, would have been created in the first place

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Take ASL 1 for Free!

Latest posts.

Ready to learn on-the-go? Download our mobile app ecourse and start learning anytime, anywhere!

ASL Courses

- All Courses

- Online Course

- Offline Course

- Teachers/Schools

- Homeschoolers

- Free Lessons

- ASL Tutoring

- Deaf/ASL Events

ASL Resources

- All Articles

- ASL Dictionary

- ASL Alphabet

- Top 150 Signs

- Deaf History

- Interpreting

- Hearing Loss

- Products Recommendations

- Testimonials

- Privacy Policy

Take ASL 1 For Free!

Sign up today! Start learning American Sign Language with our Free Online ASL 1 Course . No credit card required.

The History and Evolution of American Sign Language: A Journey of Recognition and Empowerment

- April 7, 2023

Introduction

American Sign Language (ASL) is a complex, fully developed visual-spatial language utilized by the Deaf and hard-of-hearing communities in the United States and parts of Canada. ASL has a rich history that reflects the resilience and determination of the Deaf community in seeking recognition and social equality. This essay will provide an overview of the origins of ASL, its development over time, the influences of other sign languages and linguistic communities on its evolution, and the key historical figures, educational institutions, and milestones that have contributed to its growth and recognition as a distinct and valuable language.

Origins of ASL

The roots of ASL can be traced back to the early 19th century, with the merging of local sign languages and the Old French Sign Language (OFSL) brought to the United States by Laurent Clerc, a Deaf educator from France (Lane, Hoffmeister, & Bahan, 1996). In 1817, Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, an American educator, established the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in Hartford, Connecticut, which became the cradle of ASL (Lane et al., 1996). The ASD provided an environment where the combination of OFSL and the regional sign languages of Martha’s Vineyard, Henniker, and Sandy River Valley, among others, gave birth to what we now know as ASL (Groce, 1985).

Development of ASL

ASL continued to develop and evolve throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Its expansion was propelled by the establishment of more schools for the Deaf, such as the New York Institution for the Deaf in 1818 and the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf in 1820 (Gannon, 1981). As the Deaf community grew, so did the linguistic diversity of ASL, as regional variations and dialects emerged (Lucas, Bayley, & Valli, 2001).

One of the most significant milestones in the development of ASL was the publication of the first ASL dictionary by William Stokoe in 1960 (Stokoe, 1960). Stokoe’s work demonstrated that ASL possessed a linguistic structure and grammar distinct from English, contributing to its recognition as a bona fide language (Stokoe, 1960). Subsequent research further established ASL as a complex and robust language with its own syntax, morphology, phonology, and semantics (Klima & Bellugi, 1979).

Influences of Other Sign Languages and Linguistic Communities

Various sign languages and linguistic communities have influenced ASL throughout its history. As previously mentioned, OFSL played a pivotal role in the formation of ASL, providing a foundation upon which regional sign languages could merge (Lane et al., 1996). Additionally, ASL has been influenced by Black American Sign Language (BASL), which developed among African American Deaf communities during segregation (Lucas, Bayley, & Valli, 2001). The two languages share many similarities, but BASL exhibits unique phonological, lexical, and syntactic features that reflect its users’ distinct experiences and cultural identities (Lucas et al., 2001).

Key Historical Figures, Educational Institutions, and Milestones

The history of ASL is marked by the contributions of key figures, educational institutions, and milestones that have shaped its growth and recognition. Thomas Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc were instrumental in founding ASD, which served as the birthplace of ASL and a model for other Deaf schools across the country (Lane et al., 1996). Another notable figure is Edward Miner Gallaudet, Thomas Gallaudet’s son, who founded Gallaudet University in 1864, the world’s first and only liberal arts university for the Deaf (Gannon, 1981). Gallaudet University has since become a hub for research and innovation in ASL and Deaf culture.

Throughout the 20th century, several milestones contributed to the recognition and standardization of ASL. The National Association of the Deaf (NAD), founded in 1880, advocated for the rights of the Deaf community and promoted ASL as a legitimate language (Gannon, 1981). The work of William Stokoe and the publication of the first ASL dictionary in 1960 served as a turning point in the linguistic recognition of ASL (Stokoe, 1960). Later, the establishment of the Linguistics Research Laboratory at Gallaudet University in 1975 further advanced the study and documentation of ASL (Klima & Bellugi, 1979).

In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed, which granted Deaf individuals legal rights and protections, including the right to access ASL interpreters (ADA, 1990). This legislation marked an essential milestone in the recognition of ASL and the empowerment of the Deaf community.

The history of American Sign Language is a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and determination of the Deaf community in the United States. From its origins as a fusion of OFSL and local sign languages to its development and evolution over time, ASL has grown into a robust and distinct language that serves as a cornerstone of Deaf culture. The contributions of key historical figures, educational institutions, and milestones have been integral to the recognition of ASL as a valuable and legitimate language. As research and advocacy continue, ASL will continue to evolve and empower its users for future generations.

ADA. (1990). Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 327.

Gannon, J. R. (1981). Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America. National Association of the Deaf.

Groce, N. E. (1985). Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Harvard University Press.

Klima, E. S., & Bellugi, U. (1979). The Signs of Language. Harvard University Press.

Lane, H., Hoffmeister, R., & Bahan, B. (1996). A Journey into the DEAF-WORLD. DawnSignPress.

Lucas, C., Bayley, R., & Valli, C. (2001). Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language. Gallaudet University Press.

Stokoe, W. C. (1960). Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf. Studies in Linguistics: Occasional Papers (No. 8). University of Buffalo.

Related Posts

Guide to becoming a well-qualified sign language interpreter in america.

https://youtu.be/Cd7toF50aKA Understanding the Basics Before we get started, let’s talk about why sign

The Power of Authenticity in Interpreting

Interpreting is a field where every word holds significance. Beyond the immediate task

Maximizing the ASL Interpreting Experience: Pre-booking and Onsite Preparations

At Heritage Interpreting, we believe in the power of preparation. To quote Benjamin

597 High Street, #1264 Worthington, OH 43085

Phone: 1-800-921-0457

Many members of our operations team are Deaf.

YES! You can text this (800) number!

Please note that calling our (800) number will connect you to an answering service that will route your call or take a message on our behalf.

[email protected]

Join our mailing list to stay in touch regarding workshops, events, opportunities, and Heritage Interpreting info!

The History of American Sign Language Essay Sample

The History of American Sign Language Essay Sample

In the American Sign Language community, the deaf and hard of hearing people always have had a hard time communicating with hearing people. People who have hearing disabilities have been treated differently than hearing people ever since the 1800’s. It wasn’t until the 1850’s when people with hearing disabilities had their own residential school. Since then, America has gradually increased to be more helpful and overall more considerate to people who have disabilities. Interpreting as a career is very difficult since many people often confuse translating with interpreting making it difficult to communicate; interpreters must go through long testing procedures to get their certificates with the NIC, if interpreters want to work in schools they must go through another round of testing to get the EIPA certificate as well.

Often people confuse translating and interpreting as the same concept when they are both different styles of communicating. Interpreting is paraphrasing or changing the structure depending what the speaker says. In contrast, according to The Sign Language Interpreting Studies Readers translating is, “thoughts and words of the speaker are presented verbatim,” (Napier). In American Sign Language translating isn’t common unless the deaf/hard-of-hearing person is extremely literate who likes to have word for word. The need for interpreters is extremely high because there are only a handful of interpreters so most deaf/hard-of-hearing people will not have access to an interpreter unless they are participating in a public service such as being involved with court. Rolling over, most public services already have an American Sign Language interpreter on hand so the deaf/hard-of-hearing person doesn’t have a chance misinterpreting what is being said. For example, in The Sign Language Interpreting Studies Readers it explains what are some of the best places to have an interpreter, “legal problems in which people become involved require a sensitive and impartial inter-preter to assist in courtroom procedures, witness testimony, and general legal transactions involving real estate, bank notes, wills, insurance, compensation, and domestic relations,” (Napier). This quote shows all the places where interpreters are very important, with most interpreters in those public services it is hard to get one for personal use. Next, when having an interpreter for personal use deaf/hard-of-hearing people must talk to the interpreter and agree with they want interpreting for translating, this always will fluctuate depending on what situation the deaf/hard-of-hearing person is in. In conclusion, interpreting is very hard because different signers like different ways such as translating or interpreting but the interpreters in the public services must interpret since it is the most common communication.

In the late 1960’s and early 70’s the government announced that American Sign Language interpreters were now recognized as professions. To become an interpreter the interpreter must go through testing and get a certificate, one of the programs was: The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID). Every certificate had different credentials to be able to pass that certain program, Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf Inc. says "RID certifications are a highly valued asset and provide an independent verification of an interpreter’s knowledge and abilities allowing them to be nationally recognized for the delivery of interpreting services among diverse users of signed and spoken languages."(Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf Inc.). Between the 1990’s and early 2000’s the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) had become the main program to get the interpreter certification. The RID and the NAD were going head to head over who would be the best program. After a few years of battling, in 2002 they had a formal collaboration system called National Interpreter Certification. This certification has three levels to it, the normal beginner, the advanced, and the master. This certification consisted of a written test, interview, and a performance test. According to Verywell Health their program keeps getting harder, “However, starting in June 2012, hearing candidates for interpreter certification had to have at least a bachelor's degree and as of June 2016, deaf candidates for interpreter certification needed to have at least a bachelor's degree, but requirements may vary by state.” (Berke). This quote shows that the program doesn’t want anyone to join, they want people who have gone to college and have an education. This is important because depending where you want to work you may need knowledge of that career and vocabulary. To summarize, there is now only one program to become a certified interpreter and to be allowed to be in the program the candidate must have a four-year degree.

Interpreters can go into any career they desire, because there is always a need for one all the places deaf/hard-of-hearing people go. Since there is so much demand for interpreters but there aren't a lot of qualified interpreters most of the interpreters go into the jobs that pay they are most needed for. National Association of the Deaf gave some of the main careers interpreters go into, “ educational interpreting in K-12 and higher education settings; in the community, such as for doctor’s visits, court appearances, and business meetings; and for the provision of video relay services(VRS) and video remote interpreting (VRI) services.” (National Association of the Deaf). This quote shows that these interpreters are looking for the jobs and careers that they will be mostly needed for since they are in high demand. To go off the educational settings there is another program/ certification that the interpreters need to go through to be able to work at the schools. This is to make sure that they are able to interpret what is being said and the careful instructions that come with it since a lot of teachers go into deep detail. This certification is called Educational Interpreter Performance Assessment (EIPA). To pass the program, the candidate must get a 4.0 on the EIPA test, and according to Classroom interpreting other requirements are, “Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) certification, NAD-RID certification (NIC) at a certified level, NAD certification of at least a 4.0, Degree or coursework in an educationally-related field, BA degree (preferred), Graduate of an Interpreter Training Program, 24 – 30 credit hours of educational coursework, a formal assessment of content knowledge related to educational interpreting,the ability to perform as a professional member of the educational team.” (Schick). To explain, this quote shows that it is extremely difficult to become certified to be able to work in the education field. To summarize, there are many career and job opportunities for interpreters but some careers do need more certifications then others.

In conclusion, interpreters have come a long way of finally being recognized as a professional career and also a career that is in high demand. To become a certified interpreter it takes a lot of work and dedication to get through all the procedures in the program and pass all the tests with exceptional grades. Interpreters have lots of careers to choose from but some do need more education, training, experience, and certifications. Interpreting is different from translating and interpreting is more common but the signers need to communicate to decide what is better in that situation.Translating and interpreting are both very difficult skills, it takes a lot of work to become qualified to help people with hearing disabilities, lots focus and inspiration to want to work to get more certificates to help children in schools.

Related Samples

- Essay Sample: How Screen Time Could Affect The Teenage Brain

- Research Paper about Sleep Deprivation and False Confessions

- Caffeine Consumption Argumentative Essay Example

- The Effects of Social Media on Human Brain and Behavior Opinion Essay

- Being An Outsider Essay Sample

- Essay About Social Anxiety

- Faith, Hope, and Love for American Identity

- Narrative Essay Sample about Grandmother's Stroke

- Steroids Persuasive Essay Example

- Film Review: 10 Days in a Madhouse

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

Home Essay Examples Science Sign Language

Sign Language: History And Analysis Of Case Studies

- Category Science

- Subcategory Language and Linguistics

- Topic Sign Language

Introduction

Sign language has played a significant role in the deaf culture. Individuals who were deaf did not have a voice to communicate with, but when sign language was created it gave deaf individuals a newfound voice. Sign language started a new culture for the deaf community and brought them around the world together. In a deaf community, sign language is a vital form of communication. Despite the difficulties of speaking and learning that deaf people might encounter, they can efficiently and professionally communicate with hearing people, of course, with sign language. The latter, however, has been a central feature of communication throughout human history. Like any other language, sign language has changed and evolved into the structure that people can see at present since the beginning of human communication. Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning. Sign languages are natural languages with their own grammar and lexicon. This means that sign languages are not universal and they are not mutually intelligible, although there are also striking similarities among sign languages. Linguists consider both spoken and signed communication must be kinds of natural language, meaning that both emerged through an abstract, protracted aging process and evolved over time without meticulous planning. Sign language should not be confused with body language, a type of nonverbal communication.

The main aims and objectives of this paper are:

Our writers can write you a new plagiarism-free essay on any topic

- to collect data about sign language learning in Baku

- to investigate problems of learning and teaching process of sign language.

Wherever communities of deaf people exist, sign languages have developed as handy means of communication and they form the core of local deaf cultures. Although signing is used primarily by the deaf and hard of hearing, it is also used by hearing individuals, such as those unable to physically speak, those who have trouble with spoken language due to a disability or condition, or those with deaf family members, such as kids of deaf adults.

It is unknown how many sign languages exist worldwide. Every country generally has its own, native sign language, but some of them have more than one. The 2013 edition of Linguistics lists 137 sign languages. Most sign languages have accepted some form of legal recognition, while others have no status at all.

Linguists consider natural sign languages from the other systems that are precursors to them or derived from them, for example, invented manual codes for spoken languages, home signs, ‘baby signs’, and signs learned by non-human primates.

1.1 The history of Sign Language.

Historically, deaf and hard-of-hearing people are said to be known since ancient times. Socrates, in one of his earliest written records of a sign language from the fifth century BC says, ‘If we hadn’t a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn’t we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present”.

Besides, Friend refers to one of Stokoe`s main works about human sign language. Stokoe suggests that the roots of a language of gestures for example sign languages have their primate. It is as old as the race itself, and its earliest history is equally obscure. Despite the fact that hearing technologies are improved, and that sign language may witness kinds of decline in the future, sign languages still have their well-known position especially among parents who want and encourage their children to learn signs and symbols. It has many dialects and grammatical structures which are learnt by deaf community. Sign language is one of the methods of communication, which is defined as a set of visual symbols or gestures that are used in a very systematic way for words, concepts or ideas of a language. They are expressed through sign language by representing a relationship between the sign and its meaning in spoken language.

1.2 Literature Review

Allen and Anderson have claimed that sign language is seen to take a crucial part in the deaf `s special schools. This language has supporters and opponents. It is the most general and privileged way used by deaf community. In here, deaf people can have a unique education that the purpose of it is to integrate deaf individuals into humanity utilizing language. As a consequence, they can obtain their rescue and not be marginalized. In many educational contexts, an oral method was always used with deaf pupils. A teacher used spoken language while the deaf pupils were obliged to do lipread and to respond in spoken language. Astonishingly, neither teachers were allowed to use sign language nor pupils were given a chance to interact with it during classes. Pupils, though, were signing during breaks. As we can see, to survive, sign language as well as deaf people and those who use it, have been continuously fighting. Deaf children have the right to equal education. According to Barriga, the ability to use sign language gives strength for deaf people to be free , to be able to communicate quickly, to get a profession and to participate in both communities and family life. Sign language has its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, mentioned that sign language is the main solution for them. It fits their needs to communicate and express themselves to others, freely. That’s why, deaf people seem to be used to accepting it, learn it, and use it. Not only deaf people, hearing people may use sign language in some situations, too. Disadvantages of sign language, on the other hand, can be related to the fact that it affects the use of spoken language. A sign language requires good face-to-face communication between the addresser and the addressee to deliver a message. The oral way of communication is unlike the sign one, and the latter may seem more difficult especially when taking into account the fact that sign language is not unified. This may cause a misunderstanding of some of its diverse vocabularies.

2.1 Analysis of case studies

This study aims to investigate the special educational system used to teach sign language for deaf and hard of hearing individuals and to see the problems during acquiring process. Moreover, it also explores the current situation of teaching sign language, challenges, and obstacles encountered by teachers using sign language with deaf and hard of hearing children inside the deaf school. This study also attempts to find out the effectiveness of the deaf special education from the perspective of deaf pupils, to figure out to what extent they are satisfied, to know if they face any problems during their learning process and if the educational level meets their needs or not.

Study population

The language acquired by teachers, pupils, and some other specialists in the field of deaf education, as for teachers, because they are the experienced and professionals in the field of teaching deaf children. They must be aware of their pupils knowledge, language progression, and the process of learning. They are able to determine the challenges which they may have encountered as well as the solutions needed to overcome such barriers to be able to teach them in better conditions as possible as it should be. Consequently, as a result, teachers in special deaf education will be able to achieve better performance of teaching inconvenient conditions that the deaf children need and to pave them the way to live as any hearing children inside regular schools. Pupils, on the other hand, come in the first place. They play a central role in special education. They are the ones whom the purpose of inclusive education does exist. Because of them, the researcher was able to shed, to some extent, some light on the benefit of such education and its effectiveness of it on their language progression, learning process, and their life in general. Since they are presently experiencing the process of learning used inside the school, they might have a clear awareness of different difficulties and obstacles they might have came across while learning in such a special educational system. They may have some views, strategies, or solutions which may help them to enhance their academic performance.

2.2.Relating theory and practise

This study was accomplished in the School of Hearing Impaired Children in Baku. The real and the official start of this school was until 1989. It was established to meet the needs of hearing-impaired children. According to the education adviser, the name of this deaf school has witnessed lots of changes. At first, this school was given the name of the deaf and mute youth`s school. Later on, it was changed to be named: the school of deaf and mute children. Finally, its name was modified to a school of hearing impaired children, which is known as the deaf community in Baku. It is a boarding school. It provides board and lodging to some students but allows others to attend during the day only, like a day school

Data collection procedures

Interviews and classroom direct observation were the ways used to collect data for this study. The first step was to seek permission from the supervisor and the Deaf Community School in Baku. Immediately after that, the researcher moved to the school of hearing-impaired children and met the head of the school personally and sought permission to carry out the study. Then the permission was accepted, the researcher met the therapist, pedagogical advisor, and teachers to introduce himself and to inform them about the purpose of his case study.

Meanwhile, the researcher started taking some observations through attending different classes with deaf pupils and interviewed the latter whenever possible. In such a way, gathering information throughout the observations was an attempt to compare, collect, and capture any other data needed for the study as far as possible and in order not to miss any information that might not have been provided in the interviews.

Methodology

To make sense of the data was collected through interviews and observations, the researcher the needed instruments were gathered for data coding and subsequent analysis. The data for this study was analyzed through detailed description and explanations which were being given by the respondents. To establish patterns, trends and relationships from the information gathered and to make the collected data easily interpreted by many people, basic quantitative statistical techniques such as frequencies, percentages, and tables were used.

The methodology of this project is ethnographic and qualitative research. Observation is method used by researcher Through this work in the community it was slowly accepted more and more. This is qualitative methodology that researcher decided to go and have observation. And there are some questionnaires used by researcher on this research paper.

When the case study revealed facts related to the training of teachers in sign language, we wanted to know the teachers` views about sign language. Thus, the ten teachers were asked about the nature of sign language,importance of learning of it, teaching it as a subject in classes, and whether the deaf children seem to learn enough sign language from the teachers as they teach them some other different contents or not.

Teachers` attitudes towards teaching of sign language. 50 percent of the teachers seems to believe that sign language is as natural as Azerbaijani or Turkish. It has its alphabets, vocabularies, and grammar. Only 2 out of 10 teachers state that unlike spoken languages (e.g. Azerbaijani), sign language is not natural. It is not even comparable, linguistically speaking. The number of teachers who responded by no represents a percentage of 20 percent. The 30 percent of teachers, however, gave no response at all related to the nature of sign language. These teachers were 3 in number. Some reasons given by teachers who have belief that sign language is natural were also asked by the researcher. A female teacher has 28 years of experience in teaching 40 illustrate that sign language is a natural language used by deaf children since the babbling stage, who learns his first signs from his mother. Whether we agreed or not, sign language is the deaf children`s mother tongue. So, it is natural, it has its linguistic features and grammar. Further, she said that she had been trained by deaf teachers who master the language very well. If the language was not natural, she could not have been able to acquire it, understand it, use it, and teach it. Another female teacher has only five months of experience in teaching the deaf argued that it is a natural language because no one can understand it unless he learns it. The answers to the second question that asks if the teachers are offering sign language as a taught subject in their classes reflected noticeable results concerning teaching sign language for the deaf. The vast majority of 90 percent of teachers answered by no. Almost all teachers were not offering sign language as a taught subject in the school. Only one male teacher, who has not mention his years of experience in teaching, says that he is offering it as a taught subject in his classes. The teacher claims that he has a specific class devoted only to sign language itself. In this class, he explains the content of the sign language dictionary used in the school to enrich his pupils’ vocabularies. The nine teachers, on the other hand, are not teaching sign language as a subject in the school. Two teachers say they are not offering it as a subject because it is just a means that the teacher uses to explain various content subjects like mathematics or history. Another teacher adds that it is not scheduled in the timetable to be taught as a subject itself. A male teacher has 26 years of experience in teaching that sign language is not scheduled as a taught subject because he relies on the curriculum

The grammar taught at this school follows the same grammar rules of the Azerbaijani language. However, some of these rules seem to be dropped in sign language. For instance in the first sentence and the second sentence the definite article “the“ is not used before the tow words “sign and baby“. Another thing was dropped which is the sign that represents the question mark in the second sentence. Although it might seem that the Azerbaijani language grammar is not entirely applicable, teachers follow it as an alternative in the absence of available sources to teach sign language and its real grammar that fits its linguistic features and nature.

Barriers and challenges to the teaching of sign language

Findings of this study indicate that there are some challenges and barriers encountered by deaf pupils and their teachers in particular. First, the results revealed that there is no Azerbaijani Sign Language in Baku neither any sign languages are being used in the school of hearing-impaired children. Second, there is a need for real sources of sign language, academically speaking. Also, there is lack of equipments in this school. Therefore, the school must be well equipped.

Many people who have no or minimal experience with sign language users, including parents of deaf children and the professionals who advise them, have fears about the difficulty of learning a sign language. Certainly, they might lack the resources or infrastructure to do so crucial but separate issue. What concerns us here is that they might initially assume they are incapable of learning to sign well enough to be able to help their child’s language development. The same paediatric audiologist’s websites mentioned earlier says, ‘Parents who do not know sign language well cannot provide a rich language environment for their child’. With little prior knowledge of signing , parents and professionals can be vulnerable to a bias against bringing a sign language into the lives of children who, in fact, could benefit greatly from sign language during a critical time for language and cognitive development. Surely, learning a second language as an adult is challenging, but no scholarly study has yet to find that sign languages are more difficult. Motivation is a crucial component in all second language learning, and parents who find themselves with a deaf child are likely to have strong motivation due to an impulse to communicate with their child in effective ways. The fear that parents can not learn to sign well enough to serve as good language models for their children should be put aside: parents do not have to be the most fluent signing models for their children. Deaf children, if exposed to good signing models outside the family, will learn to sign well even if their parents are less than fluent. Moreover, deaf children whose parents are able to communicate with them with sign language benefit in other ways: they use more complex language with one another with more positive outcome than those who do not sign at all, and they show early language expressiveness on a par with hearing children of the same age. With language learning support (a teacher, tutor, other signers, the child’s deaf peers and the parents), family members learning a sign language, for example, ASL or German Sign Language (DGS), at the same time as the deaf child, powerfully enhance family communication and promote a typical language acquisition process, which is key for the child’s lifelong success. S ign language, their children will drift away from the family and become part of a social world of deaf signers, a deaf culture.

The opposite has been shown to be true. Deaf children who grow up bilingually and can communicate with their parents in a sign language (and in a visual modality) are much more likely to have strong, healthy family ties than those deaf people who are unable to speak well or hear well enough to have communication with their parents because neither they nor their parents learned a sign language. There are reports indicating that some oral deaf people and hearing parents of deaf children wish they had had an opportunity to learn sign language earlier but were advised against doing so. One of the comments to the Post article on Di Marco ended with the bleak statement, ‘I was a victim of oral monolingual education’. In their social world (or shared culture), deaf people view themselves as whole, well and empowered. In contrast, the medical profession views deaf people as having a medical condition or pathology that they are obligated to address through medical means. Likewise, professions such as audiology and hearing sciences see it as their duty to provide treatments, therapies and interventions. Educators design pedagogy that is special or differentiated from that of other children. This combination of historical negative view of deaf people in society and the professions often communicates to parents that if they allow their deaf children to learn a sign language, their children will identify with this community and not the family.

Conclusion:

There are not a lot of researches about how icrucial Sign Language is for Deaf Community. Deaf of hearing people suffer from isolation from their own family when both they and their families do not have access to Sign Language. This lack of understanding creates rifts within the relationships, making it more difficult to communicate. This is avoidable by families being properly informed in the beginning and taking advantage of the multitude of free classes available. For those Deaf students who are in schools that do not use Sign Language may continue to have limited access to their education. The same issue exists for children who arrive at kindergarten with no language and have to start from the very beginning before they can begin acquiring knowledge. Communication with the hearing community is fraught with problems, but most of these conflicts stem from language and communication issues that could easily be solved. All of these negative experiences pale in comparison to the stories of the discovery of Sign Language. The joy, and finding of self described by individuals is an experience all Deaf people should have access to.

References:

- https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/american-sign-language

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

- http://www.signlanguage101.com/

- https://www.handspeak.com/

- https://www.lifeprint.com/

- https://mashable.com/article/how-to-sign/

- https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199935345-e-19

- https://en.wikipeia.org/wiki/Language_acquisition_by_deaf_children

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/_Sign_Language

- ttps://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1356&context=theses

- https://www.academia.edu/37430562/Teaching_sign_language_to_the_deaf_children_in_Adrar_Algeria._A_case_study_of_the_Hearing_Impaired_Childrens_School_in_Adrar

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_language#History

- https://www.google.az/search?ei=yo_qXKyvPKP1qwHX26KoBw&q=sign+language&oq=sign+language&gs_l=psy-ab.3..35i39l2j0l8.1937.4559..5618…0.0..0.147.1555.0j13……0….1..gws-wiz…….0i71.ysjSGH17X2c

- https://www.uncommongoods.com/product/american-sign-language-blocks?msclkid=a3159dd78feb17141efec13d1c2dc5fe#pr-reviewdisplay

- https://www.signingsavvy.com/

- https://www.learnwithadrienne.com/sign-language-in-30-days-online-course-for-beginners-registration

- https://www.signschool.com/

- https://www.perkinselearning.org/earn-credits/onsite-training/sign-language-classes

- https://jme.bmj.com/content/medethics/43/9/648.full.pdf

We have 98 writers available online to start working on your essay just NOW!

Related Topics

Related essays.

By clicking "Send essay" you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

By clicking "Receive essay" you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

We can edit this one and make it plagiarism-free in no time