Responding, Evaluating, Grading

Rubric for a Research Proposal

Matthew Pearson - Writing Across the Curriculum

UW-Madison WAC Sourcebook 2020 Copyright © by Matthew Pearson - Writing Across the Curriculum. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, appropriate criteria: key to effective rubrics.

- Department of Educational Foundations and Leadership, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

True rubrics feature criteria appropriate to an assessment's purpose, and they describe these criteria across a continuum of performance levels. The presence of both criteria and performance level descriptions distinguishes rubrics from other kinds of evaluation tools (e.g., checklists, rating scales). This paper reviewed studies of rubrics in higher education from 2005 to 2017. The types of rubrics studied in higher education to date have been mostly analytic (considering each criterion separately), descriptive rubrics, typically with four or five performance levels. Other types of rubrics have also been studied, and some studies called their assessment tool a “rubric” when in fact it was a rating scale. Further, for a few (7 out of 51) rubrics, performance level descriptions used rating-scale language or counted occurrences of elements instead of describing quality. Rubrics using this kind of language may be expected to be more useful for grading than for learning. Finally, no relationship was found between type or quality of rubric and study results. All studies described positive outcomes for rubric use.

A rubric articulates expectations for student work by listing criteria for the work and performance level descriptions across a continuum of quality ( Andrade, 2000 ; Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ). Thus, a rubric has two parts: criteria that express what to look for in the work and performance level descriptions that describe what instantiations of those criteria look like in work at varying quality levels, from low to high.

Other assessment tools, like rating scales and checklists, are sometimes confused with rubrics. Rubrics, checklists, and rating scales all have criteria; the scale is what distinguishes them. Checklists ask for dichotomous decisions (typically has/doesn't have or yes/no) for each criterion. Rating scales ask for decisions across a scale that does not describe the performance. Common rating scales include numerical scales (e.g., 1–5), evaluative scales (e.g., Excellent-Good-Fair-Poor), and frequency scales (e.g., Always, Usually-Sometimes-Never). Frequency scales are sometimes useful for ratings of behavior, but none of the rating scales offer students a description of the quality of their performance they can easily use to envision their next steps in learning. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the types of rubrics that have been studied in higher education.

Rubrics have been analyzed in several different ways. One important characteristic of rubrics is whether they are general or task-specific ( Arter and McTighe, 2001 ; Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ; Brookhart, 2013 ). General rubrics apply to a family of similar tasks (e.g., persuasive writing prompts, mathematics problem solving). For example, a general rubric for an essay on characterization might include a performance level description that reads, “Used relevant textual evidence to support conclusions about a character.” Task-specific rubrics specify the specific facts, concepts, and/or procedures that students' responses to a task should contain. For example, a task-specific rubric for the characterization essay might specify which pieces of textual evidence the student should have located and what conclusions the student should have drawn from this evidence. The generality of the rubric is perhaps the most important characteristic, because general rubrics can be shared with students and used for learning as well as for grading.

The prevailing hypothesis about how rubrics help students is that they make explicit both the expectations for student work and, more generally, describe what learning looks like ( Andrade, 2000 ; Arter and McTighe, 2001 ; Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ; Bell et al., 2013 ; Brookhart, 2013 ; Nordrum et al., 2013 ; Panadero and Jonsson, 2013 ). In this way, rubrics play a role in the formative learning cycle (Where am I going? Where am I now? Where to next? Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ) and support student agency and self-regulation ( Andrade, 2010 ). Some research has borne out this idea, showing that rubrics do make expectations explicit for students ( Jonsson, 2014 ; Prins et al., 2016 ) and that students do use rubrics for this purpose ( Andrade and Du, 2005 ; Garcia-Ros, 2011 ). General rubrics should be written with descriptive language, as opposed to evaluative language (e.g., excellent, poor) because descriptive language helps students envision where they are in their learning and where they should go next.

Another important way to characterize rubrics is whether they are analytic or holistic. Analytic rubrics consider criteria one at a time, which means they are better for feedback to students ( Arter and McTighe, 2001 ; Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ; Brookhart, 2013 ; Brookhart and Nitko, 2019 ). Holistic criteria consider all the criteria simultaneously, requiring only one decision on one scale. This means they are better for grading, for times when students will not need to use feedback, because making only one decision is quicker and less cognitively demanding than making several.

Rubrics have been characterized by the number of criteria and number of levels they use. The number of criteria should be linked to the intended learning outcome(s) to be assessed, and the number of levels should be related to the types of decisions that need to be made and to the number of reliable distinctions in student work that are possible and helpful.

Dawson (2017) recently summarized a set of 14 rubric design elements that characterize both the rubrics themselves and their use in context. His intent was to provide more precision to discussions about rubrics and to future research in the area. His 14 areas included: specificity, secrecy, exemplars, scoring strategy, evaluative criteria, quality levels, quality definitions, judgment complexity, users and uses, creators, quality processes, accompanying feedback information, presentation, and explanation. In Dawson's terms, this study focused on specificity, evaluative criteria, quality levels, quality definitions, quality processes, and presentation (how the information is displayed).

Four recent literature reviews on the topic of rubrics ( Jonsson and Svingby, 2007 ; Reddy and Andrade, 2010 ; Panadero and Jonsson, 2013 ; Brookhart and Chen, 2015 ) summarize research on rubrics. Brookhart and Chen (2015) updated Jonsson and Svingby's (2007) comprehensive literature review. Panadero and Jonsson (2013) specifically addressed the use of rubrics in formative assessment and the fact that formative assessment begins with students understanding expectations. They posited that rubrics help improve student learning through several mechanisms (p. 138): increasing transparency, reducing anxiety, aiding the feedback process, improving student self-efficacy, or supporting student Self-regulation.

Reddy and Andrade (2010) addressed the use of rubrics in post-secondary education specifically. They noted that rubrics have the potential to identify needs in courses and programs, and have been found to support learning (although not in all studies). The found that the validity and reliability of rubrics can be established, but this is not always done in higher education applications of rubrics. Finally, they found that some higher education faculty may resist the use of rubrics, which may be linked to a limited understanding of the purposes of rubrics. Students generally perceive that rubrics serve purposes of learning and achievement, while some faculty members think of rubrics primarily as grading schemes (p. 439). In fact, rubrics are not as easy to use for grading as some traditional rating or point schemes; the reason to use rubrics is that they can support learning and align learning with grading.

Some criticisms and challenges for rubrics have been noted. Nordrum et al. (2013) summarized words of caution from several scholars about the potential for the criteria used in rubrics to be subjective or vague, or to narrow students' understandings of learning (see also Torrance, 2007 ). In a backhanded way, these criticisms support the thesis of this review, namely, that appropriate criteria are the key to the effectiveness of a rubric. Such criticisms are reasonable and get their traction from the fact that many ineffective or poor-quality rubrics exist, that do have vague or narrow criteria. A particularly dramatic example of this happens when the criteria in a rubric are about following the directions for an assignment rather than describing learning (e.g., “has three sources” rather than “uses a variety of relevant, credible sources”). Rubrics of this kind misdirect student efforts and mis-measure learning.

Sadler (2014) argued that codification of qualities of good work into criteria cannot mean the same thing in all contexts and cannot be specific enough to guide student thinking. He suggests instantiation instead of codification, describing a process of induction where the qualities of good work are inferred from a body of work samples. In fact, this method is already used in classrooms when teachers seek to clarify criteria for rubrics ( Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ) or when teachers co-create rubrics with students ( Andrade and Heritage, 2017 ).

Purpose of the Study

A number of scholars have published studies of the reliability, validity, and/or effectiveness of rubrics in higher education and provided the rubrics themselves for inspection. This allows for the investigation of several research questions, including:

(1) What are the types and quality of the rubrics studied in higher education?

(2) Are there any relationships between the type and quality of these rubrics and reported reliability, validity, and/or effects on learning and motivation?

Question 1 was of interest because, after doing the previous review ( Brookhart and Chen, 2015 ), I became aware that not all of the assessment tools in studies that claimed to be about rubrics were characterized by both criteria and performance level descriptions, as for true rubrics ( Andrade, 2000 ). The purpose of Research Question 1 was simply to describe the distribution of assessment tool types in a systematic manner.

Question 2 was of interest from a learning perspective. Various types of assessment tools can be used reliably ( Brookhart and Nitko, 2019 ) and be valid for specific purposes. An additional claim, however, is made about true rubrics. Because the performance level descriptions describe performance across a continuum of work quality, rubrics are intended to be useful for students' learning ( Andrade, 2000 ; Brookhart, 2013 ). The criteria and performance level descriptions, together, can help students conceptualize their learning goal, focus on important aspects of learning and performance, and envision where they are in their learning and what they should try to improve ( Falchikov and Boud, 1989 ). Thus I hypothesized that there would not be a relationship between type of rubric and conventional reliability and validity evidence. However, I did expect a relationship between type of rubric and the effects of rubrics on learning and motivation, expecting true descriptive rubrics to support student learning better than the other types of tools.

This study is a literature review. Study selection began with the data base of studies selected for Brookhart and Chen (2015) , a previous review of literature on rubrics from 2005 to 2013. Thirty-six studies from that review were done in the context of higher education. I conducted an electronic search for articles published from 2013 to 2017 in the ERIC database. This yielded 10 additional studies, for a total of 46 studies. The 46 studies have the following characteristics: (a) conducted in higher education, (b) studied the rubrics (i.e., did not just use the rubrics to study something else, or give a description of “how-to-do-rubrics”), and (c) included the rubrics in the article.

There are two reasons for limiting the studies to the higher education context. One, most published studies of rubrics have been conducted in higher education. I do not think this means fewer rubrics are being used in the K-12 context; I observe a lot of rubric use in K-12. Higher education users, however, are more likely to do a formal review of some kind and publish their results. Thus the number of available studies was large enough to support a review. Two, given that more published information on rubrics exists in higher education than K-12, limiting the review to higher education holds constant one possible source of complexity in understanding rubric use, because all of the students are adult learners. Rubrics used with K-12 students must be written at an appropriate developmental or educational level. The reason for limiting the studies to ones that included a copy of the rubrics in the article was that the analysis for this review required classifying the type and characteristics of the rubrics themselves.

Information about the 46 studies was entered into a spreadsheet. Information noted about the studies included country, level (undergraduate or graduate), type (rubric, rating scale, or point scheme), how the rubric considered criteria (analytic or holistic), whether the performance level descriptors were truly descriptive or used rating scale and/or numerical language in the levels, type of construct assessed by the rubrics (cognitive or behavioral), whether the rubrics were used with students or just by instructors for grading, sample, study method (e.g., case study, quasi-experimental), and findings. Descriptive and summary information about these classifications and study descriptions was used to address the research questions.

As an example of what is meant by descriptive language in a rubric, consider this excerpt from Prins et al. (2016) . This is the performance level description for Level 3 of the criterion Manuscript Structure from a rubric for research theses (p. 133):

All elements are logically connected and keypoints within sections are organized. Research questions, hypotheses, research design, results, inferences and evaluations are related and form a consistent and concise argumentation.

Notice that a key characteristic of the language in this performance level description is that it describes the work. Thus for students who aspire to this high level, the rubric depicts for them what their work needs to look like in order to reach that goal.

In contrast, if performance level descriptions are written in evaluative language (for example, if the performance level description above had read, “The paper shows excellent manuscript structure”), the rubric does not give students the information they need to further their learning. Rubrics written in evaluative language do not give students a depiction of work at that level and, therefore, do not provide a clear description of the learning goal. An example of evaluative language used in a rubric can be found in the performance level descriptions for one of the criteria of an oral communication rubric ( Avanzino, 2010 , p. 109). This is the performance level description for Level 2 (Adequate) on the criterion of Delivery:

Speaker's delivery style/use of notes (manuscript or extemporaneous) is average; inconsistent focus on audience.

Notice that the key word in the first part of the performance level description, “average,” does not give any information to the student about what average delivery looks like in regard to style and use of notes. The second part of the performance level description, “inconsistent focus on audience,” is descriptive and gives students information about what Level 2 performance looks like in regard to audience focus.

Results and Discussion

The 46 studies yielded 51 different rubrics because several studies included more than one rubric. The two sections below take up results for each research question in turn.

Type and Quality of Rubrics

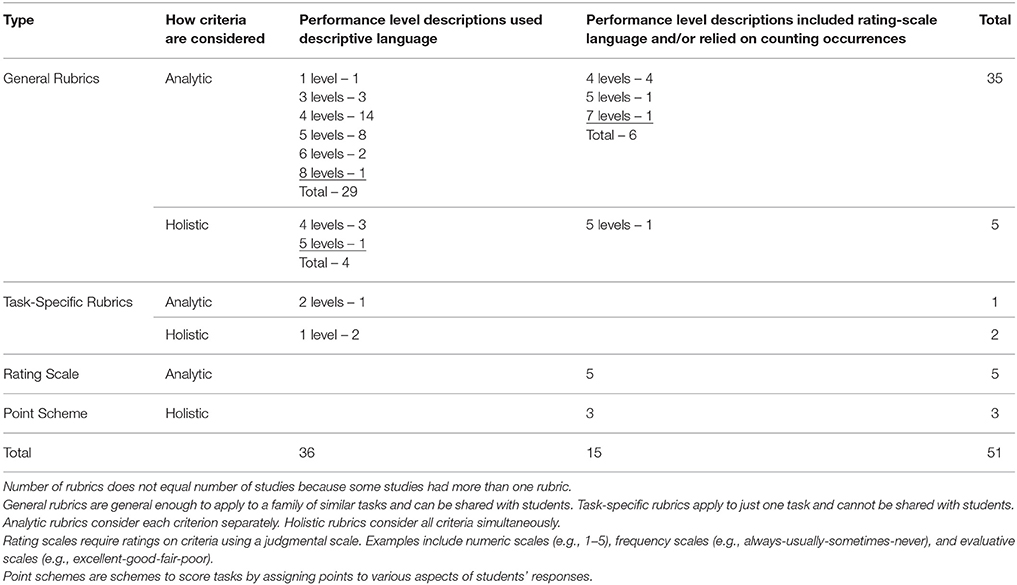

Table 1 displays counts of the type and quality of rubrics found in the studies. Most of the rubrics (29 out of 51, 57%) were analytic, descriptive rubrics. This means they considered the criteria separately, requiring a separate decision about work quality for each criterion. In addition, it means that the performance level descriptions used descriptive, as opposed to evaluative, language, which is expected to be more supportive of learning. Most commonly, these rubrics described four (14) or five (8) performance levels.

Table 1 . Types of rubrics used in studies of rubrics in higher education.

Four of the 51 rubrics (8%) were holistic, descriptive rubrics. This means they considered the criteria simultaneously, requiring one decision about work quality across all criteria at once. In addition, the performance level descriptions used the desired descriptive language.

Three of the rubrics were descriptive and task-specific. One of these was an analytic rubric and two were holistic rubrics. None of the three could be shared with students, because they would “give away” answers. Such rubrics are more useful for grading than for formative assessment supporting learning. This does not necessarily mean the rubrics were not of quality, because they served well the grading function for which they were designed. However, they represent a missed opportunity to support learning as well as grading.

A few of the rubrics were not written in a descriptive manner. Six of the analytic rubrics and one of the holistic rubrics used rating scale language and/or listed counts of occurrences of elements in the work, instead of describing the quality of student learning and performance. Thus 7 out of 51 (14%) of the rubrics were not of the quality that is expected to be best for student learning ( Arter and McTighe, 2001 ; Arter and Chappuis, 2006 ; Andrade, 2010 ; Brookhart, 2013 ).

Finally, eight of the 51 rubrics (16%) were not rubrics but rather rating scales (5) or point schemes for grading (3). It is possible that the authors were not aware of the more nuanced meaning of “rubric” currently used by educators and used the term in a more generic way to mean any scoring scheme.

As the heart of Research Question 1 was about the potential of the rubrics used to contribute to student learning, I also coded the studies according to whether the rubrics were used with students or whether they were just used by instructors for grading. Of the 46 studies, 26 (56%) reported using the rubrics with students and 20 (43%) did not use rubrics with students but rather used them only for grading.

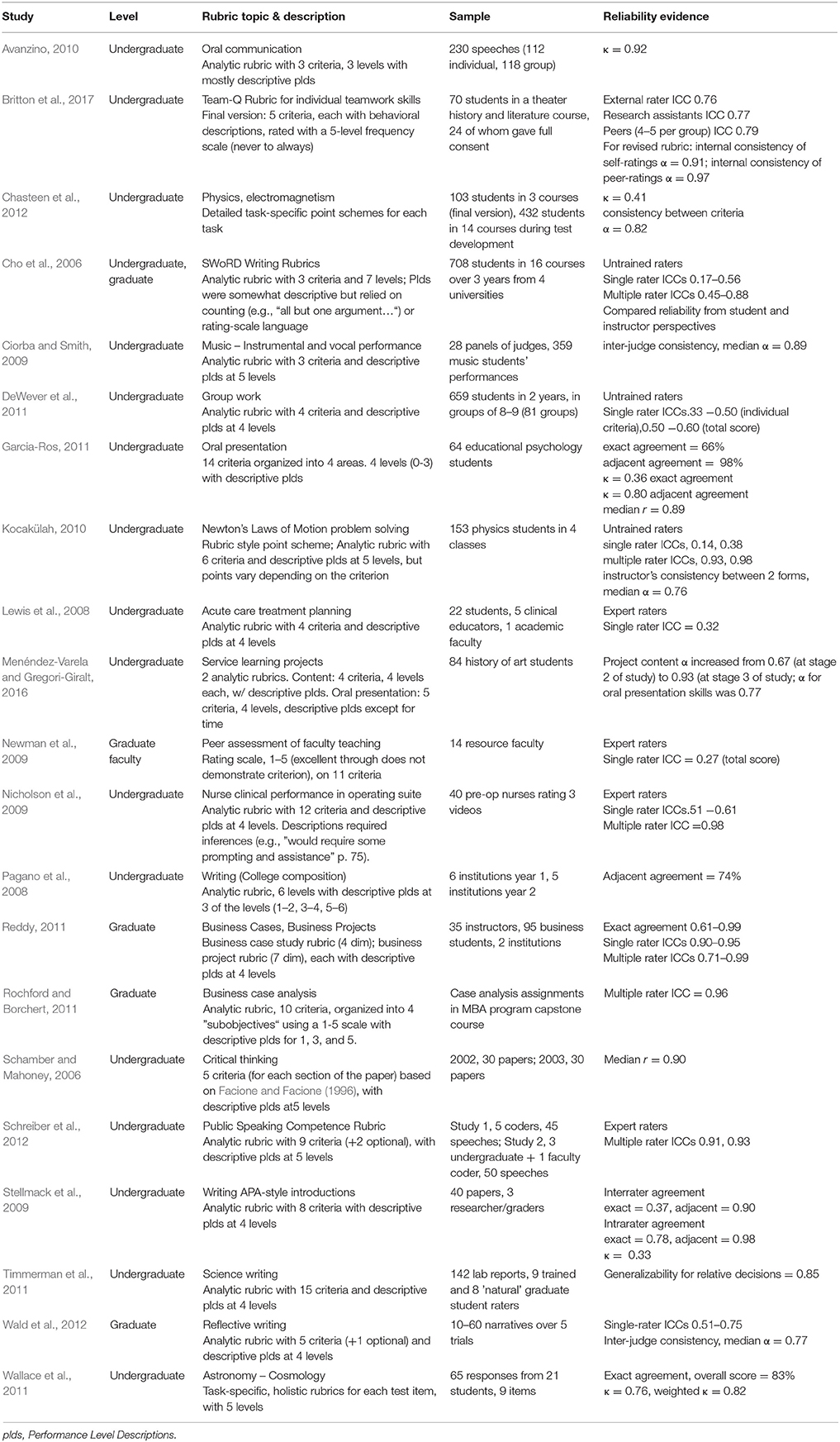

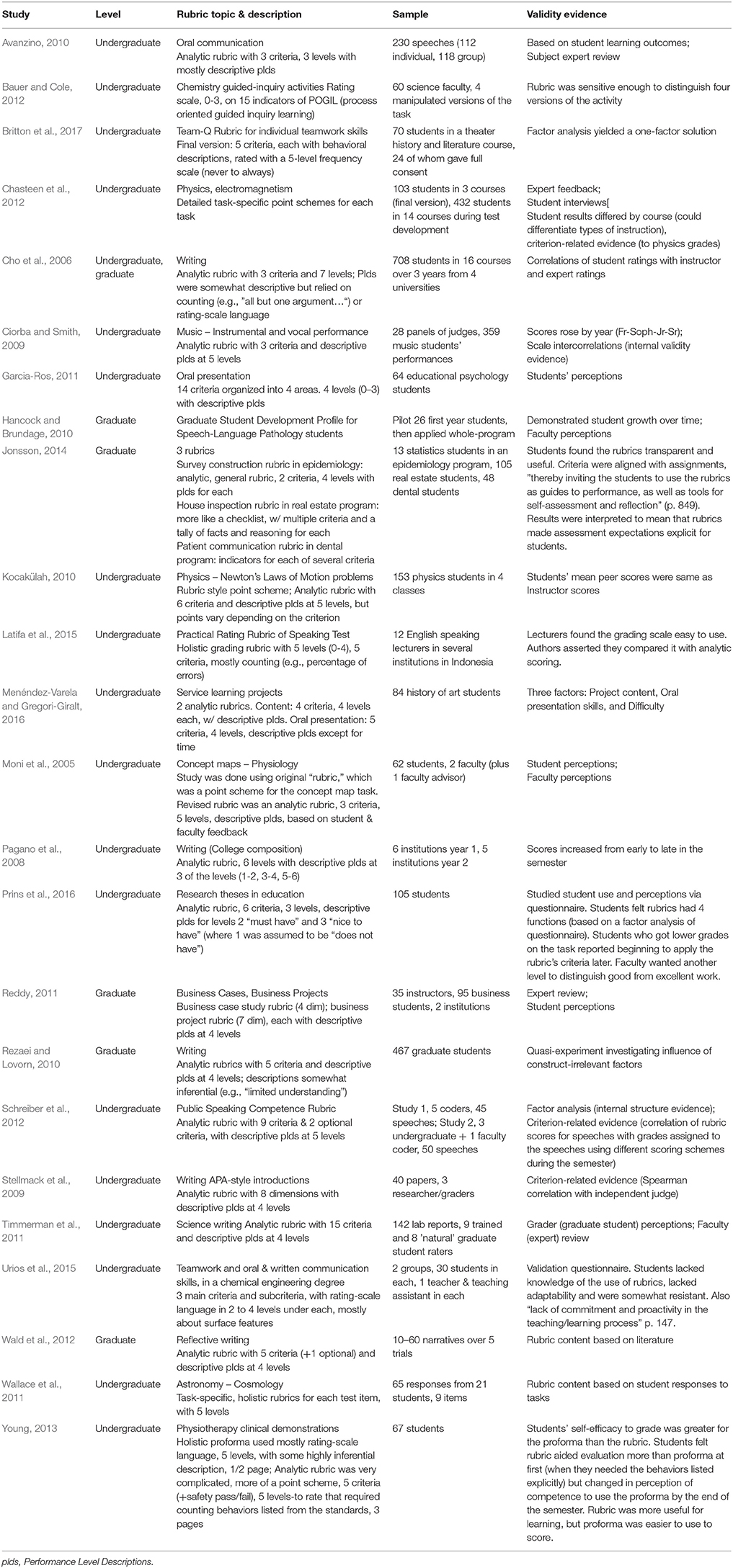

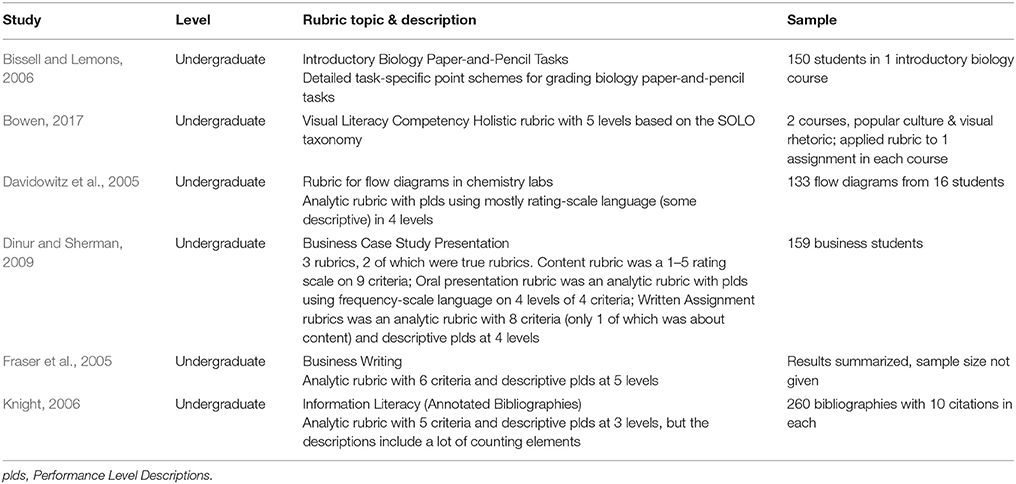

Relation of Rubric Type to Reliability, Validity, and Learning

Different studies reported different characteristics of their rubrics. I charted studies that reported evidence for the reliability of information from rubrics (Table 2 ) and the validity of information from rubrics (Table 3 ). For the sake of completeness, Table 4 lists six studies that presented their work with rubrics in a descriptive case-study style that did not fit easily into Table 2 or Table 3 or in Table 5 (below) about the effects of rubrics on learning. With the inclusion of Table 4 , readers have descriptions of all 51 rubrics in all 46 studies reported under Research Question 1.

Table 2 . Reliability evidence for rubrics.

Table 3 . Validity evidence for rubrics.

Table 4 . Descriptive case studies about developing and using rubrics.

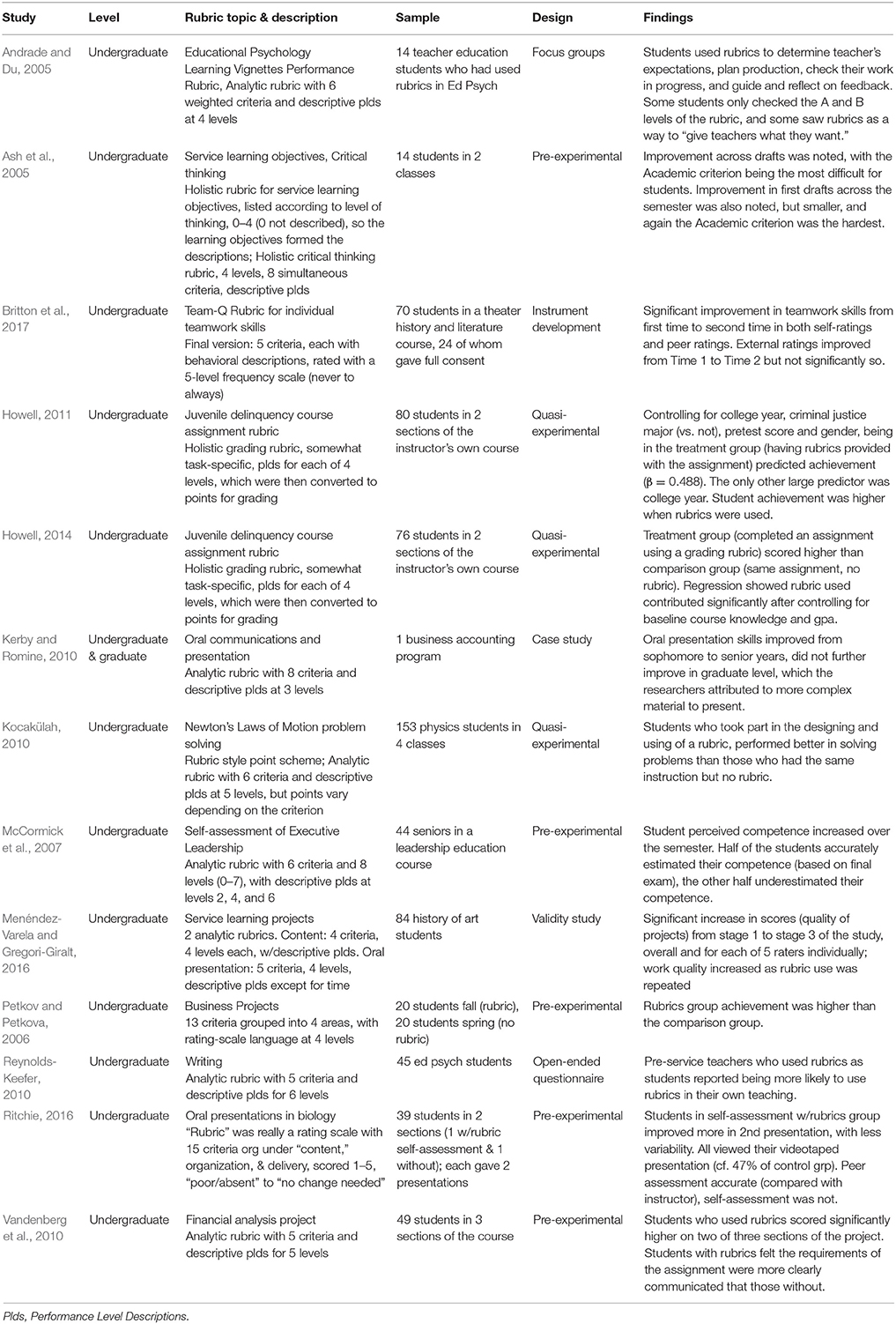

Table 5 . Studies of the effects of rubric use on student learning and motivation to learn.

Reliability was most commonly studied as inter-rater reliability, arguably the most important for rubrics because judgment is involved in matching student work with performance level descriptions, or as internal consistency among criteria. Construct validity was addressed with a variety of methods, from expert review to factor analysis; some studies also addressed consequential evidence for validity with student or faculty questionnaires. No discernable patterns were found that indicated one form of rubric was preferable to another in regard to reliability or validity. Although this conforms to my hypothesis, this result is also partly because most of the studies' reported results and experience with rubrics were positive, no matter what type of rubric was used.

Table 5 describes 13 studies of the effects of rubrics on learning or motivation, all with positive results. Learning was most commonly operationalized as improvement in student work. Motivation was typically operationalized as student responses to questionnaires. In these studies as well, no discernable pattern was found regarding type of rubric. Despite the logical and learning-based arguments made in the literature and summarized in the introduction to this article, rubrics with both descriptive and evaluative performance level descriptions both led to at least some positive results for students. Eight of these studies used descriptive rubrics and five used evaluative rubrics. It is possible that the lack of association of type of rubric with study findings is a result of publication bias, because most of the studies had good things to say about rubrics and their effects. The small sample size (13 studies) may also be an issue.

Conclusions

Rubrics are becoming more and more evident as part of assessment in higher education. Evidence for that claim is simply the number of studies that are published investigating this new and growing interest and the assertions made in those studies about rising interest in rubrics.

Research Question 1 asked about the type and quality of rubrics published in studies of rubrics in higher education. The number of criteria varies widely depending on the rubric and its purpose. Three, four, and five are the most common number of levels. While most of the rubrics are descriptive—the type of rubrics generally expected to be most useful for learning—many are not. Perhaps most surprising, and potentially troubling, is that only 56% of the studies reported using rubrics with students. If all that is required is a grading scheme, traditional point schemes or rating scales are easier for instructors to use. The value of a rubric lies in its formative potential ( Panadero and Jonsson, 2013 ), where the same tool that students can use to learn and monitor their learning is then used for grading and final evaluation by instructors.

Research Question 2 asked whether rubric type and quality were related to measurement quality (reliability and validity) or effects on learning and motivation to learn. Among studies in this review, reported reliability and validity was not related to type of rubric. Reported effects on learning and/or motivation were not related to type of rubric. The discussion above speculated that part of the reason for these findings might be publication bias, because only studies with good effects—whatever the type of rubric they used—were reported.

However, we should not dismiss all the results with a hand-wave about publication bias. All of the tools in the studies of rubrics—true rubrics, rating scales, checklists—had criteria. The differences were in the type of scale and scale descriptions used. Criteria lay out for students and instructors what is expected in student work and, by extension, what it looks like when evidence of intended learning has been produced. Several of the articles stated explicitly that the point of rubrics was to make assignment expectations explicit (e.g., Andrade and Du, 2005 ; Fraser et al., 2005 ; Reynolds-Keefer, 2010 ; Vandenberg et al., 2010 ; Jonsson, 2014 ; Prins et al., 2016 ). The criteria are the assignment expectations: the qualities the final work should display. The performance level descriptions instantiate those expectations at different levels of competence. Thus, one firm conclusion from this review is that appropriate criteria are the key to effective rubrics. Trivial or surface-level criteria will not draw learning goals for students as clearly as substantive criteria. Students will try to produce what is expected of them. If the criterion is simply having or counting something in their work (e.g., “has 5 paragraphs”), students need not pay attention to the quality of what their work has. If the criterion is substantive (e.g., “states a compelling thesis”), attention to quality becomes part of the work.

It is likely that appropriate performance level descriptions are also key for effective rubrics, but this review did not establish this fact. A major recommendation for future research is to design studies that investigate how students use the performance level descriptions as they work, in monitoring their work, and in their self-assessment judgments. Future research might also focus on two additional characteristics of rubrics ( Dawson, 2017 ): users and uses and judgment complexity. Several studies in this review established that students use rubrics to make expectations explicit. However, in only 56% of the studies were rubrics used with students, thus missing the opportunity to take advantage of this important rubric function. Therefore, it seems important to seek additional understanding of users and uses of rubrics. In this review, judgment complexity was a clear issue for one study ( Young, 2013 ). In that study, a complex rubric was found more useful for learning, but a holistic rating scale was easier to use once the learning had occurred. This hint from one study suggests that different degrees of judgment complexity might be more useful in different stages of learning.

Rubrics are one way to make learning expectations explicit for learners. Appropriate criteria are key. More research is needed that establishes how performance level descriptions function during learning and, more generally, how students use rubrics for learning, not just that they do.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Andrade, H. G. (2000). Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational Leadership 57, 13–18. Available online at: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb00/vol57/num05/Using-Rubrics-to-Promote-Thinking-and-Learning.aspx

Google Scholar

Andrade, H., and Du, Y. (2005). Student perspectives on rubric-referenced assessment. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10, 1–11. Available online at: http://pareonline.net/pdf/v10n3.pdf

Andrade, H., and Heritage, M. (2017). Using Assessment to Enhance Learning, Achievement, and Academic Self-Regulation . New York, NY: Routledge.

Andrade, H. L. (2010). “Students as the definitive source of formative assessment: academic self-assessment and the self-regulation of learning,” in Handbook of Formative Assessment , eds H. L. Andrade and G. J. Cizek (New York, NY: Routledge), 90–105.

Arter, J. A., and Chappuis, J. (2006). Creating and Recognizing Quality Rubrics . Boston: Pearson.

Arter, J. A., and McTighe, J. (2001). Scoring Rubrics in the Classroom: Using Performance Criteria for Assessing and Improving Student Performance . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Ash, S. L., Clayton, P. H., and Atkinson, M. P. (2005). Integrating reflection and assessment to capture and improve student learning. Mich. J. Comm. Serv. Learn. 11, 49–60. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0011.204

Avanzino, S. (2010). Starting from scratch and getting somewhere: assessment of oral communication proficiency in general education across lower and upper division courses. Commun. Teach. 24, 91–110. doi: 10.1080/17404621003680898

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bauer, C. F., and Cole, R. (2012). Validation of an assessment rubric via controlled modification of a classroom activity. J. Chem. Educ. 89, 1104–1108. doi: 10.1021/ed2003324

Bell, A., Mladenovic, R., and Price, M. (2013). Students' perceptions of the usefulness of marking guides, grade descriptors and annotated exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 769–788. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.714738

Bissell, A. N., and Lemons, P. R. (2006). A new method for assessing critical thinking in the classroom. BioScience , 56, 66–72. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0066:ANMFAC]2.0.CO;2

Bowen, T. (2017). Assessing visual literacy: a case study of developing a rubric for identifying and applying criteria to undergraduate student learning. Teach. High. Educ. 22, 705–719. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2017.1289507

Britton, E., Simper, N., Leger, A., and Stephenson, J. (2017). Assessing teamwork in undergraduate education: a measurement tool to evaluate individual teamwork skills. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 378–397. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1116497

Brookhart, S. M. (2013). How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Brookhart, S. M., and Chen, F. (2015). The quality and effectiveness of descriptive rubrics. Educ. Rev. 67, 343–368. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2014.929565

Brookhart, S. M., and Nitko, A. J. (2019). Educational Assessment of Students, 8th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Chasteen, S. V., Pepper, R. E., Caballero, M. D., Pollock, S. J., and Perkins, K. K. (2012). Colorado Upper-Division Electrostatics diagnostic: a conceptual assessment for the junior level. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Phys. Educ. Res. 8:020108. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.8.020108

Cho, K., Schunn, C. D., and Wilson, R. W. (2006). Validity and reliability of scaffolded peer assessment of writing from instructor and student perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 891–901. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.891

Ciorba, C. R., and Smith, N. Y. (2009). Measurement of instrumental and vocal undergraduate performance juries using a multidimensional assessment rubric. J. Res. Music Educ. 57, 5–15. doi: 10.1177/0022429409333405

Davidowitz, B., Rollnick, M., and Fakudze, C. (2005). Development and application of a rubric for analysis of novice students' laboratory flow diagrams. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 27, 43–59. doi: 10.1080/0950069042000243754

Dawson, P. (2017). Assessment rubrics: towards clearer and more replicable design, research and practice. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 347–360. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1111294

DeWever, B., Van Keer, H., Schellens, T., and Valke, M. (2011). Assessing collaboration in a wiki: the reliability of university students' peer assessment. Internet High. Educ. 14, 201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.07.003

Dinur, A., and Sherman, H. (2009). Incorporating outcomes assessment and rubrics into case instruction. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 10, 291–311.

Facione, N. C., and Facione, P. A. (1996). Externalizing the critical thinking in knowledge development and clinical judgment. Nurs. Outlook 44, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/S0029-6554(06)80005-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Falchikov, N., and Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in higher education: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 59, 395–430.

Fraser, L., Harich, K., Norby, J., Brzovic, K., Rizkallah, T., and Loewy, D. (2005). Diagnostic and value-added assessment of business writing. Bus. Commun. Q. 68, 290–305. doi: 10.1177/1080569905279405

Garcia-Ros, R. (2011). Analysis and validation of a rubric to assess oral presentation skills in university contexts. Electr. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 9, 1043–1062.

Hancock, A. B., and Brundage, S. B. (2010). Formative feedback, rubrics, and assessment of professional competency through a speech-language pathology graduate program. J. All. Health , 39, 110–119.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Howell, R. J. (2011). Exploring the impact of grading rubrics on academic performance: findings from a quasi-experimental, pre-post evaluation. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 22, 31–49.

Howell, R. J. (2014). Grading rubrics: hoopla or help? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 51, 400–410. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2013.785252

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 840–852. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.875117

Jonsson, A., and Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational consequences. Educ. Res. Rev. 2, 130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2007.05.002

Kerby, D., and Romine, J. (2010). Develop oral presentation skills through accounting curriculum design and course-embedded assessment. Journal of Education for Business , 85, 172–179. doi: 10.1080/08832320903252389

Knight, L. A. (2006). Using rubrics to assess information literacy. Ref. Serv. Rev. 34, 43–55. doi: 10.1108/00907320610640752

Kocakülah, M. (2010). Development and application of a rubric for evaluating students' performance on Newton's Laws of Motion. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 19, 146–164. doi: 10.1007/s10956-009-9188-9

Latifa, A., Rahman, A., Hamra, A., Jabu, B., and Nur, R. (2015). Developing a practical rating rubric of speaking test for university students of English in Parepare, Indonesia. Engl. Lang. Teach. 8, 166–177. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n6p166

Lewis, L. K., Stiller, K., and Hardy, F. (2008). A clinical assessment tool used for physiotherapy students—is it reliable? Physiother. Theory Pract. 24, 121–134. doi: 10.1080/09593980701508894

McCormick, M. J., Dooley, K. E., Lindner, J. R., and Cummins, R. L. (2007). Perceived growth versus actual growth in executive leadership competencies: an application of the stair-step behaviorally anchored evaluation approach. J. Agric. Educ. 48, 23–35. doi: 10.5032/jae.2007.02023

Menéndez-Varela, J., and Gregori-Giralt, E. (2016). The contribution of rubrics to the validity of performance assessment: a study of the conservation-restoration and design undergraduate degrees. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 228–244. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.998169

Moni, R. W., Beswick, E., and Moni, K. B. (2005). Using student feedback to construct an assessment rubric for a concept map in physiology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 29, 197–203. doi: 10.1152/advan.00066.2004

Newman, L. R., Lown, B. A., Jones, R. N., Johansson, A., and Schwartzstein, R. M. (2009). Developing a peer assessment of lecturing instrument: lessons learned. Acad. Med. 84, 1104–1110. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad18f9

Nicholson, P., Gillis, S., and Dunning, A. M. (2009). The use of scoring rubrics to determine clinical performance in the operating suite. Nurse Educ. Today 29, 73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.06.011

Nordrum, L., Evans, K., and Gustafsson, M. (2013). Comparing student learning experiences of in-text commentary and rubric-articulated feedback: strategies for formative assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 919–940. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.758229

Pagano, N., Bernhardt, S. A., Reynolds, D., Williams, M., and McCurrie, M. (2008). An inter-institutional model for college writing assessment. Coll. Composition Commun. 60, 285–320.

Panadero, E., and Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: a review. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Petkov, D., and Petkova, O. (2006). Development of scoring rubrics for IS projects as an assessment tool. Issues Informing Sci. Inform. Technol. 3, 499–510. doi: 10.28945/910

Prins, F. J., de Kleijn, R., and van Tartwijk, J. (2016). Students' use of a rubric for research theses. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 128–150. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1085954

Reddy, M. Y. (2011). Design and development of rubrics to improve assessment outcomes: a pilot study in a master's level Business program in India. Qual. Assur. Educ. 19, 84–104. doi: 10.1108/09684881111107771

Reddy, Y., and Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 435–448. doi: 10.1080/02602930902862859

Reynolds-Keefer, L. (2010). Rubric-referenced assessment in teacher preparation: an opportunity to learn by using. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 15, 1–9. Available online at: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=15&n=8

Rezaei, A., and Lovorn, M. (2010). Reliability and validity of rubrics for assessment through writing. Assess. Writing , 15, 18–39. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2010.01.003

Ritchie, S. M. (2016). Self-assessment of video-recorded presentations: does it improve skills? Act. Learn. High. Educ. 17, 207–221. doi: 10.1177/1469787416654807

Rochford, L., and Borchert, P. S. (2011). Assessing higher level learning: developing rubrics for case analysis. J. Educ. Bus. 86, 258–265. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2010.512319

Sadler, D. R. (2014). The futility of attempting to codify academic achievement standards. High. Educ. 67, 273–288. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9649-1

Schamber, J. F., and Mahoney, S. L. (2006). Assessing and improving the quality of group critical thinking exhibited in the final projects of collaborative learning groups. J. Gen. Educ. 55, 103–137. doi: 10.1353/jge.2006.0025

Schreiber, L. M., Paul, G. D., and Shibley, L. R. (2012). The development and test of the public speaking competence rubric. Commun. Educ. 61, 205–233. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2012.670709

Stellmack, M. A., Konheim-Kalkstein, Y. L., Manor, J. E., Massey, A. R., and Schmitz, J. P. (2009). An assessment of reliability and validity of a rubric for grading APA-style introductions. Teach. Psychol. 36, 102–107. doi: 10.1080/00986280902739776

Timmerman, B. E. C., Strickland, D. C., Johnson, R. L., and Payne, J. R. (2011). Development of a ‘universal’ rubric for assessing undergraduates' scientific reasoning skills using scientific writing. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 509–547. doi: 10.1080/02602930903540991

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assess. Educ. 14, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/09695940701591867

Urios, M. I., Rangel, E. R., Tomàs, R. B., Salvador, J. T., Garci,á, F. C., and Piquer, C. F. (2015). Generic skills development and learning/assessment process: use of rubrics and student validation. J. Technol. Sci. Educ. 5, 107–121. doi: 10.3926/jotse.147

Vandenberg, A., Stollak, M., McKeag, L., and Obermann, D. (2010). GPS in the classroom: using rubrics to increase student achievement. Res. High. Educ. J. 9, 1–10. Available online at: http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/10522.pdf

Wald, H. S., Borkan, J. M., Taylor, J. S., Anthony, D., and Reis, S. P. (2012). Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad. Med. 87, 41–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa

Wallace, C. S., Prather, E. E., and Duncan, D. K. (2011). A study of general education Astronomy students' understandings of cosmology. Part II. Evaluating four conceptual cosmology surveys: a classical test theory approach. Astron. Educ. Rev. 10:010107. doi: 10.3847/AER2011030

Young, C. (2013). Initiating self-assessment strategies in novice physiotherapy students: a method case study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 998–1011. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.771255

Keywords: criteria, rubrics, performance level descriptions, higher education, assessment expectations

Citation: Brookhart SM (2018) Appropriate Criteria: Key to Effective Rubrics. Front. Educ . 3:22. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00022

Received: 01 February 2018; Accepted: 27 March 2018; Published: 10 April 2018.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2018 Brookhart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan M. Brookhart, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Transparency in Assessment – Exploring the Influence of Explicit Assessment Criteria

Rubric for a Research Proposal

Matthew pearson, writing across the curriculum.

Rubric Design

Main navigation, articulating your assessment values.

Reading, commenting on, and then assigning a grade to a piece of student writing requires intense attention and difficult judgment calls. Some faculty dread “the stack.” Students may share the faculty’s dim view of writing assessment, perceiving it as highly subjective. They wonder why one faculty member values evidence and correctness before all else, while another seeks a vaguely defined originality.

Writing rubrics can help address the concerns of both faculty and students by making writing assessment more efficient, consistent, and public. Whether it is called a grading rubric, a grading sheet, or a scoring guide, a writing assignment rubric lists criteria by which the writing is graded.

Why create a writing rubric?

- It makes your tacit rhetorical knowledge explicit

- It articulates community- and discipline-specific standards of excellence

- It links the grade you give the assignment to the criteria

- It can make your grading more efficient, consistent, and fair as you can read and comment with your criteria in mind

- It can help you reverse engineer your course: once you have the rubrics created, you can align your readings, activities, and lectures with the rubrics to set your students up for success

- It can help your students produce writing that you look forward to reading

How to create a writing rubric

Create a rubric at the same time you create the assignment. It will help you explain to the students what your goals are for the assignment.

- Consider your purpose: do you need a rubric that addresses the standards for all the writing in the course? Or do you need to address the writing requirements and standards for just one assignment? Task-specific rubrics are written to help teachers assess individual assignments or genres, whereas generic rubrics are written to help teachers assess multiple assignments.

- Begin by listing the important qualities of the writing that will be produced in response to a particular assignment. It may be helpful to have several examples of excellent versions of the assignment in front of you: what writing elements do they all have in common? Among other things, these may include features of the argument, such as a main claim or thesis; use and presentation of sources, including visuals; and formatting guidelines such as the requirement of a works cited.

- Then consider how the criteria will be weighted in grading. Perhaps all criteria are equally important, or perhaps there are two or three that all students must achieve to earn a passing grade. Decide what best fits the class and requirements of the assignment.

Consider involving students in Steps 2 and 3. A class session devoted to developing a rubric can provoke many important discussions about the ways the features of the language serve the purpose of the writing. And when students themselves work to describe the writing they are expected to produce, they are more likely to achieve it.

At this point, you will need to decide if you want to create a holistic or an analytic rubric. There is much debate about these two approaches to assessment.

Comparing Holistic and Analytic Rubrics

Holistic scoring .

Holistic scoring aims to rate overall proficiency in a given student writing sample. It is often used in large-scale writing program assessment and impromptu classroom writing for diagnostic purposes.

General tenets to holistic scoring:

- Responding to drafts is part of evaluation

- Responses do not focus on grammar and mechanics during drafting and there is little correction

- Marginal comments are kept to 2-3 per page with summative comments at end

- End commentary attends to students’ overall performance across learning objectives as articulated in the assignment

- Response language aims to foster students’ self-assessment

Holistic rubrics emphasize what students do well and generally increase efficiency; they may also be more valid because scoring includes authentic, personal reaction of the reader. But holistic sores won’t tell a student how they’ve progressed relative to previous assignments and may be rater-dependent, reducing reliability. (For a summary of advantages and disadvantages of holistic scoring, see Becker, 2011, p. 116.)

Here is an example of a partial holistic rubric:

Summary meets all the criteria. The writer understands the article thoroughly. The main points in the article appear in the summary with all main points proportionately developed. The summary should be as comprehensive as possible and should be as comprehensive as possible and should read smoothly, with appropriate transitions between ideas. Sentences should be clear, without vagueness or ambiguity and without grammatical or mechanical errors.

A complete holistic rubric for a research paper (authored by Jonah Willihnganz) can be downloaded here.

Analytic Scoring

Analytic scoring makes explicit the contribution to the final grade of each element of writing. For example, an instructor may choose to give 30 points for an essay whose ideas are sufficiently complex, that marshals good reasons in support of a thesis, and whose argument is logical; and 20 points for well-constructed sentences and careful copy editing.

General tenets to analytic scoring:

- Reflect emphases in your teaching and communicate the learning goals for the course

- Emphasize student performance across criterion, which are established as central to the assignment in advance, usually on an assignment sheet

- Typically take a quantitative approach, providing a scaled set of points for each criterion

- Make the analytic framework available to students before they write

Advantages of an analytic rubric include ease of training raters and improved reliability. Meanwhile, writers often can more easily diagnose the strengths and weaknesses of their work. But analytic rubrics can be time-consuming to produce, and raters may judge the writing holistically anyway. Moreover, many readers believe that writing traits cannot be separated. (For a summary of the advantages and disadvantages of analytic scoring, see Becker, 2011, p. 115.)

For example, a partial analytic rubric for a single trait, “addresses a significant issue”:

- Excellent: Elegantly establishes the current problem, why it matters, to whom

- Above Average: Identifies the problem; explains why it matters and to whom

- Competent: Describes topic but relevance unclear or cursory

- Developing: Unclear issue and relevance

A complete analytic rubric for a research paper can be downloaded here. In WIM courses, this language should be revised to name specific disciplinary conventions.

Whichever type of rubric you write, your goal is to avoid pushing students into prescriptive formulas and limiting thinking (e.g., “each paragraph has five sentences”). By carefully describing the writing you want to read, you give students a clear target, and, as Ed White puts it, “describe the ongoing work of the class” (75).

Writing rubrics contribute meaningfully to the teaching of writing. Think of them as a coaching aide. In class and in conferences, you can use the language of the rubric to help you move past generic statements about what makes good writing good to statements about what constitutes success on the assignment and in the genre or discourse community. The rubric articulates what you are asking students to produce on the page; once that work is accomplished, you can turn your attention to explaining how students can achieve it.

Works Cited

Becker, Anthony. “Examining Rubrics Used to Measure Writing Performance in U.S. Intensive English Programs.” The CATESOL Journal 22.1 (2010/2011):113-30. Web.

White, Edward M. Teaching and Assessing Writing . Proquest Info and Learning, 1985. Print.

Further Resources

CCCC Committee on Assessment. “Writing Assessment: A Position Statement.” November 2006 (Revised March 2009). Conference on College Composition and Communication. Web.

Gallagher, Chris W. “Assess Locally, Validate Globally: Heuristics for Validating Local Writing Assessments.” Writing Program Administration 34.1 (2010): 10-32. Web.

Huot, Brian. (Re)Articulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning. Logan: Utah State UP, 2002. Print.

Kelly-Reilly, Diane, and Peggy O’Neil, eds. Journal of Writing Assessment. Web.

McKee, Heidi A., and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss DeVoss, Eds. Digital Writing Assessment & Evaluation. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013. Web.

O’Neill, Peggy, Cindy Moore, and Brian Huot. A Guide to College Writing Assessment . Logan: Utah State UP, 2009. Print.

Sommers, Nancy. Responding to Student Writers . Macmillan Higher Education, 2013.

Straub, Richard. “Responding, Really Responding to Other Students’ Writing.” The Subject is Writing: Essays by Teachers and Students. Ed. Wendy Bishop. Boynton/Cook, 1999. Web.

White, Edward M., and Cassie A. Wright. Assigning, Responding, Evaluating: A Writing Teacher’s Guide . 5th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2015. Print.

Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Fall 2022)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper, single-point rubric, more examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

- Enroll & Pay

- Forms + Policies

- Staff Directory

- Research Centers

- Core Research Labs

- Poster Printing + Meeting Space

- Current Leadership Searches

Gratitude for KU peer reviewers

One hundred sixty-eight.

- Creating four discipline-specific standing review panels and a fifth panel focused specifically on racial equity awards

- Providing bias training for reviewers

- Revising evaluation rubrics across all competitions based on best practices for avoiding bias

- Publishing evaluation rubrics to assist with proposal preparation

As we continue to assess and reflect on the peer review process and its outcomes, please share your recommendations with us . In the meantime, please join me in thanking this year’s reviewers. And please consider serving in this critical role if you are invited in the future. Belinda Sturm Interim Vice Chancellor for Research

2023-24 Peer Reviewers

The following KU faculty and staff served as peer reviewers for one or more internal grant and achievement award programs or limited submission competitions sponsored by the Office of Research during the 2023-24 academic year. We are grateful to each of you for devoting your time and expertise to helping us identify promising research, scholarship and creative activity for support and recognition — and for providing constructive feedback to applicants as they continue to pursue their lines of inquiry.

Every effort has been made to ensure this list is complete. If you discover a name is missing, please alert Mindie Paget at [email protected] .

- Perry Alexander , AT&T Foundation Distinguished Professor, electrical engineering & computer science, director, Institute for Information Sciences

- Mike Amlung , associate professor, applied behavioral science and associate scientist, Life Span Institute

- Meredith Bagwell-Gray , assistant professor, social welfare

- Beth Bailey , Foundation Distinguished Professor, history

- Mikhail Barybin , professor, chemistry

- Theodore Bergman , Charles E. & Mary Jane Spahr Professor, mechanical engineering

- James Blakemore , associate professor, chemistry

- Michael Branicky , professor, electrical engineering & computer science

- Juan Bravo-Suarez , associate professor, chemical & petroleum engineering

- Carol Burdsal , director of research development, Office of Research

- Amy Burgin , professor, ecology & evolutionary biology and senior scientist, Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research

- Doug Byers , assistant director, Kansas NSF EPSCoR

- Marco Caricato, professor, chemistry

- Paulyn Cartwright, professor, ecology & evolutionary biology

- Vitaly Chernetsky, professor, Slavic, German & Eurasian studies

- Ana Chicas-Mosier, director of education, outreach & diversity, Center for Environmentally Beneficial Catalysis

- Christopher Cushing, associate professor, applied behavioral science and associate scientist, Life Span Institute

- Mohammed Dastmalchi, assistant professor, architecture

- Jaclyn Dudek, assistant professor, curriculum & teaching and assistant research professor, Achievement & Assessment Institute

- Meghan Ecker-Lyster, director of research, evaluation & dissemination, Achievement & Assessment Institute

- Ken Fischer, professor, mechanical engineering

- Kandace Fleming, senior scientist, Life Span Institute

- Evan Franseen, professor, geology and senior scientist, Kansas Geological Survey

- Craig Freeman, senior scientist, Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research

- Teri Garstka, research associate, Life Span Institute

- Mugur Geana, associate professor, journalism

- Donna Ginther, Roy A. Roberts and Regents Distinguished Professor, economics, and director, Institute for Policy & Social Research

- Ayesha Hardison, associate professor, English and women, gender & sexuality studies

- Meredith Hartley, assistant professor, chemistry

- Lena Hileman, professor and chair, ecology & evolutionary biology

- Michael Hoeflich, John H. & John M. Kane Distinguished Professor, law

- Tzu-Chieh Kurt Hong, assistant professor, architecture

- Chang Hoon Oh, William & Judy Docking Professor, business

- Douglas Wayne Huffman, professor, curriculum & teaching

- Timothy Jackson, professor and chair, chemistry

- Christopher Johnson, professor, music

- In-Gu Kang, assistant teaching professor, educational psychology and assistant research professor, Achievement & Assessment Institute

- John Kelly, professor, ecology & evolutionary biology

- Hyunjoon Kim, assistant professor, pharmaceutical chemistry

- Allison Kirkpatrick, assistant professor, physics & astronomy

- Chris Koliba, Edwin O. Stene Distinguished Professor, public affairs & administration

- Kathleen Lynne Lane, associate vice chancellor for research and Roy A. Roberts Distinguished Professor, special education

- Jilu Li, associate research professor, Center for Remote Sensing & Integrated Systems

- Gaisheng Liu, associate scientist, Kansas Geological Survey

- Erik Lundquist, associate vice chancellor for research and professor, molecular biosciences

- Bo Luo, professor, electrical engineering & computer science

- Stuart Macdonald, professor, molecular biosciences

- Rick Miller, senior scientist, Kansas Geological Survey

- Timothy Musch, University Distinguished Professor, kinesiology, Kansas State University

- Jennifer Ng, professor, educational leadership & policy studies

- Alison Olcott, associate professor, geology

- Hannah Park, associate professor, design

- Dan Reuman, professor, ecology & evolutionary biology and senior scientist, Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research

- Suzanne Shontz, professor, electrical engineering & computer science and associate dean for research & graduate programs, engineering

- Benjamin Sikes, associate professor, ecology & evolutionary biology and associate scientist, Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research

- Joanna Slusky, associate professor, molecular biosciences

- Steven Soper, Foundation Distinguished Professor, chemistry and mechanical engineering

- Belinda Sturm, interim vice chancellor for research and professor, civil, architectural & environmental engineering

- Elaina Sutley, associate professor, civil, architectural & environmental engineering and associate dean for diversity, equity, inclusion & belonging, engineering

- Russell Swerdlow, Gene & Marge Sweeney Professor, neurology, cell biology & anatomy and biochemistry & molecular biology

- Rebecca Swinburne Romine, associate research professor, Life Span Institute

- Candan Tamerler, associate vice chancellor for research and Charles E. & Mary Jane Spahr Professor, mechanical engineering

- Robert Unckless, associate professor, molecular biosciences

- Maggie Wagner, assistant professor, ecology & evolutionary biology and assistant scientist, Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research

- Dale Walker, research professor, Life Span Institute

- Tonya Waller, director of CCAMPIS, Center for Educational Opportunity Programs

- Robert Warrior, Hall Distinguished Professor, English and American studies

- Rebecca Whelan, associate professor, chemistry

- Judy Wu, University Distinguished Professor, physics & astronomy

- Xinmai Yang, professor, mechanical engineering

- Jack Zhang, assistant professor, political science

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Overall Assessment: The assessment of the overall performance of the student based on the evidence provided in items 1 - 10 (or 11) above. ... Microsoft Word - Thesis Research Proposal Evaluation Rubric- PRINT version 10-2011 Author: pcameron Created Date: 10/26/2011 10:08:22 AM ...

Example 9 - Original Research Project Rubric. Language is descriptive, not evaluative. Labels for degrees of success are descriptive ("Expert" "Proficient", etc.); by avoiding the use of letters representing grades or numbers representing points, there is no implied contract that qualities of the paper will "add up" to a specified score or ...

URC PINS proposal evaluation rubric. strong case is made for the novelty and importance of the research. Excellent: The proposed work is highly original and the results are expected to be important in the specific field of research, and perhaps even beyond. Good: The proposed research or scholarly work is novel and that the work is interesting ...

Program Review Research Proposal Rubric Educational Technology, Research and Assessment Use for these course-based artifacts or other experiences: • ETR 519/520 research proposal SLO 1: Design a study of an educational research problem or phenomenon using appropriate methodologies Introduction Acceptable Developing Unacceptable

assessment reports. Instructions: 1. Major Professors and students should review and become familiar with the criteria in the evaluation tool, as a guide, prior to the preparation of a thesis/dissertation proposal. 2. The rubric should be scored by the Major Professor at the time the first complete draft of the proposal is submitted. 3.

Matthew Pearson - Writing Across the Curriculum. The following rubric guides students' writing process by making explicit the conventions for a research proposal. It also leaves room for the instructor to comment on each particular section of the proposal. Clear introduction or abstract (your choice), introducing the purpose, scope, and ...

The goal of this rubric is to identify and assess elements of research presentations, including delivery strategies and slide design. How to use this rubric: • Self-assessment: Record yourself presenting your talk using your computer's pre-downloaded recording software or by using the coach in Microsoft PowerPoint.

Presents a significant research problem related to the chemical sciences. Articulates clear, reasonable research questions given the purpose, design, and methods of the project. All variables and controls have been appropriately defined. Proposals are clearly supported from the research and theoretical literature.

Ability to enhance student's academic development is less clearly demonstrated or less likely. Project does not speak to student's development or only in the weakest manner. X 2. Role, involvement, and activities of student and faculty mentor are carefully presented and explained.

True rubrics feature criteria appropriate to an assessment's purpose, and they describe these criteria across a continuum of performance levels. The presence of both criteria and performance level descriptions distinguishes rubrics from other kinds of evaluation tools (e.g., checklists, rating scales). This paper reviewed studies of rubrics in higher education from 2005 to 2017. The types of ...

Rubric for a Research Proposal. Rubric for a Research Proposal. Posted on October 25, 2017. Matthew Pearson, Writing Across the Curriculum. Posted in Responding, Evaluating, Grading Post navigation. Previous post: USING RUBRICS TO TEACH AND EVALUATE WRITING IN BIOLOGY.

Download Research Paper Rubric PDF. The paper demonstrates that the author fully understands and has applied concepts learned in the course. Concepts are integrated into the writer's own insights. The writer provides concluding remarks that show analysis and synthesis of ideas. The paper demonstrates that the author, for the most part ...

Dissertation Proposal Rubric. Graduate School of Education: Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership. Dissertation Proposal Rubric: 5-part dissertation (with edits by Dannelle D. Stevens, Coordinator and Gayle Thieman, Doctoral Program Committee Member) Score every dimension: Unsatisfactory = 1; Emerging = 2; Proficient = 3; Exemplary = 4.

Proposal Assessment Rubric (v1.2) Office of Research and Planning Proposal Assessment . The purpose of assessing each proposal is to establish a more holistic understanding of the author's intent. This assessment should concentrate on evaluating the stated goals of the proposal as well as to determine the need for additional qualitative ...

Arguments are coherent and clear. Objectives are clear. Demonstrates average critical thinking Reflects understanding of subject Demonstrates understanding of Demonstrates originality. Displays creativity and insight. Good potential for success of research. Arguments are superior. Objectives are well defined.

A complete analytic rubric for a research paper can be downloaded here. In WIM courses, this language should be revised to name specific disciplinary conventions. Conclusion. Whichever type of rubric you write, your goal is to avoid pushing students into prescriptive formulas and limiting thinking (e.g., "each paragraph has five sentences").

The roles of a rubric in writing a research dissertation are two-fold: (1) it serves as a meaningful guide for students' writing of their. dissertation and (2) it provides a proper reference for ...

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Purpose - Assessment rubric often lacks rigor and is underutilized. This article reports the effectiveness of the use of several assessment rubrics for a research writing course. In particular, we examined students' perceived and observed changes in their Chapter One thesis writing as assessed by supervisors using an existing departmental

Purpose - Assessment rubric often lacks rigor and is underutilized. This article reports the effectiveness of the use of several assessment rubrics for a research writing course. Specifically, we examined students' perceived changes and observed changes in their Chapter 1 thesis writing as assessed by supervisors using an existing departmental rubric and a new task-specific rubric ...

This resear ch aims to develop a task and rubric to. assess undergraduate students' r esearch skills. This study. is a research and development using the DDD-E model. design (Decide, Design ...

The table below illustrates a simple grading rubric with each of the four elements for a history research paper. Sample rubric demonstrating the key elements of a rubric. Criteria. Excellent (3 points) Good (2 points) Poor (1 point) Number of sources. Ten to twelve.

Project plan leverages or contributes to existing infrastructure or precedents. Design appears scalable or replicable. Project plan overlooks or fails to mention important connections to relevant work by others, but redeemable. Represents a worthy contribution. Project isolated from related work and duplicates effort.

2014-16 Research Fellowship, Center for Educational Transformation, University of Northern Iowa 2014 Early Career Achievement in Research Award. Iowa State University, College of Human Sciences 2012 Thomas N. Urban Research Award for outstanding research or scholarly contributions to Iowa Education. Awarded by Iowa Academy of Education.

Gratitude for KU peer reviewers. Tue, 04/30/24. SHARE: One hundred sixty-eight. That's how many proposals and nominations the Office of Research received this academic year for our internal grant and achievement award programs and limited submission competitions. Each application represents many hours of thoughtful preparation — and many ...