- Technical Support

- Technical Papers

- Knowledge Base

- Question Library

Call our friendly, no-pressure support team.

Primary vs Secondary Research: Differences, Methods, Sources, and More

Table of Contents

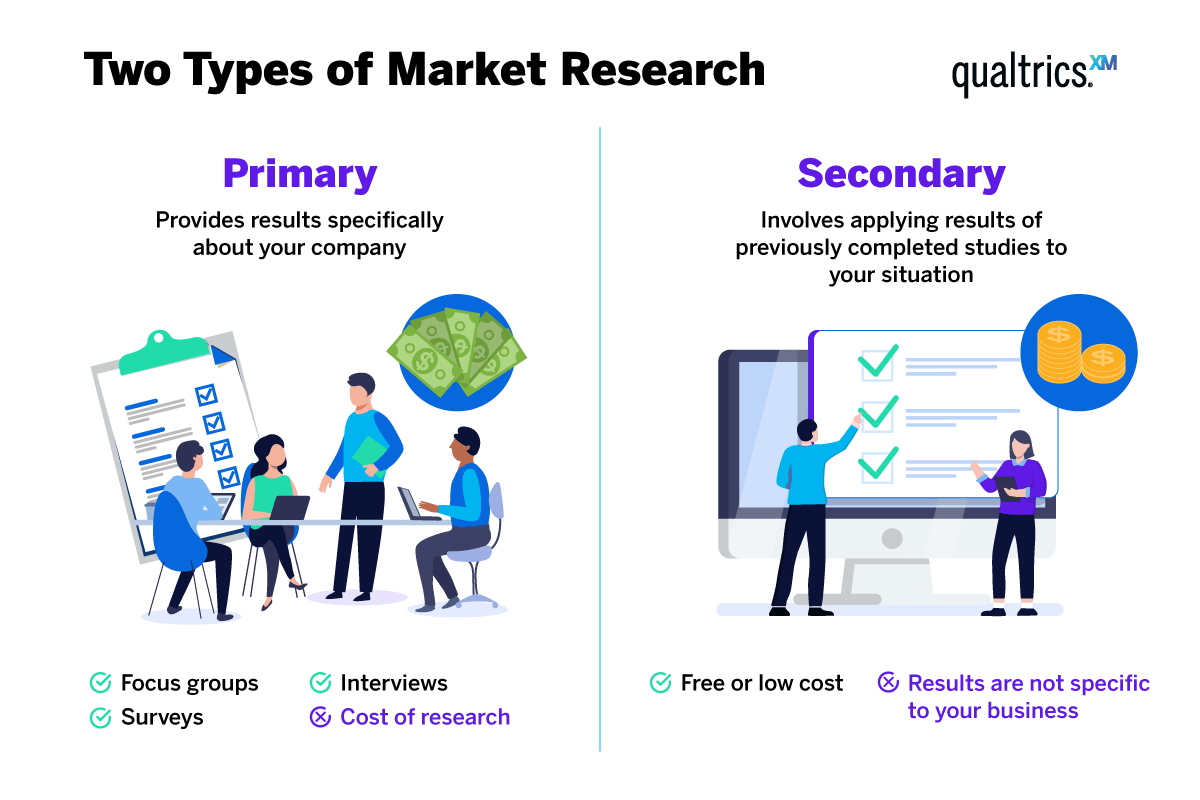

Primary vs Secondary Research – What’s the Difference?

In the search for knowledge and data to inform decisions, researchers and analysts rely on a blend of research sources. These sources are broadly categorized into primary and secondary research, each serving unique purposes and offering different insights into the subject matter at hand. But what exactly sets them apart?

Primary research is the process of gathering fresh data directly from its source. This approach offers real-time insights and specific information tailored to specific objectives set by stakeholders. Examples include surveys, interviews, and observational studies.

Secondary research , on the other hand, involves the analysis of existing data, most often collected and presented by others. This type of research is invaluable for understanding broader trends, providing context, or validating hypotheses. Common sources include scholarly articles, industry reports, and data compilations.

The crux of the difference lies in the origin of the information: primary research yields firsthand data which can be tailored to a specific business question, whilst secondary research synthesizes what's already out there. In essence, primary research listens directly to the voice of the subject, whereas secondary research hears it secondhand .

When to Use Primary and Secondary Research

Selecting the appropriate research method is pivotal and should be aligned with your research objectives. The choice between primary and secondary research is not merely procedural but strategic, influencing the depth and breadth of insights you can uncover.

Primary research shines when you need up-to-date, specific information directly relevant to your study. It's the go-to for fresh insights, understanding consumer behavior, or testing new theories. Its bespoke nature makes it indispensable for tailoring questions to get the exact answers you need.

Ready to Start Gathering Primary Research Data?

Get started with our free survey research tool today! In just a few minutes, you can create powerful surveys with our easy-to-use interface.

Start Survey Research for Free or Request a Product Tour

Secondary research is your first step into the research world. It helps set the stage by offering a broad understanding of the topic. Before diving into costly primary research, secondary research can validate the need for further investigation or provide a solid background to build upon. It's especially useful for identifying trends, benchmarking, and situating your research within the existing body of knowledge.

Combining both methods can significantly enhance your research. Starting with secondary research lays the groundwork and narrows the focus, whilst subsequent primary research delves deep into specific areas of interest, providing a well-rounded, comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Primary vs Secondary Research Methods

In the landscape of market research, the methodologies employed can significantly influence the insights and conclusions drawn. Let's delve deeper into the various methods underpinning both primary and secondary research, shedding light on their unique applications and the distinct insights they offer.

Primary Research Methods:

- Surveys: Surveys are a cornerstone of primary research, offering a quantitative approach to gathering data directly from the target audience. By employing structured questionnaires, researchers can collect a vast array of data ranging from customer preferences to behavioral patterns. This method is particularly valuable for acquiring statistically significant data that can inform decision-making processes and strategy development. The application of statistical approaches for analysing this data, such as key drivers analysis, MaxDiff or conjoint analysis can also further enhance any collected data.

- One on One Interviews: Interviews provide a qualitative depth to primary research, allowing for a nuanced exploration of participants' attitudes, experiences, and motivations. Conducted either face-to-face or remotely, interviews enable researchers to delve into the complexities of human behavior, offering rich insights that surveys alone may not uncover. This method is instrumental in exploring new areas of research or obtaining detailed information on specific topics.

- Focus Groups: Focus groups bring together a small, diverse group of participants to discuss and provide feedback on a particular subject, product, or idea. This interactive setting fosters a dynamic exchange of ideas, revealing consumers' perceptions, experiences, and preferences. Focus groups are invaluable for testing concepts, exploring market trends, and understanding the factors that influence consumer decisions.

- Ethnographic Studies: Ethnographic studies involve the systematic watching, recording, and analysis of behaviors and events in their natural setting. This method offers an unobtrusive way to gather authentic data on how people interact with products, services, or environments, providing insights that can lead to more user-centered design and marketing strategies.

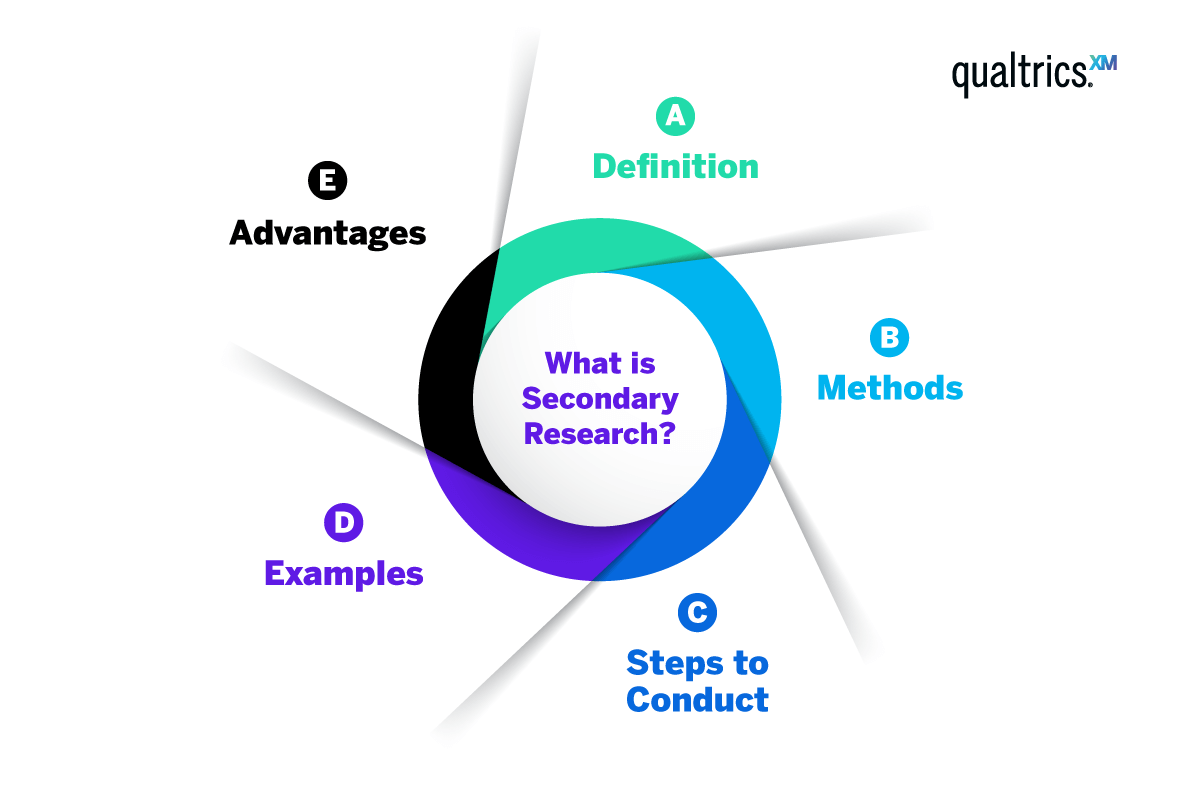

Secondary Research Methods:

- Literature Reviews: Literature reviews involve the comprehensive examination of existing research and publications on a given topic. This method enables researchers to synthesize findings from a range of sources, providing a broad understanding of what is already known about a subject and identifying gaps in current knowledge.

- Meta-Analysis: Meta-analysis is a statistical technique that combines the results of multiple studies to arrive at a comprehensive conclusion. This method is particularly useful in secondary research for aggregating findings across different studies, offering a more robust understanding of the evidence on a particular topic.

- Content Analysis: Content analysis is a method for systematically analyzing texts, media, or other content to quantify patterns, themes, or biases . This approach allows researchers to assess the presence of certain words, concepts, or sentiments within a body of work, providing insights into trends, representations, and societal norms. This can be performed across a range of sources including social media, customer forums or review sites.

- Historical Research: Historical research involves the study of past events, trends, and behaviors through the examination of relevant documents and records. This method can provide context and understanding of current trends and inform future predictions, offering a unique perspective that enriches secondary research.

Each of these methods, whether primary or secondary, plays a crucial role in the mosaic of market research, offering distinct pathways to uncovering the insights necessary to drive informed decisions and strategies.

Primary vs Secondary Sources in Research

Both primary and secondary sources of research form the backbone of the insight generation process, when both are utilized in tandem it can provide the perfect steppingstone for the generation of real insights. Let’s explore how each category serves its unique purpose in the research ecosystem.

Primary Research Data Sources

Primary research data sources are the lifeblood of firsthand research, providing raw, unfiltered insights directly from the source. These include:

- Customer Satisfaction Survey Results: Direct feedback from customers about their satisfaction with a product or service. This data is invaluable for identifying strengths to build on and areas for improvement and typically renews each month or quarter so that metrics can be tracked over time.

- NPS Rating Scores from Customers: Net Promoter Score (NPS) provides a straightforward metric to gauge customer loyalty and satisfaction. This quantitative data can reveal much about customer sentiment and the likelihood of referrals.

- Ad-hoc Surveys: Ad-hoc surveys can be about any topic which requires investigation, they are typically one off surveys which zero in on one particular business objective. Ad-hoc projects are useful for situations such as investigating issues identified in other tracking surveys, new product development, ad testing, brand messaging, and many other kinds of projects.

- A Field Researcher’s Notes: Detailed observations from fieldwork can offer nuanced insights into user behaviors, interactions, and environmental factors that influence those interactions. These notes are a goldmine for understanding the context and complexities of user experiences.

- Recordings Made During Focus Groups: Audio or video recordings of focus group discussions capture the dynamics of conversation, including reactions, emotions, and the interplay of ideas. Analyzing these recordings can uncover nuanced consumer attitudes and perceptions that might not be evident in survey data alone.

These primary data sources are characterized by their immediacy and specificity, offering a direct line to the subject of study. They enable researchers to gather data that is specifically tailored to their research objectives, providing a solid foundation for insightful analysis and strategic decision-making.

Secondary Research Data Sources

In contrast, secondary research data sources offer a broader perspective, compiling and synthesizing information from various origins. These sources include:

- Books, Magazines, Scholarly Journals: Published works provide comprehensive overviews, detailed analyses, and theoretical frameworks that can inform research topics, offering depth and context that enriches primary data.

- Market Research Reports: These reports aggregate data and analyses on industry trends, consumer behavior, and market dynamics, providing a macro-level view that can guide primary research directions and validate findings.

- Government Reports: Official statistics and reports from government agencies offer authoritative data on a wide range of topics, from economic indicators to demographic trends, providing a reliable basis for secondary analysis.

- White Papers, Private Company Data: White papers and reports from businesses and consultancies offer insights into industry-specific research, best practices, and market analyses. These sources can be invaluable for understanding the competitive landscape and identifying emerging trends.

Secondary data sources serve as a compass, guiding researchers through the vast landscape of information to identify relevant trends, benchmark against existing data, and build upon the foundation of existing knowledge. They can significantly expedite the research process by leveraging the collective wisdom and research efforts of others.

By adeptly navigating both primary and secondary sources, researchers can construct a well-rounded research project that combines the depth of firsthand data with the breadth of existing knowledge. This holistic approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the research topic, fostering informed decisions and strategic insights.

Examples of Primary and Secondary Research in Marketing

In the realm of marketing, both primary and secondary research methods play critical roles in understanding market dynamics, consumer behavior, and competitive landscapes. By comparing examples across both methodologies, we can appreciate their unique contributions to strategic decision-making.

Example 1: New Product Development

Primary Research: Direct Consumer Feedback through Surveys and Focus Groups

- Objective: To gauge consumer interest in a new product concept and identify preferred features.

- Process: Surveys distributed to a target demographic to collect quantitative data on consumer preferences, and focus groups conducted to dive deeper into consumer attitudes and desires.

- Insights: Direct insights into consumer needs, preferences for specific features, and willingness to pay. These insights help in refining product design and developing a targeted marketing strategy.

Secondary Research: Market Analysis Reports

- Objective: To understand the existing market landscape, including competitor products and market trends.

- Process: Analyzing published market analysis reports and industry studies to gather data on market size, growth trends, and competitive offerings.

- Insights: Provides a broader understanding of the market, helping to position the new product strategically against competitors and align it with current trends.

Example 2: Brand Positioning

Primary Research: Brand Perception Analysis through Surveys

- Objective: To understand how the brand is perceived by consumers and identify potential areas for repositioning.

- Process: Conducting surveys that ask consumers to describe the brand in their own words, rate it against various attributes, and compare it to competitors.

- Insights: Direct feedback on brand strengths and weaknesses from the consumer's perspective, offering actionable data for adjusting brand messaging and positioning.

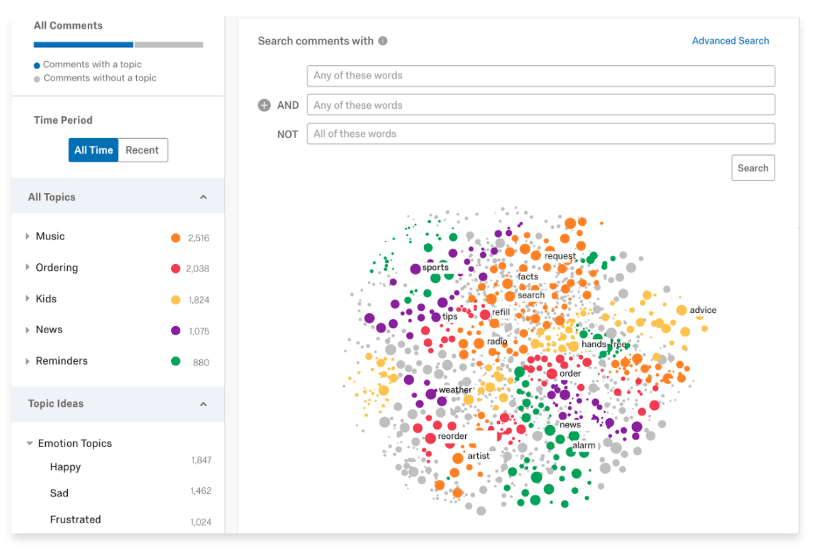

Secondary Research: Social Media Sentiment Analysis

- Objective: To analyze public sentiment towards the brand and its competitors.

- Process: Utilizing software tools to analyze mentions, hashtags, and discussions related to the brand and its competitors across social media platforms.

- Insights: Offers an overview of public perception and emerging trends in consumer sentiment, which can validate findings from primary research or highlight areas needing further investigation.

Example 3: Market Expansion Strategy

Primary Research: Consumer Demand Studies in New Markets

- Objective: To assess demand and consumer preferences in a new geographic market.

- Process: Conducting surveys and interviews with potential consumers in the target market to understand their needs, preferences, and cultural nuances.

- Insights: Provides specific insights into the new market’s consumer behavior, preferences, and potential barriers to entry, guiding market entry strategies.

Secondary Research: Economic and Demographic Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate the economic viability and demographic appeal of the new market.

- Process: Reviewing existing economic reports, demographic data, and industry trends relevant to the target market.

- Insights: Offers a macro view of the market's potential, including economic conditions, demographic trends, and consumer spending patterns, which can complement insights gained from primary research.

By leveraging both primary and secondary research, marketers can form a comprehensive understanding of their market, consumers, and competitors, facilitating informed decision-making and strategic planning. Each method brings its strengths to the table, with primary research offering direct consumer insights and secondary research providing a broader context within which to interpret those insights.

What Are the Pros and Cons of Primary and Secondary Research?

When it comes to market research, both primary and secondary research offer unique advantages and face certain limitations. Understanding these can help researchers and businesses make informed decisions on which approach to utilize for their specific needs. Below is a comparative table highlighting the pros and cons of each research type.

Navigating the Pros and Cons

- Balance Your Research Needs: Consider starting with secondary research to gain a broad understanding of the subject matter, then delve into primary research for specific, targeted insights that are tailored to your precise needs.

- Resource Allocation: Evaluate your budget, time, and resource availability. Primary research can offer more specific and actionable data but requires more resources. Secondary research is more accessible but may lack the specificity or recency you need.

- Quality and Relevance: Assess the quality and relevance of available secondary sources before deciding if primary research is necessary. Sometimes, the existing data might suffice, especially for preliminary market understanding or trend analysis.

- Combining Both for Comprehensive Insights: Often, the most effective research strategy involves a combination of both primary and secondary research. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the market, leveraging the broad perspective provided by secondary sources and the depth and specificity of primary data.

Free Survey Maker Tool

Get access to our free and intuitive survey maker. In just a few minutes, you can create powerful surveys with its easy-to-use interface.

Try our Free Survey Maker or Request a Product Tour

Sawtooth Software

3210 N Canyon Rd Ste 202

Provo UT 84604-6508

United States of America

Support: [email protected]

Consulting: [email protected]

Sales: [email protected]

Products & Services

Support & Resources

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Cyberspace

Research Design and Methodology

Submitted: 23 January 2019 Reviewed: 08 March 2019 Published: 07 August 2019

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.85731

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Edited by Evon Abu-Taieh, Abdelkrim El Mouatasim and Issam H. Al Hadid

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

30,681 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

There are a number of approaches used in this research method design. The purpose of this chapter is to design the methodology of the research approach through mixed types of research techniques. The research approach also supports the researcher on how to come across the research result findings. In this chapter, the general design of the research and the methods used for data collection are explained in detail. It includes three main parts. The first part gives a highlight about the dissertation design. The second part discusses about qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. The last part illustrates the general research framework. The purpose of this section is to indicate how the research was conducted throughout the study periods.

- research design

- methodology

- data sources

Author Information

Kassu jilcha sileyew *.

- School of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Addis Ababa Institute of Technology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

Research methodology is the path through which researchers need to conduct their research. It shows the path through which these researchers formulate their problem and objective and present their result from the data obtained during the study period. This research design and methodology chapter also shows how the research outcome at the end will be obtained in line with meeting the objective of the study. This chapter hence discusses the research methods that were used during the research process. It includes the research methodology of the study from the research strategy to the result dissemination. For emphasis, in this chapter, the author outlines the research strategy, research design, research methodology, the study area, data sources such as primary data sources and secondary data, population consideration and sample size determination such as questionnaires sample size determination and workplace site exposure measurement sample determination, data collection methods like primary data collection methods including workplace site observation data collection and data collection through desk review, data collection through questionnaires, data obtained from experts opinion, workplace site exposure measurement, data collection tools pretest, secondary data collection methods, methods of data analysis used such as quantitative data analysis and qualitative data analysis, data analysis software, the reliability and validity analysis of the quantitative data, reliability of data, reliability analysis, validity, data quality management, inclusion criteria, ethical consideration and dissemination of result and its utilization approaches. In order to satisfy the objectives of the study, a qualitative and quantitative research method is apprehended in general. The study used these mixed strategies because the data were obtained from all aspects of the data source during the study time. Therefore, the purpose of this methodology is to satisfy the research plan and target devised by the researcher.

2. Research design

The research design is intended to provide an appropriate framework for a study. A very significant decision in research design process is the choice to be made regarding research approach since it determines how relevant information for a study will be obtained; however, the research design process involves many interrelated decisions [ 1 ].

This study employed a mixed type of methods. The first part of the study consisted of a series of well-structured questionnaires (for management, employee’s representatives, and technician of industries) and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (government bodies, ministries, and industries) in participating organizations. The other design used is an interview of employees to know how they feel about safety and health of their workplace, and field observation at the selected industrial sites was undertaken.

Hence, this study employs a descriptive research design to agree on the effects of occupational safety and health management system on employee health, safety, and property damage for selected manufacturing industries. Saunders et al. [ 2 ] and Miller [ 3 ] say that descriptive research portrays an accurate profile of persons, events, or situations. This design offers to the researchers a profile of described relevant aspects of the phenomena of interest from an individual, organizational, and industry-oriented perspective. Therefore, this research design enabled the researchers to gather data from a wide range of respondents on the impact of safety and health on manufacturing industries in Ethiopia. And this helped in analyzing the response obtained on how it affects the manufacturing industries’ workplace safety and health. The research overall design and flow process are depicted in Figure 1 .

Research methods and processes (author design).

3. Research methodology

To address the key research objectives, this research used both qualitative and quantitative methods and combination of primary and secondary sources. The qualitative data supports the quantitative data analysis and results. The result obtained is triangulated since the researcher utilized the qualitative and quantitative data types in the data analysis. The study area, data sources, and sampling techniques were discussed under this section.

3.1 The study area

According to Fraenkel and Warren [ 4 ] studies, population refers to the complete set of individuals (subjects or events) having common characteristics in which the researcher is interested. The population of the study was determined based on random sampling system. This data collection was conducted from March 07, 2015 to December 10, 2016, from selected manufacturing industries found in Addis Ababa city and around. The manufacturing companies were selected based on their employee number, established year, and the potential accidents prevailing and the manufacturing industry type even though all criterions were difficult to satisfy.

3.2 Data sources

3.2.1 primary data sources.

It was obtained from the original source of information. The primary data were more reliable and have more confidence level of decision-making with the trusted analysis having direct intact with occurrence of the events. The primary data sources are industries’ working environment (through observation, pictures, and photograph) and industry employees (management and bottom workers) (interview, questionnaires and discussions).

3.2.2 Secondary data

Desk review has been conducted to collect data from various secondary sources. This includes reports and project documents at each manufacturing sectors (more on medium and large level). Secondary data sources have been obtained from literatures regarding OSH, and the remaining data were from the companies’ manuals, reports, and some management documents which were included under the desk review. Reputable journals, books, different articles, periodicals, proceedings, magazines, newsletters, newspapers, websites, and other sources were considered on the manufacturing industrial sectors. The data also obtained from the existing working documents, manuals, procedures, reports, statistical data, policies, regulations, and standards were taken into account for the review.

In general, for this research study, the desk review has been completed to this end, and it had been polished and modified upon manuals and documents obtained from the selected companies.

4. Population and sample size

4.1 population.

The study population consisted of manufacturing industries’ employees in Addis Ababa city and around as there are more representative manufacturing industrial clusters found. To select representative manufacturing industrial sector population, the types of the industries expected were more potential to accidents based on random and purposive sampling considered. The population of data was from textile, leather, metal, chemicals, and food manufacturing industries. A total of 189 sample sizes of industries responded to the questionnaire survey from the priority areas of the government. Random sample sizes and disproportionate methods were used, and 80 from wood, metal, and iron works; 30 from food, beverage, and tobacco products; 50 from leather, textile, and garments; 20 from chemical and chemical products; and 9 from other remaining 9 clusters of manufacturing industries responded.

4.2 Questionnaire sample size determination

A simple random sampling and purposive sampling methods were used to select the representative manufacturing industries and respondents for the study. The simple random sampling ensures that each member of the population has an equal chance for the selection or the chance of getting a response which can be more than equal to the chance depending on the data analysis justification. Sample size determination procedure was used to get optimum and reasonable information. In this study, both probability (simple random sampling) and nonprobability (convenience, quota, purposive, and judgmental) sampling methods were used as the nature of the industries are varied. This is because of the characteristics of data sources which permitted the researchers to follow the multi-methods. This helps the analysis to triangulate the data obtained and increase the reliability of the research outcome and its decision. The companies’ establishment time and its engagement in operation, the number of employees and the proportion it has, the owner types (government and private), type of manufacturing industry/production, types of resource used at work, and the location it is found in the city and around were some of the criteria for the selections.

The determination of the sample size was adopted from Daniel [ 5 ] and Cochran [ 6 ] formula. The formula used was for unknown population size Eq. (1) and is given as

where n = sample size, Z = statistic for a level of confidence, P = expected prevalence or proportion (in proportion of one; if 50%, P = 0.5), and d = precision (in proportion of one; if 6%, d = 0.06). Z statistic ( Z ): for the level of confidence of 95%, which is conventional, Z value is 1.96. In this study, investigators present their results with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The expected sample number was 267 at the marginal error of 6% for 95% confidence interval of manufacturing industries. However, the collected data indicated that only 189 populations were used for the analysis after rejecting some data having more missing values in the responses from the industries. Hence, the actual data collection resulted in 71% response rate. The 267 population were assumed to be satisfactory and representative for the data analysis.

4.3 Workplace site exposure measurement sample determination

The sample size for the experimental exposure measurements of physical work environment has been considered based on the physical data prepared for questionnaires and respondents. The response of positive were considered for exposure measurement factors to be considered for the physical environment health and disease causing such as noise intensity, light intensity, pressure/stress, vibration, temperature/coldness, or hotness and dust particles on 20 workplace sites. The selection method was using random sampling in line with purposive method. The measurement of the exposure factors was done in collaboration with Addis Ababa city Administration and Oromia Bureau of Labour and Social Affair (AACBOLSA). Some measuring instruments were obtained from the Addis Ababa city and Oromia Bureau of Labour and Social Affair.

5. Data collection methods

Data collection methods were focused on the followings basic techniques. These included secondary and primary data collections focusing on both qualitative and quantitative data as defined in the previous section. The data collection mechanisms are devised and prepared with their proper procedures.

5.1 Primary data collection methods

Primary data sources are qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative sources are field observation, interview, and informal discussions, while that of quantitative data sources are survey questionnaires and interview questions. The next sections elaborate how the data were obtained from the primary sources.

5.1.1 Workplace site observation data collection

Observation is an important aspect of science. Observation is tightly connected to data collection, and there are different sources for this: documentation, archival records, interviews, direct observations, and participant observations. Observational research findings are considered strong in validity because the researcher is able to collect a depth of information about a particular behavior. In this dissertation, the researchers used observation method as one tool for collecting information and data before questionnaire design and after the start of research too. The researcher made more than 20 specific observations of manufacturing industries in the study areas. During the observations, it found a deeper understanding of the working environment and the different sections in the production system and OSH practices.

5.1.2 Data collection through interview

Interview is a loosely structured qualitative in-depth interview with people who are considered to be particularly knowledgeable about the topic of interest. The semi-structured interview is usually conducted in a face-to-face setting which permits the researcher to seek new insights, ask questions, and assess phenomena in different perspectives. It let the researcher to know the in-depth of the present working environment influential factors and consequences. It has provided opportunities for refining data collection efforts and examining specialized systems or processes. It was used when the researcher faces written records or published document limitation or wanted to triangulate the data obtained from other primary and secondary data sources.

This dissertation is also conducted with a qualitative approach and conducting interviews. The advantage of using interviews as a method is that it allows respondents to raise issues that the interviewer may not have expected. All interviews with employees, management, and technicians were conducted by the corresponding researcher, on a face-to-face basis at workplace. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

5.1.3 Data collection through questionnaires

The main tool for gaining primary information in practical research is questionnaires, due to the fact that the researcher can decide on the sample and the types of questions to be asked [ 2 ].

In this dissertation, each respondent is requested to reply to an identical list of questions mixed so that biasness was prevented. Initially the questionnaire design was coded and mixed up from specific topic based on uniform structures. Consequently, the questionnaire produced valuable data which was required to achieve the dissertation objectives.

The questionnaires developed were based on a five-item Likert scale. Responses were given to each statement using a five-point Likert-type scale, for which 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.” The responses were summed up to produce a score for the measures.

5.1.4 Data obtained from experts’ opinion

The data was also obtained from the expert’s opinion related to the comparison of the knowledge, management, collaboration, and technology utilization including their sub-factors. The data obtained in this way was used for prioritization and decision-making of OSH, improving factor priority. The prioritization of the factors was using Saaty scales (1–9) and then converting to Fuzzy set values obtained from previous researches using triangular fuzzy set [ 7 ].

5.1.5 Workplace site exposure measurement

The researcher has measured the workplace environment for dust, vibration, heat, pressure, light, and noise to know how much is the level of each variable. The primary data sources planned and an actual coverage has been compared as shown in Table 1 .

Planned versus actual coverage of the survey.

The response rate for the proposed data source was good, and the pilot test also proved the reliability of questionnaires. Interview/discussion resulted in 87% of responses among the respondents; the survey questionnaire response rate obtained was 71%, and the field observation response rate was 90% for the whole data analysis process. Hence, the data organization quality level has not been compromised.

This response rate is considered to be representative of studies of organizations. As the study agrees on the response rate to be 30%, it is considered acceptable [ 8 ]. Saunders et al. [ 2 ] argued that the questionnaire with a scale response of 20% response rate is acceptable. Low response rate should not discourage the researchers, because a great deal of published research work also achieves low response rate. Hence, the response rate of this study is acceptable and very good for the purpose of meeting the study objectives.

5.1.6 Data collection tool pretest

The pretest for questionnaires, interviews, and tools were conducted to validate that the tool content is valid or not in the sense of the respondents’ understanding. Hence, content validity (in which the questions are answered to the target without excluding important points), internal validity (in which the questions raised answer the outcomes of researchers’ target), and external validity (in which the result can generalize to all the population from the survey sample population) were reflected. It has been proved with this pilot test prior to the start of the basic data collections. Following feedback process, a few minor changes were made to the originally designed data collect tools. The pilot test made for the questionnaire test was on 10 sample sizes selected randomly from the target sectors and experts.

5.2 Secondary data collection methods

The secondary data refers to data that was collected by someone other than the user. This data source gives insights of the research area of the current state-of-the-art method. It also makes some sort of research gap that needs to be filled by the researcher. This secondary data sources could be internal and external data sources of information that may cover a wide range of areas.

Literature/desk review and industry documents and reports: To achieve the dissertation’s objectives, the researcher has conducted excessive document review and reports of the companies in both online and offline modes. From a methodological point of view, literature reviews can be comprehended as content analysis, where quantitative and qualitative aspects are mixed to assess structural (descriptive) as well as content criteria.

A literature search was conducted using the database sources like MEDLINE; Emerald; Taylor and Francis publications; EMBASE (medical literature); PsycINFO (psychological literature); Sociological Abstracts (sociological literature); accident prevention journals; US Statistics of Labor, European Safety and Health database; ABI Inform; Business Source Premier (business/management literature); EconLit (economic literature); Social Service Abstracts (social work and social service literature); and other related materials. The search strategy was focused on articles or reports that measure one or more of the dimensions within the research OSH model framework. This search strategy was based on a framework and measurement filter strategy developed by the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) group. Based on screening, unrelated articles to the research model and objectives were excluded. Prior to screening, researcher (principal investigator) reviewed a sample of more than 2000 articles, websites, reports, and guidelines to determine whether they should be included for further review or reject. Discrepancies were thoroughly identified and resolved before the review of the main group of more than 300 articles commenced. After excluding the articles based on the title, keywords, and abstract, the remaining articles were reviewed in detail, and the information was extracted on the instrument that was used to assess the dimension of research interest. A complete list of items was then collated within each research targets or objectives and reviewed to identify any missing elements.

6. Methods of data analysis

Data analysis method follows the procedures listed under the following sections. The data analysis part answered the basic questions raised in the problem statement. The detailed analysis of the developed and developing countries’ experiences on OSH regarding manufacturing industries was analyzed, discussed, compared and contrasted, and synthesized.

6.1 Quantitative data analysis

Quantitative data were obtained from primary and secondary data discussed above in this chapter. This data analysis was based on their data type using Excel, SPSS 20.0, Office Word format, and other tools. This data analysis focuses on numerical/quantitative data analysis.

Before analysis, data coding of responses and analysis were made. In order to analyze the data obtained easily, the data were coded to SPSS 20.0 software as the data obtained from questionnaires. This task involved identifying, classifying, and assigning a numeric or character symbol to data, which was done in only one way pre-coded [ 9 , 10 ]. In this study, all of the responses were pre-coded. They were taken from the list of responses, a number of corresponding to a particular selection was given. This process was applied to every earlier question that needed this treatment. Upon completion, the data were then entered to a statistical analysis software package, SPSS version 20.0 on Windows 10 for the next steps.

Under the data analysis, exploration of data has been made with descriptive statistics and graphical analysis. The analysis included exploring the relationship between variables and comparing groups how they affect each other. This has been done using cross tabulation/chi square, correlation, and factor analysis and using nonparametric statistic.

6.2 Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data analysis used for triangulation of the quantitative data analysis. The interview, observation, and report records were used to support the findings. The analysis has been incorporated with the quantitative discussion results in the data analysis parts.

6.3 Data analysis software

The data were entered using SPSS 20.0 on Windows 10 and analyzed. The analysis supported with SPSS software much contributed to the finding. It had contributed to the data validation and correctness of the SPSS results. The software analyzed and compared the results of different variables used in the research questionnaires. Excel is also used to draw the pictures and calculate some analytical solutions.

7. The reliability and validity analysis of the quantitative data

7.1 reliability of data.

The reliability of measurements specifies the amount to which it is without bias (error free) and hence ensures consistent measurement across time and across the various items in the instrument [ 8 ]. In reliability analysis, it has been checked for the stability and consistency of the data. In the case of reliability analysis, the researcher checked the accuracy and precision of the procedure of measurement. Reliability has numerous definitions and approaches, but in several environments, the concept comes to be consistent [ 8 ]. The measurement fulfills the requirements of reliability when it produces consistent results during data analysis procedure. The reliability is determined through Cranach’s alpha as shown in Table 2 .

Internal consistency and reliability test of questionnaires items.

K stands for knowledge; M, management; T, technology; C, collaboration; P, policy, standards, and regulation; H, hazards and accident conditions; PPE, personal protective equipment.

7.2 Reliability analysis

Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal consistency, i.e., how closely related a set of items are as a group [ 11 ]. It is considered to be a measure of scale reliability. The reliability of internal consistency most of the time is measured based on the Cronbach’s alpha value. Reliability coefficient of 0.70 and above is considered “acceptable” in most research situations [ 12 ]. In this study, reliability analysis for internal consistency of Likert-scale measurement after deleting 13 items was found similar; the reliability coefficients were found for 76 items were 0.964 and for the individual groupings made shown in Table 2 . It was also found internally consistent using the Cronbach’s alpha test. Table 2 shows the internal consistency of the seven major instruments in which their reliability falls in the acceptable range for this research.

7.3 Validity

Face validity used as defined by Babbie [ 13 ] is an indicator that makes it seem a reasonable measure of some variables, and it is the subjective judgment that the instrument measures what it intends to measure in terms of relevance [ 14 ]. Thus, the researcher ensured, in this study, when developing the instruments that uncertainties were eliminated by using appropriate words and concepts in order to enhance clarity and general suitability [ 14 ]. Furthermore, the researcher submitted the instruments to the research supervisor and the joint supervisor who are both occupational health experts, to ensure validity of the measuring instruments and determine whether the instruments could be considered valid on face value.

In this study, the researcher was guided by reviewed literature related to compliance with the occupational health and safety conditions and data collection methods before he could develop the measuring instruments. In addition, the pretest study that was conducted prior to the main study assisted the researcher to avoid uncertainties of the contents in the data collection measuring instruments. A thorough inspection of the measuring instruments by the statistician and the researcher’s supervisor and joint experts, to ensure that all concepts pertaining to the study were included, ensured that the instruments were enriched.

8. Data quality management

Insight has been given to the data collectors on how to approach companies, and many of the questionnaires were distributed through MSc students at Addis Ababa Institute of Technology (AAiT) and manufacturing industries’ experience experts. This made the data quality reliable as it has been continually discussed with them. Pretesting for questionnaire was done on 10 workers to assure the quality of the data and for improvement of data collection tools. Supervision during data collection was done to understand how the data collectors are handling the questionnaire, and each filled questionnaires was checked for its completeness, accuracy, clarity, and consistency on a daily basis either face-to-face or by phone/email. The data expected in poor quality were rejected out of the acting during the screening time. Among planned 267 questionnaires, 189 were responded back. Finally, it was analyzed by the principal investigator.

9. Inclusion criteria

The data were collected from the company representative with the knowledge of OSH. Articles written in English and Amharic were included in this study. Database information obtained in relation to articles and those who have OSH area such as interventions method, method of accident identification, impact of occupational accidents, types of occupational injuries/disease, and impact of occupational accidents, and disease on productivity and costs of company and have used at least one form of feedback mechanism. No specific time period was chosen in order to access all available published papers. The questionnaire statements which are similar in the questionnaire have been rejected from the data analysis.

10. Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the School of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Institute of Technology, Addis Ababa University. Official letters were written from the School of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering to the respective manufacturing industries. The purpose of the study was explained to the study subjects. The study subjects were told that the information they provided was kept confidential and that their identities would not be revealed in association with the information they provided. Informed consent was secured from each participant. For bad working environment assessment findings, feedback will be given to all manufacturing industries involved in the study. There is a plan to give a copy of the result to the respective study manufacturing industries’ and ministries’ offices. The respondents’ privacy and their responses were not individually analyzed and included in the report.

11. Dissemination and utilization of the result

The result of this study will be presented to the Addis Ababa University, AAiT, School of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. It will also be communicated to the Ethiopian manufacturing industries, Ministry of Labor and Social Affair, Ministry of Industry, and Ministry of Health from where the data was collected. The result will also be availed by publication and online presentation in Google Scholars. To this end, about five articles were published and disseminated to the whole world.

12. Conclusion

The research methodology and design indicated overall process of the flow of the research for the given study. The data sources and data collection methods were used. The overall research strategies and framework are indicated in this research process from problem formulation to problem validation including all the parameters. It has laid some foundation and how research methodology is devised and framed for researchers. This means, it helps researchers to consider it as one of the samples and models for the research data collection and process from the beginning of the problem statement to the research finding. Especially, this research flow helps new researchers to the research environment and methodology in particular.

Conflict of interest

There is no “conflict of interest.”

- 1. Aaker A, Kumar VD, George S. Marketing Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000

- 2. Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A. Research Methods for Business Student. 5th ed. Edinburgh Gate: Pearson Education Limited; 2009

- 3. Miller P. Motivation in the Workplace. Work and Organizational Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 1991

- 4. Fraenkel FJ, Warren NE. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002

- 5. Danniel WW. Biostatist: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Science. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999

- 6. Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1977

- 7. Saaty TL. The Analytical Hierarchy Process. Pittsburg: PWS Publications; 1990

- 8. Sekaran U, Bougie R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. 5th ed. New Delhi: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010. pp. 1-468

- 9. Luck DJ, Rubin RS. Marketing Research. 7th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International; 1987

- 10. Wong TC. Marketing Research. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999

- 11. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951; 16 :297-334

- 12. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2011; 2 :53-55. DOI: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- 13. Babbie E. The Practice of Social Research. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2010

- 14. Polit DF, Beck CT. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8th ed. Williams and Wilkins: Lippincott; 2008

© 2019 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Edited by Evon Abu-Taieh

Published: 17 June 2020

By Sabína Gáliková Tolnaiová and Slavomír Gálik

1001 downloads

By Carlos Pedro Gonçalves

1540 downloads

By Konstantinos-George Thanos, Andrianna Polydouri, A...

1040 downloads

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Primary vs Secondary Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Primary vs secondary research – what’s the difference.

14 min read Find out how primary and secondary research are different from each other, and how you can use them both in your own research program.

Primary vs secondary research: in a nutshell

The essential difference between primary and secondary research lies in who collects the data.

- Primary research definition

When you conduct primary research, you’re collecting data by doing your own surveys or observations.

- Secondary research definition:

In secondary research, you’re looking at existing data from other researchers, such as academic journals, government agencies or national statistics.

Free Ebook: The Qualtrics Handbook of Question Design

When to use primary vs secondary research

Primary research and secondary research both offer value in helping you gather information.

Each research method can be used alone to good effect. But when you combine the two research methods, you have the ingredients for a highly effective market research strategy. Most research combines some element of both primary methods and secondary source consultation.

So assuming you’re planning to do both primary and secondary research – which comes first? Counterintuitive as it sounds, it’s more usual to start your research process with secondary research, then move on to primary research.

Secondary research can prepare you for collecting your own data in a primary research project. It can give you a broad overview of your research area, identify influences and trends, and may give you ideas and avenues to explore that you hadn’t previously considered.

Given that secondary research can be done quickly and inexpensively, it makes sense to start your primary research process with some kind of secondary research. Even if you’re expecting to find out what you need to know from a survey of your target market, taking a small amount of time to gather information from secondary sources is worth doing.

Primary research

Primary market research is original research carried out when a company needs timely, specific data about something that affects its success or potential longevity.

Primary research data collection might be carried out in-house by a business analyst or market research team within the company, or it may be outsourced to a specialist provider, such as an agency or consultancy. While outsourcing primary research involves a greater upfront expense, it’s less time consuming and can bring added benefits such as researcher expertise and a ‘fresh eyes’ perspective that avoids the risk of bias and partiality affecting the research data.

Primary research gives you recent data from known primary sources about the particular topic you care about, but it does take a little time to collect that data from scratch, rather than finding secondary data via an internet search or library visit.

Primary research involves two forms of data collection:

- Exploratory research This type of primary research is carried out to determine the nature of a problem that hasn’t yet been clearly defined. For example, a supermarket wants to improve its poor customer service and needs to understand the key drivers behind the customer experience issues. It might do this by interviewing employees and customers, or by running a survey program or focus groups.

- Conclusive research This form of primary research is carried out to solve a problem that the exploratory research – or other forms of primary data – has identified. For example, say the supermarket’s exploratory research found that employees weren’t happy. Conclusive research went deeper, revealing that the manager was rude, unreasonable, and difficult, making the employees unhappy and resulting in a poor employee experience which in turn led to less than excellent customer service. Thanks to the company’s choice to conduct primary research, a new manager was brought in, employees were happier and customer service improved.

Examples of primary research

All of the following are forms of primary research data.

- Customer satisfaction survey results

- Employee experience pulse survey results

- NPS rating scores from your customers

- A field researcher’s notes

- Data from weather stations in a local area

- Recordings made during focus groups

Primary research methods

There are a number of primary research methods to choose from, and they are already familiar to most people. The ones you choose will depend on your budget, your time constraints, your research goals and whether you’re looking for quantitative or qualitative data.

A survey can be carried out online, offline, face to face or via other media such as phone or SMS. It’s relatively cheap to do, since participants can self-administer the questionnaire in most cases. You can automate much of the process if you invest in good quality survey software.

Primary research interviews can be carried out face to face, over the phone or via video calling. They’re more time-consuming than surveys, and they require the time and expense of a skilled interviewer and a dedicated room, phone line or video calling setup. However, a personal interview can provide a very rich primary source of data based not only on the participant’s answers but also on the observations of the interviewer.

Focus groups

A focus group is an interview with multiple participants at the same time. It often takes the form of a discussion moderated by the researcher. As well as taking less time and resources than a series of one-to-one interviews, a focus group can benefit from the interactions between participants which bring out more ideas and opinions. However this can also lead to conversations going off on a tangent, which the moderator must be able to skilfully avoid by guiding the group back to the relevant topic.

Secondary research

Secondary research is research that has already been done by someone else prior to your own research study.

Secondary research is generally the best place to start any research project as it will reveal whether someone has already researched the same topic you’re interested in, or a similar topic that helps lay some of the groundwork for your research project.

Even if your preliminary secondary research doesn’t turn up a study similar to your own research goals, it will still give you a stronger knowledge base that you can use to strengthen and refine your research hypothesis. You may even find some gaps in the market you didn’t know about before.

The scope of secondary research resources is extremely broad. Here are just a few of the places you might look for relevant information.

Books and magazines

A public library can turn up a wealth of data in the form of books and magazines – and it doesn’t cost a penny to consult them.

Market research reports

Secondary research from professional research agencies can be highly valuable, as you can be confident the data collection methods and data analysis will be sound

Scholarly journals, often available in reference libraries

Peer-reviewed journals have been examined by experts from the relevant educational institutions, meaning there has been an extra layer of oversight and careful consideration of the data points before publication.

Government reports and studies

Public domain data, such as census data, can provide relevant information for your research project, not least in choosing the appropriate research population for a primary research method. If the information you need isn’t readily available, try contacting the relevant government agencies.

White papers

Businesses often produce white papers as a means of showcasing their expertise and value in their field. White papers can be helpful in secondary research methods, although they may not be as carefully vetted as academic papers or public records.

Trade or industry associations

Associations may have secondary data that goes back a long way and offers a general overview of a particular industry. This data collected over time can be very helpful in laying the foundations of your particular research project.

Private company data

Some businesses may offer their company data to those conducting research in return for fees or with explicit permissions. However, if a business has data that’s closely relevant to yours, it’s likely they are a competitor and may flat out refuse your request.

Learn more about secondary research

Examples of secondary research data

These are all forms of secondary research data in action:

- A newspaper report quoting statistics sourced by a journalist

- Facts from primary research articles quoted during a debate club meeting

- A blog post discussing new national figures on the economy

- A company consulting previous research published by a competitor

Secondary research methods

Literature reviews.

A core part of the secondary research process, involving data collection and constructing an argument around multiple sources. A literature review involves gathering information from a wide range of secondary sources on one topic and summarizing them in a report or in the introduction to primary research data.

Content analysis

This systematic approach is widely used in social science disciplines. It uses codes for themes, tropes or key phrases which are tallied up according to how often they occur in the secondary data. The results help researchers to draw conclusions from qualitative data.

Data analysis using digital tools

You can analyze large volumes of data using software that can recognize and categorize natural language. More advanced tools will even be able to identify relationships and semantic connections within the secondary research materials.

Comparing primary vs secondary research

We’ve established that both primary research and secondary research have benefits for your business, and that there are major differences in terms of the research process, the cost, the research skills involved and the types of data gathered. But is one of them better than the other?

The answer largely depends on your situation. Whether primary or secondary research wins out in your specific case depends on the particular topic you’re interested in and the resources you have available. The positive aspects of one method might be enough to sway you, or the drawbacks – such as a lack of credible evidence already published, as might be the case in very fast-moving industries – might make one method totally unsuitable.

Here’s an at-a-glance look at the features and characteristics of primary vs secondary research, illustrating some of the key differences between them.

What are the pros and cons of primary research?

Primary research provides original data and allows you to pinpoint the issues you’re interested in and collect data from your target market – with all the effort that entails.

Benefits of primary research:

- Tells you what you need to know, nothing irrelevant

- Yours exclusively – once acquired, you may be able to sell primary data or use it for marketing

- Teaches you more about your business

- Can help foster new working relationships and connections between silos

- Primary research methods can provide upskilling opportunities – employees gain new research skills

Limitations of primary research:

- Lacks context from other research on related subjects

- Can be expensive

- Results aren’t ready to use until the project is complete

- Any mistakes you make in in research design or implementation could compromise your data quality

- May not have lasting relevance – although it could fulfill a benchmarking function if things change

What are the pros and cons of secondary research?

Secondary research relies on secondary sources, which can be both an advantage and a drawback. After all, other people are doing the work, but they’re also setting the research parameters.

Benefits of secondary research:

- It’s often low cost or even free to access in the public domain

- Supplies a knowledge base for researchers to learn from

- Data is complete, has been analyzed and checked, saving you time and costs

- It’s ready to use as soon as you acquire it

Limitations of secondary research

- May not provide enough specific information

- Conducting a literature review in a well-researched subject area can become overwhelming

- No added value from publishing or re-selling your research data

- Results are inconclusive – you’ll only ever be interpreting data from another organization’s experience, not your own

- Details of the research methodology are unknown

- May be out of date – always check carefully the original research was conducted

Related resources

Business research methods 12 min read, qualitative research interviews 11 min read, market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Unit 3: Getting to, and thinking critically about, the [Secondary] Research

11 *primary vs secondary research.

Students tend to get a wee bit discombobulated in this chapter and I’ll tell you why — it’s those STINKIN’ PRIMARY SOURCES !

In 1305 we’re talking about social scientific r esearch methods and primary RESEARCH . Although our humanistic friends give us some great advice about how to evaluate a primary source , a primary source is pretty darned different from primary research.

Learning Objectives

What is the difference between primary and secondary research? When and how to utilize each type of research? And how is primary research different from a primary source??

- Primary vs Secondary Research

Research can be categorized into two types: Primary vs Secondary

Primary Research is original research (e.g., qualitative, quantitative ) that a researcher performs to explore or answer a question. This is the type of research a scientist performs to answer their own questions with data that they collect themselves .

Ex. conducting scholarly interviews, surveys, analysis, observations, etc. Used to create new science (then published via journal or book).

Secondary Research is research has been conducted independently of you is used to further your own research or knowledge. Often published in journals and accessible through databases. By conducting secondary research, you can develop a combination or summary of existing research. These resources can be used to help form your research question or hypothesis, then conduct your own primary research. Mainly used for preparing primary research.

Ex. Traditional textbooks, market research, literature reviews

These two types of research can be distinguished by thinking of primary as the original person conducting their own new research and secondary as a summary or collection of existing original, primary research.

So, what’s the big deal about Secondary Research?

Five main purposes of secondary research:.

- While reading secondary research regarding a topic, researchers can see what research has already been done and how they might attempt to further study the topic or what questions they might attempt to answer.

- Through reading compiled summaries of past research, researchers can see what problems or limitations other studies have encountered, and formulate ways to counteract that.

- By comparing to past research, researchers can create a plan for which methodology and sampling method they will use.

- Secondary research can provide a clearer picture of the population the researcher intends to reach, and which avenues are best to represent the population most effectively.

- Comparing your data to other study’s data can be helpful to see what new things may have been found in your study.

No Primary research should be done without conducting Secondary research first!

TEXTBOOK CONTRIBUTION

Example contributed by: Monica Buchholz, Erica Cole, Charlie Boyle, Marvin Gutierrez, Edwin Leon

Here are some key points to remember about primary v secondary research compiled by Caroline McCullough and Abby Lundvall! (Fall 2022)

- What is a journal?

- Research through databases

- Publishing and Predators

Introduction to Social Scientific Research Methods in the field of Communication 3rd Ed - under construction for Fall 2023 Copyright © 2023 by Kate Magsamen-Conrad. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Objectives

Research objectives refer to the specific goals or aims of a research study. They provide a clear and concise description of what the researcher hopes to achieve by conducting the research . The objectives are typically based on the research questions and hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the study and are used to guide the research process.

Types of Research Objectives

Here are the different types of research objectives in research:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are used to explore a topic, issue, or phenomenon that has not been studied in-depth before. The aim of exploratory research is to gain a better understanding of the subject matter and generate new ideas and hypotheses .

- Descriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to describe the characteristics, features, or attributes of a particular population, group, or phenomenon. Descriptive research answers the “what” questions and provides a snapshot of the subject matter.

- Explanatory Objectives : These objectives aim to explain the relationships between variables or factors. Explanatory research seeks to identify the cause-and-effect relationships between different phenomena.

- Predictive Objectives: These objectives aim to predict future events or outcomes based on existing data or trends. Predictive research uses statistical models to forecast future trends or outcomes.

- Evaluative Objectives : These objectives aim to evaluate the effectiveness or impact of a program, intervention, or policy. Evaluative research seeks to assess the outcomes or results of a particular intervention or program.

- Prescriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to provide recommendations or solutions to a particular problem or issue. Prescriptive research identifies the best course of action based on the results of the study.

- Diagnostic Objectives : These objectives aim to identify the causes or factors contributing to a particular problem or issue. Diagnostic research seeks to uncover the underlying reasons for a particular phenomenon.

- Comparative Objectives: These objectives aim to compare two or more groups, populations, or phenomena to identify similarities and differences. Comparative research is used to determine which group or approach is more effective or has better outcomes.

- Historical Objectives: These objectives aim to examine past events, trends, or phenomena to gain a better understanding of their significance and impact. Historical research uses archival data, documents, and records to study past events.

- Ethnographic Objectives : These objectives aim to understand the culture, beliefs, and practices of a particular group or community. Ethnographic research involves immersive fieldwork and observation to gain an insider’s perspective of the group being studied.

- Action-oriented Objectives: These objectives aim to bring about social or organizational change. Action-oriented research seeks to identify practical solutions to social problems and to promote positive change in society.

- Conceptual Objectives: These objectives aim to develop new theories, models, or frameworks to explain a particular phenomenon or set of phenomena. Conceptual research seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the subject matter by developing new theoretical perspectives.

- Methodological Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and improve research methods and techniques. Methodological research seeks to advance the field of research by improving the validity, reliability, and accuracy of research methods and tools.

- Theoretical Objectives : These objectives aim to test and refine existing theories or to develop new theoretical perspectives. Theoretical research seeks to advance the field of knowledge by testing and refining existing theories or by developing new theoretical frameworks.

- Measurement Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and validate measurement instruments, such as surveys, questionnaires, and tests. Measurement research seeks to improve the quality and reliability of data collection and analysis by developing and testing new measurement tools.

- Design Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and refine research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational designs. Design research seeks to improve the quality and validity of research by developing and testing new research designs.

- Sampling Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and refine sampling techniques, such as probability and non-probability sampling methods. Sampling research seeks to improve the representativeness and generalizability of research findings by developing and testing new sampling techniques.

How to Write Research Objectives

Writing clear and concise research objectives is an important part of any research project, as it helps to guide the study and ensure that it is focused and relevant. Here are some steps to follow when writing research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Before you can write research objectives, you need to identify the research problem you are trying to address. This should be a clear and specific problem that can be addressed through research.

- Define the research questions : Based on the research problem, define the research questions you want to answer. These questions should be specific and should guide the research process.

- Identify the variables : Identify the key variables that you will be studying in your research. These are the factors that you will be measuring, manipulating, or analyzing to answer your research questions.

- Write specific objectives: Write specific, measurable objectives that will help you answer your research questions. These objectives should be clear and concise and should indicate what you hope to achieve through your research.

- Use the SMART criteria: To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and achievable, use the SMART criteria. This means that your objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound.

- Revise and refine: Once you have written your research objectives, revise and refine them to ensure that they are clear, concise, and achievable. Make sure that they align with your research questions and variables, and that they will help you answer your research problem.

Example of Research Objectives

Examples of research objectives Could be:

Research Objectives for the topic of “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment”:

- To investigate the effects of the adoption of AI on employment trends across various industries and occupations.

- To explore the potential for AI to create new job opportunities and transform existing roles in the workforce.

- To examine the social and economic implications of the widespread use of AI for employment, including issues such as income inequality and access to education and training.

- To identify the skills and competencies that will be required for individuals to thrive in an AI-driven workplace, and to explore the role of education and training in developing these skills.

- To evaluate the ethical and legal considerations surrounding the use of AI for employment, including issues such as bias, privacy, and the responsibility of employers and policymakers to protect workers’ rights.

When to Write Research Objectives

- At the beginning of a research project : Research objectives should be identified and written down before starting a research project. This helps to ensure that the project is focused and that data collection and analysis efforts are aligned with the intended purpose of the research.