| Word Tools | | Finders & Helpers | | Apps | | More | | Synonyms | | | | | | |

| | Copyright WordHippo © 2024 | Have a language expert improve your writingRun a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free. Methodology - What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & MethodsPublished on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023. A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research. A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem . Table of contentsWhen to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles. A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case. Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research. You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem. Case study examples | Research question | Case study | | What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park | | How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump | | How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning | | What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country | | How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign | | How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London | Receive feedback on language, structure, and formattingProfessional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on: - Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example  Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to: - Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead. Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem. Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease. However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon. Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time. While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to: - Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation. There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data. Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development. The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context. Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading servicesDiscover proofreading & editing In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject. How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion . Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ). In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates. If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples. - Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias - Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr articleIf you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator. McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/ Is this article helpful? Shona McCombesOther students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..". I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes” Look up a word, learn it forever./ˌkeɪ(s) ˈstʌdi/, /keɪs ˈstʌdi/. Other forms: case studies - noun a detailed analysis of a person or group from a social or psychological or medical point of view see more see less type of: analysis an investigation of the component parts of a whole and their relations in making up the whole

- noun a careful study of some social unit (as a corporation or division within a corporation) that attempts to determine what factors led to its success or failure see more see less type of: report , study , written report a written document describing the findings of some individual or group

Vocabulary lists containing case study Get your neurons firing with this list of words related to psychology. You'll learn about parts of the brain, cognition and memory, psychiatry, phobias and psychological disorders, and more. This list will blow your mind! Sign up now (it’s free!)Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.. - Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book." :max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg) Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter. :max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg) Verywell / Colleen Tighe What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study. A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work. The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population. While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference. At a GlanceA case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective. What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs. One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study: - Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks: - It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies. It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research. Case Study ExamplesThere have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include: - Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development. This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce. There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use: - Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously. The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself. There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are: - Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study. Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study. Section 1: A Case HistoryThis section will have the following structure and content: Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses. Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with. Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported. Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis. Section 2: Treatment PlanThis portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen. - Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes. When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research. In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies? Need More Tips?Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study: - Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100 Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010. Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017. By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book." - ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary What is another word for case study ?Synonyms for case study case study, this thesaurus page includes all potential synonyms, words with the same meaning and similar terms for the word case study ., princeton's wordnet. a careful study of some social unit (as a corporation or division within a corporation) that attempts to determine what factors led to its success or failure a detailed analysis of a person or group from a social or psychological or medical point of view Matched CategoriesConcise Medical Dictionary, by Joseph C Segen, MD Rate these synonyms: 2.2 / 5 votesSynonyms: Epidemiology Anecdotal report, anecdote, single case report How to pronounce case study?How to say case study in sign language, how to use case study in a sentence. Alba Pasini : This case study is really important, since it testifies that a medical approach to maternal morbidity actually existed during the Lombard period, despite the rejection of the scientific progress which denoted all the Early Middle Age, also, it shows two rare findings, since post-mortem fetal extrusion is a quite rare phenomenon( especially in archaeological specimens), while only a few examples of trepanation are known for the European Early Middle Age. Josh Holmes : For those asking, this is my response to West Virginia Roy Moore :' This clown is a walking, talking case study for the limitation of a prison's ability to rehabilitate,'. Tesoro Corp : We agree on the critical importance of continually learning from incidents and improving the safety of our operations, and inaccuracies in the case study do not detract from our resolve to learn from these incidents. Houston Astros : I think I’m kind of a case study on this one. Sam Goodman : The Hong Kong BNO scheme is an interesting case study of what can happen if there is political will, there are 12 welcome centers across the country and a really good support package which costs relatively little, including help with English language. And most importantly they just didn’t politicize it. All this has meant that 144,000 Hong Kongers have come here with little to no fuss, integrated quickly and there have been minimal issues. Use the citation below to add these synonyms to your bibliography:Style: MLA Chicago APA "case study." Synonyms.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 11 Jun 2024. < https://www.synonyms.com/synonym/case+study >.  Discuss these case study synonyms with the community: Report CommentWe're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly. You need to be logged in to favorite .Create a new account. Your name: * Required Your email address: * Required Pick a user name: * Required Username: * Required Password: * Required Forgot your password? Retrieve it Are we missing a good synonym for case study ?Image credit, the web's largest resource for, synonyms & antonyms, a member of the stands4 network, image or illustration of.  Free, no signup required :Add to chrome, add to firefox, browse synonyms.com, are you a human thesaurus, which of the following terms is an antonym of "grievous", nearby & related entries:. - case load noun

- case officer noun

- case reporter

- case sensitive

- case shot noun

- case-by-case adj

- case-fatality

- case-fatality proportion noun

Alternative searches for case study :- Search for case study on Amazon

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of case studyExamples of case study in a sentence. These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'case study.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples. Word History1914, in the meaning defined at sense 1 Dictionary Entries Near case studycase spring case study method Cite this Entry“Case study.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/case%20study. Accessed 11 Jun. 2024. More from Merriam-Webster on case studyThesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for case study Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about case study Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!  Can you solve 4 words at once?Word of the day. See Definitions and Examples » Get Word of the Day daily email! Popular in Grammar & UsageWhat's the difference between 'fascism' and 'socialism', more commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - june 7, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.  Have a language expert improve your writingRun a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free. - Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & MethodsPublished on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023. A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research. A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem . Table of contentsWhen to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case. A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case. Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research. You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem. Case study examples | Research question | Case study | | What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in the US | | How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump | | How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning | | What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country | | How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign | | How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race, and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London | Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to: - Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem. If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible. However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon. While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to: - Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation. There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data . The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context. In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject. How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion . Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ). In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates. Cite this Scribbr articleIf you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator. McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 11 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/ Is this article helpful? Shona McCombesOther students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples. - Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of case study noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary - She co-authored a case study on urban development.

Questions about grammar and vocabulary? Find the answers with Practical English Usage online, your indispensable guide to problems in English. - Athletes make an interesting case study for doctors.

Nearby words- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement - a study of an individual unit, as a person, family, or social group, usually emphasizing developmental issues and relationships with the environment, especially in order to compare a larger group to the individual unit.

- case history .

- the act or an instance of analysing one or more particular cases or case histories with a view to making generalizations

Discover MoreWord history and origins. Origin of case study 1 Example SentencesIn a case study from Metric Theory, Target Impression Share bidding, the total cost per click increased with both mobile and desktop devices. It would also become the subject of a fair number of business school case studies. Not just blog posts, you can also share other resources like case studies, podcast episodes, and webinars via Instagram Stories. They become the architecture for a case study of Flint, expressed in a more personal and poetic way than a straightforward investigation could. The Creek Fire was a case study in the challenge facing today’s fire analysts, who are trying to predict the movements of fires that are far more severe than those seen just a decade ago. A case study would be your Twilight director Catherine Hardwicke. A good case study for the minority superhero problem is Luke Cage. He was asked to review a case study out of Lebanon that had cited his work. Instead, now we have a political science case-study proving how political fortunes can shift and change at warp speed. One interesting case study is Sir Arthur Evans, the original excavator and “restorer” of the Minoan palace of Knossos on Crete. As this is a case study, it should be said that my first mistake was in discrediting my early religious experience. The author of a recent case study of democracy in a frontier county commented on the need for this kind of investigation. How could a case study of Virginia during this period illustrate these developments? Related Words - Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of case study in EnglishYour browser doesn't support HTML5 audio - anti-narrative

- be another story idiom

- bodice-ripper

- cautionary tale

- in medias res

- misdescription

- running commentary phrase

- semi-legendary

- shaggy-dog story

- write something up

case study | American DictionaryCase study | business english, examples of case study, translations of case study. Get a quick, free translation!  Word of the Day to shape something so that it can move as effectively and quickly as possible through a liquid or gas  Worse than or worst of all? How to use the words ‘worse’ and ‘worst’  Learn more with +Plus- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- American Noun

- Business Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add case study to a word list please sign up or log in. Add case study to one of your lists below, or create a new one. {{message}} Something went wrong. There was a problem sending your report. - Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement noun as in learning, analysis Strongest matches application , class , consideration , course , debate , examination , exercise , inquiry , inspection , investigation , research , review , subject , survey Strong matches abstraction , analyzing , attention , cogitation , comparison , concentration , contemplation , cramming , deliberation , lesson , meditation , memorizing , muse , musing , pondering , questioning , reading , reasoning , reflection , reverie , rumination , schoolwork , scrutiny , thought , trance , weighing academic work verb as in contemplate, learn consider , examine , learn , ponder , pore over , read , think coach , cogitate , cram , dig , excogitate , grind , inquire , lucubrate , meditate , mind , peruse , plug , plunge , refresh , tutor , weigh Weak matches apply oneself , bone up , brood over , burn midnight oil , bury oneself in , crack the books , dive into , go into , go over , hit the books , learn the ropes , mull over , perpend , polish up , read up , think out , think over verb as in examine, analyze inspect , investigate , read , research , scrutinize , survey , view brainstorm , canvass , case , compare , deliberate , figure , peruse , scope check out , check over , check up , do research , give the eagle eye , keep tabs , look into , sort out Discover MoreExample sentences. Those studies are scheduled for completion over about the next year and a half. The study tallied activity in more than a dozen different cryptocurrencies. More recently, studies have reported on what the infection might do to the heart. That’s according to a new study published in Science Advances. The study, published Friday in the journal Environmental Research Letters, found this association in both rural counties in Louisiana and highly populated communities in New York. She completed a yoga teacher-training program and, in the spring of 2008, went on a retreat in Peru to study with shamans. In fact, in a recent study of their users internationally, it was the lowest priority for most. But in the case of black women, another study found no lack of interest. Indeed, study after study affirms the benefits of involved fatherhood for women and children. A recent U.S. study found men get a “daddy bonus” —employers seem to like men who have children and their salaries show it. "There's just one thing I'd like to ask, if you don't mind," said Cynthia, coming suddenly out of a brown study. His lordship retired shortly to his study, Hetton and Mr. Haggard betook themselves to the billiard-room. She began the study of drawing at the age of thirty, and her first attempt in oils was made seven years later. In practice we find a good deal of technical study comes into the college stage. Its backbone should be the study of biology and its substance should be the threshing out of the burning questions of our day. Related WordsWords related to study are not direct synonyms, but are associated with the word study . Browse related words to learn more about word associations. noun as in careful considering - calculation

- consideration

- deliberation

noun as in nook, secluded spot noun as in statement of results from examination noun as in examination and determination - dissolution

- investigation

- subdivision

Viewing 5 / 196 related words On this page you'll find 307 synonyms, antonyms, and words related to study, such as: application, class, consideration, course, debate, and examination. From Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group. Create powerful business content together.  BONUS : Read the case study how-to guide . Case Study Template Good case studies tell a compelling story to potential clients of how your company rose to the occasion. The Case Study Template will help you showcase your company’s credibility in solving a particularly challenging client problem and prove to potential clients that you have what it takes to perform well. Specifically, case studies can help you: - Highlight your expertise in delivering measurable results based on KPIs.

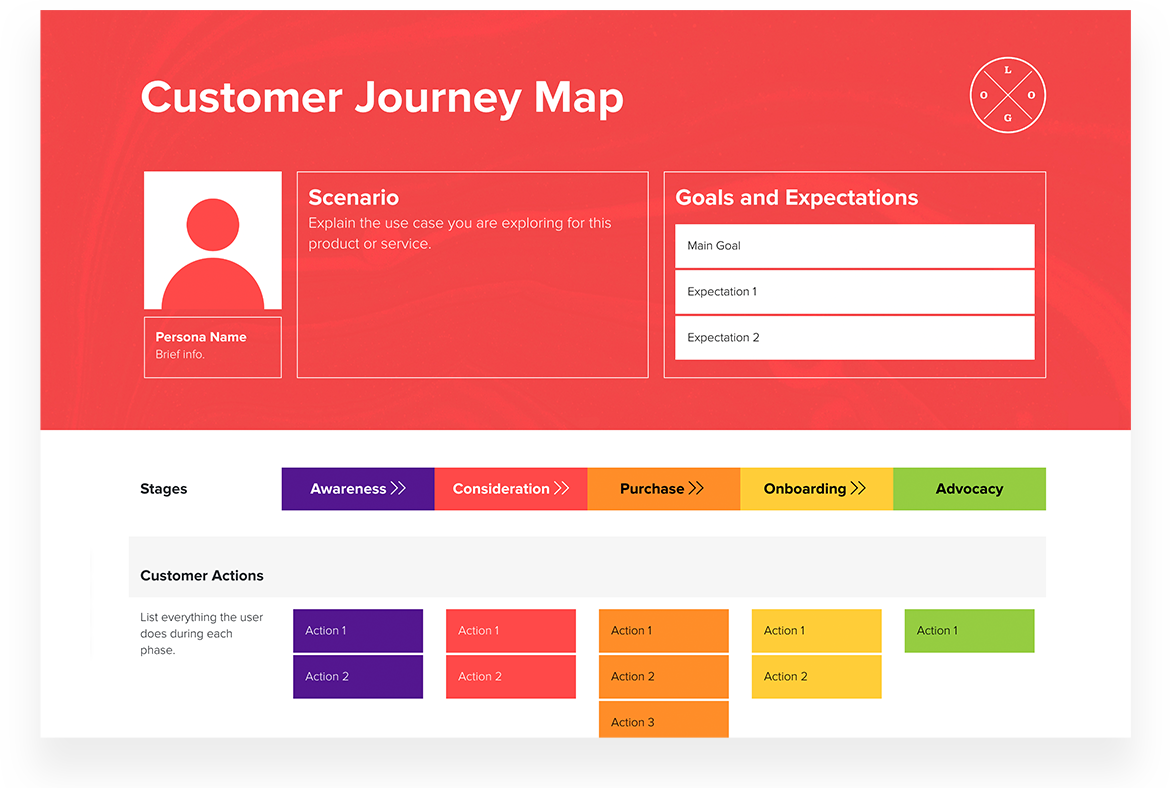

- Position your brand as an authority in your industry to attract potential customers.

- Provide visual proof of your skills, experience, and expertise as a company.

- Showcase your perseverance in handling difficult projects or campaigns.

Xtensio is your team space for beautiful living documents. Create , manage and share business collateral, easily. Join the 259,673 changemakers. Other Case Study Templates How to create an effective Case Study with Xtensio- Click and start editing, no account or credit card required. Follow along with the instructional copy. Add charts, graphs, images, and videos to customize your case study. Drag & drop. Resize. It’s the easiest editor ever.

- Customize everything to match your brand. Define your style guide; Add your (or your client’s) brand fonts and colors. You can even pull colors directly from a website to easily brand your case studies.

- Work on the key details of your case study together on the cloud. Add colleagues (or clients) to collaborate on the case study template. Changes automatically save and sync across all devices, in real-time.

- Share a link. Present a slideshow. Embed. Download a PDF/PNG. Your case study seamlessly adapts to your workflow. No more jumping from tool-to-tool to create different types of deliverables.

- Reuse and repurpose. Save your own custom case study templates. Or copy and merge into other documents.

Follow along step-by-step with the Case Study how-to guide . What is a case study?An effective case study is a great way to show potential clients, customers, and stakeholders how valuable your product or service is by explaining how your business solved a particularly challenging client problem. Marketing case studies examine a single client situation in-depth and provide a detailed analysis of how your organization resolved the challenge. The best case studies not only tell a story about your company but also contain some hard measurable metrics. This allows you to highlight your successes in a way that will make an ideal potential customer become your customer. Essentially, a case study is an effective way to learn about your business and a great marketing tool. When looking for potential projects to use for a case study, look for ones that: - Involved a particular challenge that required a unique set of skills that your company possesses

- Received special awards, press coverage or accolades

- Involved a high profile project

- Involved a well-known (preferably Fortune 500) brand or company

The most important element of your case study is that it must show a real-life example to relate to your target client. While a good case study showcases your company, a great case study makes the reader want to start a conversation with you. What information should be included in a case study?The first thing to consider is who will be reading your case studies. Messages and their delivery resonate differently, depending on who is on the receiving end. For example, a thirty-something software entrepreneur will measure success differently than a fifty-something CEO of a large corporation. Understanding your target audience will help you tell your case study in a way that will effectively speak to them. When gathering information for your case study, interview happy customers and ask questions to your potential case study subject that align with the story you are trying to tell. No case study will be the same, and your questions will vary from client to client. Before you contact the customer, consider interview questions so you have an idea of what you need to produce a compelling case study demonstrating your potential to succeed. At the end of the information-gathering process, you should have a solid understanding of the following to outline how your product was the best solution for the customers’ particular challenge: - The client’s initial challenge

- Why did the client choose your company

- Your company’s approach to the problem

- The solution and implementation process

- The results and final measures of success

Some questions to ask your client during the initial interview: - Can you give a brief description of your company?

- How did you first hear about our product or service?

- What challenges or pain points prompted using our product?

- What were you looking for in a solution to your problem?

- Did you have any roadblocks while using our product?

Don’t forget to talk to your colleagues and get their perspectives on the project when writing your case study. You may also want to include some quotes from internal stakeholders or project leads to make an even more compelling case study. How do you write a case study?When writing a case study, make sure you know who you’re talking to. Your audience, i.e. who would be interested in your product or service, should be your main focus when you create a case study. Once you’ve compiled your facts, format the story so that it will appeal to potential customers. The format and content of case study templates vary, but in general, your business case study should look like a strong landing page: brief, pictorial, and engaging. Xtensio’s case study template includes instructional copy to show you everything you need to know to create a real-life example of your company’s strengths. The template is organized into sections and modules designed to make your case study flow like a well-planned story and we’ve broken the template into three main sections: the snapshot, the body and the footer. The Snapshot This section is designed to give a quick overview of your story and prompt readers to want to learn more. Consider it an executive summary, a book cover, or a brief description in an online store. It should have enough information to grab a potential customer’s attention, but not so much that they will stop reading. Include client details, the project name, and a brief description of the problem, as well as quantitative metrics that demonstrate your accomplishment. You can also include the date the case study was originally published here to help potential customers identify if your product or service is a good fit for them right now. This section is the meat of your case study and will focus on customer results. Like any good story, it will have a beginning, a middle and an end. Classic western storytelling uses a pretty standard formula that includes a problem, the approach taken to solve it, the solution and the end results. The body of Xtensio’s case study template is divided into four key areas that align to these story elements: the Challenge, the Approach, the Solution and the Results. Here, make sure you explain using your product for a certain use case and describe how your service helped the client. To close your case study, end with a short paragraph about who your company is, as well as your contact information. This is handy if your business case study becomes separated from your company’s website information somehow. If you plan on sharing the case study online, make sure to add the links to your website and social media handles, using our social media module. If you are planning to print, then don’t forget to spell out the name of your website and/or add a contact phone number and email address. Invite feedback and participation by your colleagues and the client by inviting them to collaborate on the case study template in real-time. Once you are satisfied with your case study, you can add it to your website, share it on your social channels, use it in presentations, or send out emails to potential clients. You can also download a pdf version that can be printed and shared.  Design, manage and share beautiful living documents… easily, together. Explore Xtensio - Click and edit anything… together.

- Customize to match your branding.

- Share with a link, present, embed or download.

Related to the Case Study TemplateFully customizable templates that you can make your own.  See All Templates Teams use Xtensio to craft and share beautiful living documents .259,673 users and counting..  Jerome Katz Professor of Entrepreneurship @ St. Louis University  Jake Peters  Robin Bramman Founder and Chief Brand Mixologist @  Olakunle Oladehin Executive Director @ Everybody Dance Now!  Aaron Friedland The Walking School Bus  Trailblazer360  Stephen Paterson Chief Product Officer @ AND Digital  Teamspace for beautiful living documents . 259,673 users and counting…  How Technology Marketers Lead the Way in AI Experimentation [New Research] - by Robert Rose

- | Published: February 21, 2024

- | Trends and Research

In a 20-minute demo, the sales engineer deftly clicked through the interface, configured a new image set, assigned the metadata, and set the rights-management properties. He logged in as different users to demonstrate a sophisticated workflow. Then, he published an asset and showed how the system presented it in channel-specific formats. No fewer than five times, he mentioned how “easy” it was for the business user to do what once only experts could do. I interrupted him. “Here’s the thing,” I said, “That isn’t easy for someone who doesn’t understand what you’re doing.” As technology marketers, what you offer to the world seems simple from the outside. You provide a new tool to help your customers do something they couldn’t before acquiring it. But the more amazing the thing they can now do, the more skilled they usually need to be at using it. Said another way, a chainsaw in the hands of a lumberjack is a simple tool. But in my hands? It’s an ER trip waiting to happen. Today, businesses work with some of the most sophisticated digital technology and interfaces in any industry. But that doesn’t make technology easier to market. It still involves a complex and difficult journey made more challenging by how quickly things change. We looked at the answers of 272 technology marketers who responded to CMI’s July 2023 survey to find out. (For more information about the full study of 1,084 marketers, see B2B Content Marketing Benchmarks, Budgets, and Trends .) One not-too-surprising finding: Tech content marketers outpace their marketing peers in AI use. More than two-thirds (79%) of tech marketers say they use AI compared with 72% of B2B marketers as a whole and only 58% of enterprise marketers. What else to expect this year? Technology marketers say they’ll focus on these things in 2024: - Increasing traffic, leads, and sales

- Nurturing existing clients

- Leveraging AI for content creation while ensuring authentic, quality content

- Enhancing content creation processes and systems

- Focusing on thought leadership

- Measuring content performance and value.

The most common trends mentioned center around: - AI proliferation in content creation — with concerns about authenticity and oversaturation.

- Authenticity and uniqueness — valuing human-created content that stands out from AI-generated noise, prioritizing quality over quantity.

- AI’s impact on SEO and content ranking — changes in SEO strategies to accommodate AI algorithms, emphasizing FAQ-oriented and thought leadership content.

- Increased personalization — hyper-personalized content delivery using AI-driven tools to cater to individual personas or niche segments.

Let’s look deeper into the research sponsored by Foundry , an IDG, Inc. company . Table of contentsTeam structure Content marketing challenges Use of content types, distribution channels, and paid channels Social media use Content management and operations Measurement and goals Success factors Budgets and spending Action steps MethodologyAi use: 79% of technology marketers use generative tools. Many respondents predicted a rise in the use of AI to generate content . In fact, 79% say they already use AI for content-related tasks. How? More than half (53%) use generative AI to brainstorm new topics. Around half use the tools to write drafts (48%) and research headlines and keywords (43%). Fewer said they use AI to outline assignments (29%), proofread (19%), generate graphics/images (10%), and create videos (7%) and audio (7%).  Most don’t pay for generative AI tools (yet)Of those using generative AI tools, 88% use free tools (e.g., ChatGPT ). Thirty-seven percent use tools embedded in their content creation/management systems, and 30% pay for tools like Writer and Jasper . AI in content remains mostly ungovernedWhen asked if their organizations have guidelines for using generative AI tools, 26% said yes, 63% said no, and 11% were unsure.  “Change, especially rapid change, is not something most organizations adapt to quickly,” says Yadin Porter de León , global content marketing executive. “The capabilities of generative AI tools currently represent a form of rapid change that very few people can even grasp. So, it’s no surprise that very few companies have created or communicated guidelines for its use … because they don’t know how.” Yadin says marketers should: - Educate your team members so that they can be, at the very least, AI-literate.

- Establish an AI council to organize activities across the organization.

- Establish clear policies and guidelines for using AI.

- Identify use cases for the business and run pilot projects guided by those principles.

How AI is changing SEOIn the open-ended responses, several respondents predicted AI’s significant impact on SEO. How will AI’s integration in search engines shift technology marketers’ SEO strategy? Here’s what we found: Twenty-seven percent say they’re not doing any of those things, while 29% say they’re unsure, suggesting that many may be doing little to nothing. Now is the time to act. Ryan Brock , chief solution officer at DemandJump, says, “The days of building a keyword list based on metrics like search volume are over … at least for now. Until the dust settles and we collectively figure out what kinds of answers we trust Bard (now known as Gemini) with and which ones will always require a more thoughtful comparison of sources to find, we’ve got to use topical authority as the North Star for our tactical content decisions.” Ryan thinks of it this way: “I’m still going to be working to answer basic questions as part of my pillar content strategy, but I also acknowledge that answering them works more to build a foundation of topical authority than to drive immediate, convertible traffic. “Those traffic and conversion-driving queries will become harder to come by than they’ve ever been, so when I find one I need to rank well for, I should be able to do so quickly and efficiently. Competing on a query-by-query level just doesn’t work when every business in a sector sees the same dwindling number of targets. “Building interconnected, ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ style networks of pillar content is the best way to lay the proper topical authority foundation so you can rank fast when you find a term that’s ripe for true thought leadership.” Team structure: How does the work get done?Generative AI isn’t the only issue affecting content marketing these days. We also asked marketers about how they organize their teams . Among larger technology companies (100-plus employees), more than half (54%) say content requests go through a centralized content team. Others say each department/brand produces its own content (22%), and the departments/brand/products share responsibility (20%). Three percent indicate other, while 1% say they outsource it.  Content strategies integrate with marketing, comms, and salesSeventy percent say their organizations integrate content strategy into the overall marketing sales/communication/strategy, and 2% say it’s integrated into another strategy. Fourteen percent say content in marketing is a stand-alone strategy, and 4% say it’s a stand-alone strategy for all content produced by the company. Eight percent say they don’t have a content strategy. The remaining 2% say other or are unsure. Employee churn means new teammates; content teams experience enlightened leadershipThirty-three percent of technology marketers say team members resigned in the last year, 28% say team members were laid off, and about half (51%) say they had new team members acclimating to their ways of working. While team members come and go, the understanding of content doesn’t. Fifty percent strongly agree, and 30% somewhat agree that the leader to whom their content team reports understands the work they do. Only 14% disagree. The remaining 6% neither agree nor disagree. And remote work seems well-tolerated: Only 21% say collaboration is challenging due to remote or hybrid work. Content marketing challenges: The right content, lack of resourcesMost technology marketers (61%) cite creating the right content for their audience as a challenge. Other content creation challenges include differentiating content (58%), creating content consistently (49%), creating quality content (43%), optimizing for SEO (43%), creating enough content to keep up with internal demand (40%), and creating content that requires technical skills (36%). One in four (25%) say they are challenged to create enough content to keep up with external demand.  Other hurdlesThe most frequently cited non-creation challenge, by far, is a lack of resources (66%), followed by aligning content efforts across sales and marketing (52%) and aligning content with the buyer’s journey (52%). Forty-five percent say they have difficulty accessing subject matter experts, and 44% say they are challenged with workflow issues/content approval processes. Only 28% cite keeping up with new technologies as a challenge, 27% pick a lack of strategy, 12% say keeping up with privacy rules, and 13% point to tech integration issues.  Use of content types, distribution channels, and paid channels: Staying at the topWe asked technology marketers about the types of content they produce, their distribution channels , and paid content promotion. We also asked which formats and channels produce the best results. Popular content types and formatsAs in the previous year, the three most popular content types are short articles/posts (96%), case studies/customer stories (93%), and videos (90%). Eighty-two percent use thought leadership e-books/white papers, 81% use long articles/posts, 63% use data visualizations/visual content, 62% use product/technical data sheets, and 56% use research reports. Less than half of technology marketers use brochures (45%), interactive content (35%), livestreaming content (34%), and audio content (31%).  Effective content types and formatsWhich formats are most effective? Fifty-nine percent say case studies/customer stories deliver some of the best results. Almost as many (57%) name thought leadership e-books/white papers. Slightly more than half say research reports (53%) and videos (51%).  Popular content distribution channelsRegarding the channels used to distribute content, 90% use blogs and social media platforms (organic), followed by webinars (79%), email newsletters (78%), and email (74%). Sixty-four percent use in-person events, and 58% use digital events. Less frequently used channels include: - Microsites (40%)

- Podcasts (30%)

- Hybrid events (24%)

- Branded online communities (23%)

- Digital magazines (21%)

- Direct mail (19%)

- Online learning platform (18%)

- Print magazines (12%)

- Mobile apps (7%)

- Separate content brands (3%).

Effective content distribution channelsWhich channels perform the best? Most surveyed tech marketers point to webinars (56%) and in-person events (53%). Forty-four percent say blogs, 43% pick email, and 37% say social media platforms (organic).  Popular paid content channelsWhen technology marketers pay to promote content , which channels do they invest in? Ninety-three percent use paid content distribution channels. Of those, 77% use social media advertising/promoted posts, 71% use sponsorships, 70% use search engine marketing/pay-per-click, and 66% use digital display advertising. Around one in three use native advertising (38%) and partner emails (33%). Far fewer invest in print display advertising (11%).  Effective paid content channelsSearch engine marketing and pay-per-click produce good results, according to 61% of tech marketers. Fifty-three percent say sponsorships deliver good results, followed by social media advertising/promoted posts (43%) and partner emails (34%).  Social media use: One platform rises way aboveWhen asked which organic social media platforms deliver the best value for their organization, technology marketers (92%) pick LinkedIn. Twenty-seven percent cite YouTube as a top performer, 18% say Facebook, and 10% pick Instagram and Twitter. Only 1% cite TikTok.  It makes sense that 73% say they increased their use of LinkedIn over the last 12 months, while only 36% boosted their YouTube presence, 19% increased Instagram use, 15% grew their Facebook presence, 12% increased X use, and 9% increased TikTok use. Which platforms are marketers giving up? Did you guess X? You’re right — 34% of marketers say they decreased their X use. Twenty-four percent reduced their use of Facebook, with 14% decreasing on Instagram and YouTube, 3% pulling back on TikTok, and only 2% decreasing their use of LinkedIn. Interestingly, we saw a significant rise in technology marketers who use TikTok: 17% say they use the platform, which is triple from last year (5%).  Content management and operations: The right tech isn’t a guaranteeTo explore how teams manage content, we asked tech marketers about their technology use and investments and the challenges they face scaling their content . Content management technologyAmong the technologies used to manage content, technology marketers point to: - Analytics tools (82%)

- Social media publishing/analytics (73%)

- Email marketing software (71%)

- Content creation/calendaring/collaboration/workflow (66%)

- Content management system (58%)

- Customer relationship management system (57%)

- Marketing automation system (38%)

- Sales enablement platform (30%)

- Digital asset management (DAM) system (24%)

But having technology doesn’t mean it’s the right technology (or its capabilities are used). Only 29% say they have the right tech to manage content across the organization. Thirty-two percent say they have the technology but aren’t using its potential, and 28% say they haven’t acquired the right technology. Eleven percent are unsure.  Even so, 40% of technology marketers say their organization is likely to invest in new technology in 2024; however, another 39% say it’s unlikely. Twenty-one percent say their organization is neither likely nor unlikely to invest.  Scaling content productionThis year, we introduced a new question to understand what challenges technology marketers face while scaling content production . Almost half (49%) say it’s a lack of communication across silos, and the same number say it’s not enough content repurposing. Thirty-one percent say they have no structured content production process, and 29% say they lack an editorial calendar with clear deadlines. Six percent say scaling is not a current focus. Among the other hurdles are difficulty locating digital content assets (19%), translation/localization issues (17%), technology issues (15%), and no style guide (13%).  Measurement and goals: Generating sales and revenue risesAlmost half (43%) of technology marketers agree their organization measures content performance effectively — but the same amount (43%) disagree. Thirteen percent neither agree nor disagree. Only 1% say they don’t measure content performance. The four most frequently used metrics to assess content performance are conversions (77%), website traffic (73%), email engagement (72%), and website engagement (70%). Sixty percent say they rely on quality of leads, 58% use social media analytics, 55% rely on search ratings, and 52% say quantity of leads. Less than half use tracking the cost to acquire a lead, subscriber, and/or customer (32%) and email subscribers (31%).  The most common challenge measuring content performance experienced by technology marketers is integrating/correlating data across multiple platforms (88%), followed by extracting insights from data (82%), tying performance data to goals (81%), organizational goal setting (73%), and lack of training (71%).  Among the goals assisted by content marketing, 82% of technology marketers say it created brand awareness in the last 12 months. Eighty percent say it helped generate demands/leads, 71% say it helped nurture subscribers/audiences/leads, and 61% say it helped generate sales revenue (up from 48% the previous year). Less than half say it helped grow loyalty with existing clients/customers (46%), grow a subscribed audience (42%), and reduce customer support costs (14%).  Success factors: Know your audienceTo separate top performers from the pack, we asked technology marketers to assess the success of their content marketing. Twenty-seven percent rate the organization’s success as extremely or very successful. Another 58% report moderate success, and 15% feel minimally or not at all successful. The most common factor for successful technology marketers is knowing their audience (81%). That success factor makes sense because “creating the right content for our audience” is the top challenge. Top-performing content marketers prioritize knowing their audiences to create the right content for those audiences. Top performers also set goals that align with their organization’s objectives (74%), have a documented strategy (67%), and collaborate with other teams (64%). Thought leadership (62%) and effectively measuring and demonstrating content performance (59%) also help top technology performers reach content marketing success.  Several other dimensions identify the differentiators of top technology performers: - 75% of the most successful say they’re backed by leaders who understand their work. In contrast, just 50% of all tech respondents feel their leaders understand.

- They’re less likely to report a lack of resources (57% of top performers say they lack resources vs. 66% of all tech content marketers).

- They’re more likely to have the right content management technologies. About half (49%) of the top performers say they have the technology they need, compared with 29% of all tech marketers.

- Nearly three-fourths (74%) of top performers say they measure content performance effectively, compared with 43% of the whole set of tech marketers.

- They are more likely to use content marketing successfully to create brand awareness (96% vs. 82%), nurture subscribers/audiences/leads (82% vs. 71%), generate sales/revenue (81% vs. 61%), grow loyalty with existing customers/clients (64% vs. 46%), and grow a subscribed audience (57% vs. 42%).

Little difference exists between top performers and all respondents when it comes to the adoption of generative AI tools and related guidelines.  Budgets and spending: Holding steadyTo explore budget plans for 2024, we asked technology marketers about their knowledge of their organization’s budget/budgeting process for content marketing. Of the 53% who have knowledge of their budgets, we followed up to assess the specifics. Content marketing as a percentage of total marketing spendHere’s what they say about the total marketing budget (excluding salaries): - 18% say content marketing consumes at least one-fourth of the total marketing budget.

- More than one in three (37%) indicate that 10% to 24% of the marketing budget goes to content marketing.

- Just under half (45%) say less than 10% of the marketing budget goes to content marketing.

Content marketing budget outlook for 2024Forty-eight percent think their content marketing budget will increase this year compared with 2023, whereas 39% think it will stay the same. Only 7% think it will decrease, and 6% are unsure.  Where will the budget go?Next, we asked where respondents plan to increase their spending. Sixty-nine percent of technology marketers say they would increase their investment in video, followed by in-person events (60%), thought leadership content (54%), webinars (41%), paid advertising (40%), online community building (27%), audio content (22%), digital events (21%), and hybrid events (11%).  Of course, content doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Kami Buckner , HPC solutions marketing manager at Dell Technologies, notes that content must be integrated into a larger plan and support the customer journey by driving them to other content. “Videos, in-person events, and thought leadership content may rank similarly in this survey because they are often developed to complement each other,” she says. “Thought leadership content is an important component of any event plan, and videos are an effective peripheral asset that can engage an audience to generate interest in downloading long-form thought leadership pieces, generate excitement before and after events, and be displayed at the event.” For example, Dell developed a 15-second video to use on social media to drive viewers to a landing page, which hosted the 60-second sizzle reel to promote an upcoming event. We also: - Launched thought leadership content around the video and event.

- Created and displayed another video at the event highlighting key points in the new thought leadership content that could be shared post-event.

- Developed a virtual reality experience for the event that built credibility for Dell Technologies, both hosting and serving thought leadership content.

Action steps: What tech marketers should doThese results from tech marketers reflect what we find across other B2B organizations. You should know your audience, lean into brand awareness, integrate data across the buyer’s journey, and invest more in thought leadership, events, and video. But what should you prioritize as a technology marketer? Given where you are in 2024 and your relationship with modern technology, put these three things at the top of your list: - Lean into the brand and develop relationships early and often . Marketing pundits laugh at the idea of technology companies developing “relationships” with audiences and buyers. They cynically surmise, “Nobody wants a relationship with their hydraulic actuator provider.” That may be true, but it doesn’t relieve you from trying. Today’s world makes it more imperative that technology companies differentiate, not just by providing the fastest, cheapest, easiest, or most scalable product on the market. You must also differentiate by helping customers be the best versions of themselves. As I used to say to my marketing team, “Our competitive advantage isn’t that we help people become better digital asset managers; it’s that we help digital asset managers become better people.” That leads to the second action.

- Grow owned media’s importance in your products and services. A differentiating strategy provides a reason for people to engage with you outside the small portion of their lives that goes into their buying journey. Owned media experiences create an ecosystem of value for your customers in the pre- and post-buying journey, foster a competitive advantage, and celebrate the complexity your products inherently induce. Yes, your tools are complex and sophisticated and do amazing things. Let you be the source of how to do those things better than anyone else.

- Connect first-party data. How you connect your buyers’ digital interactions will be the fabric that develops better relationships with your customers. If you understand their true intentions, needs, and wants, and more importantly, how they evolve, you can optimize every experience that leads and follows a sale. Of course, you likely must make big changes to implement any one or all three of these action steps. An audit, where you examine all your customers’ content-driven experiences along their journey, can help you develop a plan for which ones to keep, which should change, and which should be sunset for good. Creating this ecosystem gives you the power to transform what is seen as overly complex and hard into a worthwhile evolution and innovation. Your technology is not there to make the customer’s journey “easy” — it’s there to make it “worth it!”