Gun Control Essay: Important Topics, Examples, and More

Gun Control Definition

Gun control refers to the regulation of firearms to reduce the risk of harm caused by their misuse. It is an important issue that has garnered much attention in recent years due to the increasing number of gun-related incidents, including mass shootings and homicides. Writing an essay about gun control is important because it allows one to explore the various aspects of this complex and controversial topic, including the impact of gun laws on public safety, the constitutional implications of gun control, and the social and cultural factors that contribute to gun violence.

In writing an essay on gun control, conducting thorough research, considering multiple perspectives, and developing a well-informed argument is important. This may involve analyzing existing gun control policies and their effectiveness, exploring the attitudes and beliefs of different groups towards firearms, and examining the historical and cultural context of gun ownership and use. Through this process, one can develop a nuanced understanding of the issue and propose effective solutions to address the problem of gun violence.

Further information on writing essays on gun control can be found in various sources, including academic journals, policy reports, and news articles. In the following paragraphs, our nursing essay writing services will provide tips and resources to help you write an effective and informative guns essay. Contact our custom writer and get your writing request satisfied in a short term.

Gun Control Essay Types

There are various types of essays about gun control, each with its own unique focus and approach. From analyzing the effectiveness of existing gun laws to exploring the cultural and historical context of firearms in society, the possibilities for exploring this topic are virtually endless.

Let's look at the following types and examples from our essay writing service USA :

- Argumentative Essay : This essay clearly argues for or against gun control laws. The writer must use evidence to support their position and refute opposing arguments.

- Descriptive Essay: A descriptive essay on gun control aims to provide a detailed topic analysis. The writer must describe the history and evolution of gun laws, the different types of firearms, and their impact on society.

- Cause and Effect Essay: This type of essay focuses on why gun control laws are necessary, the impact of gun violence on society, and the consequences of not having strict gun control laws.

- Compare and Contrast Essay: In this type of essay, the writer compares and contrasts different countries' gun laws and their effectiveness. They can also compare and contrast different types of guns and their impact on society.

- Expository Essay: This type of essay focuses on presenting facts and data on the topic of gun control. The writer must explain the different types of gun laws, their implementation, and their impact on society.

- Persuasive Essay: The writer of a persuasive essay aims to persuade the reader to support their position on gun control. They use a combination of facts, opinions, and emotional appeals to convince the reader.

- Narrative Essay: A narrative essay on gun control tells a story about an individual's experience with gun violence. It can be a personal story or a fictional one, but it should provide insight into the human impact of gun violence.

In the following paragraphs, we will provide an overview of the most common types of gun control essays and some tips and resources to help you write them effectively. Whether you are a student, a researcher, or simply someone interested in learning more about this important issue, these essays can provide valuable insight and perspective on the complex and often controversial topic of gun control.

Persuasive Essay on Gun Control

A persuasive essay on gun control is designed to convince the reader to support a specific stance on gun control policies. To write an effective persuasive essay, the writer must use a combination of facts, statistics, and emotional appeals to sway the reader's opinion. Here are some tips from our expert custom writer to help you write a persuasive essay on gun control:

- Research : Conduct thorough research on gun control policies, including their history, effectiveness, and societal impact. Use credible sources to back up your argument.

- Develop a thesis statement: In your gun control essay introduction, the thesis statement should clearly state your position on gun control and provide a roadmap for your paper.

- Use emotional appeals: Use emotional appeals to connect with your reader. For example, you could describe the impact of gun violence on families and communities.

- Address opposing viewpoints: Address opposing viewpoints and provide counterarguments to strengthen your position.

- Use statistics: Use statistics to back up your argument. For example, you could use statistics to show the correlation between gun control laws and reduced gun violence.

- Use rhetorical devices: Use rhetorical devices, such as metaphors and analogies, to help the reader understand complex concepts.

Persuasive gun control essay examples include:

- The Second Amendment does not guarantee an individual's right to own any firearm.

- Stricter gun control laws are necessary to reduce gun violence in the United States.

- The proliferation of guns in society leads to more violence and higher crime rates.

- Gun control laws should be designed to protect public safety while respecting individual rights.

Argumentative Essay on Gun Control

A gun control argumentative essay is designed to present a clear argument for or against gun control policies. To write an effective argumentative essay, the writer must present a well-supported argument and refute opposing arguments. Here are some tips to help you write an argumentative essay on gun control:

- Choose a clear stance: Choose a clear stance on gun control policies and develop a thesis statement that reflects your position.

- Research : Conduct extensive research on gun control policies and use credible sources to back up your argument.

- Refute opposing arguments: Anticipate opposing arguments and provide counterarguments to strengthen your position.

- Use evidence: Use evidence to back up your argument. For example, you could use data to show the correlation between gun control laws and reduced gun violence.

- Use logical reasoning: Use logical reasoning to explain why your argument is valid.

Examples of argumentative essay topics on gun control include:

- Gun control laws infringe upon individuals' right to bear arms and protect themselves.

- Gun control laws are ineffective and do not prevent gun violence.

If you'd rather have a professional write you a flawless paper, you can always contact us and buy argumentative essay .

Do You Want to Ease Your Academic Burden?

Order a rhetorical analysis essay from our expert writers today and experience the power of top-notch academic writing.

How to Choose a Good Gun Control Topic: Tips and Examples

Choosing a good gun control topic can be challenging, but with some careful consideration, you can select an interesting and relevant topic. Here are seven tips for choosing a good gun control topic with examples:

- Consider current events: Choose a topic that is current and relevant. For example, the impact of the pandemic on gun control policies.

- Narrow your focus: Choose a specific aspect of gun control to focus on, such as the impact of gun control laws on crime rates.

- Consider your audience: Consider who your audience is and what they are interested in. For example, a topic that appeals to gun enthusiasts might be the ethics of owning firearms.

- Research : Conduct extensive research on gun control policies and current events. For example, the impact of the Second Amendment on gun control laws.

- Choose a controversial topic: Choose a controversial topic that will generate discussion. For example, the impact of the NRA on gun control policies.

- Choose a topic that interests you: You can choose an opinion article on gun control that you are passionate about and interested in. For example, the impact of mass shootings on public opinion of gun control.

- Consider different perspectives: Consider different perspectives on gun control and choose a topic that allows you to explore multiple viewpoints. For example, the effectiveness of background checks in preventing gun violence.

You can also buy an essay online cheap from our professional writers. Knowing that you are getting high-quality, customized work will give you the peace of mind and confidence you need to succeed!

Pro-Gun Control Essay Topics

Here are pro-gun control essay topics that can serve as a starting point for your research and writing, helping you to craft a strong and persuasive argument.

- Stricter gun control laws are necessary to reduce gun violence in America.

- The Second Amendment was written for a different time and should be updated to reflect modern society.

- Gun control and gun safety laws can prevent mass shootings and other forms of gun violence.

- Owning a gun should be a privilege, not a right.

- Universal background checks should be mandatory for all gun purchases.

- The availability of assault weapons should be severely restricted.

- Concealed carry permits should be harder to obtain and require more rigorous training.

- The gun lobby has too much influence on government policy.

- The mental health of gun owners should be considered when purchasing firearms.

- Gun violence has a significant economic impact on communities and the nation as a whole.

- There is a strong correlation between high gun ownership rates and higher gun violence rates.

- Gun control policies can help prevent suicides and accidental shootings.

- Gun control policies should be designed to protect public safety while respecting individual rights.

- More research is needed on the impact of gun control policies on gun violence.

- The impact of gun violence on children and young people is a significant public health issue.

- Gun control policies should be designed to reduce the illegal gun trade and access to firearms by criminals.

- The right to own firearms should not override the right to public safety.

- The government has a responsibility to protect its citizens from gun violence.

- Gun control policies are compatible with the Second Amendment.

- International examples of successful gun control policies can be applied in America.

Anti-Gun Control Essay Topics

These topics against gun control essay can help you develop strong and persuasive arguments based on individual rights and the importance of personal freedom.

- Gun control laws infringe on the Second Amendment and individual rights.

- Stricter gun laws will not prevent criminals from obtaining firearms.

- Gun control laws are unnecessary and will only burden law-abiding citizens.

- Owning a gun is a fundamental right and essential for self-defense.

- Gun-free zones create a false sense of security and leave people vulnerable.

- A Gun control law will not stop mass school shootings, as these are often premeditated and planned.

- The government cannot be trusted to enforce gun control laws fairly and justly.

- Gun control laws unfairly target law-abiding gun owners and punish them for the actions of a few.

- Gun ownership is a part of American culture and heritage and should not be restricted.

- Gun control laws will not stop criminals from using firearms to commit crimes.

- Gun control laws often ignore the root causes of gun violence, such as mental illness and poverty.

- Gun control laws will not stop terrorists from using firearms to carry out attacks.

- Gun control laws will only create a black market for firearms, making it easier for criminals to obtain them.

- Gun control laws will not stop domestic violence, as abusers will find other ways to harm their victims.

- Gun control laws will not stop drug cartels and organized crime from trafficking firearms.

- Gun control laws will not stop gang violence and turf wars.

- Gun control laws are an infringement on personal freedom and individual responsibility.

- Gun control laws are often rooted in emotion rather than reason and evidence.

- Gun control laws ignore the important role that firearms play in hunting and sport shooting.

- More gun control laws will only give the government more power and control over its citizens.

Example Essays

Whether you have been assigned to write a gun control research paper or essay, the tips provided above should help you grasp the general idea of how to cope with this task. Now, to give you an even better understanding of the task and set you on the right track, here are a few excellent examples of well-written papers on this topic:

Don’t forget that you always have a reliable essay writing service USA by your side to which you can entrust writing a brilliant essay for you!

Final Words

In conclusion, writing a sample rhetorical analysis essay requires careful analysis and effective use of persuasive techniques. Whether you are a high school student or a college student, mastering the art of rhetorical analysis can help you become a more effective communicator and critical thinker. With practice and perseverance, anyone can become a skilled writer and excel in their academic pursuits.

And if you're overwhelmed or unsure about writing your next AP lang rhetorical analysis essay, don't worry - we're here to help! Our friendly and experienced research paper writers are ready to guide you through the process, providing expert advice and support every step of the way. So why not take the stress out of writing and let us help you succeed? Buy essay today and take the first step toward academic excellence!

Looking to Take Your Academic Performance to the Next Level?

Say goodbye to stress, endless research, and sleepless nights - and hello to a brighter academic future. Place your order now and watch your grades soar!

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

%20(1).webp)

- Share full article

Gun Control, Explained

A quick guide to the debate over gun legislation in the United States.

By The New York Times

As the number of mass shootings in America continues to rise , gun control — a term used to describe a wide range of restrictions and measures aimed at controlling the use of firearms — remains at the center of heated discussions among proponents and opponents of stricter gun laws.

To help understand the debate and its political and social implications, we addressed some key questions on the subject.

Is gun control effective?

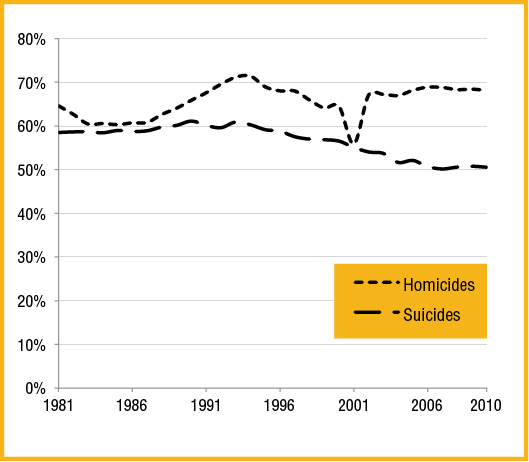

Throughout the world, mass shootings have frequently been met with a common response: Officials impose new restrictions on gun ownership. Mass shootings become rarer. Homicides and suicides tend to decrease, too.

After a British gunman killed 16 people in 1987, the country banned semiautomatic weapons like the ones he had used. It did the same with most handguns after a school shooting in 1996. It now has one of the lowest gun-related death rates in the developed world.

In Australia, a 1996 massacre prompted mandatory gun buybacks in which, by some estimates , as many as one million firearms were then melted into slag. The rate of mass shootings plummeted .

Only the United States, whose rate and severity of mass shootings is without parallel outside conflict zones, has so consistently refused to respond to those events with tightened gun laws .

Several theories to explain the number of shootings in the United States — like its unusually violent societal, class and racial divides, or its shortcomings in providing mental health care — have been debunked by research. But one variable remains: the astronomical number of guns in the country.

America’s gun homicide rate was 33 per one million people in 2009, far exceeding the average among developed countries. In Canada and Britain, it was 5 per million and 0.7 per million, respectively, which also corresponds with differences in gun ownership. Americans sometimes see this as an expression of its deeper problems with crime, a notion ingrained, in part, by a series of films portraying urban gang violence in the early 1990s. But the United States is not actually more prone to crime than other developed countries, according to a landmark 1999 study by Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins of the University of California, Berkeley. Rather, they found, in data that has since been repeatedly confirmed , that American crime is simply more lethal. A New Yorker is just as likely to be robbed as a Londoner, for instance, but the New Yorker is 54 times more likely to be killed in the process. They concluded that the discrepancy, like so many other anomalies of American violence, came down to guns. More gun ownership corresponds with more gun murders across virtually every axis: among developed countries , among American states , among American towns and cities and when controlling for crime rates. And gun control legislation tends to reduce gun murders, according to a recent analysis of 130 studies from 10 countries. This suggests that the guns themselves cause the violence. — Max Fisher and Josh Keller, Why Does the U.S. Have So Many Mass Shootings? Research Is Clear: Guns.

Every mass shooting is, in some sense, a fringe event, driven by one-off factors like the ideology or personal circumstances of the assailant. The risk is impossible to fully erase.

Still, the record is confirmed by reams of studies that have analyzed the effects of policies like Britain’s and Australia’s: When countries tighten gun control laws, it leads to fewer guns in private citizens’ hands, which leads to less gun violence.

What gun control measures exist at the federal level?

Much of current federal gun control legislation is a baseline, governing who can buy, sell and use certain classes of firearms, with states left free to enact additional restrictions.

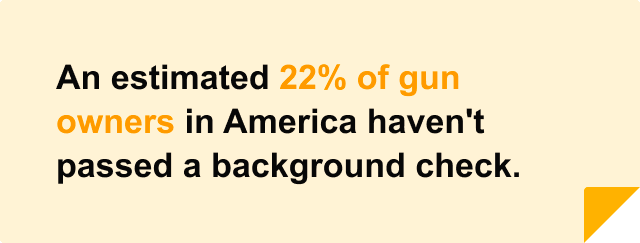

Dealers must be licensed, and run background checks to ensure their buyers are not “prohibited persons,” including felons or people with a history of domestic violence — though private sellers at gun shows or online marketplaces are not required to run background checks. Federal law also highly restricts the sale of certain firearms, such as fully automatic rifles.

The most recent federal legislation , a bipartisan effort passed last year after a gunman killed 19 children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, expanded background checks for buyers under 21 and closed what is known as the boyfriend loophole. It also strengthened existing bans on gun trafficking and straw purchasing.

— Aishvarya Kavi

Advertisement

What are gun buyback programs and do they work?

Gun buyback programs are short-term initiatives that provide incentives, such as money or gift cards, to convince people to surrender firearms to law enforcement, typically with no questions asked. These events are often held by governments or private groups at police stations, houses of worship and community centers. Guns that are collected are either destroyed or stored.

Most programs strive to take guns off the streets, provide a safe place for firearm disposal and stir cultural changes in a community, according to Gun by Gun , a nonprofit dedicated to preventing gun violence.

The first formal gun buyback program was held in Baltimore in 1974 after three police officers were shot and killed, according to the authors of the book “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States.” The initiative collected more than 13,000 firearms, but failed to reduce gun violence in the city. Hundreds of other buyback programs have since unfolded across the United States.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton announced the nation’s first federal gun buyback program . The $15 million program provided grants of up to $500,000 to police departments to buy and destroy firearms. Two years later, the Senate defeated efforts to extend financing for the program after the Bush administration called for it to end.

Despite the popularity of gun buyback programs among certain anti-violence and anti-gun advocates, there is little data to suggest that they work. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research , a private nonprofit, found that buyback programs adopted in U.S. cities were ineffective in deterring gun crime, firearm-related homicides or firearm-related suicides. . Evidence showed that cities set the sale price of a firearm too low to considerably reduce the supply of weapons; most who participated in such initiatives came from low-crime areas and firearms that were typically collected were either older or not in good working order.

Dr. Brendan Campbell, a pediatric surgeon at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and an author of one chapter in “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States,” said that buyback programs should collect significantly more firearms than they currently do in order to be more effective.

Dr. Campbell said they should also offer higher prices for handguns and assault rifles. “Those are the ones that are most likely to be used in crime,” and by people attempting suicide, he said. “If you just give $100 for whatever gun, that’s when you’ll end up with all these old, rusted guns that are a low risk of causing harm in the community.”

Mandatory buyback programs have been enacted elsewhere around the world. After a mass shooting in 1996, Australia put in place a nationwide buyback program , collecting somewhere between one in five and one in three privately held guns. The initiative mostly targeted semiautomatic rifles and many shotguns that, under new laws, were no longer permitted. New Zealand banned military-style semiautomatic weapons, assault rifles and some gun parts and began its own large-scale buyback program in 2019, after a terrorist attack on mosques in Christchurch. The authorities said that more than 56,000 prohibited firearms had been collected from about 32,000 people through the initiative.

Where does the U.S. public stand on the issue?

Expanded background checks for guns purchased routinely receive more than 80 or 90 percent support in polling.

Nationally, a majority of Americans have supported stricter gun laws for decades. A Gallup poll conducted in June found that 55 percent of participants were in favor of a ban on the manufacture, possession and sale of semiautomatic guns. A majority of respondents also supported other measures, including raising the legal age at which people can purchase certain firearms, and enacting a 30-day waiting period for gun sales.

But the jumps in demand for gun control that occur after mass shootings also tend to revert to the partisan mean as time passes. Gallup poll data shows that the percentage of participants who supported stricter gun laws receded to 57 percent in October from 66 percent in June, which was just weeks after mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo. A PDK poll conducted after the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde found that 72 percent of Republicans supported arming teachers, in contrast with 24 percent of Democrats.

What do opponents of gun control argue?

Opponents of gun control, including most Republican members of Congress, argue that proposals to limit access to firearms infringe on the right of citizens to bear arms enshrined in the Second Amendment to the Constitution. And they contend that mass shootings are not the result of easily accessible guns, but of criminals and mentally ill people bent on waging violence.

— Annie Karni

Why is it so hard to push for legislation?

Polling suggests that Americans broadly support gun control measures, yet legislation is often stymied in Washington, and Republicans rarely seem to pay a political price for their opposition.

The calculation behind Republicans’ steadfast stonewalling of any new gun regulations — even in the face of the kind unthinkable massacres like in Uvalde, Texas — is a fairly simple one for Senator Kevin Cramer of North Dakota. Asked what the reaction would be from voters back home if he were to support any significant form of gun control, the first-term Republican had a straightforward answer: “Most would probably throw me out of office,” he said. His response helps explain why Republicans have resisted proposals such as the one for universal background checks for gun buyers, despite remarkably broad support from the public for such plans — support that can reach up to 90 percent nationwide in some cases. Republicans like Mr. Cramer understand that they would receive little political reward for joining the push for laws to limit access to guns, including assault-style weapons. But they know for certain that they would be pounded — and most likely left facing a primary opponent who could cost them their job — for voting for gun safety laws or even voicing support for them. Most Republicans in the Senate represent deeply conservative states where gun ownership is treated as a sacred privilege enshrined in the Constitution, a privilege not to be infringed upon no matter how much blood is spilled in classrooms and school hallways around the country. Though the National Rifle Association has recently been diminished by scandal and financial turmoil , Democrats say that the organization still has a strong hold on Republicans through its financial contributions and support, hardening the party’s resistance to any new gun laws. — Carl Hulse, “ Why Republicans Won’t Budge on Guns .”

Yet while the power of the gun lobby, the outsize influence of rural states in the Senate and single-voter issues offer some explanation, there is another possibility: voters.

When voters in four Democratic-leaning states got the opportunity to enact expanded gun or ammunition background checks into law, the overwhelming support suggested by national surveys was nowhere to be found. For Democrats, the story is both unsettling and familiar. Progressives have long been emboldened by national survey results that show overwhelming support for their policy priorities, only to find they don’t necessarily translate to Washington legislation and to popularity on Election Day or beyond. President Biden’s major policy initiatives are popular , for example, yet voters say he has not accomplished much and his approval ratings have sunk into the low 40s. The apparent progressive political majority in the polls might just be illusory. Public support for new gun restrictions tends to rise in the wake of mass shootings. There is already evidence that public support for stricter gun laws has surged again in the aftermath of the killings in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas. While the public’s support for new restrictions tends to subside thereafter, these shootings or another could still produce a lasting shift in public opinion. But the poor results for background checks suggest that public opinion may not be the unequivocal ally of gun control that the polling makes it seem. — Nate Cohn, “ Voters Say They Want Gun Control. Their Votes Say Something Different. ”

Argumentative Gun Control

This essay about gun control examines the intense debate surrounding the issue in the United States, balancing arguments for stricter regulations against the constitutional right to bear arms. Advocates for tighter gun laws argue that such measures would decrease the high rates of gun violence by mirroring successful policies from other countries. In contrast, opponents believe that the focus should be on addressing mental health and crime rather than restricting gun ownership, asserting that guns are necessary for personal protection and that current laws need better enforcement rather than new restrictions. The essay suggests that a balanced approach might be most effective, respecting the Second Amendment while implementing reasonable limitations to enhance public safety. This complex issue calls for a thoughtful exploration of both individual rights and community safety.

How it works

The discourse concerning firearm regulation in the United States persists as a highly contentious matter, fracturing communities and frequently straddling the boundary between individual autonomy and communal security. This exposition delves into the myriad arguments encircling firearm control, scrutinizing both the advocacy for stricter protocols to mitigate firearm-related harm and the rebuttals advocating for unhindered access to firearms, as enshrined by the Second Amendment.

At the crux of the argument for enhanced firearm control lies the nexus between facile access to firearms and the heightened incidence of firearm-related harm in the U.

S. Advocates for firearm control often underscore data showcasing a correlation between firearm possession rates and occurrences of firearm-related fatalities. These proponents posit that nations with stringent firearm control statutes, such as Japan and the United Kingdom, witness markedly fewer instances of firearm-related incidents vis-à-vis the U.S. They posit that instituting analogous regulations—such as thorough background evaluations, obligatory waiting intervals, and constraints on firearm varieties—might plausibly curtail the frequency and gravity of mass shootings and firearm-related homicides.

Conversely, adversaries of more stringent firearm control contend that firearms are not inherently problematic; instead, they attribute issues of mental wellness and criminality as the crux of firearm violence. They contend that the entitlement to possess firearms is constitutionally safeguarded, accentuating the Second Amendment’s guarantee of the right to retain and bear arms. This faction argues that possessing a firearm is indispensable for personal safeguarding and that firearm control statutes would not inherently thwart malefactors from illicitly procuring firearms. Instead, they advocate for enhanced mental health provisions and more efficacious law enforcement as panaceas for firearm violence.

Additionally, there exists the discourse concerning the efficacy of extant firearm statutes. Opponents of heightened firearm control protocols highlight that numerous locales with elevated rates of firearm violence, such as Chicago, already impose rigorous firearm statutes. They argue that these stipulations have failed to ameliorate firearm offenses, positing that novel statutes would likely encounter similar inefficacies. This standpoint engenders the proposal that rather than promulgating fresh statutes, there should be a concerted focus on enforcing extant statutes more effectively and attending to other contributors to violence.

Despite the dichotomous perspectives, the dialogue encompassing firearm control is in a state of flux, particularly in the aftermath of recurrent mass shootings. This has prompted some to advocate for an equitable approach that upholds the Second Amendment while integrating judicious restrictions to ensure communal security. For instance, propositions like comprehensive background evaluations garner extensive public backing, including among firearm possessors. The objective is not to interdict responsible firearm ownership but to forestall access to firearms by individuals predisposed to their irresponsible utilization.

In summation, the discourse on firearm control is intricate and deeply entrenched within American cultural and political terrains. While there exists palpable evidence suggesting that heightened firearm control could precipitate a reduction in firearm violence, the preservation of constitutional entitlements and apprehensions regarding the efficacy of such statutes convolute the discourse. A nuanced strategy that amalgamates respect for individual entitlements with a dedication to communal security might offer the most viable avenue for diminishing firearm-related harm without transgressing the liberties enshrined by the Constitution. This intricate issue mandates meticulous discourse and judicious action from all stakeholders implicated.

Cite this page

Argumentative Gun Control. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/

"Argumentative Gun Control." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Argumentative Gun Control . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/ [Accessed: 28 Aug. 2024]

"Argumentative Gun Control." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed August 28, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/

"Argumentative Gun Control," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/. [Accessed: 28-Aug-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Argumentative Gun Control . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/argumentative-gun-control/ [Accessed: 28-Aug-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2019

The psychology of guns: risk, fear, and motivated reasoning

- Joseph M. Pierre 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 159 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

256k Accesses

30 Citations

434 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Politics and international relations

- Social policy

The gun debate in America is often framed as a stand-off between two immutable positions with little potential to move ahead with meaningful legislative reform. Attempts to resolve this impasse have been thwarted by thinking about gun ownership attitudes as based on rational choice economics instead of considering the broader socio-cultural meanings of guns. In this essay, an additional psychological perspective is offered that highlights how concerns about victimization and mass shootings within a shared culture of fear can drive cognitive bias and motivated reasoning on both sides of the gun debate. Despite common fears, differences in attitudes and feelings about guns themselves manifest in variable degrees of support for or opposition to gun control legislation that are often exaggerated within caricatured depictions of polarization. A psychological perspective suggests that consensus on gun legislation reform can be achieved through understanding differences and diversity on both sides of the debate, working within a common middle ground, and more research to resolve ambiguities about how best to minimize fear while maximizing personal and public safety.

Discounting risk

Do guns kill people or do people kill people? Answers to that riddle draw a bright line between two sides of a caricatured debate about guns in polarized America. One side believes that guns are a menace to public safety, while the other believes that they are an essential tool of self-preservation. One side cannot fathom why more gun control legislation has not been passed in the wake of a disturbing rise in mass shootings in the US and eyes Australia’s 1996 sweeping gun reform and New Zealand’s more recent restrictions with envy. The other, backed by the Constitutional right to bear arms and the powerful lobby of the National Rifle Association (NRA), fears the slippery slope of legislative change and refuses to yield an inch while threatening, “I’ll give you my gun when you pry it from my cold, dead hands”. With the nation at an impasse, meaningful federal gun legislation aimed at reducing firearm violence remains elusive.

Despite the 1996 Dickey Amendment’s restriction of federal funding for research on gun violence by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Rostron, 2018 ), more than 30 years of public health research supports thinking of guns as statistically more of a personal hazard than a benefit. Case-control studies have repeatedly found that gun ownership is associated with an increased risk of gun-related homicide or suicide occurring in the home (Kellermann and Reay, 1986 ; Kellermann et al., 1993 ; Cummings and Koepsell, 1998 ; Wiebe, 2003 ; Dahlberg et al., 2004 ; Hemenway, 2011 ; Anglemeyer et al., 2014 ). For homicides, the association is largely driven by gun-related violence committed by family members and other acquaintances, not strangers (Kellermann et al., 1993 , 1998 ; Wiebe, 2003 ).

If having a gun increases the risk of gun-related violent death in the home, why do people choose to own guns? To date, the prevailing answer from the public health literature has been seemingly based on a knowledge deficit model that assumes that gun owners are unaware of risks and that repeated warnings about “overwhelming evidence” of “the health risk of a gun in the home [being] greater than the benefit” (Hemenway, 2011 ) should therefore decrease gun ownership and increase support for gun legislation reform. And yet, the rate of US households with guns has held steady for two decades (Smith and Son, 2015 ) with owners amassing an increasing number of guns such that the total civilian stock has risen to some 265 million firearms (Azrael et al., 2017 ). This disparity suggests that the knowledge deficit model is inadequate to explain or modify gun ownership.

In contrast to the premise that people weigh the risks and benefits of their behavior based on “rational choice economics” (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ), nearly 50 years of psychology and behavioral economics research has instead painted a picture of human decision-making as a less than rational process based on cognitive short-cuts (“availability heuristics”) and other error-prone cognitive biases (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974 ; Kunda, 1990 ; Haselton and Nettle, 2006 ; Hibert, 2012 ). As a result, “consequentialist” approaches to promoting healthier choices are often ineffective. Following this perspective, recent public health efforts have moved beyond educational campaigns to apply an understanding of the psychology of risky behavior to strike a balance between regulation and behavioral “nudges” aimed at reducing harmful practices like smoking, unhealthy eating, texting while driving, and vaccine refusal (Atchley et al., 2011 ; Hansen et al., 2016 ; Matjasko et al., 2016 ; Pluviano et al., 2017 ).

A similar public health approach aimed at reducing gun violence should take into account how gun owners discount the risks of ownership according to cognitive biases and motivated reasoning. For example, cognitive dissonance may lead those who already own guns to turn a blind eye to research findings about the dangers of ownership. Optimism bias, the general tendency of individuals to overestimate good outcomes and underestimate bad outcomes, can likewise make it easy to disregard dangers by externalizing them to others. The risk of suicide can therefore be dismissed out of hand based on the rationale that “it will never happen to me,” while the risk of homicide can be discounted based on demographic factors. Kleck and Gertz ( 1998 ) noted that membership in street gangs and drug dealing might be important confounds of risk in case control studies, just as unsafe storage practices such as keeping a firearm loaded and unlocked may be another (Kellerman et al., 1993 ). Other studies have found that the homicide risk associated with guns in the home is greater for women compared to men and for non-whites compared to whites (Wiebe, 2003 ). Consequently, white men—by far the largest demographic that owns guns—might be especially likely to think of themselves as immune to the risks of gun ownership and, through confirmation bias, cherry-pick the data to support pre-existing intuitions and fuel motivated disbelief about guns. These testable hypotheses warrant examination in future research aimed at understanding the psychology of gun ownership and crafting public health approaches to curbing gun violence.

Still, while the role of cognitive biases should be integrated into a psychological understanding of attitudes towards gun ownership, cognitive biases are universal liabilities that fall short of explaining why some people might “employ” them as a part of motivated reasoning to support ownership or to oppose gun reform. To understand the underlying motivation that drives cognitive bias, a deeper analysis of why people own guns is required. In the introductory essay to this journal’s series on “What Guns Mean,” Metzl ( 2019 ) noted that public health efforts to reduce firearm ownership have failed to “address beliefs about guns among people who own them”. In a follow-up piece, Galea and Abdalla ( 2019 ) likewise suggested that the gun debate is complicated by the fact that “knowledge and values do not align” and that “these values create an impasse, one where knowing is not enough” (Galea and Abdalla, 2019 ). Indeed, these and other authors (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ; Braman and Kahan, 2006 ; Pierre, 2015 ; Kalesan et al., 2016 ) have enumerated myriad beliefs and values, related to the different “symbolic lives” and “social meanings” of firearms both within and outside of “gun culture” that drive polarized attitudes towards gun ownership in the US. This essay attempts to further explore the meaning of guns from a psychological perspective.

Fear and gun ownership

Modern psychological understanding of human decision-making has moved beyond availability heuristics and cognitive biases to integrate the role of emotion and affect. Several related models including the “risk-as-feelings hypothesis” (Loewenstein et al., 2001 ), the “affect heuristic” (Slovic et al., 2007 ); and the “appraisal-tendency framework” (Lerner et al., 2015 ) illustrate how emotions can hijack rational-decision-making processes to the point of being the dominant influence on risk assessments. Research has shown that “perceived risk judgments”—estimates of the likelihood that something bad will happen—are especially hampered by emotion (Pachur et al., 2012 ) and that different types of affect can bias such judgments in different ways (Lerner et al., 2015 ). For example, fear can in particular bias assessments away from rational analysis to overestimate risks, as well as to perceive negative events as unpredictable (Lerner et al., 2015 ).

Although gun ownership is associated with positive feelings about firearms within “gun culture” (Pierre, 2015 ; Kalesan et al., 2016 ; Metzl, 2019 ), most research comparing gun owners to non-gun owners suggests that ownership is rooted in fear. While long guns have historically been owned primarily for hunting and other recreational purposes, US surveys dating back to the 1990s have revealed that the most frequent reason for gun ownership and more specifically handgun ownership is self-protection (Cook and Ludwig, 1997 ; Azrael et al., 2017 ; Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Research has likewise shown that the decision to obtain a firearm is largely motivated by past victimization and/or fears of future victimization (Kleck et al., 2011 ; Hauser and Kleck, 2013 ).

A few studies have reported that handgun ownership is associated with past victimization, perceived risk of crime, and perceived ineffectiveness of police protection within low-income communities where these concerns may be congruent with real risks (Vacha and McLaughlin, 2000 , 2004 ). However, gun ownership tends to be lower in urban settings and in low-income families where there might be higher rates of violence and crime (Vacha and McLaughlin, 2000 ). Instead, the largest demographic of gun owners in the US are white men living in rural communities who are earning more than $100K/year (Azrael et al., 2017 ). Mencken and Froese ( 2019 ) likewise reported that gun owners tend to have higher incomes and greater ratings of life happiness than non-owners. These findings suggest a mismatch between subjective fear and objective reality.

Stroebe and colleagues ( 2017 ) reported that the specific perceived risk of victimization and more “diffuse” fears that the world is a dangerous place are both independent predictors of handgun ownership, with perceived risk of assault associated with having been or knowing a victim of violent crime and belief in a dangerous world associated with political conservatism. These findings hint at the likelihood that perceived risk of victimization can be based on vicarious sources with a potential for bias, whether through actual known acquaintances or watching the nightly news, conducting a Google search or scanning one’s social media feed, or reading “The Armed Citizen” column in the NRA newsletter The American Rifleman . It also suggests that a general fear of crime, independent of actual or even perceived individual risk, may be a powerful motivator for gun ownership for some that might track with race and political ideology.

Several authors have drawn a connection between gun ownership and racial tensions by examining the cultural symbolism and socio-political meaning of guns. Bhatia ( 2019 ) detailed how the NRA’s “disinformation campaign reliant on fearmongering” is constructed around a narrative of “fear and identity politics” that exploits current xenophobic sentiments related to immigrants. Metzl ( 2019 ) noted that during the 1960s, conservatives were uncharacteristically in favor of gun control when armed resistance was promoted by Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, and others involved in the Black Power Movement. Today, Metzl argues, “mainstream society reflexively codes white men carrying weapons in public as patriots, while marking armed black men as threats or criminals.” In support of this view, a 2013 study found that having a gun in the home was significantly associated with racism against black people as measured by the Symbolic Racism Scale, noting that “for each 1 point increase in symbolic racism, there was a 50% greater odds of having a gun in the home and a 28% increase in the odds of supporting permits to carry concealed handguns” (O’Brien et al., 2013 ). Hypothesizing that guns are a symbol of hegemonic masculinity that serves to “shore up white male privilege in society,” Stroud ( 2012 ) interviewed a non-random sample of 20 predominantly white men in Texas who had licenses for concealed handgun carry. The men described how guns help to fulfill their identities as protectors of their families, while characterizing imagined dangers with rhetoric suggesting specific fears about black criminals. These findings suggest that gun ownership among white men may be related to a collective identity as “good guys” protecting themselves against “bad guys” who are people of color, a premise echoed in the lay press with headlines like, “Why Are White Men Stockpiling Guns?” (Smith, 2018 ), “Report: White Men Stockpile Guns Because They’re Afraid of Black People” (Harriott, 2018 ), and “Gun Rights Are About Keeping White Men on Top” (Wuertenberg, 2018 ).

Connecting the dots, the available evidence therefore suggests that for many gun owners, fears about victimization can result in confirmation, myside, and optimism biases that not only discount the risks of ownership, but also elevate the salience of perceived benefit, however remote, as it does when one buys a lottery ticket (Rogers and Webley, 2001 ). Indeed, among gun owners there is widespread belief that having a gun makes one safer, supported by published claims that where there are “more guns”, there is “less crime” (Lott, 1998 , 1999 ) as well as statistics and anecdotes about successful defensive gun use (DGU) (Kleck and Gertz, 1995 , 1998 ; Tark and Kleck, 2004 ; Cramer and Burnett, 2012 ). Suffice it to say that there have been numerous debates about how to best interpret this body of evidence, with critics claiming that “more guns, less crime” is a myth (Ayres and Donohue, 2003 ; Moyer, 2017 ) that has been “discredited” (Wintemute, 2008 ) and that the incidence of DGU has been grossly overestimated and pales in comparison to the risk of being threatened or harmed by a gun in the home (Hemenway, 1997 , 2011 ; Cook and Ludwig, 1998 ; Azrael and Hemenway, 2000 ; Hemenway et al., 2000 ). Attempts at objective analysis have concluded that surveys to date have defined and measured DGU inconsistently with unclear numbers of false positives and false negatives (Smith, 1997 ; McDowall et al., 2000 ; National Research Council, 2005 ; RAND, 2018 ), that the causal effects of DGU on reducing injury are “inconclusive” (RAND, 2018 ), and that “neither side seems to be willing to give ground or see their opponent’s point of view” (Smith, 1997 ). With the scientific debate about DGU mirrored in the lay press (Defilippis and Hughes, 2015 ; Kleck, 2015 ; Doherty, 2015 ), a rational assessment of whether guns make owners safer is hampered by a lack of “settled science”. With no apparent consensus, motivated reasoning can pave the way to the nullification of opposing arguments in favor of personal opinions and ideological stances.

For gun owners, even if it is acknowledged that on average successful DGU is much less likely than a homicide or suicide in the home, not having a gun at all translates to zero chance of self-preservation, which are intolerable odds. The bottom line is that when gun owners believe that owning a gun will make them feel safer, little else may matter. Curiously however, there is conflicting evidence that gun ownership actually decreases fears of victimization (Hauser and Kleck, 2013 ; Dowd-Arrow et al., 2019 ). That gun ownership may not mitigate such fears could help to account for why some individuals go on to acquire multiple guns beyond their initial purchase with US gun owners possessing an average of 5 firearms and 8% of owners having 10 or more (Azrael et al., 2017 ).

Gun owner diversity

A psychological model of the polarized gun debate in America would ideally compare those for or against gun control legislation. However, research to date has instead focused mainly on differences between gun owners and non-gun owners, which has several limitations. For example, of the nearly 70% of Americans who do not own a gun, 36% report that they can see themselves owning one in the future (Pew Research Center, 2017 ) with 11.5% of all gun owners in 2015 having newly acquired one in the previous 5 years (Wertz et al., 2018 ). Gun ownership and non-ownership are therefore dynamic states that may not reflect static ideology. Personal accounts such as Willis’ ( 2010 ) article, “I Was Anti-gun, Until I Got Stalked,” illustrate this point well.

With existing research heavily reliant on comparing gun owners to non-gun owners, a psychological model of gun attitudes in the US will have limited utility if it relies solely on gun owner stereotypes based on their most frequent demographic characteristics. On the contrary, Hauser and Kleck ( 2013 ) have argued that “a more complete understanding of the relationship between fear of crime and gun ownership at the individual level is crucial”. Just so, looking more closely at the diversity of gun owners can reveal important details beyond the kinds of stereotypes that are often used to frame political debates.

Foremost, it must be recognized that not all gun owners are conservative white men with racist attitudes. Over the past several decades, women have comprised 9–14% of US gun owners with the “gender gap” narrowing due to decreasing male ownership (Smith and Son, 2015 ). A 2017 Pew Survey reported that 22% of women in the US own a gun and that female gun owners are just as likely as men to belong to the NRA (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Although the 36% rate of gun ownership among US whites is the highest for any racial demographic, 25% of blacks and 15% of Hispanics report owning guns with these racial groups being significantly more concerned than whites about gun violence in their communities and the US as a whole (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Providing a striking counterpoint to Stroud’s ( 2012 ) interviews of white gun owners in Texas, Craven ( 2017 ) interviewed 11 black gun owners across the country who offered diverse views on guns and the question of whether owning them makes them feel safer, including if confronted by police during a traffic stop. Kelly ( 2019 ) has similarly offered a self-portrait as a female “left-wing anarchist” against the stereotype of guns owners as “Republicans, racist libertarians, and other generally Constitution-obsessed weirdos”. She reminds us that, “there is also a long history of armed community self-defense among the radical left that is often glossed over or forgotten entirely in favor of the Fox News-friendly narrative that all liberals hate guns… when the cops and other fascists see that they’re not the only ones packing, the balance of power shifts, and they tend to reconsider their tactics”.

Although Mencken and Froese ( 2019 ) concluded that “white men in economic distress find comfort in guns as a means to reestablish a sense of individual power and moral certitude,” their study results actually demonstrated that gun owners fall into distinguishable groups based on different levels of “moral and emotional empowerment” imparted by guns. For example, those with low levels of gun empowerment were more likely to be female and to own long guns for recreational purposes such as hunting and collecting. Other research has shown that the motivations to own a gun, and the degree to which gun ownership is related to fear and the desire for self-protection, also varies according to the type of gun (Stroebe et al., 2017 ). Owning guns, owning specific types of guns (e.g. handguns, long guns, and so-called “military style” semi-automatic rifles like AR-15s), carrying a gun in public, and keeping a loaded gun on one’s nightstand all have different psychological implications. A 2015 study reported that new gun owners were younger and more likely to identify as liberal than long-standing gun owners (Wertz et al., 2018 ). Although Kalesan et al. ( 2016 ) found that gun ownership is more likely among those living within a “gun culture” where ownership is prevalent, encouraged, and part of social life, it would therefore be a mistake to characterize gun culture as a monolith.

It would also be a mistake to equate gun ownership with opposition to gun legislation reform or vice-versa. Although some evidence supports a strong association (Wolpert and Gimpel, 1998 ), more recent studies suggest important exceptions to the rule. While only about 30% of the US population owns a gun, over 70% believes that most citizens should be able to legally own them (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Women tend to be more likely than men to support gun control, even when they are gun owners themselves (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ; Mencken and Froese, 2019 ). Older (age 70–79) Americans likewise have some of the highest rates of gun ownership, but also the highest rates of support for gun control (Pederson et al., 2015 ). In Mencken and Froese’s study ( 2019 ), most gun owners reporting lower levels of gun empowerment favored bans on semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity magazines and opposed arming teachers in schools. Kahan and Braman ( 2003 ) theorized that attitudes towards gun control are best understood according to a “cultural theory of risk”. In their study sample, those with “hierarchical” and “individualist” cultural orientations were more likely than those with “egalitarian” views to oppose gun control and these perspectives were more predictive than other variables including political affiliation and fear of crime.

In fact, both gun owners and non-owners report high degrees of support for universal background checks; laws mandating safe gun storage in households with children; and “red flag” laws restricting access to firearms for those hospitalized for mental illness or those otherwise at risk of harming themselves or others, those convicted of certain crimes including public display of a gun in a threatening manner, those subject to temporary domestic violence restraining orders, and those on “no-fly” or other watch lists (Pew Research Center, 2017 ; Barry et al., 2018 ). According to a 2015 survey, the majority of the US public also opposes carrying firearms in public spaces with most gun owners opposing public carry in schools, college campuses, places of worship, bars, and sports stadiums (Wolfson et al., 2017 ). Despite broad public support for gun legislation reform however, it is important to recognize that the threat of gun restrictions is an important driver of gun acquisition (Wallace, 2015 ; Aisch and Keller, 2016 ). As a result, proposals to restrict gun ownership boosted gun sales considerably under the Obama administration (Depetris-Chauvin, 2015 ), whereas gun companies like Remington and United Sporting Companies have since filed for bankruptcy under the Trump administration.

A shared culture of fear

Developing a psychological understanding of attitudes towards guns and gun control legislation in the US that accounts for underlying emotions, motivated reasoning, and individual variation must avoid the easy trap of pathologizing gun owners and dismissing their fears as irrational. Instead, it should consider the likelihood that motivated reasoning underlies opinion on both sides of the gun debate, with good reason to conclude that fear is a prominent source of both “pro-gun” and “anti-gun” attitudes. Although the research on fear and gun ownership summarized above implies that non-gun owners are unconcerned about victimization, a closer look at individual study data reveals both small between-group differences and significant within-group heterogeneity. For example, Stroebe et al.’s ( 2017 ) findings that gun owners had greater mean ratings of belief in a dangerous world, perceived risk of victimization, and the perceived effectiveness of owning a gun for self-defense were based on inter-group differences of <1 point on a 7-point Likert scale. Fear of victimization is therefore a universal fear for gun owners and non-gun owners alike, with important differences in both quantitative and qualitative aspects of those fears. Kahan and Braham ( 2003 ) noted that the gun debate is not so much a debate about the personal risks of gun ownership, as it is a one about which of two potential fears is most salient—that of “firearm casualties in a world with insufficient gun control or that of personal defenselessness in a world with excessive control”.

Although this “shared fear” hypothesis has not been thoroughly tested in existing research, there is general support for it based on evidence that fear is an especially potent influence on risk assessment and decision-making when considering low-frequency catastrophic events (Chanel et al., 2009 ). In addition, biased risk assessments have been linked to individual feelings about a specific activity. Whereas many activities in the real world have both high risk and high benefit, positive attitudes about an activity are associated with biased judgments of low risk and high benefit while negative attitudes are associated with biased judgments of high risk and low benefit (Slovic et al., 2007 ). These findings match those of the gun debate, whereby catastrophic events like mass shootings can result in “probability neglect,” over-estimating the likelihood of risk (Sunstein, 2003 ; Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ) with polarized differences regarding guns as a root cause and gun control as a viable solution. For those that have positive feelings about guns and their perceived benefit, the risk of gun ownership is minimized as discussed above. However, based on findings from psychological research on fear (Loewenstein et al., 2001 ; Slovic et al., 2007 ), the reverse is also likely to be true—those with negative feelings about guns who perceive little benefit to ownership may tend to over-estimate risks. Consistent with this dichotomy, both calls for legislative gun reform, as well as gun purchases increase in the wake of mass shootings (Wallace, 2015 ; Wozniak, 2017 ), with differences primarily predicted by the relative self-serving attributional biases of gun ownership and non-ownership alike (Joslyn and Haider-Markel, 2017 ).

Psychological research has shown that fear is associated with loss of control, with risks that are unfamiliar and uncontrollable perceived as disproportionately dangerous (Lerner et al., 2015 ; Sunstein, 2003 ). Although mass shootings have increased in recent years, they remain extremely rare events and represent a miniscule proportion of overall gun violence. And yet, as acts of terrorism, they occur in places like schools that are otherwise thought of as a suburban “safe spaces,” unlike inner cities where violence is more mundane, and are often given sensationalist coverage in the media. A 2019 Harris Poll found that 79% of Americans endorse stress as a result of the possibility of a mass shooting, with about a third reporting that they “cannot go anywhere without worrying about being a victim” (American Psychological Association, 2019 ). While some evidence suggests that gun owners may be more concerned about mass shootings than non-gun owners (Dowd-Arrow et al., 2019 ), this is again a quantitative difference as with fear of victimization more generally. There is little doubt that parental fears about children being victims of gun violence were particularly heightened in the wake of Columbine (Altheide, 2019 ) and it is likely that subsequent school shootings at Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook Elementary, and Stoneman Douglas High have been especially impactful in the minds of those calling for increasing restrictions on gun ownership. For those privileged to be accustomed to community safety who are less worried about home invasion and have faith in the police to provide protection, fantasizing about “gun free zones” may reflect a desire to recreate safe spaces in the wake of mass shootings that invoke feelings of loss of control.

Altheide ( 2019 ) has argued that mass shootings in the US post-Columbine have been embedding within a larger cultural narrative of terrorism, with “expanded social control and policies that helped legitimate the war on terror”. Sunstein and Zeckhauser ( 2011 ) have similarly noted that following terrorist attacks, the public tends to demand responses from government, favoring precautionary measures that are “not justified by any plausible analysis of expected utility” and over-estimating potential benefits. However, such responses may not only be ineffective, but potentially damaging. For example, although collective anxieties in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks resulted in the rapid implementation of new screening procedures for boarding airplanes, it has been argued that the “theater” of response may have done well to decrease fear without any evidence of actual effectiveness in reducing danger (Graham, 2019 ) while perhaps even increasing overall mortality by avoiding air travel in favor of driving (Sunstein, 2003 ; Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ).

As with the literature on DGU, the available evidence supporting the effectiveness of specific gun laws in reducing gun violence is less than definitive (Koper et al., 2004 ; Hahn et al., 2005 ; Lee et al., 2017 ; Webster and Wintemute, 2015 ), leaving the utility of gun reform legislation open to debate and motivated reasoning. Several authors have argued that even if proposed gun control measures are unlikely to deter mass shooters, “doing something is better than nothing” (Fox and DeLateur, 2014 ) and that ineffective counter-terrorism responses are worthwhile if they reduce public fear (Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ). Crucially however, this perspective fails to consider the impact of gun control legislation on the fears of those who value guns for self-protection. For them, removing guns from law-abiding “good guys” while doing nothing to deter access to the “bad guys” who commit crimes is illogical anathema. Gun owners and gun advocates likewise reject the concept of “safe spaces” and regard the notion of “gun free zones” as a liability that invites rather than prevents acts of terrorism. In other words, gun control proposals designed to decrease fear have the opposite of their intended effect on those who view guns as symbols of personal safety, increasing rather than decreasing their fears independently of any actual effects on gun violence. Such policies are therefore non-starters, and will remain non-starters, for the sizeable proportion of Americans who regard guns as essential for self-preservation.

In 2006, Braman and Kahan noted that “the Great American Gun Debate… has convulsed the national polity for the better part of four decades without producing results satisfactory to either side” and argued that consequentialist arguments about public health risks based on cost–benefit analysis are trumped by the cultural meanings of guns to the point of being “politically inert” (Braman and Kahan, 2006 ). More than a decade later, that argument is iterated in this series on “What Guns Mean”. In this essay, it is further argued that persisting debates about the effectiveness of DGU and gun control legislation are at their heart trumped by shared concerns about personal safety, victimization, and mass shootings within a larger culture of fear, with polarized opinions about how to best mitigate those fears that are determined by the symbolic, cultural, and personal meanings of guns and gun ownership.

Coming full circle to the riddle, “Do guns kill people or do people kill people?”, a psychologically informed perspective rejects the question as a false dichotomy that can be resolved by the statement, “people kill people… with guns”. It likewise suggests a way forward by acknowledging both common fears and individual differences beyond the limited, binary caricature of the gun debate that is mired in endless arguments over disputed facts. For meaningful legislative change to occur, the debate must be steered away from its portrayal as two immutable sides caught between not doing anything on the one hand and enacting sweeping bans or repealing the 2nd Amendment on the other. In reality, public attitudes towards gun control are more nuanced than that, with support or opposition to specific gun control proposals predicted by distinct psychological and cultural factors (Wozniak, 2017 ) such that achieving consensus may prove less elusive than is generally assumed. Accordingly, gun reform proposals should focus on “low hanging fruit” where there is broad support such as requiring and enforcing universal background checks, enacting “red flag” laws balanced by guaranteeing gun ownership rights to law-abiding citizens, and implementing public safety campaigns that promote safe firearm handling and storage. Finally, the Dickey Amendment should be repealed so that research can inform public health interventions aimed at reducing gun violence and so that individuals can replace motivated reasoning with evidence-based decision-making about personal gun ownership and guns in society.

Aisch G, Keller J (2016). What happens after calls for new gun restrictions? Sales go up. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/12/10/us/gun-sales-terrorism-obama-restrictions.html . Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

Altheide DL (2019) The Columbine shootings and the discourse of fear. Am Behav Sci 52:1354–1370

Article Google Scholar

American Psychological Association (2019). One-third of US adults say fear of mass shootings prevents them from going to certain places or events. Press release, 15 August 2019. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2019/08/fear-mass-shooting . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Anglemeyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G (2014) The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Int Med 160:101–110

Google Scholar

Atchley P, Atwood S, Boulton A (2011) The choice to text and drive in younger drivers: behavior may shape attitude. Accid Anal Prev 43:134–142

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ayres I, Donohue III JJ (2003) Shooting down the more guns, less crime hypothesis. Stanf Law Rev 55:1193–1312

Azrael D, Hemenway D (2000) ‘In the safety of your own home’: results from a national survey on gun use at home. Soc Sci Med 50:285–291

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M (2017) The stock and flow of U.S. firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 3:38–57

Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, McGinty EE (2018) Public support for gun violence prevention policies among gun owners and non-gun owners in 2017. Am J Public Health 108:878–881

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bhatia R (2019). Guns, lies, and fear: exposing the NRA’s messaging playbook. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/guns-crime/reports/2019/04/24/468951/guns-lies-fear/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Braman D, Kahan DM (2006) Overcoming the fear of guns, the fear of gun control, and the fear of cultural politics: constructing a better gun debate. Emory Law J 55:569–607

Cook PJ, Ludwig J (1997). Guns in America: National survey on private ownership and use of firearms. National Institute of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/165476.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Chanel O, Chichilnisky G(2009) The influence of fear in decisions: Experimental evidence. J Risk Uncertain 39(3):271–298

Article MATH Google Scholar

Cook PJ, Ludwig J (1998) Defensive gun use: new evidence from a national survey. J Quant Criminol 14:111–131

Cramer CE, Burnett D (2012). Tough targets: when criminals face armed resistance from citizens. Cato Institute https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/WP-Tough-Targets.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Craven J (2017). Why black people own guns. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/black-gun-ownership_n_5a33fc38e4b040881bea2f37 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Cummings P, Koepsell TD (1998) Does owning a firearm increase or decrease the risk of death? JAMA 280:471–473

Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow M (2004) Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol 160:929–936

Defilippis E, Hughes D (2015). The myth behind defensive gun ownership: guns are more likely to do harm than good. Politico. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/01/defensive-gun-ownership-myth-114262 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Depetris-Chauvin E (2015) Fear of Obama: an empirical study of the demand for guns and the U.S. 2008 presidential election. J Pub Econ 130:66–79

Doherty B (2015). How to count the defensive use of guns: neither survey calls nor media and police reports capture the importance of private gun ownership. Reason. https://reason.com/2015/03/09/how-to-count-the-defensive-use-of-guns/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Dowd-Arrow B, Hill TD, Burdette AM (2019) Gun ownership and fear. SSM Pop Health 8:100463

Fox JA, DeLateur MJ (2014) Mass shootings in America: moving beyond Newtown. Homicide Stud 18:125–145

Galea S, Abdalla SM (2019) The public’s health and the social meaning of guns. Palgrave Comm 5:111

Graham DA. The TSA doesn’t work—and never has. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/the-tsa-doesnt-work-and-maybe-it-doesnt-matter/394673/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Hahn RA, Bilukha O, Crosby A, Fullilove MT, Liberman A, Moscicki E, Synder S, Tuma F, Briss PA, Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2005) Firearms laws and the reduction of violence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 28:40–71

Hansen PG, Skov LR, Skov KL (2016) Making healthy choices easier: regulation versus nudging. Annu Rev Public Health 37:237–51

Harriott M (2018). Report: white men stockpile guns because they’re afraid of black people. The Root. https://www.theroot.com/report-white-men-stockpile-guns-because-they-re-afraid-1823779218 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Haselton MG, Nettle D (2006) The paranoid optimist: an integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10:47–66

Hauser W, Kleck G (2013) Guns and fear: a one-way street? Crime Delinquency 59:271–291

Hemenway (1997) Survey research and self-defense gun use: an explanation of extreme overestimates. J Crim Law Criminol 87:1430–1445

Hemenway D, Azrael D, Miller M (2000) Gun use in the United States: results from two national surveys. Inj Prev 6:263–267

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hemenway D (2011) Risks and benefits of a gun in the home. Am J Lifestyle Med 5:502–511

Hibert M (2012) Toward a synthesis of cognitive biases: how noisy information processing can bias human decision making. Psychol Bull 138:211–237

Joslyn MR, Haider-Markel DP (2017) Gun ownership and self-serving attributions for mass shooting tragedies. Soc Sci Quart 98:429–442

Kahan DM, Braman D (2003) More statistics, less persuasion: a cultural theory of gun-risk perceptions. Univ Penn Law Rev 151:1291–1327

Kalesan B, Villarreal MD, Keyes KM, Galea S (2016) Gun ownership and social gun culture. Inj Prev 22:216–220

Kellermann AL, Reay DT (1986) Protection or peril? An analysis of fire-arm related deaths in the home. N Engl J Med 314:1557–1560

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Rushforth NB, Banton JG, Reay DT, Francisco JT, Locci A, Prodzinski J, Hackman BB, Somes G (1993) Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home. N Engl J Med 329:1084–1091

Kellerman AL, Somes G, Rivara F, Lee R, Banton J (1998) Injuries and deaths due to firearms in the home. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 45:263–267

Kelly K (2019) I’m a left-wing anarchist. Guns aren’t just for right-wingero. Vox. https://www.vox.com/first-person/2019/7/1/18744204/guns-gun-control-anarchism . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kleck G (2015) Defensive gun use is not a myth: why my critics still have it wrong. Politico. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/02/defensive-gun-ownership-gary-kleck-response-115082 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kleck G, Kovandzic T, Saber M, Hauser W (2011) The effect of perceived risk and victimization on plans to purchase a gun for self-protection. J Crim Justice 39:312–319

Kleck G, Gertz M (1995) Armed resistance to crime: the prevalence and nature of self-defense with a gun. J Crim Law Criminol 86:150–187

Kleck G, Gertz M (1998) Carrying guns for protection: results from the national self-defense survey. J Res Crime Delinquency 35:193–224

Koper CS, Woods DJ, Roth JA (2004) An updated assessment of the federal assault weapons ban: impacts on gun markets and gun violence, 1994–2003. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/204431.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol Bull 108:480–498

Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, Avakame E, Srinivasan S, Hemenway D, Monuteaux MC (2017) Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Int Med 177:106–119

Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS (2015) Emotion and decision making. Ann Rev Psychol 66:799–823

Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N (2001) Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull 127:267–286

Lott JR (1998) More guns, less crime. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lott JR (1999) More guns, less crime: a response to Ayres and Donohue. Yale Law & Economics Research paper no. 247 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=248328 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Matjasko JL, Cawley JH, Baker-Goering M, Yokum DV (2016) Applying behavioral economics to public health policy: illustrative examples and promising directions. Am J Prev Med 50:S13–S19

McDowall D, Loftin C, Presser S (2000) Measuring civilian defensive firearm use: a methodological experiment. J Quant Criminol 16:1–19

Mencken FC, Froese P (2019) Gun culture in action. Soc Prob 66:3–27

Metzl J (2019) What guns mean: the symbolic lives of firearms. Palgrave Comm 5:35

Article ADS Google Scholar

Moyer MW (2017). More guns do not stop more crimes, evidence shows. Sci Am https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/more-guns-do-not-stop-more-crimes-evidence-shows/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

National Research Council (2005) Firearms and violence: a critical review. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

O’Brien K, Forrest W, Lynott D, Daly M (2013) Racism, gun ownership and gun control: Biased attitudes in US whites may influence policy decisions. PLoS ONE 8(10):e77552

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Pachur T, Hertwig R, Steinmann F (2012) How do people judge risks: availability heuristic, affect heuristic, or both? J Exp Psychol Appl 18:314–330