- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Hypothesis: Good & Bad Examples

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis is an attempt at explaining a phenomenon or the relationships between phenomena/variables in the real world. Hypotheses are sometimes called “educated guesses”, but they are in fact (or let’s say they should be) based on previous observations, existing theories, scientific evidence, and logic. A research hypothesis is also not a prediction—rather, predictions are ( should be) based on clearly formulated hypotheses. For example, “We tested the hypothesis that KLF2 knockout mice would show deficiencies in heart development” is an assumption or prediction, not a hypothesis.

The research hypothesis at the basis of this prediction is “the product of the KLF2 gene is involved in the development of the cardiovascular system in mice”—and this hypothesis is probably (hopefully) based on a clear observation, such as that mice with low levels of Kruppel-like factor 2 (which KLF2 codes for) seem to have heart problems. From this hypothesis, you can derive the idea that a mouse in which this particular gene does not function cannot develop a normal cardiovascular system, and then make the prediction that we started with.

What is the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction?

You might think that these are very subtle differences, and you will certainly come across many publications that do not contain an actual hypothesis or do not make these distinctions correctly. But considering that the formulation and testing of hypotheses is an integral part of the scientific method, it is good to be aware of the concepts underlying this approach. The two hallmarks of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability (an evaluation standard that was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in 1934) and testability —if you cannot use experiments or data to decide whether an idea is true or false, then it is not a hypothesis (or at least a very bad one).

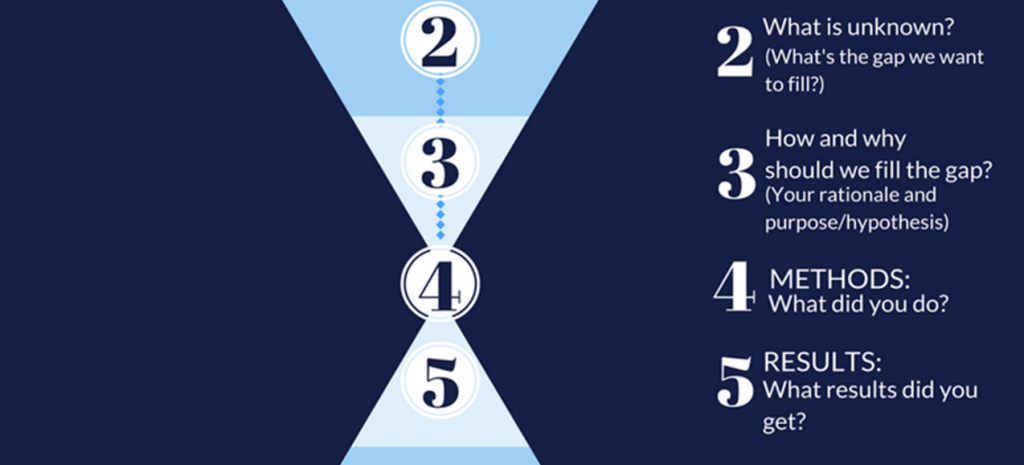

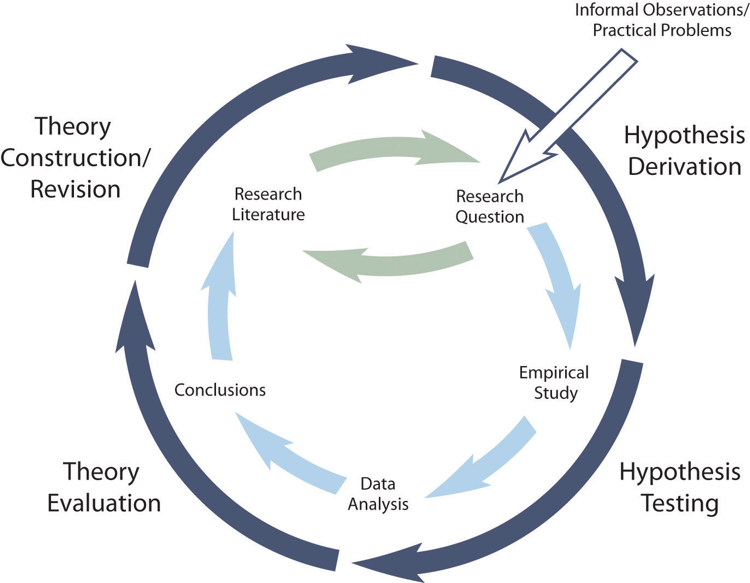

So, in a nutshell, you (1) look at existing evidence/theories, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction that allows you to (4) design an experiment or data analysis to test it, and (5) come to a conclusion. Of course, not all studies have hypotheses (there is also exploratory or hypothesis-generating research), and you do not necessarily have to state your hypothesis as such in your paper.

But for the sake of understanding the principles of the scientific method, let’s first take a closer look at the different types of hypotheses that research articles refer to and then give you a step-by-step guide for how to formulate a strong hypothesis for your own paper.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be simple , which means they describe the relationship between one single independent variable (the one you observe variations in or plan to manipulate) and one single dependent variable (the one you expect to be affected by the variations/manipulation). If there are more variables on either side, you are dealing with a complex hypothesis. You can also distinguish hypotheses according to the kind of relationship between the variables you are interested in (e.g., causal or associative ). But apart from these variations, we are usually interested in what is called the “alternative hypothesis” and, in contrast to that, the “null hypothesis”. If you think these two should be listed the other way round, then you are right, logically speaking—the alternative should surely come second. However, since this is the hypothesis we (as researchers) are usually interested in, let’s start from there.

Alternative Hypothesis

If you predict a relationship between two variables in your study, then the research hypothesis that you formulate to describe that relationship is your alternative hypothesis (usually H1 in statistical terms). The goal of your hypothesis testing is thus to demonstrate that there is sufficient evidence that supports the alternative hypothesis, rather than evidence for the possibility that there is no such relationship. The alternative hypothesis is usually the research hypothesis of a study and is based on the literature, previous observations, and widely known theories.

Null Hypothesis

The hypothesis that describes the other possible outcome, that is, that your variables are not related, is the null hypothesis ( H0 ). Based on your findings, you choose between the two hypotheses—usually that means that if your prediction was correct, you reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative. Make sure, however, that you are not getting lost at this step of the thinking process: If your prediction is that there will be no difference or change, then you are trying to find support for the null hypothesis and reject H1.

Directional Hypothesis

While the null hypothesis is obviously “static”, the alternative hypothesis can specify a direction for the observed relationship between variables—for example, that mice with higher expression levels of a certain protein are more active than those with lower levels. This is then called a one-tailed hypothesis.

Another example for a directional one-tailed alternative hypothesis would be that

H1: Attending private classes before important exams has a positive effect on performance.

Your null hypothesis would then be that

H0: Attending private classes before important exams has no/a negative effect on performance.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A nondirectional hypothesis does not specify the direction of the potentially observed effect, only that there is a relationship between the studied variables—this is called a two-tailed hypothesis. For instance, if you are studying a new drug that has shown some effects on pathways involved in a certain condition (e.g., anxiety) in vitro in the lab, but you can’t say for sure whether it will have the same effects in an animal model or maybe induce other/side effects that you can’t predict and potentially increase anxiety levels instead, you could state the two hypotheses like this:

H1: The only lab-tested drug (somehow) affects anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

You then test this nondirectional alternative hypothesis against the null hypothesis:

H0: The only lab-tested drug has no effect on anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

How to Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper

Now that we understand the important distinctions between different kinds of research hypotheses, let’s look at a simple process of how to write a hypothesis.

Writing a Hypothesis Step:1

Ask a question, based on earlier research. Research always starts with a question, but one that takes into account what is already known about a topic or phenomenon. For example, if you are interested in whether people who have pets are happier than those who don’t, do a literature search and find out what has already been demonstrated. You will probably realize that yes, there is quite a bit of research that shows a relationship between happiness and owning a pet—and even studies that show that owning a dog is more beneficial than owning a cat ! Let’s say you are so intrigued by this finding that you wonder:

What is it that makes dog owners even happier than cat owners?

Let’s move on to Step 2 and find an answer to that question.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 2:

Formulate a strong hypothesis by answering your own question. Again, you don’t want to make things up, take unicorns into account, or repeat/ignore what has already been done. Looking at the dog-vs-cat papers your literature search returned, you see that most studies are based on self-report questionnaires on personality traits, mental health, and life satisfaction. What you don’t find is any data on actual (mental or physical) health measures, and no experiments. You therefore decide to make a bold claim come up with the carefully thought-through hypothesis that it’s maybe the lifestyle of the dog owners, which includes walking their dog several times per day, engaging in fun and healthy activities such as agility competitions, and taking them on trips, that gives them that extra boost in happiness. You could therefore answer your question in the following way:

Dog owners are happier than cat owners because of the dog-related activities they engage in.

Now you have to verify that your hypothesis fulfills the two requirements we introduced at the beginning of this resource article: falsifiability and testability . If it can’t be wrong and can’t be tested, it’s not a hypothesis. We are lucky, however, because yes, we can test whether owning a dog but not engaging in any of those activities leads to lower levels of happiness or well-being than owning a dog and playing and running around with them or taking them on trips.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 3:

Make your predictions and define your variables. We have verified that we can test our hypothesis, but now we have to define all the relevant variables, design our experiment or data analysis, and make precise predictions. You could, for example, decide to study dog owners (not surprising at this point), let them fill in questionnaires about their lifestyle as well as their life satisfaction (as other studies did), and then compare two groups of active and inactive dog owners. Alternatively, if you want to go beyond the data that earlier studies produced and analyzed and directly manipulate the activity level of your dog owners to study the effect of that manipulation, you could invite them to your lab, select groups of participants with similar lifestyles, make them change their lifestyle (e.g., couch potato dog owners start agility classes, very active ones have to refrain from any fun activities for a certain period of time) and assess their happiness levels before and after the intervention. In both cases, your independent variable would be “ level of engagement in fun activities with dog” and your dependent variable would be happiness or well-being .

Examples of a Good and Bad Hypothesis

Let’s look at a few examples of good and bad hypotheses to get you started.

Good Hypothesis Examples

Bad hypothesis examples, tips for writing a research hypothesis.

If you understood the distinction between a hypothesis and a prediction we made at the beginning of this article, then you will have no problem formulating your hypotheses and predictions correctly. To refresh your memory: We have to (1) look at existing evidence, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction, and (4) design an experiment. For example, you could summarize your dog/happiness study like this:

(1) While research suggests that dog owners are happier than cat owners, there are no reports on what factors drive this difference. (2) We hypothesized that it is the fun activities that many dog owners (but very few cat owners) engage in with their pets that increases their happiness levels. (3) We thus predicted that preventing very active dog owners from engaging in such activities for some time and making very inactive dog owners take up such activities would lead to an increase and decrease in their overall self-ratings of happiness, respectively. (4) To test this, we invited dog owners into our lab, assessed their mental and emotional well-being through questionnaires, and then assigned them to an “active” and an “inactive” group, depending on…

Note that you use “we hypothesize” only for your hypothesis, not for your experimental prediction, and “would” or “if – then” only for your prediction, not your hypothesis. A hypothesis that states that something “would” affect something else sounds as if you don’t have enough confidence to make a clear statement—in which case you can’t expect your readers to believe in your research either. Write in the present tense, don’t use modal verbs that express varying degrees of certainty (such as may, might, or could ), and remember that you are not drawing a conclusion while trying not to exaggerate but making a clear statement that you then, in a way, try to disprove . And if that happens, that is not something to fear but an important part of the scientific process.

Similarly, don’t use “we hypothesize” when you explain the implications of your research or make predictions in the conclusion section of your manuscript, since these are clearly not hypotheses in the true sense of the word. As we said earlier, you will find that many authors of academic articles do not seem to care too much about these rather subtle distinctions, but thinking very clearly about your own research will not only help you write better but also ensure that even that infamous Reviewer 2 will find fewer reasons to nitpick about your manuscript.

Perfect Your Manuscript With Professional Editing

Now that you know how to write a strong research hypothesis for your research paper, you might be interested in our free AI proofreader , Wordvice AI, which finds and fixes errors in grammar, punctuation, and word choice in academic texts. Or if you are interested in human proofreading , check out our English editing services , including research paper editing and manuscript editing .

On the Wordvice academic resources website , you can also find many more articles and other resources that can help you with writing the other parts of your research paper , with making a research paper outline before you put everything together, or with writing an effective cover letter once you are ready to submit.

How to Write a Hypothesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Introduction

An overview of the research hypothesis, different types of hypotheses, variables in a hypothesis, how to formulate an effective research hypothesis, designing a study around your hypothesis.

The scientific method can derive and test predictions as hypotheses. Empirical research can then provide support (or lack thereof) for the hypotheses. Even failure to find support for a hypothesis still represents a valuable contribution to scientific knowledge. Let's look more closely at the idea of the hypothesis and the role it plays in research.

As much as the term exists in everyday language, there is a detailed development that informs the word "hypothesis" when applied to research. A good research hypothesis is informed by prior research and guides research design and data analysis , so it is important to understand how a hypothesis is defined and understood by researchers.

What is the simple definition of a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about an outcome between two or more variables . It functions as a navigational tool in the research process, directing what you aim to predict and how.

What is the hypothesis for in research?

In research, a hypothesis serves as the cornerstone for your empirical study. It not only lays out what you aim to investigate but also provides a structured approach for your data collection and analysis.

Essentially, it bridges the gap between the theoretical and the empirical, guiding your investigation throughout its course.

What is an example of a hypothesis?

If you are studying the relationship between physical exercise and mental health, a suitable hypothesis could be: "Regular physical exercise leads to improved mental well-being among adults."

This statement constitutes a specific and testable hypothesis that directly relates to the variables you are investigating.

What makes a good hypothesis?

A good hypothesis possesses several key characteristics. Firstly, it must be testable, allowing you to analyze data through empirical means, such as observation or experimentation, to assess if there is significant support for the hypothesis. Secondly, a hypothesis should be specific and unambiguous, giving a clear understanding of the expected relationship between variables. Lastly, it should be grounded in existing research or theoretical frameworks , ensuring its relevance and applicability.

Understanding the types of hypotheses can greatly enhance how you construct and work with hypotheses. While all hypotheses serve the essential function of guiding your study, there are varying purposes among the types of hypotheses. In addition, all hypotheses stand in contrast to the null hypothesis, or the assumption that there is no significant relationship between the variables .

Here, we explore various kinds of hypotheses to provide you with the tools needed to craft effective hypotheses for your specific research needs. Bear in mind that many of these hypothesis types may overlap with one another, and the specific type that is typically used will likely depend on the area of research and methodology you are following.

Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no effect or relationship between the variables being studied. In statistical terms, it serves as the default assumption that any observed differences are due to random chance.

For example, if you're studying the effect of a drug on blood pressure, the null hypothesis might state that the drug has no effect.

Alternative hypothesis

Contrary to the null hypothesis, the alternative hypothesis suggests that there is a significant relationship or effect between variables.

Using the drug example, the alternative hypothesis would posit that the drug does indeed affect blood pressure. This is what researchers aim to prove.

Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis makes a prediction about the relationship between two variables, and only two variables.

For example, "Increased study time results in better exam scores." Here, "study time" and "exam scores" are the only variables involved.

Complex hypothesis

A complex hypothesis, as the name suggests, involves more than two variables. For instance, "Increased study time and access to resources result in better exam scores." Here, "study time," "access to resources," and "exam scores" are all variables.

This hypothesis refers to multiple potential mediating variables. Other hypotheses could also include predictions about variables that moderate the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable .

Directional hypothesis

A directional hypothesis specifies the direction of the expected relationship between variables. For example, "Eating more fruits and vegetables leads to a decrease in heart disease."

Here, the direction of heart disease is explicitly predicted to decrease, due to effects from eating more fruits and vegetables. All hypotheses typically specify the expected direction of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable, such that researchers can test if this prediction holds in their data analysis .

Statistical hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is one that is testable through statistical methods, providing a numerical value that can be analyzed. This is commonly seen in quantitative research .

For example, "There is a statistically significant difference in test scores between students who study for one hour and those who study for two."

Empirical hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is derived from observations and is tested through empirical methods, often through experimentation or survey data . Empirical hypotheses may also be assessed with statistical analyses.

For example, "Regular exercise is correlated with a lower incidence of depression," could be tested through surveys that measure exercise frequency and depression levels.

Causal hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes that one variable causes a change in another. This type of hypothesis is often tested through controlled experiments.

For example, "Smoking causes lung cancer," assumes a direct causal relationship.

Associative hypothesis

Unlike causal hypotheses, associative hypotheses suggest a relationship between variables but do not imply causation.

For instance, "People who smoke are more likely to get lung cancer," notes an association but doesn't claim that smoking causes lung cancer directly.

Relational hypothesis

A relational hypothesis explores the relationship between two or more variables but doesn't specify the nature of the relationship.

For example, "There is a relationship between diet and heart health," leaves the nature of the relationship (causal, associative, etc.) open to interpretation.

Logical hypothesis

A logical hypothesis is based on sound reasoning and logical principles. It's often used in theoretical research to explore abstract concepts, rather than being based on empirical data.

For example, "If all men are mortal and Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal," employs logical reasoning to make its point.

Let ATLAS.ti take you from research question to key insights

Get started with a free trial and see how ATLAS.ti can make the most of your data.

In any research hypothesis, variables play a critical role. These are the elements or factors that the researcher manipulates, controls, or measures. Understanding variables is essential for crafting a clear, testable hypothesis and for the stages of research that follow, such as data collection and analysis.

In the realm of hypotheses, there are generally two types of variables to consider: independent and dependent. Independent variables are what you, as the researcher, manipulate or change in your study. It's considered the cause in the relationship you're investigating. For instance, in a study examining the impact of sleep duration on academic performance, the independent variable would be the amount of sleep participants get.

Conversely, the dependent variable is the outcome you measure to gauge the effect of your manipulation. It's the effect in the cause-and-effect relationship. The dependent variable thus refers to the main outcome of interest in your study. In the same sleep study example, the academic performance, perhaps measured by exam scores or GPA, would be the dependent variable.

Beyond these two primary types, you might also encounter control variables. These are variables that could potentially influence the outcome and are therefore kept constant to isolate the relationship between the independent and dependent variables . For example, in the sleep and academic performance study, control variables could include age, diet, or even the subject of study.

By clearly identifying and understanding the roles of these variables in your hypothesis, you set the stage for a methodologically sound research project. It helps you develop focused research questions, design appropriate experiments or observations, and carry out meaningful data analysis . It's a step that lays the groundwork for the success of your entire study.

Crafting a strong, testable hypothesis is crucial for the success of any research project. It sets the stage for everything from your study design to data collection and analysis . Below are some key considerations to keep in mind when formulating your hypothesis:

- Be specific : A vague hypothesis can lead to ambiguous results and interpretations . Clearly define your variables and the expected relationship between them.

- Ensure testability : A good hypothesis should be testable through empirical means, whether by observation , experimentation, or other forms of data analysis.

- Ground in literature : Before creating your hypothesis, consult existing research and theories. This not only helps you identify gaps in current knowledge but also gives you valuable context and credibility for crafting your hypothesis.

- Use simple language : While your hypothesis should be conceptually sound, it doesn't have to be complicated. Aim for clarity and simplicity in your wording.

- State direction, if applicable : If your hypothesis involves a directional outcome (e.g., "increase" or "decrease"), make sure to specify this. You also need to think about how you will measure whether or not the outcome moved in the direction you predicted.

- Keep it focused : One of the common pitfalls in hypothesis formulation is trying to answer too many questions at once. Keep your hypothesis focused on a specific issue or relationship.

- Account for control variables : Identify any variables that could potentially impact the outcome and consider how you will control for them in your study.

- Be ethical : Make sure your hypothesis and the methods for testing it comply with ethical standards , particularly if your research involves human or animal subjects.

Designing your study involves multiple key phases that help ensure the rigor and validity of your research. Here we discuss these crucial components in more detail.

Literature review

Starting with a comprehensive literature review is essential. This step allows you to understand the existing body of knowledge related to your hypothesis and helps you identify gaps that your research could fill. Your research should aim to contribute some novel understanding to existing literature, and your hypotheses can reflect this. A literature review also provides valuable insights into how similar research projects were executed, thereby helping you fine-tune your own approach.

Research methods

Choosing the right research methods is critical. Whether it's a survey, an experiment, or observational study, the methodology should be the most appropriate for testing your hypothesis. Your choice of methods will also depend on whether your research is quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods. Make sure the chosen methods align well with the variables you are studying and the type of data you need.

Preliminary research

Before diving into a full-scale study, it’s often beneficial to conduct preliminary research or a pilot study . This allows you to test your research methods on a smaller scale, refine your tools, and identify any potential issues. For instance, a pilot survey can help you determine if your questions are clear and if the survey effectively captures the data you need. This step can save you both time and resources in the long run.

Data analysis

Finally, planning your data analysis in advance is crucial for a successful study. Decide which statistical or analytical tools are most suited for your data type and research questions . For quantitative research, you might opt for t-tests, ANOVA, or regression analyses. For qualitative research , thematic analysis or grounded theory may be more appropriate. This phase is integral for interpreting your results and drawing meaningful conclusions in relation to your research question.

Turn data into evidence for insights with ATLAS.ti

Powerful analysis for your research paper or presentation is at your fingertips starting with a free trial.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

5.2 - writing hypotheses.

The first step in conducting a hypothesis test is to write the hypothesis statements that are going to be tested. For each test you will have a null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) and an alternative hypothesis (\(H_a\)).

When writing hypotheses there are three things that we need to know: (1) the parameter that we are testing (2) the direction of the test (non-directional, right-tailed or left-tailed), and (3) the value of the hypothesized parameter.

- At this point we can write hypotheses for a single mean (\(\mu\)), paired means(\(\mu_d\)), a single proportion (\(p\)), the difference between two independent means (\(\mu_1-\mu_2\)), the difference between two proportions (\(p_1-p_2\)), a simple linear regression slope (\(\beta\)), and a correlation (\(\rho\)).

- The research question will give us the information necessary to determine if the test is two-tailed (e.g., "different from," "not equal to"), right-tailed (e.g., "greater than," "more than"), or left-tailed (e.g., "less than," "fewer than").

- The research question will also give us the hypothesized parameter value. This is the number that goes in the hypothesis statements (i.e., \(\mu_0\) and \(p_0\)). For the difference between two groups, regression, and correlation, this value is typically 0.

Hypotheses are always written in terms of population parameters (e.g., \(p\) and \(\mu\)). The tables below display all of the possible hypotheses for the parameters that we have learned thus far. Note that the null hypothesis always includes the equality (i.e., =).

Learn How To Write A Hypothesis For Your Next Research Project!

Undoubtedly, research plays a crucial role in substantiating or refuting our assumptions. These assumptions act as potential answers to our questions. Such assumptions, also known as hypotheses, are considered key aspects of research. In this blog, we delve into the significance of hypotheses. And provide insights on how to write them effectively. So, let’s dive in and explore the art of writing hypotheses together.

Table of Contents

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a crucial starting point in scientific research. It is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. In other words, a hypothesis acts as a foundation for a researcher to build their study.

Here are some examples of well-crafted hypotheses:

- Increased exposure to natural sunlight improves sleep quality in adults.

A positive relationship between natural sunlight exposure and sleep quality in adult individuals.

- Playing puzzle games on a regular basis enhances problem-solving abilities in children.

Engaging in frequent puzzle gameplay leads to improved problem-solving skills in children.

- Students and improved learning hecks.

S tudents using online paper writing service platforms (as a learning tool for receiving personalized feedback and guidance) will demonstrate improved writing skills. (compared to those who do not utilize such platforms).

- The use of APA format in research papers.

Using the APA format helps students stay organized when writing research papers. Organized students can focus better on their topics and, as a result, produce better quality work.

The Building Blocks of a Hypothesis

To better understand the concept of a hypothesis, let’s break it down into its basic components:

- Variables . A hypothesis involves at least two variables. An independent variable and a dependent variable. The independent variable is the one being changed or manipulated, while the dependent variable is the one being measured or observed.

- Relationship : A hypothesis proposes a relationship or connection between the variables. This could be a cause-and-effect relationship or a correlation between them.

- Testability : A hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable, meaning it can be proven right or wrong through experimentation or observation.

Types of Hypotheses

When learning how to write a hypothesis, it’s essential to understand its main types. These include; alternative hypotheses and null hypotheses. In the following section, we explore both types of hypotheses with examples.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1)

This kind of hypothesis suggests a relationship or effect between the variables. It is the main focus of the study. The researcher wants to either prove or disprove it. Many research divides this hypothesis into two subsections:

- Directional

This type of H1 predicts a specific outcome. Many researchers use this hypothesis to explore the relationship between variables rather than the groups.

- Non-directional

You can take a guess from the name. This type of H1 does not provide a specific prediction for the research outcome.

Here are some examples for your better understanding of how to write a hypothesis.

- Consuming caffeine improves cognitive performance. (This hypothesis predicts that there is a positive relationship between caffeine consumption and cognitive performance.)

- Aerobic exercise leads to reduced blood pressure. (This hypothesis suggests that engaging in aerobic exercise results in lower blood pressure readings.)

- Exposure to nature reduces stress levels among employees. (Here, the hypothesis proposes that employees exposed to natural environments will experience decreased stress levels.)

- Listening to classical music while studying increases memory retention. (This hypothesis speculates that studying with classical music playing in the background boosts students’ ability to retain information.)

- Early literacy intervention improves reading skills in children. (This hypothesis claims that providing early literacy assistance to children results in enhanced reading abilities.)

- Time management in nursing students. ( Students who use a nursing research paper writing service have more time to focus on their studies and can achieve better grades in other subjects. )

Null Hypothesis (H0)

A null hypothesis assumes no relationship or effect between the variables. If the alternative hypothesis is proven to be false, the null hypothesis is considered to be true. Usually a null hypothesis shows no direct correlation between the defined variables.

Here are some of the examples

- The consumption of herbal tea has no effect on sleep quality. (This hypothesis assumes that herbal tea consumption does not impact the quality of sleep.)

- The number of hours spent playing video games is unrelated to academic performance. (Here, the null hypothesis suggests that no relationship exists between video gameplay duration and academic achievement.)

- Implementing flexible work schedules has no influence on employee job satisfaction. (This hypothesis contends that providing flexible schedules does not affect how satisfied employees are with their jobs.)

- Writing ability of a 7th grader is not affected by reading editorial example. ( There is no relationship between reading an editorial example and improving a 7th grader’s writing abilities.)

- The type of lighting in a room does not affect people’s mood. (In this null hypothesis, there is no connection between the kind of lighting in a room and the mood of those present.)

- The use of social media during break time does not impact productivity at work. (This hypothesis proposes that social media usage during breaks has no effect on work productivity.)

As you learn how to write a hypothesis, remember that aiming for clarity, testability, and relevance to your research question is vital. By mastering this skill, you’re well on your way to conducting impactful scientific research. Good luck!

Importance of a Hypothesis in Research

A well-structured hypothesis is a vital part of any research project for several reasons:

- It provides clear direction for the study by setting its focus and purpose.

- It outlines expectations of the research, making it easier to measure results.

- It helps identify any potential limitations in the study, allowing researchers to refine their approach.

In conclusion, a hypothesis plays a fundamental role in the research process. By understanding its concept and constructing a well-thought-out hypothesis, researchers lay the groundwork for a successful, scientifically sound investigation.

How to Write a Hypothesis?

Here are five steps that you can follow to write an effective hypothesis.

Step 1: Identify Your Research Question

The first step in learning how to compose a hypothesis is to clearly define your research question. This question is the central focus of your study and will help you determine the direction of your hypothesis.

Step 2: Determine the Variables

When exploring how to write a hypothesis, it’s crucial to identify the variables involved in your study. You’ll need at least two variables:

- Independent variable : The factor you manipulate or change in your experiment.

- Dependent variable : The outcome or result you observe or measure, which is influenced by the independent variable.

Step 3: Build the Hypothetical Relationship

In understanding how to compose a hypothesis, constructing the relationship between the variables is key. Based on your research question and variables, predict the expected outcome or connection. This prediction should be specific, testable, and, if possible, expressed in the “If…then” format.

Step 4: Write the Null Hypothesis

When mastering how to write a hypothesis, it’s important to create a null hypothesis as well. The null hypothesis assumes no relationship or effect between the variables, acting as a counterpoint to your primary hypothesis.

Step 5: Review Your Hypothesis

Finally, when learning how to compose a hypothesis, it’s essential to review your hypothesis for clarity, testability, and relevance to your research question. Make any necessary adjustments to ensure it provides a solid basis for your study.

In conclusion, understanding how to write a hypothesis is crucial for conducting successful scientific research. By focusing on your research question and carefully building relationships between variables, you will lay a strong foundation for advancing research and knowledge in your field.

Hypothesis vs. Prediction: What’s the Difference?

Understanding the differences between a hypothesis and a prediction is crucial in scientific research. Often, these terms are used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings and functions. This segment aims to clarify these differences and explain how to compose a hypothesis correctly, helping you improve the quality of your research projects.

Hypothesis: The Foundation of Your Research

A hypothesis is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. It provides the basis for your research question and is a starting point for an experiment or observational study.

The critical elements for a hypothesis include:

- Specificity: A clear and concise statement that describes the relationship between variables.

- Testability: The ability to test the hypothesis through experimentation or observation.

To learn how to write a hypothesis, it’s essential to identify your research question first and then predict the relationship between the variables.

Prediction: The Expected Outcome

A prediction is a statement about a specific outcome you expect to see in your experiment or observational study. It’s derived from the hypothesis and provides a measurable way to test the relationship between variables.

Here’s an example of how to write a hypothesis and a related prediction:

- Hypothesis: Consuming a high-sugar diet leads to weight gain.

- Prediction: People who consume a high-sugar diet for six weeks will gain more weight than those who maintain a low-sugar diet during the same period.

Key Differences Between a Hypothesis and a Prediction

While a hypothesis and prediction are both essential components of scientific research, there are some key differences to keep in mind:

- A hypothesis is an educated guess that suggests a relationship between variables, while a prediction is a specific and measurable outcome based on that hypothesis.

- A hypothesis can give rise to multiple experiment or observational study predictions.

To conclude, understanding the differences between a hypothesis and a prediction, and learning how to write a hypothesis, are essential steps to form a robust foundation for your research. By creating clear, testable hypotheses along with specific, measurable predictions, you lay the groundwork for scientifically sound investigations.

Here’s a wrap-up for this guide on how to write a hypothesis. We’re confident this article was helpful for many of you. We understand that many students struggle with writing their school research . However, we hope to continue assisting you through our blog tutorial on writing different aspects of academic assignments.

For further information, you can check out our reverent blog or contact our professionals to avail amazing writing services. Paper perk experts tailor assignments to reflect your unique voice and perspectives. Our professionals make sure to stick around till your satisfaction. So what are you waiting for? Pick your required service and order away!

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Calculate Your Order Price

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

Doing Research: A New Researcher’s Guide pp 17–49 Cite as

How Do You Formulate (Important) Hypotheses?

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

10k Accesses

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

Building on the ideas in Chap. 1, we describe formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses as a continuing cycle of clarifying what you want to study, making predictions about what you might find together with developing your reasons for these predictions, imagining tests of these predictions, revising your predictions and rationales, and so on. Many resources feed this process, including reading what others have found about similar phenomena, talking with colleagues, conducting pilot studies, and writing drafts as you revise your thinking. Although you might think you cannot predict what you will find, it is always possible—with enough reading and conversations and pilot studies—to make some good guesses. And, once you guess what you will find and write out the reasons for these guesses you are on your way to scientific inquiry. As you refine your hypotheses, you can assess their research importance by asking how connected they are to problems your research community really wants to solve.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. Getting Started

We want to begin by addressing a question you might have had as you read the title of this chapter. You are likely to hear, or read in other sources, that the research process begins by asking research questions . For reasons we gave in Chap. 1 , and more we will describe in this and later chapters, we emphasize formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses. However, it is important to know that asking and answering research questions involve many of the same activities, so we are not describing a completely different process.

We acknowledge that many researchers do not actually begin by formulating hypotheses. In other words, researchers rarely get a researchable idea by writing out a well-formulated hypothesis. Instead, their initial ideas for what they study come from a variety of sources. Then, after they have the idea for a study, they do lots of background reading and thinking and talking before they are ready to formulate a hypothesis. So, for readers who are at the very beginning and do not yet have an idea for a study, let’s back up. Where do research ideas come from?

There are no formulas or algorithms that spawn a researchable idea. But as you begin the process, you can ask yourself some questions. Your answers to these questions can help you move forward.

What are you curious about? What are you passionate about? What have you wondered about as an educator? These are questions that look inward, questions about yourself.

What do you think are the most pressing educational problems? Which problems are you in the best position to address? What change(s) do you think would help all students learn more productively? These are questions that look outward, questions about phenomena you have observed.

What are the main areas of research in the field? What are the big questions that are being asked? These are questions about the general landscape of the field.

What have you read about in the research literature that caught your attention? What have you read that prompted you to think about extending the profession’s knowledge about this? What have you read that made you ask, “I wonder why this is true?” These are questions about how you can build on what is known in the field.

What are some research questions or testable hypotheses that have been identified by other researchers for future research? This, too, is a question about how you can build on what is known in the field. Taking up such questions or hypotheses can help by providing some existing scaffolding that others have constructed.

What research is being done by your immediate colleagues or your advisor that is of interest to you? These are questions about topics for which you will likely receive local support.

Exercise 2.1

Brainstorm some answers for each set of questions. Record them. Then step back and look at the places of intersection. Did you have similar answers across several questions? Write out, as clearly as you can, the topic that captures your primary interest, at least at this point. We will give you a chance to update your responses as you study this book.

Part II. Paths from a General Interest to an Informed Hypothesis

There are many different paths you might take from conceiving an idea for a study, maybe even a vague idea, to formulating a prediction that leads to an informed hypothesis that can be tested. We will explore some of the paths we recommend.

We will assume you have completed Exercise 2.1 in Part I and have some written answers to the six questions that preceded it as well as a statement that describes your topic of interest. This very first statement could take several different forms: a description of a problem you want to study, a question you want to address, or a hypothesis you want to test. We recommend that you begin with one of these three forms, the one that makes most sense to you. There is an advantage to using all three and flexibly choosing the one that is most meaningful at the time and for a particular study. You can then move from one to the other as you think more about your research study and you develop your initial idea. To get a sense of how the process might unfold, consider the following alternative paths.

Beginning with a Prediction If You Have One

Sometimes, when you notice an educational problem or have a question about an educational situation or phenomenon, you quickly have an idea that might help solve the problem or answer the question. Here are three examples.

You are a teacher, and you noticed a problem with the way the textbook presented two related concepts in two consecutive lessons. Almost as soon as you noticed the problem, it occurred to you that the two lessons could be taught more effectively in the reverse order. You predicted better outcomes if the order was reversed, and you even had a preliminary rationale for why this would be true.

You are a graduate student and you read that students often misunderstand a particular aspect of graphing linear functions. You predicted that, by listening to small groups of students working together, you could hear new details that would help you understand this misconception.

You are a curriculum supervisor and you observed sixth-grade classrooms where students were learning about decimal fractions. After talking with several experienced teachers, you predicted that beginning with percentages might be a good way to introduce students to decimal fractions.

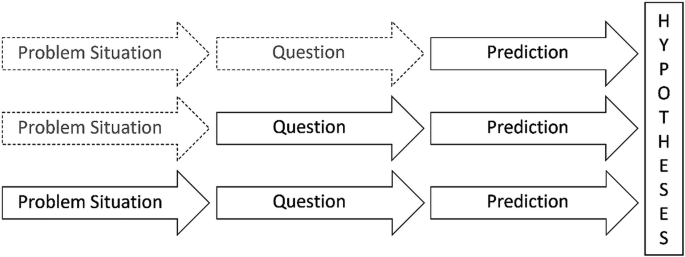

We begin with the path of making predictions because we see the other two paths as leading into this one at some point in the process (see Fig. 2.1 ). Starting with this path does not mean you did not sense a problem you wanted to solve or a question you wanted to answer.

Three Pathways to Formulating Informed Hypotheses

Notice that your predictions can come from a variety of sources—your own experience, reading, and talking with colleagues. Most likely, as you write out your predictions you also think about the educational problem for which your prediction is a potential solution. Writing a clear description of the problem will be useful as you proceed. Notice also that it is easy to change each of your predictions into a question. When you formulate a prediction, you are actually answering a question, even though the question might be implicit. Making that implicit question explicit can generate a first draft of the research question that accompanies your prediction. For example, suppose you are the curriculum supervisor who predicts that teaching percentages first would be a good way to introduce decimal fractions. In an obvious shift in form, you could ask, “In what ways would teaching percentages benefit students’ initial learning of decimal fractions?”

There are advantages to starting with the prediction form if you can make an educated guess about what you will find. Making a prediction forces you to think now about several things you will need to think about at some point anyway. It is better to think about them earlier rather than later. If you state your prediction clearly and explicitly, you can begin to ask yourself three questions about your prediction: Why do I expect to observe what I am predicting? Why did I make that prediction? (These two questions essentially ask what your rationale is for your prediction.) And, how can I test to see if it’s right? This is where the benefits of making predictions begin.

Asking yourself why you predicted what you did, and then asking yourself why you answered the first “why” question as you did, can be a powerful chain of thought that lays the groundwork for an increasingly accurate prediction and an increasingly well-reasoned rationale. For example, suppose you are the curriculum supervisor above who predicted that beginning by teaching percentages would be a good way to introduce students to decimal fractions. Why did you make this prediction? Maybe because students are familiar with percentages in everyday life so they could use what they know to anchor their thinking about hundredths. Why would that be helpful? Because if students could connect hundredths in percentage form with hundredths in decimal fraction form, they could bring their meaning of percentages into decimal fractions. But how would that help? If students understood that a decimal fraction like 0.35 meant 35 of 100, then they could use their understanding of hundredths to explore the meaning of tenths, thousandths, and so on. Why would that be useful? By continuing to ask yourself why you gave the previous answer, you can begin building your rationale and, as you build your rationale, you will find yourself revisiting your prediction, often making it more precise and explicit. If you were the curriculum supervisor and continued the reasoning in the previous sentences, you might elaborate your prediction by specifying the way in which percentages should be taught in order to have a positive effect on particular aspects of students’ understanding of decimal fractions.

Developing a Rationale for Your Predictions

Keeping your initial predictions in mind, you can read what others already know about the phenomenon. Your reading can now become targeted with a clear purpose.

By reading and talking with colleagues, you can develop more complete reasons for your predictions. It is likely that you will also decide to revise your predictions based on what you learn from your reading. As you develop sound reasons for your predictions, you are creating your rationales, and your predictions together with your rationales become your hypotheses. The more you learn about what is already known about your research topic, the more refined will be your predictions and the clearer and more complete your rationales. We will use the term more informed hypotheses to describe this evolution of your hypotheses.

Developing more informed hypotheses is a good thing because it means: (1) you understand the reasons for your predictions; (2) you will be able to imagine how you can test your hypotheses; (3) you can more easily convince your colleagues that they are important hypotheses—they are hypotheses worth testing; and (4) at the end of your study, you will be able to more easily interpret the results of your test and to revise your hypotheses to demonstrate what you have learned by conducting the study.

Imagining Testing Your Hypotheses

Because we have tied together predictions and rationales to constitute hypotheses, testing hypotheses means testing predictions and rationales. Testing predictions means comparing empirical observations, or findings, with the predictions. Testing rationales means using these comparisons to evaluate the adequacy or soundness of the rationales.

Imagining how you might test your hypotheses does not mean working out the details for exactly how you would test them. Rather, it means thinking ahead about how you could do this. Recall the descriptor of scientific inquiry: “experience carefully planned in advance” (Fisher, 1935). Asking whether predictions are testable and whether rationales can be evaluated is simply planning in advance.

You might read that testing hypotheses means simply assessing whether predictions are correct or incorrect. In our view, it is more useful to think of testing as a means of gathering enough information to compare your findings with your predictions, revise your rationales, and propose more accurate predictions. So, asking yourself whether hypotheses can be tested means asking whether information could be collected to assess the accuracy of your predictions and whether the information will show you how to revise your rationales to sharpen your predictions.

Cycles of Building Rationales and Planning to Test Your Predictions

Scientific reasoning is a dialogue between the possible and the actual, an interplay between hypotheses and the logical expectations they give rise to: there is a restless to-and-fro motion of thought, the formulation and rectification of hypotheses (Medawar, 1982 , p.72).

As you ask yourself about how you could test your predictions, you will inevitably revise your rationales and sharpen your predictions. Your hypotheses will become more informed, more targeted, and more explicit. They will make clearer to you and others what, exactly, you plan to study.

When will you know that your hypotheses are clear and precise enough? Because of the way we define hypotheses, this question asks about both rationales and predictions. If a rationale you are building lets you make a number of quite different predictions that are equally plausible rather than a single, primary prediction, then your hypothesis needs further refinement by building a more complete and precise rationale. Also, if you cannot briefly describe to your colleagues a believable way to test your prediction, then you need to phrase it more clearly and precisely.

Each time you strengthen your rationales, you might need to adjust your predictions. And, each time you clarify your predictions, you might need to adjust your rationales. The cycle of going back and forth to keep your predictions and rationales tightly aligned has many payoffs down the road. Every decision you make from this point on will be in the interests of providing a transparent and convincing test of your hypotheses and explaining how the results of your test dictate specific revisions to your hypotheses. As you make these decisions (described in the succeeding chapters), you will probably return to clarify your hypotheses even further. But, you will be in a much better position, at each point, if you begin with well-informed hypotheses.

Beginning by Asking Questions to Clarify Your Interests

Instead of starting with predictions, a second path you might take devotes more time at the beginning to asking questions as you zero in on what you want to study. Some researchers suggest you start this way (e.g., Gournelos et al., 2019 ). Specifically, with this second path, the first statement you write to express your research interest would be a question. For example, you might ask, “Why do ninth-grade students change the way they think about linear equations after studying quadratic equations?” or “How do first graders solve simple arithmetic problems before they have been taught to add and subtract?”

The first phrasing of your question might be quite general or vague. As you think about your question and what you really want to know, you are likely to ask follow-up questions. These questions will almost always be more specific than your first question. The questions will also express more clearly what you want to know. So, the question “How do first graders solve simple arithmetic problems before they have been taught to add and subtract” might evolve into “Before first graders have been taught to solve arithmetic problems, what strategies do they use to solve arithmetic problems with sums and products below 20?” As you read and learn about what others already know about your questions, you will continually revise your questions toward clearer and more explicit and more precise versions that zero in on what you really want to know. The question above might become, “Before they are taught to solve arithmetic problems, what strategies do beginning first graders use to solve arithmetic problems with sums and products below 20 if they are read story problems and given physical counters to help them keep track of the quantities?”

Imagining Answers to Your Questions

If you monitor your own thinking as you ask questions, you are likely to begin forming some guesses about answers, even to the early versions of the questions. What do students learn about quadratic functions that influences changes in their proportional reasoning when dealing with linear functions? It could be that if you analyze the moments during instruction on quadratic equations that are extensions of the proportional reasoning involved in solving linear equations, there are times when students receive further experience reasoning proportionally. You might predict that these are the experiences that have a “backward transfer” effect (Hohensee, 2014 ).

These initial guesses about answers to your questions are your first predictions. The first predicted answers are likely to be hunches or fuzzy, vague guesses. This simply means you do not know very much yet about the question you are asking. Your first predictions, no matter how unfocused or tentative, represent the most you know at the time about the question you are asking. They help you gauge where you are in your thinking.

Shifting to the Hypothesis Formulation and Testing Path

Research questions can play an important role in the research process. They provide a succinct way of capturing your research interests and communicating them to others. When colleagues want to know about your work, they will often ask “What are your research questions?” It is good to have a ready answer.

However, research questions have limitations. They do not capture the three images of scientific inquiry presented in Chap. 1 . Due, in part, to this less expansive depiction of the process, research questions do not take you very far. They do not provide a guide that leads you through the phases of conducting a study.

Consequently, when you can imagine an answer to your research question, we recommend that you move onto the hypothesis formulation and testing path. Imagining an answer to your question means you can make plausible predictions. You can now begin clarifying the reasons for your predictions and transform your early predictions into hypotheses (predictions along with rationales). We recommend you do this as soon as you have guesses about the answers to your questions because formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses offers a tool that puts you squarely on the path of scientific inquiry. It is a tool that can guide you through the entire process of conducting a research study.

This does not mean you are finished asking questions. Predictions are often created as answers to questions. So, we encourage you to continue asking questions to clarify what you want to know. But your target shifts from only asking questions to also proposing predictions for the answers and developing reasons the answers will be accurate predictions. It is by predicting answers, and explaining why you made those predictions, that you become engaged in scientific inquiry.

Cycles of Refining Questions and Predicting Answers

An example might provide a sense of how this process plays out. Suppose you are reading about Vygotsky’s ( 1987 ) zone of proximal development (ZPD), and you realize this concept might help you understand why your high school students had trouble learning exponential functions. Maybe they were outside this zone when you tried to teach exponential functions. In order to recognize students who would benefit from instruction, you might ask, “How can I identify students who are within the ZPD around exponential functions?” What would you predict? Maybe students in this ZPD are those who already had knowledge of related functions. You could write out some reasons for this prediction, like “students who understand linear and quadratic functions are more likely to extend their knowledge to exponential functions.” But what kind of data would you need to test this? What would count as “understanding”? Are linear and quadratic the functions you should assess? Even if they are, how could you tell whether students who scored well on tests of linear and quadratic functions were within the ZPD of exponential functions? How, in the end, would you measure what it means to be in this ZPD? So, asking a series of reasonable questions raised some red flags about the way your initial question was phrased, and you decide to revise it.

You set the stage for revising your question by defining ZPD as the zone within which students can solve an exponential function problem by making only one additional conceptual connection between what they already know and exponential functions. Your revised question is, “Based on students’ knowledge of linear and quadratic functions, which students are within the ZPD of exponential functions?” This time you know what kind of data you need: the number of conceptual connections students need to bridge from their knowledge of related functions to exponential functions. How can you collect these data? Would you need to see into the minds of the students? Or, are there ways to test the number of conceptual connections someone makes to move from one topic to another? Do methods exist for gathering these data? You decide this is not realistic, so you now have a choice: revise the question further or move your research in a different direction.

Notice that we do not use the term research question for all these early versions of questions that begin clarifying for yourself what you want to study. These early versions are too vague and general to be called research questions. In this book, we save the term research question for a question that comes near the end of the work and captures exactly what you want to study . By the time you are ready to specify a research question, you will be thinking about your study in terms of hypotheses and tests. When your hypotheses are in final form and include clear predictions about what you will find, it will be easy to state the research questions that accompany your predictions.

To reiterate one of the key points of this chapter: hypotheses carry much more information than research questions. Using our definition, hypotheses include predictions about what the answer might be to the question plus reasons for why you think so. Unlike research questions, hypotheses capture all three images of scientific inquiry presented in Chap. 1 (planning, observing and explaining, and revising one’s thinking). Your hypotheses represent the most you know, at the moment, about your research topic. The same cannot be said for research questions.

Beginning with a Research Problem

When you wrote answers to the six questions at the end of Part I of this chapter, you might have identified a research interest by stating it as a problem. This is the third path you might take to begin your research. Perhaps your description of your problem might look something like this: “When I tried to teach my middle school students by presenting them with a challenging problem without showing them how to solve similar problems, they didn’t exert much effort trying to find a solution but instead waited for me to show them how to solve the problem.” You do not have a specific question in mind, and you do not have an idea for why the problem exists, so you do not have a prediction about how to solve it. Writing a statement of this problem as clearly as possible could be the first step in your research journey.

As you think more about this problem, it will feel natural to ask questions about it. For example, why did some students show more initiative than others? What could I have done to get them started? How could I have encouraged the students to keep trying without giving away the solution? You are now on the path of asking questions—not research questions yet, but questions that are helping you focus your interest.

As you continue to think about these questions, reflect on your own experience, and read what others know about this problem, you will likely develop some guesses about the answers to the questions. They might be somewhat vague answers, and you might not have lots of confidence they are correct, but they are guesses that you can turn into predictions. Now you are on the hypothesis-formulation-and-testing path. This means you are on the path of asking yourself why you believe the predictions are correct, developing rationales for the predictions, asking what kinds of empirical observations would test your predictions, and refining your rationales and predictions as you read the literature and talk with colleagues.

A simple diagram that summarizes the three paths we have described is shown in Fig. 2.1 . Each row of arrows represents one pathway for formulating an informed hypothesis. The dotted arrows in the first two rows represent parts of the pathways that a researcher may have implicitly travelled through already (without an intent to form a prediction) but that ultimately inform the researcher’s development of a question or prediction.

Part III. One Researcher’s Experience Launching a Scientific Inquiry

Martha was in her third year of her doctoral program and beginning to identify a topic for her dissertation. Based on (a) her experience as a high school mathematics teacher and a curriculum supervisor, (b) the reading she has done to this point, and (c) her conversations with her colleagues, she has developed an interest in what kinds of professional development experiences (let’s call them learning opportunities [LOs] for teachers) are most effective. Where does she go from here?

Exercise 2.2

Before you continue reading, please write down some suggestions for Martha about where she should start.

A natural thing for Martha to do at this point is to ask herself some additional questions, questions that specify further what she wants to learn: What kinds of LOs do most teachers experience? How do these experiences change teachers’ practices and beliefs? Are some LOs more effective than others? What makes them more effective?

To focus her questions and decide what she really wants to know, she continues reading but now targets her reading toward everything she can find that suggests possible answers to these questions. She also talks with her colleagues to get more ideas about possible answers to these or related questions. Over several weeks or months, she finds herself being drawn to questions about what makes LOs effective, especially for helping teachers teach more conceptually. She zeroes in on the question, “What makes LOs for teachers effective for improving their teaching for conceptual understanding?”

This question is more focused than her first questions, but it is still too general for Martha to define a research study. How does she know it is too general? She uses two criteria. First, she notices that the predictions she makes about the answers to the question are all over the place; they are not constrained by the reasons she has assembled for her predictions. One prediction is that LOs are more effective when they help teachers learn content. Martha makes this guess because previous research suggests that effective LOs for teachers include attention to content. But this rationale allows lots of different predictions. For example, LOs are more effective when they focus on the content teachers will teach; LOs are more effective when they focus on content beyond what teachers will teach so teachers see how their instruction fits with what their students will encounter later; and LOs are more effective when they are tailored to the level of content knowledge participants have when they begin the LOs. The rationale she can provide at this point does not point to a particular prediction.

A second measure Martha uses to decide her question is too general is that the predictions she can make regarding the answers seem very difficult to test. How could she test, for example, whether LOs should focus on content beyond what teachers will teach? What does “content beyond what teachers teach” mean? How could you tell whether teachers use their new knowledge of later content to inform their teaching?

Before anticipating what Martha’s next question might be, it is important to pause and recognize how predicting the answers to her questions moved Martha into a new phase in the research process. As she makes predictions, works out the reasons for them, and imagines how she might test them, she is immersed in scientific inquiry. This intellectual work is the main engine that drives the research process. Also notice that revisions in the questions asked, the predictions made, and the rationales built represent the updated thinking (Chap. 1 ) that occurs as Martha continues to define her study.

Based on all these considerations and her continued reading, Martha revises the question again. The question now reads, “Do LOs that engage middle school mathematics teachers in studying mathematics content help teachers teach this same content with more of a conceptual emphasis?” Although she feels like the question is more specific, she realizes that the answer to the question is either “yes” or “no.” This, by itself, is a red flag. Answers of “yes” or “no” would not contribute much to understanding the relationships between these LOs for teachers and changes in their teaching. Recall from Chap. 1 that understanding how things work, explaining why things work, is the goal of scientific inquiry.

Martha continues by trying to understand why she believes the answer is “yes.” When she tries to write out reasons for predicting “yes,” she realizes that her prediction depends on a variety of factors. If teachers already have deep knowledge of the content, the LOs might not affect them as much as other teachers. If the LOs do not help teachers develop their own conceptual understanding, they are not likely to change their teaching. By trying to build the rationale for her prediction—thus formulating a hypothesis—Martha realizes that the question still is not precise and clear enough.