Essay Papers Writing Online

Why the “freedom writers essay” is an inspiring tale of hope, empathy, and overcoming adversity.

Education has always been a paramount aspect of society, shaping individuals’ intellect and character. Within the vast realms of academia, written expressions have played a pivotal role in documenting and disseminating knowledge. Among these, the essays by Freedom Writers stand out as a testament to the importance of personal narratives and the transformative power they hold.

By delving into the multifaceted dimensions of human experiences, the essays penned by Freedom Writers captivate readers with their raw authenticity and emotional depth. These narratives showcase the indomitable spirit of individuals who have triumphed over adversity, providing invaluable insights into the human condition. Through their stories, we gain a profound understanding of the challenges faced by marginalized communities, shedding light on the systemic issues deeply ingrained in our society.

What makes the essays by Freedom Writers particularly significant is their ability to ignite a spark of empathy within readers. The vivid descriptions and heartfelt accounts shared in these personal narratives serve as a bridge, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and fostering a sense of understanding. As readers immerse themselves in these stories, they develop a heightened awareness of the struggles faced by others, ultimately cultivating a more inclusive and compassionate society.

The Inspiring Story of the Freedom Writers Essay

The Freedom Writers Essay tells a powerful and inspiring story of a group of students who were able to overcome adversity and find their own voices through the power of writing. This essay not only impacted the education system, but also touched the hearts of many individuals around the world.

Set in the early 1990s, the Freedom Writers Essay highlights the journey of a young teacher named Erin Gruwell and her diverse group of students in Long Beach, California. Faced with a challenging and often hostile environment, Gruwell used literature and writing as a platform to engage her students and help them express their own experiences and emotions.

Through the use of journals, the students were able to share their personal stories, struggles, and dreams. This essay not only became a therapeutic outlet for the students, but it also allowed them to see the power of their own voices. It gave them a sense of empowerment and hope that they could break free from the cycle of violence and poverty that surrounded them.

As their stories were shared through the Freedom Writers Essay, the impact reached far beyond the walls of their classroom. Their words resonated with people from all walks of life, who were able to see the universal themes of resilience, empathy, and the importance of education. The essay sparked a movement of hope and change, inspiring individuals and communities to work together towards a more inclusive and equitable education system.

The Freedom Writers Essay is a testament to the transformative power of education and the incredible potential of young minds. It serves as a reminder that everyone has a story to tell and that through the written word, we can create understanding, bridge divides, and inspire change.

In conclusion, the Freedom Writers Essay is not just a piece of writing, but a catalyst for change. It showcases the remarkable journey of a group of students who found solace and strength in their own stories. It reminds us of the importance of empowering young minds and providing them with the tools necessary to overcome obstacles and make a difference in the world.

Understanding the background and significance of the Freedom Writers essay

The Freedom Writers essay holds a notable history and plays a significant role in the field of education. This piece of writing carries a background rich with hardships, triumphs, and the power of individual expression.

Originating from the diary entries of a group of high school students known as the Freedom Writers, the essay documents their personal experiences, struggles, and remarkable growth. These students were part of a racially diverse and economically disadvantaged community, facing social issues including gang violence, racism, and poverty.

Despite the challenging circumstances, the Freedom Writers found solace and empowerment through writing. Their teacher, Erin Gruwell, recognized the potential of their stories and encouraged them to share their experiences through written form. She implemented a curriculum that encouraged self-expression, empathy, and critical thinking.

The significance of the Freedom Writers essay lies in its ability to shed light on the experiences of marginalized communities and bring attention to the importance of education as a means of empowerment. The essay serves as a powerful tool to inspire change, challenge social norms, and foster understanding among diverse populations.

By sharing their narratives, the students of the Freedom Writers not only found catharsis and personal growth, but also contributed to a larger discourse on the impact of education and the role of teachers in transforming lives. The essay serves as a reminder of the profound impact that storytelling and education can have on individuals and communities.

| Key Takeaways: |

|---|

| – The Freedom Writers essay originated from the diary entries of a group of high school students. |

| – The essay documents the students’ personal experiences, struggles, and growth. |

| – The significance of the essay lies in its ability to shed light on marginalized communities and emphasize the importance of education. |

| – The essay serves as a powerful tool to inspire change, challenge social norms, and foster understanding among diverse populations. |

| – The students’ narratives contribute to a larger discourse on the impact of education and the role of teachers in transforming lives. |

Learning from the Unique Teaching Methods in the Freedom Writers Essay

The Freedom Writers Essay presents a remarkable story of a teacher who uses unconventional teaching methods to make a positive impact on her students. By examining the strategies employed by the teacher in the essay, educators can learn valuable lessons that can enhance their own teaching practices. This section explores the unique teaching methods showcased in the Freedom Writers Essay and the potential benefits they can bring to the field of education.

Empowering student voice and promoting inclusivity: One of the key themes in the essay is the importance of giving students a platform to express their thoughts and experiences. The teacher in the Freedom Writers Essay encourages her students to share their stories through writing, empowering them to find their own voices and fostering a sense of inclusivity in the classroom. This approach teaches educators the significance of valuing and incorporating student perspectives, ultimately creating a more engaging and diverse learning environment.

Building relationships and trust: The teacher in the essay invests time and effort in building meaningful relationships with her students. Through personal connections, she is able to gain their trust and create a safe space for learning. This emphasis on building trust highlights the impact of positive teacher-student relationships on academic success. Educators can learn from this approach by understanding the importance of establishing a supportive and nurturing rapport with their students, which can enhance student engagement and motivation.

Using literature as a tool for empathy and understanding: The teacher in the Freedom Writers Essay introduces her students to literature that explores diverse perspectives and themes of resilience and social justice. By incorporating literature into her curriculum, she encourages her students to develop empathy and gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of others. This approach underscores the value of incorporating diverse and relevant texts into the classroom, enabling students to broaden their perspectives and foster critical thinking skills.

Fostering a sense of community and belonging: In the essay, the teacher creates a sense of community within her classroom by organizing activities that promote teamwork and collaboration. By fostering a supportive and inclusive learning environment, the teacher helps her students feel a sense of belonging and encourages them to support one another. This aspect of the teaching methods showcased in the Freedom Writers Essay reinforces the significance of collaborative learning and the sense of community in fostering academic growth and personal development.

Overall, the unique teaching methods presented in the Freedom Writers Essay serve as an inspiration for educators to think outside the box and explore innovative approaches to engage and empower their students. By incorporating elements such as student voice, building relationships, using literature for empathy, and fostering a sense of community, educators can create a transformative learning experience for their students, ultimately shaping them into critical thinkers and compassionate individuals.

Exploring the innovative approaches used by the Freedom Writers teacher

The Freedom Writers teacher employed a range of creative and groundbreaking methods to engage and educate their students, fostering a love for learning and empowering them to break the cycle of violence and poverty surrounding their lives. Through a combination of empathy, experiential learning, and personal storytelling, the teacher was able to connect with the students on a deep level and inspire them to overcome the obstacles they faced.

One of the innovative approaches utilized by the Freedom Writers teacher was the use of literature and writing as a means of communication and healing. By introducing the students to powerful works of literature that tackled relevant social issues, the teacher encouraged them to explore their own identities and experiences through writing. This not only facilitated self-expression but also fostered critical thinking and empathy, as the students were able to relate to the characters and themes in the literature.

The teacher also implemented a unique system of journal writing, where the students were given a safe and non-judgmental space to express their thoughts, emotions, and personal experiences. This practice not only helped the students develop their writing skills but also served as a therapeutic outlet, allowing them to process and reflect upon their own lives and the challenges they faced. By sharing and discussing their journal entries within the classroom, the students built a strong sense of community and support among themselves.

Another innovative strategy utilized by the Freedom Writers teacher was the integration of field trips and guest speakers into the curriculum. By exposing the students to different perspectives and experiences, the teacher broadened their horizons and challenged their preconceived notions. This experiential learning approach not only made the subjects more engaging and relatable but also encouraged the students to think critically and develop a greater understanding of the world around them.

In conclusion, the Freedom Writers teacher implemented a range of innovative and effective approaches to foster learning and personal growth among their students. Through the use of literature, writing, journaling, and experiential learning, the teacher created a supportive and empowering environment that allowed the students to overcome their adversities and become agents of change. These methods continue to inspire educators and highlight the importance of innovative teaching practices in creating a positive impact on students’ lives.

The Impact of the Freedom Writers Essay on Students’ Lives

The Freedom Writers Essay has had a profound impact on the lives of students who have been exposed to its powerful message. Through the personal stories and experiences shared in the essay, students are able to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and resilience that individuals can possess. The essay serves as a catalyst for personal growth, empathy, and a desire to make a positive difference in the world.

One of the key ways in which the Freedom Writers Essay impacts students’ lives is by breaking down barriers and promoting understanding. Through reading the essay, students are able to connect with the struggles and triumphs of individuals from diverse backgrounds. This fosters a sense of empathy and compassion, allowing students to see beyond their own experiences and appreciate the unique journeys of others.

In addition to promoting empathy, the Freedom Writers Essay also inspires students to take action. By showcasing the power of education and personal expression, the essay encourages students to use their voices to effect change in their communities. Students are empowered to stand up against injustice, advocate for those who are marginalized, and work towards creating a more inclusive and equitable society.

Furthermore, the essay serves as a reminder of the importance of perseverance in the face of adversity. Through the stories shared in the essay, students witness the determination and resilience of individuals who have overcome significant challenges. This inspires students to believe in their own ability to overcome obstacles and pursue their dreams, no matter the circumstances.

Overall, the impact of the Freedom Writers Essay on students’ lives is profound and far-reaching. It not only educates and enlightens, but also motivates and empowers. By exposing students to the power of storytelling and the potential for personal growth and social change, the essay equips them with the tools they need to become compassionate and engaged citizens of the world.

Examining the transformation experienced by the Freedom Writers students

The journey of the Freedom Writers students is a testament to the power of education and its transformative impact on young minds. Through their shared experiences, these students were able to overcome adversity, prejudice, and personal struggles to find their voices and take ownership of their education. This process of transformation not only shaped their individual lives but also had a ripple effect on their communities and the educational system as a whole.

| Before | After |

|---|---|

| The students entered the classroom with a sense of hopelessness and disillusionment, burdened by the weight of their personal challenges and the expectations society had placed on them. | Through the guidance of their dedicated teacher, Erin Gruwell, and the power of literature, the students discovered new perspectives, empathy, and the possibility of a brighter future. |

| They viewed their classmates as enemies, constantly at odds with one another due to racial and cultural differences. | By sharing their personal stories and embracing diversity, the students formed a strong bond, realizing that they were more similar than different and could support one another in their pursuit of education. |

| Academic success seemed out of reach, as they struggled with illiteracy, disengagement, and a lack of confidence in their abilities. | The students developed a renewed sense of purpose and belief in themselves. They discovered their passions, excelled academically, and gained the confidence to pursue higher education, despite the obstacles they faced. |

| They were trapped in a cycle of violence and negativity, influenced by the gang culture and societal pressures that surrounded them. | The students found a way out of the cycle, using the power of education to rise above their circumstances and break free from the limitations that had once defined them. |

| There was a lack of trust between the students and their teachers, as they felt unheard and misunderstood. | Through the creation of a safe and inclusive classroom environment, the students developed trust and respect for their teachers, realizing that they had allies in their educational journey. |

The transformation experienced by the Freedom Writers students serves as a powerful reminder of the potential within every student, regardless of their background or circumstances. It highlights the importance of creating an inclusive and supportive educational environment that encourages self-expression, empathy, and a belief in one’s own abilities. By fostering a love for learning and empowering students to embrace their unique voices, education can become a catalyst for positive change, both within individuals and society as a whole.

Addressing Social Issues and Promoting Empathy through the Freedom Writers Essay

In today’s society, it is important to address social issues and promote empathy to create a more inclusive and harmonious world. One way to achieve this is through the powerful medium of the written word. The Freedom Writers Essay, a notable piece of literature, serves as a catalyst for addressing social issues and promoting empathy among students.

The Freedom Writers Essay showcases the experiences and struggles of students who have faced adversity, discrimination, and inequality. Through their personal narratives, these students shed light on the social issues that exist within our society, such as racism, poverty, and violence. By sharing their stories, they invite readers to step into their shoes and gain a deeper understanding of the challenges they face. This promotes empathy and encourages readers to take action to create a more equitable world.

Furthermore, the Freedom Writers Essay fosters a sense of community and unity among students. As they read and discuss the essay, students have the opportunity to engage in meaningful conversations about social issues, sharing their own perspectives and experiences. This dialogue allows them to challenge their beliefs, develop critical thinking skills, and broaden their horizons. By creating a safe space for open and honest discussions, the Freedom Writers Essay creates an environment where students can learn from one another and grow together.

In addition, the essay prompts students to reflect on their own privileges and biases. Through self-reflection, students can gain a better understanding of their own place in society and the role they can play in creating positive change. This reflection process helps students develop empathy for others and encourages them to become active agents of social justice.

In conclusion, the Freedom Writers Essay serves as a powerful tool for addressing social issues and promoting empathy among students. By sharing personal narratives, fostering dialogue, and prompting self-reflection, this essay encourages students to confront societal challenges head-on and take meaningful action. Through the power of the written word, the essay helps create a more inclusive and empathetic society.

Analyzing how the essay tackles significant societal issues and promotes empathy

In this section, we will examine how the essay addresses crucial problems in society and encourages a sense of understanding. The essay serves as a platform to shed light on important social issues and foster empathy among its readers.

The essay delves into the depths of societal problems, exploring topics such as racial discrimination, stereotyping, and the achievement gap in education. It presents these issues in a thought-provoking manner, prompting readers to reflect on the harsh realities faced by marginalized communities. Through personal anecdotes and experiences, the essay unveils the profound impact of these problems on individuals and society as a whole.

Furthermore, the essay emphasizes the significance of cultural understanding and empathy. It highlights the power of perspective and the importance of recognizing and challenging one’s own biases. The author’s account of their own transformation and ability to connect with their students serves as an inspiring example, urging readers to step outside their comfort zones and embrace diversity.

By confronting and discussing these social issues head-on, the essay not only raises awareness but also calls for collective action. It encourages readers to become advocates for change and actively work towards creating a more inclusive and equitable society. The essay emphasizes the role of education in addressing these societal problems and the potential for growth and transformation it can bring.

In essence, the essay provides a platform to examine important societal problems and promotes empathy by humanizing the issues and encouraging readers to listen, understand, and work towards positive change.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

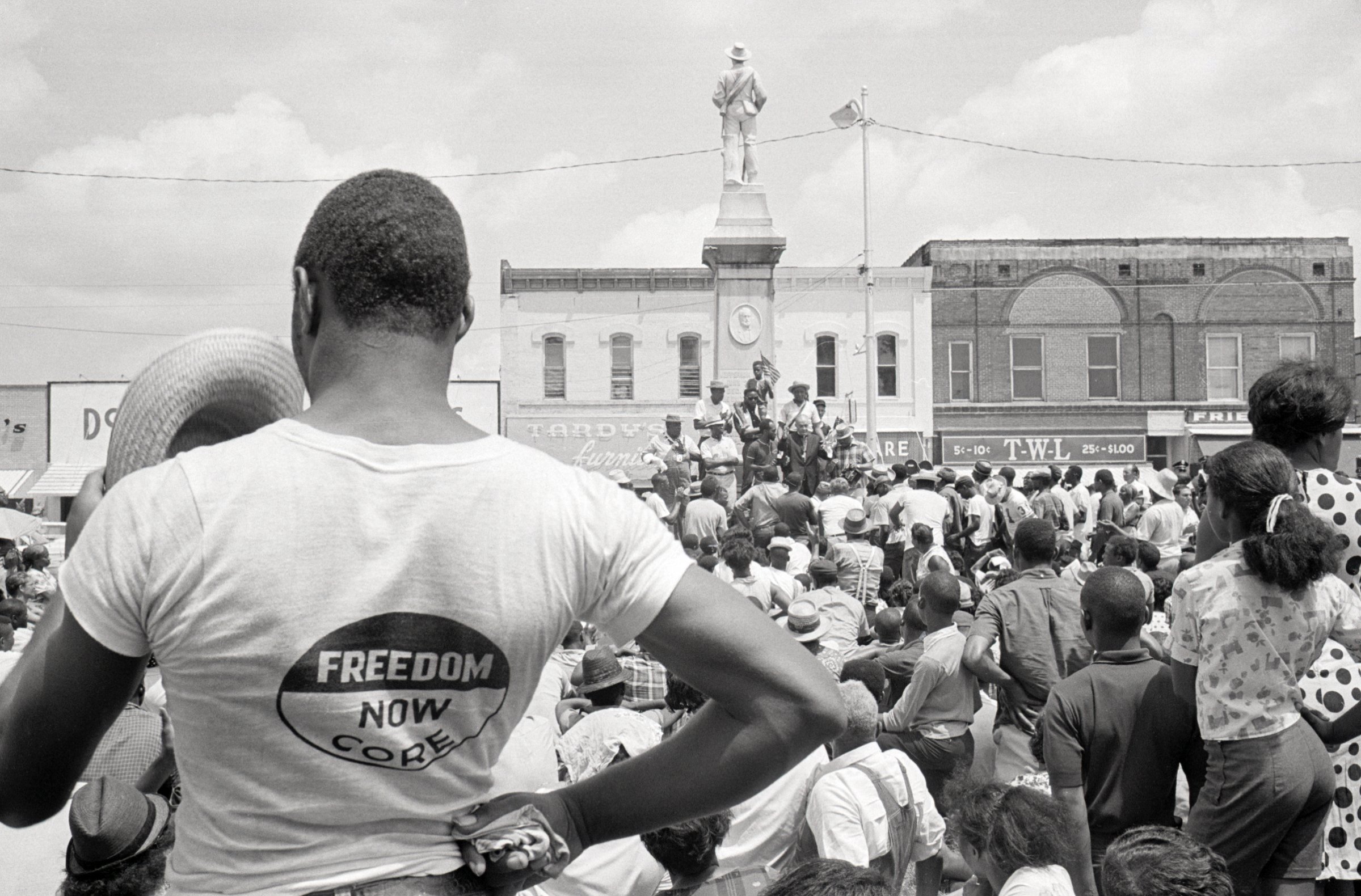

Essays About Freedom: 5 Helpful Examples and 7 Prompts

Freedom seems simple at first; however, it is quite a nuanced topic at a closer glance. If you are writing essays about freedom , read our guide of essay examples and writing prompts.

In a world where we constantly hear about violence, oppression, and war, few things are more important than freedom . It is the ability to act, speak, or think what we want without being controlled or subjected. It can be considered the gateway to achieving our goals , as we can take the necessary steps.

However, freedom is not always “doing whatever we want.” True freedom means to do what is righteous and reasonable, even if there is the option to do otherwise. Moreover, freedom must come with responsibility ; this is why laws are in place to keep society orderly but not too micro-managed, to an extent.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Examples of Essays About Freedom

1. essay on “freedom” by pragati ghosh, 2. acceptance is freedom by edmund perry, 3. reflecting on the meaning of freedom by marquita herald.

- 4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

5. What are freedom and liberty? by Yasmin Youssef

1. what is freedom, 2. freedom in the contemporary world, 3. is freedom “not free”, 4. moral and ethical issues concerning freedom, 5. freedom vs. security, 6. free speech and hate speech, 7. an experience of freedom.

“Freedom is non denial of our basic rights as humans. Some freedom is specific to the age group that we fall into. A child is free to be loved and cared by parents and other members of family and play around. So this nurturing may be the idea of freedom to a child. Living in a crime free society in safe surroundings may mean freedom to a bit grown up child.”

In her essay, Ghosh briefly describes what freedom means to her. It is the ability to live your life doing what you want. However, she writes that we must keep in mind the dignity and freedom of others. One cannot simply kill and steal from people in the name of freedom ; it is not absolute. She also notes that different cultures and age groups have different notions of freedom . Freedom is a beautiful thing, but it must be exercised in moderation.

“They demonstrate that true freedom is about being accepted, through the scenarios that Ambrose Flack has written for them to endure. In The Strangers That Came to Town, the Duvitches become truly free at the finale of the story. In our own lives, we must ask: what can we do to help others become truly free?”

Perry’s essay discusses freedom in the context of Ambrose Flack’s short story The Strangers That Came to Town : acceptance is the key to being free. When the immigrant Duvitch family moved into a new town, they were not accepted by the community and were deprived of the freedom to live without shame and ridicule. However, when some townspeople reach out, the Duvitches feel empowered and relieved and are no longer afraid to go out and be themselves.

“Freedom is many things, but those issues that are often in the forefront of conversations these days include the freedom to choose, to be who you truly are, to express yourself and to live your life as you desire so long as you do not hurt or restrict the personal freedom of others. I’ve compiled a collection of powerful quotations on the meaning of freedom to share with you, and if there is a single unifying theme it is that we must remember at all times that, regardless of where you live, freedom is not carved in stone, nor does it come without a price.”

In her short essay, Herald contemplates on freedom and what it truly means. She embraces her freedom and uses it to live her life to the fullest and to teach those around her. She values freedom and closes her essay with a list of quotations on the meaning of freedom , all with something in common: freedom has a price. With our freedom , we must be responsible . You might also be interested in these essays about consumerism .

4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

“Freedom demands of one, or rather obligates one to concern ourselves with the affairs of the world around us. If you look at the world around a human being, countries where freedom is lacking, the overall population is less concerned with their fellow man, then in a freer society . The same can be said of individuals, the more freedom a human being has, and the more responsible one acts to other, on the whole.”

Carlson writes about freedom from a more religious perspective, saying that it is a right given to us by God. However, authentic freedom is doing what is right and what will help others rather than simply doing what one wants. If freedom were exercised with “doing what we want” in mind, the world would be disorderly. True freedom requires us to care for others and work together to better society .

“In my opinion, the concepts of freedom and liberty are what makes us moral human beings. They include individual capacities to think, reason, choose and value different situations. It also means taking individual responsibility for ourselves, our decisions and actions. It includes self-governance and self-determination in combination with critical thinking, respect, transparency and tolerance. We should let no stone unturned in the attempt to reach a state of full freedom and liberty, even if it seems unrealistic and utopic.”

Youssef’s essay describes the concepts of freedom and liberty and how they allow us to do what we want without harming others. She notes that respect for others does not always mean agreeing with them. We can disagree, but we should not use our freedom to infringe on that of the people around us. To her, freedom allows us to choose what is good, think critically, and innovate.

7 Prompts for Essays About Freedom

Freedom is quite a broad topic and can mean different things to different people. For your essay, define freedom and explain what it means to you. For example, freedom could mean having the right to vote, the right to work, or the right to choose your path in life. Then, discuss how you exercise your freedom based on these definitions and views.

The world as we know it is constantly changing, and so is the entire concept of freedom . Research the state of freedom in the world today and center your essay on the topic of modern freedom . For example, discuss freedom while still needing to work to pay bills and ask, “Can we truly be free when we cannot choose with the constraints of social norms?” You may compare your situation to the state of freedom in other countries and in the past if you wish.

A common saying goes like this: “Freedom is not free.” Reflect on this quote and write your essay about what it means to you: how do you understand it? In addition, explain whether you believe it to be true or not, depending on your interpretation.

Many contemporary issues exemplify both the pros and cons of freedom ; for example, slavery shows the worst when freedom is taken away, while gun violence exposes the disadvantages of too much freedom . First, discuss one issue regarding freedom and briefly touch on its causes and effects. Then, be sure to explain how it relates to freedom .

Some believe that more laws curtail the right to freedom and liberty. In contrast, others believe that freedom and regulation can coexist, saying that freedom must come with the responsibility to ensure a safe and orderly society . Take a stand on this issue and argue for your position, supporting your response with adequate details and credible sources.

Many people, especially online, have used their freedom of speech to attack others based on race and gender, among other things. Many argue that hate speech is still free and should be protected, while others want it regulated. Is it infringing on freedom ? You decide and be sure to support your answer adequately. Include a rebuttal of the opposing viewpoint for a more credible argumentative essay.

For your essay, you can also reflect on a time you felt free. It could be your first time going out alone, moving into a new house, or even going to another country. How did it make you feel? Reflect on your feelings, particularly your sense of freedom , and explain them in detail.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

The Freedom to Write

This week’s writing prompt.

Every Fourth of July, we celebrate the birth of our country and all of its accompanying freedoms. We have many ways to experience and exercise our freedom. Writing is one.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Jane Smiley, author of Some Luck , shared her reaction to a note in a friend’s office one day:

“Over her desk, above her typewriter, she’d tacked up a phrase: ‘NOBODY ASKED YOU TO WRITE THAT NOVEL.’

The line reminded me that writing is a voluntary activity. I could always stop. I could always go on. And since no one’s asking me to do it, I’ve always seen writing as an exercise of freedom, rather than an exercise of obligation. Yes, writing is my job—but I could always stop and do something else. Once writing becomes an exercise of freedom, it’s filled with energy.” [1]

Not only do we enjoy freedom of speech in our great country, but we also have the freedom to express ourselves creatively. As Smiley says, we are free to write, or not. No one makes us write.

- What do you think about Smiley’s perception of the freedom to write?

- Do you agree with her? Why or why not?

- Describe the freedom that writing provides you.

- Do you view writing as a get to or a have to activity?

- Has writing been instrumental in liberating you in an area of your personal life?

It’s a brand new month, and all posts in response to our writing prompts in July are entered into our drawing to win a free online coaching video—that’s a $20 value! Go for it!

[1] Fassler, Joe. “’Writing Is an Exercise in Freedom’: How Pulitzer Winner Jane Smiley Motivates Herself.” The Atlantic , Atlantic Media Company, 3 Dec. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/10/ideas-motivate-great-writing/381224/. Accessed July 1, 2019.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

By using this form you agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. *

You May Also Like

The Days We Can’t Forget

Our Beloved Toys

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Freedom to Write Index 2021

Credit AP Photo

Introduction

On February 1, 2021, a military coup violently disrupted Myanmar’s fragile and uncertain experiment with civilian rule. Writers and filmmakers were among those immediately imprisoned. Protesters and poets were soon shot in the streets. As this report goes to press, the world’s eyes are on Russia’s brutal, devastating assault on Ukraine—its people, language and culture, and democracy. Putin’s unbridled aggression, however, is part of a larger resurgence of authoritarianism around the globe.

The past year has repeatedly seen authoritarian forces seek to reclaim powers and territories that had previously passed outside their control; the echoes of the past are heard not only in Europe, but in Myanmar, where the military’s naked attempt to retrieve its lost power brought shock, horror, and then resistance; and in Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s swift recapture of the country following U.S. military withdrawal seemed to—almost overnight—decimate the progress Afghans had painstakingly made over the last 20 years and are struggling to uphold, including with regard to women’s rights, freedom of expression, cultural and artistic creativity, and the development of independent media. From Tunisia to Sudan to Nicaragua, old forces re-exerted themselves and moved to quash democratic progress. And in Hong Kong, a city with a robust history of vibrant freedoms, the reach of the Chinese government has been extended, most formally in the application of the National Security Law against writers and independent media. This has not only led to a crackdown, but also created a climate of looming fear and a sense that safety may only lie in silence, or exile. In Russia, a concerted effort to eliminate what remained of independent media and the space for dissent over recent years laid the groundwork for Putin to maintain total information control in wartime.

In democracies as well, authoritarian tactics are being employed. Censorship and intimidation of dissenting voices is rife in India. In the United States, efforts to ban books and enact laws that would bar discussion of certain topics in classrooms spiked in 2021. Much of this debate centered around the freedom to contend with and openly debate the complexities of history. This, too, has echoes around the globe. Just before Russian troops began this latest incursion into Ukraine, Putin gave a speech in which he attempted to rewrite Ukraine’s history to suit his own ends. For years now, Putin has held in prison the historian Yury Dmitriev on specious charges of child pornography; Dmitriev’s true crime was uncovering and documenting mass graves from the Stalinist era, a historical truth that contradicted Putin’s attempts to whitewash and glorify the memory of Stalin. Government attempts to silence those who study, document, and debate history are typically also an attempt to exert a sole narrative over the past, one that serves the interests of the present.

Yet in all of these cases, authoritarian regimes have been met with resistance. In Myanmar, widespread and sustained civil disobedience—including the creative resistance of writers and artists—followed the coup. Afghan women refused to be silenced and they, too, have taken to the streets. Belarusians have continued their resistance against a president holding onto power despite an election he seemed to think he could steal without a fight. And today, Putin must contend not only with the fierce resistance of the Ukrainian people, but also Russians inside the country and around the world who persist in speaking the truth.

As truth-tellers, creative visionaries, and documentarians, writers have been at the forefront of these movements to resist authoritarianism, and they have been targeted as a result. The Iranian Writers’ Association has become a prime target of its government for its persistence in celebrating literature, condemning censorship, and commemorating past attempts to silence Iranian writers. PEN America’s sister organization PEN Belarus, despite being formally dissolved by a Belarusian court in August 2021, perseveres in documenting its government’s assaults on writers, artists, and all those who insist on their right to speak freely. 1 PEN America, “Court Formally Dissolves PEN Belarus,” press release, August 9, 2021, pen.org/press-release/court-formally-dissolves-pen-belarus/ Myanmar’s creative community has braved brutal violence and used their writing and artwork to resist the coup and represent the public’s demands for freedom. 2 “Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup,” PEN America, December 16, 2021, pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup/ Cuban artists and writers have persisted, despite repeated arrests, in critiquing their government and calling for change.

In these countries and others, and as PEN America’s Freedom to Write Index documents, writers and public intellectuals have been unjustly locked up for their exercise of free expression; dozens are currently serving sentences of 10 years or more for their words. In countries notorious for poor prison conditions, the mistreatment of political prisoners through solitary confinement or torture has been compounded by the grave threats to their health posed by COVID-19 and its spread inside jails. But governments’ attempts to muzzle dissent have failed to extinguish individual writers’ voices. In the face of repression, literary communities have come together in defense of writers under threat; writers in prison have gone on hunger strikes—not to call for their own release, but on behalf of others unjustly jailed. Translators have made threatened writers’ words available to a global audience. And across the world, advocates and allies have read aloud the words of those whose governments would see them silenced, and shared the work of those whose governments would see it destroyed. And that work has offered hope to all who seek to push back against the forces of repression.

In the face of an authoritarian resurgence, writers are at the forefront of the defense of free expression and also have an essential role to play, pushing back against attempts to control the narrative; sustaining cultures and languages under threat; holding governments to account—on issues as varied as corruption, their response to COVID-19, or upholding basic rights; and envisioning new possibilities for the future. The freedom to write guarantees our collective ability to imagine and to inspire, and it demands our defense.

The Global Picture

During 2021, according to data collected for the Freedom to Write Index, at least 277 writers , academics, and public intellectuals in 36 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were unjustly held in detention or imprisoned in connection with their writing, their work, or related advocacy. This number is slightly higher than the 273 individuals counted in the 2020 Freedom to Write Index, and significantly higher than the total in 2019 (238). By far the most significant increase was seen in Myanmar , as a result of the crackdown that followed the military coup there on February 1, 2021, which has included the deliberate targeting of writers and the broader creative community. The numbers of those detained in Saudi Arabia , Turkey , and Belarus dropped from 2020, although many of those released from prison in Saudi Arabia continue to face draconian, unjust conditions on their release, including constraints on their freedom of movement and expression. In Belarus, the sharp uptick in detentions—many of them short-term—that accompanied the protests after the stolen election of August 2020 dropped off, though 2021 increasingly saw targeted arrests of writers and others who continued to speak out, and longer-term detentions.

Writers Imprisoned Globally: 2021

A worsening and in some cases violent closure of civil society in many countries led to a reshuffling of the world’s top jailers of writers and public intellectuals. Two countries, however, remained stable in their notoriously high rankings: China and Saudi Arabia remained the first and second-worst jailers of writers, with 85 and 29 writers detained, respectively. Myanmar escalated to the third-worst jailer of writers and public intellectuals, with 20 individuals newly detained in 2021 and 26 total behind bars; Myanmar was jointly ranked ninth last year with 8 detentions. These three countries alone accounted for half of all cases, just over 50 percent of the total. Myanmar catapulted into third place due to a widespread crackdown on civil society and free expression in the wake of the February 2021 coup, in which the military seized power and prevented the elected parliament from forming a new government. Many writers, creative artists, and influential cultural figures were targeted during the first hours of the coup; over the course of 2021, at least 26 detentions of writers and intellectuals were documented.

In Iran , a significant uptick was also documented: at least 21 writers were in prison or detention during the year, remaining the fourth-worst jailer of writers around the world as documented in 2020. While some writers counted in Iran in the 2020 Index have been released, at least 8 writers were newly jailed during 2021. Rounding out the top five with 18 writers held in detention—compared to 25 last year—is Turkey , where a decline was documented due to the welcome release of writers; some had been detained for more than four years. Other prevalent threats against writers in Turkey such as physical attacks and protracted legal trials, even against writers in exile, were documented throughout 2021, though not captured in this figure.

As has been documented previously in the Freedom to Write Index, the overwhelming majority of writers and public intellectuals held behind bars during 2021 are men. This disparity has widened: women comprise 12 percent of the 2021 Index count, as compared to 16 percent in 2019. Countries that have detained the highest number of women writers and public intellectuals track closely with those who have jailed the highest total number of writers. Collectively, authorities in China, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey—the top five countries that jailed the most writers during 2021—accounted for 27 of the 33 women writers in the 2021 Index. The remaining six women writers were jailed in Egypt, Belarus, India, and Vietnam, all countries ranking in the top 10 worst jailers of writers.

While many writers included in the Index hold multiple professional designations and are, for example, both literary writers and poets, the most prevalent professions of those incarcerated in 2021 were literary writers (111), scholars (59), poets (68), singer/songwriters (27), publishers (12), editors (9), translators (8), and dramatists (4). Notably, the number of poets jailed during 2021 increased compared to the 57 jailed during 2020, likely reflecting the bold stance many poets have taken on sensitive political and social themes, as well as the key role they have played in pushing back against authoritarianism in countries like Myanmar. Of the 277 individuals counted in this year’s Index, 4 died while in custody and 197—nearly three-quarters—remain in state custody at the time of this report’s publication. By holding these individuals behind bars, their governments are depriving them of their individual right to free speech, while also robbing the broader public of access to their innovative and influential voices of dissent, criticism, creativity, and conscience.

The majority of the writers and intellectuals included in the 2021 count were initially imprisoned or detained prior to 2021, or had faced previous detention or imprisonment. Of the 277 in prison or detention during 2021, roughly 72 percent had also spent multiple days behind bars in 2020. A smaller but significant subset of these writers, roughly 53 percent, were counted in the 2019 and 2020 Indexes as well. In addition to long-term imprisonments, this percentage includes cases of writers who have been repeatedly detained and released over the course of the past three years, indicating the continued pressure and repression many writers face. This year’s count of 277 also includes 15 cases of individuals who were detained or imprisoned prior to 2021 but whose status, or further information about their case and writing only became publicly known during the past year. Such cases are common, especially in environments where there is little transparency to the judicial process, extensive surveillance and self-censorship, and extremely limited access to information or media freedom; for example, China, including Tibet and Xinjiang, accounts for 7 of these 15 cases. In many such cases, detention is not confirmed until formal charges are brought. The 2021 Index includes 60 writers and intellectuals, in 20 different countries and territories, who were newly detained or imprisoned in 2021—a decline in new detentions and imprisonments in comparison to 2020.

Regarding the types of legal charges brought against jailed writers, many of the trends documented in the 2019 and 2020 Freedom to Write Indexes persisted in 2021. Threat to national security remains the primary category of legal charges that authorities around the world use to justify jailing writers and public intellectuals: at least 55 percent of detentions are based on allegations that writers have undermined national security. Examples of these charges include “membership in a banned group,” which are in some cases levied against writers for belonging to writers’ associations or cultural organizations; and “conspiracy to seize” or “subversion of” state power, often levied against writers who analyze politics, participate in public discourse, or write critically about government affairs. Other less widespread but frequent charges wielded against writers and public intellectuals include illegal assembly and organizing; retaliatory criminal charges such as tax crimes, fraud, and “resistance”; and criminal insult or defamation laws.

Situations in which charges are undisclosed or have yet to be brought against a writer—otherwise known as arbitrary detentions—made up at least 22 percent of the cases in this year’s Index. Arbitrary detentions represent a total lack of due process and deny writers and public intellectuals any recourse to challenge the claims against them; in some cases, they can last for decades. All eight of the cases counted in Eritrea are considered arbitrary, as few details have been disclosed in these cases, and the writers have been held incommunicado, several of them since 2001. Cases of arbitrary detention are also particularly common in Saudi Arabia, where at least 66 percent of the writers and public intellectuals jailed in 2021 were held for no stated reason. This staggering fraction is identical to the percentage documented in 2020, indicating that the prevalence of arbitrary detention has seen no change over the past year. Roughly 53 percent of the writers and public intellectuals in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China have been detained or imprisoned without legal justification. In contrast, China—when excluding autonomous and special administrative regions—has only one case of arbitrary detention: poet Cui Haoxin , also known as An Ran.

Several places where free expression was severely under threat in 2021 nonetheless do not make a significant appearance in the Index. The return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan has had a devastating impact on freedom of expression and placed writers, artists, and public intellectuals—especially women and members of ethnic and religious minority groups—in grave danger, yet few detentions have been recorded in the initial months following their takeover. The introduction of the oppressive National Security Law in Hong Kong in 2020 has seemingly only led to a handful of new cases of writers behind bars, and despite the further crackdown on free expression in Russia, it does not appear among the countries most responsible for detaining writers and intellectuals. This illustrates that while these numbers are an important indicator of the gravity of threats writers and intellectuals face for exercising their freedom of expression, they tell only part of the story of how free expression may be chilled.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has not, by and large, led to the more dramatic society-wide crackdowns on free expression that initially seemed possible, it has nonetheless had an insidious effect on writers and public intellectuals around the world, with the introduction of new “fake news” laws targeting dissent, new and subtle forms of surveillance, reduced opportunities for global connection and income, and the erosion of support systems that individuals under threat rely on to continue their work. It has also continued to vastly increase the health risks for writers behind bars. As the difference in the pandemic’s trajectory across countries becomes more stark, it is essential for advocates to keep top of mind the impact it continues to have on writers under threat, and especially those from already vulnerable communities.

Regional Breakdown

Governments in the Asia-Pacific region continued to jail the most writers and intellectuals for their writing or expression, with their share of the global total increasing in 2021, largely due to the crackdown in Myanmar. In total, 137—or nearly half of the global count—were jailed in countries in the Asia-Pacific, with the vast majority of those, 85, held in China. Following the February 2021 coup, Myanmar catapulted up to second in the region, with 26 held, while significant numbers continued to be jailed in Vietnam (10) and India (8). Countries in the Middle East and North Africa have also jailed significant numbers of writers and intellectuals, most notably Saudi Arabia (29), Iran (21), and Egypt (14). Countries in this region made up nearly 30 percent of the global count of imprisoned and detained writers, at least 82 individuals, in 2021.

Detentions and imprisonments of writers and intellectuals in Europe and Central Asia —accounting for 14 percent of the global total—occurred largely in two countries: Turkey and Belarus. Turkey moved to the fifth-place position, having held 18 of the 39 prisoners and detainees in Europe and Central Asia during 2021. The ongoing crackdown against those who have vocally opposed Belarus’s stolen 2020 presidential election continued to result in arrests and detentions in 2021, placing Belarus in seventh place worldwide, with 10 writers counted in the Index. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa contributed to roughly 4 percent of the 2021 Index, with 11 writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned. The vast majority of those were in Eritrea, which placed 10th with 8 writers behind bars. In the Americas , only Nicaragua and Cuba are represented, making up 3 percent of the 2021 Index total. Detentions of writers and public intellectuals in Cuba account for 7 of the 8 writers detained or imprisoned.

Top 10 Countries of Concern

China continued to top the list of countries detaining writers and intellectuals, with 85 detained or imprisoned in 2021, far more than any other country. Following China, the other top jailers of writers and intellectuals were Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, and Iran, each of which engaged in a concentrated targeting of dissenting voices in 2021 and held 20 or more writers behind bars. Saudi Arabia’s overall numbers decreased slightly from 2020 due to significant numbers of political prisoners being conditionally released during 2021, as did overall numbers in Turkey, where a handful of writers were additionally released upon completion of their years-long sentences. There was a considerable jump in detentions in Myanmar in the wake of the February 2021 coup, after which writers and creative artists were targeted for arrest alongside politicians and other influential figures. A smaller increase was apparent in Iran due to an ongoing crackdown against dissenting voices in which a number of writers were newly detained or summoned to serve previously imposed sentences in 2021.

During 2021, China remained stable in its position as the top jailer of writers and public intellectuals in the world. The total number of writers and public intellectuals in China, which includes the Xinjiang and Tibetan Autonomous Regions and Hong Kong, increased slightly from 81 to 85. The vast majority of these 85 writers have been in prison for at least several years, with 53 of them having been counted in both the 2019 and 2020 Freedom to Write Index reports as well. The myriad reasons that the authorities jail writers in China vary; writers whose words question prevailing public opinions or challenge the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) narratives are especially at risk of detention and imprisonment. And the Chinese government’s response to writers and public intellectuals exercising their universal rights to free expression is swift and wide-ranging.

Within China (excluding Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Inner Mongolia 3 The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region has been included in previous publications of the Freedom to Write Index, but PEN America did not identify cases of detained or imprisoned writers or public intellectuals in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region during 2021 according to our methodology. ), PEN America places the number of imprisoned writers or public intellectuals at 38. This number includes many writers and dissidents who have criticized government policy or the CCP’s leadership. The initial rationales for detaining these writers are often unstated or unclear, demonstrating the outsized scope of writing, speech, and other forms of expression that can be potentially considered “criminal.” Detained dissident writer Guo Quan ’s trial for criticizing the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic online began in September 2021. According to Guo’s lawyer, the prosecution cited almost 20 articles Guo wrote in its case against him for “inciting subversion of state power.” His articles criticized the CCP’s response to the pandemic, but his writings about social injustice and government corruption were also cited as evidence. 4 Debi Edward, “The missing number behind China’s coronavirus crisis,” ITV News, February 21, 2020, itv.com/news/2020-02-21/the-missing-number-behind-china-s-coronavirus-crisis ; Xue Xiaoshan, “Veteran Chinese Democracy Activist Stands Trial For ‘Subversion’ Over Articles,” Radio Free Asia, September 10, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/china/trial-09102021103820.html In 2020, Xu Zhiyong , an essayist, legal scholar, and critic of President Xi’s policies, was initially detained on the same charge; but during January 2021, authorities escalated the charges from “inciting subversion” to “subversion,” increasing his potential sentence to life in prison. 5 PEN America, “Reports: China to Escalate Charges Against PEN America Honoree Xu Zhiyong,” press release, January 22, 2021, pen.org/press-release/reports-china-to-escalate-charges-against-pen-america-honoree-xu-zhiyong/ Artist, activist, and online writer Chen Yunfei was detained on March 25, 2021, on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” after he published his thoughts on China’s nine-year compulsory education law based on his visits to schools in the Sichuan province. In contrast with President Xi’s declared emphasis on “rule of law,” the law against “picking quarrels” has been used by authorities as a catch-all criminal provision that is unclear, broad, and confusingly applied. 6 Guo Rui, ‘Picking quarrels and provoking trouble’: how China’s catch-all crime muzzles dissent,” South China Morning Post, August 25, 2021, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3146188/picking-quarrels-and-provoking-trouble-how-chinas-catch-all In December 2021, Chen was ultimately convicted of a different crime—he was sentenced to four years in prison for a retaliatory charge of “child molestation.” Chen vehemently rejects the charge as intended to discredit his work and slander his reputation. 7 Sun Chen, “Court in China’s Chengdu jails veteran rights activist on ‘trumped-up charge’,” Radio Free Asia, December 6, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/china/charge-12062021141519.html

In some cases, a writer’s mere public stature and past history as a person critical of the government is reason enough for Chinese authorities to jail them. In May 2021, writer and former Guizhou University economics professor Yang Shaozheng went missing. Though no reason has yet been disclosed for his arrest, Yang had been dismissed from Guizhou University in 2018 for writing two articles that questioned the CCP; specifically, the monetary costs of the party’s millions of official personnel. 8 Editorial Board, “Opinion: A professor dared tell the truth in China—and was fired,” The Washington Post , August 23, 2018, washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-professor-dared-tell-the-truth-in-china–and-was-fired/2018/08/23/9fd81eee-a653-11e8-a656-943eefab5daf_story.html In June 2021, Yang was charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and placed under residential surveillance in a designated location (RSDL), 9 “Locked Up: Inside China’s Secret RSDL Jails,” Safeguard Defenders, October 5, 2021, safeguarddefenders.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Locked%20Up%20%28High%20Res%20version%29.pdf a form of extrajudicial detention. At the end of 2021, he was formally arrested and reported to be held at a detention facility in Guiyang City. 10 “前贵州大学教授杨绍政被正式批捕 (Yang Shaozheng, former professor of Guizhou University and critic of government policies, is formally arrested),” Radio Free Asia , November 11, 2021, rfa.org/mandarin/Xinwen/6-11112021115902.html Outspoken poet Zhang Guiqi , also known as Lu Yang, was arrested on the same charge for undisclosed reasons. He was detained throughout 2021 in Shandong, after a secret trial in September 2020 in which no sentence was announced. 11 “256. Zhang Guiqi,” Independent Chinese PEN Center, accessed February 24, 2022, chinesepen.org/english/256-zhang-guiqi Experts suspect his detention is related to a video in which he called on President Xi to resign, but reiterate that the lack of legal transparency makes the exact reason difficult to discern. 12 “Police in China’s Shandong Detain Outspoken Poet For ‘Subversion’,” Radio Free Asia , May 14, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/china/poet-detained-05142020134933.html Hui Muslim poet Cui Haoxin , also known by his pen name An Ran, was arbitrarily detained in early January 2020 and has not been heard from since. Cui used online platforms and poetry to write about and protest the Chinese government’s mistreatment of Muslim minorities, including the mass detentions of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. 13 “China Detains Hui Muslim Poet Who Spoke Out Against Xinjiang Camps,” Radio Free Asia , January 27, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/china/poet-01272020163336.html ; Associated Press, “Chinese Muslim poet Cui Haoxin fears his people will suffer as history repeats itself in wave of religious repression,” South China Morning Post, December 28, 2018, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/2179831/chinese-muslim-poet-fears-his-people-will-suffer-history-repeats Employing arbitrary detention and vague charges—many of which international jurists have decried as in contravention with rights to free expression and due process—Chinese authorities continue to demonstrate their sweeping ability to jail writers and public intellectuals.

After being detained even once, writers can face intensified surveillance and restrictions on their travel and must essentially continue to live with targets on their backs, under constant threat of being captured again. Writer and democracy activist Yang Maodong , also known by his pen name Guo Feixiong, was detained at Pudong International Airport in Shanghai in late January 2021, when he tried to visit his ailing wife in the United States. 14 Chris Buckley, “A Chinese Dissident Tried to Fly to His Sick Wife in the U.S. Then He Vanished,” The New York Times , February 2, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/02/02/world/asia/china-dissident-yang-maodong.html Authorities in Guangzhou had confiscated Yang’s passport after his 2019 release from a politically motivated prison sentence. The day before he planned to fly, Yang had written an open letter to President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, urging them to allow him to travel on humanitarian grounds. Instead, authorities forcibly disappeared him; a year later—and two days after his wife’s death—Yang was formally arrested for “inciting subversion of state power.” 15 Helen Davidson, “Chinese activist told he could not visit dying wife is re-arrested,” The Guardian , January 18, 2022, theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/18/chinese-activist-yang-maodong-told-he-could-not-visit-dying-wife-is-re-arrested Writer and #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin , who previously served four months in detention for her public support of sexual assault victims, was also forcibly disappeared while trying to leave China, en route to study at the University of Sussex in England in September 2021. Despite returning Huang’s passport earlier in 2021 and continuing to surveil her for a year after her release, Chinese authorities secretly detained Huang in RSDL and later transferred her to a Guangzhou detention facility for “inciting subversion of state power. 16 Alice Su, “They helped Chinese women, workers, the forgotten and dying. Then they disappeared,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2021, latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-12-01/china-disappearances-gender-labor-class The trial of writer and poet Xie Fengxia , for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” began in April 2021. Just two years prior, Xie was released from prison; but he was surveilled, followed by local authorities, and “invited” for questioning at police stations following his release. After posting a poem commemorating Lin Zhao, a dissident of the Cultural Revolution, he was promptly detained again. 17 “185. Xie Fengxia,” Independent Chinese PEN Center, accessed February 24, 2022, chinesepen.org/english/185-xie-fengxia

In Hong Kong , several writers were newly detained in 2021, raising the number of writers and public intellectuals jailed from last year’s three to five. The crackdown under the draconian National Security Law borrows a tactic from Beijing’s repression of free expression, resting on ambiguously defined national security crimes. 18 Javier C. Hernández, “Harsh Penalties, Vaguely Defined Crimes: Hong Kong’s Security Law Explained,” June 30, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/30/world/asia/hong-kong-security-law-explain.html Under the law’s provisions, Hong Kong authorities have detained columnists, academics, and public intellectuals who have written in support of pro-democracy protests, and levied heavy penalties against the institutions that stand by them. A number of individuals who were prominent in the 2014 Occupy Central Movement in Hong Kong were also re-detained or newly charged under the repressive provisions of the National Security Law. Legal scholar and influential pro-democracy writer Benny Tai Yiu-ting was re-detained after a revocation of his bail stemming from a 2019 politically motivated detention. 19 Jasmine Siu, “Benny Tai sent back to jail to await Hong Kong court’s ruling in Occupy Central appeal,” South China Morning Post , March 4, 2021, sg.news.yahoo.com/benny-tai-sent-back-jail-095645191.html Social media activist and writer Joshua Wong , who rose to prominence as a youth activist when he was first charged in 2015, faced a slew of new charges brought against him during the year under the National Security Law, in addition to past charges that kept him imprisoned throughout the year. 20 Reuters, “Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong jailed an additional 10 months over June 4 assembly,” CNBC, May 6, 2021, cnbc.com/2021/05/06/hong-kong-activist-joshua-wong-jailed-an-additional-10-months-over-june-4-assembly.html

The highly publicized closure of pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily served as a bellwether of media censorship and arrests of writers. On June 17, 2021, 500 police officers raided the newspaper’s office, seized journalistic materials, and froze millions of assets. 21 “HK’s Apple Daily raided by 500 officers over national security law,” Reuters , June 17, 2021, reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/hong-kongs-apple-daily-newspaper-says-police-arrest-five-directors-2021-06-16 One of the first targets of the law when it was first implemented in 2020 was Apple Daily ’s founder, publisher, and opinion writer Jimmy Lai , who spent the entirety of 2021 in jail. The paper’s five most senior staff were eventually arrested. 22 Iain Marlow, “The Assault on Apple Daily,” Bloomberg , February 3, 2022, bloomberg.com/features/2022-apple-daily-china-hong-kong-crackdown Apple Daily chief editorial writer Yeung Ching-kei and columnist Fung Wai-kong were detained less than 10 days after the raid and arrested on suspicion of violating the National Security Law. 23 Helen Davidson, “Hong Kong police arrest editorial writer at Apple Daily newspaper,” The Guardian , June 23, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/23/hong-kong-police-arrest-editorial-writer-at-apple-daily-newspaper ; Helen Davidson, “Hong Kong police arrest senior Apple Daily journalist at airport,” The Guardian , June 27, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/28/hong-kong-police-arrest-apple-daily-journalist-airport-fung-wai-kong Eleven days later, the reader-funded and independent Stand News preemptively removed all of its columnists and opinion writing published before May. At the end of 2021, Stand News was also raided and shut down by the Hong Kong authorities. 24 “Security law: Stand News opinion articles axed, directors resign amid reported threats to Hong Kong digital outlets,” Hong Kong Free Press , June 28, 2021, hongkongfp.com/2021/06/28/security-law-stand-news-opinion-articles-axed-directors-resign-amid-reported-threats-to-hong-kong-digital-outlets/ ; “Hong Kong pro-democracy Stand News closes after police raids condemned by U.N., Germany,” Reuters , December 29, 2021, reuters.com/business/media-telecom/hong-kong-police-arrest-6-current-or-former-staff-online-media-outlet-2021-12-28

Hong Kong police have also targeted libraries in an attempt to bar access to pro-democracy writing and quash the potential spread of public dissent. When the law was first implemented in the summer of 2020, books by Wong were swiftly removed. 25 Agence France-Presse , “Democracy books disappear from Hong Kong libraries, including title by activist Joshua Wong,” Hong Kong Free Press , July 4, 2020, hongkongfp.com/2020/07/04/democracy-books-disappear-from-hong-kong-libraries-including-title-by-activist-joshua-wong In the summer of 2021, an inquiry was launched into Shek Tong Tsui Public Library after it featured books written by Jimmy Lai on a “librarian’s choice” shelf. The inquiry resulted in one unnamed librarian’s suspension and the prohibition of lending any book titles that a government department believed breached the National Security Law. 26 Ng Kang-chung, “Hong Kong librarian suspended after books by jailed Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai put on recommended reading shelf,” South China Morning Post, July 1, 2021, sg.news.yahoo.com/hong-kong-librarian-suspended-books-114304238.html Later in the summer, five unnamed members of a speech therapists’ union were arrested for creating and publishing three electronic children’s books that illustrated the 2019 pro-democracy protests using imagery of sheep and wolves. 27 Agence France-Presse, “Five arrested in Hong Kong for sedition over children’s book about sheep,” The Guardian , July 22, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/22/five-arrested-in-hong-kong-for-sedition-over-childrens-book-about-sheep In the face of these detentions and imprisonments, concerns about running afoul of the ambiguously defined crimes of the National Security Law have resulted in a tangible atmosphere of self-censorship. At the 2021 Hong Kong Book Fair—the first since 2019—books that could potentially be considered politically risky were culled from display, as publishers and exhibitors reportedly exercised a new spirit of self-discipline in curating their selections. 28 Sara Cheng and Joyce Zhou, “Self-censorship expected as Hong Kong book fair held under national security law,” Reuters , July 13, 2021, reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/self-censorship-expected-hong-kong-book-fair-held-under-national-security-law-2021-07-13 In preparation for the fair, one participating publisher said, “[W]e self-censor a lot this time. We read through every single book and every single word before we bring it here.” 29 Associated Press, “Self-censorship hits Hong Kong book fair in wake of national security law,” The Guardian , July 15, 2021, theguardian.com/books/2021/jul/15/self-censorship-hits-hong-kong-book-fair-in-wake-of-national-security-law

In Tibet , the number of writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned during 2021 increased from six to eight. Writers and public intellectuals are commonly detained for reasons ranging from critically responding to state encroachments on Tibetan language and education, to alleged displays of support for the Dalai Lama, to broader expressions of support for free expression or denunciations of censorship. The charges brought against them are often related to spurious national security crimes, or are undisclosed to the public. In March 2021, writer Gangkye Drubpa Kyab —a poet, teacher, former political prisoner, and author of books on the 2008 Tibetan unrest—was arrested in Kardze, but his whereabouts and the charges against him remain unknown. 30 Choekyi Lhamo, “Chinese police detain six noted Tibetans in Kardze,” Phayul , April 15, 2021, phayul.com/2021/04/15/45489 Prominent writer Go Sherab Gyatso disappeared in October 2020, and later appeared in state custody in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. In 2021 the Chinese government responded to a United Nations request for further information about Go Sherab Gyatso’s incommunicado detention and reasons for his arrest, claiming that he was detained for “inciting secession.” Four months later, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison on the charge, which rights groups and his relatives believe is in connection with his writing that touched on Tibetan politics and free expression. 31 “Arbitrarily detained Tibetan Scholar, Go Sherab Gyatso covertly sentenced to 10 years,” Central Tibetan Administration, December 16, 2021, tibet.net/arbitrarily-detained-tibetan-scholar-go-sherab-gyatso-covertly-sentenced-to-10-years ; Lhuboom, “Tibetan writer given 10-year prison term in secret trial,” Radio Free Asia , December 10, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/tibet/trial-12102021135859.html ; “China: Release Tibetan scholar Gō Sherab Gyatso from arbitrary detention,” Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, April 16, 2021, tchrd.org/china-release-tibetan-scholar-go-sherab-gyatso-from-arbitrary-detention In a similarly clandestine fashion, poet and writer Gendun Lhundrub has remained in detention without trial or public information about his arrest since December 2020. 32 “Qinghai monk writer missing for more than a year after Chinese ‘arrest’,” Tibetan Review , January 26, 2022, tibetanreview.net/qinghai-monk-writer-missing-for-more-than-a-year-after-chinese-arrest

The majority of cases in Tibet include writers who have been imprisoned for multiple years. Well-known online writer and editor of the first-ever Tibetan literary website Chomei, Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang had been in prison since 2009 for “leaking state secrets.” While no evidence for this charge has been made public, it is likely related to his website and writing focused on Tibetan literature; Chomei had been censored online prior to Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang’s imprisonment. 33 “Founder of Tibetan cultural website sentenced to 15 years in closed-door trial in freedom of expression case,” International Campaign for Tibet, November 16, 2009, savetibet.org/founder-of-tibetan-cultural-website-sentenced-to-15-years-in-closed-door-trial-in-freedom-of-expression-case ; “Tibetan Literary Website Founder Sentenced to 15 Years in Prison,” Free Tibet, accessed March 11, 2022, freetibet.org/freedom-for-tibet/political-prisoners/case-studies/kunchok-tsephel/ Monk and online writer Jo Lobsang Jamyang has been serving a seven-year and six-month sentence for “leaking state secrets” since 2015. Tibetans familiar with Jamyang’s writing suspect that his articles on free expression and environmental degradation and debates with other Tibetan writers may have led to his imprisonment. 34 “Lobsang Jamyang,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed March 22, 2022, cpj.org/data/people/lobsang-jamyang Further details are unknown, as Jamyang was convicted in secret by a Wenchuan county court in Ngaba prefecture. 35 Yeshe Choesang, “Tibetan writer Lomig is handed 7-year term on unknown charges,” The Tibet Post , May 9, 2016, thetibetpost.com/en/news/tibet/5000-tibetan-writer-lomig-is-handed-7-year-term-on-unknown-charges ; Tenzin Gaphel, “Tibetan writer Lomig arbitrarily arrested in restive Ngaba County,” Tibet Express , April 22, 2015, tibetexpress.net/1265/tibetan-writer-lomig-arbitrarily-arrested-in-restive-ngaba-county Multiple songwriters, including Trinley Tsekar , Khado Tsetan , and Lhundrub Drakpa , also remain detained for writing lyrics that explore Tibetan identity, culture, and critical opinions of the Chinese government’s policies. 36 “China imprisons two Tibetans for song praising His Holiness the Dalai Lama,” Central Tibetan Administration, July 21, 2020, tibet.net/china-imprisons-two-tibetans-for-song-praising-his-holiness-the-dalai-lama ; “China sentences Tibetan singer to six years in prison,” Central Tibetan Administration, October 30, 2020, tibet.net/china-sentences-tibetan-singer-to-six-years-in-prison

In Xinjiang , the brutal repression of Uyghur and other Turkic minorities alongside the crackdown on cultural institutions has continued. At least 34 writers and public intellectuals were detained or imprisoned for their writing and work in the region during 2021, almost as many as in the rest of China. However, as noted in previous years’ reports, this figure is certainly an incomplete accounting of the actual number. As human rights groups actively work to document the scale of internment in Xinjiang, efforts are stymied by the government’s censorship of domestic media, restricted foreign media access, and pervasive surveillance. 37 For additional information on the detention of writers, intellectuals, and other cultural figures in Xinjiang, see the following reports from the Uyghur Human Rights Project: Detained and Disappeared: Intellectuals Under Assault in the Uyghur Homeland , March 25, 2019, uhrp.org/report/detained-and-disappeared-intellectuals-under-assault-uyghur-homeland-html ; UHRP Update: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region Continues , January 28, 2019, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-continues-html ; UHRP Report: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region: Disappeared Forever? , October 2018, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-disappeared-forever-html During 2021, information leaks from a police database in Ürümqi further revealed how Muslims and ethnic minorities—such as Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz—are systematically surveilled through the collection of online communication, mobile phone data, and location data. 38 Yael Grauer, “Revealed: Massive Chinese Police Database,” The Intercept , January 29, 2021, theintercept.com/2021/01/29/china-uyghur-muslim-surveillance-police Writers who publish in their native languages and support literary institutions have been detained on spurious national security crimes of “extremism” and “separatism,” or have yet to be given any reason at all for their arrest.

Many writers and public intellectuals at the helm of institutions like magazines and publishing houses have been detained or imprisoned, effectively criminalizing institutions of literature and culture. Qurban Mamut , a Uyghur poet and longtime editor of culture journal Xinjiang Civilization , went missing in 2017 and was later confirmed to have been detained. Despite working within the confines of state censorship at Xinjiang Civilization , Mamut went missing a few months after he visited his son Bahram Sintash, who lives in the United States. 39 Austin Ramzy, “China Targets Prominent Uighur Intellectuals to Erase an Ethnic Identity,” The New York Times , January 5, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/01/05/world/asia/china-xinjiang-uighur-intellectuals.html ; “Qurban Mamut, a retired Uyghur editor held incommunicado in China,” Uyghur PEN, accessed March 1, 2022, uyghurpen.org/qurban-mamut-a-retired-uyghur-editor-held-incommunicado-in-china Tashpolat Tiyip —the former president of Xinjiang University, geography professor, and author of five books—also went missing in 2017 after he left Xinjiang for Germany to attend a conference. Two years after his disappearance, the UN urged the Chinese government to disclose his location and clarify the terms of his imprisonment. He has reportedly been held on separatism charges, and his family has received reports that he received a suspended death sentence, though the Chinese government has refuted this, claiming he was detained under corruption charges and not subject to a death sentence. 40 “China urged to disclose location of Uyghur academic Tashpolat Tiyip,” Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, December 26, 2019, ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2019/12/china-urged-disclose-location-uyghur-academic-tashpolat-tiyip ; Amy Anderson, “Death sentence for a life of service,” Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, January 22, 2019, u.osu.edu/mclc/2019/01/25/death-sentence-for-a-life-of-service ; “President of Xinxiang University Arrested Four Years Ago. Whereabouts Unknown to This Day,” Committee of Concerned Scientists, May 5, 2021, concernedscientists.org/2021/05/president-of-xinxiang-university-arrested-four-years-ago-whereabouts-unknown-to-this-day At least five writers and public intellectuals who worked at the Kashgar Publishing House remained in detention during 2021. Deputy editor-in-chief Ablajan Siyit ; editor Memetjan Abliz Boriyar ; two retired editors-in-chief, Osman Zunun and Abliz Ömer ; and retired editor and poet Haji Mirzahid Kerimi were all arrested in 2017 and 2018 for their involvement in publishing books deemed “problematic.” 41 Shohret Hoshur, “Veteran Editor of Uyghur Publishing House Among 14 Staff Members Held Over ‘Problematic Books’,” Radio Free Asia , November 26, 2018, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/editor-11262018155525.html Tragically, retired editor Kerimi died on January 9, 2021 while serving his prison sentence. 42 Shohret Hoshur, “Prominent Uyghur Poet and Author Confirmed to Have Died While Imprisoned,” Radio Free Asia , January 25, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/poet-01252021133515.html