Content Type

Topic Categories

- Data Visualization

- Research Briefs

- Email Signup

- Careers & Internships

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Home > Topics > Community Health Workers: Their Important Role in Public Health

Infographics

Community Health Workers: Their Important Role in Public Health

Coronavirus / Health Care Coverage

Published on: April 07, 2021. Updated on: April 13, 2021.

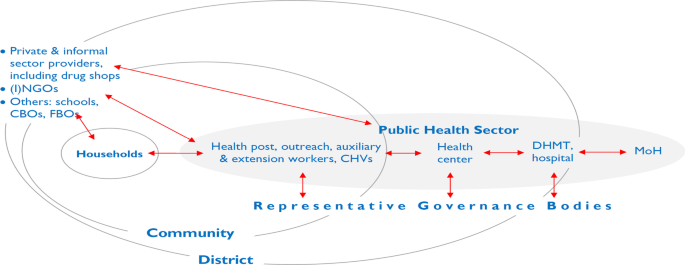

This infographic shows how Community Health Workers (CHWs) promote health equity and improve public health. The CHW workforce is diverse, growing, and drawing attention to its ability to address determinants of poor health. As trusted advocates, educators and counselors embedded in their communities, CHWs facilitate culturally competent service delivery. Tapping into this workforce can strengthen the response to COVID-19 and address longstanding inequities.

This infographic was reviewed by Denise Octavia Smith, MBA, CHW, PN, Founding Executive Director of the National Association of Community Health Workers .

Community health workers definitions : “Community Health Workers.” American Public Health Association.

CHWs’ many titles : “CDC - Community Health Worker Resources - STLT Gateway.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 18 Aug. 2016.

Not defined by training : Opinion by Kangovi, Shreya, et al. “Opinion: This Group of Workers Could Help Turnaround Quality of Life -- and the Economy.” CNN, 10 Feb. 2021.

Advance health equity, improve health outcomes, and reduce health care costs : “Community Health Workers: Evidence of Their Effectiveness.” Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the National Association of Community Health Workers.

Addressing social determinants of health : Peretz, Patricia J., et al. “Community Health Workers and Covid-19 - Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond: NEJM.” New England Journal of Medicine, 10 Mar. 2021.

Root causes of poor health: Opinion by Kangovi, Shreya, et al. “Opinion: This Group of Workers Could Help Turnaround Quality of Life -- and the Economy.” CNN, 10 Feb. 2021.

Examples of services CHWs provide:

- Outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy : “Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities.” American Public Health Association. 10 Nov. 2009

- Translation/interpreting, health care navigation, and tracking progress : “Rural Health Information Hub.” Community Health Workers in Rural Settings Introduction.

86,000 CHWs : "Community Health Worker National Workforce Study." U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions. March 2007.

Expected increase : “Health Educators and Community Health Workers: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1 Sept. 2020.

Call for rapid increase: NACHW National Policy Platform: Policy Recommendations to Respect, Protect and Partner with Community Health Workers During the Pandemic and Beyond.

President Biden’s proposal : “President Biden Announces American Rescue Plan.” The White House, The United States Government, 20 Jan. 2021.

American Rescue Plan : Yarmuth, John A. “H.R.1319 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.” Congress.gov, 11 Mar. 2021,

Partners in Health : “Public Health Job Corps: Responding to COVID-19, rebuilding the community health workforce.” Partners in Health United States. Updated 22 Jan. 2021.

CHWs sharing characteristics with community members : “Role of Community Health Workers.” National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CHW race and ethnicity : National Community Health Worker Advocacy Survey: 2014 Preliminary Data Report for the United States and Territories. Tucson, Arizona: Arizona Prevention Research Center, Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona; 2014.

Bilingual : “Community Health Workers in the Midwest: Understanding and developing the workforce” Wilder Research, June 2012.

CHW Employers : “Health Educators and Community Health Workers: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1 Sept. 2020.

Shift CHW employment : Malcarney MB, Pittman P, Quigley L, Horton K, Seiler N. The Changing Roles of Community Health Workers. Health Serv Res. 2017;52 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):360-382. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12657

Evidence of CHWs Effectiveness : “Community Health Workers: Evidence of Their Effectiveness.” Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the National Association of Community Health Workers.

- $2.47:1 return on investment : Kangovi, Shreya, et al. “Evidence-Based Community Health Worker Program Addresses Unmet Social Needs And Generates Positive Return On Investment: Health Affairs Journal.” Health Affairs, 1 Feb. 2020.

- 34% decrease in days in hospitals: Vasan, A, Morgan, JW, Mitra, N, et al. Effects of a standardized community health worker intervention on hospitalization among disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic conditions: A pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Health Serv Res. 2020; 55: 894– 901.

- Improve Glycemic Control : Palmas W, March D, Darakjy S, Findley SE, Teresi J, Carrasquillo O, Luchsinger JA. Community Health Worker Interventions to Improve Glycemic Control in People with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jul;30(7):1004-12.

- Mental Health : Weaver A, Lapidos A. Mental Health Interventions with Community Health Workers in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Health Care Poor Underserved.

Role of CHWs in COVID-19 response:

- Advocate for vaccinations : “Joint Statement on Ensuring Racial Equity in the Development and Distribution of a COVID-19 Vaccine.” Health Leads, 26 Jan. 2021.

- Trusted messengers : “To Strengthen The Public Health Response To COVID-19, We Need Community Health Workers, " Health Affairs Blog, May 6, 2020.

- Build Capacity : Advancing Equity & Public Health: The Community-Based Workforce Alliance.

- Address social needs and ensure care : Peretz, Patricia J., et al. “Community Health Workers and Covid-19 - Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond: NEJM.” New England Journal of Medicine, 10 Mar. 2021.

Recommendations and strategies for supporting this workforce:

- Funding, training, integrate, and promote : “Advancing the Profession of Community Health Workers: CHRT.” Center for Health & Research Transformation, 19 Feb. 2021.

- Combat compassion fatigue : “Battling Burnout: Self-Care and Organizational Tools to Increase Community Health Worker Retention and Satisfaction.” Health Leads, 23 Jan. 2020.

- More research is needed : Peretz, Patricia J., et al. “Community Health Workers and Covid-19 - Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond: NEJM.” New England Journal of Medicine, 10 Mar. 2021.

The National Association of Community Health Workers :

An Environmental Scan to Inform Community Health Worker Strategies within the Morehouse National COVID-19 Resiliency Network : Jane Berry, Aurora GrantWingate, and Denise Octavia Smith. The National Association of Community Health Workers, the Morehouse School of Medicine, and the National COVID-19 Resiliency Network. December 2020.

NACHW National Policy Platform : Policy Recommendations to Respect, Protect and Partner with Community Health Workers During the Pandemic and Beyond.

The Penn Center for Community Health Workers

Rural Community Health Workers Toolkit : Rural Health Information Hub

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Blog : Proctor, Dwayne. “Community Health Workers: Walking In The Shoes of Those They Serve.” RWJF , 2 Feb. 2021.

Marill, Michele Cohen. “Community Health Workers, Often Overlooked, Bring Trust to the Pandemic Fight.” Kaiser Health News , 10 Feb. 2021 .

Waters, Rob, et al. “Community Workers Lend Human Connection To COVID-19 Response: Health Affairs Journal.” Health Affairs , 1 July 2020,

Shreya Kangovi, Uché Blackstock. “Opinion | Community Health Workers Are Essential in This Crisis. We Need More of Them.” The Washington Post , WP Company, 3 July 2020.

We think you'll also like

March 25, 2021

Community Health Workers & Pharmacists: Their Frontline Role in the Response to COVID-19

Get nihcm updates

Updates on timely topics and webinars delivered to your inbox

More Related Content

May 01, 2024

Telehealth: A Vital Piece of the Care Access Puzzle

Cost & Quality / Affordability / Health Care Coverage / Health Care Reform

Mini-Infographics

Published on: January 11, 2024.

Respiratory Illnesses are Elevated Across the Country

Coronavirus

Research Insights

Published on: November 08, 2023. Updated on: November 08, 2023.

The Health & Economic Consequences of Firearm Injuries in Children on Survivors & Families

Cost & Quality / Behavioral Health / Health Care Coverage / Social Determinants of Health

See More on: Coronavirus | Health Care Coverage

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Positionality of community health workers on health intervention research teams: a scoping review.

- 1 Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2 University of Arizona Health Sciences Library, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

Community health workers (CHWs) are increasingly involved as members of health intervention research teams. Given that CHWs are engaged in a variety of research roles, there is a need for better understanding of the ways in which CHWs are incorporated in research and the potential benefits. This scoping review synthesizes evidence regarding the kinds of health research studies involving CHWs, CHWs' roles in implementing health intervention research, their positionality on research teams, and how their involvement benefits health intervention research. The scoping review includes peer-reviewed health intervention articles published between 2008–2018 in the U.S. A search of PubMed, Embase and CINAHL identified a total of 3,129 titles and abstracts, 266 of which met the inclusion criteria and underwent full text review. A total of 130 articles were identified for a primary analysis of the research and the level of CHWs involvement, and of these 23 articles were included in a secondary analysis in which CHWs participated in 5 or more intervention research phases. The scoping review found that CHWs are involved across the spectrum of research, including developing research questions, intervention design, participant recruitment, intervention implementation, data collection, data analysis, and results dissemination. CHW positionality as research partners varied greatly across studies, and they are not uniformly integrated within all stages of research. The majority of these studies employed a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach, and CBPR studies included CHWs as research partners in more phases of research relative to non-CBPR studies. This scoping review documents specific benefits from the inclusion of CHWs as partners in health intervention research and identifies strategies to engage CHWs as research partners and to ensure that CHW contributions to research are well-documented.

Introduction

Using the community health worker (CHW) workforce in health promotion programs to reach vulnerable and marginalized populations has become a best practice in addressing health disparities. A CHW is “a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served” ( 1 ). CHWs work under a variety of job titles, including promotores de salud , community health advisors, community health representatives, lay health advisors, and outreach workers. CHWs leverage their deep connections within the community to be a liaison between health services and community residents. In this effort, CHWs assume diverse and wide-ranging responsibilities, including patient outreach, health education and assessments, care coordination, cultural mediation between individuals and social service systems, and individual and community advocacy ( 2 ). Studies have shown that CHWs are highly effective in increasing healthcare utilization ( 3 – 6 ), preventive screening ( 7 ) and health behavior change ( 8 ).

While research on CHW interventions has demonstrated effectiveness in improving health outcomes, CHWs themselves are increasingly incorporated as members of intervention research teams ( 9 , 10 ). This activity is reflected in the Progress Report of the Community Health Worker (CHW) Core Consensus (C3) Project, a recent national study and consensus-building process to revisit CHW core competencies which added participation in evaluation and research as a new CHW core role and competency ( 2 ). The CHW profession encompasses competencies that have potential benefit to health intervention research ( 2 , 10 – 12 ). They have a deep understanding of the challenges faced by their communities and can ensure that health interventions address communities' needs. As trusted individuals, CHWs may be well-positioned to involve community members in research studies, particularly among underserved populations ( 12 – 14 ). CHWs can utilize their cultural insights to ensure that intervention implementation and data collection methodologies are responsive to community norms, language(s), and beliefs ( 12 ). Scholars have also noted that CHWs' input can be essential to interpreting participants' experiences and perspectives, thus elevating community members' voices within research and improving the quality of the data analysis ( 10 , 15 , 16 ).

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) that seeks to engage community members as partners may be more likely to incorporate CHWs to increase representation of community priorities ( 2 , 17 , 18 ). The CBPR approach intentionally delineates each phase of the research as an opportunity for community engagement, and CHWs' immersion within their communities positions them to represent and/or facilitate the engagement of community members in CBPR studies. While CHWs possess critical assets and skills to participate meaningfully across all phases of research, it is unknown the extent to which researchers engage with CHWs as partners, thus accessing their full scope of practice.

This article describes the results of a scoping review designed to synthesize the nature of CHW involvement across the phases of research, with the overall aim of identifying specific ways in which this workforce can enhance the quality of health intervention studies. The general purpose of a scoping review is to map key concepts underpinning a research area, especially one that is complex and/or understudied ( 19 ). In conducting the scoping review, we examined the following questions: (1) What types of research studies involve CHWs? (2) How are CHWs involved across the phases of research? (3) What is the nature of CHW positionality on research teams? (4) In what ways does CHW involvement benefit the quality of health intervention research?

Materials and Methods

Search strategy.

An initial review of the Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Scoping Reviews and Implementation Reports, the Cochrane Database of Scoping Reviews, and the Campbell Collection confirmed no existing scoping review on the subject area of CHW roles in intervention research. We collaborated with a medical librarian to design a comprehensive search strategy by developing terms for the concept areas “community health workers,” to identify CHWs working under an array of job titles, and “community-based participatory research,” to ensure that we were identifying studies that were most likely to engage the CHW workforce. Because our search term domains have numerous synonyms, we developed a full list of search terms for each. We then conducted a search for English-language articles in the electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL on September 28, 2018.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We referred to pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria for both title and abstract screening and subsequent full-text review. During title and abstract screening, we applied the following criteria:

1. Articles were peer-reviewed health intervention studies published from 2008–2018

2. Articles included study results

3. Articles included “CHW” (or an alternative name included within our search) within the title and/or abstract

4. Article's description of CHWs aligns with the APHA's definition

5. Articles described interventions within the U.S.

We excluded gray literature, study protocol papers, conference abstracts, formative research (i.e., focus groups, needs assessments), literature reviews, trainings, process evaluations (no outcome data), secondary data analyses, and articles presenting only baseline results of health interventions. We focused on interventions from the U.S. only given that the aforementioned C3 report had newly identified participation in research and evaluation as a new competency for CHWs within the U.S. only. We excluded interventions that involved patient navigators and health educators based upon the CHW Standard Occupational Classification, which differentiates these positions from CHWs ( 20 ). We also ensured that the article's description of CHWs aligned with the APHA definition of CHWs ( 1 ). If it was also not explicit that the CHWs were from the community served, the article was excluded.

Study Screening

Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts and reviewed the selected full-text articles using Covidence, a web-based program to manage literature reviews. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved through direct discussion at all stages.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers, the first and second author, independently extracted relevant data from the included studies into separate but identical Excel spreadsheets. Within the primary analysis, we noted characteristics of the health intervention, including intervention focus, study design (if the study was a randomized-control trial or not), if the study methodology included a CBPR approach, the target population and the CHW job title CHW (i.e., CHW, lay health worker, promotora , etc.). Reviewers then assessed CHW involvement (CHWs involved = 1, CHWs not involved = 0) across the following research phases: identifying the research question; intervention design; instrumentation/measurement design; recruitment/participant eligibility; intervention implementation; data collection; data analysis; and dissemination/action. Lastly, the reviewers sought to ascertain the level of expertise of CHWs by evaluating the described training and experience, with a specific focus on CHW core competencies ( 2 ). CHW core competencies refer to core roles and skills that constitute CHWs' full scope of practice such as cultural mediation, providing culturally appropriate health education and relationship building ( 2 ). Those studies that hired explicitly experienced CHWs, we interpreted as CHWs proficient in the core competencies. The reviewers then compared the information extracted and resolved any discrepancies in intervention characteristics through reexamination of the article. We calculated the total number of research phases in which CHWs were involved for each article, as well as the percentage of studies that included CHWs in each phase. To explore the benefits of CHW involvement, we conducted a secondary analysis of those articles in which CHWs were involved in 5 or more research phases.

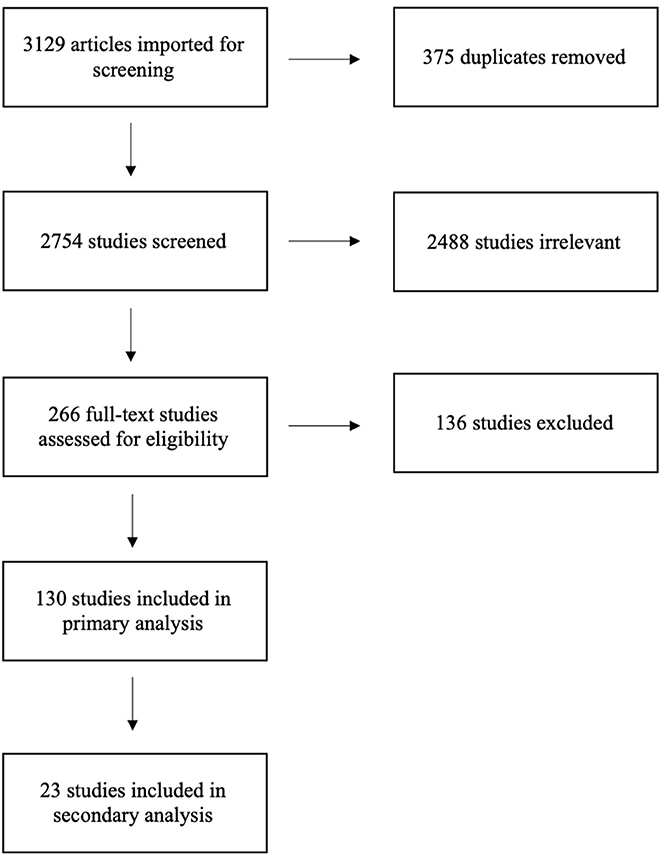

The initial search resulted in a total of 3,129 articles for review ( Figure 1 ). After removing duplicates in Endnote, we reviewed 2,754 titles and/or abstracts articles against the inclusion criteria to determine eligibility for full-text review. A total of 266 articles underwent full-text review, and 130 articles fitting the criteria were included in the primary analysis (the list of all articles and their full citations is available in Data Sheet 1 ). For the secondary analysis, we extracted additional information from 23 of the articles which described research projects in which CHWs participated in 5 or more phases.

Figure 1 . PRISMA Flow Diagram of Scoping Review Process for Examining CHWs in Research.

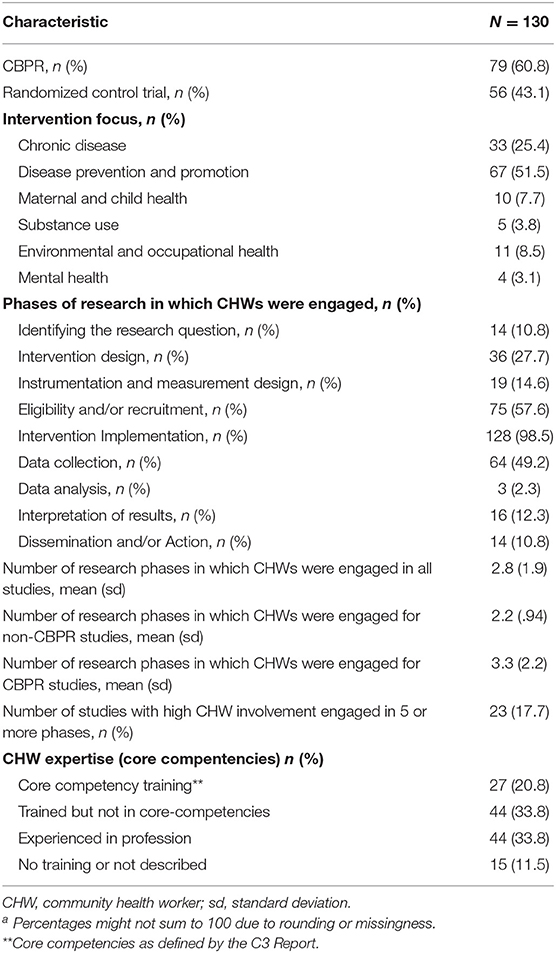

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 130 health intervention studies, the number of research phases engaging CHWs, and types of CHW training. More than half of the studies (51.5%) focused on disease prevention and promotion and 25.4% of studies targeted individuals with a chronic disease. As expected, the majority (60%) were CBPR studies, while the remaining 40% were non-CBPR studies. Additionally, 43.1% of the studies were randomized-control trials, while the remainder employed quasi-experimental or non-experimental study designs. Across the phases of research, almost all studies (98.5%) utilized CHWs to implement the health intervention. CHWs were also frequently involved in participant eligibility and/or recruitment (57.6%) and data collection (49.2%). CHWs were much less frequently involved in identifying the research question (10.8%), data analysis (2.3%), and research dissemination/action (10.8%).

Table 1 . Summary of health intervention characteristics, CHW research engagement, and CHW training. a

In examining CHW expertise, 33.8% of the studies worked with experienced CHWs and an additional 20.8% of the studies trained newly hired CHWs in core competencies. Another 33.8% provided training with CHWs that did not explicitly include core competencies. The remaining studies (11.5%) either didn't describe the training provided or did not mention training or experience of the CHWs. Notably, 64.6% of CBPR studies included CHWs proficient in core competencies, compared to 39.2% among non-CBPR studies. This suggests that participatory researchers may have greater understanding of the relevance of the broader scope of practice in CHW effectiveness. Additionally, the range CHW involvement across phases for non-CBPR studies was one to four, while CBPR studies engaged CHWs in one to nine phases. However, the research goals of the non-CBPR studies were less focused on community engagement and may have been less likely to benefit from CHWs' strengths as a workforce.

Although not documented in Table 1 , the target populations of the interventions varied by race and ethnicity, disease focus (i.e., diabetes, hypertension), health behavior (i.e., physical activity), occupation, and/or geographic location. The titles of the CHWs within the interventions were wide-ranging, and included promotoras , lay health workers, lay health advisors, community health advisor, community health coaches, community wellness coaches, care guides, resident health advocates, and women's health advocates.

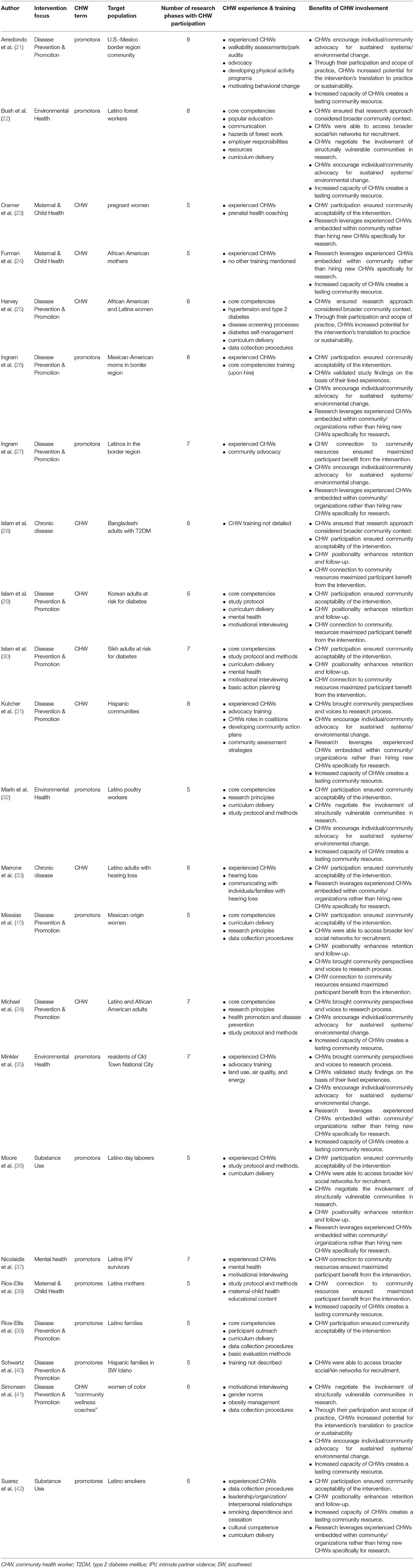

Secondary Analysis

To identify the characteristics of studies that utilized a broader scope of CHW practice and examine the extent to which the research benefited from CHW involvement, we reviewed those studies in which CHWs engaged in five or more phases ( n = 23). These studies all described utilizing a CBPR approach. For each study, we documented and synthesized the articles' descriptions of CHW roles and contributions to the quality of the study. Table 2 summarizes the results of the secondary analysis. Notably, in all but four studies, the CHWs were described as experienced or were trained in core competencies as part of the study. Across the studies, CHWs were also trained in intervention delivery, data collection methodologies, research principles, health conditions/diseases, program development, advocacy, and coalitions/networking.

Table 2 . CHW involvement in phases of research and benefits across high CHW involvement studies.

Our examination of the 23 studies identified 12 distinct benefits of CHW involvement throughout the research process. In many of the studies, CHWs were vital to developing study approaches, methodologies, and interventions that were appropriate for the communities served. More specifically, CHWs increased the research team's awareness of the broader community context and social determinants of health impacting the daily lives of potential study participants ( 22 , 25 , 28 ). Bush et al. ( 22 ) noted the ways in which CHWs increased researchers' awareness to issues facing Latino forest workers (i.e., wage theft, immigration status, land-lord tenant retaliation, etc.) that could influence their capacity to prioritize the occupational safety concerns that were the focus of the intervention. In the study conducted by Messias et al. ( 15 ), CHWs provided researchers with crucial information regarding participants' family care-giving responsibilities, employment obligations, and transportation needs which allowed for effective planning and scheduling of intervention sessions. The articles also demonstrated that CHWs contributed to the community acceptability of interventions , particularly in ensuring the cultural congruence of the intervention and identifying culturally relevant modes of intervention delivery ( 15 , 23 , 26 , 28 – 30 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 39 , 42 ). CHWs implementing the Salud S í (Health Yes) intervention were responsible for refining intervention strategies to respond to the needs and characteristics of study participants, such as incorporating spirituality to address depression ( 26 ). In other studies, CHWs provided their insights and suggestions to adapt already developed curriculums. Moore et al. ( 36 ) explained how the CHWs made changes to the intervention manual to better incorporate Latino cultural values, such as familism, and bring awareness to important stressors confronted by day laborers (i.e., acculturative stress, discrimination, and poverty). In Suarez et al. ( 42 ), CHWs identified community settings where they could effectively engage Latino smokers and deliver health education (churches, Latino-owned businesses, home visits, Consulate of Mexico, etc.).

The studies underscored CHWs' ability to engage vulnerable or hard-to-reach populations in research, particularly ethnic-minority populations. This was often achieved by CHWs accessing their broader social and/or kin networks for participant recruitme nt ( 15 , 22 , 36 , 40 ). Recruitment efforts benefitted from the existing trust and rapport CHWs had with their community members. Messias et al. ( 15 ) documented how CHWs identified participants from their existing social networks within schools, churches, work, and the broader community. Furthermore, as noted by Bush et al. ( 22 ), CHWs tapped into their kinship networks, facilitating contact with large numbers of forest workers. The studies also demonstrated that CHWs negotiated the inclusion of structurally vulnerable communities in research ( 22 , 32 , 36 , 41 ), referring to populations whose positionality imposes physical or emotional suffering in patterned ways ( 43 ). This was particularly evident among interventions targeting low-wage laborers (i.e., forest workers and poultry workers). Sustaining the participation of these populations in the intervention required the efforts and capabilities of the CHWs. More specifically, Bush et al. ( 22 ) acknowledged that the CHWs' cultural knowledge, language fluency, and rapport were critical in engaging immigrant forest workers with deeply embedded fears related to immigration status. Similarly, Marín et al. ( 32 ) documented that their CHW program provided a safe environment for immigrant poultry workers to learn more about their rights to a safe workplace and advocate for their occupational safety, despite palpable fears of workplace retaliation.

Following recruitment, CHW positionality within the community enhanced participant retention in the study, ongoing data collection and follow-up ( 15 , 28 – 30 , 36 , 42 ). CHWs achieved this by developing trust and rapport with participants that enabled them to recognize and negotiate potential barriers to participation, as well as engendered a desire among participants to complete study processes. For example, researchers attributed high levels of participant retention and compliance with accelerometer measurements in a physical activity intervention to CHW continuous communication with participants ( 15 ). CHWs' ability to engage and retain participants throughout the study brought community perspectives and voices to research process ( 15 , 31 , 34 , 35 ). This was apparent in interventions involving CHW-led advocacy efforts. Kutcher et al. ( 31 ) described how CHWs were integral to including community residents impacted by health disparities in health coalitions, thereby providing a voice for stakeholders who traditionally lack power. CHWs were able to facilitate coalition meetings where there was equitable participation among community members, local agencies, and officials. CHWs also elevated community voices through data collection efforts. In an environmental justice initiative, CHWs served as “co-researchers” and led a survey of community residents to capture their concerns and priorities (i.e., asthma, land use, affordable housing, etc.), which later shaped local policy changes ( 35 ).

The few studies that involved CHWs in the data interpretation process demonstrated that they were able to explain or validate study findings based on their common experience with the study population ( 26 , 35 ). CHWs in Ingram et al.'s ( 26 ) study explained that women who initiated physical activity during the intervention were able to do so because the program created a culturally acceptable space for women to congregate. Without the organized classes, this activity was difficult to maintain. In an effort to enact policy changes consistent with the community's needs, Minkler et al. ( 35 ) described how CHWs presented to the City Council the results of a survey they implemented with community residents, which they supported by sharing their experiences as community members and mothers.

In several of the studies, CHW involvement increased the potential for the intervention's translation to practice or sustainability , and this finding applied to both program and systems level interventions ( 21 , 25 , 41 ). CHWs helped ensure that the intervention utilized appropriate strategies delivered in an appropriate fashion, taking into consideration the larger context of intervention delivery and the participants' lives. The CHW-driven advocacy efforts initiated as part of REACH projects were more likely to be sustained because the CHWs successfully engaged business owners in prioritizing and implementing changes ( 25 ). Similarly, the Arredondo et al. ( 21 ) study documented an increased intention to use park facilities among community members after CHWs worked with youth to identify, advocate for, and attain structural changes. On the programmatic level, the Detroit Department of Health continued to employ CHWs and outreach strategies after demonstrating the effectiveness designed by the CHWs in the HC project ( 25 ). Notably, an intervention's sustainability was maximized when the research leveraged experienced CHWs that were already embedded in community or local organizations, rather than hiring new CHWs specifically for research ( 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 42 ). This is largely because CHWs could incorporate intervention activities into their existing work after the conclusion of the study. In a breastfeeding intervention, the CHWs continued to use curricular models within their existing MomsFirst programming ( 24 ).

Importantly, CHWs' connections to community resources helped to maximize participants' benefit from the intervention ( 15 , 27 – 30 , 37 , 38 ). Participants were connected to a broader range of community resources more efficiently and also frequently received ongoing services from these entities. CHWs linking participants to community resources (i.e., food stamps, English language programs, etc.) were also cited as reasons for high feasibility and/or acceptability of interventions ( 28 – 30 ). CHWs connected participants to needed services even when not a stated objective of the intervention. For example, within a breastfeeding intervention for Latina mothers, participants reported an increased understanding of where to get help for post-partum depression because the CHW shared her knowledge of relevant services ( 38 ).

CHW involvement encouraged individual/community advocacy to enact sustained health-promoting individual and system level changes ( 21 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 41 ). The interventions focusing on occupational safety empowered immigrant workers to advocate for better working conditions ( 22 , 32 ). Despite notable fears and susceptibility to retaliation among the workers, the support and information from the CHWs empowered them to address workplace hazards such as notifying their supervisors ( 22 , 32 ). In other studies, CHWs mobilized community members, organizations, and policy-makers to implement policy-systems-environment (PSE) strategies. CHWs encouraged community members to think ecologically about their health and identify advocacy-oriented solutions to improve community social determinants of health. CHWs also modeled behaviors for participating in advocacy coalitions so to support the capacity of community members to work with local representatives/officials to enact PSE changes ( 31 ). The organization efforts of the CHWs led to a variety of individual and community changes, such as restorations of a local park ( 21 ), improvements to neighborhood conditions, enhanced community opportunities, better access to services ( 27 ), increased access to healthy foods, and the adoption of policies to integrate physical activity opportunities into schools ( 31 ).

Finally, the increased capacity of CHWs, through their training and increased experience, created a lasting community resource ( 21 , 22 , 24 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 41 , 42 ). As described by Bush et al. ( 22 ), after the occupational safety intervention, the CHWs' participation in the program promoted their leadership skills and established them as recognized resources within the community. The CHWs' experiences in research empowered them to take on additional roles, responsibilities, or new jobs. After their demonstrated success in advocacy, Kutcher et al. ( 31 ) mentioned that the CHWs adopted new roles facilitating coalition meetings, collaborating with local officials, and representing the project in marketing/communications efforts. At the end of the occupational safety program, Marín et al. ( 32 ) noted the promoters were provided new opportunities; one was later hired for a local literacy project, and two others were employed by a worker center supporting low-wage immigrant workers.

Thorough review of CHWs' activities within health intervention research provides important insights for community-academic research teams regarding the breadth of roles CHWs can assume within research and how they can strengthen health research initiatives. Overall, the results of the primary and secondary analysis revealed that CHW participation in health intervention research is diverse, in terms of the kinds of studies they are involved (i.e., study design and focus), their roles in the research process and their positionality on the research team. The majority of studies, and particularly those that engaged CHWs in more phases of the research applied a community based participatory research approach. This finding is consistent with the C3 report's and other scholars' assessments that CHWs facilitate community participation and representation in health research ( 2 ). However, a substantial percentage of the studies were not participatory, suggesting that both participatory and non-participatory researchers recognize the relevance of CHWs to health interventions. What did differentiate CBPR and non-CBPR studies was the range of research phases with CHW involvement. CHWs were involved in up to 9 phases within CBPR studies, relative to up to 4 within non-CBPR studies. This result indicates that CBPR studies are more likely to integrate CHWs across the entirety of research process, beginning from identification of the health issue to dissemination of the results.

In nearly all the studies, CHWs were responsible for implementing the intervention under study, and those studies that employed CHWs in this role alone are perhaps better able to distinguish the effectiveness of the CHW-facilitated intervention or the CHW workforce in addressing a particular health issue (i.e., glycemic control, hypertension, etc.). It is not surprising that intervention implementation, participant recruitment, and data collection, defined as discrete phases of research in the CBPR-framework, were the research phases with the highest CHW involvement across the studies. These phases of research involve CHWs in direct interaction with study participants to encourage their participation in the study, facilitate their engagement in the study, or talk with them about their health. Given CHWs' connections within their communities and their effectiveness in engaging with community members, it makes sense that CHWs performed these activities most frequently.

Conversely, CHWs were least involved in identifying the research question, data analysis, and research dissemination. This finding represents lost opportunities for ensuring that not only the research focus, but also research findings, are relevant to communities. Researchers would need to engage CHWs as research partners early in the process if they were to be included in defining the research question and ensuring that the interventions address relevant health issues. As underscored in the secondary analysis, CHWs can also aid in data analysis by explaining study findings, interpreting the voices and perspectives of the study participants, and further validating the data based on their lived experiences. Very few of the studies involved CHWs in a dissemination/action phase of the research, which is unfortunate. This phase is intrinsic to CBPR in ensuring that research contributes to social change ( 44 ). While it is possible that these research projects continued into an action phase not reported in the article, it is also the most difficult phase of research and the one for which researchers are least prepared. This may be the major argument for including CHWs as full members on research teams so that they are well-positioned to carry the research forward into community action.

This aspect of CHW involvement is related to their positionality on research teams and the power dynamics between community and academic partners that limit or maximize CHWs' contributions to research. The articles provide several strategies for including CHWs and building their capacity in a partnership role. In some cases, researchers invited CHWs to sit on the decision-making body of the research team, such as the community action board (CAB) or steering committee. This inclusion formalized their leadership position among academics and other stakeholders. As recognized leaders and stakeholders, CHWs are ideally positioned to share their knowledge of community during the formative phases of the study to inform the research approach at the outset. The projects also trained CHWs in research methodologies. While these trainings were frequently not described in-depth, a co-learning environment in which the mutual and shared expertise is valued among all partners would certainly facilitate recognition of CHW contributions. Additionally, CHWs that were incorporated across the phases of research had more opportunities to improve research processes and ensure community benefit. Because CHWs instinctively and are trained to prioritize community interests, they are more likely to identify and address ethical issues related to research that might otherwise go unrecognized ( 18 ).

The inclusion of CHWs did not go without challenges. Researchers noted some difficulty in CHWs adhering to research protocols due to concerns of maintaining rapport with community members. One academic-community partnership discussed CHWs encountering tension between fidelity to procedures of randomized-control trials and community norms ( 15 ). Another research team described differing goals between academic and community partners (including CHWs), where academic partners prioritized data and community partners prioritized funding and policy ( 24 ). While it is important that CHWs are trained in research ethics and procedures, the current study's results highlight how CHWs' knowledge of the community is integral to conducting successful research. For example, Furman et al. ( 24 ) explained how some of the staff were hesitant to endorse the research project due to conflicts with on-the-ground realities of the community members served. Thus, if CHWs are challenged by the research protocol, that could signal potential incongruence with community practices that the research team should address. Furthermore, it was clear that research teams valued the community rapport CHWs possessed, but some authors described how some CHWs faced difficulties in leveraging connections outside of their social networks ( 15 , 22 ). Also, a few studies documented CHWs facing personal conflict between their responsibilities as CHWs engaged in research and their obligations to spouses/family ( 32 , 35 ).

Limitations

The scoping review is also characterized by certain limitations. Our knowledge of the CHWs' involvement within the included studies is limited to what was documented in the articles. Thus, if CHWs' participation was not thoroughly described or underreported by the author(s), it was not reflected in our results. We did not seek to evaluate the quality of the research and did not compare it to similar research that did not use CHWs. Also, we did not examine individual health outcomes or community outcomes which we hope would be improved with CHW involvement. Our scoping review does not establish the desired benefits, rather it is an attempt to synthesize lessons learned from a broad variety of research studies and approaches. Lastly, these results do not capture lessons to be learned from research interventions with CHWs outside the U.S. Future research should examine the roles of CHWs within health intervention research globally.

This scoping review highlights the potential benefits of incorporating CHWs as partners in health intervention research studies. Our findings demonstrate that CHWs can improve the quality of research not only in CBPR studies that seek to engage community members in the research process, but also in non-CBPR studies, including those utilizing experimental designs. We found that CHWs inform study design to consider contextual factors, improve the content and delivery of health interventions, and validate and explain research findings and most importantly, both insure and increase the benefits of research for the individuals and communities involved.

Author Contributions

KC lead the development of the manuscript. KC and MI collaborated in developing the inclusion/exclusion criteria, conducting article screening, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. DM directed the development of the search strategy, implemented the search in the databases, and lead the writing of the methods section of the manuscript. AL edited continuous iterations of the manuscript draft and provided input on the direction of the data analysis.

This journal article was supported by the Grant or Cooperative Agreement No. DP005002 under the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Centers Program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00208/full#supplementary-material

Data Sheet 1. Data extraction table for primary analysis articles to account for some spelling errors, more accurate listings of some of the target populations of the intervention studies, and accuracy in dates of publication.

1. American Public Health Association (APHA). Community Health Workers (2019). Available online at: https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (November 1, 2019).

Google Scholar

2. Rosenthal EL, Rush CH, Allen C. Progress Report of the Community Health Worker (CHW) Core Consensus (C3) Project: Building National Consensus on CHW Core Roles, Skills, and Qualities . (2016) Available online at: http://files.ctctcdn.com/a907c850501/1c1289f0-88cc-49c3-a238-66def942c147.pdf?ver=1462294723000

3. Pérez-Escamilla R, Damio G, Chhabra J, Fernandez ML, Segura-Pérez S, Vega-López S, et al. Impact of a community health workers–led structured program on blood glucose control among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: the DIALBEST trial. Diabetes Care. (2015) 38:197–205 doi: 10.2337/dc14-0327

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Ursua RA, Aguilar DE, Wyatt LC, Trinh-Shevrin C, Gamboa L, Valdellon P, et al. A community health worker intervention to improve blood pressure among Filipino Americans with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med Rep. (2018) 11:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.002

5. Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer EC, Sinco BR, Valerio M, Palmisano G, et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2253–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106

6. Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Joo JH, Lin FR, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:e3–28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987a

7. Han HR, Song Y, Kim M, Hedlin HK, Kim K, Ben Lee H, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening literacy among Korean American women: a community health worker–led intervention. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:159–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303522

8. Koniak-Griffin D, Brecht ML, Takayanagi S, Villegas J, Melendrez M, Balcázar H. A community health worker-led lifestyle behavior intervention for Latina (Hispanic) women: feasibility and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2015) 52:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.005

9. Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. (2011) 34:247–59. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7

10. Hohl SD, Thompson B, Krok-Schoen JL, Weier RC, Martin M, Bone L, et al. Characterizing community health workers on research teams: results from the centers for population health and health disparities. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:664–70. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302980

11. Brownstein JN, Hirsch GR, Rosenthal EL, Rush CH. Community health workers “101” for primary care providers and other stakeholders in health care systems. J Ambul Care Manage. (2011) 34:210–20. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c645d

12. Johnson CM, Sharkey JR, Dean WR, St John JA, Castillo M. Promotoras as research partners to engage health disparity communities. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2013) 113:638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.11.014

13. Choi E, Heo GJ, Song Y, Han HR. Community health worker perspectives on recruitment and retention of recent immigrant women in a randomized clinical trial. Fam Community Health. (2016) 39:53–61. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000089

14. Larkey LK, Gonzalez JA, Mar LE, Glantz N. Latina recruitment for cancer prevention education via community based participatory research strategies. Contemp Clin Trials. (2009) 30:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.08.003

15. Messias DK, Parra-Medina D, Sharpe PA, Treviño L, Koskan AM, Morales-Campos D. Promotoras de Salud: roles, responsibilities, and contributions in a multi-site community-based randomized controlled trial. Hisp Health Care Int. (2013) 11:62–71. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.11.2.62

16. Vaughn LM, Whetstone C, Boards A, Busch MD, Magnusson M, Määttä S. Partnering with insiders: a review of peer models across community-engaged research, education and social care. Health Soc Care Community. (2018) 26:769–86. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12562

17. Cupertino AP, Suarez N, Cox LS, Fernández C, Jaramillo ML, Morgan A, et al. Empowering promotores de salud to engage in community-based participatory research. J Immigr Refug Stud. (2013) 11:24–43. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2013.759034

18. Smith SA, Blumenthal DS. Community health workers support community-based participatory research ethics: lessons learned along the research-to-practice-to-community continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2012) 23(Suppl. 4):77–87. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0156

19. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Malcarney MB, Pittman P, Quigley L, Seiler N, Horton KB. Community Health Workers: Health System Integration, Financing Opportunities, and the Evolving Role of the Community Health Worker in a Post-Health Reform Landsacape (2015) . Available online at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_workforce_facpubs/11/ (April 15, 2019).

21. Arredondo E, Mueller K, Mejia E, Rovira-Oswalder T, Richardson D, Hoos T. Advocating for environmental changes to increase access to parks: engaging promotoras and youth leaders. Health Promot Pract. (2013) 14:759–66. doi: 10.1177/1524839912473303

22. Bush DE, Wilmsen C, Sasaki T, Barton-Antonio D, Steege AL, Chang C. Evaluation of a pilot promotora program for Latino forest workers in southern Oregon. Am J Ind Med. (2014) 57:788–99. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22347

23. Cramer ME, Mollard EK, Ford AL, Kupzyk KA, Wilson FA. The feasibility and promise of mobile technology with community health worker reinforcement to reduce rural preterm birth. Public Health Nurs. (2018) 35:508–16. doi: 10.1111/phn.12543

24. Furman L, Matthews L, Davis V, Killpack S, O'Riordan MA. Breast for success: a Community–Academic collaboration to increase breastfeeding among high-risk mothers in Cleveland. Prog Community Health Partnersh. (2016) 10:341–53. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0041

25. Harvey I, Schulz A, Israel B, Sand S, Myrie D, Lockett M, et al. The Healthy Connections project: a community-based participatory research project involving women at risk for diabetes and hypertension. Prog Community Health Partnersh. (2009) 3:287–300. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0088

26. Ingram M, Piper R, Kunz S, Navarro C, Sander A, Gastelum S. Salud Sí: A case study for the use of participatory evaluation in creating effective and sustainable community-based health promotion. Fam Community Health. (2012) 35:130–8. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824650ed

27. Ingram M, Schachter KA, Sabo SJ, Reinschmidt KM, Gomez S, De Zapien JG, et al. A community health worker intervention to address the social determinants of health through policy change. J Prim Prev. (2014) 35:119–23. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0335-y

28. Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Patel SD, Shapiro E, Tandon SD, Mukherji BR, et al. Evaluation of a community health worker pilot intervention to improve diabetes management in Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes in New York City. Diabetes Educ. (2013) 39:478–93. doi: 10.1177/0145721713491438

29. Islam NS, Zanowiak JM, Wyatt LC, Chun K, Lee L, Kwon SC, et al. A randomized-controlled, pilot intervention on diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyles in the New York City Korean community. J Community Health. (2013) 38:1030–41. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9711-z

30. Islam NS, Zanowiak JM, Wyatt LC, Kavathe R, Singh H, Kwon SC, et al. Diabetes prevention in the New York City Sikh Asian Indian community: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2014) 11:5462–86. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110505462

31. Kutcher R, Moore-Monroy M, Bello E, Doyle S, Ibarra J, Kunz S, et al. Promotores as advocates for community improvement: experiences of the western states REACH Su Comunidad consortium. J Ambul Care Manage. (2015) 38:321–32. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000073

32. Marín A, Carrillo L, Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Coates ML, Quandt SA. Ethnographic evaluation of a lay health promoter program to reduce occupational injuries among Latino poultry processing workers. Public Health Reports . (2009) 124(Suppl. 1):36–43. doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S105

33. Marrone N, Ingram M, Somoza M, Jacob DS, Sanchez A, Adamovich S, et al. Interventional audiology to address hearing health care disparities: Oyendo Bien pilot study. Semin Hear. (2017) 38:198–211. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601575

34. Michael YL, Farquhar SA, Wiggins N, Green MK. Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. J Immigr Minor Health. (2008) 10:281–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9078-2

35. Minkler M, Garcia AP, Williams J, LoPresti T, Lilly J. Sí se puede: using participatory research to promote environmental justice in a Latino community in San Diego, California. J Urban Health. (2010) 87:796–812. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9490-0

36. Moore AA, Karno MP, Ray L, Ramirez K, Barenstein V, Portillo MJ, et al. Development and preliminary testing of a promotora-delivered, Spanish language, counseling intervention for heavy drinking among male, Latino day laborers. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2016) 62:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.11.003

37. Nicolaidis C, Mejia A, Perez M, Alvarado A, Celaya-Alston R, Quintero Y, et al. Proyecto Interconexiones: pilot-test of a community-based depression care program for Latina violence survivors. Prog Community Health Partnersh. (2013) 7:395–401. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2013.0051

38. Rios-Ellis B, Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Espinoza L, Galvez G, Garcia-Vega M. Engaging community with promotores de salud to support infant nutrition and breastfeeding among Latinas residing in Los Angeles County: Salud con Hyland's. Health Care Women Int . (2015) 36:711–29. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.900060

39. Rios-Ellis B, Espinoza L, Bird M, Garcia M, D'Anna LH, Bellamy L, et al. Increasing HIV-related knowledge, communication, and testing intentions among Latinos: Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2010) 21:148–68. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0360

40. Schwartz R, Powell L, Keifer M. Family-based risk reduction of obesity and metabolic syndrome: an overview and outcomes of the Idaho partnership for Hispanic health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2013) 24:129–44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0106

41. Simonsen SE, Ralls B, Guymon A, Garrett T, Eisenman P, Villalta J, et al. Addressing health disparities from within the community: community-based participatory research and community health worker policy initiatives using a gender-based approach. Women's Health Issues. (2017) 27(Suppl. 1):S46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.09.006

42. Suarez N, Mendoza I, Garrett S, Ellerbeck EF. Success of “Promotores de Salud” in identifying immigrant Latino smokers and developing quit plans. Int Public Health J. (2012) 4:343–53.

43. Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol. (2011) 30:339–62. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725

44. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100(Suppl. 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036

Keywords: community health workers, intervention research, participatory research, health intervention, academic-community partnerships

Citation: Coulter K, Ingram M, McClelland DJ and Lohr A (2020) Positionality of Community Health Workers on Health Intervention Research Teams: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 8:208. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00208

Received: 18 February 2020; Accepted: 06 May 2020; Published: 16 June 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Coulter, Ingram, McClelland and Lohr. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kiera Coulter, kcoulter@arizona.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Community health workers and Covid-19: Cross-country evidence on their roles, experiences, challenges and adaptive strategies

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Oxford Policy Management, Delhi, India

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of International Public Health, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Roles Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Oxford Policy Management, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Roles Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Oxford Policy Management, Islamabad, Pakistan

Affiliation Oxford Policy Management, Abuja, Nigeria

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Oxford Policy Management, Oxford, United Kingdom

- Solomon Salve,

- Joanna Raven,

- Priya Das,

- Shuchi Srinivasan,

- Adiba Khaled,

- Mahwish Hayee,

- Gloria Olisenekwu,

- Kate Gooding

- Published: January 4, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447

- Reader Comments

Community health workers (CHWs) are a key part of the health workforce, with particular importance for reaching the most marginalised. CHWs’ contributions during pandemics have received growing attention, including for COVID-19. This paper contributes to learning about CHWs’ experiences during COVID-19, based on evidence from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Kenya and Ethiopia. The paper synthesises evidence from a set of research projects undertaken over 2020–2021. A thematic framework based on the research focus and related literature was used to code material from the reports. Following further analysis, interpretations were verified with the original research teams. CHWs made important contributions to the COVID-19 response, including in surveillance, community education, and support for people with COVID-19. There was some support for CHWs’ work, including training, personal protective equipment and financial incentives. However, support varied between countries, cadres and individual CHWs, and there were significant gaps, leaving CHWs vulnerable to infection and stress. CHWs also faced a range of other challenges, including health system issues such as disrupted medical supply chains, insufficient staff and high workloads, a particular difficulty for female CHWs who were balancing domestic responsibilities. Their work was also affected by COVID-19 public health measures, such as restrictions on gatherings and travel; and by supply-side constraints related to community access and attitudes, including distrust and stigmatization of CHWs as infectious or informers. CHWs demonstrated commitment in adapting their work, for example ensuring patients had adequate drugs in advance of lockdowns, and using their own money and time to address increased transport costs and higher workloads. Effectiveness of these adaptations varied, and some involved coping in a context of inadequate support. CHW are critical for effective response to disease outbreaks, including pandemics like COVID-19. To support CHWs’ contribution and protect their wellbeing, CHWs need adequate resources, managerial support, and motivation.

Citation: Salve S, Raven J, Das P, Srinivasan S, Khaled A, Hayee M, et al. (2023) Community health workers and Covid-19: Cross-country evidence on their roles, experiences, challenges and adaptive strategies. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(1): e0001447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447

Editor: Amrita Daftary, York University, CANADA

Received: June 7, 2022; Accepted: December 7, 2022; Published: January 4, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Salve et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: Synthesis and development of the paper were funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), UK Aid, under the ReBUILD for Resilience Research Programme Consortium (PO 8610 to JR). Financial support for the underlying projects was provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the Global Financing Facility, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Bank. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Community health workers (CHWs) are a key part of the health workforce in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), increasingly recognised as integral for effective and equitable health service delivery [ 1 – 4 ]. The umbrella term “CHW” encompasses diverse categories of health worker [ 4 ], such as community distributors, community-directed health workers, health auxiliaries, health promoters, family welfare educators, health volunteers, village health workers, community health aides, and barefoot doctors [ 5 ]. For this paper, we consider CHWs as health workers who are the first point of contact at community level, based in communities or at peripheral health posts, and who have some but fewer than two to three years of training [ 1 , 6 ]. Within this group, there is substantial diversity between countries and cadres in CHW responsibilities, skills and employment conditions [ 1 , 7 ].

CHWs undertake a wide range of tasks related to core health service provision, such as community mobilization, health promotion, and provision of preventive and clinical services [ 8 , 9 ]. Over the past decade, there has been a growing recognition of potential CHW roles in responding to pandemics [ 10 ]. Based in communities, and often from these same communities, CHWs are often the frontline and first point of contact when an outbreak hits [ 3 ]. For example, CHWs played multiple roles in the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa [ 11 – 15 ]. Most recently, CHWs have been active in the COVID-19 response[ 16 – 23 ]. Research has documented the roles played by CHWs in controlling COVID-19, and the challenges they have experienced [ 16 – 24 ]. As well as introducing new roles for CHWs, COVID-19 has affected their routine service delivery. International surveys in 2020 and 2021 showed significant disruption to primary and community health services, with disruptions to community care reported by more than half the countries in the world in late 2021 [ 25 – 27 ]. In many countries, community services were deliberately suspended or scaled back, but services were also affected by issues such as disruption to supply chains, shortage of health workers and demand-side constraints [ 27 ].

This article contributes to the growing understanding of CHW roles and experiences in the COVID-19 response, synthesising evidence from a set of research projects in six countries in South Asia and Africa: Ethiopia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. The article examines CHWs’ contributions to the response, the support provided to CHWs, and gaps in this support, challenges experienced by CHWs in delivering services, and adaptations or coping strategies that enabled service delivery. While guidelines were developed to support CHWs at an early stage in the COVID-19 pandemic [ 24 ], indications of widespread challenges for CHWs suggest a need for further evidence that can strengthen awareness and understanding of CHWs’ experiences and inform further measures to ensure they have adequate support.

The six countries included in this synthesis have all been significantly affected by COVID-19. All reported the first case during January–March 2020, and there was significant spread and community transmission by May [ 28 , 29 ]. COVID-19 added to other shocks experienced by these countries, including climatic shocks such as drought and floods in all 6 countries, and political instability or conflict in some, notably Ethiopia and Kenya. These countries are at different levels of development, but all face significant health system challenges–including financial constraints and health worker shortages, with all significantly below the WHO recommendation minimum of 44.5 skilled health workers (doctors, nurses and midwives) per 10,000 needed to achieve UHC and SDG3 [ 30 ] (see Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447.t001

CHWs play a critical role in each country. Their specific titles vary between the countries (see Table 2 for information on cadres referred to in this paper). Some are voluntary positions, while others have more formal status and salaries, and their roles, levels of training and other employment conditions vary. In most countries, the majority of these CHWs are female.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447.t002

The paper synthesises evidence from a set of research projects conducted or supported by Oxford Policy Management (OPM) over 2020–21 (see Table 3 and further details in S1 Table ). OPM is an international development consultancy organisation that works to support country governments and development partners through analysis and technical assistance across the policy cycle [ 53 ]. The projects that provided evidence for this synthesis were undertaken with a range of donor, research and country government partners, in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Kenya and Ethiopia. Projects and related reports were identified for inclusion based on author knowledge of OPM work and discussion with OPM country teams, with reports then reviewed to assess whether they provided relevant information.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447.t003

CHWs’ experiences during COVID-19 were the central focus for some projects, whereas others examined community health services, health system resilience, or the COVID-19 response broadly but included information on CHWs’ roles and experiences during COVID-19. Methods varied between the research projects, but were primarily qualitative, and included interviews, focus groups and document reviews (see Table 3 ). Some studies produced multiple reports, for example through monthly updates as the pandemic progressed. In total, 25 reports based on 18 studies were used for the synthesis. One report was publicly available (a real time assessment of UNICEF’s support to COVID-19 vaccine rollout [ 54 ], but the majority were internal for specific funders or other stakeholders.

To synthesise the material, a team of two researchers (SS and KG) conducted an initial rapid reading to map the range of information available. A thematic framework (see S2 Table ) was then developed based on the research focus, knowledge of issues in the reports and other literature on CHWs’ roles and experiences with COVID-19. This framework was then adapted to clarify and add codes as reports were synthesised. Codes included roles that CHWs played during COVID-19, support provided, issues that helped or hindered CHW experience, effectiveness of service delivery, wellbeing of CHWs, and adaptation to enable continuation of service delivery. Taguette (an open-source tool for qualitative research available at https://www.taguette.org/ ) was used to import and code reports using the framework. Material under each theme was then exported for further analysis. Coding was led by one researcher (SS) and discussed among the research team (KG, JR) to support shared understanding of different themes as well as identification of new thematic areas.

Reports were not excluded on the basis of overall quality of research methods or analysis, as useful information can be obtained from reports that may otherwise have weaknesses [ 55 ]. However, reliability of report findings was considered for inclusion of specific information, for example, only drawing on reported findings with clearer underlying evidence, such as from empirical research where quotes or other evidence were sufficiently specific and detailed to be confident about interpretation. Most reports had been peer reviewed, both by senior OPM staff and external researchers, and all had some level of review from the organisations that commissioned the research.

Following initial drafting, synthesis findings were shared with a selection of researchers involved in conducting the original studies, to verify information and interpretation of their findings and so strengthen reliability of analysis. Discussion with these researchers also provided additional information from their research data or wider contextual understanding that was not included in the original project reports. This additional information was then incorporated in the analysis (where this additional information has been used in this paper, it is referenced as ‘project data’). Core OPM contacts for most projects are also authors for this article (SS, PD, GO, AK, KG). Including authors with different country contexts, professional affiliations and personal backgrounds helped to ensure that different interpretations and perspectives were considered in the analysis.

Ethics statement

All the research studies included in the synthesis ensured that participants provided informed consent and that data was confidential. Consent was verbal or written, depending on the study approach (for example, remote interviews required verbal consent) and on context-specific understanding and guidance on appropriate procedures. Formal ethical review was provided for all reports (see S1 Table ), except for two sets of rapid assessments conducted to inform government or other programming: the Intra-Action Reviews of the COVID-19 response in Ethiopia, and the rapid COVID-19 initial assessments conducted under the Maintains programme. These reports were focused on immediate feedback for programme decisions and restricted to document review and discussion with senior officials regarding health system issues; stakeholders and guidance indicated that approval was not required due to the low-risk approach and methods, restriction of interviews to areas of professional responsibility, and the focus on programme decisions.

In this section, we present findings from the different countries in line with the thematic framework developed for this synthesis, examining the roles played by CHWs in the COVID-19 response, the support they received–and gaps in this support, challenges that they experienced, and strategies used by CHWs to continue their work.

What roles have CHWs played in the COVID-19 response?

In all countries, CHWs took on new roles in the COVID-19 response. Across countries, they contributed to aspects of case identification and surveillance, such as house screening, screening of people with COVID-19 symptoms, contact tracing, or reporting potential infections to district health teams [ 11 , 29 , 56 – 58 ]. Community engagement was another key role, including education and awareness on COVID-19 [ 57 , 59 , 60 ] and in India, counselling for returnee migrants [ 58 ]. In some countries, such as India and Bangladesh, CHWs were also involved in follow-up of COVID-19 patients including providing rations to those who were isolating and in need [ 59 , 61 ] and in Bangladesh, enforcing household lockdown for people with COVID-19 as well as returnee migrants [ 59 ]. Most of the research was conducted before COVID-19 vaccine rollout, so there was limited information on CHWs involvement in vaccine delivery. However, later reports indicated that CHWs in India and Ethiopia were involved in raising awareness about COVID-19 vaccination and encouraging uptake [ 54 , 62 ], and CHWs in Ethiopia were also involved in listing target populations and delivering vaccines [ 54 ]. CHWs’ responsibilities in delivery of routine essential services also changed during COVID-19. For example, in some areas of India, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) played new roles in both antenatal services (such as blood pressure checks), because the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANMs) who would usually provide this antenatal care were unavailable, and in neonatal care (particularly first vaccinations), because of a rise in home deliveries [ 63 , 64 ].

As previously noted, the majority of CHWs in these countries are female. Reflecting existing gender-based occupational segregation in the health system, there were gender differences in assignment of COVID-19-related roles across the health workforce. In India, lower status positions are largely occupied by women, with very few women in management and leadership roles. Reflecting this, managerial, coordination and supervisory roles in COVID-19 were largely assigned to men, whereas female CHWs were primarily engaged in the more frontline activities such as screening and awareness raising [ 60 ].

Support provided to enable CHWs’ work during COVID-19

CHWs received various forms of support for their roles in the COVID-19 response, as well as for conducting their routine service delivery during COVID-19. This included support through the formal health system, from the community, and through their personal relationships.

Support from the formal health system.

Support through the formal health system included training and other guidance, personal protective equipment (PPE), financial support, and some support from managers. There were gaps in support in all these areas with consequences for CHWs’ ability to deliver services and for their well-being.

Training . Reports from most countries indicated provision of training for CHWs on services related to COVID-19, such as contact tracing and case management, and in some cases also on safe provision of routine services, including topics such as infection prevention and control and routine immunization during COVID-19 [ 29 , 65 – 67 ]. Development partners supported CHW training, including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Sierra Leone and African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF) Enterprises in Kenya [ 29 , 68 ].

To comply with physical distancing requirements and enable more rapid scale up of training, several countries conducted some training online or via mobile phones: in India, some training used zoom calls on mobile phones and the new ‘Disha’ App [ 67 ], Kenya used an application called ‘Leap’ to deliver learning content to CHWs by mobile phone [ 29 ], and Ethiopia relied on mobile-based and online training [ 69 ]. These approaches were reported to reach large numbers; for example, with 53,000 CHWs in Kenya reportedly trained via LEAP during early 2020 [ 29 ]. However, gaps in smartphone access meant these approaches could not reach all CHWs. In India, alongside use of online training, information and instructions on COVID-19 tasks were often sent by WhatsApp, but some ASHAs do not have any access to smartphones, and for many others, phones are kept by husbands [ 63 , 64 ]. There were also indications of wider gaps in training. For example, in India, some ANMs reported that they and Asha has not received training to support their work in raising awareness on COVID-19, and training had instead focused on management cadre. CHW often relied on public sources for information, such as television and WhatsApp messages [ 60 ].

PPE . CHWs across countries had insufficient PPE, with issues of quantity and quality. For example, some health assistants in Bangladesh received only three PPE sets over the first year of the pandemic, and shortages of masks and sanitiser were widely reported by ASHAs in India [ 59 , 70 ]. However, supply varied between CHWs and over time. For example, in Pakistan, some LHWs reported an absence of PPE while others reported both supplies and training on PPE use [ 56 ]. In India, initial shortages eased somewhat during later months (though with ongoing gaps for some ASHAs), and there were significant differences between cadres: ANMs in some cases received more PPE than ASHAs or AWWs [ 67 ], even though ASHAs had more contact with potential infection through their screening roles. ANMs also generally had stronger personal finances than ASHAs, and so could purchase PPE when it was not provided [ 63 , 64 ].