- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Lay summary, internet memes, social media, credibility, and persuasion, credibility and online health information, message tone, limitations, contributions and recommendations, appendix a: sample of anti- and pro-mask/memes, appendix b: anti- and pro-vaccine/memes, appendix c: sample of instrument, memes, memes, everywhere, nor any meme to trust: examining the credibility and persuasiveness of covid-19-related memes.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ben Wasike, Memes, Memes, Everywhere, nor Any Meme to Trust: Examining the Credibility and Persuasiveness of COVID-19-Related Memes, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 27, Issue 2, March 2022, zmab024, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab024

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study used an experimental design to examine the credibility and persuasiveness of COVID-19-related Internet memes. The study used a random sample of U.S. social media users (N = 1,200) with source credibility as the theoretical framework. Results indicate that memes with expert source attribution are more credible than those with nonexpert source attribution. The same applies to the persuasiveness of the memes. Memes with an objective message tone are also more credible and persuasive than those with a subjective message tone. Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the credibility of a meme and its persuasiveness. Age correlates inversely with persuasion and pro-mask/vaccine memes are more credible and persuasive than anti-mask/vaccines memes. These results have implications regarding COVID-19 messaging as well as on meme-based communication.

This study examined the credibility and persuasiveness of COVID-19-related Internet memes. This approach is important given the widespread use of social media during the pandemic and the rise of meme-based communication on social media. The study found that memes from an expert source are more credible and persuasive than those from a nonexpert source. The same applied to memes with an objective message over those with a subjective message. The credibility of a meme also improved its persuasiveness, meaning that users were more likely to like it, comment on it, and share it with others. As expected, younger people were more likely to like, share, and comments on memes. Overall, pro-mask/vaccine memes were more credible and persuasive than anti-mask/vaccines memes. These results suggest that public health campaigns may benefit by incorporating memes in their communications.

When you plant a fertile meme in my mind you literally parasitize my brain, turning it into a vehicle for the meme’s propagation in just the way that a virus may parasitize the genetic mechanism of a host cell ( Richard Dawkins, 1976 , p. 250).

In Dawkins’ conceptualization, a meme is a symbolic aspect of culture that can, as quoted above, spread via imitative replication, and may represent a variety of things ranging from tunes and ideas to pottery methods and fashion (1976). Social media-related memes, or Internet memes specifically, are a disambiguation of Dawkins’ definition of cultural memes even though they too spread virally ( Shifman, 2011 ). Internet memes as popularly known today were not only supercharged by the Internet, but the use of the term is a co-option and simplification of Dawkins’ broader and nuanced characterization of cultural memes ( Knobel & Lankshear, 2006 ; Shifman, 2014 ). Here, Internet memes represent a narrow category of amateur audiovisual material or images and graphics with or without superimposed text ( Davidson, 2009 ; Milner, 2012 ). There is robust debate about equating to or differentiating Internet memes from traditional memes ( Davidson, 2009 ; Grundlingh, 2018 ; Milner, 2012 ), but that is beyond the scope of this article. Because the current study examines Internet memes, the definition and use of the term meme in this study are limited to those consisting of images and superposed text, much like the definition used in studies such Beskow, Kumar, and Carley (2020) .

Generally, this study examines the credibility and persuasiveness of memes using source credibility as the theoretical framework. Particularly, the study seeks to find whether: (a) expert source attribution in a meme affects its credibility and persuasiveness; (b) the message tone of a meme (objective vs. subjective) affects its credibility and persuasiveness; (c) there is a correlation between the credibility of a meme and its persuasiveness and (d) there is a correlation between the age (of a user) and the credibility and persuasiveness of a meme.

This study contributes to our understanding of the persuasiveness and credibility of online phenomena in the following ways. First, and as mentioned, memes have diffused rapidly within online communication, and it is important to examine the related dynamics. By 2019, memes were second among the types of content most likely to be shared by Gen Z and Millennial Internet users. Here, 66% of this demographic reported that they were either somewhat or very likely to share memes online. Additionally, 54% of this group reported that they were likely to share memes they had created themselves ( Tankovska, 2021 , para. 1). By 2021, memes were the third most shared content in the United States among all demographics, a trend partly driven by the COVID-19 pandemic ( Enberg, 2021 , para. 2). These trends could explain why memes now spread faster and wider than any other nonmeme online content ( Beskow et al., 2020 ).

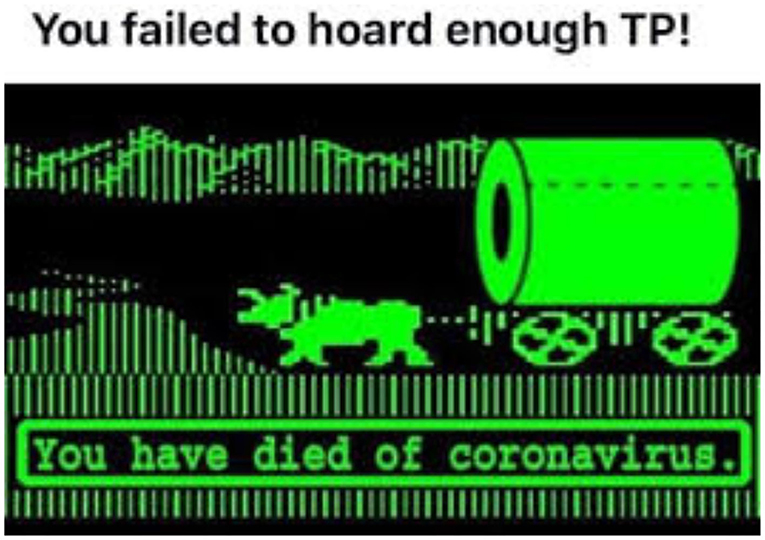

Additionally, memes emerged as unique communication tools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Users used memes to cope with pandemic-related stress ( Myrick, Nabi, & Eng, 2021 ) as well as to blunt the impact of risk messages and to gain a feeling of control during the crisis ( Flecha Ortiz, et al. 2021 ). The City Baltimore Health Department also famously used humorous memes to encourage young people to get COVID-19 vaccines and to combat misinformation ( Elwood, 2021 ). Conversely, users have used memes to spread misinformation about the coronavirus ( Spencer, 2021 , para. 2), its origins ( Glǎveanu & de Saint Laurent, 2021 ), and to spread a host of anti-vaccine falsities ( Ellis, 2021 ; Goodman & Carmichael, 2020 ).

The third reason relates to the emergence of social media as a conduit for disinformation and misinformation. This includes the fake news campaign during the 2016 U.S. presidential election ( Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017 ; Gunther, Beck, & Nisbet, 2019 ) and a variety of conspiracy movements that emerged thereafter, such as Pizzagate ( Robb, 2017 , para. 2) and QAnon ( Roose, 2021 , para. 3). During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media again proved to be fertile ground for disinformation and conspiracies. One such is the YouTube and Twitter-driven “film your hospital” campaign that alleged that hospitals were empty and not overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients ( Ahmed, López, Vidal-Alaball, & Katz, 2020 ). Another is the viral pseudo-documentary “Plandemic,” which promoted a variety of falsehoods about the coronavirus and vaccines ( Pappas, 2020 ). Similar social media-driven disinformation campaigns have questioned the origin of the coronavirus, its spread patterns, its treatments and vaccines, and the credibility of health experts ( Basch, Meleo-Erwin, Fera, Jaime, & Basch, 2021 ; Su, 2021 ). As mentioned, some among these misinformation campaigns have specifically used memes to spread similar falsehoods ( Reuters Fact Check, 2021 ; Sapienza, 2021 ; Spencer, 2021 ) and therefore it is important to examine the role of memes in such developments. Lastly, few (Internet) meme studies have taken an experimental approach to analyze effects at the time of writing (see Myrick et al., 2021 ). This study addresses this shortcoming by using a multi-stimuli experimental design to examine the effect of COVID-19-related memes.

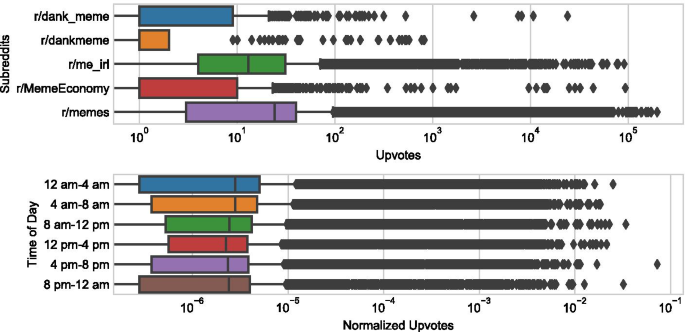

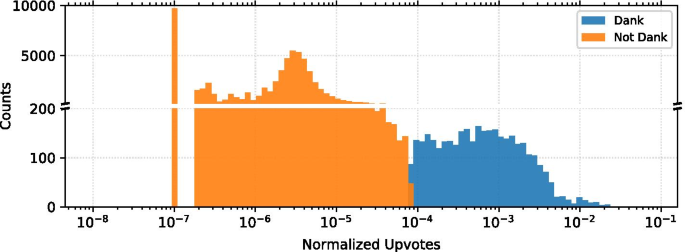

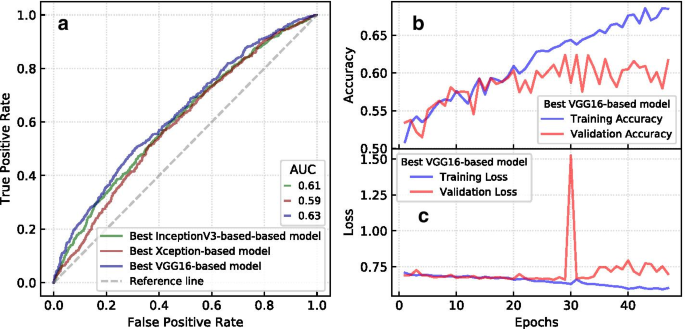

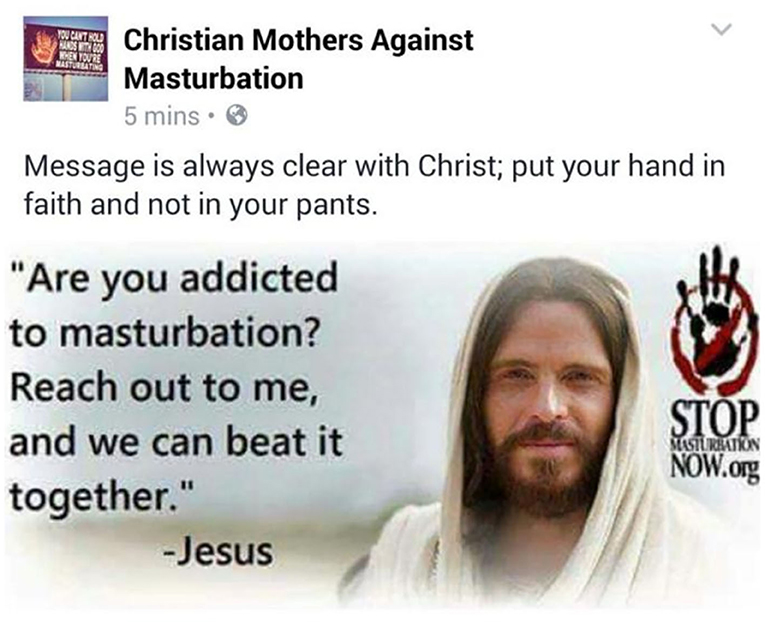

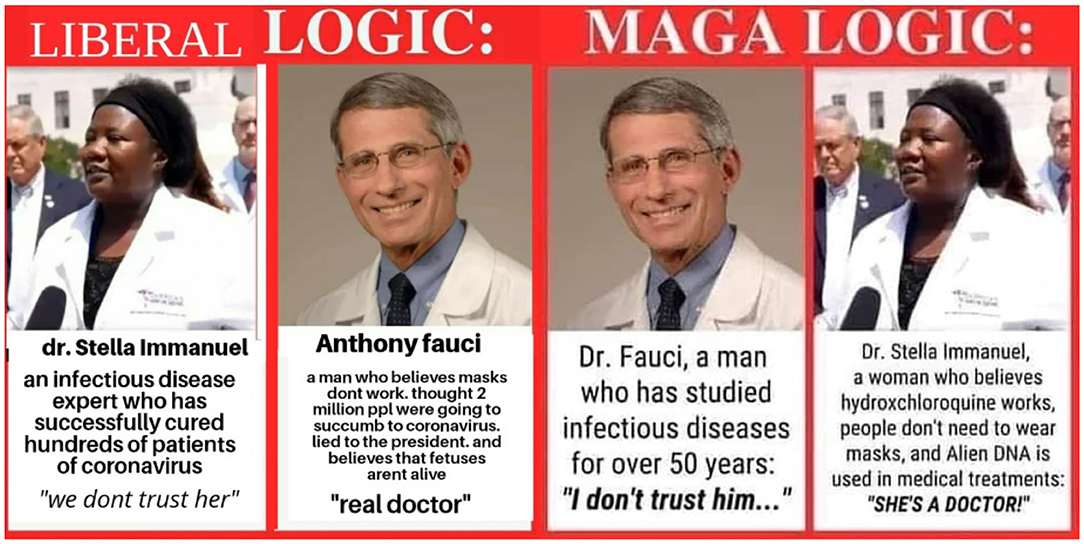

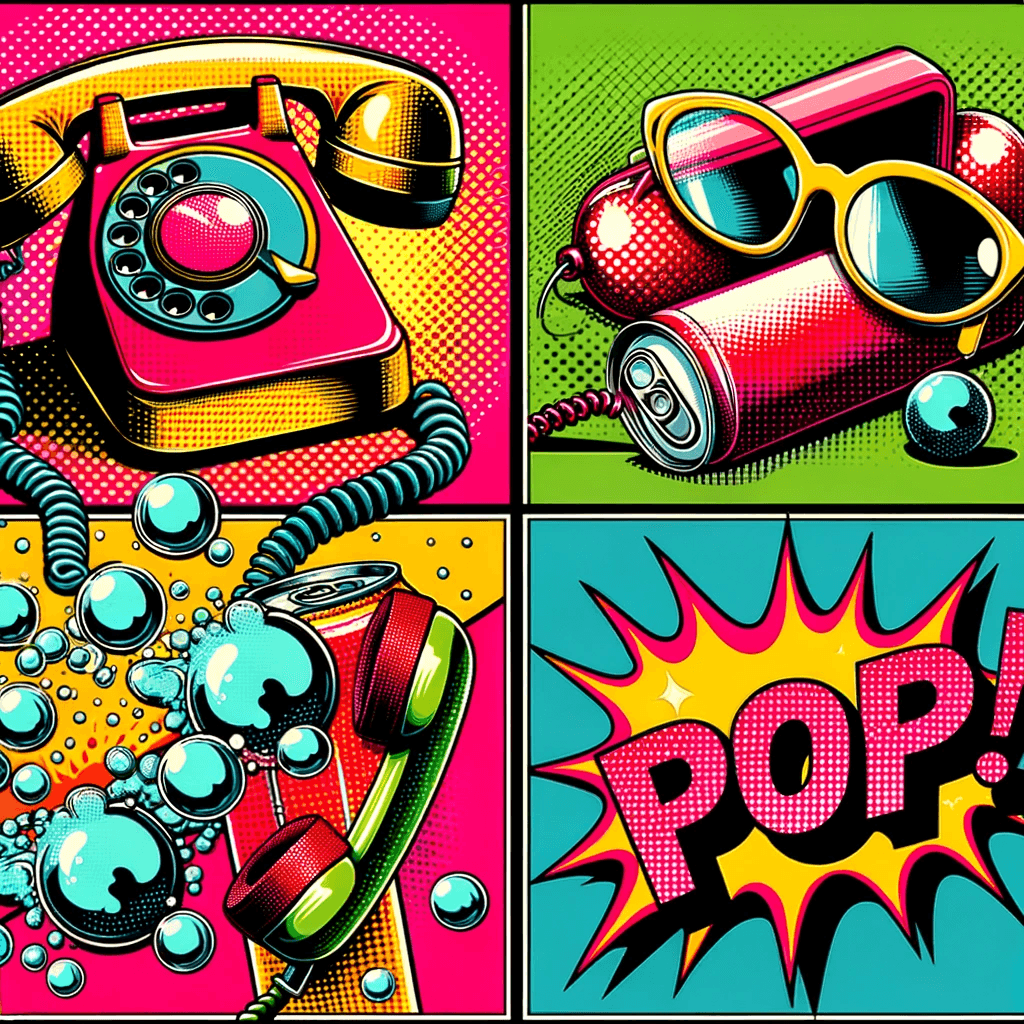

As mentioned, the word meme derives from Dawkins’ characterization of cultural artifacts that convey ideas, attire, phrases, or ideas and ways of doing things (1976). In contemporary use however, an Internet meme is “a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance, which … were created with awareness of each other, and … were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users” ( Shifman, 2014 , p. 41). In this sense, the content refers to the idea expressed by a meme. Form refers to the physical manifestation of the meme such as voice, video, image, or animation. Stance refers to the position on an issue that the meme creator intends to convey with the meme’s message. The current study examines how the content and stance of a meme affects its credibility and persuasion. See Figures 1–4 for examples of prominent Internet memes.

Tourist guy. This early meme is a digitally manipulated hoax depicting a tourist on the World Trade Center observation desk supposedly during September 11 attacks. Form: Photo.

Dancing pall bearers. Derived from a Ghanaian funeral dance, this meme is commonly used to mock people who flirt with deadly situations. Form: Video or animated GIF.

Smudge the cat. This viral photo of a Canadian cat named Smudge has been edited to include a variety of phrases as well as mash-ups with other photos. Form: Photo with text.

The Fake Lincoln quote. This obviously misleading meme is in a class of memes that use an image of famous person with an erroneous quote attributed to him/her. Form: Photo and text.

Despite the rapid diffusion of memes in contemporary online communication, there is a dearth of experiment-based research examining the effect of memes on users. Most pertinent research has taken a sense-making approach in trying to understand the dynamics of meme-based communication, while other research has taken a critical approach regarding the role of memes in communication and society. Even without experiment-based meme studies, existing research suggests such effects. For instance, scholars have discussed how meme humor may belie or lead to nefarious behavior. An example is Durham’s (2018) discussion of the ethical aspect of memes, where some viral memes started out as an exercise in casual curiosity but devolved into morbid curiosity. Such was the case with the viral photo of drowned Syrian refugee child Alan Kurdi. Users later edited the photo, not just into pro-refugee memes, but later into jocular memes that make light of his death. Meme humor may also belie sexism, misogyny, or racial prejudice, some of which may be targeted toward specific individuals or even at an entire group of people ( Dickerson, 2016 ; Drakett, Rickett, Day, & Milnes, 2018 ; Harlow, Rowlett, & Huse, 2020 ).

Not all usage of memes suggests negative effects, and memes may play a positive role. Case in point is Schonig’s (2020) analysis of aesthetic memes and how users did not just react to them as they would other viral Internet content. Here, users delved into philosophical discussions of the meme content, some of which would otherwise have seemed to be mere images or photos. This echoes Shifman’s (2011) analysis of YouTube memes where users inserted their own text onto video clips to create creative dialog. Similarly, Reddit’s MemeEconomy users creatively deploy stock market lingo to discuss meme attributes and the risks and benefits involved in “investing” in the memes. The result is an organic and active community engaged in political and cultural criticism ( Literat & van den Berg, 2019 ).

Scholars have also examined the role of memes in political dialog. This includes the use of memes to deconstruct colonialism ( Frazer & Carlson, 2017 ), using meme humor to discuss political corruption ( Bebić & Volarevic, 2018 ), and even the cult worship of authoritarian leaders ( Fang, 2020 ). Other research indicates that memes may drive protest ( Davis, Glantz, & Novak, 2016 ), engender online radicalization ( Kearney, 2019 ), influence popular perception of future technological trends ( Frommherz, 2017 ), encourage the disclosure of personal experiences ( Vickery, 2014 ), and some memes may be weaponized against institutions such as the media as is done with the popular “fake news” memes ( Smith, 2019 ). Even though the aforementioned meme-based research did not delve much into the effects of memes on users, the literature suggests that such effects are not only apparent, but likely exist and remain to be uncovered, and thus the current study.

This study examines the credibility of Internet memes as well as their persuasiveness in eliciting or changing user behavior. The key variables under study are credibility and persuasion , regarding the believability of the memes (credibility), and the likelihood of that credibility to elicit such behavior as sharing, commenting on, and liking memes (persuasion). Even though social media research generally classifies sharing, commenting, and liking as measures of engagement, research also shows that these actions have a persuasive angle. For instance, commenting and liking has been linked to increased political efficacy and political expression, even among those initially averse to political discussion ( Mutsvairo & Sirks, 2015 ; Yu, 2016 ). Influential social media users also actively persuade others, not just by posting information in general, but specifically by liking and sharing memes created by others ( Weeks et al., 2017 ). Also, comments posted in support of some online health-related PSAs have been shown to elicit real-life behavioral changes ( Shi, Messaris, & Cappella, 2014 ), as were health-related Twitter posts and related retweets ( Lauricella & Koster, 2016 ). Additionally, how a user frames a social media post affects both the credibility and persuasiveness of the message ( Wasike, 2017 ).

Research also indicates that credibility and persuasion are related ( Smith, De Houwer, & Nosek, 2013 ; Wasike, 2017 ; Westerwick, 2013 ). Persuasion is any type of message that will “cause a person or group to adopt as their own a product, person, idea, entity, or point of view that the person would otherwise not support” ( Preston, 2005 , p. 294) or “any non-coercive inducement of individual or collective choice by another” ( Barker, 2005 , p. 376). Credibility refers to how audiences deem a source to be believable and trustworthy and the extent to which they deem the message communicated to be accurate and valid ( O’Keefe, 1990 ; Rice & Atkins, 2001 ).

Like any other form of communication, social media content, including memes, may depend on its credibility and persuasion. An abundance of research supports this. For instance, attitude homophily with political-oriented Facebook messages, or how people think alike on certain issues, positively correlates with perceptions of credibility about the source of the message. This then leads to behaviors such as such as donating, volunteering, and even voting for the source, who in the said study was a political candidate ( Housholder & LaMarre, 2014 ). The current study examines how message homophily, or one’s stance on masks and vaccines affects the credibility and persuasiveness of a meme.

Research also shows that expert sources elicit more credibility than novice or nonexpert sources ( Lin, Spence, & Lachlan, 2016 ; Sohn & Choi, 2019 ). Additionally, users who perceive themselves to be more aligned with others within their social media group are more likely to share this information with others ( Sohn & Choi, 2019 ). Likewise, users who deem themselves to be like the source (of a message) based on online characteristics such as the avatar, may perceive more credibility from an accompanying message ( Spence, Lachlan, Westerman, & Spates, 2013 ). The current study also examines these variables, namely, source expertise, message homophily (as stance on mask-wearing and vaccines) and the likelihood to share memes (as persuasion).

User-generated content is a unique characteristic of Internet-based media ( Wunsch-Vincent & Vickery, 2007 ). Sharing online content such as memes falls under a class of participatory behavior called participant sharing. This is when users not only consume media, but also generate their own content and share it. Additionally, the quality of the content may affect such sharing ( Dedeoglu, 2019 ). Participant sharing is related to interactivity, another unique characteristic of social media communication. Interactivity is the ability to “share, co-create, discuss, and modify user-generated content” ( Kietzmann, Hermkens, McCarthy, & Silvestre, 2011 , p. 241). Research shows that interactivity also positively correlates with credibility ( Li & Suh, 2015 ). User-generated content and participatory sharing are uniquely important to the current study because as mentioned, users may edit photos, images, and videos to create customized memes to share with others ( Dickerson, 2016 ; Drakett et al., 2018 ; Durham, 2018 ).

Research also shows that perceptions of credibility on social media can lead to behavior such as increased social media use and increased online expression ( Neo, 2021 ). This means that as users share more of the content that they deem credible, they may become more expressive about their opinions on related issues. While the Neo study focused on political content, it is within reason to suggest that users may share more of memes they trust and even use them to express their opinions on issues such as masks and vaccines. This would be easy to do given the abundance of memes and the ability to edit memes to suit one’s stance on issues ( Enberg, 2021 ; Tankovska, 2021 ). Other research shows that users who generally perceive social media content as credible are likely to allow products placement on their group pages ( Lai & Liu, 2020 ). This suggests that accepting products placement on one’s page may engender the acceptance of other trusted content such as memes shared by others.

The credibility of health information plays a crucial role during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic given the misinformation campaigns and conspiracies regarding masks and vaccines vis-à-vis efforts to combat these campaigns with credible and persuasive messages. As I described earlier, the “film your hospital” disinformation campaign and the conspiracy-laden pseudo-documentary “Plandemic” are two such examples. While these two may have abated somewhat at the time of writing, similar campaigns have been harder to combat or even eradicate from social media ( Pazzanese, 2020 ; Rasmus, Fletcher, Newman, Brennen, & Howard, 2020).

Meanwhile, anti-mask campaigns have taken a political bent ( Aratani, 2020 ) and mask-wearing enforcement has sometimes ended in violence and death ( Bromwich, 2020 ; Elfrink, 2021 ). Vaccine hesitancy and denial have also posed problems during various COVID-19 vaccine rollout initiative. This is evident with the nonuniform positive opinions of vaccines across the world. Such opinions vary from 63% worldwide ( Johns Hopkin’s, 2021 ), 72% in the United States ( Funk & Tyson, 2021 ), 79% in Africa ( Africa CDC, 2020 ), 88.9% in China, and a low 27% in Poland ( Lazarus, 2021 ). The vaccine acceptance issue is compounded by longstanding anti-vaccine sentiment ( Hussain, Ali, Ahmed, & Hussain, 2018 ; Royal Society for Public Health, 2019 ).

With the urgency created by the COVID-19 pandemic, government agencies and non-for-profits have launched campaigns to combat this misinformation and improve vaccine acceptance by incorporating the Internet, social media, and related apps ( Harting, 2021 ; Simms, 2021 ). These efforts may well prove effective because recent scholarly studies show that social media plays a critical role in fighting misinformation and improving vaccine acceptance rates ( Kolff, Scott, & Stockwell, 2018 ; Wilson & Wiysonge, 2020 ). However, and as I discuss below, the credibility of these social media and Internet-based campaigns will play a major role in their success because credibility uniquely affects the reception of online health information.

One such uniqueness is the expertise of the source, which has been shown to affect credibility more in an online than an offline context ( Yang & Beatty, 2016 ). The credibility of online health information is also subject to the level of deliberation and verification a user engages in when reading the information. This means that activities such as checking evidence, making comparisons, and evaluating the quality of online health information affects how one perceives the credibility of that information, with younger people more likely to engage in this type of elaboration ( Liao & Fu, 2014 ). This makes age a mediating variable regarding the credibility of online health information, and research supports this.

Generally, young people use the Internet and related technologies such as apps and social media at higher rates than other age groups ( Pew, 2021 ; Vogels, 2019 ). Also, the Internet has traditionally been young people’s go-to source for online health information ( Percheski & Hargittai, 2011 ). This may explain why young people are more confident with online searches for health information and less concerned about associated risks to privacy ( Oh & Kim, 2014 ). It may further explain why young people rate the credibility of online health information the same regardless of the sensitivity of the said information, with no difference for instance, when evaluating highly sensitive (sexually transmitted disease-related) information versus less sensitive (allergy-related) information ( Kim & Syn, 2016 ). Prior use of health apps is also another age-related determinant of online health information credibility ( Cho, Lee, & Quinlan, 2015 ). Also, young people uniquely tend to rate expert sources with more (online) likes accompanying the said information as being more credible than those with less likes ( Borah & Xiao, 2018 ).

H1a: Memes with an expert source attribution will elicit higher credibility than memes without an expert source source attribution. H1b: Memes with an expert source attribution will elicit more persuasiveness than memes without an expert source attribution. H2: There is a positive correlation between the credibility of a meme and the persuasiveness of a meme. RQ1: Does the stance of a subject (pro- or anti-mask/vaccine) affect the credibility and persuasiveness of a meme? H3a: There is an inverse correlation between age and the credibility memes. H3b: There is an inverse correlation between age and the persuasiveness of a meme. RQ2: Is there a significant difference in credibility and persuasiveness between pro-mask/vaccine memes and anti-mask/vaccine memes?

In addition to examining the effect of source expertise and age on credibility and persuasion, this study also examines the effect of message tone on credibility and persuasion. Message tone is a uniquely important variable to this study. First, research shows that social media has a dark side where some users deploy uncivil content to harass, bully, and ridicule others, and often with negative outcomes for the victims ( Gearhardt & Zhang, 2014 ; Sobieraj, 2018 ; Whittaker & Kowalski, 2015 ). To do this, some users strategically repurpose objective and fact-based information into biased uncivil messages that fit a certain narrative, either to support or oppose an issue. Masullo, Lu, & Fadnis (2021) study of civil and uncivil, pro- and anti-issue online comments is a good example of such. See below for excerpts from that study (p. 3401). The study found that uncivil comments, some shown in the excerpts below, not only affected some readers emotionally, but the comments also affected the likelihood of some readers to speak out about the issues. The current study used similar messaging to develop the message tone in the memes used as stimuli for the experiment.

Excerpts of objective and subjective online comments

H4a: Memes with an objective message tone will elicit higher credibility ratings than memes with a subjective message tone. H4b: Memes with an objective message tone will elicit more persuasiveness than memes with a subjective message tone.

This study used a 2 × 2 × 2 experimental design. Factor one was source (expert vs. nonexpert), factor two was messaging tone (objective vs. subjective), and factor three was the message type in a meme (pro- or anti-mask/vaccine). All factors were within group designs. Data were collected between 14 July and 21 July 2021. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

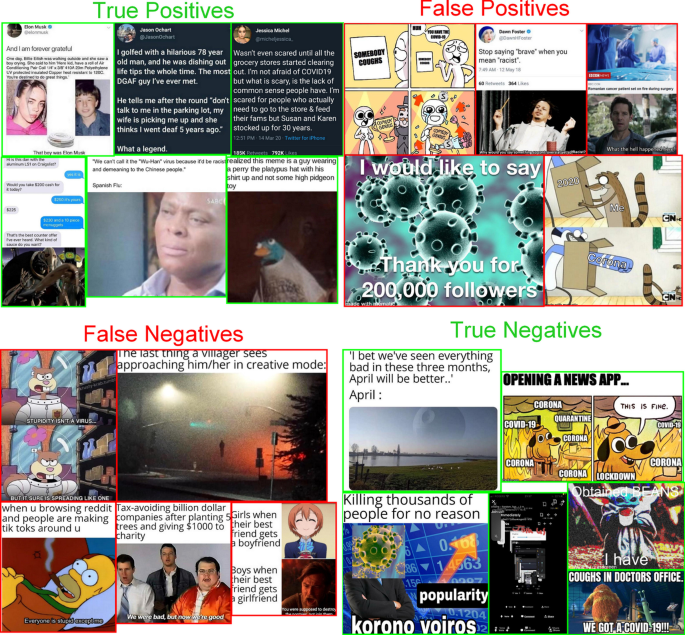

I created a set of eight memes from scratch, using Photoshop, each to represent one of the eight conditions in the experimental design. The memes were created to accurately mimic real-life memes on Twitter regarding visual style, quality, and account details such as usernames and statistics such as followers, retweets, likes, etc. See Appendices A and B for the stimuli and Table 4 for the eight treatment conditions. I chose the U.S. Centers for Disease Control as the expert source because it is a widely recognized organization in the United States. The nonexpert source was fashioned as a fictitious activist political action committee, the Patriots for Liberty PAC.

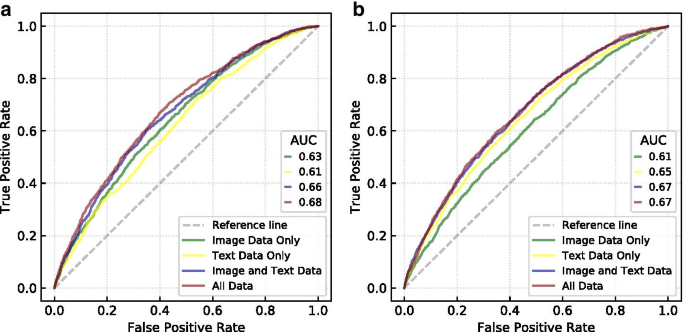

Means of Meme Credibility and Persuasiveness for the Stance/Message Combinations a

Standard deviations shown in parentheses

Repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as a covariate) for credibility with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction ( F [2.88, 3,349.02] = 292.01, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.20).

Repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as a covariate) for persuasion (with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction F [3.29, 3920.16] = 216.70, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.15).

Participants

Subjects were drawn randomly from a Qualtrics panel representative of U.S. adults regarding demographics such as age, gender, and political affiliation. All subjects were social media users. Qualtrics panels and similar others are an oft-used sampling source and their validity in data collection is proven ( Brandon, Long, Loraas, Mueller-Phillips, & Vansant, 2014 ; Gil de Zúñiga, Barnidge, & Scherman, 2017 ; Holt & Loraas, 2019 ; Kalmoe, Gubler, & Wood, 2018 ).

Instrument and procedure

After consenting to the study, subjects answered a pair of questions that queried their stance on masks and vaccines—see a sample question in the next section. Subjects then answered a series of questions measuring the variables discussed in the next section. A rating scale of 0–10 (0 = no support at all, 10 = fully support) was used. The zero in the scale was used to account for subjects who were diametrically opposed to mask-wearing and/or vaccines. See Appendix C for instrument. Subjects were emailed a link to the survey. Even though all subjects viewed all eight stimuli, the stimuli were presented one at a time and randomly to reduce order effects. Subjects viewed each stimulus and immediately an instrument before proceeding to the next stimuli and filling the accompanying instrument.

The five independent variables were expert source, message type, message orientation, subject stance (on masks and vaccines), and age. The dependent variables were credibility and persuasion.

You just saw a meme on Covid-19 vaccines from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), a federal agency responsible for public health and safety. Please indicate your response to the following statements on a scale of 0–10 where: 0 = Totally disagree and 10 = totally agree. You just saw a meme on vaccines from Patriots for Liberty, an activist political action committee. Please indicate your response to the following statements on a scale of 0–10 where: 0 = Totally disagree and 10 = totally agree.

On a scale of 0–10 where: 0 = fully opposed to and 10 = fully support, how would you characterize your support for mask-wearing in public (or Covid-19 vaccines) as a measure to control the coronavirus?

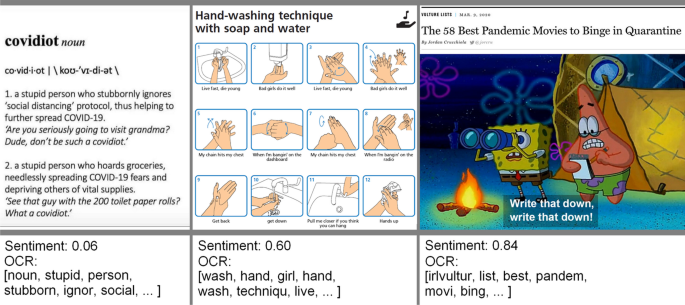

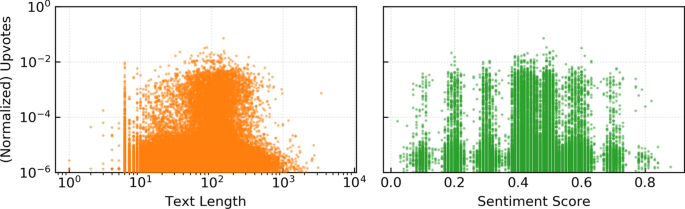

Message tone. Research indicates that online health information that makes subjective claims elicits less credibility than that which is objective ( Gao et al., 2015 ). This variable measured the effect of the objectivity or subjectivity of a meme’s message on its credibility and persuasiveness. Objective messaging included memes that made levelled claims and subjective messaging included memes that make speculatory and inflammatory claims and distorted facts (See appendices A and B for examples). I used messaging patterns similar to Masullo, Lu, & Fadnis (2021) when creating the memes used as stimuli.

Message orientation. This variable distinguished among pro- and anti-mask and pro- and anti-vaccine memes. See Table 1 and Appendices A and B for details.

Comparisons of Means of the Persuasion Parameters a

Standard deviations are shown in parentheses.

p < .001

Age . As discussed, research shows that younger people rate online and social media stimuli different from other age groups. This variable measured the effect of age on the perceptions of meme credibility and persuasiveness.

Credibility . This variable was measured by a set of eight questions derived from previous studies ( O’Keefe, 1990 ; Rice & Atkins, 2001 ; Tandoc, 2019 ; Wasike, 2017 ). Each question queried the subjects on each of the eight credibility parameters. These were sincerity, honesty, trustworthiness, expertise, effectiveness, reliability, message comprehension, and accuracy. A composite credibility score was then computed based on the mean of the responses to the eight questions.

Persuasion. This variable measured the effect of a meme on subjects regarding how it persuaded them to share it, comment on it, or post a like on it. The variable was measured by three questions derived from previous studies ( Li & Suh, 2015 ; Neo, 2021 ). See Appendix C for sample question. The three questions that asked users about their likelihood to (a) Like the meme, (b) Comment on the meme and (c) Post or retweet the meme on their social media accounts. Like credibility, this also used a 0–10 scale and a composite persuasion score was then computed based on the mean of the responses to the three questions.

Stimuli pretest

A stimulus pre-test was conducted with a nonrandom pilot sample ( N = 79) based on a set of memes depicting only mask-related messages. Subjects received an email with a Qualtrics survey link that contained the stimuli and instrument. Subjects viewed four memes that depicted respectively: an objective pro-mask meme, a subjective pro-mask meme, an objective anti-mask meme, and a subjective anti-mask meme. Exposure was done one meme at a time and in random order to avoid order effects. Subjects viewed and responded to each meme before moving to the next.

Overall, the Cronbach alphas for the reliability of the various credibility and persuasion scales ranged from 0.82–0.95. Memes with an expert source elicited higher credibility ( M = 8.16, standard deviation (SD) = 2.06) than those with a nonexpert source ( M = 4.9, SD = 3.10, p < .001, t = 7.45, d = 0.92). Expert-sourced memes also elicited more persuasion ( M = 5.39, SD = 3.18) than nonexpert sourced memes ( M = 3.75, SD = 3.36, p < .001, t = 3.47, d = 0.42). Likewise, memes with an objective message ( M = 6.60, SD = 1.93) elicited more credibility than memes with a subjective message ( M = 5.22, SD = 1.79, p < .001, t = 5.01), and were also more persuasive ( M = 4.62, SD = 2.67) than those with a subjective message ( M = 3.27, SD = 2.17, p < .001, t = 4.61).

I used G*Power to determine the appropriate sample size for the main study. G*Power is a widely used power analysis software for determining effects and sample sizes ( Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007 ; Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009 ; Lakens, 2013 ). I used the two Cohen’s d effects sizes reported above as the a priori criteria, respectively. The analysis indicated that samples sizes of either N = 36 (for credibility) or N = 47 (for persuasion) were appropriate for the paired samples tests used in this study (80% power, alpha = 0.05, two-tailed).

This study used a nationally representative random sample of U.S. social media users ( N = 1,200). The sample was 49.3% female, 49.1% male, and 1.2% nonbinary. Of all respondents, 65.6% were non-Hispanic white, 12% were non-Hispanic Black, 12.3% were Hispanic, 5% were Asian, 3.2% were Native American, and 0.6% were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders. The average age was 44.94 years.

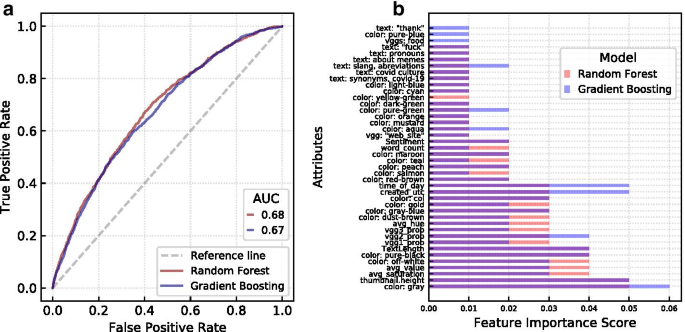

Data supported all hypotheses. Because all subjects viewed all eight same stimuli (in random order to avoid order effects), paired sample t -tests and repeated measures Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA - with stance as a covariate) were used for data analysis, an approach suitable for the within-subjects-only design used in this study. Hypothesis one predicted that memes with expert source attribution would garner more credibility as well as be more persuasive than those with a nonexpert source. Data showed that overall, memes with an expert source elicited more credibility ( M = 7.03, SD = 2.62) than those with a nonexpert source ( M = 4.91, SD = 3.05, p < .001, t = 18.87; d = 0.55). Likewise, memes with an expert source were more persuasive ( M = 5.46, SD = 3.27) than those without a nonexpert source ( M = 4.03, SD = 3.47, t = 15.02, d = 0.44). Because all expert-source memes were also pro-mask/vaccine and all nonexpert-source memes were also anti-mask/vaccine, these results also show that overall, pro-mask/vaccine memes were more credible and persuasive than anti-mask/vaccine memes. Additionally, because the persuasion variable was measured by three questions (about liking, commenting, and sharing memes), it is worth examining the differences among the three parameters (See Table 1 ).

Hypothesis two predicted a positive correlation between the credibility and persuasion of the memes, and data supported this prediction ( r = 0.78, p < .001). Because this correlation refers to all memes in general regardless of their message on masks and vaccines, it is insightful to consider the stance (on masks and vaccines) of the subjects viewing the memes. Therefore, RQ1 queried about the correlation between a subject’s stance (on masks/vaccines) and the credibility and persuasion of the memes, respectively. To answer this research question, the stance (on masks and vaccines) variable was split into two categories—low support for masks/vaccines (5 and below on the 0–10 scale) and high support for masks/vaccines. The correlation between credibility and persuasion among the high mask/vaccines support group remained steady ( r = 0.79, p < .001) but that for the low mask/vaccines support group declined ( r = 0.62, p < .001).

Even then, these results still reflect all meme types, so further analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between stance and the eight combinations of memes. This analysis was done for credibility ( Table 2 ) and persuasion ( Table 3 ). As the tables indicate, the only strong correlations to emerge were between stance and the pro-mask/vaccines memes. Additionally, there were significant correlations among pro-mask/vaccine memes as were between anti-mask/vaccine memes. The fact that there were more positive correlations among the anti- and pro-mask/vaccine memes for persuasion may be because one of the persuasion scale questions asked about commenting on memes without specifying whether the comments were critical or laudatory. It is possible that pro-vaccine subjects may have intended to post negative comments on anti-mask/vaccine memes and vice versa, and hence the correlation.

Correlations Between Stance and the Credibility of Memes

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Correlations Between Stance and the Persuasiveness of Memes

Hypothesis three predicted an inverse correlation between age and the credibility of a meme and the same pattern between age and the persuasiveness of a meme. This hypothesis was partially supported. There was no correlation between age and credibility, but there was a moderate inverse correlation between age and persuasion ( r = −0.18, p < .001), meaning that younger subjects were more likely to like, comment on, and share memes than older subjects. RQ2 queried the differences in credibility and persuasiveness between pro-mask/vaccines memes and anti-mask/vaccines memes. Overall, pro-mask/vaccines memes scored higher in credibility ( M = 7.03, SD = 2.62) than anti-mask/vaccine memes ( M = 4.91, SD = 3.05, p < .001, t = 18.87, d = 0.55). They also scored higher in persuasion ( M = 5.46, SD = 3.27,) than anti-mask/vaccines memes ( M = 4.03, SD = 3.47, p < 0.001, t = 15.02. d = 0.44) (See Table 4 for details).

Overall, memes with an objective tone were more credible ( M = 6.06, SD = 2.12) than those with a subjective tone ( M = 5.87, SD = 2.24, p < .001, t = 5.0, d = 0.16), regardless of whether they displayed a pro- or anti-mask/vaccine message. Objective-toned memes were also more persuasive ( M = 4.83, SD = 3.0) than subjective-toned memes ( M = 4.66, SD = 3.04, p < .001, t = 5.35, d = 0.16), regardless of their pro- or anti-mask/vaccine message, thus supporting hypothesis four. A nuanced examination indicates larger differences when a meme’s pro- or anti-mask/vaccine message is considered. A repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as the covariate) with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction ( F [2.88, 3,349.02] = 292.01, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.20) returned statistically significant differences among the four possible means for objective (pro- and anti-mask/vaccine) and subjective (pro and anti-mask/vaccine) messaging, with objective pro-mask/vaccine memes scoring the highest credibility ( M = 7.07, SD = 2.68). Memes with a subjective anti-mask/vaccine message earned the lowest credibility ( M = 4.75, SD = 3.31).

The same results emerged for the persuasiveness of the memes. A repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as the covariate) with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction ( F [3.29, 3920.16] = 216.70, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.15) returned significant differences among the four persuasion means. Here, pro-mask/vaccine memes with an objective tone were the most persuasive ( M = 5.49, SD = 3.35, F [1.46, 1737.87] = 188.35, p < .001), while memes with a subjective anti-mask/vaccine message were the least persuasive ( M = 3.89, SD = 3.62). Because each of the credibility and persuasion means in these ANCOVA results combine anti- and pro-mask/vaccine messages, Table 4 shows nuanced results for the eight combinations of experimental conditions for credibility and persuasion for all pro- and anti-mask/vaccines memes.

This study examined COVID-19-related memes regarding their credibility and persuasiveness based on pro- and anti-mask/vaccine messages. A major contribution this study makes to literature is that it takes an experimental approach to examine meme-based communication. First, the experimental approach identified when, where, and how the memes affected credibility and persuasion, and the extent and direction of these effects. Also, as I discussed earlier, few if any Internet meme-communication studies have yet taken an experimental approach. Most existing research is largely descriptive and/or analytical. An experimental approach is a methodological contribution to pertinent research. Also, this study is timely given that data collection occurred during a confluence of the rapid diffusion of meme-based communication and the COVID-19 pandemic. This is opportune given the roles that social media in general, and meme-based communication have played among issues such as vaccine promotion campaigns, vaccine and COVID-19 misinformation campaigns, and the campaigns aimed at combatting this misinformation during the pandemic.

The results indicate that like other social media content, memes do have a discernible effect on users. Additionally, there are discernible patterns within meme-based communication, despite the seemingly ubiquitous and rapid diffusion of memes in contemporary communication. One such pattern is that the source of a meme determines how credible users view the meme and how likely they are to like, comment on, or share it with others. Memes from expert sources are more likely to be believed and shared. This matches existing research on social media credibility and content sharing ( Lin et al., 2016 ; Sohn & Choi, 2019 ; Spence et al., 2013 ), and specifically research on online health information ( Yang & Beatty, 2016 ). Similarly, age correlates inversely with the likelihood to like, comment on, and share memes, a reflection of the unique age-related communication patterns in social media communication in general ( Pew, 2021 ; Vogels, 2019 ) and online health communication specifically ( Borah & Xiao, 2018 ; Cho et al., 2015 ; Liao & Fu, 2014 ; Oh & Kim, 2014 ).

This expert source and age-related findings have unique policy implications. At the time of writing, young people and young adults are among the demographics least likely to get Covid-19 vaccines ( Baack, 2021 ; Thigpen & Funk, 2020 ). Meanwhile, research indicates that online sources are the go-to venues for health information among young people ( Pew, 2021 ; Vogels, 2019 ). Young people also do more information verification (via comparisons and evidence-checking) as a means of determining the credibility of the online health information ( Liao & Fu, 2014 ) than other demographic groups do. Additionally, young people are more adept at navigating the Internet ( Oh & Kim, 2014 ) and are more likely to use social media metrics to determine the credibility of online information ( Borah & Xiao, 2018 ). As discussed, memes provide simple and easily comprehensible visual messages, and this fact alone may enhance their credibility regardless of the target demographic ( Harvey, 2020 ; Sadoski & Paivio, 2013 ; Trethewey et al., 2020 ). The combination of these facts suggests that meme-based social media campaigns from credible sources such as the CDC may be an effective way to reach vaccine-wary young people.

It worth mentioning that this study used a unidimensional credibility scale. Other scholars have used similar, but multidimensional scales that differentiate the credibility of the author and that of the information itself ( Yin & Zhang, 2020 ; Xu et al., 2021 ). To account for this nuance, I ran further analysis with a two-dimensional version of the original scale to test for credibility parameters based on the author-only parameters (sincerity, honesty, trustworthiness, and expertise) and information-only parameters (reliability, effectiveness, comprehension, and accuracy). Repeated mesures ANCOVA (with stance as a covariate) returned similar results as those of the unidimensional scale for the credibility of pro- and anti-mask/vaccine memes. Those memes with an expert source attribution still elicited more author- and information-only credibility than nonexpert sourced memes. See Tables 4 and 5 for comparisons.

Means of Author- and Information-Only Credibility a

Repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as a covariate) for author-only credibility with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction ( F [3.0, 3351.40] = 275.43, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.19).

Repeated measures ANCOVA (using stance as a covariate) for information-only credibility with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction ( F [3.05, 3594.60] = 276.80, p < .001; η p 2 = 0.19).

Another important finding has to do with the objective versus subjective tone of meme messages. The study found that objective-toned memes were more credible and persuasive than subjective-toned memes. This was true among both pro- and anti-mask memes, with objective pro-mask memes being the most credible and subjective anti-vaccine memes being the least credible. This is noteworthy in the context of social media communication and the accompanying incivility and toxicity ( Anderson & Huntington, 2017 ; Kosmidis, 2020 ; Rheault et al., 2019 ). Also, the literature discussed earlier shows that meme-based communication may engender negative communication. For instance, humorous memes but with subjective messages may belie negativity ( Dickerson, 2016 ; Durham’s, 2018 ; Harlow et al., 2020 ). Memes may also promote prejudice and radicalization ( Drakett et al., 2018 ; Kearney, 2019 ) and even be weaponized against institutions such as the media ( Smith, 2019 ). The objective versus subjective dynamic is a unique finding given that the mask-wearing debate has exacerbated the toxicity and incivility of social media communication ( Pascual-Ferrá, Alperstein, Barnett, & Rimal, 2021 ). The fact that subjects placed higher credibility on objective memes rather than subjective memes and were more likely to share objective memes bodes well for the promotion of civil discourse on social media, especially regarding such contentious issues as mask-wearing and COVID-19 vaccines.

As with any research endeavor, this study comes with limitations. One limitation is that the study uses data from a self-reported survey, albeit from a random and representative sample. As with any survey-based study, issues of desirability responses must be considered, especially when querying subjects about contentious issues such as mask-wearing and COVID-19 vaccines. However, the high reliability scores for the survey scales used in the study should mitigate this concern. Additionally, the successful stimuli check improves the validity of the results. Another consideration is that the subjects were examined in an experimental situation and were exposed only to one meme at a time. On social media users may view several memes as well as other content such as posts, comments, and multimedia. This limitation is closely related to those which are natural to most single-scenario experimental studies like this one. Unique and unrecognized conditions such as heightened emotions, differences among subjects, and different environments may impact data validity and affect the generalization of the results ( Collett & Childs, 2011 ; Ferrara & Yang, 2015 ; Funke, 1998 ; Jackson & Jacobs, 1983 ). Additionally, the pairs of contrasting memes were visually identical expect for the textual information. If, during random exposure, a savvy subject viewed the same images sequentially, they could have guessed the hypotheses, and such an occurrence increases the chances of desirability responses. The data should be considered with this issue in mind.

The also study compared the CDC, a well-known federal agency, to a fictional PAC. Even though the CDC has registered low approval ratings lately ( Jones, 2021a , 2021b ), it still carries the name recognition that the nonexpert source used here does not. Therefore, the results reported in this study should be interpreted within this lens. Important also is that the study did not consider ideology and its interactions with the variables examined, given the fluidity and uncertainty of COVID-19-related research during data collection. Recent research suggests an ideological impact on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy ( Bhochhibhoya, Thapaliya, Sharma Ghimire, & Wharton, 2021 ; Galston, 2021 , para. 4; Haytko & Taillon, 2021 ), and future research may examine the role of ideology in the credibility and persuasiveness of pro- and anti-mask/vaccine memes.

Despite these limitations, the study makes practical and theoretical contributions. A practical contribution has to do with systematically showing that memes play a crucial role in public health communication and campaigns, and specifically regarding mask-wearing and vaccine hesitancy. Data showed that expert-sourced memes with objective messages are best poised to improve mask-wearing and vaccine acceptance. As I mentioned, the CDC and other public health agencies may be well served by incorporating meme-based communication when promoting mask-wearing and Covid-19 vaccines. Data suggests that this may uniquely improve messaging targeted towards young people who are currently one of the most COVID-19 vaccine-adverse demographic groups.

The study also makes theoretical contributions. As I mentioned, it enhances meme-based communication by taking an experimental approach using a multi-stimuli design. In the future, scholars may adopt and improve on this design. The study also examined a unique set of variables, and the results and interactions reported here not only add to knowledge, but scholars may also retest and improve on the variables. Because this study examined phenomena related to the COVID-19 pandemic, it also adds to crisis communication research generally and specifically to crisis communication research vis-à-vis meme-based communication. Lastly, by examining message tone, the study adds to previous works that have examined hostility and incivility in online communication.

This study was funded by the Henry W. Hauser and Margaret H. Hauser Endowment, Department of Communication, College of Liberal Arts, at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Africa CDC . ( 2020 ). Majority of Africans would take a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine . Retrieved from https://africacdc.org/news-item/majority-of-africans-would-take-a-safe-and-effective-covid-19-vaccine/

Ahmed W. , López S. F. , Vidal-Alaball J. , Katz M. S. ( 2020 ). COVID-19 and the “Film your hospital” conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data . Journal of Medical Internet Research , 22 ( 10 ), e22374 . https://doi.org/10.2196/22374

Google Scholar

Allcott H. , Gentzkow M. ( 2017 ). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election . Journal of Economic Perspectives , 31 ( 2 ), 211 – 236 . https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Alrubaian M. , Al‐Qurishi M. , Al‐Rakhami M. , Hassan M. M. , Alamri A. ( 2017 ). Reputation‐based credibility analysis of Twitter social network users . Concurrency and Computation , 29 ( 7 ), e3873 . https://doi.org/10.1002/cpe.3873

Anderson A. A. , Huntington H. E. ( 2017 ). Social media, science, and attack discourse: How twitter discussions of climate change use sarcasm and incivility . Science Communication , 39 ( 5 ), 598 – 620 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547017735113

Aratani L. ( 2020 , June 29). How did face masks become a political issue in America? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/29/face-masks-us-politics-coronavirus

Baack B. ( 2021 ). Vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18–39 years—United States, March–May 2021 . MMWR , 70 (25), 928 – 933 . http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2external icon .

Basch C. H. , Meleo-Erwin Z. , Fera J. , Jaime C. , Basch C. E. ( 2021 ). A global pandemic in the time of viral memes: COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and disinformation on TikTok . Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics , 17 ( 8 ), 2373 – 2377 . https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1894896

Bebić D. , Volarevic M. ( 2018 ). Do not mess with a meme: The use of viral content in communicating politics . Communication & Society , 31 ( 3 ), 43 – 56 .

Beskow D. , Kumar S. , Carley K. ( 2020 ). The evolution of political memes: Detecting and characterizing internet memes with multi-modal deep learning . Information Processing & Management , 57 ( 2 ), 102170 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102170

Bhochhibhoya A. , Branscum P. , Thapaliya R. , Sharma Ghimire P. , Wharton H. ( 2021 ). Applying the health belief model for investigating the impact of political affiliation on covid-19 vaccine uptake . American Journal of Health Education , 52 ( 5 ), 241 – 250 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2021.1955231

Borah P. , Xiao X. ( 2018 ). The importance of ‘likes’: The interplay of message framing, source, and social endorsement on credibility perceptions of health information on Facebook . Journal of Health Communication , 23 ( 4 ), 399 – 411 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2018.1455770

Bromwich J. E. ( 2020 , June 30). Fighting over masks in public is the new American pastime. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/30/style/mask-america-freedom-coronavirus.html

Brandon D. , Long J. , Loraas T. , Mueller-Phillips J. , Vansant B. ( 2014 ). Online instrument delivery and participant recruitment services: Emerging opportunities for behavioral accounting Research . Behavioral Research in Accounting , 26 ( 1 ), 1 – 23 . https://doi.org/10.2308/bria-50651

Chang W.-L. , Chen Y.-P. ( 2019 ). Way too sentimental? A credible model for online reviews . Information Systems Frontiers , 21 ( 2 ), 453 – 468 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9757-z

Cho J. , Lee H. , Quinlan M. ( 2015 ). Complementary relationships between traditional media and health apps among American college students . Journal of American College Health , 63 ( 4 ), 248 – 257 . https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1015025

Collett J. L. , Childs E. ( 2011 ). Minding the gap: Meaning, affect, and the potential shortcomings of vignettes . Social Science Research , 40 ( 2 ), 513 – 522 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.08.008

Barker D. C. ( 2005 ). Values, frames, and persuasion in presidential nomination campaigns . Political Behavior , 27 ( 4 ), 375 – 394 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-8145-4

Davidson P. ( 2009 ). The language of internet memes. In Mandiberg M. (Ed.), The social media reader (pp. 120 – 134 ). New York, NY : New York University Press . https://hdl-handle-net.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/2027/heb.31970

Google Preview

Davis C. , Glantz M. , Novak D. ( 2016 ). “You can’t run your SUV on cute. let’s go!”: Internet memes as delegitimizing discourse . Environmental Communication , 10 ( 1 ), 62 – 83 . https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.991411

Dawkins R. ( 1976 ). The selfish gene . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Dedeoglu B. ( 2019 ). Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on social media?: The moderating role of gender . International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , 31 ( 1 ), 513 – 534 . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0691

De Zúñiga H. , Barnidge M. , Scherman A. ( 2017 ). Social media social capital, offline social capital, and citizenship: Exploring asymmetrical social capital effects . Political Communication , 34 ( 1 ), 44 – 68 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1227000

Dickerson N. ( 2016 ). Constructing the Digitalized sporting body: Black and white masculinity in NBA/NHL internet memes . Communication and Sport , 4 ( 3 ), 303 – 330 . https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479515584045

Drakett J. , Rickett B. , Day K. , Milnes K. ( 2018 ). Old jokes, new media—Online sexism and constructions of gender in Internet memes . Feminism & Psychology , 28 ( 1 ), 109 – 127 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517727560

Durham M. ( 2018 ). Resignifying Alan Kurdi: News photographs, memes, and the ethics of embodied vulnerability . Critical Studies in Media Communication , 35 ( 3 ), 240 – 258 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1408958

Elfrink T. ( 2021 , March 1). Man shot security guard at high school basketball game during argument over wearing mask. The Washington Post . Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/03/01/martinus-mitchum-tulane-mask-shooting/

Ellis M. ( 2021 , September 25). ‘Pureblood’: Anti-vax TikTokers push new meme to promote COVID vaccine misinformation. Raw Story . Retrieved from https://www.rawstory.com/anti-vax-pureblood/

Elwood K. ( 2021 , August 13). Yes, Debra, the Baltimore City Health Department is using memes to promote vaccinations. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/08/13/baltimore-health-department-memes-covid/

Enberg J. ( 2021 , January 25). To meme or not to meme? A marketer’s guide to memetic media in 2021 and beyond. Insider Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.emarketer.com/content/to-meme-or-not-to-meme#page-report

Fang K. ( 2020 ). Turning a communist party leader into an internet meme: the political and apolitical aspects of China’s toad worship culture . Information, Communication & Society , 23 ( 1 ), 38 – 58 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1485722

Faul F. , Erdfelder E. , Buchner A. , Lang A.-G. ( 2009 ). Statistical power analyses using GPower 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses . Behavior Research Methods , 41 ( 4 ), 1149 – 1160 . https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Faul F. , Erdfelder E. , Lang A.-G. , Buchner A. ( 2007 ). GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences . Behavior Research Methods , 39 ( 2 ), 175 – 191 . https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Ferrara E. , Yang Z. ( 2015 ). Measuring emotional contagion in social media . PloS One , 10 ( 11 ), e0142390 – e0142390 . https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142390

Flecha Ortiz J. A. , Santos Corrada M. A. , Lopez E. , Dones V. ( 2021 ). Analysis of the use of memes as an exponent of collective coping during COVID-19 in Puerto Rico . Media International Australia , 178 ( 1 ), 168 – 181 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20966379

Frazer R. , Carlson B. ( 2017 ). Indigenous memes and the invention of a people . Social Media + Society , 3 ( 4 ), 205630511773899 . https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117738993

Frommherz G. ( 2017 ). Meme wars: Visual communication in popular transhumanism . The International Journal of the Image , 8 ( 4 ), 1 – 19 . https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v08i04/1-19

Funk C. , Tyson A. ( 2021 , March 5). Growing share of Americans say they plan to get a Covid-19 vaccine— or already have. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/

Funke J. ( 1998 ). Computer-based testing and training with scenarios from complex problem-solving research: Advantages and disadvantages . International Journal of Selection and Assessment , 6 ( 2 ), 90 – 96 . https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00077

Galston W. A. ( 2021 , October 1). For Covid-19 vaccinations, party affiliation matters more than race and ethnicity . Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/10/01/for-covid-19-vaccinations-party-affiliation-matters-more-than-race-and-ethnicity/

Gao Q. , Tian Y. , Tu M. ( 2015 ). Exploring factors influencing Chinese user’s perceived credibility of health and safety information on Weibo . Computers in Human Behavior , 45 , 21 – 31 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.071

Gearhart S. , Zhang W. ( 2014 ). Gay bullying and online opinion expression: Testing spiral of silence in the social media environment . Social Science Computer Review , 32 ( 1 ), 18 – 36 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313504261

Glǎveanu V. P. , de Saint Laurent C. ( 2021 ). Social media responses to the pandemic: What makes a coronavirus meme creative . Frontiers in Psychology , 12 , 569987 – 569987 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.569987

Goodman J. , Carmichael F. ( 2020 , November 29). Covid-19: What’s the harm of ‘funny’ anti-vaccine memes? BBC . Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/55101238

Grundlingh L. ( 2018 ). Memes as speech acts . Social Semiotics , 28 ( 2 ), 147 – 168 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2017.1303020

Gunther R. , Beck P. A. , Nisbet E. C. ( 2019 ). “Fake news” and the defection of 2012 Obama voters in the 2016 presidential election . Electoral Studies , 61 , 1 – 8 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.03.006

Harlow S. , Rowlett J. , Huse L. ( 2020 ). ‘ Kim Davis be like … ’: a feminist critique of gender humor in online political memes . Information, Communication & Society , 23 ( 7 ), 1057 – 1073 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1550524

Harting C. ( 2021 , April 9). What can we do to reduce vaccine hesitancy? Columbia News. Retrieved from https://news.columbia.edu/news/covid-vaccine-hesitancy-project

Harvey A. ( 2020 ). Medical memes . BMJ , 368 , m531–m531 . https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m531

Haytko Mai, E. , Taillon B. J. ( 2021 ). COVID-19 information: Does political affiliation impact consumer perceptions of trust in the source and intent to comply? Health Marketing Quarterly , 38 ( 2–3 ), 98 – 115 . https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2021.1986996

Holt T. , Loraas T. ( 2019 ). Using Qualtrics panels to source external auditors: A replication study . The Journal of Information Systems , 33 ( 1 ), 29 – 41 . https://doi.org/10.2308/isys-51986

Housholder E. , LaMarre H. ( 2014 ). Facebook politics: Toward a process model for achieving political source credibility through social media . Journal of Information Technology & Politics , 11 ( 4 ), 368 – 382 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.951753

Hu S. , Kumar A. , Al-Turjman F. , Gupta S. , Seth S. , Shubham . ( 2020 ). Reviewer credibility and sentiment analysis based user profile modelling for online product recommendation . IEEE , 8 , 26172 – 26189 . https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2971087

Hussain A. , Ali S. , Ahmed M. , Hussain S. ( 2018 ). The anti-vaccination movement: A regression in modern medicine . Cureus , 10 ( 7 ), e2919 . https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2919

Jackson S. , Jacobs S. ( 1983 ). Generalizing about messages: Suggestions for design and analysis of experiments . Human Communication Research , 9 ( 2 ), 169 – 191 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1983.tb00691.x

Hopkins Johns . ( 2021 , Jan. 24). Covid-19 vaccine acceptance falling globally and in the U.S., survey finds . Retrieved from https://www.jhsph.edu/news/news-releases/2021/covid-19-vaccine-acceptance-falling-globally-and-in-the-us-survey-finds.html

Jones J. J. ( 2021a , September 7). CDC communication ratings mixed during pandemic. Gallup . Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/353204/cdc-communication-ratings-mixed-throughout-pandemic.aspx

Jones J. J. ( 2021b , September 7). Americans' ratings of CDC communication turn negative. Gallup . Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/354566/americans-ratings-cdc-communication-turn-negative.aspx

Kalmoe N. , Gubler J. , Wood D. ( 2018 ). Toward conflict or compromise? How violent metaphors polarize partisan issue attitudes . Political Communication , 35 ( 3 ), 333 – 352 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1341965

Kearney R. ( 2019 ). Meme frameworks: A semiotic perspective on internet memes . Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy , 4 ( 2 ), 82 – 89 . https://doi.org/10.1163/23644583-00401013

Kietzmann J. , Hermkens K. , McCarthy I. , Silvestre B. ( 2011 ). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media . Business Horizons , 54 ( 3 ), 241 – 251 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005

Kim S.U. , Syn S.Y. ( 2016 ). Credibility and usefulness of health information on Facebook: A survey study with U.S. college students . Information Research , 21 ( 4 ). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper727.html

Klawitter E. , Hargittai E. ( 2018 ). Shortcuts to well-being? Evaluating the credibility of online health information through multiple complementary heuristics . Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media , 62 ( 2 ), 251 – 268 . https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2018.1451863

Knobel M. , Lankshear C. ( 2006 ). Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In Meyers R. A. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of complexity and systems science . New York, NY : Springer .

Kolff C. A. , Scott V. P. , Stockwell M. S. ( 2018 ). The use of technology to promote vaccination: A social ecological model based framework . Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics , 14 ( 7 ), 1636 – 1646 . https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1477458

Kosmidis S. , Theocharis Y. ( 2020 ). Can social media incivility induce enthusiasm? Public Opinion Quarterly , 84(Suppl 1) , 284 – 308 . https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa014

Lai I. , Liu Y. ( 2020 ). The effects of content likeability, content credibility, and social media engagement on users’ acceptance of product placement in mobile social networks . Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research , 15 ( 3 ), 1 – 19 . https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762020000300102

Lakens D. ( 2013 ). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t -tests and ANOVAs . Frontiers in Psychology , 4 , 1 – 12 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

Lauricella S. , Koster K. ( 2016 ). Refueling" athletes: Social media's influence on the consumption of chocolate milk as a recovery beverage . American Communication Journal , 18 ( 1 ), 15 – 29 .

Lazarus J. V. ( 2021 ). A global survey of potential acceptance of a Covid-19 vaccine . Nature Medicine , 27 , 225 – 228 . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

Li R. , Suh A. ( 2015 ). Factors influencing information credibility on social media platforms: evidence from Facebook Pages . Procedia Computer Science , 72 , 314 – 328 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.12.146

Liao Q. , Fu W. ( 2014 ). Age differences in credibility judgments of online health information . ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction , 21 ( 1 ), 1 – 23 . https://doi.org/10.1145/2534410

Lin X. , Spence P. , Lachlan K. ( 2016 ). Social media and credibility indicators: The effect of influence cues . Computers in Human Behavior , 63 , 264 – 271 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.002

Literat I. , van den Berg S. ( 2019 ). Buy memes low, sell memes high: vernacular criticism and collective negotiations of value on Reddit’s MemeEconomy . Information, Communication & Society , 22 ( 2 ), 232 – 249 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1366540

Masullo G.M. , Lu S. , Fadnis D. ( 2021 ). Does online incivility cancel out the spiral of silence? A moderated mediation model of willingness to speak out . New Media & Society , 23 ( 11 ), 3391 – 3414 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820954194

Milner R. M. ( 2012 ). The world made meme: Discourse and identity in participatory media Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence.

Mutsvairo B. , Sirks L.-A. ( 2015 ). Examining the contribution of social media in reinforcing political participation in Zimbabwe . Journal of African Media Studies , 7 ( 3 ), 329 – 344 . https://doi.org/10.1386/jams.7.3.329_1

Myrick J. G. , Nabi R. L. , Eng N. J. ( 2021 ). Consuming memes during the COVID pandemic: Effects of memes and meme type on COVID-related stress and coping efficacy . Psychology of Popular Media . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000371

Neo R. L. ( 2021 ). Linking perceived political network homogeneity with political social media use via perceived social media news credibility . Journal of Information Technology & Politics , 18 ( 3 ), 355 – 369 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2021.1881016

Oh S. , Kim S. ( 2014 ). College students' use of social media for health in the USA and Korea . Information Research , 19 ( 4 ). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper727.html

O'Keefe D. J. ( 1990 ). Persuasion: Theory and research . London : Sage Publications .

Pappas S. ( 2020 , May 13). Debunking the most dangerous claims of ‘Plandemic.’ Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/debunking-plandemic-coronavirus-claims.html

Pascual-Ferrá P. , Alperstein N. , Barnett D. J. , Rimal R. N. ( 2021 ). Toxicity and verbal aggression on social media: Polarized discourse on wearing face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic . Big Data & Society , 8 ( 1 ). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211023533

Pazzanese C. ( 2020 , May 8). Battling the ‘pandemic of misinformation.’ The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/05/social-media-used-to-spread-create-covid-19-falsehoods/

Percheski C. , Hargittai E. ( 2011 ). Health information-seeking in the digital age . Journal of American College Health , 59 ( 5 ), 379 – 386 . https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.513406

Pew . ( 2021 , April 7). Internet/broadband fact sheet . Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/?menuItem=9a15d0d3-3bff-4e9e-a329-6e328bc7bcce

Preston P. ( 2005 ). Persuasion: What to say, how to be . Journal of Healthcare Management , 50 ( 5 ), 294 – 296 . https://doi.org/10.1097/00115514-200509000-00004

Rains S. , Karmikel C. ( 2009 ). Health information-seeking and perceptions of website credibility: Examining Web-use orientation, message characteristics, and structural features of websites . Computers in Human Behavior , 25 ( 2 ), 544 – 553 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.11.005

Rasmus K. N. , Fletcher R. , Newman J. , Brennen J. S. , Howard P. N. ( 2020 , April 15). Navigating the ‘infodemic’: how people in six countries access and rate news and information about coronavirus. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Navigating-the-Coronavirus-infodemic.pdf

Reuters Fact Check . ( 2021 August 10). Fact check-memes comparing being vaccinated and being unvaccinated are missing context. Reuters . Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/factcheck-covid-vaccinated-unvaccinated/fact-check-memes-comparing-being-vaccinated-and-being-unvaccinated-are-missing-context-idUSL1N2PH1DE

Rheault L. , Rayment E. , Musulan A. ( 2019 ). Politicians in the line of fire: Incivility and the treatment of women on social media . Research & Politics , 6 ( 1 ). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018816228

Rice R. E. , Atkins K. A. ( 2001 ). Public communication campaigns (3rd ed.). London : Sage Publications .

Robb A. ( 2017 , November 16). Anatomy of a fake news scandal. Rolling Stone. Retrieved from https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/anatomy-of-a-fake-news-scandal-125877/

Roose K. ( 2021 , March 4). What is QAnon, the viral pro-Trump conspiracy theory? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-qanon.html

Royal Society for Public Health ( 2019 ). Moving the needle: Promoting vaccination uptake across the life course. Retrieved from https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/vaccinations/moving-the-needle-promoting-vaccination-uptake-across-the-life-course.html

Sadoski M. , Paivio A. ( 2013 ). Imagery and text a dual coding theory of reading and writing (2nd ed.). New York, NY : Routledge .

Sapienza B. ( 2021 , August 4). Texas politician dies of COVID 5 days after posting anti-vaccine meme. Daily News. Retrieved from https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ny-texas-gop-vaccine-coronavirus-death-20210805-wpkrbyv23nhjjhrxjruofmqi2u-story.html

Schonig J. ( 2020 ). “Liking” as creating: On aesthetic category memes . New Media & Society , 22 ( 1 ), 26 – 48 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819855727

Shi R. , Messaris P. , Cappella J. N. ( 2014 ). Effects of online comments on smokers’ perception of antismoking public service announcements . Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 19 ( 4 ), 975 – 990 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12057

Shifman L. ( 2011 ). An anatomy of a YouTube meme . New Media & Society , 14 ( 2 ), 187 – 203 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811412160

Shifman L. ( 2014 ). Memes in digital culture . Cambridge, MA : MIT Press .

Simms C. ( 2021 , April 7). Georgia DPH launches Covid-19 vaccine ad campaign. Fox 5 Atlanta. Retrieved from https://www.fox5atlanta.com/news/georgia-dph-launches-covid-19-vaccine-ad-campaign

Smith C. ( 2019 ). Weaponized iconoclasm in Internet memes featuring the expression “Fake news.” Discourse & Communication , 13 ( 3 ), 303 – 319 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481319835639

Smith C. , De Houwer J. , Nosek B. ( 2013 ). Consider the source: Persuasion of implicit evaluations is moderated by source credibility . Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin , 39 ( 2 ), 193 – 205 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212472374

Sobieraj S. ( 2018 ). Bitch, slut, skank, cunt: Patterned resistance to women’s visibility in digital publics . Information, Communication & Society , 21 ( 11 ), 1700 – 1714 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348535

Sohn D. , Choi S. ( 2019 ). Social embeddedness of persuasion: Effects of cognitive social structures on information credibility assessment and sharing in social media . International Journal of Advertising , 38 ( 6 ), 824 – 844 . https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1536507

Spence P. , Lachlan K. , Westerman D. , Spates S. ( 2013 ). Where the gates matter less: Ethnicity and perceived source credibility in social media health messages . The Howard Journal of Communications , 24 ( 1 ), 1 – 16 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2013.748593

Spencer S. H. ( 2021 , July 15). Meme spreads falsehood about vaccine transfer through eating meat. Factcheck.org . Retrieved from https://www.factcheck.org/2021/07/scicheck-meme-spreads-falsehood-about-vaccine-transfer/

Spencer S. H. ( 2021 , May 5). Meme featuring DeSantis presents misleading picture of Covid-19 and vaccine safety. Factcheck.org. Retrieved from https://www.factcheck.org/2021/05/scicheck-meme-featuring-desantis-presents-misleading-picture-of-covid-19-and-vaccine-safety/

Su Y. ( 2021 ). It doesn’t take a village to fall for misinformation: Social media use, discussion heterogeneity preference, worry of the virus, faith in scientists, and COVID-19-related misinformation beliefs . Telematics and Informatics , 58 , 101547 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101547

Sureka A. , Goyal V. , Correa D. , Mondal A. ( 2009 ). Polarity classification of subjective words using common-sense knowledge-base. In Sakai H. , Chakraborty M. K. , Slezak D. , Zhu W. (Eds.), Rough sets, fuzzy sets, data mining and granular computing (pp. 486 – 493 ). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Tandoc E. C. ( 2019 ). Tell me who your sources are: Perceptions of news credibility on social media . Journalism Practice , 13 ( 2 ), 178 – 190 . https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1423237

Tankovska H. ( 2021 , Jan. 28). Types of content most likely shared on social media by Gen Z and Millennial internet users in the United States as of September 2019. Statistica . Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/459134/young-adult-teen-social-content-sharing-usa/

Thigpen C. L. , Funk C. ( 2020 , May 21). Most Americans expect a COVID-19 vaccine within a year; 72% say they would get vaccinated. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/21/most-americans-expect-a-covid-19-vaccine-within-a-year-72-say-they-would-get-vaccinated/

Trethewey S. , Beck K. , Symonds R. ( 2020 ). Experience and perspectives of primary care practitioners on the credibility assessment of health-related information online . Postgraduate Medical Journal , 97 ( 1151 ), 608 – 610 . https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138111

Vickery J. ( 2014 ). The curious case of Confession Bear: The reappropriation of online macro-image memes . Information, Communication & Society , 17 ( 3 ), 301 – 325 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.871056

Vogels E. M. ( 2019 , September 9). Millennials stand out for their technology use, but older generations also embrace digital life. Pew Research Center . Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/09/us-generations-technology-use/

Wang Q. , Wang L. , Zhang X. , Mao Y. , Wang P. ( 2017 ). The impact research of online reviews’ sentiment polarity presentation on consumer purchase decision . Information Technology & People 30 ( 3 ), 522 – 541 . https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-06-2014-0116

Wasike B. ( 2017 ). Persuasion in 140 characters: Testing issue framing, persuasion and credibility via Twitter and online news articles in the gun control debate . Computers in Human Behavior , 66 , 179 – 190 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.037

Weeks B. E. , Ardèvol-Abreu A. , Gil de Zúñiga H. ( 2017 ). Online influence? Social media use, opinion leadership, and political persuasion . International Journal of Public Opinion Research , 29 ( 2 ), 214 – 239 . https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv050

Westerwick A. ( 2013 ). Effects of sponsorship, web site design, and Google ranking on the credibility of online information . Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 18 ( 2 ), 80 – 97 . https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12006

Whittaker E. , Kowalski R. M. ( 2015 ). Cyberbullying via social media . Journal of School Violence , 14 ( 1 ), 11 – 29 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.949377

Wilson S. , Wiysonge C. ( 2020 ). Social media and vaccine hesitancy . BMJ Global Health , 5 ( 10 ). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206

Wunsch-Vincent S. , Vickery G. ( 2007 ). Participative web: User-created content. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/57/14/38393115.pdf.678A

Xu Y. , Margolin D. , &, Niederdeppe J. ( 2021 ). Testing Strategies to Increase Source Credibility through Strategic Message Design in the Context of Vaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy . Health communication . 36 ( 11 ), 1354 – 1367 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1751400 . 32308037.

Yang Q. , Beatty M. ( 2016 ). A meta-analytic review of health information credibility: Belief in physicians or belief in peers? Health Information Management , 45 ( 2 ), 80 – 89 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358316639432

Yin C. , Zhang X. ( 2020 ). Incorporating message format into user evaluation of microblog information credibility: A nonlinear perspective . Information Processing & Management , 57 ( 6 ), 102345 – 102345 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102345

Yu R. P. ( 2016 ). The relationship between passive and active non-political social media use and political expression on Facebook and Twitter . Computers in Human Behavior , 58 , 413 – 420 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.019

Pro-mask meme with objective message (expert source).

Anti-mask meme with objective message (nonexpert source).

Pro-mask meme with subjective message (expert source).

Anti-mask meme with subjective message (nonexpert source).

Pro-vaccine meme with objective message (expert source).

Anti-vaccine meme with objective message (nonexpert source).

Pro-vaccine meme with subjective message (expert source).

Anti-vaccine meme with subjective message (nonexpert source).

You just saw a meme on COVID-19 vaccines from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), a federal agency responsible for public health and safety. Please indicate your response to the following statements on a scale of 0–10, where 0 = totally disagree and 10 = totally agree.

You just saw a meme on vaccines from Patriots for Liberty, an activist political action committee. Please indicate your response to the following statements on a scale of 0–10, where 0 = totally disagree and 10 = totally agree.