- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

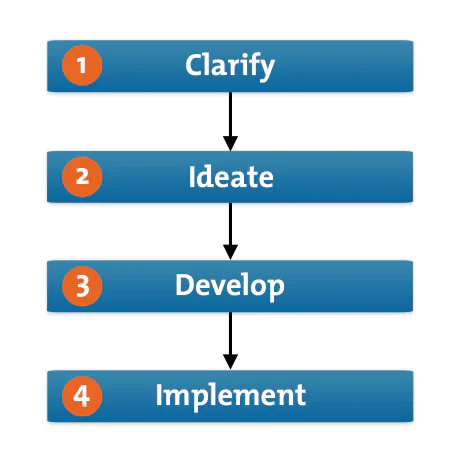

The four stages are:

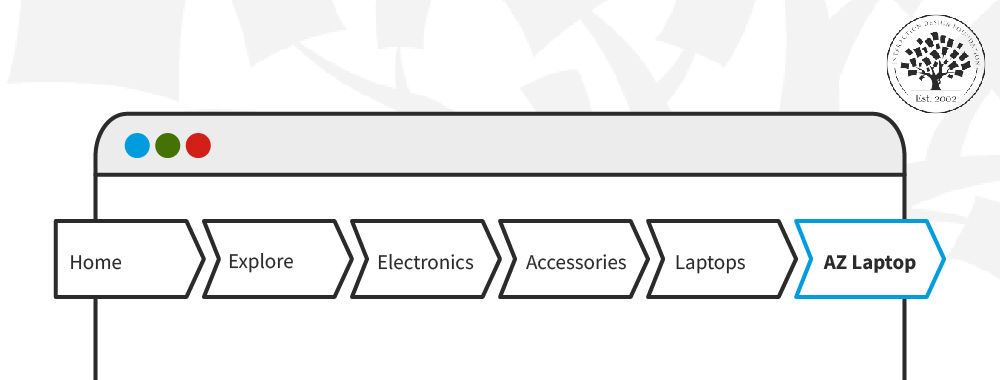

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

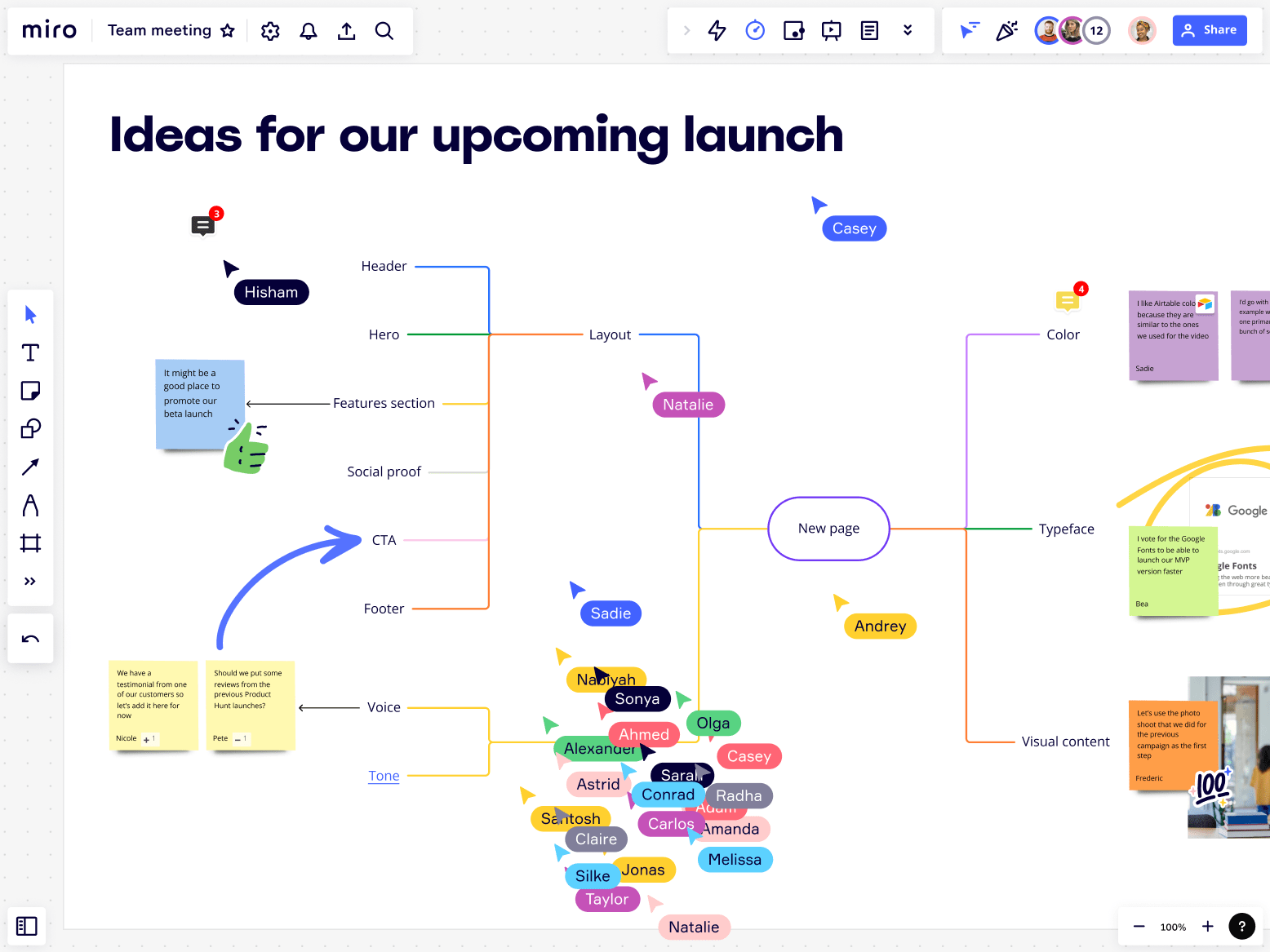

Brainstorming

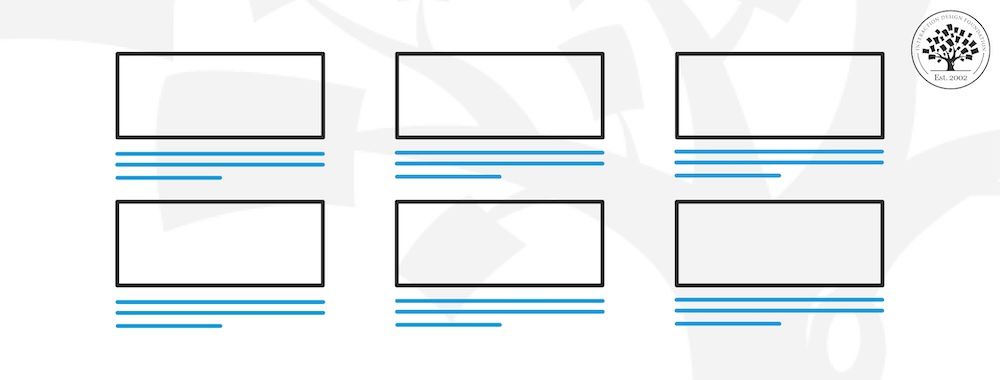

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Creative Problem Solving

Finding innovative solutions to challenges.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine that you're vacuuming your house in a hurry because you've got friends coming over. Frustratingly, you're working hard but you're not getting very far. You kneel down, open up the vacuum cleaner, and pull out the bag. In a cloud of dust, you realize that it's full... again. Coughing, you empty it and wonder why vacuum cleaners with bags still exist!

James Dyson, inventor and founder of Dyson® vacuum cleaners, had exactly the same problem, and he used creative problem solving to find the answer. While many companies focused on developing a better vacuum cleaner filter, he realized that he had to think differently and find a more creative solution. So, he devised a revolutionary way to separate the dirt from the air, and invented the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner. [1]

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of solving problems or identifying opportunities when conventional thinking has failed. It encourages you to find fresh perspectives and come up with innovative solutions, so that you can formulate a plan to overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

In this article, we'll explore what CPS is, and we'll look at its key principles. We'll also provide a model that you can use to generate creative solutions.

About Creative Problem Solving

Alex Osborn, founder of the Creative Education Foundation, first developed creative problem solving in the 1940s, along with the term "brainstorming." And, together with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. Despite its age, this model remains a valuable approach to problem solving. [2]

The early Osborn-Parnes model inspired a number of other tools. One of these is the 2011 CPS Learner's Model, also from the Creative Education Foundation, developed by Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Marie Mance, and co-workers. In this article, we'll use this modern four-step model to explore how you can use CPS to generate innovative, effective solutions.

Why Use Creative Problem Solving?

Dealing with obstacles and challenges is a regular part of working life, and overcoming them isn't always easy. To improve your products, services, communications, and interpersonal skills, and for you and your organization to excel, you need to encourage creative thinking and find innovative solutions that work.

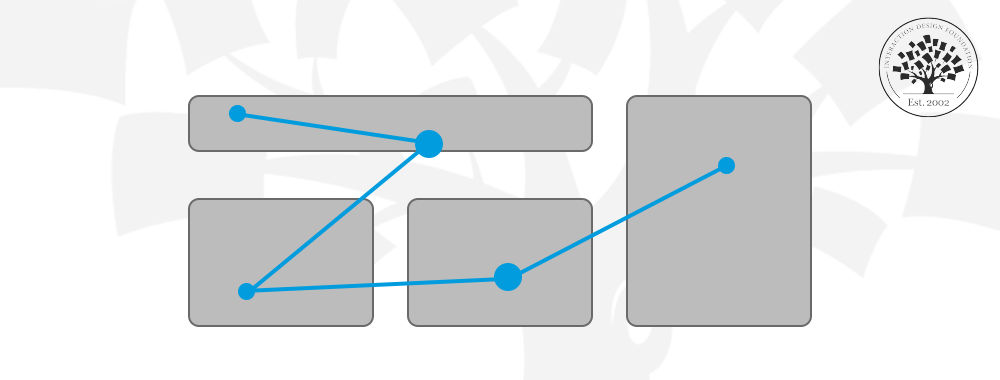

CPS asks you to separate your "divergent" and "convergent" thinking as a way to do this. Divergent thinking is the process of generating lots of potential solutions and possibilities, otherwise known as brainstorming. And convergent thinking involves evaluating those options and choosing the most promising one. Often, we use a combination of the two to develop new ideas or solutions. However, using them simultaneously can result in unbalanced or biased decisions, and can stifle idea generation.

For more on divergent and convergent thinking, and for a useful diagram, see the book "Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making." [3]

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

CPS has four core principles. Let's explore each one in more detail:

- Divergent and convergent thinking must be balanced. The key to creativity is learning how to identify and balance divergent and convergent thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice each one.

- Ask problems as questions. When you rephrase problems and challenges as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities, it's easier to come up with solutions. Asking these types of questions generates lots of rich information, while asking closed questions tends to elicit short answers, such as confirmations or disagreements. Problem statements tend to generate limited responses, or none at all.

- Defer or suspend judgment. As Alex Osborn learned from his work on brainstorming, judging solutions early on tends to shut down idea generation. Instead, there's an appropriate and necessary time to judge ideas during the convergence stage.

- Focus on "Yes, and," rather than "No, but." Language matters when you're generating information and ideas. "Yes, and" encourages people to expand their thoughts, which is necessary during certain stages of CPS. Using the word "but" – preceded by "yes" or "no" – ends conversation, and often negates what's come before it.

How to Use the Tool

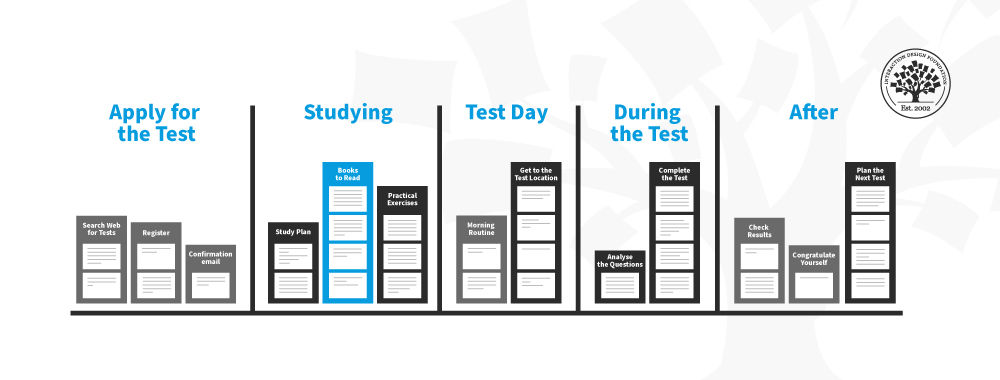

Let's explore how you can use each of the four steps of the CPS Learner's Model (shown in figure 1, below) to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

Figure 1 – CPS Learner's Model

Explore the Vision

Identify your goal, desire or challenge. This is a crucial first step because it's easy to assume, incorrectly, that you know what the problem is. However, you may have missed something or have failed to understand the issue fully, and defining your objective can provide clarity. Read our article, 5 Whys , for more on getting to the root of a problem quickly.

Gather Data

Once you've identified and understood the problem, you can collect information about it and develop a clear understanding of it. Make a note of details such as who and what is involved, all the relevant facts, and everyone's feelings and opinions.

Formulate Questions

When you've increased your awareness of the challenge or problem you've identified, ask questions that will generate solutions. Think about the obstacles you might face and the opportunities they could present.

Explore Ideas

Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions you identified in step 1. It can be tempting to consider solutions that you've tried before, as our minds tend to return to habitual thinking patterns that stop us from producing new ideas. However, this is a chance to use your creativity .

Brainstorming and Mind Maps are great ways to explore ideas during this divergent stage of CPS. And our articles, Encouraging Team Creativity , Problem Solving , Rolestorming , Hurson's Productive Thinking Model , and The Four-Step Innovation Process , can also help boost your creativity.

See our Brainstorming resources within our Creativity section for more on this.

Formulate Solutions

This is the convergent stage of CPS, where you begin to focus on evaluating all of your possible options and come up with solutions. Analyze whether potential solutions meet your needs and criteria, and decide whether you can implement them successfully. Next, consider how you can strengthen them and determine which ones are the best "fit." Our articles, Critical Thinking and ORAPAPA , are useful here.

4. Implement

Formulate a plan.

Once you've chosen the best solution, it's time to develop a plan of action. Start by identifying resources and actions that will allow you to implement your chosen solution. Next, communicate your plan and make sure that everyone involved understands and accepts it.

There have been many adaptations of CPS since its inception, because nobody owns the idea.

For example, Scott Isaksen and Donald Treffinger formed The Creative Problem Solving Group Inc . and the Center for Creative Learning , and their model has evolved over many versions. Blair Miller, Jonathan Vehar and Roger L. Firestien also created their own version, and Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Mary C. Murdock, and Marie Mance developed CPS: The Thinking Skills Model. [4] Tim Hurson created The Productive Thinking Model , and Paul Reali developed CPS: Competencies Model. [5]

Sid Parnes continued to adapt the CPS model by adding concepts such as imagery and visualization , and he founded the Creative Studies Project to teach CPS. For more information on the evolution and development of the CPS process, see Creative Problem Solving Version 6.1 by Donald J. Treffinger, Scott G. Isaksen, and K. Brian Dorval. [6]

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Infographic

See our infographic on Creative Problem Solving .

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

There have been many adaptations of the original Osborn-Parnes model, but they all involve a clear structure of identifying the problem, generating new ideas, evaluating the options, and then formulating a plan for successful implementation.

[1] Entrepreneur (2012). James Dyson on Using Failure to Drive Success [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 27, 2022.]

[2] Creative Education Foundation (2015). The CPS Process [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022.]

[3] Kaner, S. et al. (2014). 'Facilitator′s Guide to Participatory Decision–Making,' San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Puccio, G., Mance, M., and Murdock, M. (2011). 'Creative Leadership: Skils That Drive Change' (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[5] OmniSkills (2013). Creative Problem Solving [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022].

[6] Treffinger, G., Isaksen, S., and Dorval, B. (2010). Creative Problem Solving (CPS Version 6.1). Center for Creative Learning, Inc. & Creative Problem Solving Group, Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

What is problem solving.

Book Insights

The Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems and Selling Ideas With Pictures

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Team Management Skills

5 Phrases That Kill Collaboration

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How do i manage a hybrid team.

Adjusting your management style to a hybrid world

The Life Career Rainbow

Finding a Work-Life Balance That Suits You

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Anger management.

Control the Rage and Deal With Your Emotions

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Pain Points

- Case Studies

- Flexible Products

- Expert Insights

- Research Studies

- Creativity and Culture

- Management and Leadership

- Business Solutions

- Member Spotlight

- Employee Spotlight

Understanding the four stages of the creative process

There’s a lot that science can teach us about what goes into the creative process—and how each one of us can optimize our own.

How do great artists and innovators come up with their most brilliant ideas ? And by what kind of alchemical process are they able to bring those ideas to life?

I have eagerly sought the answers to these questions over the past decade of my career as a psychology writer. My fascination with the lives and minds of brilliant artists and innovators has led me on a quest to discover what makes us creative , where ideas come from, and how they come to life. But even after writing an entire book on the science of creativity and designing a creative personality test , there are more questions than answers in my mind.

Decades of research have yet to uncover the unique spark of creative genius. Creativity is as perplexing to us today as it was to the ancients, who cast creative genius in the realm of the supernatural and declared it the work of the muses.

What the science does show is that creative people are complex and contradictory. Their creative processes tend to be chaotic and nonlinear—which seems to mirror what’s going on in their brains. Contrary to the “right-brain myth,” creativity doesn’t just involve a single brain region or even a single side of the brain. Instead, the creative process draws on the whole brain. It’s a dynamic interplay of many diverse brain regions, thinking styles, emotions, and unconscious and conscious processing systems coming together in unusual and unexpected ways.

But while we may never find the formula for creativity, there’s still a lot that science can teach us about what goes into the creative process—and how each one of us can optimize our own.

Understanding your own creative process

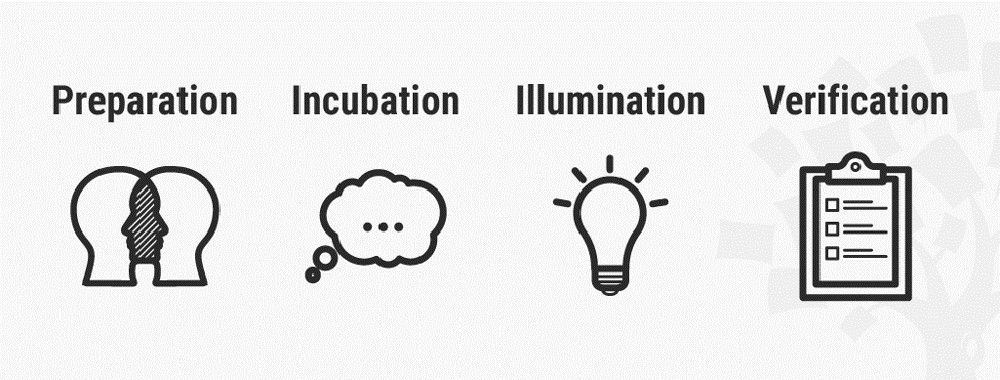

One of the most illuminating things I’ve found is a popular four-stage model of the creative process developed in the 1920s. In his book The Art of Thought , British psychologist Graham Wallas outlined a theory of the creative process based on many years of observing and studying accounts of inventors and other creative types at work.

The four stages of the creative process:

Stage 1: preparation.

The creative process begins with preparation: gathering information and materials, identifying sources of inspiration, and acquiring knowledge about the project or problem at hand. This is often an internal process (thinking deeply to generate and engage with ideas) as well as an external one (going out into the world to gather the necessary data, resources, materials, and expertise).

Stage 2: Incubation

Next, the ideas and information gathered in stage 1 marinate in the mind. As ideas slowly simmer, the work deepens and new connections are formed. During this period of germination, the artist takes their focus off the problem and allows the mind to rest. While the conscious mind wanders, the unconscious engages in what Einstein called “combinatory play”: taking diverse ideas and influences and finding new ways to bring them together.

Stage 3: Illumination

Next comes the elusive aha moment. After a period of incubation, insights arise from the deeper layers of the mind and break through to conscious awareness, often in a dramatic way. It’s the sudden Eureka! that comes when you’re in the shower, taking a walk, or occupied with something completely unrelated. Seemingly out of nowhere, the solution presents itself.

Stage 4: Verification

Following the aha moment, the words get written down, the vision is committed to paint or clay, the business plan is developed. Whatever ideas and insights arose in stage 3 are fleshed out and developed. The artist uses critical thinking and aesthetic judgment skills to hone and refine the work and then communicate its value to others.

Of course, these stages don’t always play out in such an orderly, linear fashion. The creative process tends to look more like a zigzag or spiral than a straight line. The model certainly has its limitations, but it can offer a road map of sorts for our own creative journey, offering a direction, if not a destination. It can help us become more aware of where we’re at in our own process, where we need to go, and the mental processes that can help us get there. And when the process gets a little too messy, coming back to this framework can help us to recenter, realign, and chart the path ahead.

For instance, if you can’t seem to get from incubation to illumination, the solution might be to go back to stage 1, gathering more resources and knowledge to find that missing element. Or perhaps, in the quest for productivity , you’ve made the all-too-common mistake of skipping straight to stage 4, pushing ahead with a half-baked idea before it’s fully marinated. In that case, carving out time and space for stage 2 may be the necessary detour.

Related articles

How to optimize your creative process for ultimate success

But let’s dig a little deeper: As I’ve contemplated and applied the four-stage model in my own work, I’ve found within it a much more profound insight into the mysteries of creation.

At its heart, any creative process is about discovering something new within ourselves and then bringing that something into the world for others to experience and enjoy. The work of the artist, the visionary, the innovator is to bridge their inner and outer worlds—taking something that only exists within their own mind and heart and soul and birthing it into concrete, tangible form (you know, not unlike that other kind of creative process).

Any creative process is a dance between the inner and the outer; the unconscious and conscious mind; dreaming and doing; madness and method; solitary reflection and active collaboration. Psychologists describe it in simple terms of inspiration (coming up with ideas) and generation (bringing ideas to life).

In the four-stage model, we can see how the internal and external elements of the creative process interact. stages 2 and 3 are all about inspiration: dreaming, reflecting, imagining, opening up to inspiration, and allowing the unconscious mind to do its work. Stages 1 and 4, meanwhile, are about generation: doing the external work of research, planning, execution, and collaboration. Through a dynamic dance of inspiration and generation, brilliant work comes to life.

How does this help us in our own creative process? The more we master this balance, the more we can tap into our creative potential. We all have a preference for one side over the other, and by becoming more aware of our natural inclinations, we can learn how to optimize our strengths and minimize our weaknesses.

More inward-focused, idea-generating types excel in stages 2 and 3: getting inspired and coming up with brilliant ideas. But they run the risk of getting stuck in their own heads and failing to materialize their brilliant ideas in the world. These thinkers and dreamers often need to bring more time and focus to stages 1 and 4 in order to keep their creative process on track. Balance inspiration with generation by creating the necessary structures to help you commit to action and put one foot in front of the other to make it happen—or just collaborate with a doer who you can outsource your ideas to!

Doer types, on the other hand, shine in stages 1 and 4. They’re brilliant at getting things done, but they risk putting all their focus on productivity at the expense of the inner work and big-picture thinking that helps produce truly inspired work. When we bypass the critical work that occurs in the incubation stage, we miss out on our most original and groundbreaking ideas. If you’re a doer/generator, you can up-level your creative process by clearing out the space in your mind and your schedule to dream, imagine, reflect, and contemplate.

By seeking a balance of these opposing forces, we can bring some order to the chaos of the creative process. And as we become dreamers who do and doers who dream, we empower ourselves to share more of our creative gifts with the world.

WeWork’s space products including On Demand , All Access , and dedicated spaces help businesses of all sizes solve their biggest challenges.

Carolyn Gregoire is a writer and creative consultant living in Brooklyn. She is the co-author of Wired to Create: Unravelling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind and the creator of the Creative Types personality test. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, Scientific American, TIME, Harvard Business Review, and other publications.

Designed to cultivate a positive and respectful working environment, here are the most common coworking etiquette rules.

“Busyness” doesn’t always equate with progress—learning how to prioritize tasks will help you make the most of your workday

Attending lots of virtual meetings can be tiring. Here’s how to spot symptoms of fatigue and how to fix them

What is creative problem-solving?

Table of Contents

An introduction to creative problem-solving.

Creative problem-solving is an essential skill that goes beyond basic brainstorming . It entails a holistic approach to challenges, melding logical processes with imaginative techniques to conceive innovative solutions. As our world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, the ability to think creatively and solve problems with fresh perspectives becomes invaluable for individuals, businesses, and communities alike.

Importance of divergent and convergent thinking

At the heart of creative problem-solving lies the balance between divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking encourages free-flowing, unrestricted ideation, leading to a plethora of potential solutions. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is about narrowing down those options to find the most viable solution. This dual approach ensures both breadth and depth in the problem-solving process.

Emphasis on collaboration and diverse perspectives

No single perspective has a monopoly on insight. Collaborating with individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and areas of expertise offers a richer tapestry of ideas. Embracing diverse perspectives not only broadens the pool of solutions but also ensures more holistic and well-rounded outcomes.

Nurturing a risk-taking and experimental mindset

The fear of failure can be the most significant barrier to any undertaking. It's essential to foster an environment where risk-taking and experimentation are celebrated. This involves viewing failures not as setbacks but as invaluable learning experiences that pave the way for eventual success.

The role of intuition and lateral thinking

Sometimes, the path to a solution is not linear. Lateral thinking and intuition allow for making connections between seemingly unrelated elements. These 'eureka' moments often lead to breakthrough solutions that conventional methods might overlook.

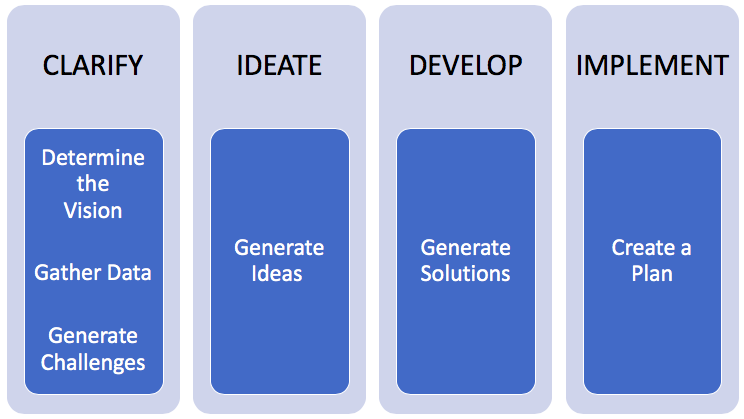

Stages of the creative problem-solving process

The creative problem-solving process is typically broken down into several stages. Each stage plays a crucial role in understanding, addressing, and resolving challenges in innovative ways.

Clarifying: Understanding the real problem or challenge

Before diving into solutions, one must first understand the problem at its core. This involves asking probing questions, gathering data, and viewing the challenge from various angles. A clear comprehension of the problem ensures that effort and resources are channeled correctly.

Ideating: Generating diverse and multiple solutions

Once the problem is clarified, the focus shifts to generating as many solutions as possible. This stage champions quantity over quality, as the aim is to explore the breadth of possibilities without immediately passing judgment.

Developing: Refining and honing promising solutions

With a list of potential solutions in hand, it's time to refine and develop the most promising ones. This involves evaluating each idea's feasibility, potential impact, and any associated risks, then enhancing or combining solutions to maximize effectiveness.

Implementing: Acting on the best solutions

Once a solution has been honed, it's time to put it into action. This involves planning, allocating resources, and monitoring the results to ensure the solution is effectively addressing the problem.

Techniques for creative problem-solving

Solving complex problems in a fresh way can be a daunting task to start on. Here are a few techniques that can help kickstart the process:

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a widely-used technique that involves generating as many ideas as possible within a set timeframe. Variants like brainwriting (where ideas are written down rather than spoken) and reverse brainstorming (thinking of ways to cause the problem) can offer fresh perspectives and ensure broader participation.

Mind mapping

Mind mapping is a visual tool that helps structure information, making connections between disparate pieces of data. It is particularly useful in organizing thoughts, visualizing relationships, and ensuring a comprehensive approach to a problem.

SCAMPER technique

SCAMPER stands for Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse. This technique prompts individuals to look at existing products, services, or processes in new ways, leading to innovative solutions.

Benefits of creative problem-solving

Creative problem-solving offers numerous benefits, both at the individual and organizational levels. Some of the most prominent advantages include:

Finding novel solutions to old problems

Traditional problems that have resisted conventional solutions often succumb to creative approaches. By looking at challenges from fresh angles and blending different techniques, we can unlock novel solutions previously deemed impossible.

Enhanced adaptability in changing environments

In our rapidly evolving world, the ability to adapt is critical. Creative problem-solving equips individuals and organizations with the agility to pivot and adapt to changing circumstances, ensuring resilience and longevity.

Building collaborative and innovative teams

Teams that embrace creative problem-solving tend to be more collaborative and innovative. They value diversity of thought, are open to experimentation, and are more likely to challenge the status quo, leading to groundbreaking results.

Fostering a culture of continuous learning and improvement

Creative problem-solving is not just about finding solutions; it's also about continuous learning and improvement. By encouraging an environment of curiosity and exploration, organizations can ensure that they are always at the cutting edge, ready to tackle future challenges head-on.

Get on board in seconds

Join thousands of teams using Miro to do their best work yet.

Project Bliss

The osborn parnes creative problem-solving process.

The Osborn Parnes creative problem-solving process is a structured way to generate creative and innovative ways to address problems.

If you want to grow in your career, you need to show you can provide value. This is true no matter where you sit in an organization.

You likely do this in your day-to-day activities.

But if you want to stand out, or do better than the minimum required for your job, you need to find ways to be more valuable to your company.

Problem-solving skills are a great way to do this.

And there are many problem-solving approaches you can use.

By bringing creativity into the approach, you can get an even better variety of potential solutions and ideas.

Benefits of Using Creative Problem Solving

Using a creative problem-solving approach has multiple benefits:

- It provides a structured approach to problem-solving.

- It results in more possible solution options using both divergent and convergent approaches.

- You create innovative approaches to change.

- It’s a collaborative approach that allows multiple participants.

- By engaging multiple participants in finding solutions, you create a positive environment and buy-in from participants.

- This approach can be learned.

- You can use these skills in various areas of life.

Origin of the Osborn Parnes Creative Problem-solving Process

Alex Osborne and Sidney Parnes both focused much of their work on creativity. Osborn is credited with creating brainstorming techniques in the 1940s. He founded the Creative Education Foundation, which Parnes led.

The two collaborated to formalize the process., which is still taught today.

“Creativity can solve almost any problem. The creative act, the defeat of habit by originality, overcomes everything.” – George Lois

What is the Osborn Parnes Creative Problem-solving Process

The Osborn Parnes model is a structured approach to help individuals and groups apply creativity to problem-solving.

There are 6 steps to the Osborn Parnes Creative Problem-Solving Process.

1. Mess-Finding / Objective Finding

During the Objective-Finding phase, you determine what the goal of your problem-solving process will be.

What’s the intent of carrying out your problem-solving process? Get clear on why you’re doing it. This helps ensure you focus your efforts in the right area.

Knowing your goals and objectives will help you focus your efforts where they have the most value.

2. Fact-Finding

The Fact-F inding phase ensures you gather enough data to fully understand the problem.

Once you’ve identified the area you want to focus on, gather as much information as you can. This helps you get a full picture of the situation.

Collect data, gather information, make observations, and employ other methods of learning more about the situation.

You may wish to identify success criteria for the situation at this step, also.

3. Problem-Finding

The Problem Finding phase allows you to dig deeper into the problem and find the root or real problem you want to focus on. Reframe the problem in order to generate creative and valuable solutions.

Look at the problem and information you’ve gathered in order to better clarify the problem you’ll be solving.

Make sure you’re focusing on the right problem before moving forward to develop a solution.

Personal example: you may think you want to get a second job so you can have more money to take your family on vacations. Upon deeper exploration, you realize your real desire and goal is to find ways to spend more time with your family . That’s the real problem you wish to solve.

Work example: your team has too much work to do and doesn’t have the time to create new software features that customers want. By digging in and reframing the problem you realize the team is more focused on handling support calls. You need to find a solution to handling the support calls, which would free up time for the team to focus on new development. You dig even deeper and learn the support calls are primarily focused on one problem that could be fixed to solve the problem.

“If you define the problem correctly, you almost have the solution.” – Steve Jobs

4. Idea-Finding

The Idea-F inding phase allows your team to generate many options for addressing the problem.

Come up with many different potential ideas to address the problem.

Don’t judge the suggestions. Instead, welcome even crazy ideas. Unexpected or odd ideas may help others generate great ideas.

Use brainstorming techniques, affinity mapping and grouping, and other tools to organize the input.

Use “yes, and…” statements rather than “No, but…” statements to keep ideas flowing and avoid discouraging participants from contributing.

5. Solution-Finding

The Solution Finding phase allows you to choose the best options from the ideas generated in the Idea Finding phase.

Set selection criteria for evaluating the best choices in order to select the best option. You can weight your criteria if needed to place more emphasis on criteria that may be more important than others.

Create a prioritization matix with your criteria to help you choose what to focus on.

6. Action-Finding

In the Action-Finding phase, develop a plan of action to implement the solution you’ve settled on as the best choice.

Depending on how complex the solution is, you may need to create a more complex plan of action. Your work breakdown structure of activities may be complex or simple.

When creating your action plan, identify who’s responsible for each of the activities, dependencies, and due dates.

If your chosen solution will impact many people or teams, you may need to do an impact analysis, create a communication plan , and get buy-in or participation from more groups. If your solution is simple, you will most likely have a much simpler plan.

“Creativity involves breaking out of established patterns in order to look at things in a different way.” – Edward de Bono

Creative Problem-Solving Categories

Osborn and Parnes started working on creative problem-solving approaches in the 1950s. Since then, the process has evolved, but the focus on using creativity still remains important.

More recent modifications group the activities into four categories:

Each of these categories contain the steps listed above to carry out the problem-solving process.

As you can see, the steps are still there, but the grouping helps provide a bit more structure to the way teams can think about it.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

The creative problem-solving process uses two thinking styles: divergent thinking and convergent thinking.

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, the just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while” – Steve Jobs

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking is the creative process of generating multiple possible solutions and ideas. It’s usually done in a spontaneous approach where participants share multiple ideas, such as in a brainstorming session.

This approach allows more “out of the box” thinking for creative ideas.

Once ideas are generated via creative, free-flowing divergent approach, you then move onto convergent thinking.

Use questions to stimulate creative thinking.

When conducting divergent thinking sessions, don’t criticize suggestions. Instead, welcome ideas. Build on ideas that have been presented and even improve them if possible.

Instead of saying “No, but…” welcome ideas with responses such as “Yes, and…”

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” – Albert Einstein

Convergent Thinking

Convergent thinking is the process of evaluating the ideas, analyzing them, and selecting the best solution.

It’s the process of taking all the information gathered in divergent thinking, analyzing it, and finding the single best solution to the problem.

Determine screening criteria for evaluating ideas. Spend time evaluating the options, and even improve suggestions if possible or needed.

If an idea seems too crazy, don’t immediately dismiss it. A friend told me once he thought the Bird or Lime scooter business models would never work. If it had been pitched to him, his response would have been “People won’t use them. They’ll destroy them. People won’t be allowed to use them without helmets and won’t be permitted to leave them on the sidewalk.” But it’s turned out in many cities to be a great mode of short-distance transportation.

Someone taking a strictly convergent approach to problem-solving might skip a creative brainstorming session and instead try to think of a straightforward answer to the problem.

However, it’s useful to employ both approaches to come up with more options and creative solutions to problems.

“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.” – Maya Angelou

Running Your Problem-Solving Sessions

When using these techniques, use your great facilitation and leadership skills to keep the group focused and moving forward.

For the best meetings possible, follow the guidance in my book Bad Meetings Happen to Good People: How to Run Meetings That Are Effective, Focused, and Produce Results .

Problem-solving skills and tools are useful both at work and other areas of life.

It’s liberating to know you don’t have to have all the answers to make improvements.

Instead, knowing how to lead and collaborate with others to find solutions will help you stand out as a strong leader and valuable team member to your employer.

Don’t shy away from leading an improvement effort when faced with challenges. Doing so will give you greater confidence to search for solutions in other situations.

And you’ll be known as someone who can tackle challenges and make improvements in the organization. Creating this reputation will be great for your career.

“Think left and think right and think low and think high. Oh, the thinks you can think up if only you try” – Dr. Seuss

Related Posts

Leigh Espy is a project manager and coach with experience working in startups, government, and the corporate world. She works with project managers who want to improve their skills and grow in their career, and entrepreneurs and small businesses to help them get more done. She also remembers her early career days and loves working with new project managers and those who want to make a career move into project management.

I’m glad ‘problem finding’ is the basis for this. However, I think this is still reductive and presumes a ‘problem’ to be ‘solved’. I see ‘problem solving’ as a long way down the path in creativity. Creativity starts with an objective, a challenge, an opportunity. Not a ‘problem’. A problem gets an answer. A challenge gets possibilities.

am a university student from kenya and my lecturer gave us a question on how to use osbons model to systemtically analyze how to find solutions about corruption in our country and i think the info i got here will help me tackle that question alot

Great reading – it helped me with my Creativity Tools homework

- Pingback: Creative Problem-Solving – Riyanthi Sianturi November 7, 2020

- Board of Directors

What is CPS?

Cps = c reative p roblem s olving, cps is a proven method for approaching a problem or a challenge in an imaginative and innovative way. it helps you redefine the problems and opportunities you face, come up with new, innovative responses and solutions, and then take action..

Why does CPS work?

CPS begins with two assumptions:

- Everyone is creative in some way.

- Creative skills can be learned and enhanced.

Osborn noted there are two distinct kinds of thinking that are essential to being creative:

Divergent thinking.

Brainstorming is often misunderstood as the entire Creative Problem Solving process. Brainstorming is the divergent thinking phase of the CPS process. It is not simply a group of people in a meeting coming up with ideas in a disorganized fashion. Brainstorming at its core is generating lots of ideas. Divergence allows us to state and move beyond obvious ideas to breakthrough ideas. (Fun Fact: Alex Osborn, founder of CEF, coined the term “brainstorm.” Osborn was the “O” from the ad agency BBDO.)

Convergent Thinking

Convergent thinking applies criteria to brainstormed ideas so that those ideas can become actionable innovations. Divergence provides the raw material that pushes beyond every day thinking, and convergence tools help us screen, select, evaluate, and refine ideas, while retaining novelty and newness.

To drive a car, you need both the gas and the brake.

But you cannot use the gas and brake pedals at the same time — you use them alternately to make the car go. Think of the gas pedal as Divergence , and the brake pedal as Convergence . Used together you move forward to a new destination.

Each of us use divergent and convergent thinking daily, intuitively. CPS is a deliberate process that allows you to harness your natural creative ability and apply it purposefully to problems, challenges, and opportunities.

The CPS Process

Based on the osborn-parnes process, the cps model uses plain language and recent research., the basic structure is comprised of four stages with a total of six explicit process steps. , each step uses divergent and convergent thinking..

Learner’s Model based on work of G.J. Puccio, M. Mance, M.C. Murdock, B. Miller, J. Vehar, R. Firestien, S. Thurber, & D. Nielsen (2011)

Explore the Vision. Identify the goal, wish, or challenge.

Gather Data. Describe and generate data to enable a clear understanding of the challenge.

Formulate Challenges. Sharpen awareness of the challenge and create challenge questions that invite solutions.

Explore Ideas. Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions.

Formulate Solutions. To move from ideas to solutions. Evaluate, strengthen, and select solutions for best “fit.”

Formulate a Plan. Explore acceptance and identify resources and actions that will support implementation of the selected solution(s).

Explore Ideas. Generate ideas that answer the challenge question

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

- Everyone is creative.

- Divergent and Convergent Thinking Must be Balanced. Keys to creativity are learning ways to identify and balance expanding and contracting thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice them.

- Ask Problems as Questions. Solutions are more readily invited and developed when challenges and problems are restated as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities. Such questions generate lots of rich information, while closed-ended questions tend to elicit confirmation or denial. Statements tend to generate limited or no response at all.

- Defer or Suspend Judgment. As Osborn learned in his early work on brainstorming, the instantaneous judgment in response to an idea shuts down idea generation . There is an appropriate and necessary time to apply judgement when converging.

- Focus on “Yes, and” rather than “No, but.” When generating information and ideas, language matters. “Yes, and…” allows continuation and expansion , which is necessary in certain stages of CPS. The use of the word “but” – preceded by “yes” or “no” – closes down conversation, negating everything that has come before it.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

Performance & Leadership Unleashed

Creative Problem Solving

“Every problem is an opportunity in disguise.” — John Adams

Imagine if you come up with new ideas and solve problems better, faster, easier?

Imagine if you could easily leverage the thinking from multiple experts and different points of view?

That’s the promise and the premise of Creative Problem Solving.

As Einstein put it, “Creativity is intelligence having fun.”

Creative problem solving is a systematic approach that empowers individuals and teams to unleash their imagination , explore diverse perspectives, and generate innovative solutions to complex challenges.

Throughout my years at Microsoft, I’ve used variations of Creative Problem Solving to tackle big, audacious challenges and create new opportunities for innovation.

I this article, I walkthrough the original Creative Problem Solving process and variations so that you can more fully appreciate the power of the process and how it’s evolved over the years.

On This Page

Innovation is a Team Sport What is Creative Problem Solving? Variations of Creative Problem Solving Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Criticisms of Creative Problem Solving Creative Problem Solving 21st Century FourSight Thinking Profiles Basadur’s Innovative Process Synetics SCAMPER Design Thinking

Innovation is a Team Sport

Recognizing that innovation is a team sport , I understood the importance of equipping myself and my teams with the right tools for the job.

By leveraging different problem-solving approaches, I have been able to navigate complex landscapes , think outside the box, and find unique solutions.

Creative Problem Solving has served as a valuable compass , guiding me to explore uncharted territories and unlock the potential for groundbreaking ideas.

With a diverse set of tools in my toolbox, I’ve been better prepared to navigate the dynamic world of innovation and contribute to the success and amplify impact for many teams and many orgs for many years.

By learning and teaching Creative Problem Solving we empower diverse teams to appreciate and embrace cognitive diversity to solve problems and create new opportunities with skill.

What is the Creative Problem Solving Process?

The Creative Problem Solving (CPS) framework is a systematic approach for generating innovative solutions to complex problems.

It’s effectively a process framework.

It provides a structured process that helps individuals and teams think creatively, explore possibilities, and develop practical solutions.

The Creative Problem Solving process framework typically consists of the following stages:

- Clarify : In this stage, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, ensuring a shared understanding among participants. The key objectives, constraints, and desired outcomes are identified.

- Generate Ideas : During this stage, participants engage in divergent thinking to generate a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. The focus is on quantity and deferring judgment, encouraging free-flowing creativity.

- Develop Solutions : In this stage, the generated ideas are evaluated, refined, and developed into viable solutions. Participants explore the feasibility, practicality, and potential impact of each idea, considering the resources and constraints at hand.

- Implement : Once a solution or set of solutions is selected, an action plan is developed to guide the implementation process. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and identifying the necessary resources.

- Evaluate : After implementing the solution, the outcomes and results are evaluated to assess the effectiveness and impact. Lessons learned are captured to inform future problem-solving efforts and improve the process.

Throughout the Creative Problem Solving framework, various creativity techniques and tools can be employed to stimulate idea generation, such as brainstorming, mind mapping, SCAMPER (Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse), and others.

These techniques help break through traditional thinking patterns and encourage novel approaches to problem-solving.

What are Variations of the Creative Problem Solving Process?

There are several variations of the Creative Problem Solving process, each emphasizing different steps or stages.

Here are five variations that are commonly referenced:

- Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving : This is one of the earliest and most widely used versions of Creative Problem Solving. It consists of six stages: Objective Finding, Fact Finding, Problem Finding, Idea Finding, Solution Finding, and Acceptance Finding. It follows a systematic approach to identify and solve problems creatively.

- Creative Problem Solving 21st Century : Creative Problem Solving 21st Century, developed by Roger Firestien, is an innovative approach that empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, wishes, or challenges by providing a structured process to generate ideas, develop solutions, and create a plan of action.

- FourSight Thinking Profiles : This model introduces four stages in the Creative Problem Solving process: Clarify, Ideate, Develop, and Implement. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the problem, generating a range of ideas, developing and evaluating those ideas, and finally implementing the best solution.

- Basadur’s Innovative Process : Basadur’s Innovative Process, developed by Min Basadur, is a systematic and iterative process that guides teams through eight steps to effectively identify, define, generate ideas, evaluate, and implement solutions, resulting in creative and innovative outcomes.

- Synectics : Synectics is a Creative Problem Solving variation that focuses on creating new connections and insights. It involves stages such as Problem Clarification, Idea Generation, Evaluation, and Action Planning. Synectics encourages thinking from diverse perspectives and applying analogical reasoning.

- SCAMPER : SCAMPER is an acronym representing different creative thinking techniques to stimulate idea generation. Each letter stands for a strategy: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Rearrange. SCAMPER is used as a tool within the Creative Problem Solving process to generate innovative ideas by applying these strategies.

- Design Thinking : While not strictly a variation of Creative Problem Solving, Design Thinking is a problem-solving approach that shares similarities with Creative Problem Solving. It typically includes stages such as Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. Design Thinking focuses on understanding users’ needs, ideating and prototyping solutions, and iterating based on feedback.

These are just a few examples of variations within the Creative Problem Solving framework. Each variation provides a unique perspective on the problem-solving process, allowing individuals and teams to approach challenges in different ways.

Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving (CPS)

The original Creative Problem Solving (CPS) process, developed by Alex Osborn and Sidney Parnes, consists of the following steps:

- Objective Finding : In this step, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, and the objectives and goals are established. It involves understanding the problem from different perspectives, gathering relevant information, and identifying the desired outcomes.

- Fact Finding : The objective of this step is to gather information, data, and facts related to the problem. It involves conducting research, analyzing the current situation, and seeking a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the problem.

- Problem Finding : In this step, the focus is on identifying the root causes and underlying issues contributing to the problem. It involves reframing the problem, exploring it from different angles, and asking probing questions to uncover insights and uncover potential areas for improvement.

- Idea Finding : This step involves generating a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. Participants engage in divergent thinking techniques, such as brainstorming, to produce as many ideas as possible without judgment or evaluation. The aim is to encourage creativity and explore novel possibilities.

- Solution Finding : After generating a pool of ideas, the next step is to evaluate and select the most promising solutions. This involves convergent thinking, where participants assess the feasibility, desirability, and viability of each idea. Criteria are established to assess and rank the solutions based on their potential effectiveness.

- Acceptance Finding : In this step, the selected solution is refined, developed, and adapted to fit the specific context and constraints. Strategies are identified to overcome potential obstacles and challenges. Participants work to gain acceptance and support for the chosen solution from stakeholders.

- Solution Implementation : Once the solution is finalized, an action plan is developed to guide its implementation. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and securing the necessary resources. The solution is put into action, and progress is monitored to ensure successful execution.

- Monitoring and Evaluation : The final step involves tracking the progress and evaluating the outcomes of the implemented solution. Lessons learned are captured, and feedback is gathered to inform future problem-solving efforts. This step helps refine the process and improve future problem-solving endeavors.

The CPS process is designed to be iterative and flexible, allowing for feedback loops and refinement at each stage. It encourages collaboration, open-mindedness, and the exploration of diverse perspectives to foster creative problem-solving and innovation.

Criticisms of the Original Creative Problem Solving Approach

While Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving is a widely used and effective problem-solving framework, it does have some criticisms, challenges, and limitations.

These include:

- Linear Process : CPS follows a structured and linear process, which may not fully capture the dynamic and non-linear nature of complex problems.

- Overemphasis on Rationality : CPS primarily focuses on logical and rational thinking, potentially overlooking the value of intuitive or emotional insights in the problem-solving process.

- Limited Cultural Diversity : The CPS framework may not adequately address the cultural and contextual differences that influence problem-solving approaches across diverse groups and regions.

- Time and Resource Intensive : Implementing the CPS process can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring significant commitment and investment from participants and organizations.

- Lack of Flexibility : The structured nature of CPS may restrict the exploration of alternative problem-solving methods, limiting adaptability to different situations or contexts.

- Limited Emphasis on Collaboration : Although CPS encourages group participation, it may not fully leverage the collective intelligence and diverse perspectives of teams, potentially limiting the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving.

- Potential Resistance to Change : Organizations or individuals accustomed to traditional problem-solving approaches may encounter resistance or difficulty in embracing the CPS methodology and its associated mindset shift.

Despite these criticisms and challenges, the CPS framework remains a valuable tool for systematic problem-solving.

Adapting and supplementing it with other methodologies and approaches can help overcome some of its limitations and enhance overall effectiveness.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Roger Firestien is a master facilitator of the Creative Problem Solving process. He has been using it, studying it, researching it, and teaching it for 40 years.

According to him, the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

He has developed a program that focuses on assisting facilitators of the Creative Problem Solving Process to smoothly and confidently transition from one stage to the next in the Creative Problem Solving process as well as learn how to talk less and accomplish more while facilitating Creative Problem Solving.

Creative Problem Solving empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, manifesting their aspirations, or addressing challenges they wish to overcome.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, CPS recognizes that the user’s objective may not necessarily be framed as a problem. Instead, CPS supports users in realizing their goals and desires, providing a versatile framework to guide them towards success.

Why Creative Problem Solving 21st Century?

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century addresses challenges with the original Creative Problem Solving method by adapting it to the demands of the modern era. Roger Firestien recognized that the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

The Creative Problem Solving 21st Century program focuses on helping facilitators smoothly transition between different stages of the problem-solving process. It also teaches them how to be more efficient and productive in their facilitation by talking less and achieving more results.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, Creative Problem Solving 21st Century acknowledges that users may not always frame their objectives as problems. It recognizes that individuals have goals, wishes, and challenges they want to address or achieve. Creative Problem Solving provides a flexible framework to guide users towards success in realizing their aspirations.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century builds upon the foundational work of pioneers such as Osborn, Parnes, Miller, and Firestien. It incorporates practical techniques like PPC (Pluses, Potentials, Concerns) and emphasizes the importance of creative leadership skills in driving change.

Stages of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

- Clarify the Problem

- Generate Ideas

- Develop Solutions

- Plan for Action

Steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Here are stages and steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century per Roger Firestien:

CLARIFY THE PROBLEM

Start here when you are looking to improve, create, or solve something. You want to explore the facts, feelings and data around it. You want to find the best problem to solve.

IDENTIFY GOAL, WISH OR CHALLENGE Start with a goal, wish or challenge that begins with the phrase: “I wish…” or “It would be great if…”

Diverge : If you are not quite clear on a goal then create, invent, solve or improve.

Converge : Select the goal, wish or challenge on which you have Ownership, Motivation and a need for Imagination.

GATHER DATA

Diverge : What is a brief history of your goal, wish or challenge? What have you already thought of or tried? What might be your ideal goal?

Converge : Select the key data that reveals a new insight into the situation or that is important to consider throughout the remainder of the process.

Diverge : Generate many questions about your goal, wish or challenge. Phrase your questions beginning with: “How to…?” “How might…?” “What might be all the ways to…?” Try turning your key data into questions that redefine the goal, wish or challenge.

- Mark the “HITS” : New insight. Promising direction. Nails it! Feels good in your gut.

- Group the related “HITS” together.

- Restate the cluster . “How to…” “What might be all the…”

GENERATE IDEAS

Start here when you have a clearly defined problem and you need ideas to solve it. The best way to create great ideas is to generate LOTS of ideas. Defer judgment. Strive for quantity. Seek wild & unusual ideas. Build on other ideas.

Diverge : Come up with at least 40 ideas for solving your problem. Come up with 40 more. Keep going. Even as you see good ideas emerge, keep pushing for novelty. Stretch!

- Mark the “HITS”: Interesting, Intriguing, Useful, Solves the problem. Sparkles at you.

- Restate the cluster with a verb phrase.

DEVELOP SOLUTIONS

Start here when you want to turn promising ideas into workable solutions.

DEVELOP YOUR SOLUTION Review your clusters of ideas and blend them into a “story.” Imagine in detail what your solution would look like when it is implemented.

Begin your solution story with the phrase, “What I see myself doing is…”

PPCo EVALUATION

PPCo stands for Pluses, Potentials, Concerns and Overcome concerns

Review your solution story .

- List the PLUSES or specific strengths of your solution.

- List the POTENTIALS of your solution. What might be the result if you were to implement your idea?

- Finally, list your CONCERNS about the solution. Phrase your concerns beginning with “How to…”

- Diverge and generate ideas to OVERCOME your concerns one at a time until they have all been overcome

- Converge and select the best ideas to overcome your concerns. Use these ideas to improve your solution.

PLAN FOR ACTION

Start here when you have a solution and need buy-in from others. You want to create a detailed plan of action to follow.

Diverge : List all of the actions you might take to implement your solution.

- What might you do to make your solution easy to understand?

- What might you do to demonstrate the advantages of your solution?

- How might you gain acceptance of your solution?

- What steps might you take to put your solution into action?

Converge : Select the key actions to implement your solution. Create a plan, detailing who does what by when.

Credits for the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Creative Problem Solving – 21st Century is based on the work of: Osborn, A.F..(1953). Applied Imagination: Principles and procedures of Creative Problem Solving. New York: Scribner’s. Parnes, S.J, Noller, R.B & Biondi, A. (1977). Guide to Creative Action. New York: Scribner’s. Miller, B., Firestien, R., Vehar, J. Plain language Creative Problem-Solving Model, 1997. Puccio, G.J., Mance, M., Murdock, M.C. (2010) Creative Leadership: Skills that drive change. (Second Edition), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. Miller, B., Vehar J., Firestien, R., Thurber, S. Nielsen, D. (2011) Creativity Unbound: An introduction to creative process. (Fifth Edition), Foursight, LLC., Evanston, IL. PPC (Pluses, Potentials & Concerns) was invented by Diane Foucar-Szocki, Bill Shepard & Roger Firestien in 1982

Where to Go for More on Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Here are incredible free resources to ramp up on Creative Problem Solving 21st Century:

- PDF of Creative Problem Solving 21st Edition (RogerFirestien.com)

- PDF Worksheets for Creative Problem Solving (RogerFirestien.com)

- Video: Roger Firestien on 40 Years of Creative Problem Solving

Video Walkthroughs

- Video 1: Introduction to Creative Problem Solving

- Video 2: Identify your Goal/Wish/Challenge

- Video 3: Gather Data

- Video 4: Clarify the Problem: Creative Questions

- Video 5: Clarify the Problem: Why? What’s Stopping Me?

- Video 6: Selecting the Best Problem

- Video 7: How to do a Warm-up

- Video 8: Generate Ideas: Sticky Notes + Forced Connections

- Video 9: Generate Ideas: Brainwriting

- Video 10: Selecting the Best Ideas

- Video 11: Develop Solutions: PPCO

- Video 12: Generating Action Steps

- Video 13: Create Your Action Plan

- Video 14: CPS: The Whole Process

FourSight Thinking Profiles

The FourSight Thinking Skills Profile is an assessment tool designed to measure an individual’s thinking preferences and skills.

It focuses on four key thinking styles or stages that contribute to the creative problem-solving process.

The assessment helps individuals and teams understand their strengths and areas for development in each of these stages.

Why FourSight Thinking Profiles?

The FourSight method was necessary to address certain limitations or challenges that were identified in the original CPS method.

- Thinking Preferences : The FourSight model recognizes that individuals have different thinking preferences or cognitive styles. By understanding and leveraging these preferences, the FourSight method aims to optimize idea generation and problem-solving processes within teams and organizations.

- Overemphasis on Ideation : While ideation is a critical aspect of CPS, the original method sometimes focused too heavily on generating ideas without adequate attention to other stages, such as problem clarification, solution development, and implementation. FourSight offers a more balanced approach across all stages of the CPS process.

- Enhanced Problem Definition : FourSight places a particular emphasis on the Clarify stage, which involves defining the problem or challenge. This is an important step to ensure that the problem is well-understood and properly framed before proceeding to ideation and solution development.

- Research-Based Approach : The development of FourSight was influenced by extensive research on thinking styles and creativity. By incorporating these research insights into the CPS process, FourSight provides a more evidence-based and comprehensive approach to creative problem-solving.

Stages of FourSight Creative Problem Solving

FourSight Creative Problem Solving consists of four thinking stages, each associated with a specific thinking preference:

- Clarify : In this stage, the focus is on gaining a clear understanding of the problem or challenge. Participants define the problem statement, gather relevant information, and identify the key objectives and desired outcomes. This stage involves analytical thinking and careful examination of the problem’s context and scope.

- Ideate : The ideation stage involves generating a broad range of ideas and potential solutions. Participants engage in divergent thinking, allowing for a free flow of creativity and encouraging the exploration of unconventional possibilities. Various brainstorming techniques and creativity tools can be utilized to stimulate idea generation.

- Develop : Once a pool of ideas has been generated, the next stage is to develop and refine the selected ideas. Participants shift into a convergent thinking mode, evaluating and analyzing the feasibility, practicality, and potential impact of each idea. The emphasis is on refining and shaping the ideas into viable solutions.

- Implement : The final stage is focused on implementing the chosen solution. Participants develop an action plan, define specific steps and timelines, assign responsibilities, and identify the necessary resources. This stage requires practical thinking and attention to detail to ensure the successful execution of the solution.

Throughout the FourSight framework, it is recognized that individuals have different thinking preferences. Some individuals naturally excel in the Clarify stage, while others thrive in Ideate, Develop, or Implement.

By understanding these preferences, the FourSight framework encourages collaboration and diversity of thinking styles, ensuring a well-rounded approach to problem-solving and innovation.

The FourSight process can be iterative, allowing for feedback loops and revisiting previous stages as needed. It emphasizes the importance of open communication, respect for different perspectives, and leveraging the collective intelligence of a team to achieve optimal results.

4 Thinking Profiles in FourSight

In the FourSight model, there are four preferences that individuals can exhibit. These preferences reflect where individuals tend to focus their energy and time within the creative problem-solving process.

The four preferences in FourSight are:

- Clarifier : Individuals with a Clarifier preference excel in the first stage of the creative problem-solving process, which is about gaining clarity and understanding the problem. They are skilled at asking questions, gathering information, and analyzing data to define the problem accurately.