- Open access

- Published: 06 November 2018

Trends in repeated pregnancy among adolescents in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013

- Joemer C. Maravilla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5794-9565 1 , 2 ,

- Kim S. Betts 1 , 2 &

- Rosa Alati 1 , 2 , 3

Reproductive Health volume 15 , Article number: 184 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

65k Accesses

8 Citations

Metrics details

The extent of repeated pregnancy (RP) and repeated birth (RB) among adolescents aged 15–19 is still unknown in the Philippines despite the health and socio-economic consequences. This study aims to investigate the RP and RB prevalence trends in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013.

A total of 7091 women aged 15–24 who experienced at least one pregnancy were captured in the Philippine demographic health surveys from 1993 to 2013. Annual RP and RB prevalence per age group in three and five categories were calculated and stratified by region, type of residence and wealth index. Cochran–Armitage tests and multivariate logistic regression were applied to determine trend estimates.

Compared to women aged 19–21 years and 22–24 years, for which decreasing patterns were found, RP ([Adjusted Odds ratio (AOR =0.96; 95%Confidence interval (CI) =0.82–1.11) and RB (AOR = 0.90; CI = 0.73–1.10) trends among 15–18 year olds showed negligible reduction over the 20 years. From a baseline prevalence of 20.39% in 1993, the prevalence of RP among adolescents had only reduced to 18.06% by 2013. Moreover, the prevalence of RB showed a negligible decline from 8.49% in 1993 to 7.80% in 2013. Although RP and RB prevalence were generally found more elevated in poorer communities, no differences in trends were noted across wealth quintiles.

For two decades, the Philippines has shown a constant and considerably high RP prevalence. Further investigation, not only in the Philippines but also in other developing countries, is necessary to enable development of secondary prevention programs.

Peer Review reports

Plain English summary

Despite high and stable levels of adolescent fertility in the Philippines, no specific research has been conducted to specifically measure the trend and magnitude of repeated adolescent pregnancy, which is defined as an adolescent who has had at least two pregnancies. Repeated pregnancy, therefore needs to be investigated as it reflects not only the reproductive health of adolescent mothers but also disparities in service delivery of health, education and welfare support to adolescents after their first pregnancy.

We used the Philippine Demographic and Health Surveys to sample 7091 women aged 15–24 who experienced at least one pregnancy. Annual RP and RB prevalence per age group in three and five categories were calculated and stratified by region, type of residence and wealth quintile. Trends were statistically analysed using Cochran–Armitage tests and multivariate logistic regression.

While a decline was observed in 19–21 and 22–24 year olds, we found a constant prevalence of one in every five in 15–18 years old from 1993 to 2013. This trend was evident across all regions, types of residence and socio-economic status. Our analysis also found that those from the poorest wealth quintile demonstrated a heightened risk of repeated pregnancy compared to other quintiles. The non-decreasing prevalence trend of repeated pregnancy among adolescents indicated the need for secondary prevention programs particularly for the poorest households. Epidemiological investigations are also necessary to explore the causes and impact of repeated pregnancy on maternal, child and neonatal health, not only in the Philippines, but also among other low- and middle-income countries.

Introduction

The adolescent pregnancy epidemic in the Philippines has been acknowledged as one of the worst in the Western Pacific Region [ 1 ] with a recent prevalence of 13.6% among 15–19 year olds. The Philippines is the only country in this region with no significant decline in adolescent fertility in the past decades [ 2 ] from 56 per 1000 in 1973 to 57 per 1000 in 2013 [ 2 , 3 ]. In order to address this entrenched public health issue, preventive policies and programs have been implemented [ 4 , 5 ], and epidemiological studies have been developed to provide evidence of the current sexual health and behaviour of Filipino adolescents [ 6 ]. However, these measures have put little emphasis on the more serious problem of repeated adolescent pregnancies.

Repeated adolescent pregnancy, which is defined as a subsequent pregnancy among adolescents aged 10–19 years [ 7 ] is known to affect around 18% of adolescent mothers in the USA [ 7 ], Europe [ 8 ], and Australia [ 9 ]. Despite the evident chance of repeated adolescent pregnancy especially within 2 years postpartum [ 10 ], current research is unable to clearly establish its magnitude in developing countries such as the Philippines, nor how the trends have changed across time [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Although a World Health Organization (WHO) multi-country report [ 14 ] discussed the relationship between age and parity among Filipino adolescents, this study did not assess the prevalence of multi parity as its primary measure.

As a marker for adolescent reproductive health, repeated pregnancy reflects health disparities particularly among the disadvantaged adolescent population. Repeated pregnancy also indicates poor distribution and unequal access to reproductive health services [ 15 ] and inadequate service capacity of individual localities. It relates to low educational attainment, limited employment opportunities and poverty among adolescent mothers [ 15 , 16 ]. It has been shown that repeated adolescent pregnancy leads to an increase in national health and welfare expenditure as a consequence of the long-term dependency of adolescents and their families on government assistance [ 15 , 17 ].

An increasing trend of adolescent sexual activity [ 3 ] ongoing poor compliance with modern contraceptives [ 2 , 18 ] and inadequate use of family planning services all suggest that repeated adolescent pregnancy is highly prevalent in the Philippines [ 12 ]. Analysis of existing nationally representative data can be helpful in evaluating the extent of this public health problem. In this study, we aim to determine the prevalence of repeated pregnancies and births among adolescents and young adults from a series of national surveys conducted between 1993 and 2013. Moreover, we intend to analyze the trend of repeated pregnancies and births by age groupings and potential macro-level confounders across two decades, with resulting trends perhaps reflecting the effectiveness of existing policies and programs in addressing this under-recognized adolescent health problem.

Population and sample

This study used the Philippine Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) from 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2013 which are cross-sectional surveys conducted every 5 years. This nationally representative survey involved a multi-stage sampling design up to the household level with enumeration areas distributed by region and type of residence using the most recent national census as its sampling frame. All women in the selected households which includes adolescents aged 15–19 years and young adults aged 20–24 years were interviewed using the Individual Woman’s Questionnaire. This survey therefore excludes adolescents aged below 15 years. As shown in Appendix , the majority of the survey sample belonged to these age brackets which we will refer to as adolescents for the succeeding parts of this paper.

Outcome and socio-geographic measures

Repeated adolescent pregnancy/birth.

An adolescent aged 15–19 years was considered as having experienced repeated pregnancy (RP) if she had experienced at least two pregnancies, including current pregnancies, which either resulted in a live birth and/or pregnancy loss. A case of repeated birth (RB) was defined as an adolescent with at least two live births. These definitions were adapted from related review papers [ 8 ] and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [ 7 ].

Survey year was considered as a continuous variable in the analysis to measure the trend because of equal intervals between survey years. Thus, each unit increase in year variable translates to an actual five-year increase.

Respondents were categorized by age into three and five groups. The three age groups include “15–18” which considers the legal age of consent (18) in the Philippines, “19–21” as the transition period, and “22–24” as young adults [ 19 ]. In sensitivity analysis we further subdivided age into five groups (i.e. “15–16”, “17–18”, “19–20”, “21–22”, and “22–24”) to analyze in detail the trends per age.

Socio-geographic variables

Region refers to the three main island groups: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. We disaggregated and compared all estimates by region since each island group has unique geographical and cultural characteristics. Further disaggregation per administrative region was not pursued, as the number of administrative regions had increased during the 1998. Type of residence was either rural or urban area where the respondent resided at the time of the survey. Based on their household’s wealth score, adolescents were grouped into the household wealth quintiles “richest”, “richer”, “middle”, “poorer”, and “poorest” class.

We calculated the mean, standard deviation and prevalence rate of RP and RB per year per age group. RP prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of adolescents with RP and the number of adolescents who experienced at least one pregnancy (including those currently pregnant) multiplied by 100. RB prevalence on the other hand was calculated by dividing the number of adolescents with RB and the number of adolescents who experienced at least one livebirth multiplied by 100. Deformalized survey weights were applied while calculating the prevalence.

We used the ptrendi package in Stata13 to perform Cochran–Armitage tests to determine the prevalence trend per age group using the chi-square statistic and meeting the assumptions of an additive model. Cochran–Armitage test is a modified Pearson’s chi-square test which assesses the association between binary (i.e. RP and RB) and ordinal (i.e. year and age) categories. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with interaction effects for age (i.e. age groups using both three and five categories) and year was conducted while using repeated pregnancy and birth as binary outcome variables (i.e. yes or no). We measured the trend between two consecutive survey years to identify which periods had significant changes in prevalence. In addition, we analyzed trends using year and socio-geographic (i.e. region, type of residence, and wealth index) interaction per age group. For the purpose of this analysis, we used the three category age group as this was the only categorization which allowed a sufficient number of cases.

Among women aged 15–24 years with at least one pregnancy ( n = 7091), a large proportion (53.3%) were found among the 22–24 year olds. Despite the small proportion of adolescents captured by the surveys, the proportion of 15–18 year olds reported in the survey has increased over time from 7.64% ( n = 107) in 1993 to 15.55% ( n = 213) in 2013 ( see Table 1 ).

Trend analysis per age group

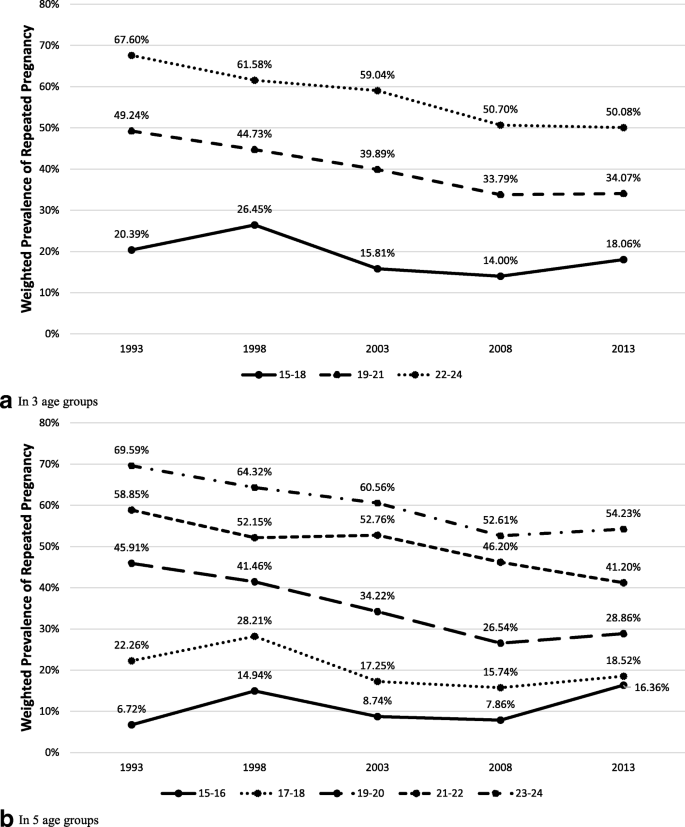

Cochran–Armitage tests showed an overall decrease in the trend of RP (Chi2 = 127.60; p < 0.001) across 20 years among the 15–24 years old from a weighted RP prevalence (WtPrev RP ) of 58.12% in 1993 to 40.58% in 2013. There was also a general RB (Chi2 = 100.90; p < 0.001) reduction from weighted RB prevalence (WtPrev RB ) of 51.25% to 35.66%. However, within age groupings this decline was not observed among 15–18 years olds. In Fig. 1 , we only found a slight decrease in RP prevalence from 20.39% in 1993 to 18.06% in 2013. RB prevalence also presented a minimal change with 0.69 decline among 15–18 and 0.80 decline among 17–18 years olds in this 20-year period ( see Fig. 2 ). Further observations among 17–18 years olds showed a similar RP trend from 22.26 to 18.52%.

Prevalence trends of adolescents with repeated pregnancy in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013 by age group. Caption: This figure presents the weighted prevalence of repeated pregnancy using age groups with ( a ) three and ( b ) five categories. Groups using the three categories include 15–18 years old, 19–21 years old and 22–24 years old while the five categories including 15–16 years old, 17–18 years old, 19–20 years old, 21–22 years old and 23–24 years old, as represented by each line on the graphs. The x-axis is the survey year arranged in chronological order while the y-axis the weighted prevalence

Prevalence trends of adolescents with repeated birth in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013 by age group. Caption: This figure presents the weighted prevalence of repeated birth using age groups with ( a ) three and ( b ) five categories. Groups using the three categories include 15–18 years old, 19–21 years old and 22–24 years old while the five categories including 15–16 years old, 17–18 years old, 19–20 years old, 21–22 years old and 23–24 years old, as represented by each line on the graphs. The x-axis is the survey year arranged in chronological order while the y-axis the weighted prevalence

Similar results were found in the regression analysis. The RP trend among 15–18 year olds remained virtually unchanged across all surveys from 1993 to 2013 [Odds ratio (OR) =0.93; 95% Confidence interval (CI) =0.81–1.07]. There was a similar pattern of RB trend in this age group (OR = 0.87; CI = 0.72–1.06) following an apparent increase in prevalence from 1993 to 1998 (OR = 3.29; CI = 1.25–8.62). On the other hand, the older age groups showed a significant decline both for RP and RB with unadjusted ORs ranging from 0.83 to 0.87 ( see Table 2 ). Analyses using five age categories showed no significant difference in the trends previously described. Trends among 15–16 and 17–18 year old adolescents remained unchanged, whereas a decreasing trend was apparent for those aged 19–20, 21–22 and 23–24.

Adjustments for regions, types of residence and wealth quintile suggested that the trends were not confounded by these factors across all age groups. Interestingly, wealth index was strongly associated with RP and RB as adolescents from the poorest quintile had shown higher odds in reference to richest quintile (OR RP = 5.41, CI = 4.31–6.78; OR RB = 5.36, CI = 4.17–6.89). Calculation of weighted prevalence confirmed this association with a WtPrev RP of 59.60% and WtPrev RB of 52.50%.

Change of prevalence between two consecutive survey years was also analyzed using the three age categories. We found that there was a decrease in RP prevalence among 15–18 from 1998 to 2003 (OR = 0.52; CI = 0.28–0.99), and among 22–24 from 1993 to 1998 (OR = 0.77; CI = 0.61–0.97) and 2003–2008 (OR = 0.71; CI = 0.58–0.88). A drop in RB prevalence was also found among 15–18 from 1998 to 2003 (OR = 0.32; OR = 0.13–0.81); and among 22–24 from 1993 to 1998 (OR = 0.74; CI = 0.58–0.93).

Trend per socio-geographic variable per age group

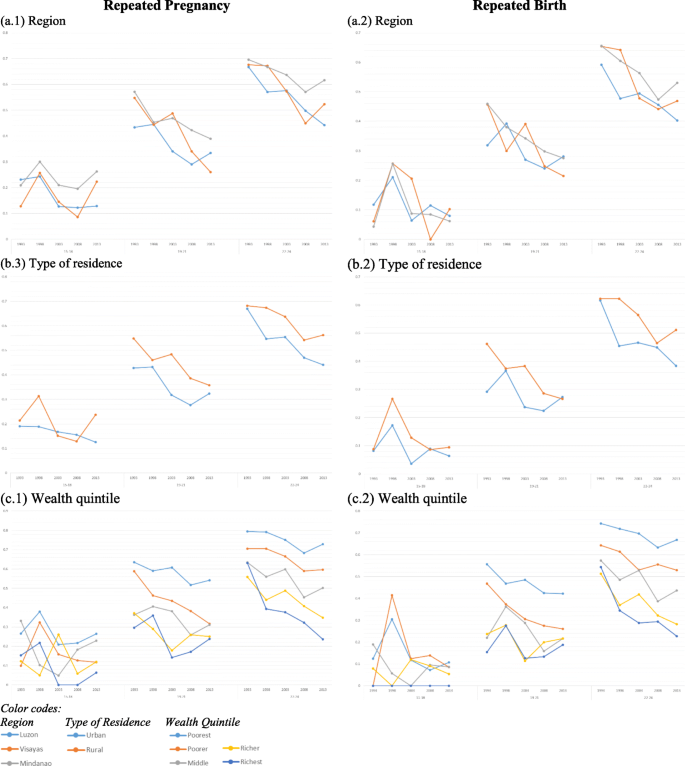

The constant RP trend among 15–18 and the decreasing RP trend among 22–24 were found in all regions, types of residence and wealth quintiles ( see Table 3 ) . On the other hand, the decline of RP decline among 19–21 was only consistent across regions and types of residence. Only the poorer households showed a 20-year reduction when compared to the other four quintiles.

A similar pattern was observed for RB trend among those aged between 15 and 18 and 22–24. Unlike RP, the trend for RB among 19–21 year olds was inconsistent across the three socio-geographic variables. The decreasing trend was only found in Visayas and Mindanao region, rural communities, and poor wealth quintiles (see Fig. 3 ) .

Prevalence trend of repeated pregnancies and births among adolescents per socio-geographic variable in each age group. Caption: This figure presents the trend of the weighted prevalence of repeated pregnancies and births in each of the socio-graphic variable using the three age categories: 15–18 years old, 19–21 years old and 22–24 years old. The left column presents the weighted prevalence of repeated pregnancy while the right column presents repeated birth. In each graph, the x-axis is the survey year arranged in chronological order while the y-axis the weighted prevalence. The color of each line represents a category of each socio-geographic variable as shown at the bottom of the graph

In each age group, we also conducted adjusted Wald tests to measure the difference of trend estimates between the categories of each socio-geographic variable. No differences were observed for 15–18. For 19–21, differences were only found between the RP trend estimates of poorest and poorer quintiles, and between the RB trend estimates rural and urban communities. For 22–24, differences between the trend estimates of poorest and richest, and between poorer and richest were found both for RP and RB.

Discussions

Despite the declining trends of RP and RB in older age groups, the prevalence among adolescents younger than 18 years showed no decrease across 20 years of data, remaining stable across all regions, types of residence, and wealth quintiles. The prevalence was high with approximately one in every five adolescents aged 15–18 years with a history of pregnancy experiencing RP while one in every ten of those who had a livebirth experienced RB.

While the decreasing RP and RB trend among young adults can likely be attributed to their improved contraceptive use [ 20 ] and awareness of and participation in family planning (FP) strategies [ 3 , 21 ]. The unchanged trend among adolescents may result from the unique socio-cultural characteristics and FP policies in the Philippines, wherein adolescents are prevented from accessing FP services, even after their first pregnancy. One of the possible explanations for this finding is that the strong influence of the Catholic church at the local level may have affected the health seeking behavior and the implementation of reproductive health programs among adolescents [ 22 , 23 ].

Unclear and restricted health and health-related policies for adolescent mothers may also play a role. The initial adolescent health policy in the Philippines [ 24 ], which aimed to reduce unwanted pregnancies and provide adolescent-friendly health services, did not include strategies for dealing with the prevention of secondary pregnancies [ 25 , 26 ]. This may have led to adolescents being discouraged to access essential health information and use birth control methods [ 23 , 27 ].

Despite emphasizing the importance of health promotion and behavioral change, a recently introduced national law (Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012 or RH Law) and framework [ 4 ], did not embrace specific programmatic actions to address RP. The RH Law still prevents minors (i.e. below 18 years old) from accessing modern methods of contraception without parental consent and does not exempt adolescent mothers and adolescents who experienced miscarriage [ 28 ]. This policy restriction has already been found as a deterrent for adolescents to access contraceptives and counselling services in a review of evidence from 16 developing countries [ 29 ]. This study suggests that despite the availability of contraception, most of these developing countries retain barriers and restrictions towards the use of birth control methods, particularly among unmarried adolescents. In the context of this social and political environment, the RP/RB trends showed in this paper can be expected to continue for several years to come not only in the Philippines but also in other developing countries.

The role and reach of secondary prevention programs must be clarified due to the limited access to appropriate postnatal services (e.g. contraception, counselling, and educational support) for adolescent mothers. Health workers may also need to be trained to address the unique psychosocial characteristics and support the challenging developmental transition of very young mothers by enhancing adolescents’ readiness and decision-making abilities to delay another pregnancy and/or use modern family planning methods. Given the high rate of unmet need for modern contraception among married adolescents [ 21 ], policy initiatives/reforms such as providing exemption on contraception to adolescent mothers may be needed to achieve a reduction in the trend seen in this paper.

Our findings also suggest that prevention programs aimed at those from the poorest quintile may be warranted due to the high RP/RB prevalence among this group. In the Philippines and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), attempts to reach out to households from the poorest sector have been undertaken through the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) Program [ 30 , 31 ]. For example, the CCT program in Mexico has been found to indirectly reduce adolescent pregnancy and increase contraceptive use among adolescents and young adults [ 31 ]. The potential of cash incentive schemes can also be used as an opportunity to monitor and provide prevention programs to adolescent mothers, particularly within 24 months after their first pregnancy [ 10 ].

Our study uniquely explores the status of repeated pregnancy and birth in LMICs in the Asia-pacific Region. Most published reports on this topic are primarily from the USA, Europe, and Australia [ 32 ]. Of the few reports identified from LMICs, many used birth order (i.e. 2nd order or higher) and a different denominator (i.e. total number of adolescents) in the computation of prevalence. Despite the availability of possible data sources among LMICs [ 33 ], few studies have attempted to look specifically at the distribution of adolescents and young adults with RP/RB. Most of the reports available may include vital statistics which is limited to those only with livebirths and does not necessarily account for previous unsuccessful pregnancies.

By placing RP as an issue of crucial importance to the public health especially of LMICs, our paper makes a significant contribution to the literature calling for improvement of sexual and reproductive health of adolescents. The Global Strategy for Adolescent Health for 2030 recognized childbirth and pregnancy complications as one of the two leading causes of death among 15–19 year old girls [ 34 ]—addressing RP would help to reduce this. The absence of a reduction in RP trend over 20 years that we identified, signals the need for secondary prevention programs in line with WHO recommendations [ 35 ].

This study finds strength in our use of nationally-representative individual datasets instead of aggregate estimates. This prevents the risk of producing results affected by the ecological fallacy, particularly in the analysis of year-age interaction. Furthermore, we were able to perform more thorough analyses such as the adjustment of trend estimates for confounders (i.e. wealth quintile, region, and type of residence).

Limitations

Our study also has limitations. Recall bias and under-reporting are likely to produce bias in any surveys covering information of a sensitive nature. Insufficient record validation is common across the DHS surveys from all countries. However, the DHS’ survey procedure enables cross-checking through repeated questions during the interview to reduce the effect of this validation issue. Additionally, our findings may not be comparable to longitudinal studies from developed countries that defined RP as an adolescent who became pregnant within 12–24 months of her first pregnancy/ delivery.

Future research

In addition to cross-sectional analyses that measure RP prevalence, epidemiological investigations are needed to explore the causes and outcomes of RP. Studies conducted in LMICs may identify different associations and dynamics due to the psychosocial and cultural characteristics of and attitudes towards adolescent mothers in these countries. This type of study not only directs the development of specialized perinatal care, and psychosocial and welfare support but also places priority on those adolescents with RP.

A multi-country analysis would also be beneficial in obtaining a broader RP status especially in countries with similar characteristics. This would help international organizations to implement immediate action for RP in a global approach and prioritize countries with a high RP burden. Additionally, projection of RP prevalence at least until 2030 using country-level determinants such as contraceptive prevalence, poverty, literacy, and maternal-child mortality rates, may facilitate target setting for this potential adolescent reproductive health indicator.

There is a constant trend of one in every five adolescent mothers in the Philippines experiencing repeated pregnancy from 1993 to 2013 (across all regions, type of residence, and socio-economic status). These findings indicate the need for secondary prevention programs, particularly among the poorest households. Epidemiological investigations are also necessary to explore the causes and impacts of repeated pregnancy on maternal, child, and neonatal health in the Philippines and other low- and middle-income countries.

Abbreviations

Conditional Cash Transfer

95% Confidence Interval

Demographic and Health Survey

Family planning

Low- and middle-income countries

Repeated birth

Repeated Pregnancy

World Health Organization

Weighted RB prevalence

Weighted RP prevalence

World Health Organization-Western Pacific Region. Fact Sheet on Adolescent Health. 2015; http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/docs/fs_201202_adolescent_health/en/ . Accessed June 30, 2015, 2015.

Google Scholar

UNFPA, UNESCO and WHO. Sexual and Reproductive Health of young people in Asia and the Pacific: A review of issues, policies and programmes. Bangkok: UNFPA; 2015.

Philippine Statistics Authority, and ICF International. Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Manila, Philippines, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Philippine Statistics Authority, and ICF International; 2014.

Department of Health-Philippines. In: Health Do, editor. National policy and strategic framework on adolescent health and Development. Philippines: Department of Health; 2013.

Department of Health-Philippines. Behavior change communication strategies for preventing preventing adolescent pregnancy. Philippines: Department of Health; 2012. https://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/SourcebookBCCStrategiesPreventingAdolescentPregnancy.pdf . Accessed 19 Feb 2016.

Natividad J. Teenage pregnancy in the Philippines: trends, correlates and data sources. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2013;28(1):30–7.

Gavin L, Warner L, O'Neil ME, et al. Vital signs: repeat births among teens - United States, 2007-2010. Mmwr-Morbid Mortal W. 2013;62(13):249–55.

Rowlands S. Social predictors of repeat adolescent pregnancy and focussed strategies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;24(5):605–16.

Article Google Scholar

Lewis LN, Doherty DA, Hickey M, Skinner SR. Predictors of sexual intercourse and rapid-repeat pregnancy among teenage mothers: an Australian prospective longitudinal study. Med J Aust. 2010;193(6):338–42.

PubMed Google Scholar

Stevens-Simon C, Kelly L, Singer D, Nelligan D. Reasons for first teen pregnancies predict the rate of subsequent teen conceptions. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):E8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Capanzana MV, Aguila DV, Javier CA, Mendoza TS, Santos-Abalos VM. Adolescent pregnancy and the first 1000 days (the Philippine situation). Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24(4):759–66.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hussain R, Finer L. Unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion in the Philippines: context and consequences. In Brief. 2013;3 https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/ib-unintended-pregnancy-philippines.pdf . Accessed 15 June 2018.

Salvador JT, Sauce BRJ, Alvarez MOC, Rosario AB. The phenomenon of teenage pregnancy in the Philippines. Eur Scientific J. 2016;12(32).

Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, et al. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:40–8.

Association of Maternal & Child Health Programs. Life course indicator: Repeat teen Birth Life course indicator online tool 2014; http://www.amchp.org/programsandtopics/data-assessment/LifeCourseIndicatorDocuments/LC-54%20Teen%20Births_Final-9-10-2014.pdf . Accessed February 12, 2016.

Penman-Aguilar A, Carter, M., Snead, M. C., Kourtis, A. P. Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Vol 1282013.

National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Counting it up: The public costs of teen childbearing. 2014; https://thenationalcampaign.org/resource/public-costs-teen-childbearing-united-states . Accessed August 22, 2014.

Guttmacher Institute. Sexual and reproductive health of young women in the Philippines: 2013 data Update 2015.

Knoll LJ, Magis-Weinberg L, Speekenbrink M, Blakemore S-J. Social influence on risk perception during adolescence. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(5):583–92.

Melgar JD, Melgar AR, Cabigon JV. Family Planning in the Philippines. In: Zaman W, Masnin H, Loftus J, editors. Family Planning in Asia & the Pacific: Addressing the Challenges. Malaysia: International Council on Management of Population Programmes; 2012. http://icomp.org.my/FP%20in%20Asia%20and%20the%20Pacific%20Jan%202012.pdf .

Demographic Research and Development Foundation, and University of the Philippines Population Institute. 2013 YAFS4 Key Findings. Quezon City, Philippines: Demographic Research and Development Foundation, and University of the Philippines Population Institute; 2014.

Ogena NA. Development concept of adolescence: the case of adolescents in the Philippines. Philipp Popul Rev. 2014;3(1).

Varga CA, Zosa-Feranil I. Adolescent reproductive health in the Philippines: status, policies, programs, and issues. Washington, DC: The Futures Group International, POLICY Project; 2003.

Department of Health-Philippines. Adolescent & Youth Health (AYH) policy. Manila: Department of Health; 2000.

Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, Singh S. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):223–30.

Corcoran J, Pillai VK. Effectiveness of secondary pregnancy prevention programs: a meta-analysis. Res Soc Work Pract. 2007;17(1):5–18.

Pogoy AM, Verzosa R. Coming NS, Agustino RG. Lived experiences of early pregnancy among teenagers: a phenomenological study. Eur Scientific J. 2014;10(2).

Government of the Philippines. Republic act no. 10354: An act providing for a national policy on responsible parenthood and reproductive healthy on responsible parenthood and reproductive health. In: Gazette-Philippines. 2012; Document number:10534. http://www.gov.ph/2012/12/21/republic-act-no-10354/ .

Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health 2014;11(1):1.

World Bank. Philippines conditional cash transfer program : impact evaluation 2012. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013.

Darney BG, Weaver MR, Sosa-Rubi SG, et al. The Oportunidades conditional cash transfer program: effects on pregnancy and contraceptive use among young rural women in Mexico. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013;39(4):205–14.

Maravilla, JC, Betts, KS, Couto e Cruz, C, and Alati, R. Factors influencing repeated teenage pregnancy: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 217(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.02 .

Gray N, Azzopardi P, Kennedy E, Willersdorf E, Creati M. Improving adolescent reproductive health in Asia and the Pacific. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;25(2):134–44.

Every Woman Every Child Strategy and Coordination Group. Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health 2016-2030. Italy: United Nations; 2015.

Chandra-Mouli V, Camacho AV, Michaud P-A. WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):517.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We also acknowledge the Demographic and Health Surveys Program for allowing us to access the all Philippine DHS datasets. This study was presented at the 15th World Congress on Public Health, Australia, April 3–7, 2017.

This study was supported by the University of Queensland International Scholarship.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but can be requested from the DHS Program data managers.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health, The University of Queensland, Herston, QLD, Australia

Joemer C. Maravilla, Kim S. Betts & Rosa Alati

Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland, Indooroopilly, QLD, Australia

Centre for Youth Substance Abuse Research, The University of Queensland, Herston, QLD, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JM conceptualized the study design, prepared the datasets, conducted the analysis, and drafted and revised the manuscript. KB conceptualized the study design, conducted the analysis, and revised the manuscript. RA conceptualized the study design, supervised the data analysis, and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joemer C. Maravilla .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study underwent an expedited review and was approved by the University of Queensland – School of Public Health Ethics Committee on April 11 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maravilla, J.C., Betts, K.S. & Alati, R. Trends in repeated pregnancy among adolescents in the Philippines from 1993 to 2013. Reprod Health 15 , 184 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0630-4

Download citation

Received : 25 September 2017

Accepted : 21 October 2018

Published : 06 November 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0630-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Repeat Pregnancy (RP)

- Wealth Quintile

- Secondary Prevention Programs

- Cochran-Armitage Test

- Repeat Births (RB)

Reproductive Health

ISSN: 1742-4755

- General enquiries: [email protected]

< Back to my filtered results

Education, earnings and health effects of teenage pregnancy in the Philippines

This paper examines the effect of teenage pregnancy (early childbearing) on education and lifetime earnings using data from national surveys. It finds that the discounted lifetime wage earnings foregone by a cohort of teenage women 18-19 years resulting from early childbearing is estimated between 24 billion pesos and 42 billion pesos with mean of 33 billion pesos, representing from 0.8% to 1.4% of GDP with mean of 1.1%.

Teenage Pregnancy in the Philippines: Trends, Correlates and Data Sources

Josefina natividad.

Results from cumulative years of the National Demographic and Health Survey and the latest result of the 2011 Family Health Survey, shows that teenage pregnancy in the Philippines, measured as the proportion of women who have begun childbearing in their teen years, has been steadily rising over a 35-year period. These teenage mothers are predominantly poor, reside in rural areas and have low educational attainment. However, this paper observes a trend of increasing proportions of teenagers who are not poor, who have better education and are residents of urban areas, who have begun childbearing in their teens. Among the factors that could help explain this trend are the younger age at menarche, premarital sexual activity at a young age, the rise in cohabiting unions in this age group and the possible decrease in the stigma of out-of-wedlock pregnancy.

Key words: teenage pregnancy, early childbearing, age at menarche

Women’s age-specific fertility rates [*] follow a characteristic pattern. Soon after menarche, the fertility rate starts at a low level, peaks at ages 20-29, then declines until it stops completely following menopause. The optimal ages for successful pregnancy are in the peak reproductive years. At either end of the reproductive spectrum, that is at the youngest (below 20) and the oldest (40 and above) ages, there is a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Studies have shown that at age 35 and over, and especially at 45 and over, women are more likely to experience gestational diabetes, placenta previa, breech presentation and operative vaginal delivery than younger women aged 20-29. Other observed complications that are more prevalent among older mothers compared to mothers in their twenties are preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, cesarean delivery, abruptio placenta and preterm delivery. 1

Similarly, when the woman is at the younger extreme of the reproductive age spectrum, below 20 years, pregnancy carries the same elevated risk of adverse outcomes. 2 Many studies consistently show that teenage mothers are at increased risk of pre-term delivery and low birth weight. 3-6 From a large data base of births in the Latin American Center for Perinatology and Human Development in Uruguay, it was found that after adjusting for major confounding factors, women age 15 and younger were at increased risk for maternal death, early neonatal death and anemia compared with women age 20-24. Furthermore, women aged less than 20 had higher risk for postpartum hemorrhage, puerperal endometritis, operative vaginal delivery, low birth weight, pre-term delivery and small for gestational age infants. 7 The same elevated risks for teenage pregnancies, independent of known major confounders like low socioeconomic status, inadequate prenatal care and inadequate weight gain during pregnancy were documented using data from the 1995-2000 nationally linked birth/infant death data set of the United States compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 8 In developing countries where no large data bases exist, evidence from smaller samples show similar results indicating that the risks are not specifically linked to the level of development of a country’s health care system and the availability of appropriate maternal care for very young pregnant women, 4 but are specific to the age group and its accompanying implication of biological immaturity for childbearing. The risks follow an age gradient; they are generally higher at the younger end of the teenage years and diminish toward the latter teen years.

Teenage pregnancy carries other significant non-health risks which are specific to this stage in the life course. 9

For example, when a teenager bears a child and consequently either marries formally or enters into a consensual union, she puts herself at risk of not finishing her education 10-11

and of limiting her chances of realizing her full potential by being burdened with child care when she herself is still, almost a child. If the teenager remains unmarried following a pregnancy, she risks social stigma from having an out-of-wedlock pregnancy and of having to bear its negative consequences. 12

At the aggregate level, a high teenage pregnancy rate contributes to high population growth as teenage mothers will have considerably longer exposure to the risk of pregnancy than those who enter into marital unions at a later age.

Teenage pregnancy has two aspects, and both could occur concurrently within the same country, whether developed or developing. On the one hand, high teenage pregnancy rates may result from the culturally sanctioned practice of early marriage and early marital childbearing, and on the other, from premarital intercourse and unintended pregnancy. Research evidence points to a shift in behaviors among young people in patterns of sexual activity such that early childbearing is becoming more a consequence of early intercourse. This is more often true in urban than in rural areas. 13 Additionally, a downward trend in the age at menarche in both developed and developing countries has been reported in a number of studies. 14-16 Zabin and Kiragu (1998) in their review report a connection between age of onset of sexual activity or age at first birth and age at menarche resulting in earlier onset of childbearing for the current generation of teenagers compared with earlier cohorts. 17

Because of the increased risks to both mother and child of too early childbearing, there is a need to understand the situation on teenage pregnancy in any country in order to design appropriate interventions. But obtaining reliable and valid data for analysis is not always easy, especially in a developing country.

This paper consists of two parts: the first discusses data sources for the study of teenage pregnancy in general; the second part presents trends in teenage pregnancy in the Philippines, some correlates and an analysis of the drivers for the observed trend using a specific data source. We will use data from the National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) conducted in the Philippines at 5-year intervals since 1968. The NDHS surveys are part of the DHS program of surveys that are highly regarded for methodological soundness and rigor in the design and conduct of data collection. With a common research design and questionnaire adopted throughout all the surveys in the series, NDHS data lends itself well to the analysis of long term trends in teenage pregnancy in the Philippines.

Data for the study of levels, trends, determinants and consequences of teenage pregnancy are usually derived from varied sources and using a wide range of data collection methods. Studies on the consequences of early childbearing, particularly the risk of adverse outcomes normally use hospital-based records, using either prospective or retrospective designs. For example, completed charts on births occurring in a hospital over a given period can be the source of information for studying pregnancy outcomes, as these will normally contain basic demographic information: the mother’s age, the pregnancy order as predictor variables and factors like maternal complications, placental complications, medications administered in hospital and neonatal outcomes as outcome indicators. 2 The advantage of these data sets is that they provide reliable and valid reports on the pregnancy outcomes under study using medically accepted diagnostic criteria and are not based on the teenage mother’s self-report. The main disadvantage is possible misclassification by age if there is reason for the mother to conceal her true age. If such a bias exists, it is likely to be higher in the younger adolescent than the older adolescent years as it may be less socially acceptable to have a birth at age 12 or 13 than at 18 or 19. Background variables on the mother that can serve as explanatory factors may also be limited; some will record education but socioeconomic status is normally not included in hospital records. As a data source for determining the total number of teenage pregnancies, hospital-based records are not reliable as these cover only hospital-based births. In most developing countries, majority of births occur in non-hospital settings.

To determine the level of teenage pregnancy in a given country, one potential data source is the Vital Registration System, which collects vital statistics such as births, death and marriages in the population. Usually, the national government requires that these vital events are officially reported through birth registration, death registration and marriage registration. In the Philippines, recording these events is the main duty of Local Civil Registrars. In some developed countries, there is a separate perinatal statistics collection system based on data collected by midwives and other health practitioners for each live and still birth which takes place in hospital and for home births. 18 The vital registration system is an ideal way to capture the level of teenage pregnancy year-on-year because it is a continuing record of births as they occur. Unfortunately, most vital registration systems especially in developing countries are hobbled by problems of underreporting and incompleteness. For example, it is estimated that in 2000, the level of completeness of birth registration in the Philippines was 78 percent, i.e., only 78 per cent of 5-year-olds at the time of the survey have been registered in the birth registry (have a birth certificate, whether or not it was physically with the household at the time of the survey) [†] . There is also a marked disparity among regions in the Philippines in the completeness of birth registration, with the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao registering the lowest level of completeness of birth registration.

Even when vital registry data effectively capture all births in its reporting system, the type of information contained in birth registration forms will still be unable to answer many questions that will help understand fertility and its determinants better. Sample surveys fill in this gap. The most commonly accepted alternative source of data for estimating teenage pregnancy and investigating its correlates are nationally representative surveys of women in the reproductive years (15-49), extracting the relevant data for women aged 15-19 in the sample. Respondent to these surveys are the women themselves.

There have been a number of recent publications from the World Health Organization, USAID and other international groups providing guidelines for the conduct of ethical research when the subjects are children and adolescents. Among the recommendations are procedures for securing informed consent from parents/guardians when the subject is a minor [‡] . The recommended practice respects country-specific customs and traditions and may waive the requirement for written parental consent and accept alternative procedures for documenting consent that are appropriate to the local setting. 22-23 In the field of survey research on fertility at all ages including the teenage years, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program funded by USAID and implemented by ORC- Macro has been the gold standard.

DHS data are publicly available and easily downloadable hence are commonly used in many cross-country comparisons. In the Philippines, the National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) seriesis the major data source on long-term trends in teenage pregnancy and its determinants. The surveys are undertaken in the Philippines by the National Statistics Office in collaboration with the Department of Health and ORC Macro. 24-25 The sample of women in the reproductive years is representative at the national and regional levels. The NDHS follows a standard protocol for obtaining informed consent from survey respondents.

In the succeeding analysis of teenage pregnancy in the Philippines, we use mainly the NDHS survey results from various survey dates. For the long term trend in the age-specific fertility rate at ages 15-19, we use NDHS data from 1973 to 2008. For the analysis of determinants we refer to the survey results from 1993 to 2008 NDHS. Other data sources on correlates of teenage pregnancy cited in this paper are the Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality surveys of 1994 (YAFS 2) and 2002 (YAFS 3) and the 2011 Family Health Survey (FHS). YAFS is a series of surveys on young adults aged 15-24 gathering information on sexual and non-sexual risk behaviors and its correlates while the 2011 FHS is the latest round of what used to be known as the Family Planning Survey (FPS) series, also covering women age 15-49 as does the NDHS, but mostly focused in scope on family planning. Since 2006, the FPS has incorporated a complete birth history for measuring fertility and infant child mortality and a special module to collect information for estimating maternal mortality.

Survey data from both the NDHS Series and the 2011 FHS supports findings of other studies from other countries about the elevated risk of early neonatal deaths among teenage mothers (Table 1).

Click here to download Table 1

Table 1. Neonatal and infant mortality rate for the 10-year period preceding the survey

Neonatal and infant mortality tend to be higher at both ends of the reproductive spectrum, i.e., the youngest (less than 20) and the oldest (aged 45-49) age groups. Teenage mothers also compare poorly with mothers from the older age groups in a number of reproductive health indicators. For one, they tend to have the shortest birth intervals (Figure 1) of all age groups. Taking into account the fact that their bodies are not yet ready for the physical demands of childbearing, having closely spaced births exposes young mothers to further health risks.

Still, having closely spaced births is not necessarily a matter of choice for these young mothers as implied by the finding from the 2003 and 2008 NDHS and the 2011 FHS that currently married women aged less than 20 have the highest unmet need for contraception (Figure 2). For example, in the 2011 FHS, 37 percent of currently married 15-19 year olds had an unmet need for contraception, mostly for spacing of births, compared to 19 percent for all currently married women. This is an indication that adolescent mothers are an underserved segment of reproductive health programs and services.

Click here to download Figure 1

Figure 1. Median number of months since preceding birth

Click here to download Figure 2

Figure 2. Percent of women with unmet need for family planning

The WHO reports that about 16 million adolescent girls aged 15-19 give birth each year, roughly 11% of all births worldwide. Almost 95% of these births occur in developing countries. The adolescent fertility rate worldwide was estimated to be 55.3 per thousand for the 2000-2005 period, meaning that on average about 5.5% of adolescents give birth each year. In the Philippines, according to the latest Vital Statistics Report released by the National Statistics Office, in 2008 a total 1,784,316 births were registered; of these 10.4%, (186,527 births) were born to mothers under 20 years of age. Total registered births in 2008 increased by 2% from the previous year’s 1,749,878 births while births to teenage mothers increased by 7.6 %, from 173,282 in 2007. Assuming the same level of underreporting for teenage births as for total births, a comparison of the percent increase of total births and births to teenage mothers suggests that fertility has a faster pace in the youngest reproductive ages.

To get further insight into how the fertility at the youngest reproductive age group compares with that of later years, Figure 3 shows the long-term trend in fertility rates at three age groups, the youngest (15-19), the peak reproductive years (25-29) and the oldest reproductive group (45-49) over a 35-year period.

Click here to download Figure 3

Figure 3. Age-specific fertility rates for women aged 15-19, 25-29 and 45-49, 1973 to 2008 NDHS

Over this period, there has been a dramatic decrease in the fertility rate at the largest and the oldest reproductive age groups, accounting in large measure for the decline in the total fertility rate [§] [**] of the Philippines from 6.0 children in 1973 to 3.3 in 2008. In 1973, there were 302 births per thousand women aged 25-29; by 2008 this has dropped considerably to 172. Similarly, in 1973, there were 28 births per thousand women aged 45-49 dropping dramatically to only 6 births per thousand women in 2008. But, amidst these declining rates in the reproductive ages above 20, the 35-year trend indicates that the fertility rate in the 15-19 age group has remained virtually unchanged, from 56 births per thousand women in 1973 to 54 in 2008.

Compared with the rest of the world, the Philippines’ adolescent fertility rate is within the average range. Compared with its neighbors in Southeast Asia, it is also mid-range, at the same level as Indonesia, but higher than Thailand and Vietnam (Figure 4). Despite anecdotal reports to the contrary, the adolescent fertility rate has not changed significantly in four decades.

The age-specific fertility rate (ASFR) for women 15-19 is a measure of the incidence of fertility; it is the rate of births relative to the person years of exposure to the risk of childbearing within the given age group. It is highly possible for one woman to contribute more than one birth to the numerator as the reference period is usually about five years before the survey date. Therefore, for purposes of gauging the level of early childbearing in the population, the ASFR is not a good measure.

In place of the ASFR at 15-19, a more appropriate gauge of early childbearing is the proportion of women in the age group who are pregnant/who have become mothers. 12,26,27 Unlike the ASFR, in this measure a woman can only be counted once. The proportion of women who have already given birth at a certain age is a measure of the timing of first birth and is an indicator of how early child bearing has begun in the population.

Source: World Health Organization ( http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.310?lang=en accessed 15 April 2013)

Click here to download Figure 4

Figure 4. Adolescent Fertility Rate in Selected Southeast Asian Countries

Figure 5 presents the trend in the proportion who have begun childbearing at 15-19 over a 15-year period based on the 1993-2008 NDHS. The measure is further broken down into a younger (15-17) and older group (18-19).

Figure 4 shows that the proportion of 15-19 year olds who have begun childbearing has been steadily rising, from about 7 percent in 1998 to 10 percent in 2008. The increase is steeper among the older teens (18-19) but there is a 100 percent increase among the younger teens, from 2 per hundred in 1993 to 4 per hundred in 2008. Overall, the picture presented in this figure is that the proportion of teenagers who have who have begun childbearing is higher in 2008 than in 1993. Thus by this measure, we can conclude that indeed more women are getting pregnant or have become mothers in their teens nowadays than in the past and that the picture depicted by the age-specific fertility rate is a misleading one when describing the trend in teenage pregnancy.

Click here to download Figure 5

Figure 5. Percent who have begun childbearing, 1993-2008 NDHS

The question to ask now is, “Does early childbearing occur equally in all segments of the young female population or does it occur more often in some subgroups than others?” Three factors are usually cited as sources of variability in teenage pregnancy rates in any population. Across countries, teenage pregnancy tends to be more prevalent in rural areas, among women with low education and among the poor.

To investigate the situation in the Philippines, the next set of figures presents the same longitudinal trend broken down by rural-urban residence, educational attainment and socioeconomic status (as measured by the wealth index [††] ). Those who had no formal schooling are excluded in the analysis because they comprise a very small proportion of the sample population

In terms of residence, Figure 6 shows that the percent who have begun childbearing at 15-19 is generally higher in rural than in urban areas but the percent change from 1993 to 2008 is higher in the urban (62.5 percent) than in the rural (40.4 percent). In both areas the proportions who have become mothers has been steadily increasing in the 15-year reference period.

Click here to download Figure 6

Figure 6. Percent who have begun childbearing by rural-urban residence, 1993 to 2008 NDHS

By educational attainment (Figure 7) there is a clear education gradient in early childbearing but while teenagers with elementary level schooling have the highest proportions who have become mothers, the trend shows no consistent pattern of increase through the years. The rise in early childbearing is more pronounced among those with high school and college education where the trend shows a persistent upward climb for each survey round. The upsurge is especially pronounced among those with college education with the increase in early childbearing from 1993 to 2008, a striking 290 percent change.

Figure 8 compares early childbearing across the wealth quintiles with the first quintile representing the poorest 20% of the women (based on the status of their household) and the fifth quintile the richest 20%. Only two data points are compared because only the 2003 and 2008 NDHS rounds had available information to compute the wealth index. The results indicate a gradient of difference by socioeconomic status similar to that observed with educational attainment, which is to be expected as these two variables are highly correlated, i.e., those with the lowest education will tend to be among the poorest. Overall, early childbearing is most prevalent among women in the poorest (first and second) quintiles. Comparing the 2003 and 2008 data it appears that the prevalence of early childbearing did not change much for women from a high prevalence level in the two lowest quintiles (in fact it decreased among the poorest teenagers) but definitely increased for the higher quintiles (3 rd , 4 th and 5 th ).

Click here to download Figure 7

Figure 7. Percent who have begun childbearing by educational attainment, 1993-2008 NDHS

Click here to download Figure 8

Figure 8. Percent who have begun childbearing by wealth quintile, 2003 and 2008 NDHS

The comparison of differences in early childbearing across residence, education and socioeconomic status of the adolescent suggest a changing pattern in early childbearing. Not only has the percentage who have become mothers in their teens been increasing, but the composition of these teenage mothers has been changing. The transition has moved from being mostly rural, poor and with the lowest educational attainment toward an increasing proportion of urban residents, better educated and those from the middle to the richest socioeconomic groups have likewise commenced childbearing in the teenage years.

What could be driving this trend of early childbearing among all groups in society? As stated earlier, this could be a result of early marriage or of premarital sexual activity leading to pregnancy or to both. To investigate which of these two factors could account for the change, we compare the 1993 to 2008 marital status of teenagers categorized as never married, married, living together and separated. Married refers to those who are formally in a marital union, living together refers to those who are in a consensual union and have not formally married.

Click here to download Figure 9

Figure 9. Marital status of women aged 15-19, 1993 to 2008 NDHS

Figure 9 shows that from the 1993 NDHS, 92 percent of teenagers were never married. This proportion has consistently declined through the years and in the 2008 NDHS, only 89 percent of teenagers were never married. If early marriage was driving the trend toward higher prevalence of early childbearing, the proportion married should correspondingly increase with the decline in the proportion never married. Figure 9 show that the proportion who are married has been declining. What is steadily on the rise is the proportion in a consensual union. This suggests that it is early premarital sexual activity that is the driver for the trend toward the increasing prevalence of early childbearing in the Philippines. Pregnancy resulting from premarital sexual activity often leads to the decision to begin cohabitation but not necessarily to a formalized marital union. Corroborating evidence for this shift toward non-marital fertility among teenage women is found in the vital statistics report of the National Statistics Office which states that in 2008 “Majority (79.2 %) of babies born to women under 20 (years) of age were illegitimate.” [‡‡] Illegitimate means that the mother and father were not formally married at the time the birth was registered. The trend toward non-marital fertility is by no means limited to the youngest women. The Vital Statistics Report for 2008 further states that of the total births registered in 2008, 37.5 percent were born out of wedlock and 40 percent of illegitimate births were born to mothers in the age group 20-24.

Evidence for early premarital sexual activity is further supported by findings from two surveys on a national representative sample of young people aged 15-24 in the Philippines, the Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study done in 1994 (YAFS 2) and in 2002 (YAFS 3). In YAFS 2, 8 percent of 15-19 year olds reported ever having engaged in premarital sex; this increased in 2002 to 12 percent. Only 24 percent used contraception during their first premarital sexual activity. 28 Since YAFS was conducted more than a decade ago, presumptive changes in prevalent sexual behaviors and practices of young people may have undoubtedly contributed to the increasing proportion of teenage girls becoming mothers at a very early age.

Another contributory factor to the increasing prevalence of early childbearing is the decreasing age at menarche, a development that is consistently reported in the literature as occurring in countries that have experienced significant improvements in living conditions and the nutritional status of female children. Table 2 presents the reported age at menarche by women in the various reproductive age groups.

Click here to download Table2

Table 2. Percent distribution of age at menarche by age at time of the survey, 2008 NDHS

Table 2 indicates that the reported age at menarche has been declining across successive cohorts of women. For example, among the 15-19 year olds, the reported age at menarche peaks at age 12 (31%) while among the 45-49 year olds the peak is at 15 and above (30.7%). This trend in consistent with that reported in the literature about the deceasing trends in the age at menarche in other developed and developing countries. 29

Overall, the findings in this paper from the analysis of the Philippines’ National Demographic and Health Survey series over a number of years, together with findings from the Family Health Survey, corroborates that more teenagers now are getting pregnant compared to earlier cohorts. A confluence of factors have come together to make this happen: a trend toward younger age at menarche, changing norms and practices with regard premarital sexual activity among the youth and increasing acceptance of premarital sex coupled with less societal pressure to legitimize out-of-wedlock pregnancies. Although there are differences amongst groups, the increasing prevalence of early childbearing is observed in all socioeconomic classes, all levels of education and in both urban and rural settings.

Teenage pregnancy exposes both mother and child to many health and other risks, both and there is need to further study how to mitigate its effects or how to reverse the trend. Any interventions should be cognizant of the following factors:

1. While early childbearing has increased among the non-poor, the better educated and residents of urban areas, teenage pregnancy is still unacceptably higher among the poor, those with lower education and rural residents. Interventions designed to help reverse the trend should be tailored to the circumstances leading to early pregnancy that may be specific to these subgroups.

2. The timing of school-based interventions such as sexuality education should be mindful of the finding that teenage pregnancy is highest among those with the least education, specifically those with elementary or lower educational attainment. Thus age-appropriate sexuality education should begin in the pre-adolescent years before teenagers leave school. The high unmet need for contraception among currently cohabiting or married teens, requires specific services and family planning programs for this group. Teenage mothers have the lowest birth intervals (median of less than 24 months) and expose themselves and any more babies to greater risks if a subsequent pregnancy is not prevented. The fact that there is high unmet need for contraception in this age group indicates that there is a desire to space births longer but for some reason the expressed desire is not matched by the corresponding action of using contraception for birth spacing (Figure 2). Further studies should investigate barriers to the use of contraception among currently married teenagers as no direct answers are available from either the NDHS or the FHS.

3. Hospital-based prospective and retrospective studies to study the adverse outcomes of early pregnancy and childbirth on the mother and her baby compared to other age groups are needed to better understand the specific health risks in the Philippine setting. Findings of these studies will be an important input for intervention programs not only for the teenagers themselves, but also for health providers who will be involved in the delivery of services for this age group.

1. Kenny LC, Lavender T, McNamee R, O'Neill SM, Mills T et al.Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: Evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(2): e56583. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056583.

2. Chantrapanichkul P, Chawanpaiboon S. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in cases involving extremely young maternal age. International Journal of Gynaecological Obstetrics,. 2013, Feb 120(2): 160-4. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.08.024.

3. Gordon CS, Smith S and Pell JP. Teenage pregnancy and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes associated with first and second births: Population based retrospective control study. British Medical Journal, 2001, Vol 323,

4. Kurth F. et al. Adolescence as risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome in Central Africa - A fross-sectional Study. PLoS ONE, 2010, 5(12) e14367.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014367.

5. Suwal A. Obstetric and perinatal outcome of teenage pregnancy. J Nepal Health Res Counc, 2012;10 (20):52-6.

6. Eure CR, Lindsay MK, Graves WL. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in young adolescent parturients in an inner-city hospital. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2002; 186 (5):918-20.

7. Conde-Agudelo A, Beliza JM and Lammers C. Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2005;192, 342–9.

8. Chen XK et al. Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: A large population based retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 2007, 36:368–373 doi:10.1093/ije/dyl284.

9. Hindin, MJ and Fatusi, AO. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2009, Volume 35,Number 2, 58-62.

10. Field, E, and Ambrus, A. Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy , 2008, 116(5): 881-930.

11. Klepinger D, Lundberg S and Plotnick R. Adolescent fertility and the educational attainment of young women. Family Planning Perspectives, 1995, Vol 27, No.1;23-28.

12. Singh S. Adolescent childbearing in developing countries: A global review. Studies in Family Planning, 1998, Vol. 29, No. 2, Adolescent Reproductive Behavior in the Developing World , 117-136.

13. Gardner R and Blackburn R. People who move: New reproductive health focus. Population Reports J, 1996, No. 45. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Population Information Program.

14. Malina RM, Pena Reyes ME, Tan SK, Little BB. Secular change in age at menarche in rural Oaxaca, southern Mexico: 1968–2000 . Annals of Human Biology, 2004;31(6) 634-646

15. Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, De Meeus T and G JF. International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: Patterns and main determinants. Human Biology, 2001;73, ( 2) 271-290.

16. Babay ZA, Addar MH, Shahid K, Meriki N. Age at menarche and the reproductive performance of Saudi women. Ann Saudi Med, 2004, 24(5)

17. Zabin LS and Kiragu K. The health consequences of adolescent sexual and fertility behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 1998, 29,(2), 210-232

18. Slowinski K and Hume A. Unplanned teenage pregnancy and the support needs of young mothers Part C: Statistics. Unplanned teenage pregnancy research project – Statistics Department of Human Services, South Australia, 2001.

19. Singer E. Risk, benefit, and informed consent in survey research. Survey Research, 2004, vol 35, no 2-3, 1-6.

20. Singer E. Informed consent: Consequences for response rate and response quality in social surveys. American Sociological Review,1978, 43, 144-162.

21. Singer E. Exploring the meaning of consent. Participation in research and beliefs about risks and benefits. Journal of Official Statistics, 2003. 19, 273-286.

22. Adetunji JA and Shelton JD. Ethical issues in the collection, Analysis and dissemination of DHS data in sub- Saharan Africa. Bureau for Global Health, USAID, (n.d.).

23. Schenk K and Williamson J. Ethical approaches to fathering information from children and adolescents in international settings: Guidelines and Resources. Washington, DC: Population Council, 2005.

24. National Statistics Office (NSO) Philippines and ICF Macro National Demographic and Health Survey 2008 . Calverton, Maryland: National Statistics Office and ICF Macro, 2009.

25. National Statistics Office (NSO) Philippines and ICF Macro. National Demographic and Health Survey 2003 . Calverton, Maryland: National Statistics Office and ICF Macro, 2004.

26. Neal S, Matthews Z, Frost M, Fogstad H, Camacho AV, Laski L. (2012) Childbearing in adolescents aged 12–15 in low resource countries: A neglected issue. New estimates from demographic and household surveys in 42 countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2012, 91:1114–1118.

27. Westoff CF. Trends in marriage and early childbearing in developing countries. DHS Comparative Reports No. 5 Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro, 2003

28. Natividad JN and Marquez MP. Sexual risk behaviors. In Raymundo, CM and Cruz, GT (eds.) Youth and Sex Risk Behaviors in the Philippines: A Report on the Nationwide Study 2002 Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study (YAFS3). Demographic Research and Development Foundation, Inc and University of the Philippines Population Institute. Diliman, Quezon City, 2004.

29. Onland-Moret NC et al. Age at menarche in relation to Adult height The EPIC Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2005;162, (7), 623-632 .

*The age-specific fertility rate is the number of births per thousand women of a given age or age group. An age-specific fertility rate is generally computed as a ratio. The numerator is the number of live births to women in a particular age group during a period of time, and the denominator is an estimate of the number of person-years lived by women in that same age group during the same period of time. It is expressed as births per 1,000 women.

Source: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WFR2009_Web/ Data/Meta_Data/ASFR.pdf. Retrieved 7 May 2013

[†] http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators/SP.REG.BRTH.RU.ZS/ compare?country=ph#country=pg:pe:ph:th. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

[‡] [‡] The practice of securing written informed consent for surveys is a matter of ongoing debate in the social science survey community as the practice has been shown to affect participation rates and may compromise the validity of the research findings Please cite references number 20 and 21 here.

[**] The total fertility rate is a basic indicator of the level of fertility. It is calculated by summing age-specific fertility rates over all reproductive ages. It may be interpreted as the expected number of children a woman who survives to the end of the reproductive age span will have during her lifetime if she experiences the given age-specific rates.

Source: http://data.un.org/Glossary.aspx?q=total+fertility+rate. Retrieved 7 May 2013

[††] The wealth index is a composite measure of a household's cumulative living standard. It is calculated using easy-to-collect data on a household’s ownership of selected assets, such as televisions and bicycles; materials used for housing construction; and types of water access and sanitation facilities. It divides households into five quintiles, with quintile 1 representing the poorest 20 % and quintile 5 the richest 20%.

(Measure DHS. http://www.measuredhs.com/ topics/Wealth-Index.cfm Accessed 15 April 2013).

[‡‡] http://www.census.gov.ph/article/registered-live-births-increased-20-percent-20082012-08-16-1700

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2015

Early motherhood: a qualitative study exploring the experiences of African Australian teenage mothers in greater Melbourne, Australia

- Mimmie Claudine Ngum Chi Watts 1 ,

- Pranee Liamputtong 2 &

- Celia Mcmichael 3

BMC Public Health volume 15 , Article number: 873 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

170k Accesses

62 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Motherhood is a significant and important aspect of life for many women around the globe. For women in communities where motherhood is highly desired, motherhood is considered crucial to the woman’s identity. Teenage motherhood, occurring at a critical developmental stage of teenagers’ lives, has been identified as having adverse social and health consequences. This research aimed to solicit the lived experiences of African Australian young refugee women who have experienced early motherhood in Australia.

This qualitative research used in-depth interviews. The research methods and analysis were informed by intersectionality theory, phenomenology and a cultural competency framework. Sixteen African born refugee young women who had experienced teenage pregnancy and early motherhood in Greater Melbourne, Australia took part in this research. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and data analysed using thematic content analysis. Ethics approval for this research was granted by Victoria University Human Research Ethics committee.

Motherhood brings increased responsibilities, social recognition, and a sense of purpose for young mothers. Despite the positive aspects of motherhood, participants faced challenges that affected their lives. Most often, the challenges included coping with increased responsibilities following the birth of the baby, managing the competing demands of schooling, work and taking care of a baby in a site of settlement. The young mothers indicated they received good support from their mothers, siblings and close friends, but rarely from the father of their baby and the wider community. Participants felt that teenage mothers are frowned upon by their wider ethnic communities, which left them with feelings of shame and embarrassment, despite the personal perceived benefits of achieving motherhood.

Conclusions

We propose that service providers and policy makers support the role of the young mothers’ own mother, sisters, their grandmothers and aunts following early motherhood. Such support from significant females will help facilitate young mothers’ re-engagement with education, work and other aspects of life. For young migrant mothers, this is particularly important in order to facilitate settlement in a new country and reduce the risk of subsequent mistimed pregnancies. Service providers need to expand their knowledge and awareness of the specific needs of refugee teen mothers living in ‘new settings’.

Peer Review reports

Globally, teenage pregnancy remains a public health concern. Worldwide, sixteen million girls give birth during adolescence annually with an estimated three million having unsafe abortions. Most adolescent pregnancies occur in developing countries, and teenagers living in socio-economically disadvantaged settings in developed countries are at higher risk of teenage pregnancy as compared to the broader population [ 1 ]. The adolescent period is considered a critical time in the young person’s life. Initiation of sexual activities, and for many a marriage, occur during this period. The early onset of sexual intercourse and menarche and the delay in marriage means the period of adolescent is now longer than ever, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy and early motherhood. During the teenage years, young people who are faced with early motherhood may experience conflict between their new position as mothers and their adolescent needs [ 1 , 2 ]. The experiences of early motherhood are contextual, influenced by culture and the society within which the teenager/woman lives [ 1 – 6 ].