Home — Essay Samples — History — American History — Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

- Categories: American History

About this sample

Words: 749 |

Published: Sep 1, 2023

Words: 749 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical context: fear and paranoia, experiences in internment camps: resilience amid adversity, enduring impact on communities: seeking justice, lessons for the present and future, conclusion: remembering the past, shaping a just future.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1123 words

3 pages / 1356 words

2 pages / 757 words

6 pages / 2599 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American History

America's history has played a significant role in shaping the nation's identity and influencing global events. From the colonial era to the modern age, the United States has experienced pivotal moments and undergone [...]

The War of 1812, fought between the United States and Great Britain, is often overshadowed by the American Revolution and the Civil War. However, it had significant impacts on the United States that affected its political, [...]

The Stamp Act of 1765 is a landmark event in American history that played a crucial role in shaping the nation's path toward independence. This essay explores the historical context, significance, and consequences of the Stamp [...]

In the annals of American history, few individuals have a legacy as intricate and profound as George Mason. As one of the founding fathers, Mason’s contributions to the shaping of American democracy and the establishment of [...]

Shortly after the horrific events of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the lives of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Japenese people, both aliens and Citizens of the United States, would be changed in some major ways. Executive [...]

The early settlement of Jamestown in 1607 marked a pivotal moment in American history, as it was the first permanent English settlement in North America. This essay will explore the challenges faced by the Jamestown settlers and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Top of page

Collection Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers, 1942 to 1946

Articles and essays.

American Incarceration

A Smithsonian magazine special report

The Injustice of Japanese-American Internment Camps Resonates Strongly to This Day

During WWII, 120,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into camps, a government action that still haunts victims and their descendants

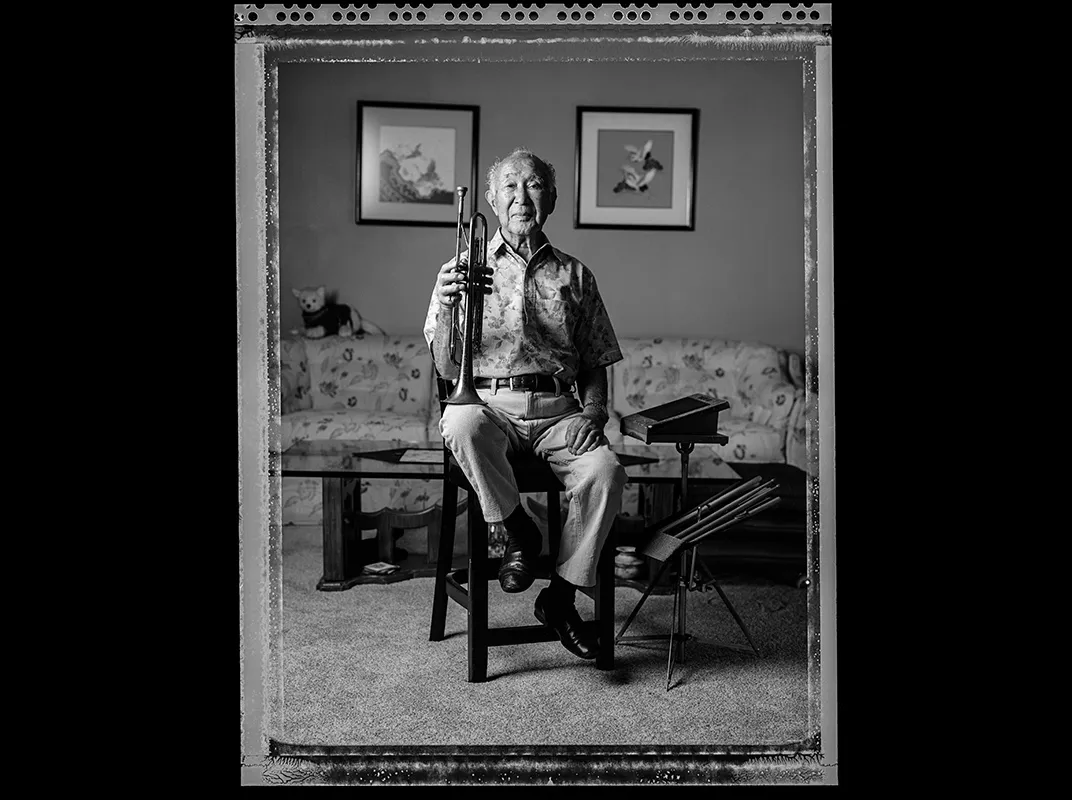

T.A. Frail; Photographs by Paul Kitagaki Jr.; Historical Photographs by Dorothea Lange

Jane Yanagi Diamond taught American History at a California high school, “but I couldn’t talk about the internment,” she says. “My voice would get all strange.” Born in Hayward, California, in 1939, she spent most of World War II interned with her family at a camp in Utah.

Seventy-five years after the fact, the federal government’s incarceration of some 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent during that war is seen as a shameful aberration in the U.S. victory over militarism and totalitarian regimes. Though President Ford issued a formal apology to the internees in 1976, saying their incarceration was a “setback to fundamental American principles,” and Congress authorized the payment of reparations in 1988, the episode remains, for many, a living memory. Now, with immigration-reform proposals targeting entire groups as suspect, it resonates as a painful historical lesson.

The roundups began quietly within 48 hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941. The announced purpose was to protect the West Coast. Significantly, the incarceration program got underway despite a warning; in January 1942, a naval intelligence officer in Los Angeles reported that Japanese-Americans were being perceived as a threat almost entirely “because of the physical characteristics of the people.” Fewer than 3 percent of them might be inclined toward sabotage or spying, he wrote, and the Navy and the FBI already knew who most of those individuals were. Still, the government took the position summed up by John DeWitt, the Army general in command of the coast: “A Jap’s a Jap. They are a dangerous element, whether loyal or not.”

That February, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, empowering DeWitt to issue orders emptying parts of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona of issei—immigrants from Japan, who were precluded from U.S. citizenship by law—and nisei, their children, who were U.S. citizens by birth. Photographers for the War Relocation Authority were on hand as they were forced to leave their houses, shops, farms, fishing boats. For months they stayed at “assembly centers,” living in racetrack barns or on fairgrounds. Then they were shipped to ten “relocation centers,” primitive camps built in the remote landscapes of the interior West and Arkansas. The regime was penal: armed guards, barbed wire, roll call. Years later, internees would recollect the cold, the heat, the wind, the dust—and the isolation.

There was no wholesale incarceration of U.S. residents who traced their ancestry to Germany or Italy, America’s other enemies.

The exclusion orders were rescinded in December 1944, after the tides of battle had turned in the Allies’ favor and just as the Supreme Court ruled that such orders were permissible in wartime (with three justices dissenting, bitterly). By then the Army was enlisting nisei soldiers to fight in Africa and Europe. After the war, President Harry Truman told the much-decorated, all-nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team: “You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice—and you have won.”

If only: Japanese-Americans met waves of hostility as they tried to resume their former lives. Many found that their properties had been seized for nonpayment of taxes or otherwise appropriated. As they started over, they covered their sense of loss and betrayal with the Japanese phrase Shikata ga nai —It can’t be helped. It was decades before nisei parents could talk to their postwar children about the camps.

Paul Kitagaki Jr., a photojournalist who is the son and grandson of internees, has been working through that reticence since 2005. At the National Archives in Washington, D.C., he has pored over more than 900 pictures taken by War Relocation Authority photographers and others—including one of his father’s family at a relocation center in Oakland, California, by one of his professional heroes, Dorothea Lange. From fragmentary captions he has identified more than 50 of the subjects and persuaded them and their descendants to sit for his camera in settings related to their internment. His pictures here, published for the first time, read as portraits of resilience.

Jane Yanagi Diamond, now 77 and retired in Carmel, California, is living proof. “I think I’m able to talk better about it now,” she told Kitagaki. “I learned this as a kid—you just can’t keep yourself in gloom and doom and feel sorry for yourself. You’ve just got to get up and move along. I think that’s what the war taught me.”

Subject interviews conducted by Paul Kitagaki Jr.

Related Reads

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

T.A. Frail | READ MORE

Tom Frail is a senior editor for Smithsonian magazine. He previously worked as a senior editor for the Washington Post and for Philadelphia Newspapers Inc.

Paul Kitagaki Jr. | READ MORE

Paul Kitagaki Jr. is a senior photographer at The Sacramento Bee . His work has won numerous awards, including a shared Pulitzer Prize in 1990.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Life in the camps

- An American promise

What was the internment of Japanese Americans?

Where were japanese american internment camps, why were japanese americans interned during world war ii, what was life like inside japanese american internment camps, what was the cost of japanese american internment.

Japanese American internment

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- HistoryNet - Japanese Internment Camps: America’s Great Mistake

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - The Japanese American Wartime Incarceration: Examining the Scope of Racial Trauma

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Holocaust Encyclopedia - Japanese American Relocation

- National Park Service - A brief history of Japanese American Relocation during World War II

- GlobalSecurity.org - World War II Japanese American Internment

- Academia - Landscapes of Japanese American Internment

- Japanese American internment - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Japanese American internment - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Japanese American internment was the forced relocation by the U.S. government of thousands of Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II , beginning in 1942. The government’s action was the culmination of its long history of racist and discriminatory treatment of Asian immigrants and their descendants that boiled over after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor .

Japanese American internment camps were located mainly in western U.S. states. The first internment camp in operation was Manzanar , located in California. Between 1942 and 1945 a total of 10 camps were opened, holding approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans for varying periods of time in California , Arizona , Wyoming , Colorado , Utah , and Arkansas .

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor , the U.S. War Department suspected that Japanese Americans might act as espionage agents for Japan , despite a lack of evidence. John J. McCloy , the assistant secretary of war, who oversaw the internment program, prioritized national security over civil liberties expressed in the Constitution . He justified his actions by saying he considered the Constitution “just a scrap of paper.”

Conditions at Japanese American internment camps were spare, without many amenities. The camps were ringed with barbed-wire fences and patrolled by armed guards, and there were isolated cases of internees being killed. Generally, however, camps were run humanely. Residents established a sense of community, setting up schools, newspapers, and more, and children played sports. Learn more.

The cost of internment to Japanese Americans was great. Because they were given so little time to settle their affairs before being shipped to internment camps , many were forced to sell their houses, possessions, and businesses well below market value to opportunistic Euro-Americans. When released, many Japanese Americans had very little to return to except discrimination .

Recent News

Japanese American internment , the forced relocation by the U.S. government of thousands of Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II . That action was the culmination of the federal government’s long history of racist and discriminatory treatment of Asian immigrants and their descendants that had begun with restrictive immigration policies in the late 1800s.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese aircraft on December 7, 1941, the U.S. War Department suspected that Japanese Americans might act as saboteurs or espionage agents, despite a lack of hard evidence to support that view. Some political leaders recommended rounding up Japanese Americans, particularly those living along the West Coast, and placing them in detention centres inland. A power struggle erupted between the U.S. Department of Justice , which opposed moving innocent civilians, and the War Department , which favoured detention. John J. McCloy , the assistant secretary of war, remarked that if it came to a choice between national security and the guarantee of civil liberties expressed in the Constitution , he considered the Constitution “just a scrap of paper.” In the immediate aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack, more than 1,200 Japanese community leaders were arrested, and the assets of all accounts in the U.S. branches of Japanese banks were frozen.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, approximately 125,000 Japanese Americans lived on the mainland in the United States . About 200,000 immigrated to Hawaii , then a U.S. territory. Some were first-generation Japanese Americans, known as Issei , who had emigrated from Japan and were not eligible for U.S. citizenship. About 80,000 of them were second-generation individuals born in the United States ( Nisei ), who were U.S. citizens. Whereas many Issei retained their Japanese character and culture , Nisei generally acted and thought of themselves as thoroughly American.

In early February 1942, the War Department created 12 restricted zones along the Pacific coast and established nighttime curfews for Japanese Americans within them. Individuals who broke curfew were subject to immediate arrest . The nation’s political leaders still debated the question of relocation, but the issue was soon decided. On February 19, 1942, Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , which gave the U.S. military authority to exclude any persons from designated areas. Although the word Japanese did not appear in the executive order , it was clear that only Japanese Americans were targeted, though some other immigrants, including Germans, Italians, and Aleuts , also faced detention during the war. On March 18, 1942, the federal War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established. Its mission was to “take all people of Japanese descent into custody, surround them with troops, prevent them from buying land, and return them to their former homes at the close of the war.”

On March 31, 1942, Japanese Americans along the West Coast were ordered to report to control stations and register the names of all family members. They were then told when and where they should report for removal to an internment camp . (Some of those who survived the camps and other individuals concerned with the characterization of their history have taken issue with the use of the term internment , which they argue is used properly when referring to the wartime detention of enemy aliens but not of U.S. citizens, who constituted some two-thirds of those of Japanese extraction who were detained during the war. Many of those who are critical of the use of internment believe incarceration and detention to be more appropriate terms.) Japanese Americans were given from four days to about two weeks to settle their affairs and gather as many belongings as they could carry. In many cases, individuals and families were forced to sell some or all of their property, including businesses, within that period of time.

Some Euro-Americans took advantage of the situation, offering unreasonably low sums to buy possessions from those who were being forced to move. Many homes and businesses worth thousands of dollars were sold for substantially less than that. Nearly 2,000 Japanese Americans were told that their cars would be safely stored until they returned. However, the U.S. Army soon offered to buy the vehicles at cut-rate prices, and Japanese Americans who refused to sell were told that the vehicles were being requisitioned for the war.

After being forcibly removed from their homes, Japanese Americans were first taken to temporary assembly centres. From there they were transported inland to the internment camps (critics of the term internment argue that these facilities should be called prison camps ). The first internment camp in operation was Manzanar , located in east-central California . Between 1942 and 1945 a total of 10 camps were opened, holding approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans for varying periods of time in California, Arizona , Wyoming , Colorado , Utah , and Arkansas .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Japanese Internment Camps

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 17, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066 . From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, would be incarcerated in isolated camps. Enacted in reaction to the Pearl Harbor attacks and the ensuing war, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is considered one of the most atrocious violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the stated intention of preventing espionage on American shores.

Military zones were created in California, Washington and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Executive Order 9066 affected the lives about 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens.

Canada soon followed suit, forcibly removing 21,000 of its residents of Japanese descent from its west coast. Mexico enacted its own version, and eventually 2,264 more people of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from Peru, Brazil, Chile and Argentina to the United States.

Anti-Japanese American Activity

Weeks before the order, the Navy removed citizens of Japanese descent from Terminal Island near the Port of Los Angeles.

On December 7, 1941, just hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI rounded-up 1,291 Japanese American community and religious leaders, arresting them without evidence and freezing their assets.

In January, the arrestees were transferred to prison camps in Montana, New Mexico and North Dakota, many unable to inform their families and most remaining for the duration of the war.

Concurrently, the FBI searched the private homes of thousands of Japanese American residents on the West Coast, seizing items considered contraband.

One-third of Hawaii’s population was of Japanese descent. In a panic, some politicians called for their mass incarceration. Japanese-owned fishing boats were impounded.

Some Japanese American residents were arrested and 1,500 people—one percent of the Japanese population in Hawaii—were sent to prison camps on the U.S. mainland.

Photos of Japanese American Relocation and Incarceration

John DeWitt

Lt. General John L. DeWitt, leader of the Western Defense Command, believed that the civilian population needed to be taken control of to prevent a repeat of Pearl Harbor.

To argue his case, DeWitt prepared a report filled with known falsehoods, such as examples of sabotage that were later revealed to be the result of cattle damaging power lines.

DeWitt suggested the creation of the military zones and Japanese detainment to Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Attorney General Francis Biddle. His original plan included Italians and Germans, though the idea of rounding-up Americans of European descent was not as popular.

At Congressional hearings in February 1942, a majority of the testimonies, including those from California Governor Culbert L. Olson and State Attorney General Earl Warren , declared that all Japanese should be removed.

Biddle pleaded with the president that mass incarceration of citizens was not required, preferring smaller, more targeted security measures. Regardless, Roosevelt signed the order.

War Relocation Authority

After much organizational chaos, about 15,000 Japanese Americans willingly moved out of prohibited areas. Inland state citizens were not keen for new Japanese American residents, and they were met with racist resistance.

Ten state governors voiced opposition, fearing the Japanese Americans might never leave, and demanded they be locked up if the states were forced to accept them.

A civilian organization called the War Relocation Authority was set up in March 1942 to administer the plan, with Milton S. Eisenhower from the Department of Agriculture to lead it. Eisenhower only lasted until June 1942, resigning in protest over what he characterized as incarcerating innocent citizens.

Relocation to 'Assembly Centers'

Army-directed removals began on March 24. People had six days notice to dispose of their belongings other than what they could carry.

Anyone who was at least 1/16th Japanese was evacuated, including 17,000 children under age 10, as well as several thousand elderly and disabled residents.

Japanese Americans reported to "Assembly Centers" near their homes. From there they were transported to a "Relocation Center" where they might live for months before transfer to a permanent "Wartime Residence."

Assembly Centers were located in remote areas, often reconfigured fairgrounds and racetracks featuring buildings not meant for human habitation, like horse stalls or cow sheds, that had been converted for that purpose. In Portland, Oregon , 3,000 people stayed in the livestock pavilion of the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Facilities.

The Santa Anita Assembly Center, just several miles northeast of Los Angeles, was a de-facto city with 18,000 incarcerated, 8,500 of whom lived in stables. Food shortages and substandard sanitation were prevalent in these facilities.

Life in 'Assembly Centers'

Assembly Centers offered work to prisoners with the policy that they should not be paid more than an Army private. Jobs ranged from doctors to teachers to laborers and mechanics. A couple were the sites of camouflage net factories, which provided work.

Over 1,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans were sent to other states to do seasonal farm work. Over 4,000 of the incarcerated population were allowed to leave to attend college.

Conditions in 'Relocation Centers'

There were a total of 10 prison camps, called "Relocation Centers." Typically the camps included some form of barracks with communal eating areas. Several families were housed together. Residents who were labeled as dissidents were forced to a special prison camp in Tule Lake, California.

Two prison camps in Arizona were located on Native American reservations, despite the protests of tribal councils, who were overruled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Each Relocation Center was its own "town," and included schools, post offices and work facilities, as well as farmland for growing food and keeping livestock. Each prison camp "town" was completely surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

Net factories offered work at several Relocation Centers. One housed a naval ship model factory. There were also factories in different Relocation Centers that manufactured items for use in other prison camps, including garments, mattresses and cabinets. Several housed agricultural processing plants.

Violence in Prison Camps

Violence occasionally occurred in the prison camps. In Lordsburg, New Mexico , prisoners were delivered by trains and forced to march two miles at night to the camp. On July 27, 1942, during a night march, two Japanese Americans, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot and killed by a sentry who claimed they were attempting to escape. Japanese Americans testified later that the two elderly men were disabled and had been struggling during the march to Lordsburg. The sentry was found not guilty by the army court martial board.

On August 4, 1942, a riot broke out in the Santa Anita Assembly Center, the result of anger about insufficient rations and overcrowding. At California's Manzanar War Relocation Center , tensions resulted in the beating of Fred Tayama, a Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) leader, by six men. JACL members were believed to be supporters of the prison camp's administration.

Fearing a riot, police tear-gassed crowds that had gathered at the police station to demand the release of Harry Ueno. Ueno had been arrested for allegedly assaulting Tayama. James Ito was killed instantly and several others were wounded. Among those injured was Jim Kanegawa, 21, who died of complications five days later.

At the Topaz Relocation Center , 63-year-old prisoner James Hatsuki Wakasa was shot and killed by military police after walking near the perimeter fence. Two months later, a couple was shot at for strolling near the fence.

In October 1943, the Army deployed tanks and soldiers to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California to crack down on protests. Japanese American prisoners at Tule Lake had been striking over food shortages and unsafe conditions that had led to an accidental death in October 1943. At the same camp, on May 24, 1943, James Okamoto, a 30-year-old prisoner who drove a construction truck, was shot and killed by a guard.

Fred Korematsu

In 1942, 23-year-old Japanese-American Fred Korematsu was arrested for refusing to relocate to a Japanese prison camp. His case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where his attorneys argued in Korematsu v. United States that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment .

Korematsu lost the case, but he went on to become a civil rights activist and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998. With the creation of California’s Fred Korematsu Day, the United States saw its first U.S. holiday named for an Asian American. But it took another Supreme Court decision to halt the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Mitsuye Endo

The prison camps ended in 1945 following the Supreme Court decision, Ex parte Mitsuye Endo . In this case, justices ruled unanimously that the War Relocation Authority “has no authority to subject citizens who are concededly loyal to its leave procedure.”

The case was brought on behalf of Mitsuye Endo, the daughter of Japanese immigrants from Sacramento, California. After filing a habeas corpus petition, the government offered to free her, but Endo refused, wanting her case to address the entire issue of Japanese incarceration.

One year later, the Supreme Court made the decision, but gave President Truman the chance to begin camp closures before the announcement. One day after Truman made his announcement, the Supreme Court revealed its decision.

Reparations

The last Japanese internment camp closed in March 1946. President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 in 1976, and in 1988, Congress issued a formal apology and passed the Civil Liberties Act awarding $20,000 each to over 80,000 Japanese Americans as reparations for their treatment.

Japanese Relocation During World War II . National Archives . Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord and R. Lord . Lordsburg Internment POW Camp. Historical Society of New Mexico . Smithsonian Institute .

Watch the documentary event, FDR . Available to stream now.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII. (2019, Aug 19). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay

"Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII." StudyMoose , 19 Aug 2019, https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay

StudyMoose. (2019). Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay [Accessed: 22 Jun. 2024]

"Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII." StudyMoose, Aug 19, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2024. https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay

"Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII," StudyMoose , 19-Aug-2019. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay. [Accessed: 22-Jun-2024]

StudyMoose. (2019). Impact of Japanese American Internment During WWII . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/japanese-internment-camps-essay [Accessed: 22-Jun-2024]

- The Japanese Internment: A Dark Chapter in American History. Pages: 5 (1325 words)

- Holocaust vs Japanese Internment Camps Pages: 3 (689 words)

- Japanese Internment Camps And The Crucible Pages: 4 (943 words)

- Life in Japanese Internment Camps Pages: 6 (1742 words)

- Interview with someone who lived during WWII Pages: 6 (1736 words)

- U.S. Women’s Efforts During WWII Pages: 7 (2085 words)

- Japanese Culture and Its Influence on The Japanese Film Industry as Well as Its Western Counterpart Pages: 2 (469 words)

- Japanese Manga vs Japanese Anime: Genre Comparison Pages: 5 (1265 words)

- The Account Of Living In Internment Camp In Farewell To Manzar Pages: 6 (1646 words)

- Are Zoos Internment Camps for Animals Pages: 3 (810 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- Collections

- Services & Support

- San Diego State University

- Research by Subject

Japanese American Incarceration Camp Research Guide

- How did this happen?

- How did children cope with the camps?

- How did Japanese Americans respond to incarceration?

- What was daily life like in the incarceration camps?

- What were some of the other perspectives involved?

- What are the ten camps?

- What are some cultural heritage and political advocacy organizations?

- What are some additional resources?

- Acknowledgements

Assistant Head of Collections

Library Hours

E-resource problem report.

- e-Resource Problem Report Please use this form to report issues you encounter while accessing any e-resources. more... less... E-resources include databases, websites, e-journals, and e-books that are accessed through OneSearch, the A-Z Databases List, Research Guides, etc.

Purpose of the Guide and How to Use it

(Jack and Peggy Iwata Collection / Japanese American National Museum)

The guide seeks to answer key questions about this event, which can be found on the left side of the page. Each page offers three important primary sources, secondary sources, and media resources on the particular subject. The Additional Resources page provides a wealth of related documents and collections. The purpose of this guide is to provide primary and secondary sources that contain information related to the Japanese American Incarceration Camps during WWII. Between 1942 and 1945, 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to ten concentration camps.

The guide coincides with the 2020 One Book, One San Diego winner-"They Called Us Enemy" written by George Takei and illustrated by Harmony Becker. It is meant to be used as a starting point for the student interested in this aspect of history who may not know much about it. The materials in the Additional Resources section range from photography collections taken by camp prisoners to U.S. government documents. The guide provides both etic and emic materials to better encapsulate the topic.

One Book, One San Diego 2020: "They Called Us Enemy" by George Takei and Illustrated by Harmony Becker

- "They Called Us Enemy" by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott and Illustrated by Harmony Becker In this graphic novel, George Takei revisits his haunting childhood in American concentration camps, as one of 120,000 Japanese Americans imprisoned by the U.S. government during World War II. One Book One San Diego Winner 2020. NOTE: NOT LOANABLE at SDSU. Also on CSU+.

- One Book, One San Diego San Diego's premier literary program, presented in partnership between KPBS and over 80 public libraries, service organizations and educational institutions. Now in its 14th year, the purpose is to bring the community closer together through the shared experience of reading and discussing the same book. This research guide was created to support the 2020 OBOSD winner.

Correct Language

The correct terminology is "incarceration camp" and not "internment camp" or "relocation center." Unfortunately, cataloging has not caught up with modern terminology, so most search results in Library of Congress, Scopus, and other databases will yield most of the results to keywords of "internment" or "relocation."

- Densho: Correct Terminology Updated terminology of Japanese-American Concentration camps. Forced Removal vs "Evacuation." Incarceration vs "Internment." Japanese American vs "Japanese." Concentration Camps vs "Relocation Centers."

- Next: How did this happen? >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 11:06 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sdsu.edu/JapaneseAmericanIncarceration

Virtual Tour

Experience University of Idaho with a virtual tour. Explore now

- Discover a Career

- Find a Major

- Experience U of I Life

More Resources

- Admitted Students

- International Students

Take Action

- Find Financial Aid

- View Deadlines

- Find Your Rep

Helping to ensure U of I is a safe and engaging place for students to learn and be successful. Read about Title IX.

Get Involved

- Clubs & Volunteer Opportunities

- Recreation and Wellbeing

- Student Government

- Student Sustainability Cooperative

- Academic Assistance

- Safety & Security

- Career Services

- Health & Wellness Services

- Register for Classes

- Dates & Deadlines

- Financial Aid

- Sustainable Solutions

- U of I Library

- Upcoming Events

Review the events calendar.

Stay Connected

- Vandal Family Newsletter

- Here We Have Idaho Magazine

- Living on Campus

- Campus Safety

- About Moscow

The largest Vandal Family reunion of the year. Check dates.

Benefits and Services

- Vandal Voyagers Program

- Vandal License Plate

- Submit Class Notes

- Make a Gift

- View Events

- Alumni Chapters

- University Magazine

- Alumni Newsletter

U of I's web-based retention and advising tool provides an efficient way to guide and support students on their road to graduation. Login to VandalStar.

Common Tools

- Administrative Procedures Manual (APM)

- Class Schedule

- OIT Tech Support

- Academic Dates & Deadlines

- U of I Retirees Association

- Faculty Senate

- Staff Council

Asian American Comparative Collection

Physical Address: 404 Sweet Avenue

Mailing Address: Asian American Comparative Collection University of Idaho 875 Perimeter Drive MS 1111 Moscow, Idaho 83844-1111

Phone: 208-885-7075

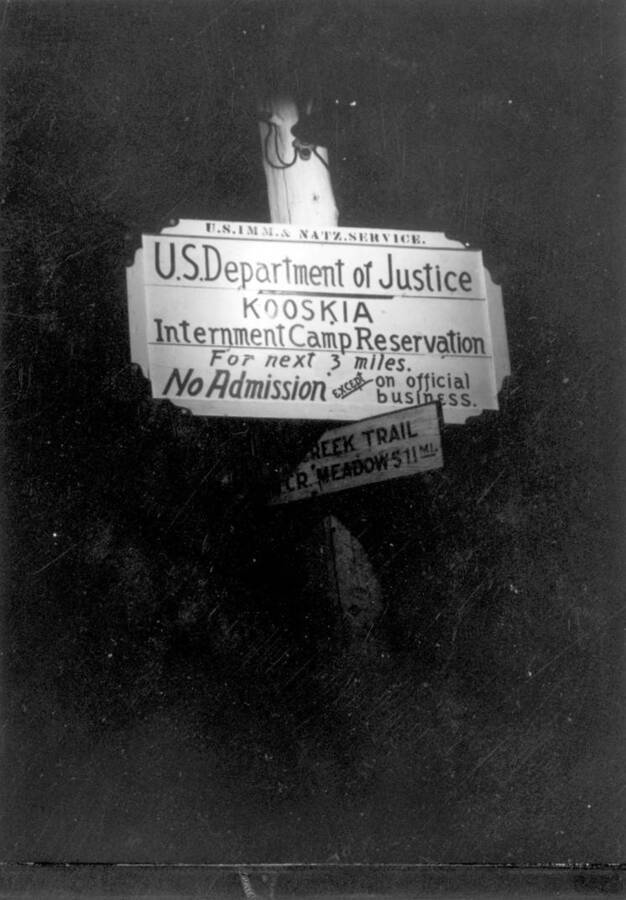

Kooskia, Idaho, World War II Japanese Internment Camp

The Kooskia (pronounced KOOS-key) Internment Camp is an obscure and virtually forgotten World War II detention facility that was located in a remote area of north central Idaho, 30 miles from the town of Kooskia, and 6 miles east of the hamlet of Lowell, at Canyon Creek. The Kooskia Internment Camp was administered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) for the U.S. Department of Justice. It held men of Japanese ancestry who were termed "enemy aliens," even though most of them were long-time U.S. residents, denied naturalization by racist U.S. laws.

Immediately following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, numerous Japanese, German and Italian aliens were arrested and detained on no specific grounds, without the due process guaranteed to them by the U.S. Constitution, and were sent to INS detention camps at Fort Missoula, Montana; Bismarck, North Dakota; and elsewhere. The INS camps were separate and distinct from the ten major camps under War Relocation Authority (WRA) supervision. The WRA camps, including Minidoka (now the Minidoka National Historic Site) near Jerome, in southern Idaho, housed some 120,000 American citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who were unconstitutionally removed, relocated and imprisoned by the U.S. government during World War II.

- Obtain DOJ closed legal case files (CLCF) from NARA

- Kooskia Internment Camp archaeological project

- Buy related books

- California towns of origin or residence for Kooskia internees

- Justice Department and U.S. Army Internment Camps and Detention Stations in the U.S. during World War II.

- Food and clothing at the Kooskia Internment Camp

- Bids for services at the Kooskia Internment Camp

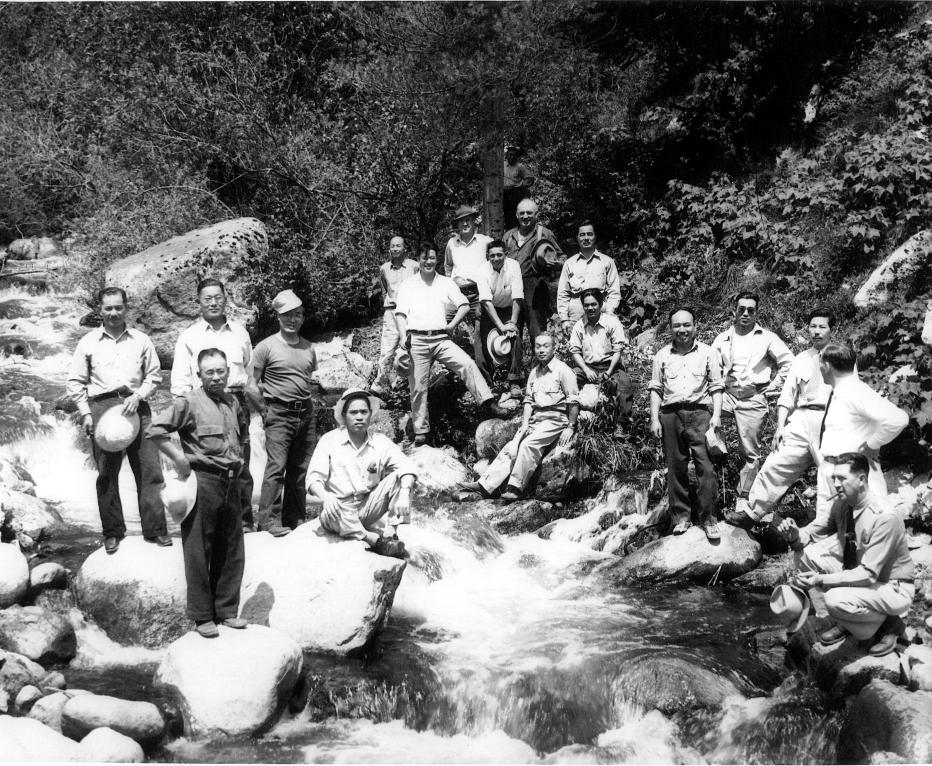

Although there were a number of Justice Department internment camps throughout the United States during WWII, the Kooskia Internment Camp was unique because it was the only camp of its kind in the United States. Its inmates had volunteered to go there from other camps, and received wages for their work. A total of some 265 male Japanese citizens; 24 male and 3 female Euroamerican civilian employees; 2 male internee doctors, one Italian and one German; and 1 male Japanese American interpreter occupied the Kooskia Internment Camp at various times between May 1943 and May 1945. Although some of the internees held camp jobs, most of the men were construction workers for a portion of the present Highway 12 between Lewiston, Idaho, and Missoula, Montana, parallel to the wild and scenic Lochsa River.

The Japanese internees at the Kooskia camp came from Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Hawai'i, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah and Washington. They included Reverend Hozen Seki, founder of the New York Buddhist Church; Toraichi Kono, former employee of Charlie Chaplin; and Japanese Latin Americans kidnapped from their respective countries, chiefly Peru, by U.S. government agencies. "Digging in the documents" has produced INS, Forest Service, Border Patrol, and University of Idaho photographs and other records. These, combined with internee and employee oral and written interviews, illuminate the internees' experiences, emphasizing the perspectives of the men detained at the Kooskia Internment Camp.

The Kooskia Internment Camp project was partially funded by an Idaho Humanities Council Research Fellowship and by a grant from the federal Civil Liberties Public Education Fund ( CLPEF ). The CLPEF was authorized by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which awarded apologies and redress payments to citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry unconstitutionally evacuated, relocated and interned during World War II. The Act also provided for the establishment of the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, financing endeavors that inform the public about the internment in order to prevent the recurrence of any similar event. Wegars' report to the CLPEF is entitled, "A Real He-Man's Job:" Japanese Internees and the Kooskia Internment Camp, Idaho, 1943-1945," emphasizing the perspective of the Kooskia internees. Although no more copies of that report are available, it has been excerpted for several publications, you may purchase the book Imprisoned in Paradise: Japanese Internee Road Workers at the World War II Kooskia Internment Camp , and a PowerPoint lecture has been presented to numerous public groups. Wegars also received a grant from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program (CCLPEP), a product of the California State Library. That project was Golden State Meets Gem State: Californians at Idaho's Kooskia Internment Camp, 1943-1945 ; some 82 of the Kooskia internees (31 percent) had ties to California. In connection with that grant, slide presentations were given during early 2002 at a number of locations in California.

For further reading, Wegars' essay, "Japanese and Japanese Latin Americans at Idaho's Kooskia Internment Camp," appears in Guilt by Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment, and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West , Mike Mackey, editor, pp. 145-183 (Powell, WY: Western History Publications, 2001). See a brief trailer for the documentary film Toraichi Kono : Living in Silence , about Kooskia internee Toraichi Kono, a former employee of former movie comedian Charlie Chaplin. The Densho Encyclopedia contains an entry on Kooskia , as well as entries on other World War II detention facilities and incarceration camps.

Additional Information

Priscilla Wegars is interested in communicating with former Kooskia Internment Camp internees and employees, or their descendants, in order to interview them. She is also eager to locate additional letters, diaries, photographs or other documents relating to the Kooskia Internment Camp experience. She would also enjoy hearing from any man, or descendants of any man, who was at CCC Camp F-38 or who was incarcerated or worked at Federal Prison Camp No. 11 at Canyon Creek.

Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook

Documenting the daily life of Japanese Americans incarcerated by the US Government near Kooskia, ID during World War II

The below is adapted (with permission) from the Asian American Comparative Collection’s website , written by Dr. Priscilla Wegars. Dr. Wegars has also written a book on the Kooskia Internment Camp; the book’s catalog record is linked here and below.

Contents: About the Camp | About the Scrapbook | For More Information | Tech

ABOUT THE CAMP

The Kooskia (pronounced KOOS-key) Internment Camp is an obscure and virtually forgotten World War II detention facility that was located in a remote area of north central Idaho, 30 miles from the town of Kooskia, and 6 miles east of the hamlet of Lowell, at Canyon Creek. The camp was administered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) for the U.S. Department of Justice. It held men of Japanese ancestry who were termed “enemy aliens,” even though most of them were long-time U.S. residents.

Although there were a number of Justice Department internment camps throughout the United States during WWII, the Kooskia Internment Camp was unique in that its inmates volunteered to transfer there from other camps and received wages for their work. A total of some 265 male Japanese aliens occupied the Kooskia Internment Camp at various times between May 1943 and May 1945. Although some internees held camp jobs, most worked construction on a portion of the Lewis and Clark Highway (now US 12) between Lewiston, Idaho, and Missoula, Montana, that ran parallel to the wild and scenic Lochsa River.

The Japanese internees at the Kooskia camp came from 23 states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Hawai’i, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, and Washington). They included Reverend Hozen Seki , founder of the New York Buddhist Church; Toraichi Kono , former employee of Charlie Chaplin; and Japanese Latin Americans kidnapped from their respective countries, chiefly Peru, by U.S. government agencies.

Dr. Wegars’ research has uncovered INS, Forest Service, Border Patrol, and University of Idaho photographs and other records. These, combined with internee and employee oral and written interviews, illuminate the internees’ experiences, emphasizing the perspectives of the men detained at the Kooskia Internment Camp. For more information see her website .

ABOUT THE SCRAPBOOK

The Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook is a hand-made manuscript consisting of 148 photographs (and two drawings) of activities and and buildings related the Kooskia Internment Camp.

In 2005, the son of one of the camp’s now-deceased guards discovered the scrapbook among family memorabilia and offered it to the University of Idaho. Consequently, the scrapbook was purchased by the University of Idaho Library with financial assistance from the Library Associates, a friends group.

The scrapbook is located at the University of Idaho Special Collections & Archives and cataloged as Photograph Group 103.

For More Information

Wegars, Priscilla. Imprisoned in Paradise: Japanese Internee Road Workers at the World War Ii Kooskia Internment Camp . Moscow, Idaho: Asian American Comparative Collection, University of Idaho, 2010.

Wegars, Priscilla. “Japanese and Japanese Latin Americans at Idaho’s Kooskia Internment Camp,” Guilt by Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment, and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West , Ed. Mike Mackey. Powell, WY: Western History Publications, 2001, pp. 145-183.

The University of Idaho Library also holds an internment camp diary written in Japanese. More information regarding the diary can be found here .

The Shitamae Family Letters Collection which contains letters from the Mindioka Incarceration Camp can be found here .

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder , an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

Using the CollectionBuilder-CSV template and the static website generator Jekyll , this project creates an engaging interface to explore driven by metadata.

More Information Available

COMMENTS

Collection Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers, 1942 to 1946 Menu . ... Articles and Essays; All Digitized Titles; Listen to this page. Timeline. Timeline December 7, 1941. Japan attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, leading the U.S. to enter World War II. February 19, 1942.

Japanese Americans were finally free to return to their homes on December 17, 1944. Their homes were marked by the vigilante violence and agitation of pressure group. Most of the internment camps did not close until October 1946. The U.S. government enacted the Civil Liberties Act.

Japanese Internment Camps Are a Dark Period. PAGES 2 WORDS 553. Japanese internment camps are a dark period of American history. The forced incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent was based solely on racism and a culture of fear. During World War II, Americans also counted Italians and Japanese as their archrivals but of these groups, it ...

Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice. One of the most lamentable episodes in American history is the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, revealing the dark underbelly of prejudice and fear during times of crisis. This essay delves into the historical context that led to this tragic event, the harrowing ...

Japanese Internment Camps Essay. Japanese Internment Camps Discrimination and entrapment of a race due to a possible conspiracy; it's not Hitler, but our own government. On the 7th of December, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, provoking fear throughout America. This fear, plus an already existing hatred toward the race, lead many to ...

Essay On Japanese Internment Camps. 560 Words3 Pages. After the end of World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt revoked Executive Order 9066 ("Japanese-American Internment."). Internees were given a short amount of time to leave the internment camps and find new places to settle. This was found difficult by many Japanese Americans, shortly ...

Defiant Loyalty: Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers In the pages of newspapers published behind the barbed wire of Japanese-American internment camps, one theme stands out: loyalty to the country that placed its own citizens there.

Paul Kitagaki Jr. is a senior photographer at The Sacramento Bee. His work has won numerous awards, including a shared Pulitzer Prize in 1990. Filed Under: Japan, Photography, Photojournalism ...

In an effort to curb potential Japanese espionage, Executive Order 9066 approved the relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps. At first, the relocations were completed on a voluntary basis. Volunteers to relocate were minimal, so the executive order paved the way for forced relocation of Japanese-Americans living on the west coast.

Between 1942 and 1945 a total of 10 camps were opened, holding approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans for varying periods of time in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas. Japanese American internment, the forced relocation by the U.S. government of thousands of Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II.

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066. From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that ...

On February 19, 1942, during World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, leading to the relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps. General DeWitt recommended this action as a response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, with farmers and politicians influencing the decision.

View our collection of japanese internment camps essays. Find inspiration for topics, titles, outlines, & craft impactful japanese internment camps papers. Read our japanese internment camps papers today! ... Essay Title Generator Citation Generator Flashcard Generator Essay Outline Generator Homework Help At paperdue.com, we provide students ...

Internment Camps Essay Internment Camps The move to the internment camps was a difficult journey for many Japanese- Americans. Many of them were taken from their homes and were allowed only to bring a few belongings. Okubo colorfully illustrates the dramatic adjustment of lifestyle that Japanese- Americans had to make during the war.

Japanese Internment Camps Essay 1529 Words | 7 Pages. Japanese Americans could not hold onto personal heirlooms, prized possessions, and homes as the Constitution promised. In addition, the Japanese American lifestyle was interrupted. Due to restrained life, family strains grew, the "traditional powers enjoyed by elder males were challenged ...

The purpose of this guide is to provide primary and secondary sources that contain information related to the Japanese American Incarceration Camps during WWII. Between 1942 and 1945, 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to ten concentration camps. ... The correct terminology is "incarceration camp" and not "internment camp" or "relocation ...

This regiment was known for saving the 141st battalion from the Germans during the war. In 1945, the interment of the Japanese officially ended. They began to leave the camps. However, many Japanese did not leave the camps, because they did not have any other place to go after the interment. Many had lost all of their money, valuables, and houses.

For further reading, Wegars' essay, "Japanese and Japanese Latin Americans at Idaho's Kooskia Internment Camp," appears in Guilt by Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment, and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West, Mike Mackey, editor, pp. 145-183 (Powell, WY: Western History Publications, 2001).

Decent Essays. 1382 Words. 6 Pages. Open Document. Very similar to the concentration camps happening in the same time period, Japanese internment camps began during WWII after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The U.S. government put a lot of Japanese-American citizens in the camps due to the fact that they didn't want them to turn out to be spies ...

prepared by Machiko Inagawa entitled Japanese American Experiences in Internment Camps during World War II as Represented by Children's and Adolescent Literature and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Between 1942 and 1945, U.S. government policy forced people of Japanese ancestry into isolated internment camps. The policy came as a reaction to the attack on Pearl Harbor and the ensuing war ...

Washington, D.C. 20500. Dear Mr. President: I am honored to provide the Department of the Interior's report and recommendations to preserve the World War II Japanese-American Interment sites, as directed by your November 9, 2000, memorandum. As you requested, we consulted with States, Tribes, local and national organizations involved in the ...

The Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook is a hand-made manuscript consisting of 148 photographs (and two drawings) which document the lives of Japanese American men incarcerated during the camp's two years of operation (May 1943 - May 1945). The camp was located in a remote area of north central Idaho, 30 miles from the town of Kooskia and administered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization ...