How to write and structure a journal article

Sharing your research data can be hugely beneficial to your career , as well as to the scholarly community and wider society. But before you do so, there are some important ethical considerations to remember.

What are the rules and guidance you should follow, when you begin to think about how to write and structure a journal article? Ruth First Prize winner Steven Rogers, PhD said the first thing is to be passionate about what you write.

Steven Nabieu Rogers, Ruth First Prize winner.

Let’s go through some of the best advice that will help you pinpoint the features of a journal article, and how to structure it into a compelling research paper.

Planning for your article

When planning to write your article, make sure it has a central message that you want to get across. This could be a novel aspect of methodology that you have in your PhD study, a new theory, or an interesting modification you have made to theory or a novel set of findings.

2018 NARST Award winner Marissa Rollnick advised that you should decide what this central focus is, then create a paper outline bearing in mind the need to:

Isolate a manageable size

Create a coherent story/argument

Make the argument self-standing

Target the journal readership

Change the writing conventions from that used in your thesis

Get familiar with the journal you want to submit to

It is a good idea to choose your target journal before you start to write your paper. Then you can tailor your writing to the journal’s requirements and readership, to increase your chances of acceptance.

When selecting your journal think about audience, purposes, what to write about and why. Decide the kind of article to write. Is it a report, position paper, critique or review? What makes your argument or research interesting? How might the paper add value to the field?

If you need more guidance on how to choose a journal, here is our guide to narrow your focus.

Once you’ve chosen your target journal, take the time to read a selection of articles already published – particularly focus on those that are relevant to your own research.

This can help you get an understanding of what the editors may be looking for, then you can guide your writing efforts.

The Think. Check. Submit. initiative provides tools to help you evaluate whether the journal you’re planning to send your work to is trustworthy.

The journal’s aims and scope is also an important resource to refer back to as you write your paper – use it to make sure your article aligns with what the journal is trying to accomplish.

Keep your message focused

The next thing you need to consider when writing your article is your target audience. Are you writing for a more general audience or is your audience experts in the same field as you? The journal you have chosen will give you more information on the type of audience that will read your work.

When you know your audience, focus on your main message to keep the attention of your readers. A lack of focus is a common problem and can get in the way of effective communication.

Stick to the point. The strongest journal articles usually have one point to make. They make that point powerfully, back it up with evidence, and position it within the field.

How to format and structure a journal article

The format and structure of a journal article is just as important as the content itself, it helps to clearly guide the reader through.

How do I format a journal article?

Individual journals will have their own specific formatting requirements, which you can find in the instructions for authors.

You can save time on formatting by downloading a template from our library of templates to apply to your article text. These templates are accepted by many of our journals. Also, a large number of our journals now offer format-free submission, which allows you to submit your paper without formatting your manuscript to meet that journal’s specific requirements.

General structure for writing an academic journal article

The title of your article is one of the first indicators readers will get of your research and concepts. It should be concise, accurate, and informative. You should include your most relevant keywords in your title, but avoid including abbreviations and formulae.

Keywords are an essential part of producing a journal article. When writing a journal article you must select keywords that you would like your article to rank for.

Keywords help potential readers to discover your article when conducting research using search engines.

The purpose of your abstract is to express the key points of your research, clearly and concisely. An abstract must always be well considered, as it is the primary element of your work that readers will come across.

An abstract should be a short paragraph (around 300 words) that summarizes the findings of your journal article. Ordinarily an abstract will be comprised of:

What your research is about

What methods have been used

What your main findings are

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements can appear to be a small aspect of your journal article, however it is still important. This is where you acknowledge the individuals who do not qualify for co-authorship, but contributed to your article intellectually, financially, or in some other manner.

When you acknowledge someone in your academic texts, it gives you more integrity as a writer as it shows that you are not claiming other academic’s ideas as your own intellectual property. It can also aid your readers in their own research journeys.

Introduction

An introduction is a pivotal part of the article writing process. An introduction not only introduces your topic and your stance on the topic, but it also (situates/contextualizes) your argument in the broader academic field.

The main body is where your main arguments and your evidence are located. Each paragraph will encapsulate a different notion and there will be clear linking between each paragraph.

Your conclusion should be an interpretation of your results, where you summarize all of the concepts that you introduced in the main body of the text in order of most to least important. No new concepts are to be introduced in this section.

References and citations

References and citations should be well balanced, current and relevant. Although every field is different, you should aim to cite references that are not more than 10 years old if possible. The studies you cite should be strongly related to your research question.

Clarity is key

Make your writing accessible by using clear language. Writing that is easy to read, is easier to understand too.

You may want to write for a global audience – to have your research reach the widest readership. Make sure you write in a way that will be understood by any reader regardless of their field or whether English is their first language.

Write your journal article with confidence, to give your reader certainty in your research. Make sure that you’ve described your methodology and approach; whilst it may seem obvious to you, it may not to your reader. And don’t forget to explain acronyms when they first appear.

Engage your audience. Go back to thinking about your audience; are they experts in your field who will easily follow technical language, or are they a lay audience who need the ideas presented in a simpler way?

Be aware of other literature in your field, and reference it

Make sure to tell your reader how your article relates to key work that’s already published. This doesn’t mean you have to review every piece of previous relevant literature, but show how you are building on previous work to avoid accidental plagiarism.

When you reference something, fully understand its relevance to your research so you can make it clear for your reader. Keep in mind that recent references highlight awareness of all the current developments in the literature that you are building on. This doesn’t mean you can’t include older references, just make sure it is clear why you’ve chosen to.

How old can my references be?

Your literature review should take into consideration the current state of the literature.

There is no specific timeline to consider. But note that your subject area may be a factor. Your colleagues may also be able to guide your decision.

Researcher’s view

Grasian Mkodzongi, Ruth First Prize Winner

Top tips to get you started

Communicate your unique point of view to stand out. You may be building on a concept already in existence, but you still need to have something new to say. Make sure you say it convincingly, and fully understand and reference what has gone before.

Editor’s view

Professor Len Barton, Founding Editor of Disability and Society

Be original

Now you know the features of a journal article and how to construct it. This video is an extra resource to use with this guide to help you know what to think about before you write your journal article.

Expert help for your manuscript

Taylor & Francis Editing Services offers a full range of pre-submission manuscript preparation services to help you improve the quality of your manuscript and submit with confidence.

Related resources

How to write your title and abstract

Journal manuscript layout guide

Improve the quality of English of your article

How to edit your paper

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

276k Accesses

15 Citations

717 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

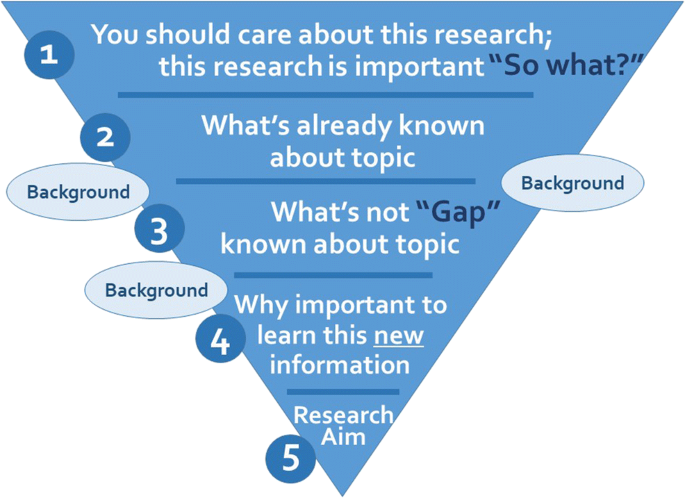

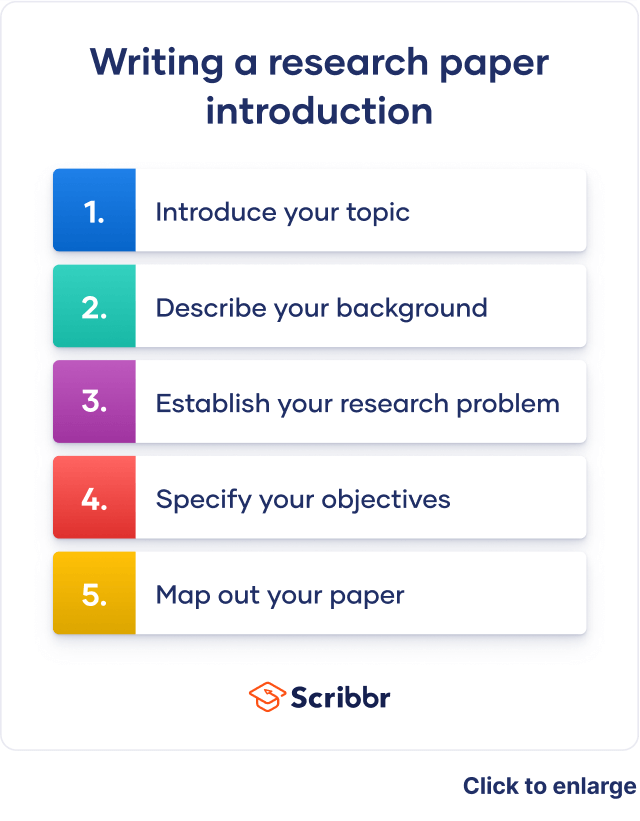

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

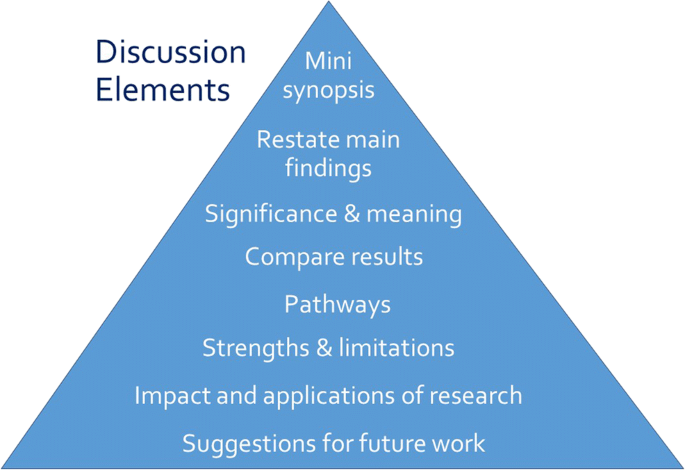

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

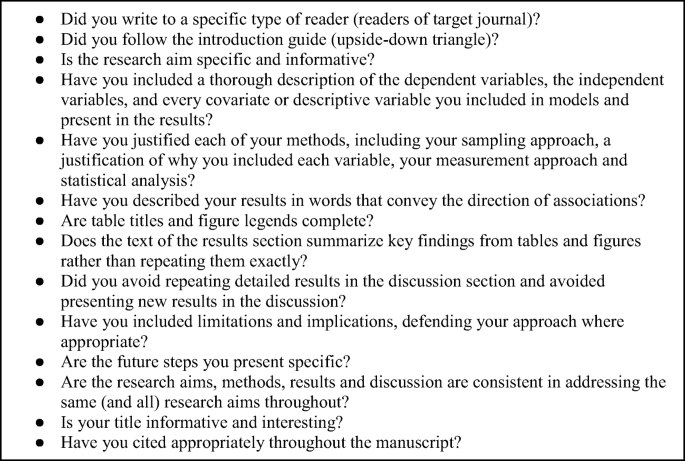

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Welcome to the PLOS Writing Center

Your source for scientific writing & publishing essentials.

A collection of free, practical guides and hands-on resources for authors looking to improve their scientific publishing skillset.

ARTICLE-WRITING ESSENTIALS

Your title is the first thing anyone who reads your article is going to see, and for many it will be where they stop reading. Learn how to write a title that helps readers find your article, draws your audience in and sets the stage for your research!

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability. Learn what to include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate.

In many fields, a statistical analysis forms the heart of both the methods and results sections of a manuscript. Learn how to report statistical analyses, and what other context is important for publication success and future reproducibility.

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

Ensuring your manuscript is well-written makes it easier for editors, reviewers and readers to understand your work. Avoiding language errors can help accelerate review and minimize delays in the publication of your research.

The PLOS Writing Toolbox

Delivered to your inbox every two weeks, the Writing Toolbox features practical advice and tools you can use to prepare a research manuscript for submission success and build your scientific writing skillset.

Discover how to navigate the peer review and publishing process, beyond writing your article.

The path to publication can be unsettling when you’re unsure what’s happening with your paper. Learn about staple journal workflows to see the detailed steps required for ensuring a rigorous and ethical publication.

Reputable journals screen for ethics at submission—and inability to pass ethics checks is one of the most common reasons for rejection. Unfortunately, once a study has begun, it’s often too late to secure the requisite ethical reviews and clearances. Learn how to prepare for publication success by ensuring your study meets all ethical requirements before work begins.

From preregistration, to preprints, to publication—learn how and when to share your study.

How you store your data matters. Even after you publish your article, your data needs to be accessible and useable for the long term so that other researchers can continue building on your work. Good data management practices make your data discoverable and easy to use, promote a strong foundation for reproducibility and increase your likelihood of citations.

You’ve just spent months completing your study, writing up the results and submitting to your top-choice journal. Now the feedback is in and it’s time to revise. Set out a clear plan for your response to keep yourself on-track and ensure edits don’t fall through the cracks.

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher.

Are you actively preparing a submission for a PLOS journal? Select the relevant journal below for more detailed guidelines.

How to Write an Article

Share the lessons of the Writing Center in a live, interactive training.

Access tried-and-tested training modules, complete with slides and talking points, workshop activities, and more.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, March 27). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved June 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Research Guides

Reading for Research: Social Sciences

Structure of a research article.

- Structural Read

Guide Acknowledgements

How to Read a Scholarly Article from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Strategic Reading for Research from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Bridging the Gap between Faculty Expectation and the Student Experience: Teaching Students toAnnotate and Synthesize Sources

Librarian for Sociology, Environmental Sociology, MHS and Public Policy Studies

Academic writing has features that vary only slightly across the different disciplines. Knowing these elements and the purpose of each serves help you to read and understand academic texts efficiently and effectively, and then apply what you read to your paper or project.

Social Science (and Science) original research articles generally follow IMRD: Introduction- Methods-Results-Discussion

Introduction

- Introduces topic of article

- Presents the "Research Gap"/Statement of Problem article will address

- How research presented in the article will solve the problem presented in research gap.

- Literature Review. presenting and evaluating previous scholarship on a topic. Sometimes, this is separate section of the article.

Method & Results

- How research was done, including analysis and measurements.

- Sometimes labeled as "Research Design"

- What answers were found

- Interpretation of Results (What Does It Mean? Why is it important?)

- Implications for the Field, how the study contributes to the existing field of knowledge

- Suggestions for further research

- Sometimes called Conclusion

You might also see IBC: Introduction - Body - Conclusion

- Identify the subject

- State the thesis

- Describe why thesis is important to the field (this may be in the form of a literature review or general prose)

Body

- Presents Evidence/Counter Evidence

- Integrate other writings (i.e. evidence) to support argument

- Discuss why others may disagree (counter-evidence) and why argument is still valid

- Summary of argument

- Evaluation of argument by pointing out its implications and/or limitations

- Anticipate and address possible counter-claims

- Suggest future directions of research

- Next: Structural Read >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/readingforresearch

WRITING A SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLE | Format for the paper | Edit your paper! | Useful books | FORMAT FOR THE PAPER Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. A standard format is used for these articles, in which the author presents the research in an orderly, logical manner. This doesn't necessarily reflect the order in which you did or thought about the work. This format is: | Title | Authors | Introduction | Materials and Methods | Results (with Tables and Figures ) | Discussion | Acknowledgments | Literature Cited | TITLE Make your title specific enough to describe the contents of the paper, but not so technical that only specialists will understand. The title should be appropriate for the intended audience. The title usually describes the subject matter of the article: Effect of Smoking on Academic Performance" Sometimes a title that summarizes the results is more effective: Students Who Smoke Get Lower Grades" AUTHORS 1. The person who did the work and wrote the paper is generally listed as the first author of a research paper. 2. For published articles, other people who made substantial contributions to the work are also listed as authors. Ask your mentor's permission before including his/her name as co-author. ABSTRACT 1. An abstract, or summary, is published together with a research article, giving the reader a "preview" of what's to come. Such abstracts may also be published separately in bibliographical sources, such as Biologic al Abstracts. They allow other scientists to quickly scan the large scientific literature, and decide which articles they want to read in depth. The abstract should be a little less technical than the article itself; you don't want to dissuade your potent ial audience from reading your paper. 2. Your abstract should be one paragraph, of 100-250 words, which summarizes the purpose, methods, results and conclusions of the paper. 3. It is not easy to include all this information in just a few words. Start by writing a summary that includes whatever you think is important, and then gradually prune it down to size by removing unnecessary words, while still retaini ng the necessary concepts. 3. Don't use abbreviations or citations in the abstract. It should be able to stand alone without any footnotes. INTRODUCTION What question did you ask in your experiment? Why is it interesting? The introduction summarizes the relevant literature so that the reader will understand why you were interested in the question you asked. One to fo ur paragraphs should be enough. End with a sentence explaining the specific question you asked in this experiment. MATERIALS AND METHODS 1. How did you answer this question? There should be enough information here to allow another scientist to repeat your experiment. Look at other papers that have been published in your field to get some idea of what is included in this section. 2. If you had a complicated protocol, it may helpful to include a diagram, table or flowchart to explain the methods you used. 3. Do not put results in this section. You may, however, include preliminary results that were used to design the main experiment that you are reporting on. ("In a preliminary study, I observed the owls for one week, and found that 73 % of their locomotor activity occurred during the night, and so I conducted all subsequent experiments between 11 pm and 6 am.") 4. Mention relevant ethical considerations. If you used human subjects, did they consent to participate. If you used animals, what measures did you take to minimize pain? RESULTS 1. This is where you present the results you've gotten. Use graphs and tables if appropriate, but also summarize your main findings in the text. Do NOT discuss the results or speculate as to why something happened; t hat goes in th e Discussion. 2. You don't necessarily have to include all the data you've gotten during the semester. This isn't a diary. 3. Use appropriate methods of showing data. Don't try to manipulate the data to make it look like you did more than you actually did. "The drug cured 1/3 of the infected mice, another 1/3 were not affected, and the third mouse got away." TABLES AND GRAPHS 1. If you present your data in a table or graph, include a title describing what's in the table ("Enzyme activity at various temperatures", not "My results".) For graphs, you should also label the x and y axes. 2. Don't use a table or graph just to be "fancy". If you can summarize the information in one sentence, then a table or graph is not necessary. DISCUSSION 1. Highlight the most significant results, but don't just repeat what you've written in the Results section. How do these results relate to the original question? Do the data support your hypothesis? Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported? If your results were unexpected, try to explain why. Is there another way to interpret your results? What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results? How do y our results fit into the big picture? 2. End with a one-sentence summary of your conclusion, emphasizing why it is relevant. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This section is optional. You can thank those who either helped with the experiments, or made other important contributions, such as discussing the protocol, commenting on the manuscript, or buying you pizza. REFERENCES (LITERATURE CITED) There are several possible ways to organize this section. Here is one commonly used way: 1. In the text, cite the literature in the appropriate places: Scarlet (1990) thought that the gene was present only in yeast, but it has since been identified in the platypus (Indigo and Mauve, 1994) and wombat (Magenta, et al., 1995). 2. In the References section list citations in alphabetical order. Indigo, A. C., and Mauve, B. E. 1994. Queer place for qwerty: gene isolation from the platypus. Science 275, 1213-1214. Magenta, S. T., Sepia, X., and Turquoise, U. 1995. Wombat genetics. In: Widiculous Wombats, Violet, Q., ed. New York: Columbia University Press. p 123-145. Scarlet, S.L. 1990. Isolation of qwerty gene from S. cerevisae. Journal of Unusual Results 36, 26-31. EDIT YOUR PAPER!!! "In my writing, I average about ten pages a day. Unfortunately, they're all the same page." Michael Alley, The Craft of Scientific Writing A major part of any writing assignment consists of re-writing. Write accurately Scientific writing must be accurate. Although writing instructors may tell you not to use the same word twice in a sentence, it's okay for scientific writing, which must be accurate. (A student who tried not to repeat the word "hamster" produced this confusing sentence: "When I put the hamster in a cage with the other animals, the little mammals began to play.") Make sure you say what you mean. Instead of: The rats were injected with the drug. (sounds like a syringe was filled with drug and ground-up rats and both were injected together) Write: I injected the drug into the rat.

- Be careful with commonly confused words:

Temperature has an effect on the reaction. Temperature affects the reaction.

I used solutions in various concentrations. (The solutions were 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 15 mg/ml) I used solutions in varying concentrations. (The concentrations I used changed; sometimes they were 5 mg/ml, other times they were 15 mg/ml.)

Less food (can't count numbers of food) Fewer animals (can count numbers of animals)

A large amount of food (can't count them) A large number of animals (can count them)

The erythrocytes, which are in the blood, contain hemoglobin. The erythrocytes that are in the blood contain hemoglobin. (Wrong. This sentence implies that there are erythrocytes elsewhere that don't contain hemoglobin.)

Write clearly

1. Write at a level that's appropriate for your audience.

"Like a pigeon, something to admire as long as it isn't over your head." Anonymous

2. Use the active voice. It's clearer and more concise than the passive voice.

Instead of: An increased appetite was manifested by the rats and an increase in body weight was measured. Write: The rats ate more and gained weight.

3. Use the first person.

Instead of: It is thought Write: I think

Instead of: The samples were analyzed Write: I analyzed the samples

4. Avoid dangling participles.

"After incubating at 30 degrees C, we examined the petri plates." (You must've been pretty warm in there.)

Write succinctly

1. Use verbs instead of abstract nouns

Instead of: take into consideration Write: consider

2. Use strong verbs instead of "to be"

Instead of: The enzyme was found to be the active agent in catalyzing... Write: The enzyme catalyzed...

3. Use short words.

|

Instead of: Write: possess have sufficient enough utilize use demonstrate show assistance help terminate end

4. Use concise terms.

Instead of: Write: prior to before due to the fact that because in a considerable number of cases often the vast majority of most during the time that when in close proximity to near it has long been known that I'm too lazy to look up the reference

5. Use short sentences. A sentence made of more than 40 words should probably be rewritten as two sentences.

"The conjunction 'and' commonly serves to indicate that the writer's mind still functions even when no signs of the phenomenon are noticeable." Rudolf Virchow, 1928

Check your grammar, spelling and punctuation

1. Use a spellchecker, but be aware that they don't catch all mistakes.

"When we consider the animal as a hole,..." Student's paper

2. Your spellchecker may not recognize scientific terms. For the correct spelling, try Biotech's Life Science Dictionary or one of the technical dictionaries on the reference shelf in the Biology or Health Sciences libraries.

3. Don't, use, unnecessary, commas.

4. Proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

USEFUL BOOKS

Victoria E. McMillan, Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences , Bedford Books, Boston, 1997 The best. On sale for about $18 at Labyrinth Books, 112th Street. On reserve in Biology Library

Jan A. Pechenik, A Short Guide to Writing About Biology , Boston: Little, Brown, 1987

Harrison W. Ambrose, III & Katharine Peckham Ambrose, A Handbook of Biological Investigation , 4th edition, Hunter Textbooks Inc, Winston-Salem, 1987 Particularly useful if you need to use statistics to analyze your data. Copy on Reference shelf in Biology Library.

Robert S. Day, How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , 4th edition, Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1994. Earlier editions also good. A bit more advanced, intended for those writing papers for publication. Fun to read. Several copies available in Columbia libraries.

William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White, The Elements of Style , 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, 1987. Several copies available in Columbia libraries. Strunk's first edition is available on-line.

Facilitating the Research Writing Process with Generative Artificial Intelligence

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

In higher education, generative chatbots have infiltrated teaching and learning. Concerns about how and if to utilize chatbots in the classroom are at the forefront of scholarly discussion. This quick-hit article presents a plan to teach learners about generative AI writing tools and their ethical use for writing purposes. As generative AI tools continue to emerge, this guide can support instructors from all disciplines to engage learners in getting the most accurate information.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- Authors retain copyright and grant the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (JoSoTL) right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License, (CC-BY) 4.0 International, allowing others to share the work with proper acknowledgement and citation of the work's authorship and initial publication in the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

- Authors are able to enter separate, additional contractual agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

- In pursuit of manuscripts of the highest quality, multiple opportunities for mentoring, and greater reach and citation of JoSoTL publications, JoSoTL encourages authors to share their drafts to seek feedback from relevant communities unless the manuscript is already under review or in the publication queue after being accepted. In other words, to be eligible for publication in JoSoTL, manuscripts should not be shared publicly (e.g., online), while under review (after being initially submitted, or after being revised and resubmitted for reconsideration), or upon notice of acceptance and before publication. Once published, authors are strongly encouraged to share the published version widely, with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

Federal funding for major science agencies is at a 25-year low

University Distinguished Professor of Astronomy, University of Arizona

Disclosure statement

Chris Impey receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

University of Arizona provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Government funding for science is usually immune from political gridlock and polarization in Congress. But, federal funding for science is slated to drop for 2025.

Science research dollars are considered to be discretionary, which means the funding has to be approved by Congress every year. But it’s in a budget category with larger entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security that are generally considered untouchable by politicians of both parties.

Federal investment in scientific research encompasses everything from large telescopes supported by the National Science Foundation to NASA satellites studying climate change , programs studying the use and governance of artificial intelligence at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and research on Alzheimer’s disease funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Studies show that increasing federal research spending benefits productivity and economic competitiveness .

I’m an astronomer and also a senior university administrator. As an administrator, I’ve been involved in lobbying for research funding as associate dean of the College of Science at the University of Arizona, and in encouraging government investment in astronomy as a vice president of the American Astronomical Society. I’ve seen the importance of this kind of funding as a researcher who has had federal grants for 30 years, and as a senior academic who helps my colleagues write grants to support their valuable work.

Bipartisan support

Federal funding for many programs is characterized by political polarization , meaning that partisanship and ideological divisions between the two main political parties can lead to gridlock . Science is usually a rare exception to this problem.

The public shows strong bipartisan support for federal investment in scientific research, and Congress has generally followed suit, passing bills in 2024 with bipartisan backing in April and June .

The House passed these bills, and after reconciliation with language from the Senate, they resulted in final bills to direct US$460 billion in government spending .

However, policy documents produced by Congress reveal a partisan split in how Democratic and Republican lawmakers reference scientific research.

Congressional committees for both sides are citing more scientific papers, but there is only a 5% overlap in the papers they cite. That means that the two parties are using different evidence to make their funding decisions, rather than working from a scientific consensus. Committees under Democratic control were almost twice as likely to cite technical papers as panels led by Republicans, and they were more likely to cite papers that other scientists considered important.

Ideally, all the best ideas for scientific research would receive federal funds. But limited support for scientific research in the United States means that for individual scientists, getting funding is a highly competitive process.

At the National Science Foundation , only 1 in 4 proposals are accepted. Success rates for funding through the National Institutes of Health are even lower, with 1 in 5 proposals getting accepted. This low success rate means that the agencies have to reject many proposals that are rated excellent by the merit review process .

Scientists are often reluctant to publicly advocate for their programs, in part because they feel disconnected from the policymaking and appropriations process . Their academic training doesn’t equip them to communicate effectively to legislators and policy experts.

Budgets are down

Research received steady funding for the past few decades, but this year Congress reduced appropriations for science at many top government agencies.

The National Science Foundation budget is down 8%, which led agency leaders to warn Congress that the country may lose its ability to attract and train a scientific workforce .

The cut to the NSF is particularly disappointing since Congress promised it an extra $81 billion over five years when the CHIPS and Science Act passed in 2022. A deal to limit government spending in exchange for suspending the debt ceiling made the law’s goals hard to achieve.

NASA’s science budget is down 6%, and the budget for the National Institutes of Health, whose research aims to prevent disease and improve public health, is down 1%. Only the Department of Energy’s Office of Science got a bump, a modest 2%.

As a result, the major science agencies are nearing a 25-year low for their funding levels, as a share of U.S. gross domestic product.

Feeling the squeeze

Investment in research and development by the business sector is strongly increasing . In 1990, it was slightly higher than federal investment, but by 2020 it was nearly four times higher.

The distinction is important because business investment tends to focus on later stage and applied research, while federal funding goes to pure and exploratory research that can have enormous downstream benefits, such as for quantum computing and fusion power .

There are several causes of the science funding squeeze. Congressional intentions to increase funding levels, as with the CHIPS and Science Act, and the earlier COMPETES Act in 2007, have been derailed by fights over the debt limit and threats of government shutdowns.

The CHIPS act aimed to spur investment and job creation in semiconductor manufacturing, while the COMPETES Act aimed to increase U.S competitiveness in a wide range of high-tech industries such as space exploration.

The budget caps for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 remove any possibility for growth. The budget caps were designed to rein in federal spending, but they are a very blunt tool. Also, nondefense discretionary spending is only 15% of all federal spending. Discretionary spending is up for a vote every year, while mandatory spending is dictated by prior laws.

Entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security are mandatory forms of spending. Taken together, they are three times larger than the amount available for discretionary spending, so science has to fight over a small fraction of the overall budget pie.

Within that 15% slice , scientific research competes with K-12 education, veterans’ health care, public health, initiatives for small businesses, and more.

Global competition

While government science funding in the U.S. is stagnant, America’s main scientific rivals are rising fast.

Federal R&D funding as a percentage of GDP has dropped from 1.2% in 1987 to 1% in 2010 to under 0.8% currently. The United States is still the world’s biggest spender on research and development, but in terms of government R&D as a fraction of GDP , the United States ranked 12th in 2021, behind South Korea and a set of European countries. In terms of science researchers as a portion of the labor force , the United States ranks 10th.

Meanwhile, America’s main geopolitical rival is rising fast. China has eclipsed the United States in high-impact papers published , and China now spends more than the United States on university and government research .

If the U.S. wants to keep its status as the world leader in scientific research, it’ll need to redouble its commitment to science by appropriately funding research.

- Research funding

- Science funding

- US Congress

- Scientific research

- National Science Foundation

- National Institutes of Health

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Senior Research Fellow - Neuromuscular Disorders and Gait Analysis

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

7 in 10 Americans think Supreme Court justices put ideology over impartiality: AP-NORC poll

FILE - Members of the Supreme Court sit for a group portrait at the Supreme Court building in Washington, Oct. 7, 2022. Bottom row, from left, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Justice Samuel Alito, and Justice Elena Kagan. Top row, from left, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Neil Gorsuch, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. As the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule on a major case involving former President Donald Trump, 7 in 10 Americans think its justices are more likely to shape the law to fit their own ideology, rather than serving as neutral arbiters of government authority, according to a new poll. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

- Copy Link copied

WASHINGTON (AP) — A solid majority of Americans say Supreme Court justices are more likely to be guided by their own ideology rather than serving as neutral arbiters of government authority, a new poll finds, as the high court is poised to rule on major cases involving former President Donald Trump and other divisive issues.

The survey from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that 7 in 10 Americans think the high court’s justices are more influenced by ideology, while only about 3 in 10 U.S. adults think the justices are more likely to provide an independent check on other branches of government by being fair and impartial.

The poll reflects the continued erosion of confidence in the Supreme Court, which enjoyed broader trust as recently as a decade ago. It underscores the challenge faced by the nine justices — six appointed by Republican presidents and three by Democrats — of being seen as something other than just another element of Washington’s hyper-partisanship.

The justices are expected to decide soon whether Trump is immune from criminal charges over his efforts to overturn his 2020 reelection defeat, but the poll suggests that many Americans are already uneasy about the justices’ ability to rule impartially.

“It’s very political. There’s no question about that,” said Jeff Weddell, a 67-year-old automotive technology sales representative from Macomb County, in presidential swing-state Michigan.

“The court’s decision-making is so polluted,” said Weddell, a political independent who plans to vote for Trump in November. “No matter what they say on President Trump’s immunity, this will be politically motivated.”

Confidence in the Supreme Court remains low. The poll of 1,088 adults found that 4 in 10 U.S. adults say they have hardly any confidence in the people running the Supreme Court, in line with an AP-NORC poll from October . As recently as early 2022, before the high-profile ruling that overturned the constitutional right to abortion, an AP-NORC poll found that only around one-quarter of Americans lacked confidence in the justices.

And although the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has handed down some historic victories for Republican policy priorities over the past few years, rank-and-file Republicans aren’t giving the justices a ringing endorsement.

It’s been two years since the court’s ruling on abortion rights. Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett — Trump nominees confirmed by a Republican Senate — were part of the majority that overturned the near-50-year abortion-rights precedent established in Roe v. Wade.

This year’s term, with a dozen cases still undecided , has already seen some major rulings. Earlier in June, the Supreme Court unanimously preserved access to the pharmaceutical drug mifepristone, a medication used in nearly two-thirds of all abortions in the U.S. last year. The same week, the court struck down a Trump-era gun restriction , a ban on rapid-fire gun accessories known as bump stocks, a win for gun-rights advocates.

Only about half of Republicans have a great deal or a moderate amount of confidence in the court’s handling of important issues, including gun policy, abortion, elections and voting, and presidential power and immunity, according to the new poll.

“I don’t have a lot of faith in the Supreme Court. And that’s unfortunate because that’s the final say-so, the final check and balance on our three-branch government,” said Matt Rogers, a 37-year-old Republican from Knoxville, Tennessee.

Other Republicans share that mistrust, although the court’s current makeup is more conservative than any court in modern history. They are also split on whether the justices are more driven by personal ideology or impartiality, with about half of Republicans saying the justices are more likely to shape the law to fit their own ideology, and another half saying they are likelier to be an independent check on their co-equal branches.

“I think they are getting influenced and pressured by a lot of people and a lot of entities on the left,” said Rogers, a health and wellness trainer who plans to vote for Trump a third time this year. “Let’s be honest. It’s anything to crucify Trump.”

Some Republicans have less confidence in the court’s handling of specific issues than others. The poll found, for instance, that about 6 in 10 Republican women have little to no confidence in the court’s handling of presidential power and immunity, compared to 45% of Republican men.

Janette Majors, a Republican from Ridgefield, Washington, says it’s only natural for a justice to reflect the ideology of the president who nominated them.

But episodes outside the Supreme Court chambers have made her less confident in the people running the court.

“What you hear about Clarence Thomas, taking trips paid for by rich people, makes me think there are some individuals there that don’t sound like I should trust them,” Majors said, referring unprompted to reports that Thomas has for years received undisclosed expensive gifts, including travel, from GOP megadonor Harlan Crow.

Democrats and independents are even more skeptical of the court’s neutrality, according to the poll.

About 8 in 10 Democrats — and about 7 in 10 independents — say the justices are more likely to shape the law to fit their own ideology. A similar share has little or no confidence at all in the court’s handling of abortion, gun policy and presidential power and immunity.

Michigan Democrat Andie Near noticed that the court seemed to become a political tool in 2016, when then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to allow hearings on Democratic President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland.

McConnell quickly allowed hearings after Trump nominated Gorsuch within 10 days of taking office in 2017.

“I had thought the court, though maybe skewing left or right, was serving the whole body of the country,” the 42-year-old museum registrar from Holland, Michigan, said. “That’s when it brought to high relief that the Supreme Court is being used to skew the political environment we live in, and it’s only gotten worse.”

The poll of 1,088 adults was conducted June 20-24, 2024, using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 4.0 percentage points.

Beaumont reported from Des Moines, Iowa.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Political Typology Quiz

Where do you fit in the political typology, are you a faith and flag conservative progressive left or somewhere in between.

Take our quiz to find out which one of our nine political typology groups is your best match, compared with a nationally representative survey of more than 10,000 U.S. adults by Pew Research Center. You may find some of these questions are difficult to answer. That’s OK. In those cases, pick the answer that comes closest to your view, even if it isn’t exactly right.

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Technique improves the reasoning capabilities of large language models

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

Large language models like those that power ChatGPT have shown impressive performance on tasks like drafting legal briefs, analyzing the sentiment of customer reviews, or translating documents into different languages.

These machine-learning models typically use only natural language to process information and answer queries, which can make it difficult for them to perform tasks that require numerical or symbolic reasoning.

For instance, a large language model might be able to memorize and recite a list of recent U.S. presidents and their birthdays, but that same model could fail if asked the question “Which U.S. presidents elected after 1950 were born on a Wednesday?” (The answer is Jimmy Carter.)

Researchers from MIT and elsewhere have proposed a new technique that enables large language models to solve natural language, math and data analysis, and symbolic reasoning tasks by generating programs.

Their approach, called natural language embedded programs (NLEPs), involves prompting a language model to create and execute a Python program to solve a user’s query, and then output the solution as natural language.

They found that NLEPs enabled large language models to achieve higher accuracy on a wide range of reasoning tasks. The approach is also generalizable, which means one NLEP prompt can be reused for multiple tasks.

NLEPs also improve transparency, since a user could check the program to see exactly how the model reasoned about the query and fix the program if the model gave a wrong answer.

“We want AI to perform complex reasoning in a way that is transparent and trustworthy. There is still a long way to go, but we have shown that combining the capabilities of programming and natural language in large language models is a very good potential first step toward a future where people can fully understand and trust what is going on inside their AI model,” says Hongyin Luo PhD ’22, an MIT postdoc and co-lead author of a paper on NLEPs .