Home / Guides / Citation Guides / Citation Basics / Citing Evidence

Citing Evidence

In this article, you will learn how to cite the most relevant evidence for your audience.

Writing for a specific audience is an important skill. What you present in your writing and how you present it will vary depending on your intended audience.

Sometimes, you have to judge your audience’s level of understanding. For example, a general audience may not have as much background knowledge as an academic audience.

The UNC Writing Center provides a general overview of questions about your audience that you should consider. Click here and read the section, “How do I identify my audience and what they want from me?”

Addressing Audience Bias

In addition to knowledge, values, and concerns, your audience may also hold certain biases , or judgments and prejudices, about a topic.

Take, for example, the topic of the Revolutionary War. Your intended audience may be British economists who see the American Revolution as a rebellion, which hindered British imperialism around the world.

When writing for this audience, you still want to present your claims, reasoning, and evidence to support your argument about the American Revolution, but you don’t want to alienate your British audience. You will need to be sensitive in how you explain American success and its impact on the British Empire.

Quotes, Paraphrases & Audience

Using quotes and paraphrases is a terrific way to both support your argument and make it interesting for the audience to read. You should tailor the use of these quotes and paraphrases to your audience.

Evidence Sources & Audience

Whether you’re quoting or paraphrasing, the source of your evidence matters to your audience . Readers want to see credible sources that they trust.

For example, military historians may feel reassured to see citations from the Journal of Military History (the refereed academic publication for the Society for Military History) in your writing about the American Revolution.

They may be less persuaded by a quote from a historical reenactor’s blog or a more general source like The History Channel . Historical fiction or historical films created for entertainment likely will not impress them at all, unless you are creating a critique of those sources.

It can sometimes be helpful to create an annotated bibliography before writing your paper since the annotations you write will help you to summarize and evaluate the relevance and/or credibility of each of your sources.

Quoting/Paraphrasing with Audience in Mind

Choosing when to use quotes or paraphrases can depend on your audience as well.

If your audience wants details, if you want to grab the attention of your audience, or if audience bias may prevent acceptance of a more generalized statement, use a quote.

If your audience is new to the topic or a more general audience, if they will want to see your conclusions presented quickly, or if a quote would disrupt the reading of your text, a paraphrase is better.

Using Quotes and Paraphrases Effectively: Example

John Luzader, who has worked with the Department of Defense and the National Park Service, can be considered an expert who understands the technical aspects of military history.

Click here to read his “Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga.” As you read, consider whether you would quote or paraphrase this text when using it as evidence for a school newspaper article explaining why the British surrendered.

Quotes and Paraphrases Example: Explained

A high school newspaper’s audience is usually intelligent and informed but not expert. Unless it is a military academy’s newspaper, it is unlikely that the audience has enough expertise to understand specific technical terms like “redoubt,” “intervisual,” or “British right and rear.”

For this audience, Luzader’s Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga would work better as a paraphrase:

Military historian John Luzader (2010) argues that the British position on the field at Saratoga allowed the Americans to take the earthwork fort that protected the Redcoats and form a circle around the British, forcing their defeat.

Notice that the above paraphrase uses an in-text citation, which all paraphrases should. Because Luzader’s name is included in the sentence, we only need the year of publication (2010) in parentheses.

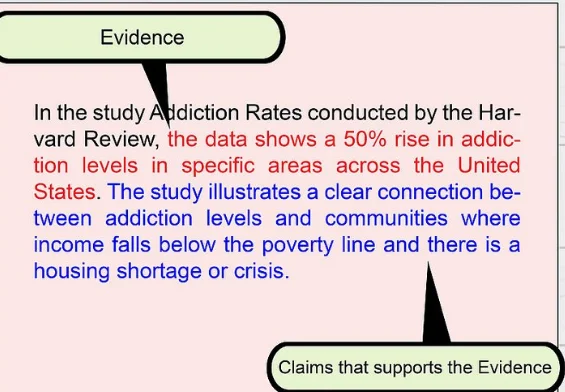

Relevant Evidence for Claims and Counterclaims

As a writer, you need to supply the most relevant evidence for claims and counterclaims based on what you know about your audience. Your claim is your position on the subject, while a counterclaim is a point that someone with an opposing view may raise.

Pointing out the strengths and limitations of your evidence in a way that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases helps you select the best evidence for your readers.

Relevant Evidence for Counterclaims: Example

Your audience’s concerns may include a counterclaim you must address. For example, your readers may think that the American Revolution cannot be considered a world war because it was a fight between one country and its colonies.

You should acknowledge these differences in beliefs with evidence, but be sure to return to your original claim, emphasizing why it is correct. Your acknowledgment may look like this (the counterclaim is in italics):

Although the American Revolution was primarily a battle between the British empire and its rebellious North American colonies , the foreign alliances made during the American Revolution helped the colonists survive the war and become a nation. The French Alliance of 1778 shows how foreign intervention was necessary to keep the United States going. As Office of the Historian for the U.S. State Department (2017) explains, “The single most important diplomatic success of the colonists during the War for Independence was the critical link they forged with France.” These alliances with other nations, who provided financial and military support to the colonists, expanded the scope of the Revolution to the point of being a world war.

Now you know how to select the best evidence to include in your writing! Remember to consider your audience, address counterclaims while not straying from your own claim, and use in-text citations for quotes and paraphrases.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Citing Sources Properly

Citing sources properly is essential to avoiding plagiarism in your writing. Not citing sources properly could imply that the ideas, information, and phrasing you are using are your own, when they actually originated with another author. Plagiarism doesn't just mean copy and pasting another author's words. Review Amber's blog post, "Avoiding Unintentional Plagiarism," for more information! Plagiarism can occur when authors:

- Do not include enough citations for paraphrased information,

- Paraphrase a source incorrectly,

- Do not use quotation marks, or

- Directly copy and paste phrasing from a source without quotation marks or citations.

Read more about how to avoid these types of plagiarism on the following subpages and review the Plagiarism Detection & Revision Skills video playlist on this page. For more information on avoiding plagiarism, see our Plagiarism Prevention Resource Kit .

Also make sure to consult our resources on citations to learn about the correct formatting for citations.

What to Consider

Citation issues can appear when writers use too much information from a source, rather than including their own ideas and commentary on sources' information. Here are some factors to consider when citing sources:

Remember that the cited material should illustrate rather than substitute for your point. Make sure your paper is more than a collection of ideas from your sources; it should provide an original interpretation of that material. For help with creating this commentary while also avoiding personal opinion, see our Commentary vs. Opinion resource.

The opening sentence of each paragraph should be your topic sentence , and the final sentence in the paragraph should conclude your point and lead into the next. Without these aspects, you leave your reader without a sense of the paragraph's main purpose. Additionally, the reader may not understand your reasons for including that material.

All material that you cite should contribute to your main argument (also called a thesis or purpose statement). When reading the literature, keep that argument in mind, noting ideas or research that speaks specifically to the issues in your particular study. See our synthesis demonstration for help learning how to use the literature in this way.

Most research papers should include a variety of sources from the last 3-5 years. You may find one particularly useful study, but try to balance your references to that study with research from other authors. Otherwise, your paper becomes a book report on that one source and lacks richness of theoretical perspective.

Direct quotations are best avoided whenever possible. While direct quotations can be useful for illustrating a rhetorical choice of your author, in most other cases paraphrasing the material is more appropriate. Using your own words by paraphrasing will better demonstrate your understanding and will allow you to emphasize the ways in which the ideas contribute to your paper's main argument.

Plagiarism Detection & Revising Skills Video Playlist

Citing Sources Video Playlist

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Synthesis

- Next Page: Not Enough Citations

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Most Popular

How to cite page numbers in apa.

12 days ago

How To Cite Journal Article MLA

How to cite evidence.

Image: unsplash.com

Citing textual evidence is critical to academic writing, professional communications, and even everyday discussions where arguments need to be supported by facts. Your ability to reference specific parts of a text improves credibility and strengthens your arguments, allowing you to present a well-rounded and persuasive case. For this reason, we wanted to give you a quick overview of how to cite evidence effectively, using one method in particular – the RACE strategy .

Introduction to Citing Text Evidence

The core reason for citing evidence is to lend credibility to an argument , showing the audience that the points being made are not just based on personal opinion but are backed by solid references. This practice is foundational in academic settings. There, the questions that students need to respond to are often constructed in a way that requires citing of evidence to support their answers. However, how can we make this process more quick and effectice? The answer lies in the RACE strategy, which is a special framework called to streamlines the process of citing textual evidence.

What is the RACE Strategy?

The RACE strategy stands for Restate, Answer, Cite evidence, and Explain. It is a methodical approach designed to help individuals construct well-structured answers that include textual proof. Let’s break down this method a little bit so you have some kind of impression on what we are going to talk about further.

- Restating the question or prompt in the introduction of the answer helps the writer to set the stage for a clear response.

- The direct answer, taht follows afterwards, presents the key point or thesis of the question.

- After we’e given an answer, we can move on to citing evidence, where we will integrate specific examples from the text to support the answer.

- Finally, we can move on to explaining our evidence. Here, it’s important to elaborating on how the cited examples support the argument we made.

This structured approach not only helps in organizing thoughts but also makes sure that the necessary components of a well-supported argument are present. Just like how to cite the constitution you have to be precise and factual. Let’s explore each step with actual examples to better illustrate how this strategy can help you with the process of citing textual evidence.

Restating basically means paraphrasing the original question or statement within your answer. This step demonstrates your understanding of the question and sets the stage for your response.

By answering directly, you respond to the question and therefore briefly present your main argument or thesis. You should stay clear and concise here, providing a straightforward statement of your position or understanding.

Cite Evidence

Citing evidence is where you integrate specific examples from the text to support your answer. This involves quoting or paraphrasing passages and pointing out where in the text your evidence can be found. Don’t forget to use quotation marks appropriately for direct quotes and to provide context for your citations or let a legal citation machine handle it.

For instance, to support the theme of racial injustice, you might cite evidence by saying,

When explaining, you elaborat on how your cited evidence supports your answer. This step connects your evidence back to your main argument, demonstrating a deeper understanding of the text.

After citing evidence, an explanation could be structured the following way,

To put it all together, here’s how an integrated response using the RACE strategy might look:

Response : ⬇

“The novel ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ primarily explores themes such as racial injustice and the loss of innocence. One of the central themes is racial injustice, which is depicted through the trial of Tom Robinson and its impact on the town of Maycomb. Harper Lee illustrates this theme through the character of Atticus Finch, who states, ‘In our courts, when it’s a white man’s word against a black man’s, the white man always wins.’ (Lee, 1960, p. 295). This quote highlights the deeply ingrained racial biases within the judicial system of Maycomb, underscoring the novel’s critique of racial injustice and its effects on individuals and society as a whole.”

By following the RACE strategy and using actual examples, you can effectively structure clear and relevant responses that add depth to your argumentation. This method not only help in organizing thoughts but also in demonstrating a deep understanding of the text and its main topics.

However, there are a few nuances that you have to be aware of. The first one is the use of quotation marks. Don’t forget them when referencing direct quotes from a text, as they indicate that you took those words verbatim. Furthermore, you have to understand and use citation styles relevant to the discipline or context you write on. This will help you appropriately format your references and avoid unintentional plagiarizing. A quick tip: sentence starters and tags for dialogue can also help with introduction of quoted or paraphrased evidence effectively, as they let the reader or listener easily follow the argument’s progression.

Adapting the RACE Strategy for Distance Learning

Even in the case of distance learnign , the RACE strategy remains a valuable tool for teaching students how to cite evidence effectively. Digital resources such as Google Docs often offer collaborative platforms where teachers can share templates, sentence stems, and color-coded examples to guide students through the response building process.

Moreover, interactive activities facilitated through online tools, can further engage students in practicing citing evidence, with digital resources providing immediate feedback and opportunities for revision. This adaptation help develop the skill of citing textual evidence even in a remote learning setting.

It’s hard to argue that citing textual evidence is useful skill that can help you get far in your academic writing as well as in other more professional fields. Following the RACE strategy and using our tips on referencing, you, as students, can create well-structured and compelling responses (which no professor could argue with).

How can I use the RACE strategy to improve my essay writing?

You can use the RACE strategy to structure your paragraphs or entire essays by ensuring that each section includes a restatement of the question (if applicable), a clear answer or thesis statement, cited evidence from your sources, and an explanation of how this evidence supports your argument. This approach can enhance clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness.

What are some tips for effectively citing evidence in my writing?

Some tips for effectively citing evidence are: using direct quotes from the text with proper quotation marks, paraphrasing accurately while maintaining the original meaning, providing specific examples, and ensuring that your citations are relevant and support your argument. Always include page numbers or other locator information if available.

Is the RACE strategy useful for standardized tests or only for classroom assignments?

The RACE strategy is beneficial for a wide range of writing tasks, including standardized tests, classroom assignments, and even professional writing. Its structured approach to constructing responses makes it a valuable tool for any situation requiring evidence-based writing.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Citation Guides

How to Cite Personal Communication in APA

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- SHA Libraries

- Write-n-Cite

- Citing and Referencing

- APA 7th: Evidence Summaries

- Vancouver/NLM: In-Text Citations

- Vancouver/NLM: Reference List General Rules

- Vancouver/NLM: Audio/Visual Media

- Vancouver/NLM: Books

- Vancouver/NLM: Book Chapters

- Vancouver/NLM: ChatGPT and Other AI Tools

- Vancouver/NLM: Collective Agreements (Union)

- Vancouver/NLM: Conference Presentations

- Vancouver/NLM: Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

- Vancouver/NLM: Drug Resources

- Vancouver/NLM: Evidence Summaries

- Vancouver/NLM: Images, Infographics & Videos

- Vancouver/NLM: Journal Articles & Preprints

- Vancouver/NLM: News Media & Blogs

- Vancouver/NLM: Poster Presentations & Lectures

- Vancouver/NLM: Policies, Guidelines & Standards

- Vancouver/NLM: Social Media

- Vancouver/NLM: Surveys, Questionnaires, Assessments

- Vancouver/NLM: Tables & Figures

- Vancouver/NLM: How to Format Tables & Figures in Doc

- Vancouver/NLM: Theses & Dissertations

- Vancouver/NLM: Websites

- AMA: In-Text Citations

- AMA: Reference List General Rules

- AMA: Audio/Visual Media

- AMA: Book Chapters

- AMA: Collective Agreements (Union)

- AMA: Conference Presentations

- AMA: Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

- AMA: Drug Resources

- AMA: Evidence Summaries

- AMA: Images, Infographics & Videos

- AMA: Journal Articles & Preprints

- AMA: News Media & Blogs

- AMA: Poster Presentations & Lectures

- AMA: Policies, Guidelines & Standards

- AMA: Social Media

- AMA: Surveys, Questionnaires, Assessments

- AMA: Tables & Figures

- AMA: How to Format Tables & Figures in Doc

- AMA: Theses & Dissertations

- AMA: Websites

- APA 7th: In-Text Citations

- APA 7th: Reference List General Rules

- APA 7th: Audio/Visual Media

- APA 7th: Books

- APA 7th: Chapters

- APA 7th: Collective Agreements (Union)

- APA 7th: Conference Presentations

- APA 7th: Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

- APA 7th: Drug Resources

- APA 7th: Images, Infographics & Videos

- APA 7th: Journal Articles & Preprints

- APA 7th: News Media & Blogs

- APA 7th: Poster Presentations & Lectures

- APA 7th: Policies, Guidelines & Standards

- APA 7th: Social Media

- APA 7th: Surveys, Questionnaires, Assessments

- APA 7th: Tables & Figures

- APA 7th: How to Format Tables & Figures in Doc

- APA 7th: Theses & Dissertations

- APA 7th: Websites

- Legal Materials

- Zotero: Get Zotero

- Zotero: Create a Reference

- Zotero: Save References

- Zotero: Select Output Style

- Zotero: Create a Bibliography

- Zotero: Cite While You Write

- Zotero: Share References

- Zotero: Remove Duplicates

- Zotero: Support

- EndNote: Get EndNote

- EndNote: Create a New Library

- EndNote: Create a Reference

- EndNote: Save References

- EndNote: Select Output Style

- EndNote: Create a Bibliography

- EndNote: Cite While You Write

- EndNote: Share References

- EndNote: Remove Duplicates

- EndNote: Retrieve Full-Text

- EndNote: Retracted Articles

- EndNote: Transfer References from Zotero

- EndNote: Support

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List General Rules

- Audio/Visual Media

- Book Chapters

- Collective Agreements (Union)

- Conference Presentations

- Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

- Drug Resources

Evidence Summaries

- Images, Infographics & Videos

- Journal Articles & Preprints

- News Media & Blogs

- Policies, Guidelines & Standards

- Poster Presentations & Lectures

- Social Media

- Surveys, Questionnaires, Assessments

- Tables & Figures

- How to Format Tables & Figures in Doc

- Theses & Dissertations

Summaries may include rapid reviews, reports, white papers, and/or point-of-care tools (e.g., DynaMed, BMJ Best Practice, etc.)

- << Previous: APA 7th: Drug Resources

- Next: APA 7th: Images, Infographics & Videos >>

- Request an article

- Request a search

- Request a training session

- Request library physical access

- Book a room

- Guidelines & Standards

- Register with the Library

- CoM Registration

- Download mobile apps

- Stay current with BrowZine

- Citing & Referencing

- [email protected]

- 306-766-4142

- Locations & Hours

- Terms of Use

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 3:30 PM

- URL: https://saskhealthauthority.libguides.com/citation

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, citation guide – learn how to cite sources in academic and professional writing.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Citation isn't just about adhering to prescribed rules or ensuring each dot and comma is in its rightful place. It's a rhetorical , fluid, intuitive process where writers must balance the authoritative voices of external sources with their own unique voice . Learn actionable strategies to weave sources into your writing .

For writers, learning how to cite sources in academic and professional writing is twofold: one aspect is rule-bound and procedural, while the other is open-ended and creative:

- Communities of practice — such as The APA – American Psychological Association or the MLA – The Modern Language Association — develop unique textual practices — including conventions for acknowledging, quoting , paraphrasing , and summarizing sources

- research the status of the scholarly conversation on any particular topic among domain experts (e.g., scholars, researchers and practitioners)

- engage in rhetorical analysis (especially audience analysis ) to determine the reader’s expectations regarding citation , media , genre , voice –and related matters

- realize, through drafting , what it is they want to say — and, consequently, whom they need to cite.

Key Concepts: Academic Dishonesty ; Attribution; Evidence ; Information, Data ; Archive ; Epistemology ; Plagiarism ; Textual Research ; Symbol Analyst ; The CRAAP Test

Introduction

Citation — the act of informing your audience when you integrate material into your work that originates from another source — is both (1) a procedural, rule-bound process and (2) a creative act.

Citation as a Procedural, Rule-bound Process

First and foremost, citation functions as a methodical, rule-driven process, where adhering to the conventions of specific citation styles is paramount. For instance, if you are a scientist attempting to publish an article in The New England Journal of Medicine , you would need to follow the ICMJE Recommendations or the Vancouver system to ensure your references are correctly formatted and accepted by the journal’s editors.

This procedural aspect of citation can be broken down into four main steps:

- Determine the Citation Style: Understand the specific citation style your assignment or publication demands, be it APA, MLA, Chicago, or others.

- Choose Your Citation Strategy or Tool: Opt for a strategy or citation tool to systematically track and organize your citations.

- Compose Citations: Ensure accurate representation for all material borrowed from other sources, be it summarized , paraphrased , or quoted .

- Review and Revise: As your work develops, rigorously verify that your citations — in-text (parenthetical, numbered, or note citations, and in the reference list — conform to the requirements of the required citation style.

For a deeper understanding of these basic steps, consult the following:

- Citation – When & Why You Must Cite Sources in Academic & Professional Writing

- Paraphrase – Definition & Examples – How to Paraphrase with Clarity & Concision

- Quotation – When & How to Use Quotes in Your Writing

- Summary – How to Summarize Sources in Academic & Professional Writing

Citation as a Creative Act

Beyond the specific conventions dictated by formats like APA or MLA , citation is fundamentally about joining an ongoing dialogue with fellow scholars, past and present. Thus, beyond being rule-bound, citation is also a rhetorical, creative act.

When writers summarize , paraphrase , or quote others, they’re not just borrowing words or thoughts. Instead, they’re actively positioning themselves within a broader, dynamic conversation that encompasses centuries of human thought and inquiry. Take, for instance, the act of referencing Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow” . Citing Alexander’s work is akin to stepping into an expansive auditorium, catching Alexander’s eye, and confidently contributing to a resounding, layered discussion. Happily, in attendance at the auditorium are all of the writers that Alexander quoted — and all of the authors those writers cited. And, streaming in the door are new authors who are eager to add their two cents to the conversation .

Here’s the bottom line: human nature instinctively pushes us toward collaboration and the sharing of knowledge . Across history, great thinkers have acknowledged and celebrated this collective instinct.

The Association of College and Research Libraries reinforces this through their “Scholarship as a Conversation ” framework. They posit that knowledge isn’t just a treasure waiting to be discovered but an ongoing dialogue to be engaged with. Within this context, citation isn’t just a formality; it’s an essential tether, anchoring our ideas to the vast mosaic of scholarly exchange.

Historical reflections affirm this communal approach to knowledge. Bernard of Chartres, in 1159, coined the metaphor of “dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants,” emphasizing our continuous build on the foundational work of predecessors. Similarly, Isaac Newton, in 1675, noted that his groundbreaking discoveries were possible due to the insights of those before him. In turn, Kenneth Burke’s ‘parlor metaphor’ offers a vivid portrayal of this timeless academic exchange. He likens it to a conversation that’s been underway long before we join in and will continue long after we’ve departed, with new voices continually enriching the discourse.

Today, platforms like Google Scholar echo this enduring philosophy, with its motto, “Stand on the shoulders of Giants.” It serves as a reminder that as we wade through the extensive realm of human understanding, citation acts as our guiding star – enabling us to both find our way and add our unique insights to humanity’s unending scholarly conversation.

How Can I Determine Which Citation Style to Use?

Each community of practice adopts its own discourse conventions for citation. For instance, a paper written for an English course might expect citations to follow the Modern Language Association (MLA) style, while a psychology research article would typically utilize the American Psychological Association (APA) format. Similarly, a historian might lean towards the Chicago Manual of Style. Thus, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to incorporating sources into your writing.

Thus, your first step when endeavoring to weave the ideas and words of others into your writing is to engage in rhetorical analysis :

- What citation format does your audience anticipate? This often hinges on the academic discipline, publication venue, or even a specific instructor’s preference.

- Do your readers prefer direct quotations , paraphrases , or a mix of both?

- How frequently do they expect sources to be cited?

- Are primary sources prioritized over secondary ones?

Is Using a Citation Tool a Good Idea?

Yes! Utilizing a citation tool scugh as Zotero can greatly benefit students and professionals alike for several reasons:

- Efficiency and Consistency: These tools automate the creation of citations and ensure consistency across all references, which is especially beneficial when handling multiple sources.

- Accuracy: Many citation tools extract data directly from journals, databases, or websites, which minimizes potential human errors in capturing details such as authors, publication dates, or titles.

- Adaptability: One of the notable benefits of citation tools is their ability to quickly switch between various citation styles. This is invaluable if you’re writing assignments for different courses or if you’re publishing in diverse venues with distinct citation requirements.

- Archival and Organizational Benefits: Citation tools store and organize references, providing a valuable archive of your reading history. This not only helps you keep track of sources you’ve read but also leverages your reading history to aid in future research or writing projects. The ability to categorize, tag, and annotate references can be a game-changer for extensive research projects.

- Cross-Platform Synchronization: Many citation tools synchronize across devices and platforms. This means you can access, add to, or edit your library from any device, ensuring seamless integration into your workflow.

When Should I Directly Quote a Source Versus Paraphrasing or Summarizing It?

Use a Direct Quote :

- When Original Phrasing is Important : Some authors have a unique way of expressing thoughts that can’t be recreated without losing its essence. If a particular turn of phrase or specific words are crucial, retain them.

- When It Supports Your Point Strongly : If a quote directly aligns with your argument and bolsters it more than a paraphrase or summary would, opt for a direct quote .

- For Credibility : Quoting renowned experts or primary sources can lend your work credibility . Direct quotes serve as evidence that your claims are rooted in established research or authoritative opinions.

Paraphrase :

- To Personalize Information : Paraphrasing allows you to present information in your voice . This not only showcases your understanding but ensures the information seamlessly blends with your narrative.

- To Simplify Complex Content : Some original texts may be laden with jargon or complex structures. Paraphrasing can distill these intricate concepts into more accessible language. It’s an opportunity to break down and explain content, making it easier for your audience to grasp.

Summarize :

- Providing an Overview : When you need to touch upon the general themes or major points of a large body of work without diving deep into specifics, summarizing is your go-to tool.

- Condensing Information : Summarizing is especially useful when dealing with lengthy sources. It allows you to present the core ideas succinctly, giving readers a snapshot of the content without overwhelming them with details.

How Can I Distinguish My Ideas from Those of My Sources?

It’s essential that writers neither claim others’ ideas as their own (which is plagiarism ) nor allow their original thoughts to be overshadowed by external sources. To ensure clarity for your readers, you must differentiate between your ideas and those of your sources.

Readers, moving from left to right, shouldn’t have to double back to figure out the origin of the information in a paragraph or section. Take Theresa Lovins’s essay, “Objectionable Rock Lyrics”, as an instance:

“Many Americans fear government intervention when it comes to human rights. They fear that government censorship of rock lyrics might lead to other restrictions. Then too, what would the guidelines be, who would make these decisions, and how might it affect our cherished constitutional rights? Questions like these should always be approached with serious consideration. We have obligations as parents to protect our children and as Americans to uphold and protect our rights. Therefore, it’s important to ask what effects proposals like Tipper Gore’s, president of PMRC, might have on our freedoms in the future. She recommends that the record companies utilize a rating system: X would stand for profane or sexually explicit lyrics, V for violence, O for occultism, and D/A for drugs/alcohol. The PMRC also suggest that the lyrics be displayed on the outside cover along with a general warning sticker which perhaps might read “Parental Guidance: Explicit Lyrics.” To date, record companies have not agreed to all these demands but some have decided to put warning labels on certain questionable albums (Morthland).”

While Lovins provides complete documentation for her source (i.e., Morthland), she doesn’t clearly delineate what precisely she’s borrowing from him. This ambiguity could be effortlessly addressed with a transitional phrase, such as, “In a recent examination of this controversy, John Morthland’s essay in High Fidelity notes that Tipper Gore has proposed…”. By doing so, Lovins ensures her audience knows exactly where her own thoughts conclude and Morthland’s begin.

First-time Introductions:

- MLA Style Example : “Before exploring the intricacies of cultural hybridity, it’s valuable to understand Homi Bhabha’s viewpoint. In The Location of Culture , he notes that mimicry often renders “the colonial subject… as a ‘partial’ presence” (Bhabha 123).”

- APA Style Example : “When assessing cultural hybridity, Bhabha (1994) in his seminal work, The Location of Culture , suggests that mimicry can make “the colonial subject… a ‘partial’ presence” (p. 123).”

Subsequent References:

- After the initial introduction, you can frequently refer just to the author’s last name. Only revert to the full reference if there’s ambiguity or if you’re switching to another work by the same author.

- Example : “As the discussion progresses, Bhabha (1994) further unpacks the intricate dynamics of post-colonial identities, emphasizing the transformative potential of hybrid cultures.”

Key Points to Remember:

- Clarity is Essential : Your audience should always be aware of whose perspective is being presented: yours or a cited source. Proper introductions and references prevent any mix-ups.

- Signposting is Beneficial : Using verbs like “claims,” “asserts,” or “proposes” acts as indicators that the ensuing information is from a cited work.

- Your Voice is Vital : Although external sources bolster your content’s credibility , your personal interpretations , analysis, and synthesis are what set your work apart. Make sure to regularly interject with your perspectives or evaluations of the cited material.

Why Should I End a Paragraph in My Own Voice Instead of a Quote or Paraphrase?

Your paper’s primary voice should be yours, highlighting your unique perspective and contributions. While it’s essential to support your claims with reliable evidence, the primary voice guiding the conversation should be yours. Each paragraph should start and conclude with your insights, ensuring your narrative remains central.

So, how can you, as a writer, effectively conclude a paragraph in your own voice?

- Echo key terms from the quotation or paraphrase in your concluding sentences.

- Identify connections between your viewpoint and the cited content.

- Align the quotation or paraphrase with the overarching aim of the paragraph or your main thesis.

- Draw from the source to craft a smooth transition to the subsequent paragraph.

Illustrative Example :

Main Point : The presence of plastics is ubiquitous in America, yet only a fraction are recycled.

Quotation : “In 2023, merely 8% of the entire plastic waste was redirected for recycling” (“Plastics”).

Initial Paragraph :

Every day, recyclable plastic items surround us. Found in shopping malls, restaurants, offices, schools, or homes, these plastics come as shopping bags, packaging, containers, and more. The choice arises: trash or recycle? The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) underscores, “only 8% of the total plastic waste generated in 2023 was recovered for recycling” (“Plastics”).

Drawback : The paragraph halts suddenly with the EPA’s statement.

Improved Conclusion :

This figure indicates that most of the plastic waste in 2023 remained unrecycled in America. Addressing this sizable non-recycling demographic with targeted campaigns might be the next strategic step.

Citations :

MLA: “Plastics.” EPA. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 16 Apr. 2023. Web. 26 Apr. 2023.

APA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Plastics. www.epa.gov/plastics.

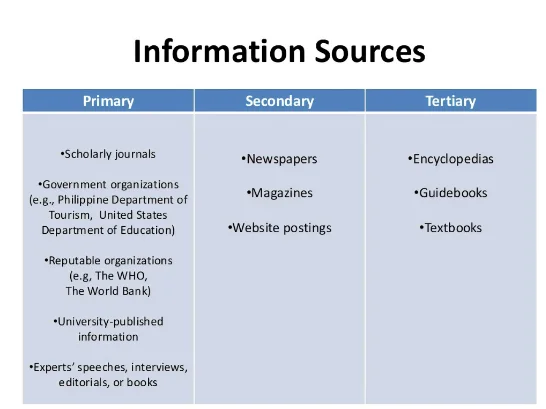

What’s the Difference Between a Primary and a Secondary Source, and How Might I Approach Integrating Each Into My Writing?

Understanding the distinction between primary and secondary sources is foundational for both academic and professional writing . These sources form the underpinning of our arguments and narratives . For instance, while a comprehensive report may state thousands are affected by an issue, often it’s the personal account of an individual that resonates profoundly with readers.

1. Definitions:

- Examples : Original documents (e.g., diaries, letters), raw data, artworks, and interviews.

- Examples : Articles, books, or documentaries that critique or comment on primary sources; literature reviews.

2. Strengths of Each Source:

Primary Sources:

- They offer firsthand, unvarnished insights.

- Allow readers to engage directly with raw evidence.

- Provide an authentic voice to a narrative.

Secondary Sources:

- They are part of the written archive, allowing other researchers to validate and engage with the information.

- Provide synthesized views, amalgamating various primary sources.

- Offer expert interpretations, shedding light on complexities and nuances.

3. Approaching Integration:

- Contextualize : Describe the broader setting or circumstances of the primary source. For a diary entry, detail the societal backdrop and key events of that time to anchor readers.

- Analyze : Examine the material’s themes, biases, and underlying messages, and explain its relevance to your argument.

- Reference Correctly : Given their place in the written archive, ensure bibliographic information is accurate so others can trace back to the original source.

- Discuss Specific Interpretations : When using a secondary source, highlight its unique perspective or analytical approach. For instance, if referencing a book review that offers a novel interpretation of a classic work, explain this viewpoint and its significance.

4. Balancing the Two:

The manner in which you integrate primary and secondary sources is influenced by the genre of your writing and the rhetorical strategies you’re employing:

- Purpose and Genre : If you’re writing a case study or ethnography , the genre itself dictates a heavier reliance on primary data, giving voice to firsthand experiences. Contrastingly, a literature review or meta-analysis would lean more on secondary sources to map out existing scholarship on a topic.

- Rhetorical Impact : Primary sources, with their raw and unmediated essence, can be powerful tools for ethos and pathos , grounding your narrative in authenticity and evoking emotional responses. Secondary sources, on the other hand, can bolster logos , providing scholarly depth, breadth, and validation to your claims .

- Crafting a Cohesive Narrative : Seamlessly weaving in primary and secondary sources isn’t just about juxtaposing raw data with textual research . It’s about crafting a narrative where each type of source complements the other. A quote from an individual might be the heart of your argument , but the scholarly discussions surrounding that quote give it context and broader significance.

How Can I Effectively Connect My Claims with Sourced Evidence?

Connecting your claims with sourced evidence is pivotal in academic and professional writing . It not only fortifies your arguments but also ensures that your readers understand the relevance of the evidence you’re providing.

1. Avoid Assumptions: Many writers think the relationship between their claim and the evidence is obvious. However, readers might not see the link as clearly. Hence, after presenting sourced material, always explain its significance to your point, purpose, and thesis.

2. Make Direct Connections: Consider the reader as someone who isn’t familiar with your topic. This means after introducing a quote or data, bridge it to your argument.

- Example: Palin suggests most of our oil is sourced from unstable regions. While this concern is valid, we believe offshore drilling poses a bigger economic risk.

- Example: Although Palin’s viewpoint underscores the significance of domestic oil production, it doesn’t consider the environmental risks associated with offshore drilling.

- Example: Despite arguments favoring offshore drilling, our stance is that its potential hazards far outweigh the benefits.

3. Engage with the Source:

- Explain the importance: Clarify why the sourced material is vital to your argument. Don’t assume the reader grasps its significance.

- Talk back to the source: Showcase your understanding and use it to bolster your stance.

- Discuss the implications: Dive into the consequences of your argument in light of the sourced material.

Ultimately, the goal is to ensure the reader comprehends how the evidence supports, complicates, or even challenges your claims. Remember, you’re not just citing sources; you’re weaving them into your narrative, making your arguments robust and nuanced.

APA Example: Flower and Hayes (1981) argue that many writers view writing as a “serendipitous experience, an act of discovery” (p. 286). This notion underscores the unpredictable nature of the writing process and suggests that exploring various writing methods can be a journey of discovery in itself.

MLA Example: According to Flower and Hayes, many authors perceive writing as “a serendipitous experience, an act of discovery” (286). This perspective highlights the evolving nature of writing, emphasizing the need to embrace diverse writing techniques.

How Can I Show the Relevance or Credibility of a Source to My Readers?

When you’re crafting an argument or presenting information , the strength and credibility of your sources are paramount. Especially in an academic or professional setting, readers seek evidence that’s not only compelling but also credible . Here’s how you can underscore the relevance and credibility of your sources:

- Highlight the Author’s Expertise: When referring to a notable author, highlight their qualifications and achievements in the relevant field. If you’re discussing the topic of grit and perseverance in writing and citing Angela Duckworth , an esteemed psychologist and author known for her work on this topic, leverage her credentials. Example: “Angela Duckworth, a celebrated psychologist and the author of Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance , argues that grit is a more significant predictor of success than talent.”

- Publication Type: University presses, often associated with established academic institutions, are generally held in higher regard compared to trade presses or self-publishing platforms like Amazon. This is because university presses often undergo rigorous peer- review processes .

- Journal Credibility: Is the journal you’re citing from peer-reviewed? Peer-reviewed journals maintain a stringent evaluation process where experts in the field review articles before publication. Journals published by professional societies, like the American Psychological Association, often carry weight due to their association with established experts in the field.

- Journal Rankings: In many professions, journals are ranked based on factors like citation rates and impact factor. Quoting from a top-tier journal can add gravitas to your argument. Example: “A recent study published in The Journal of Positive Psychology , a peer-reviewed journal ranked among the top 10 in the field, supports Duckworth’s theory…”

- Prioritize Recent Sources (When Applicable): In rapidly evolving subjects like technology or health, the currency of your source can attest to its relevance. Example: “In her 2023 Ted Talk, Duckworth updated her theory on grit by introducing…”

- Demonstrate How the Source Augments Your Argument: Seamlessly connect your source’s assertions to the point you’re underscoring. Example: “Duckworth’s emphasis on sustained effort aligns with studies on successful writers who, despite initial setbacks, persisted and improved over time.”

- Address Potential Bias: By identifying any inherent bias in your source, you enhance your credibility as a discerning researcher. Example: “Although the research was funded by the National Writers’ Association , its findings resonate with independent studies conducted at institutions like Yale and Cambridge.”

- Cross-reference with Other Credible Sources: Support from multiple authoritative sources reinforces the credibility of a point. Example: “This perspective on grit isn’t limited to Duckworth. Both The Journal of Educational Psychology and articles from the British Psychological Society have echoed similar findings.”

- Recognize Limitations: Accepting and indicating the limitations of a source showcases a balanced approach. Example: “Duckworth’s research, while pioneering, focuses mainly on students and educators. It’s essential to consider its applicability to writers from diverse backgrounds and experiences.”

Can I Ever Integrate a Source Without Directly Citing It in the Text? If So, How?

It’s essential to give credit to sources to maintain the integrity of your work and avoid plagiarism. While in-text citations are a direct way to do this, there are other methods to reference sources more discreetly:

- Endnotes or Footnotes: Some documentation styles permit the use of endnotes or footnotes instead of in-text citations. This method prevents the main body of your text from being disrupted by citations. Instead, you’d insert a superscript number that leads to a note at the end of your paper (endnote) or the bottom of the page (footnote) with the source’s full details. Example : You might write, “Grit, a combination of passion and perseverance, plays a significant role in achieving long-term goals[^1].” The corresponding note would provide the full citation for Angela Duckworth’s work on grit.

- General Bibliography/Works Cited: If you’ve integrated overarching ideas from a source, like Duckworth’s foundational theories on grit, but haven’t quoted or paraphrased a specific section, you might not need an in-text citation. Instead, Duckworth’s work would appear in a general bibliography or works cited page, signaling its influence on your understanding.

- Indirect Citations: There may be times when you encounter a perspective on Duckworth’s work cited in another author’s study. If you can’t access Duckworth’s original material, you can reference the intermediary source. Your citation method will vary depending on the documentation style. Example (in APA style): A recent interpretation of Duckworth’s theory, as discussed by Thompson (2022), suggests…

- Paraphrasing Broad Ideas: If you’re referring to widespread knowledge, like the basic definition of grit, you might not need an in-text citation. However, if you’re diving into detailed theories or unique interpretations specific to Duckworth, a citation is essential.

What about Newspapers & Magazines?

Mainstream publications, such as The New York Times or renowned magazines, adopt a different approach to referencing than scholarly or professional works. In these outlets, formal citation methods typical of academic journals aren’t always employed. Instead, there’s a general assumption that these publications have undergone a comprehensive editorial process, ensuring the information’s credibility. A key component of this process is the understanding that if readers or other stakeholders have questions regarding the sources of specific information, they can reach out to the author or publication directly to request these details. Thus, when you use information from such outlets in your writing, it’s essential to maintain this practice: always be prepared to direct readers to your primary source if questioned.

If I’m Reviewing Someone’s Research, How Much Detail Should I Provide about Their Research Methods?

If I’m Reviewing Someone’s Research, How Much Detail Should I Provide About Their Research Methods?

When reviewing another’s research, especially in academic or professional settings, it’s essential to strike a balance. You want to provide enough detail so readers can assess the study’s validity and relevance without overwhelming them with minutiae. The amount of detail needed can depend on your audience, the nature of the study, and the context in which you’re discussing it.

Consider the Purpose of Your Review :

- For Broad Overviews : When discussing the general findings of a study for a more general audience, a brief mention of the methods might suffice. E.g., “In her research on grit, Angela Duckworth conducted extensive surveys across diverse groups, finding a significant correlation between grit and long-term success.”

- For In-depth Analyses or Critiques : If you’re critiquing the study’s methodology or comparing methodologies across studies, you’ll need to delve deeper. E.g., “Duckworth’s study used a five-point Likert scale to measure respondents’ perseverance and passion for long-term goals, a decision that some researchers have debated due to potential response biases.”

- For Replication or Further Studies : If the aim is to allow others to replicate the study or to build upon it, every detail becomes vital, from the sample size to the statistical tests used.

Tips for Detailing Research Methods :

- Highlight Key Components : Describe the research design (e.g., longitudinal, experimental), the participants (sample size, demographics), the tools used (e.g., surveys, interviews), and the analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests, coding procedures).

- Address Potential Biases : For more critical reviews, discuss any potential sources of bias or limitations in the study. Was the sample representative? Were there any confounding variables?

- Compare with Other Studies : If relevant, compare the methods used in the research you’re reviewing with those of other similar studies. This can help readers gauge the study’s uniqueness or reliability.

- Use Visual Aids : Charts, tables, or diagrams can be beneficial in summarizing complex methods or when comparing methods across multiple studies.

For most college-level papers or articles, it’s advisable to include a clear and concise description of the research methods, allowing readers to gauge the study’s reliability and relevance to your discussion or argument. As you become more familiar with your audience and their expectations, you’ll develop a sense for the right level of detail to include.

How Do I Handle Sources From Non-Traditional Mediums, Like Podcasts, Tweets, or YouTube Videos?

In the digital age, research isn’t limited to books, journals, or articles. Multimedia platforms offer rich content that can be invaluable for your work. However, citing these non-traditional mediums can feel a bit daunting. Here’s a guide on how to navigate this terrain:

1. Podcasts:

- Host(s) of the episode.

- “Title of the episode.”

- Name of the podcast ,

- Production company or publisher,

- Date of publication.

- Platform (if applicable).

Example (in MLA style): Duckworth, Angela, host. “The Power of Grit.” Character Lab , Character Lab, 6 June 2021, characterlab.org/podcast/.

- Host(s) of the episode (Year, Month Day of publication).

- Title of the episode (No. episode number) [Audio podcast episode].

- In Name of the podcast .

- Production company or publisher.

Example (in APA style): Duckworth, A. (Host). (2021, June 6). The Power of Grit (No. 23) [Audio podcast episode]. In Character Lab . Character Lab.

- Author (individual or organization).

- Full text of the tweet.

- Twitter, Date of the tweet.

Example (in MLA style): Duckworth, Angela [@angeladuckw]. “Delving deeper into the nuances of grit and determination…” Twitter, 15 February 2022, twitter.com/angeladuckw/status/xxxxxx.

- Author (Year, Month Day of tweet).

- Full text of the tweet (up to the first 20 words) [Tweet].

Example (in APA style): Duckworth, A. [@angeladuckw]. (2022, February 15). Delving deeper into the nuances of grit and determination… [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/angeladuckw/status/xxxxxx

3. YouTube Videos:

- Author(s) or creator(s) (individual, group, or organization).

- “Title of the video.”

Example (in MLA style): Duckworth, Angela. “Exploring Grit in Education.” YouTube , 1 September 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxxxxx .

- Author (Year, Month Day of publication).

- Title of the video [Video].

Example (in APA style): Duckworth, A. (2021, September 1). Exploring Grit in Education [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxxxxx

- Citation formats might slightly change based on specific style guide versions or nuances. Always consult the relevant style guide.

- While MLA traditionally doesn’t include URLs, modern editions have adapted to the digital age by including them. Check with your instructor or publication’s preference.

How Do I Cite a Source That Was Quoted by Another Author I’m Reading?

When you come across a situation where you want to cite a quotation or idea that your primary source (the source you’re reading) has taken from another source (the original source), this is known as a secondary or indirect citation. It’s always preferable to locate the original source and cite from it directly; however, there are instances where this may not be feasible. In such cases, you’ll need to provide a citation that acknowledges both the primary and the original sources.

Here’s how you can handle secondary or indirect citations in both APA and MLA styles:

APA : When citing a source you found in another source, name the original author within your sentence, but follow it with “as cited in” and then immediately use the author, publication date, and page number (if available) of the secondary source in your parenthetical citation.

Example : Let’s say you’re reading a book by Thompson (2022) in which he quotes Duckworth (2007). You want to use Duckworth’s quote, but you can’t access her original work. Your in-text citation would look something like this:

Duckworth (2007, as cited in Thompson, 2022, p. 56) asserts that “grit is a combination of passion and perseverance.”

In your reference list, you would only include the secondary source, Thompson’s book, since that’s the source you actually read.

MLA : In MLA style, you’ll indicate the quote’s indirect nature in the in-text citation by using the phrase “qtd. in” (short for “quoted in”).

Example : Using the same scenario, your in-text citation would look like this:

Duckworth asserts that “grit is a combination of passion and perseverance” (qtd. in Thompson 56).

On your Works Cited page, you would only include a full citation for Thompson’s book, the secondary source you consulted.

Remember, using secondary citations should be an exception rather than the rule. Whenever possible, always try to consult and cite the original source directly to ensure the accuracy and context of the information.

Related Articles:

Citation - how to connect evidence to your claims, citation & voice - how to distinguish your ideas from your sources.

Citation Conventions - What is the Role of Citation in Academic & Professional Writing?

Citation Conventions - When Are Citations Required in Academic & Professional Writing?

Paraphrasing - How to Paraphrase with Clarity & Concision

Quotation - When & How to Use Quotes in Your Writing

Summary - Learn How To Summarize Sources in Academic & Professional Writing

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Jennifer Janechek , Eir-Anne Edgar

As you begin to incorporate evidence into your papers, it is important that you clearly connect that evidence to your own claims. Though connections may seem obvious to you, they...

- Jennifer Janechek

You don’t want to take credit for the ideas of others (that would be plagiarism), and you certainly don’t want to give outside sources the credit for your own ideas...

Explore the role of citation in academic and professional writing. Understand how citations establish trust, establish a professional tone, validate the authenticity of claims, and uphold ethical standards.

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the essentials of citing sources in writing, highlighting the criticality of acknowledging direct content use, respecting intellectual rights, and avoiding plagiarism, while enhancing content engagement and authority.

Master the Art of Paraphrasing: Explore the role of paraphrasing in academic and professional writing, its significance, the ethical imperatives behind it, and the skills required to paraphrase authentically. This...

Learn how to ethically condense content while ensuring your summary accurately reflects the essence of the original source. Summary also refers to a genre of discourse–such as an Abstract or...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

How To Do In-Text Citations in MLA Format: A Quick Guide for Students

An in-text citation is a reference to information originating from another source. In-text citations must be used when you summarize, quote, paraphrase or refer to another source within a written document, such as academic literature.

In-text citations are essential in academic writing. Without them, how would readers verify the information is reliable and accurate? Trustworthy authors include their sources for verifiable information rather than opinions so readers know where the evidence for claims can be explored further.

The Modern Language Association manages MLA style standards with the purpose to “strengthen the study and teaching of language and literature” and standardize how information sources are credited in scholarly writing. Not only does the MLA recommend proper citation format, but it also suggests proper general formatting, including document spacing, margins and font size.

As you begin authoring scholarly works, you’ll find the need to credit sources. Use this quick guide to learn how to do in-text citations in MLA format.

What is MLA format?

How to do in-text citations in mla, how to do a works cited page in mla, common challenges and solutions, tips for effective in-text citations.

MLA citation style is a system for crediting sources in scholarly writing and has been widely used in classrooms, journals and the press since 1931. What began with a three-page style sheet for the MLA’s scholarly journal became a uniform writing style preferred by academics and the editorial media everywhere.

Since its inception, the in-text citation style has changed from a recommended combination of footnotes and in-text citations in MLA format. The 1951 style guide suggested : “If the reference is brief, insert it, within parentheses, in the text itself . . . ; if it is lengthy, put it in a [foot]note.” As technology and society changed, so did the MLA style. In 1995, the document added recommendations for citing CD-ROMs and online databases. In 2016, the MLA published one of the most modern versions of the MLA Handbook , wherein in-text citations in MLA style should now be written according to a template of core elements.

The modern-day components of an in-text citation in MLA format, as of the ninth edition of the MLA Handbook , include:

- Author’s name

- Page numbers (if applicable)

These short in-text citations serve as references to a Works Cited list, which should follow a written piece of work and list all sources used in detail.

Authors who correctly use in-text citations in MLA style will prove their credibility, integrity and responsibility to share accurate and reliable information and simultaneously protect themselves from stealing sources and ideas from other writers, also known as plagiarism. Plagiarism is a severe offense , and many institutions have strict rules against the practice .

Now that you understand the importance of citations let’s review how to use in-text citations in MLA style. When referring to another author’s work in your own written text, you must use parenthetical citations, including the source in parentheses within the sentence that refers to the work.

If a source does not have page numbers, use another numbering system, such as chapters, sections, scenes or articles that are explicitly numbered. If there are no numbered divisions within the work, simply cite the author’s name.

The basic format for in-text citations in MLA writings is as follows:

- The pail of water was at the top of the hill, which Jack and Jill decided to climb (Mother Goose 1) .

If including a direct quote from a source, enclose the entire quote within quotation marks to avoid confusing the reader. The in-text citation should fall outside the quotation marks at the end of the sentence before the sentence’s period. Paraphrased information does not need quotation marks but does need proper in-text citation.

It should be noted that any information included in your in-text citations must refer to the source information on the Works Cited page listed at the end of your document.

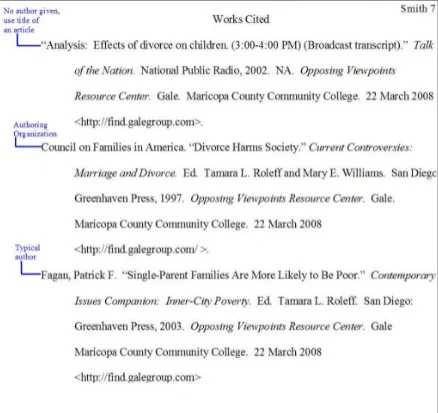

If you’re wondering how to list the references on the Works Cited page, the format varies depending on the type, such as a book or a website.

How to cite a book in MLA

- Author last name, first name. Title. Publisher, year.

How to cite an article in MLA

- Author last name, first name. “Article title.” Publication, volume/issue, publication month. Year, page numbers. Database, reference URL.

How to cite a website in MLA

- Author last name, first name. “Title.” Publication, publication month. Year, web page URL.

While constructing your paper, you may encounter a few citation challenges, such as a source with multiple authors or no known author. Though this can be confusing, this is how to use in-text citations in MLA style for challenging situations.

How to cite multiple authors in MLA

To write an in-text citation in MLA format for a source with multiple authors , simply list each author’s last name before the page number. Sources with more than two authors should cite the first author, followed by “et al.” For example:

- 2 authors: (Hall and Oates 1)

- 3+ authors: (Hall et al. 1)

How to cite sources with no author in MLA

Sources with no author must match the first listed element within its Works Cited entry. For example:

- In-text citation: (Baa, Baa, Black Sheep 0:15)

- Works Cited entry: “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep.” Spotify . https://open.spotify.com/track/1Zpe8ef70Wx20Bu2mLdXc1?si=7TlgCyj1SYmP6K-uy4isuQ

How to cite indirect or secondary sources in MLA

A secondary source is a publication that provides second-hand information from other researchers. You may use secondary sources in your research, though it’s best practice to search for the primary source that supplied the first-hand information, so cite it directly.

If you don’t have access to the original source, include the original author and the author of the secondary source , with the abbreviation “qtd. in” indicating where you accessed the secondary quote. “Qtd. in” stands for “quoted in.” For example:

- (qtd. in Baa, Baa, Black Sheep 0:15)

Using et al. in MLA citations

As described above, et al. is used instead of listing all names of three or more authors, editors or contributors within your citations. It can also cite collections of essays, stories or poems with three or more contributors. When using et al., you should always use the last name of the first writer listed on the source. For example:

- (Earth et al. “September” 0:15)

- Contributors: Earth, Wind and Fire

The most crucial part of in-text citations in MLA style is to keep a consistent and accurate format within the entire body of work. Always use the same punctuation within the in-text citations and the same formatting for sources of the same type. Ensure that double-checking citations is part of your overall proofreading process. All citations, like the written work, should be precise and error-free.

Various tools exist to help you collect and manage your sources and citations. Popular tools include Zotero , EndNote and RefWorks . These tools can create citations for you and keep track of your research documents so you can reference them again if needed. It’s wise to track your sources as they’re included in your writing rather than compiling and citing them when finished.

More resources for writing in MLA format

For the most up-to-date in-text citation information, refer to the MLA Handbook , which can be found online, in bookstores and libraries. The most recent edition of the MLA Handbook is the 9th edition, published in spring 2021.

The MLA also operates the MLA Handbook Plus , a subscription-based digital platform that offers all of the content included in the print edition, plus annual updates and valuable resources, and can be accessed anywhere, whether you’re traveling, at home or in the classroom.

The MLA Style Center offers free online sources on the official MLA style, including templates, questions and answers and advice.

Furman University offers trained consultants for students on campus to provide one-on-one or small-group assistance for writing projects at the Writing & Media Lab (WML). You can make an appointment with a WML Consultant or stop by the James B. Duke Library in the Center for Academic Success (room 002) for on-demand help (subject to scheduling).

The Writing & Media Lab can help with many tasks related to student writing and multimedia projects, including:

- Brainstorming a paper or project

- Outlining your ideas

- Reading through your writing

- Creating a presentation or poster

- Helping you practice your presentation

- Planning a video or podcast

- Revising, proofreading, or editing

Mastering the art of in-text citations in MLA format will ensure that you, as an academic author, will portray yourself as a serious, responsible and factual writer who uses accurate and reliable sources.

The perspectives and thoughts shared in the Furman Blog belong solely to the author and may not align with the official stance or policies of Furman University. All referenced sources were accurate as of the date of publication.

How To Become a Therapist

A brand strategy and creative thinking reflection | go further podcast, how to become a software developer.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Referencing | Cite Your Sources Correctly

Referencing means acknowledging the sources you have used in your writing. Including references helps you support your claims and ensures that you avoid plagiarism .

There are many referencing styles, but they usually consist of two things:

- A citation wherever you refer to a source in your text.

- A reference list or bibliography at the end listing full details of all your sources.

The most common method of referencing in UK universities is Harvard style , which uses author-date citations in the text. Our free Harvard Reference Generator automatically creates accurate references in this style.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Referencing styles, citing your sources with in-text citations, creating your reference list or bibliography, harvard referencing examples, frequently asked questions about referencing.

Each referencing style has different rules for presenting source information. For in-text citations, some use footnotes or endnotes , while others include the author’s surname and date of publication in brackets in the text.

The reference list or bibliography is presented differently in each style, with different rules for things like capitalisation, italics, and quotation marks in references.

Your university will usually tell you which referencing style to use; they may even have their own unique style. Always follow your university’s guidelines, and ask your tutor if you are unsure. The most common styles are summarised below.

Harvard referencing, the most commonly used style at UK universities, uses author–date in-text citations corresponding to an alphabetical bibliography or reference list at the end.

Harvard Referencing Guide

Vancouver referencing, used in biomedicine and other sciences, uses reference numbers in the text corresponding to a numbered reference list at the end.

Vancouver Referencing Guide

APA referencing, used in the social and behavioural sciences, uses author–date in-text citations corresponding to an alphabetical reference list at the end.

APA Referencing Guide APA Reference Generator

MHRA referencing, used in the humanities, uses footnotes in the text with source information, in addition to an alphabetised bibliography at the end.

MHRA Referencing Guide

OSCOLA referencing, used in law, uses footnotes in the text with source information, and an alphabetical bibliography at the end in longer texts.

OSCOLA Referencing Guide

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

In-text citations should be used whenever you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source (e.g. a book, article, image, website, or video).

Quoting and paraphrasing

Quoting is when you directly copy some text from a source and enclose it in quotation marks to indicate that it is not your own writing.

Paraphrasing is when you rephrase the original source into your own words. In this case, you don’t use quotation marks, but you still need to include a citation.

In most referencing styles, page numbers are included when you’re quoting or paraphrasing a particular passage. If you are referring to the text as a whole, no page number is needed.

In-text citations

In-text citations are quick references to your sources. In Harvard referencing, you use the author’s surname and the date of publication in brackets.

Up to three authors are included in a Harvard in-text citation. If the source has more than three authors, include the first author followed by ‘ et al. ‘

The point of these citations is to direct your reader to the alphabetised reference list, where you give full information about each source. For example, to find the source cited above, the reader would look under ‘J’ in your reference list to find the title and publication details of the source.

Placement of in-text citations

In-text citations should be placed directly after the quotation or information they refer to, usually before a comma or full stop. If a sentence is supported by multiple sources, you can combine them in one set of brackets, separated by a semicolon.

If you mention the author’s name in the text already, you don’t include it in the citation, and you can place the citation immediately after the name.

- Another researcher warns that the results of this method are ‘inconsistent’ (Singh, 2018, p. 13) .

- Previous research has frequently illustrated the pitfalls of this method (Singh, 2018; Jones, 2016) .

- Singh (2018, p. 13) warns that the results of this method are ‘inconsistent’.

The terms ‘bibliography’ and ‘reference list’ are sometimes used interchangeably. Both refer to a list that contains full information on all the sources cited in your text. Sometimes ‘bibliography’ is used to mean a more extensive list, also containing sources that you consulted but did not cite in the text.

A reference list or bibliography is usually mandatory, since in-text citations typically don’t provide full source information. For styles that already include full source information in footnotes (e.g. OSCOLA and Chicago Style ), the bibliography is optional, although your university may still require you to include one.

Format of the reference list

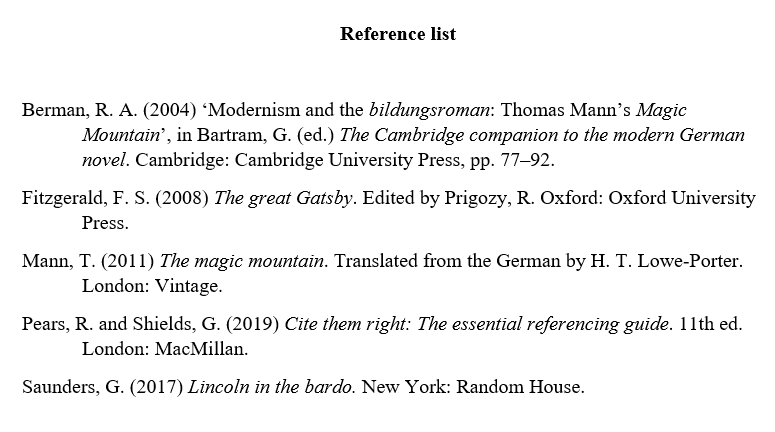

Reference lists are usually alphabetised by authors’ last names. Each entry in the list appears on a new line, and a hanging indent is applied if an entry extends onto multiple lines.

Different source information is included for different source types. Each style provides detailed guidelines for exactly what information should be included and how it should be presented.

Below are some examples of reference list entries for common source types in Harvard style.

- Chapter of a book

- Journal article

Your university should tell you which referencing style to follow. If you’re unsure, check with a supervisor. Commonly used styles include:

- Harvard referencing , the most commonly used style in UK universities.

- MHRA , used in humanities subjects.

- APA , used in the social sciences.

- Vancouver , used in biomedicine.

- OSCOLA , used in law.

Your university may have its own referencing style guide.

If you are allowed to choose which style to follow, we recommend Harvard referencing, as it is a straightforward and widely used style.

References should be included in your text whenever you use words, ideas, or information from a source. A source can be anything from a book or journal article to a website or YouTube video.

If you don’t acknowledge your sources, you can get in trouble for plagiarism .

To avoid plagiarism , always include a reference when you use words, ideas or information from a source. This shows that you are not trying to pass the work of others off as your own.

You must also properly quote or paraphrase the source. If you’re not sure whether you’ve done this correctly, you can use the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker to find and correct any mistakes.

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.