7 things you might not realize teachers have to do after the school day ends

- Teaching can be an extremely time-consuming career.

- Though the average American school day is only six and a half hours, teachers often spend additional hours grading, prepping school lessons, and giving students individualized help.

- Here are seven things teachers have to do long after the end-of-day school bell rings.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories .

Some people think that, as far as work hours go, teachers have it easy.

On paper, it's easy to see why one might believe this. The average American school day is only six and a half hours long , and teachers, like students, technically get summers off .

However, the amount of time students spend in school doesn't reflect the amount of work being a teacher actually entails.

Aside from planning lessons and grading them, two tasks which take up hours of time, there are other things teachers need to do outside of class every day in order to ensure their students are getting the most effective education.

Related: 10 alarming facts about teacher pay in the United States

We spoke to six teachers and asked them how much time they spent on their jobs outside of the classroom. Answers varied, but on average most said that they take home two to three hours of work a day. Additionally, nearly all of the teachers we spoke to said they come into school early, and stay around an hour late.

We also asked them what things take up the most of their non-teaching time. Their responses illustrated exactly how much work teachers do outside of school.

Here are seven things teachers have to do on their own time.

Teachers can spend hours grading their students' homework and tests.

When teachers give kids an assignment, they are also essentially giving themselves that assignment several times over. While they may not have to do the work itself, grading is not as simple as just writing a number or a letter on a paper.

Julia Van Ness, an eighth-grade special-education teacher from New Jersey, explained why this is.

"I like to go through and add comments to students' writing instead of just reading it and slapping a grade on it," Van Ness said.

"Plus, it takes more time when you have to weigh the papers against one another to ensure that your grading is universal," she said. "If Student A made one mistake and Student B made a similar but slightly different mistake, I often find myself deliberating for a few extra minutes on how their grades should reflect their work while being fair to both of them."

Stephen Van Ness, a seventh- and eighth-grade language arts teacher and Julia's husband, said it only takes him a few minutes to come up with weekly journal questions for his students, but it could take three hours or more to grade them for each student.

"Coming up with fun assignments for your classroom is enjoyable and exciting, but the stack of papers to grade in the aftermath? Much less so," he said.

Teacher prep periods can't always be used for prep.

Most schools give teachers what is called a prep period during the school day. This is a period of time, often around 45 minutes, that teachers are meant to use to prepare for their lessons, grade, and do other non-teaching tasks during the work day.

However, teachers might not always be able to use this period for its intended purpose.

One reason why is a simple lack of resources, Tori Van Horn, a second grade special education teacher from Pennsylvania, told Business Insider.

"There are other teachers that have prep at the same time as me, so sometimes making copies can be tough," she said. "I have my own laminator at home because my school's has been broken forever."

A bigger issue, though, is that her prep period doesn't allow her enough time to really focus.

"I'm interpreting a lot of data and coming up with specific goals for my students to work towards," she said. "I find it difficult to jump into a big legal document for only 40 minutes at a time. I need to sit and focus to make sure I'm doing my best work."

And other times, teachers simply need a break.

"Sometimes I just want to sit during my lunch," Julia Van Ness said. "After teaching for four hours straight and then covering lunch duty, I know I need to take a few minutes and just sit there to let myself recharge. I would rather finish something at home than let myself burn out by 3 o'clock."

Many teachers spend time on other school-related commitments like coaching sports teams, advising student clubs, or attending teacher meetings.

Even though almost all teachers come in to school early and leave late , you can't assume that all of that extra time is going to matters directly related to teaching.

"Teachers face numerous demands that aren't listed in our contracts," Julia Van Ness said. "Student situations, meetings, creating schedules or flyers for school events, and basically handling the day's chaos can leave you feeling like you got nothing done that day. Sometimes that's just how it goes."

Aside from attending departmental and training meetings, many schools have requirements that teachers help with a certain number of school-sponsored activities per year. This can mean chaperoning dances, monitoring lunch periods, or being on bus duty.

Other teachers with special interests may go above and beyond , becoming club advisers, theater directors, or sports coaches when the school day lets out. Music teachers often spend a lot of time outside of school hours on practices or concerts for student groups. Veteran teachers may take extra time to mentor new ones.

Planning lessons can take several hours a week.

For many teachers, planning lessons is one of the most time-consuming aspects of the job.

"I spend most time planning and prepping lessons for each day," Elizabeth Fela, a sixth-grade teacher from Illinois. "Planning for four different lessons a day is a lot of work. I make a lot of instructional materials myself. Not everything is provided to us, so I have to make assignments and games and all that on my own time."

Additionally, for some teachers, lesson planning doesn't always look like you might expect it to. Mary Saydah, who teaches special education in New Jersey, explained how her lesson planning can often involve a few extra elements .

"Most of my students are significantly visually impaired or blind, so for every lesson, I need an element they can explore either through touch or smell that relates to the lesson," Saydah said. "This can mean making a small mop out of popsicle sticks and yarn to represent an object in the story or having to make individualized worksheets for each student that I have to add numbers onto with puffy paint so they can explore it.

"It also means going to the store to buy materials a lot of the time," she continued. "When I lesson plan, I have to keep a running list of everything I need to make and buy for the following week. While I do get reimbursed, it is time-consuming to go to the store and find what I need"

Sometimes students need more individualized help, which means more time and paperwork customizing lesson plans.

For many teachers, especially teachers whose students have IEPs, or Individualized Education Plans, lesson plans need to be tailored specifically to fit each student's needs .

"My students are below grade level in different areas like reading and math," Stephanie Kay, a middle school special education teacher from Pennsylvania, told Business Insider. "I have to individualize different aspects of the curriculum so they can access it to the best of their ability. That involves writing each document (about 30 pages), making multiple attempts to call the parent to schedule the meeting, holding the meetings, and waiting for signed paperwork from parents."

Teaching students with IEPs also involves a lot more paperwork than other teachers normally see.

"I have to write IEPs for my caseload, give input for other students' IEPs, figure out what skills or concepts my kids need to be addressed in," Kay said. "I also have to find, print, and grade progress monitoring based on goals in their IEPs. I teach about 40 kids and have to monitor 27 goals."

Kay also mentioned that she holds IEP meetings with her students' parents on her own time.

Communicating with parents and students is another after-hours responsibility.

Many teachers spend time at home corresponding with teachers and students.

"For any one assignment, you could have a student who can't login to the website, forgot their paper at school, had sports practice all night and is asking you for extra time, doesn't understand the directions, and other sorts of excuses," Van Ness said.

"Responding to student and parent concerns can end up taking around 20 minutes depending on the day. Parent emails take me a while to write because often I reread them several times to ensure I communicated the information clearly in a friendly tone."

"It's something we spend a lot of time thinking about," Van Ness said.

And depending on the circumstances of their students, some teachers act as their caregivers, offering students emotional support and addressing behavioral issues.

When it comes down to it, teachers aren't just there to help students academically. They're also there to help their students grow as people.

Aside from teaching lessons, many teachers find that it is also their job to be a caregiver for their students, addressing behavioral issues, offering emotional support, and giving advice or guidance to students who come to them seeking it.

For some teachers, like Fela, this part of the job can be more time consuming than it is for others.

"My demographic presents a lot of social-emotional issues with students. Things like their parents being on drugs, being removed from their homes, not having a parent there when they get home, or sometimes not even having food at home, are problems my students deal with daily."

"We expect students to come to school ready to learn, when in reality they come to school to be safe and fed."

Fela explained that this part of the job isn't a separate responsibility — it's integral to helping students absorb the information they're being taught.

"Kids aren't ready to learn unless they have their basic needs met first."

- Main content

Every teacher grades differently, which isn’t fair

Assistant Professor of Teaching and Leadership, University of North Dakota

Disclosure statement

Laura Link consults with school districts through GradingRx.

University of North Dakota provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Students and parents have begun suing school districts over grading policies and practices they say are unfair.

As a scholar of education who studies grading practices, I’ve seen how important grades are to schools, students and their families.

Grades are the primary basis for making important decisions about students. They determine whether students are promoted from one grade level to the next. They also determine honor roll status and enrollment in advanced or remedial classes, and they factor into special education services and college or university admissions.

More than 1,800 colleges and universities now allow applicants to choose whether they want to take the ACT or SAT. That means grades are more important in admissions decisions and scholarship awards – and students and their parents know it.

In early 2022, a local political figure and his wife sued Baltimore Public Schools , claiming the city’s entire education system was not serving the public. They said unfair grading practices limited students’ academic access.

Later that year, a parent in Kentucky sued the local school district, alleging unfair grading practices had tainted remote learning classes that had been established during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Those cases are still pending, but even as far back as 2007 , parents sued a West Virginia school district because their daughter got a lower grade than expected on a biology project she turned in late. The lawsuit argued that the bad grade was unfair and hurt the student’s grade-point average, valedictorian status, scholarship potential and chances of getting into a good college.

These lawsuits show how important grades are to students and their parents.

Teachers spend lots of time grading

Teachers know how important grades are, too. In fact, teachers spend over one-third of their professional work time assessing and evaluating student learning.

But most university teacher-education programs focus on curriculum and instruction, with less attention given to assessment. My research has found that these programs do not talk about how to actually grade student work.

In keeping with a long-held tradition in education , teachers also have, and like, the autonomy to set their own practices. That results in inconsistency, inequity and even unreliability in teachers’ grading practices.

For example, teachers decide if grades will be based on tests, quizzes, homework, participation, behavior, effort, extra credit or other evidence. When surveying over 15,000 teachers, administrators, support educators, parents and students, I found teachers use a wide range of evidence in grades. While they primarily use tests, quizzes, projects, and homework to assign grades, teachers at all grade levels also include nonacademic evidence, like behavior and effort, in their grading equations.

Teachers also decide whether students will get a second chance to take tests if they fail on the first attempt, or be allowed to turn in work late, sometimes reducing their maximum possible grade.

Once teachers decide what to include in their grades, they decide how much weight to assign to each grade category. One teacher may weigh homework as 20% of the final course grade, while another teacher in the same grade level may choose a different weight or not grade homework at all.

In my work, I have talked to teachers who curve grades, especially at the end of a course when they discover lots of students did poorly. To curve, these teachers adjust grades by adding points to all students’ scores to bring the highest score up to 100%. Other teachers in the same school told me they do not grade on a curve. Instead, they add extra credit points to students’ final course grades if they attend a school event, such as a play. Some teachers told me they also add grade points if a student was never tardy to class or never missed an assignment deadline.

Traditional grading is confusing and inaccurate

Schools do often have a common grade system all teachers must use, such as a scale from zero to 100. But my research has found that it’s very rare that all teachers in a district, or even a school or a grade level, use the same grading policies and procedures.

The variation among teachers’ grading policies and practices causes confusion for students and their parents. High school students, for instance, typically have seven different teachers each semester. That means they have to keep up with seven different grading policies and procedures – and cope with the obvious differences.

My research indicates that the effort to keep up with multiple teachers’ different grading expectations causes students chronic stress and anxiety , especially for those students with poor organizational, time-management and self-regulation skills. This is also the case for students competing for high grade-point averages and class rank. Still, students rarely question teachers’ grading or the grading differences between teachers.

It might seem unfair, for example, that one algebra teacher allows for extra credit to boost final course grades and another does not. But students have accepted these differences because this is how it’s always been . And parents often pass these grading differences off as what they experienced in school themselves.

Three ways to improve grading

Grading consistency and effectiveness could be improved if universities’ teacher-training programs included specific training on grading practices in their educator preparation programs, but not any training will do. Evidence-based research on grading conducted over the past century identifies ways grades can be effective, fair and accurate .

First, grades are accurate and meaningful when they are based on reliable and valid evidence from classroom assessments. This information allows teachers to provide students and parents with feedback on learning progress, and to guide teachers’ own efforts to improve their teaching. For instance, an assessment strategy called Mastery Learning has been shown to improve student achievement and deliver reliable evidence upon which teachers can base grades.

Second, grading works best when students, parents, teachers, administrators and others in the school are clear on the purpose of grades . These groups have different beliefs and expectations, but clarity in grades can be achieved when they agree on grading intentions to then anchor policies and practices.

Third, grade reports that include three to five categories of performance more meaningfully communicate students’ actual academic proficiency . Reducing a grade to a single letter or number that incorporates many aspects of learning, including behavior and effort, does not inform anyone as clearly about what a student has achieved, needs or is ready for.

- Education equity

- Student grading

- Good grades

- educational attainment

- Higher ed attainment

- student grades

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Students Spend More Time on Homework but Teachers Say It's Worth It

Time spent on homework has increased in recent years, but educators say that's because the assignments have also changed.

Students Spending More Time on Homework

iStockphoto

High school students get assigned up to 17.5 hours of homework per week, according to a survey of 1,000 teachers.

Although students nowadays are spending significantly more time on homework assignments – sometimes up to 17.5 hours each week – the type and quality of the assignments have changed to better capture critical thinking skills and higher levels of learning, according to a recent survey of teachers conducted by the University of Phoenix College of Education.

The survey of 1,000 K-12 teachers found, among other things, that high school teachers on average assign about 3.5 hours of homework each week. For high school students who typically have five classes with different teachers, that could mean as much as 17.5 hours each week. By comparison, the survey found middle school teachers assign about 3.2 hours of homework each week and kindergarten through fifth grade teachers assign about 2.9 hours each week.

[ READ : Standardized Testing Debate Should Focus on Local School Districts, Report Says ]

By comparison, a 2011 study from the National Center for Education Statistics found high school students reported spending an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, while a 1994 report from the National Center for Education Statistics – reviewing trends in data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – found 39 percent of 17-year-olds said they did at least one hour of homework each day.

"What has changed is not necessarily the magic number of how many hours they’re doing per night, but it’s the quality of the homework," says Ashley Norris, assistant dean of the university's college of education. Part of that shift in recent years, she says, may come from more schools implementing the Common Core State Standards, which are intended to put more of an emphasis on critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

"You see a change from teachers … giving, really, busy work … to where they’re actually creating long-term projects that students have to manage outside of the classroom, or reading, where they read and come back into the classroom and share their findings," Norris says. "It's not just about rote memorization, because we know that doesn't stick."

For younger students, having more meaningful homework assignments can help build time-management skills, as well as enhance parent-child interaction, Norris says. But the bigger connection for high school students, she says, is doing assignments outside of the classroom that get them interested in a career path.

[ MORE : How Virtual Games Can Help Struggling Students Learn ]

Moving forward, as more schools dive into more time-consuming – but Norris says more meaningful – assignments, there may be a greater shift in the number of schools utilizing the "flipped classroom" method, in which students watch a lesson or lecture at home online, and bring their questions to the classroom to work with their peers while the teacher is present to help facilitate any problems that arise.

"This is already happening in the classrooms. And I think that idea, this whole idea where homework is this applied learning that goes outside the boundaries of a classroom – what can we use that actual class time for?" Norris says "To come back and collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique our own [work] and share those experiences."

Join the Conversation

Tags: K-12 education , education , Common Core , teachers

America 2024

U.S. News Live

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Surprise! 272K Jobs Added in May

Tim Smart June 7, 2024

U.S. News Summit Focuses on Equity

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton June 6, 2024

The Hunter Biden Trial, Explained

Laura Mannweiler June 6, 2024

Who Could Be Trump’s VP?

Lauren Camera June 6, 2024

What to Know: Bird Flu Death in Mexico

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder June 6, 2024

Mental Health on College Campuses

Sarah Wood June 6, 2024

Visit our sister organization:

THE LEARNING CURVE

a magazine devoted to gaining skills and knowledge.

THE LEARNING AGENCY LAB ’S LEARNING CURVE COVERS THE FIELD OF EDUCATION AND THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING. READ ABOUT METACOGNITIVE THINKING OR DISCOVER HOW TO LEARN BETTER THROUGH OUR ARTICLES, MANY OF WHICH HAVE INSIGHTS FROM EXPERTS WHO STUDY LEARNING.

Teacher Digital Feedback Tools Can Reduce Grading Time And Improve Instruction

- September 29, 2021

- No Comments

We surveyed 200 teachers and found widespread support for this sector of ed tech.

In December 2020, the Learning Agency Lab (the Lab) and Georgia State University (GSU) launched The Feedback Prize, to develop new, open source digital tools that can help students improve their writing and support teachers in their writing instruction.

Why? Well, there is strong evidence that assisted writing feedback tools (AWFT) can help students become better writers. Student achievement has dramatically outperformed state averages in districts that use Revision Assistant. And studies on the program Criterion have shown a positive impact for English Language Learners.

As a part of this work, my colleague and I surveyed 200 teachers across the nation to gain insights on how AWFT can support writing instruction. The survey was focused on AWFT and teaching context (ie: subjects taught, student population, etc.) as well as opinions on and concerns with AWFT and its potential impact in the classroom.

Our findings suggest that there are tremendous opportunities to support teachers with new tools. Consider that 90 percent of teachers surveyed believe that writing tools can help students to improve on their writing. Additionally, 95 percent of teachers are willing to try these tools. The responses suggest that teachers are open to using software and recognize the value of these tools, specifically when it comes to writing and writing instruction.

As technology becomes more ubiquitous in the classroom it is important to understand the needs and concerns of educators, especially in the writing classroom.

Teacher Practice

We surveyed teachers on their current writing instruction. We found that the most common writing approach taught was informative or explanatory writing. This suggests that students do not spend enough time practicing argumentative writing, although it is critical for college and career. These results align with survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which revealed that only 13 percent of eighth-grade teachers ask their students to write persuasively weekly.

Additionally we found that only 16 percent of teachers reported that students write more than a paragraph in class every day. Around 50 percent of teachers reported that their students only write more than a paragraph in class once a week or less. This means many students are not getting enough writing practice which would help them become more confident writers.

Time Spent Grading

When it comes to grading, more than 50 percent of teachers reported spending more than four hours grading student work a week. Of these teachers, only 16 percent report that most of their grading is focused on evaluating student writing.

While this seems like a small percentage, this is likely due to the low frequency at which teachers are assigning writing. Nearly 70 percent of teachers reported that they only ask students to write a paragraph or more for homework on a weekly basis or less. Considering the amount of time teachers already spend grading, asking students to write more would place more burden on teachers who are already overwhelmed with the amount of work they have to grade.

Use of AWFT

Our findings suggest that teachers are largely unaware of the current tools that are on the market, especially those that provide formative feedback. Only 28 percent of teachers reported using AWFT in their classroom. Of the teachers that did report using tools, Grammarly and CorrectEnglish were the most popular, even though both of these tools mainly focus on grammar and mechanics. While grammar skills are important for writing, students need more feedback on richer aspects of writing.

For example, only four teachers reported using Revision Assistant, which goes past grammar and spell check by providing students with instant and actionable feedback. This could be due to a number of factors, like accessibility and price points.

Tools like Grammarly and Correct English offer free versions of their product in addition to premium versions (up to $150/year). Both tools also offer Chrome extensions.

In comparison, Revision Assistant costs around $700/year. A MI Write subscription requires users to contact the company. Neither tool can be used with programs like Google Docs. This is likely a barrier to teachers who are willing to adopt new tools in their classrooms. While AWFT can support teachers and amplify their instruction, the ability to seamlessly integrate tools into existing platforms would likely lead to wider adoption.

Opinions of AWFT

While reported usage of AWFT was low, teachers are still very willing to try out AWFT in their classrooms. A whopping 95 percent of teachers are at least moderately willing to try these tools.

Additionally 90 percent of teachers believe that writing tools can help some or all students to improve on their writing. Even with limited awareness of AWFT, these findings suggest that teachers view these tools positively.

Concerns with AWFT

Of course, teachers still have concerns about integrating writing tools into their classrooms. The most popular of them being that students will use writing tools as a crutch. Teachers seem most worried that students using AWFT will allow the software to “do the work for them.”

This is understandable as many of the more common tools, like Grammarly, allow users to click on errors and replace them. While Grammarly provides an explanation of the error, it is likely that many students do not read these and do not have a solid understanding of the error made.

Tools that provide actionable and formative feedback can give students the clear next step. This would encourage students to think through the writing process and support them in working through revisions instead of providing them with the right answer.

Teachers are less concerned about tools replacing them, and seem to understand that these tools would be used in a support capacity. Other concerns that teachers have around AWFT are about navigating technology and the quality of feedback that software could provide. Tools that require a large amount of training will likely deter teachers and students from using them. Additionally, teachers were concerned that low quality or unclear feedback could be a problem with the tools.

Equity in the Classroom

At the Lab, one of our major goals with this work is to support equity in the classroom by producing high-quality, accessible tools. Teachers were optimistic about the potential for AWFT to support equity in the classroom. Over 90% of teachers surveyed believe that AWFT can be moderately helpful when working on writing with marginalized students. There are a number of ways teachers believe these tools can do this.

Teachers surveyed believe that AWFT could provide writing support to students outside of the classroom. Students in better resourced schools have more access to collaborative learning experiences and meaningful writing instruction. Students in lower resourced schools, however, tend to have larger classroom sizes meaning teachers have less time to provide feedback in class. AWFT can help increase the amount of meaningful writing instruction students receive by removing the burden on teachers to give feedback and giving students more opportunities to practice their writing.

Another way that these tools could support equity in the classroom is by providing content, prompts and features that support more relevant and personalized learning. For many students, especially struggling students, writing can be a frustrating task. Students can lose motivation if they are uninterested in the topics or have trouble understanding prompts. Tools that can be adjusted to fit with individual student needs can help teachers to ensure that students are receiving the instruction that they need to become better writers.

Finally, teachers believe that AWFT can provide support to English Language Learners (ELLs) who may struggle with basic writing skills by scaffolding their writing and providing actionable suggestions. ELLs often spend more time than their peers trying to find the right word or constructing sentences in English. Providing examples to ELLs, like sentence starters or predictive text can help students navigate the writing process while learning the English language.

Methods and Participant Information

Participants were recruited using Prime Panels, a participant recruitment platform that was developed by CloudResearch.

While Prime Panel participants are not exactly nationally representative, the distribution is broadly representative of the racial and ethnic diversity of the teaching workforce in the U.S. Consider:

- 90.5 percent of participants teach at public schools.

- 74.4 percent of participants have more than 5 years of teaching experience.

- 54.3 percent of participants teach at schools where most students are low-income.

- 32.7 percent of participants teach at schools with a high population of English language learners.

Overall, this survey suggests that there is huge potential for AWFT to impact writing instruction as we know it. These tools can be used to support teachers with their writing instruction by cutting down on the administrative burden of grading, as well as giving teachers more time to focus on high-level feedback. These tools can also provide students with more opportunities to practice writing and receive feedback outside of the classroom which would help them to become better writers. While these tools can have a large impact on writing instruction, it is imperative that developers keep teachers in the loop and that new tools address the needs of teachers and their students. Tools that are developed with a rich, contextual understanding of the writing classroom can greatly benefit teachers and students.

–Aigner Picou

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Disclosure: MyeLearningWorld is reader-supported. We may receive a commission if you purchase through our links.

7 Ways Savvy Teachers Save Time Grading Assignments

Published on: 12/19/2023

By Scott Winstead

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit

- Share on Pinterest

A recent report found that teachers spend about 5 hours each week grading assignments. And that’s time outside of regular school hours. Add in all of the other things teachers have to do outside of school hours, like lesson planning, meetings, and extra-curricular activities, and it can become overwhelming.

As a teacher, you’re already overworked (and likely underpaid) as it is. So, finding ways to save time grading can help you regain some of your valuable time so you can enjoy a life outside of school. The good news is, there are ways you can grade assignments more efficiently without sacrificing quality.

As someone who’s worked in eLearning for nearly 20 years and has numerous teachers in my network, I’ve put together a collection of highly effective tips for saving time on grading.

How to Save Time When Grading Student Work

Now that we’ve talked about why grades are important, let’s discuss some ways you can save time when grading student work.

1. Use technology to your advantage

Taking your classroom digital can help you significantly slash your grading time. In my opinion, it’s the single best way teachers can cut their grading time down significantly.

There are a number of digital resources available that can help you grade assignments more quickly and efficiently.

For example, online quiz makers and assessment tools can be a super easy and efficient way to administer tests as these tools grade tests and quizzes automatically. This frees up your time so you can focus on other tasks, like writing personalized feedback for students.

Another time-saving tech tool is a digital portfolio platform. These platforms allow students to submit their work electronically, which cuts down on paper waste and makes it easy for you to keep track of all assignments in one place. And, many of these platforms include features that make it easy to provide feedback directly on student work.

You can even use online gradebooks to keep track of student grades and provide feedback rather than doing it all by hand. These gradebooks often include features that automate the grading process, such as weighting assignments and calculating grades automatically.

The result is less work for you and better feedback for your students.

2. Get students involved in the grading process

Another great way to save time when grading is to get students involved in the process.

You can do this by teaching them how to grade their own or each other’s work. This can be especially helpful for assignments that are mostly objective, such as multiple-choice quizzes.

Of course, you’ll still need to check their work and ensure they’re being honest, but this can help cut down on your grading time.

Involving students actively in the grading process can also benefit them academically. They can learn how to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, as well as how to give and receive instant feedback that’s constructive and insightful.

3. Don’t grade everything

One of the biggest mistakes I’ve seen new teachers in particular make is thinking that they have to grade every single piece of work their students do.

This simply isn’t true.

In fact, grading every assignment can actually do more harm than good as it takes up a lot of time and can overwhelm students (and you!).

Instead of grading everything, focus on assessing the assignments that are most important. For example, you obviously want to grade major tests but not maybe every single homework item.

If an assignment doesn’t need to be graded in order to provide feedback, then don’t grade it.

For example, if you’re having students do a quick in-class writing exercise, there’s no need to grade every single one. You can simply read through them quickly and provide general feedback on what they did well and what needs improvement.

The key is to focus on the assignments that will give you the most information about student understanding and progress.

4. Create assignments that combine multiple subjects

Another way to save time when grading is to group subjects together into a single assignment for multiple grading opportunities.

For example, you could combine reading and writing skills with social sciences assignments. An essay on a social sciences topic could then be graded both as a writing assignment and as a social sciences assignment.

This can be an efficient way to grade as you’re able to kill two birds with one stone, so to speak.

Just be sure that the entire assignment is actually assessing what you want it to. You don’t want to overburden students or create an assignment that’s too difficult to complete.

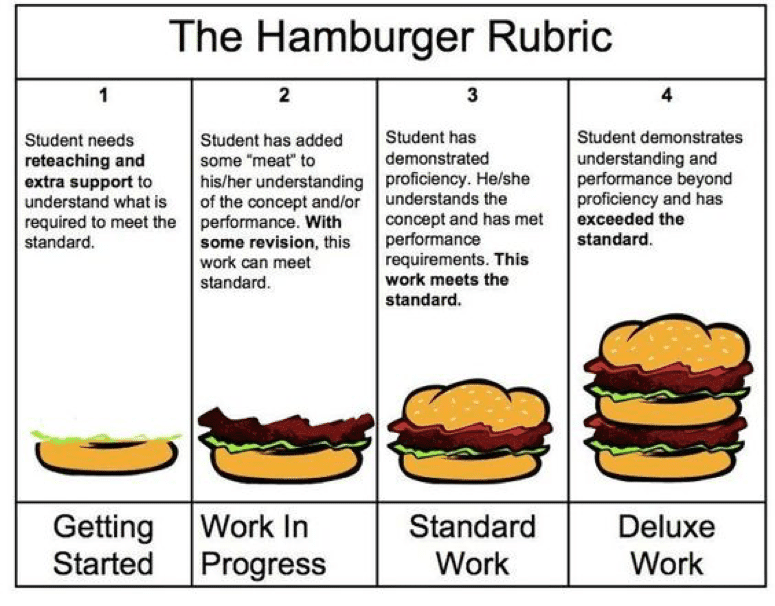

5. Use rubrics

Rubrics are a grading tool that can be used for any type of assignment.

They break down an entire assignment into its various parts and detail the criteria for each part. This makes it easy to assess student work and provide feedback.

Rubrics can also be helpful for students as they can see exactly what is expected of them and what they need to do to earn a good grade.

When using rubrics, you can either create your own or find ones that have already been created. There are rubrics available for almost any type of assignment you can think of.

6. Focus on quality of assignments, not quantity

Does a math assignment really need to have 40 repetitive questions covering the same concept over and over in order to be effective?

Probably not.

Sure, repetition can be helpful for some things, but it’s not always necessary. In fact, it can often be counterproductive as it can lead to students getting bored and feeling like they’re just going through the motions.

It’s important to focus on quality over quantity when creating assignments.

A shorter assignment with 10-15 questions can be plenty if it’s well-designed and covers the material in an effective way.

The key is to focus on creating assignments that are engaging and cover the material in a way that’s most likely to lead to students understanding it.

7. Do spot checks in real-time with in-class work

One easy way to cut down on time spent grading is to spot check your students’ work during class as you go through your lessons.

For example, if you’re working through some math problems, you can have students solve them on their own and then randomly choose a few to come up and solve on the board. Or they can hold up their answers for you to quickly check.

This will help you quickly assess who’s understanding the material and who needs more help.

It also allows you to provide immediate feedback and answer any questions students may have.

Doing spot checks like this throughout the semester can save you a lot of time in the long run as you won’t have to grade as much material at the end.

Final Thoughts

If you’re spending hours and hours grading assignments every week, you really need to make it a priority to find ways to save time. Otherwise, you’ll quickly become bogged down and burned out.

By following the tips in this article, you can make grading more efficient and less time-consuming without sacrificing quality.

So take the opportunity to implement a few of these time saving tips and see how they work for you. You may just find that your grading load becomes a lot more manageable.

How much time do you spend grading assignments each week? Let us know by leaving a comment below.

The 14 Best Educational Christmas Gifts for Kids

13 great ideas for student christmas gifts (all grade levels), leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Fast Grading: Time-Saving Tips for Grading Efficiently

But, frankly, it’s a lot. As soon as you knock out one stack, another pops up like a game of whack-a-mole. Sometimes you’ll be managing multiple piles at once, and keeping your head above water feels impossible. However, there are some practices that can help you save time. Here are a few I’ve learned over the years.

#1: Turn grading time into class discussions.

For daily grades–homework, classwork, pop quizzes–you can lead students in grading their own work.

There are so many reasons I love this method. (And honestly, saving grading time is just a happy byproduct.)

Additionally, you’ll quickly pinpoint widely-missed learning objectives, allowing you to double back and re-teach concepts with a new approach. It makes so much more sense to address gaps right in the moment rather than in a day or two after you’ve graded and handed back an assignment.

Another valuable effect is that students will quickly understand that their mistakes lead to learning opportunities . It helps build and sustain this classroom culture when students see that they are not the only ones missing something. “I’m actually really glad you missed that one” is an unusual but effective way to develop that culture.

And finally, yes – it saves you tons of grading time. You’ll want to monitor closely to be sure students are grading honestly, but you’ll spend way less time on it overall.

If you construct a solid rubric, the grading will fly by. In fact, the assessment will begin to feel almost automatic. Plus, a well-designed rubric can still allow for subjectivity in grading, showing students that it’s not just about checking off boxes but doing so in the best possible way.

Building a rubric takes some trial and error, but I promise you — once you have it down, it will save you gobs of time and will make your grading consistent and fair. You don’t have to start from scratch, either; Rubistar is a great (and free! ) place to get started.

#3: You don’t have to grade everything .

This doesn’t require much explanation, but rather a bit of instinct and professional judgment. Sometimes, you just need to let it go. Remember, the goal of any assignment is to demonstrate understanding . If you are able to see at a glance where your class is, don’t torture yourself with more grading. Save your energy for feedback and grading that will benefit the students more.

Obviously this won’t work for every assignment. You do need to monitor students’ progress towards mastery of skills and content knowledge.

However, there is value in trying, and students need to know that. True effort is key; check to be sure students have put their best first try out there. I like to walk with a clipboard and a grade sheet , checking off completed assignments as I walk around.

Here are some examples where this could be appropriate:

- First time attempting a new skill

- Writing/project checkpoints (brainstorming, outline, rough draft)

- Random homework checks

- Exit tickets/informal assessments

A high-tech option would be to create assessments using Google Forms (or a similar format). The objective portions are graded instantly and provide helpful data and feedback. They take some time on the front end, but (to me) it’s worth it.

A mid-tech option is the good old Scantron. These forms have saved me countless hours and are also a great way for students to practice for standardized testing. Additionally, some grading machines can provide data, alerting you to all kinds of useful info.

For my low-tech friends, create blank answer sheets for students to fill out for objective portions of tests. Make teacher keys. And if you grade stacks of tests by page, not by student, your brain will amazingly start to recognize patterns, expediting the grading process. Similarly, try to grade all of one assignment at a time rather than bouncing between different ones.

As you grow in your classroom career, you’ll develop your own time-saving practices. But these ideas can get you started and keep you from drowning in papers and red pens.

[…] being intentional about bringing work home can both help bring you balance and rest. Trying a few grading hacks can help as well. Promise yourself you’ll try something new this year and see if it […]

[…] Fast Grading: Time-Saving Tips for Grading Efficiently – Every Teacher, Every Day […]

By year three of teaching I was able to fit “grading” in during the school day. I made sure I did not have to bring home grading during the weekend. I prioritized that and if I had to work from home, did planning or creative works – rather then grading! I recommend the book: Project Plan for Teachers: Organize Your Classroom for Success! A great gift for teachers, as a planner, course supplement, or training tool…Project Plan for Teachers: Organize Your Classroom for Success (PPT) was designed for aspiring, new and veteran teachers to develop a blue print for their classrooms. Best used at the beginning of the year, or to reset mid-year… PPT uses graphic organizers, charts, project plans and bits of advice along the way to help make your academic year a success. A teacher’s blueprint, covering up to 35+ areas of focus during academic year the workbook will assist educators in building the classroom and career they have always wanted. Organizing for Accountability; helps to minimize the burden of the many tasks, but also helpful for cooperating teachers, teachers in training, coaches, trainers, school leaders and professors of education. Those leading workshops on Classroom Management, Teaching Strategies and Organizational Skills for Reflective Practitioners can benefit from reflection questions, activities or graph organizers to shape the training and the discussion. Book available online. Copies also available via [email protected] with discounts.

Thanks for the recommendation! So helpful!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Share this post!

End Of Year Teacher Memes

Why Teachers Should Travel During Their Summer

Summer Jobs For Teachers

Register to receive access to giveaways, gifts, and always-free resources.

" * " indicates required fields

WordPress Download Manager - Best Download Management Plugin

- Math Careers

Search form

- MAA Centennial

- Spotlight: Archives of American Mathematics

- MAA Officers

- MAA to the Power of New

- Council and Committees

- MAA Code of Conduct

- Policy on Conflict of Interest

- Statement about Conflict of Interest

- Recording or Broadcasting of MAA Events

- Policy for Establishing Endowments and Funds

- Avoiding Implicit Bias

- Copyright Agreement

- Principal Investigator's Manual

- Planned Giving

- The Icosahedron Society

- Our Partners

- Advertise with MAA

- Employment Opportunities

- Staff Directory

- 2022 Impact Report

- In Memoriam

- Membership Categories

- Become a Member

- Membership Renewal

- MERCER Insurance

- MAA Member Directories

- New Member Benefits

- The American Mathematical Monthly

- Mathematics Magazine

- The College Mathematics Journal

- How to Cite

- Communications in Visual Mathematics

- About Convergence

- What's in Convergence?

- Convergence Articles

- Mathematical Treasures

- Portrait Gallery

- Paul R. Halmos Photograph Collection

- Other Images

- Critics Corner

- Problems from Another Time

- Conference Calendar

- Guidelines for Convergence Authors

- Math Horizons

- Submissions to MAA Periodicals

- Guide for Referees

- Scatterplot

- Math Values

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Library Recommendations

- Additional Sources for Math Book Reviews

- About MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- MAA MathFest

- Proposal and Abstract Deadlines

- MAA Policies

- Invited Paper Session Proposals

- Contributed Paper Session Proposals

- Panel, Poster, Town Hall, and Workshop Proposals

- Minicourse Proposals

- MAA Section Meetings

- Virtual Programming

- Joint Mathematics Meetings

- Calendar of Events

- MathFest Programs Archive

- MathFest Abstract Archive

- Historical Speakers

- Information for School Administrators

- Information for Students and Parents

- Registration

- Getting Started with the AMC

- AMC Policies

- AMC Administration Policies

- Important AMC Dates

- Competition Locations

- Invitational Competitions

- Putnam Competition Archive

- AMC International

- Curriculum Inspirations

- Sliffe Award

- MAA K-12 Benefits

- Mailing List Requests

- Statistics & Awards

- Submit an NSF Proposal with MAA

- MAA Distinguished Lecture Series

- Common Vision

- CUPM Curriculum Guide

- Instructional Practices Guide

- Möbius MAA Placement Test Suite

- META Math Webinar May 2020

- Progress through Calculus

- Survey and Reports

- "Camp" of Mathematical Queeries

- DMEG Awardees

- National Research Experience for Undergraduates Program (NREUP)

- Neff Outreach Fund Awardees

- Tensor SUMMA Grants

- Tensor Women & Mathematics Grants

- Grantee Highlight Stories

- "Best Practices" Statements

- CoMInDS Summer Workshop 2023

- MAA Travel Grants for Project ACCCESS

- 2024 Summer Workshops

- Minority Serving Institutions Leadership Summit

- Previous Workshops

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Course Resources

- Industrial Math Case Studies

- Participating Faculty

- 2020 PIC Math Student Showcase

- Previous PIC Math Workshops on Data Science

- Dates and Locations

- Past Programs

- Leadership Team

- Support Project NExT

- Section NExT

- Section Officers Meeting History

- Preparations for Section Meetings

- Bylaws Template

- Editor Lectures Program

- MAA Section Lecturer Series

- Officer Election Support

- Section Awards

- Section Liaison Programs

- Section Visitors Program

- Expense Reimbursement

- Guidelines for Bylaw Revisions

- Guidelines for Local Arrangement Chair and/or Committee

- Guidelines for Section Webmasters

- MAA Logo Guidelines

- MAA Section Email Policy

- Section Newsletter Guidelines

- Statement on Federal Tax ID and 501(c)3 Status

- Communication Support

- Guidelines for the Section Secretary and Treasurer

- Legal & Liability Support for Section Officers

- Section Marketing Services

- Section in a Box

- Subventions and Section Finances

- Web Services

- Joining a SIGMAA

- Forming a SIGMAA

- History of SIGMAA

- SIGMAA Officer Handbook

- MAA Connect

- Meetings and Conferences for Students

- Opportunities to Present

- Information and Resources

- MAA Undergraduate Student Poster Session

- Undergraduate Research Resources

- MathFest Student Paper Sessions

- Research Experiences for Undergraduates

- Student Poster Session FAQs

- High School

- A Graduate School Primer

- Reading List

- Student Chapters

- Awards Booklets

- Carl B. Allendoerfer Awards

- Regulations Governing the Association's Award of The Chauvenet Prize

- Trevor Evans Awards

- Paul R. Halmos - Lester R. Ford Awards

- Merten M. Hasse Prize

- George Pólya Awards

- David P. Robbins Prize

- Beckenbach Book Prize

- Euler Book Prize

- Daniel Solow Author’s Award

- Henry L. Alder Award

- Deborah and Franklin Tepper Haimo Award

- Certificate of Merit

- Gung and Hu Distinguished Service

- JPBM Communications Award

- Meritorious Service

- MAA Award for Inclusivity

- T. Christine Stevens Award

- Dolciani Award Guidelines

- Morgan Prize Information

- Selden Award Eligibility and Guidelines for Nomination

- Selden Award Nomination Form

- AMS-MAA-SIAM Gerald and Judith Porter Public Lecture

- Etta Zuber Falconer

- Hedrick Lectures

- James R. C. Leitzel Lecture

- Pólya Lecturer Information

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- MAA Social Media

You are here

Teaching time savers: homework without grading, by john prather.

Experienced teachers are aware of the inherent tension in grading homework. On the one hand, students need feedback on the lessons, and the instructor needs to know how they are doing. Moreover, some students will not do homework that is not collected. On the other, homework is time-consuming to grade. More than that, many students will not even look at the comments that the teacher has written. And even if they do, by relying on the instructor?s grading students are not learning to assess whether what they have done is correct.

A solution to this tension occurred to me at a Project NExT workshop in which end-of-class one-minute essays were discussed. Adapting this idea to homework, I now require students to include a short cover page on every assignment in which they must briefly reflect on the material.

On the cover page, I ask students to answer three questions: First, what topic did you believe was the most important in the assignment? Second, why do believe that is the most important topic? Third, what problems did you have with the assignment, if any? The students are required to answer each question with a complete sentence, but, otherwise, the cover (and the assignment) is not graded outside of credit for turning it in. I do not look at the actual homework problems unless the students ask me to on the cover sheet, or if I need to see a student?s work to fully understand a question that is asked. I do occasionally peruse the assignments to make sure the students are making some attempt at the problems.

The first two questions give me feedback about what the students understand. More important, however, is the third question. Typically students will give me a list of exercises that they could not do, or did not fully understand. This gives me the opportunity to reply specifically to the students? needs. Therefore, I have some confidence that when I give them feedback on these questions, they will actually look at it. If many of the students have the same question, I can go over it in class, saving even more time. At other times, students reply to this question with personal problems external to the class. The cover page gives them an easy way to let me know what is causing them trouble without embarrassment. Occasionally, students will even notice patterns in the homework or will do problems differently than I did, and will want to know if the pattern or their methods will always work.

Of course, there are some students who do not understand problems in the assignment, yet do not write them on the cover sheet. Typically this happens because students thought they understood, because they are too embarrassed to admit the scope of their problems, or because they just don?t care enough to ask. The last group would not look at my comments even if I graded the entire assignment, and I approach them just as I would any other unmotivated students.

The students who are too embarrassed to ask their questions probably pose the greatest challenge in any class, but also require more intervention than homework can provide. For these students, the instructor can use the cover sheet to start a more general conversation. The group of students who thought they understood usually self-correct quickly due to feedback from frequent quizzes and in-class discussion of the homework.

While there can be some delay in correcting mistakes on individual problems, over time they also start to take more responsibility for their own learning. They get a better sense of when they do not understand something, and ask more questions later in the course. In the end, they become better learners than they were before.

I have been pleased by the effectiveness of this requirement. In addition to the information that I expected to get, there are other benefits. Since the sheet is due at the beginning of class, students have thought about the problems they are having before arriving which makes the students more prepared. Perhaps most importantly, the sheets start a dialogue, and that makes me more accessible. I think I get more students in my office than previously because of the covers.

In the end, I feel like the time I spend responding to the cover pages is well worth the effort, and is an effective way to communicate with students.

Time spent: About a minute per student per assignment. Time saved: About 1-5 minutes per student per assignment depending on how much time the instructor would otherwise spend grading.

John Prather is an Associate Professor at the Eastern Campus of Ohio University and would welcome any feedback on this article. He can be contacted at [email protected] .

Dummy View - NOT TO BE DELETED

- Curriculum Resources

- Outreach Initiatives

- Professional Development

- MAA History

- Policies and Procedures

- Support MAA

- Member Discount Programs

- Periodicals

- MAA Reviews

- Propose a Session

- MathFest Archive

- Putnam Competition

- AMC Resources

- Communities

Connect with MAA

Mathematical Association of America P: (800) 331-1622 F: (240) 396-5647 Email: [email protected]

Copyright © 2024

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Mobile Version

- Our Mission

How to Spend Less Time Grading

Carefully deciding what to grade and providing students with rubrics can make grading less time-consuming.

A few years ago, it wasn’t unusual for me to be up working at 10 o’clock at night. I’ve never been so busy in my whole life. What was taking up so much of my time? Grading.

I know that good-quality grading has the power to really make a difference to my students. I’ve read John Hattie’s research in Visual Learning —it’s all there in black and white. Good feedback can affect student progress more than factors such as socioeconomic background, behavioral interventions, or even prior achievement. My students deserve excellent feedback.

Yet grading was invading all of my free time. I was grading even when I wasn’t because the grading guilt was there all the time. Fast-forward to today. I’ve made it my life’s work to give my students the best possible education I can provide for them, but now I have my own family and far fewer hours to spare. So I’ve had to become very clever with giving feedback. I want to share a few tricks that may help save you hours a week, while still preserving the high standards you want for your work.

4 Tips to Help You Cut Your Grading Time Dramatically

1. Plan for less grading: I always say to my staff, “If a student writes it down, it needs to be marked—it just doesn’t have to be marked by you.” When you plan your lessons, consider the ratio of activities that require teacher assessment.

I organize my teaching in stages following Barak Rosenshine’s principles of instruction: explanation and modeling, then guided practice, and finally independent practice. All the practice, apart from the last stage of independent practice, is assessed by using mainly closed questions. By the time students produce answers to open-ended questions, they have had masses of practice, and there’s little to correct, making grading go by much quicker.

2. Grade less: When planning my lessons, in order to decide if something is worth grading, I think about impact and alternatives.

In terms of impact, will student learning be transformed by my grading this? Will I have time in the next lesson to allow students to reflect deeply on my feedback? Will I make them produce something that proves that they have learned from it? If the piece is marked for any reason other than impact, then it needs to be replaced by a different activity.

When time is tight, I think about alternatives. How can I check that students have learned a concept? Will a multiple-choice exercise do? Can I create a self-marked form that I can then recycle with other classes? Can I provide students with the answers and then give them time to reflect on how their answers could be improved?

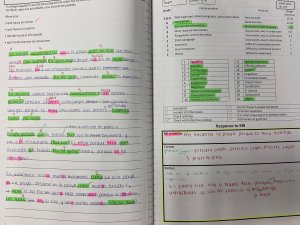

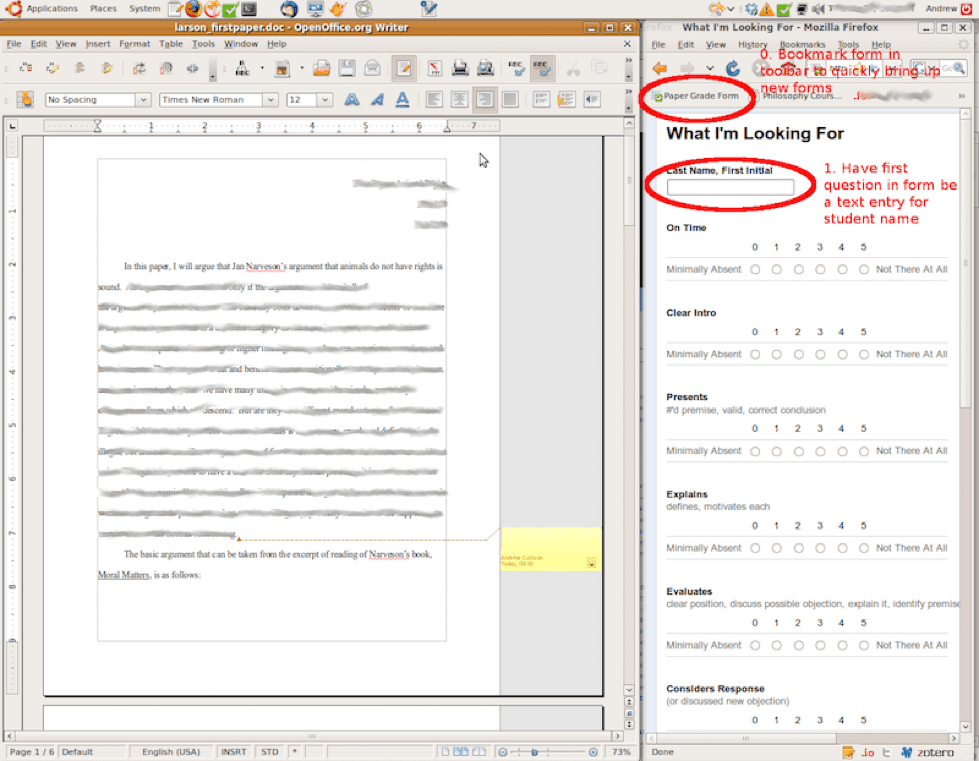

3. Unleash the power of rubrics or feedback sheets: One of my all-time time-saving favorites is my feedback sheet . It includes the criteria needed for earning each letter grade. To be more efficient, I use the same rubric for all of my students for every topic. Every year, I provide all of my classes with a student-friendly visual version of this sheet and go over what it means. I also model for my students how to use the sheet to grade an essay. The rubric is attached to every assessment, and I use it to grade every open-ended (usually essay) question.

Ask your students to use the rubric on their work before they submit it to you. Quality will improve, and the number of corrections will fall.

4. Speed up your grading: When it comes down to it, we can only reduce grading workload. We can’t eliminate it, nor should we. So how can we deliver maximum feedback with minimum effort?

The answer lies in training our students to turn a few visual cues into full-feedback messages.

These are the cues I use:

- If a student writes something that impresses me or goes beyond expectations, I highlight it in green.

- If a student meets the criteria for a grade, I highlight that part of the criteria using a green highlighter.

- If there is an error, I highlight it in pink.

- If a key part of the criteria hasn’t been met, I highlight it in pink.

- In a section called Even-Better-If (EBI), students complete a short (closed-ended, self-marked) task that matches the kind of errors they have made. This task is linked to the part of the criteria that I highlighted in pink.

- In a section called Correct, I write a word that students have misspelled in the text, and they need to copy it out three times.

- In a section called Perfect, students complete a short, open-ended task that will prove to me that they have taken in my feedback.

How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

- Share article

Editor’s note: This is an adapted excerpt from You, Your Child, and School: Navigate Your Way to the Best Education ( Viking)—the latest book by author and speaker Sir Ken Robinson (co-authored with Lou Aronica), published in March. For years, Robinson has been known for his radical work on rekindling creativity and passion in schools, including three bestselling books (also with Aronica) on the topic. His TED Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” holds the record for the most-viewed TED talk of all time, with more than 50 million views. While Robinson’s latest book is geared toward parents, it also offers educators a window into the kinds of education concerns parents have for their children, including on the quality and quantity of homework.

The amount of homework young people are given varies a lot from school to school and from grade to grade. In some schools and grades, children have no homework at all. In others, they may have 18 hours or more of homework every week. In the United States, the accepted guideline, which is supported by both the National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association, is the 10-minute rule: Children should have no more than 10 minutes of homework each day for each grade reached. In 1st grade, children should have 10 minutes of daily homework; in 2nd grade, 20 minutes; and so on to the 12th grade, when on average they should have 120 minutes of homework each day, which is about 10 hours a week. It doesn’t always work out that way.

In 2013, the University of Phoenix College of Education commissioned a survey of how much homework teachers typically give their students. From kindergarten to 5th grade, it was just under three hours per week; from 6th to 8th grade, it was 3.2 hours; and from 9th to 12th grade, it was 3.5 hours.

There are two points to note. First, these are the amounts given by individual teachers. To estimate the total time children are expected to spend on homework, you need to multiply these hours by the number of teachers they work with. High school students who work with five teachers in different curriculum areas may find themselves with 17.5 hours or more of homework a week, which is the equivalent of a part-time job. The other factor is that these are teachers’ estimates of the time that homework should take. The time that individual children spend on it will be more or less than that, according to their abilities and interests. One child may casually dash off a piece of homework in half the time that another will spend laboring through in a cold sweat.

Do students have more homework these days than previous generations? Given all the variables, it’s difficult to say. Some studies suggest they do. In 2007, a study from the National Center for Education Statistics found that, on average, high school students spent around seven hours a week on homework. A similar study in 1994 put the average at less than five hours a week. Mind you, I [Robinson] was in high school in England in the 1960s and spent a lot more time than that—though maybe that was to do with my own ability. One way of judging this is to look at how much homework your own children are given and compare it to what you had at the same age.

Many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all.

There’s also much debate about the value of homework. Supporters argue that it benefits children, teachers, and parents in several ways:

- Children learn to deepen their understanding of specific content, to cover content at their own pace, to become more independent learners, to develop problem-solving and time-management skills, and to relate what they learn in school to outside activities.

- Teachers can see how well their students understand the lessons; evaluate students’ individual progress, strengths, and weaknesses; and cover more content in class.

- Parents can engage practically in their children’s education, see firsthand what their children are being taught in school, and understand more clearly how they’re getting on—what they find easy and what they struggle with in school.

Want to know more about Sir Ken Robinson? Check out our Q&A with him.

Q&A With Sir Ken Robinson

Ashley Norris is assistant dean at the University of Phoenix College of Education. Commenting on her university’s survey, she says, “Homework helps build confidence, responsibility, and problem-solving skills that can set students up for success in high school, college, and in the workplace.”

That may be so, but many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all. Families have busy lives, and it can be hard for parents to find time to help with homework alongside everything else they have to cope with. Norris is convinced it’s worth the effort, especially, she says, because in many schools, the nature of homework is changing. One influence is the growing popularity of the so-called flipped classroom.

In the stereotypical classroom, the teacher spends time in class presenting material to the students. Their homework consists of assignments based on that material. In the flipped classroom, the teacher provides the students with presentational materials—videos, slides, lecture notes—which the students review at home and then bring questions and ideas to school where they work on them collaboratively with the teacher and other students. As Norris notes, in this approach, homework extends the boundaries of the classroom and reframes how time in school can be used more productively, allowing students to “collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique [each other’s work], and share those experiences.”

Even so, many parents and educators are increasingly concerned that homework, in whatever form it takes, is a bridge too far in the pressured lives of children and their families. It takes away from essential time for their children to relax and unwind after school, to play, to be young, and to be together as a family. On top of that, the benefits of homework are often asserted, but they’re not consistent, and they’re certainly not guaranteed.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Award-Winning!

How do I spend less time grading?

11 strategies for teachers to grade less and free up time.

Dedicated teachers are working so hard and are beginning to burn out . There is an easier way to free up your time and still help the students who need your support. Here are some techniques to help teachers spend less time grading and still give students the quality education they deserve .

How much time do teachers spend grading papers?

Teachers spend time grading papers during school, and they spend about another hour and thirty-five minutes at home grading. The time in a day spent grading can really add up for teachers.

How do I get caught up on grading?

If you’ve got grading stacking up, don’t worry. The first step is to come up with a plan. Prioritize the most important assignment first. Read on to see some of our tips to make grading more efficient.

Tips to make grading more efficient

Here are some tips to make grading more efficient. Try out a few so you can reclaim your nights and weekends!

Simplify your classroom grading policy

Teachers can simplify their grading by having two categories of grading. Major grading and minor grading are two categories of criteria for grading simplification. Teachers can also use checkmarks to simplify their grading. For example, they can use a check, check plus, check minus, or zero to simplify their grading policy.

Don’t grade everything

Have students do assignments that are similar to each other. Then ask the students to pick one of the assignments to be graded. The students should try to pick their best work for which assignment they want to have graded. This method works perfectly for times students need practice– like before a standardized test!

Prioritize the most important assignment for your grading time

Sometimes specific assignments can take longer to grade than others. Teachers can decide to start with the assignments that will take longer to grade and then work their way down to the easier-to-grade assignments.

Allow peer grading

Peer grading takes the pressure off of teachers for grading. Students can get together during class and grade each other’s papers. This way, the students learn from each other while grading during class.

Utilize daily formative assessments like bell work

Utilizing bell work for a productive grading time can be very efficient. First, teachers put a time on the assignment, and when the timer goes off, the students should finish with the assignment. Teachers then grade the assignments on a 1-3 scale (or their chosen scale).

Another way to do bell work assignments is by still setting a timer. However, after the timer goes off, teachers call on the students to explain their answers. Students then grade their papers based on the criteria that the teacher tells them to grade.

Bellwork is very efficient for grading because when the timer goes off, the students must stop their assignments and finish their work. Therefore, having an allotted time for work and grading allows teachers to limit their time on grading papers.

Get firmer on your regrade and late work policy

Being firm on your regrade and late work policy allows teachers not to have to grade late or already submitted papers. In addition, if teachers are firm on these policies, it allows them to catch up on assignments that were passed in on time and only once. Teachers do not have to grade assignments more than once or grade late work, which means less grading time for teachers.

Design assignments that require less grading

Designing assignments that require minor grading is a tactic teacher can use to help with grading. For example, teachers can look over assignments for completion while only grading essential parts instead of the entire assignment. This tactic is also known as spot grading.

Grade group work

Group work is more accessible to grade than individual grading. The students get together in groups and pass one assignment for the group. That means that the teacher only has to grade one assignment for multiple students rather than grading each student in the group on their work.

Spend the time on a detailed rubric or checklist

Spending time on a detailed rubric or checklist helps teachers and students with grading. The students can check their assignments based on the rubric or checklist before turning in assignments. With a rubric, the teacher can then quickly check off each criterion in the rubric rather than read the entire assignment in detail to grade based on a number scale.

Conference as students work rather than grade the end product

Checking in with students as they work helps limit grading time. For example, if the teacher checks the assignment while the students are working on it, the teacher can already know what grade the students will get. In addition, teachers can check off parts of the assignment and grade each part rather than wait for the entire assignment to be complete. This is the perfect task for larger and project-based assignments.

Which grading method is fastest?

Computer auto-grading is the fastest method for teachers to spend less time grading. The teacher does not have to do any physical grading once they set up the auto-grading worksheets. Many self-grading apps connect with tools that teachers use every day like Google Classroom, Schoology, Canvas LMS, and Microsoft Word.

Auto-grade worksheets and save time

TeacherMade is the perfect solution for when you need to save time grading. It’s simple to digitize worksheets with TeacherMade, and the best part is you never have to grade worksheets with TeacherMade’s self-scoring features.

Auto-grading worksheets are also helpful, interactive, and easy to use. Teachers put the auto-grading worksheets into TeacherMade. TeacherMade converts your worksheets for students to complete. Students then complete the assignment on the computer or device, and then TeacherMade auto-grades the assignment. You can create worksheets on paper, Google Docs, Microsoft Word, PDFs, or use worksheets in your file cabinet.

TeacherMade syncs up with all the major LMS platforms like Google Classroom, Canvas, and Schoology. So getting grades into your grade book is a breeze.

© 2024 All Rights Reserved.

- May 28 Engi-near the finish line

- May 17 Love is in the air

- May 11 Art Car Club showcases its rolling artwork on wheels at the Orange Show parade

- May 3 Cultures collide at the Bellaire International Student Association Fest

- May 2 Uncalculated uncertainties

Three Penny Press

Students spend three times longer on homework than average, survey reveals

Sonya Kulkarni and Pallavi Gorantla | Jan 9, 2022

Graphic by Sonya Kulkarni

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association have suggested that a healthy number of hours that students should be spending can be determined by the “10-minute rule.” This means that each grade level should have a maximum homework time incrementing by 10 minutes depending on their grade level (for instance, ninth-graders would have 90 minutes of homework, 10th-graders should have 100 minutes, and so on).

As ‘finals week’ rapidly approaches, students not only devote effort to attaining their desired exam scores but make a last attempt to keep or change the grade they have for semester one by making up homework assignments.

High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by the Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals. A survey of approximately 200 Bellaire High School students revealed that some students spend over three times this number.

The demographics of this survey included 34 freshmen, 43 sophomores, 54 juniors and 54 seniors on average.