- Maps & Data

- Priority Populations

- Connect & Share

- COVID-19 Economy Education Environment Equity Food Health Housing Mental Health Transportation

- Suggest a Resource

- Help & Support

An Introduction to Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA)

What is community health needs assessment.

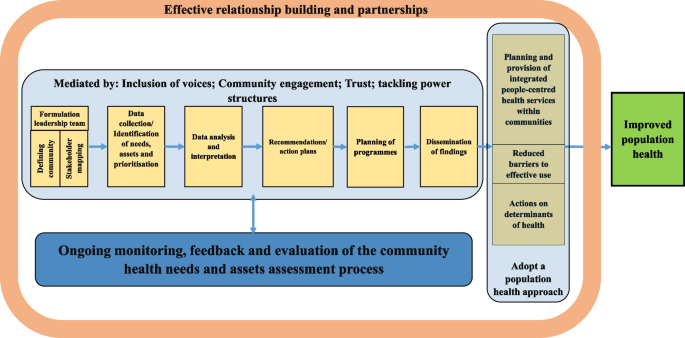

Community health needs assessment (CHNA) is a process for determining the needs in a particular community or population through systematic, comprehensive data collection and analysis, and leveraging results to spur community change. CHNA has long been best practice within the field of public health and prompts those working to improve community health to consider local conditions—both community needs and assets--which lead to more targeted, effective community-change work.

CHNA involves exploring both quantitative and qualitative data and can be broad, examining a community at large, or it can focus on a specific issue. Many communities and community organizations regularly conduct broad CHNAs to understand their community and get a pulse of what is most needed to promote community thriving. Public health departments and nonprofit hospitals are required to complete regular CHNAs to fulfill government requirements (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) requires tax-exempt hospitals to conduct a CHNA every three years alongside stakeholders.) In addition, a community might perform a CHNA focused on a specific topic, like opioid and substance use disorders, to inform a grant application or strategic plan to decrease local rates of substance use and overdose.

Tool - Data/mapping Tool

Brought to you by ip3.

PLACES: Local Data for Better Health

Dataset - data/mapping tool, brought to you by cdc.

Community Health Needs Assessment

Topic - data & assessment.

CARES Engagement Network

Brought to you by cares.

From 500 Cities to data for all PLACES

Story - original, brought to you by community commons.

The Science of Thriving

Community Needs Assessment

Topic - possibilities, a holistic approach to chna.

CHNA is a common, widely-accepted practice within the fields of public health and health care, and the practice is applicable to any sector and/or initiative that seeks to advance equitable community well-being. Due to its widespread use by local public health agencies and organizations, as well as hospitals and hospital systems, there is potential to drastically improve the healthcare landscape and advance community well-being through improving the CHNA process. In recent years, many have advocated for the integration of more non-health data into CHNA (e.g. housing data, transportation data). Adoption of a more general, well-being frame alongside traditional health outcome data, acknowledges the interconnectedness of our physical health to the community conditions in which we live. Specifically, many have used the seven vital conditions for well-being framework to examine how the healthcare system can contribute to advancing community well-being outside of its traditionally clinical sphere.

Organizing Around Vital Conditions Moves The Social Determinants Agenda Into Wider Action

Brought to you by health affairs.

An Introduction to Data Equity

An Introduction to Data Frameworks

Seven Vital Conditions for Health and Well-Being

Advancing equity through chna.

While CHNA is a long-established process in the field of public health and other related fields, there are records of misusing CHNA results to further-marginalize communities of color, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ groups, and other underserved populations. In order to advance equity through the CHNA process, we must approach CHNA in new, more inclusive ways. Careful conduction of CHNA that implements best practices (outlined below), including a community-driven process that engages people with lived experience in the community, can help identify root causes of inequity with regards to community conditions and health care, driving efforts to reverse these trends and improving health for all.

Vulnerable populations are at risk for disparate healthcare access and outcomes because of economic, cultural, racial, or health characteristics. For example, historically, communities of color have borne a larger burden of negative health outcomes than their white counterparts. There are myriad reasons for this, including a national legacy of systemic racism, disparities in health care access, coverage, and quality, and more. Throughout the CHNA process, examining data across different populations is important and allows you to see that people in your community have different lived experiences, resulting in different health risks and needs. If data cannot be broken out by race, for example, you’ll likely miss important differences in health needs across populations; your data won’t show health disparities. Knowing the specific health needs a population faces enables you to tailor health improvement efforts to appropriate priority populations and work to minimize disparities and promote an equitable approach to health improvement planning.

The Data Equity Framework

Brought to you by we all count.

An Introduction to the Burden of Disease Framework

An Introduction to Health Equity

Community engagement.

Ideally, CHNAs are developed through a collaborative process, involving stakeholders from various sectors, and take into consideration present-day data quantitative and qualitative data, as well as historical data, in order to examine change over time and trend lines. Community engagement can make the community a part of the CHNA process, rather than just the subject of it, and increases the likelihood that the CHNA will achieve its desired impact of building a healthier community and advancing equitable well-being.

Those who are closest to the problems we face have more knowledge about the nature of the problems and their root causes—often learning from those most affected leads to more effective, efficient, often multi-solving implementation strategies. Without community engagement, we fail to integrate the wisdom and experience of communities.

Focus Groups

Dialogue as a Process for Community Change

An Introduction to Local Data

Chna best practices .

CHNA is a complex process, often involving stakeholders from multiple sectors, organizations, and departments. There are many approaches to CHNA and an overwhelming amount of information available to guide the process. Our team has done research to discover and outline a list of best practices below.

Co-Design Processes and Solutions for Equitable Outcomes

Even before the CHNA work has begun, it's important to co-design the anticipated process with stakeholders and people in the community with lived experience. Co-designing processes ensures that people are on the same page at the onset of the work and should include designing processes for collecting, incorporating, and sharing data, as well as prioritizing areas for investment to advance equitable well-being. When more people are involved in designing a process for assessment and implementation planning, the work will take into consideration more lived experiences, and in turn, account for the needs of more people in a community.

Shift Power to Advance Shared Ownership, Action, and Wealth

Cultivating a culture of shared ownership of community well-being sets the stage for an effective community assessment—it's important that there is a shared definition of what well-being looks like in a given community. A culture of shared ownership around assessment and improvement planning includes community involvement and leadership with the design, data, processes, solutions, investments, and results.

Cultivate Shared Stewardship, Governance, and Investment for Accountability and Efficiency

Creating shared stewardship, governance, and investment is more than simply engaging the community—it means people feel invested enough in the process that they want to work together to enhance, maintain, and ensure the health of our systems. Together, shared ownership of community assessment, and co-designing of the process, pave the way for shared stewardship. Throughout the assessment, this includes data systems and implementation planning that is not top-down. In order to effectively advance equitable well-being, we must invoke reflective leadership, prioritize together, and collaborate to accomplish goals and act on priorities. Ideally, everyone who is part of a community has incentive to participate in bettering the community because they want to benefit themselves, and importantly, trust that everyone will reap the benefits (not just a subset of people).

Emphasize Assets and Strengths to Reinforce and Expand Community Resilience

Emphasizing community assets and strengths in assessment involves, first, deeply committing to the belief that communities (and their shared knowledge, cultures, and existing solutions) have immense value, and second, leading with that belief during every phase of community assessment.

Operationalize and Institutionalize Equity, Justice, and Accessibility for Mutual Liberation

Operationalizing and institutionalizing equity and justice in community assessment means that processes, activities, systems, assessment phases, and leading practices are rooted in and center equity actions , including antiracism, decolonization, accessibility, and justice. It's not always clear how to operationalize equity in community assessment—consistently reflecting on the process and questioning how we are considering and centering equity throughout each phase is helpful. Considering equity implications and operationalizing equity are not the same: at its core, equity means ensuring every person has the resources they need to produce outcomes and opportunities, and to build power. This demands proactive reinforcement of assessment and planning processes, practices, and mindsets that produce equitable power, access, opportunities, treatment, and outcomes for all.

Multi-Solve for Intergenerational Well-Being, Equity, and Sustainability

Multi-solving calls on systems stewards to work together and imagine solutions that efficiently and effectively solve complex systems challenges facing our communities. Multi-solving recognizes siloed solutions are ill equipped to solve problems at scale, and gains across multiple interrelated issues are possible. Solutions that are multi-solving in nature should be investment priorities--in that they are efficient and effective solutions for multiple, interrelated issues. Through collaboration we can identify and act on innovative, multi-solving solutions.

Foster Narrative Change to Move Hearts, Minds, and Systems

Narrative change is a tool for building public and political will to advance policy and systems transformation for health, well-being and equity. Public narrative is grounded in shared values, beliefs, norms, and assumptions that shape a collective worldview. Narrative is produced through stories that build on these commonalities, ultimately guiding behaviors and influencing how we co-create our destiny. Through narrative change strategies that use the power of story we can intentionally shift from harmful values, beliefs, norms and assumptions to those with the power to bridge divides, overcome impasses, and improve well-being and equity.

Infuse Belonging and Civic Muscle to Build Positive Community Momentum

Higher levels of social cohesion are associated with higher levels of trust, cooperation and social capital, providing the necessary foundations for creating healthy patterns for working together across groups and sectors, building the “civic infrastructure” for community members to co-create a shared future. These patterns can create a virtuous cycle—working together supports building stronger communication, develops a sense of connectedness and mutual obligation. As the sense of being valued and cared for within a community grows, people become more confident and willing to participate in the community, contributing to its vibrancy and affecting change.

CHNA to Catalyze Community Change

CHNA should catalyze community change, not just check a box—the most important consideration for CHNA is the action taken based on the results. Once you know where your community’s biggest assets lie and what the biggest needs are, you can use that information to create a plan and take action towards a healthier, more equitable community.

Data frameworks provide a powerful tool when using data to inform planning efforts to improve community conditions—they translate data into a solution through sorting indicators into categories that are easily tied to action. When examining data to inform an implementation plan, long lists of indicators aren’t helpful because they fail to shed light on levers you can actually pull to improve your community. Frameworks include categories that reflect common community programming, such as transportation, and housing, and thus make it easier to go from community insight to concerted action.

Stewardship, especially shared stewardship that engages people, organizations, local communities, etc., in collaborative work, is a promising mechanism by which we can shift investments and systems to support thriving communities. Stewardship is defined as “the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care” and is a good approach to acting on CHNA results to improve communities. Stewardship describes leaders—both people and organizations—who take responsibility for forming working relationships to drive transformative change in regions and communities. Importantly, stewards must have a vested interest in promoting an equity orientation in regard to purpose, power, and wealth.

5. Co-Design - Engaging People with Lived Experience

Tool - toolkit/toolbox, brought to you by 100mhl, published on 09/10/2020.

Belonging and Civic Muscle

Civic Infrastructure for Recovery

Story - written, brought to you by medium, published on 07/15/2021.

Changing Narratives and Moving Mindsets

Resource - website/webpage.

Bridge-Building and Power-Building: An Ecosystem Approach to Social Change

Brought to you by horizons project.

Listening to the Community's Input: A Guide to Primary Data Collection

Resource - guide/handbook, brought to you by walhdab.

Co-Design/Distributed Leadership Debrief Discussion Tool

An Introduction to Stewardship

Thriving Together: A Springboard for Equitable Recovery and Resilience in Communities Across America

related topics.

Item has been added to your favorites!

Community Health Assessments & Health Improvement Plans

What is a community health assessment, what is a community health improvement plan, why complete an assessment and improvement plan.

A community health assessment (sometimes called a CHA), also known as community health needs assessment (sometimes called a CHNA), refers to a state, tribal, local, or territorial health assessment that identifies key health needs and issues through systematic, comprehensive data collection and analysis. Community health assessments use such principles as

- Multisector collaborations that support shared ownership of all phases of community health improvement, including assessment, planning, investment, implementation, and evaluation

- Proactive, broad, and diverse community engagement to improve results

- A definition of community that encompasses both a significant enough area to allow for population-wide interventions and measurable results, and includes a targeted focus to address disparities among subpopulations

- Maximum transparency to improve community engagement and accountability

- Use of evidence-based interventions and encouragement of innovative practices with thorough evaluation

- Evaluation to inform a continuous improvement process

- Use of the highest quality data pooled from, and shared among, diverse public and private sources

From Principles to Consider for the Implementation of a Community Health Needs Assessment Process [PDF – 457KB] (June 2013), Sara Rosenbaum, JD, The George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, Department of Health Policy.

The Public Health Accreditation board defines community health assessment as a systematic examination of the health status indicators for a given population that is used to identify key problems and assets in a community. The ultimate goal of a community health assessment is to develop strategies to address the community’s health needs and identified issues. A variety of tools and processes may be used to conduct a community health assessment; the essential ingredients are community engagement and collaborative participation. — Turnock B. Public Health: What It Is and How It Works. Jones and Bartlett, 2009, as adapted in Public Health Accreditation Board Acronyms and Glossary of Terms Version 1.0 [PDF – 536KB] , July 2011.

The Catholic Health Association defines a community health needs assessment as a systematic process involving the community to identify and analyze community health needs and assets in order to prioritize these needs, and to plan and act upon unmet community health needs.” —Catholic Health Association, Guide to Assessing and Addressing Community Health Needs [PDF-1.5MB] , June 2013.

A community health improvement plan (or CHIP) is a long-term, systematic effort to address public health problems based on the results of community health assessment activities and the community health improvement process. A plan is typically updated every three to five years.

The Public Health Accreditation Board defines a community health improvement plan as a long-term, systematic effort to address public health problems on the basis of the results of community health assessment activities and the community health improvement process. This plan is used by health and other governmental education and human service agencies, in collaboration with community partners, to set priorities and coordinate and target resources. A community health improvement plan is critical for developing policies and defining actions to target efforts that promote health. It should define the vision for the health of the community through a collaborative process and should address the gamut of strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and opportunities that exist in the community to improve the health status of that community. — Public Health Accreditation Board Acronyms and Glossary of Terms Version 1.0 [PDF – 536KB] , July 2011, as adapted from Healthy People 2010 and CDC’s National Public Health Performance Standards Program .

A community health assessment gives organizations comprehensive information about the community’s current health status, needs, and issues. This information can help develop a community health improvement plan by justifying how and where resources should be allocated to best meet community needs.

Benefits include

- Improved organizational and community coordination and collaboration

- Increased knowledge about public health and the interconnectedness of activities

- Strengthened partnerships within state and local public health systems

- Identified strengths and weaknesses to address in quality improvement efforts

- Baselines on performance to use in preparing for accreditation

- Benchmarks for public health practice improvements

Links to nonfederal materials are provided as a public service and do not constitute an endorsement of the materials by CDC or the federal government, and none should be inferred. CDC is not responsible for the content of materials not generated by CDC.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Related Links

Exit notification / disclaimer policy.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

11.1 Health needs assessment

- Published: November 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter begins with a consideration of the technical processes used for conducting health needs assessment. The relationship between health needs assessment and health economics is then examined and the philosophy of utilitarianism and its influence on health economics is explored. Cost utility analysis and its links to studies of quality of life are described and the important relationships between equity and efficiency are considered. The chapter then proceeds to explore the political and philosophical issues attaching to health needs assessment. This leads to an elaboration of the concept of justice derived from the work of Sen. Using ideas about the importance of human capabilities an argument is developed about the relational approach to understanding justice. The relational as against the individualistic position is found to provide a novel and useful way of describing health need and of attempting to meet that need. It also provides a set of precepts about the ways that services might be configured.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Health Needs Assessment

- First Online: 27 April 2016

Cite this chapter

- Patrick Tobi 3

4178 Accesses

Health needs assessment (HNA) is one of the approaches used to provide intelligence and inform decision-making on the planning and deploying of resources to address the health priorities of local populations. Need is an important concept in public health but is also a multifaceted one that represents different things to different people. From a public health perspective, need is seen as the ‘ability to benefit’, which means that there must be effective interventions available to meet the need. In present-day public health practice, assessing the health needs of local populations typically involves considering not just their physical and mental health and well-being, but the wider determinants or social factors, such as housing, employment and education that influence their health. This chapter describes the historic development of health needs assessment and its use in contemporary public health practice. The different ways in which need is perceived and their implications for the health service are discussed. A step-by-step guide through the HNA process is outlined and comparisons are made with other overlapping approaches to assessment. The practical challenges of carrying out HNAs are highlighted and case studies are used to illustrate real life experiences.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to :

Discuss the concepts of need, want and demand.

Describe what is meant by a health needs assessment (HNA) and the different approaches that currently influence thinking and practice underpinning HNA.

Identify the key steps and practical challenges involved in conducting a HNA.

Compare HNA with other overlapping assessment approaches.

Understand, through case studies, how HNA is applied in practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bradshaw, J. R. (1972). The taxonomy of social need. In G. McLachlan (Ed.), Problems and progress in medical care . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Bradshaw, J. (1994). The conceptualisation and measurement of need: A social policy perspective. In J. Popay & G. Williams (Eds.), Researching the people’s health (pp. 45–57). London: Routledge.

Cavanagh, S., & Chadwick, K. (2005). Health needs assessment: A practical guide . London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health . Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies.

Department of Health. (2007). Guidance on joint strategic needs assessment . London: DoH.

Elkheir, R. (2007). Health needs assessment: A practical approach . Retrieved September 29, 2015, from http://www.sjph.net.sd/files/vol2i2p81-88.pdf.

Hooper, J., & Longworth, P. (2002). Health needs assessment workbook . London: Health Development Agency.

Powell, J. (2006). Health needs assessment: A systematic approach . London: National Library for Health.

Quigley, R., Cavanagh, S., Harrison, D., Taylor, L., & Pottle, M. (2005). Clarifying approaches to assessment: Health needs assessment, health impact assessment, integrated impact assessment, health equity audit, and race equality impact assessment . London: Health Development Agency.

Rogers, C., & Fox, R. (2005). Health needs assessment . Wales: National Public Health Service for Wales.

Stevens, A., & Gillam, S. (1998). Needs assessment: From theory to practice. British Medical Journal, 316 , 1448–1452.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stevens, A., & Rafferty, J. (1994, 1997). Health care needs assessment: The epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews . Vol. 1 and 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Stevens, A. J., & Rafferty, J. (1997). Health care needs assessment . Oxford: Radcliffe.

Stevens, A., Raftery, J., Mant, J., & Simpson, S. (2004). Health care needs assessment: The epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews (Vol. 1 and 2). Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Williams, R., & Wright, J. (1998). Epidemiological issues in health needs assessment. British Medical Journal, 316 , 1379–1382.

Wright, J. (2001). Assessing health needs. In D. Pencheon (Ed.), Oxford handbook of public health practice . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Recommended Reading

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Health and Human Development, University of East London, Water Lane, Stratford, UK

Patrick Tobi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Patrick Tobi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Bedfordshire, Luton, United Kingdom

Krishna Regmi

Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Tobi, P. (2016). Health Needs Assessment. In: Regmi, K., Gee, I. (eds) Public Health Intelligence. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28326-5_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28326-5_9

Published : 27 April 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-28324-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-28326-5

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Parenting, childcare and children's services

- Children's health and welfare

- Children's health

- Supporting public health: children, young people and families

- Public Health England

Population health needs assessment: a guide for 0 to 19 health visiting and school nursing services

Updated 19 May 2021

Applies to England

© Crown copyright 2021

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/commissioning-of-public-health-services-for-children/population-health-needs-assessment-a-guide-for-0-to-19-health-visiting-and-school-nursing-services

This guidance has been developed for health visitors, school nurses and their teams, though it may also be of use to other public health nurses. It aims to support them in their role assessing and prioritising local population health needs. Population health needs assessment is an element of the wider cycle to plan and deliver services at community and population level. It is the basis from which to continue planning, implementation, evaluation and dissemination phases to prioritise and deliver services to improve health and wellbeing outcomes.

Health visitors and school nurses have a substantial role in leading and coordinating delivery of public health interventions to address individual, community and population needs to improve health and wellbeing outcomes and reduce inequalities.

The focus is the population of children and young people that the health visitor and school nurse have responsibility for in a local community rather than assessment tools for individual children. A population may be a geographical area, school community, a specific group of children or young people, for example looked after children, young carers, or children who are asylum seekers or refugees.

It provides a framework for assessment, suggesting a range of practical steps to develop a profile of the health needs of the caseload or community that the health visitor and school nurse may be working with.

There are tools available to support health visitors and school nurses to deliver and evaluate, including the school nurse evaluation toolkit . The intention is to provide a simple approach to identifying and prioritising population health needs suggested through the commissioning for outcomes framework.

Improving health and wellbeing

A community-centred or place-based approach offers new opportunities to improve health and wellbeing outcomes, reduce health inequalities and develop local solutions that use all the assets and resources of an area. By integrating services, and building resilience in communities, individuals can take control of their health and wellbeing and have more influence on the factors that underpin good health.

This is illustrated through All Our Health , which demonstrates how improving outcomes is everyone’s business, working across settings such as community centres, green spaces and the workplace. Health visitors and school nurses are well placed to support families and communities to engage in this approach.

They have responsibility to lead, coordinate and provide services to the 0 to 19 years population. The High Impact Areas are those where the biggest difference can be made to children and young people’s health. This agenda is wide-ranging and public health challenges are increasing, health visitors and school nurses, with commissioners , make decisions about priorities and meeting local needs.

Health needs assessment is a way for health visitors and school nurses to gain a more in depth understanding of their communities and the needs that exist, enabling effective planning, prioritisation, development and delivery of services to improve outcomes for the population.

What is health needs assessment?

Health needs assessment is a systematic approach to understanding the needs of a population. The health needs assessment can be used as part of the commissioning process so that the most effective support for those in the greatest need can be planned and delivered. Responding to a health needs assessment provides an opportunity to improve outcomes where a population may be a group with a specific health need, school, cluster of schools, or a geographical community.

It is a holistic assessment considering social, economic, cultural and behavioural factors that influence health. In addition to readily available public health data, for example Child Health Profiles , a participatory approach should be adopted. It is important that the health visitor and school nurse recognise that there are different types of need, that some needs may be hidden and to make use of different perspectives.

Understanding the community, and the needs that exist, enables health visitors and school nurses to plan work to meet those needs, prioritise areas for service development, and determine any associated professional development required. Additionally, health needs assessment will enable teams and commissioners to work more closely together to ensure appropriate delivery. Health needs assessment should not be a one-off process but a continuous cycle to review the issues facing a population, leading to agreed priorities to improve health and reduce inequalities.

Planning for health needs assessment

Prior to starting the health needs assessment, it is important to have a clear understanding of the scope of the assessment. It is important to define the following:

- aims and objectives for the assessment – defining purpose and intended outcomes

- a target population to be assessed

- the data and information required

- a timeline for the health needs assessment – when, what, how and who. For example, for a health needs assessment of a school population, consider the school calendar for exam and revision periods

- potential challenges and how to manage them

- stakeholders who need to be involved, which may involve members of the health visiting team, school nurse team, key partners for example early years, schools, local authorities, voluntary, community and social enterprise ( VCSE ) sector

- resources required for example including IT equipment, room or space

- the strengths, limitations and opportunities of the health needs assessment

Other points to consider include:

- being clear on the intended outcome

- local or national priorities and issues of concern

- expectations of completing a population health needs assessment

- what is achievable within the resources available

- the boundaries and limitations of the health needs assessment

Stages of health needs assessment

There are 3 stages in health needs assessment:

- identifying need

- identifying assets

- determining priorities

Identifying health needs

The first stage of the health needs assessment involves gathering information and data. These sources will provide a breadth of perspectives on health and needs necessary for holistic assessment. The different sources of information help to define what influences the health needs as well as how many people are affected. When involving the children, young people and other key stakeholders, they will need to know why you are asking them to be involved, and to receive feedback on the results and outcome of the health needs assessment.

There is a wealth of quantitative data available to health visitors and school nurses about the health of the local population, which can be found in Child Health Profiles , that can be narrowed to the local area and compared to regional and national values.

Some example indicators are:

- children in poverty (under 16s)

- breast feeding

- immunisation uptake

- maternal mental health

- dental extractions

- family homelessness

- childhood obesity

- admission episodes for alcohol-specific conditions (under 18s)

- hospital admissions for asthma (under 19 years)

When the existing public health data is summarised in the health needs assessment report, consider the size and the severity of the issue, and how they relate to the High Impact Areas .

Every local authority publishes the latest statistics about the key issues affecting the health and wellbeing of their residents, including children and young people. The information, accessed through the local authority website, will include the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA), ward profiles, the annual public health report or local authority school health profile.

Presentation in a spine chart format allows for easy comparison to England or regional benchmarks. This information can be accessed via the Public Health Outcomes Framework , the Overview of Child Health and Mortality Rankings web pages. Much of this information, which can be viewed by life course stage (for example school age children) or by theme (for example children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing). The findings should be summarised in a health needs assessment report.

Health visitor and school nurse knowledge and experience

Knowledge and experience of a locality are also an important data source. Health vistor and school nursing teams have rich knowledge and understanding about the communities that they work in and their experiences working with children and young people. This includes what is important to communities and issues affecting service provision and access.

Issues to consider include:

- any underlying local health and wellbeing issues

- current child health and school profiles

- any continually highlighted issues and the support evidence for them

- the top 5 health and wellbeing concerns and impact on local population

- whether these issues can be influenced

- the factors affecting health locally (positively or negatively)

- services that are currently being provided and how accessible they are

- how can children, young people and families be reached

Children, young people, carer and family views

It’s important to understand the experiences of the population themselves. Views and ideas about their health and influencing factors such as lifestyles and experiences of services may differ to those of professionals and other stakeholders and are a vital component of health needs assessment.

Consideration should be given to how to include the views of people who may be underserved and whose voices are often not heard. These groups may include looked after children, young carers, families from black and minority ethnic communities, families of asylum seekers, and lone parents. In addition, there are individuals or groups (for example early years, maternity voices, school council, year group, class of pupils, existing service users, and youth clubs and local authority youth councils) who may contribute to the heath needs assessment and should be identified.

There are a variety of methods for involvement. Plans should consider the time available and the skills needed by staff for some methods. The activity chosen will depend on the group, for example, the age of the children. Through these activities, it’s possible to work with stakeholders to explore local understanding of health issues, the issues that are important to the population, the impact and changeability of these issues, and the quality of services currently delivered. The results should also be summarised in the health needs assessment report.

Methods for population involvement

Informal discussion group (focus group).

- Optimum focus group size is 8 to 12 participants

- Outline questions should be devised in advance

- Facilitator introduces topics for discussion

- Findings should be audio recorded and transcribed, or notes taken (preferably by another facilitator)

- A variety of groups may be needed for a wide range of views

Individual interview (semi-structured)

- Findings may be audio recorded and transcribed, or notes taken

Questionnaire

- Questionnaire can be paper-based or online

- An existing questionnaire should be used or adapted where available, for example WHO Global School-based Student Health Survey and Health Behaviour of School aged Children

- If a new questionnaire or survey is developed, this should be piloted first

Talking wall

- Interactive group discussion with individuals recording their comments

- Flip chart displayed on wall with topic headings; individuals add post-it note with their comments

- Online recording methods are available (for example Mentimeter )

- Suggestion boxes, You’re Welcome criteria , NHS Friends and Family test , complaints or compliments and local service audits

- Mentimeter : a free interactive voting tool, which can display real-time responses including text comments

Other stakeholders

It’s important to gather further intelligence on population needs from other professionals working locally who have knowledge of the area. Pooling this knowledge can support the identification of health and social problems that affect the population group and provide information about uptake of services.

This may include teachers, school governors, education welfare officers, commissioners, early year’s practitioners, community leaders, youth groups, the police, community groups, social workers or elected members. Commissioners are a strategic stakeholder and will be a key partner once the health needs are prioritised and the action plan is being prepared for the target population, such as the school or community. Following the school nurse health needs assessment, the commissioners may consider making changes to the services commissioned locally. The same methods for involvement used with the population can be used to engage stakeholders. The findings should be summarised in the health needs assessment report.

Apart from ensuring that the health needs assessment captures information from different perspectives, engaging others in the process helps to strengthen networks and, during the process, solutions to some of the issues may be suggested by others. It is important to make a note of these.

Identifying assets

Identifying assets is an important part of the health needs assessment to ensure the views, perceptions and experiences of children, young people and local communities are captured. Other stakeholders will also have perspectives, for example residents’ or voluntary sector partners’ views on the strengths and assets in a locality. This will support the development of solutions to meet the needs of the population.

To identify what enablers of health exist, consider:

- the strengths and resources locally

- services available, for example, mental health services and sexual health services

- any early years opportunities

- any school-based opportunities

- the skills and expertise in the health visiting and school nursing service

- who else is available to support health needs, for example, community leaders

- local community groups, for example, youth groups, voluntary, community and social enterprises

- community facilities, for example, sports, leisure facilities and community pharmacies

Determining priorities

The different needs and findings should be determined and defined. This could include linking them to poor health indicators locally and to local policies . The identified needs can then be compared using an agreed process, where possible involving stakeholders, parents, children and young people, to determine 2 to 3 priorities.

The health visitor and school nurse should consider the following factors, whichever method is used to prioritise need:

- impact – the severity and size of the issue

- changeability – the realistic chance of achieving change

- acceptability – acceptable solutions available

- feasibility – resource implications of solutions are feasible

See Taxonomy of social need (Bradshaw 1972) .

Several simple methods can enable health visitors and school nurses to prioritise the most important health needs and are presented below.

If each method used produces a different order of priorities, it is important to give a rationale in the final health needs assessment report for the final priority list of needs. For example, this could include a list that supports a key local public health priority or national policy may be more successful in attracting funding from the local commissioner. Engaging commissioners in considerations will support the prioritisation of joint needs.

Forced ranking

In this simple method, each person or group of people rank every health need on a scale of importance. Overall ranking scores for each need are combined to identify the order of priority. This approach produces a priority list based on the experience of the individuals taking part.

Instructions for the process are as follows:

- if 5 health needs are identified, the most important need is allocated a ‘1’, the second most important is ranked ‘2’ and subsequently follows on to the least important need, which will be ‘5’

- when the ranking process has been repeated by each person or group, the ranking scores are added together to provide a total score for each health need. The lowest score has the highest priority and follows on until all needs have been ranked

An example:

This example indicates that mental health is the highest priority need as it has received the lowest score overall, followed by obesity and then alcohol.

Strategy grid

Prioritising needs using the strategy grid method places the focus on addressing needs within the resources available. Strategy grids provide a way of thinking about problems so that the greatest results can be achieved with limited resources.

Instructions for the process are as follows.

- Identify 2 criteria to prioritise need, which should be relevant to health visiting or school nursing. The example below uses impact and feasibility, but other examples may be ‘need and impact’, ‘importance and changeability’ or ‘impact and cost’

- Set up a grid with 4 boxes and allocate one criteria to each axis. Create arrows on the axes to indicate ‘high’ or ‘low’, as shown in the example below.

- Place needs in the appropriate box based on the criteria. The needs have been prioritised as:

- High impact and High feasibility – these are the highest priority needs and require resources and input to address and improve health outcomes

- Low impact and High feasibility – politically important, interventions for these needs can be redesigned to reduce investment and maintain outcomes

- High impact and Low feasibility – these needs often require long-term investment and creative solutions. Too many can be overwhelming. These needs may require breaking down into smaller component parts.

- Low impact and Low feasibility – these are low priority needs. Interventions provide minimal return on investment, so resources should be reallocated to high priority needs.

Priority grid

This is another grid method that scores health needs against a series of locally identified questions.

Enter the issues into the grid and allocate a mark based on the scoring mechanism identified. Scores are totalled to identify 2 to 3 priority needs to be addressed. The remaining needs can be tackled by others or managed later.

Download an example of a priority grid.

Nominal group technique

The nominal group technique supports the involvement of stakeholders by prioritising a wide number of needs in a short time. It encourages debate and quick decisions. It is a democratic process where stakeholders have an equal say regardless of seniority or background. This can be done with everyone together in a room at the same time, or the first 2 stages can be completed remotely.

The first task is to establish a group structure. This part of the process involves gathering a group of 8 to 10 people to participate including health visitors or school nurses, children or young people, or others. The group objective is to prioritise health needs.

Once the group is established, the health visitor or school nurse provides identified health needs and allows the participants to silently record their top 5 potential priorities and rationale for selection. A group meeting follows to share and record all potential priority needs.

The recorded list is then simplified by grouping similar needs or priorities together. The moderator reads out the priorities and participants feedback on how to group them together. Any suggestions that are unclear can be clarified. The moderator then facilitates a group discussion about the potential priorities, the importance of each and interventions.

Participants can then silently and anonymously rank each listed health need on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is the highest priority and 5 is the lowest. The moderator collects the results and calculates the total score for each health need. Those with no score are rejected. Of the remainder, the need with the lowest score is the highest priority need, and that with the highest score is the lowest priority need, with the rest on a sliding scale in between. If the list results in tied scores or the results need to be narrowed, the process can be repeated.