- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 25 January 2012

Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models

- Kristine Sørensen 1 ,

- Stephan Van den Broucke 2 ,

- James Fullam 3 ,

- Gerardine Doyle 3 ,

- Jürgen Pelikan 4 ,

- Zofia Slonska 5 ,

- Helmut Brand 1 &

(HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European

BMC Public Health volume 12 , Article number: 80 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

361k Accesses

2940 Citations

142 Altmetric

Metrics details

Health literacy concerns the knowledge and competences of persons to meet the complex demands of health in modern society. Although its importance is increasingly recognised, there is no consensus about the definition of health literacy or about its conceptual dimensions, which limits the possibilities for measurement and comparison. The aim of the study is to review definitions and models on health literacy to develop an integrated definition and conceptual model capturing the most comprehensive evidence-based dimensions of health literacy.

A systematic literature review was performed to identify definitions and conceptual frameworks of health literacy. A content analysis of the definitions and conceptual frameworks was carried out to identify the central dimensions of health literacy and develop an integrated model.

The review resulted in 17 definitions of health literacy and 12 conceptual models. Based on the content analysis, an integrative conceptual model was developed containing 12 dimensions referring to the knowledge, motivation and competencies of accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health-related information within the healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion setting, respectively.

Conclusions

Based upon this review, a model is proposed integrating medical and public health views of health literacy. The model can serve as a basis for developing health literacy enhancing interventions and provide a conceptual basis for the development and validation of measurement tools, capturing the different dimensions of health literacy within the healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion settings.

Peer Review reports

Health literacy is a term introduced in the 1970s [ 1 ] and of increasing importance in public health and healthcare. It is concerned with the capacities of people to meet the complex demands of health in a modern society [ 2 ]. Health literate means placing one's own health and that of one's family and community into context, understanding which factors are influencing it, and knowing how to address them. An individual with an adequate level of health literacy has the ability to take responsibility for one's own health as well as one's family health and community health [ 3 ].

It is important to distinguish health literacy from literacy in general. According to the United Nation Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) during its history in English, the word 'literate' mostly meant to be 'familiar with literature' or in general terms 'well educated, learned'. While maintaining its broader meaning of being knowledgeable or educated in a particular area, during the late nineteenth century it has also come to refer to the abilities to read and write text. In recent years four understandings of literacy have appeared from the debate of the notion: 1) Literacy as an autonomous set of skills; 2) literacy as applied, practiced and situated; 3) literacy as a learning process; and 4) literacy as text. The focus is furthermore broadening so that literacy is not only referring to individual transformation, but also to contextual and societal transformation in terms of linking health literacy to economic growth and socio-cultural and political change [ 4 ].

The same development can be traced in the realm of health literacy. For some time most emphasis was given to health literacy as the ability to handle words and numbers in a medical context, and in recent years the concept is broadening to also understanding health literacy as involving the simultaneous use of a more complex and interconnected set of abilities, such as reading and acting upon written health information, communicating needs to health professionals, and understanding health instructions [ 5 ]. American studies in the 1990s linked literacy to health, showing an association between low literacy and decreased medication adherence, knowledge of disease and self-care management skills [ 6 ]. The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), which measured the English literacy of American adults (people age 16 and older) included questions related to health, and revealed the consequences of limited literacy on health and healthcare [ 7 ].

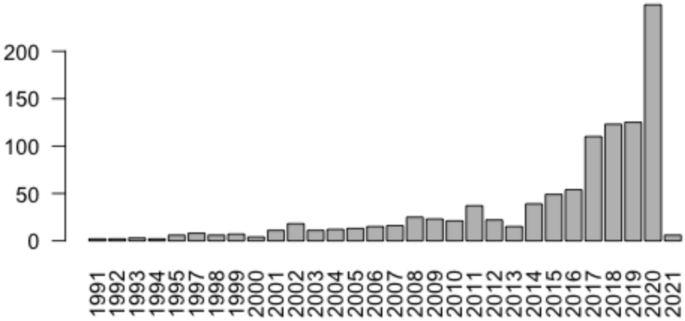

A report from the Institute of Medicine indicates that nearly half of the American adult population may have difficulties in acting on health information [ 8 ]. This finding has been referred to as the "health literacy epidemic" [ 9 ]. In response, measures have been taken to ensure better health communication through establishing health literacy guidelines [ 10 ], and a trans-disciplinary approach has been encouraged to improve health literacy [ 11 ]. To support this approach, the American Medical Association recommends four areas for research: health literacy screening; improving communication with low-literacy patients; costs and outcomes of poor health literacy; and causal pathways of how poor health literacy influences health [ 12 , 13 ]. The research literature on health literacy has expanded exponentially, with nearly 5,000 PubMed-listed publications to date (Primo November 2011), the majority of which have been published since 2005 [ 5 , 14 ] and is evident that health literacy is being explored within different disciplines and with different approaches, e.g. looking at the role of health educators in promoting health literacy [ 15 ]; public health literacy for lawyers [ 16 ], health communication [ 17 ], the prevalence of limited health literacy [ 18 ], and health literacy as an empowerment tool for low-income mothers [ 19 ].

While until recently the interest in health literacy was mainly concentrated in the United States and Canada, it has become more internationalized over the past decade [ 20 ]. Research on health literacy has taken place in e.g. Australia [ 21 , 22 ], Korea [ 23 ], Japan [ 24 ], the UK [ 25 ], the Netherlands [ 26 ], and Switzerland [ 27 ]. Although the EU produced less than a third of the global research on health literacy between 1991 and 2005 [ 28 , 29 ], the importance of the issue is increasingly recognized in European health policies. As a case in point, health literacy is explicitly mentioned as an area of priority action in the European Commission's Health Strategy 2008-2013 [ 30 ]. It is linked to the core value of citizen empowerment, and the priority actions proposed by the European Commission include the promotion of health literacy programs for different age groups.

However, with the proliferation of health literacy research and policy measures, it becomes clear that there is no unanimously accepted definition of the concept. Moreover, the constituent dimensions of health literacy remain disputed, and attempts to operationalize the concept vary widely in scope, method and quality. As a result, it is very difficult to compare findings with regard to health literacy emerging from research in different countries.

The current article aims to address this issue by offering a systematic review of existing definitions and concepts of health literacy as reported in the international literature, by identifying the central health literacy dimensions, the target group as well as antecedents and consequences if explained. in order to develop an integrated definition and conceptual model capturing the most comprehensive evidence-based dimensions of health literacy.

A systematic review in Medline, Pubmed and Web of Science was performed by two independent research teams in autumn 2009 and spring 2010 and the results compared and combined to obtain information regarding two research questions: (1) How is health literacy defined? and (2) How can health literacy be conceptualized? To retrieve studies, 17 keywords (definition, model, concept, dimension, framework, conceptual framework, theory, analysis, qualitative, quantitative, competence, skill, "public health", communication, information, functional, critical) were combined (using the Boolean operator and ) with the search terms "health literacy", "health competence", and health competence (without quotes). Combinations of the keywords with health literacy (without quotes) produced a list of studies that was too wide for the purpose of this study, and therefore not used for the review. From the resulting list, studies were selected for inclusion in the review on the basis of their abstracts. Eligible studies were included which met the following inclusion criteria: (1) written in English; (2) concerned with health literacy in a developed country; and (3) offering relevant content with regard to the definition or conceptualization of health literacy, or a combination of these issues.

The eligible literature was scanned for definitions, and a content analysis was performed in three steps: Firstly, the definitions were coded and condensed by two research teams working independently. Secondly the analysis was discussed with a panel of health experts from the European Health Literacy Consortium. In a third step, the feedback was elaborated by the original research team and integrated in a final analysis yielding a condensed 'all-inclusive' definition of health literacy capturing the different meanings and dimensions presented in the literature. In addition, an overview of all models from the eligible literature was conducted, the models were compared according to dimensions, target groups and antecedents as well as consequences if explained, and as a result a new conceptual model was drafted capturing the most comprehensive core dimensions of health literacy identified as well as its antecedents and consequences.

The combination of the key words with the three search terms resulted in the initial identification of 170 publications. Additional publications were found by reference tracking and included in the review. Based on the application of the inclusion criteria to the abstracts, 19 publications were retrieved which explicitly dealt with the definition of health literacy, and 12 with conceptual frameworks of health literacy.

Definitions of health literacy

From the 19 publications focusing specifically on definitions of health literacy 17 explicit definitions could be derived (Table 1 ). Of these definitions, the ones by the American Medical Association [ 12 ], the Institute of Medicine [ 8 ] and WHO [ 31 ] are cited most frequently in the eligible literature. A shared characteristic of these definitions is their focus on individual skills to obtain, process and understand health information and services necessary to make appropriate health decisions. However, recent discussions on the role of health literacy highlight the importance of moving beyond an individual focus, and of considering health literacy as an interaction between the demands of health systems and the skills of individuals. In fact the Institute of Medicine report already alluded that "health literacy is a shared function of social and individual factors, which emerges from the interaction of the skills of individuals and the demands of social systems" [ 8 ]. More recently, Kwan [ 32 ] and Pleasant [ 33 ] underscored the importance of skills and abilities on the part of all parties involved in communication and decisions about health, including patients, providers, health educators, and lay people. This broader view is presented in the definition proposed by Zarcadoolas, Pleasant and Greer [ 34 ], who state that a health literate person is able to apply health concepts and information to novel situations, and to participate in ongoing public and private dialogues about health, medicine, scientific knowledge, and cultural beliefs. Freedman and her collegues [ 35 ] argue that the medical perspective on factors influencing people's health should be shifted towards a societal level, and that a distinction must be made between public and individual health literacy. Public health literacy can be found when the conceptual foundations of health literacy are in place in a group or community.

The content analysis on the definitions yielded six clusters representing: (1) competence, skills, abilities; (2) actions; (3) information and resources; (4) objective; (5) context; and (6) time as outlined in Table 2 . Accordingly each cluster was carefully examined, discussed and condensed by the research team and the resulting chosen terms and notions were combined to yield a new 'all inclusive' comprehensive definition capturing the essence of the 17 definitions identified in the literature:

Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people's knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course .

This definition encompasses the public health perspective and can easily be specified to accommodate an individual approach by substituting the three domains of health "healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion" with "being ill, being at risk and staying healthy".

Concepts of health literacy

Table 3 lists the publications which provide a conceptual model of health literacy. From this overview, two issues become apparent. Firstly, health literacy is a multidimensional concept and consists of different components. Secondly, most conceptual models not only consider the key components of health literacy, but also identify the individual and system-level factors that influence a person's level of health literacy, as well as the pathways that link health literacy to health outcomes.

Dimensions of health literacy

The distinction between medical and public health literacy [ 35 ] is reflected in the identification of different dimensions. Within the definition of health literacy as individual capacities, the Institute of Medicine [ 8 ] consider cultural and conceptual knowledge, listening, speaking, arithmetical, writing, and reading skills as the main components of health literacy. Speros [ 48 ] also identifies reading and numeracy skills as the defining attributes, but adds comprehension, the capacity to use health information in decision making, and successful functioning in the role of healthcare consumer as dimensions. Baker [ 49 ] divides health literacy into health related print literacy and health related oral literacy, while Paashe-Orlow and Wolf [ 40 ] distinguish between listening, verbal fluency, memory span and navigation. Lee et al. [ 47 ] identify four interrelated factors: (1) disease and self-care knowledge; (2) health risk behavior; (3) preventive care and physician visits; and (4) compliance with medication. While these defining elements of health literacy vary considerably they all concern cognitive capabilities, skills and behaviors which reflect an individual's capacity to function in the role of a patient within the healthcare system.

Proponents of the population health literacy view, on the other hand, extend the concept to include dimensions which go beyond individual competences and the medical context. The prototypical model is that of Nutbeam [ 36 ], which distinguishes between three typologies of health literacy: (1) Functional health literacy refers to the basic skills in reading and writing that are necessary to function effectively in everyday situations, broadly comparable with the content of "medical" health literacy referred to above; (2) Interactive health literacy refers to more advanced cognitive and literacy skills which, together with social skills, can be used to actively participate in everyday situations, extract information and derive meaning from different forms of communication, and apply this to changing circumstance; and (3) Critical health literacy refers to more advanced cognitive skills which, together with social skills, can be applied to critically analyze information and use this to exert greater control over life events and situations. The different typologies represent levels of knowledge and skills that progressively support greater autonomy and personal empowerment in health related decision-making, as well as engagement with a wider range of health knowledge that extends from personal health management to the social determinants of health [ 52 ]. Manganello [ 50 ] adds media literacy as the ability to critically evaluate media messages. Zarcadoolas et al. [ 38 ] distinguish between fundamental literacy (skills and strategies involved in reading, speaking, writing and interpreting numbers); science literacy (the levels of competence with science and technology); civic literacy (abilities that enable citizens to become aware of public issues and become involved in the decision-making process); and cultural literacy (the ability to recognize and use collective beliefs, customs, world-view and social identity in order to interpret and act on health information). In a similar vein, Freedman et al. [ 35 ] identify three dimensions of public health literacy, each of which involves corresponding competences: (1) Conceptual foundations includes the basic knowledge and information needed to understand and take action on public health concerns; individuals and groups should be able to discuss core public health concepts, public health constructs and ecologic perspectives. (2) Critical skills relates to the skills necessary to obtain, process, evaluate, and act upon information that is needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community; an individual or group should be able to obtain, evaluate, and utilize public health information, identify public health aspects of personal and community concerns, and access who is naming and framing public health problems and solutions. (3) Civic orientation includes the skills and resources necessary to address health concerns through civic engagement; an individual or group should be able to articulate the uneven distribution of burdens and benefits of the society, evaluate who benefits and who is harmed by public health efforts, communicate current public health problems, and address public health problems through civic action, leadership, and dialogue. Mancuso [ 43 ] emphasizes that health literacy is a process that evolves over a person's lifetime and identify the attributes of health literacy to be capacity, comprehension and communication. (1) The Capacity skills related to health literacy include gathering, analyzing, and evaluating health information for credibility and quality, working together, managing resources, seeking guidance and support, developing and expressing a sense of self, creating and pursuing a vision and goals, and keeping pace with change. Oral language skills are also considered essential. Social skills and credentials such as reading, listening, analytical, decision-making, and numerical abilities are important as well to advocate for oneself, to act on health information, and to negotiate and navigate within the health-care system. (2) Comprehension is a complex process based on the effective interaction of logic, language, and experience and is crucial to the accurate interpretation of a myriad of information that is provided to the modern patient, such as discharge instructions, consent forms, patient education materials, and medication directions. (3) Communication is how thoughts, messages or information are exchanged through speech, signals, writing or behavior. Communication involves inputs, decoding, encoding output, and feedback. Essential communication skills are reading with understanding, conveying ideas in writing, speaking so others can understand, listening actively, and observing critically.

In conclusion, the range of factors that are considered as key components of health literacy is extensive, and there is a wide variation between conceptual models. However, this diversity of views can to a large extent be reduced to two dimensions, notably the core qualities of health literacy (e.g., basic or functional, interactive, and critical health literacy), and its scope and area of application (e.g., as a patient in healthcare, as a consumer at the market, as a citizen in the political arena, or as a member of the audience in relation to the media).

Antecedents and consequences of health literacy

Apart from the dimensions of health literacy, the conceptual models summarized in Table 3 also give the main antecedents and consequences of health literacy outlined in the literature.

For the antecedents , most authors refer to demographic, psychosocial, and cultural factors, as well as to more proximal factors such as general literacy, individual characteristics and prior experience with illness and the healthcare system. Among the demographic and social factors which impact on health literacy one notes socioeconomic status, occupation, employment, income, social support, culture and language [ 40 ], environmental and political forces [ 35 ], and media use [ 50 ]. In addition, peer and parental influences may impact on the health literacy of adolescents. In terms of personal characteristics, health literacy is predicted by age, race, gender and cultural background [ 50 ]; as well as by competences such as vision, hearing, verbal ability, memory and reasoning [ 40 ], physical abilities and social skills [ 50 ], and meta-cognitive skills associated with reading, comprehension, and numeracy [ 4 , 48 , 50 ]. The latter refers to the level of overall literacy, defined as the capacity to use printed and written information to function in society, achieve one's goals, and develop one's knowledge and potential. Finally, Nutbeam [ 36 ] points out that health literacy is also a result of health promotion actions such as education, social mobilization and advocacy.

In terms of the consequences , a number of researchers pointed out that health literacy leads to improved self-reported health status, lower healthcare costs, increased health knowledge, shorter hospitalization, and less frequent use of healthcare services [ 43 , 48 , 50 , 53 ]. According to Baker [ 49 ], these better health outcomes are caused by the acquisition of new knowledge, more positive attitudes, greater self-efficacy, and positive health behaviors associated with higher health literacy. Paashe-Orlow and Wolf [ 40 ] posit that health literacy influences three main factors which in turn have an impact on health outcomes: (1) navigation skills, self-efficacy and perceived barriers influence the access and utilization of healthcare; (2) knowledge, beliefs and participation in decision-making influence patient/provider interactions; and (3) motivation, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and knowledge and skills influence self care. The relationship of health literacy to health outcomes according to these authors must be conceived as a step function with a threshold effect, rather than in a simple linear fashion. People generally exist within a web of social relationships; and below a certain level of function, much of the day-to-day detail of chronic disease management often needs to be facilitated by others. While the interaction between health literacy and social support is likely to have complicated and subtle implications, the health impact of social effects has not been fully elucidated in the context of health literacy [ 54 ].

Nutbeam [ 36 ] distinguishes between individual and community or social benefits of health literacy. In terms of individual benefits, functional health literacy leads to an improved knowledge of risks and health services, and compliance with prescribed actions; interactive health literacy to an improved capacity to act independently, an improved motivation and more self-confidence; and critical health literacy to improved individual resilience to social and economic adversity. In terms of community and social benefits, functional health literacy increases the participation in population health programs; interactive health literacy enhances the capacity to influence social norms and interact with social groups; and critical health literacy improves community empowerment and enhances the capacity to act on social and economic determinants of health. Nutbeam's conceptual framework has been applied in case studies focusing on topics of diarrhea [ 55 ], self-management in diabetes [ 56 ] and health promoting schools [ 57 ].

Ratzan [ 58 ] links health literacy in the community to the concept of social capital, arguing that health literate people live longer and have stronger incentives to invest in developing their own and their children's knowledge and skills. Healthier populations tend to have higher labor market productivity contributing to, rather than withdrawing from, pension schemes. Similarly, healthier people use the health system less, and coupled with education and cognitive function, appropriately demand fewer health services.

An integrated conceptual model of health literacy

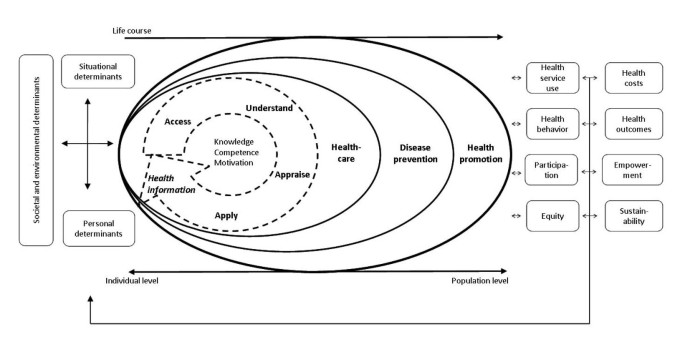

Whereas a number of conceptual models of health literacy have been presented in the literature, none of these can be regarded as sufficiently comprehensive to line up with the evolving health literacy definitions and with the competencies they imply [ 59 ]. This is probably due to the fact that attempts to conceptualize health literacy have thus far failed to integrate the existing knowledge encompassing different perspectives on health literacy. Firstly, most of the existing conceptual models are not sufficiently grounded in theory in terms of the notions and concepts included. Secondly, very few models have integrated the components included in "medical" and "public health" literacy models. The only models which explicitly try to bridge the difference between both views are Nutbeam's [ 36 ] and Manganello's [ 50 ], whose dimension of functional literacy corresponds with the cognitive skills of medical health literacy. Thirdly, while acknowledging that health literacy entails different dimensions, the majority of the existing models are rather static and do not explicitly account for the fact that health literacy is also a process, which involves the consecutive steps of accessing, understanding, processing and communicating information. Fourthly, while most conceptual models identify the factors that influence health literacy and mention its impact on health service use, health costs and health outcomes, the pathways linking health literacy to its antecedents and consequences are not very clear. Researchers could link conceptual models of health literacy more explicitly to established health promotion theories and models [ 59 ]. Finally, very few conceptual models of health literacy have been empirically validated. To address these shortcomings, we propose an integrated model of health literacy which captures the main dimensions of the existing conceptual models reviewed above (Figure 1 ).

Integrated model of health literacy--see separate file .

The model combines the qualities of a conceptual model outlining the main dimensions of health literacy (represented in the concentric oval shape in the middle of Figure 1 ), and of a logical model showing the proximal and distal factors which impact on health literacy, as well as the pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes.

The core of the model shows the competencies related to the process of accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health-related information. According to the 'all inclusive' definition this process requires four types of competencies: (1) Access refers to the ability to seek, find and obtain health information; (2) Understand refers to the ability to comprehend the health information that is accessed; (3) Appraise describes the ability to interpret, filter, judge and evaluate the health information that has been accessed; and (4) Apply refers to the ability to communicate and use the information to make a decision to maintain and improve health. Each of these competences represents a crucial dimension of health literacy, requires specific cognitive qualities and depends on the quality of the information provided [ 60 ]: obtaining and accessing health information depends on understanding, timing and trustworthiness; understanding the information depends on expectations, perceived utility, individualization of outcomes, and interpretation of causalities; processing and appraisal of the information depends on the complexity, jargon and partial understandings of the information; and effective communication depends on comprehension. The competences also incorporate the qualities of functional, interactive and critical health literacy as proposed by Nutbeam [ 36 ].

This process generates knowledge and skills which enable a person to navigate three domains of the health continuum: being ill or as a patient in the healthcare setting, as a person at risk of disease in the disease prevention system, and as a citizen in relation to the health promotion efforts in the community, the work place, the educational system, the political arena and the market place. Going through the steps of the health literacy process in each of these three domains equips people to take control over their health by applying their general literacy and numerical skills as well as their specific health literacy skills to acquire the necessary information, understanding this information, critically analyzing and appraising it, and acting independently to engage in actions overcoming personal, structural, social and economical barriers to health. As contextual demands change over time, and the capacity to navigate the health system depends on cognitive and psychosocial development as well as on previous and current experiences, the skills and competencies of health literacy develop during the life course and are linked to life long learning.

The frameworks associated with the three domains represent a progression from an individual towards a population perspective. As such, the model integrates the "medical" conceptualization of health literacy with the broader "public health" perspective. Placing greater emphasis on heath literacy outside of healthcare settings has the potential to impact on preventative health and reduce pressures on health systems.

The combination of the four dimensions referring to health information processing with the three levels of domains yields a matrix with 12 dimensions of health literacy as illustrated in Table 4 .

Four dimensions of health literacy in the domain of healthcare , i.e., the ability to access information on medical or clinical issues, to understand medical information, to interpret and evaluate medical information, and to make informed decisions on medical issues and comply with medical advice.

Four dimensions of health literacy in the domain of disease prevention , notably the ability to access information on risk factors for health, to understand information on risk factors and derive meaning, to interpret and evaluate information on risk factors, and to make informed decisions on risk factors for health.

Four dimensions in the domain of health promotion , notably the ability to regularly update oneself on determinants of health in the social and physical environment, to comprehend information on determinants of health in the social and physical environment and derive meaning, to interpret and evaluate information on determinants, of health in the social and physical environment, and the ability to make informed decisions on health determinants in the social and physical environment.

Health literacy is in our understanding regarded an asset for improving people's empowerment within the domains of healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion.

In addition to the components of health literacy proper, the model in Figure 1 also shows the main antecedents and consequences of health literacy. Among the factors which impact on health literacy, a distinction is made between more distal factors, including societal and environmental determinants (e.g., demographic situation, culture, language, political forces, societal systems), and proximal factors, which are more concerned with personal determinants (e.g., age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, education, occupation, employment, income, literacy) and situational determinants (e.g. social support, family and peer influences, media use and physical environment). Health literacy is strongly associated with educational attainment [ 50 ], as well as with overall literacy [ 34 , 38 , 39 ]. Fundamental literacy affects a wide range of cognitive, behavioral, and societal skills and abilities. It should be distinguished from other specific literacy, such as science literacy (i.e., the ability to comprehend technical complexity, understanding of common technology, and an understanding that scientific uncertainty is to be expected), cultural literacy (i.e., recognizing and using collective beliefs, customs, world-views, and social identity relationships) and civic literacy (i.e., knowledge about sources of information and about agendas and how to interpret them, enabling citizens to engage in dialogue and decision-making). According to Mancuso [ 43 ], an individual must have certain skills and abilities to obtain competence in health literacy, and identifies six dimensions that are considered as necessary antecedents of health literacy, namely operational, interactive, autonomous, informational, contextual, and cultural competence.

Health literacy in turn influences health behavior and the use of health services, and thereby will also impact on health outcomes and on the health costs in society. At an individual level, ineffective communication due to poor health literacy will result in errors, poor quality, and risks to patient safety of the healthcare services [ 61 ]. At a population level, health literate persons are able to participate in the ongoing public and private dialogues about health, medicine, scientific knowledge and cultural beliefs. Thus, the benefits of health literacy impact the full range of life's activities--home, work, society and culture [ 34 , 38 , 39 ]. Advancing health literacy will progressively allow for greater autonomy and personal empowerment, and the process of health literacy can be seen as a part of an individual's development towards improved quality of life. In the population, it may also lead to more equity and sustainability of changes in public health. Consequently, low health literacy can be addressed by educating persons to become more resourceful (i.e., increasing their personal health literacy), and by making the task or situation less demanding, (i.e., improving the "readability of the system").

In this article we have we have presented a working definition of health literacy which represents the essence of the definitions of this concept as given in the literature. Furthermore a new conceptual model has been developed as a result of the review of existing health literacy concepts. While the literature indicates that health literacy refers to the competences of people to meet the complex demands of health in modern society [ 2 , 3 , 62 ] the exact nature of these competences is still debated. One perspective is that they refer to a series of individual cognitive skills and abilities applied in a medical context; the other perspective sees a broader range of competencies applied in the social realm. The first is referred to as "medical health literacy" [ 5 ], "patient health literacy" [ 14 ], or "clinical health literacy" [ 63 ]; the second as "public health literacy" [ 35 ]. Nutbeam [ 52 ] refers to the opposing medical and public health views on health literacy as respectively a "clinical risk", and a "personal asset" approach, and points out that they are rooted in the different traditions of clinical care, and adult learning and health promotion, respectively. As both perspectives are important and useful to enable a better understanding of health communication processes in clinical and community settings, any definition of health literacy needs to integrate both views. The proposed 'all inclusive' definition is adaptable and includes the public health perspective as well as the individual perspective.

While originating from the study of the reading and numerical skills that are necessary to function adequately in the healthcare environment, the concept of health literacy has expanded in meaning to include information-seeking, decision-making, problem-solving, critical thinking, and communication, along with a multitude of social, personal, and cognitive skills that are imperative to function in the health-system [ 49 , 52 , 59 ]. It has now diffused into the realm of culture, context, and language [ 49 , 52 , 59 ]. Although some authors have argued that health literacy is merely "new wine in old bottles", and is basically the repackaging of concepts central to the ideological theory and practice of health promotion [ 64 ], enhancing health literacy is increasingly recognized as a public health goal and a determinant of health. As new health literacy frameworks have emerged to clarify the deeper meaning of health literacy, its contribution to health, and the social, environmental, and cultural factors that influence health literacy skills in a variety of populations, there is a need for an integration of diverging definitions, conceptual frameworks and models of health literacy.

The conceptual framework presented in this paper provides this integration in the form of a comprehensive model. Based on a systematic review of existing definitions and conceptualizations of health literacy, it combines the qualities of a conceptual model outlining the most comprehensive dimensions of health literacy, and of a logical model, showing the proximal and distal factors which impact on health literacy as well as the pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Specifically, the model identifies 12 dimensions of health literacy, referring to the competencies related to accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health information in the domains of healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion, respectively.

By integrating existing definitions and conceptualizations of health literacy into an encompassing model outlining the main dimensions of health literacy as well as its determinants and the pathways to health outcomes, this model has a heuristic value in its own right. More importantly, however, it can also support the practice of healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion by serving as a conceptual basis to develop health literacy enhancing interventions. Moreover, it can contribute to the empirical work on health literacy by serving as a basis for the development of measurement tools. As currently available tools to measure health literacy do not capture all aspects of the concept as discussed in the literature, there is a need to develop new tools to assess health literacy, reflecting health literacy definitions and accompanying conceptual models for public health. By following a concept validation approach, scales can be developed to assess the dimensions outlined in the conceptual model presented in this paper. This will not only produce a comprehensive measure of health literacy, reflecting the state of the art of the field and applicable for social research and in public health practice, but also serve to validate the conceptual model and thus contribute to the understanding of health literacy.

Simonds SK: Health education as social policy. Health Education Monograph. 1974, 2: 1-25.

Article Google Scholar

Kickbusch I, Maag D: Health Literacy. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Edited by: Kris H, Stella Q. 2008, Academic Press, 3: 204-211.

Chapter Google Scholar

Health and modernity. Edited by: McQueen D, KI Potvin L, Pelikan JM, Balbo L, Abel Th. 2007, Springer: The Role of Theory in Health Promotion

Google Scholar

UNESCO: Literacy for all. Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006. 2005, UNESCO Publishing

Peerson A, Saunders M: Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter?. Health Promot Int. 2009, 24 (3): 285-296. 10.1093/heapro/dap014.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Parker R: Health literacy: a challenge for American patients and their health care providers. Health Promot Int. 2000, 15 (4): 277-283. 10.1093/heapro/15.4.277.

Kutner M, Jin E, Paulsen C: The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). National Center for Education. 2006, Washington DC: U.S. Department of Education

Institute of Medicine: Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. 2004, Washington DC: The National Academies

Davis T, Wolf MS: Health literacy: implications for family medicine. Fam Med. 2004, 36 (8): 595-598.

PubMed Google Scholar

Health Literacy Innovations: The Health Literacy & Plain Language Resource Guide. Health Literacy Innovations; n.d

Lloyd LLJ, Ammary NJ, Epstein LG, Johnson R, Rhee K: A transdisciplinary approach to improve health literacy and reduce disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006, 7 (3): 331-335. 10.1177/1524839906289378.

Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs AMA: Health literacy: report of the council on scientific affairs. J Am Med Assoc. 1999, 281 (6): 552-557. 10.1001/jama.281.6.552.

McCray A: Promoting health literacy. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004, 12 (2): 152-163. 10.1197/jamia.M1687.

Ishikawa H, Yano E: Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect. 2008, 11 (2): 113-122. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00497.x.

Tappe MK, Galer-Unti RA: Health educators' role in promoting health literacy and advocacy for the 21 st century. J Sch Health. 2001, 71 (10): 477-482. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb07284.x.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Robbins A: Public health literacy for lawyers: teaching population-based legal analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2003, 111 (14): 744-745. 10.1289/ehp.111-a744.

Parker RM, Gazmararian JA: Health literacy: essential for health communication. J Health Commun. 2003, 8 (3): 116-118.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR: The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005, 20: 174-184.

Porr Caroline, Drummond Jane, Richter Solina: Health Literacy as an Empowerment Tool for Low-Income Mothers. Family & Community Health. 2006, 29 (4): 328-335.

Paasche-Orlow MK: Bridging the international divide for health literacy research. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 75: 293-294. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.001.

Barber MN, Staples M, Osborne RH, Clerehan R, Elder C, Buchbinder R: Up to a quarter of the Australian population may have suboptimal health literacy depending upon the measurement tool: results from a population-based survey. Health Promot Int. 2009, 24 (3): 252-261. 10.1093/heapro/dap022.

Adams RJ, Stocks NP, Wilson DH, Hill CL, Gravier S, Kickbusch I, Beilby JJ: Health literacy. A new concept for general practice?. Aust Fam Physician. 2009, 38 (3): 144-147.

Lee TW, Kang SJ, Lee HJ, Hyun SI: Testing health literacy skills in older Korean adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 75 (3): 302-307. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.002.

Ishikawa H, Nomura K, Sato M, Yano E: Developing a measure of communicative and critical health literacy: a pilot study of Japanese office workers. Health Promot Int. 2008, 23 (3): 269-274. 10.1093/heapro/dan017.

Ibrahim SY, Reid F, Shaw A, Rowlands G, Gomez GB, Chesnokov M, Ussher M: Validation of a health literacy screening tool (REALM) in a UK population with coronary heart disease. Journal of Public Health (Oxf). 2008, 30: 449-455. 10.1093/pubmed/fdn059.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Twickler TB, Hoogstraten E, Reuwer AQ, Singels L, Stronks K, Essink-Bot M: Laaggeltetterdheid en beperkte gezondheidsvaardigheden vragen om een antwoord in de zorg. Nederlandse Tijdschrift Gennesskunde. 2009, 153 (A250): 1-6.

Wang J, Schmid M: Regional differences in health literacy in Switzerland. 2007, Zürich: University of Zürich. Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine

Kondilis BK, Soteriades ES, Falagas ME: Health literacy research in Europe: a snapshot. Eur J Public Health. 2006, 16 (1): 113-113.

Kondilis BK, Kiriaze IJ, Athanasoulia AP, Falagas ME: Mapping health literacy research in the European union: a bibliometric analysis. PLoS One. 2008, 3 (6): E2519-10.1371/journal.pone.0002519.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

European Commission: Together for health: a strategic approach for the EU 2008-2013. Com(2007) 630 final. 2007

Nutbeam D: Health Promotion Glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998, 13: 349-364. 10.1093/heapro/13.4.349.

Kwan B, Frankish J, Rootman I, Zumbo B, Kelly K, Begoray D, Kazanijan A, Mullet J, Hayes M: The Development and Validation of Measures of "Health Literacy" in Different Populations. 2006, UBC Institute of Health Promotion Research and University of Victoria Community Health Promotion Research

Pleasant A: Proposed Defintion. International Health Association Conference: 2008. 2008

Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer DS: Elaborating a definition of health literacy: a commentary. J Health Commun. 2003, 8 (3): 119-120.

Freedman DA, Bess KD, Tucker HA, Boyd DL, Tuchman AM, Wallston KA: Public health literacy defined. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36 (5): 446-451. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001.

Nutbeam D: Health literacy as a public goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000, 15 (3): 259-267. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259.

Kickbusch I, Wait S, Maag D, Banks I: Navigating health: the role of health literacy. Alliance for Health and the Future, International Longevity Centre, UK. 2006

Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer DS: Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health Promot Int. 2005, 20 (2): 195-203. 10.1093/heapro/dah609.

Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer D: Advancing health literacy: A framework for understanding and action. Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA. 2006

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS: The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007, 31 (Suppl 1): 19-26.

Health Literacy. Programmes for Training on Research in Public Health for South Eastern Europe. Edited by: Pavlekovic G. 2008, 4:

Rootman I, Gordon-El-Bihbety D: A vision for a health literate Canada. 2008, Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association

Mancuso JM: Health literacy: a concept/dimensional analysis. Nurs Health Sci. 2008, 10: 248-255. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00394.x.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Adult literacy and life skills survey. Summary results. 2008, Australia, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 88:

Yost KJ, Webster K, Baker DW, Choi SW, Bode RK, Hahn EA: Bilingual health literacy assessment using the Talking Touchscreen/la Pantalla Parlanchina: development and pilot testing. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 75 (3): 295-301. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.020.

Adkins NR, Corus C: Health literacy for improved health outcomes: effective capital in the marketplace. J Consum Aff. 2009, 43 (2): 199-222. 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2009.01137.x.

Lee SD, Arozullah AM, Choc YI: Health literacy, social support, and health: a research agenda. Soc Sci Med. 2004, 58: 1309-1321. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00329-0.

Speros C: Health literacy: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2005, 50: 633-640. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03448.x.

Baker DW: The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Intern Med. 2006, 21: 878-883.

Manganello JA: Health literacy and adolescents: a framework and agenda for future research. Health Educ Res. 2008, 23 (5): 840-847.

von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf MS, Wardle J: Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Education & Behaviour. 2009, 36 (5): 860-877. 10.1177/1090198108322819.

Nutbeam D: The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 67: 2072-2078. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050.

Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Edited by: Nielson-Bohlman L, Panzer A, Kinding D. 2004

Shoou-Yih D, Leea AMA, Choc Young: Health literacy, social support, and health: a research agenda. Soc Sci Med. 2004, 58: 1309-1321. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00329-0.

Wang R: Critical health literacy: a case study from China in schistosimiasis control. Health Promot Int. 2000, 15 (3): 269-274. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.269.

Levin-Zamir D: Health literacy in health systems: perspectives on patient self-management in Israel. Health Promot Int. 2001, 16 (1): 87-94. 10.1093/heapro/16.1.87.

St Leger L: Schools, health literacy and public health: possibilities and challenges. Health Promotion International. 2001, 16 (2): 197-205. 10.1093/heapro/16.2.197.

Ratzan S: Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promotion International. 2001, 16 (2): 207-214. 10.1093/heapro/16.2.207.

Protheroe J, Wallace L, Rowlands G, DeVoe J: Health literacy: setting an international collaborative research agenda. BMC Fam Pract. 2009, 10 (1): 51-10.1186/1471-2296-10-51.

Magasi S, Durkin E, Wolf MS, Deutsch A: Rehabilitation consumers' use and understanding of quality information: a health literacy perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009, 90 (2): 206-212. 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.023.

Schyve PM: Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the joint commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007, 22 (Suppl 2): 360-361.

McQueen DV, Kickbusch I, Potvin L, Pelikan J, Balbo L, Abel T: Health and Modernity: the Role of Theory in Health Promotion. 2007, New York: Springer

Pleasant A, Kuruvilla SS: A tale of two health literacies: public health and clinical approaches to health literacy. Health Promot Int. 2008, 23 (2): 152-159.

Tones K: Health literacy: new wine in old bottles. Health Educ Res. 2002, 17: 187-189.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/80/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all partners in the HLS-EU consortium for contributing to the development of the conceptual model and the content of this article.

HLS-EU Consortium members

Maastricht University, the Netherlands: Helmut Brand, Stephan van den Broucke and Kristine Sørensen

National School of Public Health, Greece: Demosthenes Agrafiodis, Elizabeth Ioannidis and Barbara Kondilis

University College of Dublin, National University of Ireland: Gerardine Doyle, James Fullam and Kenneth Cafferkey

Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft GmbH, Austria: Jürgen Pelikan and Florian Röethlin

Instytut Kardiologii, Poland: Zofia Slonska

University of Murcia, Spain: Maria Falcon

Medical University - Sofia, Bulgaria: Kancho Tchamov and Alex Zhekov

National Institute of Public Health and the Environment, The Netherlands: Mariël Droomers, Jantine Schuit, Iris van der Heide and Ellen Uiters

NRW Centre for Health, Germany: Gudula Ward and Monika Mensing

The HLS-EU project and related research are supported by grant 2007-113 from the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of International Health, Research School of Primary Care and Public Health, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Kristine Sørensen & Helmut Brand

Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

Stephan Van den Broucke

University College Dublin, National University of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

James Fullam & Gerardine Doyle

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute Health Promotion Research, Vienna, Austria

Jürgen Pelikan

National Institute of Cardiology, Warsaw, Poland

Zofia Slonska

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kristine Sørensen .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors are members of the European Health Literacy (HLS-EU) consortium and claim to have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Background: KS, SVDB, JF, GD. Methodology: KS, SVDB, JF. Results: KS, SVDB, HB, JF, GD, ZS and JP. Discussion: KS, SVDB, HB, JF, GD, ZS and JP. Conclusion: KS, SVDB, JF and GD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Kristine Sørensen, Stephan Van den Broucke, James Fullam, Gerardine Doyle and Helmut Brand contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J. et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 12 , 80 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

Download citation

Received : 25 November 2011

Accepted : 25 January 2012

Published : 25 January 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health Literacy

- Functional Health Literacy

- Health Literacy Skill

- Public Health Literacy

- Poor Health Literacy

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Problem-based learning in academic health education. A systematic literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Restorative Dentistry and Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. [email protected]

- PMID: 20070800

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00593.x

Problem based learning (PBL) arguably represents the most significant development in education over the past five decades. It has been promoted as the curriculum of choice, and since its introduction in the 1960's, has been widely adopted by many medical and dental schools. PBL has been the subject of much published literature but ironically, very little high quality evidence exists to advocate its efficacy and subsequently justify the widespread curriculum change. The purpose of this review is to classify and interpret the available evidence and extract relevant conclusions. In addition, it is the intent to propose recommendations regarding the relative benefits of PBL compared with conventional teaching. The literature was searched using PubMed, ERIC and PsycLIT. Further articles were retrieved from the reference lists of selected papers. Articles were chosen and included according to specific selection criteria. Studies were further classified as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or comparative studies. These studies were then analysed according to intervention type: whole curricula comparisons and single educational interventions of shorter duration. At the level of RCTs and comparative studies (whole curricula), no clear difference was observed between PBL and conventional teaching. Paradoxically, it was only comparative studies of single PBL intervention in a traditional curriculum that yielded results that were consistently in favour of PBL. Further research is needed to investigate the possibility that multiple PBL interventions in a traditional curriculum could be more effective than an exclusively PBL programme. In addition, it is important to address the potential benefits of PBL in relation to life-long learning of health care professionals.

PubMed Disclaimer

- Problem-based learning interventions in a traditional curriculum are an effective learning tool. Townsend G. Townsend G. Evid Based Dent. 2011 Dec;12(4):115-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400829. Evid Based Dent. 2011. PMID: 22193657

Similar articles

- Does a PBL-based medical curriculum predispose training in specific career paths? A systematic review of the literature. Tsigarides J, Wingfield LR, Kulendran M. Tsigarides J, et al. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Jan 7;10(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2348-0. BMC Res Notes. 2017. PMID: 28061800 Free PMC article. Review.

- Educational technologies in problem-based learning in health sciences education: a systematic review. Jin J, Bridges SM. Jin J, et al. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Dec 10;16(12):e251. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3240. J Med Internet Res. 2014. PMID: 25498126 Free PMC article. Review.

- Problem-based learning in dental education: a systematic review of the literature. Bassir SH, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Amirikhorheh S, Karimbux NY. Bassir SH, et al. J Dent Educ. 2014 Jan;78(1):98-109. J Dent Educ. 2014. PMID: 24385529 Review.

- Challenges of teaching physiology in a PBL school. Abdul-Ghaffar TA, Lukowiak K, Nayar U. Abdul-Ghaffar TA, et al. Am J Physiol. 1999 Dec;277(6 Pt 2):S140-7. doi: 10.1152/advances.1999.277.6.S140. Am J Physiol. 1999. PMID: 10644240

- Facilitators and barriers to online group work in higher education within health sciences - a scoping review. Edvardsen Tonheim L, Molin M, Brevik A, Wøhlk Gundersen M, Garnweidner-Holme L. Edvardsen Tonheim L, et al. Med Educ Online. 2024 Dec 31;29(1):2341508. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2024.2341508. Epub 2024 Apr 12. Med Educ Online. 2024. PMID: 38608002 Free PMC article. Review.

- Effects of six teaching strategies on medical students: protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Zhang S, Zhu D, Wang X, Liu T, Wang L, Fan X, Gong H. Zhang S, et al. BMJ Open. 2024 Jan 30;14(1):e079716. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079716. BMJ Open. 2024. PMID: 38296281 Free PMC article.

- Active learning in undergraduate classroom dental education- a scoping review. Perez A, Green J, Moharrami M, Gianoni-Capenakas S, Kebbe M, Ganatra S, Ball G, Sharmin N. Perez A, et al. PLoS One. 2023 Oct 26;18(10):e0293206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293206. eCollection 2023. PLoS One. 2023. PMID: 37883431 Free PMC article.

- Assessing predictors of students' academic performance in Ethiopian new medical schools: a concurrent mixed-method study. Gebru HT, Verstegen D. Gebru HT, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Jun 17;23(1):448. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04372-4. BMC Med Educ. 2023. PMID: 37330493 Free PMC article.

- Experiential student study groups: perspectives on medical education in the post-COVID-19 period. Lazari EC, Mylonas CC, Thomopoulou GE, Manou E, Nastos C, Kavantzas N, Pikoulis E, Lazaris AC. Lazari EC, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Jan 19;23(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04006-9. BMC Med Educ. 2023. PMID: 36658528 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 December 2010

Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review

- Robert Battat 1 ,

- Gillian Seidman 1 ,

- Nicholas Chadi 1 ,

- Mohammed Y Chanda 1 ,

- Jessica Nehme 1 ,

- Jennifer Hulme 1 ,

- Annie Li 1 ,

- Nazlie Faridi 1 &

- Timothy F Brewer 1

BMC Medical Education volume 10 , Article number: 94 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

164 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Physicians today are increasingly faced with healthcare challenges that require an understanding of global health trends and practices, yet little is known about what constitutes appropriate global health training.

A literature review was undertaken to identify competencies and educational approaches for teaching global health in medical schools.

Using a pre-defined search strategy, 32 articles were identified; 11 articles describing 15 global health competencies for undergraduate medical training were found. The most frequently mentioned competencies included an understanding of: the global burden of disease, travel medicine, healthcare disparities between countries, immigrant health, primary care within diverse cultural settings and skills to better interface with different populations, cultures and healthcare systems. However, no consensus on global health competencies for medical students was apparent. Didactics and experiential learning were the most common educational methods used, mentioned in 12 and 13 articles respectively. Of the 11 articles discussing competencies, 8 linked competencies directly to educational approaches.

Conclusions

This review highlights the imperative to document global health educational competencies and approaches used in medical schools and the need to facilitate greater consensus amongst medical educators on appropriate global health training for future physicians.

Peer Review reports

Health issues are increasingly transnational and in recent years the concept of global health has emerged to address these issues. Global health is the study and practice of improving health and health equity for all people worldwide through international and interdisciplinary collaboration [ 1 ]. Factors such as increasing international travel, the globalization of food supplies and commerce and the occurrence of multinational epidemics including the 2009 Influenza A pandemic have heightened awareness of global health issues. This awareness has influenced health practices and medical education locally and globally. Internationally, large-scale multinational public health programs such as the UN Millennium Development Goals, the Global Fund and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS relief have been created and funded with billions of dollars [ 2 ]. More locally, medical schools increasingly are offering international elective opportunities; almost one-third of recently graduated US and Canadian medical students participated in a global health experience [ 3 ]. However, despite growing interest in and the importance of global health, there exists little agreement on what constitutes appropriate global health training for medical students [ 4 ].

It has been argued that all medical students should have some exposure to global health issues, and groups are addressing this perceived gap in medical education by proposing global health competencies for undergraduate medical education [ 2 , 5 , 6 ]. In order to develop initial guidance in this area, this study reviewed existing literature to identify competencies and educational approaches recommended for teaching global health components in medical curricula. Using this information, a consensus was sought in order to further solidify this conceptual framework.

Data Sources and Searches

Relevant articles on global health competencies and teaching approaches were identified by applying similar search strategies to two databases, Ovid MEDLINE ® and Web of Science. Also, previously identified articles were obtained from the McGill Global Health Programs files. The Ovid MEDLINE ® search terms "world health" and "international educational exchange" were combined using the Boolean operator "OR" for the publication years 1996 to the 4 th week of January 2009. The initial search used the terms "global health" and "international health"; however, these terms mapped to the subject heading "world health" in the Ovid MEDLINE ® database. This procedure was repeated using the search terms "education, medical" and "education, medical, undergraduate", which was then cross-referenced with the search term "competencies". The resulting "education, medical"/"curriculum" set was combined with the resulting "world health"/"international educational exchange" set using the Boolean operator "AND". The results of the search were limited to humans and English. The Web of Science search cross-referenced the terms "medical education", "curriculum" and "global health" as topics for the publication years "all years" i.e. from 1900-1914 to January 2009. A research team comprised of all authors in this study, as well as the Liaison Librarian in the Life Sciences Library at McGill University, agreed upon these terms with the aim of avoiding researcher bias when selecting the articles. References from retrieved articles were reviewed to identify additional applicable publications.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts of articles obtained from database searches were reviewed to identify those describing competencies or educational approaches currently used in global health components of medical school curricula. Articles not pertaining to contemporary global health medical educational practices or competencies were not further considered.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Information relating to competencies and educational approaches was extracted from the retained articles. Information discussing the theoretical knowledge or practical skills authors believed medical students needed to obtain was categorized as a competency. Descriptions of specific programs or teaching methods were categorized as educational approaches.

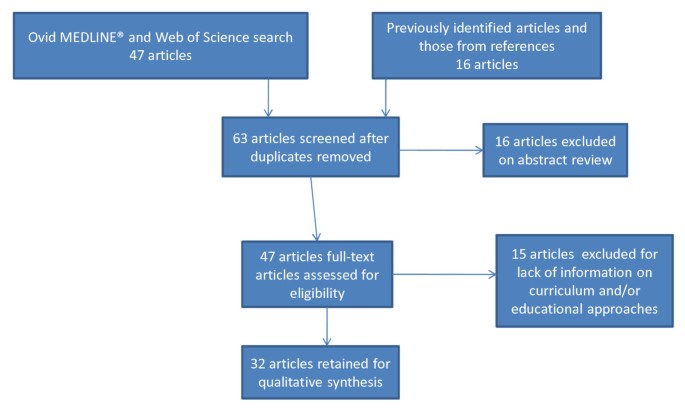

The results of the search strategy on global health competencies and educational approaches are summarized in Figure 1 . The Ovid database search strategy yielded forty-five articles. The Web of Science search yielded two additional articles not found in the Ovid database[ 7 , 8 ]. Twelve more articles were found through reviewing references from retrieved articles[ 6 , 9 – 19 ]. Four other articles were obtained from the McGill Global Health Programs files[ 20 – 23 ]. Combining all of the search efforts and removing duplications, 63 articles were available for consideration. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 47 were retained for further consideration. Following a full review of the remaining articles, 32 articles were felt to contain relevant information and were included in the review.

Search strategy for retrieving literature on global health competencies and educational approaches .

The percentage of articles recommending a particular competency topic, the type of competency and the suggested method of implementation are summarized in Table 1 . Fifteen unique global health competencies for training medical students from 11 articles (34.4%) were identified in the literature [ 7 , 10 , 17 – 19 , 24 – 29 ]. Most competencies were concerned with increasing medical students' knowledge, though some addressed physician behaviour, physical examination abilities and other clinical skills. Competencies mentioned in more than one article included: an understanding of the global burden of disease; travel medicine; healthcare disparities between countries; immigrant health; primary care within diverse cultural settings; and skills to better interface with different populations, cultures and healthcare systems. All other competencies were mentioned only by a single article.

Global health educational approaches were described in 18 of 32 (56.3%) identified articles [ 6 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 13 , 15 – 17 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 26 , 28 – 33 ]. The percentage of articles recommending a particular educational approach, and the suggested methods for implementing that approach, are summarized in Table 2 .

The most common recommended educational approaches for teaching global health topics were didactics and experiential learning. However, there was substantial variability across described programs in the educational approach to global health as well as the methods used to implement these approaches. No commonly applied didactic method for teaching global health to medical students was apparent from this literature review. Moreover, descriptions of educational approaches often did not provide a tangible picture of what occurred in these programs.

Competencies and educational approaches were linked in 8 (25.0%) articles [ 7 , 10 , 17 , 19 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 ]. Eleven articles (34.4%) mentioned global health educational approaches or competencies for medical students, but did not provide sufficient detail to be used further [ 5 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 34 – 36 ]. Although these articles met search criteria, they tended to discuss international partnerships and suggestions for future endeavors rather than specifics regarding contemporary program competencies or educational approaches.

Interest in global health has grown dramatically among medical students in the past decade, and medical schools are grappling to define the skill sets and knowledge needed to ensure that graduates are appropriately prepared to work in this emerging field. Successful global health educational programs exist, and we explored the medical literature to identify competencies and educational approaches that might serve as potential resources for medical schools developing their own training programs. This literature review found no clear consensus on which global health competencies are relevant for most or all medical graduates to be able to draw on as future physicians. There also was little guidance regarding educational approaches for teaching global health competencies beyond the traditional methods of didactics and experiential learning.

Fifteen competencies were mentioned in the literature. The most commonly discussed ones included an understanding of the global burden of disease; travel medicine; healthcare disparities between countries; immigrant health; primary care within diverse cultural settings; and skills to better interface with different populations, cultures and healthcare systems. Although these competencies were mentioned in more than one article, no single topic area was covered in more than 16% of identified articles, suggesting a lack of consensus on the importance assigned to any particular subject. It is not possible from this review to determine why a lack of consensus exists; one possibility may be that medical schools developed their global health curricula independent of each other. Such an approach may foster innovation, but also means that the quality of resulting programs is likely to vary widely as was found in a review of global health programs [ 4 ]. Developing consensus on global health competencies would help ensure that all medical students were exposed to similar basic levels of training.

An alternative explanation for the lack of consensus in the retrieved articles is that published literature does not reflect common practice. Despite the tremendous growth in global health programs, only 11 articles were identified that addressed competencies. Furthermore, competencies were rarely the main focus of retrieved articles, giving little information on which to draw conclusions. A general consensus may exist among global health experts not reflected by the published literature.

The most common educational approaches for teaching global health were didactics and experiential learning. However, the implementation of these approaches varied considerably in the literature. Our review was hampered by the limited descriptions of educational approaches present in identified articles that may not have provided a complete picture of these programs. More detailed documentation of global health educational approaches is needed if the literature is to serve as a resource for medical schools developing new programs.

Of the 11 articles addressing competencies, 8 (72.7%) linked them to an educational approach. Conversely, educational approaches were mentioned in a majority of articles, but less than half of these linked these approaches to a competency. Competency-based descriptions of training give a more complete picture of global health education in medical curricula; schools looking to build global health educational activities should begin by defining the desired competencies, followed by enumerating the educational approaches to be used to teach them.

Over one-third of retrieved articles did not provide specific details regarding global health educational approaches or competencies despite the search strategy used. These articles often focused on the creation of international institutional partnerships to improve the quality and pace of global health curriculum development. However, establishing learning objectives and corresponding educational approaches should be prerequisites for undertaking activities such as international global health partnerships. This review highlights another potential weakness in existing global health training; medical schools may be pursuing secondary activities before establishing basic program components such as competencies and educational approaches. Without well thought-out competencies and educational approaches, medical students may lack the foundation necessary to participate in international global health programs.

Steps are underway to build consensus among global health experts regarding basic global health training for medical students. For example, the Global Health Education Consortium (GHEC) and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) Resource Group on Global Health have created a joint committee to propose consensus global health core competencies for medical students [ 2 ]. Recently, a number of leading university-based global health programs came together to form the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH). CUGH is another potential forum for sharing global health program development information across schools. Locally, we have used the results of this review to add global burden of disease and travel-associated health topic areas to our curriculum. We suggest that medical schools use a competency based approach when developing global health programs. Educational approaches can then be linked to the learning objectives they are designed to teach. Documenting this information in the literature will facilitate the ability of medical schools to compare competencies and educational approaches being used across programs, and may stimulate consensus on appropriate global health training for medical students. Comparative studies also should be undertaken to measure how global health training affects clinical practice. Helping medical schools build appropriate global health components into their curricula should make physicians more informed and better equipped to care for patients in this increasingly globalized world.

Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, Wasserheit JN, Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive B: Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9679): 1993-1995. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9.

Article Google Scholar

Brewer TF, Saba N, Clair V: From boutique to basic: a call for standardised medical education in global health. Med Educ. 2009, 43 (10): 930-933. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03458.x.

Association of American Medical Colleges: GQ Program Evaluation Survey. All Schools Summary Report Final. Washington DA

Izadnegahdar R, Correia S, Ohata B, Kittler A, ter Kuile S, Vaillancourt S, Saba N, Brewer TF: Global health in Canadian medical education: current practices and opportunities. Acad Med. 2008, 83 (2): 192-198. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816095cd.

Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P: Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007, 82 (3): 226-230. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9.

Saba N, Brewer TF: Beyond borders: building global health programs at McGill University Faculty of Medicine. Acad Med. 2008, 83 (2): 185-191. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816094fc.

Fox GJ, Thompson JE, Bourke VC, Moloney G: Medical students, medical schools and international health. Med J Aust. 2007, 187 (9): 536-539.

Google Scholar

Evert J, Bazemore A, Hixon A, Withy K: Going global: considerations for introducing global health into family medicine training programs. Fam Med. 2007, 39 (9): 659-665.

Bonita S, et al: Global Health Training for Pediatric Residents. Pediatr Ann. 2008, 37 (12): 786-787. 10.3928/00904481-20081201-11. 792-786

Chiller TM, De Mieri P, Cohen I: International health training. The Tulane experience. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995, 9 (2): 439-443.

Crump JA JS: Ethical considerations for short-term experiences by trainees in global health. JAMA. 2008, 300 (12): 1456-1458. 10.1001/jama.300.12.1456.

el Ansari W, Russell J, Spence W, Ryder E, Chambers C: New skills for a new age: leading the introduction of public health concepts in healthcare curricula. Public Health. 2003, 117 (2): 77-87. 10.1016/S0033-3506(02)00020-3.

Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, Bobula J, Wilson C, Bickley L, Cardelle A, Joseph A: New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000, 32 (8): 566-572.