- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Violence, media effects, and criminology.

- Nickie D. Phillips Nickie D. Phillips Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, St. Francis College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.189

- Published online: 27 July 2017

Debate surrounding the impact of media representations on violence and crime has raged for decades and shows no sign of abating. Over the years, the targets of concern have shifted from film to comic books to television to video games, but the central questions remain the same. What is the relationship between popular media and audience emotions, attitudes, and behaviors? While media effects research covers a vast range of topics—from the study of its persuasive effects in advertising to its positive impact on emotions and behaviors—of particular interest to criminologists is the relationship between violence in popular media and real-life aggression and violence. Does media violence cause aggression and/or violence?

The study of media effects is informed by a variety of theoretical perspectives and spans many disciplines including communications and media studies, psychology, medicine, sociology, and criminology. Decades of research have amassed on the topic, yet there is no clear agreement about the impact of media or about which methodologies are most appropriate. Instead, there continues to be disagreement about whether media portrayals of violence are a serious problem and, if so, how society should respond.

Conflicting interpretations of research findings inform and shape public debate around media effects. Although there seems to be a consensus among scholars that exposure to media violence impacts aggression, there is less agreement around its potential impact on violence and criminal behavior. While a few criminologists focus on the phenomenon of copycat crimes, most rarely engage with whether media directly causes violence. Instead, they explore broader considerations of the relationship between media, popular culture, and society.

- media exposure

- criminal behavior

- popular culture

- media violence

- media and crime

- copycat crimes

Media Exposure, Violence, and Aggression

On Friday July 22, 2016 , a gunman killed nine people at a mall in Munich, Germany. The 18-year-old shooter was subsequently characterized by the media as being under psychiatric care and harboring at least two obsessions. One, an obsession with mass shootings, including that of Anders Breivik who ultimately killed 77 people in Norway in 2011 , and the other an obsession with video games. A Los Angeles, California, news report stated that the gunman was “an avid player of first-person shooter video games, including ‘Counter-Strike,’” while another headline similarly declared, “Munich gunman, a fan of violent video games, rampage killers, had planned attack for a year”(CNN Wire, 2016 ; Reuters, 2016 ). This high-profile incident was hardly the first to link popular culture to violent crime. Notably, in the aftermath of the 1999 Columbine shooting massacre, for example, media sources implicated and later discredited music, video games, and a gothic aesthetic as causal factors of the crime (Cullen, 2009 ; Yamato, 2016 ). Other, more recent, incidents have echoed similar claims suggesting that popular culture has a nefarious influence on consumers.

Media violence and its impact on audiences are among the most researched and examined topics in communications studies (Hetsroni, 2007 ). Yet, debate over whether media violence causes aggression and violence persists, particularly in response to high-profile criminal incidents. Blaming video games, and other forms of media and popular culture, as contributing to violence is not a new phenomenon. However, interpreting media effects can be difficult because commenters often seem to indicate a grand consensus that understates more contradictory and nuanced interpretations of the data.

In fact, there is a consensus among many media researchers that media violence has an impact on aggression although its impact on violence is less clear. For example, in response to the shooting in Munich, Brad Bushman, professor of communication and psychology, avoided pinning the incident solely on video games, but in the process supported the assertion that video gameplay is linked to aggression. He stated,

While there isn’t complete consensus in any scientific field, a study we conducted showed more than 90% of pediatricians and about two-thirds of media researchers surveyed agreed that violent video games increase aggression in children. (Bushman, 2016 )

Others, too, have reached similar conclusions with regard to other media. In 2008 , psychologist John Murray summarized decades of research stating, “Fifty years of research on the effect of TV violence on children leads to the inescapable conclusion that viewing media violence is related to increases in aggressive attitudes, values, and behaviors” (Murray, 2008 , p. 1212). Scholars Glenn Sparks and Cheri Sparks similarly declared that,

Despite the fact that controversy still exists about the impact of media violence, the research results reveal a dominant and consistent pattern in favor of the notion that exposure to violent media images does increase the risk of aggressive behavior. (Sparks & Sparks, 2002 , p. 273)

In 2014 , psychologist Wayne Warburton more broadly concluded that the vast majority of studies have found “that exposure to violent media increases the likelihood of aggressive behavior in the short and longterm, increases hostile perceptions and attitudes, and desensitizes individuals to violent content” (Warburton, 2014 , p. 64).

Criminologists, too, are sensitive to the impact of media exposure. For example, Jacqueline Helfgott summarized the research:

There have been over 1000 studies on the effects of TV and film violence over the past 40 years. Research on the influence of TV violence on aggression has consistently shown that TV violence increases aggression and social anxiety, cultivates a “mean view” of the world, and negatively impacts real-world behavior. (Helfgott, 2015 , p. 50)

In his book, Media Coverage of Crime and Criminal Justice , criminologist Matthew Robinson stated, “Studies of the impact of media on violence are crystal clear in their findings and implications for society” (Robinson, 2011 , p. 135). He cited studies on childhood exposure to violent media leading to aggressive behavior as evidence. In his pioneering book Media, Crime, and Criminal Justice , criminologist Ray Surette concurred that media violence is linked to aggression, but offered a nuanced interpretation. He stated,

a small to modest but genuine causal role for media violence regarding viewer aggression has been established for most beyond a reasonable doubt . . . There is certainly a connection between violent media and social aggression, but its strength and configuration is simply not known at this time. (Surette, 2011 , p. 68)

The uncertainties about the strength of the relationship and the lack of evidence linking media violence to real-world violence is often lost in the news media accounts of high-profile violent crimes.

Media Exposure and Copycat Crimes

While many scholars do seem to agree that there is evidence that media violence—whether that of film, TV, or video games—increases aggression, they disagree about its impact on violent or criminal behavior (Ferguson, 2014 ; Gunter, 2008 ; Helfgott, 2015 ; Reiner, 2002 ; Savage, 2008 ). Nonetheless, it is violent incidents that most often prompt speculation that media causes violence. More specifically, violence that appears to mimic portrayals of violent media tends to ignite controversy. For example, the idea that films contribute to violent crime is not a new assertion. Films such as A Clockwork Orange , Menace II Society , Set it Off , and Child’s Play 3 , have been linked to crimes and at least eight murders have been linked to Oliver Stone’s 1994 film Natural Born Killers (Bracci, 2010 ; Brooks, 2002 ; PBS, n.d. ). Nonetheless, pinpointing a direct, causal relationship between media and violent crime remains elusive.

Criminologist Jacqueline Helfgott defined copycat crime as a “crime that is inspired by another crime” (Helfgott, 2015 , p. 51). The idea is that offenders model their behavior on media representations of violence whether real or fictional. One case, in particular, illustrated how popular culture, media, and criminal violence converge. On July 20, 2012 , James Holmes entered the midnight premiere of The Dark Knight Rises , the third film in the massively successful Batman trilogy, in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. He shot and killed 12 people and wounded 70 others. At the time, the New York Times described the incident,

Witnesses told the police that Mr. Holmes said something to the effect of “I am the Joker,” according to a federal law enforcement official, and that his hair had been dyed or he was wearing a wig. Then, as people began to rise from their seats in confusion or anxiety, he began to shoot. The gunman paused at least once, several witnesses said, perhaps to reload, and continued firing. (Frosch & Johnson, 2012 ).

The dyed hair, Holme’s alleged comment, and that the incident occurred at a popular screening led many to speculate that the shooter was influenced by the earlier film in the trilogy and reignited debate around the impact about media violence. The Daily Mail pointed out that Holmes may have been motivated by a 25-year-old Batman comic in which a gunman opens fire in a movie theater—thus further suggesting the iconic villain served as motivation for the attack (Graham & Gallagher, 2012 ). Perceptions of the “Joker connection” fed into the notion that popular media has a direct causal influence on violent behavior even as press reports later indicated that Holmes had not, in fact, made reference to the Joker (Meyer, 2015 ).

A week after the Aurora shooting, the New York Daily News published an article detailing a “possible copycat” crime. A suspect was arrested in his Maryland home after making threatening phone calls to his workplace. The article reported that the suspect stated, “I am a [sic] joker” and “I’m going to load my guns and blow everybody up.” In their search, police found “a lethal arsenal of 25 guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition” in the suspect’s home (McShane, 2012 ).

Though criminologists are generally skeptical that those who commit violent crimes are motivated solely by media violence, there does seem to be some evidence that media may be influential in shaping how some offenders commit crime. In his study of serious and violent juvenile offenders, criminologist Ray Surette found “about one out of three juveniles reports having considered a copycat crime and about one out of four reports actually having attempted one.” He concluded that “those juveniles who are self-reported copycats are significantly more likely to credit the media as both a general and personal influence.” Surette contended that though violent offenses garner the most media attention, copycat criminals are more likely to be career criminals and to commit property crimes rather than violent crimes (Surette, 2002 , pp. 56, 63; Surette 2011 ).

Discerning what crimes may be classified as copycat crimes is a challenge. Jacqueline Helfgott suggested they occur on a “continuum of influence.” On one end, she said, media plays a relatively minor role in being a “component of the modus operandi” of the offender, while on the other end, she said, “personality disordered media junkies” have difficulty distinguishing reality from violent fantasy. According to Helfgott, various factors such as individual characteristics, characteristics of media sources, relationship to media, demographic factors, and cultural factors are influential. Overall, scholars suggest that rather than pushing unsuspecting viewers to commit crimes, media more often influences how , rather than why, someone commits a crime (Helfgott, 2015 ; Marsh & Melville, 2014 ).

Given the public interest, there is relatively little research devoted to exactly what copycat crimes are and how they occur. Part of the problem of studying these types of crimes is the difficulty defining and measuring the concept. In an effort to clarify and empirically measure the phenomenon, Surette offered a scale that included seven indicators of copycat crimes. He used the following factors to identify copycat crimes: time order (media exposure must occur before the crime); time proximity (a five-year cut-off point of exposure); theme consistency (“a pattern of thought, feeling or behavior in the offender which closely parallels the media model”); scene specificity (mimicking a specific scene); repetitive viewing; self-editing (repeated viewing of single scene while “the balance of the film is ignored”); and offender statements and second-party statements indicating the influence of media. Findings demonstrated that cases are often prematurely, if not erroneously, labeled as “copycat.” Surette suggested that use of the scale offers a more precise way for researchers to objectively measure trends and frequency of copycat crimes (Surette, 2016 , p. 8).

Media Exposure and Violent Crimes

Overall, a causal link between media exposure and violent criminal behavior has yet to be validated, and most researchers steer clear of making such causal assumptions. Instead, many emphasize that media does not directly cause aggression and violence so much as operate as a risk factor among other variables (Bushman & Anderson, 2015 ; Warburton, 2014 ). In their review of media effects, Brad Bushman and psychologist Craig Anderson concluded,

In sum, extant research shows that media violence is a causal risk factor not only for mild forms of aggression but also for more serious forms of aggression, including violent criminal behavior. That does not mean that violent media exposure by itself will turn a normal child or adolescent who has few or no other risk factors into a violent criminal or a school shooter. Such extreme violence is rare, and tends to occur only when multiple risk factors converge in time, space, and within an individual. (Bushman & Anderson, 2015 , p. 1817)

Surette, however, argued that there is no clear linkage between media exposure and criminal behavior—violent or otherwise. In other words, a link between media violence and aggression does not necessarily mean that exposure to violent media causes violent (or nonviolent) criminal behavior. Though there are thousands of articles addressing media effects, many of these consist of reviews or commentary about prior research findings rather than original studies (Brown, 2007 ; Murray, 2008 ; Savage, 2008 ; Surette, 2011 ). Fewer, still, are studies that specifically measure media violence and criminal behavior (Gunter, 2008 ; Strasburger & Donnerstein, 2014 ). In their meta-analysis investigating the link between media violence and criminal aggression, scholars Joanne Savage and Christina Yancey did not find support for the assertion. Instead, they concluded,

The study of most consequence for violent crime policy actually found that exposure to media violence was significantly negatively related to violent crime rates at the aggregate level . . . It is plain to us that the relationship between exposure to violent media and serious violence has yet to be established. (Savage & Yancey, 2008 , p. 786)

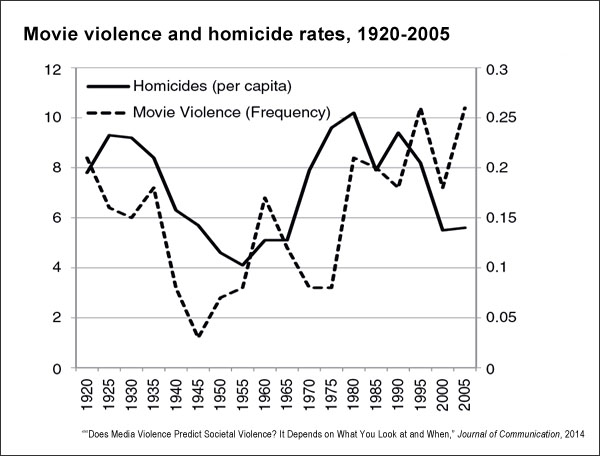

Researchers continue to measure the impact of media violence among various forms of media and generally stop short of drawing a direct causal link in favor of more indirect effects. For example, one study examined the increase of gun violence in films over the years and concluded that violent scenes provide scripts for youth that justify gun violence that, in turn, may amplify aggression (Bushman, Jamieson, Weitz, & Romer, 2013 ). But others report contradictory findings. Patrick Markey and colleagues studied the relationship between rates of homicide and aggravated assault and gun violence in films from 1960–2012 and found that over the years, violent content in films increased while crime rates declined . After controlling for age shifts, poverty, education, incarceration rates, and economic inequality, the relationships remained statistically non-significant (Markey, French, & Markey, 2015 , p. 165). Psychologist Christopher Ferguson also failed to find a relationship between media violence in films and video games and violence (Ferguson, 2014 ).

Another study, by Gordon Dahl and Stefano DellaVigna, examined violent films from 1995–2004 and found decreases in violent crimes coincided with violent blockbuster movie attendance. Here, it was not the content that was alleged to impact crime rates, but instead what the authors called “voluntary incapacitation,” or the shifting of daily activities from that of potential criminal behavior to movie attendance. The authors concluded, “For each million people watching a strongly or mildly violent movie, respectively, violent crime decreases by 1.9% and 2.1%. Nonviolent movies have no statistically significant impact” (Dahl & DellaVigna, p. 39).

High-profile cases over the last several years have shifted public concern toward the perceived danger of video games, but research demonstrating a link between video games and criminal violence remains scant. The American Psychiatric Association declared that “research demonstrates a consistent relation between violent video game use and increases in aggressive behavior, aggressive cognitions and aggressive affect, and decreases in prosocial behavior, empathy and sensitivity to aggression . . .” but stopped short of claiming that video games impact criminal violence. According to Breuer and colleagues, “While all of the available meta-analyses . . . found a relationship between aggression and the use of (violent) video games, the size and interpretation of this connection differ largely between these studies . . .” (APA, 2015 ; Breuer et al., 2015 ; DeCamp, 2015 ). Further, psychologists Patrick Markey, Charlotte Markey, and Juliana French conducted four time-series analyses investigating the relationship between video game habits and assault and homicide rates. The studies measured rates of violent crime, the annual and monthly video game sales, Internet searches for video game walkthroughs, and rates of violent crime occurring after the release dates of popular games. The results showed that there was no relationship between video game habits and rates of aggravated assault and homicide. Instead, there was some indication of decreases in crime (Markey, Markey, & French, 2015 ).

Another longitudinal study failed to find video games as a predictor of aggression, instead finding support for the “selection hypothesis”—that physically aggressive individuals (aged 14–17) were more likely to choose media content that contained violence than those slightly older, aged 18–21. Additionally, the researchers concluded,

that violent media do not have a substantial impact on aggressive personality or behavior, at least in the phases of late adolescence and early adulthood that we focused on. (Breuer, Vogelgesang, Quandt, & Festl, 2015 , p. 324)

Overall, the lack of a consistent finding demonstrating that media exposure causes violent crime may not be particularly surprising given that studies linking media exposure, aggression, and violence suffer from a host of general criticisms. By way of explanation, social theorist David Gauntlett maintained that researchers frequently employ problematic definitions of aggression and violence, questionable methodologies, rely too much on fictional violence, neglect the social meaning of violence, and assume the third-person effect—that is, assume that other, vulnerable people are impacted by media, but “we” are not (Ferguson & Dyck, 2012 ; Gauntlett, 2001 ).

Others, such as scholars Martin Barker and Julian Petley, flatly reject the notion that violent media exposure is a causal factor for aggression and/or violence. In their book Ill Effects , the authors stated instead that it is simply “stupid” to query about “what are the effects of [media] violence” without taking context into account (p. 2). They counter what they describe as moral campaigners who advance the idea that media violence causes violence. Instead, Barker and Petley argue that audiences interpret media violence in a variety of ways based on their histories, experiences, and knowledge, and as such, it makes little sense to claim media “cause” violence (Barker & Petley, 2001 ).

Given the seemingly inconclusive and contradictory findings regarding media effects research, to say that the debate can, at times, be contentious is an understatement. One article published in European Psychologist queried “Does Doing Media Violence Research Make One Aggressive?” and lamented that the debate had devolved into an ideological one (Elson & Ferguson, 2013 ). Another academic journal published a special issue devoted to video games and youth and included a transcript of exchanges between two scholars to demonstrate that a “peaceful debate” was, in fact, possible (Ferguson & Konijn, 2015 ).

Nonetheless, in this debate, the stakes are high and the policy consequences profound. After examining over 900 published articles, publication patterns, prominent authors and coauthors, and disciplinary interest in the topic, scholar James Anderson argued that prominent media effects scholars, whom he deems the “causationists,” had developed a cottage industry dependent on funding by agencies focused primarily on the negative effects of media on children. Anderson argued that such a focus presents media as a threat to family values and ultimately operates as a zero-sum game. As a result, attention and resources are diverted toward media and away from other priorities that are essential to understanding aggression such as social disadvantage, substance abuse, and parental conflict (Anderson, 2008 , p. 1276).

Theoretical Perspectives on Media Effects

Understanding how media may impact attitudes and behavior has been the focus of media and communications studies for decades. Numerous theoretical perspectives offer insight into how and to what extent the media impacts the audience. As scholar Jenny Kitzinger documented in 2004 , there are generally two ways to approach the study of media effects. One is to foreground the power of media. That is, to suggest that the media holds powerful sway over viewers. Another perspective is to foreground the power and heterogeneity of the audience and to recognize that it is comprised of active agents (Kitzinger, 2004 ).

The notion of an all-powerful media can be traced to the influence of scholars affiliated with the Institute for Social Research, or Frankfurt School, in the 1930–1940s and proponents of the mass society theory. The institute was originally founded in Germany but later moved to the United States. Criminologist Yvonne Jewkes outlined how mass society theory assumed that members of the public were susceptible to media messages. This, theorists argued, was a result of rapidly changing social conditions and industrialization that produced isolated, impressionable individuals “cut adrift from kinship and organic ties and lacking moral cohesion” (Jewkes, 2015 , p. 13). In this historical context, in the era of World War II, the impact of Nazi propaganda was particularly resonant. Here, the media was believed to exhibit a unidirectional flow, operating as a powerful force influencing the masses. The most useful metaphor for this perspective described the media as a “hypodermic syringe” that could “‘inject’ values, ideas and information directly into the passive receiver producing direct and unmediated ‘effects’” (Jewkes, 2015 , pp. 16, 34). Though the hypodermic syringe model seems simplistic today, the idea that the media is all-powerful continues to inform contemporary public discourse around media and violence.

Concern of the power of media captured the attention of researchers interested in its purported negative impact on children. In one of the earliest series of studies in the United States during the late 1920s–1930s, researchers attempted to quantitatively measure media effects with the Payne Fund Studies. For example, they investigated how film, a relatively new medium, impacted children’s attitudes and behaviors, including antisocial and violent behavior. At the time, the Payne Fund Studies’ findings fueled the notion that children were indeed negatively influenced by films. This prompted the film industry to adopt a self-imposed code regulating content (Sparks & Sparks, 2002 ; Surette, 2011 ). Not everyone agreed with the approach. In fact, the methodologies employed in the studies received much criticism, and ultimately, the movement was branded as a moral crusade to regulate film content. Scholars Garth Jowett, Ian Jarvie, and Kathryn Fuller wrote about the significance of the studies,

We have seen this same policy battle fought and refought over radio, television, rock and roll, music videos and video games. Their researchers looked to see if intuitive concerns could be given concrete, measurable expression in research. While they had partial success, as have all subsequent efforts, they also ran into intractable problems . . . Since that day, no way has yet been found to resolve the dilemma of cause and effect: do crime movies create more crime, or do the criminally inclined enjoy and perhaps imitate crime movies? (Jowett, Jarvie, & Fuller, 1996 , p. 12)

As the debate continued, more sophisticated theoretical perspectives emerged. Efforts to empirically measure the impact of media on aggression and violence continued, albeit with equivocal results. In the 1950s and 1960s, psychological behaviorism, or understanding psychological motivations through observable behavior, became a prominent lens through which to view the causal impact of media violence. This type of research was exemplified by Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll studies demonstrating that children exposed to aggressive behavior, either observed in real life or on film, behaved more aggressively than those in control groups who were not exposed to the behavior. The assumption derived was that children learn through exposure and imitate behavior (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963 ). Though influential, the Bandura experiments were nevertheless heavily criticized. Some argued the laboratory conditions under which children were exposed to media were not generalizable to real-life conditions. Others challenged the assumption that children absorb media content in an unsophisticated manner without being able to distinguish between fantasy and reality. In fact, later studies did find children to be more discerning consumers of media than popularly believed (Gauntlett, 2001 ).

Hugely influential in our understandings of human behavior, the concept of social learning has been at the core of more contemporary understandings of media effects. For example, scholar Christopher Ferguson noted that the General Aggression Model (GAM), rooted in social learning and cognitive theory, has for decades been a dominant model for understanding how media impacts aggression and violence. GAM is described as the idea that “aggression is learned by the activation and repetition of cognitive scripts coupled with the desensitization of emotional responses due to repeated exposure.” However, Ferguson noted that its usefulness has been debated and advocated for a paradigm shift (Ferguson, 2013 , pp. 65, 27; Krahé, 2014 ).

Though the methodologies of the Payne Fund Studies and Bandura studies were heavily criticized, concern over media effects continued to be tied to larger moral debates including the fear of moral decline and concern over the welfare of children. Most notably, in the 1950s, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham warned of the dangers of comic books, a hugely popular medium at the time, and their impact on juveniles. Based on anecdotes and his clinical experience with children, Wertham argued that images of graphic violence and sexual debauchery in comic books were linked to juvenile delinquency. Though he was far from the only critic of comic book content, his criticisms reached the masses and gained further notoriety with the publication of his 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent . Wertham described the comic book content thusly,

The stories have a lot of crime and gunplay and, in addition, alluring advertisements of guns, some of them full-page and in bright colors, with four guns of various sizes and descriptions on a page . . . Here is the repetition of violence and sexiness which no Freud, Krafft-Ebing or Havelock Ellis ever dreamed could be offered to children, and in such profusion . . . I have come to the conclusion that this chronic stimulation, temptation and seduction by comic books, both their content and their alluring advertisements of knives and guns, are contributing factors to many children’s maladjustment. (Wertham, 1954 , p. 39)

Wertham’s work was instrumental in shaping public opinion and policies about the dangers of comic books. Concern about the impact of comics reached its apex in 1954 with the United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. Wertham testified before the committee, arguing that comics were a leading cause of juvenile delinquency. Ultimately, the protest of graphic content in comic books by various interest groups contributed to implementation of the publishers’ self-censorship code, the Comics Code Authority, which essentially designated select books that were deemed “safe” for children (Nyberg, 1998 ). The code remained in place for decades, though it was eventually relaxed and decades later phased out by the two most dominant publishers, DC and Marvel.

Wertham’s work, however influential in impacting the comic industry, was ultimately panned by academics. Although scholar Bart Beaty characterized Wertham’s position as more nuanced, if not progressive, than the mythology that followed him, Wertham was broadly dismissed as a moral reactionary (Beaty, 2005 ; Phillips & Strobl, 2013 ). The most damning criticism of Wertham’s work came decades later, from Carol Tilley’s examination of Wertham’s files. She concluded that in Seduction of the Innocent ,

Wertham manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence—especially that evidence he attributed to personal clinical research with young people—for rhetorical gain. (Tilley, 2012 , p. 386)

Tilley linked Wertham’s approach to that of the Frankfurt theorists who deemed popular culture a social threat and contended that Wertham was most interested in “cultural correction” rather than scientific inquiry (Tilley, 2012 , p. 404).

Over the decades, concern about the moral impact of media remained while theoretical and methodological approaches to media effects studies continued to evolve (Rich, Bickham, & Wartella, 2015 ). In what many consider a sophisticated development, theorists began to view the audience as more active and multifaceted than the mass society perspective allowed (Kitzinger, 2004 ). One perspective, based on a “uses and gratifications” model, assumes that rather than a passive audience being injected with values and information, a more active audience selects and “uses” media as a response to their needs and desires. Studies of uses and gratifications take into account how choice of media is influenced by one’s psychological and social circumstances. In this context, media provides a variety of functions for consumers who may engage with it for the purposes of gathering information, reducing boredom, seeking enjoyment, or facilitating communication (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1973 ; Rubin, 2002 ). This approach differs from earlier views in that it privileges the perspective and agency of the audience.

Another approach, the cultivation theory, gained momentum among researchers in the 1970s and has been of particular interest to criminologists. It focuses on how television television viewing impacts viewers’ attitudes toward social reality. The theory was first introduced by communications scholar George Gerbner, who argued the importance of understanding messages that long-term viewers absorb. Rather than examine the effect of specific content within any given programming, cultivation theory,

looks at exposure to massive flows of messages over long periods of time. The cultivation process takes place in the interaction of the viewer with the message; neither the message nor the viewer are all-powerful. (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, Singnorielli, & Shanahan, 2002 , p. 48)

In other words, he argued, television viewers are, over time, exposed to messages about the way the world works. As Gerbner and colleagues stated, “continued exposure to its messages is likely to reiterate, confirm, and nourish—that is, cultivate—its own values and perspectives” (p. 49).

One of the most well-known consequences of heavy media exposure is what Gerbner termed the “mean world” syndrome. He coined it based on studies that found that long-term exposure to media violence among heavy television viewers, “tends to cultivate the image of a relatively mean and dangerous world” (p. 52). Inherent in Gerbner’s view was that media representations are separate and distinct entities from “real life.” That is, it is the distorted representations of crime and violence that cultivate the notion that the world is a dangerous place. In this context, Gerbner found that heavy television viewers are more likely to be fearful of crime and to overestimate their chances of being a victim of violence (Gerbner, 1994 ).

Though there is evidence in support of cultivation theory, the strength of the relationship between media exposure and fear of crime is inconclusive. This is in part due to the recognition that audience members are not homogenous. Instead, researchers have found that there are many factors that impact the cultivating process. This includes, but is not limited to, “class, race, gender, place of residence, and actual experience of crime” (Reiner, 2002 ; Sparks, 1992 ). Or, as Ted Chiricos and colleagues remarked in their study of crime news and fear of crime, “The issue is not whether media accounts of crime increase fear, but which audiences, with which experiences and interests, construct which meanings from the messages received” (Chiricos, Eschholz, & Gertz, p. 354).

Other researchers found that exposure to media violence creates a desensitizing effect, that is, that as viewers consume more violent media, they become less empathetic as well as psychologically and emotionally numb when confronted with actual violence (Bartholow, Bushman, & Sestir, 2006 ; Carnagey, Anderson, & Bushman, 2007 ; Cline, Croft, & Courrier, 1973 ; Fanti, Vanman, Henrich, & Avraamides, 2009 ; Krahé et al., 2011 ). Other scholars such as Henry Giroux, however, point out that our contemporary culture is awash in violence and “everyone is infected.” From this perspective, the focus is not on certain individuals whose exposure to violent media leads to a desensitization of real-life violence, but rather on the notion that violence so permeates society that it has become normalized in ways that are divorced from ethical and moral implications. Giroux wrote,

While it would be wrong to suggest that the violence that saturates popular culture directly causes violence in the larger society, it is arguable that such violence serves not only to produce an insensitivity to real life violence but also functions to normalize violence as both a source of pleasure and as a practice for addressing social issues. When young people and others begin to believe that a world of extreme violence, vengeance, lawlessness, and revenge is the only world they inhabit, the culture and practice of real-life violence is more difficult to scrutinize, resist, and transform . . . (Giroux, 2015 )

For Giroux, the danger is that the normalization of violence has become a threat to democracy itself. In our culture of mass consumption shaped by neoliberal logics, depoliticized narratives of violence have become desired forms of entertainment and are presented in ways that express tolerance for some forms of violence while delegitimizing other forms of violence. In their book, Disposable Futures , Brad Evans and Henry Giroux argued that as the spectacle of violence perpetuates fear of inevitable catastrophe, it reinforces expansion of police powers, increased militarization and other forms of social control, and ultimately renders marginalized members of the populace disposable (Evans & Giroux, 2015 , p. 81).

Criminology and the “Media/Crime Nexus”

Most criminologists and sociologists who focus on media and crime are generally either dismissive of the notion that media violence directly causes violence or conclude that findings are more complex than traditional media effects models allow, preferring to focus attention on the impact of media violence on society rather than individual behavior (Carrabine, 2008 ; Ferrell, Hayward, & Young, 2015 ; Jewkes, 2015 ; Kitzinger, 2004 ; Marsh & Melville, 2014 ; Rafter, 2006 ; Sternheimer, 2003 ; Sternheimer 2013 ; Surette, 2011 ). Sociologist Karen Sternheimer forcefully declared “media culture is not the root cause of American social problems, not the Big Bad Wolf, as our ongoing public discussion would suggest” (Sternheimer, 2003 , p. 3). Sternheimer rejected the idea that media causes violence and argued that a false connection has been forged between media, popular culture, and violence. Like others critical of a singular focus on media, Sternheimer posited that overemphasis on the perceived dangers of media violence serves as a red herring that directs attention away from the actual causes of violence rooted in factors such as poverty, family violence, abuse, and economic inequalities (Sternheimer, 2003 , 2013 ). Similarly, in her Media and Crime text, Yvonne Jewkes stated that U.K. scholars tend to reject findings of a causal link because the studies are too reductionist; criminal behavior cannot be reduced to a single causal factor such as media consumption. Echoing Gauntlett’s critiques of media effects research, Jewkes stated that simplistic causal assumptions ignore “the wider context of a lifetime of meaning-making” (Jewkes, 2015 , p. 17).

Although they most often reject a “violent media cause violence” relationship, criminologists do not dismiss the notion of media as influential. To the contrary, over the decades much criminological interest has focused on the construction of social problems, the ideological implications of media, and media’s potential impact on crime policies and social control. Eamonn Carrabine noted that the focus of concern is not whether media directly causes violence but on “how the media promote damaging stereotypes of social groups, especially the young, to uphold the status quo” (Carrabine, 2008 , p. 34). Theoretically, these foci have been traced to the influence of cultural and Marxist studies. For example, criminologists frequently focus on how social anxieties and class inequalities impact our understandings of the relationship between media violence and attitudes, values, and behaviors. Influential works in the 1970s, such as Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order by Stuart Hall et al. and Stanley Cohen’s Folk Devils and Moral Panics , shifted criminological critique toward understanding media as a hegemonic force that reinforces state power and social control (Brown, 2011 ; Carrabine, 2008 ; Cohen, 2005 ; Garland, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2013 /1973, 2013/1973 ). Since that time, moral panic has become a common framework applied to public discourse around a variety of social issues including road rage, child abuse, popular music, sex panics, and drug abuse among others.

Into the 21st century , advances in technology, including increased use of social media, shifted the ways that criminologists approach the study of media effects. Scholar Sheila Brown traced how research in criminology evolved from a focus on “media and crime” to what she calls the “media/crime nexus” that recognizes that “media experience is real experience” (Brown, 2011 , p. 413). In other words, many criminologists began to reject as fallacy what social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson deemed “digital dualism,” or the notion that we have an “online” existence that is separate and distinct from our “off-line” existence. Instead, we exist simultaneously both online and offline, an

augmented reality that exists at the intersection of materiality and information, physicality and digitality, bodies and technology, atoms and bits, the off and the online. It is wrong to say “IRL” [in real life] to mean offline: Facebook is real life. (Jurgenson, 2012 )

The changing media landscape has been of particular interest to cultural criminologists. Michelle Brown recognized the omnipresence of media as significant in terms of methodological preferences and urged a move away from a focus on causality and predictability toward a more fluid approach that embraces the complex, contemporary media-saturated social reality characterized by uncertainty and instability (Brown, 2007 ).

Cultural criminologists have indeed rejected direct, causal relationships in favor of the recognition that social meanings of aggression and violence are constantly in transition, flowing through the media landscape, where “bits of information reverberate and bend back on themselves, creating a fluid porosity of meaning that defines late-modern life, and the nature of crime and media within it.” In other words, there is no linear relationship between crime and its representation. Instead, crime is viewed as inseparable from the culture in which our everyday lives are constantly re-created in loops and spirals that “amplify, distort, and define the experience of crime and criminality itself” (Ferrell, Hayward, & Young, 2015 , pp. 154–155). As an example of this shift in understanding media effects, criminologist Majid Yar proposed that we consider how the transition from being primarily consumers to primarily producers of content may serve as a motivating mechanism for criminal behavior. Here, Yar is suggesting that the proliferation of user-generated content via media technologies such as social media (i.e., the desire “to be seen” and to manage self-presentation) has a criminogenic component worthy of criminological inquiry (Yar, 2012 ). Shifting attention toward the media/crime nexus and away from traditional media effects analyses opens possibilities for a deeper understanding of the ways that media remains an integral part of our everyday lives and inseparable from our understandings of and engagement with crime and violence.

Over the years, from films to comic books to television to video games to social media, concerns over media effects have shifted along with changing technologies. While there seems to be some consensus that exposure to violent media impacts aggression, there is little evidence showing its impact on violent or criminal behavior. Nonetheless, high-profile violent crimes continue to reignite public interest in media effects, particularly with regard to copycat crimes.

At times, academic debate around media effects remains contentious and one’s academic discipline informs the study and interpretation of media effects. Criminologists and sociologists are generally reluctant to attribute violence and criminal behavior directly to exposure to violence media. They are, however, not dismissive of the impact of media on attitudes, social policies, and social control as evidenced by the myriad of studies on moral panics and other research that addresses the relationship between media, social anxieties, gender, race, and class inequalities. Scholars who study media effects are also sensitive to the historical context of the debates and ways that moral concerns shape public policies. The self-regulating codes of the film industry and the comic book industry have led scholars to be wary of hyperbole and policy overreach in response to claims of media effects. Future research will continue to explore ways that changing technologies, including increasing use of social media, will impact our understandings and perceptions of crime as well as criminal behavior.

Further Reading

- American Psychological Association . (2015). Resolution on violent video games . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/violent-video-games.aspx

- Anderson, J. A. , & Grimes, T. (2008). Special issue: Media violence. Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1059–1060.

- Berlatsky, N. (Ed.). (2012). Media violence: Opposing viewpoints . Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven.

- Elson, M. , & Ferguson, C. J. (2014). Twenty-five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 33–46.

- Ferguson, C. (Ed.). (2015). Special issue: Video games and youth. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4).

- Ferguson, C. J. , Olson, C. K. , Kutner, L. A. , & Warner, D. E. (2014). Violent video games, catharsis seeking, bullying, and delinquency: A multivariate analysis of effects. Crime & Delinquency , 60 (5), 764–784.

- Gentile, D. (2013). Catharsis and media violence: A conceptual analysis. Societies , 3 (4), 491–510.

- Huesmann, L. R. (2007). The impact of electronic media violence: Scientific theory and research. Journal of Adolescent Health , 41 (6), S6–S13.

- Huesmann, L. R. , & Taylor, L. D. (2006). The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annual Review of Public Health , 27 (1), 393–415.

- Krahé, B. (Ed.). (2013). Special issue: Understanding media violence effects. Societies , 3 (3).

- Media Violence Commission, International Society for Research on Aggression (ISRA) . (2012). Report of the Media Violence Commission. Aggressive Behavior , 38 (5), 335–341.

- Rich, M. , & Bickham, D. (Eds.). (2015). Special issue: Methodological advances in the field of media influences on children. Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1731–1735.

- American Psychological Association (APA) . (2015, August 13). APA review confirms link between playing violent video games and aggression . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2015/08/violent-video-games.aspx

- Anderson, J. A. (2008). The production of media violence and aggression research: A cultural analysis. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1260–1279.

- Bandura, A. , Ross, D. , & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 66 (1), 3–11.

- Barker, M. , & Petley, J. (2001). Ill effects: The media violence debate (2d ed.). London: Routledge.

- Bartholow, B. D. , Bushman, B. J. , & Sestir, M. A. (2006). Chronic violent video game exposure and desensitization to violence: Behavioral and event-related brain potential data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 42 (4), 532–539.

- Beaty, B. (2005). Fredric Wertham and the critique of mass culture . Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Bracci, P. (2010, March 12). The police were sure James Bulger’s ten-year-old killers were simply wicked. But should their parents have been in the dock? Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1257614/The-police-sure-James-Bulgers-year-old-killers-simply-wicked-But-parents-dock.html

- Breuer, J. , Vogelgesang, J. , Quandt, T. , & Festl, R. (2015). Violent video games and physical aggression: Evidence for a selection effect among adolescents. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 305–328.

- Brooks, X. (2002, December 19). Natural born copycats . Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/dec/20/artsfeatures1

- Brown, M. (2007). Beyond the requisites: Alternative starting points in the study of media effects and youth violence. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture , 14 (1), 1–20.

- Brown, S. (2011). Media/crime/millennium: Where are we now? A reflective review of research and theory directions in the 21st century. Sociology Compass , 5 (6), 413–425.

- Bushman, B. (2016, July 26). Violent video games and real violence: There’s a link but it’s not so simple . Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/violent-video-games-and-real-violence-theres-a-link-but-its-not-so-simple?63038

- Bushman, B. J. , & Anderson, C. A. (2015). Understanding causality in the effects of media violence. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1807–1821.

- Bushman, B. J. , Jamieson, P. E. , Weitz, I. , & Romer, D. (2013). Gun violence trends in movies. Pediatrics , 132 (6), 1014–1018.

- Carnagey, N. L. , Anderson, C. A. , & Bushman, B. J. (2007). The effect of video game violence on physiological desensitization to real-life violence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 43 (3), 489–496.

- Carrabine, E. (2008). Crime, culture and the media . Cambridge, U.K.: Polity.

- Chiricos, T. , Eschholz, S. , & Gertz, M. (1997). Crime, news and fear of crime: Toward an identification of audience effects. Social Problems , 44 , 342.

- Cline, V. B. , Croft, R. G. , & Courrier, S. (1973). Desensitization of children to television violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 27 (3), 360–365.

- CNN Wire (2016, July 24). Officials: 18-year-old suspect in Munich attack was obsessed with mass shootings . Retrieved from http://ktla.com/2016/07/24/18-year-old-suspect-in-munich-shooting-played-violent-video-games-had-mental-illness-officials/

- Cohen, S. (2005). Folk devils and moral panics (3d ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Cullen, D. (2009). Columbine . New York: Hachette.

- Dahl, G. , & DellaVigna, S. (2012). Does movie violence increase violent crime? In N. Berlatsky (Ed.), Media Violence: Opposing Viewpoints (pp. 36–43). Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven.

- DeCamp, W. (2015). Impersonal agencies of communication: Comparing the effects of video games and other risk factors on violence. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 296–304.

- Elson, M. , & Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Does doing media violence research make one aggressive? European Psychologist , 19 (1), 68–75.

- Evans, B. , & Giroux, H. (2015). Disposable futures: The seduction of violence in the age of spectacle . San Francisco: City Lights Publishers.

- Fanti, K. A. , Vanman, E. , Henrich, C. C. , & Avraamides, M. N. (2009). Desensitization to media violence over a short period of time. Aggressive Behavior , 35 (2), 179–187.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Violent video games and the Supreme Court: Lessons for the scientific community in the wake of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association. American Psychologist , 68 (2), 57–74.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2014). Does media violence predict societal violence? It depends on what you look at and when. Journal of Communication , 65 (1), E1–E22.

- Ferguson, C. J. , & Dyck, D. (2012). Paradigm change in aggression research: The time has come to retire the general aggression model. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 17 (3), 220–228.

- Ferguson, C. J. , & Konijn, E. A. (2015). She said/he said: A peaceful debate on video game violence. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 397–411.

- Ferrell, J. , Hayward, K. , & Young, J. (2015). Cultural criminology: An invitation . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Frosch, D. , & Johnson, K. (2012, July 20). 12 are killed at showing of Batman movie in Colorado . Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/21/us/shooting-at-colorado-theater-showing-batman-movie.html

- Garland, D. (2008). On the concept of moral panic. Crime, Media, Culture , 4 (1), 9–30.

- Gauntlett, D. (2001). The worrying influence of “media effects” studies. In ill effects: The media violence debate (2d ed.). London: Routledge.

- Gerbner, G. (1994). TV violence and the art of asking the wrong question. Retrieved from http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/tv-violence-and-art-asking-wrong-question

- Gerbner, G. , Gross, L. , Morgan, M. , Singnorielli, N. , & Shanahan, J. (2002). Growing up with television: Cultivation process. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 43–67). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Giroux, H. (2015, December 25). America’s addiction to violence . Retrieved from http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/12/25/americas-addiction-to-violence-2/

- Graham, C. , & Gallagher, I. (2012, July 20). Gunman who massacred 12 at movie premiere used same drugs that killed Batman star Heath Ledger . Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2176377/James-Holmes-Colorado-shooting-Gunman-used-drugs-killed-Heath-Ledger.html

- Gunter, B. (2008). Media violence: Is there a case for causality? American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1061–1122.

- Hall, S. , Critcher, C. , Jefferson, T. , Clarke, J. , & Roberts, B. (2013/1973). Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order . Hampshire, U.K.: Palgrave.

- Helfgott, J. B. (2015). Criminal behavior and the copycat effect: Literature review and theoretical framework for empirical investigation. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 22 (C), 46–64.

- Hetsroni, A. (2007). Four decades of violent content on prime-time network programming: A longitudinal meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication , 57 (4), 759–784.

- Jewkes, Y. (2015). Media & crime . London: SAGE.

- Jowett, G. , Jarvie, I. , & Fuller, K. (1996). Children and the movies: Media influence and the Payne Fund controversy . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Jurgenson, N. (2012, June 28). The IRL fetish . Retrieved from http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-irl-fetish/

- Katz, E. , Blumler, J. G. , & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly .

- Kitzinger, J. (2004). Framing abuse: Media influence and public understanding of sexual violence against children . London: Polity.

- Krahé, B. (2014). Restoring the spirit of fair play in the debate about violent video games. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 56–59.

- Krahé, B. , Möller, I. , Huesmann, L. R. , Kirwil, L. , Felber, J. , & Berger, A. (2011). Desensitization to media violence: Links with habitual media violence exposure, aggressive cognitions, and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 100 (4), 630–646.

- Markey, P. M. , French, J. E. , & Markey, C. N. (2015). Violent movies and severe acts of violence: Sensationalism versus science. Human Communication Research , 41 (2), 155–173.

- Markey, P. M. , Markey, C. N. , & French, J. E. (2015). Violent video games and real-world violence: Rhetoric versus data. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 4 (4), 277–295.

- Marsh, I. , & Melville, G. (2014). Crime, justice and the media . New York: Routledge.

- McShane, L. (2012, July 27). Maryland police arrest possible Aurora copycat . Retrieved from http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/maryland-cops-thwart-aurora-theater-shooting-copycat-discover-gun-stash-included-20-weapons-400-rounds-ammo-article-1.1123265

- Meyer, J. (2015, September 18). The James Holmes “Joker” rumor . Retrieved from http://www.denverpost.com/2015/09/18/meyer-the-james-holmes-joker-rumor/

- Murray, J. P. (2008). Media violence: The effects are both real and strong. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1212–1230.

- Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the comics code. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- PBS . (n.d.). Culture shock: Flashpoints: Theater, film, and video: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/cultureshock/flashpoints/theater/clockworkorange.html

- Phillips, N. D. , & Strobl, S. (2013). Comic book crime: Truth, justice, and the American way . New York: New York University Press.

- Rafter, N. (2006). Shots in the mirror: Crime films and society (2d ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reiner, R. (2002). Media made criminality: The representation of crime in the mass media. In R. Reiner , M. Maguire , & R. Morgan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminology (pp. 302–340). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reuters . (2016, July 24). Munich gunman, a fan of violent video games, rampage killers, had planned attack for a year . Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2016/07/24/munich-gunman-a-fan-of-violent-video-games-rampage-killers-had-planned-attack-for-a-year.html

- Rich, M. , Bickham, D. S. , & Wartella, E. (2015). Methodological advances in the field of media influences on children. American Behavioral Scientist , 59 (14), 1731–1735.

- Robinson, M. B. (2011). Media coverage of crime and criminal justice. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Rubin, A. (2002). The uses-and-gratifications perspective of media effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 525–548). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Savage, J. (2008). The role of exposure to media violence in the etiology of violent behavior: A criminologist weighs in. American Behavioral Scientist , 51 (8), 1123–1136.

- Savage, J. , & Yancey, C. (2008). The effects of media violence exposure on criminal aggression: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior , 35 (6), 772–791.

- Sparks, R. (1992). Television and the drama of crime: Moral tales and the place of crime in public life . Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press.

- Sparks, G. , & Sparks, C. (2002). Effects of media violence. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (2d ed., pp. 269–286). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sternheimer, K. (2003). It’s not the media: The truth about pop culture’s influence on children . Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Sternheimer, K. (2013). Connecting social problems and popular culture: Why media is not the answer (2d ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Strasburger, V. C. , & Donnerstein, E. (2014). The new media of violent video games: Yet same old media problems? Clinical Pediatrics , 53 (8), 721–725.

- Surette, R. (2002). Self-reported copycat crime among a population of serious and violent juvenile offenders. Crime & Delinquency , 48 (1), 46–69.

- Surette, R. (2011). Media, crime, and criminal justice: Images, realities and policies (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Surette, R. (2016). Measuring copycat crime. Crime, Media, Culture , 12 (1), 37–64.

- Tilley, C. L. (2012). Seducing the innocent: Fredric Wertham and the falsifications that helped condemn comics. Information & Culture , 47 (4), 383–413.

- Warburton, W. (2014). Apples, oranges, and the burden of proof—putting media violence findings into context. European Psychologist , 19 (1), 60–67.

- Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the innocent . New York: Rinehart.

- Yamato, J. (2016, June 14). Gaming industry mourns Orlando victims at E3—and sees no link between video games and gun violence . Retrieved from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/14/gamers-mourn-orlando-victims-at-e3-and-see-no-link-between-gaming-and-gun-violence.html

- Yar, M. (2012). Crime, media and the will-to-representation: Reconsidering relationships in the new media age. Crime, Media, Culture , 8 (3), 245–260.

Related Articles

- Intimate Partner Violence

- The Extent and Nature of Gang Crime

- Intersecting Dimensions of Violence, Abuse, and Victimization

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Criminology and Criminal Justice. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 23 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

Character limit 500 /500

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Impact of Electronic Media Violence: Scientific Theory and Research

L. rowell huesmann.

The University of Michigan

Since the early 1960s research evidence has been accumulating that suggests that exposure to violence in television, movies, video games, cell phones, and on the internet increases the risk of violent behavior on the viewer’s part just as growing up in an environment filled with real violence increases the risk of them behaving violently. In the current review this research evidence is critically assessed, and the psychological theory that explains why exposure to violence has detrimental effects for both the short run and long run is elaborated. Finally, the size of the “media violence effect” is compared with some other well known threats to society to estimate how important a threat it should be considered.

One of the notable changes in our social environment in the 20 th and 21st centuries has been the saturation of our culture and daily lives by the mass media. In this new environment radio, television, movies, videos, video games, cell phones, and computer networks have assumed central roles in our children’s daily lives. For better or worse the mass media are having an enormous impact on our children’s values, beliefs, and behaviors. Unfortunately, the consequences of one particular common element of the electronic mass media has a particularly detrimental effect on children’s well being. Research evidence has accumulated over the past half-century that exposure to violence on television, movies, and most recently in video games increases the risk of violent behavior on the viewer’s part just as growing up in an environment filled with real violence increases the risk of violent behavior. Correspondingly, the recent increase in the use of mobile phones, text messaging, e-mail, and chat rooms by our youth have opened new venues for social interaction in which aggression can occur and youth can be victimized – new venues that break the old boundaries of family, neighborhood, and community that might have protected our youth to some extent in the past. These globe spanning electronic communication media have not really introduced new psychological threats to our children, but they have made it much harder to protect youth from the threats and have exposed many more of them to threats that only a few might have experienced before. It is now not just kids in bad neighborhoods or with bad friends who are likely to be exposed to bad things when they go out on the street. A ‘virtual’ bad street is easily available to most youth now. However, our response should not be to panic and keep our children “indoors” because the “streets” out there are dangerous. The streets also provide wonderful experiences and help youth become the kinds of adults we desire. Rather our response should be to understand the dangers on the streets, to help our children understand and avoid the dangers, to avoid exaggerating the dangers which will destroy our credibility, and also to try to control exposure to the extent we can.

Background for the Review

Different people may have quite different things in mind when they think of media violence. Similarly, among the public there may be little consensus on what constitutes aggressive and violent behavior . Most researchers, however, have clear conceptions of what they mean by media violence and aggressive behavior.

Most researchers define media violence as visual portrayals of acts of physical aggression by one human or human-like character against another. This definition has evolved as theories about the effects of media violence have evolved and represents an attempt to describe the kind of violent media presentation that is most likely to teach the viewer to be more violent. Movies depicting violence of this type were frequent 75 years ago and are even more frequent today, e.g., M, The Maltese Falcon, Shane, Dirty Harry, Pulp Fiction, Natural Born Killers, Kill Bill . Violent TV programs became common shortly after TV became common in American homes about 55 years ago and are common today, e.g., Gunsmoke, Miami Vice, CSI, and 24. More recently, video games, internet displays, and cell phone displays have become part of most children’s growing-up, and violent displays have become common on them, e.g., Grand Theft Auto, Resident Evil, Warrior .

To most researchers, aggressive behavior refers to an act that is intended to injure or irritate another person. Laymen may call assertive salesmen “aggressive,” but researchers do not because there is no intent to harm. Aggression can be physical or non-physical. It includes many kinds of behavior that do not seem to fit the commonly understood meaning of “violence.” Insults and spreading harmful rumors fit the definition. Of course, the aggressive behaviors of greatest concern clearly involve physical aggression ranging in severity from pushing or shoving, to fighting, to serious assaults and homicide. In this review he term violent behavior is used to describe these more serious forms of physical aggression that have a significant risk of seriously injuring the victim.

Violent or aggressive actions seldom result from a single cause; rather, multiple factors converging over time contribute to such behavior. Accordingly, the influence of the violent mass media is best viewed as one of the many potential factors that influence the risk for violence and aggression. No reputable researcher is suggesting that media violence is “the” cause of violent behavior. Furthermore, a developmental perspective is essential for an adequate understanding of how media violence affects youthful conduct and in order to formulate a coherent response to this problem. Most youth who are aggressive and engage in some forms of antisocial behavior do not go on to become violent teens and adults [ 1 ]. Still, research has shown that a significant proportion of aggressive children are likely to grow up to be aggressive adults, and that seriously violent adolescents and adults often were highly aggressive and even violent as children [ 2 ]. The best single predictor of violent behavior in older adolescents, young adults, and even middle aged adults is aggressive behavior when they were younger. Thus, anything that promotes aggressive behavior in young children statistically is a risk factor for violent behavior in adults as well.

Theoretical Explanations for Media Violence Effects

In order to understand the empirical research implicating violence in electronic media as a threat to society, an understanding of why and how violent media cause aggression is vital. In fact, psychological theories that explain why media violence is such a threat are now well established. Furthermore, these theories also explain why the observation of violence in the real world – among the family, among peers, and within the community – also stimulates aggressive behavior in the observer.

Somewhat different processes seem to cause short term effects of violent content and long term effects of violent content, and that both of these processes are distinct from the time displacement effects that engagement in media may have on children. Time displacement effects refer to the role of the mass media (including video games) in displacing other activities in which the child might engage which might change the risk for certain kinds of behavior, e.g. replacing reading, athletics, etc. This essay is focusing on the effects of violent media content, and displacement effects will not be reviewed though they may well have important consequences.

Short-term Effects

Most theorists would now agree that the short term effects of exposure to media violence are mostly due to 1) priming processes, 2) arousal processes, and 3) the immediate mimicking of specific behaviors [ 3 , 4 ].

Priming is the process through which spreading activation in the brain’s neural network from the locus representing an external observed stimulus excites another brain node representing a cognition, emotion, or behavior. The external stimulus can be inherently linked to a cognition, e.g., the sight of a gun is inherently linked to the concept of aggression [ 5 ], or the external stimulus can be something inherently neutral like a particular ethnic group (e.g., African-American) that has become linked in the past to certain beliefs or behaviors (e.g., welfare). The primed concepts make behaviors linked to them more likely. When media violence primes aggressive concepts, aggression is more likely.

To the extent that mass media presentations arouse the observer, aggressive behavior may also become more likely in the short run for two possible reasons -- excitation transfer [ 6 ] and general arousal [ 7 ]. First, a subsequent stimulus that arouses an emotion (e.g. a provocation arousing anger) may be perceived as more severe than it is because some of the emotional response stimulated by the media presentation is miss-attributed as due to the provocation transfer. For example, immediately following an exciting media presentation, such excitation transfer could cause more aggressive responses to provocation. Alternatively, the increased general arousal stimulated by the media presentation may simply reach such a peak that inhibition of inappropriate responses is diminished, and dominant learned responses are displayed in social problem solving, e.g. direct instrumental aggression.

The third short term process, imitation of specific behaviors, can be viewed as a special case of the more general long-term process of observational learning [ 8 ]. In recent years evidence has accumulated that human and primate young have an innate tendency to mimic whomever they observe [ 9 ]. Observation of specific social behaviors around them increases the likelihood of children behaving exactly that way. Specifically, as children observe violent behavior, they are prone to mimic it. The neurological process through which this happens is not completely understood, but it seems likely that “mirror neurons,” which fire when either a behavior is observed or when the same behavior is acted out, play an important role [ 10 , 4 ].

Long-term Effects

Long term content effects, on the other hand, seem to be due to 1) more lasting observational learning of cognitions and behaviors (i.e., imitation of behaviors), and 2) activation and desensitization of emotional processes.

Observational learning

According to widely accepted social cognitive models, a person’s social behavior is controlled to a great extent by the interplay of the current situation with the person’s emotional state, their schemas about the world, their normative beliefs about what is appropriate, and the scripts for social behavior that they have learned [ 11 ]. During early, middle, and late childhood children encode in memory social scripts to guide behavior though observation of family, peers, community, and mass media. Consequently observed behaviors are imitated long after they are observed [ 10 ]. During this period, children’s social cognitive schemas about the world around them also are elaborated. For example, extensive observation of violence has been shown to bias children’s world schemas toward attributing hostility to others’ actions. Such attributions in turn increase the likelihood of children behaving aggressively [ 12 ]. As children mature further, normative beliefs about what social behaviors are appropriate become crystallized and begin to act as filters to limit inappropriate social behaviors [ 13 ]. These normative beliefs are influenced in part by children’s observation of the behaviors of those around them including those observed in the mass media.

Desensitization

Long-term socialization effects of the mass media are also quite likely increased by the way the mass media and video games affect emotions. Repeated exposures to emotionally activating media or video games can lead to habituation of certain natural emotional reactions. This process is called “desensitization.” Negative emotions experienced automatically by viewers in response to a particular violent or gory scene decline in intensity after many exposures [ 4 ]. For example, increased heart rates, perspiration, and self-reports of discomfort often accompany exposure to blood and gore. However, with repeated exposures, this negative emotional response habituates, and the child becomes “desensitized.” The child can then think about and plan proactive aggressive acts without experiencing negative affect [ 4 ].

Enactive learning

One more theoretical point is important. Observational learning and desensitization do not occur independently of other learning processes. Children are constantly being conditioned and reinforced to behave in certain ways, and this learning may occur during media interactions. For example, because players of violent video games are not just observers but also “active” participants in violent actions, and are generally reinforced for using violence to gain desired goals, the effects on stimulating long-term increases in violent behavior should be even greater for video games than for TV, movies, or internet displays of violence. At the same time, because some video games are played together by social groups (e.g., multi-person games) and because individual games may often be played together by peers, more complex social conditioning processes may be involved that have not yet been empirically examined. These effects, including effects of selection and involvement, need to be explored.

The Key Empirical Studies

Given this theoretical back ground, let us now examine the empirical research that indicates that childhood exposure to media violence has both short term and long term effects in stimulating aggression and violence in the viewer. Most of this research is on TV, movies, and video games, but from the theory above one can see that the same effects should occur for violence portrayed on various internet sites (e.g., multi-person game sites, video posting sites, chat rooms) and on handheld cell phones or computers.

Violence in Television, Films, and Video Games

The fact that most research on the impact of media violence on aggressive behavior has focused on violence in fictional television and film and video games is not surprising given the prominence of violent content in these media and the prominence of these media in children’s lives.

Children in the United States spend an average of between three and four hours per day viewing television [ 14 ], and the best studies have shown that over 60% of programs contain some violence, and about 40% of those contain heavy violence [ 15 ]. Children are also spending an increasingly large amount of time playing video games, most of which contain violence. Video game units are now present in 83% of homes with children [ 16 ]. In 2004, children spent 49 minutes per day playing video, and on any given day, 52% of children ages 8–18 years play a video game games [ 16 ]. Video game use peaks during middle childhood with an average of 65 minutes per day for 8–10 year-olds, and declines to 33 minutes per day for 15–18 year-olds [ 16 ]. And most of these games are violent; 94% of games rated (by the video game industry) as appropriate for teens are described as containing violence, and ratings by independent researchers suggest that the real percentage may be even higher [ 17 ]. No published study has quantified the violence in games rated ‘M’ for mature—presumably, these are even more likely to be violent.

Meta-analyses that average the effects observed in many studies provide the best overall estimates of the effects of media violence. Two particularly notable meta-analyses are those of Paik and Comstock [ 18 ] and Anderson and Bushman [ 19 ]. The Paik and Comstock meta-analysis focused on violent TV and films while the Anderson and Bushman meta-analysis focused on violent video games.

Paik and Comstock [ 18 ] examined effect sizes from 217 studies published between 1957 and 1990. For the randomized experiments they reviewed, Paik and Comstock found an average effect size ( r =.38, N=432 independent tests of hypotheses) which is moderate to large compared to other public health effects. When the analysis was limited to experiments on physical violence against a person, the average r was still .32 (N=71 independent tests). This meta-analysis also examined cross-sectional and longitudinal field surveys published between 1957 and 1990. For these studies the authors found an average r of .19 (N=410 independent tests). When only studies were used for which the dependent measure was actual physical aggression against another person (N=200), the effect size remained unchanged. Finally, the average correlation of media violence exposure with engaging in criminal violence was .13.

Anderson and Bushman [ 19 ] conducted the key meta-analyses on the effects of violent video games. Their meta-analyses revealed effect sizes for violent video games ranging from .15 to .30. Specifically, playing violent video games was related to increases in aggressive behavior ( r = .27), aggressive affect ( r =.19), aggressive cognitions (i.e., aggressive thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes), ( r =.27), and physiological arousal ( r = .22) and was related to decreases in prosocial (helping) behavior ( r = −.27). Furthermore, when studies were coded for the quality of their methodology, the best studies yielded larger effect sizes than the “not-best” studies.