- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

7 Major Environmental Movements in India

Last updated on May 22, 2021 by ClearIAS Team

Contemporary India experiences almost unrestricted exploitation of resources because of the lure of new consumerist lifestyles.

The balance of nature is disrupted. This has led to many conflicts in society.

In this article, we discuss the major environmental movements in India.

Table of Contents

What is an Environmental Movement?

- An environmental movement can be defined as a social or political movement, for the conservation of the environment or for the improvement of the state of the environment . The terms ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement’ are alternatively used to denote the same.

- The environmental movements favour the sustainable management of natural resources. The movements often stress the protection of the environment via changes in public policy . Many movements are centred on ecology, health and human rights .

- Environmental movements range from the highly organized and formally institutionalized ones to the radically informal activities.

- The spatial scope of various environmental movements ranges from being local to almost global.

Major Environmental Movements in India

Some of the major environmental movements in India during the period 1700 to 2000 are the following.

1.Bishnoi Movement

Join Now: UPSC Prelims cum Mains Course

- Year: 1700s

- Place: Khejarli, Marwar region, Rajasthan state.

- Leaders: Amrita Devi along with Bishnoi villagers in Khejarli and surrounding villages.

- Aim: Save sacred trees from being cut down by the king’s soldiers for a new palace.

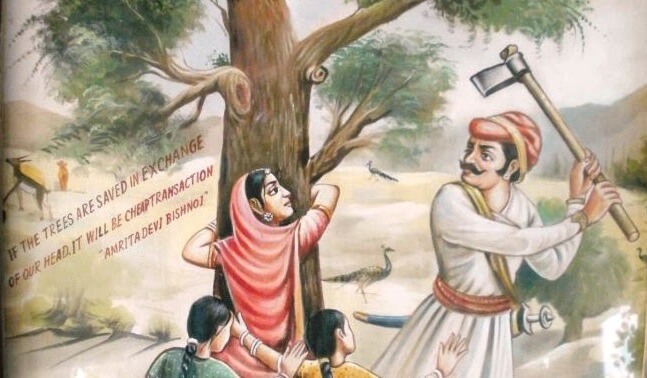

What was it all about : Amrita Devi, a female villager could not bear to witness the destruction of both her faith and the village’s sacred trees. She hugged the trees and encouraged others to do the same. 363 Bishnoi villagers were killed in this movement.

The Bishnoi tree martyrs were influenced by the teachings of Guru Maharaj Jambaji, who founded the Bishnoi faith in 1485 and set forth principles forbidding harm to trees and animals. The king who came to know about these events rushed to the village and apologized, ordering the soldiers to cease logging operations. Soon afterwards, the maharajah designated the Bishnoi state as a protected area, forbidding harm to trees and animals. This legislation still exists today in the region.

2. Chipko Movement

- Place: In Chamoli district and later at Tehri-Garhwal district of Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Govind Singh Rawat, Dhoom Singh Negi, Shamsher Singh Bisht and Ghanasyam Raturi.

- Aim: The main objective was to protect the trees on the Himalayan slopes from the axes of contractors of the forest.

What was it all about : Mr. Bahuguna enlightened the villagers by conveying the importance of trees in the environment which checks the erosion of soil, cause rains and provides pure air. The women of Advani village of Tehri-Garhwal tied the sacred thread around trunks of trees and they hugged the trees, hence it was called the ‘Chipko Movement’ or ‘hug the tree movement’.

The main demand of the people in these protests was that the benefits of the forests (especially the right to fodder) should go to local people. The Chipko movement gathered momentum in 1978 when the women faced police firings and other tortures.

Join Now: CSAT Course

The then state Chief Minister, Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna set up a committee to look into the matter, which eventually ruled in favour of the villagers. This became a turning point in the history of eco-development struggles in the region and around the world.

3. Save Silent Valley Movement

- Place: Silent Valley, an evergreen tropical forest in the Palakkad district of Kerala, India.

- Leaders: The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) an NGO, and the poet-activist Sughathakumari played an important role in the Silent Valley protests.

- Aim: In order to protect the Silent Valley, the moist evergreen forest from being destroyed by a hydroelectric project.

What was it all about: The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) proposed a hydroelectric dam across the Kunthipuzha River that runs through Silent Valley. In February 1973, the Planning Commission approved the project at a cost of about Rs 25 crores. Many feared that the project would submerge 8.3 sq km of untouched moist evergreen forest. Several NGOs strongly opposed the project and urged the government to abandon it.

In January 1981, bowing to unrelenting public pressure, Indira Gandhi declared that Silent Valley will be protected. In June 1983 the Center re-examined the issue through a commission chaired by Prof. M.G.K. Menon. In November 1983 the Silent Valley Hydroelectric Project was called off. In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi formally inaugurated the Silent Valley National Park.

4. Jungle Bachao Andholan

Join Now: UPSC Prelims Test Series

- Place: Singhbhum district of Bihar

- Leaders: The tribals of Singhbhum.

- Aim: Against governments decision to replace the natural sal forest with Teak .

What was it all about: The tribals of the Singhbhum district of Bihar started the protest when the government decided to replace the natural sal forests with the highly-priced teak. This move was called by many “Greed Game Political Populism”. Later this movement spread to Jharkhand and Orissa.

5. Appiko Movement

- Place: Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka State

- Leaders: Appiko’s greatest strengths lie in it being neither driven by a personality nor having been formally institutionalised. However, it does have a facilitator in Pandurang Hegde. He helped launch the movement in 1983.

- Aim: Against the felling and commercialization of natural forest and the ruin of ancient livelihood.

What was it all about: It can be said that the Appiko movement is the southern version of the Chipko movement. The Appiko Movement was locally known as “Appiko Chaluvali”. The locals embraced the trees which were to be cut by contractors of the forest department. The Appiko movement used various techniques to raise awareness such as foot marches in the interior forest, slide shows, folk dances, street plays etc.

The second area of the movement’s work was to promote afforestation on denuded lands. The movement later focused on the rational use of the ecosphere by introducing alternative energy resource to reduce pressure on the forest. The movement became a success. The current status of the project is – stopped.

6. Narmada Bachao Andholan (NBA)

- Place: Narmada River, which flows through the states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

- Leaders: Medha Patker, Baba Amte, Adivasis, farmers, environmentalists and human rights activists.

- Aim: A social movement against a number of large dams being built across the Narmada River.

What was it all about: The movement first started as a protest for not providing proper rehabilitation and resettlement for the people who have been displaced by the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Later on, the movement turned its focus on the preservation of the environment and the eco-systems of the valley. Activists also demanded the height of the dam to be reduced to 88 m from the proposed height of 130m. World Bank withdrew from the project.

The environmental issue was taken into court. In October 2000, the Supreme Court gave a judgment approving the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam with a condition that the height of the dam could be raised to 90 m. This height is much higher than the 88 m which anti-dam activists demanded, but it is definitely lower than the proposed height of 130 m. The project is now largely financed by the state governments and market borrowings. The project is expected to be fully completed by 2025.

Although not successful, as the dam could not be prevented, the NBA has created an anti-big dam opinion in India and outside. It questioned the paradigm of development. As a democratic movement, it followed the Gandhian way 100 per cent.

7. Tehri Dam Conflict

- Year: 1990’s

- Place: Bhagirathi River near Tehri in Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna

- Aim: The protest was against the displacement of town inhabitants and the environmental consequence of the weak ecosystem.

Tehri dam attracted national attention in the 1980s and the 1990s. The major objections include seismic sensitivity of the region, submergence of forest areas along with Tehri town etc. Despite the support from other prominent leaders like Sunderlal Bahuguna, the movement has failed to gather enough popular support at the national as well as international levels.

- Appiko – The Hindu

- NBA – The Hindu

Article by: Priyanka Sunil

Take a Test: Analyse Your Progress

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

October 16, 2016 at 12:08 am

V.v.useful info.thank u so much sir

March 20, 2017 at 3:47 pm

Happy to help

October 16, 2016 at 4:53 pm

Thank you very much clearias.com .

October 18, 2016 at 10:43 pm

Tq very much to clear IAS team Wonder ful information In brief way

June 8, 2018 at 5:57 pm

Ty very much. It was really very helpful to me

October 24, 2016 at 2:47 pm

It is a very important issue for mains.Thank you clear IAS team.

November 26, 2016 at 3:05 pm

Hi, You are providing valuable information for competitive exam’s. Here in this article you have written about “Chipko Movement” is started from Tehri Garhwal. “Chipko Movement” was started from “Reni Village” of Chamoli ditrtict, which is near “Joshimath”.

So, plz correct that.

November 26, 2016 at 4:18 pm

Thanks Udit for pointing it out. We have updated the article.

The struggle Chipko’s first battle took place in early 1973 in Chamoli district, when the villagers of Mandal, led by Bhatt and the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM), prevented the Allahabad-based sports goods company, Symonds, from felling 14 ash trees. In Tehri Garhwal, Chipko activists led by Sunderlal Bahuguna began organising villagers from May 1977 to oppose tree-felling in the Henwal valley.

February 2, 2017 at 11:26 pm

Very Nice Sir.

July 19, 2017 at 3:34 pm

Nice ,I came to know about few things today

December 20, 2020 at 2:12 pm

Thanku sir for explaination. It really helps me

November 9, 2017 at 11:17 am

Thank you so much it helped me to do my project

November 15, 2017 at 10:47 pm

very nice information sir

November 24, 2017 at 9:40 pm

Thank you so much. Keep it up👍!

January 19, 2018 at 4:43 pm

Thank you so much You helped me project😄👍

February 28, 2018 at 7:47 am

Hello sir my name pratap I live in jajpur,odisha . One request sir in jajpur tha environment is polluted because here 17 factory are avelebul .Sir my request is save our children ….Plz sir

April 26, 2018 at 6:44 pm

Thnq for the info sir ! This is quite interesting Nd also helpful for my xam tomorrow

May 2, 2018 at 7:58 pm

Good information. Sir. I. Gained some knowledge from this

August 18, 2023 at 8:01 pm

Thank you so much for giving such a important information

May 25, 2018 at 5:13 pm

Do you have youtube channel. As the information provided by you is awesome.

May 25, 2018 at 8:11 pm

Yes. We have @clearias. You can find the link in the footer section.

June 20, 2018 at 1:31 pm

thank you so much sir.It helped me very much

February 24, 2019 at 10:08 pm

Need more information

April 27, 2019 at 7:36 pm

Thanks…

December 10, 2022 at 10:19 am

Need more information plz

June 12, 2019 at 6:47 am

Amazingly described! Helped a alot !!!! Thanks 🙂

September 14, 2019 at 2:07 pm

Thanks for your help

December 19, 2019 at 3:36 am

Yes. This is the best Topic. Wonderful

January 26, 2020 at 10:38 pm

thank you its help to me for my semister examination

April 21, 2021 at 8:41 am

Thank You So Much for helping us with the valuable content.

April 30, 2021 at 8:23 pm

Thankyou so much clerias.com. Really it is very helpful to all.

May 17, 2021 at 7:20 am

Okeh😎 It’s my pleasure

June 3, 2021 at 12:12 pm

It’s really helpful . Thank you so much 💖🖤 But Silent movement is an environmental movement in Kerala so it’s a state movement according to my text book Any way this work really awesome and helpful for my project as a referring guide THANK YOU ❤💌

July 28, 2021 at 10:08 pm

Thank you clearias.com…..you save me …this notes is very helpful for my upcoming exams thanks a lot….keep it up…..

October 7, 2021 at 11:02 am

it’s good information, nice work.

October 21, 2021 at 9:48 am

Singhbhum district is not in Bihar it is Jharkhand. If you’re mentioning before the partition of the state then you shouldn’t mention the line ” then it was spread in Jharkhand and Orissa”. Please keep your information correct.

November 23, 2021 at 8:56 am

It’s really so useful

November 27, 2021 at 9:19 pm

Excellent information ..Thankyou

May 12, 2022 at 4:14 pm

It’s really very much helpful . Thank you But Silent movement is an environmental movement Which must be going in India and Worldwide for water and wastewater treatment. Any way this work really awesome and helpful for my research as a referring guide THANK YOU 💌

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- Environmental Movements In India

Environmental Movements in India

An environmental movement is a type of social movement that involves an array of individuals, groups and coalitions that perceive a common interest in environmental protection and act to bring about changes in environmental policies and practices.

Environmental and ecological movements are among the important examples of the collective actions of several social groups.

This article will provide information about Environmental Movements in India in the context of the IAS Exam .

This is useful for the Environment section of the UPSC Syllabus .

The candidates can read more relevant articles from the links provided below:

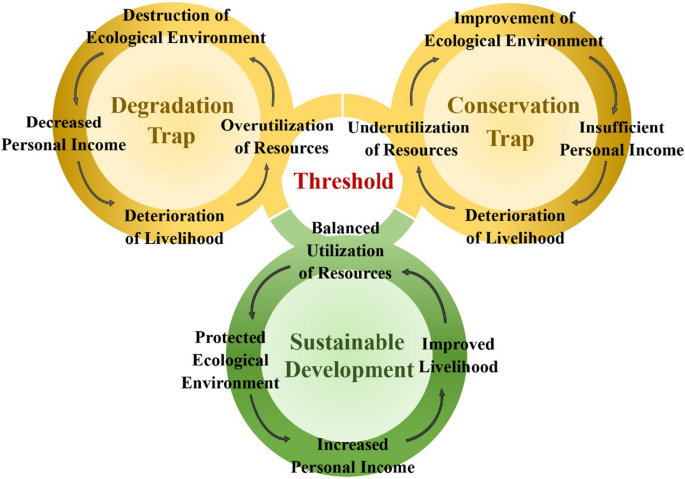

Cause of Environmental Movements

- The increasing confrontation with nature in the form of industrial growth, degradation of natural resources, and occurrence of natural calamities, has resulted in imbalances in the bio-spheric system.

- Control over natural resources

- False developmental policies of the government

- Right of access to forest resources

- Non-commercial use of natural resources

- Social justice/human rights

- Socioeconomic reasons

- Environmental degradation/destruction and

- Spread of environmental awareness and media

Major Environmental Movements in India

Many environmental movements have emerged in India, especially after the 1970s. These movements have grown out of a series of independent responses to local issues in different places at different times.

Some of the best known environmental movements in India have been briefly described below:

The Silent Valley Movement

- The silent valley is located in the Palghat district of Kerala.

- It is surrounded by different hills of the State.

- The idea of a dam on the river Kunthipuzha in this hill system was conceived by the British in 1929.

- The technical feasibility survey was carried out in 1958 and the project was sanctioned by the Planning Commission of the Government of India in 1973.

- In 1978, the movement against the project from all corners was raised from all sections of the population.

- The movement was first initiated by the local people and was subsequently taken over by the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP).

- Many environmental groups like the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and Silent Valley Action Forum participated in the campaign.

To read more about the Silent valley movement , check the linked article.

Chipko Movement

- Chipko Movement started on April 24, 1973, at Mandal of Chamoli district of Gharwal division of Uttarakhand.

- The Chipko is one of the world-known environmental movements in India.

- The movement was raised out of ecological destabilisation in the hills.

- The fall in the productivity of the forest produces forced the hill dwellers to depend on the market, which became a central concern for the inhabitants.

- Forest resource exploitation was considered the reason behind natural calamities like floods, and landslides.

- On March 27 the decision was taken to ‘Chipko” that is ‘to hug’ the trees that were threatened by the axe and thus the chipko Andolan (movement) was born.

- This form of protest was instrumental in driving away the private companies from felling the ash trees.

To read more about the Chipko movement in detail, check the linked article.

Bishnoi Movement

- This movement was led by Amrita Devi, in which around 363 people sacrificed their lives for the protection of their forests.

- This movement was the first of its kind to have developed the strategy of hugging or embracing the trees for their protection spontaneously.

To read more about Bishnoi Movement in detail, check the linked article.

Appiko Movement

- It is a movement inspired by the Chipko movement by the villagers of Western Ghats,

- In the Uttar Kannada region of Karnataka, the villagers of Western Ghats started the Appiko Chalewali movement during the month of September – November 1983.

- Here, the destruction of forest was caused due to commercial felling of trees for timber extraction.

- Natural forests of the region were felled by the contractors, which resulted in soil erosion and drying up of perennial water resources.

- In the Saklani village in Sirsi, the forest dwellers were prevented from collecting usufructs like twigs and dried branches and non-timber forest products for the purposes of fuelwood, fodder, honey etc. They were denied their customary rights to these products.

- In September 1983, women and youth of the region decided to launch a movement similar to Chipko, in South India.

- The agitation continued for 38 days, and this forced the state government to finally concede to their demands and withdraw the order for the felling of trees.

To read more about Appiko Movement in detail, check the linked article.

Narmada Bachao Andolan

- Narmada is one of the major rivers of the Indian Peninsula.

- The scope of the Sardar Sarovar project, a terminal reservoir on Narmada in Gujurat in fact is the main issue in the Narmada Water dispute.

To read more about Narmada Bachao Andolan in detail, check the linked article.

Jungle Bachao Andolan

- Jungle Bachao Andolan began in the 1980s in the Singhbhum district of Bihar (presently in Jharkhand).

- It was a movement against the government’s decision to grow commercial teak by replacing the natural Sal forests.

- The tribal community is the most affected by this decision as it disturbs the rights and livelihood of Adivasis of that region.

- This movement was widely spread in states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha in various other forms.

To read more about Jungle Bachao Andolan in detail, check the linked article.

Environmental Movements in India [UPSC Notes]:- Download PDF Here

Other related links:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Sign up for alerts

- 17 March 2021

The origins of India’s environment movement

Women hug trees during the Chipko Andolan of the 1970s, one of the strongest grassroots movement to conserve forests in India. © Wikimedia Commons

Born in the 1960s, I belong to a generation that witnessed the evolution of the environment movement in India.

As a child, I remember reading articles on wildlife in magazines such as the Illustrated Weekly of India . They buttressed the point that breathtaking wildlife existed in the jungles of India and needed to be preserved for posterity. This was conservation from the top, led by a number of old landlords and ex-civil service officers from the British Raj, many of whom had been game hunters ( shikaris ) in their youth but had reformed to become devoted conservationists.

Meanwhile, important events were happening worldwide. The Stockholm Declaration in 1972 followed by the Brundtland Commission Report in 1987 and the ‘World Commission on Environment and Development’ (WCED) were making waves. These gave birth to ideas such as ‘precautionary principle’, ‘assimilation capacity’, ‘polluter pays principle’, ‘public trust doctrine’, ‘inter-generational equity’ and ‘sustainable development’, terms that were to gain currency in the years to come. Picked up by activists and journalists at home, these international developments had a trickle-down effect on India. It was no more just a question of beautiful wildlife or idyllic landscapes. Human communities came into the picture too.

Being a birdwatcher, I travelled into the countryside quite often and soon my interest in birds transitioned into a concern about the fate of their habitats. Just like missionaries advocate shunning vices and living an austere life, we conservationists propagated messages like ‘Give up shikar ’, ‘Don’t kill animals’.

Here’s how a typical conversation with a villager would go (we were mostly dressed in western clothing and were referred to as sahib — an old colonial term for a British officer):

“ Ram Ram (greetings) sahib , what are you doing?”

“ Hum chidiyon ki padhai karte hain. (We study birds).” We would be amused at their reaction, which couched something like: “They come all the way from the city just to see these birds? Don’t they have anything better to do?’

Similarly, to the question if local people killed birds for food or shikar , sometimes the answer would be, ‘Why not?’ The simple villager did not see things in the way we expected them to. Come to think of it, from their perspective, killing birds for meat or stealing their eggs were for survival.

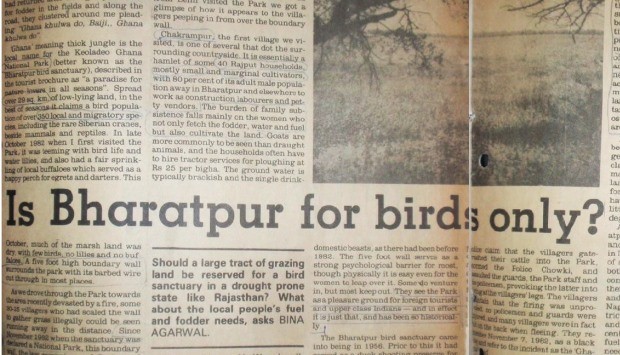

The unique problems in conservation faced by developing countries can be well illustrated by the controversy over cattle grazing at Keoladeo Ghana Bird Sanctuary in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. The sanctuary’s rich biodiversity and conservation significance are well known but a totally different picture emerges when you flip the coin. The park also happens to be the only grazing ground for thousands of cattle belonging to farmers from 14 nearby villages. In the arid, hostile wilderness of the Rajasthan desert, competition for scarce resources makes this park a battleground.

In the 1980s some well-meaning scientists, ornithologists and conservationists, headed by a Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) team under its charismatic ornithologist director Salim Ali, appealed to the Indian government to enforce a ban on cattle-grazing to make Keoladeo an inviolate space for birds, particularly for the highly endangered migratory Siberian crane which used to winter in the park.

For centuries, the villagers had grazed their cattle in the park without any objection from the rulers of the princely state of Bharatpur, whose ancestors had created the park as a private hunting preserve. But with this ban, enforced with all the might of the state, the villagers were incensed. There were numerous clashes between locals and the police and park officials, and several people died in this pitched resistance battle. Newspapers questioned: ‘Is Bharatpur for birds only?’ (Similar questions were raised when Project Tiger was kicked off in the 1970s).

The 1980s saw interesting developments in the environment protection movement. It was also a time before the liberalisation of the economy and globalisation when the intelligentsia was yet to warm up to private enterprise and industry. I recall a conversation with a highly placed friend, who commented cynically on a TV advertisement of a new motorcycle with a tagline “Fill it, shut it, and forget it”. The biker in the advertisement roared with his machine into the countryside, on a long and winding road into forests and hills. “Look at the attitude of the greedy capitalist class which wants the environment and wildlife to be preserved so that only they and their children can enjoy it," my friend said angrily.

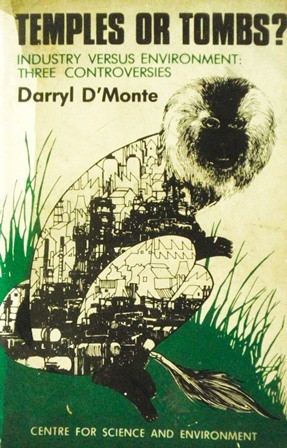

The environment versus development debate hogged the headlines. At the height of the campaign to protect the Silent Valley forest from the construction of a dam across the Periyar river, I remember politicians from Kerala saying that development was more important than the environment because people want jobs, a better lifestyle and livelihood. They maintained there was nothing wrong if tropical evergreen forests of the Silent Valley are cut down to make way for the dam.

Environment journalist Darryl D'Monte examined the politics behind the Silent Valley dam and other industries versus environment controversies in his book ‘ Temples or tombs? ’, where ‘temple’ alluded to India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s reference to industries and dams as temples of modern India, signifying progress and modernity. Whether these temples spelt doom for the environment was the core concern of the book. Interestingly, the cover of the book had an outline of the lion-tailed macaque — a species of monkeys endemic to the Western Ghats of India — that would be affected if the proposal to build the dam at Silent valley came through.

During this time, the manner in which people wrote about the environment was changing. The first signs of change was the first citizens report on India’s environment compiled by Anil Aggarwal and his team at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).The project was inspired by environmental movements in other countries, notably in south east Asia.

We read about the ‘ Chipko Andolan ’— a grassroots level movement started by women in the Himalayan district of Chamoli who hugged the trees to protect them from being cut by a sports goods manufacturing industry ( chipko is Hindi for hug). Unconventional but important questions were being asked, for instance, how many miles does a village woman have to walk to fetch enough firewood to cook her day’s meal or to collect enough water for the family’s daily needs? The message was clear: it is in people’s interest that the forests remain.

The conflicts between different types of social realities were becoming increasingly apparent. The gap between rural hinterlands and urban areas — the proverbial ‘Bharat-India’ divide — was more pronounced. Later, writers attempting to develop a theoretical structure of environmental studies in India were to supply interesting terms such as ‘ecosystem people’ for those living in the rural hinterland and ‘global omnivore’ for people living in urban areas and enjoying a high (energy) consumption lifestyle and heightened consumer choices.

Such reportage also forced a new type of thinking about people and the environment in general. The so-called elite conjured up an image of poor, rural folks as criminals harming the environment. For instance, cow dung, which ought to have been returned to the earth for recycling and making the soil fertile was being burnt by them as dung cakes. India’s then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi made a famous statement at an environment conference of the United Nations saying, ‘Poverty is the worst polluter’, which in hindsight appears politically incorrect.

In the middle of all these developments, how did academic institutions, colleges and research departments in Universities react? The short answer is by cocooning themselves in their ivory towers.

Some examples from pollution studies, which formed the bulk of presentations in seminars and meetings highlighting environmental conservation, are illustrative. A huge amount of toxicological research was being published from the biology and chemistry departments of Universities, estimating lethal dose (LD50 studies) on a variety of animals and plants. Much of it, grey literature, went into oblivion for the lack of clarity about the real issues and poor experimental designs. The only purpose they served was getting people their PhDs and jobs, and mouthing platitudes about the environment.

A recent article by an Indian Institute of Technology professor, Milind Sohoni, rightly pointed out that the training in our elite institutions and the national curricula does not empower ordinary students to probe their lived reality. Rather, it perpetuates a ‘peculiar intellectualism’ divorced from the community in which these institutions are embedded. No one, at least in academic circles, seemed to question seriously the fact that most chemical toxins were being dumped in rivers by industries and not so much by the local people, whose wastes were mostly organic and of a biodegradable kind.

The author is an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Delhi. He is writing a book on his experience as a biologist in India.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nindia.2021.40

Reprints and permissions

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Increase Font Size

33 Environmental Movements in India

1. Introduction

2. Emergence of Environmental Movements in India: A Short History

3. Forms of Environmental Conflicts

a) Conflicts over Forests

b) Movements in the Mining Sector

c) Movements over Water

4. Typologies and Frameworks

5. Strategies in the Environmental Movements

6. Sociological Significance and Emerging Trends

1. Introduction

Environmental movements in India have emerged from 1970s onwards as critiques of state sponsored forms of development. Natural resource based conflicts over the access and use of natural resources in different parts of the country lie at the centre of these environmental movements. These movements have resisted ‘increasing commodification and monopolization of natural resources like land, water, forests, their unsustainable use and unequal distribution, exploitative power relations, the centralization of decision making and disempowerment of communities caused by the development process. They asserted people’s rights over natural rights and decision making processes (Sangvai 2007: 111). However we cannot speak of a singular trajectory of the environmental movement in India, as the environmental discourse is constituted of multi-sited events, a range of practices, political and institutional contexts, a diversity of actors and frameworks of thinking and intervention (Brara 2005). The situation gets additionally complicated when ‘actions deemed as environmental cross cut parallel forms of collective actions in the field of ethnicity, gender, regional autonomy, labour and human rights’ (Dwivedi 2001).

Environmental movements in the West have been emphasizing ideas of conservation, deep ecology, quality of life and past-materialistic values. Therefore, they have been understood more as new social movements which are believed to gather support along lines of ‘personal and moral conviction’ and not relate to class per se. But ecological movements in India show continuities with the classical social movements while exhibiting some features of new social movements. Although they appeal to certain universal values, ecological struggles have been found to affect certain classes of people more, giving importance to the question ‘who should sacrifice and for whose benefit?’ In fact, the ecological struggles have acted as a medium through which the tribals, peasants, backward castes, fisherman or people displaced from their means of livelihood due to large projects, along with organized and unorganized workers, small entrepreneurs and manufacturers and all those who are surviving on land, forests, rivers, ponds and sea and other local resources stake their claim to these natural resources. In short, in the words of Ranjit Dwivedi, ‘environment movement is best understood as an ‘envelope’ as it encompasses a variety of socially and discursively constructed ideologies and actions, theories and practices’ (2008: 12).

2. Emergence of Environmental Movements in India: A short history

The emergence of environmental movements in India can be traced back to the British period, though they were not known as ‘environmental movements’ then. People’s bitter resistance to the taking over of large areas by the colonial state to put it to intensive forms of resource use like commercial forestry are quite well known. This led to prolonged fights and social conflicts between the colonial state and its subjects. The British tried to restrict access to forests, common lands, forest produce which came to be construed as an infringement of customary rights of forest dwellers, hunter gatherers, nomadic and pastoral communities, farmers etc, jeopardized their survival and resulted in peasant rebellions. These uprisings were not understood as environmental movements as such, but they contained elements for which they could be considered as precursors of later day ecological struggles. For example, in the years following the World War I, people resisted acquisition of land by the Tatas for building a dam at Mulshi, near Pune, which would supply power to the city of Bombay. It has come to be known as one of the earliest environmental movements in India. Senapati Bapat, a Congress man, led the local people and succeeded in halting the construction of the dam for nearly a year till the Bombay government promulgated an ordinance that the Tatas could acquire land on payment of compensation. This caused a split in the movement, whereby one section, namely the Brahmin landlords of Pune, who owned lands in the Mulshi valley, were willing to part with their land for the project in return for compensation whereas the cultivators and their leaders were totally opposed to the idea. Peasants had to give in being opposed by the power company, the British government and the landlords; but the movement succeeded in securing reasonable compensation from the Tatas in exchange of land. They did not proceed with dam building in other sites subsequently.

The emergence of the environmental movements in post independent India during the 1970s was a response to the nature of policies of development and governance followed by the nation state. The process of economic development led to more intensive resource use. According to Gadgil and Guha (1994), earlier the conflicts had emerged out of competing claims over the forests, now a distinct ecological dimension was added to these socio-political conflicts as they took place in the context of a dwindling resource base affecting the poor peasants and tribals. In independent India another kind of conflict which has evoked huge popular response pertained to the social consequences of the river valley projects. According to an estimate, given by Gadgil and Guha (1994: 8), till about mid 90s around 11.5 million people have been displaced due to building of dams without any thought of compensation or rehabilitation. Therefore, movements representing dam displaced people have gained in importance over the past 30 years. Although the displacement caused by dams is said to be for greater good, the Indian villager today is reluctant to make way without resistance.

In the contemporary period characterized by globalization, what marks the attitude towards nature and its resources is the profit motive of the private multinational companies. The gradual withdrawal of the state making way for private extractive capital has meant an increase in assault on nature and natural resources and a near total disregard for the ecosystem people who live close to it. Hence we see violent conflicts leading to even deaths of the people who are willing to lay down their lives protecting their land, culture, identities and ways of life.

3. Forms of Environmental Conflicts

In the Indian context environmental movements have arisen in a number of sectors as a result of the nature of development followed by the Indian state. We may discuss the following major sectors:

a) Conflicts over forests: This issue dominated the early years of the environmental movements’ discourse. For the first 20 years, the question of ‘forests for whom and for what?’ animated a series of protests which swept the Himalayan region in the early 1970s. The Chipko movement ‘reflected the widespread resentment among the hill peasantry directed at State forest policies which had consistently favoured outside commercial interests at the expense of their own subsistence needs for fuel, firewood and timber’ (Gadgil and Guha 1994: 104). It brought into focus wide ranging issues which had environmental implications. It also inspired a series of conflicts in the tribal dominated Central Indian regions like Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa, Maharashtra where the dependence on the forests was much more direct. This period also saw the growth of commercial forestry in the form of monocultures of eucalyptus. Popular movements which defended customary rights of the forest dwellers (over forests) aimed at two things: a) they claimed that the forests which had been acquired by the State in the name of forest management be returned to the people so that they can manage it without the intervention of the forest department, and b) they opposed the commercialization of f orests, emphasizing the subsistence orientation of the communities who were dependent on it. Thus, the period after independence, though marked by greater talk of people’s participation and ecological security, also saw an increase in competing sets of demands over the forests and its produce.

In the context of globalization, India’s environmental resources are under siege. This period has seen an increase in the rapacious intent of the state and private capital to use India’s natural resources without bothering to be accountable in any way. In fact, in February 2013, the Ministry of Environment and Forests issued a circular that it would not be mandatory for the Grama Sabhas to give permission for diversion of forest land to be used for linear infrastructural development projects such as roads, canals, power transmission lines etc. This circular violated an important clause of the Forest Rights Act 2006. In another instance, the Minister of Environment and Forests was pushed out to make way for a new minister who by her own admission granted ‘forest clearance’ to 754 out of 828 projects after 2011 within a period of just 18 months (EPW 2013). For example, there is a lot of resentment among people in Sambalpur district of Orissa as the government has granted permission to build roads for laying a water pipeline through a one hundred year old community managed forest. ‘Development at all costs’ with the help of private capital, is the new slogan in support of globalization induced industrialization, which will make India one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Significantly, enhanced mining, exploitation of marine resources, commercialization of agriculture and other processes have been the direct results of trying to rapidly increase export earnings. The logic of the current phase of globalization dominated by profit interest is based on externalization of environmental and social costs of development (Wani and Kothari 2008). Therefore, once again, we have a renewed spate of environmental movements in different parts of the country.

b) Movements in Mining Sector : Exploitation of mineral resources especially open cast mining in the sensitive watersheds of Himalayas, Western Ghats and Central India has caused a lot of environmental damage. People’s protests in these regions opposing the reckless effect of mining leading to their physical and economic survival have been documented by many scholars (Shiva and Bandyopadhyay 1988, Gadgil and Guha 1995). Notable among these was the successful resistance against limestone quarrying in the Doon Valley which led the Supreme Court to pass a judgement circumscribing the area of mining. All but 6 mines were closed. But movements against mining everywhere not managed to garner the same kind of attention either from the media or from the judiciary. For example, mining of soapstone and magnesium in other interior places like Almora and Pithoragarh districts of Kumaon leading to degradation of common forest and pasture land, a reduction in the local access to fuel, fodder and water continued apace. Social activists and villagers in the area have struggled hard to raise the consciousness of the villagers and the state authorities which eventually led to the closure of several mines in the area. Subsequently villagers have turned their energies towards land reclamation through afforestation. In the more recent years, mining in Orissa has been at the heart of many people’s struggles.

Orissa is one of the most mineral rich states and contains more than half of the bauxite reserves and about one-third of the iron ore reserves of our country. Quite like its neighbours like Jharkhand and Chattisgarh, Orissa is expecting large revenues from its mineral resources and is also inviting steel, aluminium and power companies to the state with promises of land, cheap power and easy access to the raw materials. Expectedly so, the state is witnessing a lot of resistance from its people at Kashipur, Niyamgiri, Kalinganagar, Jagatsinghpur who stand to lose their land, livelihood, social, religious and cultural rights to foreign multinational companies like Vedanta and Posco.

In the era immediately after independence, it was the state who led this process of displacement and dispossession due to the building of dams, military establishments, and iron and steel plants and other such public sector industries. Two almost year-long people’s struggles at Gandhamardan Hills in Sambalpur district against bauxite mining by BALCO and at Baliapal in the mid-1980s were successful in stalling large projects and continue to inspire people’s mobilizations thereafter. During the post 1990s, ‘private capital has begun replacing state projects as the major driver of enclosures, displacement and environmental damage’ (Kumar 2014: 67).

c) Movements over Water Resources: Water too has emerged as a major source of social conflict in different parts of India. According to Gadgil and Guha (1995), ‘inequitable control leading to mismanagement of water resources underlies many aspects of India’s environmental crisis.’ Large river valley projects which have come up at a fast pace since independence has been the mainstay of the India’s development. In the name of harnessing the water resources, these large river valley projects have led to submersion of forests and agricultural lands on a large scale. Ecology movements have emerged emphasizing the issue of exploitation of forests and agricultural lands as these have been the material basis for the survival of a large number of people in India, especially the tribals (Bandyopadhyay and Shiva 1988/2013). Most notable among people’s movements against dams on this issue of submersion are Bedthi, Inchampalli, Bhopalpatnam, Narmada, KoelKaro etc. People’s movements against widespread water logging, salinization and resulting desertification in the command areas of many dams like Tawa, Kosi, Gandak, Tungabhadra, Malaprabha etc., have been registered. While excess water led to ecological destruction in these cases, improper and unsustainable use of water in the arid and semi-arid regions also gave rise to people’s protests. The anti-drought and desertification movements have become very strong in the dry areas of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Orissa. Water based movements like Pani Chetana, Pani Panchayats, Mukti Sangharsh etc., have been advocating ecological water use.

In the decade of the 80s, the Narmada Bachao Andolan provided ‘an archetype of environmental representation and action’ (Brara 2004: 113). Following this agitation, mobilisation and resistance against big dams elsewhere in the country became more frequent and are also widely reported in the media. The movement has questioned the resettlement of the people displaced by the dam and eventually the model of development pursued by the state.

In the recent years, the Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti in Assam under the leadership of Akhil Gogoi has been fighting against big dams on Brahmaputra and attracting the ire of the government. Ecological groups have been joining hands to oppose the projects and say that they do not support the building of big dams in a highly sensitive seismic zone. Thousands of people including farmers, school teachers, students, daily wage earners have come together to oppose the Lower Subansiri Hydroelectric Project as its impact on a host of aspects like fisheries, agriculture, earthquake etc is not yet clear. Despite these protests, the State government and the NHPC are hell bent on going ahead with the project.

According to a report in Down to Earth magazine published by Centre for Science and Environment, Arunachal Pradesh has been planning about 168 hydroelectric projects both big and small. It has signed numerous memoranda with various private and public sector companies to develop hydel power in the state, so much so that protests against dams are gradually snowballing into political movements in the region. (Dutta: 2010). It is believed that together they will endanger the lives of people both upstream as well as downstream. There is a persistent clamour from the environmentalists for decommissioning the dams as they have limited potential for irrigation, development and flood control.

4. Typologies and Frameworks

Creating typologies that structure empirical social reality in order to provide a clear and precise understanding has been attempted in sociology in its efforts to develop as a scientific discipline. Typologies create order out of the chaos presented by diverse empirical phenomena. Though there are limits that typologizing imposes on our understanding of social reality, social scientists have nevertheless constructed a variety of typologies of social movements.

Social movements have been classified on the basis of issues around which participants get mobilized. Accordingly some of the movements are known as forests, civil rights, anti-untouchability, linguistic, nationalist movements and so on. Social scientists have also classified movements on the basis of the participants such as peasants, tribals, students, women, dalits etc. In many cases, the participants and the issues go together. Some movements have participants who belong to different strata of society. For example, if ecological issues like the preservation of forests are raised by the tribals, should that movement be treated as a tribal movement or an ecological movement? After all, sustenance of forests is important for the livelihood of the tribals. At the same time the tribals are also raising larger ecological issues. Therefore, according to Ghanshyam Shah (2002), ‘issues like ecology and civil liberties are not merely class issues or social group based issues, though in the given system they affect certain classes more than the others’. For example, Ramachandra Guha’s path breaking work on the Chipko movement (1988) drew from two different kinds of traditions, i.e. the trajectory of peasant movements in the region and an ecologically oriented history on the other to understand peasant resistance against commercial forestry in the Himalayas. Similarly Sujata Patel’s work (1989) on the Baliapal agitation mapped the people’s mobilisation against the State’s decision to acquire land to create an Intermediate Missile Testing Range as it would not only lead to displacement, but also to a destruction of the flourishing local agricultural paan economy, loss of bheetamati (home and the hearth) ‘sonar mati’ (of land in general) . Therefore, economic, environmental, and questions of community identity came together to reveal the complex and hybrid nature of the social movement.

Again, a social movement may come to be understood as an environmental movement later as fresh data is unearthed or as the framework of interpretation undergoes change. In such situations typologies too change. For example, Sourish Jha’s work (2012) on the historic forest dwellers movement in North Bengal in the decade of the 1950s and 60s, was directed against the ecologically exploitative, forest management practice of taungya, which was sustained through the collaboration and co-option of the forest dwellers themselves since the colonial period and even after independence. The study questioned the idea of ‘the environmentalism of the poor’ which restricted the understanding of the struggle merely around the issues of livelihood and subsistence. The movement had not only demanded ‘a fair distribution of ecological goods, recognition of rights of the ecosystem people but also a fair system of harnessing natural resources free from corruption, a fair opportunity of employment of those people who were involved in the process of regeneration, felling and maintenance of forests. It was also a movement for restoration of their own dignity’ (Jha 2012: 117).

Therefore, environmental movements defy easy classification, they are never exclusively ecological, they are always aligned with a host of other issues like freedom, justice, human rights, questions of identity etc., which reminds us of the complexities of the situation as well as the limitation of typologies. The same is true about many other types of new social movements as well. It is worth arguing here that as compared to old social movements, new social movements are difficult to classify.

5. Strategies used in the Environmental Movements

Environmental movements over the years have used several innovative strategies of protest which have largely been of a non-violent nature. The environmental movements have adopted non-violence ‘not only as a matter of strategy but almost as a matter of principle’ (Sangvai 2007: 116), as they have been opposing the violence of injustice, inequality and exploitation perpetrated by processes of development. In fact, such an orientation has led them to ‘explore ways of making non-violent satyagraha more effective, intensive and wider.

The forms of protest range from a contravening of statutory laws to spontaneous outbursts like the act of hugging of trees by women in the Chipko movement as an attempt to safeguard them from being felled. Mass actions like demonstrations, dharnas , indefinite hunger strikes, village level actions have been a part of environmental protests. The Narmada struggle has also evolved the satyagrahas against submergence. In the early years of the struggle against the Sardar Sarovar Dam, padayatras through villages which would be affected, were a means used by its leaders for conscientization and mobilization. Sri Sunderlal Bahuguna’s hunger strike as a mark of protest, and also intended to pressurize the government to stop construction of the Tehri Dam during the decade of the 80s is quite well known.

The use of litigation to stop ecologically degrading activities has also been a step which has been taken up from time to time along with other forms of social protests, by social activists and the affected people in an area. This was seen during the course of the construction of the Tehri Dam in the Uttarakhand region in the 1970s-80s when the Tehri Dam opposition committee appealed to the Supreme Court against the proposed dam by identifying it as a threat to the survival of people living near the river Ganga upto West Bengal. The ecological movement against the Silent Valley project in Kerala during the late 70s-early 80s, along with attempts at people’s mobilization also appealed to the Prime Minister for intervention as the building of the dam would be a threat ‘not to the survival of the people directly, but to the gene pool of the tropical rainforests threatened by submersion’ (Bandyopadhyay and Shiva 2013: 326).

In the more recent years, protests against the Polavaram Dam on Godavari river in Andhra Pradesh also used different methods like rallies and dharnas , silent protests and submission of memorandums to government officials, organizing discussion forums and seminars on the issue, keeping the debate alive on the issue, mass demonstrations involving eminent social activists, environmentalists, long marches on foot and cycle yatras to build solidarity and sensitize communities and relay hunger strikes. As many as 2000 tribal women organized and participated in a mahilagarjana expressing their anguish and protest over the building of the Polavaram dam. All these protests took place quite spontaneously in different parts of the tribal belt under the local leadership. A unique method of protest adopted by oustees of the Omkareshwar Dam on the Narmada river in Madhya Pradesh was jalsatyagraha protesting the proposed increase in height of the dam and a complete disregard of the promised rehabilitation policy by the authorities. The oustees of the dam were being forced to resettle in stony sites and in forest villages where no employment was available, neither construction of houses was possible.

Non-violent mass action has been an effective political instrument in the hands of the poor, the weak and the dispossessed. There is also a progressive realization within such people’s movements that non-violent mass actions would be effective if accompanied by simultaneous action on other fronts like support from the media and other environmental groups, political lobbying, international campaigning and coordination along with other movements which would create both publicity and pressure on the governments to act.

6. Sociological significance and emerging trends

The sociological significance of environmental movements lies in the fact that they lay bare the contradiction at the heart of the capitalistic enterprise. Capitalism looks at nature as a resource to be exploited for profit; it regards the human relationship with and dependence on nature as secondary and generates conflicts between competing worldviews and orientations. Environmental movements foreground these conflicts and contradictions.

Secondly, as Gadgil and Guha (1994: 101) articulate, ‘the environmental movement has added a new dimension to the meaning of democracy and civil society’. Environmental movements have been accommodative of a wide plethora of actors and voices namely tribals, farmers, lower caste groups, middle class academics and social activists, women, scientists and experts, traders, political workers, non-governmental organisations and so on. These constituencies have actively forged alliances, and attempted to influence the state’s actions from time to time giving meaning to the idea of a democracy. We find that in the course of their challenge to the State, even a section of the Maoists are also stressing upon these issues.

Thirdly, it posed an ideological challenge to the meaning, content and patterns of development. As Sangvai (2007) has articulated, these environmental movements have established that along with issues like protection against unjust displacement, employment oriented decentralized small units, food security, housing rights, environmental sustainability, agricultural-industrial policy are all interlinked in the quest for equality in a democracy. A few other values which these movements espoused pertained to a non-hierarchical mode of functioning and organizing, a focus on forging alternatives and an increasing emphasis on the small and the local.

7. Summary

In modern society the relation between nature and society has become increasingly central and complex with wide ranging implications which are not necessarily restricted to a society or a class per se. According to Gunnar Olofsson (2014) among the new social movements it is the environmental movement which manages to bring together issues which are at stake personally along with social issues which affect the reproductive capacity of a society and economy at large.

These movements since their inception have challenged the State in its shifting avatars and its changing modes of governance through resource extraction, increasing use of violence and surveillance over the people and through accumulation by dispossession. Though they came to be known as environmental movements only in the mid 70s or so, there have been protests around access to and the use of natural resources even during the colonial period. Peasants, tribals and forest dwellers rose up in rebellion at different times against the colonial state over the acquisition of their land and the subsequent curtailment of their customary rights. In the post independence period too there have been many conflicts over dams, forests, pollution, mining, tourism, which have highlighted the fact that in most of the cases development has not really benefitted those who have had to give up their resources in the name of development, in fact such people continue to remain marginal as before as their customary rights over resources are taken away, the basis of their livelihood is gradually lost, their knowledge and skills gradually made redundant in a modernising society. In the neo-liberal era, the state has made way for the private capital to mount an assault on the resource rich regions of our country in a much more aggressive and rapacious manner. This has given rise to a renewed spate of environmental movements in these regions, which have seen even the use of physical violence over the protestors. This indicates that though marginalised by mainstream politics, in the near future environmental movements are going to grab centre stage as they highlight some of the basic conflicts of our time over natural as well as cultural resources, over voices, forms of expression and identities. Therefore, we need to pay attention to what they have come to reflect and symbolize.

- UPSC IAS Exam Pattern

- UPSC IAS Prelims

- UPSC IAS Mains

- UPSC IAS Interview

- UPSC IAS Optionals

- UPSC Notification

- UPSC Eligibility Criteria

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Admit Card

- UPSC Results

- UPSC Cut-Off

- UPSC Calendar

- Documents Required for UPSC IAS Exam

- UPSC IAS Prelims Syllabus

- General Studies 1

- General Studies 2

- General Studies 3

- General Studies 4

- UPSC IAS Interview Syllabus

- UPSC IAS Optional Syllabus

Environmental Movement – UPSC Environment Notes

- An environmental movement refers to a social or political initiative aimed at either conserving the environment or enhancing its overall condition.

- It is often interchangeably referred to as the ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement.’

- These movements advocate for the sustainable management of natural resources, emphasizing the protection of the environment through alterations in public policies.

- Many such movements focus on aspects of ecology, health, and human rights.

- Environmental movements exhibit a wide spectrum, ranging from highly organized and formally institutionalized endeavors to those characterized by radical informality.

- The spatial reach of these movements varies, encompassing local efforts as well as those with nearly global implications.

Table of Contents

MAJOR ENVIRONMENT MOVEMENTS IN INDIA

Bishnoi movement.

- Time Period: 1700s

- Location: Khejarli, Marwar region, Rajasthan state.

- Leaders: Amrita Devi, along with Bishnoi villagers in Khejarli and surrounding villages.

- Objective: To prevent the cutting down of sacred trees by the king’s soldiers for the construction of a new palace.

- Key Details: Amrita Devi, a female villager, couldn’t bear to witness the destruction of her faith and the village’s sacred trees. She, along with others, hugged the trees in protest. Tragically, 363 Bishnoi villagers lost their lives during this movement.

- The Bishnoi tree martyrs were followers of Guru Maharaj Jambaji, who established the Bishnoi faith in 1485, emphasizing principles that prohibited harm to trees and animals.

- Upon learning about these events, the king rushed to the village, apologized, and ordered the soldiers to halt the logging operations.

- Subsequently, the maharajah declared the Bishnoi state a protected area, prohibiting harm to trees and animals.

- This legislation remains in effect in the region to this day.

CHIPKO MOVEMENTS

- Location: Chamoli district and later Tehri-Garhwal district of Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Govind Singh Rawat, Dhoom Singh Negi, Shamsher Singh Bisht, and Ghanasyam Raturi.

- Objective: To protect trees on the Himalayan slopes from the axes of forest contractors.

- Sundarlal Bahuguna played a crucial role in educating villagers about the significance of trees in the environment, emphasizing their role in preventing soil erosion, promoting rainfall, and providing clean air.

- Women in the Advani village of Tehri-Garhwal symbolically tied sacred threads around tree trunks and hugged the trees, leading to the movement being called the ‘Chipko Movement’ or ‘hug the tree movement.’

- The primary demand of the protesters was for the benefits of the forests, especially the right to fodder, to be directed to the local people.

- The Chipko movement gained momentum in 1978 when women faced police firings and other forms of torture.

- Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna, the then Chief Minister, responded by establishing a committee to investigate the matter.

- The committee eventually ruled in favor of the villagers, marking a pivotal moment in the history of eco-development struggles in the region and globally.

SAVE SILENT VALLEY MOVEMENTS

- Location: Silent Valley, an evergreen tropical forest in the Palakkad district of Kerala, India.

- Leaders: The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), an NGO, and the poet-activist Sughathakumari played crucial roles in the Silent Valley protests.

- Objective: To protect the Silent Valley, a moist evergreen forest, from destruction caused by a proposed hydroelectric project.

- The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) proposed a hydroelectric dam across the Kunthipuzha River, which runs through Silent Valley.

- In February 1973, the Planning Commission approved the project with an estimated cost of about Rs 25 crores.

- Concerns arose that the project would submerge 8.3 sq km of pristine moist evergreen forest.

- Several NGOs vehemently opposed the project, urging the government to abandon it.

- In January 1981, succumbing to relentless public pressure, Indira Gandhi declared that Silent Valley would be protected.

- In June 1983, the issue was re-examined by a commission chaired by Prof. M.G.K. Menon.

- Subsequently, in November 1983, the Silent Valley Hydroelectric Project was canceled. In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi formally inaugurated the Silent Valley National Park.

JUNGLE BACHAO ANDOLAN

- Location: Singhbhum district of Bihar

- Leaders: The tribals of Singhbhum

- Objective: Opposition to the government’s decision to replace natural sal forests with teak.

- The tribal communities in the Singhbhum district of Bihar initiated the Jungle Bachao Andolan in protest against the government’s decision to substitute the indigenous sal forests with the more expensive teak.

- This action was criticized by many as a manifestation of “Greed Game Political Populism.”

- Subsequently, the movement expanded to encompass regions in Jharkhand and Orissa.

APPIKO MOVEMENT

- Location: Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka State

- Leaders: While not driven by a specific personality, the movement had a facilitator in Pandurang Hegde who played a crucial role in its initiation in 1983.

- Objective: Opposition to the felling and commercialization of natural forests and the degradation of traditional livelihoods.

- The Appiko Movement, locally known as “Appiko Chaluvali,” can be considered the southern counterpart of the Chipko movement.

- Local communities embraced the trees marked for cutting by forest department contractors.

- The movement employed various awareness-raising techniques, including foot marches in the interior forest, slide shows, folk dances, street plays, and more.

- The second focus of the movement was to promote afforestation on depleted lands.

- Subsequently, the movement shifted its attention to the sustainable use of the ecosystem by introducing alternative energy resources to alleviate pressure on the forest.

- The movement achieved success, and the current status of the project is reported to be halted.

NARMADA BACHAO ANDOLAN

- Location: Narmada River, flowing through the states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra.

- Leaders: Medha Patkar, Baba Amte, Adivasis, farmers, environmentalists, and human rights activists.

- Objective: A social movement opposing the construction of several large dams across the Narmada River.

- The movement initially emerged as a protest against inadequate rehabilitation and resettlement for people displaced by the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam.

- Subsequently, it broadened its focus to include the preservation of the environment and ecosystems of the Narmada Valley.

- Activists demanded a reduction in the dam’s height from the proposed 130 meters to 88 meters. The World Bank withdrew from the project.

- The environmental concerns were taken to court, and in October 2000, the Supreme Court approved the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam with the condition that the dam’s height could be raised to 90 meters.

- While this height was higher than the 88 meters demanded by anti-dam activists, it was lower than the proposed 130 meters.

- The project is now primarily financed by state governments and market borrowings, with an expected completion date of 2025.

- Although not entirely successful in preventing the dam, the NBA has significantly influenced public opinion against large dams in India and internationally.

- It raised questions about the development paradigm and, as a democratic movement, adhered to Gandhian principles.

TEHRI DAM CONFLICT

- Year: 1990s

- Location: Bhagirathi River near Tehri in Uttarakhand.

- Leader: Sundarlal Bahuguna

- Objective: The protest aimed to address concerns related to the displacement of town inhabitants and the environmental impact on the fragile ecosystem.

- The Tehri Dam gained national attention in the 1980s and 1990s, with major objections focusing on the seismic sensitivity of the region and the submergence of forest areas, including Tehri town.

- Despite support from prominent leaders such as Sunderlal Bahuguna, the movement struggled to garner sufficient popular support both nationally and internationally.

FAQs – Environmental Movements

1-what is an environmental movement.

An environmental movement is a social or political initiative dedicated to either conserving the environment or improving its overall condition. It is often referred to interchangeably as the ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement.’ These movements advocate for the sustainable management of natural resources and emphasize environmental protection through changes in public policies. They can focus on various aspects, including ecology, health, and human rights.

2-How diverse are environmental movements?

Environmental movements exhibit a broad spectrum, ranging from highly organized and formally institutionalized efforts to those characterized by radical informality. The nature and structure of these movements can vary significantly.

3-What is the spatial scope of environmental movements?

The spatial reach of environmental movements can vary widely, encompassing local efforts as well as those with nearly global implications. Movements may address local environmental issues or advocate for broader global concerns.

4-What is the Bishnoi Movement?

- Leaders: Amrita Devi, along with Bishnoi villagers.

- Objective: To prevent the cutting down of sacred trees by the king’s soldiers for a new palace.

- Key Details: The Bishnoi villagers, influenced by Guru Maharaj Jambaji’s teachings, protested by hugging trees. Tragically, 363 Bishnoi villagers lost their lives. The movement led to the protection of the Bishnoi state as a sacred area.

5-What is the Chipko Movement?

- Location: Chamoli district and Tehri-Garhwal district of Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, and others.

- Objective: To protect trees on the Himalayan slopes from forest contractors.

- Key Details: Sundarlal Bahuguna educated villagers on the importance of trees, and women symbolically hugged trees. The movement demanded local benefits from forests and gained momentum in 1978 with police firings.

In case you still have your doubts, contact us on 9811333901.

For UPSC Prelims Resources, Click here

For Daily Updates and Study Material:

Join our Telegram Channel – Edukemy for IAS

- 1. Learn through Videos – here

- 2. Be Exam Ready by Practicing Daily MCQs – here

- 3. Daily Newsletter – Get all your Current Affairs Covered – here

- 4. Mains Answer Writing Practice – here

Visit our YouTube Channel – here

- Challenges to Tiger Conservation – UPSC Environment Notes

- UN-REDD and REDD+ – Forest Carbon Partnership Facility – UPSC Environment Notes

- Deterioration of Carbon sink – UPSC Environment Notes

- UNFCCC Summits Post Kyoto – UPSC Environment Notes

Edukemy Team

Aquatic organisms – upsc environment notes, denitrification – nitrate to nitrogen – upsc environment notes, aichi biodiversity targets – upsc environment notes, loss of biodiversity – upsc environment notes, habitat – upsc environment notes, natural farming – benefits, challenges, zero-budget natural farming (zbnf) and..., total installed power capacity in india – upsc environment notes, solid waste – sources, treatment and disposal, measures to manage..., in situ conservation – upsc environment notes, national air quality index (aqi) – upsc environment notes, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Our website uses cookies to improve your experience. By using our services, you agree to our use of cookies Got it

Keep me signed in until I sign out

Forgot your password?

A new password will be emailed to you.

Have received a new password? Login here

GS Foundation

UPSC All India Mock Test – Edukemy Open Mock

Environmental Movements in India: All you need to Know

With the growing concerns for environmental degradation worldwide, we can feel the utmost need for a better environmental balance. Unfortunately, there are hundreds of instances of abuse, and only a little paid attention, and that too only when the local community protests. Usually, the conflict is seen as Environment v/s Development. We find that India is ranked 177 among 180 nations on the Environmental Performance Index 2018. In the contemporary world, numerous environmental movements launched against the developmental activities that have endangered our standard of living. Of course more than the leaders we need a common crowd to be engaged.

WHY DID WE FEEL TO BREAK OUT ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS?

It is always argued that sustainable development is the promoter of a stable environment. We definitely cannot do without the development goals. The era of the devastation of resources and causing an imbalance in ecology was stated explicitly by the Britishers in our country. Exploitation by them was validated by proving ‘our’ Indian traditional values as vague and ‘their’ scientific values as logical. They argued to manage the forests scientifically and it went into a conflict between them and local masses. Major reasons for the emergence of environmental movements can include Control over natural resources, false developmental policies of the government, socioeconomic reasons and Environmental degradation/ destruction. Moreover, we can include the spread of awareness as one another and a big factor. In the Indian context, many movements have emerged after the 1970s and 1980s.

VARIOUS ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS CAN INCLUDE:

- Chipko movement – It was a representative of a wide spectrum of conflicts in the 1970s and 1980s include conflicts over forests; conflicts about the large dams; conflicts about the social and environmental impacts of unregulated mining. The movement got this name as in Hindi “Chipko” means “to hug”. People started hugging trees to protect them. Chipko movement is a drive that practised the Gandhian approaches of ahimsa that is nonviolence and Satyagraha. It was started in 1973 in Chamoli district of Uttrakhand and later Tehri Garhwal. Sunderlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi and Chandi Prasad Bhatt were important leaders. Majorly it was against deforestation. Villagers especially women started the revolt. Then another major protest occurred in 1974 near Reni village where more than 200 trees were scheduled to be felled. Till 1980 we can witness the inclusion of more than 150 village demonstrations. Sunderlal Bahuguna took a 5000-kilometre Himalayan foot rally in 1981-83, spreading Chipko message to far With time it has become “Save Himalaya” movement. Also, Chandi Prasad Bhatt has bestowed the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1982 and Sundarlal Bahuguna with Padma Vibhushan in 2009.

- Narmada Bachao Andolan – It is the movement against the multipurpose dam project over Narmada river that would result in the displacement of local people and floods. The key reason is not providing proper rehabilitation and resettlement for the folks. The movement is led by Medha Patekar, Baba Ampte and Arundhati Roy. It is the most influential movement started in 1985. It supports two basic features of the Indian Constitution: the rights to life and livelihood. The dams force also destroys the inundation of forests. The long fight has resulted in the postponement of the work of the Sardar Sarovar dam project.