Gender and Politics

Gender and Politics Research Paper Topics

- The gender gap in political representation: causes and consequences

- Gender quotas in politics: pros and cons

- Women’s rights and political participation in the Middle East

- Women’s representation in local government: a case study of a specific country or region

- Masculinity and political leadership: how gender affects perceptions of leadership qualities

- Women’s access to political power in post-conflict societies

- Gender and political violence: how violence affects men and women differently

- The impact of gender on voting behavior

- The role of women in peacebuilding and conflict resolution

- Gender mainstreaming in international development policy: successes and challenges

- Intersectionality in politics: how race, class, and gender intersect to shape political outcomes

- The gendered impact of globalization on the labor market and political participation

- Gender and environmental politics: exploring the links between gender, environmentalism, and politics

- The impact of gender on political ideology and party affiliation

- Gender and political rhetoric: how gendered language affects political discourse

- The role of men in promoting gender equality in politics

- Feminism and political theory: historical and contemporary debates

- The impact of gender on political socialization and political attitudes

- The gendered nature of political scandals: how men and women are affected differently

- Women’s role in authoritarian regimes: case studies of specific countries

- The gendered impact of austerity policies on welfare states and social programs

- Gender and political participation in online spaces: how digital platforms are changing the landscape of political participation

- Women’s representation in the judiciary: a comparative analysis

- The impact of gender on media coverage of political campaigns

- Gender and international security: exploring the links between gender, security, and conflict

- The gendered impact of immigration policies and migration flows

- Gender and political corruption: how gender affects perceptions of corruption and ethics in politics

- Women’s role in political parties: a comparative analysis

- The impact of gender on political trust and legitimacy

- The gendered impact of economic liberalization and privatization policies

- Women’s representation in international organizations: a case study of the United Nations

- The role of gender in the formation of public policy and political decision-making

- Gender and political communication: how gender affects political messaging and public opinion

- The impact of gender on the formation and implementation of foreign policy

- Gender and the politics of social movements: exploring the role of women in movements for social change

- Gender and the politics of reproductive rights: a comparative analysis of policy and activism

- Women’s access to education and its impact on political participation

- The gendered nature of political institutions and processes: a comparative analysis

- Gender and the politics of identity: exploring the links between gender, race, and ethnicity in political discourse

- The impact of gender on the politics of healthcare and healthcare policy

- Women’s participation in local community governance: a case study of a specific region or country

- The impact of gender on political accountability and transparency

- Gender and political decision-making in the private sector: a comparative analysis

- The gendered impact of natural disasters on political outcomes and policy responses

- Women’s role in the politics of climate change: exploring the links between gender, the environment, and politics

- The impact of gender on political violence and terrorism

- Gender and the politics of nationalism: exploring the links between gender, nationalism, and identity

- Women’s role in the politics

- The Role of Intersectionality in Women’s Political Participation: An Analysis of Racial, Ethnic, and Class Differences in Political Mobilization.

- Women’s Representation in Political Leadership: Examining the Glass Ceiling in Parliaments and Executive Offices.

Women have historically been excluded from political decision-making, with men dominating positions of power in most political systems. This has led to a lack of representation of women’s perspectives and experiences in political decision-making, resulting in policies that do not adequately address the needs of all members of society. While progress has been made in increasing the number of women in political leadership roles in many countries, women continue to face unique challenges in accessing and exercising political power. These challenges include gender bias, discrimination, and social norms that prioritize men in political leadership.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

One way to address these challenges is through the use of quotas and affirmative action policies to increase the representation of women in political decision-making. Quotas have been implemented in many countries around the world, with varying degrees of success. Some argue that quotas are necessary to overcome the structural barriers that prevent women from accessing political power, while others argue that quotas are unfair and can lead to the selection of less qualified candidates. Regardless of the effectiveness of quotas, it is clear that increasing the representation of women in political decision-making is essential to creating more equitable and inclusive policies.

Feminist movements have also played a critical role in shaping political discourse and pushing for gender equality in political systems. Feminist movements have highlighted the ways in which gender shapes political systems and policies, and have worked to mobilize women to become more active in political decision-making. These movements have also pushed for policy changes to address gender-based violence, discrimination, and other issues that disproportionately affect women. By bringing attention to these issues, feminist movements have helped to shape political discourse and create more space for women to participate in political decision-making.

Despite these efforts, women continue to face significant challenges in accessing and exercising political power. Women remain underrepresented in political decision-making in many countries, and face unique challenges in accessing the resources and support needed to succeed in these roles. Addressing these challenges will require a sustained effort to increase the representation of women in political decision-making and to create more supportive and inclusive political environments.

In conclusion, gender and politics is a critical area of inquiry in political science, exploring the ways in which gender shapes political systems, policies, and outcomes. Women have historically been excluded from political decision-making, resulting in policies that do not adequately address the needs of all members of society. Quotas and affirmative action policies, as well as feminist movements, have been instrumental in addressing these challenges and increasing the representation of women in political decision-making. However, significant challenges remain, and continued efforts will be needed to create more equitable and inclusive political systems.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Background Essay: Women in the Political World Today

Directions:

Keep these discussion questions in mind as you read the background essay, making marginal notes as desired. Respond to the reflection and analysis questions at the end of the essay.

Discussion Questions

- Skim the quotes shown in Appendix B: Timeline and Quotes and select for discussion a few that most powerfully express the pathway toward legal equality for women.

- Regarding the principle of equality, have we achieved the promise of the Declaration of Independence? Are we there yet?

Before and after they won the right to vote, women have played an active role in American politics and public life. In the 1920s, the newly enfranchised women did not agree how to take the next steps towards legal equality. From the beginning of American history to the present, women of all backgrounds and political persuasions have exercised their First Amendment rights, voicing concerns that reflect their understandings of what constitutes the best way of life for a free people.

What historians call First Wave Feminism encompassed the period from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention to 1920 when the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed the right of American women to vote. The focus during this period was on removing legal barriers to women’s participation in political life. Even before the Nineteenth Amendment had been ratified, NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt founded the League of Women Voters, whose initial purpose was to provide non-partisan education for women’s new civic responsibility of voting. Just as they had advocated several different approaches to win the vote, the newly enfranchised women did not all agree on the next steps they should take in pursuit of full legal equality. State laws limiting women’s property rights, opportunity to serve on juries, education and job prospects, and other roles in society continued to be barriers to women’s civil, economic, and social goals.

Equal Rights Amendment Proposed 1923

The National Woman’s Party advocated an equal rights amendment to the Constitution, requiring that men and women would be treated exactly the same under all U.S. laws. In 1923, Alice Paul proposed an amendment stating, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” The amendment had many prominent supporters among professional women.

But many others did not support this idea. In particular, many “labor feminists” disagreed, arguing for “specific bills for specific ills.” In other words, these women argued that not all laws that treated men and women differently were bad. Discriminatory laws that hurt women should be repealed, of course, but they believed others, such as laws aimed at protecting women from especially long work hours, or laws requiring maternity leave should remain. About fifty years later, another equal rights amendment proposal would again fail to gain sufficient traction and fall in defeat.

As large numbers of women entered the work force during World War II, some in Congress spoke up to ensure equal pay for equal work. Republican Representative Winifred C. Stanley proposed a bill banning wage discrimination based on sex in 1942, but the bill failed. The 1944 Republican Party platform included support for an equal rights amendment.

By the end of World War II, a generation had passed since the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Many women of child-bearing age who worked outside the home during the war returned home, but others remained in the workforce. According to Department of Labor statistics, the labor force participation rate of women ages 16 – 24 declined slightly and leveled off through the 1950s, but labor force participation rates of women older than that have continued to rise throughout the succeeding decades.

Photograph of President Kennedy and former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, 1962. National Archives and Records Administration.

The President’s Commission on the Status of Women 1963

Just as the suffrage movement had gained strength alongside other social and legal reforms, the women’s movement of the 1960s developed alongside a Civil Rights Movement. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925 directing federal contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” This gave rise to what came to be called “affirmative action,” or taking steps to ensure greater numbers of minorities (and, later, women) were provided opportunities and access to various settings like college and the workplace.

President Kennedy was concerned about protecting equal rights for women. However, the proposed equal rights amendment stirred up fears of threats to women’s traditional roles among some conservatives across the country, and he needed to walk carefully in order to avoid angering those tradition-minded Democrats. Kennedy’s solution was the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, whose goal was to make recommendations for, “services which will enable women to continue their role as wives and mothers while making a maximum contribution to the world around them.”

Run by Esther Peterson, Assistant Secretary of Labor, and chaired by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the committee of 20 lawmakers and philanthropists examined employment practices, labor laws, tax regulations, and other factors that they believed contributed to inequality. The commission issued its report in 1963, calling for a number of reforms including:

- Equality of jury service

- Reform of property and family laws that disadvantaged women

- State laws guaranteeing equal pay for equal work

- Tax deductions for child care for working parents

- Expansion of widow’s benefits under Social Security

- Expanded adult education

- Taxpayer-funded maternity leave

- Taxpayer-funded universal day-care

One immediate response to the commission report was that Congress passed the Equal Pay Act (1963), prohibiting wage discrimination based on gender within the same jobs. The commission also likely heightened the sense among Americans that the national government should play an active role in promoting women’s equality.

Eleanor Roosevelt and others at the opening of Midway Hall, one of two residence halls built for female African American government employees, 1943. National Archives and Records Administration.

The Feminine Mystique and Second Wave Feminism

The express goal of the president’s commission had been to safeguard the important role of wives and mothers in the home, while expanding their opportunity to pursue additional roles and responsibilities in society. As did most of the earlier advocates for women’s equality, the commission valued the work of homemakers and wished to protect mothers’ vital role in the family. A new, “second wave” of feminism was about to gain strength and it challenged the assumption that this was necessarily the most vital role of women.

The same year that the commission released its report, Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, a critique of the middle-class nuclear family structure. Friedan pointed to what she called “the problem that has no name,” or the pervasive, below-the-surface dissatisfaction of middle-class housewives that she herself had experienced. Friedan argued these homemakers whose husbands provided a comfortable living for their families had been lulled into a false consciousness, believing themselves happy when they were actually bored and unfulfilled. This delusion was the “mystique.” If Friedan believed there was a cultural “myth” of a happy housewife, she created a new, competing narrative alongside it of frustrated wives held captive in what she called “a comfortable concentration camp.” While not every woman agreed that housewives were being fooled into believing themselves happy, this landmark book drew many white, middle-class women to what was called Second Wave Feminism

Second Wave Feminists rejected the idea that gender roles or morality flowed out of natural law. They believed gender roles were purely social constructs, and that morality, especially as it related to sexual conduct, was subjective. In their view, it was generally the consent or lack of consent between adults that made an act right or wrong.

Second Wave Feminists went beyond the legal equality as defined by earlier reformers to advocate also for measures intended to bring about equality of outcome. Groups such as the National Organization for Women, which Friedan helped found, lobbied for taxpayerfunded day care, no-fault divorce, legalized abortion (including taxpayer-funded abortions through Medicaid), and other reforms.

Photograph of Betty Friedan, 1960. Library of Congress.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The momentum for civil rights and women’s rights would converge again a year later. President Kennedy had asked Congress to pass legislation “giving all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public—hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments.” Congress began claiming authority under the Interstate Commerce Clause to regulate private businesses, reasoning that discriminatory practices by “public accommodations” such as restaurants and hotels affected citizens’ abilities to travel between states.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racial segregation in private businesses that served the public, and banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. It also banned discrimination in places receiving federal funds such as public universities.

Congress passed the Voting Rights Act the next year banning racial discrimination in voting. This federal law helped protect the rights of African American men and women in places where legal barriers such as literacy tests had been erected to prevent them from voting.

The Story Continues

Social scientists debate the effects of the cultural changes brought about by Second Wave Feminism. Many point to the numerous objective measures showing women today enjoy greater autonomy than at any time in U.S. history, and perhaps that of the world: high standards of living, educational attainment, and broad career choices. Yet, the National Bureau of Economic Research found in 2009 that subjective assessments of happiness were not keeping up:

“ By many objective measures, the lives of women in the United States have improved over the past 35 years, yet we show that measures of subjective well-being indicate that women’s happiness has declined both absolutely and relative to men. [Women] in the 1970s typically reported higher subjective well-being than did men.”

Second Wave Feminism was followed in the 1990s by Third Wave Feminism, which focused on layers of oppression caused by interactions between gender, race and class. And as has happened with all social movements fought in the name of women, many women rejected the movement and held more conservative views.

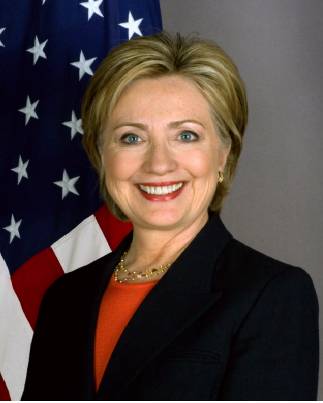

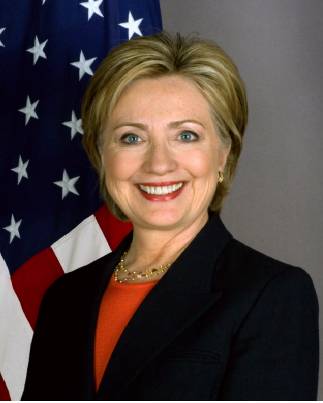

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, 2009. Department of State.

What effect has women’s suffrage had on politics?

It should be noted that, just as there are class, ethnic, and racial divisions among males, as well as other specific issue positions that influence an individual’s political choices, the same divisions exist among women. Women do not generally vote as a block. However, given that important caution, there are some identifiable differences between the voting trends of women compared to those of men. The Center for the American Woman and Politics (CAWP) at Rutgers

University tracks those trends. Beginning in the 1920s, women were a little more likely than men to favor the Republican Party, but that trend began to reverse by 1980, and women since then have continued to be more likely to favor the Democratic Party. In presidential elections since that time, women have preferred the Democratic candidate over other parties by four to ten percentage points. Since 1980, women’s turnout rate has been a little higher than that of men. Further, women are more likely than men to favor a more active role for the federal government in expanding health care and basic social services, to advocate restrictions on guns, to support same-sex marriage, and to favor legal abortion without restrictions.

In addition to making their mark as voters, women have gradually made their mark as successful candidates. In 1916, the first female member of Congress, Jeannette Rankin, won her bid to represent her district in Montana. In 1968, Shirley Chisholm of New York became the first African American congresswoman (though it should be noted that she did not want to be remembered by that description, but as a person who “had guts.”) According to CAWP data, in 1971 women made up three percent of people elected to U.S. Congress, seven percent of statewide elective offices, and 0 in state legislatures. In 2016, Democrat Hillary Clinton became the first female presidential candidate of a major party. In November 2018, women comprised 20% in U.S. Congress, 23.4 % in statewide elective offices, and 25.5 % in state legislatures. In the November 6 midterm elections, voter turnout across the nation was the highest in any midterm election in 100 years, with 50.1% of the voting-eligible population casting their ballots. As of January 2019, a record 121 women serve in the 116th United States Congress, 102 years after Jeannette Rankin was elected. Following the midterm election, women comprised 23.6 % in U.S. Congress, 27.6 % in statewide elective offices, 28.6 % in state legislatures.

Horace Greeley wrote in 1848, “When a sincere republican is asked to say in sober earnest what adequate reason he can give, for refusing the demand of women to an equal participation with men in political rights, he must answer, none at all. However unwise and mistaken the demand, it is but the assertion of a natural right, and such must be conceded.” Frederick Douglass in 1869 asked Susan B. Anthony whether she believed granting women the vote would truly do anything to change the inequality under the law between the sexes. She replied, “It will change the nature of one thing very much, and that is the dependent condition of woman. It will place her where she can earn her own bread, so that she may go out into the world an equal competitor in the struggle for life.” The political environment has changed considerably since the early days of women’s struggle for suffrage and equality. The participation of women in the public sphere has helped make the American republic more representative, and has removed many of the restrictions that formerly stood between individuals and the enjoyment of their natural rights.

Women of all backgrounds and political persuasions act on their understandings of what constitutes the best way of life for a free people, and suffrage is one of many important ways that they participate in public life. The principle of freedom of speech, press, and assembly, enshrined in the First Amendment, ensures the legal right to express one’s opinions freely, orally or in writing, alone or through peaceable assembly, no matter how offensive their point of view may seem to others. These First Amendment guarantees have been and will continue to be integral to the efforts of those seeking social and legal reforms in America.

REFLECTION AND ANALYSIS QUESTIONS

- What action did Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party advocate after women won the right to vote?

- What was the goal of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women?

- In the years leading up to the Commission, most women were married in their early 20s. Families had more children during this time than any other in American history (known as the Baby Boom), but they spaced their children more closely together so mothers were finished having babies at a younger age than other generations. What effect might this have had on women’s concerns at the time?

- What is Betty Friedan’s connection to Second Wave Feminism?

- Betty Friedan wrote, “The feminist revolution had to be fought because women quite simply were stopped at a state of evolution far short of their human capacity.” How does this view compare to that of early advocates for equality and suffrage such as Abigail Adams, Angelina Grimké, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, or Carrie Chapman Catt?

- In what ways did the principle of freedom of speech, press, and assembly empower Second Wave Feminists, as well as their opponents?

- Consider the “official” and “unofficial” methods of change. Direct action aimed at winning the vote had an impact, but so did opportunity to participate more fully in the workforce. How might expanding opportunities for work outside the home have reinforced – or hindered- the movement to win the vote?

- Use the Principles and Virtues Glossary as needed and give examples of ways the varying approaches to post-1920s efforts to expand rights for women reflected any three of the constitutional principles below. Further, give examples of how such reform efforts require individuals to demonstrate any three of the civic virtues listed below.

Principles : equality, republican/representative government, popular sovereignty, federalism, inalienable rights

Virtues: perseverance, contribution, moderation, resourcefulness, courage, respect, justice

Gender, Politics, and Women's Empowerment

Cite this chapter.

- Valentine M Moghadam 3

Part of the book series: Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research ((HSSR))

6018 Accesses

11 Citations

The literature on gender, women, and politics has examined both the gendered nature of political processes and women's participation patterns. Whether cast in terms of a variable or as an integral element of the social structure, gender is seen as pervading the realm of politics in that it reflects the distribution of power and reinforces notions of masculinity and femininity, and it influences the patterns of political participation by women and by men. Thus it is the social relations of gender — and the ways in which gender dynamics operate in the family, the labor market, and the polity — that explain why women have been historically marginalized from the corridors of political power, why feminists refer to “manly states” and “patriarchal politics” (Enloe 1990, 2007; Tickner 1992; Peterson and Runyan 1993), and why an essential policy prescription for enhancing women's political participation at both national and local levels is the electoral quota. By the same token, the operations of gender help us recognize the strategies for women's political empowerment, such as the formation of women's movements and organizations that have become prominent in civil society.

Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Feminists Reshaping Gender

Gender, Representation, and the Politcs of Exclusion: Or, Who Represents, Who Is Represented, What Is at Stake?

Gender, Power, and Networks: Women’s Organizing and Changing Gender Relationships in Africa and Latin America

- Civil Society

- Political Participation

Local Governance

- Democratic Transition

- Parliamentary Seat

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This chapter takes a global perspective to examine the gendered nature of politics and patterns of women's political participation in formal politics and in civil society, including involvement in web-based “virtual activism.” It presents research findings and policy debates on gender and politics, and provides data on women's political participation. It comes in four parts. In the first, we survey the feminist literature on gender and politics, including the identification of enabling factors and persistent obstacles. In the second, we examine the patterns of women's political participation in national and local government, political parties, and as heads of government or state. In the third, we review research on women and gender in civil society, social movements, transnational advocacy, and democratic transitions. The fourth section discusses the broad implications and impact of women's political participation.

Gendering Politics: What is at Stake?

Political scientists have developed a prodigious body of work arguing that in order for historically marginalized groups to be effectively represented in institutions, members of those groups must be present in deliberative, or decision making, bodies (Weldon 2002 ). These would include political parties, parliaments, and national and local governments. And yet, across history, culture, and societies, women as a group have been excluded from key decision making arenas in the government sector (national and local government) and the leadership of political parties, as well as in the other domains. Footnote 1 This is indicative of the gendered nature of politics.

Gender refers to a structural relationship between women and men — which historically has manifested itself as a relationship of asymmetry, domination and subordination — or to unequal power relations between men as a group etc. women in decision making would suggest that the changes in gender relations constitute a structural shift. Here we distinguish the structural/collective from the individual. Across recorded history, individual women may have been more powerful than individual men, but in no society were women as a group more powerful than men as a group. It stands to reason, therefore, that the involvement of larger numbers and proportions of women in decision making both reflects and reinforces the changes in gender relations as a structural shift, one characterized by the empowerment of women as a group .

As this chapter will demonstrate, women's participation in formal politics has been increasing, though in variable ways. There was, for example, a precipitous decline in the Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union following the collapse of communism and the emergence of liberal democracies in the early 1990s. In a number of regions, quotas — constitutional, electoral, and political party quotas — have been installed to ensure equitable representation by women. Women have been elected heads of government or state, and across the globe their proportion of parliamentary seats is about 18–20%. And yet, formidable obstacles remain, although these are being addressed by the global women's rights agenda, Footnote 2 women's movements, and some national governments. Today, feminist social scientists argue that a polity is not fully democratic when there is not adequate representation of women (Phillips 1991, 1995; Eschle 2000; Moghadam 2004). The Beijing Platform for Action (UN 1996, para 181) states that: “Achieving the goal of equal participation of women and men in decision- making … is needed in order to strengthen democracy and promote its proper functioning.”

If women's representation in the corridors of formal politics has been limited, their involvement in extraparliamentary politics has been extensive. Women have played important and visible roles in the great social revolutions (French, Russian, Chinese, Iranian), in Third World liberation and revolutionary movements (e.g., Vietnam, Algeria, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Northern Ireland, South Africa), and in all manner of social movements (e.g., the Civil Rights movement in the United States, and the peace, environmental, anti-nuclear, and animal rights movements). With few exceptions, women's roles were long unacknowledged in official histories or popular accounts. Since the 1970s, however, this historical amnesia and women's political marginalization have been corrected first by feminist scholarship across the disciplines (e.g., history, sociology, political science); secondly by the recog-nition of women as major political actors, voters, constituents, and candidates in numerous countries; and thirdly by the emergence of feminist movements, women's non governmental organizations (NGOs) of all kinds, and transnational feminist networks, along with the visibility of women leaders in the global justice movement. In turn, this contributes further to women's empowerment.

The literature has tended to view power in a largely negative way, that is, in terms of the power of some over others, or the capacity of the powerful to exert their will over those without power. Footnote 3 In the second edition of his classic study on power, political philosopher Steven Lukes (2005) argues for a broader definition of power that should not be limited to asymmetric power relations, and admits that not all power is negative and zero-sum. He updates his definition of power to include agents' abilities to bring about significant effects, specifically by furthering their own interests or affecting the interests of others, whether positively or negatively. Lukes' position parallels one argued by feminist scholars who emphasize the empowerment of previously marginalized or powerless people (Carroll 1972 ; di Marco 2005). In order for democracy to be broadened and deepened, Graciela di Marco argues, the norms, values, and social relations on which unequal power relationships are based must be deconstructed, delegitimized, and finally reconstructed in a democratic form. This requires the acquisition of women's authority in the polity, as well as in the family, the community, and the workplace. In other words, women's empowerment serves not only women as a group, but the entire society. It is essential to democratization and development as well as to gender equality.

In this connection, gendering democracy and political participation matters, in at least three ways. First, as Ann Phillips (1995) has explained, women have interests, experiences, values, and expertise that are different from those of men, due principally to their social positions. Thus, women must be represented by women. Second, if the core of democracy is the regular redistribution of power through elections, then attention must be paid to the feminist argument that gender is itself a site and source of power, functioning to privilege men over women, and to favor masculine traits, roles and values over feminine equivalents in most social domains. Footnote 4 Third, women are actors and participants in the making of a democratic politics. One can hypothesize a connection between women's participation and rights, on the one hand, and the building and institutionalization of democracy on the other. Evidence comes from Latin America and South Africa, where women's participation was a key element in the successful transitions. Footnote 5 Indeed, it has been suggested that the longstanding exclusion of women from political processes and decision making in the Middle East and North Africa may be key to understanding why the region has been a “laggard,” when compared with the other regions, in democratization's third wave (Moghadam 2004). Footnote 6 Attention to women's participation and rights, therefore, could speed up the democratic transition in the region.

Enabling Factors and Persistent Obstacles

Data from the fourth wave of the World Values Survey (WVS 1999—2004) — a large international dataset based on public opinion polls surveying attitudes toward women's participation and rights as well as an array of political and cultural issues — suggest a “rising tide” of gender equality transforming many aspects of men's and women's lives and cultural values. On the basis of their interpretation of the results of various waves of the World Values Survey, and in a new version of modernization theory, Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris ( 2003 ), who have been closely associated with the WVS, argue that the gender gap in political participation is often the greatest in poorer developing nations and often diminished or reversed in the post-industrial societies. Footnote 7 The more developed — indeed, post-industrial — a country, the more likely that value orientations in general, and gender equality norms in particular, move in an egalitarian direction. By extension, the more developed a country, the greater the likelihood of women's political representation and participation. Testing this hypothesis through international datasets reveals that the greater a country's human development (as measured, for example, by the UNDP's Human Development Index), the more likely that women are able to attain higher decision making positions (as measured by the Gender Development Index, or GDI and the Gender Empowerment Measure, or GEM). Footnote 8 Expanding further on this thesis, one could argue that the contemporary shift of the global economy toward a service and knowledge-based economy may be more conducive to women's involvement in decision making, inasmuch as it rewards educational attainment with well-remunerated opportunities for professional women. The world economy does not benefit all countries or citizens in the same way, but the “Fordist” regime of manufacturing and industrial production arguably was more advantageous to men as a group than to women as a group , in terms of economic participation and access to power.

By the same token, a country's adherence to “world culture” or the “world polity” creates a national and policy environment conducive to women's participation and rights (Paxton and Hughes 2007 ). When governments ratify international treaties and conventions, and when international organizations are present in countries, an enabling climate is created which affects an array of outcomes, including women's access to civil society, the public sphere, and leadership roles across domains.

At the same time, the data suggest a lag effect in the arena of political participation and representation. Women continue to be less politically active in most countries. Broad, longterm structural change is certainly a major determinant of women's political participation, but policy also matters. This is why some developing countries have higher rates of women's political participation in formal political structures than does the United States. The application of quotas — whether constitutional, policy party, or electoral quotas — explains why Argentina has a 35% female share of parliament, when compared with the 16% share found in the United States (data for 2008).

Besides quotas, other institutional changes and reforms are needed to expand women's public presence. Childcare centers, paid maternity leaves, and paternity leaves could level the playing field, allow women to catch up to men, and compensate for past marginalization and exclusion (Phillips 1995; Lister 1997). Research shows that women need to be at least a large minority to have an impact, and women's issues receive more support when women attain a “critical mass”. The UN now recommends a benchmark of at least 30% female representation.

Research and advocacy have thus focused on a number of factors enabling women to advance within organizations and social institutions, be these political parties, parliaments, or governments: the nature of legislative structures and electoral systems; the strength of civil society organizations; the adoption of women-friendly work policies; electoral quotas; and social capital and women's networking. The macro- and meso-level factors appear to work in tandem: the broad structural changes have resulted in a growing population of educated and employed women with the capacity to enter the political process or to organize and mobilize around specific grievances or goals; and women's movements and organizations lobby governments and advocate publicly for women-friendly policies, more rights, and equitable representation. At least two transnational feminist networks, along with numerous nationally based women's groups, have launched campaigns for gender parity in the political process globally. The Women's Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) joined forces with another U.S.-based international network, the Women's Learning Partnership for Development, Rights, and Peace (WLP) to launch the 50/50 campaign, whose objective is to increase the percentage of women in local and national politics worldwide to 50%. Since its inception in June 2000, the campaign has been adopted by 154 organizations in 45 countries (Paxton and Hughes 2007 : 179). Footnote 9

The confluence of the global women's rights agenda and women's movements has created a global opportunity structure conducive to the adoption of policies, programs, and resources in support of women's participation in decision making. And yet the persistence of obstacles and challenges cannot be denied. For many parts of the world, the chief macro-level barriers are economic, political, and cultural. Underdevelopment, poverty, and conflict are barriers to women's political participation, and prevent the creation of an adequate supply of women political actors or leaders. Gender-based gaps in educational attainment, employment, and income impede women's access to economic resources, creating obstacles to funding political campaigns. Another barrier lies in the nature of political systems: authoritarian regimes are more likely to be shaped by patriarchal norms and less likely to involve women in political participation. In such countries, discriminatory laws may prevent women from attaining leadership positions in governance. Social and cultural views about women in society — or traditional gender ideology — continue to exert a strong influence on women's access to leadership and decision making. The persistence of the sexual division of labor — as both ideology and a form of social organization — is remarkable, given women's increasing educational attainment and social participation. Family responsibilities are consistently cited as major stumbling blocks for women's career advancement in politics and in other domains, especially in the absence of adequate institutional policies.

Last but not the least, risks associated with public and leadership roles should be noted. In many countries, ascension to positions of power or public visibility carries with it various risks, from harassment and loss of privacy to physical attacks, kidnapping or assassinations. In the most conservative societies, women who dare to enter the public domain without conforming to certain patriarchal norms may face substantial risks.

Electoral Politics and Women'S Participation: Governments, Parliaments, and Parties

A large literature now exists that examines women's roles in formal politics, especially in national parliaments, and women's political participation and representation are measured in a number of international datasets, including those of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), the UNDP's Human Development Report , and the UN's statistical database, The World's Women: Trends and Statistics . Footnote 10 These datasets provide general support for the hypothesis linking women's political participation to high human development or to the application of quotas, at least since the early 1990s. Thus, the Nordic countries have consistently ranked highest in terms of both human development and women's political participation — and most of them also have adopted quotas to ensure women's participation in political parties, parliamentary elections, and cabinets. In contrast to the United States' 16–17% female parliamentary participation, the Nordic countries have had a roughly 41% female share for at least a decade and up to December 2008. Research on Latin America shows that the wave of national quota legislation since the 1990s improved women's political situation in some countries. In 2007, Argentina, the first country in the world to adopt a national quota law, led the region with 36% women in its lower house.

At the opposite end of the spectrum lie the countries of the Middle East and North Africa, with historically low levels of female participation in formal politics. The average 10% female representation is evidence of the masculine nature of the region's political processes and institutions. Yet even there, differentiation should be noted; according to IPU data for 2008, Tunisia had the highest female proportion in the region, with a 23% female share of parliamentary seats. Comparing Tunisia to other countries, Tunisia's share was higher than that of Uruguay and Chile (12%), Mexico (16%), the Philippines (18%), and Israel (13%), though lower than Argentina's (36%) or South Africa's (30%). Enabling factors in Tunisia included a relatively high rate of female labor force participation, the existence of strong women's organizations and networks, and a government that, while authoritarian, presents itself as a champion of women's rights (Moghadam 2003). Footnote 11

Elsewhere in the so-called Muslim world, variations in women's parliamentary representation suggest differences in political histories, social structures, and state policies; hence the disparate rates, as of 2008, of Azerbaijan (11.4%), Indonesia (11.6%), Tajikistan (17.5% lower house; 23.5% upper house), Pakistan (22.5%), and Nigeria (7.0%). Interestingly, Muslim women do better in the parliaments of the European democracies. Research by Melanie Hughes ( 2008 ) shows that while minority women's political representation is generally low across the globe, women of Muslim and especially North African extraction are over-represented in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Sweden. Among other factors, Hughes explains, quotas help the minority women.

The election of women as heads of state or government does not seem to follow any particular pattern. Of course, the Nordic countries have had strong representation of women at the highest levels of government, including president, prime minister, and cabinet members.

But, when one considers other women leaders — e.g., Indira Gandhi of India, Golda Meir of Israel, Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan, Violeta Chamorro of Nicaragua, Margaret Thatcher of the United Kingdom, Tansu Ciller of Turkey, or Gloria Arroyo of the Philippines — there appears to be no correlation with economic/human development or the strength of the women's movement. Instead, such women leaders come up the ranks through dynastic family connections (Gandhi, Bhutto, Chamorro) or through exceptional pathways in a political party (Meir, Thatcher, Ciller, Arroyo). On the other hand, the election of women presidents in Finland, Ireland, Chile, and Sierra Leone is at least partially explained by the strength of women's mobilizations in those countries, along with the prominence of the individual women elected as leaders. Increasingly, one observes prominent women in political party leadership, from Segolène Royale, who was the French Socialist Party's presidential candidate in 2006, to Louisa Hanoun, who leads the Socialist Workers' Party in Algeria and has been her party's presidential candidate. In the United States, Hillary Clinton's attempt to be the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in 2008 reflected a number of influences: family ties (her husband was former president Bill Clinton), white women's mobilizations, and her own record as senator from New York.

The arena of local governance and of women's roles within it is less researched than that of the national politics and governance. Participation of women in local governance is important, however, because decisions are made regarding everything from taxation and social spending to quality of life, including local schools, street lighting, housing, sanitation, zoning, transport, and policing. These are decisions that directly affect women, children, men, and families; as such, it is important that women be well represented. Data collected by the United Cities and Local Governments, a network created at a meeting in the Republic of Korea in 2004, suggest that women are largely excluded from mayoralties, though they do better as local councilors. Footnote 12 Other sources of data for participation in local governance come from the United Nations' regional commissions and from the country reports submitted to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. Footnote 13

Some countries show a large gap between women's representation in local and national governance. In South Korea, women's participation in local governance is almost negligible; the 2002 local elections resulted in a 3.1% female share in the regional councils and a 1.9% female share in the city/county/district councils. In contrast, at the national level, women were 13.7% of those elected to the 2004–2008 National Assembly. Footnote 14 In Brazil, between 1999 and 2003, just one out of 27 Governors was a woman (4%), and between 1997 and 2001, some 303 out of 2,205 mayors were women (3.4%). In 2000, just 11% of municipal councils in Brazil were made up of women (Htun 2000 ). At the national level in 2008, Brazilian women had 9% of parliamentary seats in the lower house and 12.3% in the upper house.

Available data for Sub-Saharan Africa shows high levels of women's representation in local governance in South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda, which are consistent with their national-level representation and appear to be related to the presence of quotas. In Tanzania, for example, women constituted 35.5% of councilors at the local level in 2004. At the federal level, their share was 30.4%. In both cases, high representation was the result of “special seats” reserved for women. Footnote 15

Among the Arab countries, while a growing number of women are running for local (as well as national) office, only Tunisia and Yemen appear to have registered a significant female presence in the local governance. In Yemen's first-ever local elections held in February 2001, some 120 women ran as candidates with 35 winning seats, representing a surprising 29% female share in this conservative and low-income country. Footnote 16 In 2004, Tunisia's female share of municipal seats was about 20%. Footnote 17

Elsewhere in the Middle East, Iran appears to be one case whereby women are more active at the municipal than at the national level. While women occupy only 8 out of 286 parliamentary seats, or a mere 2.8% share, the municipal elections of December 2007 brought more than 5,000 women to local governance in about 3,300 councils across the country. Women did exceptionally well, and better than male candidates, in Shiraz, Arak, Hamedan, Zanjan, and Ardebil; and they won a large number of seats in Urumiyeh and Qazvin (Ghammari, 2008 ).

India represents a striking example of high female representation in local governance, due to a 33% “reservation” or quota that was established for women's participation across Indian states. While efforts to achieve reserved seats at India's state and national levels have stalled, two constitutional amendments passed in 1992 require that one-third of all seats in both rural and urban councils must be filled by women. The 73rd Amendment also granted more powers over governmental services and projects to the three tiers of the rural councils — panchayats , at the village, block and district level (Nanivadekar 2005 ). Footnote 18 While most Indian states have at least 33% women as a direct consequence of reservation, some states have even exceeded the 33% quota. Footnote 19 In 2005, Karnataka had a representation as high as 45%, 42% and 38% in the village, taluk/block and district panchayats respectively. In Kerala and West Bengal, 35–36% of elected women representatives at the local bodies were women. In Uttar Pradesh, 54% of the Zilla Parishad Presidents, and in Tamil Nadu, 36% of the Chairpersons of Gram Panchayats were women. Footnote 20 In contrast, the female share of parliamentary seats at the federal level was just 9.1% in 2008.

In Europe, data for the period 2000–2005 from the Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) show that only in Moldova is women's participation at the local governance level very high — and at 57%, perhaps the highest in the world. In Latvia, Finland, Norway, and France, women represent 30–42% of municipal councils and local governing bodies. Everywhere else, for which there are data, the figures are below 30%.

Given the data inadequacies, it is difficult to draw conclusions about women's participation in local governance. The world average for women's parliamentary representation is 21% (IPU, circa 2008) and for women councilors it is similarly 21% (UCLG, circa 2003–2004). Regionally, women are less represented at the local than the national level in the Middle East and North Africa (2.1% versus 9.7% female shares), and in the Nordic countries (Finland has the highest percentage of women councilors, but at 34% it is less than the Nordic parliamentary average of 41% female share). For other regions there appears to be more symmetry, although it may be the case that in sub-Saharan Africa, women are actually better represented at the local level than at the national (as Fallon (2008) found for Ghana), at least as far as councilors are concerned. This is clearly an area that requires further investigation

Women in Movement: Civil Society, Transnational Networks, and Democratic Transitions

The arena of civil society is a democratic space for the flourishing of associational life that also acts as a buffer between the citizenry, on the one hand, and the state and the market on the other. This is where much of women's modern public activity and their “social capital” have been observed, in charities, churches/religious institutions, parent-teacher associations, neighborhood clubs, and local initiatives. In recent decades, the exponential growth of women's presence in various NGOs, professional associations, and of course women's organizations has seen significant collective impacts, as women's organizations have become highly effective pressure groups. Civil society experience can be a pathway to senior positions in other domains, including national and local governance. And increasingly, women are found in what has become known as the sphere of global civil society, as they have become politically active in social movements, international organizations, and advocacy networks of all kinds.

Using World Values Survey data, Inglehart and Norris ( 2003 , Table 5.2) show that women's participation in civic associations exceeds that of men. Reported participation rates are 53% female and 47% male (data for 2001 ). Those where women are 50% or more are the following: conservation, environment or animal rights; third world development or human rights; education, arts, music or cultural activities; religious or church organizations; voluntary organizations concerned with health; social welfare for the elderly, handicapped, or deprived people; women's groups. Women make up between 42 and 49% of members of peace movements, professional associations, labor unions, local community action groups, and groups working with youth.

Feminist scholars of the Middle East and North Africa have analyzed the “gradual feminization of the public sphere” and have noted the growing involvement of women in an array of civic associations (Moghadam and Sadiqi 2006 ). Footnote 21 Seven types of women's organizations have been identified: women-led charitable associations; women's wings of political parties; professional associations (e.g., associations of women lawyers); development research centers and women's studies institutes; development and service-delivery NGOs; women's rights organizations; worker-based women's organizations associated with trade unions (Moghadam 1998). Examples are feminist organizations such as l'Association Tunisienne des Femmes Démocrats, l'Association Démocratique des Femmes Marocaines (ADFM), Algeria's SOS Femmes en Détresse, Iran's Cultural Center for Women and the Change for Equality Campaign, and Turkey's Women for Women's Human Rights International; development NGOs such as Egypt's Association for the Development and Enhancement of Women (ADEW); think tanks such as CAWTAR and CREDIF of Tunisia, and the Palestinian Women's Research and Documentation Center; and women's studies centers and institutes at universities such as Birzeit in Ramallah, the West Bank; the Lebanese American University in Beirut; and the Middle East Technical University in Ankara, Turkey. As a whole, these groups and units engage in research and advocacy for egalitarian family laws, nationality rights for women, criminalization of domestic violence, greater economic participation, and political rights.

A major objective of Lebanese women's organizations has been increased political representation in parliament. Jordanian women have protested impunity of men in the so-called honor killings. Turkish women leaders in civil society secured amendments to the Civil Code and protested loudly when the government wanted to return adultery to the criminal code. Egyptian women's groups campaigned for the issuance of individual identity cards for women and for women's right to a khul divorce. Footnote 22 In 2008 a major campaign revolved around sexual harassment of women in the streets, with women's groups insisting on prosecution. Iranian feminists seek an overhaul of the penal code and an end to the punishment of stoning for adultery. They also desire what their sisters in Morocco obtained in 2004, which was a more egalitarian family code. The One Million Signature Petition drive, so important to the Moroccan women's movement in the early 1990s, has been adopted in Iran as well (Joseph 2000; Moghadam 2003; Naciri 2003 ). In demanding an end to discrimination, gender inequality, and human rights violations, such women's groups draw on what we might call world values (including the global women's rights agenda) as well as their own cultural understandings.

In the countries of the Persian Gulf, where women have been long excluded from political decision making, there has been a significant increase in women's NGO leadership roles. In turn, these roles have led to engagement with the political process. Research on Kuwait has shown that women's networking and involvement in professional associations is a strong predictor of engagement with the political process (Meyer et al. 2002 ).

In some cases, the growth of women's participation in NGOs is the result of state or development failures. Mary Osirim ( 2001 ) discusses the important role of women's NGOs in Zimbabwe in addressing women's social welfare and human rights concerns — in particular, HIV/ AIDS and gender-based violence — and in establishing social networks as a way to empower women in an otherwise untoward economic and political situation. Despite the increasing participation of women in civic associations throughout the world, decision making roles outside of women's own organizations remains largely the province of men. This is especially poignant in countries where women played important roles in the democratic transitions. Sociologist Seungsook Moon ( 2002 ) documents the marginalization of South Korean women from civil society leadership, despite the important roles they played in the 1970s labor movement and the 1980s democracy movement. In the Philippines, women's NGOs were active in the anti dictatorship movement of the 1970s and 1980s and thus assumed an important role in the post-Marcos period in shaping the state policies to further women's status and rights. When aid agencies entered the country after Marcos, women's NGOs were already prominent and well placed to access official ODA and to take the lead in a number of civil society organizations, including women's organizations (Angeles 2003 ). However, a mixed picture emerges with respect to professional associations and the other civic associa-tions. Footnote 23

Despite the obstacles, women civil society leaders have become agenda setters, inserting feminine voices and women's issues onto the public sphere. Along with the increase in women's parliamentary representation, women's civic activism has led in some cases to changes in the “gendered balance of power”. For example, in South Africa, many women involved in the anti-apartheid struggle went on to leadership roles in local and national government and in the judiciary. In Rwanda, after the war and the 1994 genocide subsided, activist women were well positioned to assume leadership and decision making roles (Paxton and Hughes 2007 : 170). In many Latin American countries, electoral quotas and legislation on domestic violence have followed women's civic activism. In Northern Ireland, the Women's Coalition entered the political process, and the other political parties adopted quotas for gender parity. In Algeria, the feminist movement that emerged in the 1980s first to protest the government's introduction of a new and very conservative Muslim family law and then to oppose the rising Islamist movement went on to demonstrate remarkable resilience during the 1990s civil conflict and terrorist campaigns. For this, activist women were rewarded in the summer of 2002 with an unprecedented five cabinet posts, representing 25% of cabinet seats at the time (Moghadam 2003).

The arena of conflict, peace, and security — long considered a male domain — has seen notable interventions by women's groups. Of course, women have been long involved in peace movements. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was founded in 1915 by 1,300 women activists from Europe and North America opposed to what became known as World War I (Enloe 2007 : 14). Two WILPF leaders were awarded Nobel Peace Prizes: Jane Addams in 1931 and Emily Greene Balch in 1946. WILPF remains active to this day, and recently formed PeaceWomen as an information and monitoring website — a form of virtual activism — on women, peace, and security issues. Footnote 24 The activities of anti-militarist and human rights groups such as WILPF, Women Strike for Peace (U.S.), the Women of Greenham Common (U.K.), and the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Argentina) are well known. Research has documented women-led peace initiatives in Northern Ireland (for which Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan received the Nobel Peace Prize), Bosnia and Herzegovina (which saw activism by Women in Black), Israel-Palestine (through the Jerusalem Link as well as Women in Black), and Rwanda (through the Rwandan Women's Network) (Moghadam 2007). In the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, women were both the majority of peace activists and the first to lead protests against the war (Hunt 2004; Paxton and Hughes 2007 : 170). In Burundi, women's presence at the Arusha peace talks was facilitated by Nelson Mandela; in Northern Ireland, the Women's Coalition, which crossed sectarian lines to press for peace, took part in the first post-conflict elections (Fearon 1999; Burke 2001). In the 1990s and into the new millennium, transnational feminist networks such as Women for Women International emerged to focus on conflict, peace, and security. After the invasion of Iraq, anti war U.S. women took leading roles in new peace movements and organizations, such as United for Peace and Justice, and they created Code Pink: Women for Peace. Other important transnational feminist networks working on conflict, peace, and security issues are MADRE, the Women's Learning Partnership for Rights, Development, and Peace (WLP), and the newly formed Nobel Women's Initiative (Moghadam 2009 ).

The role of women and feminist issues in the global justice movement and the World Social Forum (WSF) has been the subject of some discussion (Eschle 2005 ; Vargas 2005 ; Moghadam 2009 ). Studies now show that women are probably the majority of attendees at the WSF, and that the Feminist Dialogues attract a large number of participants. Transnational feminist networks such as DAWN and the Marche Mondiale des Femmes are among those represented on the WSF's International Council. The global justice movement and the WSF is known at least partially for their prominent women, including Arundhati Roy, Vandana Shiva, Naomi Klein, Virginia Vargas, Susan George, and Medea Benjamin. In calling for peace, economic justice, women's human rights, and human development, the women of the global justice movement also help to engender the path to global democracy.

Engendering Democracy

Historically, paths to democracy have differed, and, as Barrington Moore (1966) showed, there were varied and divergent paths in the Western world. Moore famously identified a modernizing — or revolutionary — bourgeoisie as key to the advent and sustainability of democracy. Even so, democratization was a slow, gradual process in the Western world. In the United States, for example, democracy was enjoyed first by property-owning white males, then extended to all men, and finally to women. In the southern states, blacks remained disenfranchised until well into the second half of the twentieth century, when the civil rights movement and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended the infamous Jim Crow laws that prevented American blacks from exercising political rights of citizenship. By that time, most of the world's women had received formal political rights, that is, the right to vote and stand for elections; in terms of international law, this was codified in the 1954 UN Convention on the Political Rights of Women. However, women remained a small proportion of those who enjoyed the benefits of democracy, such as political participation and representation. Moreover, despite the political rights, the gap between formal and substantive equality has been large — and especially large for women.

Democracy is assumed to serve women well, but the historical record shows that democratic transitions do not necessarily bring about women's participation and rights. Relevant examples are Eastern Europe in the early 1990s; Algeria and the elections that brought about an Islamist party (FIS) in 1990/1991; and Iraq and the Palestinian Authority, where elections in early 2006 brought to power governments committed more to religious norms than to citizen or women's rights. One reason for this “gender-based democratic deficit” is that existing definitions and understandings of democracy tend to focus on procedures and institutions. Liberal democracy is the model that is being touted in the contemporary era of globalization, as it is presumed to be the most compatible with liberal capitalism. Here, a high degree of political legitimacy is necessary, as is an independent judiciary and a constitution that clearly sets out the relationship between state and society, and citizen rights and obligations. In practice, however, “democracy” is often equated with “free and fair elections”. The problem is twofold. First, the distribution of political resources or power through competitive elections is an overly narrow definition of democracy; it obscures the importance of institutions, state capacity, and constitutional guarantees of rights no matter which party wins an election. Secondly, it occludes the gendered nature of politics and the longstanding exclusion of half the population. “Free and fair elections” may perpetuate the inequitable representation. Footnote 25

When and where are women's interests served by democratization, and democratization served by women's participation? Democratic transitions, like other types of social change, are influenced by internal and external factors and forces. How women fare during and after the transition similarly depends on a number of factors, including social structure, collective action, and the dominant ideology. Drawing on the gender and revolution literature (Moghadam 1997; Kampwirth 2002; Shayne 2004), one can identify the following: pre-existing gender relations and women's legal status and social positions before the transition; the extent of women's mobilizations before and during the transition, including the number and type of women's organizations and other institutions; the ideology, values, and norms of the ruling group; and the state's capacity and will to mobilize resources for rights-based development. This analysis finds its complement in Georgina Waylen's ( 2005 , 2007) discussion of key variables shaping women's experiences with democratic transitions: the nature of the transition; the role of women activists; the nature of the political parties and politicians involved in the transition; and the nature and institutional legacy of the non-democratic regime. In addition, research has found that party-list proportional representation systems, and countries where one of the primary political parties is leftist, have significantly more women in political decision making positions (Htun 2000 ; Paxton and Hughes 2007 ).

World polity theory can be helpful in explaining the salience of external factors: transnational links or the promotion of women by international organizations, for example, can positively affect the gender outcomes. World polity research has demonstrated that connections to the world society, which may be measured through treaty ratification or through the presence of international NGOs, impact a range of state-level outcomes including women's political citizenship (Ramirez et al. 1997 ).

These factors may help explain the variable outcomes for women in a number of democratic transitions. In Latin America, women's movements and organizations played an important role in the opposition to authoritarianism and made a significant contribution to the “end of fear” and the inauguration of the democratic transition. Here, women organized as feminists and as democrats, but also as mothers of the disappeared, and often allied themselves with left-wing parties. Especially in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, women's groups met, marched, and demonstrated for human rights, women's rights, and democracy. Though they were not the key actors in the negotiated transitions, they received institutional rewards when democratic governments were set up and their presence in the new parliaments increased. As Jane Jaquette ( 2001 : 114) observes:

“[F]eminist issues were positively associated with democratization, human rights, and expanded notions of citizenship that included indigenous rights as well as women's rights. This positive association opened the way for electoral quotas and increased the credibility of women candidates, who were considered more likely to care about welfare issues and less corrupt than their male counterparts.”

In contrast, East European women were not able to influence the transition and lost their key rights, as well as levels of representation, when the democratic governments were set up (Heinen 1992 ; Matland and Montgomery 2003). East European feminists coined the terms “male democracy” and “democratization with a male face” to describe the outcome of the transition from communism to liberal democracy, when women's representation in parliaments dropped dramatically from an average of 30% to 8–10%. The East European case showed that liberal democracy is not necessarily women-friendly and could in fact engender a male democracy, privileging men and limiting women's representation and voice. Although women had been mobilized before and during the transitions, the dominant ideology of the opposition movements and the new states were not consistent with an expanded definition and inclusive form of democracy.

In Algeria, the quick transition unsupported by strong institutions did not serve women well. Algeria had been ruled by a single party system in the “Arab socialist” style since its independence from France in 1962. The death of President Boumedienne in December 1978 brought about political and economic changes, including the growth of an Islamist movement that was intimidating unveiled women, and a government intent on economic restructuring. The urban riots of 1988 were followed quickly by a new constitution and elections, without a transitional period of democracy building. The electoral victory of the Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) alarmed Algeria's feminist organizations. That the FIS went on to initiate an armed rebellion when it was not allowed to assume power following the 1991 elections only confirmed the violent nature of that party (Bennoune 1995; Cherifati-Merabtine 1995; Messaoudi and Schemla 1995; Moghadam 2001).

A more positive example comes from Morocco, where women's groups were central actors in the country's democratization during the 1990s. Indeed, the feminist campaigns for the reform of family laws, which began in the early 1990s, should be regarded as a key factor in the country's gradual liberalization during that decade. When Abdelrahman Yousefi, a socialist and former political prisoner, was appointed prime minister in 1998 and formed a progressive cabinet, women's groups allied themselves to the government with the goal of promoting both women's rights and a democratic polity (Sadiqi and Ennaji 2006 ; Skalli 2007 ). Footnote 26 Subsequently, Moroccan feminist organizations strongly endorsed the truth and justice commissions that were put in place to examine the years of repression. A number of Moroccan women leaders previously associated with left wing political groups (e.g., Latifa Jbabdi) gave testimony about physical and sexual abuse (Slyomovics 2005). In Morocco, these developments have enhanced the prominence of women activists. More generally, the Moroccan case confirms the democratic nature of women's movements.

Another positive example comes from Turkey. In the 1980s, at a time when Turkey's civil society was under tight military control, the new feminist movement helped to usher in democratization through campaigns and demands for women's rights, participation, and autonomy (Arat 1994 ). The important role of women in the anti-apartheid and democratic movement of South Africa is yet another historic example (Tripp 2001 ). In South Africa as well as in Northern Ireland, Burundi, and Rwanda, women's roles in the democratic transitions were acknowledged and rewarded with political party quotas, gender budgets, and well-resourced women's research and policy centers. In turn, such initiatives to support and promote women's participation and rights reinforce and institutionalize the democratic institutions.

Women, Gender and Politics in the Middle East

There is a lively debate among political scientists regarding the relations among Islam, attitudes toward women and gender equality, and the democracy deficit. The World Values Survey's fourth wave included a number of Muslim-majority countries, and among its principal findings were high support for democracy and for Islam, but low support for gender equality. Footnote 27 The Muslim Brothers of Egypt, for example, call for “the freedom of forming political parties” and “independence of the judiciary system”, but they also call for “conformity to Islamic Sharia Law,” which is not conducive to gender equality or the equality of Muslim and non Muslim citizens in all domains (Brown, Hamzawy, and Ottaway 2006).

Commentators emphasize the need to establish “the core of democracy — getting citizens the ability to choose those who hold the main levers of political power and creating checks and balances through which state institutions share power” (Carothers and Ottaway 2005: 258). Such commentators envisage a scenario in which political parties are allowed to form and compete with each other in elections, and they have focused on the participation (and transformation) of Islamist parties as key to the transition to democracy. However, they tend to overlook what are in fact a key constituency, a natural ally, and social base of a democratic politics — women and their feminist organizations. In the Arab region and Iran, questions of democratization and questions of women's rights have emerged more or less in tandem. They are closely intertwined and mutually dependent, and the fate of one is closely bound to the fate of the other. There are at least two reasons for this claim.

One is that women in MENA — and especially the constituency of women's rights advocates — are the chief proponents of democratic development and of its correlates of civil liberties, participation, and inclusion. The region's feminists are among the most vocal advocates of democracy, and frequently refer to themselves as part of the “democratic” or “modernist” forces of society. For example, a Tunisian feminist lawyer has said: “We recognize that, in comparison with other Arab countries, our situation is better, but still we have common problems, such as an authoritarian state. Our work on behalf of women's empowerment is also aimed at political change and is part of the movement for democratization.” Footnote 28 In 2008, a prominent Tunisian feminist organization, AFTURD, issued a statement declaring “that no development, no democracy can be built without women's true participation and the respect of fundamental liberties for all, men and women.” Footnote 29

A second reason is that women have a stake in strong and sustainable democracies, but — as we have seen — they can be harmed by weak or exclusionary political processes. Women can pay a high price when a democratic process that is institutionally weak, or is not founded on principles of equality and the rights of all citizens, or is not protected by strong institutions, allows a political party bound by patriarchal norms to come to power and to immediately institute laws relegating women to second class citizenship. This was the Algerian feminist nightmare, which is why so many educated Algerian women opposed the FIS after its expansion in 1989. Thus, Middle Eastern feminists are aware that they can be harmed by an electoral politics that occurs in the absence of a strong institutional and legal framework for women's civil, political, and social rights of citizenship. Hence, their insistence on egalitarian family laws, criminalization of domestic violence, and nationality rights for women — along with enhanced employment and political participation.

There is evidence that women, and more precisely employed women, have different political preferences from men, with a tendency to vote in a more leftward direction, in particular supporting public services (Manza and Brooks 1998 ; Huber and Stephens 2000 ; Inglehart and Norris 2003 ). A plausible connection also may be made between the sustained presence of a “critical mass” of women in political decision making and the establishment of stable and peaceful societies. If the Nordic model of high rates of women's participation and rights correlates with peaceful, prosperous, and stable societies, could the expansion of women's participation and rights in the Middle East also lead the way to stability, security, and welfare in the region, not to mention an effective democratic governance?