Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 June 2024

Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance

- Nicholas Bloom ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1600-7819 1 na1 ,

- Ruobing Han ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9126-5503 2 na1 &

- James Liang 3 , 4

Nature volume 630 , pages 920–925 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

753 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Research management

Working from home has become standard for employees with a university degree. The most common scheme, which has been adopted by around 100 million employees in Europe and North America, is a hybrid schedule, in which individuals spend a mix of days at home and at work each week 1 , 2 . However, the effects of hybrid working on employees and firms have been debated, and some executives argue that it damages productivity, innovation and career development 3 , 4 , 5 . Here we ran a six-month randomized control trial investigating the effects of hybrid working from home on 1,612 employees in a Chinese technology company in 2021–2022. We found that hybrid working improved job satisfaction and reduced quit rates by one-third. The reduction in quit rates was significant for non-managers, female employees and those with long commutes. Null equivalence tests showed that hybrid working did not affect performance grades over the next two years of reviews. We found no evidence for a difference in promotions over the next two years overall, or for any major employee subgroup. Finally, null equivalence tests showed that hybrid working had no effect on the lines of code written by computer-engineer employees. We also found that the 395 managers in the experiment revised their surveyed views about the effect of hybrid working on productivity, from a perceived negative effect (−2.6% on average) before the experiment to a perceived positive one (+1.0%) after the experiment. These results indicate that a hybrid schedule with two days a week working from home does not damage performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Using games to understand the mind

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

Principal component analysis

Working from home (WFH) surged after the COVID-19 pandemic, with university-graduate employees typically WFH for one to two days a week during 2023 (refs. 2 , 6 ). Previous causal research on WFH has focused on employees who are fully remote, usually working on independent tasks in call-centre, data-entry and helpdesk roles. This literature has found that the effects of fully remote working on productivity are often negative, which has resulted in calls to curtail WFH 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 . However, there are two challenges when it comes to interpreting this literature. First, more than 70% of employees WFH globally are on a hybrid schedule. This group comprises more than 100 million individuals, with the most common working pattern being three days a week in the office and two days a week at home 2 , 8 , 9 . Second, most employees who are regularly WFH are university graduates in creative team jobs that are important in science, law, finance, information technology (IT) and other industries, rather than performing repetitive data-entry or call processing tasks 10 , 11 .

This paper addresses the gap in previous studies in two key ways. First, it uses a randomized control trial to examine the causal effect of a hybrid schedule in which employees are allowed to WFH two days per week. Second, it focuses on university-graduate employees in software engineering, marketing, accounting and finance, whose activities are mainly creative team tasks.

Our study describes a randomized control trial from August 2021 to January 2022, which involved 1,612 graduate employees in the Airfare and IT divisions of a large Chinese travel technology multinational called Trip.com. Employees were randomized by even or odd birthdays into the option to WFH on Wednesday and Friday and come into the office on the other three days, or to come into the office on all five days.

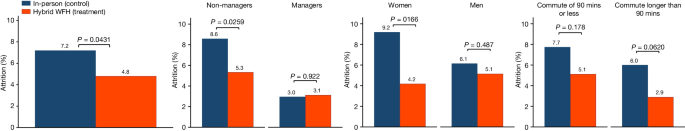

We found that in the hybrid WFH (‘treatment’) group, attrition rates dropped by one-third (mean control = 7.20, mean treat = 4.80, t (1610) = 2.02, P = 0.043) and work satisfaction scores improved (mean control = 7.84, mean treat = 8.19, t (1343) = 4.17, P < 0.001). Employees reported that WFH saved on commuting time and costs and afforded them the flexibility to attend to occasional personal tasks during the day (and catch up in the evenings or weekends). These effects on reduced attrition were significant for non-managerial employees (mean control = 8.59, mean treat = 5.33, t (1215) = 2.23, P = 0.026), female employees (mean control = 9.19, mean treat = 4.18, t (568) = 2.40, P = 0.017) and those with long (above-median) commutes (mean control = 6.00, mean treat = 2.89, t (609) = 1.87, P = 0.062).

At the same time, we found no evidence of a significant effect on employees’ performance reviews, on the basis of null equivalence tests, and no evidence of a difference in promotion rates over periods of up to two years (‘Null results’ section of the Methods ). We did find significant differences in pre-experiment beliefs about the effects of WFH on productivity between non-managers and managers. Before the experiment, managers tended to have more negative views, reporting that hybrid WFH would be likely to affect productivity by −2.6%, whereas non-managers had more positive views (+0.7%) ( t (1313) = −4.56, P < 0.001). After the experiment, the views of managers increased to +1.0%, converging towards non-managers’ views (mean non-manager = 1.62, mean manager = 1.05, t (1343) = −0.945, P = 0.345). This highlights how the experience of hybrid working leads to a more positive assessment of its effect on productivity—consistent with the overall experience in Asia, the Americas and Europe throughout the pandemic, where perceptions of WFH improved considerably 13 .

The experiment

The experiment took place at Trip.com, the third-largest global travel agent by sales in 2019. Trip.com was established in 1999, was quoted on NASDAQ in 2003 and was worth about US$20 billion at the time of the experiment. It is headquartered in Shanghai, with offices across China and internationally, and has roughly 35,000 employees.

In the summer of 2021, Trip.com decided to evaluate the effects of hybrid WFH on the 1,612 engineering, marketing and finance employees in the Airfare and IT divisions, spanning 395 managers and 1,217 non-managers. All experimental participants were surveyed at baseline, with questions on expectations, background and their interest in volunteering for early participation in the experiment. The firm randomized employees with an odd-number birthday (born on the first, third, fifth and so on day of the month) into the treatment group.

Figure 1 shows two pictures of employees working in the office to highlight three points. First, in the second half of 2021, COVID incidence rates in Shanghai were so low that employees were neither masked nor socially distanced at the office. Although the COVID pandemic had led to lockdowns in early 2020 and during 2022, during the second half of 2021, Shanghai employees were free to come to work, and typically were unmasked in the office. Second, employees worked in modern open-plan offices in desk groupings of four or six colleagues from the same team, reflecting the importance of collaboration. Third, the office is a large modern building, similar to many large Asian, European and North American offices.

Pictures of Trip.com employees in the office during the experiment. The people in the experimental sample are typically in their mid-30s, and 65% are male. All of them have a university undergraduate degree and 32% have a postgraduate degree, usually in computer science, accounting or finance, at the master’s or PhD level. They have 6.4 years tenure on average and 48% of employees have children (Extended Data Table 1 ).

Effects on employee retention

One key motivation for Trip.com in running the experiment was to evaluate how hybrid WFH affected employee attrition and job satisfaction. The net effect was to reduce attrition over the experiment by 2.4%, which against the control-group base of 7.2% was a one-third (33%) reduction in attrition (mean control = 7.20, mean treat = 4.80, t (1610) = 2.02, P = 0.043). Consistent with this reduction in quit rates, employees in the treatment group also registered more positive responses to job-satisfaction surveys (mean control = 7.84, mean treat = 8.19, t (1343) = 4.17, P < 0.001). Employees were anonymously surveyed on 21 January 2022, and employees in the treatment group showed significantly higher scores on a scale from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest) in ‘work–life balance’, ‘work satisfaction’, ‘life satisfaction’ and ‘recommendation to friends’, and significantly lower scores in ‘intention to quit’ (Extended Data Table 2 ).

One possible explanation for the lower quit rates in the treatment group is that quit rates in the control group increased because the individuals in this group were annoyed about being randomized out of the experiment. However, quit rates in the same Airfare and IT divisions were 9.8% in the six months before the experiment—higher than the rate for the control group during the experimental period. Quit rates over the experimental period in the two other Trip.com divisions for which we have data (Business Trips and Marketing) were 10.5% and 9.8%—again higher than that for the control group during the experimental period. This suggests that, if anything, the control-group quit rates were reduced rather than increased by the experiment, possibly because some of them guessed (correctly) that the policy would be rolled out to all employees once the experiment ended.

Figure 2 shows the change in attrition rates by three splits of the data. First, we examined the effect on attrition for the 1,217 non-managers and 395 managers separately. We saw a significant drop in attrition of 3.3 percentage points for the non-managers, which against a control-group base of 8.6% is a 40% reduction (mean control = 8.59, mean treat = 5.33, t (1215) = 2.23, P = 0.026). By contrast, there was an insignificant increase in attrition for managers (mean control = 2.96, mean treat = 3.13, t (393) = −0.098, P = 0.922). We also found that non-managers were more enthusiastic before the experiment, with a volunteering rate of 35% (versus 22% for managers), matching the media sentiment that although non-managerial employees are enthusiastic about WFH, many managers are not ( t (1610) = 4.86, P < 0.001).

Data on 1,612 employees’ attrition until 23 January 2022. Top left, all employees. Only 1,259 employees filled out the baseline survey question on commuting length, so the commute-length (two ways) sample is for 1,259 employees. Sample sizes are 820 and 792 for control and treatment; 1,217 and 395 for non-managers and managers; 570 and 1,042 for women and men; and 648 and 611 for short and long commuters, respectively. Two-tailed t -tests for the attrition difference within each group between the control and treatment groups are (difference = 2.40, s.e. = 1.18, confidence interval (CI) = [0.0748, 4.72], P = 0.043) for all employees; (difference = 3.26, s.e. = 1.46, CI = [0.392, 6.12], P = 0.026) for non-managers; (difference = −0.169, s.e. = 1.73, CI = [−3.57, 3.23], P = 0.922) for managers; (difference = 5.01, s.e. = 2.08, CI = [0.915, 9.10], P = 0.017) for women; (difference = 0.997, s.e. = 1.43, CI = [−1.82, 3.81], P = 0.487) for men; (difference = 2.61, s.e. = 1.93, CI = [−1.19, 6.41], P = 0.178) for employees with median (90 min, two-way) or shorter commutes; and (difference = 3.11, s.e. = 1.66, CI = [−0.156, 6.37], P = 0.062) for above-median (90 min, two-way) commuters.

Second, we examined the effect on attrition by total commute length, splitting the sample into people with shorter and longer total commutes on the basis of the median commute duration (two-way commutes of 1.5 h or less versus those exceeding 1.5 h, with 648 and 611 employees, respectively). We found that there was a larger reduction in quit rates (52%) for those with a long commute (mean control = 6.00, mean treat = 2.89, t (609) = 1.87, P = 0.062). The reduction in quit rates was similarly large for employees with a long commute if we instead defined a long commute as a two-way commute time exceeding 2 h (mean control = 7.33, mean treat = 1.89, t (307) = 2.31, P = 0.021). Employees who volunteered to take part in the experiment had longer one-way commute durations (Extended Data Table 3 ; mean non-volunteer = 0.80, mean volunteer = 0.89, t (1257) = −3.68, P < 0.001). This is not surprising given that the most frequently cited benefit of WFH is no commute 1 .

Third, we examined the effect on attrition by gender, examining the 570 female and 1,042 male employees separately. We found that there was a 54% reduction in quit rates for female employees (mean control = 9.2, mean treat = 4.2, t (568) = 2.40, P = 0.017). For male employees, there was an insignificant 16% reduction in quit rates (mean control = 6.15, mean treat = 5.15, t (1040) = 0.70, P = 0.487). This greater reduction in quit rates among female individuals echoes the findings of previous studies 6 , 14 , 15 , 16 , which suggest that women place greater value on remote work than men do. Notably, although the treatment effect of WFH was significantly larger for female employees, volunteers were less likely to be female (mean non-volunteer = 0.37, mean volunteer = 0.32, t (1610) = −2.02, P = 0.043); this might suggest that women have greater concerns about negative career signalling by volunteering to WFH.

Employee performance and promotions

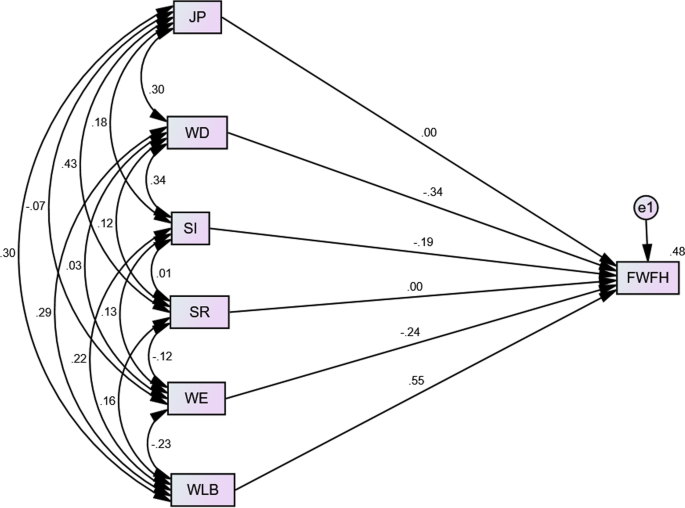

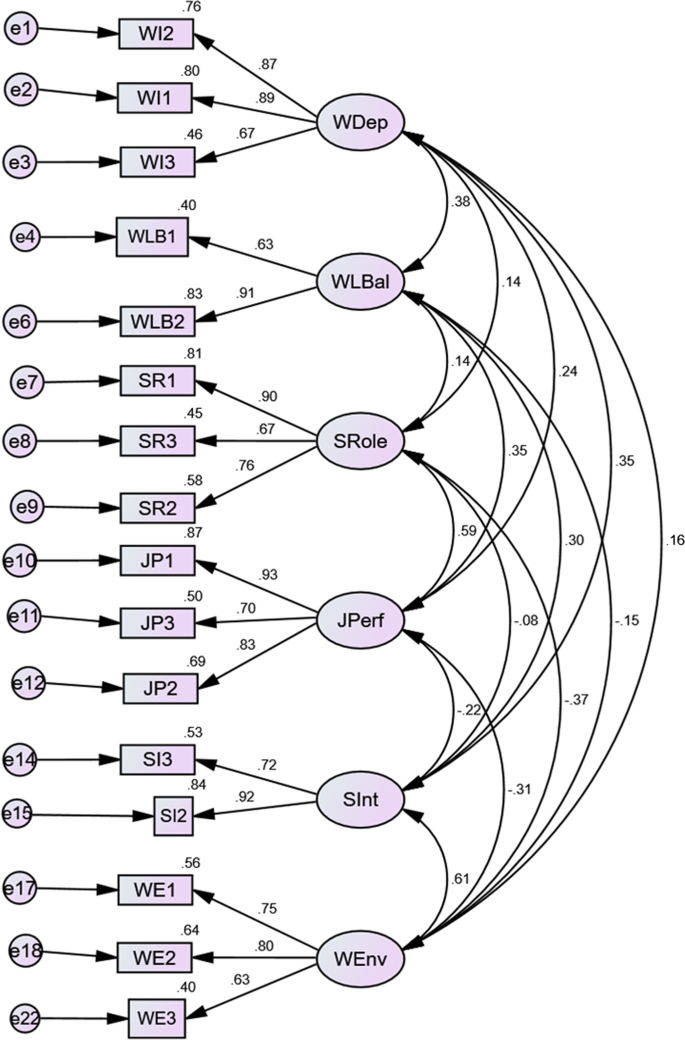

Another key question for Trip.com was the effect of hybrid WFH on employee performance. To assess that, we examined four measures of performance: six-monthly performance reviews and promotion outcomes for up to two years after the start of the experiment, detailed performance evaluations, and the lines of code written by the computer engineers. We also collected self-assessed productivity effects of hybrid working from experimental participants before and after the experiment to evaluate employee perceptions.

Performance reviews are important within Trip.com as they determine employees’ pay and career progression, so are carefully conducted. The review process for each employee is built on formal assessments provided by their managers, co-workers, direct reports and, if appropriate, customers. They are reviewed by employees, collated by managers and by the human resources team, and then discussed between the manager and the employee. This lengthy process takes several weeks, providing a well-grounded measure of employee performance. Although these reviews are not perfect, given their tight link to pay and career development, both managers and employees put a large amount of effort into making these informative measures of performance.

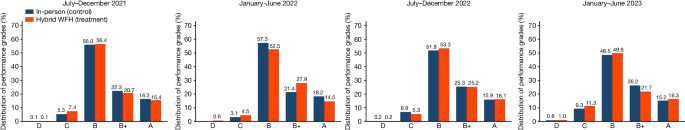

Figure 3 reports the distribution of performance grades for treatment and control employees for the four half-year periods: July to December 2021, January to June 2022, July to December 2022 and January to June 2023. These four performance reviews span a two-year period from the start of the experimental period. Across all review periods, we found no difference in reviews between the treatment and control groups (Extended Data Table 4 and ‘Null results’ section of the Methods ).

Results from performance reviews of 1,507 employees in July–December 2021, 1,355 employees in January–June 2022, 1,301 employees in July–December 2022 and 1,254 employees in January–June 2023. Samples are lower over time owing to employee attrition from the original experimental sample. Two-tailed t -tests for the performance difference within each period between the control and treatment groups, after assigning each letter grade a numeric value from 1 (D) to 5 (A), are (difference = 0.056, s.e. = 0.043, CI = [−0.029, 0.14], P = 0.198) for July–December 2021; (difference = 0.034, s.e. = 0.044, CI = [−0.0529, 0.122], P = 0.440) for January–June 2022; (difference = −0.019, s.e. = 0.046, CI = [−0.11, 0.072], P = 0.677) for July to December 2022; and (difference = 0.046, s.e. = 0.051, CI = [−0.054, 0.146], P = 0.369) for January–June 2023. The null equivalence tests are included in the ‘Null results’ section of the Methods .

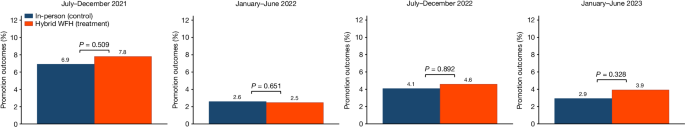

Figure 4 reports the distribution of promotion outcomes for the treatment and control employees for the same periods. We see no evidence of a difference in promotion rates across treatment and control employees. This is an important result given the evidence that fully remote working can damage employee development and promotions 14 , 17 , 18 .

Promotion outcomes for 1,522 employees in July–December 2021, 1,378 employees in January–June 2022, 1,314 employees in July–December 2022 and 1,283 employees in January–June 2023. Samples are lower over time owing to employee attrition from the original experimental sample. Two-tailed t -tests for the promotion difference within each period between the control and treatment groups are (difference = −0.86, s.e. = 1.34, CI = [−3.51, 1.74], P = 0.509) for July–December 2021 promotions; (difference = 0.12, s.e. = 0.85, CI = [−1.54, 1.78], P = 0.892) for January–June 2022 promotions; (difference = −0.51, s.e. = 1.12, CI = [−2.72, 1.70], P = 0.651) for July–December 2022 promotions; and (difference = −0.99, s.e. = 1.02, CI = [−2.99, 1.00], P = 0.328) for January–June 2023 promotions. The null equivalence tests are included in the ‘Null results’ section of the Methods .

We also analysed the effects of treatment on performance grades and promotions for a variety of subgroups, including managers, employees with a manager in the treatment group, longer-tenured employees, longer-commuting employees, women, employees with children, computer engineers and those living further away, as well as looking at whether internet speed had any effect. We found no evidence of a difference in response to treatment across these groups (Extended Data Table 5 ).

The experiment also analysed two other measures of employee performance. First, the performance reviews at Trip.com have subcomponents for individual activities such as ‘innovation’, ‘leadership’, ‘development’ and ‘execution’ (nine categories in all) when these are important for an individual employee’s role. We collected these data and analysed these scores for the four six-month performance review periods. We found no evidence of a difference across these nine major categories over the four performance review periods (Extended Data Table 6 ). This indicates that for categories that involve softer skills or more team-focused activities—such as development and innovation—there is no evidence for a material effect of being randomized into the hybrid WFH treatment. Second, for the 653 computer engineers, we obtained data on the lines of code uploaded by each engineer each day. For this ‘lines of code submitted’ measure, we found no difference between employees in the control and treatment groups (Extended Data Fig. 1 and ‘Null results’ section of the Methods ).

Self-assessed productivity

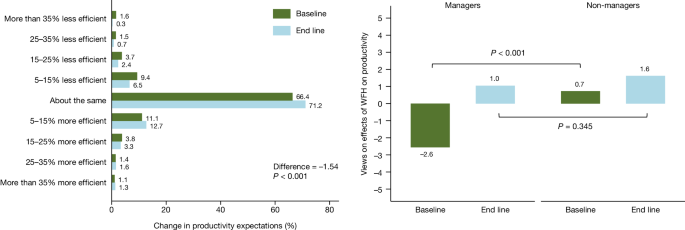

All experiment participants were polled before the experiment in a baseline survey on 29 and 30 July 2021, which included a two-part question on their beliefs about the effects of hybrid WFH on productivity. Employees were asked ‘What is your expectation for the impact of hybrid WFH on your productivity?’, with three options of ‘positive’, ‘about the same’ or ‘negative’. Individuals who chose the answer ‘positive’ were then offered a set of options asking how positive they felt, ranging from [5% to 15%] up to [35% or more], and similarly so for negative choices. For aggregate impacts we took the mid-points of each bin, and 42.5% for >35% and –42.5% for <−35%. Employees were resurveyed with the same question after the end of the experiment on 21 January 2022.

The left panel of Fig. 5 shows that employees’ pre-experimental beliefs about WFH and productivity were extremely varied. The baseline mean was –0.1%, but with widespread variation (standard deviation of 11%). This spread should be unsurprising to anyone who has been following the active debate about the effects of remote work on productivity. At the end-line survey conducted on 21 January 2022, the mean of these beliefs had significantly increased to 1.5%, revealing that the experience of hybrid working led to a small improvement in average employee beliefs about the productivity impact of hybrid working (mean baseline = −0.06%, mean endline = 1.48%, t (2658) = −3.84, P < 0.001). This could be because hybrid WFH saves employees commuting time and is less physically tiring, and, with intermittent breaks between group time and quiet individual time, can improve performance 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 .

Sample from 1,315 employees (314 managers, 1,001 non-managers) at the baseline and 1,345 employees (324 managers, 1,021 non-managers) at the end line. Two-tailed t -tests for the difference in productivity expectations between baseline and end line, after assigning a numeric value corresponding to the midpoint of the bucket, are (baseline mean = −0.058, end-line mean = 1.48, difference = −1.54, s.e. = 0.40, CI = [−2.33, −0.753], P < 0.001). Two-tailed t -tests for the baseline difference between the productivity expectations of managers and non-managers are (difference = −3.28, s.e. = 0.72, CI = [−4.69, −1.86], P < 0.001), and the t -tests for the end-line difference are (difference = −0.571, s.e. = 0.604, CI = [−1.76, 0.615], P = 0.345).

The right panel of Fig. 5 shows that in the baseline survey, managers were negative about the perceived effect of hybrid work on their productivity, with a mean effect of −2.6%. Non-managers, by contrast, were significantly more positive, at +0.7% in the baseline survey (mean non-manager = 0.7%, mean manager = −2.6%, t (1313) = −4.56, P < 0.001). At the end of the experiment, the views of managers improved to 1.0%, with no evidence of a difference from the non-managers’ mean value of 1.6% (mean non-manager = 1.62%, mean manager = 1.05%, t (1343) = −0.95, P = 0.345). Hence, the experiment led managers to positively update their views about how hybrid WFH affects productivity, and to more closely align with non-managers.

Of note, we saw that employees in the treatment and control groups had similar increases in self-assessed productivity (difference 0.58%, s.d. = 0.59%). Employees from four other divisions in Trip.com were also polled about the productivity impact of hybrid WFH after the end of the experiment in March 2022, with a mean estimate of +2.8% on a sample of 3,461 responses—similar to the 1.5% end line for the experimental sample. This suggests that even close exposure to hybrid WFH is sufficient for employees to change their views, consistent with previous evidence of a positive society-wide shift in perceptions about WFH productivity after the 2020 pandemic 8 .

Once the experiment ended, the Trip.com executive committee examined the data and voted to extend the hybrid WFH policy to all employees in all divisions of the company with immediate effect. Their logic was that each quit cost the company approximately US$20,000 in recruitment and training, so a one-third reduction in attrition for the firm would generate millions of dollars in savings. This was publicly announced on 14 February 2022, with wide coverage in the Chinese media. Since then, other Chinese tech firms have adopted similar hybrid policies 23 .

This highlights how, contrary to the previous causal research focused on fully remote work, which found mostly negative effects on productivity 5 , 6 , 7 , hybrid remote work can leave performance unchanged. This suggests that hybrid working can be profitably adopted by organizations, given its effect on reducing attrition, which is estimated to cost about 50% of an individual’s annual salary for graduate employees 24 . Hybrid working also offers large gains for society by providing a valuable amenity (perk) to employees, reducing commuting and easing child-care 6 , 25 , 26 .

The experiment was conducted in a Chinese technology firm based in Shanghai. Although it might not be possible to replicate these results perfectly in other situations, Trip.com is a large multinational firm with global suppliers, customers and investors. Its offices are modern buildings that look similar to those in many American, Asian and European cities. Trip employees worked 8.6 h per day on average, close to the 8 h per day that is usual for US graduate employees 27 . The business had a large drop in revenue in 2020 (see Extended Data Fig. 4 ), followed by roughly flat revenues through the 2021 experiment period into 2022, so this was not a period of exceptionally fast or slow growth. As such, we believe that these results— that is, the finding that allowing employees to WFH two days per week reduces quit rates and has a limited effect on performance—would probably extend to other organizations. Also, this experiment analysed the effects of working three days per week in the office and two days per week from home. So, our findings might not replicate to all other hybrid work arrangements, but we believe that they could extend to other hybrid settings with a similar number of days in the office, such as two or four days a week. We are not sure whether the results would extend to more remote settings such as one day a week (or less) in the office, owing to potential challenges around training, innovating and culture in fully remote settings.

Finally, we should point out two implications of the experimental design. First, full enrolment into hybrid schemes is important because of concerns that volunteering might be seen as a negative signal about career ambitions. The low volunteer rate among female employees, despite their high implied value (from the large reductions in quit rates observed), is particularly notable in this regard. Second, there is value in experimentation. Before the experiment, managers were net-negative in their views on the productivity impact of hybrid working, but after the experiment, their views became net-positive. This highlights the benefits of experimentation for firms to evaluate new working practices and technologies.

Location and set-up

Our experiment took place at Trip.com in Shanghai, China. In July 2021, Trip.com decided to evaluate hybrid WFH after seeing its popularity amongst US tech firms. The first step took place on 27 July 2021, when the firm surveyed 1,612 eligible engineers, marketing and finance employees in the Airfare and IT divisions about the option of hybrid WFH. They excluded interns and rookies who were in probation periods because on-site learning and mentoring are particularly important for those individuals. Trip.com chose these two divisions as representative of the firm, with a mix of employee types to assess any potentially heterogeneous impacts. About half of the employees in these divisions are technical employees, writing software code for the website, and front-end or back-end operating systems. The remainder work in business development, with tasks such as talking to airlines, travel agents or vendors to develop new services and products; in market planning and executing advertising and marketing campaigns; and in business services, dealing with a range of financial, regulatory and strategy issues. Across these groups, 395 individuals were managers and 1,217 non-managers, providing a large enough sample of both groups to evaluate their response to hybrid WFH.

Randomization

The employees were sent an email outlining how the six-month experiment offered them the option (but not the obligation) to WFH on Wednesday and Friday. After the initial email and two follow-up reminders, a group of 518 employees volunteered. The firm randomized employees with odd birthdays—those born on the first, third, fifth and so on of the month—into eligibility for the hybrid WFH scheme starting on the week of 9 August. Those with even birthdays—born on the second, fourth, sixth and so on of the month—were not eligible, so formed the control group.

The top management at the firm was surprised at the low volunteer rate for the optional hybrid WFH scheme. They suspected that many employees were hesitating because of concerns that volunteering would be seen as a negative signal of ambition and productivity. This is not unreasonable. For example, a previous study 28 found in the US firm they evaluated that WFH employees were negatively selected on productivity. So, on 6 September, all of the remaining 1,094 non-volunteer employees were told that they were also included in the program. The odd-birthday employees were again randomized into the hybrid WFH treatment and began the experiment on the week of 13 September. In this paper we analyse the two groups together, but examining the volunteer and non-volunteer groups individually yields similar findings of reduced quit rates and no impact on performance.

Employee characteristics and balancing tests

Figure 1 shows some pictures of employees working in the office (left side). Employees all worked in modern open-plan offices in desk groupings of four or six colleagues from the same team. By contrast, when WFH, they usually worked alone in their apartments, typically in the living room or kitchen (see Extended Data Fig. 2 ).

The individuals in the experimental sample are typically in their mid-30s. About two-thirds are male, all of them have a university undergraduate degree and almost one-third have a graduate degree (typically a master’s degree). In addition, nearly half of the employees have children (details in Extended Data Table 1 ).

In Extended Data Table 7 we confirm that this sample is also balanced across the treatment and control groups, by conducting a two-sample t -test. The exceptions are from random variation given that the sampling was by even or odd day-of-month birthday—the control sample is 0.5 years older ( P = 0.06), and this is presumably linked to why those in this group have 0.06% more children ( P = 0.02) and 0.4 years more tenure ( P = 0.09).

In Extended Data Table 3 , we examine the decision to volunteer for the WFH experiment. We see that volunteers were significantly less likely to be managers (mean non-volunteer = 0.28, mean volunteer = 0.17, t (1610) = −4.85, P < 0.001) and had longer commute times (hours) (mean non-volunteer = 0.80, mean volunteer = 0.89, t (1257) = 3.68, P < 0.001). Notably, we don’t find evidence of a relationship between volunteering and previous performance scores (mean non-volunteer = 3.81, mean volunteer = 3.81, t (1580) = −0.02, P = 0.985), highlighting, at least in this case, the lack of evidence for any negative (or positive) selection effects around WFH.

Extended Data Fig. 3 plots the take-up rates of WFH on Wednesday and Friday by volunteer and non-volunteer groups. We see a few notable facts. First, take-up overall was about 55% for volunteers and 40% for non-volunteers, indicating that both groups tended to WFH only one day, typically Friday, each week. At Trip.com, large meetings and product launches often happen mid-week, so Fridays are seen as a better day to WFH. Second, the take-up rate even for non-volunteers was 40%, indicating that Trip.com’s suspicion that many employees did not volunteer out of fear of negative signalling was well-founded, and highlighting that amenities like WFH, holiday, maternity or paternity leave might need to be mandatory to ensure reasonable take-up rates. Third, take-up surged on Fridays before major holidays. Many employees returned to their home towns, using their WFH day to travel home on the quieter Thursday evening or Friday morning. Finally, take-up rates jumped for both treatment-group and control-group employees in late January 2022 after a case of COVID in the Shanghai headquarters. Trip.com allowed all employees at that point to WFH, so the experiment effectively ended early on Friday 21 January. The measure of an employee’s daily WFH take-up excludes leave, sick leave or occasions when they cannot come to the office owing to extreme bad weather (typhoon) or to the COVID outbreak in the company.

Null results

To interpret the main null results, we conduct null equivalence tests using the two one-sided tests (TOST) procedure in R (refs. 29 , 30 ). This test required us to specify the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI). For the results pertaining to performance review measures, we use 0.5 as the SESOI. This corresponds to half of a consecutive letter grade increase or decrease, because we had assigned numeric values to performance letter grades in increments of 1, with the lowest letter grade D being 1, and the highest letter grade A being 5. We performed equivalence tests for a two-sample Welch’s t -test using equivalence bounds of ±0.5. The TOST procedure yielded significant results using the default alpha of 0.05 for the tests against both the upper and the lower equivalence bounds for the performance measures for July–December 2021 ( t (1504) = −10.20, P < 0.001)), January–June 2022 ( t (1353) = −10.57, P < 0.001)), July–December 2022 ( t (1299) = 10.34, P < 0.001)) and January–June 2023 ( t (1248) = −8.80, P < 0.001)). The equivalence test is therefore significant, which means we can reject the hypothesis that the true effect of the treatment on performance is larger than 0.5 or smaller than −0.5. So, we interpret the performance effects of the treatment to be actually null on the basis of the SESOI we used, as opposed to no evidence of a difference in performance.

We conducted null equivalence results for the effect of the treatment on promotions using 2 as the SESOI, corresponding to ±2 percentage points (pp) difference in promotion rates. Although we can reject the null hypothesis that the true effect of treatment on promotion is larger than 2 pp or smaller than −2 pp in January–June 2022 ( t (1376) = −2.22, P = 0.013) and July–December 2022 ( t (1306) = 1.33, P = 0.092), we fail to reject the null equivalence hypothesis in July–December 2021 ( t (1513) = 0.83, P = 0.203) and January–June 2023 ( t (1250) = 0.98, P = 0.163). Thus, we interpret the results on promotion as no evidence of a difference between promotion rates across treatment and control employees.

We also conducted the equivalence test for lines of code using 29 lines of code per day as the SESOI, which corresponds to 10% of the mean number of lines of code for the control group. We arrive at this SESOI on the basis of rounding down the productivity effects of previous findings 8 , 10 . We can reject the equivalence null hypothesis for lines of code ( t (92362) = −2.74, P = 0.003)) so we interpret the effect of the treatment as a null effect.

Volunteer versus non-volunteer groups

In the main paper we pool the volunteer and non-volunteer groups. In Extended Data Table 5 we examine the impacts on performance and promotions and we see no evidence of a difference in performance and promotion treatment effects for volunteer versus non-volunteer groups (column 9).

Performance subcategories

The company has a rigorous performance-reviewing process every six months that determines employees’ pay and promotion, so is carefully conducted. The review process for each employee is built on formal reviews provided by their managers, project leaders and sometimes co-workers (peer review). Managers are more like an employee’s direct managers for organizational purposes, but for a particular project, the project leader could be another higher-level employee. In such a case, the manager of the employee would ask that project leader for an opinion on the employee’s contribution to the project. An individual’s overall score is a weighted sum of scores from various subcategories that managers have broad flexibility over defining, because tasks differ across employees, and managers would give a score for each task. For example, an employee running a team themselves will have subcategories around developing their direct reports (leadership and communication), whereas an employee running a server network will have subcategories around efficiency and execution. The performance subcategory data come from the text of the performance review. We first used the most popular Chinese word segmentation package in Python, named Jieba, to identify the most frequent Chinese words from task titles across four performance reviews. We also removed meaningless words and incorporated common expressions such as key performance indicators (‘KPI’), objectives and key results (‘OKR’), ‘rate’ and ‘%’. This process resulted in a total of 236 unique words and expressions. We then manually categorized those most frequent keywords into nine major subcategories (see below) by meanings and relevance. Finally, on the basis of the presence of keywords in the task title, tasks were grouped into the following subcategories:

Communication tasks are those that involve communication, collaboration, cooperation, coordination, participation, suggestion, assistance, organization, sharing and relationships.

Development tasks are those that involve coding or codes, data or datasets, systems, techniques and skills.

Efficiency tasks are those that involve cost reduction, ratios, return on investment (ROI), rate, %, improvement, growth, lifting, adding, optimizing, profit, receiving, gross merchandise value (GMV), OKR, KPI, work and goal.

Execution tasks are those that involve execution, conducting, maintenance, delivery, output, quality, contribution and workload.

Innovation tasks are those that involve development, R&D and innovation.

Leadership tasks are those that involve leadership, managing or management, approval, internal, strategy, coordination and planning.

Learning tasks are those that involve learning, growing, maturing, talent, ability, value competitiveness and personal improvement.

Project tasks are those that involve project, supply, product, business line, cooperation and clients.

Risk tasks are those that involve risk, compliance, supervision, recording and monitoring, safety, rules and privacy.

Data sources

Data were provided by a combination of Trip.com sources, including human resources records, performance reviews and two surveys. All data were anonymized and coded using a scrambled individual ID code, so no personally identifiable information was shared with the Stanford team. The data were drawn directly from the Trip.com administrative data systems on a monthly basis. Gender is collected by Trip.com from employees when they join the company.

The full sample has 1,612 experiment participants, but we have 1,507, 1,355, 1,301 and 1,254 employees, respectively, in the subsamples for the four performance reviews from July–December 2021, January–June 2022, July–December 2022 and January–June 2023. These smaller samples are due to attrition. In addition, for the first performance review in July–December 2021, 105 employees did not have sufficient pre-experiment tenure to support a performance review (they had joined the firm less than three months before the experimental draw). The review text data covers 1,507,1,339,1,290 and 1,246 people, as some employees do have an overall score and review text but do not have additional and task-specific scores. The reason is that these employees do not have the full range of all tasks, so their managers did not write the full review script. For the two surveys, Trip.com used Starbucks vouchers to incentivize response and collected responses from 1,315 employees (314 managers, 1,001 non-managers) at the baseline on the left, and that of 1,345 employees (324 managers, 1,021 non-managers) at the end line.

All tests used two-sided Student t -tests unless otherwise stated. Analysis was run on Stata v17 and v18, R version 4.2.2. Unless stated otherwise, no additional covariates are included in the tests. The null hypothesis for all of the tests excluding null equivalence tests is a coefficient of zero (for example, zero difference between treatment and control).

Inclusion and ethics statement

The design and execution of the experiment was run by Trip.com. No participants were forced to WFH owing to the experiment (the entire firm was, however, forced to WFH during the pandemic lockdown). The treatment sample had the option but not the obligation to WFH on Wednesday or Friday. The experiment was designed, initiated and run by Trip.com. N.B. and R.H. were invited to analyse the data from the experiment, with consent for data collection coming from Trip.com internally. The experiment was exempt under institutional review board (IRB) approval guidelines because it was designed and initiated by Trip.com, before N.B. and R.H. were invited to analyse the data. Only anonymous data were shared with the Stanford team. Trip.com based the experimental design and execution on their previous experience with WFH randomized control trials 17 .

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data necessary to reproduce the primary results of this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6X4ZZL . These data have been anonymized and split into individual files to ensure that no individual is identifiable. All figures and tables can be replicated using this data.

Code availability

The code necessary to reproduce the primary results of this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6X4ZZL .

Working From Home Research: Survey of Workplace Attitudes and Arrangements; https://wfhresearch.com/ (2023).

Aksoy, C. G. et al. Working from Home Around the Globe: 2023 Report. EconPol Policy Brief No. 53 (EconPol, 2023).

McGlauflin, P. JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon chides managers who work from home: ‘I don’t know how you can be a leader and not be completely accessible to your people’. Fortune (11 July 2023).

Kelly, J. Goldman Sachs tells employees to return to the office by July 14, as Wall Street pushes back on the work-from-home trend. Forbes (5 May 2021).

Goswami, R. Elon Musk: Working from home is ‘morally wrong’ when service workers still have to show up. CNBC (16 May 2023).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. Why Working from Home Will Stick . National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 28731 (NBER, 2021).

The Economist. The working from home illusion fades. Economist (28 Jun 2023).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. The Evolution of Working from Home . Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) Working Paper No. 23-19 (SIEPR, 2023).

Flex Index. The Flex Report Q1 2023 (Scoop Technologies, 2023).

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F. & Uzzi, B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science 316 , 1036–1039 (2007).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pabilonia, S. W. & Vernon, V. Telework, wages, and time use in the United States. Rev. Econ. Household 20 , 687–734 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Brucks, M. S. & Levav, J. Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation. Nature 605 , 108–112 (2022).

Aksoy, C. G. et al. Working from home around the world. EconPol Forum 23 , 38–41 (2022).

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Emanuel, N., Harrington, E. & Pallais, A. The Power of Proximity to Coworkers: Training for Tomorrow or Productivity Today? National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 31880 (NBER, 2023).

Goldin, C. Understanding the Economic Impact Of COVID-19 on Women . National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 29974 (NBER, 2022).

Angelici, M. & Profeta, P. Smart-Working: Work Flexibility Without Constraints . CESifo Working Paper No. 8165 (CESifo, 2020).

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J. & Ying, Z. J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 130 , 165–218 (2015).

Yang, L. et al. The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 43–54 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Girotra, K., Terwiesch, C. & Ulrich, K. T. Idea generation and the quality of the best idea. Manag. Sci. 56 , 591–605 (2010).

Stroebe, W. & Diehl, M. Why groups are less effective than their members: on productivity losses in idea-generating groups. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 5 , 271–303 (2011).

Bernstein, E., Shore, J. & Lazear, D. How intermittent breaks in interaction improve collective intelligence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 8734–8739 (2018).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Choudhury, P., Khanna, T., Makridis, C. A. & Schirmann, K. Is Hybrid Work the Best of Both Worlds? Evidence from a Field Experiment . Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 22-063 (Harvard Business School, 2022).

Dreamteam Payroll. Alibaba’s new welfare plus extra days off work without reducing salary; https://www.dreamteampayrolloutsource.co.th/en/alibaba-welfare-benefit/ (2022).

Allen, D. G. Retaining Talent: A Guide to Analyzing and Managing Employee Turnover (Society for Human Resources Management, 2008).

Mas, A. & Pallais, A. Valuing alternative work arrangements. Am. Econ. Rev. 107 , 3722–3759 (2017).

Wood, S. et al. Satisfaction with one’s job and working at home in the COVID-19 pandemic: a two-wave study. Appl. Psychol. 72 , 1409–1429 (2023).

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey; https://www.bls.gov/charts/american-time-use/emp-by-ftpt-job-edu-h.htm .

Emanuel, N. & Harrington, E. Working remotely? Selection, treatment, and the market for remote work. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. (in the press).

Points of significance. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7 , 293–294 (2023).

Lakens, D., Scheel, A. M. & Isager, P. M. Equivalence testing for psychological research: a tutorial. Adv. Meth. Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1 , 259–269 (2018).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Smith Richardson Foundation for funding; J. Cao, T. Zhang, S. Ye, F. Chen, X. Zhang, Y. He, J. Li, B. Ye and M. Akan for data, advice and logistical support; D. Yilin for research assistance; S. Ayan, S. Buckman, S. Gurung, M. Jackson and P. Lambert for draft feedback; and J. Sun for project leadership.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Nicholas Bloom, Ruobing Han

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Economics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Nicholas Bloom

Shenzhen Finance lnstitute, School of Management and Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China

Ruobing Han

National School of Development, Peking University, Beijing, China

James Liang

Trip.com, Shanghai, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

N.B. oversaw the analysis, presented the results and wrote the main drafts of the paper. He was the principal investigator on the research grant supporting the research. R.H. supervised data collection and analysed the data, presented the results and helped to draft the paper. J.L. initiated and designed the study, discussed the results and analysis and facilitated the Trip.com engagement. N.B. and R.H. are co-first authors.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Nicholas Bloom , Ruobing Han or James Liang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

No funding was received from Trip.com. J.L. is the co-founder, former CEO and current chairman of Trip.com, with equity holdings in Trip.com. No other co-author has any financial relationship with Trip.com. Neither the results nor the paper was pre-screened by anyone. The experiment was registered with the American Economic Association on 16 August 2021 after the experiment had begun but before N.B. and R.H. had received any data. Only anonymous data were shared with the Stanford team.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature thanks Sooyeol Kim and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended data fig. 1 wfh had no effect on lines of code written..

The data coves the experimental period starting on 9 August 2021 for the first wave and 13 September for the second wave, running to 23 January 2022, for both waves. Lines of code submitted per day is available for 653 employees whose primary role was writing code, spanning a total of 95,494 days. Lines are those uploaded to trip.com on a daily basis. Data plotted on a log-2 scale for readability. Reported P value is calculated using a two-sided t -test on the number of code lines and the difference is for control minus treatment. When using log 2 (code lines) the difference has a P value of 0.750 (noting the sample is 27,605 days because of dropping 0 values). When using log 2 (1 + code lines) the difference has a P value of 0.0103, with treatment having the higher average values. The null equivalence tests are included in the ‘Null results’ section of the Methods .

Extended Data Fig. 2 Home (October 2021).

Employees set up basic working environments in their living rooms, studies, or kitchens, and bring back company laptops if necessary.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Take-up rate for WFH treatment and control by volunteer status.

Data for 1,612 employees from 9 August 2021 (volunteers) and 13 September (non-volunteers) to 23 January 2022. Public holidays, personal holidays and excused absence (for example, sick leave) are excluded. Take-up rate is percentage of Wednesday and Friday each week they WFH.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Trip.com revenues.

Trip.com revenues from 2000 to 2023.

Supplementary information

Reporting summary, peer review file, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bloom, N., Han, R. & Liang, J. Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance. Nature 630 , 920–925 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07500-2

Download citation

Received : 15 August 2023

Accepted : 30 April 2024

Published : 12 June 2024

Issue Date : 27 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07500-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 November 2020

A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health?

- Jodi Oakman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0484-8442 1 ,

- Natasha Kinsman 1 ,

- Rwth Stuckey 1 ,

- Melissa Graham 1 &

- Victoria Weale 1

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 1825 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

211k Accesses

170 Altmetric

Metrics details

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in changes to the working arrangements of millions of employees who are now based at home and may continue to work at home, in some capacity, for the foreseeable future. Decisions on how to promote employees’ health whilst working at home (WAH) need to be based on the best available evidence to optimise worker outcomes. The aim of this rapid review was to review the impact of WAH on individual workers’ mental and physical health, and determine any gender difference, to develop recommendations for employers and employees to optimise workers’ health.

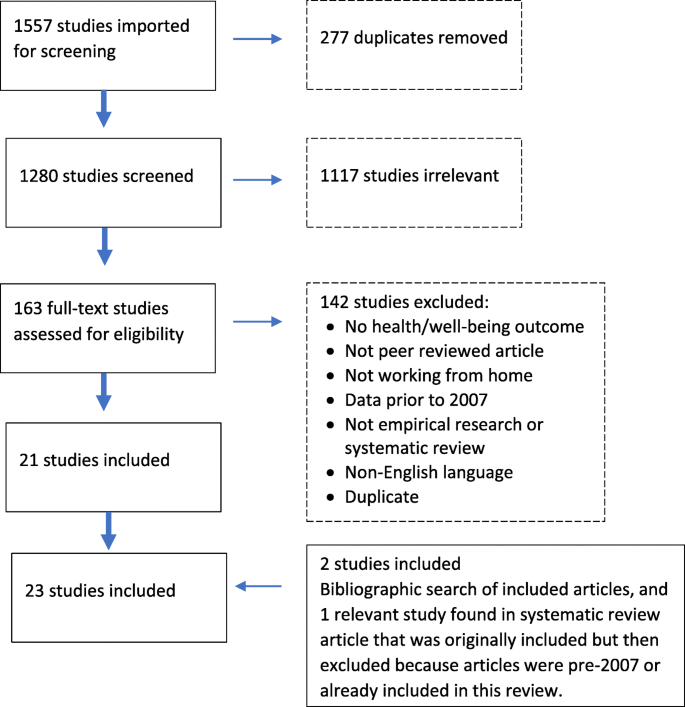

A search was undertaken in three databases, PsychInfo, ProQuest, and Web of Science, from 2007 to May 2020. Selection criteria included studies which involved employees who regularly worked at home, and specifically reported on physical or mental health-related outcomes. Two review authors independently screened studies for inclusion, one author extracted data and conducted risk of bias assessments with review by a second author.

Twenty-three papers meet the selection criteria for this review. Ten health outcomes were reported: pain, self-reported health, safety, well-being, stress, depression, fatigue, quality of life, strain and happiness. The impact on health outcomes was strongly influenced by the degree of organisational support available to employees, colleague support, social connectedness (outside of work), and levels of work to family conflict. Overall, women were less likely to experience improved health outcomes when WAH.

Conclusions

This review identified several health outcomes affected by WAH. The health/work relationship is complex and requires consideration of broader system factors to optimise the effects of WAH on workers’ health. It is likely mandated WAH will continue to some degree for the foreseeable future; organisations will need to implement formalised WAH policies that consider work-home boundary management support, role clarity, workload, performance indicators, technical support, facilitation of co-worker networking, and training for managers.

Peer Review reports

The current global pandemic caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in an unprecedented situation with wide ranging health and economic impacts [ 1 , 2 ]. The working environment has been significantly changed with thousands of jobs lost and women impacted at higher rates than men [ 3 , 4 ]. For those employed in sectors able to work remotely, mostly white-collar professional workers, their homes have now become their workplace, school, and place for relaxation. As economies begin to reopen with resumption of some normal activities, questions arise about the potential return to formal office environments and the implications for employees whilst COVID-19 remains active in the community [ 5 ]. Many organisations will continue mandating working at home (WAH) for the foreseeable future to avoid making COVID-19 regulation related changes to their office environments [ 6 ].

The emergence of new technologies has revolutionised working patterns, enabling work from anywhere for many employees [ 7 , 8 ]. The concept of telework has existed since the 1970s but in a more limited scope than is currently possible [ 7 ]. The extensive availability of technology has enabled location and timing of work to be undertaken with significant flexibility, offering benefits to employers and employees. However, to date there is no universally accepted definition of telework. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines telework as the use of information and communications technologies (ICTs) including smartphones, tablets, laptops or desktop computers for work that is performed outside the employer’s premises [ 7 ]. A range of positive benefits are associated with teleworking, including improved family and work integration, reductions in fatigue and improved productivity [ 9 ]. However, the blurring of physical and organisational boundaries between work and home can also negatively impact an individual’s mental and physical health due to extended hours, lack of or unclear delineation between work and home, and limited support from organisations [ 10 ]. The mandatory WAH situation is complex and requires a systematic examination to identify the impact of organisational, physical, environmental and psychosocial factors on individuals’ mental and physical health.

The ongoing need for containment of COVID 19 and continued need to undertake WAH requires evidence synthesis to develop policies and guidelines to protect employees’ health and well-being. We undertook a rapid review of the evidence on the impact of WAH on individual workers’ mental and physical health. In addition, we examined any gender differences of these impacts. We considered the body of evidence to develop recommendations for employers to optimise the health of their employees.

Search strategy and selection criteria

This rapid review was undertaken using principles recommended by the WHO [ 11 ]. PRISMA reporting guidelines were followed [ 12 ]. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a senior librarian and, for this rapid review, was limited to three databases. ProQuest (Central, Coronavirus Research Database, Social Science Premium Collection, Science Database), PsycINFO and Web of Science databases were searched on 5 May 2020. The search strategy was limited to English language, peer reviewed journal articles published from January 2007 onwards. To ensure wide capture of the literature, study design was not restricted. The date limit was selected to ensure the contemporary work environment was captured. The year 2007 was when the first smartphone was released, this technology change enabled greater flexibility in relation to work arrangements. To ensure the search strategy addressed the research questions two broad concepts were included, those relating to WAH (e.g., “home work”, “telecommute”) and health-related outcomes (e.g., “musculoskeletal risk”, “mental health”). Refer to Appendix for the full search strategy.

For inclusion in the current rapid review, studies were required to focus on adult white collar/professional employees WAH during business hours, and to include mental or physical health related outcomes of workers. Studies were excluded if they focused on domestic workers, self-employed workers, informal working from home (working from home after hours to catch up on work), productivity outcomes, chronic illness/disability, or pregnancy/breast feeding. The rationale of the search strategy was to capture studies which included participants who undertook working from home on a regular basis, but these arrangements did not necessarily have to be mandated or formalised by the organisation.

Titles, abstracts and full texts were screened by two authors using Covidence [ 13 ]. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Reasons for exclusion of studies were noted. The outcomes of interest were measurable changes in physical or mental health. Secondary analysis was undertaken for studies which reported differences by gender.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was undertaken using a standardised form and included setting, study design, method used, details of participants, industry setting, measures used, and the health outcomes. The risk of bias assessment was used as a proxy for the quality of the study and undertaken for both qualitative and quantitative studies using separate forms. The risk of bias domains were derived from the RTI research bank, Cochrane Collaboration tool quality assessment, and the Johanna Briggs appraisal tool for qualitative research [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Each potential source of bias was assessed as high, moderate, low, or unclear risk with justification given for judgement. In line with rapid review principles, data extraction and risk of bias for each article was undertaken by at least one author, with a sub sample screened by a second author for accuracy.

An overall quality assessment of each study was determined using a previously published rating system [ 17 ]. Studies with a 'low' risk rating for the confounding factors criteria and a higher number of ‘low’ risks than ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risks, were deemed to have a 'low' overall risk of bias. Studies with a 'high' risk rating for the confounding factors criteria and more ‘low’ risks than ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risks, were assessed as having 'moderate' overall risk of bias. Studies with a 'high' risk of bias rating for confounding factors criteria, and more ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risks than ‘low’ risks were designated to have a 'high' overall risk of bias.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were organised using narrative synthesis to identify how WAH influenced employees physical and mental health. Studies were grouped by broad health outcomes and then a separate analysis by gender undertaken.

The database search identified 1557 papers of which 21 met the inclusion criteria. Two additional studies were included following a reference list search of the articles which met the inclusion criteria, making a total of 23 studies. The primary reason for exclusion was the study did not include a health outcome. The PRISMA diagram outlines the screening process (see Fig. 1 ). The studies represented 10 countries (USA, UK, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Belgium, South Africa, Brazil, Germany, The Netherlands), and varied in study design: 20 cross sectional, one cohort, one controlled before and after, and one combined cross sectional and cohort (refer Table 1 ). No randomised trials were identified. Studies included 19 quantitative, 3 qualitative and 1 mixed methods.

PRISMA diagram

Studies were conducted in the following industry sectors: government departments and agencies (five), financial services (three), technology (two), academia (one), telecommunications (one), logistics (one). Ten studies used data from surveys of the general public or did not focus on a particular industry sector. The number of hours and nature of WAH arrangements varied between studies; participants WAH either full time (two studies [ 21 , 36 ] or part-time, and had access to a formal WAH policy or ad hoc WAH approval by managers. Only one study examined employees undertaking mandatory WAH [ 36 ]. Some studies did not specify the nature of the WAH arrangements. Due to the heterogenous nature of the studies, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis.

Health related outcomes

Physical health related outcomes ( n = 3) identified in the studies included: pain, self-reported health and perceived safety. Mental health related outcomes ( n = 7) identified included: well-being, stress, depression, fatigue, quality of life, strain and happiness. Seven studies undertook separate gender analysis (see Table 2 ).

Risk of bias

Following assessment of risk of bias, quantitative studies were rated as: four high risk, three moderate risk, and 13 low risk. For the qualitative studies ( n = 3) the overall risk of bias for all studies was assessed as moderate. The four studies with high risk of bias included cross sectional surveys [ 18 , 22 , 26 , 31 ]. For the cohort studies, quantitative [ 29 ], qualitative [ 36 ] and mixed methods [ 39 ] were utilised, with moderate and low risk of bias, respectively (see Tables 3 and 4 ).

Physical health-related impacts

Three studies explored the physical health impacts of WAH [ 22 , 23 , 32 ]; one of these will be discussed in the section on gender. Filardí [ 22 ] surveyed government employees who reported that ‘I feel safer working from home’, but the WAH arrangements were not clearly defined. In contrast, a study by Nijp et al. [ 32 ] found WAH had a negative impact on physical health. This study measured self-reported health in a control and an intervention group of finance company employees, before and after implementation of a policy to enable part-time WAH. Participants reported a small but statistically significant decrease in self-reported health which could not be explained as usual health indicators and job demands remained unchanged.

Mental health-related impacts

The majority of studies (21 studies) explored the effect of working at home on mental health. Fourteen are explored in this section and seven studies that included a gender analysis are presented separately.

The impacts of WAH on mental health were complex. Nine studies considered environmental, organisational, physical, or psychosocial factors in the relationship between WAH and mental health [ 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 38 ]. Working at home could have negative or positive impacts, depending on various systemic moderators such as: the demands of the home environment, level of organisational support, and social connections external to work.

Five studies [ 20 , 25 , 33 , 35 , 38 ] examined the influence of colleagues and organisational support on WAH. Suh & Less [ 35 ] compared the effect of technostress (defined as work overload, invasion of privacy, and role ambiguity) on IT company employees doing low intensity WAH (< 2.5 days per week), to those doing high intensity WAH (> 2.5 days per week). Low intensity WAH employees experienced higher strain associated with work overload and invasion of privacy, related to IT complexity, pace of IT change, lower job autonomy, and being constantly in electronic contact with work. Bentley et al. [ 20 ] explored the influence of organisational (social and manager) support on health outcomes of WAH employees and found a similar relationship between lower levels of organisational support and higher psychological strain. Sardeshmukh et al. [ 33 ] also examined the effects of organisational support (via job resources and demands) and found associations between WAH and less time pressure, less role conflict, and greater autonomy, resulting in less exhaustion. However, they also found WAH was associated with lower social support, lower feedback and greater role ambiguity which increased exhaustion; overall these negative effects did not outweigh the overall positive impact of WAH. Vander Elst et al. [ 38 ] found increased WAH hours were associated with less emotional exhaustion and cognitive stress which was mediated by support from colleagues. Those working more days at home experienced greater emotional exhaustion and cognitive stress associated with reduced social support from their colleagues. Grant et al. [ 25 ] interviewed employees WAH and identified colleagues’ support and communication as important influences on psychological well-being. Tietze et al. [ 36 ] interviewed seven employees WAH on a full-time basis as part of a three-month pilot scheme. Employees reported an improved sense of personal well-being as they were no longer in a stressful office environment.

Anderson [ 18 ] measured the effect of WAH on the mental well-being of government employees (all participants were WAH > 1 day per fortnight), and found WAH had a positive effect on well-being (feeling at ease, grateful, enthusiastic, happy, and proud) with less negative effect on well-being (bored, frustrated, angry, anxious, and fatigued). The study also found individual traits of openness to experience, lower rumination, and greater social connectedness moderated the relationship between WAH and positive well-being, and a strong level of social connectedness (outside of work) was related to a less negative effect on well-being.

Two studies explored the home environment as a mediator for the relationship between WAH and health related outcomes. Work-family conflict (WFC) occurs when the demands of work impinge on domestic and family commitments. Golden’s [ 24 ] study of computer company employees who were WAH for greater periods of time than in the office, found high levels of exhaustion when combined with a high level of WFC. When WFC was low the same employees experienced a low level of exhaustion compared to those WAH only occasionally. Another study [ 31 ], which surveyed employees with dependent-care responsibilities, found an association between WAH and increased energy levels, and decreased stress; WAH acted as a mediator between health-related outcomes and dependent care responsibilities.

Relationships between WAH and the following mental health-related outcomes were examined: stress [ 8 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 38 ], quality of life [ 22 , 27 , 37 ], well-being [ 18 , 19 , 25 , 36 , 38 ], and depression [ 8 ]. Five studies [ 19 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 37 ], reported a decrease in stress levels of employees WAH on a part-time basis. One study [ 8 ] explored employees who were WAH either all or part of their work time and found no direct relationship between WAH and levels of stress. In contrast, VanderElst et al. [ 38 ] found WAH was associated with increased stress. Quality of life was enhanced through WAH in two surveys of employees [ 22 , 37 ]. Filardí et al. [ 22 ] included public sector employees but did not report how long employees were WAH. Tustin [ 37 ] included university employees who were WAH for some of the week.

Bosua et al. [ 19 ] studied employees from government, education and private sectors WAH for some of their week and found a greater sense of well-being was reported compared to when working in the office. Of note, participants reported their preference was to combine WAH with some office time so they could connect with colleagues.

Henke et al. [ 8 ] conducted a study within a financial company and compared employees WAH to those not WAH; those WAH less than 8 h per month had statistically lower levels of depression than those not WAH. No statistically significant relationships were identified between depression and greater number of hours WAH.

Four studies examined the direct relationship impact of WAH on fatigue (including exhaustion, tiredness or changes in energy levels) with mixed results [ 28 , 31 , 32 , 37 ]. Two studies [ 31 , 37 ] concluded WAH resulted in decreased levels of fatigue. However, others [ 28 , 32 ] concluded WAH had no effect on levels of fatigue.

The gender differences in health outcomes related to WAH

Seven studies examined outcomes by gender [ 21 , 23 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 34 , 39 ]. Three studies considered complex interactions when examining gender differences in the WAH and health related outcome relationship. Windelar et al. [ 39 ] examined the effect of interpersonal and external interactions on work exhaustion, using WAH as a moderator. They surveyed employees pre and post implementation of a formal WAH policy (study 1) and then compared employees WAH to those based in the office (study 2). Males had higher levels of work exhaustion following the commencement of telework (study 1). Both studies found WAH increased the negative effect of interactions external to the business on work exhaustion. Females WAH reported higher levels of work exhaustion compared to their colleagues who remained at the office (Study 2). Hornung et al. [ 27 ] examined the role of mediators on the relationship between WAH and mental health and gender differences; they surveyed public servants and found increased time WAH improved quality of life through increased autonomy (mediator). However, in a separate gender analysis the relationship was only significant for males. Eddleston & Mulki [ 21 ] reported an increase in job stress for employees WAH full-time. This was mediated by WFC; an inability to disengage from work, and the integration of work into home life, led to higher WFC which was associated with higher job stress. This relationship was moderated by gender with women experiencing greater WFC due to inability to disengage from work, and men experiencing greater WFC due to integration of work into the family domain.

The remaining four studies examined the direct relationship between WAH and health outcomes. Two studies, both using data from the American Time Use Survey, examined physical and mental health outcomes by gender. Gimenez-Nadal et al. [ 23 ] identified participants WAH as those who indicated non-commute days in a diary record. Diary records were followed by a well-being survey, where male teleworkers reported lower pain levels, lower stress, and lower tiredness (p < 0.05) compared to non-teleworkers; no differences were found between female teleworkers and non-teleworkers. Song & Gao [ 34 ] compared subjective pain when WAH to work at the office, by gender and parental status, and reported no differences. However, fathers who were WAH reported increased stress, and mothers WAH had decreased happiness.

Kim et al. [ 30 ] and Kazekami [ 29 ] examined the direct relationship between fatigue, stress and happiness. Kim et al. [ 30 ] reported males who were WAH regularly had lower levels of fatigue and stress compared to those who did not. For women, WAH was associated with lower stress levels but higher levels of fatigue compared to those not WAH. Kazekami [ 29 ] found that males WAH reported increased stress and happiness whilst no effect was found for females.

Due to the current COVID-19 situation, WAH has been implemented as part of a broad public health measure to prevent the spread of an infectious disease. Although this measure was introduced rapidly, it is likely WAH will remain in place for some time and organisations will utilise this as a strategy to manage the necessary physical distancing requirements to prevent further outbreaks of COVID-19. This rapid review explored the impact of WAH on physical and mental health outcomes to inform the development of guidelines to support employers in creating optimal working conditions. In addition, included studies were examined to explore any gender differences in the relationship between WAH and health.

The majority of studies in the rapid review employed cross-sectional designs and were of variable quality. The definition of WAH and the number of days per week employees were working at home were often unclear. Of the 23 studies identified as relevant to this review, only one investigated the condition of mandatory WAH [ 36 ], the remainder involved workers who were electing to WAH for different but regular time periods across a week. However, evidence from the review does suggest there are some reasonable actions employers can take to support their employees in optimising their working conditions whilst at home. This discussion will outline the physical and mental health outcomes of WAH and then, drawing on these findings, outline implications for practice.

Physical health and WAH was only examined in three studies. The very low number of studies identified could suggest the search strategy was not adequately targeted to capture studies assessing the physical health outcomes of WAH; however, a range of terms associated with musculoskeletal health were included. Grey literature may have offered further insights but was not included in this rapid review. An alternative explanation may be that in cases where employees are working at home for limited time periods, the use of standard guidelines for workstation arrangements have been considered sufficient and deployed to manage the physical health of workers. The limited coverage of physical health outcomes of WAH was not expected. Previous research, in relation to the occupational health of employees, suggests the focus is more typically on the physical aspects of health [ 40 ].

In contrast, the impact of WAH on mental health outcomes was covered by the majority of included studies ( n = 21). Three of the studies employed longitudinal approaches [ 29 , 36 , 39 ] with mixed results such as increased stress [ 29 ], improved well-being [ 36 ] and gendered impacts on exhaustion levels [ 39 ]. The mixed results and varying quality of the articles does create challenges in drawing out meaningful themes; however, differences in organisational responses and support were identified as important contributors to either increasing or mitigating negative health outcomes (e.g. [ 20 , 25 , 33 , 35 ]). The complexity of the WAH situation received only limited coverage [ 20 ]. An extensive literature exists supporting the important role of the work environment (e.g. leadership, collegial support, job design) on employees’ health [ 41 ]. The translation of this body of work undertaken in conventional office environments has not yet been undertaken in WAH and offers opportunities for further research.

Only one third of the studies ( n = 7) undertook separate analysis by gender on the impacts of WAH on health. The differences in health impacts may reflect traditional gender roles where males are perceived as ideal citizen workers whose primary focus is work, whilst for women dual roles exist in the work and domestic sphere which remains pervasive in many cultures [ 42 ]. The situation of WAH may challenge the ability to separate these roles, creating conflict due to the lack of physical distance enabled by undertaking work outside of the house. High levels of WFC are associated with negative outcomes, including poor mental and physical health [ 43 , 44 ], and it is plausible that for some females this is exacerbated by the WAH situation, contributing to the higher levels of exhaustion and stress reported by females [ 21 , 39 ] compared to males in WAH and, for some, increased unhappiness [ 34 ].

Implications for practice

Drawing on the evidence from the current rapid review, key themes were identified and are provided here as considerations to assist with developing optimal working conditions for employees WAH, including organisational support, co-worker support, technical support, boundary management support, and addressing gender inequities:

Organisational support