Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The Research Proposal

83 Components of the Literature Review

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- Understand what it is you want to do;

- Have a sense of your passion for the topic;

- Be excited about the study´s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important, and to whom or to what are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5-7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. As key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature Review

This is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal and it is a key component of the research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter V, “ The Literature Review ,” describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know how to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as one collects and/or analyzes the data and it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of the authors of this textbook´s research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally important, if not more so, to consider what methods have not been employed but could be. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section:

- Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and he way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

- Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually do the methods (i.e. coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research and describe how you will address these barriers.

- Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary suppositions and implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, new theoretical understanding, or a new method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what may benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic, environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how and in what ways you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.

The conclusion reiterates the importance and significance of your research proposal and it provides a brief summary of the entire proposed study. Essentially, this section should only be one or two paragraphs in length. Here is a potential outline for your conclusion:

- Discuss why the study should be done. Specifically discuss how you expect your study will advance existing knowledge and how your study is unique.

- Explain the specific purpose of the study and the research questions that the study will answer.

- Explain why the research design and methods chosen for this study are appropriate, and why other design and methods were not chosen.

- State the potential implications you expect to emerge from your proposed study,

- Provide a sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship currently in existence related to the research problem.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your research proposal. In a research proposal, this can take two forms: a reference list or a bibliography. A reference list does what the name suggests, it lists the literature you referenced in the body of your research proposal. All references in the reference list, must appear in the body of the research proposal. Remember, it is not acceptable to say “as cited in …” As a researcher you must always go to the original source and check it for yourself. Many errors are made in referencing, even by top researchers, and so it is important not to perpetuate an error made by someone else. While this can be time consuming, it is the proper way to undertake a literature review.

In contrast, a bibliography , is a list of everything you used or cited in your research proposal, with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem. In other words, sources cited in your bibliography may not necessarily appear in the body of your research proposal. Make sure you check with your instructor to see which of the two you are expected to produce.

Overall, your list of citations should be a testament to the fact that you have done a sufficient level of preliminary research to ensure that your project will complement, but not duplicate, previous research efforts. For social sciences, the reference list or bibliography should be prepared in American Psychological Association (APA) referencing format. Usually, the reference list (or bibliography) is not included in the word count of the research proposal. Again, make sure you check with your instructor to confirm.

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Let’s get to it! What should I do before writing the literature review?

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

Keep in mind that UNC Libraries have research guides and to databases relevant to many fields of study. You can reach out to the subject librarian for a consultation: https://library.unc.edu/support/consultations/ .

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing the literature review

Find a focus.

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Convey it to your reader

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine. More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

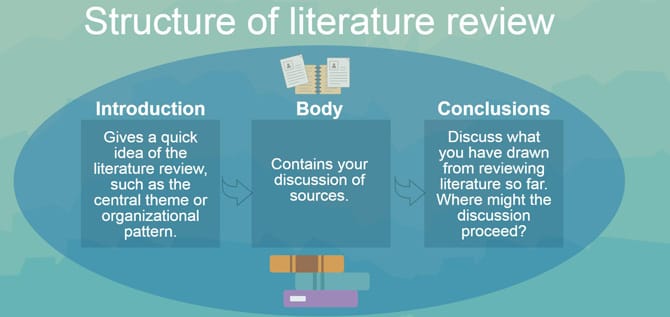

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Organizing the body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

- Chronological: If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

- By publication: Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

- By trend: A better way to organize the above sources chronologically is to examine the sources under another trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Under this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

- Thematic: Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a “chronological” and a “thematic” approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology.But more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as “evil” in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

- Methodological: A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the “methods” of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed. Once you’ve decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider:

- Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

Questions for Further Research: What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Begin composing

Once you’ve settled on a general pattern of organization, you’re ready to write each section. There are a few guidelines you should follow during the writing stage as well. Here is a sample paragraph from a literature review about sexism and language to illuminate the following discussion:

However, other studies have shown that even gender-neutral antecedents are more likely to produce masculine images than feminine ones (Gastil, 1990). Hamilton (1988) asked students to complete sentences that required them to fill in pronouns that agreed with gender-neutral antecedents such as “writer,” “pedestrian,” and “persons.” The students were asked to describe any image they had when writing the sentence. Hamilton found that people imagined 3.3 men to each woman in the masculine “generic” condition and 1.5 men per woman in the unbiased condition. Thus, while ambient sexism accounted for some of the masculine bias, sexist language amplified the effect. (Source: Erika Falk and Jordan Mills, “Why Sexist Language Affects Persuasion: The Role of Homophily, Intended Audience, and Offense,” Women and Language19:2).

Use evidence

In the example above, the writers refer to several other sources when making their point. A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be selective

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the review’s focus, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use quotes sparingly

Falk and Mills do not use any direct quotes. That is because the survey nature of the literature review does not allow for in-depth discussion or detailed quotes from the text. Some short quotes here and there are okay, though, if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Notice that Falk and Mills do quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. But if you find yourself wanting to put in more quotes, check with your instructor.

Summarize and synthesize

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. The authors here recapitulate important features of Hamilton’s study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study’s significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep your own voice

While the literature review presents others’ ideas, your voice (the writer’s) should remain front and center. Notice that Falk and Mills weave references to other sources into their own text, but they still maintain their own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with their own ideas and their own words. The sources support what Falk and Mills are saying.

Use caution when paraphrasing

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author’s information or opinions accurately and in your own words. In the preceding example, Falk and Mills either directly refer in the text to the author of their source, such as Hamilton, or they provide ample notation in the text when the ideas they are mentioning are not their own, for example, Gastil’s. For more information, please see our handout on plagiarism .

Revise, revise, revise

Draft in hand? Now you’re ready to revise. Spending a lot of time revising is a wise idea, because your main objective is to present the material, not the argument. So check over your review again to make sure it follows the assignment and/or your outline. Then, just as you would for most other academic forms of writing, rewrite or rework the language of your review so that you’ve presented your information in the most concise manner possible. Be sure to use terminology familiar to your audience; get rid of unnecessary jargon or slang. Finally, double check that you’ve documented your sources and formatted the review appropriately for your discipline. For tips on the revising and editing process, see our handout on revising drafts .

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Jones, Robert, Patrick Bizzaro, and Cynthia Selfe. 1997. The Harcourt Brace Guide to Writing in the Disciplines . New York: Harcourt Brace.

Lamb, Sandra E. 1998. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write . Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Troyka, Lynn Quittman, and Doug Hesse. 2016. Simon and Schuster Handbook for Writers , 11th ed. London: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

How to Write a Literature Review

What is a literature review.

- What Is the Literature

- Writing the Review

A literature review is much more than an annotated bibliography or a list of separate reviews of articles and books. It is a critical, analytical summary and synthesis of the current knowledge of a topic. Thus it should compare and relate different theories, findings, etc, rather than just summarize them individually. In addition, it should have a particular focus or theme to organize the review. It does not have to be an exhaustive account of everything published on the topic, but it should discuss all the significant academic literature and other relevant sources important for that focus.

This is meant to be a general guide to writing a literature review: ways to structure one, what to include, how it supplements other research. For more specific help on writing a review, and especially for help on finding the literature to review, sign up for a Personal Research Session .

The specific organization of a literature review depends on the type and purpose of the review, as well as on the specific field or topic being reviewed. But in general, it is a relatively brief but thorough exploration of past and current work on a topic. Rather than a chronological listing of previous work, though, literature reviews are usually organized thematically, such as different theoretical approaches, methodologies, or specific issues or concepts involved in the topic. A thematic organization makes it much easier to examine contrasting perspectives, theoretical approaches, methodologies, findings, etc, and to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of, and point out any gaps in, previous research. And this is the heart of what a literature review is about. A literature review may offer new interpretations, theoretical approaches, or other ideas; if it is part of a research proposal or report it should demonstrate the relationship of the proposed or reported research to others' work; but whatever else it does, it must provide a critical overview of the current state of research efforts.

Literature reviews are common and very important in the sciences and social sciences. They are less common and have a less important role in the humanities, but they do have a place, especially stand-alone reviews.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are different types of literature reviews, and different purposes for writing a review, but the most common are:

- Stand-alone literature review articles . These provide an overview and analysis of the current state of research on a topic or question. The goal is to evaluate and compare previous research on a topic to provide an analysis of what is currently known, and also to reveal controversies, weaknesses, and gaps in current work, thus pointing to directions for future research. You can find examples published in any number of academic journals, but there is a series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles. Writing a stand-alone review is often an effective way to get a good handle on a topic and to develop ideas for your own research program. For example, contrasting theoretical approaches or conflicting interpretations of findings can be the basis of your research project: can you find evidence supporting one interpretation against another, or can you propose an alternative interpretation that overcomes their limitations?

- Part of a research proposal . This could be a proposal for a PhD dissertation, a senior thesis, or a class project. It could also be a submission for a grant. The literature review, by pointing out the current issues and questions concerning a topic, is a crucial part of demonstrating how your proposed research will contribute to the field, and thus of convincing your thesis committee to allow you to pursue the topic of your interest or a funding agency to pay for your research efforts.

- Part of a research report . When you finish your research and write your thesis or paper to present your findings, it should include a literature review to provide the context to which your work is a contribution. Your report, in addition to detailing the methods, results, etc. of your research, should show how your work relates to others' work.

A literature review for a research report is often a revision of the review for a research proposal, which can be a revision of a stand-alone review. Each revision should be a fairly extensive revision. With the increased knowledge of and experience in the topic as you proceed, your understanding of the topic will increase. Thus, you will be in a better position to analyze and critique the literature. In addition, your focus will change as you proceed in your research. Some areas of the literature you initially reviewed will be marginal or irrelevant for your eventual research, and you will need to explore other areas more thoroughly.

Examples of Literature Reviews

See the series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles to find many examples of stand-alone literature reviews in the biomedical, physical, and social sciences.

Research report articles vary in how they are organized, but a common general structure is to have sections such as:

- Abstract - Brief summary of the contents of the article

- Introduction - A explanation of the purpose of the study, a statement of the research question(s) the study intends to address

- Literature review - A critical assessment of the work done so far on this topic, to show how the current study relates to what has already been done

- Methods - How the study was carried out (e.g. instruments or equipment, procedures, methods to gather and analyze data)

- Results - What was found in the course of the study

- Discussion - What do the results mean

- Conclusion - State the conclusions and implications of the results, and discuss how it relates to the work reviewed in the literature review; also, point to directions for further work in the area

Here are some articles that illustrate variations on this theme. There is no need to read the entire articles (unless the contents interest you); just quickly browse through to see the sections, and see how each section is introduced and what is contained in them.

The Determinants of Undergraduate Grade Point Average: The Relative Importance of Family Background, High School Resources, and Peer Group Effects , in The Journal of Human Resources , v. 34 no. 2 (Spring 1999), p. 268-293.

This article has a standard breakdown of sections:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Some discussion sections

First Encounters of the Bureaucratic Kind: Early Freshman Experiences with a Campus Bureaucracy , in The Journal of Higher Education , v. 67 no. 6 (Nov-Dec 1996), p. 660-691.

This one does not have a section specifically labeled as a "literature review" or "review of the literature," but the first few sections cite a long list of other sources discussing previous research in the area before the authors present their own study they are reporting.

- Next: What Is the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

University Library

Write a literature review.

- Examples and Further Information

1. Introduction

Not to be confused with a book review, a literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, providing a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

2. Components

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

3. Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself, however, does not present new primary scholarship.

- Next: Examples and Further Information >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.