- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2021

Change theory in STEM higher education: a systematic review

- Daniel L. Reinholz 1 ,

- Isabel White 1 &

- Tessa Andrews ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7008-6853 2

International Journal of STEM Education volume 8 , Article number: 37 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

19 Citations

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Commentary to this article was published on 05 September 2023

This article systematically reviews how change theory has been used in STEM higher educational change between 1995 and 2019. Researchers are increasingly turning to theory to inform the design, implementation, and investigation of educational improvement efforts. Yet, efforts are often siloed by discipline and relevant change theory comes from diverse fields outside of STEM. Thus, there is a need to bring together work across disciplines to investigate which change theories are used and how they inform change efforts. This review is based on 97 peer-reviewed articles. We provide an overview of change theories used in the sample and describe how theory informed the rationale and assumptions of projects, conceptualizations of context, indicators used to determine if goals were met, and intervention design. This review points toward three main findings. Change research in STEM higher education almost always draws on theory about individual change, rather than theory that also attends to the system in which change takes place. Additionally, research in this domain often draws on theory in a superficial fashion, instead of using theory as a lens or guide to directly inform interventions, research questions, measurement and evaluation, data analysis, and data interpretation. Lastly, change researchers are not often drawing on, nor building upon, theories used in other studies. This review identified 40 distinct change theories in 97 papers. This lack of theoretical coherence in a relatively limited domain substantially limits our ability to build collective knowledge about how to achieve change. These findings call for more synthetic theoretical work; greater focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion; and more formal opportunities for scholars to learn about change and change theory.

Introduction

Decades of research have shed light on changes that can improve teaching and learning in STEM higher education environments (Freeman et al., 2014 ; Laursen, 2019 ; Thiry et al., 2019 ). However, actually translating these discoveries into widespread reform remains challenging (Fairweather, 2008 ; Kezar, 2011 ). Recently, there has been increased attention to understanding how theory can be used to sustain change in STEM higher education. This shift in focus has been driven by a number of factors.

One major political factor relates to workforce development within the US economy. In particular, a report highlighting a shortfall of one million STEM graduates helped spring the community to action (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2012 ). The report highlighted that increasing STEM retention from 40 to 50% would address the projected shortfall. The report highlighted that while much is known about effective STEM learning and teaching environments, less is known about how to translate this knowledge into widespread change.

Second, considerable empirical evidence shows that “documentation and dissemination” approaches rarely achieve widespread change (Henderson et al., 2011 ; Kezar, 2011 ). This work has built community awareness of the limitations of developing new teaching techniques and curricula without attending to the complex systems, culture, and processes of change (Kezar, 2014 ; Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018 ).

Third, funding priorities for STEM education research reflect growing recognition for a systemic approach to change. Agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute are now requiring an explicit theory of change to explain how a project will achieve its desired results. These agencies expect researchers to draw on prior theory and research to inform their work (Reinholz & Andrews, 2020 ).

Beyond the above concerns, other pressures for change include concerns for equity, diversity, and inclusion; rapidly changing technology; and an increasingly global economy. Thus, while there is increased funding and support for STEM education research in the US, there are also increased expectations. Educational improvement does not happen in a vacuum, but in complex, historical, and evolving contexts (Kezar, 2014 ).

Catalyzing widespread change requires knowledge of how change happens. Specifically, researchers are attempting to develop collective knowledge by contributing to what we call change theory . For this manuscript, we define a change theory as a framework of ideas, supported by evidence, which explains some aspect of how or why systemic change in STEM higher education occurs, and is generalizable beyond a single project (Reinholz & Andrews, 2020 ).

Traditionally, scholarship about systemic change has happened in the domains of organizational change, business management, and higher education. Yet scholars of these fields typically do not have the same levels of entry and access to STEM learning environments that STEM Discipline-Based Education Research (DBER) scholars do. They also lack intimate knowledge about the differences between STEM disciplines and the resulting implications for change (Reinholz, Matz, et al., 2019 ). As such, DBER scholars have played a primary role in initiating and sustaining change efforts in STEM higher education, but many lack formal training in educational or organizational change. This has limited the field’s ability to productively use theory to build generalizable knowledge. Thus, DBER fields would benefit from an analytic review of relevant change theories. Such a review would enable DBERs to productively use one or more theories to guide their work to promote change and to study how it occurs.

Building upon theory is especially important in the study of change because most investigations of change in STEM higher education focus on a single initiative. Consequently, many investigations must be synthesized to identify larger patterns. These comparisons would be facilitated if researchers investigated common factors and used compatible change theories. Indeed, different theories can provide very different insights into a project’s outcomes, but secondary analyses of existing studies are difficult to perform due to lack of public access to the necessary details of a project and limitations of data collected from a particular theoretical perspective (Pilgrim et al., 2020 ). Moreover, STEM disciplines remain highly siloed. For example, many leading journals and conferences for disseminating research on change in STEM higher education are discipline-specific, limiting the degree to which new work builds on prior work. Thus, we see a need to bring together work across STEM disciplines to investigate which change theories are used and how. We hope to facilitate cross-disciplinary conversations, learning, and collaboration.

Goals and organization

Our overarching goal for this manuscript is to characterize how change theory is used in the growing body of research about systemic change in STEM higher education. We aim to support STEM-DBER scholars to make informed decisions about the design, development, implementation, and research of their educational improvement efforts. This will support DBER scholars who are actively researching change, and also newer scholars, by providing an accessible entry point. Currently, there are few succinct resources that can provide a general overview of change theory for newcomers.

The manuscript is organized as follows. We begin first by summarizing two major change research syntheses that precede this work. Then, we elaborate on the concept of theory of change (Anderson, 2005 ) to organize the systematic review of change theory that follows. After describing our methodological approach, we summarize change theories used to guide studies in STEM higher education. Our summary of each change theory begins with a brief overview of the theory itself, followed by a review of how the theory has been used. We close with emergent themes and implications for research and practice.

Background and framing

Prior work to synthesize research about change in stem higher education.

We build on two prior efforts to organize research relevant to change in STEM higher education. We briefly recount this prior work and articulate the novelty of this review.

Based on an analytic review of literature about facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices, Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) proposed a system to categorize strategies for achieving change in STEM higher education. They grouped change strategies along two dimensions: the aspect of the system to be changed (individual or environments/structures) and the nature of the intended outcome of change efforts (prescribed or emergent). The resulting four categories describe how change agents have aimed to reform instruction: disseminating curriculum and pedagogy, developing reflective teachers, enacting policy, and developing shared vision (Henderson et al., 2011 ). This organizational framework has been used as a guide to help researchers and practitioners think deeply about what different strategies can and cannot accomplish, to encourage efforts to use more than one strategy to achieve change, and to help the community employ common language and concepts to communicate about their change initiatives (Besterfield-Sacre et al., 2014 ; Borrego et al., 2010 ; DiBartolo et al., 2018 ).

Characterizing the use of change theory was not the focus of the Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) analytic review. Additionally, the four categories of change are not themselves a change theory as they do not explain how or why change occurs. Borrego and Henderson ( 2014 ) expanded upon the 2011 analytic review by describing the goals, assumptions, and logics that underlie the four change strategies. Their work was an important step toward focusing attention on the importance of explicit change theory to reform STEM higher education. We aim to build on this formative work. Our contribution uniquely focuses on the ways that researchers are using change theory to inform systemic change efforts and research.

Kezar ( 2014 ) also provides an extensive synthesis of research that is relevant to change in higher education. This work brings together decades of research in organizational learning, social sciences, and higher education, and describes six overarching change perspectives: scientific management, evolutionary, social cognition, cultural, political, and institutional. Each of these perspectives encompasses a broad body of research and theory, as well as particular approaches to achieving change. One key contribution Kezar ( 2014 ) makes is to extract fundamental principles about different perspectives. This makes dense scholarship from many different disciplines accessible to change agents who are making plans for action, but does not illuminate particular change theories that researchers can use to predict and study how change occurs. Our contribution describes specific change theories that have proven useful to change initiatives in STEM higher education and the ways in which these theories have contributed to reform efforts and research on these efforts.

Theory of change

We use the framing of theory of change to bring coherence to the numerous change theories used to guide systemic work in STEM higher education. A theory of change—a concept first developed in the evaluation literature—is an approach to design and evaluation that makes explicit how a particular project is actually supposed to make change happen (Anderson, 2005 ). A theory of change is tailored to a single change initiative by the project team and may be revised throughout a project’s lifecycle; in many ways, it is similar to a logic model. In contrast, the scope of a change theory goes well beyond a single change initiative and is designed to contribute to collective knowledge about how change occurs (Reinholz & Andrews, 2020 ). By engaging in projects with a well-developed theory of change that is grounded in change theory, it becomes easier to contribute to generalizable knowledge.

Developing a theory of change involves the following: determining the ultimate goals of the project, identifying shorter-term goals that need to be reached before the ultimate goals can be achieved, designing interventions to meet goals, honing rationales about how particular interventions will lead to desired goals, accounting for the context of change, determining how to evaluate the success of an initiative, and interrogating underlying assumptions. In this analytic review, we focus on four fundamental components of a theory of change: rationale and assumptions, context, indicators, and interventions.

Rationale and assumptions

Rationales describe ideas about how to actually make change happen. Rationales are the glue that brings together the other fundamental components of a theory of change. Rationales link interventions or experiences (if a directed intervention has not occurred) to the desired outcome. They also describe why particular interventions should be measurable with particular indicators, given the underlying context. Related to rationales are underlying assumptions. For instance, some projects may orient towards solving existing problems, while others focus on building a shared vision towards an imagined future that capitalizes on organizational strengths (e.g., Cooperrider & Whitney, 2001 ). The latter assumes that building and sustaining momentum for change requires an abundance of positive feelings like hope, excitement, and inspiration (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2001 ). As another example, a project may attempt to leverage data to convince a department to change their practices, which assumes that faculty and departments are rational decision-makers. Alternatively, a project could anticipate an emotional response and the need for ongoing sense-making. These underlying assumptions have implications for the rest of the project. Articulating assumptions is necessary to avoid relying on implicit ideas and hunches about how change occurs, especially in contexts that feel familiar (Kahneman, 2011 ).

The context of change in education is typically a complex and multifaceted landscape of actors and stakeholders, policies and practices, and the existing political climate (i.e., change efforts are context-specific; Lewis, 2015 ). Change theories can help describe how systems work, such as by explicating interactions between the parts and the whole of a system. They can also provide insights into specific parts of a change effort, for instance, by describing aspects of the particular system (e.g., a Historically Black College or University would function differently from a Primarily White Institution). Understanding the context is part of what makes STEM educational change unique from other types of change.

In a theory of change, a number of shorter-term goals—or preconditions—serve as waypoints to larger ultimate goals. Typically, a team develops indicators to assess progress towards these goals. Suppose a team is engaged in department-wide cultural transformation to increase the success of minoritized students. To measure progress toward the shorter-term goal of cultural transformation, the team might administer climate surveys, conduct student focus groups, or analyze departmental communications. Measuring achievement of the ultimate goal—increased student success—would require other indicators, such as course grades, persistence rates, or job placement after graduation for the target student population.

Importantly, the choice of indicators necessarily embodies a set of underlying values or assumptions. These example indicators of the ultimate goal (e.g., course grades, persistence) are but one metric of success. Alternative indicators include students’ quality of life, satisfaction with the program, and alumni engagement, each of which indicates another type of success.

Interventions

Interventions are the concrete things a project does to achieve its desired outcomes. A project may begin with a particular set of interventions and iteratively revise its approach in response to empirical data. Thus, a theory of change embodies a dynamic, rather than a static, approach to change. Research shows that disseminating curriculum and teaching techniques is common, but typically does not lead to widespread change. Thus, common intuitions about how to achieve change (e.g., simply show someone “the data”) are suspect and change agents need interventions grounded in change theory and research that can be customized to their particular goals and local context. There is no one-size-fits-all model, but particular interventions may be much more likely to succeed than others. Researchers continue to develop new interventions, and as the interventions are studied across contexts, they can be improved and better understood.

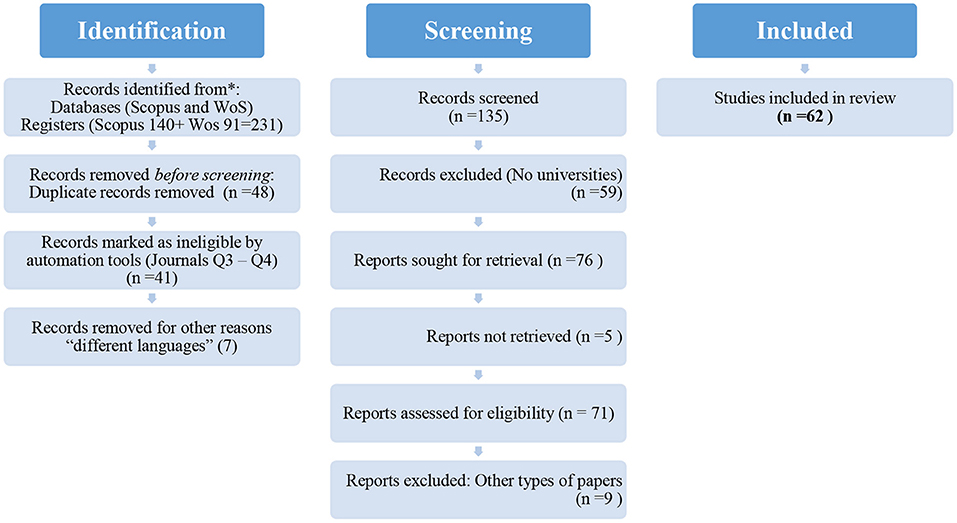

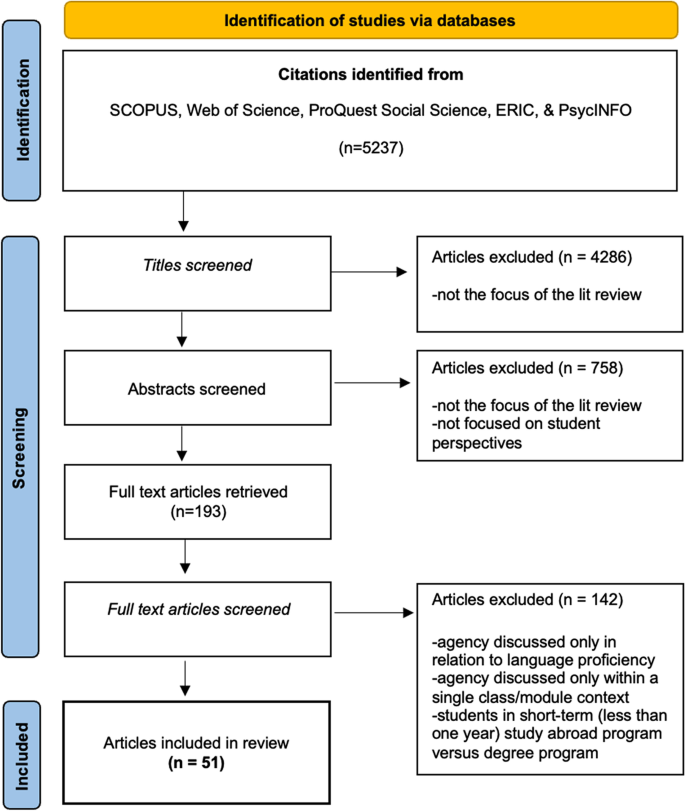

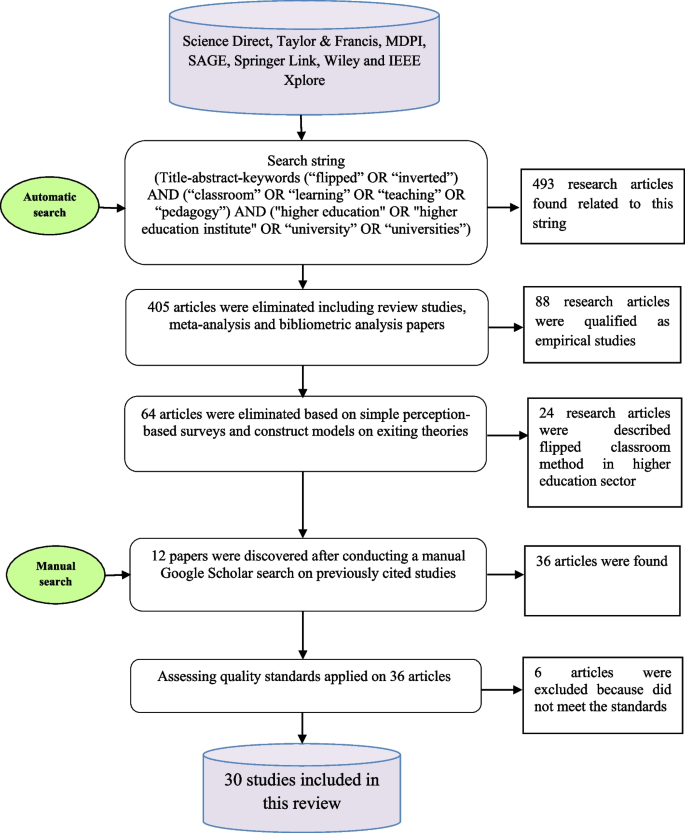

We followed a careful, methodological approach to identifying and reviewing articles to ensure that this systematic review would have valid results. We aimed to identify all peer-reviewed journal articles that drew on change theory to study systemic change in STEM higher education. We outline our process here. Given our goal to extend prior work, we used the methodological approach of Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) as a starting place.

Identifying articles

We limited our search to journal articles for a variety of reasons. First, journal articles represent peer-reviewed work deemed to be of sufficient quality for publication. Second, as a practical matter, it was most feasible to systematically survey journal articles, given the existence of databases. Journal publication also ensures that the work is accessible to academics, who are typically leading and studying change in STEM higher education. This decision compliments our goal of building a resource for researchers in this area. We note now, and elaborate later, that peer-reviewed articles do not fully represent the existing scholarship.

We used four approaches to build a collection of potentially relevant peer-reviewed articles. Our first corpus was the 191 articles published between 1995 and 2008 that were reviewed by Henderson et al. ( 2011 ). These articles were identified by the authors by searching Web of Science, PsychInfo, and ERIC. The original search terms included combinations of: “change,” “development,” “teaching,” “instruction,” “instructional,” “improvement,” “higher education,” “undergraduate,” “college,” and “university.”

We added a second corpus of potentially relevant articles published after 2008. We used the databases Web of Science, PsycInfo, ERIC, and Google Scholar. Our search terms included a combination of “STEM”, “change,” “reform,” and “higher education,” with each search engine producing hundreds of results. We set the date range of inclusion from 2008 to 2019 because our search was completed in January 2020. Given the recent proliferation of work in STEM educational change, we deliberately chose a more focused set of search terms related to STEM education to increase our likelihood of finding relevant articles. For Web of Science, Psych Info, and ERIC, we did an exhaustive search. We terminated searches in Google Scholar when the majority of the articles listed on a page did not focus on change in STEM higher education. We read titles and skimmed abstracts to determine if the articles identified in the search focused on change in STEM higher education. This second corpus yielded 198 potentially relevant articles.

We collected a third corpus through a reverse citation search of the Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) synthesis. Given the prominence of this work and the alignment between their goal of reviewing scholarship about how to promote instructional change in undergraduate STEM and our goal of reviewing the use of change theory in the same domain, we expected work that cited Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) to be highly salient. This approach, sometimes referred to as referential back-tracking (Alexander, 2020 ), yielded 12 additional articles.

A fourth and final corpus of potentially relevant articles was added by directly scouring (from 2008-2019) journals that publish DBER in one or multiple STEM disciplines (see Table 1 ). Our goal was to capture the premier journals in which STEM-DBER scholars publish their work in higher education. In addition, we included some potentially relevant journals mostly focused on K12 and science/STEM-general journals to broaden our search. We used more general terms for this narrower search, including “change” OR “reform” because the journals were already limited to STEM and often to higher education. This search resulted in 8 additional articles.

These four approaches produced an extensive collection of 409 articles on which to perform more in-depth analysis, including the original 191 from Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) published through 2008, and 218 published between 2008 and 2019.

Inclusion and exclusion of articles

We analyzed each paper to determine if it met our inclusion criteria. We read abstracts and skimmed and read papers as necessary. We worked collaboratively to make all inclusion determinations. We included peer-reviewed articles that were empirical, theoretical, or reviews. We excluded opinion pieces and essays, even if they were peer-reviewed, and methods papers presenting instruments and protocols. Essays can provide useful perspectives, but do not rely on change theory to inform change efforts or the investigation of change. Similarly, methods papers may describe valuable research tools and approaches, but generally are not grounded in theory and do not actually investigate change. We also excluded all conference proceedings, white papers, reports, and book chapters.

We included articles focused on change in STEM higher education. We excluded articles addressing change at the K12 level, articles studying preservice K12 teachers, articles that broadly examined faculty work or development (but not specifically teaching), and articles that were not specific to STEM environments. We considered an article focused on STEM if the authors explicitly named this focus or if the participants in the study were mostly STEM faculty or faculty in a particular STEM discipline (e.g., chemistry). In contrast, Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) included articles that were not STEM-specific, in part due to the dearth of STEM-specific studies at the time. Given that change efforts specific to STEM have become much more common in recent decades, we narrowed our focus to STEM higher education.

We excluded work that did not draw on change theory because our central goal was to analyze the use of change theory. We defined change theory broadly as a framework of ideas, supported by evidence, that explains some aspect of how or why systemic change in STEM higher education occurs, and that is meant to be generalizable beyond a single project. Terms like “theory,” “theoretical framework,” “framework,” and “model” are not consistently used in DBER communities or across the scholarly disciplines that contribute useful change theories. Thus, we could not rely on the terminology used by the developers or users of change theories to make distinctions. We erred on the side of inclusion, looking for evidence that a theory informed the design and study of systemic change.

In a few cases, we included papers that described work implicitly informed by change theory. For example, projects describing Faculty Learning Communities draw on prior work that is grounded in the Communities of Practice change theory, but not all of these articles cite this theory. We included these articles if they examined how faculty changed, as they provided insight into the use of theory in practice. We noted that only the most commonly used change theories (Diffusion of Innovations and Communities of Practice) seemed to implicitly influence projects, which likely results from the broad use of these theories in other contexts (e.g., Rogers, 2010 ; Tight, 2015 ).

We also excluded articles that only used learning theory (not change theory) to support faculty development. While these articles may be useful for considering faculty as learners, they do not take a systemic view of change that considers factors beyond individual instructors. For example, we excluded Trigwell and Prosser ( 1996 ), because it focuses narrowly on the relationship between an instructor’s intentions and their teaching strategies, without accounting for teaching in a broader context.

Applying these inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded 97 articles that were systematically analyzed. This included 81 articles published between 2009 and 2019 and 16 published between 1995 and 2008. The sharp decrease from 191 to 16 papers from the Henderson et al. ( 2011 ) review was primarily due to the exclusion of articles that did not use change theory or were not STEM-specific. Our final collection of 97 articles included some that investigated change interventions and others that examined change separate from a specific intervention.

Analyzing articles and synthesizing results

We collaboratively analyzed each article to characterize the use of change theory. At least two authors reviewed each paper to determine which change theory or theories informed the work and how. Specifically, for each article, we determined whether and how change theory had informed the rationale and assumptions about how change occurs, the way that the context of change was conceptualized and examined, any interventions undertaken, and the indicators that researchers used to determine if change had occurred. After analyzing all articles, we split the corpus of articles into separate groups by underlying theory. Then, one or more authors reviewed each group in its entirety and began drafting a written summary for each manuscript in the group. We limited our analysis to what the article authors described in their published work, to avoid excessive inferences, even though change theory may have informed their work in ways not explained in publications.

We ultimately generated detailed summaries for every change theory ( N = 8 change theories) that was used by three or more articles ( N = 66 articles), created a list of every theory used just in one or two articles ( N = 23 articles), and determined which papers created their own change theory ( N = 11). These numbers total to more than 97 because 3 papers used a theory from two of the above categories. Finally, after summarizing all of the articles under each change theory, we performed a synthesis across theories to identify emergent themes. Table 2 provides a list of all theories used and their prevalence across the 97 analyzed articles.

Limitations

As with any systematic review, we cannot ensure that we found every relevant article, but we are confident that we have been able to identify the most commonly used theories and other less commonly used theories that may have value for future work. By focusing on STEM higher education, we have omitted potentially relevant theories from other contexts. Thus, we encourage DBER scholars to draw on research beyond that in STEM higher education.

We frame our review using a theory of change framework to attend to how change theory can inform change efforts and research. This framing also compliments the expectations of funding agencies, which increasingly call for initiatives to build a project-specific theory of change that is informed by existing knowledge about how to engender change (i.e., change theory). Nonetheless, we recognize that using a different framework may have led to different insights.

Lastly, we reviewed peer-reviewed articles, which do not fully represent the existing scholarship. Given the lag time between project funding, practical implementation, and scholarly publication, it is not possible for us to document the latest cutting-edge examples of change efforts and research. Rather, our approach centers on existing scholarship and privileges researchers who have access to shepherd their work to this type of publication. Important work leveraging change theory is also present in reports, white papers, dissertations, books, and conference proceedings. Although we do not review books or reports specifically, a number of theories that we reference in this review were actually written about most extensively in books, such as Diffusion of Innovations (Rogers, 2010 ) or Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998 ). Thus, our review provides insight into whether potentially relevant theories published in books or reports actually impact the scholarship published in peer-reviewed journals.

Here, we present the eight theories most commonly used to support STEM higher educational change research. We begin by summarizing each theory, to provide an introduction for those new to the theory, and then describe how the change theory informed projects’ rationales and assumptions, conceptualizations of context, indicators of change, and intervention design. Table 3 provides a brief overview. We also briefly discuss rarely used theories and cases where authors generated their own theories, but we do not summarize these articles in depth. Although we describe each theory separately here, we do not advocate that a project relies on only one theory. We return to this point in our discussion.

Community of Practice (CoP; 26 articles)

Communities of Practice (CoPs) was the most commonly used theory (Wenger, 1998 ). This change theory views learning as situated and participatory (Lave & Wenger, 1991 ). A CoP is a group of people—with a common interest—who regularly interacts to more deeply engage with their practice. A CoP is defined by (1) a shared domain of interest, (2) a community of joint engagement, and (3) a shared repertoire of practices (Wenger, 1998 , p. 73). These factors constitute a social network through which ideas and expertise are collectively developed and shared. CoPs have cultures and ways of belonging to the community, including practices, norms, values, and discourses (Wegner & Nückles, 2015 ). Members of a CoP tend to start as legitimate peripheral participants, and as they deepen their expertise, they become more central. Individuals may participate in multiple CoPs and thus may act as brokers of knowledge between CoPs.

A typical lifecycle of a CoP has five stages: (1) potential, (2) coalescing, (3) maturing, (4) stewardship, and (5) transformation (Wenger et al., 2002 ). The potential phase involves initial conversations about forming a community. Coalescing is the official formation of a CoP. Maturation occurs as the CoP develops formal structures and organization. Stewardship occurs as the CoP responds to changing circumstances, technology, and challenges. Finally, transformation can result in a radical shift or disbandment of a CoP. While change in a CoP is inevitable, the nature of such change is shaped by the response of community members.

Researchers have also extended the theory of a CoP to think specifically about change. A Community of Transformation , or CoT, works across institutions and is characterized by (1) a compelling philosophy that deeply rethinks STEM education, (2) particular events and structures to help members interact, and (3) mentorship structures that support faculty back at their home institution and foster leadership within the community (Gehrke & Kezar, 2016 ). In this way, a CoT is a particular type of CoP with structures designed to support instructional change for faculty who have less-than-supportive conditions in their home departments.

Faculty Learning Communities (FLCs) are a form of teaching professional development that are often based on Communities of Practice. Specifically, FLCs assume that learning is socially constructed and situated within a particular context, a foundation of CoP as a change theory (Wenger et al., 2002 ). An FLC is formed with the particular focus of improving pedagogical practices (Cox, 2001 ). An FLC may focus on a particular course, technology, or teaching techniques, or it may be a more general space focused on pedagogical improvement. An FLC meets for an extended period of time, typically at least a year. Through regular meetings, faculty members build community, deepen their teaching practices, and engage in sustained professional learning. Unlike a disciplinary CoP (e.g., the community of mathematicians), an FLC is temporary, often facilitated through a Center for Teaching and Learning, and designed to improve instruction on a given campus.

The vast majority of articles that used CoPs drew loosely on the theory, typically centering on the idea of learning through participation (Dalrymple et al., 2017 ; Herman et al., 2015 ; Pelletreau et al., 2018 ). These articles did not focus on particular features of a CoP that may support or inhibit change. Most likely the broad use of CoPs as a change theory was in part because it is flexible, at times loosely defined, and could seem relevant in a variety of situations (e.g., Tight, 2015 ). This flexibility also meant that many articles invoked the concept of a CoP without a deep connection to theory.

There were a few exceptions, where researchers drew upon explicit features of a CoP to support and understand change. For instance, Tinnell et al. ( 2019 ) considered what features of a CoP could support pedagogical improvement. Their design built on the emergent nature of a CoP to support faculty by providing them with a sense of ownership, continuous communication, reflection, and expertise building (Tinnell et al., 2019 ). Other studies also aimed to understand the features and design considerations that contributed to positive outcomes in CoPs (e.g., Gehrke & Kezar, 2019 ; Kezar & Gehrke, 2017 ; Ma et al., 2019 ). In one study, the five stages of a CoP lifecycle were used to understand how a CoP operates (Bernstein-Sierra & Kezar, 2017 ). Yet another article drew on the concept of brokering to look at the intersections between disciplinary and pedagogical communities (Clavert et al., 2018 ). Finally, other work focused on CoTs in an attempt to build a richer theoretical base for a particular type of CoP. CoTs create spaces for faculty to substantially transform their teaching with support from outside of their local context (Bernstein-Sierra & Kezar, 2017 ; Gehrke & Kezar, 2016 , 2019 ).

Because of its community focus, theory around CoP does not necessarily draw attention to institutional structures, or how to change them. Projects using CoPs often conceptualize context in terms of the community and its three defining features: (1) domain of knowledge, (2) community of individuals, and (3) shared repertoire of practices (Bernstein-Sierra & Kezar, 2017 ; Clavert et al., 2018 ). This conceptualization helped projects define the membership boundaries of the CoP. While some articles acknowledged that change takes place within institutional contexts (e.g., Addis et al., 2013 ; Clavert et al., 2018 ), these contexts were not thoroughly conceptualized. The one exception was Gehrke and Kezar ( 2017 ), who examined how CoTs contributed to departmental and institutional STEM reform, including the CoT design features most important for these larger contextual changes.

A sizeable proportion of work utilizing CoPs studied the impact of an FLC on faculty thinking and teaching (e.g., Nadelson et al., 2013 ; Pelletreau et al., 2018 ; Tomkin et al., 2019 ). These studies used observation protocols, teaching artifacts, surveys, interviews, and custom assessments. Typically, authors did not explain whether or how CoP theory informed indicators.

Another set of studies used Social Network Analysis (SNA) to look at interactions among faculty. Some papers examined the relation between a CoP’s structure and efficacy (Ma et al., 2019 ; Shadle et al., 2018 ). One study used SNA to examine which faculty communicated with each other about teaching and what they discussed. What they learned informed the interventions they designed for the CoPs they aimed to build (Quardokus Fisher et al., 2019 ). These studies were loosely connected to the importance of community in a CoP but did not draw on specific features of a CoP to guide their analysis. A few studies, however, did draw on particular CoP constructs to guide data collection and analysis. For example, one survey study drew on previously researched desirable design features of a CoP (Gehrke & Kezar, 2019 ). Finally, one study used CoP constructs (practice, meaning, identity, and community) to analyze community development (Clavert et al., 2018 ).

There were essentially two categories of studies that drew upon CoPs to inform interventions. Most studies focused on the creation of an in-person or online CoP (typically in the form of an FLC) to create some desired change (e.g., Addis et al., 2013 ; Dancy et al., 2019 ; Elliott et al., 2016 ; Hollowell et al., 2017 ; Mansbach et al., 2016 ; Marbach-Ad et al., 2010 ). These studies drew loosely on CoP theory to design interventions (e.g., learning through participation). In fact, some studies did not discuss CoPs at all, drawing instead on literature about FLCs (Cox, 2004 ), which itself draws only loosely on CoPs.

A smaller subset of articles did not focus on creating an intervention, but rather studying CoPs that had already existed for some time (e.g., Bernstein-Sierra & Kezar, 2017 ; Gehrke & Kezar, 2016 ; Shadle et al., 2018 ). These studies tended to draw more extensively on CoP as a change theory.

Diffusion of Innovations (DoI; 19 articles)

Diffusion of Innovations (DoI; Rogers, 2010 ) was another commonly used theory. DoI describes how new ideas, technologies, or other innovations become more widely used. The theory posits that innovations spread amongst adopters over time through particular communication channels that exist within a social system. Each of these constructs is conceptualized within the theory.

DoI describes how change unfurls as a process over time rather than a one-time event. Rogers ( 2010 ) outlines five stages in this process: (1) knowledge, (2) persuasion, (3) decision, (4) implementation, and (5) confirmation/continuation. In the knowledge stage an individual develops awareness of an innovation, how it is used, and what its impact might be. This knowledge typically develops either through formal communication (e.g., media, publications, workshops) or personal interactions. The theory distinguishes between awareness, how-to, and principles knowledge. Awareness knowledge is simply knowing that an innovation exists. How-to knowledge allows an individual to correctly use an innovation. Principles knowledge goes deeper and involves how and why an innovation works. An adopter could use an innovation successfully without principles knowledge, but might also adapt an innovation in a way that undermines its utility. During the persuasion stage, an individual decides whether or not to adopt an innovation. The adopter’s perception of an innovation’s characteristics influences how likely they are to adopt it. The next stage involves a decision about whether to use an innovation. The fourth stage involves implementing an innovation, which may be done with fidelity, or adaptation. Finally, in the fifth stage, an individual reflects on the implementation of the innovation, seeking reinforcement for the decision to implement. If they encounter conflicting information or experiences regarding the innovation, they may discontinue use.

DoI proposes specific innovation characteristics that influence adoption: (1) a relative advantage over current practices; (2) compatibility with existing beliefs and practices; (3) simplicity; (4) a low barrier for “trialability,” which allows one to see if they like it or not; and (5) observability of use before adoption. Importantly, DoI has evolved over time and now it is widely accepted that many users reinvent an innovation rather than adopting it wholesale (Rogers, 2010 ). This phenomenon has been further theorized in the context of STEM higher education by Henderson and Dancy ( 2008 ), as described below.

DoI also hypothesizes conditions related to adoption (Rogers, 2010 ). Previous practice with an innovation; needs, problems, and dissatisfactions that might be addressed by the innovation; and the norms of the social system that align with an innovation may all make an adopter more likely to enter into the stages of adoption.

Lastly, there are different categories of adopters: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Each group has different characteristics. For example, innovators are most willing to take risks to try new things. This contrasts with a late majority or laggard, who is only likely to adopt an innovation after the majority already has. Given these categories, different strategies may be used depending on the target of the desired change. Typically, once enough people have begun to adopt an innovation, the spread is assumed to be self-sustaining without external effort.

Different research projects drew upon various aspects of DoI, and none drew upon the theory as a whole. Most commonly, researchers used the stages of innovation adoption to analyze faculty adoption of evidence-based instructional practices (e.g., Andrews & Lemons, 2015 ; Foote, 2016 ; Henderson, 2005 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ; Marbach-Ad & Hunt Rietschel, 2016 ) or the current status of adoption in a larger population (e.g., Borrego et al., 2010 ; Henderson et al., 2012 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ). Building on the stages of change, a handful of research projects aimed to better understand the prior conditions for STEM faculty to consider change. This work focused exclusively on the role of dissatisfaction with existing teaching strategies as a prerequisite to change (e.g., Andrews & Lemons, 2015 ; Marbach-Ad & Hunt Rietschel, 2016 ; Pundak & Rozner, 2008 ). Only one study considered whether faculty had appropriate how-to and principles knowledge and observed the consequences of lacking this knowledge (Foote, 2016 ). This study also considered different types of adopters (Foote, 2016 ). Finally, some researchers drew upon yet another aspect of DoI, the idea that innovations that were highly likely to diffuse had particular characteristics or “innovation attributes” (Foote et al., 2014 ; Henderson, 2005 ; Macdonald et al., 2019 ).

Separate from stages of change, a handful of studies relied on communication channels and the role of these channels in STEM faculty awareness of and adoption of evidence-based practices. Researchers particularly focused on faculty social networks as important informal communication channels for learning about evidence-based instructional practices (e.g., Andrews et al., 2016 ; Knaub et al., 2018 ; Lane et al., 2019 ). Other researchers investigated the role of both formal and informal channels (e.g., Borrego et al., 2010 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ).

Despite, or perhaps as a result of, the widespread use of DoI, there is also a body of research criticizing this paradigm and suggesting new and revised change theory. Researchers offered an alternative, the propagation paradigm, which builds upon and extends diffusion for the context of STEM higher education (Froyd et al., 2017 ; Khatri et al., 2015 ; Stanford et al., 2016 ). The fundamental argument for propagation is that design and diffusion is insufficient. Rather, to increase the likelihood that a new innovation or pedagogical practice is taken up broadly, there are particular considerations: design needs to take place in communication with stakeholders, spreading the innovation requires action, and innovation adopters need support (Froyd et al., 2017 ). Moving beyond the idea that faculty adopt a new teaching strategy as is, Henderson and Dancy ( 2008 ) proposed an adoption-innovation continuum that recognizes the role of both an original developer and an adopting instructor in the change process. Similarly, two papers emphasized an iterative version of the stages of change in which faculty make a small change, reflect on it, seek new knowledge, adapt their approach, reflect, and again seek new knowledge (e.g., Andrews & Lemons, 2015 ; Marbach-Ad & Hunt Rietschel, 2016 ).

Context was mostly absent from studies that used DoI, since this theory focuses primarily on individual actors. Nonetheless, some articles acknowledged the relevance of local context (Froyd et al., 2017 ). Still, this acknowledgement was not always coupled with a deep characterization of that context or its role in change. Researchers may draw on other theories in addition to DoI to provide a lens for examining context, such as the teacher-centered systemic reform model (e.g., Lund & Stains, 2015 ) or the influence of social networks on norms (Lane et al., 2019 ).

A primary goal of DoI research was to understand the process by which new pedagogical innovations were actually being taken up. Thus, the indicators used focused on faculty practices. Some studies created surveys to track awareness and use of pedagogical strategies (Borrego et al., 2010 ; Henderson & Dancy, 2011 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ) and others used interviews to query the experiences of faculty (e.g., Andrews & Lemons, 2015 ; Foote et al., 2014 ; Henderson, 2005 ; Marbach-Ad & Hunt Rietschel, 2016 ). The adoption-innovation continuum, an extension of DoI, was sometimes used as an analytic lens for making sense of how innovations diffused (Foote, 2016 ; Henderson et al., 2012 ). Although less frequent, some researchers used SNA to operationalize constructs like “opinion leaders” or “champions,” from DoI (Andrews et al., 2016 ; Knaub et al., 2018 ).

DoI as a theory does not highlight a specific intervention or type of interventions for spreading innovations. Accordingly, most of the reviewed research focused on tracking the use of existing pedagogical innovations, rather than trying to actively spread new innovations (Borrego et al., 2010 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ). Still, there were a few examples where research projects used DoI to inform their interventions. For instance, a handful of studies used the idea that interactions between colleagues spread ideas as a part of their rationale/strategy for spreading ideas (Froyd et al., 2017 ; Khatri et al., 2015 ). One project planned teaching professional development based on the innovation characteristics that facilitate adoption (Macdonald et al., 2019 ). At least one study drew on the theory more extensively to plan and carry out a college-level initiative to change instruction, focusing especially on how to raise awareness and persuade faculty to make a mandated change (e.g., Pundak & Rozner, 2008 ).

Teacher-Centered Systemic Reform (TCSR, 6 articles)

Teacher-Centered System Reform (TCSR) focuses on the interrelation between a teacher’s practices and thinking as embedded within a larger system (Woodbury & Gess-Newsome, 2002 ). Thinking and practices relate to teaching and teaching roles, students and learning, schooling and schools, the content being taught, and dissatisfaction with current practices (as a catalyst for change). The larger context includes personal factors (i.e., the demographic profile, teaching experience, preparation, and continued learning), contextual factors (cultural context, school context, department/subject area context, and classroom context), as well as general context of reform. TCSR posits that this system as a whole, and its individual parts, requires attention.

Despite its attention to the larger system and its interacting parts, TCSR is fundamentally about teacher change as the source of larger changes within a schooling system. Thus, teacher thinking and practice are the primary focus of TCSR. Teaching thinking is posited to have three key characteristics: (1) it is comprised of interconnected cognitive (knowledge) and affective domains (beliefs), (2) knowledge and beliefs may not always be precisely disentangled, and (3) beliefs are resistant to change, even in the face of disconfirming evidence.

Most papers using TCSR used teacher thinking as a mechanism to change practices (Birt et al., 2019 ; Ferrare, 2019 ; Stains et al., 2015 ). Individual instructors—not broader systems—were the primary unit of change. Thus, although TCSR attends to the broader systemic context as a major influence on teacher thinking and practice, this was not used extensively by researchers. Nonetheless, some papers explicitly nested teacher thinking and practice within a larger context and operated under the assumption that context is key to change (e.g., Lund & Stains, 2015 ).

Although TCSR attends to contextual factors at multiple levels of change, not all papers used this central aspect of the theory. In some studies, the contextual factors of TCSR were largely ignored. In these cases, although it was acknowledged that thinking and practices are embedded in larger contexts, the context was peripheral, not central, to the study (Ferrare, 2019 ; Stains et al., 2015 ). Other studies focused extensively on the contextual features of the classroom environment but had less of a focus on broader structures (Birt et al., 2019 ). Three studies drew on TCSR to define and investigate the nested contexts in which reform occurs: classroom, department, university, disciplinary culture (Enderle et al., 2013 ; Gess-Newsome et al., 2003 ; Lund & Stains, 2015 ).

Studies generally relied extensively on TCRS to from data collection and analysis. Most commonly, the indicators used by these studies were particular changes in teachers’ beliefs and practices. Because TCSR does not have specific instruments designed to measure its constructs, research projects used aligned measures. For example, some projects used existing surveys and classroom observation protocols to capture instructor beliefs and practices (Ferrare, 2019 ; Stains et al., 2015 ). When engaging in qualitative analyses, projects developed broad codes related to themes coming from TCSR (Birt et al., 2019 ; Enderle et al., 2013 ; Gess-Newsome et al., 2003 ).

TCSR does not prescribe any particular interventions and was not used to deeply inform interventions. In some studies, TCSR was used as an analytic framework to make sense of other, unrelated interventions (Enderle et al., 2013 ; Ferrare, 2019 ). In other studies, authors described only general relationships between TCSR and their intervention, for instance, changing instructor thinking and practices (Birt et al., 2019 ; Stains et al., 2015 ). In these projects, the interventions focused on individual instructors, not on larger systemic factors.

Appreciative Inquiry (4 articles)

Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider et al., 2008 ) is a change theory that assumes change should start with what is positive in an organization. Appreciative Inquiry is organized around a 4D cycle: Discovery, Dream, Design, and Destiny, which supports a change team to build a results-oriented vision (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2001 ). In contrast to a typical problem-solving approach, Appreciative Inquiry is guided around what outcomes a group hopes to achieve. An outcome focus draws attention to “what is wanted,” in contrast to a more typical focus on the problems or “what is wrong.” A typical outcome-focused cycle has four steps: (1) determining values, (2) developing a vision, (3) setting goals, and (4) taking actions and sustaining improvements. Although these steps are listed in a linear fashion, these processes are interrelated, and individuals may revisit many steps of the process in a nonlinear fashion.

Appreciative Inquiry draws attention to positive outcomes to achieve rather than problems to be solved. This guiding rationale could be seen in all articles that utilized Appreciative Inquiry (Nemiro et al., 2009 ; Quan et al., 2019 ; Reinholz et al., 2017 ; Reinholz, Pilgrim, et al., 2019 ). For example, in the Departmental Action Team (DAT) project, this focus on positive outcomes was used to help a science department to create new, ongoing instructor positions to guide curricular integration, rather than attempting to “solve” the problem of a disjointed curriculum through a singular event or process (Reinholz et al., 2017 ).

None of the articles reviewed used Appreciative Inquiry to consider the context of change. This absence is not surprising because this change theory does not set clear boundaries for the key contextual factors for an organization.

Appreciative Inquiry only provides loose guidance on what data would be collected and analyzed, relating to the positive visioning process. For example, Nemiro et al. ( 2009 ) reported on the results for 4D focus groups to discuss the strengths of recruiting STEM women faculty. None of the other three articles utilized the theory to support indicators.

Appreciative Inquiry is an intervention for organizational change. This is consistent with how it was used by STEM educational change researchers—primarily as a tool to support change. For example, Nemiro et al. ( 2009 ) used Appreciative Inquiry 4D cycles as a guiding strategy for improving the retention and recruitment of women faculty on one campus. Appreciative Inquiry was also a guiding principle for the Departmental Action Team (DAT) project (Quan et al., 2019 ; Reinholz et al., 2017 ; Reinholz, Pilgrim, et al., 2019 ). While the DATs did not utilize the 4D cycle directly, they used their own modified approach to visioning, goal setting, and implementation, based on Appreciative Inquiry principles.

Expectancy-Value Theory (4 articles)

Expectancy-Value Theory is a theory of motivation that explains why faculty may choose to change their instructional practices. Expectancy-Value Theory posits that individuals engage in a given task if they expect to succeed (expectancy) and see value in the task. Expectancy is closely related to self-efficacy and deals with individuals’ perceptions of their ability to successfully complete the task (Eccles et al., 1983 ; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002 ). The overall value an individual anticipates for a task may consider multiple components, including interest value, which is the enjoyment an individual experiences or expects to experience by engaging in the task; utility value, which is the direct benefit of the task for the individual’s goals; attainment value, which captures the importance of doing well on the task to an individual’s identity; and perceived cost, which is what the individual has to give up to complete the task (e.g., time).

Researchers have used Expectancy-Value Theory to investigate what influences STEM faculty decisions about instruction, especially the adoption of evidence-based strategies (e.g., Finelli et al., 2014 ; Matusovich et al., 2014 ; Riihimaki & Viskupic, 2020 ) and to explain their motivation to participate in long-term teaching professional development (McCourt et al., 2017 ). This work characterized how the factors that faculty report influencing their decisions align with expectancy and values and tended to draw heavily on theory. For example, faculty desire more opportunities to develop knowledge in order to feel like they can succeed using new teaching strategies (e.g., Finelli et al., 2014 ; Matusovich et al., 2014 ).

All papers using Expectancy-Value Theory to study faculty motivation discovered contextual factors influencing motivation. Most commonly, faculty reported that the culture and environment in which they worked did not encourage changing instructional practices (e.g., Riihimaki & Viskupic, 2019 ). Because these tasks were not valued nor rewarded, faculty perceived low utility value. Investing time to use evidence-based teaching strategies would not help them achieve key goals like tenure (Finelli et al., 2014 ). Thus, Expectancy-Value Theory was useful in considering the influence of context on individual decision-making.

Expectancy-Value Theory outlines components that contribute to motivation to act. In two of the studies, researchers described their indicators as being informed by Expectancy-Value Theory (Finelli et al., 2014 ; McCourt et al., 2017 ). Specifically, Expectancy-Value Theory informed the questions researchers posed to faculty in interviews and focus groups. The other two papers reviewed described Expectancy-Value Theory only as a lens used to interpret data (Matusovich et al., 2014 ; Riihimaki & Viskupic, 2019 ).

Just one of the reviewed articles described designing an intervention that was informed by Expectancy-Value Theory. Finelli et al. ( 2014 ) drew on insights about faculty motivation in their local context, discerned from focus groups, to create a plan for supporting faculty pedagogical change. For example, researchers discovered that faculty were concerned about student reaction and would value evidence-based practices to which students responded positively (Finelli et al., 2014 ). Therefore, they planned to include an opportunity for participants to review and act on midterm student feedback in their faculty development program.

Four Frames (4 articles)

Four Frames helps make sense of issues in an organization from four different lenses: structures, symbols, people, and power (Bolman & Deal, 2008 ). Structures are the formal roles, practices, routines, and incentives that guide and limit interactions within an organization. Symbols are language, beliefs, and ways of sensemaking that provide a common language for members of the organization. People are individuals who have their own goals, needs, and agency. Finally, power relations within an organization exist as a result of status, hierarchies, and political coalitions. From the perspective of a change agent, each of these frames outlines a set of possible levers that can be used to enact change. Bolman and Deal ( 2008 ) assume that most leaders typically use a single frame through which they view most issues. This leads to a level of inflexibility, and often missing the bigger picture. To address this issue, leaders can explicitly attend to multiple frames simultaneously.

The Four Frames change theory assumes it is necessary to use multiple perspectives (i.e., frames) to understand or design a change process. This theory was taken up by a common set of researchers, who used Four Frames as a way to operationalize culture, and thus inferred that culture is a key construct to attend to as a part of an organizational change process (Rämö et al., 2019 ; Reinholz, Matz, et al., 2019 ; Reinholz, Ngai, et al., 2019 ; Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018 ).

Four Frames drew attention to various features of an organization (i.e., the organizational context). In a number of projects, the department was conceptualized as the unit of change, and thus the frames were used to operationalize the department’s culture (Rämö et al., 2019 ; Reinholz, Matz, et al., 2019 ; Reinholz, Ngai, et al., 2019 ; Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018 ). Across the research articles, the ability to make sense of a complex institutional/organizational context was a strength of the Four Frames change theory.

Four Frames characterizes key aspects of change broadly but does not provide particular indicators to attend to. Perhaps then, it is not surprising that none of the articles reviewed used the four frames to guide their data collection. Nonetheless, all of the articles that did include data analysis used four frames as an analytic lens for interpretation (e.g., Rämö et al., 2019 ). Again, one of the key strengths of Four Frames was providing different lenses for making sense of particular change-related phenomena.

As a change theory, Four Frames does not prescribe particular interventions, and none of the articles reviewed used Four Frames to guide the development of their interventions.

Paulsen and Feldman’s General Change Model (4 articles)

Paulsen and Feldman proposed a “General Change Model” of instructional improvement that placed the process of change within a teaching culture. Their model is grounded in work by Lewin ( 1947 ) and Schein ( 2010 ). Lewin is credited with the idea that achieving meaningful and sustained change requires three components (unfreezing, changing, and refreezing), though there is dispute about whether this credit is warranted (Cummings et al., 2016 ). Unfreezing involves recognizing an incongruence between the outcomes of one’s current thinking and behavior and the outcomes that one sees as aligning with their self-image. This often involves feelings of guilt, anxiety, or inadequacy. Therefore, unfreezing also relies on an individual feeling safe and being able to envision a change they can make that will re-establish a positive self-image (Paulsen & Feldman, 1995 ). In short, unfreezing creates motivation to change, which leads to the next stage, actually engaging in change. Change involves searching out new ideas and information, developing new attitudes and behaviors. This is a stage of learning, trying new things, and reflecting. Teaching professional development is often best suited to support instructors in this stage. The final stage is refreezing, which ensures that change is sustained. This stage recognizes that new behaviors are most likely to be maintained when they align with an individual’s identity and restore a positive self-image and when they are validated by others because they sufficiently align with the culture (Paulsen & Feldman, 1995 ). If the local culture does not support the change, an instructor may need a new community to provide ongoing information, ideas, support, and validation. Lewin’s studies ( 1947 ) suggested that changes resulting from group discussions last longer than changes resulting from individual actions.

The stages of change adapted by Paulsen and Feldman ( 1995 ) share clear similarities with the Diffusion of Innovation model, involving early stages of dissatisfaction, actions to learn and act, and then confirmation to solidify new changes. Paulsen and Feldman ( 1995 ) tailor their model specifically to college faculty, emphasize what it takes to motivate change (unfreezing), and consider refreezing to be key to sustained change. Researchers could easily synthesize these two models to inform studies of individual change.

Paulsen and Feldman ( 1995 ) place these stages of change in the context of interpersonal relationships and organizational culture. They outline relationships that may provide feedback that informs the change process, including those with students, colleagues, consultants, chairs, and one’s self. They also emphasize that teaching culture can influence all stages of change.

Notably, this change theory was developed specifically for STEM higher education, which is not true of any of the theories described above. One limitation of its specialization to STEM higher education is that it has not been refined and expanded in other domains. As a result, this theory provides fewer details on which researchers and change agents can draw.

Studies that relied on this change theory focused on understanding what contributes to instructors moving through the three stages of change: unfreezing, changing, and freezing. Two studies of the same teaching professional development program aimed to understand unfreezing, especially what helped instructors envision how they might change their teaching in a way that was consistent with their self-image (Hayward et al., 2016 ), and how a group email listserv supported refreezing (Hayward & Laursen, 2018 ). Thus, this work operated with the rationale that motivation to change is necessary to transition from stagnation to action.

Though Paulsen and Feldman ( 1995 ) place the stages of change within the context of the larger teaching culture, this was not a central focus of the reviewed studies. Most did not consider the context of change in light of the theory. One study recognized the role of a listserv in creating a community supportive of changed practices for faculty lacking a supportive local community but did not consider context more extensively (Hayward & Laursen, 2018 ).

None of the four articles reviewed used General Change Model to support the selection of indicators of change. This may result from the fact that the theory, as described by Paulsen and Feldman ( 1995 ) lacks clear guidance on what indicators are important to measure.

The general change model has very loosely been used to inform change interventions. One project aimed to improve upon typical teaching professional development by continuing to work with faculty through the refreezing stage (Sirum & Madigan, 2010 ). Though Paulsen and Feldman’s ( 1995 ) version of the model provided this focus for their intervention, the project relied on another change theory (Communities of Practice) to design their intervention. Another project aimed to create a more positive climate for female faculty. Latimer et al. ( 2014 ) drew on Lewin’s idea that behaviors in groups are frozen in place due to informal and formal factors and that moving away from the status quo required unfreezing. Thus, they envisioned their challenge as challenging the status quo, but did not draw on the theory further.

Systems Theory (3 articles)

Systems thinking has been written about fairly extensively in the organizational change work. We found the work of Senge ( 2006 ) to be widely used in articles outside of STEM, but such articles were excluded from this analysis. One article in the synthesis used Senge’s work (Quan et al., 2019 ). There were also articles that used alternative conceptions of Systems Theory (Meadows, 2008 ; Wasserman, 2010 ). Senge’s theory of systems thinking focuses on the idea of creating a learning organization (Senge, 2006 ). A learning organization focuses on the ongoing learning of its members to support continuous improvement and transformation. A learning organization has five characteristics, also called five disciplines: (1) systems thinking, (2) personal mastery, (3) mental models, (4) building shared vision, and (5) team learning.

Of these five disciplines, systems thinking is presented as the most powerful “fifth discipline” that brings all of the other disciplines together. A key idea in systems thinking is that structure influences behavior. Despite prevailing ideas in society about individual autonomy and control, typically, different individuals in a similar situation tend to be influenced and behave similarly, given the strong shaping power of a system. The structures in human systems are often subtle and include norms, rules, policies, and procedures—invisible structures that govern how people interact. Although individuals often describe outcomes by looking at events (reactive) or patterns of behavior (responsive), a focus on systems focuses on causation at the level of the system, to allow for prediction and greater flexibility in response to a challenge.

Meadows’ ( 2008 ) work on systems considers the role of the parts and the whole of the system, and how feedback loops can have an impact on how a system functions. When thinking about effective systems, she highlights three characteristics: resilience, self-organization, and hierarchy. Meadows also highlights “leverage points,” or particular parts of the system, where a change might have the largest impact on the system as a whole. Similarly, Wasserman ( 2010 ) highlights the interacting parts of a system, relationships between them, and the importance of multiple perspectives.

Research from a systems thinking perspective attended to both the idea of a system as a whole and the interconnection between parts of the system. Thus, an underlying assumption was that to understand change, one needs to understand both the parts and the whole (Quan et al., 2019 ) Drawing from the work of Meadows, another project built on the idea of particular leverage points within the system as tools for change, to support the implementation of a Green Chemistry curriculum (Hutchison, 2019 ). A final project focused on the role of STEM Education Centers as a larger system of improving undergraduate STEM education on a campus (Carlisle & Weaver, 2018 ).

Systems thinking was useful for making sense of the context of change, because it focused on the system as a whole, its interlocking parts, and connections to other systems. For example, researchers used the notion of systems thinking to understand how departmental change is embedded within the university in a larger social context (Hutchison, 2019 ; Quan et al., 2019 ), or how a STEM center is embedded on a campus (Carlisle & Weaver, 2018 ).

Only one article of three used Systems Theory to inform measurement. Systems Theory drove the pursuit of multiple perspectives and interviewing a variety of stakeholders on a campus to study STEM Education Centers (Carlisle & Weaver, 2018 ).

Articles did not often use Systems Theory to support the design of an intervention, perhaps due to the general lack of empirical work using this theory. Nonetheless, there was one article that used Meadow’s ( 2008 ) concept of leverage points within a system to help target their curricular change efforts (cf. Hutchison, 2019 ).

Other change theories

We found 21 other theories used in only one or two papers. These range from models focused on the individual’s thinking, such as Weick’s sensemaking model, to models of organizational change, such as the 4I model. Some of these change theories are highly prescriptive and have been used to plan interventions, including Kotter’s 8 stages of change. Others have been drawn on only very generally as a concept relevant to change in STEM higher education, such as double-loop learning and intersectionality.

Homegrown change theories

There were also 11 instances where researchers created their own theories. Generally, these “homegrown” theories did not arise from a lack of awareness of existing theories. Instead, researchers drew on diverse existing theories to develop a synthetic and novel framing for their work. Rather than attempting to summarize each of these theories, we provide an example of how such theories were constructed. Consider the Science Education Initiative, which constructed its own model for department-level change (Chasteen et al., 2015 ). The model is organized around discipline-based educational consultants, Science Teaching Fellows, typically postdoctoral researchers who receive support from a Science Education Initiative central hub. The Science Teaching Fellows support faculty to utilize active learning, construct learning goals, and transform their courses using backwards design. These particular actions are then conceptualized as a larger change effort focused on student learning, department culture, and institutional norms. Thus, the Science Education Initiative model constitutes its own approach to change, but also posits theoretical relationships about how change happens, for instance, with its focus on conceptual assessments as a driver for change.

Emergent themes and implications

This article systematically analyzed the use of change theory in STEM higher educational change initiatives and research. In addition to the summaries of individual theories and how they are used above, here, we provide an overarching discussion of emergent themes and implications.

Theme 1: research focuses on individual change

The majority of articles reviewed focused on change at the level of individual instructors and their teaching practices. The two most common theories—Communities of Practice and Diffusion of Innovations—were leveraged to think about how individuals could change. While communities of practice could be used as a theory to think about how a community changes, it was rarely taken up this way by researchers. Thus we conclude that, to date, STEM educational change researchers have thought about improving STEM education primarily as an issue of supporting individual instructors. However, as many of the other theories in our synthesis highlight, the goal of improving postsecondary STEM education requires careful attention to many interlocking systems and parts of systems. We found more articles in our original searches that used systems thinking, but many were excluded from this synthesis because they were not STEM-specific.

Theories that view instruction as a part of a larger system tended to be used infrequently. Given that some researchers were able to use these theories productively, we believe this approach could be productive for improving STEM education. For instance, the Four Frames defines components of a culture, helping change agents and researchers consider what in a department or university culture needs attended to and measured (Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018 ). Similarly, systems thinking emphasizes that organizational structures influence behavior, including norms, policies, and practices (Senge, 2006 ). A project grounded in systems thinking as a change theory would attend to the interlocking parts of the university system.

There are also a few change theories that have been rarely used in work on STEM higher education, and that have potential to help move our efforts beyond individual change. We briefly highlight two here: CHAT and the 4I framework of organizational learning. Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), born in the discipline of psychology, provides a variety of tools for thinking about change by linking what people think and feel to what they do (Cole, 1996 ; Engeström, 2001 ). CHAT has its roots in social learning theory, which focuses on the mediating role of artifacts in thinking (Vygotsky, 1978 ). Building on this idea, CHAT introduces the concept of an “activity system,” which is often represented as an Activity Triangle. Six components, each with cultural and historical dimensions, contribute to the desired outcome (Foot, 2014 ). All of the interacting parts of an activity system must be considered in the pursuit of change, and individual components of the system are considered important, but secondary, units of focus. CHAT recognizes that there are multiple perspectives within a single system, which can be a source of both trouble and innovation. It also considers how activity systems develop over time, and how any system must be understood with respect to its history. Contradictions, or historically accumulated structural tensions, are often a source of change. CHAT is an extensive theory with untapped potential for work in STEM higher education. For example, CHAT provided a useful theory for understanding how a Departmental Action Team (DAT) aims to achieve sustainable changes in a given department (Reinholz et al., 2017 ).

Another discipline that has built theory relevant to change in STEM higher education is business management. Specifically, the concept of organizational learning broadly refers to how organizations create, retain, and transfer knowledge within the organization. The 4I framework of organizational learning distinguishes among levels of an organization that can learn (individuals, groups, and the organization as a whole) and four processes that occur to contribute to learning (Crossan et al., 1999 ). The 4I’s refer to these processes: intuiting, interpreting, integrating, and institutionalizing. Individuals can intuit (recognize patterns and possibilities based on their own experiences) and interpret (explain ideas to one’s self and others). Groups can interpret and integrate (developing shared understanding and taking coordinated actions). Organizations can institutionalize (create organizational mechanisms to ensure certain actions occur). The 4I model also recognizes a tension between new learning “feeding forward” from individuals to organizations and leveraging what has already been learned at the organizational level in the work of groups and individuals (feedback). Hill et al. ( 2019 ) capitalized on the 4I framework of organizational learning to frame investigations of a multi-institutional STEM reform network, providing an example of how to examine change beyond individuals.

Of course, there are likely other useful theories that are beyond the scope of this review. In general, theory that attends to larger systemic and structural issues can help sustain change in STEM higher education. Ultimately, a research team need not worry about choosing a single “best” theory for a project. Such a theory most likely does not exist. Rather, it is important for researchers to be thoughtful about the theories they choose and how different theories provide different insights. For example, some of the scholarships we reviewed on Diffusion of Innovations might have reached different outcomes if it had simultaneously used a more systemic perspective, such as the CHAT theory or the 4I framework. Ultimately, we imagine that a given project could benefit most from multiple theories tailored together to meet its goals.

Theme 2: research often draws upon theory in a superficial fashion

We found that the ways in which particular research projects drew upon theory varied dramatically. Consider Communities of Practice as a change theory. On one end of the spectrum, research projects utilized the idea of a Community of Practice to support a particular intervention (typically a faculty learning community) as a mechanism for change. These projects were largely atheoretical with their use of Communities of Practice, even though there is a relatively rich conceptualization of how a faculty learning community can function as a community of practice (Cox, 2001 ). In contrast, others drew on specific aspects of the theory that posit how change would happen (Gehrke & Kezar, 2019 ).

We propose that research on change in STEM higher education has reached a point of maturity where substantially drawing on existing theory is part of making a valuable scholarly contribution to the field. This includes explicitly framing change efforts, studies, and papers with one or more theoretical frameworks relevant to change. Drawing on change theory involves more than briefly summarizing a theory in the introduction of a paper. Using a theory to frame scholarly work involves using the theory as a lens or guide that directly informs specific components of the work, including interventions, focus, research questions, measurement and evaluation, data analysis, and data interpretation. Readers benefit when researchers explicitly describe how the theory informed their work and whether their findings confirm the utility of the theory in their context or suggest modifications to the theory for a specific context. In this way, the trustworthiness and utility of a theory is improved over time.