- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Statistical analysis of white-collar crime.

- Gerald Cliff Gerald Cliff National White Collar Crime Center

- and April Wall-Parker April Wall-Parker National White Collar Crime Center

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.267

- Published online: 26 April 2017

As far back as the 19th century, statistics on reported crime have been relied upon as a means to understand and explain the nature and prevalence of crime (Friedrichs, 2007). Measurements of crime help us understand how much of it occurs on a yearly basis, where it occurs, and the costs to our society as a whole. Studying crime statistics also helps us understand the effectiveness of efforts to control it by tracking arrests and convictions. Analysts can tell whether it is increasing or decreasing relative to other possible mitigating factors such as the economy or unemployment rates in a community. Politicians can point to crime statistics to define a problem or indicate a success. Sociologists can study the ups and downs of crime rates and any number of other variables in the society such as education, employment rates, ethnic demographics, and a long list of other factors thought to affect the rate at which crime is committed. Property value is affected by the crime rates in a given neighborhood, and insurance rates are said to fluctuate with the ups and downs of crime.

Analyzing any criminal act’s prevalence, cost to society, impact on victims, potential preventive measures, correction strategies, and even the characteristics of perpetrators and victims has provided valuable insights and a wealth of useful information in society’s efforts to combat violent/index crimes. This information has only been possible because there is little disagreement as to exactly what constitutes a criminal act when discussing violent or property crimes or what has come to be grouped under the catch-all heading of “street crime”; this is decidedly not the case with crimes included under the white-collar crime umbrella.

- white-collar crime

- corporate crime

- crime measurement

- victimization

- computer crime

White-Collar Crime: The Historical Definitional Debate

The challenge of analyzing the phenomenon of white-collar crime lies in the fact that the term “white-collar crime” can mean different things to different disciplines or even different things to different camps within those disciplines. Academics often disagree with the legal profession, who may disagree with law enforcement, who in turn, may disagree with legislators and politicians as to exactly what constitutes white-collar crime. Generally, the varying definitions tend to concentrate on either or both of the following factors: characteristics of the offender, such as social status, or positions of trust within the community and characteristics of the crime itself.

Arguments among stakeholders aside, there is no such thing as the “right” white-collar crime definition—only the definition that is right for the purposes of the entity employing it. It is, however, vital to understand what the term means to the persons using it in order to understand what they are actually saying. This consideration can be especially important when dealing with abstracted statistics. The statement “white-collar crime is increasing” is meaningless without understanding what white-collar crime means to the author. The definition impacts what questions are asked, what kinds of answers are meaningful, and where researchers look for the answers to those questions. As other researchers in the field have noted, “[h]ow we define the term white collar crime influences how we perceive it as a subject matter and thus how we research” (Johnson & Leo, 1993 ). Depending on how one goes about deciding what to study in attempting to understand white-collar crime, one can either conclude that it is a form of conduct peculiar to offenders of high status enjoying positions of trust, as Sutherland seemed to feel, or one may arrive at a different conclusion if the research is confined to those convicted of federal offenses traditionally thought of as white-collar crime. In studying convictions, court records, presentence reports, and so on, of those accused of what would ordinarily be thought of as white-collar offenses, some researchers have used the relative lack of education and lower social/economic status and occupation to claim that white-collar crime is more attributable to the middle class (Weisburd, Waring, & Chayet, 1995 ). This claim tends to “trivialize” white-collar offenses and overlooks offenders who, by virtue of their social status, education, and positions of trust within their chosen professions and their communities are able to influence how their actions are defined, investigated, prosecuted, and in some cases, even the degree to which an act is defined as criminal (Pontell, 2016 ). For example, Calavita, Pontell, and Tillman ( 1997 ) examined the savings and loan crisis that resulted in colossal financial losses that are certainly attributable to “non–middle-class offenders.”

Sociologist Edwin Sutherland is credited with having first coined the term “white-collar crime” in 1939 in a speech given at the American Sociological Society (Sutherland, 1940 ). His comments in the original speech did not formally define the term, but he would eventually come to define white-collar crimes as “crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation” (Sutherland, 1949 ). The offender-based definition seemed to serve sociologists well as a way to label and talk about offenses committed by successful, healthy people who were not suffering from the deficits of poor surroundings, lack of education, and all the other attributes that had come to be associated with perpetrators of violent (street) crime. It helped explain why well-educated people who had ample access to societal resources (members of respectable society) could resort to crime as a means of achieving the goals they should logically have been able to achieve without violating the law. Sutherland’s contribution expanded the discussion to include illegal deviance perpetrated by those who had already achieved traditional success through socially acceptable methods.

Notably, Sutherland’s definition explicitly rejected the notion that a criminal conviction was required in order to qualify (Sutherland, 1940 ). Sutherland ( 1940 ) saw four main factors at play here: (1) civil agencies often handle corporate malfeasance that could have been charged as fraud in a criminal court; (2) private citizens are often more interested in receiving civil damages than seeing criminal punishments imposed; (3) white-collar criminals are disproportionately able to escape prosecution “because of the class bias of the courts and the power of their class to influence the implementation and administration of the law”; and (4) white-collar prosecutions typically stop at one guilty party and ignore the many accessories to the crime (such as when a judge is convicted of accepting bribes and the parties paying the bribes are not prosecuted).

A related concept that again focuses on the offender is “organizational crime”—the idea that white-collar crime can consist of “illegal acts of omission or commission of an individual or a group of individuals in a legitimate formal organization in accordance with the operative goals of the organization, which have a serious physical or economic impact on employees, consumers or the general public” (Schrager & Short, 1978 ).

Although these definitions were vital for expanding the realm of sociology and criminology, they weren’t as well suited to the needs of other criminal justice stakeholders who deal with these issues in a more practical sense (including policymakers, law enforcement, and the legal community). These definitions work well when discussing why white-collar crime occurs or who commits it, but they are not as well suited to asking questions about how much white-collar crime is occurring or whether prevention methods are working.

A model of white-collar crime that lends itself somewhat more to empirical data analysis was Herbert Edelhertz’s 1970 definition: “ An illegal act or series of illegal acts committed by nonphysical means and by concealment or guile to obtain money or property, to avoid the payment or loss of money or property, or to obtain business or personal advantage .” As a crime-based definition, it ignored offender characteristics and concentrated instead on how the crime was carried out. As a result, it covered a far larger swath of criminality—including crimes (or other illegal acts—Edelhertz’s definition also reaches to acts that are prohibited by civil, administrative, or regulatory law, whether or not the perpetrators are ever called to answer for them) perpetrated outside of a business context, or by persons of relatively low social status.

Edelhertz ( 1970 ) identified four main types of white-collar offending:

personal crimes (“[c]rimes by persons operating on an individual, ad hoc basis, for personal gain in a non-business context”),

abuses of trust (“[c]rimes in the course of their occupations by those operating inside businesses, Government, or other establishments, or in a professional capacity, in violation of their duty of loyalty and fidelity to employer or client”),

business crimes (“[c]rimes incidental to and in furtherance of business operations, but not the central purpose of such business operations”), and

con games (“[w]hite-collar crime as a business, or as the central activity of the business”).

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (U.S. Department of Justice, 1989 ) when specifically addressing white-collar crimes (the FBI [U.S. Department of Justice, 2011 ] usually references “financial crimes” instead), uses a very similar definition: “ those illegal acts which are characterized by deceit, concealment, or violation of trust and which are not dependent upon the application or threat of physical force or violence. Individuals and organizations commit these acts to obtain money, property, or services; to avoid the payment or loss of money or services; or to secure personal or business advantage .” This definition has been operationalized by the FBI’s Criminal Justice Services Division to mean the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) offenses of fraud, forgery/counterfeiting, and embezzlement, and a rather longer list of National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) offenses (Barnett, 2000 ). Thus, while this definition and Edelhertz’s are very similar, the FBI’s definition functionally excludes noncriminal illegal activity, as well as such incidents that are not reported to police and don’t fit into a relevant UCR or NIBRS category (for those jurisdictions that participate in NIBRS). At the same time, the FBI’s definition dovetails well with already-collected data, making it a practical tool for generating statistics on white-collar crime activity.

As a practical matter, many people have rather informal interpretations of the term. White-collar crime can informally mean:

Financial crimes

Nonphysical (or abstract) crimes

That is, crimes that “occur” on a form, balance book, or computer

Crime by or targeting corporations

Crimes typically committed by the rich

Criminal businesses or organizations

Including, for some, organized crime and terroristic organizations

Corporate or professional malfeasance

For some, this crime can include acts that are immoral but that are not specifically prohibited by law

Anything that’s against the law that the average beat cop won’t handle

Essentially, everything but street crime

Many people have a general sense that they know what counts as white-collar crime and what does not, but they have no specifically articulated sense of what qualities separate the class of white-collar offenses from non–white-collar offenses.

Having so many definitions in use means that it’s often difficult to compare data gathered by different white-collar crime stakeholders and that theoretical constructs in use by one group may be completely misaligned to the needs of another. One way that various groups have tried to reduce these inefficiencies is by crafting definitions that could enjoy buy-in from larger groups of stakeholders, providing them a common language (and compatible tools) for discussing white-collar crime.

In 1996 , the National White Collar Crime Center convened a group of noted academics specifically to address this definitional dilemma (NW3C, 1996 ). 1 Participants were selected from among the most noted scholars in the criminal justice field, who had devoted significant effort to the study of white-collar crime. Several aspects of white-collar crime were examined and discussed at length. Each attendee was asked to produce a paper on his or her position on how the term should be defined, laying out their arguments in support of their preferred definition. From the presentation of these position papers, extensive discussions among the assembled academics were held. Through this process, white-collar crime was examined from a variety of perspectives.

After considerable discussion and debate, those present at the workshop reached some consensus on the elements that need to be present to satisfy the concept of white-collar crime. Most agreed that the lack of direct violence against the victim was a critical element. They agreed that the criminal activity should have been the result of an opportunity to commit the crime afforded by the offender’s status in an organization or their position of respect within the community. Deception to the extent necessary to commit the criminal offense such as misrepresentation of the perpetrators abilities, financial resources, accomplishments, some false promise or claim intended to deceive the victim, or possibly a deliberate effort to conceal information from the victim—all should be considered as elements of white-collar crime. Some even contended that the term should be abandoned altogether and replaced by something more along the lines of economic crime, elite crime, or simply financial crime (Gordon, 1996 ).

In the end, those in attendance ultimately agreed that an acceptable definition would be: “ illegal or unethical acts that violate fiduciary responsibility of public trust, committed by an individual or organization, usually during the course of legitimate occupational activity, by persons of high or respectable social status for personal or organizational gain .”

This statement may address the definitional dilemma to some degree, but to further emphasize the difficulty of arriving at a universally acceptable definition, it still does not address some aspects of white-collar crime. Financial crimes committed with a computer, using the Internet, normally do not involve physical threat or violence, they almost always involve deception in some manner, and they can result in devastating damage to the victim(s), yet they have absolutely nothing to do with the social status of the perpetrator, do not require that the perpetrator occupy a position of trust within an organization or community, and may not even require a significant level of education. Perhaps the best way to conceptualize white-collar offenders is on a continuum that considers all aspects of the crime itself, the perpetrator, the relationship to the victim, and the position the perpetrator occupied that made it possible to commit the offense.

As this article does not intend to advocate for any particular interpretation of the term, we will be using the term “white-collar crime” in the widest possible sense, so as not to exclude any of the various camps from the discussion (though many will doubtless find some aspect of the article that treats the term in a broader sense than their personally held definitions would allow).

Why White-Collar Crime Matters

Violent crime is both alarming and costly. However, despite its physical and psychological impact on victims and even witnesses, street crime pales in many ways when compared with white-collar crime. A victim of a robbery is often traumatized by the experience and suffers the loss of any valuables taken by the perpetrator. They also suffer psychologically by being put in fear of injury or death, but, assuming the victim was not injured, valuables can be recovered by the police and may be covered by insurance and, as such, may not actually be a loss at all. An armed robber can certainly empty a cash drawer, take a wallet and jewelry, even steal a victim’s car, but the loss of these items is insignificant when compared to the loss of the total contents of a person’s bank account, life savings, credit rating, home, investments, and overall peace of mind. A number of anecdotal cases and studies have pointed to the unique stressors that a victim experiences after suffering loss from fraud. For example, there is evidence that financial loss due to fraud is a direct causal factor in many cases of depression and suicides (Saxby & Anil, 2012 ).

Addressing the issue of white-collar crime is extremely important because of its serious impact on victims, society, and the economy. Additionally, white-collar crimes are unique in that in many instances there is an inherent ability to victimize large numbers of individuals, often with a single act (i.e., identity theft). Estimates of monetary loss to employees and stockholders and, ultimately, society in general due to white-collar and corporate crime have reached hundreds of billions of dollars (Public Citizen, 2002 ). A 1976 estimate of the total cost of white-collar crime puts the figure in the neighborhood of $250 billion per year (Rossoff, Pontell, & Tillman, 1998 ), while a more recent study estimates financial losses from white-collar crimes to be between $300 and $600 billion per year (Stewart, 2015 ).

It is estimated that approximately 36% of businesses (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016 ) and approximately 25% of households (NW3C, 2010 ) have been victims of white-collar crimes in recent years, compared to an 8% and 1.1% prevalence rate of traditional property and violent crime, respectively (Truman & Langton, 2015 ). In addition, an examination of some of the most prevalent areas in which white-collar crime seems to be found will amply illustrate the gravity of the problem.

One area of white-collar crime that consistently remains in the spotlight is health care and insurance fraud. The rising costs of medical care have driven the cost of health care insurance increasingly higher. Recent estimates put total health care spending in the United States at a massive $2.7 trillion, or 17% of GDP. No one knows for sure how much of that sun is embezzled, but in 2012 Donald Berwick, a former head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and Andrew Hackbarth of the RAND Corporation estimated that fraud (and the extra rules and inspections required to fight it) added as much as $98 billion, or roughly 10%, to annual Medicare and Medicaid spending—and up to $272 billion across the entire health system ( The Economist , 2014 ).

Identity theft is another type of fraud that is frequently highlighted in discussions of modern white-collar crime. This fraud can range from simply using one’s credit card under false pretenses to opening entire bank accounts or mortgages using someone else’s personally identifiable information (PII). Through use of the Internet, this particular type of fraud often strikes multiple victims at once via corporate data breaches. The 2015 Identity Fraud Study, released by Javelin Strategy & Research, found that $16 billion was stolen from 12.7 million U.S. consumers in 2014 , compared with $18 billion and 13.1 million victims a year earlier. Further, there was a new identity fraud victim every two seconds in 2014 (Javelin, 2015 ). Aside from the considerable losses caused by identity theft and other characteristics that it may share with white-collar crimes (such as the lack of face-to-face contact between the victim and perpetrator and the fact that they are financial crimes and are complex to investigate), there are those who make a compelling case that identity theft should not be characterized as white-collar crime. Certainly, there is no requirement that a perpetrator enjoy some employment-related position of trust or require above average levels of education. “Many financial cases of identity fraud are the work of con artists and organized crime rings, in which offenders possess no legitimate occupational status, which is generally a major prerequisite for inclusion into the ranks of white collar criminals” (Pontell, 2009 ).

A wide variety of fraudulent practices that could be categorized as white-collar crime (including identity theft, advance fee frauds, online and telemarketing scam complaints) are tracked by the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel Network. In 2015 , the network collected a total of 3,083,379 consumer complaints (Federal Trade Commission, 2016 ). This is an increase of nearly 850% since the network began reporting in 2001 (Federal Trade Commission, 2016 ), with an annual percentage growth rate of 56%. Such growth far exceeds that of more traditional crime types, which have actually been declining in recent years.

In addition to the so-called more traditional forms of white-collar crime, a long and growing list of other white-collar crimes have come into prominence in recent years—especially intellectual property crime, mortgage fraud, and financial abuse of elders.

When intellectual property (IP) crimes are mentioned, many probably think of the controversies involving the downloading of copyrighted songs and movies. But IP theft is more than that. “Intellectual property crimes encompass the full range of goods commercially traded worldwide” (Dryden, 2007 ) and involve far more serious and potentially damaging practices than are usually considered. These practices can include everything from car parts (including nonfunctioning and substandard airbags and brake parts) to tainted pet food and baby formula. For example, Operation Opson V, conducted between November 2015 and February 2016 , seized more than 10,000 tons and one million liters of hazardous fake food and drink in operations across 57 countries (Interpol, 2016 ). These products are produced and sold in underground economies or in markets where they go unregulated and escape normal tax and tariff payments. They are not subject to the most basic requirements of regulatory oversight intended to assure the safety, integrity, and purity of the product. They expose consumers to health and safety risks and impose costs on society in a multitude of ways. Counterfeit products that are of particular concern are pharmaceuticals. Recent studies suggest that only 38% of prescription drugs purchased online are genuine (European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicines, 2008 ). The International Chamber of Commerce estimated that the total global economic value of counterfeit and pirated products is as much as $650 billion every year (International Chamber of Commerce, n.d. ).

Mortgage fraud is also a continuing problem, with the most recent information available indicating that “residential mortgage loan applications with fraudulent information totaled $19.8 billion in mortgage debt for the twelve months ending the second quarter of 2014 ” (Corelogic, 2014 ). As large as these numbers are, they represent only a small percentage of the actual losses incurred, owing largely to the complexity of investigating and prosecuting these types of offenses. Executives in large corporations who engage in high-level white-collar crime enjoy a degree of insulation from exposure to the criminal justice system. This insulation derives from the complexity of investigating and prosecuting their crimes; their ability to mount expensive and challenging defenses; their own position and that of their corporations in society; and the criminal justice system’s tendency to allow the accused to negotiate a settlement without admitting guilt. For example, a recent Securities and Exchange Commission press release revealed that “that a California-based mortgage company and six senior executives agreed to pay $12.7 million to settle charges that they orchestrated a scheme to defraud investors in the sale of residential mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae). In settling the charges without admitting or denying the allegations, each of the six executives agreed to be barred from serving as an officer or director of a public company for five years” (SEC press release, 2016 ). This type of settlement is not captured in the statistics as a conviction and, although the actions of the perpetrators would certainly fulfill the definition of white-collar crime, because there was no admission of guilt and no conviction (since no trial ever took place), the entire incident would never appear in any official statistical count of white-collar crime.

This is not necessarily uncommon with offenses that can be labeled as white-collar crime and points to a larger issue involved in “measuring”: many of these crimes may not appear in the ledgers of adjudication. Unfortunately for studies of statistical trends in white-collar crime, we are often left with partial views of the true scope of this crime, painted purely through adjudication measurements. Many tend to think of white-collar crime as targeting wealthy companies and individuals or the government. This belief may allow many to rationalize this type of crime, leading to the belief that the victim impact is minimal due to already inflated financial statuses. When we take a closer look at some key examples of white-collar crime, however, we see that this area of criminal activity merits considerable concern.

One of the most high-profile cases in recent history, the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme, is a good illustration of how one person committing white-collar crime can victimize hundreds, even thousands, of victims. News of Madoff’s crimes hit the news cycle in 2008 . Madoff’s investors provided him with approximately $20 billion to invest; Madoff made it appear as though his investors, as a group, had earned nearly $65 billion in returns (on which they ultimately paid taxes), which was simply not the case. Discussing the recovery of a sizable portion (approximately $11 billion) of the monies lost to the victims, one author observed: “It’s as though they’d put all that money under the mattress for decades, and now they can spend a little more than half of it. Making matters worse, they all paid federal capital gains taxes on that $45 billion in investment income that never existed” (Assad, 2015 ). Based on Madoff’s accounts with 4,800 clients (as of November 30, 2008 ), prosecutors estimated his fraud to have totaled $64.8 billion. Legal efforts to recover some of the monies lost through this scam have been underway since the case first broke. Ultimately, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison and ordered to pay $170 billion in restitution. His victims were left with trying to rebuild their lives, a prospect that some could not face ( The Telegraph , 2009 ).

The Madoff case is just one example of how white-collar crime can touch many lives. There are a number of “more mundane” forms of white-collar crime that alter peoples’ lives on a daily basis. Consumer crime is an all-encompassing term that covers a number of white-collar crimes affecting the populace, including but not limited to, false advertising, commercial misrepresentations, price manipulation, and a host of related criminal and/or unethical behaviors. Few statistics exist that address this group of crimes as a whole, as the underlying actions are often handled through a host of distinctly different channels and much of the information exists purely in anecdotal form. That said, existing data (though incomplete) suggest that enforcement of these matters is on the rise. Take, for example, the number of federal actions each year under the False Claims Act, which more than doubled from 1987 to 2015 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2015 ), or the number of complaints to FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network, which increased more than eightfold from 2001 to 2015 (Federal Trade Commission, 2016 ). Whether this increase can be attributed to an increase in the underlying activities, greater likelihood to report victimization, or greater law enforcement interest or ability to combat the activities is difficult to determine.

Another rising problem that can affect all facets of society is elder financial abuse. White-collar criminals take advantage of one of the most vulnerable sectors of our society, individuals who are at their most defenseless time of life, stealing from them at a time when they can least afford to be victimized. The True Link Report on Elder Financial Abuse 2015 ( 2015 ) reveals that seniors lose $36.48 billion each year to elder financial abuse—more than 12 times what was previously reported. Moreover, the highest proportion of these losses—to the tune of $16.99 billion a year—comes from deceptive but technically legal tactics designed to specifically take advantage of older Americans. The reported incidence of this particular form of white-collar crime is likely just a shadow of the real problem, as the number of unreported cases of this crime can never truly be estimated. Elder financial abuse cases often go unreported for any number of reasons. The victim is unwilling to report crimes being committed by their family members (a frequent source of elder abuse fraud); the victim may not know who to report the crimes to; or they may not even be aware that they are being victimized in the first place. As the average age of our society increases over time, these crimes will likely also increase and keep pace with the growing number of elderly potential victims in society.

The Internet and emerging technologies have helped accelerate the growth of many white-collar crimes, providing not only a new vehicle for perpetrating crimes but also entirely new categories of criminal activity that would not be possible without emerging technologies. Computer crimes (those crimes committed using a computer as the instrument of the crime ) involve the use of technology to facilitate or initiate consumer fraud and is now so commonplace that 50% of all consumer frauds reported to the FTC in 2012 were Web- or e-mail based. In order to attempt to track and categorize crimes related to the Internet, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (formally known as the Internet Fraud Complaint Center, or IC3), was formed in 2001 . This joint effort between the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C) and the FBI was established to track crimes committed over the Internet and refer those crimes to law enforcement. In its first year of operation, IC3 received 49,711 crime complaints. Since that time, the number of complaints received by IC3 has steadily increased at an annual growth rate of 12.4%. In 2014 , the IC3 received 288,012 complaints, with losses of over $1 billion reported (Internet Crime Complaint Center, 2016 ).

The message here is that while all of us have a healthy fear of violent/street crime, white-collar crimes can be, and often are, far more damaging in terms of costs to the society and the rate at which the crimes are multiplying. One of the most difficult challenges is measuring just how much white-collar crime exists. This task is made infinitely more difficult by the fact that there is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes white-collar crime. This lack of consensus is understandable considering the many different types of crime that can fall under the umbrella of white-collar crime. Yet, without the ability to clearly define an act as a white-collar crime, it is impossible to determine with any accuracy just how much white-collar crime is taking place, what treatments intended to mitigate its prevalence are having an effect, or what level of punishment is likely to act as a deterrent.

Statistical Evidence of White-Collar Crime

Unlike the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) for index crimes, there is no universal dataset of white collar crime statistics. When looking for hard statistical evidence of the prevalence of white-collar crime, researchers are left with a patchwork of federal data sources (i.e., Uniform Crime Report, Judicial Business of the United States Courts, United States Attorneys Annual Statistical Report, Annual Report and Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics, and many more) citing various crime types and a handful of self-report victim surveys. Federally published data (see Table 1 ) indicate that white-collar crimes in their various officially recorded forms are decreasing, much as index crimes have been steadily decreasing over recent years (Cooke, 2015 ). The weakness of using the UCR as a measure of white-collar crime, however, is that there are far more types of white-collar crime than the UCR system tracks.

Table 1 Ten-Year Arrest Trends a

a Note : The information in this table is taken directly from Table 33 of the Uniform Crime Reports. The year range is intended to illustrate the ten-year trends in the three offense categories tracked by UCR that would logically constitute white-collar crime offenses.

Source: United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (September 2012–2015). Crime in the United States, 2011–2014 .

The UCR data, however, are at odds with self-report victim data (such as the IC3 Annual Report and Federal Trade Commission Report) and anecdotal data sources, which indicate that white-collar crimes are on the rise. Therefore, the following questions arise: is this increase due to more awareness of the problem or to actual increases in crime rates? Do the data reflect a reluctance to charge and prosecute white-collar crime, or are white-collar crimes decreasing? With no longitudinal data and without a consistent way to count arrests and prosecutions associated with white-collar crime, it is nearly impossible to determine what is affecting the incidence of white-collar crime. That said, the comparison of statistical arrest data versus self-report data is not the most desired comparison; but the sheer lack of available white-collar crime datasets leaves us little choice as far as worthwhile comparisons go. This problem is further complicated by the fact that many white-collar crime victims may not even know that they have been victimized (Friedrichs, 2007 ) or do not report their victimization to the proper authorities (e.g., a victim of credit card fraud reporting to the credit card company but not to local police) (NW3C, 2006 ), which can further frustrate statistical counts.

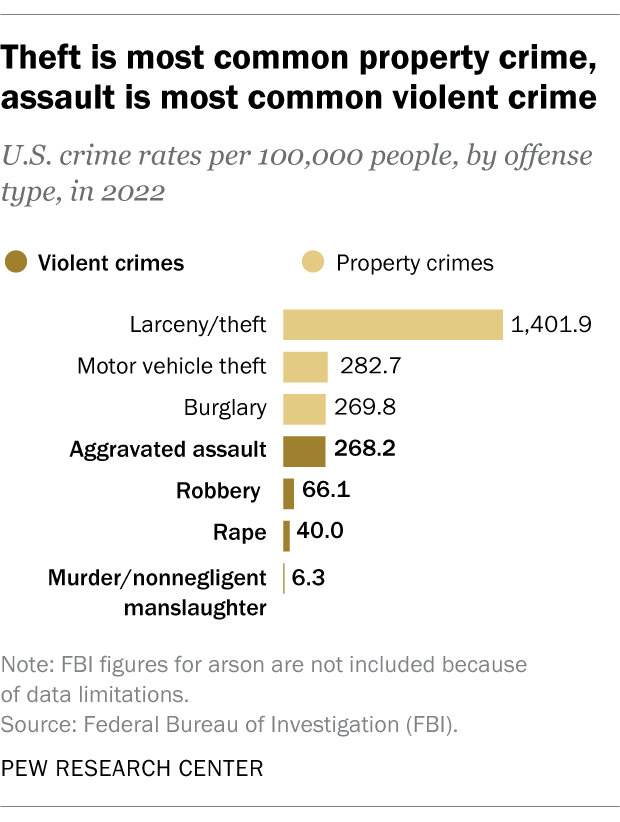

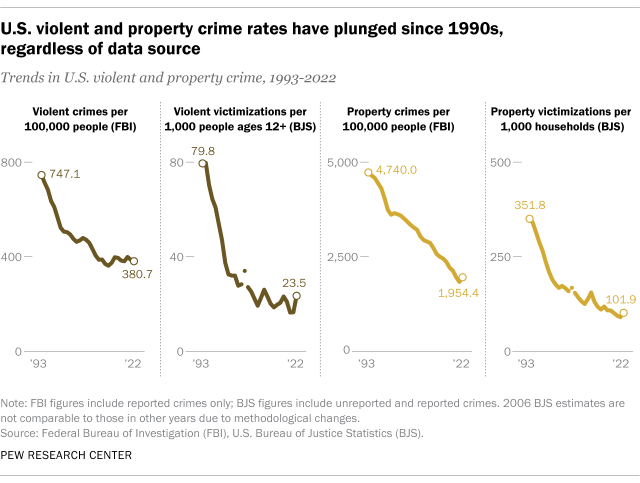

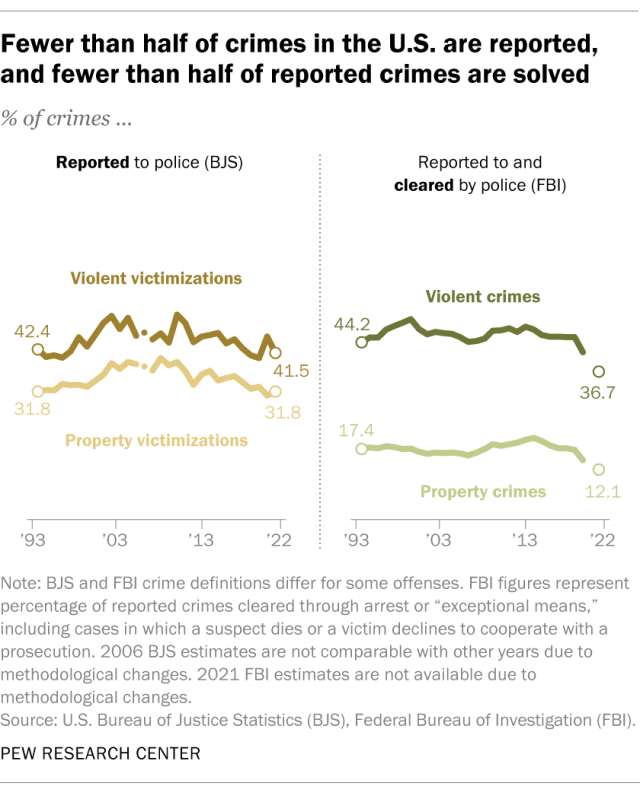

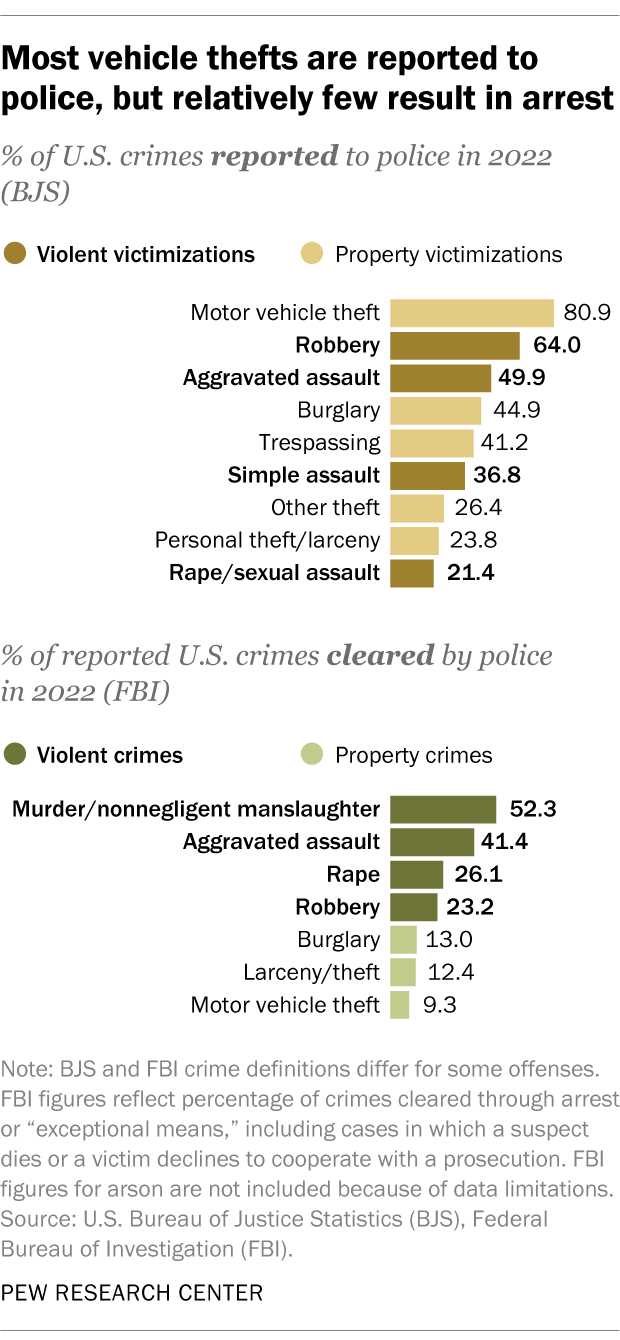

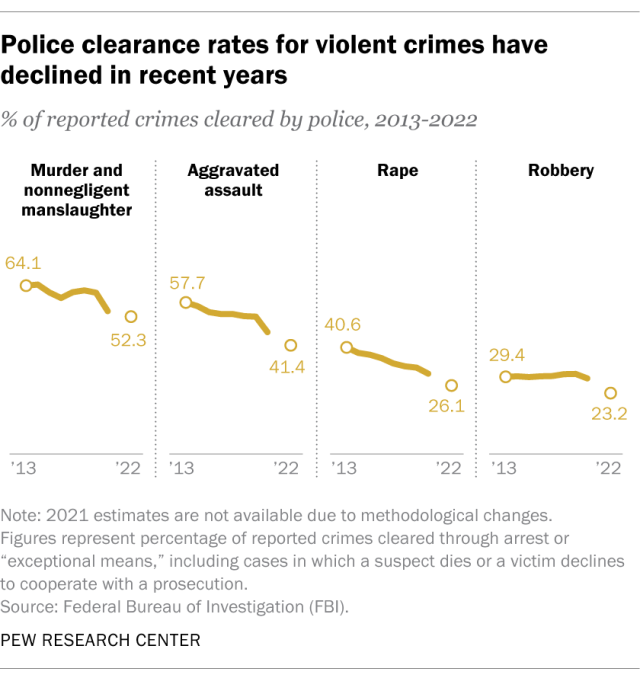

It is generally accepted, however, that modern instances of white-collar crime touch the public much more than traditional crimes. Reputable data show that traditional street crimes have been decreasing in frequency across the board for some time. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ victimization studies show that, from 2005 to 2014 , reported victimization by violent crime decreased by 22.8%, and reported victimization by property crimes decreased by 18.1%; the rate of violent crime declined slightly from 23.2 victimizations per 1,000 persons in 2013 to 20.1 per 1,000 in 2014 (Truman & Langton, 2015 ). The violent crime rate did not change significantly in 2014 compared to 2013 ; violent crimes include rape or sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault. In comparison, the property crime rate, which includes burglary, theft, and motor vehicle theft, fell from 131.4 victimizations per 1,000 households in 2013 to 118.1 per 1,000 in 2014 (Truman & Langton, 2015 ). The overall decline was largely the result of a decline in theft (Truman & Langton, 2015 ). The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports (which rely on police reports instead of victim data) show that when considering 5- and 10-year trends, the 2014 estimated violent crime total was 6.9% below the 2010 level and 16.2% below the 2005 level (U.S. Department of Justice, 2014 , 2015 ).

Comparatively, the most recent comprehensive white-collar crime victimization study (NW3C’s 2010 National Public Survey on White Collar Crime) found that 24.2% of American households in 2010 reported experiencing at least one form of white-collar crime, compared to 12.5% of all households being victimized by property crime in that same year (Truman & Planty, 2012 ). In this case, the term “white-collar crime” was operationalized to mean the following specific activities: credit card fraud, price fraud, repair fraud, Internet fraud, business fraud, securities fraud, and mortgage fraud (excluding identity theft, insurance fraud, embezzlement rates, or regulatory violations, for example).

Meanwhile, there are clear indications that white-collar crime should be on the increase:

The Skills Required to Commit White Collar Crimes are Becoming More Common

Many white-collar crimes require significantly higher levels of education than street crimes, or specialized technical skills. All of these skills are becoming more available in our society as we witness a widespread increase in literacy rates, computer use, and educational attainment (UNESCO, 2016 ; File & Ryan, 2014 ; Ryan & Bauman, 2016 ).

The American Populace Is Aging

Physical crimes favor the young, while fraud is generally associated with older perpetrators. Financial scams targeting seniors have become so prevalent that they’re now considered “the crime of the 21st century ” (National Conference on Aging, 2016 ). The FBI reports that these white-collar crimes, such as Internet sweepstakes schemes, specifically target seniors because of their access to liquid assets and because their deteriorating cognitive ability makes them more susceptible to Internet fraud than the general public) (Cooper & Smith, 2011 ; Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2016 ).

Opportunity to Commit White-Collar Crimes Is Increasing

In traditional, “on-the-job” white-collar crime, there was a time when only a very few individuals had access to the means to commit many crimes. As recently as the 1980s, far fewer American workers had realistic access to corporate information (Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d. ). By 2012 , the number of Americans in the agricultural sector had declined by 55% and those in the industrial sector by 41.6%, while those employed in the service sector, including management, had increased by 16.3%. In other words, 47.6% of the total workforce is now in a position to sell trade secrets, embezzle funds, or commit other traditional white collar crimes (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013 ).

Things of Value are Increasingly Likely to be Intangible

Moving from means and opportunity to motivations, the nation is increasingly embodying its wealth in information or information products (Apte, Karmarkar, & Nath, 2008 ). The value of a pirated CD is found in the information encoded on the disc rather than in the cheap plastic medium itself. When the Business Software Alliance reported that $62.7 billion worth of software had been illegally copied (“pirated”) as of the 2013 report (BSA, 2014 ), they were reporting on the hypothetical value of lost sales of information, not on the loss of the worth of the plastic discs (which the perpetrators likely legitimately purchased in the first place). The concept of wealth itself is increasingly represented in nonphysical units. There was a time when, if thieves did not steal hard currency, they were invariably stealing something other than money. Now, money can be stolen by manipulating digital banking information stored in computer hard drives or even digital currencies that really only exist in concept.

White-Collar Techniques are Very Effective at Obtaining Intangible Things of Value

Things of value embodied in the form of information are particularly susceptible to attacks using information technology (computers). The rise of business computing means that a great deal of sensitive information that might once have been physically secured in locked cabinets or safes is now transmitted by e-mail or stored on company servers or in the cloud. Although it is difficult to quantify the extent to which the use of digital storage and retrieval systems renders the underlying information more vulnerable, it stands to reason that the information is now less secure and, hence, more likely to be exploited.

Computer-Related Crime

Linking computers together through the Internet has led to unprecedented potential for securing money through informational manipulation. The proliferation of technology in today’s society has resulted in a situation where “almost all business crime in the 21st century could be termed computer crime, as all major business transactions are carried out with computers” (Pontell, 2011 ). Compared to “traditional” scam techniques, the Internet provides an incredibly cheap, relatively anonymous means of reaching potential victims. In the offline environment, a scam that only snares one target out of a thousand is unlikely to offer a high enough return on investment to be worth pursuing. On the other hand, the online version of that same scam can be enacted several thousand times at once with the use of a mailing list (or any other means of electronic mass distribution). If the criminal sends the opening gambit of the scam to 20,000 potential victims, he or she may well get 20 useful replies in an afternoon. This is done with very little setup cost, very little time investment, and relative anonymity compared to performing the scam in person. This also allows criminals to realistically pursue distributed victimization strategies, where the dollar loss is spread out across such a wide group of victims that no one case is worth investigating.

Thus, a single white-collar criminal (or group of criminals) can easily be at the center of what seems like a worldwide crime wave. A single fraudster—like Robert Soloway, convicted in 2008 of fraud and criminal spamming—can completely flood the Internet with unsolicited and fraudulent e-mails. In Soloway’s case, it was to the self-admitted tune of trillions of e-mails, which made him thousands of dollars a day (Popkin, 2008 ) for a period spanning 1997 to 2007 (Government Sentencing Memorandum No. CR07-187MJP, U.S. v Soloway ) and for which he received a sentence of 47 months. Similarly, hacker Albert Gonzalez recently received a 20-year sentence for leading a group of 10 people who stole and then sold 40 million credit card numbers from customers of various companies that had unsecured wireless access points in the Miami area (Qualters, 2010 ).

Advanced information technologies and communication devices make white-collar crimes easier to commit, while having little impact on street crime (as they are primarily used for interacting with nonphysical constructs, which is the general province of white-collar crime). These technologies have become increasingly common across diverse social strata in recent years (Zickuhr & Smith, 2012 ). Unlike the portable communications technologies of the 1980s, the ability to possess and utilize these new technologies is not restricted to those with substantial incomes and/or higher levels of education. Their comparatively low price, combined with their ever increasing capabilities, make them the ideal method of committing crime. The widespread adoption of these technologies in the United States is a positive sign in the vast majority of respects, but a logical consequence of increasing the online population is that there are more opportunities to either commit a white-collar crime or become a victim of one.

Although these factors give researchers confidence that white-collar crime should be occurring in relatively large numbers (and should be growing at a time when other crimes are shrinking), proving it or putting a hard number on it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, due primarily to the definitional debate that has plagued the field for decades.

Similarly, efforts to reduce white-collar crimes are difficult to analyze with respect to their effectiveness, since the inability to define what constitutes white-collar crime means an inability to track its prevalence accurately. If we can’t establish a cause-and-effect relationship between a treatment and a reduction, we can never conclusively establish the effectiveness of that treatment.

The lack of a universal definition of white-collar crime poses more far-reaching consequences than simply lack of consistency; it is actually the key to the problem of analyzing white-collar crime. If something cannot be defined, then it cannot be accurately measured. Under varying definitions, white-collar crime can constitute anything from a simple check forgery to large-scale corporate malfeasance and sophisticated computer crimes, that is, he definitional debate regarding whether some types of financial fraud, identity theft, and computer/Internet crimes really constitute white-collar crime. This definitional variance makes it extremely difficult to gather information pertaining to criminal acts because, even if white-collar crime data are captured, it does not mean that the data will be comparable to other data or that anything meaningful can be garnered from its analysis.

Adding to the confusion is an apparent lack of consistency in the handling of white-collar offenses. Some highly damaging offenses may be handled administratively or civilly by a regulatory agency as opposed to criminally, while other similarly damaging offenses may be handled through the traditional criminal prosecutorial process. Administrative regulatory actions, civil court actions, and out of court settlements (where part of the settlement includes “no admission or finding of guilt” in return for a hefty financial settlement)—all combine to conceal the true presence of what would ordinarily be considered white-collar offenses but are not captured as an offense or enforcement statistic.

A lack of crime and arrest statistics goes so far as to “implicitly suggest that white-collar crime is not as serious as conventional crimes” (which law enforcement takes exhaustive measures to count accurately) (Albanese, 1995 ). As already discussed, this is most certainly not the case. Incidences of white-collar crimes not only affect many more individuals than traditional street crimes, but they also bring with them significant financial, emotional, and even physical tolls for the victims (NW3C, 2006 ).

Without question, the analysis of statistics on crimes committed, by whom, where, and when, details about perpetrators and victims, including background, personality traits, ethnicity, and age, can be considered “essential” in understanding crime trends. Knowledge of the “who, what, when and where” of any criminal act is required for developing strategies to prevent and reduce crime. Knowledge of common characteristics of offenders is necessary for understanding how to develop sentencing practices that help deter criminal activity and for developing programs to treat offenders so that they can be rehabilitated. The lack of a common definition of the term white-collar crime then, presents a major obstacle to using normal approaches to studying and dealing with it.

For white-collar crime, there is also the problem of even knowing when one has been the victim. It’s far easier for victims of a street crime to recognize that they have been victimized than it is for the persons who have fallen for a financial scam. One of the key elements of this type of scam is to keep the victims from finding out that they have been taken, for as long as possible. This calls to mind a simple formula in criminal law that is often used to determine whether a police report is even prepared by an investigating officer: “No complainant, no crime.” If the victim refuses to prosecute, no report of the offense is prepared, which means that no crime is added to the statistics; however, a criminal act has still occurred, one that fails to appear in the overall statistical profile of crime. If the victim is not even aware that he or she has been victimized, it’s unlikely that a true measurement of the prevalence of the crime will be possible.

The decision of whether one chooses to address issues through administrative or civil avenues, as opposed to criminal, will also determine whether that act is even defined as a crime. The problem for those charged with enforcement may involve consideration of whether the offense was a product of the actions of one person or of multiple people within an organization working together. The issue then becomes whether the act was committed with knowledge and intent, with disregard for the negative impacts their act would cause, or whether the group was simply committing a misguided act with an eye toward the financial bottom line.

Regardless of how the debate ultimately resolves itself, it is critical that we continue to educate the public regarding the methods of white-collar crime victimization, better enabling them to identify when they have been victimized and encouraging them to report these crimes to the police. Furthermore, regulatory agencies need to make data more accessible to those studying white-collar crime; while many corporations are understandably reticent to provide such data, the fact remains that this is a serious issue that can relate to public safety. It needs to be dealt with partly through transparency of data. Sharing information on how various enforcement and regulatory agencies handle white-collar crimes allows multiple entities to learn from one another what works best in dealing with the problem. If researchers and practitioners cannot empirically support claims regarding the incidence and prevalence of white-collar crimes, then it is impossible to justify the expenditure of funds for research and development that could potentially impact the lives of millions of citizens through the prevention and control of these ever-expanding crimes.

Suggested Reading

- Albanese, J. (1995). White collar crime in America . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Calivita, K. , Pontell, H. , & Tillman, R. (1997). Big money crime: Fraud and politics in the savings and loan crisis . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Edelhertz, H. (1970). The nature, impact, and prosecution of white-collar crime . Washington, DC: National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice.

- Friedrichs, D. (2007). Trusted criminals (3d ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Garrett, B. (2014). Too big to jail: How prosecutors compromise with corporations . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Geis, G. , Meier, R. F. , & Salinger, L. M. (1995). White-collar crime: Classic and contemporary views (3d ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Gerber, J. , & Jensen, E. L. (2007). Encyclopedia of white-collar crime . Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- National White Collar Crime Center . (1996). Proceedings of the academic workshop: Definitional dilemma: Can and should there be a universal definition of white collar crime? Morgantown, WV: National White Collar Crime Center.

- National White Collar Crime Center . (2010). National public survey on white collar crime, 2010 . Fairmont, WV: National White Collar Crime Center. Retrieved from https://www.nw3c.org/docs/research/2010-national-public-survey-on-white-collar-crime.pdf?sfvrsn=8 .

- Pontell, H. N. (2011, November 4). The future of financial fraud . Paper presented at the Stanford Center for the Prevention of Financial Fraud Conference: The State and Future of Financial Fraud, Washington, DC.

- Pontell, H. N. , & Geis, G. (2007). International handbook of white-collar and corporate crime . New York: Springer.

- Rossoff, S. M. , Pontell, H. N. , & Tillman, R. (1998). Profit without honor: White collar crime and the looting of America . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Simpson, S. , & Weisburd, D. (2009). The criminology of white-collar crime . New York: Springer.

- Sutherland, E. (1949). White collar crime . New York: Dryden Press.

- Van Slyke, S. R. , Benson, M. L. , & Cullen, F. T. (2016). The Oxford handbook of white-collar crime . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weisburd, D. , Waring, E. , & Chayet, E. (1995). Specific deterrence in a sample of offenders convicted of white collar crimes. Criminology , 33 (4), 587–607.

- Apte, U. , Karmarkar, U. S. , & Nath, H. K. (2008, Spring). Information services in the U.S. economy: Value, jobs and management implications. California Management Review , 50 (3), 12–30.

- Assad, M. (2015, October 20). Madoff scam still cuts local victims . The Morning Call . Retrieved from http://www.mcall.com/business/mc-bernie-madoff-victims-20151020-story.html .

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners . (2016). Report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse . Austin, TX: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. Retrieved from https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/acfepublic/2016-report-to-the-nations.pdf .

- Barnett, C. , U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation . (2000). The measurement of white-collar crime using uniform crime reporting (UCR) data . Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/nibrs/nibrs_wcc.pdf .

- BSA . (2014, June). The compliance gap: BSA global software survey . Retrieved from http://globalstudy.bsa.org/2013/downloads/studies/2013GlobalSurvey_Study_en.pdf .

- Bureau of Labor Statistics . (2013, December). Occupational employment projections to 2022 . Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/article/occupational-employment-projections-to-2022.htm .

- Bureau of Labor Statistics . (n.d.). International comparisons of annual labor force statistics, 1970–2012 . Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/fls/flscomparelf.htm#chart06 .

- Calavita, K. , Pontell, H. , & Tillman, R. (1997). Big money crime: Fraud and politics in the savings and loan crisis . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Corelogic . (2014). Mortgage fraud report 2014 . Retrieved from http://www.corelogic.com/research/mortgage-fraud-trends/2014-mortgage-fraud-trends-report.pdf .

- Cooke, C. (2015, November 30). Careful with the panic: Violent crime and gun crime are both dropping . Retrieved from http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/427758/careful-panic-violent-crime-and-gun-crime-are-both-dropping-charles-c-w-cooke .

- Cooper, A. , & Smith, E. L. (2011, November). Homicide trends in the United States, 1980 – 2008 . Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf .

- Dryden, J. (2007). Counting the cost: The economic impacts of counterfeiting and piracy: Preliminary findings of the OECD study . Third Global Congress on Combating Counterfeiting and Piracy, January 30–31, 2007, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.ccapcongress.net/archives/Geneva/Files/Dryden.pdf .

- European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicines . (2008). The counterfeiting superhighway. Retrieved from http://v35.pixelcms.com/ams/assets/312296678531/455_EAASM_counterfeiting%20report_020608.pdf .

- Federal Trade Commission . (2016, February). Consumer sentinel network data book: January—December 2015 . Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/consumer-sentinel-network-data-book-january-december-2015/160229csn-2015databook.pdf .

- File, T. , & Ryan, C. (2014, November). Computer and internet use in the United States: 2013. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/acs-internet2013.pdf .

- Gordon, G. (1996). The impact of technology-based crime on definitions of white collar/economic crime: Breaking out of the white collar crime paradigm. In Proceedings of the academic workshop: Definitional dilemma: Can and should there be a universal definition of white collar crime? Morgantown, WV: National White Collar Crime Center.

- Government’s Sentencing Memorandum No. CR07-187MJP, U.S. v. Soloway . Retrieved from http://www.spamsuite.com/webfm_send/338 .

- International Chamber of Commerce . (n.d.). Global impacts study . Retrieved from http://www.iccwbo.org/Advocacy-Codes-and-Rules/BASCAP/BASCAP-Research/ .

- Internet Crime Complaint Center . (2016). 2015 internet crime report . Retrieved from https://pdf.ic3.gov/2015_IC3Report.pdf .

- Interpol . (2016, April 1). Interpol backs world IP day . Retrieved from http://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News/2016/N2016-054 .

- Javelin . (2015, March 2). Identity fraud: Protecting vulnerable populations . Retrieved from https://www.javelinstrategy.com/coverage-area/2015-identity-fraud-protecting-vulnerable-populations .

- Johnson, D. T. , & Leo, R. A. (1993). The Yale white-collar crime project: A review and critique. Law of Social Inquiry , 18 (1), 63–99.

- National Conference on Aging (2016). The MetLife study .

- NW3C . (1996). Proceedings of the academic workshop: Definitional dilemma: Can and should there be a universal definition of white collar crime? Morgantown, WV: National White Collar Crime Center.

- NW3C . (2006). The 2005 national public survey on white collar crime . Fairmont, WV: National White Collar Crime Center. Retrieved from https://www.nw3c.org/docs/research/2010-national-public-survey-on-white-collar-crime.pdf?sfvrsn=8 .

- NW3C . (2010). National public survey on white collar crime, 2010 . Fairmont, WV: National White Collar Crime Center. Retrieved from https://www.nw3c.org/docs/research/2010-national-public-survey-on-white-collar-crime.pdf?sfvrsn=8 .

- PricewaterhouseCoopers . (2016). Global economic crime survey 2016 . Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/advisory/consulting/forensics/economic-crime-survey.html .

- Pontell, H. N. (2009). Identity theft: Bounded rationality, research, and policy. Criminology and Public Policy , 8 (2), 263–270.

- Pontell, H. N. (2016). Theoretical, empirical, and policy implications of alternative definitions of “white-collar crime”: Trivializing the lunatic crime rate. In S. Van Slyke , M. Benson , & F. Cullen (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of white-collar crime (pp. 39–56). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Popkin, J. (2008, September 22). “Pure greed” led spammer to bombard in-boxes . NBC News. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26797741/ .

- Public Citizen . (2002). “Corporate fraud and abuse taxes” cost the public billions . Retrieved from http://www.citizen.org/documents/corporateabusetax.pdf .

- Qualters, S. (2010, March 26). Computer hacker Albert Gonzalez sentenced to 20 years. The National Law Journal . Retrieved from http://www.nationallawjournal.com/id=1202446860357/Computer-Hacker-Albert-Gonzalez-Sentenced-to-20-Years?slreturn=20170107084449 .

- Ryan, C. , & Bauman, K. (2016, March). Educational attainment in the United States: 2015 . U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf .

- Saxby, P. , & Anil, R. (2012). Financial loss and suicide. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences , 19 (2), 74–76.

- Schrager, L. , & Short, J. (1978). Toward a sociology of organizational crime. Social Problems , 25 , 407–419.

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) . (2016, May 16). Mortgage company and executives settle fraud charges [Press Release]. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/news/pressrelease/2016-97.html .

- Stewart, E. (2015, July 9). White collar crime costs between $300 and $600 billion a year . Retrieved from http://www.valuewalk.com/2015/07/white-collar-crime-stats/ .

- Sutherland, E. (1940). White-collar criminality. American Sociological Review , 5 (1), 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.asanet.org/images/asa/docs/pdf/1939%20Presidential%20Address%20(Edwin%20Sutherland).pdf .

- The Economist . (2014, May 31). The $272 billion swindle: Why thieves love America’s health-care system . Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21603078-why-thieves-love-americas-health-care-system-272-billion-swindle .

- The Telegraph . (2009, June 11). Bernard Madoff fraud victim committed suicide to avoid bankruptcy shame . Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/5503929/Bernard-Madoff-fraud-victim-committed-suicide-to-avoid-bankruptcy-shame.html .

- True Link . (2015, January). The true link report on elder financial abuse 2015 . Retrieved from https://truelink-wordpress-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/True-Link-Report-On-Elder-Financial-Abuse-012815.pdf .

- Truman, J. , & Langton, L. (2015, September 29). Criminal victimization, 2014 . Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv14.pdf .

- Truman, J. , & Planty, M. (2012, October). Criminal victimization, 2011 . Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv11.pdf .

- UNESCO . (2016). Education: Literacy rate . UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved from http://data.uis.unesco.org/ .

- U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Division . (2015). Fraud statistics—overview . Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/796866/download .

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation . (1989). White collar crime: A report to the public . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation . (2011). Financial crimes report to the public . Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/financial-crimes-report-2010-2011 .

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation . (2014). Crime in the United States, 2013 . Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2013/preliminary-semiannual-uniform-crime-report-january-june-2013 .

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation . (2015). Crime in the United States, 2014 . Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/preliminary-semiannual-uniform-crime-report-january-june-2014 .

- Zickuhr, K. , & Smith, A. (2012, April 13). Digital differences . Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041312.pdf .

1. A complete treatment of every position of every participant of the proceedings would be far beyond the scope of this article. The citations that follow, referring to those proceedings of 1996, were selected simply to help illustrate the magnitude of the problem of finding an acceptable definition. Inclusion or exclusion of mention of any of the participants is not intended in any manner to suggest that any single contribution was superior or inferior to another. The citations used were selected simply to represent the various perspectives from which the group examined the task of defining the concept of white-collar crime.

Related Articles

- Professional Criminals and White-Collar Crime in Popular Culture

- Legal and Political Reponses to White-Collar Crime

- White-Collar Delinquency

- Public Knowledge About White-Collar Crime

- Corporate Crime and the State

- Individual, Educational, and Other Social Influences On Greed: Implications for the Study of White-Collar Crime

- Finance Crime

- Women and White-Collar Crime

- Theoretical Perspectives on White-Collar Crime

- State-Corporate Crime Nexus: Development of an Integrated Theoretical Framework

- White-Collar Crimes Beyond the Nation-State

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Criminology and Criminal Justice. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 02 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

Character limit 500 /500

White-Collar Crime Research

- Open Access

- First Online: 23 March 2018

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Petter Gottschalk 3 &

- Lars Gunnesdal 4

38k Accesses

6 Citations

One of the theoretical challenges facing scholars is to develop an accepted definition of white-collar crime. The main characteristic is that it is economic crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of an occupation. While Edwin Sutherland’s concept of white-collar crime has enlightened sociologists, criminologists, and management researchers, the concept may have confused attorneys, judges and lawmakers. One reason for this confusion is that white-collar crime in Sutherland’s research is both a crime committed by a specific type of person, and it is a specific type of crime. Later research has indicated, as applied in this book, that white-collar crime is no specific type of crime, it is only a crime committed by a specific type of person.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

- Convenience theory

- Criminology

Edwin Sutherland

- Gender perspectives

- Occupational crime

- Offence characteristics

- Offender characteristics

- Special sensitivity hypothesis

- Social status

Ever since Sutherland ( 1939 ) coined the term “white-collar crime”, there has been extensive research and debate on what to include and what to exclude from this offense category (e.g., Piquero and Benson 2004 ; Pontell et al. 2014 ; Stadler et al. 2013 ). In accordance with Sutherland’s original work, convenience theory emphasizes the position and trust enjoyed by the offender in an occupational setting (Shapiro 1987 ). Therefore, the organizational dimension is the core of convenience theory where the offender has access t o resources to commit and conceal financial crime.

The typical profile of a white-collar criminal includes the following attributes (Piquero and Benson 2004 ; Pontell et al. 2014 ; Stadler et al. 2013 ):

The person has high social status and considerable influence, enjoying respect and trust, and belongs to the elite in society.

The elite have generally more knowledge, money and prestige, and occupy higher positions than other individuals in the population occupy.

Privileges and authority held by the elite are often not visible or transparent, but known to everybody.

Elite members are active in business, public administration, politics, congregations, and many other sectors in society.

The elite is a minority that behaves as an authority towards others in the majority.

The person is often wealthy and does not really need the proceeds of crime to live a good life.

The person is typically well educated and connects to important networks of partners and friends.

The person exploits his or her position to commit financial crime.

The person does not look at himself or herself as a criminal , but rather as a community builder who applies personal rules for his or her own behavior.

The person may be in a position that makes the police reluctant to initiate a crime investigation .

The person has access to resources that enable involvement of top defense attorneys, and can behave in court in a manner that creates sympathy among the public, partly because the defendant belongs to the upper class, often a similar class to that of the judge, the prosecutor, and the attorney.

However, one of the theoretical challenges facing scholars in this growing field of research is to develop an accepted definition of white-collar crime. While the main characteristic is the foundation—economic crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of an occupation—other aspects lack precision (Kang and Thosuwanchot 2017 ).

Edwin Sutherland is one of the most cited criminologists in the history of the criminology research field. Sutherland’s work has inspired and motivated a large number of scholars in the field associated with his work. His ideas influence, challenge, and incentivize researchers. Sutherland’s research on white-collar crime is based on his own differential association theory. This learning theory of deviance focuses on how individuals learn to become criminals . Differential association theory assumes that criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons.

Sutherland’s ( 1939 , 1949 ) concept of white-collar crime has been so influential for various reasons. First, there is Sutherland’s engagement with criminology’s neglect of the kinds of crime of the powerful and influential members of the elite in society. Next, is the extent of damage caused by white-collar crime. Sutherland emphasized the disproportionate extent of harm caused by the crime of the wealthy in comparison to the much researched and popular focus on crime by the poor, and the equally disproportionate level of social control responses. Third, there is the focus on organizational offenders, where crime occurs in the course of their occupations. A white-collar criminal is a person who, through the course of his or her occupation, utilizes respectability and high social status to perpetrate an offense. Fourth, the construction of the corporation as an offender indicates that organizations can also be held accountable for misconduct and crime. Finally, there is the ability to theorize the deviant behaviors of elite members. Many researchers have been inspired by Sutherland’s groundbreaking challenge that mainstream criminology neglects the crime of the upper class and has a dominating focus on the crime of the poor. This was a major insight that began a dramatic shift and broadening in the subject matter of criminology that continues today.

Sutherland’s long-lasting influence on criminological, sociological and, more recently, on management thinking is observable across the globe, but in particular in the United States and Europe. Sutherland exposed crime by people who were thought of as almost superior, and who apparently did not need to offend as a means of survival. Businesspeople and professionals frequently commit serious wrongdoing and harm with little fear of facing criminal justice scrutiny. It is often the case that poverty and powerlessness is the cause of one kind of crime while excessive power can be the cause of another kind of crime.

Sutherland exemplified the corporation as an offender in the case of war crime where corporations profit heavily by abusing the state of national emergency during times of war. Corporate form and characteristics as a profit-maximizing entity shape war profiteering. This is organizational crime by powerful organizations that may commit environmental crime, war profiteering, state-corporate crime, and human rights violations.

While Sutherland’s concept of white-collar crime has enlightened sociologists, criminologists, and management researchers, the concept may have confused attorneys, judges, and lawmakers. In most jurisdictions, there is no offense labeled white-collar crime. There are offenses such as corruption, embezzlement, tax evasion, fraud , and insider trading, but no white-collar crime offense. Sutherland’s contribution to the challenge of concepts such as law and crime can be considered one of the strengths of his work as he showed that laws and legal distinctions are politically and socially produced in very specific ways. For lawmakers, there is nothing intrinsic to the character of white-collar offenses that makes them somehow different from other types of offenses.

One reason for this confusion is that white-collar crime in Sutherland’s research is both a crime committed by a specific type of person and a specific type of crime. Later research has indicated, as applied in this book, that white-collar crime is no specific type of crime; it is only a crime committed by a specific type of person. However, white-collar crime may indeed, sometime in the future, emerge as a kind of crime suitable for law enforcement as Sutherland envisaged it in his offender-based approach to crime, focusing on characteristics of the individual offender to determine the categorization of the type of crime.

Sutherland’s broader engagement with criminological and sociological theory in general, such as his theory of differential association and social learning, has been and still is influential. One aspect of the theory of differential association—social disorganization—has had a significant influence on later researchers.

It must be noted that Sutherland’s key constructs and definitions have divided criminology . Nelken ( 2012 ) suggests there is ambiguity about the nature of white-collar compared to ordinary crime. Croall ( 1989 : 157) phrased the question “Who is the white-collar criminal ?”:

White-collar crime is traditionally associated with high status and respectable offenders: the ‘crimes of the powerful’ and corporate crime. However, examination of one group of white-collar offences reveals that offenders were typically small businesses, employees, and those more properly described as ‘criminal businesses’. While this could be attributed to the ‘immunity’ of the corporate offender from prosecution , it can be argued that such patterns of offending reflect not only enforcement policies but also wider structural and market factors. Thus, analyses of economic and white-collar crime may concentrate overmuch on the corporate offender, and make over simplistic distinctions between ‘corporate’ and other varieties of white-collar offending.

Levi ( 2002 ) emphasized a wide socio-economic spectrum of fraud offending when discussing shaming and incapacitating business fraudsters.

Offense Characteristics

White-collar crime is illegal acts that violate responsibility or public trust for personal or organizational gain. It is one or a series of acts committed by non-physical means and by concealment to obtain money or property, or to obtain business or personal advantage (Leasure and Zhang 2017 ).

White-collar crime is a unique area of criminology due to its atypical association with societal influence compared to other types of criminal offenses. White-collar crime is defined in its relationship to status, opportunity, and access. This is the offender-based perspective. In contrast, offense-based approaches to white-collar crime emphasize the actions and nature of the illegal act as the defining agent. In their comparison of the two approaches, Benson and Simpson ( 2015 ) discuss how offender-based definitions emphasize societal characteristics such as high social status, power, and respectability of the actor. Because status is not included in the definition of offense-based approaches and status is free to vary independently from the definition in most legislation, an offense-based approach allows measures of status to become external explanatory variables.

Benson and Simpson ( 2015 ) approach white-collar crime utilizing the opportunity perspective. They stress the idea that individuals with more opportunities to offend, with access to resources to offend, and that hold organizational positions of power are more likely to commit white-collar crime. Opportunities for crime are shaped and distributed according to the nature of economic and productive activities of various business and government sectors within society.

Benson and Simpson ( 2015 ) do not limit their opportunity perspective to activities in organizations. However, they emphasize that opportunities are normally greater in an organizational context. Convenience theory, however, assumes that crime committed in an organizational context be called white-collar crime. This is in line with Sutherland’s ( 1939 , 1949 ) original work, where he emphasized profession and position as key characteristics of offenders.

White-collar crime research is a growing field with a number of scholars. Green ( 2007 ) discussed lying, cheating, and stealing, while Naylor ( 2003 ) developed a general theory of profit-driven crime. Some of the accumulated research will be presented in the theory of convenience. Crime-as-choice theory, as suggested by Shover et al. ( 2012 ) for white-collar crime, has links to convenience theory.

Offender Characteristics

The white-collar offender is a person of respectability and high social status who commits financial crime in the course of his or her occupation (Leasure and Zhang 2017 ). In the offender-based perspective, white-collar criminals tend to possess many characteristics that are consistent with expectations of high status in society. White-collar offenders display both attained status and ascribed status. Attained status refers to status that is accrued over time and with some degree of effort, such as education and income. Ascribed status refers to status that does not require any specific action or merit, but rather is based on more physically observable characteristics, such as race, age, and gender .

The main offender characteristics remain privilege and upper class. Early perception studies suggest that the public think that white-collar crime is not as serious as other forms of crime. Most people think that street criminals should receive harsher punishments . One explanation for this view is self-interest (Dearden 2017 : 311):

Closely tied to rational choice, self-interest suggests that people have views that selfishly affect themselves. Significant scholarly research has been devoted to self-interest-based views. In laboratory conditions, people often favor redistribution taxes when they would benefit from such a tax. This self-interest extends into non-experimental settings as well. For example, smokers often view increasing smoking taxes less favorably than non-smokers do.

In this line of thinking, people may be more concerned about burglary and physical violence that may hurt them. They may be less concerned about white-collar crime that does not affect them directly. Maybe those who are financially concerned about their own economic well-being will be more concerned about white-collar crime (Dearden 2017 ).