An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Editorial: Locus of Control: Antecedents, Consequences and Interventions Using Rotter's Definition

Stephen nowicki.

1 Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

Yasmin Iles-Caven

2 Bristol Medical School, Public Health Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

Ari Kalechstein

3 Executive Mental Health, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, United States

Jean Golding

Locus of control (LOC) is at the same time, one of the most popular and yet one of the most misused personality attributes in the social sciences. It was introduced into psychology in 1966 by Julian Rotter who conceptualized it as a generalized expectancy within his Social Learning Theory and defined it as follows:

“Internal vs. external control refers to the degree to which persons expect that a reinforcement or an outcome of their behavior is contingent on their own behavior or personal characteristic vs. the degree to which persons expect that the reinforcement or outcome is a function of chance, luck, or fate, is under the control of powerful others or is simply unpredictable. Such expectancies may generalize along a gradient based on the degree of semantic similarity of the situational cues.” (Rotter, 1966 ).

Although the number of studies with LOC as a major variable reaches into the thousands and research continues at a brisk pace up to the present day across disciplines, the way in which investigators have eroded, ignored, and misapplied Rotter's original definition of LOC is cause for scientific concern. Without an agreed upon definition of LOC and reliable ways of measuring it based on that definition, generalization across studies becomes difficult if not impossible.

The purpose of studies completed within this topic was to use Rotter's definition of LOC and measures of LOC consistent with that definition to investigate (1) the stability and change of children's and adults' LOC over time; Nowicki et al.(a) ; (2) antecedents of children's and adults' LOC [ Carton et al. ; Nowicki et al.(b) ]; (3) the association of parents' prenatal LOC with children's academic and social outcomes [ Golding, Gregory, Ellis, Nunes, et al. ; Nowicki et al.(c) ; Golding, Gregory, Ellis, Iles-Caven, et al. ]; (4) the association between change in parents LOC over time (6 years) and children's social success or failure [ Nowicki et al.(d) ; Nowicki et al.(e) ]; (5) the associations of children's LOC and internalizing and externalizing problems ( Flores et al. ); depression ( Costantini et al. ; Sullivan et al. ) and epilepsy ( Wolf et al. ); and (6) the viability of interventions focused on changing LOC ( Tyler et al. ).

Researchers within this topic gathered data by using construct valid tests for adults and children developed to be consistent with Rotter's definition of LOC as a generalized expectancy. Although some past studies have used measures of LOC that were dubious (e.g., one or two items plucked from a non-LOC scale) to evaluate the validity of LOC, the present studies were among the first to produce longitudinal information about the stability over time of LOC in children and adults (more stable in adults than children) and the impact of prenatal parental LOC on children's subsequent outcomes. Researchers also found that the greater the degree of externality in prenatal parents' LOC, the more negative were the children's outcomes in sleeping, eating, and emotional lability early in life and social/emotional adjustment and cognitive performance later in childhood. The association of prenatal parental LOC with children's outcomes was further supported by findings showing a significant association between parents' change toward internality over time (6 years) and more positive social and academic outcomes in their children when compared to parent child outcomes associated with parent LOC that remained the same or became more external over time.

Findings that parents' LOC is associated with children's outcomes suggests looking at the possibility that interventions focused on changing parental externality before children are born may be worthwhile. Support for this possibility was found in results indicating parental change toward internality was associated with positive child outcomes (as reflected in children's personal and social outcomes as rated by teachers). Results from another study indicated improvements in the parental relationship and improvement in their economic conditions were associated with parents becoming more internal. Although, cause and effect cannot be assigned, the findings suggest future research should be directed at evaluating if strengthening the parental dyad relationship and improving the family financial situations would result in parents changing toward internality and children's outcomes becoming more positive.

Other topic studies revealed more about possible parental behaviors, attitudes and actions related to children's LOC. Since, the last review of parental antecedents of children's LOC was published over a quarter century ago, a recent update was needed. What it found was that parents disciplinary actions characterized by authoritative approaches and parents more often contingently reinforcing their children's behavior/outcome sequences (as observed in laboratory interactions) are associated with greater internality. However, since there have been only a few observational studies of parent child interactions there is a need for more investigations spanning children at different ages of development.

A final set of studies within the LOC topic gathered information on associations between children's LOC and their personal, social, and physical outcomes. A longitudinal study of Spanish speaking children in northern Chile produced similar associations between children's externality and a greater frequency of internalizing and externalizing problems to those found previously with English speaking participants. Other studies revealed how internal LOC acts as a mediator to buffer against the development of depression in young high-risk children from compromised environments; a result found in high-risk adolescent children as well. Considering the LOC, depression association, the topic study that focused on a strength-based intervention with offenders to improve their LOC may have relevance for other populations of children. In any case, there is a general need for research to illuminate LOC antecedents as possible targets for inclusion in intervention programs to help children develop internality as a way to prevent depression.

A final study dealt with the impact of a chronic disease, in this case epilepsy, on children's LOC. When children experience a serious disease and/or disability like epilepsy they may erroneously “learn” to be more helpless than they actually are to deal with the affliction and its consequences. Children need the help of caretakers to learn the full impact of what outcomes their behavior is tied to so they can be active participants not only in their treatment, but in shaping their lives outside of treatment.

The take home message from this set of studies is that LOC as defined by Rotter and measured with scales consistent with his definition remains an important construct. The degree to which individuals view the connection between what they do and what happens to them appears to have relevance for parents expecting a child and in children dealing with social interactions, academic achievement, and/or chronic mental or physical disease. Because of the findings, more research closely tied to Rotter's social learning theory is needed to identify relevant antecedents of LOC expectancies and valid interventions to help children and adults learn to develop the full extent of their internality.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Many of this topics' content is based on data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC).

Funding. The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 217065/Z/19/Z) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. The authors will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website ( http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf ). This research was specifically funded by the John Templeton Foundation (Grant ref: 58223). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of this manuscript.

- Rotter J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement . Psychol. Monogr. 80 , 1–28. 10.1037/h0092976 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Brief research report article, development and validation of a measure for academic locus of control.

- 1 Department of Dynamic, Clinical Psychology and Health, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 2 Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Aosta Valley, Aosta, Italy

- 3 Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 4 Department of Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Previous research highlighted the significant role of locus of control in predicting academic achievement and dropout, emphasizing the need for reliable measures to identify factors that foster academic success. This study aimed to develop an academic locus of control (ALoC) measure. Participants were 432 Italian university students (69 males, 363 females) pursuing bachelor’s ( N = 339) and master’s ( N = 123) degrees in Italy. The ALoC scale resulted in two factors, internal (6 items) and external ALoC (12 items), which demonstrated satisfactory dimensionality and invariance across students’ gender and attending degree. Internal and external ALoC were, respectively, negatively, and positively associated with academic dropout. This study confirmed the importance of locus of control for academic achievement, suggesting that university programs should address students’ personal sense of failure while promoting a sense of mastery and responsibility for academic outcomes.

Introduction

The locus of control is an important predictor of academic achievement and dropout. Having an internal rather than external locus of control can positively affect constancy in studies. This research aims to develop and validate a measure for academic internal and external academic locus of control in university students. To this purpose, two studies were conducted. The first study explored the latent structure of the data to determine the number of latent dimensions of the scale. The second study tested the dimensionality of the scale, its replicability, and concurrent validity.

Academic locus of control

Several countries in Europe are characterized by high percentages of students’ dropout in higher education ( Vossensteyn et al., 2015 ). Italy is one of the countries with the lowest rates of graduates and the highest rates of university dropout ( Istat, 2019 ; Eurostat, 2020 ). Constructing reliable measures able to identify the factors that promote academic achievement represents a fundamental strategy for improving the Europe standards of higher education.

Previous research found an important role of locus of control (LoC) in predicting academic achievement and dropout ( Joo et al., 2013 ; Kovach, 2018 ). LoC has been defined as the belief regarding one’s level of control over one’s life outcomes ( Rotter, 1966 ). Individuals who attribute their life outcomes as depending on their behavior have an internal LoC, whereas individuals who perceive that life outcomes depend on environmental factors have an external LoC ( Galvin et al., 2018 ). Levenson (1973 , 1981) conceived LoC as composed of three dimensions: internal, powerful others, and chance. According to this model, people with an external LoC may perceive that their life is controlled by powerful others or rather that events are unpredictable and determined by chance ( Levenson, 1981 ).

Locus of control (LoC) represents a pivotal construct concerning performance within achievement contexts. Consequently, contemporary psychological research has exhibited a growing interest in comprehending its predictive significance across diverse domains, including the realms of employment ( Ng et al., 2006 ), higher education ( Ghasemzadeh, 2011 ), and health-related outcomes ( Kesavayuth et al., 2020 ). Given that the academic domain serves as an exemplary context for the pursuit of various outcomes, it becomes imperative to investigate the role of LoC within this specific sphere.

Rotter (1975) proposed that greater predictive accuracy within specific contexts could be achieved through the development of context-specific measurement scales. Subsequently, in 1985, Trice developed the Academic Locus of Control Scale for College Students, which offered a valuable instrument for exploring students’ LoC within the academic domain. The work of Trice’s (1985) provided a clear definition of academic LoC, characterizing it as a set of expectations concerning the influence of one’s efforts and behaviors on academic performance. In 2013, Curtis and Trice conducted a study aimed at revisiting the scale’s structure and validity, 30 years after its initial development, resulting in an updated version of this measurement tool. Both the original scale and its updated version utilized a True/False response format, which posed a potential limitation in capturing the full spectrum of participants’ responses.

For what concern the Italian context, several prior studies have established the predictive power of LoC on various academic variables, including learning ( Cascio et al., 2013 ), academic self-efficacy ( Sagone and Caroli, 2014 ), and procrastination ( Sagone and Indiana, 2021 ). Notably, these studies relied on generic measurement tools for LoC, primarily due to the absence of a dedicated scale specifically designed for assessing academic locus of control. The existence of a specific measure of academic LoC can provide researchers with a more precise and comprehensive understanding of the role of LoC in educational outcomes.

Current study

This research aimed to develop a measure for academic internal and external LoC in university students. Specifically, it was intended to create a contemporary measurement scale, drawing upon the foundations of prior instruments that have demonstrated robust construct validity and reliability. In doing so, we provided participants with the option to respond using a Likert scale, as opposed to a dichotomous true/false format. The adoption of the Likert scale offers a more comprehensive and nuanced insight into participants’ responses, enabling the capture of the full spectrum of variance in their answers. Consequently, this approach provides enhanced opportunities for conducting correlational analyses and delving deeper into the data.

To this end, the Levenson scale was adapted to the academic context, leaving the item structure unchanged while replacing generic concepts such as “life” or “interests” with academic-related concepts such as “academic success” or “exam outcomes.” The scale was then administered to university students through two studies: The first was conducted to explore the latent structure of the scale and its reliability; the second was performed to confirm the scale dimensionality and test the invariance of the structure across gender (males versus females) and students attending degree, such as Bachelor of Art (BA) vs. Master of Art (MA), running a multigroup Confirmative Factor Analysis (CFA). Furthermore, the concurrent validity of the scale was tested investigating the association with the intention to dropout.

The aim of the first study was to explore the latent structure of the data to determine the number of latent dimensions of the scale. Therefore, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed. Further item analysis was conducted to assess the reliability of the scales as emerged from the EFA. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Sapienza, University of Rome. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Participants

Participants of the study consisted of 206 University students (36 males and 170 females), with an average age of 22.9 y.o. (SD = 4.97). One hundred and forty-two participants were attending a BA, whereas 64 were attending a MA.

Instruments

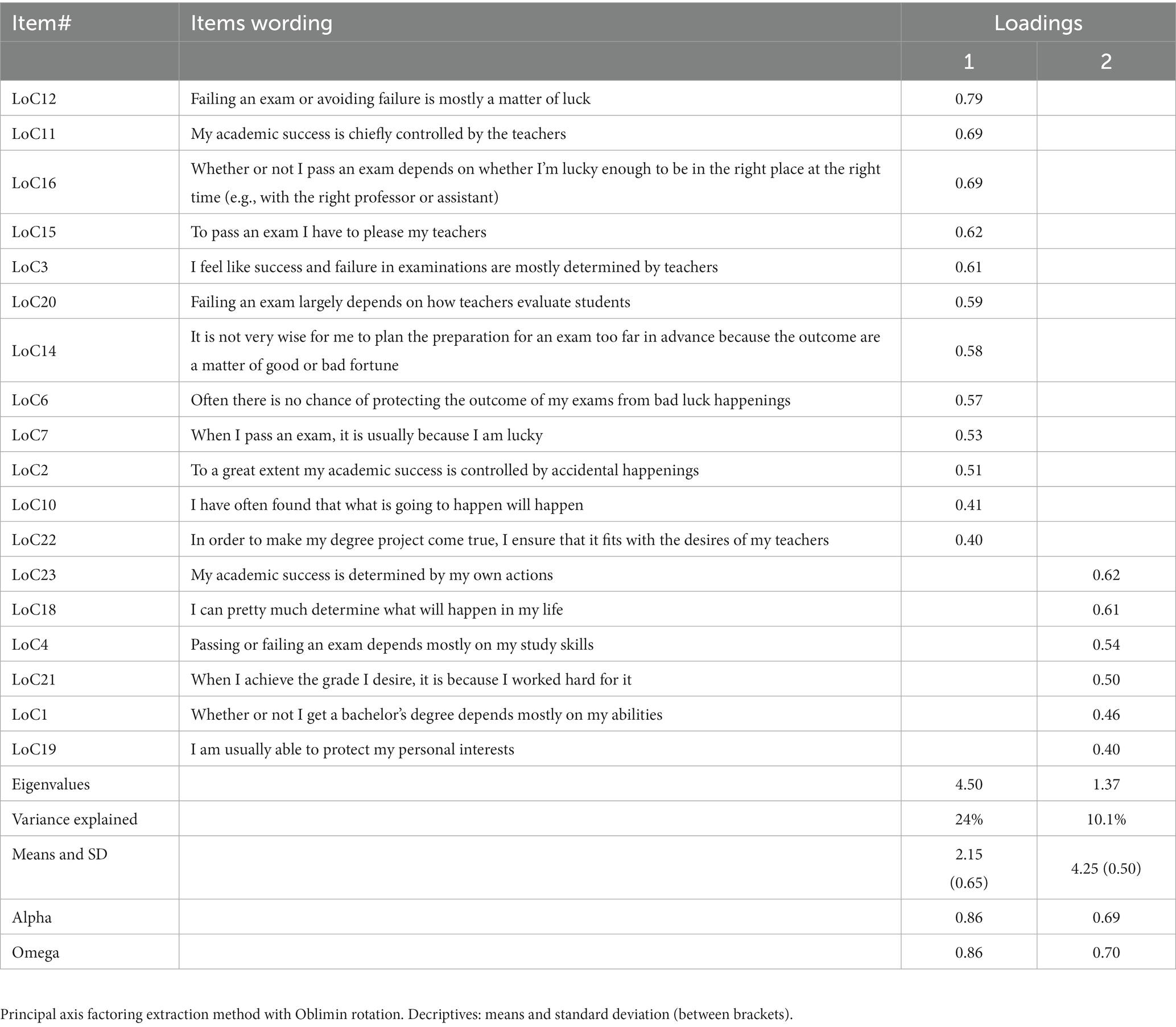

The Academic Locus of Control (AloC) scale of 24 items was administered. Participants had to answer to each item with a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) Completely disagree to (5) Completely agree. Items wording and psychometrics are showed in the result section ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Factor loading matrix after Oblimin rotation, items wording, descriptive, and reliability of the scales.

An Explorative Factor Analysis (EFA) on the initial 24 items of the scale was performed to investigate the latent structure of the data (Principal Axis Factoring). Assumptions check on the correlation matrix revealed that Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant, chi-square (153) = 1,174, p < 0.001, outlining that items were correlated enough so that the correlation matrix diverges significantly from the identity matrix. Both scree-plot and eigenvalue greater than 1 suggested a two-factor solution (first eight eigenvalues were: 5.18, 1.56, 0.78, 0.59, 0.39, 0.33, 0.33, and 0.21). After Oblimin rotation, the factor loading matrix was examined. Six items with high factor loadings on both factors (greater than 0.40), or which loaded lower than 0.40 on one factor, were deleted from the analysis (items #9, 13, 17, 8, 24, 5). Afterwards, the EFA was run on the remaining 18 items. The two-factor solution was once again confirmed by the scree plot inspection (first eight eigenvalues were: 4.50, 1.37, 0.53, 0.49, 0.29, 0.09, 0.07, and 0.00).

Factor 1 was composed by 12 items, with good factor loadings that ranged between 0.79 and 0.40, with an average factor loading of 0.58, which referred to External AloC covering both chance and powerful-others aspects of the construct (about 24% of the variance explained). Factor 2 was composed by the remaining 6 items with good loadings ranging between 0.62 and 0.40, with an average factor loading of 0.52, and that regarded the Internal AloC dimension (about 10.1% of the variance explained). Overall, the two factors accounted for the 34.1% of variance and were moderately and negatively correlated (−0.24). The full loading matrix is given in Table 1 .

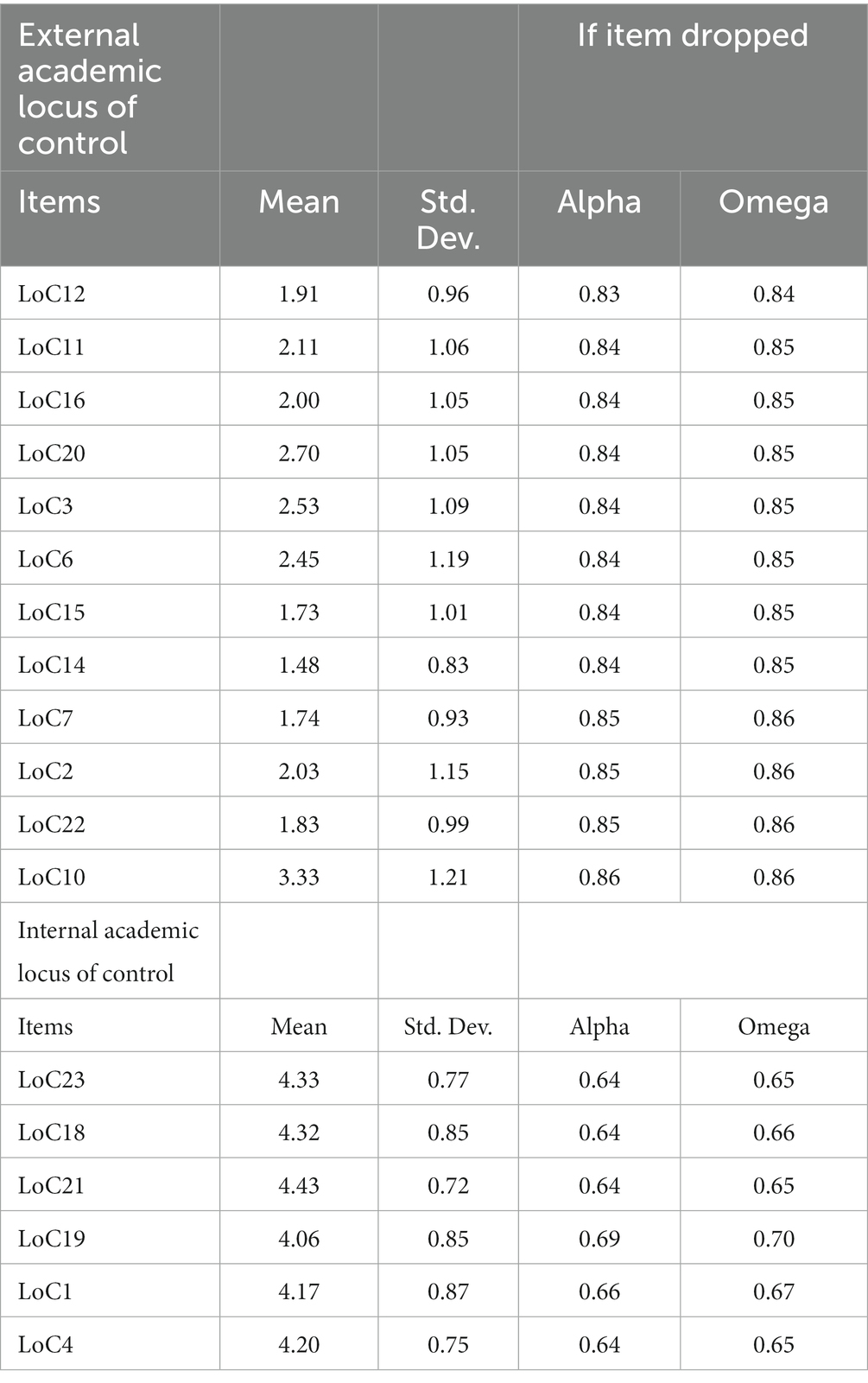

Descriptives and internal consistency of both the External and Internal AloC scales were reported in Table 1 . Both Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega converged and proved to be good, revealing that the scales were fairly reliable. In Table 2 , items descriptive and reliability statistics of both scales are reported. The statistics of reliability if a given item would be deleted clearly indicated that none of the items would substantially increase the reliability of the scales if dropped out.

Table 2 . Item reliability statistics of the academic locus of control scales.

The aim of the study two was to further test the dimensionality of the scale and its replicability employing a CFA. To this purpose, a multigroup CFA was conducted to investigate whether the factor model, emerged from the previous EFA, could be generalized showing measurement invariance across the independent sub-populations of males and females’ students and students attending a BA or a MA. Reliability was assessed, and concurrent validity of the scales was eventually tested against an external criterium, namely intentions to dropout university career. If the AloC scales would exhibit concurrent validity, we expect that an internal AloC would be negatively related to dropout intentions while external AloC would be positively related.

Participants of the study consisted of 226 University students (33 males and 193 females), with an average age of 23.2 y.o. (SD = 6.02). One hundred and ninety-seven participants were attending a BA, whereas 59 were attending a MA.

The final reduced version of the AloC scale of 18 items was administered. The items of the scales were given in Table 1 . Intention to dropout of university was measured using a six-item scale based on an earlier-developed measure by Bonino et al. (2005) and already used in previous studies ( Morelli et al., 2021 , 2023b ). An example item is: “Have you ever seriously thought about dropping out of university?.” Participants had to answer each item of the questionnaires with a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) Completely disagree to (5) Completely agree. The total score, obtained summing the scores of each item, was used. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.77 and McDonald’s Omega was 0.79.

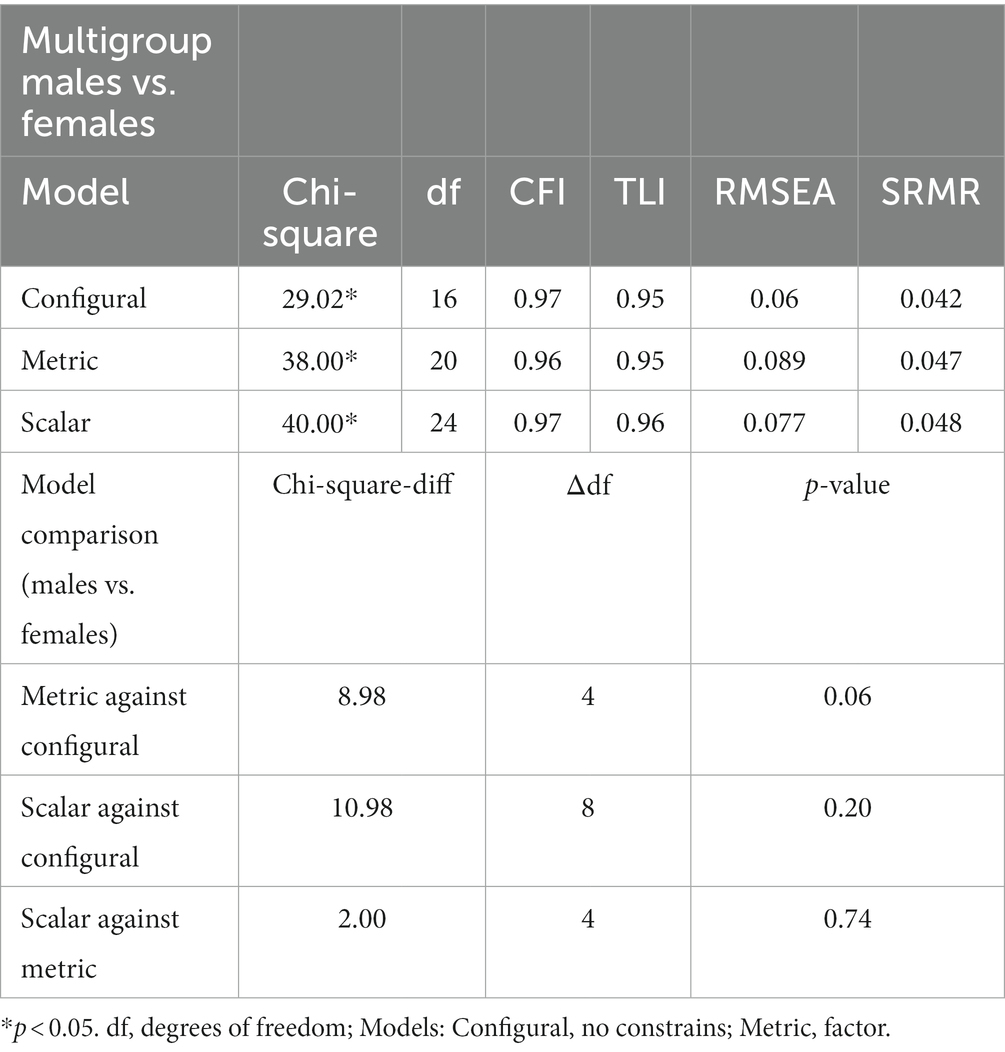

A CFA was conducted to test the structure of the scale in an independent sample, showing good fit indexes, chi-square (8) = 24.4, p = 0.002, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.036, RMSEA = 0.069. Measurement invariance across gender was then assessed. Firstly, we examined the configural invariance (M 0 ), i.e., an unconstrained baseline model in which all parameters freely differ between males and females’ students. Secondly, the metric invariance was examined (M 1 ), i.e., a model in which all factor loadings are simultaneously constrained across gender groups. Finally, the scalar invariance M 2 was tested, i.e., a model in which the intercepts are constrained to be equal across groups. As can be noted in Table 3 , all models exhibited good fit indexes.

Table 3 . Multigroup confirmative factor analysis and comparison between the models of measurement invariance (males vs. females).

All nested models were formally contrasted via the Δχ 2 comparison. The comparison M 1 versus M 0 showed a non-significant Δχ 2 : this result suggests no significant group differences for factor loadings supporting metric invariance ( Table 3 ). In other words, males and females’ students attributed the same meaning to the latent constructs under investigation. Furthermore, both the M 0 and M 1 were also tested and compared to the scalar invariance model M 2 . Result always showed a non-significant Δχ 2 . Therefore, scalar invariance was supported meaning that also the levels of the underlying items (intercepts) may be considered equal in both groups.

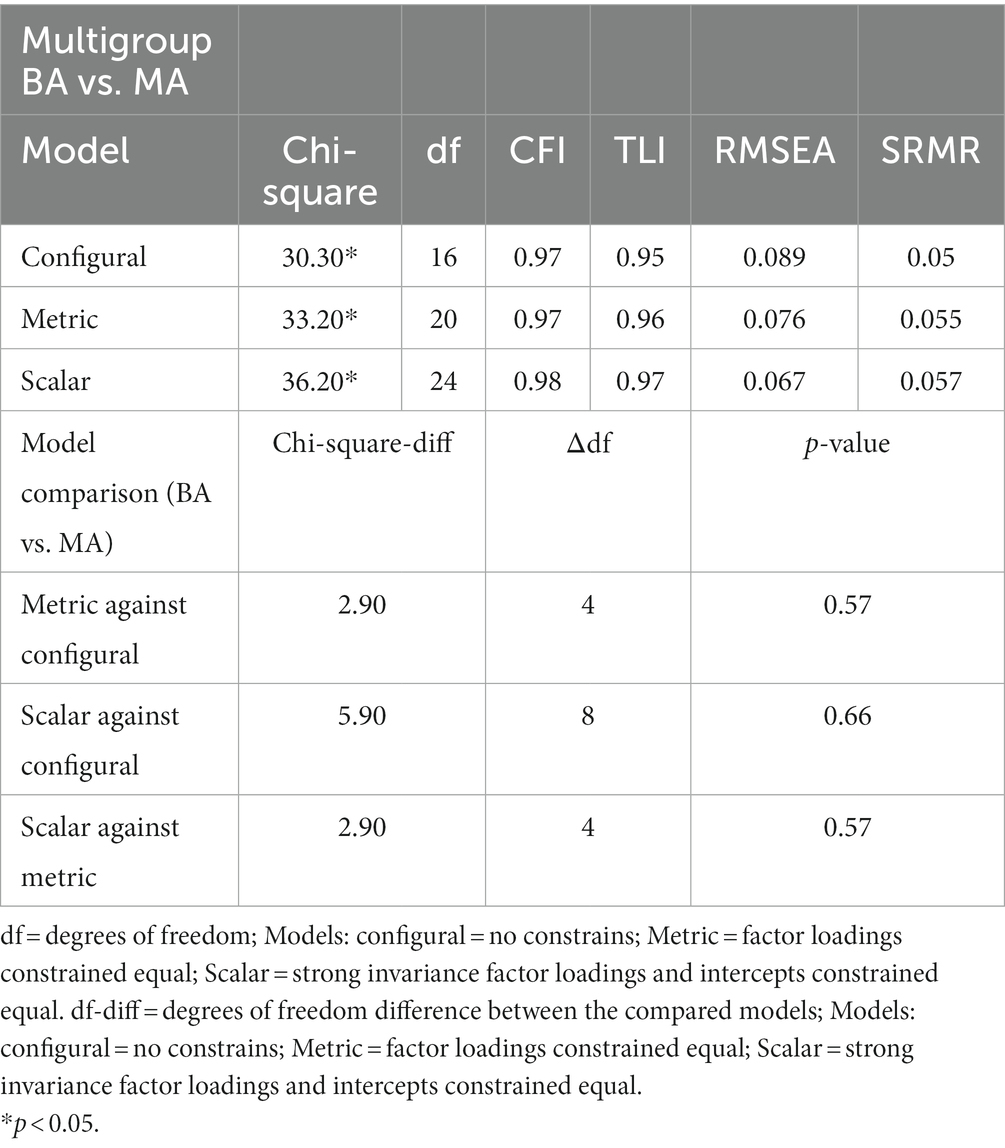

The same pattern of analyses was replicated considering BA vs. MA students as grouping variable. Results are reported in Table 4 confirming the measurement invariance of the scale also for these two groups.

Table 4 . Multigroup confirmative factor analysis and comparison between the models of measurement invariance (BA vs. MA).

Internal consistency for both scales were satisfactory and Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega substantially converged. External AloC had an Alpha of 0.83 and an Omega of 0.84, while Internal AloC showed an Alpha of 0.77 and an Omega of 0.79. An item analysis for each item was performed revealing that none of the items would increase the reliability of each of the scales in case it would have been dropped out.

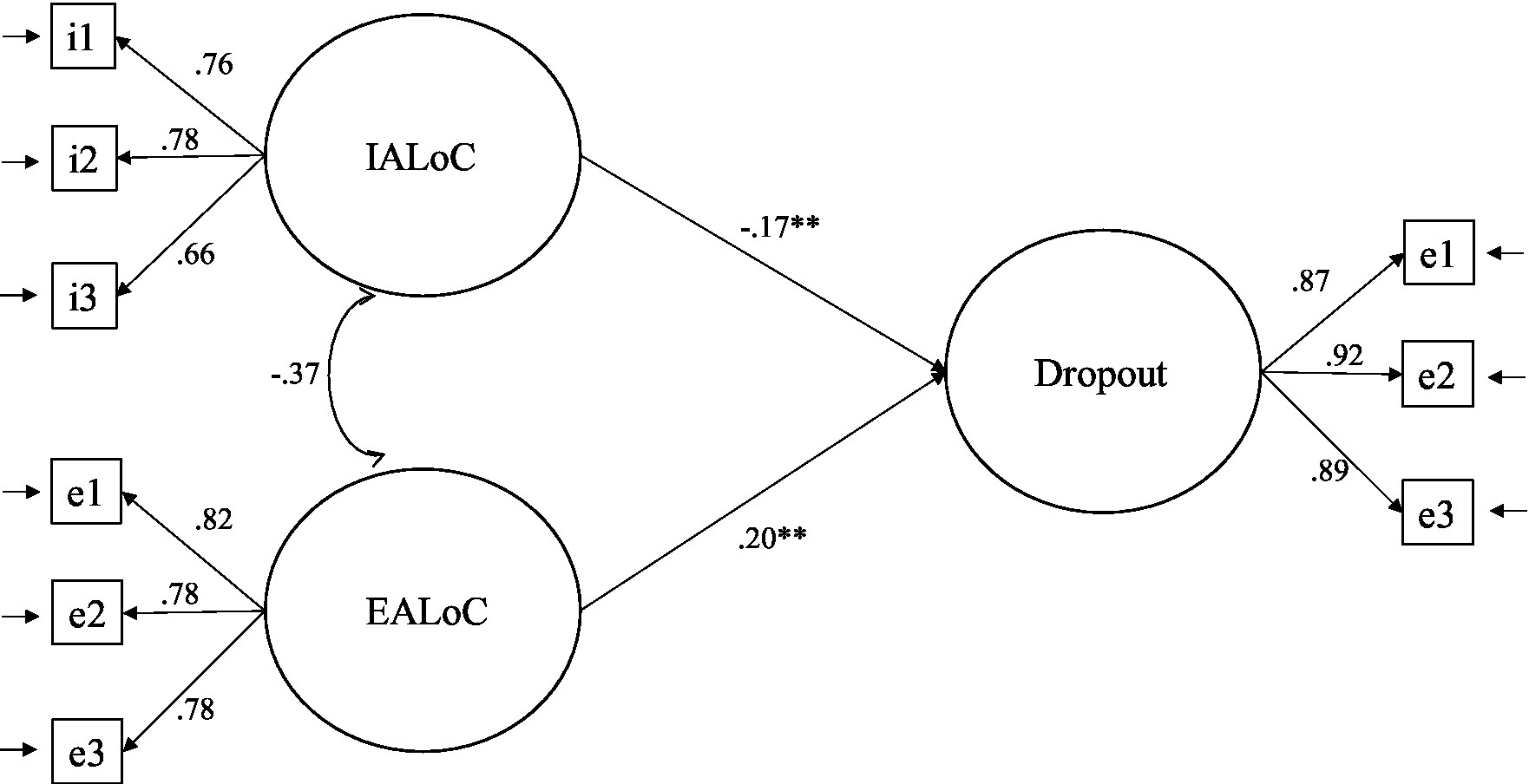

Concurrent validity was tested against an external academic outcome, namely intentions to dropout the university career. At bivariate level, it was found that External AloC was positively related to dropout, r = 0.30, p < 0.001, while Internal AloC was negatively related, r = −0.21, p < 0.001. A SEM with latent variables was performed to test the predictions including External AloC and Internal AloC as exogenous variables and dropout as endogenous variable. The model exhibited good fit indexes, chi-square (24) = 24.4, p = 0.002, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.033, RMSEA = 0.053 (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Structural equation model with latent variables. IALoC refers to “internal academic locus of control” and EALoC to “external academic locus of control.”

The present study was aimed at developing and validating a measure to investigate AloC in university students based on previous scales of LoC ( Levenson, 1973 , 1981 ). While Levenson scale consisted of three dimensions, the AloC scale resulted in two factors meeting the criteria of the internal (6 items) and external AloC (12 items), where the latter included the two dimensions of powerful others and chance. Explorative analysis revealed a final scale composed of 18 items.

The second study confirmed the factor model of the AloC and its generalizability. The two factors were confirmed by the invariance across students’ gender and attending degree. Males and females, as well as BA and MA students, assigned the same interpretations to external and internal AloC. Consistently with previous research, internal and external AloC resulted, respectively, negatively, and positively associated with the intention to dropout ( Arslan and Akin, 2014 ). Internal AloC can be considered a protective factor for university students as it relates to academic achievement, motivation, and success ( Anderson and Hamilton, 2005 ; Gifford et al., 2006 ; Ghasemzadeh, 2011 ). On the contrary, external AloC can hinder the university path as it relates to poor academic aspiration, low-grade point average, absenteeism, and academic withdrawal ( Nordstrom and Segrist, 2009 ; Landrum, 2010 ).

Students with internal AloC exert more effort compared to those with external AloC due to their belief in their ability to influence university outcomes. The AloC proved to be a good instrument to understand the extent to which students attribute their academic success or failure to their commitment. Such understanding equips educators with the potential to predict academic outcomes and proactively guide students toward success.

In Europe, the academic career is generally pictured as an important and prestigious developmental task to achieve for young adults. However, there is a lack of attention on those factors that may facilitate or, conversely, hinder the attainment of academic goals. The innovative aspect of the present study lies in the development of a scale that measures the orientation of internal or external LoC within the academic domain. Prior research has employed generic scales of locus of control, such as Rotter’s Internal-External Locus of Control Scale ( Rotter, 1966 ) and Levenson’s Questionnaire ( Levenson, 1973 ), to assess LoC. In other cases, specific scales on academic LoC have been used but, to date, can be considered dated in some of their aspects ( Trice, 1985 ; Akin, 2007 ; Curtis and Trice, 2013 ). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to introduce and validate a scale for measuring AloC after a significant time gap since the revision and validation of previous instruments. Furthermore, the AloC scale introduced in this study is grounded in Levenson’s original scale pertaining to the LoC construct. This approach ensures a robust conceptual framework encompassing both the external and internal dimensions of the construct while tailoring it to the unique context of the academic setting.

Additionally, the factorial structure of the AloC scale demonstrated robustness and consistency across students’ gender and degree programs. This finding suggests that the AloC scale exhibits validity and reliability across diverse groups, thus further strengthening the overall validity and generalizability of the AloC scale. Ultimately, the AloC is presented as an instrument that is easy and quick to administer, yet comprehensive. From our perspective, the scale presented in this study represents an outstanding tool for assessing and comparing AloC within university environments, eliminating the need for employing multiple instruments simultaneously and ensuring that the items are perceived as representative across diverse student groups.

Implications for practice

The development and validation of the AloC scale offer a valuable tool for early identification of students who may be at greater risk of dropping out of university. As our study has shown, students with external AloC tendencies tend to exhibit characteristics such as poor academic aspiration, low-grade point averages, absenteeism, and academic withdrawal—factors strongly associated with the intention to drop out. Identifying these students early in their academic career can enable timely interventions to provide the necessary support and resources to improve their academic outcomes.

Academic dropout is generally experienced as a personal failure that negatively impacts the overall quality of the university experience ( Heublein and Wolter, 2011 ; Cattelino et al., 2021 ; Morelli et al., 2023a , b ). University programs should reduce the personal sense of failure and improve the sense of mastery and responsibility of students in academic outcomes. Understanding the significance of AloC is fundamental to improving achievement within the context of higher education ( Morelli et al., 2021 ). Integrating the notion of autonomy and responsibility for achievement into programs can enhance students’ academic engagement and retention.

Incorporating the AloC scale into university programs could enhance the effectiveness of prevention and intervention strategies. For instance, academic advisors, counselors, and educators could use this scale to assess a student’s orientation towards internal or external AloC. Based on the results, personalized interventions and supportive trainings can be tailored to promote students’ academic motivation and sense of mastery. Empowering students with a sense of personal agency and control over their academic outcomes can contribute to reducing the feelings of personal failure often associated with academic dropout.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committee of the Sapienza University of Rome. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SA: Writing – review & editing. AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by a local grant from the University of Aosta Valley (FER20PRA.SHS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akin, A. (2007). Academic locus of control scale: a study of validity and reliability. Çukurova Univ. J. Educ. Faculty 34, 9–17.

Google Scholar

Anderson, A., and Hamilton, R. (2005). Locus of control, self-efficacy, and motivation in different schools: is moderation the key to success? Educ. Psychol. 25, 517–535. doi: 10.1080/01443410500046754

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arslan, S., and Akin, A. (2014). Metacognition: as a predictor of one’s academic locus of control. Educ. Sci, Theory Pract. 14, 33–39. doi: 10.12738/estp.2014.1.1805

Bonino, S., Cattelino, E., and Ciairano, S., (2005). Adolescents and risk. Behaviors, functions and protective factors . Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Cascio, M., Botta, V., and Anzaldi, V. (2013). The role of self efficacy and internal locus of control in online learning. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 9, 1826–6223. doi: 10.20368/1971-8829/789

Cattelino, E., Chirumbolo, A., Baiocco, R., Calandri, E., and Morelli, M. (2021). School achievement and depressive symptoms in adolescence: the role of self-efficacy and peer relationships at school. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 52, 571–578. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01043-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Curtis, N. A., and Trice, A. D. (2013). A revision of the academic locus of control scale for college students. Percept. Mot. Skills 116, 817–829. doi: 10.2466/08.03.PMS.116.3.817-829

Eurostat (2020). Smarter, greener, more inclusive? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/10155585/KS-04-19-559-EN-N.pdf/b8528d01-4f4f-9c1e-4cd4-86c2328559de (Accessed May 5, 2023).

Galvin, B. M., Randel, A. E., Collins, B. J., and Johnson, R. E. (2018). Changing the focus of locus (of control): a targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 820–833. doi: 10.1002/job.2275

Ghasemzadeh, A. (2011). Locus of control in Iranian university student and its relationship with academic achievement. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 30, 2491–2496. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.486

Gifford, D. D., Briceno-Perriott, J., and Mianzo, F. (2006). Locus of control: academic achievement and retention in a sample of university first-year students. J. Coll. Admiss. 191, 18–25.

Heublein, U., and Wolter, A. (2011). Studienabbruch in Deutschland: Definition, Häufigkeit, Ursachen, Maßnahmen [Dropout in Germany: Definition, Frequency, Cause, Interventions]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik 57, 214–236. doi: 10.25656/01:8716

Istat (2019). Rapporto SDGS, Informazioni statistiche per l’agenda 2030 in Italia [statistical information for agenda 2030 in Italy]. Available at: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2019/04/SDGs_2019.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2023).

Joo, Y. J., Lim, K. Y., and Kim, J. (2013). Locus of control, self-efficacy, and task value as predictors of learning outcome in an online university context. Comput. Educ. 62, 149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.027

Kesavayuth, D., Poyago-Theotoky, J., Tran, D. B., and Zikos, V. (2020). Locus of control, health and healthcare utilization. Econ. Model. 86, 227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2019.06.014

Kovach, M. (2018). A review of classical motivation theories: a study understanding the value of locus of control in higher education. J. Interdis. Stud. Educ. 7, 34–53. doi: 10.32674/jise.v7i1.1059

Landrum, R. E. (2010). Intent to apply to graduate school: perceptions of senior year psychology majors. N. Am. J. Psychol. 12, 243–254.

Levenson, H. (1973). Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 41, 397–404. doi: 10.1037/h0035357

Levenson, H. (1981). “Differentiating among internality, powerful others, and chance” in Research with the locus of control construct. Vol. 1 . Ed. H. M. Lefcourt (New York: Academic Press), 15–63.

Morelli, M., Baiocco, R., Cacciamani, S., Chirumbolo, A., Perrucci, V., and Cattelino, E. (2023a). Self-efficacy, motivation and academic satisfaction: the moderating role of the number of friends at university. Psicothema 35, 238–247. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2022.254

Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Baiocco, R., and Cattelino, E. (2021). Academic failure: individual, organizational, and social factors. Psicol. Educ. 27, 167–175. doi: 10.5093/psed2021a8

Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Baiocco, R., and Cattelino, E. (2023b). Self-regulated learning self-efficacy, motivation, and intention to drop-out: the moderating role of friendships at university. Curr. Psychol. 42, 15589–15599. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02834-4

Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., and Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: a meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 1057–1087. doi: 10.1002/job.416

Nordstrom, C. R., and Segrist, D. J. (2009). Predicting the likelihood of going to graduate school: the importance of locus of control. Coll. Stud. J. 43, 200–206.

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 80, 1–28. doi: 10.1037/h0092976

Rotter, J. B. (1975). Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal vs. external control of reinforcement. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 43, 56–67. doi: 10.1037/h0076301

Sagone, E., and Caroli, M. E. D. (2014). Locus of control and academic self-efficacy in university students: the effects of self-concepts. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 114, 222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.689

Sagone, E., and Indiana, M. L. (2021). Are decision-making styles, locus of control, and average grades in exams correlated with procrastination in university students? Educ. Sci. 11:300. doi: 10.3390/educsci11060300

Trice, A. (1985). An academic locus of control scale for college students. Percept. Mot. Skills 61, 1043–1046. doi: 10.2466/pms.1985.61.3f.1043

Vossensteyn, J. J., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B. W. A., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., et al. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe: main report. Europ. Union . doi: 10.2766/826962

Keywords: locus of control, academic achievement, dropout, university students, higher education

Citation: Morelli M, Cattelino E, Rosati F, Baiocco R, Andreassi S and Chirumbolo A (2023) Development and validation of a measure for academic locus of control. Front. Educ . 8:1268550. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1268550

Received: 28 July 2023; Accepted: 28 September 2023; Published: 12 October 2023.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2023 Morelli, Cattelino, Rosati, Baiocco, Andreassi and Chirumbolo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elena Cattelino, [email protected]

Locus of control and academic achievement: A literature review

A literature review on the relationship between locus of control (LOC) and academic achievement revealed that more internal beliefs are associated with greater academic achievement and that the magnitude of this relation is small to medium. Characteristics of the participants in the reviewed studies and the nature of the LOC and academic achievement measures were investigated as mediators of the relation. The relation tended to be stronger for adolescents than for adults or children. The relation was more substantial among males than among females. Stronger effects were associated with specific LOC measures and with standardized achievement or intelligence tests than with teacher grades. (30 ref) (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2006 APA, all rights reserved). © 1983 American Psychological Association.

Duke Scholars

Altmetric Attention Stats

Dimensions citation stats, published in, publication date, start / end page, related subject headings.

- Social Psychology

- 5205 Social and personality psychology

- 5204 Cognitive and computational psychology

- 1702 Cognitive Sciences

- 1701 Psychology

- 1505 Marketing

Academic anxiety, locus of control, and achievement in medical school

- PMID: 7277434

- DOI: 10.1097/00001888-198109000-00004

Programs designed to assist medical students in academic difficulty typically fail to consider the importance of such factors as academic anxiety and the individual's mechanisms for coping with stress. The authors have addressed this issue by examining relationships among prior achievement, academic anxiety, locus of control, and performance in the first year of medical school. Academic anxiety not only was found to be significantly related to first year performance, but also, when combined with a measure of prior achievement, resulted in a significant increase in prediction. Additional evidence is presented which suggests that the relationship between academic anxiety and achievement may be curvilinear. Locus of control was found to correlate significantly with academic anxiety and tended to shift in a direction of greater externality during the first year of medical school. Findings are discussed within the framework of existing psychological research, and implications are presented for medical admissions, curricula, and counseling.

- Achievement

- Anxiety / etiology

- Anxiety / psychology*

- Internal-External Control*

- Stress, Psychological / etiology

- Stress, Psychological / psychology

- Students, Medical / psychology*

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A student today is juggling many stressors and research has shown that academics is one of the major causes of stress. 1 Trying to balance their personal, social, and emotional well-being, they end up with emotional difficulties. 2,3 With all this struggle, they are unable to give their maximum performance in academics and face mental health issues. 4 Studies show that academic performance can ...

"Internal vs. external control refers to the degree to which persons expect that a reinforcement or an outcome of their behavior is contingent on their own behavior or personal characteristic vs. the degree to which persons expect that the reinforcement or outcome is a function of chance, luck, or fate, is under the control of powerful others ...

A quantitative review of research investigating the relationship between locus of control and academic achievement was conducted. Two basic conclusions resulted: (a) More internal beliefs are associated with greater academic achievement, and (b) the magnitude of this relation is small to medium. Characteristics of the participants in the reviewed studies (i.e., gender, age, race, and ...

The three main emerging concepts from the academic locus of control concept were academic, personal, and relationships with others. Sixty items were then created, 20 items for each subdomain of academic locus of control. After the items were created, think-aloud interviews and concurrent interviews were done to improve items.

A literature review on the relationship between locus of control (LOC) and academic achievement revealed that more internal beliefs are associated with greater academic achievement and that the magnitude of this relation is small to medium. Characteristics of the participants in the reviewed studies and the nature of the LOC and academic achievement measures were investigated as mediators of ...

the internal locus of control and academic achievement, and students with an internal locus of control are more successful in their academic lives (Richardson et al., 2012; Findley and

1. Introduction. A growing literature indicates that besides cognitive abilities, non-cognitive skills also play a crucial role in educational attainment (Almlund et al. Citation 2011; Borghans et al. Citation 2008).Locus of control (LoC), the subjective belief about the extent to which one's actions determine life outcomes, is one of the most widely studied non-cognitive skills.

This study compared measures of achievement motivation, life satisfaction, academic stress, and locus of control across 307 U.S. and international undergraduate students. Descriptive statistics and MANOVA were used to analyze the variables. A hierarchical multiple regression was employed to determine the extent to which locus of control, academic stress, and life satisfaction predicted ...

Perceived control of events is one motivational variable that appears to affect. children's academic achievement. In this review the conceptualization and measurement of the control dimension is discussed from three theoretical. perspectives: social learning theory, attribution theory, and intrinsic motivation.

Reviews literature on the relationship between locus of control and academic achievement and evaluates the most frequently used measures of locus of control. Although research suggests a strong relationship between locus of control and academic achievement, there remain problems explaining some of the inconsistent findings. Based on the expectancy value theory, a tentative model for measuring ...

Previous research highlighted the significant role of locus of control in predicting academic achievement and dropout, emphasizing the need for reliable measures to identify factors that foster academic success. This study aimed to develop an academic locus of control (ALoC) measure. Participants were 432 Italian university students (69 males, 363 females) pursuing bachelor's (N = 339) and ...

The previous research on locus of control or metacognition suggested that they are closely related to academic performance and can be taught to students to improve their academic and non-academic ...

The concept of locus of control has been applied to a wide variety of endeavors. ranging from beliefs about the after-life, to educational settings, and behavior in. organizations. For the purposes of this study, however, the concept of locus of control will be linked to children's behavior and academic achievement.

locus of control and chance locus of control, the higher the growth and development toward their academic enhancement.20 Research by Shepherd et al. has found a significant relationship between internal locus of control and academic growth, which shows that students with improved internal locus of control show high growth in

focus on determining factors that contribute to high school students' academic achievement. The role of self-efficacy and locus of control have been supported in research as factors associated with academic achievement (Tella, Tella, & Adika, 2008). In addition, researchers have indicated that parental involvement is important to student

The Relationship of Internal Locus of Control, Academic Achievement, and IQ in Emotionally Disturbed Boys Samual J. Perna, Jr., William R. Dunlap, and Jerry W. Dillard ABSTRACT The locus of control (LOC) of renforcement is a concept which refers to an individual's beliefs about how reinforcements are determined- internally or exter-nally.

RESEARCH IN ECONOMIC EDUCATION Achievement Goals, Locus of Control, and Academic Success in Economics By Lester Hadsell* An underexplored area within economics education is the influence that student motiva tion, fears, and feeling of control may have on learning outcomes and affective measures such as interest and enjoyment. This neglect in the

February 1, 1983. Published version (DOI) A literature review on the relationship between locus of control (LOC) and academic achievement revealed that more internal beliefs are associated with greater academic achievement and that the magnitude of this relation is small to medium. Characteristics of the participants in the reviewed studies and ...

negative relation. In conclusion, the research indicates that metacognition affects academic locus of control in that students whose internal academic locus of control is high are more likely to adopt metacognition than are students whose external academic locus of control is high. Therefore, the current findings act to increase our

The locus of control. The locus of control in research has been applied as an independent variable (Galvin et al. Citation 2018, 821) to account for engagement with situations, contexts, regulations and policies (Yang and Weber Citation 2019, 56) and is considered as a social concept which can be affected by and affect environmental factors (Ryon and Gleason Citation 2014, 130-131).

Research on academic achievement and locus of control typically finds a. internals perform better academically, but this difference does not surface until college b. externals perform better academically, but this difference disappears in college. c. internals perform better academically, and this seems to be true at all age levels. d.

Locus of control was found to correlate significantly with academic anxiety and tended to shift in a direction of greater externality during the first year of medical school. Findings are discussed within the framework of existing psychological research, and implications are presented for medical admissions, curricula, and counseling.