Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

University of the Philippines School of Economics

Up school of economics discussion papers.

- Publisher Info

- Serial Info

Corrections

Contact information of university of the philippines school of economics, serial information, impact factors.

- Simple ( last 10 years )

- Recursive ( 10 )

- Discounted ( 10 )

- Recursive discounted ( 10 )

- H-Index ( 10 )

- Euclid ( 10 )

- Aggregate ( 10 )

- By citations

- By downloads (last 12 months)

More services and features

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Accessibility Links

- Skip to content

- Skip to search IOPscience

- Skip to Journals list

- Accessibility help

- Accessibility Help

Click here to close this panel.

Purpose-led Publishing is a coalition of three not-for-profit publishers in the field of physical sciences: AIP Publishing, the American Physical Society and IOP Publishing.

Together, as publishers that will always put purpose above profit, we have defined a set of industry standards that underpin high-quality, ethical scholarly communications.

We are proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.

An Analysis on the Unemployment Rate in the Philippines: A Time Series Data Approach

J D Urrutia 1 , R L Tampis 2 and JB E Atienza 3

Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd Journal of Physics: Conference Series , Volume 820 , 5th International Conference on Science & Engineering in Mathematics, Chemistry and Physics 2017 (ScieTech 2017) 30–31 January 2017, Bali, Indonesia Citation J D Urrutia et al 2017 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 820 012008 DOI 10.1088/1742-6596/820/1/012008

Article metrics

29889 Total downloads

Share this article

Author e-mails.

Author affiliations

1 Director, Intellectual Property Management Office Chief, Center for Statistical Studies, Institute for Data and Statistical Analysis Office of the Vice President for Research, Extension, Planning and Development Polytechnic University of the Philippines – Sta. Mesa, Manila, Philippines

2 Polytechnic University of the Philippines – Parañaque Campus, Philippines

3 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, College of Science Polytechnic University of the Philippines – Sta. Mesa Manila, Philippines

Buy this article in print

This study aims to formulate a mathematical model for forecasting and estimating unemployment rate in the Philippines. Also, factors which can predict the unemployment is to be determined among the considered variables namely Labor Force Rate, Population, Inflation Rate, Gross Domestic Product, and Gross National Income. Granger-causal relationship and integration among the dependent and independent variables are also examined using Pairwise Granger-causality test and Johansen Cointegration Test. The data used were acquired from the Philippine Statistics Authority, National Statistics Office, and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. Following the Box-Jenkins method, the formulated model for forecasting the unemployment rate is SARIMA (6, 1, 5) × (0, 1, 1) 4 with a coefficient of determination of 0.79. The actual values are 99 percent identical to the predicted values obtained through the model, and are 72 percent closely relative to the forecasted ones. According to the results of the regression analysis, Labor Force Rate and Population are the significant factors of unemployment rate. Among the independent variables, Population, GDP, and GNI showed to have a granger-causal relationship with unemployment. It is also found that there are at least four cointegrating relations between the dependent and independent variables.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence . Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

Licence or Product Purchase Required

You have reached the limit of premium articles you can view for free.

Already have an account? Login here

Get expert, on-the-ground insights into the latest business and economic trends in more than 30 high-growth global markets. Produced by a dedicated team of in-country analysts, our research provides the in-depth business intelligence you need to evaluate, enter and excel in these exciting markets.

View licence options

Suitable for

- Executives and entrepreneurs

- Bankers and hedge fund managers

- Journalists and communications professionals

- Consultants and advisors of all kinds

- Academics and students

- Government and policy-research delegations

- Diplomats and expatriates

This article also features in The Report: Philippines 2021 . Read more about this report and view purchase options in our online store.

Economy From The Report: Philippines 2021 View in Online Reader

The Philippines is one of the fastest-growing economies of the past decade, averaging 6.4% growth per year over 2010-19. Indeed, an expanding and youthful population, combined with reforms and an ambitious infrastructure programme, have made it an enticing investment destination. Nevertheless, as is often the case in emerging markets, challenges regarding inequality – particularly the distribution of wealth and services – remain barriers to growth. The Covid-19 pandemic tested the country’s resilience in 2020, impacting major sectors. The Philippine government launched a four-pillar socio-economic strategy to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and aid the national recovery effort. The framework aims to provide emergency support for vulnerable groups and individuals; expand medical resources to fight Covid-19 and ensure the safety of health workers; implement fiscal and monetary initiatives to keep the economy afloat; and launch an economic recovery plan to create jobs and sustain growth. This chapter contains interviews with Carlos Dominguez, Secretary of Finance; and Shinichi Kitaoka, President, Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Articles from this Chapter

A new normal: positioning the economy to emerge from the pandemic with the ability to generate knowledge-based, inclusive growth obg plus.

The Philippines is one of the fastest-growing economies of the past decade, averaging 6.4% growth per year in 2010-19. Indeed, an expanding and youthful population, combined with reforms and an ambitious infrastructure programme, have made it an enticing investment destination. Nevertheless, as is often the case in emerging markets, challenges regarding inequality – particularly the distribution of wealth and services – remain barriers to growth. The Covid-19 pandemic tested the country’s…

Strategic support: A blend of policy options seeks to kick-start economic recovery OBG plus

The Philippine government launched a four-pillar socio-economic strategy to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and aid the national recovery effort. The framework aims to provide emergency support for vulnerable groups and individuals; expand medical resources to fight Covid-19 and ensure the safety of health workers; implement fiscal and monetary initiatives to keep the economy afloat; and launch an economic recovery plan to create jobs and sustain growth. Bayanihan 1 & 2 The government…

Strong fundamentals: Carlos Dominguez, Secretary of Finance, on fiscal policies and tax reforms to facilitate economic recovery from the pandemic OBG plus

Interview:Carlos Dominguez To what extent has the country’s fiscal strategy prepared it for the planned P6trn ($119.3bn) worth of borrowings in 2020-21 to address the crisis? CARLOS DOMINGUEZ: The core of our strategy has been to protect both lives and livelihoods. This, of course, comes with significant economic costs at a time when revenue collection is understandably lower because of the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Fortunately, when Covid-19 struck, the Philippines was financially…

Better together: Shinichi Kitaoka, President, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), on nurturing regional ties OBG plus

Interview:Shinichi Kitaoka How can the Philippines create more favourable conditions for Japanese investment? SHINICHI KITAOKA: Japan is a major source of foreign direct investment in the Philippines and was formerly the country’s second-largest trade partner. With its growing population and relatively inexpensive labour, Japanese companies view the Philippines as a promising investment destination. However, Japanese investors remain concerned about the Philippines’ security conditions,…

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Coffee in the Philippines: A Study on Price Elasticity of Supply

12 Pages Posted: 21 Jun 2022

Jennelyn Frajenal

World Citi Colleges

Date Written: May 31, 2022

Philippines is one of the fortunate countries that can generate viable coffee bean varieties. Local coffee output is declining, while market demand is growing. This research looks at the supply of coffee in both domestic and imported producers over a specified time period in order to develop a supply curve pattern that can be use as reference to forecast future demand. Quantitative research method and correlational design using secondary data from the Philippine Statistics Authority, as well as data from the internet and associated research was utilized. The findings based on proportionate method analysis shows that coffee supply favored to inelastic side for a certain period. The result of correlation analysis shows that there is a strong relationship between supply and price for the specific period covered.

Keywords: coffee, supply, inelastic, price increase, price elasticity

JEL Classification: B22

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Jennelyn Frajenal (Contact Author)

World citi colleges ( email ), do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, institutional & transition economics policy paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Economic & Financial Data of the Philippines

NATIONAL SUMMARY DATA PAGE

Frequency: Daily

Last Updated: June 21, 2024

Economic and Financial Data of the Philippines

The data shown in this page correspond to the data described on the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Dissemination Standards Bulletin Board (DSBB). For a fuller explanation of the DSBB and the statistical standards to which the Philippines has committed, please visit the DSBB Home Page .

[ Real Sector | Fiscal Sector | Financial Sector | External Sector | Population ]

Notes: 1. Data are not seasonally adjusted unless specified. 2. Data are final unless otherwise indicated.

| | |||||

| | |||||

| Gross Domestic Product (At constant 2018 prices) | In millions of pesos | Q1/24 | 5,189,658 | 5,884,513 | |

| Gross Domestic Product (At current prices) | In millions of pesos | Q1/24 | 6,109,970 | 7,050,113 | |

| Production Index 2018 base year | average index | Apr/24 | 99.3 | 99.8 | |

| Employment | In thousands of persons | Apr/24 | 48,355 | 49,153 | |

| Unemployment | In thousands of persons | Apr/24 | 2,041 | 2,000 | |

| Wages/ Earnings (Average Monthly Wage Rates in Selected Occupations) | monthly average, in pesos | 2022 | 18,423 | 16,486 | |

| Consumer Price Index 2018 base year | monthly average index | May/24 | 125.6 | 125.5 | |

| Producers Price Index 2018 base year | monthly average index | Apr/24 | 97.8 | 97.4 | |

| Revenues | In billions of pesos | 2017 | 2,473,132 | 2,195,914 | |

| Expenditures | In billions of pesos | 2017 | 2,823,769 | 2,549,336 | |

| Total Surplus (+) / Deficit (-) | In billions of pesos | 2017 | -350,637 | -353,422 | |

| Balance Surplus (+) / Deficit (-) of the Non Financial Public Enterprises | In billions of pesos | 2017 | |||

| Financing | In billions of pesos | 2017 | 663,929 | 220,938 | |

| External (Net) | In billions of pesos | 2017 | 27,569 | -24,113 | |

| Domestic (Net) | In billions of pesos | 2017 | 636,360 | 245,051 | |

| Bank | In billions of pesos | 2017 | |||

| Non-Bank | In billions of pesos | 2017 | |||

| Revenue | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 537,196 | 287,923 | |

| Expenditures | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 494,468 | 483,841 | |

| Balance Surplus (+) / Deficit (-) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 42,728 | -195,918 | |

| Financing | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | -42,728 | 195,918 | |

| External (Net) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | -32,260 | 44,201 | |

| Domestic (Net) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | -10,468 | 151,717 | |

| Bank | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 125,972 | 103,306 | |

| Non-Bank | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 3,286 | 1,694 | |

| Total | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 15,017,211 | 14,925,720 | |

| Domestic Debt | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 10,308,495 | 10,277,489 | |

| Short term | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 621,728 | 606,612 | |

| Medium term | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 2,251,603 | 2,250,129 | |

| Long term | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 7,435,164 | 7,420,748 | |

| Foreign Debt | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 4,708,716 | 4,648,231 | |

| Debt guaranteed by central government | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 356,057 | 346,041 | |

| Domestic | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 191,951 | 184,414 | |

| Foreign | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 164,106 | 161,627 | |

| Total Liquidity Aggregates (M4) and Liabilities Excluded from Broad Money | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 25,389,744 | 25,346,320 | |

| Currency and Transferable Deposits (M1) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 6,779,474 | 6,809,373 | |

| Currency Outside Depository Corporations and Deposits (M2) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 16,804,958 | 16,749,952 | |

| Broad-Money Liabilities: Domestic Liquidity (M3) | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 17,209,223 | 17,190,429 | |

| Net Claims on Central Government | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 5,045,028 | 5,180,825 | |

| Claims on Other Sectors | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 13,653,557 | 13,528,146 | |

| Net Foreign Assets | In millions of pesos | Apr/24 | 6,691,159 | 6,637,349 | |

| Net Foreign Assets | In millions of pesos | May/24 | 6,129,136 | 5,922,732 | |

| Domestic Claims | In millions of pesos | May/24 | 588,044 | 629,747 | |

| Reserve Money | In millions of pesos | May/24 | 3,851,807 | 3,700,310 | |

| Liabilities Other than Reserve Money | In millions of pesos | May/24 | 2,865,374 | 2,852,168 | |

| 91 - day Treasury bills | Weighted Average Interest Rate in percent per annum | 06/18/24 | 5.67 | 5.67 | |

| Fixed-Rate Treasury Bonds | Coupon Rate in percent per annum | ||||

| 04/22/14 | 1.625 | 8.500 | |||

| 05/28/24 | 6.347 | 6.007 | |||

| 10/03/17 | 4.000 | 3.375 | |||

| 02/13/24 | 6.156 | 6.073 | |||

| 02/07/23 | 6.125 | ||||

| 04/30/24 | 7.058 | 6.299 | |||

| 06/11/24 | 6.754 | 6.825 | |||

| 05/16/23 | 5.854 | 6.250 | |||

| 07/11/23 | 7.000 | ||||

| 06/19/24 | 6.781 | 6.624 | |||

| 03/14/23 | 6.167 | 6.197 | |||

| BSP Rediscount Rate | In percent per annum | May/24 | .. | .. | |

| BSP Policy Rates | In percent per annum | ||||

| 06/21/24 | 7.00 | 7.00 | |||

| 06/21/24 | 6.50 | 6.50 | |||

| Composite Index | February 28, 1990 = 1,022.045 | 06/21/24 | 6,158.48 | 6,344.56 | |

| Balance of Payments */ | In millions of US$ | May/24 | 1,997 | -639 | |

| Overall Balance of Payments | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 238 | 1,936 | |

| Current Account | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -1,749 | -520 | |

| Net Goods and Services | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -10,724 | -10,368 | |

| Net Goods | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -14,662 | -15,531 | |

| Exports of Goods | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 14,041 | 14,538 | |

| Imports of Goods | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 28,703 | 30,069 | |

| Net Services | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 3,938 | 5,163 | |

| Exports of Services | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 12,727 | 13,206 | |

| Imports of Services | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 8,790 | 8,043 | |

| Net Primary Income | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 1,368 | 1,573 | |

| Net Secondary Income | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 7,607 | 8,275 | |

| Net Capital Account | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 16 | 21 | |

| Financial Account | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -4,911 | -6,380 | |

| Net Direct Investments | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -2,257 | -1,416 | |

| Net Portfolio Investments | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -58 | -2,797 | |

| Net Financial Derivatives | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -61 | -13 | |

| Net Other Investments | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | -2,535 | -2,154 | |

| Change in Net Reserves | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 238 | 1,936 | |

| Gross International Reserves (Official Reserve Assets) | In millions of US$ | May/24 | 105,016 | 102,648 | |

| International Reserves and Foreign Currency Liquidity (Complete template) | In millions of US$ | Apr/24 | |||

| International Investment Position (IIP) | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | -51,317 | -47,464 | |

| Assets | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 241,444 | 231,555 | |

| Direct Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 71,858 | 69,371 | |

| Portfolio Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 36,740 | 36,807 | |

| Financial Derivatives | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 772 | 870 | |

| Other Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 28,320 | 26,392 | |

| Reserve Assets | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 103,753 | 98,116 | |

| Liabilities | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 292,760 | 279,019 | |

| Direct Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 122,571 | 118,180 | |

| Portfolio Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 85,756 | 81,104 | |

| Financial Derivatives | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 342 | 358 | |

| Other Investment | In millions of US$ | Q4/23 | 84,092 | 79,377 | |

| External Debt | In millions of US$ | Q1/24 | 128,692 | 125,394 | |

| Total Exports | In millions of US$ (F.O.B.) | Apr/24 | 6,215.92 | 6,130.67 | |

| Total Imports | In millions of US$ (F.O.B.) | Apr/24 | 10,976.86 | 9,572.80 | |

| Trade Balance | In millions of US$ (F.O.B) | Apr/24 | -4,760.94 | -3,442.12 | |

| Philippine Peso Per US Dollar Rate | weighted average interbank rates | 06/21/24 | 58.79 | 58.66 | |

| In millions | 05/01/2020 | 109,035,343 | |||

*/ Data are based on Balance of Payments and International Investments Position Manual, 6th Edition (BPM6)

**/ Includes P540 billion Short-term borrowing

1/ The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) is availing the flexibility option for this category.

2/ The periodicity of Employment and Unemployment data is every quarter particularly every January, April, July and October. Previous data refers to the previous round of the Labor Force Survey and is not seasonally adjusted. The reference period is the "past week" referring to the seven days preceding the date of visit of the enumerator. Starting April 2005, the new unemployment definition was adopted per NSCB Resolution No. 15 dated October 20, 2004, to wit: the unemployed include all persons who are 15 years old and above as of their last birthday and are reported as (1) without work; AND (2) currently available for work; AND (3) seeking work OR not seeking work due to valid reasons.

3/ The data refers to the average monthly wage rate across the selected occupations in the selected industries. The Philippines is using the "as relevant" flexibility for this data and will publish wage rates statistics with a periodicity of two years and a timeliness of 12 months.

4/ January - November 2005. The data include only the financing of the national government, and the 14 monitored non-financial government corporations (MNGGCs).

5/ Breakdown of domestic financing was revised due to the change in the basis used for the calculation

6/ Beginning 3 June 2016, the BSP shifted its monetary operations to an interest rate corridor (IRC) system. The repurchase (RP) window was replaced by the standing overnight lending facility (OLF). Meanwhile, the reverse repurchase (RRP) facility was modified to a purely overnight RRP.

7/ The Philippine Stock Exchange index (PSEi) is the main index of the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE). It is composed of the 30 largest and most active common stocks listed at the PSE. Daily updates are available at the PSE website.

8/ Daily updates and other convertible currencies with the BSP are available at the BSP website.

9/ Population Projection by Single-Year Interval (Medium Assumption). Previous data is for 2007.

10/ Scheduled release of CGO statistics as posted in the advance release calendar (ARC) will be postponed until further notice in view of the ongoing enhanced community quarantine in Luzon as a precautionary measure against the spread of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).

11/ On 17 March 2020, the BSP issued an announcement on the delay of release of statistics on DCS, CBS, International Reserves and Foreign Currency Liquidity, Reserves Template and IIP, which were committed in the 2020 ARC of SDDS and NSDP. In view of the ongoing enhanced community quarantine in Luzon as a precautionary measure against the spread of COVID-19, the scheduled release of these statistics will be postponed until further notice. The announcement of the BSP on the postponement of these statistics was posted at: http://www.bsp.gov.ph/statistics/schedules.asp .

| OWS | Occupational Wages Survey |

| OPSF | Oil Price Stabilization Fund |

| OLF | Leading Facility |

| RRP | Reverse Repurchase |

Sources of Data:

| BSP | Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas |

| BTr | Bureau of Treasury |

| DOF | Department of Finance |

| PSE | Philippine Stock Exchange |

| PSA | Philippine Statistics Authority |

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Research Paper - Inflation Rate in the Philippines

This research paper tackles the factors that affects the sudden rise of the inflation rate in the Philippines.

Related Papers

Benedict Chua

Journal of economics, finance and accounting studies

Herbert Peliglorio

Marajella Sebastian

THABANI NYONI

This research uses annual time series data on inflation rates in the Philippines from 1960 to 2017, to model and forecast inflation using ARIMA models. Diagnostic tests indicate that P is I(1). The study presents the ARIMA (1, 1, 3). The diagnostic tests further imply that the presented optimal ARIMA (1, 1, 3) model is stable and acceptable for predicting inflation in the Philippines. The results of the study apparently show that P will fall down from 5.6% in 2018 to approximately 0.3% in 2027. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is expected to continue implementing it inflation targeting policy framework since it proves to work well for the economy.

Prof. Dr. Valliappan Raju

Inflation is one of the most complex macroeconomic phenomena in industrialized economies. This study mainly focuses on examining inflation-related factors in Malaysia. Stepwise linear Regression analysis was applied via SPSS to investigate the significance of the inflation rate, exchange rate, money supply, interest rate and unemployment rate relationship by using time series from 1995 to 2019. The study aimed at determinants of factors that influence Malaysia's inflation. The analytical results found that the money supply and exchange rate have positive impact on the inflation, whereas the unemployment rate and interest rate have negative impact on the inflation. Moreover, The hypothetical results are supported to the exchange rate and interest rate. The remaining other two independent variables do not support the hypotheses. The study suggests that Inflation, pushed up by money growth rate as well as Ringgit depreciation and higher interest rates, has adversely impacted produc...

Faiznazif Ainali

Comparison between Civilian government and Military Administrations Economic Policy Analysis. The purpose of this paper is to make analysis of inflation rate during military regime by comparing it with the civilian regime in Pakistan. The paper will also focus on the major events which were the main causes of creating inflation and the remedies took by the than governments to mitigate the effect on masses and policies made to counter the inflation.

International Journal of Research Studies in Education

Rose Capulla

sharry medellin

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Veronica Bayangos

Mc Reynald II S Banderlipe

HOD Business Administration

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

Mohd Husnin Mat Yusof

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE)

Allemar Jhone Delima

DR AMIR IMRAN ZAINODDIN

International Journal of Research

Edupedia Publications

Leonard Charumbira

Journal of Science and Science Education

Henry Wattimanela

Bibek Khadgi

Patty Salamanca

Maria Tavita Lumintac

Media Ekonomi dan Manajemen

melenia napitupulu

Nancy Nopeline

European journal of computer science and information technology

Romie Mabborang

Journal of Development Economics

PRAGATI : Journal of Indian Economy

ARJUN PANGANNAVAR

Mauricio Amaya

The Pakistan Development Review

Wira Kusuma

Rezzy Eko Caraka , WAWAN SUGIYARTO

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Projection of the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Welfare of Remittance-Dependent Households in the Philippines

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 25 September 2020

- Volume 5 , pages 97–110, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Enerelt Murakami 1 ,

- Satoshi Shimizutani 1 &

- Eiji Yamada 1

76k Accesses

25 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is inevitably affecting remittance-dependent countries through economic downturns in the destination countries, and restrictions on travel and sending remittances to their home country. We explore the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of remittance-dependent households using a dataset collected in the Philippines prior to the outbreak. First, we confirm that remittances are associated with welfare of households, particularly for those whose head is male or lower educated. Then, we use the revision of the 2020 GDP projections before and after the COVID-19 crisis to gauge potential impacts on households caused by the pandemic. We find that remittance inflow will decrease by 14–20% and household spending per capita will decline by 1–2% (food expenditure per capita by 2–3%) in one year as a result of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessing the Impact of Covid-19 in Mozambique in 2020

The Role of Automatic Stabilizers and Emergency Tax–Benefit Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Ecuador

The Impact of the Pandemic on Social Vulnerabilities in India

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) is a devastating pandemic with global effects and is undoubtedly one of the largest macro-level shocks to the world economy, as evidenced by the already ominous economic indicators. While the adverse effects on the economy are revealing at the macro-level, the impact of the pandemic is likely to be heterogenous across countries and individuals. Moreover, the adverse effects may not be confined to the domestic markets but may be transmitted internationally, particularly in the case of developing countries.

This paper explores the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of households in a remittance-dependent country, which is likely to be severely exposed to external shocks. The pandemic is expected to substantially reduce the amount of remittances that migrants from developing countries can send home. The World Bank estimates that global remittances will decline sharply by about 20% in 2020, the sharpest in recent history, and that remittances to low and middle-income countries are projected to fall by 19.7%. Footnote 1 Many migrants may lose their jobs or be forced to accept lower wages due to lockdowns or oil price crashes in their destination countries (IOM, 2020 ); they may not be able to send remittances due to stringent movement restrictions and exclusion of money transfer service providers from the list of “essential services” (World Bank, 2020b ). Furthermore, many intended migrants who had been preparing for their departure in the near future will be forced to change their livelihood plans for the coming years. In 2019, 80% of the world’s total remittances flowed to low-and-middle-income countries (World Bank, 2020c ); therefore, the negative impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak may be more serious in developing countries whose citizens heavily depend on remittances from migrant family members.

The Philippines is a sensible case to study for several reasons. First, the country is one of the largest source countries for migrants in the world and is one of the most remittance-dependent, ranked fourth in terms of remittance inflow (Yang, 2011 ). The proportion of remittances relative to the country’s GDP was close to 10% (World Bank, 2020a , b , c and d ). Moreover, some of the countries that host Filipino migrants are the most seriously affected by lockdowns and oil price crashes. The number of overseas Filipino workers was estimated at 2.2 million in 2016 with the top destinations being Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Hong Kong, and Singapore, which combined accounts for two-thirds of total destinations (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2017 ). The diversity of destinations implies that the impact of COVID-19 may be heterogenous even among Filipino migrants. The Philippine Government has reacted by providing cash relief to overseas migrant workers and their families who are suffering hardship. Footnote 2

In this paper, we use a household-level dataset which was collected in in the Philippines before the COVID-19 outbreak. We first pin down the empirical relationship between remittance income and welfare of households by two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumenting remittance income by a macroeconomic variable exogenous to households. We then project the potential impact of the COVID-19 shock in destination countries on the welfare of remittance-dependent households by utilizing the revision of the 2020 GDP forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which were made before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Taking the difference between the predicted outcomes of with- and no-COVID projections provides us with the potential shocks on the remittances and other economic welfare outcomes of remittance-receiving households. Our projections show that remittance inflow will decrease by 14–20% and household spending per capita will decline by 1–2% in one year, as a result of the pandemic. Furthermore, the negative impact can substantially vary across different type of households.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the dataset used in this study. Section 3 examines the effect of macroeconomic shocks on household living standards prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Section 4 performs several projections to gauge the impact of the pandemic on household welfare. Section 5 concludes.

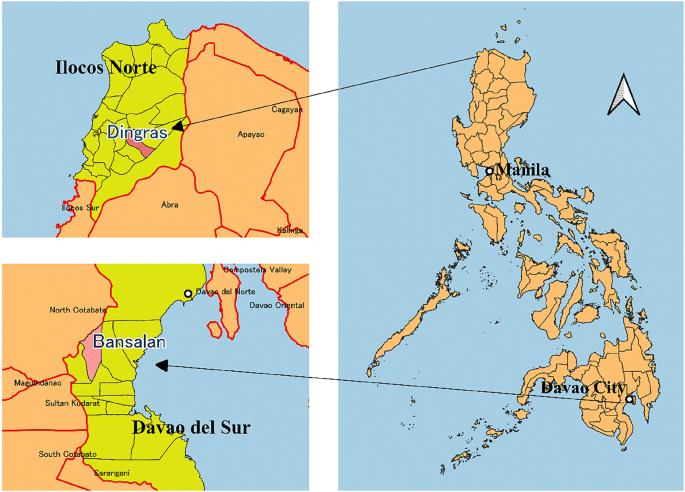

Data Description

This study utilizes the data from “Survey on Remittances and Household Finances in the Philippines,” conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in two rural municipalities in the country: Dingras, Ilocos Norte located in the Northern Luzon Island and Bansalan, Davao del Sur located in the southern island of Mindanao (Fig. 1 ). Footnote 3 The survey is constituted of two rounds of data collection. The first-round survey was conducted between August and September 2016. The sample size was 834. The second-round survey was implemented between June and August 2017. The sample size was 668. Footnote 4 The target sample size at the first-round was 200 overseas migrant households and 200 non-overseas migrant households in each municipality, which were randomly selected in each area. A migrant household is defined as a household which had at least one member who permanently resides or used to reside in this household but is now currently working or living overseas. Given that the stock of overseas Filipino was about ten million in 2013 (Commission on Filipinos Overseas, 2013 ), migrant households were oversampled. A total of 2429 overseas migrant households and 5172 non-overseas migrant households were listed in Dingras while a total of 563 overseas migrant households and 19,797 non-overseas migrant households were listed in Bansalan. Next, stratified random sampling was carried out for each municipality. The barangays within each municipality served as strata and the sample households were randomly selected within each barangay. Footnote 5 The sample of 200 overseas migrant households was proportionately distributed among the barangays. Once the number of overseas migrant households was allocated among the barangays, an equal number of non-overseas migrant households was selected within each barangay.

Location maps of two municipalities. Source: Generated by the authors based on GDAL’s administrative boundary shapefiles

Table 1 reports the summary statistics of the variables. Footnote 6 In order to investigate the impact of the crisis on remittance-dependent households, we limit our sample to only those households that reported receiving remittances in at least one survey rounds. Columns (1)–(3) report the summary statistics for those remittance-receiving households and Columns (4)–(6) show those using all the households in our sample. Remittance-receiving households spend more both in terms of food and non-food items. They also make more savings and less loan payment on average. They earn less from agricultural and nonagricultural work and domestic sources. “ ECON ” is a weighted average of destination and home countries per capita GDP, and is explained in more detail in the next section. On average, heads of the households are 54 years old, and households are made up of 5 or more members, which includes overseas migrants. The education level of household heads is diverse. More than one-third completed only elementary school or have a high school degree; a quarter graduated college or higher education. The most common occupation among household heads is agriculture. Both the variables of education and those of occupation are binary (using non-educated or non-working heads of households as the reference). Footnote 7

Empirical Analysis

We aim to measure the impact of the macroeconomic conditions in the destination countries on the outcomes relating to household living standards through remittances. There is a concern about the endogeneity issue since household welfare outcomes are likely to be affected by remittances and vice versa. It is well known that addressing endogeneity is one of the most crucial elements of estimation relating to remittances and the effects (McKenzie et al. ( 2010 )). This is an important issue for our estimation by pooling observations rather than using panel fixed effects to remove latent characteristics of the sample households. In the context of the Philippines, remittances are often motivated to finance non-food consumption in the Philippines, which makes the OLS estimate on non-food consumption biased (less problematic for food consumption). This may be the case for flow of assets too. Moreover, remittances are substitute for domestic income but a third factor like endowment may make the estimate obscure since high endowment migrants holds higher ability to earn domestically.

Thus, we employ a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation using an index of the macroeconomic performance of the destination countries as an instrumental variable. Footnote 8 We construct the “economic performance ( ECON )” variable by taking the weighted average per capita GDP of the country of residence of each household member, including overseas migrants. More specifically, the “ ECON ” variable is constructed as:

Here, \( \mathcal{K}(i) \) refers to the set of countries where the members of household i live, g kt is the log GDP per capita in country k in t (2016 or 2017), and n kit is the number of household i ’s adult member who live in country k . Footnote 9

We assume that GDP per capita is exogenous to the amount of remittances in each household. Our assumption means that ECON picks up supply-side shocks on migrants’ remittances, which reflects labor market conditions that they are exposed to in the destination countries. We acknowledge the possibility that our instrumental variable can also be correlated with demand-side shocks that would cause biases of the coefficients. Specifically, it might be the case that household’s latent characteristics and the choice of destination are closely associated; high endowment migrants are also likely to choose a high-income destination country, which could result in overestimation of the coefficient on the remittances. We also notice that it might be hard to establish exclusion restriction here since changes in economic performance outside the Philippines will have direct effect on household welfare in the country not through remittances but trade and financial channels affecting wage and employment prospects.

In the estimation, we use a level specification by pooling the observations at the first and second rounds, rather than a fixed effect model to remove unobserved heterogeneity. The main reason is to utilize a larger variation in the amount of remittances, the main variable, to obtain stable estimation results. Since the survey interval is short (less than one year), we see little change in the amount of remittances during the survey period. Instead of utilizing a variation between two periods in the same households, we pooled the data at both baseline and endline. The advantage is we can obtain a larger variation between households while the disadvantage is to not able to use a fixed effect model but the cost is abbreviated to some extent if we use a valid instrument. Footnote 10

In the first stage, we regress the amount of remittances on the logarithm of the “ ECON ” variable and other covariates.

where i indexes households, and t refers to the survey round with 0 indicating 2016 and 1 indicating 2017. REMITTANCE it is calculated as the monthly average either over the past 12 months for the first-round or for the period since the first-round visit in the case of the second round. Footnote 11 \( \mathbbm{X} \) is a vector of household characteristics that were reported in Table 1 . We also include barangay fixed effect ( barangay i ) and survey round fixed effect ( λ t ). Lastly, ϵ it is a well-behaved error term. This specification exploits cross-country variations of GDP per capita to explain variations in the amount of remittance across households, rather than exploiting within-household variations of remittances between the two survey rounds.

Column (1) of Table 2 shows the results of the first stage regression. We performed a weak IV test and confirmed that F-test statistic for weak IV is 137.48 with p value of 0.00. The coefficient on “ ECON ” is positive and significant and indicates that a 1% increase in “ ECON ” leads to a 1.67% increase in income from remittances per capita; this implies that a significant economic recession in the destination countries will lead to a substantial drop in remittances.

Next, we use the estimated dependent variable of remittances at the second stage regression.

The dependent variables Y it are a logarithm of (1) average monthly household expenditure per capita, (2) average monthly household food expenditure per capita, (3) average monthly household non-food expenditure, (4) average monthly new savings deposits per capita, (5) average monthly loan repayments per capita, (6) agricultural income, (7) non-agricultural income and (8) average monthly household incomes from domestic sources. Footnote 12 The main explanatory variable \( {\overline{REMITTANCE}}_{it} \) is the log average monthly overseas remittance income per capita, which is projected by the first stage estimates.

Columns (2)–(9) of Table 2 convey the second stage results. We will focus on the coefficient on the logarithm of remittance income per capita, the main explanatory variable. The coefficient on the remittance income is positive and significant for household spending per capita and the size is 0.084 (Column (2)), showing that a 1% increase in remittance income is associated with a 0.08% increase in per capita household spending. When we split household expenditure into food and non-food spending, the coefficient is significant and larger for the former (Columns (3) and (4)), showing that a 1% increase in remittance income is associated with a 0.14% increase in per capita food spending. The coefficient is positive for new savings and negative for loan repayments, but it is not significant (Columns (5) and (6)). While the coefficient on agricultural income is not significant, it is negative and significant for non-agricultural income (Columns (7) and (8)). Income from domestic sources is negatively and significantly associated with income from remittances (Column (9)). Both coefficients on non-agricultural income and domestic source income are minus 0.22 and 0.23, showing that one fifth of a change in remittance income is abbreviated by those income under the market situation in 2016 and 2017.

Table 3 reports the estimation result by splitting the sample by type of head of household. We run the regression by subgroups to address heterogenous effect of remittances on welfare of households by sex, age, and educational attainment of the head of household. First, we see that the coefficients on total, food and non-food spending are positive and significant for male headed households while the coefficient is positive and significant, and the size is larger on food expenditure for female headed households. A larger remittance income is negatively and significantly associated with non-agricultural income and domestic sourced income for male-headed households and with agricultural income for female-headed households. Second, if we divided the sample by whether the head of household’s age is greater than 52 years old, the median of the head’s age in our sample, the coefficient on spending is only significant for food expenditure by households whose head is older and remittance income is negatively associated with agricultural income and domestic income for those households. Third, when we divide the sample by the head of household’s educational attainment, the coefficients on household spending are positive and significant for households whose head completed less than secondary school.

In summary, the estimation results confirm that a decline in remittances discourages household spending per capita and is partly abbreviated by non-agricultural income and domestic income.

Projections

To quantify the scale of the economic shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on the relevant countries, we use the per capita GDP predictions available for each country in 2020 from growth forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ‘s “World Economic Outlook” published in October 2019 (IMF 2019 ) and June 2020 (IMF 2020 ), and the World Bank (WB)‘s “Global Economic Prospects” published in January (World Bank 2020a ) and June 2020 (World Bank 2020d ). Footnote 13 The IMF’s outlook from October 2019 and the WB’s outlook from January 2020 can be seen as a “no-COVID” forecast, which helps us to construct the hypothetical “ ECON ” variable, where a COVID-19 pandemic had not taken place. Conversely, the revised IMF’s outlook from June 2020 and the WB’s outlook from June 2020 can be used to construct the “with-COVID” economic scenarios that will affect remittances from migrant workers. The “with-COVID” projections contain two cases in the “World Economic Outlook” and three cases in the “Global Economic Prospects”. Details of the scenarios are given in Table 4 . We implicitly assume that the change in the prediction of GDP for 2020 in the two different timings is entirely attributed to the pandemic.

We compute the predicted values by plugging the hypothetical ECON variables, constructed using each of the GDP per capita forecasts for remittance-receiving households, into our 2SLS estimates that shows statistical significance in Table 2 . We then compare the mean predicted values of with-COVID scenarios with that of no-COVID scenario in each growth outlook for the various outcome variables in each projection scenario. We do not consider the compensating effect of domestic income on the decline of remittances because the Philippine economy is also seriously affected by the pandemic.

Table 4 shows the potential impacts of the COVID-19 as percentage changes in the predicted remittances, expenditure and income under the with-COVID scenarios against the no-COVID scenario as per each growth outlook. The negative impact of the pandemic on remittances is serious, with a decline of as high as 14–20%, which is comparable with the World Bank’s forecast for decline in remittances in the East Asia and Pacific region in 2020. Moreover, our estimate is close the recently published ADB projection (Kikkawa et al. 2020 ) showing that the remittance to the Philippines will decline by 20.2%. The adverse effects are more pronounced under the “with-COVID scenario two” by the World Bank, while “with-COVID scenario one” by the IMF and “with-COVID scenario one” by the World Bank are closer in magnitude. The household spending per capita would decline by 1–2% in each scenario. Of the total spending, food expenditure has the highest drop by 2–3%. Thus, our predictions show that remittance inflow will decrease by 14–20% and household spending per capita will decline by 1–2% (food spending by 2–3%) in the space of one year during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reminding our subsample analysis in the previous section, households with male or low educated head will further decrease per capital expenditure while female headed households will see more substantial drop in food consumption due to the decline in remittances income.

Those projections must be understood in conjunction with several reservations. First, we use household data from heavily remittance-dependent regions that do not necessarily conform to the average in the Philippines. Second, our projection captures a short-run (during the year 2020) effect of the pandemic on household welfare but the negative impact would be more serious over a longer term. Third, we summarized all aspects of the virus outbreak into a change in per capita GDP. We may need to take a more nuanced approach using data on international restrictions on travels and remittance transactions. Fourth, we boldly sum up complex processes within a serial decision-making process carried out by households in relation to migration and remittances into the “amount of remittance”. Disentangling the effect of the pandemic over the migration process is an important agenda for future research. Fifth and lastly, we implicitly assume that an increase in remittances will have the same magnitude on household-level outcomes as will decreases in remittances associated with the pandemic. The symmetry assumption that the sensitivity of household-level outcomes remains the same during the pandemic should be examined by the actual post-pandemic data.

Using a household-level dataset in heavy migrant-dependent regions before the outbreak in the Philippines and the 2020 GDP projections made by the IMF and the WB, we evaluated the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our projection shows that remittance inflow will decrease by 14–20% and household spending per capita will decline by 1–2% (food expenditure per capita by 2–3%) in one year as a result of the pandemic.

The pandemic is still ongoing. Future research should use the actual data in migrant-sending countries after the COVID-19 outbreak to quantify the adverse effects on household living standards. While it is not easy to conduct a survey during the pandemic, this line of research will be very informative for future policy responses.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/22/world-bank-predicts-sharpest-decline-of-remittances-in-recent-history . The decline is projected to be 13% in the East Asia and Pacific region.

https://www.owwa.gov.ph/index.php/news/regional/85-1-600-active-owwa-members-in-davao-del-sur-receive-cash-relief-assistance-from-owwa-xi .

These municipalities were selected in order to oversample households with overseas migrants and provided the necessary collaboration with us to implement the survey and information for listing.

While we chose only two municipalities in the survey due to resource limitation, our study area covers regions with different characteristics in terms of dependency on migration and remittances. 32.3% of the households in Dingras has at least one migrant while only 2.8% in Bansalan (10.6% of the total samples of two municipalities). According to 2018 National Migration Survey (PSA and UPPI 2019 ), 8.9% of the households in the Ilocos Region (where Dingras belongs) have at least one OFW (Overseas Filipino Workers) in the past 12 months and 5.7% in the Davao region where Bansalan is located (6.4% nationwide). Although our sampling design does not generate nationally representative dataset, respondents in our sample are comparable to the 2018 National Migration Survey (NMS) of the Philippines (PSA and UPPI 2019 ). We compare the distributions of age and educational attainments between two surveys, and find that our sample individuals are slightly older and proportion of college attendees or graduates is higher. The detail is reported in Appendix Table 1.

The barangay is the smallest political unit and a subdivision of a city or municipality.

Per capita expenditure is systematically larger and the ages of the heads of household is higher for the attrition households at the first-round.

While the job of a seamen makes up a large part of the migrant job market, our sample does not contain many of these migrants.

In order to gauge the direction of the bias stemming from OLS estimates, we checked to compare the regression outcomes with non-instrumented as well as instrumented remittance values. When we compare those results, we see that the coefficient loses significance in nonfood consumption and the coefficient gains absolute size and significance in non-agricultural and total income from domestic sources. The OLS results are available upon request.

We share the spirit with Ratha and Shaw ( 2007 ) that used weighted value of destination GDP in cross-country estimating remittances inflow.

In addition, we use the sub-sample of households with migrants only. We believe that the most fundamental selection-bias in the decision of whether or not to migrate is well-addressed by this sub-sample strategy.

The qualitative results are not changed if the average over the past 12 months is used for the second round.

The denominator of all “per capita” variables from the household survey is the number of household members excluding migrating members.

The initial projection by the IMF after the pandemic was released in April 2020 and updated in June 2020.

Commission on Filipinos Overseas, Department of Foreign Affairs, and Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. (2013). Stock Estimate of Overseas Filipinos. Retrieved from https://cfo.gov.ph/yearly-stock-estimation-of-overseas-filipinos

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2019). World Economic Outlook, October 2019 Global Manufacturing Downturn, Rising Trade Barriers. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2019/10/01/world-economic-outlook-october-2019

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2020). COVID-19 Analytical Snapshot #16: International Remittances . Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19_analytical_snapshot_16_-_international_remittances.pdf

Kikkawa, Aiko, James Villafuerte, Raymond Gaspar and Badri Narayanan (2020). “COVID-19 Impact on International Migration, Remittances, and Recipient Households in Developing Asia,” ADB BRIEFS , No.148. ADB Manila

McKenzie D, Gibson J, Stillman S (2010) How important is selection? Experimental vs. non-experimental measures of the income gain from migration. J Eur Econ Assoc 8(4):913–945

Article Google Scholar

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2017). Survey on Overseas Filipinos 2016: A Report on the Overseas Filipino Workers. Retrieved from https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2016%20Survey%20on%20Overseas%20Filipinos.pdf

Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) and University of the Philippines Population Institute (UPPI) (2019) 2018 National Migration Survey. PSA and UPPI, Quezon City, Philippines Retrieved from https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2018%20NMS%20Final%20Report.pdf

Google Scholar

Ratha, Dilip and William Shaw (2007). “South-South Migration and Remittances,” World Bank Working Paper 102 . Washington D.C .

World Bank, (2020a). Global Economic Prospects , January 2020 . Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33044?show=full

World Bank. (2020b). Remittances in times of the coronavirus-keep them flowing . Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/remittances-times-coronavirus-keep-them-flowing

World Bank. (2020c). Remittances Data. Retrieved from https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

World Bank. (2020d). Global Economic Prospects , June 2020 Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33748

Yang D (2011) Migrant Remittances. J Econ Perspect 25(3):129–152

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the project “Study on Remittances and Household Finances in the Philippines and Tajikistan” carried out by JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development. A previous version was featured in Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers . We would like to thank Alvin P. Ang, Jeremaiah M. Opiniano, and Akira Murata for their leadership and technical contribution during the data collection in the Philippines. We also thank Yasuyuki Sawada, Hiroyuki Yamada, Aiko Kikkawa Takenaka, Akio Hosono, Etsuko Masuko, Hiromichi Muraoka, Megumi Muto, Ryosuke Nakata, and Shimpei Taguchi for their constructive comments and Pragya Gupta for her excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are our own and do not represent the official positions of either the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development or JICA.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development, 10-5 Ichigaya Honmuracho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 162-8433, Japan

Enerelt Murakami, Satoshi Shimizutani & Eiji Yamada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Satoshi Shimizutani .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Economics of COVID-19

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Murakami, E., Shimizutani, S. & Yamada, E. Projection of the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Welfare of Remittance-Dependent Households in the Philippines. EconDisCliCha 5 , 97–110 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00078-9

Download citation

Received : 20 July 2020

Accepted : 09 September 2020

Published : 25 September 2020

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00078-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Philippines

- Household welfare

JEL Classification Codes

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Economic Impact, Contribution, and Challenges of Micro Business Enterprises to the Local Development

- Joyfe G. Quingco Carlos Hilado Memorial State College–Fortune Towne Campus, Bacolod City, Philippines https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6472-6463

- Carmenda S. Leonoras University of Negros Occidental-Recoletos, Bacolod City, Philippines

Micro Business Enterprises (MBEs) is the lifeblood for economic development. Using a descriptive quantitative research design, the study aimed to investigate the impact of MBEs to economic development. As to impact, in general, it was of a moderate extent. Among the indicators, technology has the highest mean interpreted to a high extent, while infrastructure development scored the lowest mean score, which reflected a moderate degree. The study further delved into the economic contribution and challenges encountered by MBEs. The findings basically implied that MBEs were rooted in the entrepreneur's commitment to do business that promotes progress and development to the local economy.

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Journal Information

Aim and Scope

Editorial Team

Submission Policy

Responsibilities of Authors

Guide to Authors

Peer Review Process

Guide to Referees

Criteria for Acceptance and Rejection

Publication Ethics and Malpractice

Policy on Handling Complaints

Policy on Retraction

Policy on Conflicts of Interest

Policy on Use of Human Subjects in Research

Policy on Digital Preservation

Open Access and Copyright Policy

Privacy Statement

Publication Frequency

Sources of Support

Journal History

Make Submission

ISSN 2704-288X (Electronic)

ISSN 2672-3107(Print)

Philippine Social Science Journal

Current Issue

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Philippines' economy was expected to increase gradually to 362.24 billion US dollars by 2020. By 2026, the Philippines' GDP should be $590.86. Philippines' real GDP would fall 9.5% by 2020.

Considering that GDP is one of the main indicators that influence the economic growth of a country, there are certain factors that. affect its increase or decrease. Some of the known factors are ...

observations about price movements in the Philippines: 1. Prices in the Philippines, on average, changed in about 75.6% of the months in the sample period (ie price increases and decreases). Between 1994 and M9 2019 (ie 308 months), there were 200 months when prices increased and 29 months when they decreased.

Abstract. At the start of its term, the Duterte administration reaped the benefits of the Philippines' momentum of economic growth and poverty reduction; the country's GDP continued to expand at above six percent during the 2016 to 2019 period while poverty incidence significantly declined to 16 percent in 2018.

Bank Officer V, Department of Economic Research, BSP. 3. Bank Officer V, Department of Economic Research, BSP. Price-setting Behaviour and Inflation Dynamics in ... dynamics in the Philippines, as the public have now become more forward-looking in their decision-making process. The ability of a central bank to anchor the public's inflation ...

202108 Growth During the Time of Covid19 by Renato E. Reside, Jr. ; 202107 Martial law and the Philippine economy by Emmanuel S. de Dios & Maria Socorro Gochoco-Bautista & Jan Carlo Punongbayan ; 202106 Virtues and institutions in Smith: a reconstruction by Emmanuel S. de Dios ; 202105 Accelerating Resilience and Climate Change Adaptation: Strengthening the Philippines' Contribution to Limit ...

As a response to the economic crisis brought by COVID-19, the Philippine government has started to implement its Social Amelioration Program (SAP) which aims to provide a monthly cash aid worth ...

The data used were acquired from the Philippine Statistics Authority, National Statistics Office, and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. Following the Box-Jenkins method, the formulated model for forecasting the unemployment rate is SARIMA (6, 1, 5) × (0, 1, 1) 4 with a coefficient of determination of 0.79. The actual values are 99 percent identical ...

2002), Complementing use a quantitative model and micro-level data to disentangle the effects of the land reform legislation from the degree of imple-mentation, (ii) the functioning of the land market, and (iii) other changes occurring in the economy alongside the reform.

The Philippines is one of the fastest-growing economies of the past decade, averaging 6.4% growth per year over 2010-19. Indeed, an expanding and youthful population, combined with reforms and an ambitious infrastructure programme, have made it an enticing investment destination. Nevertheless, as is often the case in emerging markets, challenges regarding inequality - particularly the

agricultural productivity using a quantitative model and micro-level data before and after the reform. We study the 1988 land reform in the Philippines, known as the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP). CARP was an extensive land redistribution program that imposed a restrictive

THE PHILIPPINE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS Volume LIV No. 2 December 2017 June and December 2019 THE PHILIPPINE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS Volume LIV No. 2 December 2017 Volume LVI Nos. 1 and 2Volume LIV No. 2Volume LIV No. 2 ISSN 1655-1516 December 2017 A joint publication of the University of the Philippines School of Economics and the Philippine Economic ...

International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research Vol. 2, No. 01; 2018 ISSN: 2456-7760 www.ijebmr.com Page 61 MICROFINANCE IN THE PHILIPPINES: A TOOL FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, OR PERPETUAL DEBT? EVIDENCE OF ITS SUCCESS AND CHALLENGES IN THE PROVINCE Bryan W. Rich Research Fellow Palawan State University, Philippines Abstract

Abstract. Philippines is one of the fortunate countries that can generate viable coffee bean varieties. Local coffee output is declining, while market demand is growing. This research looks at the supply of coffee in both domestic and imported producers over a specified time period in order to develop a supply curve pattern that can be use as ...

Economic and Financial Data of the Philippines. ... The Philippines is using the "as relevant" flexibility for this data and will publish wage rates statistics with a periodicity of two years and a timeliness of 12 months. 4/ January - November 2005. The data include only the financing of the national government, and the 14 monitored non ...

This research uses annual time series data on inflation rates in the Philippines from 1960 to 2017, to model and forecast inflation using ARIMA models. Diagnostic tests indicate that P is I (1). The study presents the ARIMA (1, 1, 3). The diagnostic tests further imply that the presented optimal ARIMA (1, 1, 3) model is stable and acceptable ...

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is inevitably affecting remittance-dependent countries through economic downturns in the destination countries, and restrictions on travel and sending remittances to their home country. We explore the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the welfare of remittance-dependent households using a dataset collected in the Philippines prior to the ...

An Analysis on the Economic Factors Affecting the Unemployment Rate in the Philippines from 1993-2018 Caligagan, Angelica Anne M. 1 , Ching, Roby Rafael O. 2 and Suin, Kristine April 3

Micro Business Enterprises (MBEs) is the lifeblood for economic development. Using a descriptive quantitative research design, the study aimed to investigate the impact of MBEs to economic development. As to impact, in general, it was of a moderate extent. Among the indicators, technology has the highest mean interpreted to a high extent, while infrastructure development scored the lowest mean ...

COVID-19 dynamics in the Philippines are driven by age, contact structure, mobility, and MHS adherence. Continued compliance with low-cost MHS should help the Philippines control the epidemic until vaccines are widely distributed, but disease resurgence may be occurring due to a combination of low population immunity and detection rates and new variants of concern.

Offered by the School of International Service , the International Economic Relations: Quantitative Methods (MA) offers advanced training in econometrics and quantitative methods and gives students an in-depth understanding of the economic, political, and social forces that shape relations among countries and their governments within the global economy, as well as of the private and official ...

She is also the macroeconomics and fiscal management expert behind the Growth and Productivity Report and the Philippines Economic Update, which reviews salient socioeconomic issues and provides growth forecasts twice a year. ... Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, Management Science, Operations Research, Review of Finance), 21 in ABS ...

Practical Research II Final - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. This document outlines a research study on the perceptions of Grade 12 students at University of Luzon regarding inflation rates in the Philippines. The study aims to understand students' perceptions as well as gather recommendations on how to decrease inflation.

Flaim (1990) explained the growing population Journal of International Business, Economics andEntrepreneurship e-ISSN :2550-1429 Volume 4 (1) June 2019 in the United States during the 60s to 80s ...

The country's benchmark CSI 300 index, which tracks China's top 300 stocks, has risen 8 per cent over the same time period, according to research provider Simu Paipai.

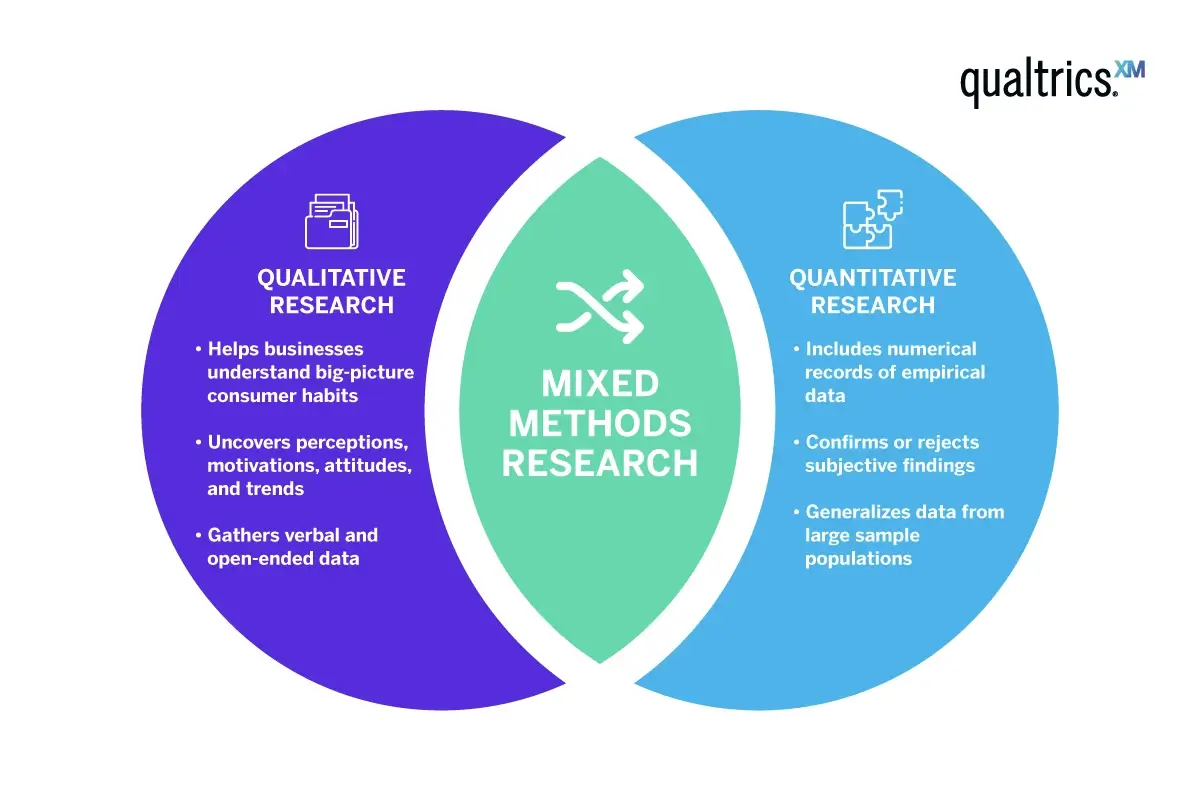

Quantitative research gathers information that can be counted, measured, or rated numerically - AKA quantitative data. Scores, measurements, financial records, temperature charts and receipts or ledgers are all examples of quantitative data. ... finance and economics. It's easy to 'crunch the numbers' of quantitative data and produce ...

The research method followed a quantitative design and the 61-item survey included basic demographic questions, three validation check questions, and three scales: vanity, materialism, and general ...

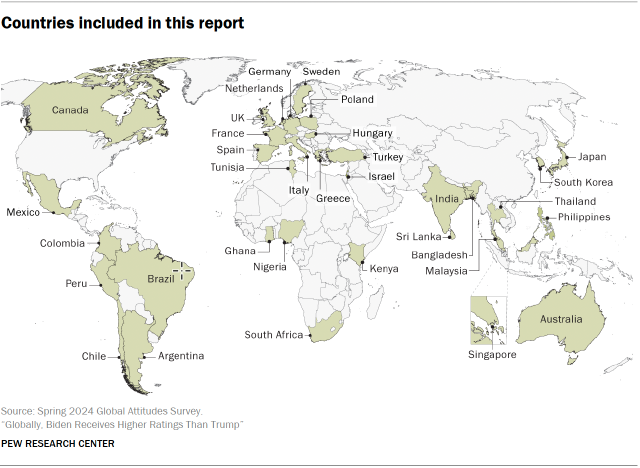

Pew Research Center has polled the Palestinian territories in previous years, but we were unable to conduct fieldwork in Gaza or the West Bank for our Spring 2024 survey due to security concerns. We are actively investigating possibilities for both qualitative and quantitative research on public opinion in the region and hope to be able to ...