Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages

Introduction, the essence of distance learning, advantages and disadvantages of distance learning, works cited.

Computer and information technologies have significantly affected all spheres of human life. These technologies have also changed the field of education, since the improvement and development of this direction is one of the main mechanisms that make up the public life of the United States. Thus, a new form of distance learning has appeared in modern human life, which, along with the traditional form, has taken an important place in our society. This kind of training allows not only to study but also to improve the qualification level of its users.

The research paper offered to the reader is devoted to the concept of distance learning, as well as its advantages and disadvantages. The question of the advantages and disadvantages of distance learning has been in the focus of research attention especially against the background of a general quarantine, which justifies the actuality of this topic. To facilitate the preparation of this final project, the author formulates the problem in several forms of proposals, namely:

- Analysis of the phenomenon of distance learning.

- Analysis of the pros and cons of distance learning.

This study focuses on analyzing the pros and cons of distance learning, as well as predicting its further application. The results of this study are of practical use, because they will be of interest to students and teachers who are choosing whether to switch to remote learning.

Sawsan Abuhammad, the Assistant Professor in Jordan University of Science and Technology, in his article “Barriers to distance learning during the COVID-19 outbreak: A qualitative review from parents’ perspective” (2020) states the following. The author claims that many parents have faced serious problems in the process of distance learning of their children. The author believes that the barriers that arose among the parents were of a personal, financial and technical nature. The author also states that these barriers need to be eliminated with the help of some changes, including through communication with other parents and students.

The author used the social network Facebook to recognize local groups, as well as keywords including distance learning, parents and Jordan. The author used a general qualitative method and analyzed all the messages and posts of parents related to this topic. This article was written by the author in order to describe and clarify the ideas of parents about the obstacles to distance learning during the coronavirus crisis (Abuhammad). The main audience of this article is parents, as well as persons representing the government and making decisions regarding distance learning. Thus, in the process of distance learning, many parents have various barriers that need to be overcome. We intend to use this source to demonstrate the problems and difficulties of distance learning.

Živko Bojović, Petar D. Bojović, Dušan Vujošević and Jelena Šuh, in their article “Education in times of crisis: Rapid transition to distance learning” (2020), state the following. They claim that the pandemic crisis has a negative effect on the standard of living and education. The authors believe that violation can pose a serious threat, and therefore a working model is needed that will allow switching from the traditional form of training to distance learning quickly and painlessly. The authors also argue that distance learning is acceptable on a long-term basis, if it is implemented correctly.

The authors of this article used a modeling method that allowed them to determine organizational and technical solutions for maintaining the quality of teaching. In addition, the authors used the method of comparative analysis of the survey data of students and teachers. The article was written by the authors in order to facilitate the transition from traditional learning to distance learning against the background of the pandemic and quarantine (Bojović et al.). The model developed by them has many advantages and thoughtful solutions. The main audience of this article is teachers and other representatives of educational institutions who face the difficult task of implementing distance learning. We intend to use this article to better understand the essence of distance learning, as well as its advantages.

Tim Surma and Paul A. Kirschner in their article, “Technology enhanced distance learning should not forget how learning happens” (2020), state the following. They believe that the traditional type of learning is under threat due to the accelerated process of adapting the traditional learning process to a new, remote one. They argue that modern technologies are both a danger and a chance for education to reach a completely new level.

The authors of this article used the methods of surveys and interviews to find out the attitude of students and teachers to the new form of education, and to track the progress in learning. This article was written by the authors in order to provide the importance of clear guidelines and optimal use of distance learning technologies (Surma and Kirschner). Moreover, the authors identified important principles that will help students get used to a new form of education, for example, feedback and an individual approach. The main audiences of this article are students, parents and teachers who will be interested in this information for the successful implementation of distance learning. We intend to use this article to understand the possible future prospects of the distance learning method.

John Traxler, the Professor of Digital Learning in the Institute of Education at the University of Wolverhampton, in his article, “Distance Learning—Predictions and Possibilities” (2018), states the following. The author claims that the definition of distance learning is not clear, but vague and changeable. The author considers the process of distance learning in a global context and studies the issue of adaptation and implementation of distance learning. The author believes that people should be ready for global changes, be open and aware, since changes are inevitable.

The author of this article uses observation and comparison methods that allow determining the essence of distance learning, the danger of pressure on educational institutions, as well as the importance of innovations in education. This article was written by the author in order to create a complete understanding of the phenomenon of distance education in a global context (Traxler). In addition, this article demonstrates the difficulties of distance learning application in conditions of ignorance or isolation. The main audience of this article is teachers, students and parents who want to get acquainted in more detail with the concept of distance learning in a global context. We intend to use this article to learn more about what distance learning is, as well as its goals and objectives.

The main benefit of distance learning is that it allows a person to study anywhere, but requires a computer and the Internet. The material is easily accessible and easy to handle and structure, and it also has all the necessary features that students of higher educational institutions need. In addition, the student is free to build their own individual training schedule, depending on their free time and desire to study (Lassoued et al.). The difference between classical distance learning and its more advanced form is small – the lack of personal communication between students and teachers (Bojović et al.). In this paper, the pros and cons of distance learning will be considered, but first it is required to understand the very essence of distance learning.

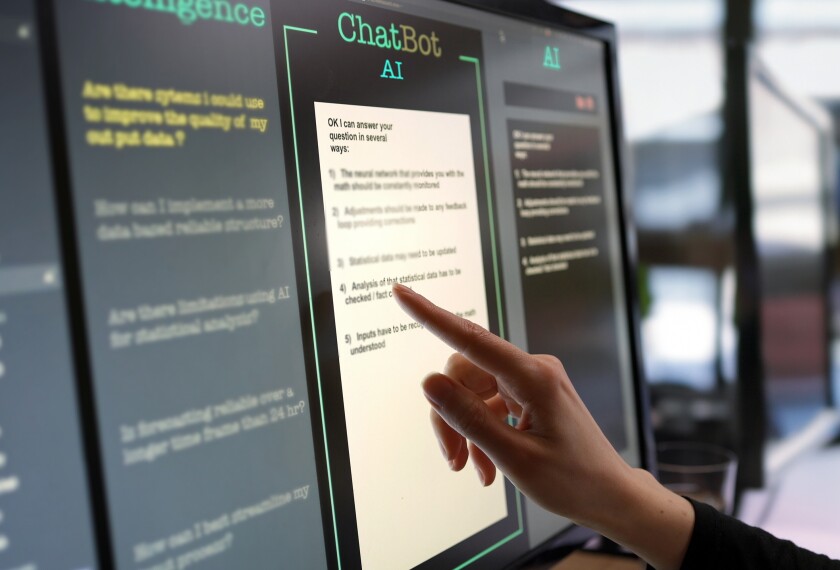

In the process of remote learning, students and teachers are at a significant spatial and temporal distance from each other. Teachers use a variety of computer technologies to make the process of remote learning as interesting and useful for students as possible (Schneider and Council). Distance type of education has an important goal-to expand opportunities and provide new services for those people who want to acquire new skills or change their profession. There are six main forms of distance learning, which are the most common.

- external education;

- university education;

- training that involves the cooperation of several educational institutions;

- creation of specialized institutions where distance classes are held;

- autonomous learning systems;

- special multimedia courses that differ in a certain informal component.

At the same time, different technologies are combined: pedagogical, informational, and often andragogic. There is a British synchronous model of distance learning and an American asynchronous one. Distance education is a new, specific form of education, somewhat different from the usual forms of full-time or distance learning (Dietrich et al.). As for the present, the real contingent of potential students can include those who are often on business trips, military personnel, women on maternity leave, and people with physical disabilities. In addition, this category consists of those who want to get additional education with a lack of time. Distance learning has several key characteristics that are important to consider when analyzing this type of learning.

- flexible and convenient schedule of classes;

- modularity;

- mass character;

- active mutual communication and a variety of communication tools;

- the totality of knowledge and orientation to the independence of students, to the motivation of learning.

Indeed, the effectiveness of distance learning directly depends on those teachers who work with students on the Internet. Such teachers should be psychologically ready to work with students in a new educational and cognitive network environment. Another problem is the infrastructure of student information support in networks. The question of what the structure and composition of the educational material should be remains open. Also, the question is raised about the conditions of access to distance learning courses.

Analyzing the components of distance learning related to the educational institution, they can determine the structure of the network system. It should include educational material submitted in the form of programs, tasks, control and graduation papers, and scientific and practical assistance (Costa et al.). The student should be provided with fundamental printed textbooks, teaching aids, and hypertext multimedia programs (Arthur-Nyarko et al.). Additional materials may include lectures prepared by teachers on disciplines that can be transmitted via the network. In addition, distance learning provides communication in various modes, teacher advice on implementing term papers, theses, or other final work.

The essential component of distance learning is the ability to consider situations that are close to reality. In addition, important elements are creating conditions for the self-realization of students, the disclosure of their potential, the systematic learning process, the individuality of the approach (Bojović et al.). This component is the basis of academic and cognitive activity and affects the quality of distance learning.

Electronic versions of textbooks, which became the basis for the creation of distance courses and traditional books, do not solve the problems of independent activity in obtaining knowledge. These software products only create a virtual learning environment in which distance learning is carried out. Here there are psychological problems, such as inexperience, lack of self-education skills, poor volitional self-regulation, the influence of group attitudes, etc. When developing distance learning programs, it is crucial to carefully plan classes, including each of them with the setting of learning goals and objectives.

If interpersonal communication between students and the teacher is ineffective, there is a possibility of a communication barrier. If this happens, the information is delivered in a distorted form, which leads to the fact that there is a threat of the cognitive barrier growing into a relationship barrier. The barrier of relations turns into a feeling of distrust and hostility towards information and its source.

There are also many disadvantages in distance learning that should be listed and that cannot be ignored. It is worth starting with technical and methodological problems, including ignoring the psychological laws of perception and assimilation of information using multimedia tools of different modalities. There are also methodological problems, including the complexity of developing electronic versions of traditional educational materials, primarily textbooks and practical manuals.

Many students and experts believe that distance learning has many indisputable and obvious advantages.

- A student studying remotely independently plans their schedule and decides how much time to devote to studying.

- The opportunity to study anywhere. Students studying remotely are not tied to a place or time, as they only need an Internet connection.

- Study on the job from the main activity. Distance learning allows to work or study at several courses at the same time to get additional education.

- High learning outcomes. Remote students study the necessary material independently, which allows them to better memorize and assimilate knowledge.

- Distance learning is much cheaper, since it does not require expenses for accommodation and travel, as well as for a foreign passport if the university is located abroad.

- Remote education provides a calm environment, as exams and communication with teachers are held online, which allows students to avoid anxiety.

- Teachers who conduct remote classes have the opportunity to do additional things, cover a larger number of students, as well as teach while, for example, on maternity leave.

- Remote learning allows teachers to use a more individual approach to their students, as well as to devote a sufficient amount of time to all students.

Experiments have confirmed that the quality and structure of training courses, as well as the quality of teaching in distance learning is often much better than in traditional forms of education. New electronic technologies can not only ensure the active involvement of students in the educational process, but also allow them to manage this process, unlike most traditional educational environments (Arthur-Nyarko et al.). The interactive capabilities of the programs and information delivery systems used in the distance learning system make it possible to establish and even stimulate feedback. Despite the predominant number of advantages of distance education, this system is not perfect. During the implementation of e-learning programs, the following problems of distance education were identified.

- Remote learning requires strong concentration and motivation. Almost all the educational material is mastered by a remote student independently. Remote classes require students to have perseverance and developed patience.

- In the process of distance learning, it is difficult to develop interpersonal communication skills, since contact with teachers and other students is minimal.

- In the process of distance learning, it is quite difficult to acquire practical skills, thus, specialties that require practical skills suffer.

- The problem of user identification. It is difficult to track whether a student wrote their exam honestly, since the only way to check this is video surveillance, which is not always possible.

- Insufficient computer literacy. In every country there are remote areas where there is no direct access to the Internet. Moreover, often the residents of such areas do not have any desire to learn, so it is necessary to spread computer literacy.

It is required to start by creating special Internet conferences and forums in schools that would guarantee the relative “live” communication of groups of students to deal with disadvantages (Chen et al.). It is also necessary to cooperate with traditional and distance learning, cooperation between teachers and students using a broad terminological and methodological base of psychology and pedagogy (Abuhammad). Despite all these problems, distance learning is very much appreciated by psychologists and teachers (Traxler). Nevertheless, the complete replacement of traditional education systems with similar ones-distance ones still causes some caution. One thing is indisputable – remotely studying students are more adapted to external conditions, are responsible and active, and therefore more successful in the modern business world.

Speaking about the distance form of education, it is necessary to talk about the creation of a single information and educational space. When it comes to distance learning, it is necessary to understand the presence of a teacher, a textbook and a student in the system, as well as the interaction of a teacher and students. It follows from this that the main thing in the organization of distance learning is the creation of electronic courses, the development of didactic foundations of distance learning, and the training of teachers-coordinators. It is not necessary to identify the distance form with the correspondence form of education, because it provides for constant contact with the teacher and imitation of all types of full-time training.

The dynamism of economic and socio-cultural processes in society causes changes in the field of education. Since the features of distance education are simply not acceptable for many students. Based on psychology and the methodology of independent learning, distance learning has some advantages and disadvantages. Summing up, we can unequivocally answer that distance education has a future. However, much depends on how quickly the problems of eliminating information illiteracy, technical equipment and improving the quality of e-education will be resolved. These factors arise during the implementation of remote scientific programs and projects. So, the factors and examples given above show the need to create and expand distance learning in the United States.

Abuhammad, Sawsan. “ Barriers to distance learning during the COVID-19 outbreak: A qualitative review from parents’ perspective. ” Heliyon (2020): e05482. Web.

Arthur-Nyarko, Emmanuel, Douglas Darko Agyei, and Justice Kofi Armah. “Digitizing distance learning materials: Measuring students’ readiness and intended challenges.” Education and Information Technologies (2020): 1-16. Web.

Bojović, Živko, et al. “Education in times of crisis: Rapid transition to distance learning.” Computer Applications in Engineering Education 28.6 (2020): 1467-1489.

Chen, Emily, Kristie Kaczmarek, and Hiroe Ohyama. “Student perceptions of distance learning strategies during COVID‐19.” Journal of dental education (2020). Web.

Costa, Roberto D., et al. “The theory of learning styles applied to distance learning.” Cognitive Systems Research 64 (2020): 134-145. Web.

Dietrich, Nicolas, et al. “Attempts, successes, and failures of distance learning in the time of COVID-19.” Journal of Chemical Education 97.9 (2020): 2448-2457. Web.

Lassoued, Zohra, Mohammed Alhendawi, and Raed Bashitialshaaer. “ An exploratory study of the obstacles for achieving quality in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. ” Education Sciences 10.9 (2020): 232. Web.

Schneider, Samantha L., and Martha Laurin Council. “Distance learning in the era of COVID-19.” Archives of dermatological research 313.5 (2021): 389-390. Web.

Surma, Tim, and Paul A. Kirschner. “Technology enhanced distance learning should not forget how learning happens.” Computers in human behavior 110 (2020): 106390. Web.

Traxler, John. “ Distance learning—Predictions and possibilities. ” Education Sciences 8.1 (2018): 35. Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, November 12). Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages. https://studycorgi.com/distance-learning-advantages-and-disadvantages/

"Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages." StudyCorgi , 12 Nov. 2022, studycorgi.com/distance-learning-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages'. 12 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages." November 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/distance-learning-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages." November 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/distance-learning-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages." November 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/distance-learning-advantages-and-disadvantages/.

This paper, “Distance Learning: Advantages and Disadvantages”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: January 2, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

How Effective Is Online Learning? What the Research Does and Doesn’t Tell Us

- Share article

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series on the practical takeaways from research.

The times have dictated school closings and the rapid expansion of online education. Can online lessons replace in-school time?

Clearly online time cannot provide many of the informal social interactions students have at school, but how will online courses do in terms of moving student learning forward? Research to date gives us some clues and also points us to what we could be doing to support students who are most likely to struggle in the online setting.

The use of virtual courses among K-12 students has grown rapidly in recent years. Florida, for example, requires all high school students to take at least one online course. Online learning can take a number of different forms. Often people think of Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, where thousands of students watch a video online and fill out questionnaires or take exams based on those lectures.

In the online setting, students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation.

Most online courses, however, particularly those serving K-12 students, have a format much more similar to in-person courses. The teacher helps to run virtual discussion among the students, assigns homework, and follows up with individual students. Sometimes these courses are synchronous (teachers and students all meet at the same time) and sometimes they are asynchronous (non-concurrent). In both cases, the teacher is supposed to provide opportunities for students to engage thoughtfully with subject matter, and students, in most cases, are required to interact with each other virtually.

Coronavirus and Schools

Online courses provide opportunities for students. Students in a school that doesn’t offer statistics classes may be able to learn statistics with virtual lessons. If students fail algebra, they may be able to catch up during evenings or summer using online classes, and not disrupt their math trajectory at school. So, almost certainly, online classes sometimes benefit students.

In comparisons of online and in-person classes, however, online classes aren’t as effective as in-person classes for most students. Only a little research has assessed the effects of online lessons for elementary and high school students, and even less has used the “gold standard” method of comparing the results for students assigned randomly to online or in-person courses. Jessica Heppen and colleagues at the American Institutes for Research and the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research randomly assigned students who had failed second semester Algebra I to either face-to-face or online credit recovery courses over the summer. Students’ credit-recovery success rates and algebra test scores were lower in the online setting. Students assigned to the online option also rated their class as more difficult than did their peers assigned to the face-to-face option.

Most of the research on online courses for K-12 students has used large-scale administrative data, looking at otherwise similar students in the two settings. One of these studies, by June Ahn of New York University and Andrew McEachin of the RAND Corp., examined Ohio charter schools; I did another with colleagues looking at Florida public school coursework. Both studies found evidence that online coursetaking was less effective.

About this series

This essay is the fifth in a series that aims to put the pieces of research together so that education decisionmakers can evaluate which policies and practices to implement.

The conveners of this project—Susanna Loeb, the director of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and Harvard education professor Heather Hill—have received grant support from the Annenberg Institute for this series.

To suggest other topics for this series or join in the conversation, use #EdResearchtoPractice on Twitter.

Read the full series here .

It is not surprising that in-person courses are, on average, more effective. Being in person with teachers and other students creates social pressures and benefits that can help motivate students to engage. Some students do as well in online courses as in in-person courses, some may actually do better, but, on average, students do worse in the online setting, and this is particularly true for students with weaker academic backgrounds.

Students who struggle in in-person classes are likely to struggle even more online. While the research on virtual schools in K-12 education doesn’t address these differences directly, a study of college students that I worked on with Stanford colleagues found very little difference in learning for high-performing students in the online and in-person settings. On the other hand, lower performing students performed meaningfully worse in online courses than in in-person courses.

But just because students who struggle in in-person classes are even more likely to struggle online doesn’t mean that’s inevitable. Online teachers will need to consider the needs of less-engaged students and work to engage them. Online courses might be made to work for these students on average, even if they have not in the past.

Just like in brick-and-mortar classrooms, online courses need a strong curriculum and strong pedagogical practices. Teachers need to understand what students know and what they don’t know, as well as how to help them learn new material. What is different in the online setting is that students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation. The teacher will need to set norms for engagement—such as requiring students to regularly ask questions and respond to their peers—that are different than the norms in the in-person setting.

Online courses are generally not as effective as in-person classes, but they are certainly better than no classes. A substantial research base developed by Karl Alexander at Johns Hopkins University and many others shows that students, especially students with fewer resources at home, learn less when they are not in school. Right now, virtual courses are allowing students to access lessons and exercises and interact with teachers in ways that would have been impossible if an epidemic had closed schools even a decade or two earlier. So we may be skeptical of online learning, but it is also time to embrace and improve it.

A version of this article appeared in the April 01, 2020 edition of Education Week as How Effective Is Online Learning?

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines

Jessie s. barrot.

College of Education, Arts and Sciences, National University, Manila, Philippines

Ian I. Llenares

Leo s. del rosario, associated data.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis that has shaken up its foundation. Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many studies have investigated this area, limited information is available regarding the challenges and the specific strategies that students employ to overcome them. Thus, this study attempts to fill in the void. Using a mixed-methods approach, the findings revealed that the online learning challenges of college students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. The findings further revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had the greatest impact on the quality of the learning experience and students’ mental health. In terms of strategies employed by students, the most frequently used were resource management and utilization, help-seeking, technical aptitude enhancement, time management, and learning environment control. Implications for classroom practice, policy-making, and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the world has seen significant changes in the landscape of education as a result of the ever-expanding influence of technology. One such development is the adoption of online learning across different learning contexts, whether formal or informal, academic and non-academic, and residential or remotely. We began to witness schools, teachers, and students increasingly adopt e-learning technologies that allow teachers to deliver instruction interactively, share resources seamlessly, and facilitate student collaboration and interaction (Elaish et al., 2019 ; Garcia et al., 2018 ). Although the efficacy of online learning has long been acknowledged by the education community (Barrot, 2020 , 2021 ; Cavanaugh et al., 2009 ; Kebritchi et al., 2017 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Wallace, 2003 ), evidence on the challenges in its implementation continues to build up (e.g., Boelens et al., 2017 ; Rasheed et al., 2020 ).

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic) that has shaken up its foundation. Thus, various governments across the globe have launched a crisis response to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on education. This response includes, but is not limited to, curriculum revisions, provision for technological resources and infrastructure, shifts in the academic calendar, and policies on instructional delivery and assessment. Inevitably, these developments compelled educational institutions to migrate to full online learning until face-to-face instruction is allowed. The current circumstance is unique as it could aggravate the challenges experienced during online learning due to restrictions in movement and health protocols (Gonzales et al., 2020 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, many studies have investigated this area with a focus on students’ mental health (Copeland et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ), home learning (Suryaman et al., 2020 ), self-regulation (Carter et al., 2020 ), virtual learning environment (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Hew et al., 2020 ; Tang et al., 2020 ), and students’ overall learning experience (e.g., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). There are two key differences that set the current study apart from the previous studies. First, it sheds light on the direct impact of the pandemic on the challenges that students experience in an online learning space. Second, the current study explores students’ coping strategies in this new learning setup. Addressing these areas would shed light on the extent of challenges that students experience in a full online learning space, particularly within the context of the pandemic. Meanwhile, our nuanced understanding of the strategies that students use to overcome their challenges would provide relevant information to school administrators and teachers to better support the online learning needs of students. This information would also be critical in revisiting the typology of strategies in an online learning environment.

Literature review

Education and the covid-19 pandemic.

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, occurred in China and has spread rapidly across the globe within a few months. COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus that attacks the respiratory system (World Health Organization, 2020 ). As of January 2021, COVID-19 has infected 94 million people and has caused 2 million deaths in 191 countries and territories (John Hopkins University, 2021 ). This pandemic has created a massive disruption of the educational systems, affecting over 1.5 billion students. It has forced the government to cancel national examinations and the schools to temporarily close, cease face-to-face instruction, and strictly observe physical distancing. These events have sparked the digital transformation of higher education and challenged its ability to respond promptly and effectively. Schools adopted relevant technologies, prepared learning and staff resources, set systems and infrastructure, established new teaching protocols, and adjusted their curricula. However, the transition was smooth for some schools but rough for others, particularly those from developing countries with limited infrastructure (Pham & Nguyen, 2020 ; Simbulan, 2020 ).

Inevitably, schools and other learning spaces were forced to migrate to full online learning as the world continues the battle to control the vicious spread of the virus. Online learning refers to a learning environment that uses the Internet and other technological devices and tools for synchronous and asynchronous instructional delivery and management of academic programs (Usher & Barak, 2020 ; Huang, 2019 ). Synchronous online learning involves real-time interactions between the teacher and the students, while asynchronous online learning occurs without a strict schedule for different students (Singh & Thurman, 2019 ). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has taken the status of interim remote teaching that serves as a response to an exigency. However, the migration to a new learning space has faced several major concerns relating to policy, pedagogy, logistics, socioeconomic factors, technology, and psychosocial factors (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Varea & González-Calvo, 2020 ). With reference to policies, government education agencies and schools scrambled to create fool-proof policies on governance structure, teacher management, and student management. Teachers, who were used to conventional teaching delivery, were also obliged to embrace technology despite their lack of technological literacy. To address this problem, online learning webinars and peer support systems were launched. On the part of the students, dropout rates increased due to economic, psychological, and academic reasons. Academically, although it is virtually possible for students to learn anything online, learning may perhaps be less than optimal, especially in courses that require face-to-face contact and direct interactions (Franchi, 2020 ).

Related studies

Recently, there has been an explosion of studies relating to the new normal in education. While many focused on national policies, professional development, and curriculum, others zeroed in on the specific learning experience of students during the pandemic. Among these are Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ) who examined the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health and their coping mechanisms. Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) reported that the pandemic adversely affected students’ behavioral and emotional functioning, particularly attention and externalizing problems (i.e., mood and wellness behavior), which were caused by isolation, economic/health effects, and uncertainties. In Fawaz et al.’s ( 2021 ) study, students raised their concerns on learning and evaluation methods, overwhelming task load, technical difficulties, and confinement. To cope with these problems, students actively dealt with the situation by seeking help from their teachers and relatives and engaging in recreational activities. These active-oriented coping mechanisms of students were aligned with Carter et al.’s ( 2020 ), who explored students’ self-regulation strategies.

In another study, Tang et al. ( 2020 ) examined the efficacy of different online teaching modes among engineering students. Using a questionnaire, the results revealed that students were dissatisfied with online learning in general, particularly in the aspect of communication and question-and-answer modes. Nonetheless, the combined model of online teaching with flipped classrooms improved students’ attention, academic performance, and course evaluation. A parallel study was undertaken by Hew et al. ( 2020 ), who transformed conventional flipped classrooms into fully online flipped classes through a cloud-based video conferencing app. Their findings suggested that these two types of learning environments were equally effective. They also offered ways on how to effectively adopt videoconferencing-assisted online flipped classrooms. Unlike the two studies, Suryaman et al. ( 2020 ) looked into how learning occurred at home during the pandemic. Their findings showed that students faced many obstacles in a home learning environment, such as lack of mastery of technology, high Internet cost, and limited interaction/socialization between and among students. In a related study, Kapasia et al. ( 2020 ) investigated how lockdown impacts students’ learning performance. Their findings revealed that the lockdown made significant disruptions in students’ learning experience. The students also reported some challenges that they faced during their online classes. These include anxiety, depression, poor Internet service, and unfavorable home learning environment, which were aggravated when students are marginalized and from remote areas. Contrary to Kapasia et al.’s ( 2020 ) findings, Gonzales et al. ( 2020 ) found that confinement of students during the pandemic had significant positive effects on their performance. They attributed these results to students’ continuous use of learning strategies which, in turn, improved their learning efficiency.

Finally, there are those that focused on students’ overall online learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. One such study was that of Singh et al. ( 2020 ), who examined students’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic using a quantitative descriptive approach. Their findings indicated that students appreciated the use of online learning during the pandemic. However, half of them believed that the traditional classroom setting was more effective than the online learning platform. Methodologically, the researchers acknowledge that the quantitative nature of their study restricts a deeper interpretation of the findings. Unlike the above study, Khalil et al. ( 2020 ) qualitatively explored the efficacy of synchronized online learning in a medical school in Saudi Arabia. The results indicated that students generally perceive synchronous online learning positively, particularly in terms of time management and efficacy. However, they also reported technical (internet connectivity and poor utility of tools), methodological (content delivery), and behavioral (individual personality) challenges. Their findings also highlighted the failure of the online learning environment to address the needs of courses that require hands-on practice despite efforts to adopt virtual laboratories. In a parallel study, Adarkwah ( 2021 ) examined students’ online learning experience during the pandemic using a narrative inquiry approach. The findings indicated that Ghanaian students considered online learning as ineffective due to several challenges that they encountered. Among these were lack of social interaction among students, poor communication, lack of ICT resources, and poor learning outcomes. More recently, Day et al. ( 2021 ) examined the immediate impact of COVID-19 on students’ learning experience. Evidence from six institutions across three countries revealed some positive experiences and pre-existing inequities. Among the reported challenges are lack of appropriate devices, poor learning space at home, stress among students, and lack of fieldwork and access to laboratories.

Although there are few studies that report the online learning challenges that higher education students experience during the pandemic, limited information is available regarding the specific strategies that they use to overcome them. It is in this context that the current study was undertaken. This mixed-methods study investigates students’ online learning experience in higher education. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed: (1) What is the extent of challenges that students experience in an online learning environment? (2) How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the online learning challenges that students experience? (3) What strategies did students use to overcome the challenges?

Conceptual framework

The typology of challenges examined in this study is largely based on Rasheed et al.’s ( 2020 ) review of students’ experience in an online learning environment. These challenges are grouped into five general clusters, namely self-regulation (SRC), technological literacy and competency (TLCC), student isolation (SIC), technological sufficiency (TSC), and technological complexity (TCC) challenges (Rasheed et al., 2020 , p. 5). SRC refers to a set of behavior by which students exercise control over their emotions, actions, and thoughts to achieve learning objectives. TLCC relates to a set of challenges about students’ ability to effectively use technology for learning purposes. SIC relates to the emotional discomfort that students experience as a result of being lonely and secluded from their peers. TSC refers to a set of challenges that students experience when accessing available online technologies for learning. Finally, there is TCC which involves challenges that students experience when exposed to complex and over-sufficient technologies for online learning.

To extend Rasheed et al. ( 2020 ) categories and to cover other potential challenges during online classes, two more clusters were added, namely learning resource challenges (LRC) and learning environment challenges (LEC) (Buehler, 2004 ; Recker et al., 2004 ; Seplaki et al., 2014 ; Xue et al., 2020 ). LRC refers to a set of challenges that students face relating to their use of library resources and instructional materials, whereas LEC is a set of challenges that students experience related to the condition of their learning space that shapes their learning experiences, beliefs, and attitudes. Since learning environment at home and learning resources available to students has been reported to significantly impact the quality of learning and their achievement of learning outcomes (Drane et al., 2020 ; Suryaman et al., 2020 ), the inclusion of LRC and LEC would allow us to capture other important challenges that students experience during the pandemic, particularly those from developing regions. This comprehensive list would provide us a clearer and detailed picture of students’ experiences when engaged in online learning in an emergency. Given the restrictions in mobility at macro and micro levels during the pandemic, it is also expected that such conditions would aggravate these challenges. Therefore, this paper intends to understand these challenges from students’ perspectives since they are the ones that are ultimately impacted when the issue is about the learning experience. We also seek to explore areas that provide inconclusive findings, thereby setting the path for future research.

Material and methods

The present study adopted a descriptive, mixed-methods approach to address the research questions. This approach allowed the researchers to collect complex data about students’ experience in an online learning environment and to clearly understand the phenomena from their perspective.

Participants

This study involved 200 (66 male and 134 female) students from a private higher education institution in the Philippines. These participants were Psychology, Physical Education, and Sports Management majors whose ages ranged from 17 to 25 ( x ̅ = 19.81; SD = 1.80). The students have been engaged in online learning for at least two terms in both synchronous and asynchronous modes. The students belonged to low- and middle-income groups but were equipped with the basic online learning equipment (e.g., computer, headset, speakers) and computer skills necessary for their participation in online classes. Table Table1 1 shows the primary and secondary platforms that students used during their online classes. The primary platforms are those that are formally adopted by teachers and students in a structured academic context, whereas the secondary platforms are those that are informally and spontaneously used by students and teachers for informal learning and to supplement instructional delivery. Note that almost all students identified MS Teams as their primary platform because it is the official learning management system of the university.

Participants’ Online Learning Platforms

| Learning Platforms | Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Supplementary | |||

| Blackboard | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| Canvas | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| Edmodo | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| 9 | 4.50 | 170 | 85.00 | |

| Google Classroom | 5 | 2.50 | 15 | 7.50 |

| Moodle | - | - | 7 | 3.50 |

| MS Teams | 184 | 92.00 | - | - |

| Schoology | 1 | 0.50 | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | |

| Zoom | 1 | 0.50 | 5 | 2.50 |

| 200 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |

Informed consent was sought from the participants prior to their involvement. Before students signed the informed consent form, they were oriented about the objectives of the study and the extent of their involvement. They were also briefed about the confidentiality of information, their anonymity, and their right to refuse to participate in the investigation. Finally, the participants were informed that they would incur no additional cost from their participation.

Instrument and data collection

The data were collected using a retrospective self-report questionnaire and a focused group discussion (FGD). A self-report questionnaire was considered appropriate because the indicators relate to affective responses and attitude (Araujo et al., 2017 ; Barrot, 2016 ; Spector, 1994 ). Although the participants may tell more than what they know or do in a self-report survey (Matsumoto, 1994 ), this challenge was addressed by explaining to them in detail each of the indicators and using methodological triangulation through FGD. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (1) participant’s personal information section, (2) the background information on the online learning environment, (3) the rating scale section for the online learning challenges, (4) the open-ended section. The personal information section asked about the students’ personal information (name, school, course, age, and sex), while the background information section explored the online learning mode and platforms (primary and secondary) used in class, and students’ length of engagement in online classes. The rating scale section contained 37 items that relate to SRC (6 items), TLCC (10 items), SIC (4 items), TSC (6 items), TCC (3 items), LRC (4 items), and LEC (4 items). The Likert scale uses six scores (i.e., 5– to a very great extent , 4– to a great extent , 3– to a moderate extent , 2– to some extent , 1– to a small extent , and 0 –not at all/negligible ) assigned to each of the 37 items. Finally, the open-ended questions asked about other challenges that students experienced, the impact of the pandemic on the intensity or extent of the challenges they experienced, and the strategies that the participants employed to overcome the eight different types of challenges during online learning. Two experienced educators and researchers reviewed the questionnaire for clarity, accuracy, and content and face validity. The piloting of the instrument revealed that the tool had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

The FGD protocol contains two major sections: the participants’ background information and the main questions. The background information section asked about the students’ names, age, courses being taken, online learning mode used in class. The items in the main questions section covered questions relating to the students’ overall attitude toward online learning during the pandemic, the reasons for the scores they assigned to each of the challenges they experienced, the impact of the pandemic on students’ challenges, and the strategies they employed to address the challenges. The same experts identified above validated the FGD protocol.

Both the questionnaire and the FGD were conducted online via Google survey and MS Teams, respectively. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire, while the FGD lasted for about 90 min. Students were allowed to ask for clarification and additional explanations relating to the questionnaire content, FGD, and procedure. Online surveys and interview were used because of the ongoing lockdown in the city. For the purpose of triangulation, 20 (10 from Psychology and 10 from Physical Education and Sports Management) randomly selected students were invited to participate in the FGD. Two separate FGDs were scheduled for each group and were facilitated by researcher 2 and researcher 3, respectively. The interviewers ensured that the participants were comfortable and open to talk freely during the FGD to avoid social desirability biases (Bergen & Labonté, 2020 ). These were done by informing the participants that there are no wrong responses and that their identity and responses would be handled with the utmost confidentiality. With the permission of the participants, the FGD was recorded to ensure that all relevant information was accurately captured for transcription and analysis.

Data analysis

To address the research questions, we used both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative analysis, we entered all the data into an excel spreadsheet. Then, we computed the mean scores ( M ) and standard deviations ( SD ) to determine the level of challenges experienced by students during online learning. The mean score for each descriptor was interpreted using the following scheme: 4.18 to 5.00 ( to a very great extent ), 3.34 to 4.17 ( to a great extent ), 2.51 to 3.33 ( to a moderate extent ), 1.68 to 2.50 ( to some extent ), 0.84 to 1.67 ( to a small extent ), and 0 to 0.83 ( not at all/negligible ). The equal interval was adopted because it produces more reliable and valid information than other types of scales (Cicchetti et al., 2006 ).

For the qualitative data, we analyzed the students’ responses in the open-ended questions and the transcribed FGD using the predetermined categories in the conceptual framework. Specifically, we used multilevel coding in classifying the codes from the transcripts (Birks & Mills, 2011 ). To do this, we identified the relevant codes from the responses of the participants and categorized these codes based on the similarities or relatedness of their properties and dimensions. Then, we performed a constant comparative and progressive analysis of cases to allow the initially identified subcategories to emerge and take shape. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, two coders independently analyzed the qualitative data. Both coders familiarize themselves with the purpose, research questions, research method, and codes and coding scheme of the study. They also had a calibration session and discussed ways on how they could consistently analyze the qualitative data. Percent of agreement between the two coders was 86 percent. Any disagreements in the analysis were discussed by the coders until an agreement was achieved.

This study investigated students’ online learning experience in higher education within the context of the pandemic. Specifically, we identified the extent of challenges that students experienced, how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their online learning experience, and the strategies that they used to confront these challenges.

The extent of students’ online learning challenges

Table Table2 2 presents the mean scores and SD for the extent of challenges that students’ experienced during online learning. Overall, the students experienced the identified challenges to a moderate extent ( x ̅ = 2.62, SD = 1.03) with scores ranging from x ̅ = 1.72 ( to some extent ) to x ̅ = 3.58 ( to a great extent ). More specifically, the greatest challenge that students experienced was related to the learning environment ( x ̅ = 3.49, SD = 1.27), particularly on distractions at home, limitations in completing the requirements for certain subjects, and difficulties in selecting the learning areas and study schedule. It is, however, found that the least challenge was on technological literacy and competency ( x ̅ = 2.10, SD = 1.13), particularly on knowledge and training in the use of technology, technological intimidation, and resistance to learning technologies. Other areas that students experienced the least challenge are Internet access under TSC and procrastination under SRC. Nonetheless, nearly half of the students’ responses per indicator rated the challenges they experienced as moderate (14 of the 37 indicators), particularly in TCC ( x ̅ = 2.51, SD = 1.31), SIC ( x ̅ = 2.77, SD = 1.34), and LRC ( x ̅ = 2.93, SD = 1.31).

The Extent of Students’ Challenges during the Interim Online Learning

| CHALLENGES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Self-regulation challenges (SRC) | 2.37 | 1.16 |

| 1. I delay tasks related to my studies so that they are either not fully completed by their deadline or had to be rushed to be completed. | 1.84 | 1.47 |

| 2. I fail to get appropriate help during online classes. | 2.04 | 1.44 |

| 3. I lack the ability to control my own thoughts, emotions, and actions during online classes. | 2.51 | 1.65 |

| 4. I have limited preparation before an online class. | 2.68 | 1.54 |

| 5. I have poor time management skills during online classes. | 2.50 | 1.53 |

| 6. I fail to properly use online peer learning strategies (i.e., learning from one another to better facilitate learning such as peer tutoring, group discussion, and peer feedback). | 2.34 | 1.50 |

| Technological literacy and competency challenges (TLCC) | 2.10 | 1.13 |

| 7. I lack competence and proficiency in using various interfaces or systems that allow me to control a computer or another embedded system for studying. | 2.05 | 1.39 |

| 8. I resist learning technology. | 1.89 | 1.46 |

| 9. I am distracted by an overly complex technology. | 2.44 | 1.43 |

| 10. I have difficulties in learning a new technology. | 2.06 | 1.50 |

| 11. I lack the ability to effectively use technology to facilitate learning. | 2.08 | 1.51 |

| 12. I lack knowledge and training in the use of technology. | 1.76 | 1.43 |

| 13. I am intimidated by the technologies used for learning. | 1.89 | 1.44 |

| 14. I resist and/or am confused when getting appropriate help during online classes. | 2.19 | 1.52 |

| 15. I have poor understanding of directions and expectations during online learning. | 2.16 | 1.56 |

| 16. I perceive technology as a barrier to getting help from others during online classes. | 2.47 | 1.43 |

| Student isolation challenges (SIC) | 2.77 | 1.34 |

| 17. I feel emotionally disconnected or isolated during online classes. | 2.71 | 1.58 |

| 18. I feel disinterested during online class. | 2.54 | 1.53 |

| 19. I feel unease and uncomfortable in using video projection, microphones, and speakers. | 2.90 | 1.57 |

| 20. I feel uncomfortable being the center of attention during online classes. | 2.93 | 1.67 |

| Technological sufficiency challenges (TSC) | 2.31 | 1.29 |

| 21. I have an insufficient access to learning technology. | 2.27 | 1.52 |

| 22. I experience inequalities with regard to to and use of technologies during online classes because of my socioeconomic, physical, and psychological condition. | 2.34 | 1.68 |

| 23. I have an outdated technology. | 2.04 | 1.62 |

| 24. I do not have Internet access during online classes. | 1.72 | 1.65 |

| 25. I have low bandwidth and slow processing speeds. | 2.66 | 1.62 |

| 26. I experience technical difficulties in completing my assignments. | 2.84 | 1.54 |

| Technological complexity challenges (TCC) | 2.51 | 1.31 |

| 27. I am distracted by the complexity of the technology during online classes. | 2.34 | 1.46 |

| 28. I experience difficulties in using complex technology. | 2.33 | 1.51 |

| 29. I experience difficulties when using longer videos for learning. | 2.87 | 1.48 |

| Learning resource challenges (LRC) | 2.93 | 1.31 |

| 30. I have an insufficient access to library resources. | 2.86 | 1.72 |

| 31. I have an insufficient access to laboratory equipment and materials. | 3.16 | 1.71 |

| 32. I have limited access to textbooks, worksheets, and other instructional materials. | 2.63 | 1.57 |

| 33. I experience financial challenges when accessing learning resources and technology. | 3.07 | 1.57 |

| Learning environment challenges (LEC) | 3.49 | 1.27 |

| 34. I experience online distractions such as social media during online classes. | 3.20 | 1.58 |

| 35. I experience distractions at home as a learning environment. | 3.55 | 1.54 |

| 36. I have difficulties in selecting the best time and area for learning at home. | 3.40 | 1.58 |

| 37. Home set-up limits the completion of certain requirements for my subject (e.g., laboratory and physical activities). | 3.58 | 1.52 |

| AVERAGE | 2.62 | 1.03 |

Out of 200 students, 181 responded to the question about other challenges that they experienced. Most of their responses were already covered by the seven predetermined categories, except for 18 responses related to physical discomfort ( N = 5) and financial challenges ( N = 13). For instance, S108 commented that “when it comes to eyes and head, my eyes and head get ache if the session of class was 3 h straight in front of my gadget.” In the same vein, S194 reported that “the long exposure to gadgets especially laptop, resulting in body pain & headaches.” With reference to physical financial challenges, S66 noted that “not all the time I have money to load”, while S121 claimed that “I don't know until when are we going to afford budgeting our money instead of buying essentials.”

Impact of the pandemic on students’ online learning challenges

Another objective of this study was to identify how COVID-19 influenced the online learning challenges that students experienced. As shown in Table Table3, 3 , most of the students’ responses were related to teaching and learning quality ( N = 86) and anxiety and other mental health issues ( N = 52). Regarding the adverse impact on teaching and learning quality, most of the comments relate to the lack of preparation for the transition to online platforms (e.g., S23, S64), limited infrastructure (e.g., S13, S65, S99, S117), and poor Internet service (e.g., S3, S9, S17, S41, S65, S99). For the anxiety and mental health issues, most students reported that the anxiety, boredom, sadness, and isolation they experienced had adversely impacted the way they learn (e.g., S11, S130), completing their tasks/activities (e.g., S56, S156), and their motivation to continue studying (e.g., S122, S192). The data also reveal that COVID-19 aggravated the financial difficulties experienced by some students ( N = 16), consequently affecting their online learning experience. This financial impact mainly revolved around the lack of funding for their online classes as a result of their parents’ unemployment and the high cost of Internet data (e.g., S18, S113, S167). Meanwhile, few concerns were raised in relation to COVID-19’s impact on mobility ( N = 7) and face-to-face interactions ( N = 7). For instance, some commented that the lack of face-to-face interaction with her classmates had a detrimental effect on her learning (S46) and socialization skills (S36), while others reported that restrictions in mobility limited their learning experience (S78, S110). Very few comments were related to no effect ( N = 4) and positive effect ( N = 2). The above findings suggest the pandemic had additive adverse effects on students’ online learning experience.

Summary of students’ responses on the impact of COVID-19 on their online learning experience

| Areas | Sample Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Reduces the quality of learning experience | 86 | (S13) (S65) (S118) |

| Causes anxiety and other mental health issues | 52 | (S11) (S56) (S192) |

| Aggravates financial problems | 16 | (S18) (S167) |

| Limits interaction | 7 | (S36) (S46) |

| Restricts mobility | 7 | (S78) (S110) |

| No effect | 4 | (S100) (S168) |

| Positive effect | 2 | (S35) (S112) |

Students’ strategies to overcome challenges in an online learning environment

The third objective of this study is to identify the strategies that students employed to overcome the different online learning challenges they experienced. Table Table4 4 presents that the most commonly used strategies used by students were resource management and utilization ( N = 181), help-seeking ( N = 155), technical aptitude enhancement ( N = 122), time management ( N = 98), and learning environment control ( N = 73). Not surprisingly, the top two strategies were also the most consistently used across different challenges. However, looking closely at each of the seven challenges, the frequency of using a particular strategy varies. For TSC and LRC, the most frequently used strategy was resource management and utilization ( N = 52, N = 89, respectively), whereas technical aptitude enhancement was the students’ most preferred strategy to address TLCC ( N = 77) and TCC ( N = 38). In the case of SRC, SIC, and LEC, the most frequently employed strategies were time management ( N = 71), psychological support ( N = 53), and learning environment control ( N = 60). In terms of consistency, help-seeking appears to be the most consistent across the different challenges in an online learning environment. Table Table4 4 further reveals that strategies used by students within a specific type of challenge vary.

Students’ Strategies to Overcome Online Learning Challenges

| Strategies | SRC | TLCC | SIC | TSC | TCC | LRC | LEC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | 7 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 17 | 60 |

| Cognitive aptitude enhancement | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

| Concentration and focus | 13 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 43 |

| Focus and concentration | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Goal-setting | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Help-seeking | 13 | 42 | 2 | 36 | 16 | 28 | 18 | 155 |

| Learning environment control | 1 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 60 | 73 |

| Motivation | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Optimism | 4 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 47 |

| Peer learning | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Psychosocial support | 3 | 0 | 53 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 |

| Reflection | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Relaxation and recreation | 16 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| Resource management & utilization | 3 | 11 | 0 | 52 | 20 | 89 | 6 | 181 |

| Self-belief | 0 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| Self-discipline | 12 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 32 |

| Self-study | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Technical aptitude enhancement | 0 | 77 | 0 | 7 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 122 |

| Thought control | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| Time management | 71 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 98 |

| Transcendental strategies | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Discussion and conclusions

The current study explores the challenges that students experienced in an online learning environment and how the pandemic impacted their online learning experience. The findings revealed that the online learning challenges of students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. Based on the students’ responses, their challenges were also found to be aggravated by the pandemic, especially in terms of quality of learning experience, mental health, finances, interaction, and mobility. With reference to previous studies (i.e., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Copeland et al., 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ), the current study has complemented their findings on the pedagogical, logistical, socioeconomic, technological, and psychosocial online learning challenges that students experience within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study extended previous studies and our understanding of students’ online learning experience by identifying both the presence and extent of online learning challenges and by shedding light on the specific strategies they employed to overcome them.

Overall findings indicate that the extent of challenges and strategies varied from one student to another. Hence, they should be viewed as a consequence of interaction several many factors. Students’ responses suggest that their online learning challenges and strategies were mediated by the resources available to them, their interaction with their teachers and peers, and the school’s existing policies and guidelines for online learning. In the context of the pandemic, the imposed lockdowns and students’ socioeconomic condition aggravated the challenges that students experience.

While most studies revealed that technology use and competency were the most common challenges that students face during the online classes (see Rasheed et al., 2020 ), the case is a bit different in developing countries in times of pandemic. As the findings have shown, the learning environment is the greatest challenge that students needed to hurdle, particularly distractions at home (e.g., noise) and limitations in learning space and facilities. This data suggests that online learning challenges during the pandemic somehow vary from the typical challenges that students experience in a pre-pandemic online learning environment. One possible explanation for this result is that restriction in mobility may have aggravated this challenge since they could not go to the school or other learning spaces beyond the vicinity of their respective houses. As shown in the data, the imposition of lockdown restricted students’ learning experience (e.g., internship and laboratory experiments), limited their interaction with peers and teachers, caused depression, stress, and anxiety among students, and depleted the financial resources of those who belong to lower-income group. All of these adversely impacted students’ learning experience. This finding complemented earlier reports on the adverse impact of lockdown on students’ learning experience and the challenges posed by the home learning environment (e.g., Day et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Nonetheless, further studies are required to validate the impact of restrictions on mobility on students’ online learning experience. The second reason that may explain the findings relates to students’ socioeconomic profile. Consistent with the findings of Adarkwah ( 2021 ) and Day et al. ( 2021 ), the current study reveals that the pandemic somehow exposed the many inequities in the educational systems within and across countries. In the case of a developing country, families from lower socioeconomic strata (as in the case of the students in this study) have limited learning space at home, access to quality Internet service, and online learning resources. This is the reason the learning environment and learning resources recorded the highest level of challenges. The socioeconomic profile of the students (i.e., low and middle-income group) is the same reason financial problems frequently surfaced from their responses. These students frequently linked the lack of financial resources to their access to the Internet, educational materials, and equipment necessary for online learning. Therefore, caution should be made when interpreting and extending the findings of this study to other contexts, particularly those from higher socioeconomic strata.

Among all the different online learning challenges, the students experienced the least challenge on technological literacy and competency. This is not surprising considering a plethora of research confirming Gen Z students’ (born since 1996) high technological and digital literacy (Barrot, 2018 ; Ng, 2012 ; Roblek et al., 2019 ). Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on students’ online learning experience, the findings reveal that teaching and learning quality and students’ mental health were the most affected. The anxiety that students experienced does not only come from the threats of COVID-19 itself but also from social and physical restrictions, unfamiliarity with new learning platforms, technical issues, and concerns about financial resources. These findings are consistent with that of Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ), who reported the adverse effects of the pandemic on students’ mental and emotional well-being. This data highlights the need to provide serious attention to the mediating effects of mental health, restrictions in mobility, and preparedness in delivering online learning.

Nonetheless, students employed a variety of strategies to overcome the challenges they faced during online learning. For instance, to address the home learning environment problems, students talked to their family (e.g., S12, S24), transferred to a quieter place (e.g., S7, S 26), studied at late night where all family members are sleeping already (e.g., S51), and consulted with their classmates and teachers (e.g., S3, S9, S156, S193). To overcome the challenges in learning resources, students used the Internet (e.g., S20, S27, S54, S91), joined Facebook groups that share free resources (e.g., S5), asked help from family members (e.g., S16), used resources available at home (e.g., S32), and consulted with the teachers (e.g., S124). The varying strategies of students confirmed earlier reports on the active orientation that students take when faced with academic- and non-academic-related issues in an online learning space (see Fawaz et al., 2021 ). The specific strategies that each student adopted may have been shaped by different factors surrounding him/her, such as available resources, student personality, family structure, relationship with peers and teacher, and aptitude. To expand this study, researchers may further investigate this area and explore how and why different factors shape their use of certain strategies.

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this study. First, this study highlighted the importance of emergency response capability and readiness of higher education institutions in case another crisis strikes again. Critical areas that need utmost attention include (but not limited to) national and institutional policies, protocol and guidelines, technological infrastructure and resources, instructional delivery, staff development, potential inequalities, and collaboration among key stakeholders (i.e., parents, students, teachers, school leaders, industry, government education agencies, and community). Second, the findings have expanded our understanding of the different challenges that students might confront when we abruptly shift to full online learning, particularly those from countries with limited resources, poor Internet infrastructure, and poor home learning environment. Schools with a similar learning context could use the findings of this study in developing and enhancing their respective learning continuity plans to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic. This study would also provide students relevant information needed to reflect on the possible strategies that they may employ to overcome the challenges. These are critical information necessary for effective policymaking, decision-making, and future implementation of online learning. Third, teachers may find the results useful in providing proper interventions to address the reported challenges, particularly in the most critical areas. Finally, the findings provided us a nuanced understanding of the interdependence of learning tools, learners, and learning outcomes within an online learning environment; thus, giving us a multiperspective of hows and whys of a successful migration to full online learning.

Some limitations in this study need to be acknowledged and addressed in future studies. One limitation of this study is that it exclusively focused on students’ perspectives. Future studies may widen the sample by including all other actors taking part in the teaching–learning process. Researchers may go deeper by investigating teachers’ views and experience to have a complete view of the situation and how different elements interact between them or affect the others. Future studies may also identify some teacher-related factors that could influence students’ online learning experience. In the case of students, their age, sex, and degree programs may be examined in relation to the specific challenges and strategies they experience. Although the study involved a relatively large sample size, the participants were limited to college students from a Philippine university. To increase the robustness of the findings, future studies may expand the learning context to K-12 and several higher education institutions from different geographical regions. As a final note, this pandemic has undoubtedly reshaped and pushed the education system to its limits. However, this unprecedented event is the same thing that will make the education system stronger and survive future threats.

Authors’ contributions

Jessie Barrot led the planning, prepared the instrument, wrote the report, and processed and analyzed data. Ian Llenares participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing. Leo del Rosario participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing.

No funding was received in the conduct of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

The study has undergone appropriate ethics protocol.

Informed consent was sought from the participants.

Authors consented the publication. Participants consented to publication as long as confidentiality is observed.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Adarkwah MA. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies. 2021; 26 (2):1665–1685. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almaiah MA, Al-Khasawneh A, Althunibat A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies. 2020; 25 :5261–5280. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Araujo T, Wonneberger A, Neijens P, de Vreese C. How much time do you spend online? Understanding and improving the accuracy of self-reported measures of Internet use. Communication Methods and Measures. 2017; 11 (3):173–190. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2017.1317337. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrot, J. S. (2016). Using Facebook-based e-portfolio in ESL writing classrooms: Impact and challenges. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29 (3), 286–301.

- Barrot, J. S. (2018). Facebook as a learning environment for language teaching and learning: A critical analysis of the literature from 2010 to 2017. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34 (6), 863–875.

- Barrot, J. S. (2020). Scientific mapping of social media in education: A decade of exponential growth. Journal of Educational Computing Research . 10.1177/0735633120972010.

- Barrot, J. S. (2021). Social media as a language learning environment: A systematic review of the literature (2008–2019). Computer Assisted Language Learning . 10.1080/09588221.2021.1883673.

- Bergen N, Labonté R. “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2020; 30 (5):783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]