COVID-19 and Chronic Disease: The Impact Now and in the Future

ESSAY — Volume 18 — June 17, 2021

Karen A. Hacker, MD, MPH 1 ; Peter A. Briss, MD, MPH 1 ; Lisa Richardson, MD, MPH 1 ; Janet Wright, MD 1 ; Ruth Petersen, MD, MPH 1 ( View author affiliations )

Suggested citation for this article: Hacker KA, Briss PA, Richardson L, Wright J, Petersen R. COVID-19 and Chronic Disease: The Impact Now and in the Future. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:210086. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210086 external icon .

PEER REVIEWED

The Problem of COVID-19 and Chronic Disease

Raise awareness, collaborate on solutions and build trust, address long-term covid-19 sequelae, how will the national center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion contribute, acknowledgments, author information.

Chronic diseases represent 7 of the top 10 causes of death in the United States (1). Six in 10 Americans live with at least 1 chronic condition, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, or diabetes (2). Chronic diseases are also the leading causes of disability in the US and the leading drivers of the nation’s $3.8 trillion annual health care costs (2,3).

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in enormous personal and societal losses, with more than half a million lives lost (4). COVID-19 is a disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that can result in respiratory distress. In addition to the physical toll, the emotional impact has yet to be fully understood. For those with chronic disease, the impact has been particularly profound (5,6). Heart disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and obesity are all conditions that increase the risk for severe illness from COVID-19 (7). Other factors, including smoking and pregnancy, also increase the risk (7). Finally, in addition to COVID-19–related deaths since February 1, 2020, an increase in deaths has been observed among people with dementia, circulatory diseases, and diabetes among other causes (8). This increase could reflect undercounting COVID-19 deaths or indirect effects of the virus, such as underutilization of, or stresses on, the health care system (8).

Some populations, including those with low socioeconomic status and those of certain racial and ethnic groups, including African American, Hispanic, and Native American, have a disproportionate burden of chronic disease, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and COVID-19 diagnosis, hospitalization, and mortality (9). These populations are at higher risk because of exposure to suboptimal social determinants of health (SDoH). SDoH are factors that influence health where people live, work, and play, and can create obstacles that contribute to inequities. Education, type of employment, poor or no access to health care, lack of safe and affordable housing, lack of access to healthy food, structural racism, and other conditions all affect a wide range of health outcomes (10–12). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing health inequities and laid bare underlying root causes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had direct and indirect effects on people with chronic disease. In addition to morbidity and mortality, high rates of community spread and various mitigation efforts, including stay-at-home recommendations, have disrupted lives and created social and economic hardships (13). This pandemic has also raised concerns about safely accessing health care (14) and has reduced the ability to prevent or control chronic disease. This essay discusses the impact that these challenges have or could have on people with chronic disease now and in the future. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 should help the public health and health care communities effectively improve health outcomes.

The challenges we face as public health professionals are divided into 3 categories. The first category involves the current effects of COVID-19 on those with, or at risk for, chronic diseases and those at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness. Inherent in this category is the need for balance between protecting people with chronic diseases from COVID-19 while assuring they can engage in disease prevention, manage their conditions effectively, and safely receive needed health care.

The second category is the postpandemic impact of COVID-19 on the prevention, identification, and management of chronic disease. COVID-19 has resulted in decreases of many types of health care utilization (15), ranging from preventive care to chronic disease management and even emergency care (16). As of June 2020, 4 in 10 adults surveyed reported delaying or avoiding routine or emergent medical care because of the pandemic (14). Cancer screenings, for example, dropped during the pandemic (17). Decreases in screening have resulted in the diagnoses of fewer cancers and precancers (18), and modeling studies have estimated that delayed screening and treatment for breast and colorectal cancer could result in almost 10,000 preventable deaths in the United States (19). We have lost ground in prevention across the chronic disease spectrum and in other areas, including pediatric immunization (20), mental health (21,22), and substance abuse (21,22).

Some challenges with health care utilization may be improving, but improvement has not been consistent across all health care visit types, providers, patients, or communities (15). Questions about the impact of the pandemic on chronic disease include:

What diseases have been missed or allowed to worsen?

What is the status of prevention and disease management efforts?

Have prevention and disease management efforts been affected by concerns such as job loss, loss of insurance, lack of access to healthy food, or loss of places and opportunities to be physically active?

How have effects of the pandemic on health care systems (staff reductions, health practice closures, disrupted services) (23) and public health organizations’ deployment of personnel away from ongoing chronic disease prevention efforts been experienced nationally?

The effects of COVID-19, whether negative or positive, on health care and public health systems will certainly affect those with chronic disease. To fully understand the consequences of the pandemic, we need to assess its overall impact on incidence, management, and outcomes of chronic disease. This is particularly salient in communities where health inequities are already rampant or communities that are remote or underserved. Will our postpandemic response be strong enough to mitigate the exacerbation of inequities that have occurred? Can public health agencies effectively build trust in science and community health care systems where trust might never have been fully established or where it has been lost?

The third category relates to the long-term COVID-19 sequelae, both as a disease entity and from a population perspective. Has COVID-19 created a new group of patients with chronic diseases, neurologic or psychiatric conditions, diabetes, or effects on the heart, lungs, kidneys, or other organs (24)? Has it worsened existing conditions or caused additional chronic disease? And, at the population level, have the incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases increased because of pandemic-related health behaviors or other challenges, such as decreased food and nutrition security?

Given the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines and the coming end of the pandemic, this is an important time to examine the impact of COVID-19. Solutions at all levels are needed to improve health outcomes and lessen health inequities among people with or at risk for chronic disease. Solutions are likely to include increasing awareness about prevention and care during and after the pandemic, building or enhancing cross-organizational and cross-sector partnerships, innovating to address identified gaps, and addressing SDoH to improve health and achieve equity. So, what can be done?

Additional focus is required on several aspects of awareness about the impact of COVID-19. First, public health and health care practitioners need to allay people’s fears and help them safely return to health care. We need to reemphasize chronic disease prevention and care, explain how to safely access care, and convey the host of mitigation efforts made by health care systems, providers, and public health to ensure that environments are safe (eg, mask requirements, social distancing). Emphasis on safety and mitigation applies to both disease prevention (such as encouraging healthy nutrition and physical activity, screening for cancer and other conditions, and getting oral health care) and disease management (eg, educating patients about medications to control hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and other chronic conditions). Efforts must also include helping those with chronic diseases obtain access to and gain confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine. Given current community rates of COVID-19 and the need to reenter care after the height of the pandemic, information can help patients make informed choices about the need for in-person care, communication at a distance, or temporary delays in care that is more discretionary.

To garner support to help affected communities, there is a need to build awareness about how COVID-19 has disproportionately affected particular communities, including the unequal distribution of disease, morbidity, mortality, and resources, such as access to vaccines. Awareness is dependent on access to data at the granular geographic level, including information on the burden of chronic disease and the status of SDoH. Communities need data to effectively address health inequities in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Public health plays a significant role in addressing health behaviors (healthy eating, physical activity, avoiding tobacco and other substance use) and community solutions to address SDoH that impact prevention and control of chronic disease. Collaborations at both the individual and system levels, however, are required for success. Collaborative partners include other government and nongovernmental organizations, health care organizations, insurers, nonprofit organizations, community and faith-based groups, schools, businesses, and others. Coalitions and community groups are critical change agents. They have worked with local health departments and others to identify solutions, bring residents into discussions, and implement action. We can learn from them about how best to build trust and foster the innovation they are leading. Solutions must also include direct discussions with residents in affected communities to understand their priorities and effectively address their concerns. These relationships are particularly salient to address SDoH. These factors have been amplified as a direct consequence of COVID-19 and will require a multisector approach to problem solving.

To achieve this will require building trust in both the health care system and the public health system. The pandemic has taken a toll on an already fragile relationship between communities and public health and health care institutions where trust has been absent or insufficient. To begin to address the trust challenge will require investments in outreach, engagement, and transparency. Conversations need to be bidirectional, long-term, and conducted by people who are trusted, who are respectful, and who can identify with affected populations.

Creative solutions are needed to engage populations and promote resiliency among those who are disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Efforts that need to be further developed and brought to scale include the following:

Leveraging technology to expand the reach of health care and health promotion (eg, telemedicine, virtual program delivery, wearables, mobile device applications).

Providing more services in community settings, as is increasingly modeled in the National Diabetes Prevention Program (25).

Using community health workers to assist in assessing current conditions and connecting to community resources.

Further enhancing approaches to increase access to and convenience of services (eg, increasing access to home screenings, such as cancer screening) or monitoring (eg, home blood pressure monitoring) where appropriate.

Health care approaches, such as telemedicine, have expanded greatly during the pandemic and seem likely to continue expansion over time. As these and related efforts grow, practitioners will need to ensure that existing disparities are not magnified. Care is needed to ensure that those with the highest health needs can access services. For example, are technological solutions easily accessible, available in multiple languages, compatible with readily available hardware options, such as telephones rather than laptops? Are culturally appropriate resources available to help people use and value these technologies? In addition, computer availability and internet access will need to be expanded. Challenges such as unemployment, food insecurity, limited transportation, substance abuse, and social isolation will require a multisector effort uniquely adapted to local contexts. To begin, health equity–focused policy analyses and health impact assessments will help policy makers understand better how proposed SDoH-related action might either exacerbate or mitigate chronic disease inequities. These actions will help us develop a deeper understanding of what individual communities need to mobilize and build resilience for the future. We face serious public health and population health concerns that should be the focus in the near term — particularly as equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines is a consideration in every community across the nation. We clearly have an enormous amount of work to do as we enter recovery from the pandemic, but with recovery comes enormous opportunity.

A challenge related to long-term COVID-19 sequelae is that we do not know yet the extent that COVID-19 exacerbates chronic disease, causes chronic disease, or will be determined a chronic disease unto itself. Those interested in chronic disease prevention and management need to follow the research to understand better the role they will play with this emerging situation. Long-term studies and longitudinal surveillance will help clarify these issues, and there is much research to be done. The duty of the public health community is to help ensure that the most important issues from the perspectives of patients, providers, health care, and public health systems are addressed; that potential solutions are developed and tested; and that eventual solutions are delivered where they are needed most.

As the US enters the next phase of pandemic response, the work of National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is evolving to address health inequities and drive toward health equity with a multipronged approach. This approach includes enhanced access to data at the local level, a focus on SDoH including a shift in the Notice of Funding Opportunity process that emphasizes a health equity lens, and an expansion of partnerships and communications.

Placing data in the hands of communities is critical for local coalitions to determine their burden of chronic disease and COVID-19, their access to resources, and the best policies and practices to implement. Data will be useful for local public health, governments, and health care systems, but can also help human services, planning, and economic development organizations. An initial step is making available data from the PLACES Project (26), which provides data on 27 chronic disease measures at the census tract level, allowing communities to understand their own chronic disease burden. In addition, modules on SDoH are in development to enhance NCCDPHP data surveillance systems. This will increase the ability to overlay chronic disease data and SDoH data at the community level. The need is also a great for core SDoH measures that allow comparisons of related outcomes across communities. NCCDPHP can augment this effort by contributing to and amplifying the SDoH measures identified for Healthy People 2030 (27).

NCCDPHP is focusing on supporting and stimulating SDoH efforts by concentrating on 5 major areas: built environment, social connectedness, food and nutrition security, tobacco policies, and connections to clinical care. For example, SDoH are the foci of recent Notices of Funding Opportunities (available at https://www.grants.gov). NCCDPHP supports multisector partnerships in numerous funding announcements and launched a joint effort with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the National Association of County and City Health Officials to identify best practices in multisector collaboration to address SDoH (28). Evidence will help build a standard for success to support local coalitions in their work. States and local communities are sites of innovation, and promoting lessons learned can help build broader efforts. To address urgent needs and facilitate change, NCCDPHP must link with other sectors outside of public health and health care. The work to evaluate these efforts and determine the most effective strategies to address SDoH, therefore, will be integrated fully into NCCDPHP.

An expansion of the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Program (29) and other programs that address health inequities will help to target resources where they are needed most. REACH and a recently released investment in community health workers (30) demonstrate NCCDPHP’s commitment to connecting with populations that are disproportionately affected by chronic disease at the local level. These efforts are aimed at addressing the ramifications of COVID-19 while also amplifying chronic disease prevention efforts. NCCDPHP also intends to enhance the use of a health equity lens, among other approaches, to determine the best use of resources and to help assess outcomes in all programmatic activities.

Finally, communication about the impact of COVID-19 on chronic disease, returning to care, and the extent of health inequities is critical to building trust. Efforts under way include a television and digital media campaign aiming to encourage those with chronic disease to return safely to care (31). In addition to expanding work with partner organizations, both external and internal to government, NCCDPHP will embrace new ways of garnering input from affected communities. Successes and failures experienced by communities during the pandemic will continue to be of the utmost importance to NCCDPHP. In addition, important insights gained from working closely with affected communities will help NCCDPHP continually refine its national chronic disease prevention and control goals and objectives. Activities related to SDoH and health equity, data, and communication will address difficult questions now and into the future. These efforts can only be successful with collaboration and partnerships across multiple sectors.

The impact of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, on people with or at risk for chronic disease cannot be overstated. COVID-19 has impeded chronic disease prevention and disrupted disease management. The problems and solutions outlined here are critically important to help those committed to chronic disease prevention and intervention to identify ways forward.

NCCDPHP is adjusting, preparing, and implementing multiple strategies to address the future. Although the work will be challenging, opportunities abound. NCCDPHP is committed to working with the health care community and a variety of partners at federal, state, and local levels to help address the realities of the post-COVID era.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. No copyrighted materials were used in the preparation of this essay.

Corresponding Author: Karen A. Hacker, MD, MPH, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 4770 Buford Highway NE, Atlanta, GA 30341. Telephone: 404-632-5062. Email: [email protected] .

Author Affiliations: 1 National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Leading causes of death. Updated March 1, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Buttorff C, Teague R, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2019 highlights. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/highlights.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Rosenthal N, Cao Z, Gundrum J, Sianis J, Safo S. Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2029058. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open 2021;1:e2036103[REMOVED IF= FIELD] CrossRef external icon

- Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584(7821):430–6. CrossRef external icon

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with certain medical conditions. Updated March 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19. Updated April 7, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Updated March 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. Updated February 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, Baral S, Mercer L, Beyrer C, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on Black communities. Ann Epidemiol 2020;47:37–44. CrossRef external icon

- Cordes J, Castro MC. Spatial analysis of COVID-19 clusters and contextual factors in New York City. Spat Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol 2020;34:100355. CrossRef external icon

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg 2020;78:185–93. CrossRef external icon

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, Salah Z, Shakya I, Thierry JM, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns — United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(36):1250–7. CrossRef external icon

- Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider EC, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient care: visits return to prepandemic levels, but not for all providers and patients. 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/oct/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-care-visits-return-prepandemic-levels. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits — United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(23):699–704. CrossRef external icon

- London JW, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, Sankey P, McNair C. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer-related patient encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4(4):657–65. CrossRef external icon

- Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 2021;7(3):458–60. CrossRef external icon

- Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science 2020;368(6497):1290. CrossRef external icon

- Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, Kharbanda EO, Daley MF, Galloway L, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(19):591–3. CrossRef external icon

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69:1049–1057. CrossRef external icon

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Wiley JF, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW. Follow-up survey of US adult reports of mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(2):e2037665. CrossRef external icon

- Song Z, Giuriato M, Lillehaugen T, Altman W, Horn DM, Phillips RS, et al. Economic and clinical impact of COVID-19 on provider practices in Massachusetts. New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery . Published online September 11, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0441. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Rubin R. As their numbers grow, COVID-19 long haulers stump experts. JAMA 2020;324(14):1381–3. CrossRef external icon

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Prevention Program: working together to prevent diabetes. Updated August 10, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Population Health. PLACES: local data for better health. Updated December 8, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/places/about/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2030: social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health community pilots. Updated March 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/programs-impact/SDoH/community-pilots.htm. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Racial and ethnic approaches to community health. Updated October 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/state-local-programs/reach/index.htm. Accessed April 8, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Community health workers for COVID response and resilient communities (CCR) CDC-RFA-DP21-2109. Updated April 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/programs-impact/nofo/covid-response.htm. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- The National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. Your health beyond COVID-19 matters! https://yourhealthbeyondcovid.org. Accessed April 29, 2021.

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 74, Issue 11

- The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1294-6851 Clare Bambra 1 ,

- Ryan Riordan 2 ,

- John Ford 2 ,

- Fiona Matthews 1

- 1 Population Health Sciences Institute, Newcastle University Institute for Health and Society , Newcastle upon Tyne , UK

- 2 School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge University , Cambridge , UK

- Correspondence to Clare Bambra, Population Health Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP, UK; clare.bambra{at}newcastle.ac.uk

This essay examines the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for health inequalities. It outlines historical and contemporary evidence of inequalities in pandemics—drawing on international research into the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, the H1N1 outbreak of 2009 and the emerging international estimates of socio-economic, ethnic and geographical inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. It then examines how these inequalities in COVID-19 are related to existing inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health, arguing that we are experiencing a syndemic pandemic . It then explores the potential consequences for health inequalities of the lockdown measures implemented internationally as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the likely unequal impacts of the economic crisis. The essay concludes by reflecting on the longer-term public health policy responses needed to ensure that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations.

- DEPRIVATION

- Health inequalities

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ's website terms and conditions for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

INTRODUCTION

In 1931, Edgar Sydenstricker outlined inequalities by socio-economic class in the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic in America, reporting a significantly higher incidence among the working classes. 1 This challenged the widely held popular and scientific consensus of the time which held that ‘the flu hit the rich and the poor alike’. 2 In the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been similar claims made by politicians and the media - that we are ‘all in it together’ and that the COVID-19 virus ‘does not discriminate’. 3 This essay aims to dispel this myth of COVID-19 as a socially neutral disease, by discussing how, just as 100 years ago, there are inequalities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates—reflecting existing unequal experiences of chronic diseases and the social determinants of health. The essay is structured in three main parts. Part 1 examines historical and contemporary evidence of inequalities in pandemics—drawing on international research into the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, the H1N1 outbreak of 2009 and the emerging international estimates of socio-economic, ethnic and geographical inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. Part 2 examines how these inequalities in COVID-19 are related to existing inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health, arguing that we are experiencing a syndemic pandemic . In Part 3, we explore the potential consequences for health inequalities of the lockdown measures implemented internationally as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the likely unequal impacts of the economic crisis. The essay concludes by reflecting on the longer-term public health policy responses needed to ensure that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations.

PART 1. HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY EVIDENCE OF INEQUALITIES IN PANDEMICS

More recent studies have confirmed Sydenstricker’s early findings: there were significant inequalities in the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. The international literature demonstrates that there were inequalities in prevalence and mortality rates: between high-income and low-income countries, more and less affluent neighbourhoods, higher and lower socio-economic groups, and urban and rural areas. For example, India had a mortality rate 40 times higher than Denmark and the mortality rate was 20 times higher in some South American countries than in Europe. 4 In Norway, mortality rates were highest among the working-class districts of Oslo 5 ; in the USA, they were highest among the unemployed and the urban poor in Chicago, 6 and across Sweden, there were inequalities in mortality between the highest and lowest occupational classes—particularly among men. 7 In contrast, countries with smaller pre-existing social and economic inequalities, such as New Zealand, did not experience any socio-economic inequalities in mortality. 8 9 An urban–rural effect was also observed in the 1918 influenza pandemic whereby, for example, in England and Wales, the mortality was 30%–40% higher in urban areas. 10 There is also some evidence from the USA that the pandemic had long-term impacts on inequalities in child health and development. 11

Several studies have also demonstrated inequalities in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. For example, globally, Mexico experienced a higher mortality rate than that in higher-income countries. 12 In terms of socio-economic inequalities, themortality rate from H1N1 in the most deprived neighbourhoods of England was three times higher than in the least deprived. 13 It was also higher in urban compared to rural areas. 13 Similarly, a Canadian study in Ontario found that hospitalisation rates for H1N1 were associated with lower educational attainment and living in a high deprivation neighbourhood. 14 Another study found positive associations between people with financial issues (eg, financial barriers to healthcare access) and influenza-like illnesses during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in the USA. 15 Various studies on cyclical winter influenza in North America have also found associations between mortality, morbidity and symptom severity and socio-economic status among adults and children. 16 17

Just as in 1918 and 2009, evidence of social inequalities is already emerging in relation to COVID-19 from Spain, the USA and the UK. Intermediate data published by the Catalonian government in Spain suggest that the rate of COVID-19 infection is six or seven times higher in the most deprived areas of the region compared to the least deprived. 18 Similarly, in preliminary USA analysis, Chen and Krieger (2020) found area-level socio-spatial gradients in confirmed cases in Illinois and positive test results in New York City, with dramatically increased risk of death observed among residents of the most disadvantaged counties. 19 With regard to ethnic inequalities in COVID-19, data from England and Wales have found that people who are black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) accounted for 34.5% of 4873 critically ill COVID-19 patients (in the period ending April 16, 2020) and much higher than the 11.5% seen for viral pneumonia between 2017 and 2019. 20 Only 14% of the population of England and Wales are from BAME backgrounds. Even more stark is the data on racial inequalities in COVID-19 infections and deaths that are being released by various states and municipalities in the USA. For example, in Chicago (in the period ending April 17, 2020), 59.2% of COVID-19 deaths were among black residents and the COVID-19 mortality rate for black Chicagoans was 34.8 per 100 000 population compared to 8.2 per 100 000 population among white residents. 21 There will likely be an interaction of race and socio-economic inequalities, demonstrating the intersectionality of multiple aspects of disadvantage coalescing to further compound illness and increase the risk of mortality. 22

PART 2. THE SYNDEMIC OF COVID-19, CHRONIC DISEASE AND THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

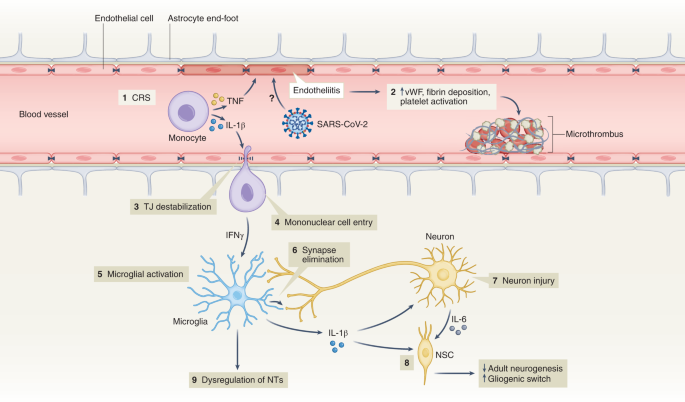

The COVID-19 pandemic is occurring against a backdrop of social and economic inequalities in existing non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as well as inequalities in the social determinants of health. Inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates are therefore arising as a result of a syndemic of COVID-19, inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health. The prevalence and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is magnified because of the pre-existing epidemics of chronic disease—which are themselves socially patterned and associated with the social determinants of health. The concept of a syndemic was originally developed by Merrill Singer to help understand the relationships between HIV/AIDS, substance use and violence in the USA in the 1990s. 23 A syndemic exists when risk factors or comorbidities are intertwined, interactive and cumulative—adversely exacerbating the disease burden and additively increasing its negative effects: ‘A syndemic is a set of closely intertwined and mutual enhancing health problems that significantly affect the overall health status of a population within the context of a perpetuating configuration of noxious social conditions’ [24 p13]. We argue that for the most disadvantaged communities, COVID-19 is experienced as a syndemic—a co-occurring, synergistic pandemic that interacts with and exacerbates their existing NCDs and social conditions ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The syndemic of COVID-19, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the social determinants of health (adapted from Singer 23 and Dahlgren and Whitehead 25 ).

Minority ethnic groups, people living in areas of higher socio-economic deprivation, those in poverty and other marginalised groups (such as homeless people, prisoners and street-based sex workers) generally have a greater number of coexisting NCDs, which are more severe and experienced at at a younger age. For example, people living in more socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods and minority ethnic groups have higher rates of almost all of the known underlying clinical risk factors that increase the severity and mortality of COVID-19, including hypertension, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, liver disease, renal disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity and smoking. 26–29 Likewise, minority ethnic groups in Europe, the USA and other high-income countries experience higher rates of the key COVID-19 risk factors, including coronary heart disease and diabetes. 28 Similarly, the Gypsy/Roma community—one of the most marginalised minority groups in Europe—has a smoking rate that is two to three times the European average and increased rates of respiratory diseases (such as COPD) and other COVID-19 risk factors. 29

These inequalities in chronic conditions arise as a result of inequalities in exposure to the social determinants of health: the conditions in which people ‘live, work, grow and age’ including working conditions, unemployment, access to essential goods and services (eg, water, sanitation and food), housing and access to healthcare. 25 30 By way of example, there are considerable occupational inequalities in exposure to adverse working conditions (eg, ergonomic hazards, repetitive work, long hours, shift work, low wages, job insecurity)—they are concentrated in lower-skill jobs. These working conditions are associated with increased risks of respiratory diseases, certain cancers, musculoskeletal disease, hypertension, stress and anxiety. 31 In addition to these long-term exposures, inequalities in working conditions may well be impacting the unequal distribution of the COVID-19 disease burden. For example, lower-paid workers (where BAME groups are disproportionately represented)—particularly in the service sector (eg, food, cleaning or delivery services)—are much more likely to be designated as key workers and thereby are still required to go to work and rely on public transport for doing so. All these increase their exposure to the virus.

Similarly, access to healthcare is lower in disadvantaged and marginalised communities—even in universal healthcare systems. 32 In England, the number of patients per general practitioner is 15% higher in the most deprived areas than that in the least deprived areas. 33 Medical care is even more unequally distributed in countries such as the USA where around 33 million Americans—from the most disadvantaged and marginalised groups—have insufficient or no healthcare insurance. 27 This reduced access to healthcare—before and during the outbreak—contributes to inequalities in chronic disease and is also likely to lead to worse outcomes from COVID-19 in more disadvantaged areas and marginalised communities. People with existing chronic conditions (eg, cancer or cardiovascular disease (CVD)) are less likely to receive treatment and diagnosis as health services are overwhelmed by dealing with the pandemic.

Housing is also an important factor in driving health inequalities. 34 For example, exposure to poor quality housing is associated with certain health outcomes, for example, damp housing can lead to respiratory diseases such as asthma while overcrowding can result in higher infection rates and increased risk of injury from household accidents. 34 Housing also impacts health inequalities materially through costs (eg, as a result of high rents) and psychosocially through insecurity (eg, short-term leases). 34 Lower socio-economic groups have a higher exposure to poor quality or unaffordable, insecure housing and therefore have a higher rate of negative health consequences. 35 These inequalities in housing conditions may also be contributing to inequalities in COVID-19. For example, deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to contain houses of multiple occupation and smaller houses with a lack of outside space, as well as have higher population densities (particularly in deprived urban areas) and lower access to communal green space. 27 These will likely increase COVID-19 transmission rates—as was the case with H1N1 where strong associations were found with urbanity. 13

The social determinants of health also work to make people from marginalised communities more vulnerable to infection from COVID-19—even when they have no underlying health conditions. Decades of research into the psychosocial determinants of health have found that the chronic stress of material and psychological deprivation is associated with immunosuppression. 36 Psychosocial feelings of subordination or inferiority as a result of occupying a low position on the social hierarchy stimulate physiological stress responses (eg, raised cortisol levels), which, when prolonged (chronic), can have long-term adverse consequences for physical and mental health. 37 By way of example, studies have found consistent associations between low job status (eg, low control and high demands), stress-related morbidity and various chronic conditions including coronary heart disease, hypertension, obesity, musculoskeletal conditions, and psychological ill health. 38 Likewise, there is increasing evidence that living in disadvantaged environments may produce a sense of powerlessness and collective threat among residents, leading to chronic stressors that, in time, damage health. 39 Studies have also confirmed that adverse psychosocial circumstances increase susceptibility—influencing the onset, course and outcome of infectious diseases—including respiratory diseases like COVID-19. 40

PART 3. THE GREAT LOCKDOWN: THE COVID-19 ECONOMIC CRISIS AND HEALTH INEQUALITIES

The impact of COVID-19 on health inequalities will not just be in terms of virus-related infection and mortality, but also in terms of the health consequences of the policy responses undertaken in most countries. While traditional public health surveillance measures of contact tracing and individual quarantine were successfully pursued by some countries (most notably by South Korea and Germany) as a way of tackling the virus in the early stages, most other countries failed to do so, and governments worldwide were eventually forced to implement mass quarantine measures—in the form of lockdowns. These state-imposed restrictions—usually requiring the government to take on emergency powers—have been implemented to varying levels of severity, but all have in common a significant increase in social isolation and confinement within the home and immediate neighbourhood. The aims of these unprecedented measures are to increase social and physical distancing and thereby reduce the effective reproduction number (eR0) of the virus to less than 1. For example, in the UK, individuals were only allowed to leave the home for one of four reasons (shopping for basic necessities, exercise, medical needs, travelling for work purposes). Following Wuhan province in China, most of the lockdowns have been implemented for 8 to 12 weeks.

The immediate pathways through which the COVID-19 emergency lockdowns are likely to have unequal health impacts are multiple—ranging from unequal experiences of lockdown (eg, due to job and income loss, overcrowding, urbanity, access to green space, key worker roles), how the lockdown itself is shaping the social determinants of health (eg, reduced access to healthcare services for non-COVID-19 reasons as the system is overwhelmed by the pandemic) and inequalities in the immediate health impacts of the lockdown (eg, in mental health and gender-based violence). However, arguably, the longer-term and largest consequences of the ‘great lockdown’ for health inequalities will be through political and economic pathways ( figure 1 ). The world economy has been severely impacted by COVID-19—with almost daily record stock market falls, oil prices have crashed and there are record levels of unemployment (eg, 5.2 million people filed for unemployment benefit in just 1 week in April 2020 in the USA), despite the unprecedented interventionist measures undertaken by some governments and central banks—such as the £300 billion injection by the UK government to support workers and businesses. The pandemic has slowed China’s economy with a predicted loss of $65 billion as a minimum in the first quarter of 2020. Economists fear that the economic impact will be far greater than the financial crisis of 2007/2008, and they say that it is likely to be worse in depth than the Great Depression of the 1930s. Just like the 1918 influenza pandemic (which had severe impacts on economic performance and increased poverty rates), the COVID-19 crisis will have huge economic, social and—ultimately—health consequences.

Previous research has found that sudden economic shocks (like the collapse of communism in the early 1990s and the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 41 ) lead to increases in morbidity, mental ill health, suicide and death from alcohol and substance use. For example, following the GFC, worldwide an excess of suicides were observed in the USA, England, Spain and Ireland. 42 There is also evidence of other increases in poor mental health after the GFC including self-harm and psychiatric morbidity. 41 42 These health impacts were not shared equally though—areas of the UK with higher unemployment rates had greater increases in suicide rates and inequalities in mental health increased with people living in the most deprived areas experiencing the largest increases in psychiatric morbidity and self-harm. 43 Further, unemployment (and its well-established negative health impacts in terms of morbidity and mortality 38 ) is disproportionately experienced by those with lower skills or who live in less buoyant local labour markets. 27 So, the health consequences of the COVID-19 economic crisis are likely to be similarly unequally distributed—exacerbating heath inequalities.

However, the effects of recessions on health inequalities also vary by public policy response with countries such as the UK, Greece, Italy and Spain who imposed austerity (significant cuts in health and social protection budgets) after the GFC experiencing worse population health effects than those countries such as Germany, Iceland and Sweden who opted to maintain public spending and social safety nets. 41 Indeed, research has found that countries with higher rates of social protection (such as Sweden) did not experience increases in health inequalities during the 1990s economic recession. 44 Similarly, old-age pensions in the UK were protected from austerity cuts after the GFC and research has suggested that this prevented health inequalities increasing amongst the older population. 45 These findings are in keeping with previous studies of the effects of public sector and welfare state contractions and expansions on trends in health inequalities in the UK, USA and New Zealand. 27 46–49 For example, inequalities in premature mortality and infant mortality by income and ethnicity in the USA decreased during the period of welfare expansion in the USA (‘war on poverty’ era 1966 to 1980), but they increased again during the Reagan–Bush period (1980–2002) when welfare services and healthcare coverage were cut. 46 Similarly, in England, inequalities in infant mortality rates reduced as child poverty decreased in a period of public sector and welfare state expansion (from 2000 to 2010), 47 but increased again when austerity was implemented and child poverty rates increased (from 2010 to 2017). 48

So this essay makes for grim reading for researchers, practitioners and policymakers concerned with health inequalities. Historically, pandemics have been experienced unequally with higher rates of infection and mortality among the most disadvantaged communities—particularly in more socially unequal countries. 8 9 Emerging evidence from a variety of countries suggests that these inequalities are being mirrored today in the COVID-19 pandemic. Both then and now, these inequalities have emerged through the syndemic nature of COVID-19—as it interacts with and exacerbates existing social inequalities in chronic disease and the social determinants of health. COVID-19 has laid bare our longstanding social, economic and political inequalities - even before the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy amongst the poorest groups was already declining in the UK and the USA and health inequalities in some European countries have been increasing over the last decade. 50 It seems likely that there will be a post-COVID-19 global economic slump—which could make the health equity situation even worse, particularly if health-damaging policies of austerity are implemented again. It is vital that this time, the right public policy responses (such as expanding social protection and public services and pursuing green inclusive growth strategies) are undertaken so that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations. Public health must ‘win the peace’ as well as the ‘war’.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chris Orton from the Cartographic Unit, Department of Geography, Durham University, for his assistance with the graphics for figure 1 .

- Sydenstricker E

- Lawrence AJ

- SkyNews (27/03/20)

- Murray CJ ,

- Chin B , et al.

- Mamelund SE

- Grantz KH ,

- Salje H , et al.

- Bengtsson T ,

- Summers JA ,

- Stanley J ,

- Baker MG , et al.

- Chowell G ,

- Bettencourt LMA ,

- Johnson N , et al.

- Majia LSF , et al.

- Rutter PD ,

- Mytton OT ,

- Mak M , et al.

- Lowcock EC ,

- Rosella LC ,

- Foisy J , et al.

- Biggerstaff M ,

- Reed C , et al.

- Yousey-hindes K ,

- Crighton EJ ,

- Elliott SJ ,

- Moineddin R , et al.

- Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Assessment (AQuAS)

- Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre

- Chicago Department of Public Health

- Gkiouleka A ,

- Beckfield J , et al.

- Dahlgren G ,

- Whitehead M

- Zhang X , et al.

- Public health England

- European commission

- WHO - World Health. Organisation

- Copeland A ,

- Kasim A , et al.

- Lacobucci G

- Petticrew M ,

- Bambra C , et al.

- McNamara CL ,

- Thomson KH , et al.

- Segerstrom SC ,

- Whitehead M ,

- Pennington A ,

- Orton L , et al.

- Stuckler D ,

- Corcoran P ,

- Griffin E ,

- Arensman E , et al.

- Kinderman P ,

- Whitehead P

- Nylen L , et al.

- Mattheys K , et al.

- Krieger N ,

- Rehkopf DH ,

- Chen JT , et al.

- Robinson T ,

- Norman P , et al.

- Taylor-Robinson D ,

- Wickham S , et al.

- Beckfield J ,

- Forster T ,

- Kentikelenis A ,

Twitter Clare Bambra @ProfBambra.

Funding CB is a senior investigator in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC North East and North Cumbria, NIHR Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science, NIHR School of Public Health Research, the UK Prevention Research Partnership SIPHER: Systems science in Public Health and Health Economics Research consortium, and the Norwegian Research Council Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research. JF is a senior investigator in the NIHR ARC East of England. FM is a senior investigator in the NIHR Policy Research Unit in Ageing and Frailty. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Competing interests We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Data sharing statement Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Protests boil over on college campuses.

Lauren Camera April 22, 2024

Supporting Low-Income College Applicants

Shavar Jeffries April 16, 2024

Supporting Black Women in Higher Ed

Zainab Okolo April 15, 2024

Law Schools With the Highest LSATs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 11, 2024

Today NAIA, Tomorrow Title IX?

Lauren Camera April 9, 2024

Grad School Housing Options

Anayat Durrani April 9, 2024

How to Decide if an MBA Is Worth it

Sarah Wood March 27, 2024

What to Wear to a Graduation

LaMont Jones, Jr. March 27, 2024

FAFSA Delays Alarm Families, Colleges

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 03 October 2022

How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects

- Brenda W. J. H. Penninx ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7779-9672 1 , 2 ,

- Michael E. Benros ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4939-9465 3 , 4 ,

- Robyn S. Klein 5 &

- Christiaan H. Vinkers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3698-0744 1 , 2

Nature Medicine volume 28 , pages 2027–2037 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

122 Citations

491 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Infectious diseases

- Neurological manifestations

- Psychiatric disorders

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has threatened global mental health, both indirectly via disruptive societal changes and directly via neuropsychiatric sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite a small increase in self-reported mental health problems, this has (so far) not translated into objectively measurable increased rates of mental disorders, self-harm or suicide rates at the population level. This could suggest effective resilience and adaptation, but there is substantial heterogeneity among subgroups, and time-lag effects may also exist. With regard to COVID-19 itself, both acute and post-acute neuropsychiatric sequelae have become apparent, with high prevalence of fatigue, cognitive impairments and anxiety and depressive symptoms, even months after infection. To understand how COVID-19 continues to shape mental health in the longer term, fine-grained, well-controlled longitudinal data at the (neuro)biological, individual and societal levels remain essential. For future pandemics, policymakers and clinicians should prioritize mental health from the outset to identify and protect those at risk and promote long-term resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

A longitudinal analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson, … CLSA team

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Surapon Nochaiwong, Chidchanok Ruengorn, … Tinakon Wongpakaran

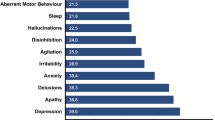

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and carer mental health: an international multicentre study

Grace Wei, Janine Diehl-Schmid, … Fiona Kumfor

In 2019, the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), with 590 million confirmed cases and 6.4 million deaths worldwide as of August 2022 (ref. 1 ). To contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) across the globe, many national and local governments implemented often drastic restrictions as preventive health measures. Consequently, the pandemic has not only led to potential SARS-CoV-2 exposure, infection and disease but also to a wide range of policies consisting of mask requirements, quarantines, lockdowns, physical distancing and closure of non-essential services, with unprecedented societal and economic consequences.

As the world is slowly gaining control over COVID-19, it is timely and essential to ask how the pandemic has affected global mental health. Indirect effects include stress-evoking and disruptive societal changes, which may detrimentally affect mental health in the general population. Direct effects include SARS-CoV-2-mediated acute and long-lasting neuropsychiatric sequelae in affected individuals that occur during primary infection or as part of post-acute COVID syndrome (PACS) 2 —defined as symptoms lasting beyond 3–4 weeks that can involve multiple organs, including the brain. Several terminologies exist for characterizing the effects of COVID-19. PACS also includes late sequalae that constitute a clinical diagnosis of ‘long COVID’ where persistent symptoms are still present 12 weeks after initial infection and cannot be attributed to other conditions 3 .

Here we review both the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on mental health. First, we summarize empirical findings on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted population mental health, through mental health symptom reports, mental disorder prevalence and suicide rates. Second, we describe mental health sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection and COVID-19 disease (for example, cognitive impairment, fatigue and affective symptoms). For this, we use the term PACS for neuropsychiatric consequences beyond the acute period, and will also describe the underlying neurobiological impact on brain structure and function. We conclude with a discussion of the lessons learned and knowledge gaps that need to be further addressed.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population mental health

Independent of the pandemic, mental disorders are known to be prevalent globally and cause a very high disease burden 4 , 5 , 6 . For most common mental disorders (including major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorder), environmental stressors play a major etiological role. Disruptive and unpredictable pandemic circumstances may increase distress levels in many individuals, at least temporarily. However, it should be noted that the pandemic not only resulted in negative stressors but also in positive and potentially buffering changes for some, including a better work–life balance, improved family dynamics and enhanced feelings of closeness 7 .

Awareness of the potential mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is reflected in the more than 35,000 papers published on this topic. However, this rapid research output comes with a cost: conclusions from many papers are limited due to small sample sizes, convenience sampling with unclear generalizability implications and lack of a pre-COVID-19 comparison. More reliable estimates of the pandemic mental health impact come from studies with longitudinal or time-series designs that include a pre-pandemic comparison. In our description of the evidence, we, therefore, explicitly focused on findings from meta-analyses that include longitudinal studies with data before the pandemic, as recently identified through a systematic literature search by the WHO 8 .

Self-reported mental health problems

Most studies examining the pandemic impact on mental health used online data collection methods to measure self-reported common indicators, such as mood, anxiety or general psychological distress. Pooled prevalence estimates of clinically relevant high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic range widely—between 20% and 35% 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 —but are difficult to interpret due to large methodological and sample heterogeneity. It also is important to note that high levels of self-reported mental health problems identify increased vulnerability and signal an increased risk for mental disorders, but they do not equal clinical caseness levels, which are generally much lower.

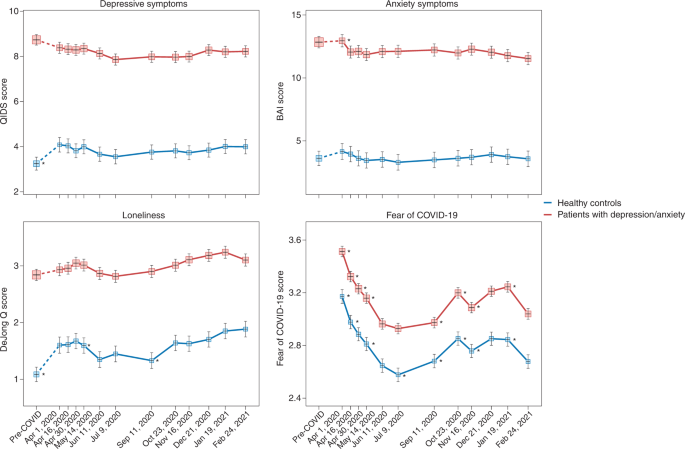

Three meta-analyses, pooling data from between 11 and 61 studies and involving ~50,000 individuals or more 13 , 14 , 15 , compared levels of self-reported mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic with those before the pandemic. Meta-analyses report on pooled effect sizes—that is, weighted averages of study-level effect sizes; these are generally considered small when they are ~0.2, moderate when ~0.5 and large when ~0.8. As shown in Table 1 , meta-analyses on mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic reach consistent conclusions and indicate that there has been a heterogeneous, statistically significant but small increase in self-reported mental health problems, with pooled effect sizes ranging from 0.07 to 0.27. The largest symptom increase was found when using specific mental health outcome measures assessing depression or anxiety symptoms. In addition, loneliness—a strong correlate of depression and anxiety—showed a small but significant increase during the pandemic (Table 1 ; effect size = 0.27) 16 . In contrast, self-reported general mental health and well-being indicators did not show significant change, and psychotic symptoms seemed to have decreased slightly 13 . In Europe, alcohol purchase decreased, but high-level drinking patterns solidified among those with pre-pandemic high drinking levels 17 . When compared to pre-COVID levels, no change in self-reported alcohol use (effect size = −0.01) was observed in a recent meta-analysis summarizing 128 studies from 58 (predominantly European and North American) countries 18 .

What is the time trajectory of self-reported mental health problems during the pandemic? Although findings are not uniform, various large-scale studies confirmed that the increase in mental health problems was highest during the first peak months of the pandemic and smaller—but not fully gone—in subsequent months when infection rates declined and social restrictions eased 13 , 19 , 20 . Psychological distress reports in the United Kingdom increased again during the second lockdown period 15 . Direct associations between anxiety and depression symptom levels and the average number of daily COVID-19 cases were confirmed in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data 21 . Studies that examined longer-term trajectories of symptoms during the first or even second year of the COVID-19 pandemic are more sparse but revealed stability of symptoms without clear evidence of recovery 15 , 22 . The exception appears to be for loneliness, as some studies confirmed further increasing trends throughout the first COVID-19 pandemic year 22 , 23 . As most published population-based studies were conducted in the early time period in which absolute numbers of SARS-CoV2-infected individuals were still low, the mental health impacts described in such studies are most likely due to indirect rather than direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is possible that, in longer-term or later studies, these direct and indirect effects may be more intertwined.

The extent to which governmental policies and communication have impacted on population mental health is a relevant question. In cross-country comparisons, the extent of social restrictions showed a dose–response relationship with mental health problems 24 , 25 . In a review of 33 studies worldwide, it was concluded that governments that enacted stringent measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 benefitted not only the physical but also the mental health of their population during the pandemic 26 , even though more stringent policies may lead to more short-term mental distress 25 . It has been suggested that effective communication of risks, choices and policy measures may reduce polarization and conspiracy theories and mitigate the mental health impact of such measures 25 , 27 , 28 .

In sum, the general pattern of results is that of an increase in mental health symptoms in the population, especially during the first pandemic months, that remained elevated throughout 2020 and early 2021. It should be emphasized that this increase has a small effect size. However, even a small upward shift in mental health problems warrants attention as it has not yet shown to be returned to pre-pandemic levels, and it may have meaningful cumulative consequences at the population level. In addition, even a small effect size may mask a substantial heterogeneity in mental health impact, which may have affected vulnerable groups disproportionally (see below).

Mental disorders, self-harm and suicide

Whether the observed increase in mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic has translated into more mental disorders or even suicide mortality is not easy to answer. Mental disorders, characterized by more severe, disabling and persistent symptoms than self-reported mental health problems, are usually diagnosed by a clinician based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria or with validated semi-structured clinical interviews. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research systematically examining the population prevalence of mental disorders has been sparse. Unfortunately, we can also not strongly rely on healthcare use studies as the pandemic impacted on healthcare provision more broadly, thereby making figures of patient admissions difficult to interpret.

On a global scale and based on imputations and modeling from survey data of self-reported mental health problems, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 29 estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a 28% (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 25–30) increase in major depressive disorders and a 26% (95% UI: 23–28) increase in anxiety disorders. It should be noted that these estimations come with high uncertainty as the assumption that transient pandemic-related increases in mental symptoms extrapolate into incident mental disorders remains disputable. So far, only four longitudinal population-based studies have measured and compared current mental (that is, depressive and anxiety) disorder prevalence—defined using psychiatric diagnostic criteria—before and during the pandemic. Of these, two found no change 30 , 31 , one found a decrease 32 and one found an increase in prevalence of these disorders 33 . These studies were local, limited to high-income countries, often small-scale and used different modes of assessment (for example, online versus in-person) before and during the pandemic. This renders these observational results uncertain as well, but their contrast to the GBD calculations 29 is striking.