Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Exploring why consumers engage in boycotts: toward a unified model

It has become commonplace for consumers to judge companies against social responsibility criteria. Along with such judgments, many consumers are also taking up action, often using the Internet to virally spread their views. Such consumer-led campaigns can put at risk years of investments in branding. For firms understanding what drives consumers to engage in boycotts is key to minimizing exposure to such viral risk. To date, the academic literature has offered disparate and disconnected findings with respect to boycott participation. In this research paper, we review relevant literature, confirm its appropriateness using a series of in-depth interviews, and use our findings to identify key antecedents to consumer participation in boycotts. We then test our proposed model through an empirical study, thus revealing key drivers of consumers' intention to participate in such boycotts. Our results offer insight into factors that companies can manage so as to prevent consumers from participating in boycotts.

Related Papers

Tricia Chiam

Journal of Consumer Policy

Stefan Hoffmann

Journal of Business Research

Ulku Yuksel

Maya F Farah

Despite a worldwide growth in the number of boycott campaigns, the results of studies are inconclusive as the motives behind individual participation are still largely ignored. Drawing on a socio-cognitive theory, the theory of planned behavior, this research investigates whether the direct variables of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control, help predict consumers' boycott intention. Conducted in Lebanon, this work employs a survey design administered to a randomized systematic sample of 500 Muslim and Christian consumers. The sample is split into two sub-samples reflecting the main religious groups in the Middle-East. Results show that although the Muslim participants appear more prone to participate in the boycott, still attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are all significant predictors of intentions in both communities with the attitudinal component carrying the most weight. This application of a social psychology theory to the consumers' passive resistance to purchasing yielded significant contributions at the theoretical, empirical, and managerial levels.

Clare Dsouza , Tariq Halimi

Previous animosity studies have been conducted in single-target contexts where the effects of hostility towards one product's country of origin were examined. This current study is an attempt to investigate the animosity construct in the multi-target boycott case of the Middle-East conflict where more than one party (countries and companies) are involved in the political conflict, as reports show that consumers have inconsistent reactions to these involved parties. One-on-one in-depth interviews, supported by documentation, were conducted with Arab consumers who are presumably involved in the conflict. It has been found that animosity is multi-level which belongs to the political relations (thereafter POLR) continuum and performs as a product attribute. POLRs' effects on the consumer are subject to parties' involvement level in the conflict and consumer prioritized needs. Research findings imply that " political positioning " can be applied by brands with " good quality " POLR, while others need to highlight other product attributes.

Journal of Business Ethics

Laura Flurry , Krist Swimberghe

Dursun Yener

Asmat-Nizam Abdul-Talib

Elias Boukrami , Omar Al Serhan

Consumer boycotting behaviour has serious consequences for organisations targeted. In this paper, a review of literature on boycotting from 1990 to 2013 is presented. Several consumer boycotting types are identified based on motivations underlying. These are influenced by religious beliefs, cultural values and political opinions. We have scanned all articles dealing with consumer boycotting behaviour in marketing literature. 115 scholarly articles published in 25 top marketing journals as ranked in the ABS (Association of Business Journal Schools) Review from 1990 to 2013 are reviewed. Along with outlining the research in this area, we also wanted to assess the level of attention paid to brand loyalty in relation to boycotting behaviour. Despite the fact that existing literature listed a number of factors that can potentially trigger consumers’ boycotts i.e. religion, war, political, economic, cultural, environmental, and ethical reasons. Nevertheless, there is no ranking of factors indicating which one are the most influential (e.g. long lasting, most damaging in terms of brand loyalty, etc.). Our review also suggests that boycott campaigns in developed nations are mainly motivated by economic triggers. However, in developing nations boycott calls and campaigns were motivated by religious triggers or by ethical triggers. The impact of boycotting on consumers’ brand loyalty, relation between religion, race, country of origin and the level of regional as well as national development would need to be researched further in order to shed light on its effect on the success or failure of boycott calls from consumers’ perspective and the prevention of such calls from the targeted firms’ point of view.

Breno P A Cruz

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Dale W Russell

Laure LAVORATA

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services

Heather Honea , Cristel Russell , Dale W Russell

Nazlida Muhamad

Journal of Consumer Research

Zeynep Gurhan Canli

Advances in Consumer Research, V. 40, eds. Zeynep Gürhan-Canli, Cele Otnes, and Rui (Juliet) Zhu, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research

Elif Izberk-Bilgin

Journal of Consumer Affairs

Riswan E F E N D I Tarigan

Kartini Aboo Talib , Suraiya Ishak , Nidzam Sulaiman

Kartini Aboo Talib , Nidzam Sulaiman , Suraiya Ishak

Crina Mitran

Nikhilesh Dholakia

Michael S W Lee , Denise Conroy

Journal of Consumer Marketing

Krist Swimberghe , Laura Flurry

Omar Al Serhan

RBGN Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios

Safirah Abadi

Muhammad Asif Khan , Michael S W Lee

Felicia Miller , Chris Allen

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Rozita Mohamed

Karin Braunsberger

Lindsay J Benstead

Stefan Hoffmann , Michael S W Lee

Dominique Roux

Journal of Social Marketing

Sergio Rivaroli , Arianna Ruggeri

Delane Botelho

Monica Shirley

Bastian Popp

Fernanda Burjack

Rohit Varman

Lisa Neilson , Social Problems

Ahir Gopaldas

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Decomposing the effects of consumer boycotts: evidence from the anti-Japanese demonstration in China

- Published: 23 February 2019

- Volume 58 , pages 2615–2634, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Zijun Luo 1 &

- Yonghong Zhou 2

1427 Accesses

14 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper quantifies the Chinese consumers’ boycott of Japanese cars that immediately followed the anti-Japanese demonstrations in September 2012. We decompose the total boycott effect into two effects: the transfer effect, which refers to consumers switching from Japanese to non-Japanese brands, and the cancellation effect, which captures decline in sales due to consumers exiting the market. We find that the cancellation effect accounts for more than 90% of the total decline in Japanese car sales, implying a small substitution effect in the automobile market, even though brands of all other countries have benefited. This paper provides evidence of both negative and positive impacts of political conflicts for different market participants and includes analysis with welfare implications.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

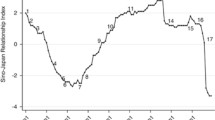

Do political tensions take a toll? The effect of the Sino-Japan relationship on sales of Japanese-brand cars in China

A Model to Follow? The Impact of Neoliberal Policies on the British Automobile Market and Industry

Japan’s automobile market in troubled times.

Recent literature has also analyzed how political conflicts affect economic relationships. See, for example, Fershtman and Gandal ( 1998 ), Michaels and Zhi ( 2010 ), Fuchs and Klann ( 2013 ), Li and Sacko ( 2002 ) and Davis and Meunier ( 2011 ).

Proxy boycotts can also occur in domestic politics. For example, Cuadras-Morató and Raya ( 2016 ) study the boycotts of Catalan sparkling wine in Spain.

Our data also cover the period of the “Senkaku Event” in 2010 that arisen from disputes over the Senkaku Islands, known as Diaoyu Islands in China. However, we find no evidence of negative impact resulted from the 2010 “Senkaku Event” in the Chinese automobile market.

We computed the size of Japanese imported cars as a percentage of “Made in China” Japanese cars using data from UN Comtrade (HS code 8703) and our data and find that imported cars account for less than 10% of Japanese car sales in China.

Studies of the automobile industry are abundant in the economics literature. See, for example, Bandeen ( 1957 ), Sheahan ( 1960 ), Hess ( 1977 ), Berkovec ( 1985 ), Bresnahan ( 1987 ), Cooper and Haltiwanger ( 1993 ), Ries ( 1993 ), Berry et al. ( 1995 ) and Park ( 2003 ), covering a variety of topics. In addition, Depner and Bathelt ( 2005 ), Deng and Ma ( 2010 ), Luong ( 2013 ) and Hu et al. ( 2014 ) provide analyses of various aspects of the Chinese automobile industry.

CAAM also reports the sales of Jiaocha cars, which are designed for both cargo and passenger purposes. This type of car is specially designed for the Chinese market, especially in the rural areas. Since they are not general passenger cars, and there is no foreign-brand cars in this category, we exclude them from our sample.

See Heilmann ( 2016 ) for more details of the boycotts of Japanese products.

Tables 7 and 8 in “Appendix B” give results of the relevant unit root tests, as well as AIC and BIC values for the selections of optimal degrees and lags.

The basic fixed effect regression with common trend is

while the regression with unique trends is

where \(\alpha _{i}\) and \(\lambda _{t}\) indicate the group fixed effect and the time fixed effect and \(D_{it}\) is a dummy variable that equals 1 for the treatment group after policy and 0 otherwise. In the second regression, \(\bar{\lambda _{t}}\) denotes the collection of trends of the non-treatment groups while \(\lambda _t D_{it}\) is the unique trend of the treatment group. With the common trend regression, \({\hat{\rho }}\) gives the estimate of ATE. However, if the unique trend model is the true model, then \({\hat{\rho }}\) would be overestimated because its value is equal to \({\tilde{\lambda }}_t + {\tilde{\rho }}\) from the regression with unique trend.

Please see “Appendix A” for additional detail.

Equation ( 8 ) relies on \(t_0\) , a reference time period. In Sect. 4.1 , two specifications of \(t_0\) are presented.

Ashenfelter O, Ciccarella S, Shatz H (2007) French wine and the U.S. boycott of 2003: Does politics really affect commerce? J Wine Econ 2(1):55–74

Article Google Scholar

Autor DH (2003) Outsourcing at will: the contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. J Labor Econ 21(1):1–42

Bandeen RA (1957) Automobile consumption, 1940–1950. Econometrica 25(2):239–248

Baron DP (2001) Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. J Econ Manag Strategy 10(1):7–45

Baron DP (2003) Private politics. J Econ Manag Strategy 12(1):31–66

Berkovec J (1985) New car sales and used car stocks: a model of the automobile market. Rand J Econ 16(2):195–214

Berry S, Levinsohn J, Pakes A (1995) Automobile prices in market equilibrium. Econometrica 63(4):841–890

Bown CP, Crowley MA (2007) Trade deflection and trade depression. J Int Econ 72:176–201

Bresnahan TF (1987) Competition and collusion in the American automobile industry: the 1955 price war. J Ind Econ 35(4):457–482

Chavis L, Leslie P (2009) Consumer boycotts: the impact of the Iraq war on French wine sales in the U.S. Quant Market Econ 7(1):37–67

Che Y, Du J, Lu Y, Tao Z (2015) Once an enemy, forever an enemy? The long-run impact of the Japanese invasion of China from 1937 to 1945 on trade and investment. J Int Econ 96(1):182–198

Ciro B, De Mello JMP, Alexandre S (2010) Dry laws and homicides: evidence from the São Paulo metropolitan area. Econ J 120(543):157–182

Clerides S, Davis P, Michis A (2015) National sentiment and consumer choice: the Iraq war and sales of US products in Arab countries. Scand J Econ 117(3):829–851

Cooper R, Haltiwanger J (1993) Automobiles and the National Industrial Recovery Act: evidence on industry complementarities. Q J Econ 108(4):1043–1071

Cuadras-Morató X, Raya JM (2016) Boycott or buycott?: Internal politics and consumer choices. BE J Econ Anal Policy 16(1):185–218

Davis CL, Meunier S (2011) Business as usual? Economic responses to political tensions. Am J Polit Sci 55(3):628–646

Deng H, Ma AC (2010) Market structure and pricing strategy of China’s automobile industry. J Ind Econ 58(4):818–845

Depner H, Bathelt H (2005) Exporting the German model: the establishment of a new automobile industry cluster in Shanghai. Econ Geogr 81(1):53–81

Egorov G, Harstad B (2017) Private politics and public regulation. Rev Econ Stud 84:1652–1682

Google Scholar

Fershtman C, Gandal N (1998) The effect of the Arab boycott on Israel: the automobile market. RAND J Econ 29(1):193–214

Fisman R, Hamao Y, Wang Y (2014) Nationalism and economic exchange: evidence from shocks to Sino-Japanese relations. Rev Financ Stud 27:2626–2660

Fuchs A, Klann NH (2013) Paying a visit: the Dalai Lama effect on international trade. J Int Econ 91(1):164–177

Heilmann K (2016) Does political conflict hurt trade? Evidence from consumer boycotts. J Int Econ 99:179–191

Hendel I, Lach S, Spiegel Y (2017) Consumers’ activism: the cottage cheese boycott. RAND J Econ 48(4):972–1003

Hess AC (1977) A comparison of automobile demand equations. Econometrica 45(3):683–702

Hong C, Hu WM, Prieger JE, Zhu D (2011) French automobiles and the Chinese boycotts of 2008: politics really does affect commerce. BE J Econ Anal Policy 11(1):Article 26

Hu WM, Xiao J, Zhou X (2014) Collusion or competition? Interfirm relationships in the Chinese auto industry. J Ind Econ 62(1):1–40

John A, Klein J (2003) The boycott puzzle: consumer motivations for purchase sacrifice. Manag Sci 49(9):1196–1209

Li Q, Sacko D (2002) The (ir)relevance of militarized interstate disputes for international trade. Int Stud Q 46(1):11–43

Luo Z, Tian X (2018) Can China’s meat imports be sustainable? A case study of mad cow disease. Appl Econ 50(9):1022–1042

Luong TA (2013) Does learning by exporting happen? Evidence from the automobile industry in China. Rev Dev Econ 17(3):461–473

Magee CS (2008) New measures of trade creation and trade diversion. J Int Econ 75:349–362

Michaels G, Zhi X (2010) Freedom fried. Am Econ J Appl Econ 2(3):256–281

Pan Y, Zhou Y (2018) War memory: evidence from assistance during Great East Japan earthquake. Defence Peace Econ Forthcoming

Pandya SS, Venkatesan R (2016) French toast: consumer response to international conflict-evidence from supermarket scanner data. Rev Econ Stat 98(1):42–56

Park BG (2003) Politics of scale and the globalization of the South Korean automobile industry. Econ Geogr 79(2):173–194

Peck J (2017) Temporary boycotts as self-fulfilling disruptions of markets. J Econ Theory 169:1–12

Ries JC (1993) Windfall profits and vertical relationships: Who gained in the Japanese auto industry from VERs? J Ind Econ 41(3):259–276

Sheahan J (1960) Government competition and the performance of the French automobile industry. J Ind Econ 8(3):197–215

Waldinger F (2010) Quality matters: the expulsion of professors and the consequences for Ph.D. student outcomes in Nazi Germany. J Polit Econ 118(4):787–831

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the Chinese Economists Society 2015 North America Conference, the 2016 CEC Workshop, and seminars at Fudan University and Peking University. We thank conference and seminar participants, especially Le Wang, Zhao Chen, Wei Huang, Lixing Li, Yongqian Li, Pinghan Liang, Tianyang Xi, Yiqing Xu, and Shilin Zheng for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and International Business, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX, 77341-2118, USA

Department of Economics, Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, Guangdong, People’s Republic of China

Yonghong Zhou

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yonghong Zhou .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhou acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 71803064) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Jinan University (Grant Numbers: 12JNYH002, 12JNKY001, and 15JNQM001).

1.1 Appendix A

To further separate \({\mathsf {CE}}\) and \({\mathsf {TE}}\) and express them as percentages of total changes in sales, we need information on the substitutability between sales of Japanese cars and other cars. Let \(\delta \) denote the marginal rate of substitution (MRS), which is conditional on the information set \(\varLambda _{t}\) ; we then have

which may be rewritten into a discrete form as Footnote 11

The MRS, as conventionally defined, measures the substitutability between sales of Japanese versus other cars, based on the information set. We envisioned the information set to contain not only observable market conditions, but also unobservable attitudes of the Chinese customers towards foreign countries especially Japan. There are three main assumptions for the set up of \(\delta \) in Eq. ( 8 ). First, consumer preferences are stable. It is especially important that consumers’ attitudes towards Japan are stable, which is arguably true because of the long unhappy history between the two countries. This is also why Eq. ( 8 ) does not have a time dimension. Second, non-Japanese and Japanese cars, especially those of similar sizes, are close substitutes, if not perfect substitutes, in the sense that a family may purchase only one car at a time. As a result, the utility function of consumers is a linear combination of consumptions of all cars with a consumer buying the car that gives the highest utility. Last, although price information is unavailable in our data, the prices of new cars in China are stable and can be anticipated almost perfectly. This can be the case because the used car market in China is underdeveloped and most consumers choose to buy new cars from dealership or flagship stores.

1.2 Appendix B

See Tables 7 and 8 .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Luo, Z., Zhou, Y. Decomposing the effects of consumer boycotts: evidence from the anti-Japanese demonstration in China. Empir Econ 58 , 2615–2634 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01650-3

Download citation

Received : 27 February 2017

Accepted : 28 November 2018

Published : 23 February 2019

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01650-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Decomposition

- Substitution

- Political conflict

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Consumer Boycotts

DOI link for Consumer Boycotts

Get Citation

Despite the increasing occurrence of consumer boycotts, little has been written about this form of social and economic protest. This timely volume fills the knowledge gap by examining boycotts both historically and currently. Drawing on both published and unpublished material as well as personal interviews with boycott groups and their targets, Monroe Friedman discusses different types of boycotts-from their historical focus on labor and economic concerns to the more recent inclusion of issues such as minority rights, animal welfare, and environmental protection. He also documents the shift in strategic emphasis from the marketplace (cutting consumer sales) to the media (securing news coverage to air criticism of a targeted firm). In turn, these changes in boycott substance and style offer insights into larger upheavals in the social and economic fabric of 20th century America.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 | 20 pages, consumer boycott basics, chapter 2 | 12 pages, factors affecting boycott success, chapter 3 | 30 pages, labor boycotts, chapter 4 | 26 pages, consumer economic boycotts, chapter 5 | 42 pages, minority group initiatives: african american boycotts, chapter 6 | 28 pages, boycott initiatives of other minority groups, chapter 7 | 22 pages, boycotts by religious groups, chapter 8 | 20 pages, ecological boycotts, chapter 9 | 12 pages, consumer “buycotts”, chapter 10 | 14 pages, boycott issues and tactics in historical perspective.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

“Consumer Boycotts: An Essential Method of Peaceful Protest” – Philip Kotler

September 1, 2020

Consumers normally show their attitude toward a company by patronizing or ignoring the company. Or they might actively dislike the company.

What can a disappointed consumer do about a “bad” company or brand? Not use anymore? Send a complaint to that company asking for an answer? Tell Facebook friends to avoid the company? Take out an Internet ad complaining about the company?

Some angry consumers go further. Consider the members of PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. PETA is an animal rights organization with more than 6.5 million members and supporters. PETA members focus their animal rights activities in four areas: in laboratories, the food industry, the clothing trade, and the entertainment industry. PETA’s aim to discourage consumers from buying products which have come from companies that violated animal rights. Against “bad” companies, PETA uses public education, cruelty investigations, research, animal rescue, legislation, special events, celebrity involvement, and boycott campaigns.

Business historians, company leaders and marketers need to consider the role and power of boycotts in the protection of consumer rights. Boycotts have occurred throughout history.

In the evening of December 16, 1773 in Boston Harbor, a group of Massachusetts colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded three British tea ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor. They complained “no taxations without representation.” Not long after, American colonial merchants called for boycotting all British products. The Boston Tea Party and the Revolutionary War ended up creating a new country, the USA.

The term “boycott” didn’t come into use until 1880. An English land agent, Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott, chose to raise rents and evict a lot of his tenants in Ireland. The local community rebelled and joined together and refused to pay or work with Captain Boycott. He was forced to leave. Boycott left his name to history.

We define a boycott as “a concerted refusal to do business with a particular person or business…in order to obtain concessions or express displeasure.”

To examine the role and power of boycotts, we ask:

- What are the main types and examples of boycotts?

- Why do people organize boycotts?

- How to organize a successful boycott?

- How can the boycotting entity respond to the boycott?

Types and Examples of Boycotts

A group can decide to boycott a large number of entities: an industry, product, brand, company, person, country, practice or idea. The motive might be economic, political or social. Here are some of the best known boycotts in American history.

Boycott against an Industry: Alcohol and the WCTU

As a product, alcohol is a stimulus as well as a curse. Women started temperance leagues in the early 1800s aiming to limit drinking and “demon rum.” By 1830, the average American over 15 consumed at least 7 gallons of alcohol a year. Male drunkenness led to family abuse of wives and children and health problems of all kinds. The World Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was organized in 1873. Its second president, Francis Willard, helped to grow the WCTU into the largest women’s religious organization in the 19th century and helped the drive toward establishing women’s voting rights. Alcoholics Anonymous later was formed with the aim of teaching “teetotalism” or total abstinence to victims of alcoholism. .

Boycott against a good product – Grapes and Chavez

In 1965 on Mexican Independence Day, Cesar Chavez organized Filipino American grape workers to protest for better wages and working conditions in Delano, California. The workers were paid a pittance. Consumers decided to boycott grapes. This decision led to an international boycott of grapes. Grape growers were left with the choice of paying more or letting their grapes rot. The boycott led to the organization of the U.S.’s first farm workers union, The United Farm Worker of America. The strike lasted for five years before reaching a settlement.

Boycott against a bad product – Nestle and Instant Formula

Nestle advertised its infant formula to be “better than breast milk” and more convenient to use. Infant formula was a powder to which water is added. In 1977, many consumers worldwide complained and boycotted the infant formula saying that Nestle mislead customers with inaccurate nutritional claims. In poor countries sadled with infected water, babies often got sick. Nestle refused to compromise for seven years. The boycott ended when Nestle agreed to comply with the World Health Organizations (WHO) standards concerning the marketing of infant formula.

Boycott against a dangerous product – Dow Chemical napalm

The U.S. dropped napalm incendiary bombs in Vietnam in 1979. This led to international outrage against the U.S. and Dow Chemical. Though napalm accounted for only about one-half of 1% of Dow’s $1.6 billion annual sales, the company had become a target for acrimony. Clergymen led picket lines at Dow’s annual meetings.

Boycott against a company – British Petroleum (BP) the Gulf Coast Oil Spill

An explosion on British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010 resulted in the largest U.S. oil spill. The explosion caused 11 deaths and the spilling of 30 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf. The spill lasted 87 days when the well was finally capped on July 15, 2010.

Boycott against a company – Coors Brewing Company and LGBT Rights

In hiring people, Coors Brewing Company discriminated against persons from the LGBT community. In 1973, labor unions organized a boycott to protest Coors antagonistic practices. The boycott was joined by African Americans, Latinos, and the LGBT community. Finally, 14 years later the AFL-CIO and Coors came to an agreement in 1987, ending the official union boycott. But Coors continued to carry a bad name in certain communities.

Boycott against a company – Chick-fil-A

In 2012 the CEO of the restaurant Chick-fil-A publically blamed the country’s woes on accepting gay marriage and continued donating money to anti-LGBT groups. Many Christians kept dining at this restaurant chain and others boycotted Chick-fil-A. The company finally gave into pressure in 2019 to stop donating to companies that supported anti-LGBT talk and turn over more of their donations to promoting youth education, combating youth homelessness, and fighting hunger.

Boycott against a State law – Religious Discrimination against Same-Sex Couples

The state legislature of Indiana passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) in 2015 allowing state businesses to refuse service to same-sex couples based on religious grounds. The business community strongly and swiftly reacted against this law. The state legislature reversed course and modified the law a week later. The RFRA cost Indianapolis more than $60 million.

Boycott against Segregation: Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks and Racial Discrimination

In 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested when she refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. Her act of civil disobedience launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott , a 13-month protest during which black residents refused to ride city buses. Martin Luther King Jr and the Montgomery Improvement Association organized the boycott, which launched civil rights into the national spotlight. The Supreme Court ultimately outlawed segregation on public buses.

Boycott against a country – India, the Salt March and Mahatma Gandhi

In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi l ed a 240-mile march in India to the Arabian Sea to protest Britain’s colonial salt laws. Britain didn’t allow Indians to process or sell their own salt. Gandhi and his followers, in front of thousands, broke the law by evaporating seawater to make salt. He encouraged others to do the same. Gandhi reached an agreement with India’s British viceroy in 1931 in exchange for an end to the salt tax and the release of political prisoners. Colonial rule remained, but the act of civil disobedience stoked the fires of independence. In 1947, the British rule ended and the country was divided into India and Pakistan.

Boycott against a Country – Russia and the Summer Olympics

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter refused to send American athletes to the Summer Olympic Games in Moscow as a protest of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. More than 60 nations joined the U.S. The Soviet-Afghan War continued until 1989. The Soviets subsequently led their own boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Boycott against a Country – Israel and the Arab League Boycott

In 1945, the Arab League (Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) launched an economic boycott of Israel. In the 1970s, the U.S. adopted two laws that prohibited U.S. companies from furthering or supporting the boycott of Israel. Today a new boycott comes in the B.D.S. (boycott, divest, and sanction) movement that seeks to pressure Israel into ending its occupation of the West Bank.

Boycott against a Political Practice – South Africa and the Anti-Apartheid Movement

An international campaign against the oil company Royal Dutch Shell was launched in 1986 to protest apartheid in South Africa. There were nationwide calls in America from labor and civil rights groups asking the public not to buy gas from Shell stations. Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 that banned South African imports, airlines, and foreign aid from the U.S. The end of apartheid began in the early 1990s , when Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners were freed. Apartheid officially ended in 1994, when Mandela became the country’s first black leader.

Boycott for Animal Rights – Protecting whales at SeaWorld

In 2013, a documentary was released which criticized marine parks for its practice of keeping orcas in captivity. The People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) called for boycotts of the park SeaWorld, and SeaWorld’s public attendance declined. In 2016, SeaWorld announced that it would no longer breed or feature shows with orcas.

Boycott against Men – Women Withhold Sex to End Violence

In 2003, Liberian women went on a successful sex strike to end the country’s civil war. Leymah Gbowee won a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts. In 2006, female partners of gang members in Pereira, Colombia, withheld sex as they demanded fewer guns and less violence in their city. By 2010, Pereira’s murder rate had fallen by 26.5%.

Boycott against Consumerism – International Buy Nothing Day

Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, is one of the busiest shopping days of the year. With big crowds, sometimes violence ensues. An anti-consumerist group in Canada launched an anti-shopping movie, “Buy Nothing Day,” in 1992. Some retailers, but very few, decided to stay closed on Black Friday,

Boycott – President Donald Trump as an Active Boycotter of Companies

President Donald Trump has launched personal political attacks of several U.S. companies and people hoping to persuade U.S. citizens to avoid these companies. He attacked Nike for running a successful ad in September 2018 favoring the quarterback Colin Kaepernick who took to his knee during the national anthem in protest to racial injustice. Trump in 2018 lashed out at Google and CNN saying that these media are rigged and report only bad stories or no stories about Republican/Conservatives. He recommended boycotting Apple products for refusing to give cellphone information about a radical group and making most of their products abroad. He attacked Goodyear for banning MAGA hats in the company and tweeted “Get better tires for far less,” and recommended replacing the Goodyear tires on his Presidential car. He issued an executive order to ban the Chinese-owned TikTok unless it found an American buyer for its U.S. operations.

Why Do People Organize Boycotts?

Boycotts are often the result a clash of values between a company and some members of the consuming public. Consumers, in choosing a product, consider two things:

- Value of the product . Does the product and its price and accessibility deliver high value to the potential consumer?

- Values of the company . Are the values of the company acceptable to the values of the consumer?

Most consumers put the most weight on the value of the product. However, some consumers also consider the company’s values. Many grape lovers stopped buying grapes to protest the low wages that grapefield owners paid to grape workers.

We are living in an era of increasing political polarization. If a company isn’t careful, it could offend the values of the blues (Democrats) or the reds (Republicans). If a company shows that it favors stricter gun control, it will offend gun owners. The best thing is for the company not to take any position about guns. If most companies remain quiet, their sales and profits are safer.

Yet many other companies are proud and open about their values. Coors Brewery’s leadership had very conservative values and did not want to hire persons from the LGBT community. A boycott started and lasted until Coors finally agreed in 1987 to not discriminate in their hiring practices.

Boycotts are often organized to further social change of the value of some group. The Montgomery Bus boycott aimed to advance the rights of black Americans. The more the boycott can widen and sustain a Common Good message, the more the chance of changing social values.

The lesson is clear. A company has to think about what values it will represent and how these values would impact different consumer groups and how the company should express its values.

How to Organize a Successful Boycott

A boycott organizing group must make sure that the boycott is not breaking any laws. The boycott is an attack that will hurt the value of a particular entity. It may involve picketing in front of a certain entity. If the entity is a hotel, the boycotters cannot block people from entering or exiting the hotel. Some states might require approval of any planned boycott before the boycotters go into action.

The organizing group must raise enough money to buy ads, picket the company, and sustain the campaign until the entity concedes. It doesn’t pay to start a boycott without the means to keep it going. The company’s response to the boycott will partially be influenced by the company’s estimate of the boycotter’s resources. If quite limited, the company may prefer to take a hit for a short time and not give in to the boycotters.

A nonprofit group, called the Ethical Consumer, is organized to watch for and spot unethical companies. Ethical Consumer was formed in Hulme, Manchester, UK in 1989. In 2009 Ethical Consumer became a full nonprofit multi-stakeholder co-operative consisting of worker members and investor/subscriber members. The group’s aim is to apply pressure on an unethical company to change its way or otherwise face a boycott. Ethical Consumer lists a number of companies that they might target for a boycott unless the company changes its ways. Their targets include a number of well-known companies such as Wendy’s and Amazon.

How Can the Boycotted Entity Respond to the Boycott

If a company gets forewarned of an imminent boycott, the first step is to contact the party and try to settle the issue. If the boycotting group is just trying to extract money from the company to avoid a boycott, the company should report this to the police. If the boycotting group is serious, the company should sitdown and try to work out an agreement. If the offense is not very serious, the company might agree to make a change that would be acceptable by the boycotting group.

If no agreement can be reached and the boycott gets started, the company needs to explain its position to the press and seek the understanding of its customers, employees and other stakeholders. The company needs to estimate how long the boycott might last and how much harm it would do to the company. If it will last a long time and badly damage the company’s reputation, sales and profits, the company should give in on the issue and negotiate an agreement.

The company knows that the boycotting group needs to attract a lot of supporters and keep them interested. The earliest supporters are highly engaged in the cause. It gets harder for the boycott to get additional supporters who have a lower level of interest and may even believe that the boycott doesn’t need more supporters.

The company is in a better position to resist the boycott if it has built up a reputation as a caring company, caring for its customers, employees, and other stakeholders. If it has given a lot to charity and fought for high consensus issues such as a healthy environment, it might less often be the target for a boycott. Companies such Coca Cola and McDonald’s have curried a halo image of good prosocial behavior partly because some groups regularly complain that these companies products, if used in excess, are injurious to health.

Consumers have the right to expect companies to be ethical in their behavior. Fortunately, consumers who get angry enough at a company can send complaints to the company or take out negative ads or organize a boycott. Boycotts have a long history not only against companies but against industries, products, brands, countries, or ideas. Many past boycotts, especially those pressing for prosocial change, have had success. Success depends largely on the resources of the boycotting group and the resources of the targeted entity. The boycott organizing group needs a well-thought out attack strategy and the targeted entity needs a well-thought out defense strategy.

All said, consumers generally benefit from the fact that boycotts are possible and legal. Boycotts call upon the boycotting group to present strong reasons for the boycott and the targeted entity presenting strong reasons for either resisting or reaching an agreement.

Sources: There are many lists of boycotts. One excellent list is Chare Carlile, “History of Successful Boycotts,” May 5, 2019. An excellent discussion on why boycotts occur and how companies can deal with them is found in Jim Salas, Doreen E. Shanahan, and Gabriel Conzalez, “Are Boycotts Prone to Factors That May Make Them Ineffective?” in Strategies for Managing in the Age of Boycotts , 2019 Volume 22, Issue 3.

Philip Kotler is the “father of modern marketing.” He is the S.C. Johnson & Son Distinguished Professor of International Marketing at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. He was voted the first Leader in Marketing Thought by the American Marketing Association and named The Founder of Modern Marketing Management in the Handbook of Management Thinking. Professor Kotler holds major awards including the American Marketing Association’s (AMA) Distinguished Marketing Educator Award and Distinguished Educator Award from The Academy of Marketing Science. The Sales and Marketing Executives International (SMEI) named him Marketer of the Year and the American Marketing Association described him as “the most influential marketer of all time.” He is in the Thinkers50 Hall of Fame , and is featured as a “guru” in the Economist .

Related Posts

B2B Marketing /

“Go-to-Market (GTM): A New Definition” – Karthi Ratnam

B2C Marketing /

“Understanding Hallyu: The Impact of Korean Pop Culture” by Sanya Anand and David Seyheon Baek

Brand Activism /

“Regeneration or Extinction?” – a discussion with Philip Kotler, Christian Sarkar, and Enrico Foglia

Shopping has become a political act. Here’s how it happened.

Consumer activism and conscious consumerism mean more people are buying from brands they agree with — and boycotting ones they don’t.

by Stephie Grob Plante

In August, it was SoulCycle and Equinox . The month prior, Home Depot . Back in 2017, L.L.Bean . These are only a few of the companies to ignite the collective ire of progressive consumers over corporate ties to Trump. In the case of the boutique fitness studios, it was a Trump fundraiser hosted by their majority stake investor Stephen M. Ross; with the home improvement chain, it was co-founder Bernie Marcus’s promise to donate to Trump’s 2020 reelection campaign; with the duck boot and outdoor apparel brand, it was Bean descendant and board member Linda Lorraine Bean’s $60,000 donation to Trump super PAC Making America Great Again, LLC (itself a violation of the Federal Election Commission’s permitted donor limit of $5,000).

For Americans opposed to Trump’s policies — from the inhumane treatment and targeting of detained migrants , to detrimental inaction on climate change , to refusal to regulate guns in the wake of unprecedented mass shootings — shopping at retailers connected to the celebrity-entrepreneur-turned-sitting-president is tantamount to hypocrisy.

“The goal came originally from a place of really wanting to shop the stores we loved again with a clear conscience”

Calls to boycott Trump-tainted brands stretch back to the #GrabYourWallet movement that began in the wake of the 2016 election. Organizers Shannon Coulter and Sue Atencio turned outrage into action with a spreadsheet of companies linked to Trump or the Trump family, both explicitly (Trump owned) and implicitly (Trump funders, Trump brand sellers), detailing why those companies are on the list and what they need to do to get off it. “The goal,” Coulter told the New York Times , “came originally from a place of really wanting to shop the stores we loved again with a clear conscience.”

Of course, boycott calls are not unique to Trump’s critics; Trump himself is an avid boycotter , and his MAGA fans follow suit . Nor are boycott calls unique in the Trump era. Consumers have long registered their disapproval of businesses’ practices by refusing to shop them and calling on others to do the same, dating back to this country’s birth (and further back elsewhere in the world, like in ancient Greece and early Christianity, in the form of organized ostracism).

What do you get when consumers takes action? Consumer activism. And by the inverse action, consumers are shopping alternative products and companies that complement their worldview more now than ever before — particularly when it comes to combating climate change. Sustainability-tinged consumer activism is a new flavor of an old tactic, one that falls under the umbrella of what we now call conscious consumerism.

Consumer activism can take the shape of two diametrically opposed actions — buying en masse and boycotting en masse — that are after the same goal

“[Consumer activism is] either grassroots collective organization of consumption or its withdrawal,” explains Lawrence Glickman, an American historian at Cornell University and author of Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism .

Meaning, it’s “Buy Nike!” to express support of Colin Kaepernick’s 2018 pick as brand ambassador following his kneeled protest against police brutality targeting people of color and his collusion lawsuit against the NFL . It’s also, “ Boycott Nike !” and even, “ #BurnYourNikes !” to express outrage over “when somebody disrespects our flag,” as Trump put it in 2017, supposedly provoked by Kaepernick’s peaceful demonstration.

Calls to boycott, though, are a heck of a lot more visible on social media than are rally cries to pledge brand support. Glickman writes in Buying Power that two-thirds of Americans take part in at least one boycott a year.

Boycotts stem from anger. Anger spreads faster and farther on social media than any other emotion, as uncovered by computer scientists at China’s Beihang University and reported by MIT Technology Review . And there are many, many ongoing and overlapping boycotts at any given time. AP News even has a feed to track boycotts worldwide.

Consumer activism, boycotts included, puts power in the hands of the people — ”or at least they think it is,” adds Glickman.

We boycotted before there was even a word for it

“Boycotts are as American as apple pie,” #GrabYourWallet co-founder and digital strategist Coulter told Fast Company in 2017, referring to the Boston Tea Party’s 1773 dump of British imports that precipitated the American Revolutionary War. Colonists had boycotted British tea for several years by then; “No taxation without representation,” they demanded. Refusing to purchase British tea was a pointed way to voice their mounting resentment of their decidedly un-independent status. Short of revolt, it was the only power they had — until, of course, they revolted.

Glickman dates the boycott much further back: to ancient Greece. Expedition Magazine cites the city of Athens’ historic boycott of the Olympic Games in 332 BCE as a key turning point. The city had incurred a massive fine after its endorsed athlete attempted, and failed, to fix a match, and refused to attend the games in protest unless the charges were dropped. (They weren’t, and Athens eventually relented.)

Boycotts are employed the world over, and not all of them are about consumerism

The term “boycott” didn’t emerge, however, until 1880, in Ireland. Captain Charles Boycott was a British land agent in County Mayo — and “ the man who became a verb! ” — whose evictions “were many and bloody,” as described by IrishCentral. After Boycott attempted to evict another 11 tenants, the Land League (an Irish political organization of the 1800s that rallied in aid of poor farmworkers) convinced Boycott’s employees to walk out and compelled the community to, essentially, ice him out. Shops and the like refused to do business with him, the post stopped his mail. He left Ireland humiliated.

Boycotts are employed the world over, and not all of them are about consumerism. Just last month, tens of thousands of students in Hong Kong boycotted the first day of school as part of ongoing protests over an extradition bill that could send Hong Kong citizens to China, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called for a boycott of the Israeli TV channel that co-produced the HBO show Our Boys , and Sweden’s top female hockey players are boycotting the national team over unfair pay and poor working conditions.

Still, there is a certain Americanness to the ubiquity of the boycott today. Take #GrabYourWallet, which at present calls for boycotts of 31 different companies (not including subsidiaries or partners), five over their Stephen M. Ross connections. Says Glickman, Americans “didn’t invent [the boycott], but the frequency with which we use it is somewhat exceptional.”

Consumer activism in 2019 is not a whole lot different from consumer activism in the 1840s — except when it comes to the causes

“A lot of people think that what we’re seeing now is new,” says Glickman. “But there are a lot of parallels with history.” Particularly, America’s history of slavery and abolitionism.

The Free Produce Movement, led by Quaker abolitionists in the 1840s through the Civil War, hinged on boycotting goods made by enslaved people, cotton key among them. Buying these products, as far as Free Produce stalwarts were concerned, was analogous to supporting slavery outright.

The issues are different today, but the strategy remains the same: Vote with your dollar and don’t contribute a cent to the bottom line of companies whose values don’t align with your own. Says Glickman, “That fundamental question of, ‘No one stands outside of moral problems, that we’re all implicated in [them]’ — that’s the essence of consumer activism.”

“‘No one stands outside of moral problems, that we’re all implicated in [them]’ — that’s the essence of consumer activism”

Voting with your dollar doesn’t just mean not spending your dollars in problematic places (i.e. Amazon , Wayfair , etc.); it also means supporting companies that practice what they preach, both by way of their company culture and by what they sell. Conscious consumerism drives at that very point, particularly when it comes to “voting” for sustainability and humane working conditions.

Says the Nation’s Willy Blackmore of the boycott’s antebellum lineage, where abolitionists bought wool over cotton and maple sugar over cane:

The same thinking—that it’s better to buy products that we believe are made without exceptional suffering—animates some contemporary conscious consumerism. The desire to minimize the harm we cause as consumers has led to a variety of fluffy marketing terms as well as third-party verification organizations, so you can buy everything from cruelty-free makeup to Fair Trade food products.

Conscious consumerism (alternatively called ethical consumption) is today’s catchall to cover consumer dollars invested in a host of progressive values: worker rights, animal rights, low-carbon footprint, recycled and/or renewable materials, organic, local, etc. — your fair-trade fashion, your greenhouse-gas-cutting Ikea , your metal straw. It’s a term that’s caught on in the last 10 years, but it was not only predated by the green consumerism of the 1990s , it’s also the driving argument behind all consumer activism from the tea-in-the-harbor get-go.

What is newish, however, is the phenomenon of sustainable shopping and widespread availability of ethically made, eco-friendly goods — where consumers concerned about climate change, for instance, “live their values” vis a vis their plastic-free purchases.

“It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when we saw consumers trying to make positive environmental change in their shopping,” says Emily Huddart Kennedy, University of British Columbia sociologist and author of Putting Sustainability into Practice: Applications and Advances in Research on Sustainable Consumption. Data analytics company Nielsen called 2018 “The Year of the Influential Sustainable Consumer,” adding that “it’s soon to be the decade of the sustainable shopper.” Sustainable product sales reached $128.5 billion in 2018, up 20 percent from four years prior; Nielsen projects 2021 to cash in on $150 billion worth of sustainability sales.

There are several theories, says Kennedy, on what caused the shift, including mistrust in government to adequately address climate change and the growing “sense of doing something in the face of these huge sustainability crises,” as she puts it. Kennedy’s research has shown that conscious consumerism’s popularity can also be tied to its elite nature — in part because of high price tags, in part because of championing among celebrities, in part because of its en vogueiness, “it’s seen as a ‘high-class’ thing to do.”

Consuming consciously is aspirational, both for individuals and for the planet. University of Toronto sociologist Josée Johnston, a colleague of Kennedy’s, found that nearly two-thirds of consumers resonated with the statement, “shopping is a powerful force for social and environmental change.” Elaborates Johnston’s survey report in the Journal of Marketing Management , “This suggests that the majority of the shopping public believe that their shopping dollars can promote a social and environmental alternative to the status quo.”

Consumer activism, for all its prevalence, might be an unintentional misdirect, say critics

Activists for any one particular cause are in no way united that consumer activism is the most effective way — or even an effective way — to enact change. The main criticism is that individual product swaps do nothing to impact legislation and corporate responsibility.

That’s not a new argument; many abolitionists disagreed with their Free Produce Movement cohorts. As Glickman writes in Buying Power , “Critics accused free produce activists of overvaluing private rectitude to the point where it had little connection with the public good.” Maybe wearing wool and eating maple makes you abolitionists feel better, Free Produce critics seemed to say, but it does squat to end slavery.

Twenty-first century shoppers face, in spirit, the same conundrum.

“Conscious consumerism is a lie,” writes sustainable fashion expert and frequent Vox contributor Alden Wicker for Quartz , quoting a speech she delivered at the 2017 UN Youth Delegation. “Small steps taken by thoughtful consumers — to recycle, to eat locally, to buy a blouse made of organic cotton instead of polyester — will not change the world.” Instead, she argues, conscious consumerism is an expensive distraction from the real work at hand.

Sure, vote with your dollar, the criticism stands — but you do a whole lot more by simply voting for politicians who give a damn that the Earth is melting . Only 46.1 percent of voters aged 18-29 voted at all in 2016, 55 percent of which voted Democrat . Nielsen found that 90 percent of millennials (aged 21-34) are willing to pay more for eco-friendly and sustainable products. These stats don’t necessarily provide a one-for-one since there’s a gap in the age categorizations, but if the entirety of that 90 percent of conscious consumer millennials had gone to the polls and voted how their dollar votes ... We don’t have to spell it out, right?

With more opportunities to be a conscious consumer — thanks to more and more “leading brands that compete to see who is greener,” as Joel Makower, author of 1990’s The Green Consumer, writes for GreenBiz — so too do opportunities for economic existential angst mount. Ditching plastic straws, in the grand scheme of things, will do diddly for the planet, representing less than 1 percent of our sweeping plastic problem.

And as such, conscious consumerism can deliver unearned complacency, house-on-fire calm akin to “This Is Fine” dog . As Jim Leape, co-director of the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions told Stanford Report , “The risk is that banning straws may confer ‘moral license’ — allowing companies and their customers to feel they have done their part. The crucial challenge is to ensure that these bans are just a first step.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren homed in on this very point during CNN’s recent climate change forum, following a series of questions to Democratic candidates on regulating lightbulbs, banning plastic straws, and encouraging people to cut down on red meat, as reported by Vox’s Li Zhou :

“Oh, come on, give me a break,” Warren said in response to the lightbulb question, in one of the breakout moments of the night. “This is exactly what the fossil fuel industry wants us to talk about. ... They want to be able to stir up a lot of controversy around your lightbulbs, around your straws, and around your cheeseburgers, when 70 percent of the pollution, of the carbon that we’re throwing into the air, comes from three industries.”

There’s an added tension when it comes to green shopping and movements like Fridays for Future and the Sunrise Movement , that conscious consumerism’s prescribed solution is antithetical to sustainability’s aims.

“The idea of ‘shopping’ your way to sustainability is fundamentally flawed,” says sociologist Kennedy. “That is, if we need to slow down growth to protect the environment, then we can’t rely on ‘better’ consumption — we also have to reduce consumption.” To her point, climate activist Greta Thunberg’s speech at the UN’s Climate Action Summit on September 23 addressed world leaders but zeroed in on an oft-repeated delusion that cutting emissions by 50 percent in 10 years will do the trick. “We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you.”

There are alternative ways that consumers can “do something” impactful with their money, writes Wicker in Quartz: Donating to activist organizations and donating to politicians who vow to vote for green initiatives (i.e. passing a Green New Deal ) and holding big corporate offenders accountable are good places to start.

Okay, okay, but does consumer activism do … anything?

In a word: sometimes! In more words, whether or not consumer activism and conscious consumerism “work” depends, really, on the definition of success.

Historian Glickman likes to differentiate between short-term and long-term goals. Sociologist Kennedy separates material benefits from ideological gains.

“Oftentimes the boycott starts with a great deal of enthusiasm and ends with a whimper”

“Almost every boycott fails to achieve its punitive goal,” says Glickman. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, he adds, is a rare example of an “unambiguous victory,” where the boycott attained its demands : hiring black drivers, promising respectful drivers, and first-come first-seated policy. The SoulCycle boycott is another: Last month’s consumer activism over Ross’s Trump fundraiser did in fact dent SoulCycle’s attendance . But these are notable exceptions (the former inarguably more impactful than the latter) to the rule.

Adds Glickman, “A lot of times boycotts of big corporations don’t really affect the bottom line of that corporation. Oftentimes the boycott starts with a great deal of enthusiasm and ends with a whimper.” For instance, Amazon: Despite calls year after year to boycott Amazon Prime Day over factory conditions (and this year over contracts with ICE ), the retail behemoth repeatedly manages to smash its sales record .

In terms of the material benefit of product swaps, “the jury is out,” says Kennedy. Yes, phosphate-free dish detergent can curb water pollution, she says; but Kennedy’s research shows that conscious consumers often maintain very large carbon footprints themselves. “Conscious consumers tend to be well-educated,” explains Kennedy, “and well-educated people typically earn a good income,” income that buys them nice cars and tickets on commercial planes and air conditioning units and so on.

“The ideological benefits are not much more conclusive, unfortunately,” adds Kennedy. “I think it’s fair to say that conscious consumption has made more people think about the resources that go into the stuff we buy and about what happens to our stuff when we throw it away.” This, in effect, is consumer activism’s long-term goal, what historian Glickman calls “a transformation of consciousness.” On the other hand, Kennedy says, “When people obsess about the environmental impact of their goods, that can let companies and governments off the hook. So it’s a mixed bag.”

Where and how we spend our money does matter. But how much it matters depends on what else we do with our money and what governments and corporations do with their (considerably larger) pots. At best, the rising popularity of conscious consumerism, for instance, suggests that the buying public will at least spend their way to a healthier world; the big problem, though, is that individual monetary action — even when performed collectively — is only the beginning.

“I can’t imagine that the world is worse off because of conscious consumerism,” says Kennedy, “but I doubt it will be enough to save the planet.”

Sign up for The Goods’ newsletter. Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

Most Popular

- Republicans ask the Supreme Court to disenfranchise thousands of swing state voters

- Did the Supreme Court just overrule one of its most important LGBTQ rights decisions?

- The Chicago DNC everyone wants to forget

- How the DNC solved its Joe Biden problem

- Why Indian doctors are protesting after the rape and death of a colleague

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Money

From shipping lanes to airspace to undersea cables, globalization is under physical attack.

Why, and how, the US should fix its debt problem.

It is important to hang onto grudges against the Supreme Court.

Is the Federal Reserve finally about to cut interest rates?

It’s the latest way Biden is trying to combat pesky “junk fees” driving up prices.

Elon Musk’s social media site is accusing brands of breaking antitrust laws.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Vanishing Boycott Impetus: Why and How Consumer Participation in a Boycott Decreases Over Time

Wassili lasarov.

1 Department of Marketing, Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Westring 425, 24118 Kiel, Germany

Stefan Hoffmann

Ulrich orth.

2 Institute of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agricultural and Nutritional Sciences, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Wilhelm-Seelig-Platz 6/7, 24098 Kiel, Germany

Associated Data

Media reports that a company behaves in a socially nonresponsible manner frequently result in consumer participation in a boycott. As time goes by, however, the number of consumers participating in the boycott starts dwindling. Yet, little is known on why individual participation in a boycott declines and what type of consumer is more likely to stop boycotting earlier rather than later. Integrating research on drivers of individual boycott participation with multi-stage models and the hot/cool cognition system, suggests a “heat-up” phase in which boycott participation is fueled by expressive drivers, and a “cool-down” phase in which instrumental drivers become more influential. Using a diverse set of real contexts, four empirical studies provide evidence supporting a set of hypotheses on promotors and inhibitors of boycott participation over time. Study 1 provides initial evidence for the influence of expressive and instrumental drivers in a food services context. Extending the context to video streaming services, e-tailing, and peer-to-peer ridesharing, Study 2, Study 3, and Study 4 show that the reasons consumers stop/continue boycotting vary systematically across four distinct groups. Taken together, the findings help activists sustain boycott momentum and assist firms in dealing more effectively with boycotts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10551-021-04997-9.

Introduction

In 2013, a TV documentary on the substandard work conditions of employees who were subcontracted by a leading e-tailer evoked strong reactions with consumers in Germany, many of whom decided to boycott the company (Spiegel.de, 2013 ). After a while, however, public outrage and boycott participation waned (NTV.de, 2013 ). This anecdotal example ties in with econometric reports obtained at a macro level that boycotts lose participants and momentum over time (Chavis & Leslie, 2009 ). To date, however, researchers have not yet adopted an individual perspective on boycott participation to analyze promotors and inhibitors over time. Does boycott participation decline because consumer aggrevation fades, because consumers continue disapproving the transgression but revert to old habits for the sake of convenience, or because they loose faith in their boycott making a difference? Activists as well as managers need insights into these questions to respond more adequately.

Table Table1 1 provides an overview of extant research that has examined drivers of boycott participation at the micro level. The table shows that previous research has almost exclusively employed cross-sectional studies (e.g., Klein et al., 2004 ; Sen et al., 2001 ). In addition, extant studies focused on consumers joining—instead of exiting—a boycott, hereby leaving a gap in knowledge about factors influencing a consumer's decision to sustain rather than stop boycotting. Furthermore, Table Table1 1 illustrates that only a few studies suggest a temporal variation in and a possible revision of boycott decisions. For example, Chavis and Leslie ( 2009 ) showed boycotting to cease after an eight-month period, with sales returning to pre-boycott levels. However, the study adopted an aggregate perspective on boycotting and did not account for changes in individual behavior including possible drivers. Similarly, Ettenson and Klein ( 2005 ) reported two cross-sectional studies with data obtained from independent samples at two points in time. While they found an extension of boycotting beyond a one-year timeline, their study design did not permit drawing inferences regarding possible changes in individual boycotting behavior. Hoffmann ( 2011 ) gives additional insight on temporal effects. By grouping participants according to the dates they entered the boycott, he explored why consumers join boycotts at different stages. The study did not, however, extend to further changes in boycotting. In summary, previous research did not analyze temporal changes in boycott participation at the individual level after the decision to join had been made, nor did researchers examine the factors that impact changes. From a practical perspective, determining why consumers sustain or stop boycotting will help companies deal with boycotts more appropriately, and will aid activists in sustaining boycotts and keeping momentum.

State of literature and contributions of this article

PE perceived egregiousness, PC perceived control, SC subjective costs, SE self-enhancement, BI brand image, PS perceived service quality, FE service of frontline employees, DV dependent variables, B t0 Boycott participation ( t 0), B t1 Boycott participation ( t 1)

a Only the papers that are most relevant to the current study are cited here. Only aspects related to the current study are documented

Against this background, our study makes the following contributions to the literature (see Table Table1). 1 ). We extend boycott participation models (Hoffmann, 2011 ; Klein et al., 2004 ) to include a longer time period and to detail temporal changes in boycott participation at the individual consumer level. We label these changes "intrapersonal" to better communicate variations within an individual person across different points in time (Craik & Salthouse, 2008 ). Additionally integrated into the extension are consumer exits from the boycott, a perspective informed by research on the temporal effects of anger and revenge evoked by unethical behaviors (e.g., Ettenson & Klein, 2005 ; Klein et al., 1998 ; Lee et al., 2016 ; Sato et al., 2018 ). We extrapolate these findings to boycott contexts where the individual’s participation is driven by his or her perception of egregious conduct by the target firm (Klein et al., 2004 ). Although the perceived egregiousness contains both emotional and cognitive elements, social boycott calls often employ strongly emotional appeals, with moral condemnation of the target. Furthermore, by adopting Friedman’s ( 1999 ) distinction between expressive and instrumental boycotts we suggest a “heat-up” phase in which boycotters mainly make use of expressive drivers to join, and a “cool-down” phase in which additional instrumental drivers come into play, possibly causing a stop of boycotting. Finally, we identify distinct groups of consumers (boycotter types) who vary systematically in the reasons they continue and cease boycotting. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model underlying our research.

Conceptual model

Conceptual Background

Boycott participation: definition and extant models.

In his seminal article, Friedman ( 1985 , p. 97) describes consumer boycotts as “… an attempt by one or more parties to achieve certain objectives by urging individual consumers to refrain from making selected purchases in the market place.” Activists have called consumer boycotts to achieve economic, social, ecological, ethical, ideological, or political objectives (Friedman, 1999 ; Sen et al., 2001 ) with regard to diverse issues including prices, human rights, working conditions, environmental protection, animal welfare, religion, or international politics (Yuksel et al., 2020 ). Boycotts can be direct or indirect (Friedman, 1999 ). In a direct boycott, participants avoid products and services of a target company whose policies they consider irresponsible. In an indirect boycott, participants avoid products of companies associated with a target, such as suppliers or firms located in a target country, to exert pressure on the target (Ettenson & Klein, 2005 ; Hoffmann et al., 2020 ).

In line with Friedman ( 1985 ), we view boycott participation as an individual consumer’s decision to respond to a collective call for a boycott by refraining from purchasing from a specific company or brand for the explicit purpose of achieving the boycott’s objectives. Importantly, this definition highlights that the participation supports a collective, group-driven action; it specifically excludes individualistic decisions to avoid brands (e.g., for reasons of personal health or identity). Further emphasizing group aspects, insights into consumer motivations of boycott participation (e.g., Klein et al., 2004 ; Sen et al., 2001 ) mainly utilize theories of social psychology and economics (e.g., theories of fairness and reciprocity, game theory, and social dilemma; Delacote, 2009 ; John & Klein, 2003 ). In this research stream, scholars have identified factors that drive consumers to join boycotts (e.g., self-enhancement), as well as factors that prevent them from boycotting (e.g., a lack of substitutes, inconvenience, skepticism about boycott efficacy; Klein et al., 2004 ; Sen et al., 2001 ).

Integrating and further detailing these factors, our research builds on and extends the model conceived by Klein et al. ( 2004 ) and refined by Hoffmann ( 2011 ). Klein et al.’s ( 2004 ) model views boycott participation as a deliberate act of abstinence. Initially, perceived egregiousness evokes arousal. Then, consumer boycott participation depends on anticipated rewards (such as self-enhancement) and the costs of abstaining from obtaining a preferred product. Hoffmann ( 2011 ) extended this model to include the “trigger/promoter/inhibitor” concept. We build on his conceptualization, because the trigger-promoter-inhibitor distinction is broader than the initial arousal-rewards-costs perspective, capturing a broader range of drivers of boycott participation. For example, while Klein et al.’s ( 2004 ) model includes only perceived egregiousness as a trigger of arousal, other studies show that a consumer’s proximity to the company’s wrongdoing can serve as an additional trigger (Hoffmann, 2011 , 2013a ). Furthermore, Klein et al.’s concept of benefits may be too narrow, as, for example, moral obligation can function as another promoter (Hoffmann et al., 2013b ). Similarly, the original notion of costs may be too narrow, as other inhibitors, such as negative information about a competitor, have shown to be relevant (Yuksel & Mryteza, 2009 ). The trigger-promoter-inhibitor concept is therefore thought to be more flexible, accounting for additional and more divergent boycott participation motivations as identified in previous research.

Triggers of Boycott Participation

According to Hoffmann ( 2011 ), the perception that a firm’s behavior is wrong triggers consumer behavioral response, because the perception negatively and harmfully affects workers, consumers, society at large, and other stakeholders. The extent to which the firm’s action is considered egregious depends on the individual. Accordingly, “perceived egregiousness” is the central trigger of boycott participation (Klein et al., 2004 ). Capturing the extent to which a person views an act (e.g., of a firm) as socially unacceptable, perceived egregiousness represents the level of a boycotter’s anger.

Promoters of Boycott Participation

"Promoter" is an umbrella term used to capture factors that encourage boycott participation, specifically instrumental and moral factors (Hoffmann, 2011 ). Regarding instrumental factors, consumers are more likely to participate in a boycott when they expect their participation to increase the boycott's success (Sen et al., 2001 ), a type of boycott-related self-efficacy (Bandura, 2012 ). Regarding moral factors, consumers strive to enhance their self-esteem, and participating in a boycott—as a moral act—helps them do so (Klein et al., 2004 ). We therefore focus on perceived control and self-enhancement as important instrumental and moral promoters.

Inhibitors of Boycott Participation

Inhibitors are factors that impede boycott participation. In line with previous studies (Hoffmann, 2011 ; Klein et al., 2004 ), we examine a variety of costs that occur when individuals boycott companies. First, withholding consumption is strongly associated with subjective costs, which, in turn, greatly depend on the availability of alternatives (Friedman, 1999 ; Sen et al., 2001 ). When consumers join a boycott, they may face costly challenges, such as gathering additional information about alternatives, abstaining from products they have preferred in the past, switching to more expensive alternatives, paying greater procurement costs, or even facing a complete lack of alternatives. While these subjective costs predominantly refer to increasing information costs, research costs, and financial costs involved in switching to other brands (or the lack of alternatives), there are other inhibitors that reflect other types of costs. A positive image can buffer against consumers’ boycott participation. Increased levels of trust decrease consumers’ willingness to participate in a boycott (Hoffmann & Müller, 2009 ), as they would have to build similar levels of trust with another brand. When consumers have long-standing positive associations with the company, they are therefore less likely to react negatively in times of crises, such as a transgression (Klein & Dawar, 2004 ). Consistent with this line of thought, a consumer’s overall satisfaction with the company and his or her positive experience from interactions with company employees might also increase switching costs and prevent him or her from boycotting.

Developing a Model of Intrapersonal Variation in Boycott Participation

Intrapersonal variation moderated by perceived egregiousness.