Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What Are Research Objectives and How to Write Them (with Examples)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Research is at the center of everything researchers do, and setting clear, well-defined research objectives plays a pivotal role in guiding scholars toward their desired outcomes. Research papers are essential instruments for researchers to effectively communicate their work. Among the many sections that constitute a research paper, the introduction plays a key role in providing a background and setting the context. 1 Research objectives, which define the aims of the study, are usually stated in the introduction. Every study has a research question that the authors are trying to answer, and the objective is an active statement about how the study will answer this research question. These objectives help guide the development and design of the study and steer the research in the appropriate direction; if this is not clearly defined, a project can fail!

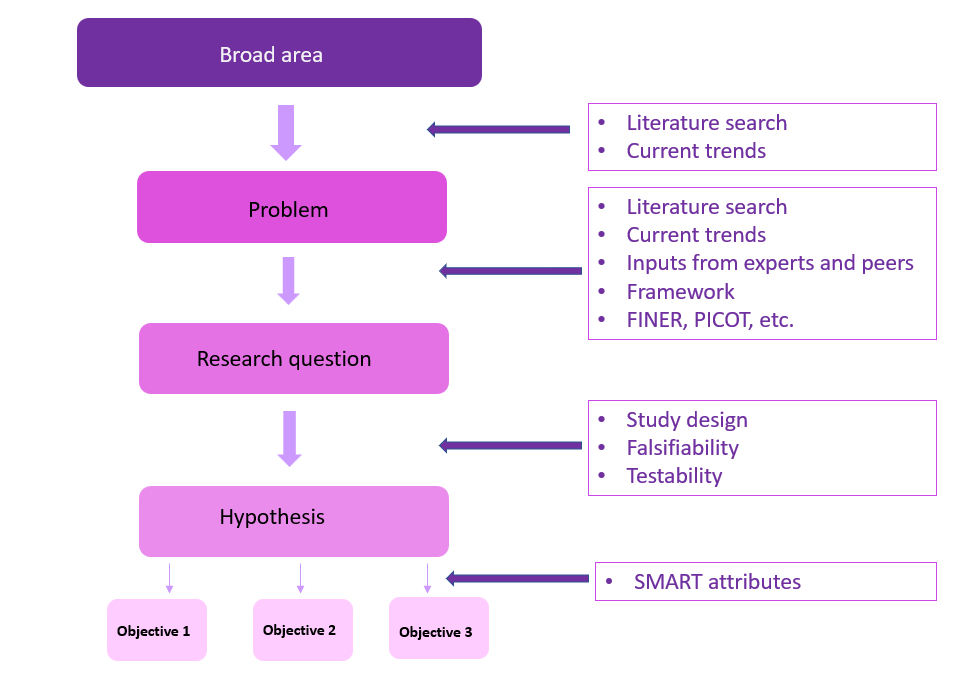

Research studies have a research question, research hypothesis, and one or more research objectives. A research question is what a study aims to answer, and a research hypothesis is a predictive statement about the relationship between two or more variables, which the study sets out to prove or disprove. Objectives are specific, measurable goals that the study aims to achieve. The difference between these three is illustrated by the following example:

- Research question : How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

- Research hypothesis : Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

- Research objective : To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

This article discusses the importance of clear, well-thought out objectives and suggests methods to write them clearly.

What is the introduction in research papers?

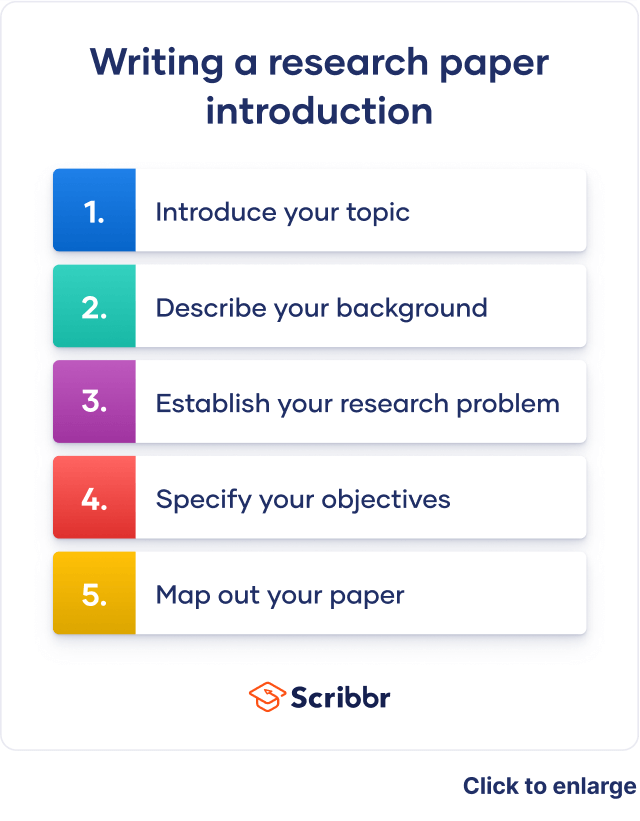

Research objectives are usually included in the introduction section. This section is the first that the readers will read so it is essential that it conveys the subject matter appropriately and is well written to create a good first impression. A good introduction sets the tone of the paper and clearly outlines the contents so that the readers get a quick snapshot of what to expect.

A good introduction should aim to: 2,3

- Indicate the main subject area, its importance, and cite previous literature on the subject

- Define the gap(s) in existing research, ask a research question, and state the objectives

- Announce the present research and outline its novelty and significance

- Avoid repeating the Abstract, providing unnecessary information, and claiming novelty without accurate supporting information.

Why are research objectives important?

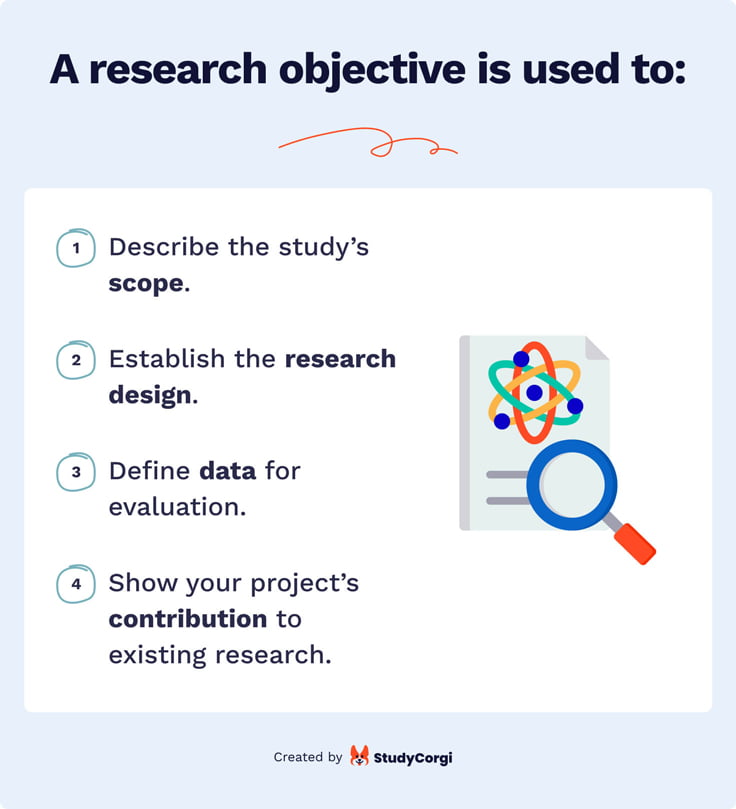

Objectives can help you stay focused and steer your research in the required direction. They help define and limit the scope of your research, which is important to efficiently manage your resources and time. The objectives help to create and maintain the overall structure, and specify two main things—the variables and the methods of quantifying the variables.

A good research objective:

- defines the scope of the study

- gives direction to the research

- helps maintain focus and avoid diversions from the topic

- minimizes wastage of resources like time, money, and energy

Types of research objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives . 4 General objectives state what the research expects to achieve overall while specific objectives break this down into smaller, logically connected parts, each of which addresses various parts of the research problem. General objectives are the main goals of the study and are usually fewer in number while specific objectives are more in number because they address several aspects of the research problem.

Example (general objective): To investigate the factors influencing the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

Example (specific objective): To assess the influence of firm size on the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

In addition to this broad classification, research objectives can be grouped into several categories depending on the research problem, as given in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of research objectives

| Exploratory | Explores a previously unstudied topic, issue, or phenomenon; aims to generate ideas or hypotheses |

| Descriptive | Describes the characteristics and features of a particular population or group |

| Explanatory | Explains the relationships between variables; seeks to identify cause-and-effect relationships |

| Predictive | Predicts future outcomes or events based on existing data samples or trends |

| Diagnostic | Identifies factors contributing to a particular problem |

| Comparative | Compares two or more groups or phenomena to identify similarities and differences |

| Historical | Examines past events and trends to understand their significance and impact |

| Methodological | Develops and improves research methods and techniques |

| Theoretical | Tests and refines existing theories or helps develop new theoretical perspectives |

Characteristics of research objectives

Research objectives must start with the word “To” because this helps readers identify the objective in the absence of headings and appropriate sectioning in research papers. 5,6

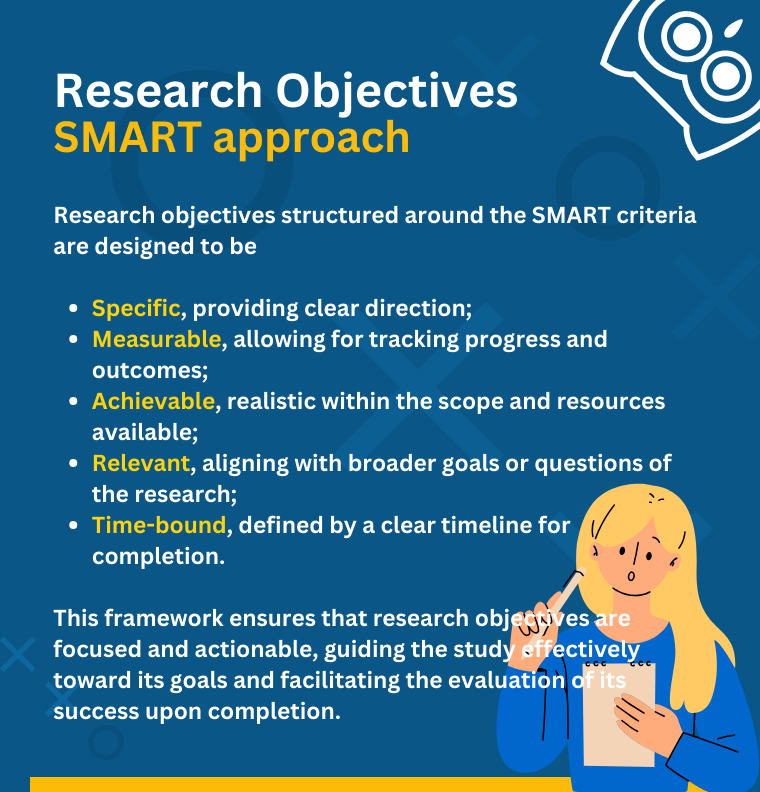

- A good objective is SMART (mostly applicable to specific objectives):

- Specific—clear about the what, why, when, and how

- Measurable—identifies the main variables of the study and quantifies the targets

- Achievable—attainable using the available time and resources

- Realistic—accurately addresses the scope of the problem

- Time-bound—identifies the time in which each step will be completed

- Research objectives clarify the purpose of research.

- They help understand the relationship and dissimilarities between variables.

- They provide a direction that helps the research to reach a definite conclusion.

How to write research objectives?

Research objectives can be written using the following steps: 7

- State your main research question clearly and concisely.

- Describe the ultimate goal of your study, which is similar to the research question but states the intended outcomes more definitively.

- Divide this main goal into subcategories to develop your objectives.

- Limit the number of objectives (1-2 general; 3-4 specific)

- Assess each objective using the SMART

- Start each objective with an action verb like assess, compare, determine, evaluate, etc., which makes the research appear more actionable.

- Use specific language without making the sentence data heavy.

- The most common section to add the objectives is the introduction and after the problem statement.

- Add the objectives to the abstract (if there is one).

- State the general objective first, followed by the specific objectives.

Formulating research objectives

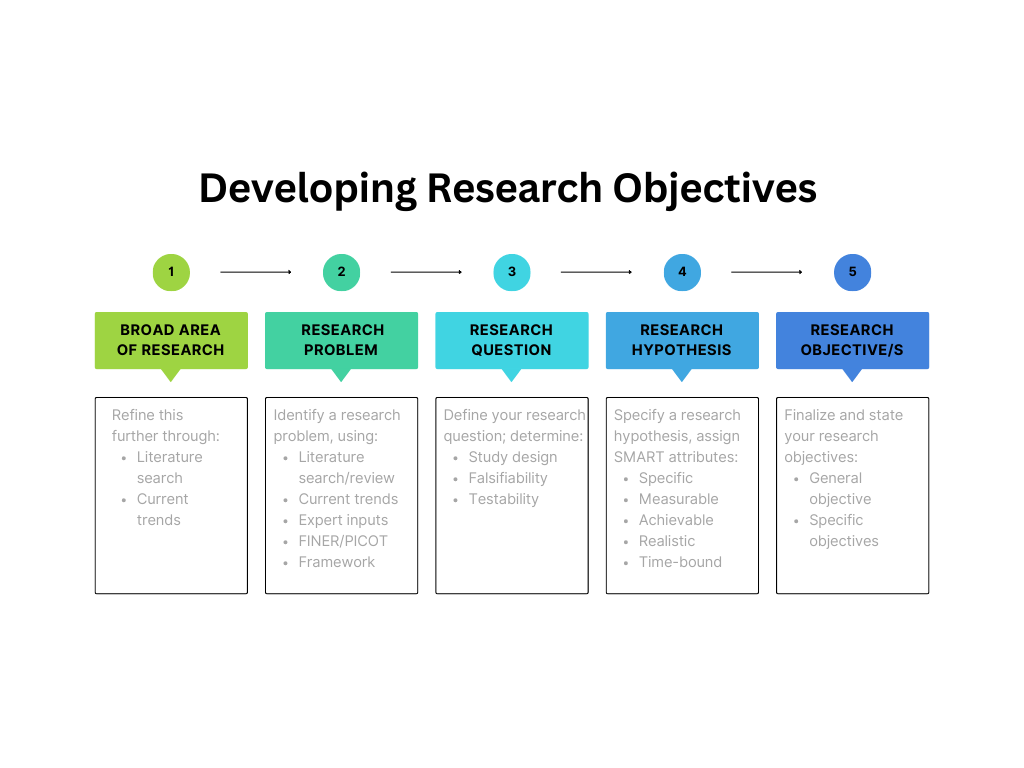

Formulating research objectives has the following five steps, which could help researchers develop a clear objective: 8

- Identify the research problem.

- Review past studies on subjects similar to your problem statement, that is, studies that use similar methods, variables, etc.

- Identify the research gaps the current study should cover based on your literature review. These gaps could be theoretical, methodological, or conceptual.

- Define the research question(s) based on the gaps identified.

- Revise/relate the research problem based on the defined research question and the gaps identified. This is to confirm that there is an actual need for a study on the subject based on the gaps in literature.

- Identify and write the general and specific objectives.

- Incorporate the objectives into the study.

Advantages of research objectives

Adding clear research objectives has the following advantages: 4,8

- Maintains the focus and direction of the research

- Optimizes allocation of resources with minimal wastage

- Acts as a foundation for defining appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Provides measurable outcomes that can help evaluate the success of the research

- Determines the feasibility of the research by helping to assess the availability of required resources

- Ensures relevance of the study to the subject and its contribution to existing literature

Disadvantages of research objectives

Research objectives also have few disadvantages, as listed below: 8

- Absence of clearly defined objectives can lead to ambiguity in the research process

- Unintentional bias could affect the validity and accuracy of the research findings

Key takeaways

- Research objectives are concise statements that describe what the research is aiming to achieve.

- They define the scope and direction of the research and maintain focus.

- The objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

- Clear research objectives help avoid collection of data or resources not required for the study.

- Well-formulated specific objectives help develop the overall research methodology, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization.

- Research objectives should cover all aspects of the problem statement in a coherent way.

- They should be clearly stated using action verbs.

Frequently asked questions on research objectives

Q: what’s the difference between research objectives and aims 9.

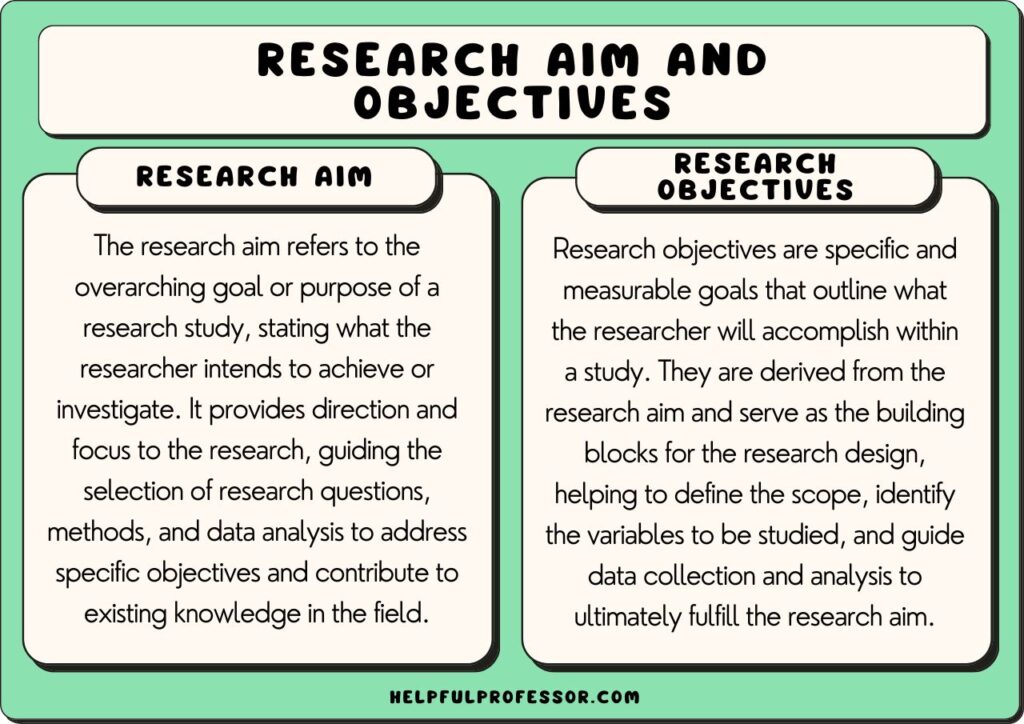

A: Research aims are statements that reflect the broad goal(s) of the study and outline the general direction of the research. They are not specific but clearly define the focus of the study.

Example: This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.

Research objectives focus on the action to be taken to achieve the aims. They make the aims more practical and should be specific and actionable.

Example: To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation.

Q: What are the examples of research objectives, both general and specific?

A: Here are a few examples of research objectives:

- To identify the antiviral chemical constituents in Mumbukura gitoniensis (general)

- To carry out solvent extraction of dried flowers of Mumbukura gitoniensis and isolate the constituents. (specific)

- To determine the antiviral activity of each of the isolated compounds. (specific)

- To examine the extent, range, and method of coral reef rehabilitation projects in five shallow reef areas adjacent to popular tourist destinations in the Philippines.

- To investigate species richness of mammal communities in five protected areas over the past 20 years.

- To evaluate the potential application of AI techniques for estimating best-corrected visual acuity from fundus photographs with and without ancillary information.

- To investigate whether sport influences psychological parameters in the personality of asthmatic children.

Q: How do I develop research objectives?

A: Developing research objectives begins with defining the problem statement clearly, as illustrated by Figure 1. Objectives specify how the research question will be answered and they determine what is to be measured to test the hypothesis.

Q: Are research objectives measurable?

A: The word “measurable” implies that something is quantifiable. In terms of research objectives, this means that the source and method of collecting data are identified and that all these aspects are feasible for the research. Some metrics can be created to measure your progress toward achieving your objectives.

Q: Can research objectives change during the study?

A: Revising research objectives during the study is acceptable in situations when the selected methodology is not progressing toward achieving the objective, or if there are challenges pertaining to resources, etc. One thing to keep in mind is the time and resources you would have to complete your research after revising the objectives. Thus, as long as your problem statement and hypotheses are unchanged, minor revisions to the research objectives are acceptable.

Q: What is the difference between research questions and research objectives? 10

| Broad statement; guide the overall direction of the research | Specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve |

| Identify the main problem | Define the specific outcomes the study aims to achieve |

| Used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge | Used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research |

| Not mutually exclusive with research objectives | Should be directly related to the research question |

| Example: | Example: |

Q: Are research objectives the same as hypotheses?

A: No, hypotheses are predictive theories that are expressed in general terms. Research objectives, which are more specific, are developed from hypotheses and aim to test them. A hypothesis can be tested using several methods and each method will have different objectives because the methodology to be used could be different. A hypothesis is developed based on observation and reasoning; it is a calculated prediction about why a particular phenomenon is occurring. To test this prediction, different research objectives are formulated. Here’s a simple example of both a research hypothesis and research objective.

Research hypothesis : Employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

Research objective : To assess whether employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

To summarize, research objectives are an important part of research studies and should be written clearly to effectively communicate your research. We hope this article has given you a brief insight into the importance of using clearly defined research objectives and how to formulate them.

- Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010 Aug;53(4):278-81.

- Abbadia J. How to write an introduction for a research paper. Mind the Graph website. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/how-to-write-an-introduction-for-a-research-paper/

- Writing a scientific paper: Introduction. UCI libraries website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

- Research objectives—Types, examples and writing guide. Researchmethod.net website. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/research-objectives/#:~:text=They%20provide%20a%20clear%20direction,track%20and%20achieve%20their%20goals .

- Bartle P. SMART Characteristics of good objectives. Community empowerment collective website. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-smar.htm

- Research objectives. Studyprobe website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.studyprobe.in/2022/08/research-objectives.html

- Corredor F. How to write objectives in a research paper. wikiHow website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-Objectives-in-a-Research-Proposal

- Research objectives: Definition, types, characteristics, advantages. AccountingNest website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.accountingnest.com/articles/research/research-objectives

- Phair D., Shaeffer A. Research aims, objectives & questions. GradCoach website. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/

- Understanding the difference between research questions and objectives. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://board.researchersjob.com/blog/research-questions-and-objectives

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Cluster Sampling? Definition, Method, and Examples

Why is Citing Sources Important in Research?

21 Research Objectives Examples (Copy and Paste)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Research objectives refer to the definitive statements made by researchers at the beginning of a research project detailing exactly what a research project aims to achieve.

These objectives are explicit goals clearly and concisely projected by the researcher to present a clear intention or course of action for his or her qualitative or quantitative study.

Research objectives are typically nested under one overarching research aim. The objectives are the steps you’ll need to take in order to achieve the aim (see the examples below, for example, which demonstrate an aim followed by 3 objectives, which is what I recommend to my research students).

Research Objectives vs Research Aims

Research aim and research objectives are fundamental constituents of any study, fitting together like two pieces of the same puzzle.

The ‘research aim’ describes the overarching goal or purpose of the study (Kumar, 2019). This is usually a broad, high-level purpose statement, summing up the central question that the research intends to answer.

Example of an Overarching Research Aim:

“The aim of this study is to explore the impact of climate change on crop productivity.”

Comparatively, ‘research objectives’ are concrete goals that underpin the research aim, providing stepwise actions to achieve the aim.

Objectives break the primary aim into manageable, focused pieces, and are usually characterized as being more specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Examples of Specific Research Objectives:

1. “To examine the effects of rising temperatures on the yield of rice crops during the upcoming growth season.” 2. “To assess changes in rainfall patterns in major agricultural regions over the first decade of the twenty-first century (2000-2010).” 3. “To analyze the impact of changing weather patterns on crop diseases within the same timeframe.”

The distinction between these two terms, though subtle, is significant for successfully conducting a study. The research aim provides the study with direction, while the research objectives set the path to achieving this aim, thereby ensuring the study’s efficiency and effectiveness.

How to Write Research Objectives

I usually recommend to my students that they use the SMART framework to create their research objectives.

SMART is an acronym standing for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. It provides a clear method of defining solid research objectives and helps students know where to start in writing their objectives (Locke & Latham, 2013).

Each element of this acronym adds a distinct dimension to the framework, aiding in the creation of comprehensive, well-delineated objectives.

Here is each step:

- Specific : We need to avoid ambiguity in our objectives. They need to be clear and precise (Doran, 1981). For instance, rather than stating the objective as “to study the effects of social media,” a more focused detail would be “to examine the effects of social media use (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) on the academic performance of college students.”

- Measurable: The measurable attribute provides a clear criterion to determine if the objective has been met (Locke & Latham, 2013). A quantifiable element, such as a percentage or a number, adds a measurable quality. For example, “to increase response rate to the annual customer survey by 10%,” makes it easier to ascertain achievement.

- Achievable: The achievable aspect encourages researchers to craft realistic objectives, resembling a self-check mechanism to ensure the objectives align with the scope and resources at disposal (Doran, 1981). For example, “to interview 25 participants selected randomly from a population of 100” is an attainable objective as long as the researcher has access to these participants.

- Relevance : Relevance, the fourth element, compels the researcher to tailor the objectives in alignment with overarching goals of the study (Locke & Latham, 2013). This is extremely important – each objective must help you meet your overall one-sentence ‘aim’ in your study.

- Time-Bound: Lastly, the time-bound element fosters a sense of urgency and prioritization, preventing procrastination and enhancing productivity (Doran, 1981). “To analyze the effect of laptop use in lectures on student engagement over the course of two semesters this year” expresses a clear deadline, thus serving as a motivator for timely completion.

You’re not expected to fit every single element of the SMART framework in one objective, but across your objectives, try to touch on each of the five components.

Research Objectives Examples

1. Field: Psychology

Aim: To explore the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in college students.

- Objective 1: To compare cognitive test scores of students with less than six hours of sleep and those with 8 or more hours of sleep.

- Objective 2: To investigate the relationship between class grades and reported sleep duration.

- Objective 3: To survey student perceptions and experiences on how sleep deprivation affects their cognitive capabilities.

2. Field: Environmental Science

Aim: To understand the effects of urban green spaces on human well-being in a metropolitan city.

- Objective 1: To assess the physical and mental health benefits of regular exposure to urban green spaces.

- Objective 2: To evaluate the social impacts of urban green spaces on community interactions.

- Objective 3: To examine patterns of use for different types of urban green spaces.

3. Field: Technology

Aim: To investigate the influence of using social media on productivity in the workplace.

- Objective 1: To measure the amount of time spent on social media during work hours.

- Objective 2: To evaluate the perceived impact of social media use on task completion and work efficiency.

- Objective 3: To explore whether company policies on social media usage correlate with different patterns of productivity.

4. Field: Education

Aim: To examine the effectiveness of online vs traditional face-to-face learning on student engagement and achievement.

- Objective 1: To compare student grades between the groups exposed to online and traditional face-to-face learning.

- Objective 2: To assess student engagement levels in both learning environments.

- Objective 3: To collate student perceptions and preferences regarding both learning methods.

5. Field: Health

Aim: To determine the impact of a Mediterranean diet on cardiac health among adults over 50.

- Objective 1: To assess changes in cardiovascular health metrics after following a Mediterranean diet for six months.

- Objective 2: To compare these health metrics with a similar group who follow their regular diet.

- Objective 3: To document participants’ experiences and adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

6. Field: Environmental Science

Aim: To analyze the impact of urban farming on community sustainability.

- Objective 1: To document the types and quantity of food produced through urban farming initiatives.

- Objective 2: To assess the effect of urban farming on local communities’ access to fresh produce.

- Objective 3: To examine the social dynamics and cooperative relationships in the creating and maintaining of urban farms.

7. Field: Sociology

Aim: To investigate the influence of home offices on work-life balance during remote work.

- Objective 1: To survey remote workers on their perceptions of work-life balance since setting up home offices.

- Objective 2: To conduct an observational study of daily work routines and family interactions in a home office setting.

- Objective 3: To assess the correlation, if any, between physical boundaries of workspaces and mental boundaries for work in the home setting.

8. Field: Economics

Aim: To evaluate the effects of minimum wage increases on small businesses.

- Objective 1: To analyze cost structures, pricing changes, and profitability of small businesses before and after minimum wage increases.

- Objective 2: To survey small business owners on the strategies they employ to navigate minimum wage increases.

- Objective 3: To examine employment trends in small businesses in response to wage increase legislation.

9. Field: Education

Aim: To explore the role of extracurricular activities in promoting soft skills among high school students.

- Objective 1: To assess the variety of soft skills developed through different types of extracurricular activities.

- Objective 2: To compare self-reported soft skills between students who participate in extracurricular activities and those who do not.

- Objective 3: To investigate the teachers’ perspectives on the contribution of extracurricular activities to students’ skill development.

10. Field: Technology

Aim: To assess the impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on the tourism industry.

- Objective 1: To document the types and popularity of VR experiences available in the tourism market.

- Objective 2: To survey tourists on their interest levels and satisfaction rates with VR tourism experiences.

- Objective 3: To determine whether VR tourism experiences correlate with increased interest in real-life travel to the simulated destinations.

11. Field: Biochemistry

Aim: To examine the role of antioxidants in preventing cellular damage.

- Objective 1: To identify the types and quantities of antioxidants in common fruits and vegetables.

- Objective 2: To determine the effects of various antioxidants on free radical neutralization in controlled lab tests.

- Objective 3: To investigate potential beneficial impacts of antioxidant-rich diets on long-term cellular health.

12. Field: Linguistics

Aim: To determine the influence of early exposure to multiple languages on cognitive development in children.

- Objective 1: To assess cognitive development milestones in monolingual and multilingual children.

- Objective 2: To document the number and intensity of language exposures for each group in the study.

- Objective 3: To investigate the specific cognitive advantages, if any, enjoyed by multilingual children.

13. Field: Art History

Aim: To explore the impact of the Renaissance period on modern-day art trends.

- Objective 1: To identify key characteristics and styles of Renaissance art.

- Objective 2: To analyze modern art pieces for the influence of the Renaissance style.

- Objective 3: To survey modern-day artists for their inspirations and the influence of historical art movements on their work.

14. Field: Cybersecurity

Aim: To assess the effectiveness of two-factor authentication (2FA) in preventing unauthorized system access.

- Objective 1: To measure the frequency of unauthorized access attempts before and after the introduction of 2FA.

- Objective 2: To survey users about their experiences and challenges with 2FA implementation.

- Objective 3: To evaluate the efficacy of different types of 2FA (SMS-based, authenticator apps, biometrics, etc.).

15. Field: Cultural Studies

Aim: To analyze the role of music in cultural identity formation among ethnic minorities.

- Objective 1: To document the types and frequency of traditional music practices within selected ethnic minority communities.

- Objective 2: To survey community members on the role of music in their personal and communal identity.

- Objective 3: To explore the resilience and transmission of traditional music practices in contemporary society.

16. Field: Astronomy

Aim: To explore the impact of solar activity on satellite communication.

- Objective 1: To categorize different types of solar activities and their frequencies of occurrence.

- Objective 2: To ascertain how variations in solar activity may influence satellite communication.

- Objective 3: To investigate preventative and damage-control measures currently in place during periods of high solar activity.

17. Field: Literature

Aim: To examine narrative techniques in contemporary graphic novels.

- Objective 1: To identify a range of narrative techniques employed in this genre.

- Objective 2: To analyze the ways in which these narrative techniques engage readers and affect story interpretation.

- Objective 3: To compare narrative techniques in graphic novels to those found in traditional printed novels.

18. Field: Renewable Energy

Aim: To investigate the feasibility of solar energy as a primary renewable resource within urban areas.

- Objective 1: To quantify the average sunlight hours across urban areas in different climatic zones.

- Objective 2: To calculate the potential solar energy that could be harnessed within these areas.

- Objective 3: To identify barriers or challenges to widespread solar energy implementation in urban settings and potential solutions.

19. Field: Sports Science

Aim: To evaluate the role of pre-game rituals in athlete performance.

- Objective 1: To identify the variety and frequency of pre-game rituals among professional athletes in several sports.

- Objective 2: To measure the impact of pre-game rituals on individual athletes’ performance metrics.

- Objective 3: To examine the psychological mechanisms that might explain the effects (if any) of pre-game ritual on performance.

20. Field: Ecology

Aim: To investigate the effects of urban noise pollution on bird populations.

- Objective 1: To record and quantify urban noise levels in various bird habitats.

- Objective 2: To measure bird population densities in relation to noise levels.

- Objective 3: To determine any changes in bird behavior or vocalization linked to noise levels.

21. Field: Food Science

Aim: To examine the influence of cooking methods on the nutritional value of vegetables.

- Objective 1: To identify the nutrient content of various vegetables both raw and after different cooking processes.

- Objective 2: To compare the effect of various cooking methods on the nutrient retention of these vegetables.

- Objective 3: To propose cooking strategies that optimize nutrient retention.

The Importance of Research Objectives

The importance of research objectives cannot be overstated. In essence, these guideposts articulate what the researcher aims to discover, understand, or examine (Kothari, 2014).

When drafting research objectives, it’s essential to make them simple and comprehensible, specific to the point of being quantifiable where possible, achievable in a practical sense, relevant to the chosen research question, and time-constrained to ensure efficient progress (Kumar, 2019).

Remember that a good research objective is integral to the success of your project, offering a clear path forward for setting out a research design , and serving as the bedrock of your study plan. Each objective must distinctly address a different dimension of your research question or problem (Kothari, 2014). Always bear in mind that the ultimate purpose of your research objectives is to succinctly encapsulate your aims in the clearest way possible, facilitating a coherent, comprehensive and rational approach to your planned study, and furnishing a scientific roadmap for your journey into the depths of knowledge and research (Kumar, 2019).

Kothari, C.R (2014). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques . New Delhi: New Age International.

Kumar, R. (2019). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners .New York: SAGE Publications.

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management review, 70 (11), 35-36.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance . New York: Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Number Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Word Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Outdoor Games for Kids

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 50 Incentives to Give to Students

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Objectives: The Compass of Your Study

Table of contents

- 1 Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

- 2 How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

- 3 Types of Research Objectives

- 4 Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

- 5 Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

- 6.1 Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

- 6.2 Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

- 6.3 How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

- 7 Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

- 8 Conclusion

Embarking on a research journey without clear objectives is like navigating the sea without a compass. This article delves into the essence of establishing precise research objectives, serving as the guiding star for your scholarly exploration.

We will unfold the layers of how the objective of study not only defines the scope of your research but also directs every phase of the research process, from formulating research questions to interpreting research findings. By bridging theory with practical examples, we aim to illuminate the path to crafting effective research objectives that are both ambitious and attainable. Let’s chart the course to a successful research voyage, exploring the significance, types, and formulation of research paper objectives.

Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

Defining the research objectives includes which two tasks? Research objectives are clear and concise statements that outline what you aim to achieve through your study. They are the foundation for determining your research scope, guiding your data collection methods, and shaping your analysis. The purpose of research proposal and setting clear objectives in it is to ensure that your research efforts are focused and efficient, and to provide a roadmap that keeps your study aligned with its intended outcomes.

To define the research objective at the outset, researchers can avoid the pitfalls of scope creep, where the study’s focus gradually broadens beyond its initial boundaries, leading to wasted resources and time. Clear objectives facilitate communication with stakeholders, such as funding bodies, academic supervisors, and the broader academic community, by succinctly conveying the study’s goals and significance. Furthermore, they help in the formulation of precise research questions and hypotheses, making the research process more systematic and organized. Yet, it is not always easy. For this reason, PapersOwl is always ready to help. Lastly, clear research objectives enable the researcher to critically assess the study’s progress and outcomes against predefined benchmarks, ensuring the research stays on track and delivers meaningful results.

How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

Research objectives are integral to the research framework as the nexus between the research problem, questions, and hypotheses. They translate the broad goals of your study into actionable steps, ensuring every aspect of your research is purposefully aligned towards addressing the research problem. This alignment helps in structuring the research design and methodology, ensuring that each component of the study is geared towards answering the core questions derived from the objectives. Creating such a difficult piece may take a lot of time. If you need it to be accurate yet fast delivered, consider getting professional research paper writing help whenever the time comes. It also aids in the identification and justification of the research methods and tools used for data collection and analysis, aligning them with the objectives to enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

Furthermore, by setting clear objectives, researchers can more effectively evaluate the impact and significance of their work in contributing to existing knowledge. Additionally, research objectives guide literature review, enabling researchers to focus their examination on relevant studies and theoretical frameworks that directly inform their research goals.

Types of Research Objectives

In the landscape of research, setting objectives is akin to laying down the tracks for a train’s journey, guiding it towards its destination. Constructing these tracks involves defining two main types of objectives: general and specific. Each serves a unique purpose in guiding the research towards its ultimate goals, with general objectives providing the broad vision and specific objectives outlining the concrete steps needed to fulfill that vision. Together, they form a cohesive blueprint that directs the focus of the study, ensuring that every effort contributes meaningfully to the overarching research aims.

- General objectives articulate the overarching goals of your study. They are broad, setting the direction for your research without delving into specifics. These objectives capture what you wish to explore or contribute to existing knowledge.

- Specific objectives break down the general objectives into measurable outcomes. They are precise, detailing the steps needed to achieve the broader goals of your study. They often correspond to different aspects of your research question , ensuring a comprehensive approach to your study.

To illustrate, consider a research project on the impact of digital marketing on consumer behavior. A general objective might be “to explore the influence of digital marketing on consumer purchasing decisions.” Specific objectives could include “to assess the effectiveness of social media advertising in enhancing brand awareness” and “to evaluate the impact of email marketing on customer loyalty.”

Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

The harmony between what research objectives should be, questions, and hypotheses is critical. Objectives define what you aim to achieve; research questions specify what you seek to understand, and hypotheses predict the expected outcomes.

This alignment ensures a coherent and focused research endeavor. Achieving it necessitates a thoughtful consideration of how each component interrelates, ensuring that the objectives are not only ambitious but also directly answerable through the research questions and testable via the hypotheses. This interconnectedness facilitates a streamlined approach to the research process, enabling researchers to systematically address each aspect of their study in a logical sequence. Moreover, it enhances the clarity and precision of the research, making it easier for peers and stakeholders to grasp the study’s direction and potential contributions.

Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

Throughout the research process, objectives guide your choices and strategies – from selecting the appropriate research design and methods to analyzing data and interpreting results. They are the criteria against which you measure the success of your study. In the initial stages, research objectives inform the selection of a topic, helping to narrow down a broad area of interest into a focused question that can be explored in depth. During the methodology phase, they dictate the type of data needed and the best methods for obtaining that data, ensuring that every step taken is purposeful and aligned with the study’s goals. As the research progresses, objectives provide a framework for analyzing the collected data, guiding the researcher in identifying patterns, drawing conclusions, and making informed decisions.

Crafting Effective Research Objectives

The effective objective of research is pivotal in laying the groundwork for a successful investigation. These objectives clarify the focus of your study and determine its direction and scope. Ensuring that your objectives are well-defined and aligned with the SMART criteria is crucial for setting a strong foundation for your research.

Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

Well-defined research objectives are characterized by the SMART criteria – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Specific objectives clearly define what you plan to achieve, eliminating any ambiguity. Measurable objectives allow you to track progress and assess the outcome. Achievable objectives are realistic, considering the research sources and time available. Relevant objectives align with the broader goals of your field or research question. Finally, Time-bound objectives have a clear timeline for completion, adding urgency and a schedule to your work.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

So lets get to the part, how to write research objectives properly?

- Understand the issue or gap in existing knowledge your study aims to address.

- Gain insights into how similar challenges have been approached to refine your objectives.

- Articulate the broad goal of research based on your understanding of the problem.

- Detail the specific aspects of your research, ensuring they are actionable and measurable.

How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

Your objectives of research may require refinement if they lack clarity, feasibility, or alignment with the research problem. If you find yourself struggling to design experiments or methods that directly address your objectives, or if the objectives seem too broad or not directly related to your research question, it’s likely time for refinement. Additionally, objectives in research proposal that do not facilitate a clear measurement of success indicate a need for a more precise definition. Refinement involves ensuring that each objective is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound, enhancing your research’s overall focus and impact.

Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

The application of research objectives spans various academic disciplines, each with its unique focus and methodologies. To illustrate how the objectives of the study guide a research paper across different fields, here are some research objective examples:

- In Health Sciences , a research aim may be to “determine the efficacy of a new vaccine in reducing the incidence of a specific disease among a target population within one year.” This objective is specific (efficacy of a new vaccine), measurable (reduction in disease incidence), achievable (with the right study design and sample size), relevant (to public health), and time-bound (within one year).

- In Environmental Studies , the study objectives could be “to assess the impact of air pollution on urban biodiversity over a decade.” This reflects a commitment to understanding the long-term effects of human activities on urban ecosystems, emphasizing the need for sustainable urban planning.

- In Economics , an example objective of a study might be “to analyze the relationship between fiscal policies and unemployment rates in developing countries over the past twenty years.” This seeks to explore macroeconomic trends and inform policymaking, highlighting the role of economic research study in societal development.

These examples of research objectives describe the versatility and significance of research objectives in guiding scholarly inquiry across different domains. By setting clear, well-defined objectives, researchers can ensure their studies are focused and impactful and contribute valuable knowledge to their respective fields.

Defining research studies objectives and problem statement is not just a preliminary step, but a continuous guiding force throughout the research journey. These goals of research illuminate the path forward and ensure that every stride taken is meaningful and aligned with the ultimate goals of the inquiry. Whether through the meticulous application of the SMART criteria or the strategic alignment with research questions and hypotheses, the rigor in crafting and refining these objectives underscores the integrity and relevance of the research. As scholars venture into the vast terrains of knowledge, the clarity, and precision of their objectives serve as beacons of light, steering their explorations toward discoveries that advance academic discourse and resonate with the broader societal needs.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write Research Objectives

- 3-minute read

- 22nd November 2021

Writing a research paper, thesis, or dissertation ? If so, you’ll want to state your research objectives in the introduction of your paper to make it clear to your readers what you’re trying to accomplish. But how do you write effective research objectives? In this post, we’ll look at two key topics to help you do this:

- How to use your research aims as a basis for developing objectives.

- How to use SMART criteria to refine your research objectives.

For more advice on how to write strong research objectives, see below.

Research Aims and Objectives

There is an important difference between research aims and research objectives:

- A research aim defines the main purpose of your research. As such, you can think of your research aim as answering the question “What are you doing?”

- Research objectives (as most studies will have more than one) are the steps you will take to fulfil your aims. As such, your objectives should answer the question “How are you conducting your research?”

For instance, an example research aim could be:

This study will investigate the link between dehydration and the incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in intensive care patients in Australia.

To develop a set of research objectives, you would then break down the various steps involved in meeting said aim. For example:

This study will investigate the link between dehydration and the incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in intensive care patients in Australia. To achieve this, the study objectives w ill include:

- Replicat ing a small Singaporean study into the role of dehydration in UTIs in hospital patients (Sepe, 2018) in a larger Australian cohort.

- Trialing the use of intravenous fluids for intensive care patients to prevent dehydration.

- Assessing the relationship between the age of patients and quantities of intravenous fluids needed to counter dehydration.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Note that the objectives don’t go into any great detail here. The key is to briefly summarize each component of your study. You can save details for how you will conduct the research for the methodology section of your paper.

Make Your Research Objectives SMART

A great way to refine your research objectives is to use SMART criteria . Borrowed from the world of project management, there are many versions of this system. However, we’re going to focus on developing specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timebound objectives.

In other words, a good research objective should be all of the following:

- S pecific – Is the objective clear and well-defined?

- M easurable – How will you know when the objective has been achieved? Is there a way to measure the thing you’re seeking to do?

- A chievable – Do you have the support and resources necessary to undertake this action? Are you being overly ambitious with this objective?

- R elevant – Is this objective vital for fulfilling your research aim?

- T imebound – Can this action be realistically undertaken in the time you have?

If you follow this system, your research objectives will be much stronger.

Expert Research Proofreading

Whatever your research aims and objectives, make sure to have your academic writing proofread by the experts!

Our academic editors can help you with research papers and proposals , as well as any other scholarly document you need checking. And this will help to ensure that your academic writing is always clear, concise, and precise.

Submit a free sample document today to trial our services and find out more.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Crafting Clear Pathways: Writing Objectives in Research Papers

Struggling to write research objectives? Follow our easy steps to learn how to craft effective and compelling objectives in research papers.

Are you struggling to define the goals and direction of your research? Are you losing yourself while doing research and tend to go astray from the intended research topic? Fear not, as many face the same problem and it is quite understandable to overcome this, a concept called research objective comes into play here.

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of the objectives in research papers and why they are essential for a successful study. We will be studying what they are and how they are used in research.

What is a Research Objective?

A research objective is a clear and specific goal that a researcher aims to achieve through a research study. It serves as a roadmap for the research, providing direction and focus. Research objectives are formulated based on the research questions or hypotheses, and they help in defining the scope of the study and guiding the research design and methodology. They also assist in evaluating the success and outcomes of the research.

Types of Research Objectives

There are typically three main types of objectives in a research paper:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are focused on gaining a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon, topic, or issue. Exploratory research objectives aim to explore and identify new ideas, insights, or patterns that were previously unknown or poorly understood. This type of objective is commonly used in preliminary or qualitative studies.

- Descriptive Objectives: Descriptive objectives seek to describe and document the characteristics, behaviors, or attributes of a specific population, event, or phenomenon. The purpose is to provide a comprehensive and accurate account of the subject of study. Descriptive research objectives often involve collecting and analyzing data through surveys, observations, or archival research.

- Explanatory or Causal Objectives: Explanatory objectives aim to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between variables or factors. These objectives focus on understanding why certain events or phenomena occur and how they are related to each other.

Also Read: What are the types of research?

Steps for Writing Objectives in Research Paper

1. identify the research topic:.

Clearly define the subject or topic of your research. This will provide a broad context for developing specific research objectives.

2. Conduct a Literature Review

Review existing literature and research related to your topic. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge, identify any research gaps, and refine your research objectives accordingly.

3. Identify the Research Questions or Hypotheses

Formulate specific research questions or hypotheses that you want to address in your study. These questions should be directly related to your research topic and guide the development of your research objectives.

4. Focus on Specific Goals

Break down the broader research questions or hypothesis into specific goals or objectives. Each objective should focus on a particular aspect of your research topic and be achievable within the scope of your study.

5. Use Clear and Measurable Language

Write your research objectives using clear and precise language. Avoid vague terms and use specific and measurable terms that can be observed, analyzed, or measured.

6. Consider Feasibility

Ensure that your research objectives are feasible within the available resources, time constraints, and ethical considerations. They should be realistic and attainable given the limitations of your study.

7. Prioritize Objectives

If you have multiple research objectives, prioritize them based on their importance and relevance to your overall research goals. This will help you allocate resources and focus your efforts accordingly.

8. Review and Refine

Review your research objectives to ensure they align with your research questions or hypotheses, and revise them if necessary. Seek feedback from peers or advisors to ensure clarity and coherence.

Tips for Writing Objectives in Research Paper

1. be clear and specific.

Clearly state what you intend to achieve with your research. Use specific language that leaves no room for ambiguity or confusion. This ensures that your objectives are well-defined and focused.

2. Use Action Verbs

Begin each research objective with an action verb that describes a measurable action or outcome. This helps make your objectives more actionable and measurable.

3. Align with Research Questions or Hypotheses

Your research objectives should directly address the research questions or hypotheses you have formulated. Ensure there is a clear connection between them to maintain coherence in your study.

4. Be Realistic and Feasible

Set research objectives that are attainable within the constraints of your study, including available resources, time, and ethical considerations. Unrealistic objectives may undermine the validity and reliability of your research.

5. Consider Relevance and Significance

Your research objectives should be relevant to your research topic and contribute to the broader field of study. Consider the potential impact and significance of achieving the objectives.

SMART Goals for Writing Research Objectives

To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and effectively guide your study, you can apply the SMART framework. SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Here’s how you can make your research objectives SMART:

- Specific : Clearly state what you want to achieve in a precise and specific manner. Avoid vague or generalized language. Specify the population, variables, or phenomena of interest.

- Measurable : Ensure that your research objectives can be quantified or observed in a measurable way. This allows for objective evaluation and assessment of progress.

- Achievable : Set research objectives that are realistic and attainable within the available resources, time, and scope of your study. Consider the feasibility of conducting the research and collecting the necessary data.

- Relevant : Ensure that your research objectives are directly relevant to your research topic and contribute to the broader knowledge or understanding of the field. They should align with the purpose and significance of your study.

- Time-bound : Set a specific timeframe or deadline for achieving your research objectives. This helps create a sense of urgency and provides a clear timeline for your study.

Examples of Research Objectives

Here are some examples of research objectives from various fields of study:

- To examine the relationship between social media usage and self-esteem among young adults aged 18-25 in order to understand the potential impact on mental well-being.

- To assess the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention in reducing stress levels and improving coping mechanisms among individuals diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

- To investigate the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the e-commerce industry, with a focus on the role of online reviews and social media influencers.

- To analyze the effects of climate change on the biodiversity of coral reefs in a specific region, using remote sensing techniques and field surveys.

Importance of Research Objectives

Research objectives play a crucial role in the research process and hold significant importance for several reasons:

- Guiding the Research Process: Research objectives provide a clear roadmap for the entire research process. They help researchers stay focused and on track, ensuring that the study remains purposeful and relevant.

- Defining the Scope of the Study: Research objectives help in determining the boundaries and scope of the study. They clarify what aspects of the research topic will be explored and what will be excluded.

- Providing Direction for Data Collection and Analysis: Research objectives assist in identifying the type of data to be collected and the methods of data collection. They also guide the selection of appropriate data analysis techniques.

- Evaluating the Success of the Study: Research objectives serve as benchmarks for evaluating the success and outcomes of the research. They provide measurable criteria against which the researcher can assess whether the objectives have been met or not.

- Enhancing Communication and Collaboration: Clearly defined research objectives facilitate effective communication and collaboration among researchers, advisors, and stakeholders.

Common Mistakes to Avoid While Writing Research Objectives

When writing research objectives, it’s important to be aware of common mistakes and pitfalls that can undermine the effectiveness and clarity of your objectives. Here are some common mistakes to avoid:

- Vague or Ambiguous Language: One of the key mistakes is using vague or ambiguous language that lacks specificity. Ensure that your research objectives are clearly and precisely stated, leaving no room for misinterpretation or confusion.

- Lack of Measurability: Research objectives should be measurable, meaning that they should allow for the collection of data or evidence that can be quantified or observed. Avoid setting objectives that cannot be measured or assessed objectively.

- Lack of Alignment with Research Questions or Hypotheses: Your research objectives should directly align with the research questions or hypotheses you have formulated. Make sure there is a clear connection between them to maintain coherence in your study.

- Overgeneralization : Avoid writing research objectives that are too broad or encompass too many variables or phenomena. Overgeneralized objectives may lead to a lack of focus or feasibility in conducting the research.

- Unrealistic or Unattainable Objectives: Ensure that your research objectives are realistic and attainable within the available resources, time, and scope of your study. Setting unrealistic objectives may compromise the validity and reliability of your research.