The website will be down for maintenance from 6:00 a.m. to noon CDT on Sunday, June 30.

Clinical Practice Guideline Manual

Introduction

I. Development of Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs)

II. Joint Development of CPGs with External Organizations (CMSS P 9)

III. Identification of a CPG Clinical Topic

IV. Systematic Evidence Review of CPG Clinical Topic (IOM Standard 4)

V. Development of CPG Panel (IOM Standards 3; CMSS-P 4)

VI. Conflict of Interest (COI) Policy and Process (IOM Standard 2, CMSS-P 3, CMSS-C 7.5-7.8)

VII. Clinical Practice Guideline Panel Collaboration

VIII. Review of Published Evidence Report (IOM Standard 4)

IX. Grading Evidence and Strength of Recommendation (CMSS-P 6; IOM Standards 5 and 6)

X. Writing the Guideline

XI. CPG Peer Review (the following sections are in accordance with IOM 7, CMSS-P 7, and CMSS-C 7,9, 7.11, 7.15)

XII. AAFP Approval Process (CMSS-P 7.1 and CMSS-C 7.9)

XIII. Publication (CMSS-P 7.2.2 and 9, CMSS-C 7.11)

XIV. Dissemination (CMSS-P 9.2-9.4)

XV. Five-Year Update of CPG (IOM Standard 8 and CMSS-P 8)

XVI. Endorsement of External Guidelines

APPENDIX OF USEFUL RESOURCES

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) develops evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), which serve as a framework for clinical decisions and supporting best practices. Clinical practice guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care. They are informed by a systematic review of evidence, and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. CPGs should follow a sound, transparent methodology to translate best evidence into clinical practice for improved patient outcomes. Additionally, evidence-based CPGs are a key aspect of patient-centered care.

This manual summarizes the processes used by the AAFP to produce high-quality, evidence-based guidelines. The AAFP’s development process adheres to the following standards and principles:

- Institute of Medicine (IOM): Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust—Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs)

- Council on Medical Specialty Societies: Principles for the Development of Specialty Society Clinical Guidelines

- Council on Medical Specialty Societies: Code for Interactions with Companies

Clinical practice guidelines should be developed using rigorous evidence-based methodology with the strength of evidence for each guideline explicitly stated.

- Clinical practice guidelines should be feasible, measurable, and achievable.

- Clinical performance measures may be developed from clinical practice guidelines and used in quality improvement initiatives. When these performance measures are incorporated into public reporting, accountability, or pay for performance programs, the strength of evidence and magnitude of benefit should be sufficient to justify the burden of implementation.

- In the clinical setting, implementation of clinical practice guidelines should be prioritized to those that have the strongest supporting evidence, and the most impact on patient population morbidity and mortality.

- Research should be conducted on how to effectively implement clinical practice guidelines, and the impact of their use as quality measures.

a. Definition: Clinical practice guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. Rather than dictating a one-size-fits-all approach to patient care, clinical practice guidelines offer an evaluation of the quality of the relevant scientific literature, and an assessment of the likely benefits and harms of a particular treatment. This information enables health care clinicians to select the best care for a unique patient based on his or her preferences.

b. AAFP’s Commission on Health of the Public and Science (CHPS) and Board of Directors provides oversight for the development and approval of its clinical practice guidelines.

c. Principles for Development (IOM 1.1, CMSS-P 11, CMSS-C): The IOM identified eight standards for developing trustworthy guidelines. The standards reflect best practices across the entire guideline development process, including attention to:

- Establishing transparency;

- Managing conflict of interest;

- Guideline development group composition;

- Clinical practice guideline–systematic review intersection;

- Establishing evidence foundations for and rating strength of recommendations;

- Articulation of recommendations;

- External review; and

The Council of Medical Specialty Societies (CMSS) provides directions and standards for the development of clinical practice guidelines through the CMSS Principles for Guideline Development (CMSS-P) and the Code for Interactions with Companies (CMSS-C). Where possible, the standards outlined by the IOM (now the National Academies of Medicine) and CMSS are referenced in the corresponding sections below.

The AAFP advocates the development of explicit patient-centered clinical practice guidelines which focus on what should be done for patients rather than who should do it. When clinical practice guidelines address the issue of who should provide care, then recommendations for management, consultation, or referral should emphasize appropriate specific competencies rather than a clinician's specialty designation. The AAFP may participate with other medical organizations in the development of clinical practice guidelines (also known as practice parameters or clinical policies) when appropriate criteria are met.

When AAFP enters into a joint development of a CPG with external organizations, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) should be developed to guide the process.

a. A clinical topic for a new or updated CPG is first vetted by the Subcommittee on Clinical Recommendations and Policies (SCRP) of CHPS using the following criteria:

- Relevance to family medicine

- No current evidence-based guidelines on the topic available that are suitable for use by family physicians

- Guidance on this topic will support AAFP Strategic Objectives and Strategies

- A systematic evidence report is available, the topic can be nominated to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), or there is a funding source for creation of an evidence review.

b. AAFP Board approval is obtained for topic nomination and collaborators.

c. Prior to topic nomination, potential co-nominators/collaborators are contacted to involve them in the process.

In most cases, the AAFP utilizes the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for development of an independent systematic review of the evidence based on the key questions identified for the CPG.

a. Develop topic nomination proposal to AHRQ (CMSS P 5)

i. Include key clinical questions and parameters with patient-oriented outcomes prioritized ii. Members and content experts assist in drafting and providing feedback on the key questions iii. Include collaborators for co-nomination (if applicable)

b. AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC)

i. Establish staff contact with AHRQ program officer and EPC staff for evidence report ii. Include one or more family physicians to serve on the technical expert panel (TEP) of the EPC. Often the TEP members will also serve on the guideline development panel.

c. AHRQ EPC Evidence Report on Clinical Topic

i. Staff and SCPG members provide review and feedback on the draft evidence report as requested by AHRQ throughout the process ii. The draft report can be used to begin development of the draft CPG iii. When the final EPC evidence report is published and available, it is used to finalize the CPG.

Staff works with the chairs of SCRP and CHPS to form the Guideline Development Group using the process outlined below:

a. Identify AAFP GDG Chair through the CHPS and obtain approval from the Board of Directors b. Identify family physicians panel members including at least one member of SCPG and one member of the Science Advisory Panel in addition to other CHPS and AAFP members. c. Identify GDG members from collaborators including a patient representative or patient advocacy group(s) when available/appropriate d. Obtain a Disclosure of Interest Form from all panel members (IOM Standards 2)

A conflict of interest (COI) is an important potential source of bias in the development of CPGs. A COI has been defined as a set of conditions in which professional judgment concerning a primary interest (guideline recommendations), is unduly influenced by a secondary interest (financial or intellectual interests) (Norris et al 2012 and Thompson DF 1993) .

To limit both actual and perceived bias in guideline development, the AAFP has set forth the following policy for COI:

- Whenever possible GDG members should not have COI.

- The chair or co-chairs should not be a person(s) with COI.

- The chair or co-chairs should remain conflict free for one year following publication.

- Members with COIs should not represent a majority the GDG.

- Funders should have no role in CPG development.

a. Prior to selection of the Guideline Development Group (GDG), individuals being considered for membership should declare all interests and activities potentially resulting in COI with development group activity, by written disclosure to those convening the GDG.

- Disclosures should include activities relevant to the scope of the CPG for the both the potential member as well as members of their immediate family (spouse/partner, parents, siblings, children)

- Disclosures should include current and planned activities in addition to activities for up to three years prior to convening of the GDG.

b. Disclosures should include activities that may be considered financial or intellectual COI as defined below:

i. Financial COI = material interest that could influence, or be perceived as influencing, an individual’s point of view

- Includes any industry funding (even if not related to guideline topic)

- Outside of industry funding, includes activities related to the guideline topic: consultant, expert witness, stock ownership/options, research funding, speaker’s bureau

- Includes other financial interests related to health care that may be relevant

ii. Intellectual COI = “…activities that create the potential for an attachment to a specific point of view that could unduly affect an individual’s judgement about a specific recommendation” (Guyatt et al 2010).

- Includes, but not limited to, authorship of a publication, participation in research, participation on a workgroup/panel with medical specialty society or health care organization, lobbying or advocacy, or public presentation of a view point related to the guideline (blog, editorial, etc)

c. Review and Management of COIs

- Disclosures for each potential member will be reviewed by staff and the chair of the GDG prior to placement on the panel.

- If a disclosure is determined to represent a conflict of interest, potential actions include exclusion from the panel or limits on participation in discussions or voting on relevant recommendations.

- Each panel member will update any COI (verbally or in person) at each meeting of the GDG.

d. Divestment Members of the GDG should divest themselves of financial investments they or their family members have, and not participate in marketing activities or advisory boards, of entities whose interests could be affected by CPG recommendations.

e. Exclusions In some circumstances, a GDG may not be able to perform its work without members who have COIs, such as relevant clinical specialists who receive a substantial portion of their incomes from services pertinent to the CPG.

a. Clinical practice guideline time-line and expectations AAFP staff members, in collaboration with the GDG chair, will develop a time-line for the guideline being developed. This time-line will be distributed to GDG members during the first meeting of the GDG. Though this time-line is developed with the goal of adherence, it is recognized that circumstances during the development process may affect the time-line. Thus, this is a living document throughout the guideline process and should be updated as appropriate.

Expectations of GDG members and staff will be reviewed by the GDG chair during the first meeting of the GDG.

- Writing assignments: Writing assignments may be made throughout the guideline development process. GDG members will be asked to volunteer for certain tasks and may be assigned to subgroups to develop recommendations and write supporting evidence for those recommendations.

- Deadlines: Clear deadlines will be agreed upon during the process of guideline development. However, as stated above, circumstances during the CPG development process may arise that warrant adjusting deadlines. The panel chair and staff members at the AAFP will work with the GDG on any changes in deadlines.

b. CPG outline The GDG will work with the GDG chair and AAFP staff members to develop an outline of the proposed guideline. The outline will include the key questions from the evidence report, the potential draft recommendations, key points for supporting text, and identification of potential information for shared decision-making tables and implementation algorithms.

c. Conference calls Conference calls will be convened at the start of the guideline development process and throughout as needed. AAFP staff members will work with GDG members to ensure availability for calls. When a member cannot be present on a call, that member will be provided opportunities to provide any written comments prior to the call and feedback to the meeting summary after the call.

d. Electronic communication Electronic communication will be used throughout the guideline process. Reasonable response times are expected for electronic communications and deadlines for requested action items will be clearly stated in the communications from AAFP staff members.

d. CPG publication(s) and dissemination (CMSS P 9) When AAFP collaborates with others on a joint guideline, it will be decided where publication is expected at the start of the collaboration. All parties will agree to the publication plan. For guidelines developed solely by the AAFP, the GDG and staff will identify an appropriate publication venue which may include a peer-reviewed journal and/or the AAFP website. Dissemination activities should also be identified early on to facilitate work load and collaboration. These activities can include one or more of the following:

- Press release

- National Guideline Clearinghouse or Guidelines International Network Database

- Derivative creation either by AAFP, collaborator, or other commercial entity

a. Section IV of this manual described the AAFP process for nominating topics to AHRQ for a systematic review of the evidence. Once the systematic review has been completed, a draft evidence report is published by AHRQ. The GDG reviews the draft evidence report to determine if applicable for development of a guideline. Systematic literature review performed by the AAFP.

If more than 12 months has passed between the publication of an AHRQ evidence review and development of the guideline, an update of the systematic review will be conducted. The GDG and AAFP staff members will work with the AAFP librarian to perform the updated review. The librarian will use the same search criteria that were used in the AHRQ systematic review. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be set a priori to determine which studies will be reviewed for quality. AAFP staff members review the updated search results and obtain articles relevant to the systematic review.

b. As outlined in section IV, AHRQ has a process for performing systematic reviews that is consistent with the 2011 Standards for Systematic Reviews from the IOM. The AAFP also uses this as a guide to ensure the systematic literature reviews we are performing or that we are using for guideline development are compliant with the best standards available. These standards include: establishing a team with appropriate experience and expertise to do the review, including those with content expertise; providing methodological expertise and other expertise as appropriate; ensuring any conflict of interest is managed with regard to the team; ensuring that there is user and stakeholder input as the review is designed and conducted; managing conflict of interest with regard to any individuals providing input into the review; and formulating the topic for review.

The standards also discuss “finding and assessing individual studies.” This includes steps such as:

i. Conducting a comprehensive search for the evidence. This step will likely include:

a. Working with a librarian, and

b. Searching appropriate databases, citation indexes and other sources for relevant information.

ii. Taking action to address potential bias in reporting of research results.

iii. Screening and selecting relevant studies. Here it is very important to include and exclude studies based on a priori specified criteria developed in the protocol. It is recommended that two or more people screen studies and that these reviewers are tested for accuracy and consistency in their reviews.

iv. Documenting the search strategy, including dates of searches and how each item identified in the search was addressed. If excluded, include the reason for exclusion.

v. If data is extracted for a meta-analysis, data collection should be managed appropriately. The IOM standards recommend that systematic review developers:

a. Use two or more researchers to extract relevant data from a report;

b. Link publications from the same studies to avoid duplication of data; and

c. Use data extraction forms that are pilot tested.

vi. Finally, at least two reviewers should critically appraise each study using the specified protocol and forms derived for the review.

Compiling evidence and assessing it for quality are important steps in a systematic review. The quality of the evidence should be linked to the strength of the recommendations in that guideline. Consistent with the IOM standards for systematic reviews, the AAFP uses a specified framework for assessing the quality of studies and providing strength for each recommendation.

a. GRADE methodology The AAFP uses a modified version of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method to systematically examine research to rate the quality of the evidence, and designate the strength of a recommendation based upon that evidence. The GRADE system provides a transparent process and framework for developing evidence-based recommendations using the following system to rate the quality of evidence:

i. High Quality (Level A): Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. ii. Moderate Quality (Level B): Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate. iii. Low Quality (Level C): Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and is likely to change the estimate. iv. Very Low Quality (Level D): Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

b. Strength of Recommendation GRADE uses the term “strength of recommendation” to rate the extent of confidence that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh the undesirable effects. Recommendations can be either for or against an intervention or testing modality. The AAFP prefers the strength of the recommendation be consistent with the quality of the evidence such that strong recommendations are based on moderate to high quality evidence and weak recommendations are based on low to moderate quality evidence. Very low-quality evidence should be considered insufficient for a recommendation except when the benefits greatly outweigh the harms.

The strength of evidence should also reflect the degree to which there is evidence of improved patient oriented outcomes such as morbidity, mortality, quality of life, or symptoms (as opposed to only disease oriented outcomes such as blood pressure or hemoglobin A1C). Strong recommendations should be based on high quality evidence of improved patient oriented outcomes. Weak recommendations should be supported by some evidence of improvement in patient oriented outcomes; although, the evidence may be inconsistent, of lower quality, or rely on an indirect chain linking surrogate outcomes to patient oriented outcomes.

i. Strong recommendation: Based on consistent evidence of a net benefit in terms of patient oriented health outcomes, most informed patients would choose the option recommended, and clinicians can structure their interactions with patients accordingly.

ii. Weak recommendation: Evidence of a net benefit in terms of patient oriented outcomes is inconsistent or is based on lower quality evidence, or patient choices will vary based upon their values and preferences, and clinicians must help to ensure that patient care stays true to these values and preferences.

iii. Good practice points: These are recommendations that can be made when it is deemed they will be helpful to the clinician, such as recommendations to perform something that is standard of care, but where there is no direct evidence to support the recommendation and that is unlikely to ever be formally studied. These should be used sparingly in guidelines.

c. Upgrading and downgrading evidence: The GRADE system allows the evidence to be upgraded or downgraded based upon specific criteria.

i. Downgrading evidence: Evidence may be downgraded due to the following reasons: 1. Risk of bias refers to factors that make it less likely that the answer found in the study may not represent the true answer in the population. Faulty randomization, such as lack of concealment at allocation to the study group; lack of blinding to the study group when assessing outcomes; large losses to follow-up; the failure to analyze everyone in the group to which they were randomized; stopping the study early when the benefit seems too great to ignore; or failure to report all outcomes.

2. Inconsistency of findings across a number of studies must be explained. Were the interventions really the same? Were the samples very different? Inconsistencies that cannot be explained make it very difficult to assess the true effect of the treatment.

3. Directness refers to the extent to which two interventions are being compared to each other in similar populations. Indirect comparisons are more difficult to interpret. Two types of indirectness exist. a. The first includes indirect comparisons. For instance, if two drugs are being examined for an outcome, but there are no studies that directly compare the drugs, which is an indirect comparison. b. The second includes differences in population, intervention, comparator, and/or outcome.

4. Imprecision refers to a study that may show statistically significant effects, but the sample size is small and the measure of benefit is imprecise, meanin that it has a wide confidence interval.

5. Publication bias may also exist. Investigators are more likely to submit studies for publication when the results are positive and journals may be more likely to accept them for publication. An effort should be made in a systematic review to uncover studies that have not been published. This is a particularly important issue when the studies are funded by industry

ii. Evidence may be upgraded based upon the following factors: 1. Large effect size: A large effect is much less likely to be spurious than a small effect. Small effect sizes can much more easily result from chance. 2. Dose response: This exists when there is evidence that differences in dosage result in different effects/outcomes. This is one aspect of a finding that suggests an association based on cause and effect. 3. All plausible confounding: In observational trials, it is particularly difficult to measure and control for all plausible confounding. When all unmeasured plausible confounders and biases in an observational study would result in an underestimate of an apparent treatment effect, then it is more likely that a finding is real rather than the result of unmeasured confounding. For instance, if only sicker patients receive an experimental intervention or exposure, yet they still fare better, it is likely that the actual intervention or exposure effect is even larger than the data suggest.

a. Scope of the guideline (CMSS-P 5.1-5.3) The AAFP includes the intent, rationale, and scope in all guidelines. This includes, but may not be limited to, the appropriate users of the guideline, situations in which the guideline should be used, and appropriate patient populations for the guideline.

b. Methodology

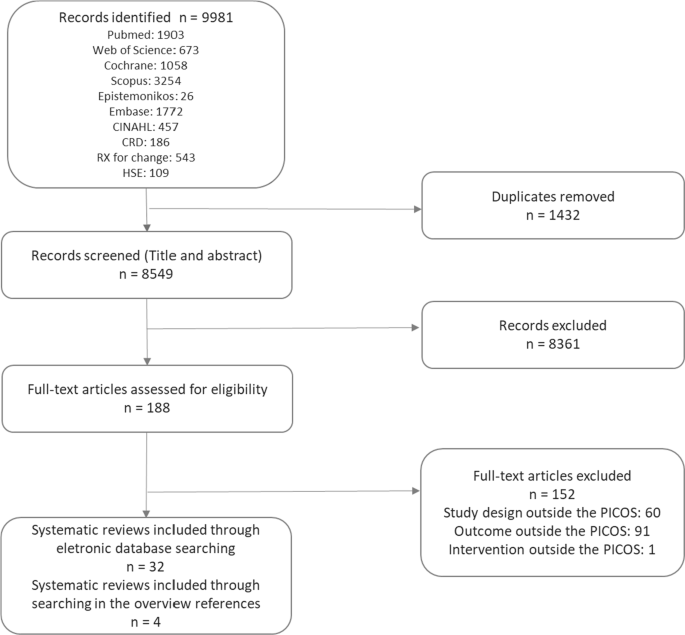

Information regarding the methodology used in the evidence report and in any updated literature searches will be provided in the guideline. This information should include search terms, search dates, outcomes assessed, and key questions that were addressed. A summary of included and excluded articles should be made available for all literature searches performed by the GDG. This information can be included in the guideline as a PRISMA diagram. Records of the study quality assessment should be maintained.

c. Moving from evidence to recommendations (IOM standards 5 and 6; CMSS-P section 6 and 7)

i. As noted in section IX, the AAFP uses a modified GRADE methodology for rating the quality of the evidence, and guiding the strength of recommendations. It is worth noting that moving from examining the evidence to making a recommendation is where much of the disagreement happens in guideline development. Different groups that develop guidelines may disagree on how much weight they give to lower-level evidence; may not fully take into account benefits and harms, costs or burdens; and may give differing emphasis on patient or provider preferences and values. However, all of these factors should be considered when making recommendations. AAFP’s use of the GRADE system helps to systematically examine many of the factors mentioned to determine the quality of the evidence and strength of recommendations. ii. The AAFP strives to only make strong recommendations based on high-level evidence. However, there are few instances where strong recommendations can be made based on moderate or low-level evidence. In these instances, there must be certainty that benefits outweigh harms. iii. Recommendations made include an explanation of the reason for the recommendation; description of benefits and harms; a summary of the relevant available evidence; any explanation of values and preferences that went into the recommendation; a rating of the level of evidence and strength of recommendation; and differences in opinions of GDG panel members, if they exist, for that recommendation. iv. Recommendations made are specific and actionable and worded such that it is clear to the reader that they are (1) strong recommendations, (2) weak recommendations, or (3) good practice points. Suggested language for each type of recommendation is shown below. A table should be included in the guideline to outline the methodology and can highlight the differences between the wording used for the strength of the recommendation.

1. Strong recommendation: Use directive language in the recommendation such as “Family physicians should discuss…” or “Do not order a chest radiograph for children with suspected pneumonia unless...”. The statement should begin with “The AAFP strongly recommends…”.

2. Weak recommendation: Language should reflect the lower quality of evidence and the lower level of certainty regarding the recommendation. Suggested wording includes “Consider offering counseling regarding…” or “Patients may wish to consider…”. The statement should begin with “The AAFP recommends”.

3. Good practice points: Language should reflect the low quality or absence of evidence. “Although not studied in clinical trials, it is standard of care to perform an ECG in patients presenting with chest pain.”c.

d. Panel assignments With direction from the GDG chair, members of the GDG will be given writing assignments to complete during guideline development. When possible, GDG members will be asked for preferences regarding sections of the guideline they would like to write.

e. Making the CPG implementable

i. For implementation, the recommendations should be specific and provide clear direction. The number of recommendations should be kept to a minimum. ii. Access to the guideline should be provided through publication in a journal, the AAFP website, and the guideline clearinghouse. (CMSS 10.1-10.2) iii. When available or appropriate, actions should be taken to incorporate the recommendations at point of care through electronic health records (EHR) reminders or toolkit/checklist for physicians. (CMSS 10.3) iv. Additional implementation methods include mass media campaigns (news article, leadership blog, other avenues as suggested by the AAFP content strategy team—see dissemination section), and interactive educational meetings with quality improvement resources as appropriate (expanded learning session at Family Medicine Experience [formerly Assembly], workshops)

e. Compilation of draft(s) All drafts of the guideline should be sent (or made available) to the GDG chair and staff members at the AAFP. Most often, staff members at the AAFP will compile all sections of the draft guideline and the chair will review the draft(s) before it is sent to other members of the panel.

a. Internal Peer Review

The first round of peer review of the CPG is conducted by members of SCPG and the Science Advisory Panel. All reviewers are given four weeks to complete and return their review form to the staff members at the AAFP. (see Appendix A for an example of the review form). Upon receipt of the reviews, all comments will be recorded. Comments will be addressed when the chair determines that there is a need. A written record will be kept of the rationale for responding or not responding to all comments received.

b. External reviewers (including collaborating organizations)

Relevant stakeholders are included in the external review, including collaborating organizations, and organizations that may be affected by the guideline. AAFP members who are identified as experts in the field may also be asked to participate in the review. All reviewer comments are collected and recorded. A record of how the comment was addressed is kept. Reviewers’ names are kept confidential unless a reviewer wants to be recognized for his or her review.

The draft guideline will not routinely be made available for a period of public comment, but will be reviewed by key stakeholders including patient advocacy groups if a patient voice was unavailable for inclusion on the guideline panel.

a. Following the peer review process, the revised CPG is reviewed by members of CHPS. Upon approval, a recommendation is made to the full commission, which upon approval makes a recommendation to the AAFP Board of Directors for approval.

b. Board of Directors The AAFP Board of Directors reviews the guideline. Any questions from the Board are addressed by the GDG, and staff at the AAFP.

c. Endorsement by collaborators Collaborators on the guideline are given the chance to endorse the guideline after approval by the Board of Directors and before it is published. The collaborators will be sent the embargoed guideline, and given a month to decide upon endorsement.

a. Peer-reviewed journal Upon completion, the AAFP submits its guidelines for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, as appropriate. The guideline manuscript undergoes independent editorial review, and a decision is made about publication. Due to the nature of journals, all supporting materials (such as tables with quality ratings of studies) may not be able to be published. All supporting materials that are relevant to the guideline that are not published will be made available on the AAFP website.

b. Copyright issues Copyright issues are negotiated with the publication journal with appropriate licensing agreements made to the AAFP.

c. AAFP website (CMSS-P 9.1) After publication, the guideline is placed on the AAFP website for easy accessibility. Supporting documents that were not published with the original guideline will be available on the AAFP website as well.

a. Dissemination/marketing plan The AAFP guideline staff members work with other divisions including Communications and Marketing to disseminate the guideline upon publication. Staff members also submit the published guideline to the National Guidelines Clearinghouse for dissemination. Any derivatives made relating to the guideline will also be publicized via a marketing plan.

a. Determination by CHPS All guidelines developed by the AAFP are scheduled for a review five years after completion. However, literature pertaining to a guideline is monitored regularly, and if it is deemed necessary, a review can be initiated sooner. Whichever the case, when a guideline review is initiated, a preliminary search of the literature is completed and brought to the commission to determine if a new systematic review is necessary. If so, the topic will be nominated to AHRQ for a full systematic evidence update. If not, a decision whether to reaffirm the guideline for additional time not to exceed five years, or sunset the guideline. The commission’s recommendation is then approved by the Board of Directors.

a. External guidelines may be reviewed for endorsement by the AAFP following a request from another organization, a request from a member, or if identified as having a high applicability to family medicine.

b. The guideline will then be reviewed using set criteria (see Appendix A for review form) by members of the commission, or AAFPmembers at large with appropriate expertise and/or review experience. In certain cases, staff may review guidelines from selected organizations.

c. The member or staff reviewers will then submit comments and a recommendation to staff (see Appendix B for AAFP’s Endorsement Policy).

i. Endorse—the AAFP fully endorses the guideline ii. Affirmation of Value to Family Physicians—the guideline does not meet the requirements for full endorsement, or the AAFP is not able to endorse all the recommendations, but feel the guideline is of some benefit for family physicians iii. Not Endorse—the AAFP does not endorse the guideline and the reasons are stated. The AAFP may also choose to remain silent.

d. Reviewer comments and recommendations will be collated and reviewed by staff and the chairs of CHPS and SCRP. If substantial differences occur, the reviewers will discuss and determine if a consensus can be reached.

e. A recommendation will then be given to the SCRP for approval, and if approved, will then be taken to the commission for approval.

f. A recommendation describing the commission’s action will be submitted to the Board or board chair for approval.

g. Once approved, the organization will be notified by staff and a summary of the key recommendations, and a link to the full guideline will be posted on the AAFP website. Only guidelines with endorsement or affirmation of value will be placed on the website.

h. External guidelines designated as endorsed, or affirmation of value will be reviewed every five years following their date of publication. Guidelines may be reviewed earlier if new evidence warrants an update.

Council of Medical Specialty Societies: Code for Interaction with Companies

Council of Medical Specialty Societies: CMSS Principles for the Development of Specialty Society Clinical Guidelines

Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust . Washington, DC. National Academies Press. 2011. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13058/clinical-practice-guidelines-we-can-trust . Accessed November 15, 2017.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC. National Academies Press. 2011. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Finding-What-Works-in-Health-Care-Standards-for-Systematic-Reviews/Standards.aspx . Accessed November 15, 2017.

Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/conflict-management_research.pdf . Accessed Nov. 1, 2016.

Norris SL, Holmer HK, Burda BU, Ogden LA, Fu R. Conflict of interest policies for organizations producing a large number of clinical practice guidelines. 2012; PLoS One . 7(5):e375413.

Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. 1993; N Engl J Med . 329(8):573-6.

For information about the AAFP Guideline Endorsement Form, please contact Melanie Bird, PhD, MSAM, Senior Manager, Clinical and Health Policies at (800) 906-6000 extension 3165, or [email protected] .

Board Approved: December 2017

A. AAFP Endorsement Form

B. AAFP Endorsement of Clinical Practice Guidelines

C. AAFP Clinical Practice Guideline Principles and AAFP Joint Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines with Other Organizations

E. Grading of Recommendations Assessment , Development and Evaluation (short GRADE) Working Group

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Evidence-Based Medicine and Clinical Guidelines

- Evidence-Based Medicine |

- Clinical Guidelines |

Physicians have always felt that their decisions were based on evidence; thus, the current term “evidence-based medicine” is somewhat of a misnomer. However, for many clinicians, the “evidence” is often a vague combination of recollected strategies effective in previous patients, advice given by mentors and colleagues, and a general impression of “what is being done” based on random journal articles, abstracts, symposia, and advertisements. This kind of practice results in wide variations in strategies for diagnosing and managing similar conditions, even when strong evidence exists for favoring one particular strategy over another. Variations exist among different countries, different regions, different hospitals, and even within individual group practices. These variations have led to a call for a more systematic approach to identifying the most appropriate strategy for an individual patient; this approach is called evidence-based medicine (EBM). EBM is built on reviews of relevant medical literature and follows a discrete series of steps.

Evidence-Based Medicine

EBM is not the blind application of advice gleaned from recently published literature to individual patient problems. It does not imply a "one size fits all" model of care. Rather, EBM requires the use of a series of steps to gather sufficiently useful information to answer a carefully crafted question for an individual patient. Fully integrating the principles of EBM also incorporates the patient’s value system, which includes such things as costs incurred, the patient’s religious or moral beliefs, and patient autonomy. Applying the principles of EBM typically involves the following steps:

Formulating a clinical question

Gathering evidence to answer the question, evaluating the quality and validity of the evidence.

Deciding how to apply the evidence to the care of a specific patient

Questions must be specific. Specific questions are most likely to be addressed in the medical literature. A well-designed question specifies the population, intervention (diagnostic test, treatment), comparison (treatment A vs treatment B), and outcome. “What is the best way to evaluate someone with abdominal pain?” is not an overly useful question to pursue in the literature. A better, more specific question may be “Is CT or ultrasonography preferable for diagnosing acute appendicitis in a 30-year-old male with acute lower abdominal pain?”

A broad selection of relevant studies is obtained from a review of the literature. Standard resources are consulted (eg, MEDLINE or PubMed for primary references, the Cochrane Collaboration [treatment options often for specific questions], ACP Journal Club).

Not all scientific studies are of equal value. Different types of studies have different scientific strengths and legitimacy, and for any given type of study, individual examples often vary in quality of the methodology, internal validity, generalizability of results, and applicability to a specific patient (external validity).

Levels of evidence are graded 1 through 5 in decreasing order of quality. Types of studies at each level vary somewhat with the clinical question (eg, of diagnosis, treatment, or economic analysis), but typically consist of the following:

Level 1 (the highest quality): Systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and high-quality, single, randomized controlled trials

Level 2: Well-designed cohort studies

Level 3: Systematically reviewed case-control studies

Level 4: Case series and lesser-quality cohort and case-control studies

Level 5: Expert opinion not based on critical appraisal, but based on reasoning from physiology, bench research, or underlying principles

For EBM analysis, the highest level of evidence available is selected. Ideally, a significant number of large, well-conducted level 1 studies are available. However, because the number of high-quality, randomized, controlled trials is vanishingly small compared with the number of possible clinical questions, less reliable level 4 or 5 evidence is very often all that is available. Lower-quality evidence does not mean that the EBM process cannot be used, just that the strength of the conclusion is weaker.

Deciding how to apply the evidence to the care of a given patient

Because the best available evidence may have come from patient populations with different characteristics from those of the patient in question, significant judgment is required when applying results from a randomized trial to a specific patient. Additionally, patients’ wishes regarding aggressive or invasive tests and treatment must be taken into account as well as their tolerance for discomfort, risk, and uncertainty. For example, even though an EBM review may definitively show a 3-month survival advantage from an aggressive chemotherapy regimen in a certain form of cancer, patients may differ on whether they prefer to gain the extra time or avoid the extra discomfort. The cost of tests and treatments may also influence physician and patient decision making, especially when some of the alternatives are significantly costlier for the patient. Two general concerns are that patients who voluntarily participate in clinical trials are not the same as patients in general practice, and care delivered in a clinical trial environment is not identical to general care in the medical community.

Limitations of the evidence-based approach

Dozens of clinical questions are faced during the course of even one day in a busy practice. Although some of them may be the subject of an existing EBM review available for reference, most are not, and preparing a formal EBM analysis is too time-consuming to be useful in answering an immediate clinical question. Even when time is not a consideration, many clinical questions do not have any relevant studies in the literature.

Clinical Guidelines

Clinical guidelines have become widely available across the practice of medicine; many specialty societies have published such guidelines. Most well-conceived clinical guidelines are developed using a specified method that incorporates principles of EBM and consensus or Delphi process recommendations made by a panel of experts. Although clinical guidelines may describe idealized practice, clinical guidelines alone cannot establish the standard of care for an individual patient.

Some clinical guidelines follow “if, then” rules (eg, if a patient is febrile and neutropenic, then institute broad-spectrum antibiotics). More complex, multistep rules may be formalized as algorithms. Guidelines and algorithms are generally straightforward and easy to use but should be applied only to patients whose clinical characteristics (eg, demographics, comorbidities, clinical features) are similar to those of the patient group used to create the guideline. Furthermore, guidelines do not take into account the degree of uncertainty inherent in test results, the likelihood of treatment success, and the relative risks and benefits of each course of action. To incorporate uncertainty and the value of outcomes into clinical decision making, clinicians must often apply the principles of quantitative or analytical medical decision making (see also Clinical Decision-Making Strategies ). Additionally, many entities that publish guidelines require that only randomized trial data be used, which is often a significant limitation.

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

Study Design 101: Practice Guideline

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A statement produced by a panel of experts that outlines current best practice to inform health care professionals and patients in making clinical decisions. The statement is produced after an extensive review of the literature and is typically created by professional associations, government agencies, and/or public or private organizations.

Good guidelines clearly define the topic; appraise and summarize the best evidence regarding prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, harm, and cost-effectiveness; and identify the decision points where this information should be integrated with clinical experience and patient wishes to determine practice. Practice guidelines should be reviewed frequently and updated as necessary for continued accuracy and relevancy.

Practice guidelines are also known as "Evidence-based guidelines" and "Clinical guidelines."

- Created by panels of experts

- Based on professional published literature

- Practical guidance for clinicians

- Considered an evidence-based resource

Disadvantages

- Slow to change or be updated

- Not always available, especially for controversial topics

- Expensive and time-consuming to produce

- Recommendations might be affected by the type of organization creating the guideline

Design pitfalls to look out for

The panel should be composed of a variety of experts with assorted affiliations.

Is the panel composed of members from a variety of professional associations, government agencies and/or institutes? Does one organization/association predominate?

Fictitious Example

A practice guideline focusing on the best way to prevent sunburn when wearing sunscreen involved forming a multidisciplinary panel of experts (dermatologists, oncologists, sunscreen chemists, etc.). These experts searched the literature and identified 123 research articles on sunscreen and sunburn prevention for appraisal. The research was then reviewed by a member of the panel with critical appraisal experience in order to identify only those high-quality research articles that permit making recommendations. Ninety-seven high-quality studies were selected. These articles were read and synthesized by the panel to create a formal guideline recommendation. Based on the literature, the guideline recommended that the best way to prevent sunburn is to wear UVA blocking sunscreen daily. However, there was insufficient evidence in the literature to make any recommendations about newer sunscreen formulations. This identified the need for further research on this topic.

Real-life Examples

Chou, R., Deyo, R., Friedly, J., Skelly, A., Hashimoto, R., Weimer, M., ... Brodt, E. (2017). Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline . Annals Of Internal Medicine, 166 (7), 493-+. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2459

A group from The American College of Physicians reviewed the current evidence to determine which nonpharmacologic options are effective in treating low back pain (both acute and chronic). New treatment options appeared in the literature since 2007 (prior guideline on this topic) and several show "small to moderate, usually short-term effect on pain" including tai chi, mindfulness-based stress reduction, yoga as well as continued support for prior treatment recommendations including exercise, psychological therapies, multidisciplinary rehabilitation, spinal manipulation, massage, and acupuncture. There were greater effects on pain than on function, and the strength of evidence for several of these interventions is low.

Lennon, S., Dellavalle, D., Rodder, S., Prest, M., Sinley, R., Hoy, M., & Papoutsakis, C. (2017). 2015 Evidence Analysis Library evidence-based nutrition practice guideline for the management of hypertension in adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117 (9), 1445-1458.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.04.008

This guideline addresses the role of nutrition in managing hypertension in adults. Seventy studies were evaluated, resulting in eight recommendations to reduce blood pressure in adults with hypertension, based on moderate levels of evidence: "provision of medical nutrition therapy by an RDN [registered dietitian nutritionist], adoption of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension dietary pattern, calcium supplementation, physical activity as a component of a healthy lifestyle, reduction in dietary sodium intake, and reduction of alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers. Increased intake of dietary potassium and calcium as well as supplementation with potassium and magnesium for lowering BP are also recommended."

Related Terms

National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC)

The National Guideline Clearinghouse was a public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) . It was taken offline in 2018 after federal funding ended.

Now test yourself!

1. Practice guidelines are available for almost any condition you'll encounter in your patients.

a) True b) False

2. Practice Guidelines are typically written by which of the following?

a) Public or private organizations b) Government agencies c) Professional associations d) The National Guideline Clearinghouse e) b, c and d only f) a, b, and c only

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Randomized Controlled Trial

- Next: Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

Brophy, Robert H. MD, FAAOS; Lowry, Kent Jason MD, FAAOS

From Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO (Brophy) and Aspirus Rhinelander Hospital, Aspirus Northland Orthopedics & Sports Medicine, Rhinelander, WI (Lowry).

Brophy or an immediate family member serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of AAOS, Editorial or governing board: American Journal of Sports Medicine, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Vice Chair, Musculoskeletal Committee, National Football League.

Criteria: AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary

This clinical practice guideline was approved by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors on August 22, 2022.

The complete document, Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries : Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline, includes all tables and figures and is available at www.aaos.org/aclcpg .

Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries Work Group : Robert Brophy, MD, FAAOS (Co-Chair); Kent Jason Lowry, MD, FAAOS (Co-Chair); Henry Ellis, MD, FAAOS; Neeraj Patel, MD, FAAOS; Neeraj Patel, MD, MPH, MBS; Julie Dodds, MD, FAAOS; Christopher C. Kaeding, MD; Anthony Beutler, MD; Andrew Gordon, MD, PhD; Richard Shih, MD, FACEP. Nonvoting Oversight Chair, Kevin Shea, MD, FAAOS. Staff of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Jayson Murray, MA; Kaitlyn Sevarino, MBA, CAE; Danielle Schulte, MS; Tyler Verity; Frank Casambre, MPH; Patrick Donnelly, MPH; Anushree Tiwari, MPH; Jennifer Rodriguez, MBA.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License 4.0 (CCBY-NC-ND) , where it is permissible to download and share the work provided it is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commercially without permission from the journal.

Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries : Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline is based on a systematic review of published studies for the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injurie in both skeletally mature and immature patients. This guideline contains eight recommendations and seven options to assist orthopaedic surgeons and all qualified physicians managing patients with ACL injuries based on the best current available evidence. It is also intended to serve as an information resource for professional healthcare practitioners and developers of practice guidelines and recommendations. In addition to providing pragmatic practice recommendations, this guideline also highlights gaps in the literature and informs areas for future research and quality measure development.

Overview and Rationale

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) with input from representatives from the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and the American College of Emergency Physicians recently published their clinical practice guideline (CPG), Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries . 1 This CPG was approved by the AAOS Board of Directors in August 2022.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of the knee is commonly injured, often during sports, although it can occur during a wide variety of activities of daily living. Although this injury may be contact or noncontact, the majority result from a noncontact mechanism. 2 , 3 The rate of noncontact ACL injuries is reported to occur at a twofold to eightfold greater rate in female patients than male patients participating in similar sports and activities. 4 An estimated 200,000 patients present annually with ACL injuries in the United States alone. 5 Although the mean patient age for ACL reconstruction remained constant (29 years) from 1990 to 2006, the incidence of ACL reconstruction in patients older than 40 years increased >200%, second in growth only to the incidence of reconstructions in patients younger than 14 years. 4 , 6

These injuries can have a notable effect on knee function, particularly for activities involving cutting, pivoting, and landing. Younger and more active patients tend to be most affected by these injuries, although some patients with ACL tears can have instability with very mundane tasks. Treatment of these injuries is important to optimize joint function, sports activity, work, and activities of daily living.

Most treatments are associated with some known risks. Nonsurgical management may put patients at risk for persistent or recurrent instability and additional meniscal and/or cartilage injury. Complications of surgical treatment include recurrent instability including graft retear, postoperative loss of motion or arthrofibrosis, neurovascular injury, kneeling pain, and routine postoperative concerns, such as infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and anesthesia complications. In addition, patients who have suffered an ACL tear are at increased risk of contralateral ACL tear. The choice of treatment may depend on a variety of factors which can include associated injuries and patient-specific characteristics, such as comorbidities, skeletal maturity, and especially future desired activity such as but not limited to sports participation and work needs.

Therefore, the AAOS developed this CPG to aid practitioners in the management of patients with ACL injuries. 1 Furthermore, the CPG represents a resource demonstrating areas that need additional investigation to provide improved evidence-based guidelines for the management of ACL injuries.

In summary, the ACL injuries guideline involved reviewing over 5,500 abstracts and more than 1,100 full-text articles to develop eight recommendations supported by 324 research articles meeting stringent inclusion criteria. Each recommendation is based on a systematic review of the research-related topic which resulted in five recommendations classified as high and three recommendations classified as moderate for both skeletally mature and immature patients who have been diagnosed with an ACL injury. The strength of recommendation also takes into account the quality, quantity, and the trade-offs between the benefits and harms of a treatment, the magnitude of a treatment's effect, and whether there are data on critical outcomes. Strength of recommendation is assigned based on the quality of the supporting evidence. In addition, seven options were formulated. Options are formed when there is little or no evidence on a topic. These included a consensus option on knee aspiration and limited strength options on ACL surgical reconstruction, meniscal repair, treatment for patients with a combined ACL/medial collateral ligament (MCL) tear, the use of prophylactic knee bracing treatment to prevent an ACL injury, return to sport after ACL reconstruction, and functional knee bracing treatment when returning to activity after ACL reconstruction.

Guideline Summary

The developed recommendations are meant to aid in the clinical decision-making process for the treatment of patients who have been diagnosed with an ACL injury of the knee. The use of this guideline helps in treating physicians to determine the appropriate intervention/s that are likely to provide the greatest predictable benefit. This CPG set offers a substantially updated perspective from the published 2013 iteration, which previously offered 20 statements, 5 of which were supported by strong evidence, 6 by moderate, the rest of which were limited evidence, or consensus-based. New research, of improved quality, has allowed for more decisive CPG statements. The updated 2022 CPG consisted of 15 statements, 5 of which provide strong evidence and 3 of which provide moderate evidence. Three recommendations are substantively different from the recommendations of the previous CPG, and three recommendations are new and were not part of the previous CPG.

Previously, the 2013 ACL CPG recommended that the practitioner should use either autograft or appropriately processed allograft tissue because the measured outcomes are similar based on strong evidence. This has been revised in the current CPG to recommend that surgeons should consider autograft over allograft to improve patient outcomes and decrease ACL graft failure rate, particularly in young and/or active patients, based on strong evidence. Autograft has potential benefits for graft ruptures/revision and functional scores based on 2 high, 2 moderate, and 11 low-level studies. 7 ‐ 12

In another shift, the current CPG states that surgeons may favor bone-tendon-bone (BTB) to reduce the risk of graft failure or infection or hamstring to reduce the risk of anterior or kneeling pain when using autograft to perform ACL reconstruction in skeletally mature patients, citing moderate evidence. 13 ‐ 24 This recommendation, detailing the relative advantages of these autograft choices, is a clarification of the previous CPG which recommended that the practitioner should use bone-patellar tendon-bone or hamstring tendon grafts because the measured outcomes are similar based on strong evidence.

The previous CPG recommended that when indicated, reconstruction should occur within 5 months of ACL injury to protect articular cartilage and menisci, citing moderate evidence. The current CPG recommends reconstruction as soon as possible when indicated as the risk of additional cartilage and meniscal injury starts to increase within 3 months, citing strong evidence. 25 ‐ 30 As mentioned previously, treatment is highly dependent on patient characteristics, so while this recommendation applies to younger and more active patients who should be treated as expeditiously as possible, it is less applicable to older and less active patients who may do well with nonsurgical treatment and are not necessarily indicated initially for surgical intervention.

The current CPG added a new recommendation that ACL tears indicated for surgery should be treated with ACL reconstruction rather than repair because of lower risk of revision surgery based on strong evidence. 31–33 The previous CPG did not contain any recommendations regarding repair versus reconstruction. Although ACL reconstruction is currently the standard of care for surgical treatment of primary ACL injury, there is much to be learned from ongoing and future research on innovations in biologic intervention and/or surgical technique which may optimize the results of ACL repairs.

Another new recommendation was that anterior lateral ligament (ALL) reconstruction or lateral extra-articular tenodesis (LET) could be considered when performing hamstring autograft reconstruction in select patients to reduce graft failure and improve short-term function, although long-term outcomes are yet unclear based on moderate evidence. 34 ‐ 39 The previous CPG did not make any recommendation regarding augmentation of hamstring autograft reconstruction with ALL reconstruction or LET.

Finally, the current CPG recommends that functional evaluation, such as the hop test, may be considered as one factor to determine return to sport after ACL reconstruction based on limited evidence for better functional outcomes. 40 , 41 The previous CPG did not support waiting a specific time from surgery/injury or achieving a specific functional goal before return to sports participation after ACL injury or reconstruction also based on limited evidence. More research is clearly needed in this area.

Recommendations

This Summary of Recommendations of the AAOS Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries : Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline contains a list of evidence-based prognostic and treatment recommendations ( Table 1 ). Discussions of how each recommendation was developed and the complete evidence report are contained in the full guideline at www.aaos.org/aclcpg . Readers are urged to consult the full guideline for the comprehensive evaluation of the available scientific studies. The recommendations were established using methods of evidence-based medicine that rigorously control for bias, enhance transparency, and promote reproducibility. An exhaustive literature search was conducted resulting initially in more than 1,100 papers for full review. The papers were then graded for quality and aligned with the work group's patients, interventions, and outcomes of concern. For CPG PICO (ie, population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) questions that returned no evidence from the systematic literature review, the work group used the established AAOS CPG methodology to generate one companion consensus statement that physicians may consider aspirating painful, tense effusions after knee injury with likely or confirmed ACL tear.

The Summary of Recommendations is not intended to stand alone. Medical care should be based on evidence, a physician's expert judgement, and the patient's circumstances, values, preferences, and rights. A patient-centered discussion understanding an individual patient's values and preferences can inform appropriate decision-making. The recommendations regarding the treatment of ACL tears are primarily focused on younger, more active individuals. Recommendations regarding surgical treatment are principally based on literature studying ACL tears as an isolated ligamentous injury rather than a multiligamentous injury (except for isolated ACL and MCL injury). A variety of mitigating circumstances, particularly related to patient age, preinjury activity, symptoms, and desired level of postinjury activity, may also be factors in the shared decision-making process.

A Strong recommendation means that the quality of the supporting evidence is high. A Moderate recommendation means that the benefits exceed the potential harm (or that the potential harm clearly exceeds the benefits in the case of a negative recommendation), but the quality/applicability of the supporting evidence is not as strong. A Limited option means that there is a lack of compelling evidence that has resulted in an unclear balance between benefits and potential harm. A Consensus option means that expert opinion supports the guideline recommendation, although there is no available realistic evidence that meets the inclusion criteria of the guideline's systematic review.

| Strength of Recommendation | Overall Strength of Evidence | Description of Evidence quality | Strength Visual |

| Strong | Strong | Evidence from two or more “High” quality studies with consistent findings for recommending for or against the intervention. Or Rec is upgraded from Moderate using the EtD framework. | |

| Moderate | Strong, moderate, or limited | Evidence from two or more “Moderate” quality studies with consistent findings or evidence from a single “High” quality study for recommending for or against the intervention. Or Rec is upgraded or downgraded from Limited or Strong using the EtD framework. | |

| Limited | Limited or moderate | Evidence from one or more “Low” quality studies with consistent findings or evidence from a single “Moderate” quality study recommending for or against the intervention. Or Rec is downgraded from Strong or Moderate using the EtD framework. | |

| Consensus | No reliable evidence | There is no supporting evidence, or higher quality evidence was downgraded due to major concerns addressed in the EtD framework. In the absence of reliable evidence, the guideline work group is making a recommendation based on their clinical opinion. |

History and Physical

A relevant history should be obtained, and a focused musculoskeletal examination of the lower extremities should be done when assessing for an ACL injury.

Implication: Practitioners should follow a Strong recommendation unless a clear and compelling rationale for an alternative approach is present.

Surgical Timing

When surgical treatment is indicated for an acute isolated ACL tear, early reconstruction is preferred because the risk of additional cartilage and meniscal injury starts to increase within 3 months.

Single-bundle or Double-bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

In patients undergoing intra-articular ACL reconstruction single-bundle or double-bundle techniques can be considered because outcomes are similar.

Autograft Versus Allograft

When performing an ACL reconstruction, surgeons should consider autograft over allograft to improve patient outcomes and decrease ACL graft failure rate, particularly in young and/or active patients.

Autograft Source

When performing an ACL reconstruction with autograft for skeletally mature patients, surgeons may favor BTB to reduce the risk of graft failure or infection, or hamstring to reduce the risk of anterior or kneeling pain.

Implication: Practitioners should generally follow a Moderate recommendation but remain alert to new information and be sensitive to patient preferences.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Training Programs

Training programs designed to prevent injury can be used to reduce the risk of primary ACL injuries in athletes participating in high-risk sports.

Anterolateral Ligament/Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis

ALL reconstruction/LET could be considered when performing hamstring autograft reconstruction in select patients to reduce graft failure and improve short-term function, although long-term outcomes are yet unclear.

Repair Versus Reconstruction

ACL tears indicated for surgery should be treated with ACL reconstruction rather than repair because of lower risk of revision surgery.

Low-quality evidence, no evidence, or conflicting support evidence has resulted in the following statements for patient interventions to be listed as options for the specified condition. Future research may eventually cause these statements to be upgraded to Strong or Moderate recommendations for treatment.

Aspiration of the Knee

In the absence of reliable evidence, it is the opinion of the workgroup that physicians may consider aspirating painful, tense effusions after knee injury.

Implication: In the absence of reliable evidence, practitioners should remain alert to new information because emerging studies may change this recommendation. Practitioners should weigh this recommendation with their clinical expertise and be sensitive to patient preferences.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgical Reconstruction

ACL reconstruction can be considered to lower the risk of future meniscus pathology or procedures, particularly in younger and/or more active patients. ACL reconstruction may be considered to improve long-term pain and function.

Implication: Practitioners should feel little constraint in after a recommendation labeled Limited, exercise clinical judgment, and be alert for emerging evidence that clarifies or helps to determine the balance between benefits and potential harm. Patient preference should have a substantial influencing role.

Meniscal Repair

In patients with ACL tear and meniscal tear, meniscal preservation should be considered to optimize joint health and function.

Combined Anterior Cruciate Ligament/MCL Tear

In patients with combined ACL and MCL tears, nonsurgical treatment of the MCL injury results in good patient outcomes, although surgical treatment of the MCL may be considered in select cases.

Prophylactic Knee Bracing Treatment

Prophylactic bracing treatment is not a preferred option to prevent ACL injury.

Return to Sport

Functional evaluation, such as the hop test, may be considered as one factor to determine return to sport after ACL reconstruction.

Return to Activity Functional Bracing Treatment

Functional knee braces are not recommended for routine use in patients who have received isolated primary ACL reconstruction because they confer no clinical benefit.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

American academy of orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guideline case..., american academy of orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guideline summary on ..., comprehensive review of multidirectional instability of the shoulder, posterolateral corner of the knee: an update on current evaluation and..., diagnosis and management of partial thickness rotator cuff tears: a....

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2022

Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: an overview of systematic reviews

- Viviane C. Pereira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9628-9974 1 ,

- Sarah N. Silva 2 ,

- Viviane K. S. Carvalho 1 ,

- Fernando Zanghelini 1 &

- Jorge O. M. Barreto 1

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 20 , Article number: 13 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

60 Citations

36 Altmetric

Metrics details

As a source of readily available evidence, rigorously synthesized and interpreted by expert clinicians and methodologists, clinical guidelines are part of an evidence-based practice toolkit, which, transformed into practice recommendations, have the potential to improve both the process of care and patient outcomes. In Brazil, the process of development and updating of the clinical guidelines for the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) is already well systematized by the Ministry of Health. However, the implementation process of those guidelines has not yet been discussed and well structured. Therefore, the first step of this project and the primary objective of this study was to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of strategies used to promote clinical practice guideline implementation and dissemination.

This overview used systematic review methodology to locate and evaluate published systematic reviews regarding strategies for clinical practice guideline implementation and adhered to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic review (PRISMA).

This overview identified 36 systematic reviews regarding 30 strategies targeting healthcare organizations, healthcare providers and patients to promote guideline implementation. The most reported interventions were educational materials, educational meetings, reminders, academic detailing and audit and feedback. Care pathways—single intervention, educational meeting—single intervention, organizational culture, and audit and feedback—both strategies implemented in combination with others—were strategies categorized as generally effective from the systematic reviews. In the meta-analyses, when used alone, organizational culture, educational intervention and reminders proved to be effective in promoting physicians' adherence to the guidelines. When used in conjunction with other strategies, organizational culture also proved to be effective. For patient-related outcomes, education intervention showed effective results for disease target results at a short and long term.

This overview provides a broad summary of the best evidence on guideline implementation. Even if the included literature highlights the various limitations related to the lack of standardization, the methodological quality of the studies, and especially the lack of conclusion about the superiority of one strategy over another, the summary of the results provided by this study provides information on strategies that have been most widely studied in the last few years and their effectiveness in the context in which they were applied. Therefore, this panorama can support strategy decision-making adequate for SUS and other health systems, seeking to positively impact on the appropriate use of guidelines, healthcare outcomes and the sustainability of the SUS.

Peer Review reports

Clinical guidelines are defined as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances” [ 1 ]. As a source of readily available evidence, rigorously synthesized and interpreted by expert clinicians and methodologists, guidelines are part of an evidence-based practice toolkit which, transformed into practice recommendations, have the potential to improve both the process of care and patient outcomes [ 2 ]. For example, greater adherence to guidelines has been associated with reduced morbidity after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, better and faster outcomes in patients with psychiatric disorders, better physical functioning outcomes, and less use of low back pain care [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

However, although guidelines may be seen as important tools that support decision-making, in conjunction with clinical judgement and patient preference, there is still a lack of adherence to guidelines worldwide across different conditions and levels of care [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Studies from different countries have demonstrated suboptimal adherence to guidelines for low back pain in primary care, including the use of interventions with little or no benefit [ 9 ]. Among Australian nutritionists who provide clinical care to cancer patients, evidence indicates that only a third of the guidelines are routinely followed [ 10 ]. In Switzerland and Norway, a study found low overall adherence to current practice guidelines and high variation in the use of nutritional therapy in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation [ 11 ]. A study carried out in Norway showed low adherence of regular general practitioners to the palliative care guideline [ 12 ]. In the management of osteoarthritis, studies suggest that the main approaches recommended in the guidelines are underutilized and that the quality of care is inconsistent [ 13 ].

Numerous factors can influence the acceptance and use of guidelines, which may occur at the micro (individual behavioural, including clinicians and consumers), meso (organizational) or macro (context and system) level [ 14 ]. Some of these factors are intrinsic to the nature of newly recommended practice or technology itself, individual characteristics of healthcare professionals, and organizational capacity of health services to collect, adapt, share and apply evidence [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Other factors are intrinsic to guidelines; for example, when recommendations are not at all explicit, or they are distorted or ambiguous, due to conflict of interest, variable methodological quality, or being poorly written, they may be viewed as inapplicable to patients or as reducing clinician autonomy [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].